Abstract

Financial investment in the food and agriculture sector has grown in recent decades, including investment in equity-related funds that invest in or track the performance of a range of publicly traded transnational agrifood companies. At their height in recent years, equity-related investment funds accounted for around one third of financial investment in the sector. Despite their significance, investment in the agrifood sector via these types of investment funds has received much less academic and policy attention than other types of financial investment, such as farmland acquisition and commodity speculation. This paper examines the rise of equity-related investment in the agricultural sector and analyzes its implications for the food system. It provides an overview and analysis of the available data on these investment vehicles, including their holdings (i.e. the companies in which they invest) and ownership (i.e. the investors who own shares in those companies). This data shows a rise in common ownership of large agrifood firms by large asset management companies. The paper makes the case that this new pattern of investment in agrifood firms by large asset management firms has the potential to contribute to the already concentrated market power in the agrifood system.

Introduction

Financial investment in the agrifood sector has grown markedly since the 2007–2008 food crisis, which saw soaring food prices and concerns about possible future food shortages in a resource-constrained world. Much of this investment has been associated with large-scale institutional investors – such as pension funds, hedge funds, asset management firms, and university and foundation endowment funds – that normally invest considerable sums of money with passive, long-term investment strategies. A sizeable proportion of these investments has been channelled through new financial investment vehicles tied to the sector, such as commodity index funds (CIFs; e.g. Ghosh, Citation2010) and real estate investment trusts (REITs) that include farmland located around the world (e.g., Fairbairn, Citation2014). The side-effects of these new types of investment in the agrifood sector, ranging from heightened food price volatility to fragile land rights for farmers, have received attention from global bodies such as the Food and Agriculture Organization, the World Bank, and the G20, to determine appropriate international governance responses (Clapp & Isakson, Citation2018).

While financial investment in commodities and farmland has attracted a great deal of attention, recent years have also seen financial investors pour money into equity-related funds linked to the food and agriculture sector. Equity-related investment funds include both mutual funds and exchange traded funds (ETFs) that invest in company shares or track the performance of a range of transnational agrifood firms that are publicly traded on the stock exchange.1 According to at least one estimate, at their height in the 2010–2014 period, equity-related investment funds accounted for about a third of global financial investment in the agrifood sector (Valoral Advisors, Citation2010, Citation2015). Although in more recent years investors have vastly increased investment in private equity (i.e. investment in private firms that are not publicly traded; Burch & Lawrence Citation2013; Valoral Advisors Citation2018a), equity-related funds based on publicly traded firms remain an important investment vehicle for investors interested in gaining exposure to the food and agriculture sector. Despite their significance over the past decade or more, however, the scholarly and policy communities have paid far less attention to investment in equity-related financial investment than they have to commodity and land speculation. Yet it is far from clear that the effects of equity-related investments are entirely neutral.

This paper examines the rise of equity-related investment funds associated with publicly listed food and agriculture firms and assesses its implications for the sector. Data on these funds was obtained through a systematic review of the websites of the largest asset management companies that offer equity-related investment products to investors as well as the Thomson Reuters Eikon database, which provides ownership data for publicly listed companies. The analysis suggests that the rise in equity-related funds based on shares in agrifood firms is associated with concentrated power in the global food system, which in turn can have wide-ranging economic, social, and ecological consequences. This argument is based on three key findings that arise from the data.

First, a small number of large asset management companies act as intermediaries that funnel vast sums of money into equity shares in publicly listed transnational agribusiness firms through a variety of investment funds that enable investors to gain exposure to the sector. Second, company ownership data reveals that those same giant asset management companies are among the largest shareholders of the dominant agribusiness firms. This ownership pattern, where the largest firms across a single sector share the same owners, is referred to in the economics and finance literature as ‘common ownership.’2 Patterns of common ownership are on the rise more generally in many sectors, and a growing number of analysts have pointed to the ways in which it can encourage anti-competitive behavior and increase corporate power (Azar, Schmalz, & Tecu Citation2018; Schmalz, Citation2018; Elhauge, Citation2016). Third, in the agrifood sector, concentration and market power is already pronounced, which raises important questions about the potential effects of the increasingly prominent pattern of common ownership by large asset management firms across the leading firms in the sector. However, unlike the cases of financial investment in commodities and farmland, there has been very little attention paid to potential problems arising from new patterns of equity investments in the agrifood sector by global governance institutions.

