Abstract

At first sight, Mexico appears to be a textbook example of a state affected by offshore finance. Offshore financial services allow corporations and the wealthy to plan taxes, avoid regulations or to launder money. The literature holds that large, developing, open economies, with geographical proximity to offshore centers and problems of crime and corruption are particularly affected by offshoring. By this logic, we should expect Mexico to show a significant demand for offshore financial services. Yet, new empirical evidence derived from interviews and banking statistics suggests otherwise. Mexican firms and individuals make only limited use of offshore finance. The article explains why. Building on a Weberian notion of the state, the article shows that the historically exclusive nature of Mexico’s state concentrates political and economic power such that the onshore economy offers similar rents for economic elites as offshoring. Moreover, in instances where economic actors use offshore services it is driven by banking, not taxation. These findings have two theoretical implications. First, they confirm that institutions matter, though differently than hitherto thought. Second, we must look beyond taxation to include banking into our analyses.

1. Introduction

Offshore finance ostensibly robs the state of power. Wealthy individuals and corporations use offshore financial services to minimize their tax bills, to avoid domestic financial regulations, to get access to credit or to launder money. As a result, offshore finance shrinks the state’s revenue (Zucman, Citation2013), limits its policy autonomy (Genschel, Citation2005; Swank, Citation2016a) and restricts law enforcement (Findley, Nielson, & Sharman, Citation2014). However, these effects of offshore finance on state power are not equally distributed across countries. Rather, economic actors in countries with certain characteristics appear to have a higher demand for offshore financial services than others. Large countries are more affected by the use of offshore financial services than smaller ones (Genschel & Seelkopf, Citation2016); developing countries more than developed ones (Crivelli, De Mooij, & Keen, Citation2015; Genschel & Seelkopf, Citation2016); open economies more than closed ones (Wibbels & Arce, Citation2003); countries with high levels of crime and corruption more than those with lower levels (Genschel & Seelkopf, Citation2016; Kar & Schjelderup, Citation2015); and countries which are geographically close to offshore financial centers more than those at a distance (Blanco & Rogers, Citation2014; Zucman, Citation2013). Mexico meets all the criteria that are associated with a considerable use of offshore financial services: it is large, developing, open, has endemic problems with crime and corruption and is located closely to the Caribbean, one of the world’s leading offshore hubs. That is, Mexico is what Gerring (Citation2009) terms a ‘crucial case’, a case, which most likely exhibits a given effect. Considering Mexico’s characteristics, we would expect its economic actors to make ample use of offshore financial services, which in turn, should, if the literature’s hypotheses are correct, undermine Mexican state power.

Puzzlingly, new empirical evidence from Mexico suggests otherwise. According to data that the author derived from elite interviews conducted in Mexico and from banking statistics, Mexican firms and individuals make little use of offshore financial services. This article asks why that is the case despite Mexican economic actors’ theoretical propensity toward the extensive use of offshore financial services.

There are two general avenues toward an explanation. The first one is to search the answer in the nature of offshore financial services available to Mexican firms and wealthy individuals. So far, relevant research about offshore finance operates mostly on an aggregate level (Crivelli et al., Citation2015; Palan, Citation1998; Zucman, Citation2013), missing out on the potential variance of the demand for offshore financial services across countries. Therefore, this avenue is little explored. The second avenue is to search for an explanation in the characteristics of the Mexican state. This avenue of explanation has been explored more, but not yet for the case of Mexico. Research on the effects of financial globalization on domestic taxation found that domestic politics and institutions condition the effect of the former on the latter (Basinger & Hallerberg, Citation2004; Swank, Citation2016a; Wibbels & Arce, Citation2003). Given that offshore finance is a specific incidence of financial globalization, the shape of domestic politics and institutions may condition the demand for offshore financial services.

The article integrates these two explanatory avenues by analyzing the relationship between offshore finance and state power in Mexico. To do so, the article proceeds in two analytical steps. First, I establish empirically the scope and pattern of offshoring. This step reveals the extent to which Mexican firms and individuals go offshore and the motivations to do so. In the second step, I examine the historical development and contemporary shape of domestic politics and institutions and how they may condition the observed level of offshoring. This examination follows the premise of historical institutionalism that, fundamentally, politics is about the conflict over different groups’ interests. The conflicts are shaped and organized through historically grown political and economic institutions such that, inescapably – though not unchangeably – some interests are privileged over others (Hall & Taylor, Citation1996).

Against the background of existing scholarship, searching for an explanation in the characteristics of the Mexican state appears promising. Yet, it also creates a conceptual challenge by introducing the notion of the state and its sources of power. The modern state is a highly contested concept, because, as Skinner (Citation2009, p. 326) writes, ‘there has never been any agreed concept to which most of the word state has answered.’ As a result, one can bracket out the concept to avoid contestation. That is what most of the offshore literature and, paradoxically, the literature on the relationship between globalization and the nation state do. Alternatively, one can employ an existing concept of the modern state, including its contested aspects. The article opts for the latter approach. Avoiding an explicit concept of the state would limit our understanding of the offshore phenomenon. The term implies an onshore complement to which it stands in contrast and so to understand offshore, we must have a clear idea of ‘onshore’ too. Furthermore, not spelling out what the modern state is risks impoverishing the analysis by equating the notion of the state with that of the government (Skinner, Citation2009). In this article, I employ Weber’s concept of the modern state (1994, p. 316). As I argue in more detail in the next section, despite its limitations, Weber’s notion of the state provides an instructive frame for the analysis of the development and shape of the contemporary Mexican state and its relationship to offshore finance.

Together the empirical assessment of the scope and pattern of offshoring and the historical institutionalist analysis reveal that the relationship between the Mexican government, its financiers and taxpayers shaped banking services and tax policies such, that Mexican corporations and wealthy individuals have limited incentives to go offshore. The handful of large, internationally active Mexican economic actors can use the mostly foreign-owned banking system to access international financial markets without having to go offshore. Tax evaders and money launderers, on the other hand, can hide in the onshore informal economy. That is, the oligopolistic structure of the Mexican economy in combination with its large informal sector offers similar rents for capital as offshore financial services, while demanding less legal and financial sophistication. With its analytical approach and empirical findings, the article makes three principal contributions. First, it helps to move the offshore literature’s focus from the aggregate to the country level, thereby accounting for geographical and historical contingencies of the demand for offshore financial services. Next, it contributes to the growing literature on international tax competition by confirming that institutions matter, though differently than hitherto thought. Finally, by employing an explicit concept of the state and its sources of power, the analysis demonstrates that, to understand the power relationship between offshore finance and the state, we need to look beyond taxation to banking as a central driver for offshoring.

The article is organized as follows. The next section reviews the relevant literature with a view on the two central concepts employed in this article – the state and offshore finance. It then presents the empirical results for Mexican individuals’ and firms’ demand for offshore financial services. In the third section I provide the historical institutionalist analysis of domestic politics and institutions. Drawing on the Weberian concept of the state as discussed in section two, the analysis concentrates on how state resources reflect and shape the power relationships between different groups in society. In section five, I discuss the theoretical implications of the findings. The final section concludes with a look ahead.

2. Contested concepts: offshore finance and state power

Before moving into the empirics, it is important to clarify what I mean when saying ‘offshore finance’ and ‘the state’. These concepts provide a mental short-cut for understanding a complex reality by organizing, naming and giving meaning to the features of a phenomenon (Berenskoetter, Citation2016). As such, employing a concept means to take one of a potentially infinite number of short-cuts. Being explicit about the conceptual route taken makes transparent the analytical added value and limitations of said concept. Likewise, we need to establish what we already know of the relationship between offshore finance and the state. These clarifications are the purpose of this section.

As a relatively novel concept in international political economy, the notion of offshore finance is contested for two principal reasons. First, we have a still fragmentary empirical understanding of the phenomenon. Second, determining which country is an ‘offshore financial center’ or, even more normatively charged, a ‘tax haven’ is an academically and politically controversial question. To stay clear of the politics of attribution, this article focuses on offshore financial services rather than offshore financial centers. Most scholars agree that these services share four central characteristics (see Palan, Murphy, & Chavagneux, Citation2010). These are (1) ring-fencing (i.e. offshore financial services are offered to non-residents only), (2) zero or low taxation and regulation, (3) opacity and (4) ‘calculated ambiguity’, to use Sharman’s (Citation2010, p. 2) words. Calculated ambiguity means that, thanks to offshoring, the answer to questions of wealth and legal status depends on who is asking it. For example, thanks to profit-shifting, a corporation can appear simultaneously indebted to the tax authorities and profitable to shareholders. Importantly, if done properly, both answers, though contradictory, are legally correct.