The first section of the paper examines the place of equity-related funds in a financialized global food system. The second section provides an overview of the available data on the shape and form of equity-related funds with links to publicly listed agrifood firms. The third section provides an analysis of the potential implications of the common ownership patterns that arise from the growth of agrifood equity-related fund investment and raises questions for future research. The paper concludes with a brief discussion of broader implications for policy and governance.

Situating equity-related investment in the financialization of food and agriculture

Scholars have paid increasing attention to the process of financialization and its political and economic effects across a range of sectors, including food and agriculture, in recent decades (for a review, see Burch & Lawrence, Citation2013; Epstein, Citation2005; Krippner, Citation2011; Schmidt, Citation2016; van der Zwan, Citation2014). The growing role of financial markets and actors in the economy has opened new arenas for financial investment and profit-making through the creation of novel financial investment vehicles that have attracted enormous sums of capital (Krippner, Citation2011). Financialization has also permeated everyday practices to the extent that states have downloaded the responsibility for managing risk onto individuals who in turn are encouraged by financial actors to utilize new financial products as a way to enhance their own security (Aitken, Citation2007; Isakson, Citation2015; Martin, Citation2002). The greater presence of financial incentives in the economy has also resulted in a shift toward prioritizing the returns to shareholders in businesses over other values in the economy. As a result, firms are increasingly making decisions that maximize benefits for those investors that hold their shares on the stock market (Froud, Haslam, Johal, & Williams, Citation2000; Froud, Johal, Leaver, & Williams, Citation2006).

Literature on the financialization of food has outlined the ways in which large-scale institutional investors have been attracted to the sector (Clapp & Isakson, Citation2018). Many of the investors in the sector, especially those with long-term outlooks, such as pension funds and endowment funds, are interested in passive investment strategies. As such, they typically seek to acquire low maintenance assets with the intention of holding them for a long period of time. These investors have been encouraged by an increasingly prominent narrative that a growing population is placing ever greater demands on the world’s natural resource base and that food production will need to increase by 50% or more in the coming decades (e.g. FAO, 2017). The prospect of the intensification of these dynamics has led many investors to conclude that food and agriculture investments will deliver positive returns well into the future. In the run-up to and immediate aftermath of the 2007–2008 food crisis, a number of financial institutions, including asset management firms, introduced new investment vehicles to facilitate institutional investment in the sector. Most scholars working on this topic have focused on the rise and intensification of two new types of financial investment vehicles in the sector where the broader socio-economic and environmental impacts have been somewhat clear and where there have been active debates about improving governance: agricultural commodities and farmland investments.

CIFs track the value of a bundle of commodities, including agricultural commodities, and allow investors to buy into the market without having to purchase physical commodities or even commodity futures contracts (Baines, Citation2017; Ghosh, Citation2010; Russi, Citation2013). Investment in these types of commodity index investment products increased sharply after 2000. Speculative investment in agricultural commodities rose by a factor of two between 2006 and 2011, from US$65 billion to US$126 billion, as investors sought to capitalize on rising commodity prices (Worthy, Citation2011). This type of financial speculation has been associated with higher and more volatile food prices, which compromises ability of poor people to access food (De Schutter, Citation2010; Ghosh, Citation2010; Worthy, Citation2011). It has also been associated with ecological damage from a rush to increase large-scale food production in a higher food price environment (Clapp, Citation2015). Concern about the potential negative impact of financial speculation on food prices has led to growing calls from a number of international food advocacy organizations, including Friends of the Earth and Oxfam, for curbs on this type of investment. Measures such as limits on the number of speculative positions any one investor can hold, although only partial in their implementation, have been included in financial sector reforms in both the US and the EU in recent years (Helleiner, Citation2018).

The emergence of real estate investment trusts and other farmland linked investment funds have also attracted large institutional investors (Desmarais, Qualman, Magnan, & Wiebe, Citation2017; Fairbairn, Citation2014; Magnan, Citation2015). Following the 2008 food crisis, investment in agricultural real estate boomed in response to increased demand by financial investors seeking to gain from exposure to farmland as an asset class in a context of rising food prices. Investors had poured some US$10 to 25 billion into farmland investments by 2010, and by 2012 this amount increased to US$30 to 40 billion (HighQuest Partners, US, Citation2010; Wheaton & Kiernan, Citation2012). Critics see this investment as a form of ‘land grabbing’, and numerous case studies have documented the impact of international land deals on land tenure rights in countries affected by such investments (e.g. Cotula, Citation2013; Desmarais et al., Citation2017; Larder, Sippel, & Argent, Citation2018; White, Borras, Hall, Scoones, & Wolford, Citation2012). Much of the investment in farmland in the past decade has been focused on large-scale industrial agricultural production, particularly for biofuels (Neville, Citation2015). The impact of speculative financial investment in farmland has led to calls from civil society and many governments for international governance initiatives to protect land tenure rights and ensure responsible land investment, including the UN Voluntary Guidelines on land tenure (Margulis & Porter, Citation2013; McKeon, Citation2013).