From the growing body of works on offshore finance we can learn why economic actors go offshore and where. The most important uses of offshore financial services are, according to the literature, (1) tax planning1 and regulatory arbitrage (Palan et al., Citation2010), (2) risk hedging with regards to currency volatility and weak rule of law (Black & Munro, Citation2010), (3) money laundering (Sharman, Citation2011) and (4) access to US-dollar denominated credit (McCauley, Upper, & Villar, Citation2013). The question of accessing US-dollar denominated credit offshore has been previously discussed by the literature on the Eurodollar (Burn, Citation1999; Helleiner, Citation1994) and resurfaced recently with a view on emerging market debt under the label of the ‘global dollar’ (McCauley, McGuire, & Sushko, Citation2015). The Eurodollar2 credit markets are offshore markets. Eurodollar credit is mediated between non-resident banks, the markets are little regulated and taxed, they are opaque – the true size of the Euromarkets remains unknown to banking statistics – and characterized by calculated ambiguity. A Eurodollar denominated security looks like a US-dollar denominated one, although it is not. It lacks access to the Federal Reserve’s lender of last resort function (Mehrling, Citation2016). Many offshore centers combine the offering of Eurodollar credit with the use of British common law, which tends to be more lenient toward debtors than US American law, making it particular attractive to emerging market borrowers (Norfield, Citation2016). Within that larger body of works on the Eurodollar, economic historians study the role of Eurodollar credits in the Latin American debt crises of the early 1980s and 1990s (see Altamura, Citation2017; Alvarez, Citation2015; Antzoulatos, Citation2002). This literature demonstrates that Latin American governments, with the Mexican leading the way, borrowed freely in the Eurodollar markets despite recognizing the unsustainability of their debt. They appreciated the offshore dollar as a source to finance infrastructure development (Altamura & Flores, Citation2016). Governments of creditor nations were no less eager for their banks to lend Eurodollar in return for their export industries’ participation in that development (Wellons, Citation1985). Among other factors, the convergence of interests of creditor and borrower country governments around the Euromarkets led to the spiraling of sovereign debt that triggered the crisis (Flores, Citation2015). The four types of offshore uses – tax planning, risk hedging, money laundering and access to Eurodollar – are discussed in separate strands of literature and, consequently, are rarely considered together. Finally, existing research on offshore finance could also show that, for reasons ranging from time-zone considerations to the nature of bilateral tax treaties, most offshore transactions are done in close-by centers (Blanco & Rogers, Citation2014; Haberly & Wójcik, Citation2015b).

Cognizant of the shifting meanings of the state and its sources of power across time and space as well as within the study of world politics (Finnemore & Goldstein, Citation2013), I suggest a notion of the state that helps frame the analysis of our question at hand. If the concept of the state does appear in the literature on offshore finance at all, it is predicated on Schumpeter and Goldscheid’s (1976) notion of the tax state (Genschel, Citation2005; Hood, Citation2003). Illuminating in many ways, the concept of the tax state overrates, however, taxation as the key source of state revenue. The state has not one but four principal ways to finance itself: it can tax its citizens; it can go into debt; it can earn money, for instance by selling its natural resources; or it can mobilize money from the outside e.g. through conquest. The modern state can be, among others, a tax state, a debt state, a rentier state or a predator state. Across time and place, the public finances of most modern states comprise a combination of different sources of income. Weber’s (Citation1994, p. 316) idea of the state ‘as an institutional association of rule (Herrschaftsverband), … which unites in the hands of its leaders the material means of operation’ recognizes, as Goldscheid and Schumpeter did, that revenue is a matter of life and death for the modern state. To uphold its power, the state can either employ coercive means or legitimate its rule such that citizens voluntarily accept state authority without the threat of punishment (Thompson, Citation2010). For both, coercion and legitimacy, revenue is central. It helps paying for internal and external security as well as for addressing citizens’ material interests. Importantly, however, unlike Goldscheid and Schumpeter, Weber leaves the actual sources of state revenue open. In the contemporary period, tax and debt are empirically the two defining, indispensable and intertwined funding sources with the other sources playing, if at all, a complementing role. As a result, most modern states are built around the power relationships between the government, its taxpayers and financiers (Bonney, Citation1999; Ingham, Citation2004; Vogl, Citation2015). These relationships are institutionalized in a country’s tax and banking systems. The tax system is the institutional expression of the power relationship between the government and the taxpayers. It articulates who must pay how much on the basis of which principles. The banking system is the institutionalized expression of the power relationship between the government and its financiers. It articulates who creates credit, who has access to credit and under which conditions (Calomiris & Haber, Citation2014, chap. 1). Yet, since the state only controls, but does not own these resources (Weber, Citation1994), public finances make the state dependent on those who hold the ownership: financiers and taxpayers. Borrowing from and taxing citizens are thus an expression of and a limit to state power (Ingham, Citation2004; Vogl, Citation2015). The power position of the government in relation to its financiers and taxpayers depends on the its ability to successfully mediate the central political conflict about how the costs and benefits of tax and debt are distributed between different groups of society (Calomiris & Haber, Citation2014; Levi, Citation1989). In essence, I consider state power to be the state’s ability to unite resources to finance its politics. In Weber’s parlance state power is an expression of the institutionalized association of rule’s settlement over how to finance the government and its politics.

This notion of the state has three implications for the subsequent analysis. First, the concept puts a spotlight on the material dimension of state power, de-emphasizing military, ideational or cultural dimensions. In combination with the empirical reality that most states finance themselves through tax and debt, my material perspective highlights the importance of the tax and banking systems as institutions to reckon with. Second, it emphasizes state autonomy, the ability of the state to act freely without external constraints, over state influence, the ability of the state to make others do what it wants (Cohen, Citation2013). This emphasis reflects that the state’s ability to extract resources from its citizens and to use them in an autonomous way is a precondition for the state to exert influence. The final implication is that, by building on Weber’s ideal type description of the state, my concept of state power is premised on historical developments in Europe. However, its core, the idea of the state as an institutional association of rule, allows accounting for the unique genealogy of a specific state, as the analysis of the Mexican state below shows.

Although not working with an explicit notion of the state and its sources of power, the literature on international taxation (see Swank, Citation2016a; Genschel & Schwarz, Citation2011 for literature reviews) is insightful in two ways. It has something to say, first, about the impact of offshore tax planning on the state and, second, about the domestic politics and institutions that potentially condition this impact. Economists estimate that due to offshore tax planning countries collectively miss out on US$240 billion in corporate tax revenue per year (Tørsløv, Wier, & Zucman, Citation2017). While this number is impressive, research on international tax competition also established that financial globalization has not ‘fatally undermine[d] the tax state’ (Genschel, Citation2005, p. 53). It has, though, altered the terms of settlement between different groups of society over who has to pay how much tax: across the globe, tax reform has shifted the tax burden from capital to labor (Genschel, Citation2005; IMF, Citation2014). However, these effects of tax competition are not equally distributed across countries. Researchers found that large countries are more affected than small ones (Genschel & Seelkopf, Citation2016). Furthermore, on an aggregate level, developing economies – both low and middle income countries – are more affected by offshore finance than developed ones (Crivelli et al., Citation2015; Genschel & Seelkopf, Citation2016; Kar & Schjelderup, Citation2015; Swank, Citation2016a). Cobham and Janský (Citation2017) estimate that developing economies lose 6–13% of their total tax revenue to base erosion and profit shifting, while developed economies lose about 2–3%. In addition, it appears uncontroversial that open economies with a high degree of capital mobility are more affected than closed ones (Wibbels & Arce, Citation2003; Zucman, Citation2013). Finally, Genschel, Lierse, and Seelkopf (Citation2016) find that badly governed countries suffer more from tax competition than well governed ones. According to the literature of international taxation, these different effects of tax competition on the state’s autonomy to tax are conditioned by domestic politics and institutions. Voter opposition toward policies that benefit capital, the preferences of veto players in the legislative process, quality of governance and the level of public debt – these are among the domestic institutions that condition the effect of capital mobility on domestic tax policies (Basinger & Hallerberg, Citation2004; Genschel & Seelkopf, Citation2016; Swank, Citation2016a).

Importantly, however, by its very nature, the literature on international taxation can only speak to a part of the phenomenon: offshore tax planning. Yet, offshore financial centers are usually both, tax havens and international banking hubs. Offshore financial services therefore include tax planning and offshore money creation, for instance in form of creating Eurodollar credit. As such, offshore financial services can potentially affect the state’s ability to finance its politics through two channels: taxation and banking. Against this conceptual background, the next section presents the empirical evidence for offshoring in Mexico.

3. The limited uses and abuses of offshore finance in Mexico

As noted above, Mexico is a crucial case. The causes identified by the literature that may explain which countries are affected by offshore finance – size, economic openness, level of development, geographical proximity to offshore financial centers and governance – are present in the Mexican case in a pronounced manner. It is a large country, geographically and economically. Mexico is Latin America’s second largest economy and its most open one. In 2015, for instance, Mexico’s gross domestic product (GDP) was US$1.14 trillion and its currency, the Mexican peso, was the most traded emerging market currency in the world. It was overtaken by the Chinese renminbi only in 2016 (Cota, Citation2015). Despite its economic weight, though, Mexico is also a developing country. Given the country’s extreme levels of inequality, the fact that its per capita income puts Mexico into the group of upper middle-income countries disguises that most Mexicans face classical developmental problems. These include absolute poverty, limited access to public services such as health care, education and basic physical safety (World Bank, Citation2017). In addition, most Mexican individuals and corporations have no access to credit or generally to banking services (CONAIF, Citation2016). Mexico is also a country with endemic problems of crime and corruption and is located closely to the Caribbean, one of the world’s largest offshore hubs.

To understand why economic actors go offshore, we need to first gauge the scope and pattern of their demand. However, quantifying the uses of offshore services is notoriously difficult. Most researchers chose one of two approaches. They either focus on one proxy indicator, say foreign direct investment (FDI) (see Fichtner, Citation2015; Haberly & Wójcik, Citation2015a; UNCTAD, Citation2015), or they combine different macroeconomic indicators to create a global view on the size of offshore finance (cf. Alstadsaeter, Johannesen, & Zucman, Citation2018; Tørsløv, Wier, & Zucman, Citation2018). The first approach is statistically coherent but incomprehensive. The second approach is comprehensive, but combining different statistics means to combine their shortcomings. This is increasingly problematic given that the quality of macroeconomic statistics is deteriorating precisely because of the offshore phenomenon (Linsi & Mügge, Citation2017).

Considering these shortcomings, for the purpose of this article I decided to work with bank data from the Bank for International Settlements (BIS). The advantage of bank data is its balance sheet approach. That is, rather than dealing with contested concepts and their appropriate statistical expression, bank data records how money changes its location on the balance sheet as cross-border economic activity unfolds. Moreover, Mexico’s central bank data is of high quality.3 Needless to say, the BIS data has its own limitations. To begin with, the BIS list of offshore financial centers excludes European ones, such as Switzerland or the Netherlands. My estimates add to the BIS list the missing European jurisdictions identified by Garcia-Bernardo, Fichtner, Talks, & Heemskerk (Citation2017).4 Next, some countries have sub-national offshore financial centers. Prominent examples are Delaware and Nevada in the United States. The BIS data does not cover them and hence do not find their way into my estimates. Finally, BIS data misses out on financial transactions that are off-balance sheet. For instance, fiduciary funds and trusts, two asset-holding structures popular for offshoring assets, are largely off a bank’s balance sheet (Harrington, Citation2016; Zucman, Citation2013). The BIS data provides us with a coherent idea of the face of the offshore system while being oblivious to its underbelly. Evidently, the opacity of offshore finance limits the explanatory power of purely quantitative analyses; not least because the data can show the scope of, but not the motivation for offshoring.

To strengthen the empirical evidence, I collected new data through in-depth interviews with experts of offshore finance. The interviews were conducted in Mexico City in November 2015 under the condition of anonymity. They were designed as open-ended, semi-structured interviews. In combination, the interviews and the BIS data create a solid empirical basis to determine the scope of and motivation for going offshore.

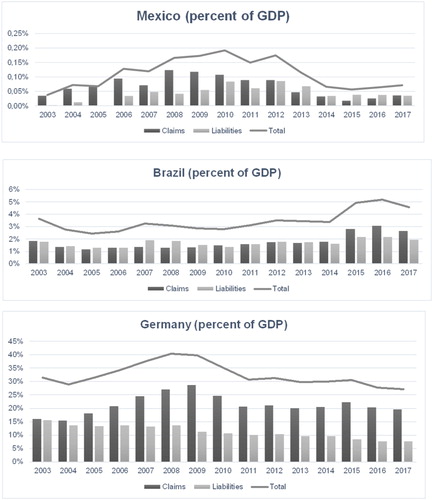

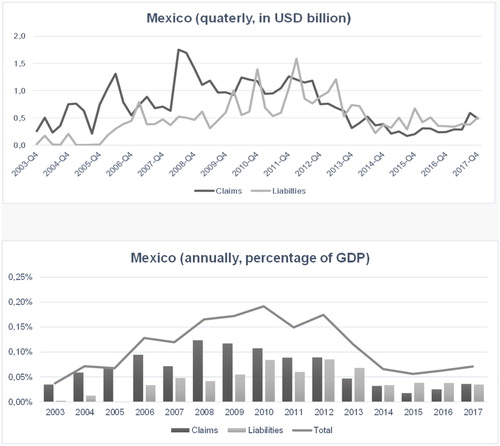

According to the BIS locational banking statistics, Mexican demand for depositing assets offshore (claims) and issuing debt there (liabilities) developed between 2003, the beginning of BIS data for Mexico, and 2017, the latest data available, as depicted in .5

Figure 1. Demand for offshore financial services in Mexico.

Source: BIS, World Bank, own calculations.

As shows, with a maximum of US$1.8 billion, the financial flows are overall small in volume, and volatile. What we can see here are mostly individual transactions. The interviewee from the central bank could even recall the banks responsible for each of the larger transactions (author’s interview). summarizes the minimum and maximum value of offshore assets and debt between 2003 and 2017 as absolute amount and as percentage of GDP.

Table 1. Overview of the scope of Mexico’s offshore demand (2003–2017).

As offshore deposits and debt affect the state differently but collectively, also indicates the total adding up assets and liabilities in relation to GDP. To put this amount in context, compare it with the value of Mexican onshore foreign assets and external debt. Foreign assets amount to 30% (Lane & Milesi-Ferretti, Citation2007), external debt to ten to 20% of GDP (Banco de México, Citation2017) during the same time. It is also instructive to put Mexico’s scope of offshoring in context to that of other countries (see ). Take for instance, Brazil. Brazil is similar to Mexico in size, level of development and the governance challenges. Brazil is different, though, in two aspects. Its economy is less open, and the country is not close by any major offshore financial center. We would hence expect Brazil’s scope of offshoring in relation to the size of its economy to be equal to or even lower than Mexico’s. Yet, Brazil displays a demand for offshore financial services of 4–5% of GDP – about 20 times more than Mexico. Or take Germany, conventionally considered one of the prime users of offshore finance (Zucman, 2017). Like Mexico, it is large6, has an open economy and is geographically close to offshore financial centers. Unlike Mexico, it has limited governance problems and a higher level of development. According to the literature, we should expect Germany to display lower levels of offshoring than Mexico. Yet, as conventional wisdom has it, Germany’s offshore demand is huge, ranging between 28% and 40% of GDP.