As institutional investors increased their interest in the agrifood sector as an investment arena, financial institutions also began to offer equity-related investment funds alongside CIFs and farmland investment funds. But while the volume of investment in these equity-related investment funds was comparable to that of commodities and farmland investments, scholars and policymakers have not given this trend the full attention it deserves. This neglect may be due to several factors. First, this type of investment is more difficult to identify as a trend because it is deeply entwined within broader investment patterns in which food and agriculture equity investments are only a part. Some specific agriculture-focused equity-related funds have emerged in recent years, but as outlined below, these capture only some of the investment in food and agriculture-related firms. Second, the impact of equity-related fund investments can be more difficult to link definitively to specific and measurable outcomes on the ground because the effects of the financial investment are mediated through asset management firms as well as corporate practices and behaviors. In other words, the causes and effects are ‘distanced’ from one another, making political mobilization around the issue challenging (Clapp, Citation2014, Citation2015; Princen, Citation2002). This type of financial investment is important to examine, however, because it highlights the changes in the food system that result from the prioritization of shareholder value, an aspect of financialization that the agrifood literature has not yet examined in much detail.

Equity-related funds are investment products sold by large asset management firms that cater to the same kinds of large-scale institutional investors drawn to commodities and land investments. Like new investment products such as CIFs and REITs noted above, equity-related funds give investors broad exposure to publicly listed firms in the food and agriculture sector without requiring those investors to own company shares directly. Rather, investors buy into a fund that pays out dividends based on the financial performance of a group of publicly traded firms. It is the asset management firms that actually own the company shares and act as mediators between the agrifood firms and the financial investors. The asset management firms sell both over-the-counter (OTC) fund products (e.g. agriculture-focused mutual funds that may be either actively or passively managed) and ETFs specifically tied to the sector. Similar to CIFs, OTC equity funds (such as mutual funds) are sold directly to investors off exchange, while ETFs are traded on the stock exchange.

The number of equity-related investment funds associated with the food and agriculture sector, and the amount invested in them, increased dramatically in recent years, especially since 2005 when agricultural commodity prices began to tick upwards and interest in the agrifood sector began to grow among financial investors. The investment advising company Valoral Advisors, for example, which tracks investment funds that specialize in food and agriculture, noted that the total number of funds that it actively follows increased from 38 in 2005 to 530 in 2018. As of September 2018, these 530 funds managed US$83 billion in assets, up from the US$18 billion reported in 2010 (Valoral Advisors, Citation2010, Citation2018a, Citation2018b). Valoral estimates that in the 2014–2017 period, on average around 40 ETFs and mutual funds focused specifically on investments in publicly listed equities in the agriculture sector, with a total of US$4.6–13.6 billion invested (Valoral Advisors Citation2015, Citation2018a). These amounts do not include the many non-agriculture specific funds, such as mutual funds and ETFs that focus on consumer staples and general economy wide investing, which also include shares in agrifood firms (as outlined in more detail below). It is difficult to determine with certainty the total amount of money invested in publicly-listed agrifood equities because they are spread across many types of investment funds. However, based on the Valoral Advisors studies, as well as the analysis below, it is possible to estimate that at least US$10 billion, and likely much more, is invested in agrifood globally, and this number has climbed significantly in recent decades.