The interviews confirmed the limited scope of offshoring in Mexico. The users of offshore financial services are foremost the country’s seven largest banks, the eight largest business conglomerates and PEMEX, the state-owned oil and gas company (author’s interviews). The interview partner from the central bank confirmed: ‘Mexican corporations’ cash, to the best of our knowledge, resides locally or is invested sometimes in some offshore center, but that is a very small part of it.’ Another interviewee, reflecting the high level of externally held onshore assets pointed out that ‘a lot more money is … parked in apartments in Miami than it is in Jersey or the Bahamas.’ This quote brings us back to the role of United States’ sub-national offshore financial centers. With no income tax on individuals and trusts, a very low state estate tax, no inheritance and no gift tax, Florida is certainly a low-tax jurisdiction. However, it is not an offshore financial center as understood in this article. The favorable tax laws are not exclusively provided to non-residents, but also to United States citizens (no ring-fencing). Furthermore, Florida is not among the country’s secrecy jurisdictions. According to the financial secrecy index these are Delaware, Nevada and Wyoming (Tax Justice Network, Citation2018). These US offshore financial centers have not been mentioned in the interviews at all and hence there is neither quantitative nor qualitative data on their importance for Mexican firms and individuals. Finally, with a good three-hour flight from Mexico City, the wealthy indeed spend time in their Miami apartments (author’s interviews). The Miami holiday home for rich Mexicans is the equivalent to the Swiss Chalet for rich Germans. The line between capital flight and offshoring can be a fine one.

According to the interviews, among the four typical uses of offshore financial services established in the literature – tax planning, risk hedging, money laundering and access to Eurodollar – risk hedging and offshore debt issuance are the two most important motivations for Mexican economic actors to go offshore. These preferences are reflected in the increase of offshore assets during the 2007–2009 Financial Crisis and the slight increase of offshore liabilities relative to offshore assets since 2012 (see ). However, the interviewees also maintained that offshore tax planning is usually part of a financial transaction that serves a different purpose. A currency swap, for instance, is structured to simultaneously avoid taxation (author’s interviews). Finally, offshore financial services are not the services of choice for criminals. Drawing on cash and informality, they rather use classical onshore money laundering schemes to white-wash their illegal proceeds (author’s interviews).

Clearly, the uses and abuses of offshore finance in Mexico are a limited affair. These findings cannot be explained by the variables of size, economic openness, level of development, proximity to offshore centers and governance problems as discussed in the literature. They hence warrant explanation.

4. Power without plenty: taxation and banking in Mexico

An answer to the conundrum may lie, as the international taxation literature suggests, in domestic institutions. The following section presents a historical institutionalist analysis that explains why Mexican individuals and firms do not systematically go offshore. Following from the material perspective taken in this article, the central conflict of interest is around the question of how to finance the state. In the following, I show how the answer to this question in Mexico developed and changed over time and how its contemporary form explains the low demand for offshore financial services.

4.1 Historical roots

Mexico became independent from Spain in 1821, but it took another 50 years for the federal republic to stabilize, centralize and exert territorial control in a manner that justifies speaking of Mexico as a modern state. It was during President José Porfirio Díaz’s autocratic reign from 1877 to 1911, often referred to as the Porfiriato, that an association of rule institutionalized and united enough resources to finance the state. The cornerstone of that association was the president’s partnership of interest with Mexican financiers. He convinced them to lend to his government in return for rents that arose from direct involvement in policymaking, deliberate restrictions on competition and selective enforcement of property rights. Díaz’s ‘crony banking system’, as Calomiris and Haber (Citation2014, p. 337) term it, proved successful. Though small, it was stable and provided the resources to finance industrialization. Moreover, by the 1890s, it made Mexico, the hitherto chronic defaulter, the country with the best credit rating in Latin America (Knight, Citation1990). Díaz had found a formula to finance the state without taxing the wealthy. Yet, his approach would not have been sustainable in the long run were it not for Mexico’s mineral wealth. During the Porfiriato, the government already sought to develop the oil industry. Yet, it took the US American and British investors a decade of exploration before they could start drilling toward the end of the 19th century. Likewise, Díaz’s tax revenues remained marginal. It was indeed his government’s access to domestic credit that helped him stabilize the budget. During the Porfiriato, the Mexican state, in Weber’s sense of an institutionalized association of rule, consisted of the president, his closest political allies and a handful of bankers and big businesses (Carmagnani, Citation1994; Knight, Citation2013). The rural poor and the urban middle classes, the overwhelming majority of Mexicans, were excluded from that association. But, they had to pay, directly or indirectly, for the rents that sustained Díaz’s partnership with the bankers (Calomiris & Haber, Citation2014). The resulting problem of legitimacy was solved – or rather postponed – through coercion and violence (Centeno, Citation2002; Smith, Citation2014).

In November 1910, the educated middle classes eventually joined forces with the rural poor in protest over Díaz’s reign and took to the streets. Their protests ignited the Mexican Revolution, a 10-year armed struggle over political participation (Hamilton, Citation1982). Despite the armed conflict, profitable oil drilling in Mexico gained steam during the revolution and in the 1920s the country eventually emerged as one of the world’s largest oil producers (Haber, Maurer, & Razo, Citation2003). As a result, tax revenue from oil increased from about 1% in 1912 to 5% in 1917, the year of Mexico’s new constitution (Haber et al., Citation2003). From the early 1920s onwards, the petroleum industry contributed about one third of government revenue (Aboites, Citation2003; Hall, Citation1995).

In 1920, members of Mexico’s old elite seized power and brought the revolution to an end. They understood that the new regime needed a popular base. They created a one-party system and co-opted popular movements – small farmers, organized workers, and unionized public employees – into the emerging Partido Revolutionario Institutional (PRI)7. The country’s economic elites, in contrast, were not included into the PRI’s platform. Rather, the PRI corrupted big businesses individually (author’s interview). To unite resources to finance the state, the new government resurrected Díaz’s partnership of interest with the bankers. The banking system was again small, but functional in terms of lending to the government (Banco de México, Citation2018; Calomiris & Haber, Citation2014). The post-revolutionary Mexican state was an institutionalized association of the PRI, the bankers and the leaders of the co-opted social movements. The glue that held that association together was a system of selective privilege and patronage. The government provided the economic elites with decision-making power, monopoly rents and tax exemptions in return for investment and access to credit. In the same vein, the party offered its popular base political influence, welfare programs, tax exemptions and social mobility. Their leaders had on top opportunities for personal enrichment. All of it in return for political loyalty (Haber, Klein, Maurer, & Middlebrook, Citation2008; Knight, Citation1990). The system of privilege and patronage ensured the PRI’s quasi-total power from 1928 to 1997. The post-revolutionary state was, again, built on debt. Yet, the system of privilege and patronage was expensive. Taxing the wealthy or the co-opted social groups was politically unfeasible. Taxing the foreign-owned oil companies was hence a welcome source of government revenue. To make even more of it, the PRI made finally good on one of the new constitution’s central promises. It nationalized the oil industry in 1938. The government expropriated the foreign-owned petroleum firms and merged them into one large state-owned company, Petróleos Mexicanos or PEMEX for short. Next to PEMEX other central industries were also nationalized, though in a less dramatic fashion. Through the continuous acquisition of stocks the government became either a minority or a majority shareholder of firms in the railway, tourism, telecommunication and other sectors (MacLeod, Citation2005). The rents and taxes from petroleum and other nationalized industries created the basis for a tax system characterized by a low overall tax burden, in particular on capital (Haber et al., Citation2008). This tax system allowed the PRI to avoid political conflict with its power base. Between the 1950s and the early 1980s, it generated about two thirds of the average tax revenue typical for other Latin America countries. Before the mid-1970s the state’s revenue was constantly less than 10% of GDP. With Mexico’s increasing income from oil revenues throughout the late 1970s and early 1980s the ratio increased to about 15% of GDP. However, over time the costs for the system of patronage and privilege continued to rise. By the 1970s, debt began to outpace revenues. The government urgently needed more and cheaper money than the small domestic banking and tax systems could provide (Calomiris & Haber, Citation2014, chap. 11; Smith, Citation2014).

The PRI was lucky. Rising oil prices and new discoveries in the Mexican Gulf in the early 1970s allowed the government to increase its borrowing in international financial markets (Haber & Musacchio, Citation2013). Equally important, a banking reform in 1974 allowed Mexican banks to internationalize. They used the deregulations to go offshore and get credit in the Euromarkets. Having access to international interbank loans, Mexican banks expanded their domestic lending activities to the government and public corporations. Intermediating loans between offshore banks and the Mexican government turned out to be a profitable business. Interest rates in the Euromarkets were about 40–60% lower than domestically. Domestic banks borrowed cheap and lent on at a higher price. The rents through arbitrage were steep (Alvarez, Citation2015).

However, when oil prices collapsed in 1982, the offshore Eurodollar bonanza came to sudden end. Unable to serve its US-dollar-denominated debt, the government had to sign a moratorium and to negotiate a restructuring of its debt in return for a domestic adjustment program. The debt crisis rang in Mexico’s decada perdida and the demise of the PRI’s rule. To avoid a collapse of the Mexican banking system, the PRI nationalized the banks. With the stroke of a pen, the long lasting partnership of interest between the government and Mexican bankers was finished (Calomiris & Haber, Citation2014). As part of the negotiation between the Mexican government and its international creditors a new financial instrument was created in 1991, the so-called Floating Rate Privatization Note, a direct obligation of the Mexican government (Alvarez, Citation2015). As the government intended to stem the withdrawal of the propertied classes from domestic credit markets by re-privatizing the banks in 1991, the holders of the Note could use it to purchase shares in Mexican banks. In addition, the PRI offered the financiers unlimited insurance against any loss the banks may incur in the future. This offer proved so attractive that the bankers were willing to pay three times the book value to purchase the 18 banks on offer (Calomiris & Haber, Citation2014). Facing little risk thanks to the bailout-guarantee and having access to the interbank market through the Floating Rate Privatization Notes, Mexico’s banks were back offshore in the early 1990s. During that time, Mexican economic actors were starved for credit to finance the lucrative acquisition of the public companies that were, with the notable exception of PEMEX, privatized as part of the adjustment program. This time around, the banks intermediated credit between offshore banks and Mexico’s private sector. Mexico’s big business moved from being net creditors in 1990 to being net borrowers only one year later (Antzoulatos, Citation2002). The banks channeled Eurodollar liquidity into Mexican corporations, even if those corporations had mainly peso-denominated assets. When the peso collapsed in December 1994, nearly halving in value against the US dollar, Mexican firms’ Eurodollar loans doubled in value within a few days. The firms could not serve their debt. The banks collapsed. Only three years after re-privatization, the government nationalized the banks yet again. The bailout cost the country about 15% of GDP and transferred money from Mexican taxpayers to bank stockholders, some of Mexico’s wealthiest individuals. The bailout killed the relationship between the PRI and its popular base. The PRI lost power first on the local level in 1997 and then on the federal level in 2000. Bracing for the PRI’s demise, the government attempted to spur economic growth, for which it needed a new partnership with the bankers. As the relationship with the domestic financiers was ruined, the PRI turned to foreigners. In 1996, for the first time since the Porfiriato, the government allowed unrestricted foreign bank ownership. It took only a few years for the largest Mexican banks to be owned by foreign investors, particularly from the United States (Haber et al., Citation2008).

Beginning in 1982, the demise of the PRI’s power was a long process culminating in the loss of the presidency in 2000. During this long transition from a one- to a multi-party system, formal power in Mexico changed fundamentally (Camp, Citation2015). Yet, the informal power networks between the government, the wealthy and the co-opted social movements, built through the system of privilege and patronage, persisted. Despite political competition the relationship between the government and the citizens continued to be mediated by ‘political brokers’ as Selee (Citation2011, p. 170) puts it. Political opinion- and decision-making remained a process of intermediation through private networks, rather than parties and parliament. Mexico’s democracy is more clientelistic than representative. In other words, despite democratization the nature of the Mexican state changed little (Selee, Citation2011).

4.2 Contemporary shape

The institutional association of rule continued to consist of the ruling party, the wealthy and organized interests. Though broader than during the Porfiriato and PRI reign, the association of rule remains a small and closed circle still excluding most Mexicans from politics. As one interviewee put it:

Most Mexicans consider the state as something that is external to them. The state is a set of institutions, which are controlled by a small group of people. That is, you have two options. Either you become part of the state controlling group, which is difficult, or you stay away from the state as far as possible.

The simplest way to stay away from the state is informality. Mexico has Latin America’s largest informal economy (ILO, Citation2014) and ordinary Mexicans see it as a means to counterbalance the highly concentrated economic power in the formal system (author’s interview). With the exclusive institutionalized association of rule intact, Mexico’s oligopolistic economy persisted too. Díaz’s approach of financing the state through debt backed up by monopoly (and later oil) rents has been reinforced by the PRI through centralizing and nationalizing core industries and then re-privatizing them in a non-competitive manner.

Yet, it would be misleading to emphasize institutional continuity without pointing to institutional change too. The end of the partnership of interest between the Mexican government and its domestic financiers in the 1990s and the subsequent internationalization of the financial sector profoundly disrupted banking. Mexico became the country with the most rapid and far-reaching penetration of foreign banks in the world (Haber & Musacchio, Citation2013). In 1991, foreign banks owned 1% of assets; by 2013, that number had grown to 74%. The entry of foreign banks made Mexico’s banking system more stable, with access to credit for corporations and households more easy and cheap (Haber & Musacchio, Citation2013). Still, financial inclusion remains small and concentrated. Only 39% of adults have a bank account (CONAIF, Citation2016) with seven banks accumulating 73% of market share (Díaz-Infante, Citation2013).

As the banking system developed from domestic-owned to foreign-owned, the issuance of Mexican sovereign debt developed in the opposite direction. Before the Mexican financial crises, 70–80% of debt was issued abroad, most of it offshore. Today that amount is issued domestically (author’s interviews). The big change is that the debt is now denominated in Mexican pesos and held by foreign banks in Mexico (Banco de México, Citation2014). In the past it was US-dollar-denominated and intermediated by Mexican banks in offshore financial centers. Likewise, the private sector became much more restrained in borrowing in US dollar. Mexico’s retreat from the US dollar significantly reduced the public and private sectors’ past demand for Eurodollar and the related currency risk. Should an economic actor (e.g. PEMEX) be in need for US dollar credit, the US American owned banks in Mexico can intermediate it directly in the US onshore economy. There is no longer a need for using offshore Eurodollar.

The picture of contemporary taxation in Mexico appears different, though. The Porfiriato, the revolution, the over 70 years of PRI power and democratization – all did not fundamentally change the association of rule’s preference of how to structure taxation. Mexico has still the OECD’s lowest tax-to-GDP ratio. In 2016, its tax revenue amounted to 17% of GDP compared to the OECD’s average of 34% and Latin America’s 22%8 (OECD, Citation2015, OECD, Citation2017). Taxes on personal income make up a smaller proportion of tax revenue than in any other OECD country (OECD, Citation2017). As in previous times, the wealthy elite is spared from contributing more significantly to the state’s treasury (Sobarzo, Citation2011). Likewise, social security contributions account for a much smaller share in the tax mix, expressing the association of rule’s limited willingness to contribute to the welfare of the larger population (author’s interviews). Mexico’s nearly entirely privatized health, pension and social security systems create lower government spending than either in the OECD or in other Latin American countries (OECD, Citation2015). Next, consumption taxes make up about 39% of the tax revenue. This share is lower than the Latin American average of more than 50% (OECD, Citation2015), but is an explicit attempt by the government to tax poor people in Mexico’s informal economy (author’s interview). Finally, with a 20% share of tax revenue, corporate income taxes contribute more to Mexican revenue than they do in the rest of the OECD world.

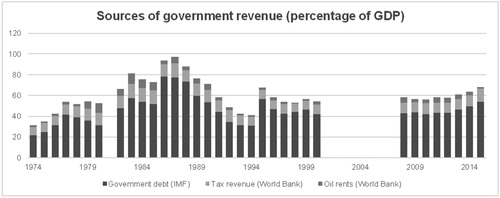

Unsurprisingly, the high corporate tax rates are matched by equally high rates of tax avoidance. Businesses negotiate through the informal networks individual tax exemptions at the municipal and state levels (author’s interviews). These exemptions add up to a considerable tax loss at the federal level (San Martín, Juárez, Díaz & Angeles, Citation2016). The resulting shortage of tax revenue is offset, again as in previous times, by tax and rents generated through state-owned PEMEX and, more importantly debt, as demonstrates.

Figure 3. Government revenue 1974–2015 (percent of GDP). Source: IMF, World Bank, own calculations.