The rise of equity-related funds linked to agrifood firms

The rise of equity-related investment vehicles occurred as part of a broader wave of investment in listed equities via mutual funds and ETFs in the global economy. Together, mutual funds and ETFs account for around US$35 trillion of an estimated US$70–85 trillion in assets under management globally (Kelly, Citation2017). These equity-related investment funds typically payout a dividends (paid by the asset management company to the investor) – that are based on the performance of shares in firms across a sector that are bundled into an index or a portfolio picked by an asset manager – in return for a payment for a share in the investment product, plus a fee (paid by the investor to the asset management company). The idea for the investor of owning a portfolio product is to minimize risk and gain exposure across a sector or the economy as a whole, and to reduce the need to actively watch markets and buy and sell shares of individual firms according to short term changes in firm performance and practices. The decisions regarding which firms to include in an index are handled either by an active asset manager, or are linked to a pre-established index which effectively makes the decision of which firms to include in the benchmark. These kinds of investments are popular with passive investors because they are easy to hold over long periods of time and do not require their close attention to market conditions.

Modern mutual funds have been around since the 1920s. Mutual funds pool money from a group of investors who entrust their investments to a professional asset manager (portfolio manager) who picks investments in stocks to meet the goals established for the fund for things like risk level and return expectations. There are a number of mutual funds that are stylized to different needs. Mutual fund investors own shares in that fund, but not the actual stocks (and hence they do not have the voting rights that direct shareholders have). When mutual funds earn dividends from the firms in which they invest, they distribute payments to fund investors. Indexed mutual funds came along in the 1970s, enabling asset management firms to offer products with lower fees because they did not require active management. Mutual funds in general gained in popularity in the 1990s, and today they make up an important component of pension fund investments as well as individual investments, particularly those geared toward retirement savings. More than 10,000 mutual funds currently exist in the US alone. Around US$30 trillion in assets is locked up in mutual funds globally (with about US$16 trillion invested in mutual funds in the US alone) (Valdez & Molyneux, Citation2015, p. 216). Of the global investment in mutual funds, around US $5 trillion is invested in indexed products (Wigglesworth, Citation2018a).

Like index-based mutual funds, ETFs replicate an index or underlying benchmark of a group of firms. But unlike mutual funds that are typically sold directly, or OTC, ETFs are traded like a stock on the stock exchange. ETFs have become wildly popular with institutional investors, because the fees involved are very low compared to actively managed mutual funds, often just a fraction of a percentage point. Over the past few years, investment in these funds has surged, breaking records in terms of funds flowing into them on an annual basis, which according to the Financial Times has sent ‘shockwaves across the entire asset management industry’ (Flood, Citation2018). The amount invested in ETFs in total hovered around US$5 trillion throughout 2018 (Flood, Citation2018; Wigglesworth, Citation2018a) and, according to BlackRock, is forecast to rise to around US $12 trillion by 2023 (Thompson, Citation2018a). Not unlike commodity and land investments, the rise of these funds has stirred some controversy in financial circles, with questions swirling regarding their impact on market efficiency and their propensity to contribute to financial bubbles. Some analysts have decried the impact of passive investment in ETFs as being ‘“worse than Marxism” given that communists at least tried to allocate capital efficiently,’ while others defend them as better and cheaper products, that is ‘the very essence of capitalism’ (Wigglesworth, Citation2018b).

Globally, there are now around 5000 ETFs available on the market which offer a range of products tailored to different investor interests (ETFGI, Citation2018). Some ETF products focus on a specific sector, such as investment in technology firms, or energy firms, or real estate. Others focus on specific countries or regions of the world, such as emerging economies. Yet others focus on boutique issues. For example, there is an obesity ETF, with the ticker name SLIM (offered by Janus Henderson), that invests in firms set to profit from the fight against obesity, including Weight Watchers, diet supplement firms, and plus-sized clothing companies. A gender diversity ETF, with the ticker name SHE, is offered by State Street and invests in firms that demonstrate higher levels of gender diversity in senior leadership compared to other firms in their sector (with the food companies Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, and McDonald’s in its top ten holdings). An Alternative Harvest fund with the ticker name MJ is offered by ETF Manager’s Group, which invests in stocks related to cannibis. Most ETFs track indices of firms, but there are also a number of funds that track indices of commodities, bonds, and currencies.

Large asset management firms are the biggest brokers of both mutual funds and ETFs. Collectively, institutional investors, which include the large asset management firms, hold around 70%–80% of the shares US firms that are publicly traded on the stock market (Azar et al., Citation2018, p. 1514). The largest of these asset management firms are Blackrock, Vanguard, State Street, Fidelity, and Capital Group, although there are other, smaller asset management companies that specialize in certain sectors and can be big players in those markets. Over the past decade, asset management firms have begun to offer new investment products linked to the agrifood sector, primarily in the form of ETFs and mutual funds, either focused specifically on the sector or as broader funds that include significant shares of agrifood firms in their holdings. More established mutual funds, particularly those focused on consumer staples, for example, have maintained significant holdings in agrifood firms.

There is no central database listing investment funds linked to food and agriculture firms, but the information is largely accessible in fund fact sheets that are posted on the websites of the asset management firms that offer such funds to investors. These fact sheets typically report the value of the fund, the top firms in which it invests (its holdings), and the distribution of its holdings by industry and sector. The asset management firm websites also typically post data indicating current assets under management as well as a listing of all of the holdings for each fund. Listings of top agrifood equity-related funds are also listed in on some general investment websites. A systematic review of the available data revealed a number of investment fund products that come in varying sizes and with different specific foci. These funds were closely examined and narrowed down based on size and focus of the funds. Examples of some of the most prominent funds operating in the agrifood sector are outlined in more detail below and summarized in .

Table 1. Examples of investment funds with significant holdings in agrifood linked firms.

BlackRock is the world’s largest asset management firm, with around US$6.4 trillion assets under management and offices located around the world. The firm markets hundreds of investment funds. One of the larger of its funds, the iShares Core S&P 500 Index ETF, which tracks the firms in the Standard and Poor’s (S&P) 500 Index, has some US$150 billion in assets under management (BlackRock, Citation2018d). Most of the top publicly traded food and agriculture firms are part of the S&P 500 index, and although they are not in its top 10 holdings, the sheer size of the fund means that it still holds significant shares in those firms. Other BlackRock funds are more specifically focused on food and agriculture. Blackrock’s Global Consumer Staples ETF, which was launched in 2006 and has US$560 million in assets under management, holds shares in a number of the world’s largest food companies, with agrifood stocks making up around 75% of the fund. Nestlé is the funds’s largest holding, and other agrifood firms that make up the fund include Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, Walmart, Anheuser Busch InBev, Mondelez, Danone, and Kraft Heinz (BlackRock, Citation2018e).

BlackRock also markets more specialized funds targeted at different aspects of the agrifood sector. For example, BlackRock’s COW Global Agriculture ETF, launched in 2007, tracks the Manulife Asset Management Global Agriculture Index. The fund has US$231 million in assets currently under management, and focuses on firms that provide inputs (seeds, chemicals, and fertilizers), farm equipment, and agricultural trading companies. Among its top holdings are farm equipment firm Deere & Co; agricultural trading and processing firms Bunge, and ADM; and packaged meat company Tyson (BlackRock, Citation2018a). BlackRock’s World Agriculture Fund (a mutual fund), set up in 2010, has US$65 million in assets invested in a mix of agricultural firms including, ADM, Bunge, Tyson; as well as farm equipment firms Deere & Co and Kubota; and fertilizer firms Nutrien and Yara (BlackRock, Citation2018c). BlackRock also markets SPAG, an Agribusiness ETF with US$82 million in assets that was launched in 2011. This fund tracks the S&P Commodity Producers Agribusiness Index, which includes Deere & Co, Nutrien, Kubota, ADM, Tyson, and Associated British Foods PLC (BlackRock, Citation2018d). More recently, BlackRock introduced a smaller, specialty Global Agricultural Producers ETF in 2012, called VEGI, which currently manages US$34 million in assets (BlackRock, Citation2018b). VEGI tracks an index of agricultural firms, and its top holdings include Deere & Co, Nutrien, ADM, Kubota, and Bunge, among others.

Vanguard is the second largest asset management firm with US$5.2 trillion in assets under management. Vanguard is known for ‘inventing’ index funds in the 1970s. Like BlackRock, Vanguard markets a variety of investment funds. Its Consumer Staples Fund, available as both an ETF and as a Mutual Fund, for example, has approximately US$5 billion in assets under management (Vanguard, Citation2018). The top stocks in the Vanguard Consumer Staples Index (the index that is used for both funds) include soft drink firms Coca-Cola, PepsiCo; retailers Wal-Mart, Costco, and Kroger; packaged food firms Mondelez, Kraft Heinz, General Mills, Tyson, Kellogg, and Bunge; among others. Food, beverage, and agriculture related equities make up close to 75% of the Vanguard Consumer Staples funds, which includes soft drinks (20% of the index), packaged foods and meats (17%), and tobacco (12%; Vanguard, Citation2018).