Note: The oil rents are only indicative for the volume of government oil revenue. Not all oil rents are automatically government revenue. The government levies tax on the oil rents and as the owner of PEMEX receives all profits that are not reinvested. The Mexican government does not publish an exact breakdown of oil revenue data.

We can see that over time, it is the volume of sovereign debt that drives the overall level of state revenue. The proportion of tax revenue and oil rents, in turn, remains fairly stable. The still exclusive association of rule continues to prefer financing the state via debt. As in the past, Mexico’s tax state is deliberately weak. Consequently, it limits the demand of corporations and wealthy individuals to go offshore. Moreover, 60% of Mexican tax revenue comes from consumption taxes, social security contributions and other indirect taxes (OECD, Citation2017). These taxes do not lend themselves to being evaded offshore. Mexicans dodge them through the informal economy (Buehn & Schneider, Citation2016).

Informality explains the limited demand for offshore money laundering services too. It makes Mexico a largely cash-based economy (Del Angel, Citation2016). The use of cash, internationally going down, is on the rise in Mexico (FATF & GAFILAT, Citation2018). This creates formidable spaces for onshore money laundering. For instance, paying workers without a bank account in cash is a cheap and efficient way for firms to keep financial flows below the radar of ‘know your customer’ processes (author’s interview). Although the Mexican authorities are well-aware of onshore money laundering schemes and have highly developed systems to detect them, law enforcement is wanting (FATF & GAFILAT, Citation2018; author’s interviews).

In sum, the low level of contemporary offshoring in Mexico can be explained by the exclusive nature of the Mexican state that shaped banking and taxation in the interest of the country’s elite. The narrow banking system first led to an engagement with the offshore Eurodollar markets and then after two deep financial crises to the withdrawal from them. The tax system limits the tax burden on the wealthy and organized interests. The excluded majority responds to the economic and political concentration of power with informality, which provides similar opportunities for tax planning and money laundering as offshore financial services; only it spares the legal sophistication associated with offshoring.

5. Tax and debt make the state

These findings have two theoretical implications for the study of offshore finance. First, it highlights the role of politics and institutions in shaping the relationship between offshore finance and the state. Furthermore, it underlines the importance of employing an explicit concept of the state to understand the underlying power relationships between the government, its financiers and taxpayers. This section discusses both theoretical implications in turn.

The finding that Mexican economic actors go offshore to a limited extent because there is no need to, questions the conventional assumption that the use of offshore financial services affects state power. In fact, in the Mexican case, the reverse is true: the configuration of state power conditions the level of offshore demand. This reversal of cause and effect is the reason why structural variables – size, economic openness, proximity to offshore financial centers and level of development – cannot explain Mexico’s low level of offshore demand. Institutions and politics, however, can.

The Mexican case supports the international tax literature’s assertation that domestic politics and institutions matter. Moreover, it adds insights about which institutions matter and how. As discussed above, the international taxation literature identifies voter opposition toward policies that benefit capital, veto players in the legislation process, level of public debt and quality of governance as institutions that condition the effect of globalization on taxation (Basinger & Hallerberg, Citation2004; Genschel & Seelkopf, Citation2016; Swank, Citation2016b). The case of Mexico demonstrates that while these institutions do matter, they do so differently than hitherto thought.

Take voter preference or more generally regime type to begin with. In the Mexican case its explanatory power is limited. Here, institutions are formally democratic, but opinion- and decision-making are organized through private informal networks rather than parties and parliament. As a result, the effect that democratization leads to a preference of median voters for higher taxation on the wealthy (see Genschel et al., Citation2016; Meltzer & Richard, Citation1981) cannot be observed. The exclusive nature of the institutionalized association of rule throughout the country’s history helped elites to find ways to finance the state that are in line with their interests rather than with that of the median voter. This observation echoes Tocqueville’s (Citation2002) insight that alongside universal franchise it is wealth distribution that conditions taxation and spending. Next, the Mexican case confirms veto players as important institutions. Díaz’s partnership of interest with the bankers and the PRI’s system of patronage and privilege established enduring veto players for all decisions related to the financing of the state. Their influence explains the deliberate smallness of Mexico’s tax state and the structure of its sovereign debt. Likewise, sovereign debt is an important institution shaping the relationship between state power and offshore finance. Yet, the case of Mexico suggests that ownership structure and currency denomination have more explanatory power than the volume of debt. The only time when Mexican economic actors used offshore financial services was when Mexican banks could intermediate US-dollar-denominated credit by going offshore. Finally, the case of Mexico suggests that bad governance plays its role too. Yet, unlike argued in the literature, in Mexico bad governance, expressed in form of informality, curbed offshoring by creating onshore havens for tax planning and money laundering.

In short, the exclusiveness of the Mexican state undermines the power of the median voter and strengthens that of the veto players, who align the structure of public finances with their interests. Informality is a popular response to this concentration of economic and political power and creates spaces for shady services otherwise only available offshore.

Next to institutions, this study established that conceptualizing state power matters too. Here, approaching it from the perspective of Weber helped to uncover how the interests of different social groups shape taxation and banking and how this, in turn, affects the demand for offshore services. With a view on European history, scholars found that sovereign debt could turn into a central source of public finance only because the growing costs of external warfare made general taxation both necessary and possible. By the beginning of the nineteenth century, European states could borrow at unprecedented levels because constant and significant tax revenues ensured the state’s ability to repay and thus the creditors' willingness to lend (Macdonald, Citation2003; Schumpeter, Citation1991; Tilly, Citation1990). The tax state precedes the debt state.

The historical development of Mexico’s public finances, however, displays that tax and sovereign debt can also institutionalize in reverse order. The state can go into debt before seizing significant amounts of tax revenue. This is possible if a third source of income is large enough to offset the lack of tax revenue as collateral for the state’s financiers. In the case of Mexico, this third source were monopoly and oil rents. The sequencing matters. It institutionalized the relationship between the Mexican government and its financiers first and with the taxpayers second. The government-banker relationship has always been more central to the financial survival of the Mexican state than the government–taxpayer relationship. The chronology of how taxation and banking institutions developed help explain why today Mexicans use offshore financial services sparsely. Yet, as the historical analysis demonstrated too, this has not always been the case. Between the 1970s and the 1990s, the Mexican public and private sectors did go offshore in a substantial manner to issue debt. The withdrawal from the Eurodollar markets in response to two severe financial crises shows the centrality of banking in determining the level of offshore demand in Mexico. The literature’s focus on European states and their path to modernity may explain the emphasis on taxation at the detriment of sovereign debt as a defining element of the modern state. In a diversified perspective, it is tax and debt that make the state.

6. Conclusions

According to conventional wisdom, offshore finance conditions state power. The higher the use of offshore financial services, the more limited the state’s autonomy to finance its politics. This causal relationship is, according to the literature, particularly strong for large, developing states with an open economy, governance problems and a geographical proximity to offshore financial centers. Now, the Mexican case demonstrated that the reverse can be true too. The nature of state power conditions the level of offshore demand.

Across time, Mexico’s institutionalized association of rule has preferred to finance the state via debt, backed by rents, rather than tax revenue. Today this preference expresses itself in two ways: in a foreign-owned banking system that provides peso-denominated credit and in a low tax burden on capital. Mexico’s high concentration of political and economic power is opposed by a large informal sector. It provides the opportunity to avoid and evade taxes as well as to launder money. In combination, there is little need for Mexican individuals and firms to go offshore. Counter-intuitively, the structure of bank ownership has been more consequential for the level of using offshore financial services than formal democratization. Yet, the historical analysis revealed that the low level of offshore demand suggested by current data is a snapshot of a process, not a static, universal fact. While tax planning and money laundering stayed mostly onshore throughout time, the Mexican government and corporations did issue debt offshore. This variance raises the question about the future level of Mexican offshoring.

The future is, of course, difficult to predict. Nevertheless, history provides directions for where to expect continuity and where to expect change. According to the analysis presented here, the coming level of offshore demand is a function of the government–financier and the government–taxpayer relationships. Given that Mexico’s current president Andrés Manuel López Obrador, announced to leave banking laws untouched (Villamil & Martin, Citation2018), the decisive factor for the government’s relationship with its financiers will be the structure of Mexico’s debt. For now, the government continues to borrow domestically in peso and, according to the central bank, will continue to do so (author’s interview). It might be another matter for the private sector, though. After the 2007–2009 Financial Crisis, which affected the Mexican banking system little, Mexican firms found it easy to issue US-dollar-denominated debt. Unlike in the past, however, the financing was supply driven and came from onshore US markets. It is unrelated to the offshore Euromarkets (author’s interview).

Regarding taxation, the level of future offshoring hinges on oil revenue and the persistence of informal power. Drops in oil prices or output will pressure the Mexican government to increase tax levels, while a raise may omit a higher tax burden. Whether a higher tax burden would fall on the wealthy or the poor depends, in turn, on whether Mexico’s democracy develops more into a fully representative system that channels median voter preferences into parliamentary decision-making. Yet, if the citizens’ preferences continue to be mediated through informal private networks, it is unlikely that the tax system will substantially change any time soon (author’s interview). With external factors being equal, there is little reason to assume a higher demand for offshore financial services in Mexico soon.

In the future, as in the past, Mexico may simply be an outlier case. As such, a single case cannot serve as a basis of generalization. Yet, it can serve as an argument for complementing aggregate level studies with country-level analyses. Providing important insights, the aggregated studies so far missed out, for instance, on banking as a social institution to reckon with. One reason for that omission might be that contemporary scholarship avoids an explicit concept of the state and its sources of power. In the rare cases where it has one, it anchors in largely European and Anglo-American experiences. Yet, the Mexican case shows that it matters that Porfirio Díaz forged a partnership with the bankers before establishing a modern tax system. This chronology laid the foundations for a modern state more deeply shaped by debt than by tax. A debt state au fond, the exclusionary political and economic structure of the contemporary Mexican state is still skewed in favor of capital at the detriment of the larger population. With so much rents to be had, there is little reason for large firms and wealthy individuals to bother going offshore.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Andrea Binder

Andrea Binder is a PhD candidate at the University of Cambridge, United Kingdom, and a non-resident fellow at the Global Public Policy Institute in Berlin, Germany. Her research focuses on the international political economy of offshore finance and on humanitarian politics.

Notes

1 I use tax planning as an umbrella term for tax avoidance and evasion. The difference between the two is often difficult to determine in practices as tax avoidance schemes are deliberately created to operate in legal grey zones.

2 I use the term Eurodollar instead of global dollar, because Eurodollar is more widely used in the international political economy literature.

3 BIS banking statistics depend on the reporting of member central banks.

4 An exception is Britain, which Garcia-Bernardo et al. (Citation2017) identify as an offshore financial centre, while most authors, including me, do not (see Gravelle, Citation2015; Johannesen & Zucman, Citation2014).

5 All numbers are cross-sector (including corporations, households and the government).

6 Obviously, Germany is much smaller than Mexico. Large here is meant in comparison to standard offshore centres such as Luxembourg or the Cayman Islands.

7 The party was first named Partido Nacional Revolucionario, then Partido de la Revolución Mexicana and since 1946 trades under the current name of Partido Revolutionario Institutional.

8 Numbers for Latin America are from 2014.

References

- Aboites, L. (2003). Excepciones y Privilegios: Modernización Tributaria y Centralización En México, 1922–1972. (1st ed.). México: El Colegio de México, Centro de Estudios Históricos.

- Alstadsaeter, A., Johannesen, N., & Zucman, G. (2018). Who owns the wealth in tax havens? Macro evidence and implications for global inequality. Journal of Public Economics, 162, 89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2018.01.008

- Altamura, C. E. (2017). European banks and the rise of international finance: The post-Bretton Woods Era. (1st ed.). London, New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Altamura, C. E., & Flores, J. H. (2016). On the origins of moral hazard: Politics, international finance and the Latin American debt crisis of 1982 (Paul Bairoch Institute of Economic History Working Paper No. 1/2016). Geneva: Université de Genève. Retrieved from Paul Bairoch Institute of Economic History website: https://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:82509.

- Alvarez, S. (2015). The Mexican debt crisis Redux: International interbank markets and financial crisis, 1977–1982. Financial History Review, 22 (1), 79–105. doi: 10.1017/S0968565015000049

- Antzoulatos, A. A. (2002). Arbitrage opportunities on the road to stabilization and reform. Journal of International Money and Finance, 21 (7), 1013–1034. doi: 10.1016/S0261-5606(02)00017-7

- Banco de México. (2014). Financial system report. Mexico City: Banco de México.

- Banco de México. (2017). Balance of payment statistics. Retrieved from http://www.banxico.org.mx/SieInternet/consultarDirectorioInternetAction.do?accion=consultarCuadro&idCuadro=CE101§orDescripcion=Balanza%20de%20pagos&locale=en.

- Banco de México. (2018). The history of coins and banknotes in Mexico. Mexico City, D.F.: Banco de México. Retrieved from http://www.banxico.org.mx/billetes-y-monedas/material-educativo/basico/%7B2FF1527B-0B07-AC7F-25B8-4950866E166A%7D.pdf.

- Basinger, S. J., & Hallerberg, M. (2004). Remodelling the competition for capital: how domestic politics erases the race to the bottom. American Political Science Review, 98 (02), 261–276. doi: 10.1017/S0003055404001133

- Berenskoetter, F. (2016). Unpacking concepts. In F. Berenskoetter (Ed.), Concepts in world politics (pp. 1–19). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publishing.

- Black, S., & Munro, A. (2010). ‘Why issue bonds offshore? (BIS Working Paper No. 334). Bern: Bank for International Settlements, Retrieved from BIS website: https://www.bis.org/publ/work334.pdf.

- Blanco, L. R., & Rogers, C. L. (2014). ‘Are tax havens good neighbours? FDI spillovers and developing countries’. Journal of Development Studies, 50 (4), 530–540. doi: 10.1080/00220388.2013.874557

- Bonney, R. (1999). Introduction. In R. Bonney (Ed.), The rise of the fiscal state in Europe, c. 1200–1815 (pp. 1–17). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Buehn, A., & Schneider, F. (2016). Size and development of tax evasion in 38 OECD countries: what do we (not) know?. Journal of Economics and Political Economy, 3 (1), 1–11.

- Burn, G. (1999). The state, the city and the Euromarkets. Review of International Political Economy, 6 (2), 225–261. doi: 10.1080/096922999347290.

- Calomiris, C. W., & Haber, S. H. (2014). Fragile by design: The political origins of banking crises and scarce credit. The Princeton economic history of the Western World. Princeton, NJ; Oxford: Princeton University Press.

- Camp, R. A. (2015). Democratizing Mexican politics, 1982–2012. In W. H. Beezley (Ed.), Oxford research encyclopedia of Latin American history (Vol. 1). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Carmagnani, M. (1994). Estado y Mercado: La Economía Pública Del Liberalismo Mexicano, 1850–1911 (1st ed.). Sección de Obras de Historia. México, DF: El Colegio de México: Fondo de Cultura Económica. doi: 10.1086/ahr/101.3.947

- Centeno, M. A. (2002). Blood and debt: War and the nation-state in Latin America. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Cobham, A., & Janský, P. (2017). Global distribution of revenue loss from tax avoidance. Re-estimation and country results (WIDER Working Paper No. 15/2017). Helsinki, United Nations World University World Institute for Development Economics Research.

- Cohen, B. J. (2013). ‘Currency and State Power’. In M. Finnemore & J. Goldstein (Eds.), Back to Basics (pp. 159–176). Oxford: Oxford University Press. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199970087.003.0008.

- CONAIF. (2016). Reporte Nacional de Inclusión Financiera (Vol. 7). Mexico City, DF: Presidente de la Comisión Nacional Bancaria y de Valores. Retrieved from http://www.cnbv.gob.mx/Inclusi%C3%B3n/Documents/Reportes%20de%20IF/Reporte%20de%20Inclusion%20Financiera%207.pdf.

- Cota, I. (2015). Why Traders Love to Short the Mexican Peso. Bloomberg, 27 July, 2015.

- Crivelli, E., De Mooij, R., & Keen, M. (2015). Base erosion, profit shifting and developing countries (IMF Working Paper No. WP/15/118). Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund. doi: 10.5089/9781513563831.001

- Del Angel, G. A. (2016). Cashless payments and the persistence of cash: Open questions about Mexico (Economics Working Paper No. 16108). Stanford: Hoover Institution.