State Street is the third largest asset management firm, with approximately US$2.8 trillion in assets under its management. State Street markets both mutual funds and ETFs to investors. Among the top ten holdings of State Street’s Consumer Staples Mutual Fund, with US$10 billion in assets under management, are Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, Wal-Mart, and Mondelez. The fund also holds shares in Kraft Heinz, General Mills, ADM, Monster Beverage, Tyson, Kroger, Kellogg, Molson, Conagra, JM Smucker, Hershey, Hormel Foods, and the Campbell Soup Company (State Street Global Advisors, Citation2018).

Fidelity is also a large asset management firm, with US$2.5 trillion in assets. While it does not have specific food and agriculture focused investment funds, around 70% of Fidelity’s US$1.5 billion Select Consumer Staples Portfolio mutual fund is comprised of food related equities, including soft drink firms Coca Cola, PepsiCo, and Monster Beverages; as well as the confectionary firm Mondelez (Fidelity, 2018a). Fidelity also markets a US$539 million Consumer Staples Index ETF, launched in 2013, that tracks the MSCI USA IMI Consumer Staples Index, 75% of which is food related, with Coca Cola, PepsiCo, and Mondelez in its top holdings (Fidelity, 2018b).

Capital Group, which manages US$1.9 trillion in assets, focuses its investment products in actively managed mutual funds, although it has recently begun to venture into indexed ETF products as well. Although Capital Group does not have a specific food and agriculture related fund, shares in food and agriculture firms are liberally sprinkled across its various mutual funds. One of its larger mutual funds, the American Mutual Fund with a whopping US$50 billion in assets under management, has holdings in processed food and beverage companies Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, Kellogg, Kraft Heinz, Mondelez, and General Mills; fast food and retail outlets McDonald’s, Starbucks, and Kroger; as well as agricultural input firms DowDupont and Nutrien; among others (Capital Group, Citation2018). Although only 10% of the American Mutual Fund is made up of food and agriculture linked firms, the sheer size of the fund means that its agrifood holdings are nonetheless significant.

Alongside these big players in the asset management business are several food and agriculture specific investment funds offered by smaller asset management firms. One of the bigger equity index funds that offers broad exposure to food and agriculture is VanEck Vectors Agribusiness ETF, which has the ticker name MOO. Launched in 2007, MOO currently has approximately US$850 million in assets under management. MOO tracks shares of firms specializing in agricultural production, inputs and trade, including farm equipment firms Deere & Co, Toro, and Kubota; fertilizer firms Nutrien, Mosasic, and Yara; and agricultural commodity traders such as ADM, Bunge, and Wilmar. It also tracks some food processing companies and animal health companies (VanEck, Citation2018).

Financial investors have also begun to gain exposure to shares of firms in the food processing sector via the Invesco Powershares Dynamic Food and Beverage Portfolio ETF, which has a ticker name of PBJ. Set up in 2005, PBJ tracks the Dynamic Food and Beverage Intellidex Index and currently manages around US$88 million in assets. PBJ’s top holdings include fast food companies Yum! Brands (Kentucky Fried Chicken, Pizza Hut, and Taco Bell), Starbucks, and Wendy’s; as well as processed food firms, Mondelez, Coca-Cola, Keurig Dr. Pepper, and Post Holdings; and food trade, service, and retail firms ADM, Sysco, and Kroger (Invesco, Citation2018). Additional funds in the food and agriculture investment space include a Fertilizers/Potash ETF marketed by Global X that goes by the ticker name SOIL, which was launched in 2011 and currently manages US$13 million in assets. Among SOIL’s top holdings are the fertilizer firms Yara, Agrium, Mosaic, and K + S, among others (Global X, 2018).