- Díaz-Infante, E. (2013). La Reforma Financiera y Los Riesgos Del Crédito. Mexico City, DF: Instituto Mexicano para la Competitividad. Retrieved from http://imco.org.mx/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/LaReformaFinancierayLosRiesgosdelCredito-3.pdf.

- FATF & GAFILAT. (2018). Anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing measures – Mexico. Fourth Round Mutual Evaluation Report. Paris, Financial Action Task Force on Money Laundering. Retrieved from http://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/reports/mer4/MER-Mexico-2018.pdf.

- Fichtner, J. (2015). The offshore-intensity ratio. Identifying the strongest magnets for foreign capital (CIYPERC Working Paper Series, Working Paper No. 2015/02). London, City University London. Retrieved from CIYPERC website: https://papers.ssrn.com/soL3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2928027.

- Findley, M. G., Nielson, D. L., & Sharman, J. C. (2014). Global shell games: Experiments in transnational relations, crime, and terrorism.. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Finnemore, M., & Goldstein, J. (2013). Puzzles about power. In M. Finnemore & J. Goldstein (Eds.), Back to basics (pp. 3–16). Oxford University Press. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199970087.003.0001.

- Flores, J. H. (2015). Capital markets and sovereign defaults: A historical perspective. (Paul Bairoch Institute of Economic History Working Paper No. 3/2015). Geneva, Université de Genève. Retrieved from Paul Bairoch Institute of Economic History website: https://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:73325.

- Garcia-Bernardo, J., Fichtner, J., Talks, F. W., & Heemskerk, E. M. (2017). Uncovering offshore financial centers: Conduits and sinks in the global corporate ownership network. Scientific Reports, 7. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-06322-9.

- Genschel, P. (2005). Globalization and the transformation of the tax state. European Review, 13 (5), 53–71. doi: 10.1017/S1062798705000190

- Genschel, P., Lierse, H., & Seelkopf, L. (2016). Dictators don’t compete: Autocracy, democracy, and tax competition. Review of International Political Economy, 23 (2), 290–315. doi: 10.1080/09692290.2016.1152995.

- Genschel, P., & Schwarz, P. (2011). Tax competition: A literature review’. Socio-Economic Review, 9(2), 339–370. doi: 10.1093/ser/mwr004

- Genschel, P., & Seelkopf, L. (2016). Winners and losers of tax competition. In P. Dietsch & T. Rixen (Eds.), Global tax governance. What is wrong with it and how to fix it (pp. 55–75). Colchester: ECPR Press.

- Gerring, J. (2009). Case selection for case‐study analysis: qualitative and quantitative techniques. In J. M. Box-Steffensmeier, H. E. Brady, & D. Collier (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of political methodology.. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Goldscheid, R., & Schumpeter, J. (1976). Die Finanzkrise Des Steuerstaats: Beiträge Zur Politischen Ökonomie Der Staatsfinanzen. In R. Hickel (Ed.), Edition Suhrkamp. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp.

- Gravelle, J. G. (2015). Tax Havens: International Tax Avoidance and Evasion. Washington, DC, Congressional Research Services. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/key_workplace/1378/.

- Haber, S., & Musacchio, A. (2013). These are the good old days: Foreign entry and the Mexican banking system. w18713. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.3386/w18713.

- Haber, S., Klein, H. S., Maurer, N., & Middlebrook, K. J. (2008). Mexico since 1980. The World since 1980. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Haber, S., Maurer, N., & Razo, A. (2003). When the law does not matter: The rise and decline of the Mexican oil industry. Journal of Economic History, 63 (01), 1–32. doi: 10.1017/S0022050703001712

- Haberly, D., & Wójcik, D. (2015a). Tax havens and the production of offshore FDI: An empirical analysis. Journal of Economic Geography, 15 (1), 75–101. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbu003.

- Haberly, D., & Wójcik, D. (2015b). Regional blocks and imperial legacies: Mapping the global offshore FDI network: Regional blocks and imperial legacies. Economic Geography, 91 (3), 251–280. doi: 10.1111/ecge.12078

- Hall, L. B. (1995). Oil, banks, and politics: The United States and Postrevolutionary Mexico, 1917–1924. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. doi: 10.1086/ahr/102.1.204-a

- Hall, P. A., & Taylor, R. C. R. (1996). Political Science and the Three New Institutionalisms. Political Studies, no. XLIV.

- Hamilton, N. (1982). The limits of state autonomy: Post-revolutionary Mexico. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. doi: 10.1086/ahr/88.3.780

- Harrington, B. (2016). Trusts and financialization. Socio-Economic Review, 15 (1), 31–63.

- Helleiner, E. (1994). States and the reemergence of global finance: From Bretton Woods to the 1990s. Ithaca/London: Cornell University Press.

- Hood, C. (2003). The tax state in the information age. In T. V. Paul, G. John Ikenberry, & J. A. Hall (Eds.), The nation-state in question (pp. 213–233). Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Pr‘Informal Employment in Mexico: Current Situation, Policies and Challenges’.

- ILO. (2014). Lima: International Labour Organization. Retrieved from http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—americas/—ro-lima/documents/publication/wcms_245889.pdf.

- IMF. (2014). Spillovers in international corporate taxation. Washington, D.C.: IMF

- Ingham, G. K. (2004). The nature of money. Cambridge, UK; Malden, MA: Polity.

- Johannesen, N., & Zucman, G. (2014). The end of bank secrecy? An evaluation of the G20 tax haven crackdown. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 6 (1), 65–91. doi: 10.1257/pol.6.1.65

- Kar, D., & Schjelderup, G. (2015). Financial flows and tax havens. Combining to limit the lives of billions of people. Washington, D.C.: Global Financial Integrity. Retrieved from http://www.gfintegrity.org/report/financial-flows-and-tax-havens-combining-to-limit-the-lives-of-billions-of-people/.

- Knight, A. (1990). Porfirians, liberals and peasants. 1. Paperback print. The Mexican Revolution (Vol. 1). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Knight, A. (2013). The Mexican state, Porfirian and revolutionary, 1876–1930. In M. A. Centeno & A. E. Ferraro (Eds.), State and nation making in Latin America and Spain. Republics of the possible. (pp. 116–138). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lane, P. R., & Milesi-Ferretti, G. M. (2007). The external wealth of nations mark II: Revised and extended estimates of foreign assets and liabilities, 1970–2004. Journal of International Economics, 73(2), 223–250. doi: 10.1016/j.jinteco.2007.02.003

- Levi, M. (1989). Of rule and revenue. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Linsi, L., & Mügge, D. (2017). Globalization and the growing defects of international economic statistics. (Fickle Formulas Working Paper No. 2–2017). Amsterdam, University of Amsterdam. Retrieved from Fickle Formulas website: https://www.fickleformulas.org/images/pdf/Working%20paper%202%20Linsi%20and%20M%C3%BCgge%202017.pdf.

- Macdonald, J. (2003). A free nation deep in debt: The financial roots of democracy. Princeton, NJ; Oxford: Princeton University Press.

- MacLeod, D. (2005). Downsizing the state: Privatization and the limits of neoliberal reform in Mexico. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- McCauley, R. N., McGuire, P., & Sushko, V. (2015). Global dollar credit. Economic Policy, 30 (82), 87–229.

- McCauley, R. N., Upper, C., & Villar, A. (2013). Emerging market debt securities issuance in offshore centres. BIS Quarterly Review, 2013 (3), 22–23.

- Mehrling, P. (2016). The economics of money and banking. New York City.

- Meltzer, A. H., & Richard, S. F. (1981). A rational theory of the size of government. Journal of Political Economy, 89 (5), 914–927. doi: 10.1086/261013

- Norfield, T. (2016). The city: London and the global power of finance. London; New York: Verso.

- OECD. (2015). Revenue statistics in Latin America and the Caribbean 1990–2013. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- OECD. (2017). ‘Revenue statistics 2017 – Mexico. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/tax/revenue-statistics-mexico.pdf.

- Palan, R. (1998). Trying to have your cake and eating it: How and why the state system has created offshore. International Studies Quarterly, 42 (4), 625–643. doi: 10.1111/0020-8833.00100

- Palan, R., Murphy, R., & Chavagneux, C. (2010). Tax havens: How globalization really works. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.