New patterns of common ownership in large agrifood firms

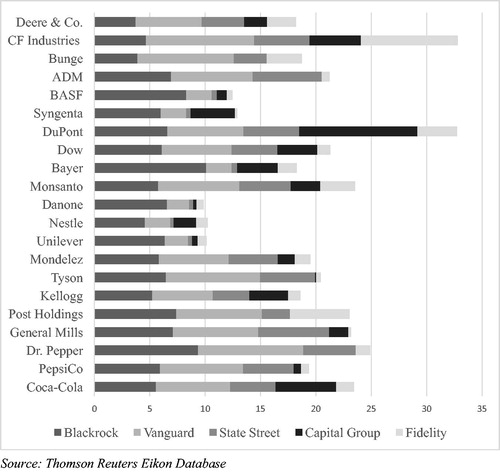

As asset management companies have moved into investments in the food and agriculture sector with new investment funds associated with the sector, as outlined above, they have become important shareholders in a number of transnational agrifood firms from input suppliers, to equipment, to grain trading, to processing companies. A number of firms that have long been competitors with one another now increasingly share the same owners: the large asset management companies. Collectively, the asset management giants – BlackRock, Vanguard, State Street, Fidelity, and Capital Group – own significant proportions of the firms that dominate at various points along agrifood supply chains. When considered together, these five asset management firms own around 10%–30% of the shares of the top firms within the agrifood sector, as shown in . The firms with the highest degree of ownership by the large asset management firms are those firms that dominate in highly concentrated market segments, including agricultural inputs, commodity trading, and processed and packaged foods.

Figure 1. Percent ownership shares of major agrifood companies held by major asset management companies, as of December 31, 2016.

Situations where an investor holds minority shares in multiple competing firms in the same market segment is referred to as ‘common ownership’ (OECD, Citation2017, p. 9), also sometimes called ‘horizontal shareholding’ (Elhauge Citation2016). This pattern of common ownership in key areas of the agrifood sector is not dissimilar to patterns across the economy as a whole, where the three largest asset management firms (BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street), when considered collectively, constitute the largest shareholder in 88% of the S&P 500 firms (Fichtner, Heemskerk, & Garcia-Bernardo, Citation2017, p. 298). As the OECD notes, by 2015 ‘the mean ownership of 1,662 listed U.S. corporations by the Big Three (BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street) was over 17.6%’ (OECD, Citation2017, p. 11).

The high degree of common ownership among the top firms in the global economy today is stark, but not unprecedented. Such levels of concentrated ownership are not dissimilar to the early 20th century when businessmen J.P. Morgan and J.D. Rockefeller owned significant shares across a range of large firms (Fichtner et al., Citation2017; Krouse, Benoit, & McGinty, Citation2016). Some analysts refer to the growing domination of a few firms that own large portions of companies via mutual funds and ETFs as a ‘new finance capitalism’ (Davis, Citation2008). As a recent OECD report notes, ‘…corporate ownership had become overwhelmingly intermediated by institutions rather than held directly by individuals…’ (OECD, Citation2017, p. 11). Fichtner et al. (Citation2017, p. 301) refer to this phenomenon as ‘asset management capitalism.’

The trend of institutional ownership has become more pronounced in the past 10–15 years, in particular with the rise of passive investment strategies and the popularity of index-based investment funds. Since the 2008 financial crisis, investment in index-based mutual funds and ETFs together has risen by a factor of five, from US $2 to US$10 trillion (Wigglesworth, Citation2018a). The percentage of US publicly traded firms that are held by the same institutional investors that hold at least 5% of the shares in other firms in the same sector has increased from under 10% in 1980 to around 60% in 2014 (OECD, Citation2017, p. 13; He & Huang, Citation2017). Vanguard, for example, one of the largest providers of ETFs, owned 5% or more of just three S&P 500 companies in 2005, but by mid-2016 that number had climbed to 468, or 94% of the firms in the S&P 500 index (Krouse et al., Citation2016). Vanguard remains one of the fastest growing asset management firms, pulling in US$1 billion per day in new investments in 2017 (Walker, Citation2018). Similar patterns of growth in institutional investment in the S&P 500 have also occurred with the other large institutional investment houses that manage a growing share of global assets. BlackRock, for example, took in US$28 billion in investments into its ETFs in January 2018 alone (Flood, Citation2018).

There is an emerging literature that explores the implications of common share ownership among large asset management firms across a range of sectors in the economy more broadly. A number of studies have pointed to a potential weakening of competition that can translate into higher prices and more market power for firms (e.g. Azar et al., Citation2018; Elhauge, Citation2016; Fichtner et al., Citation2017; OECD, Citation2017). Anti-competitive practices can arise in situations of common ownership because there is little incentive for the largest shareholders of firms – a concentrated group of large asset management companies – to push management to increase their individual market share via price competition or innovation. Rather, the common owners have an incentive to encourage firms to undertake strategies that assist the sector as a whole. The growth of ETFs and passive investment strategies in particular has given rise to this concern, as the large asset management companies cannot sell stock in firms they believe are performing poorly, because they are obliged to invest in those firms that appear in independently set indices, which typically include a range of firms within the same sector. For this reason, they have little incentive to work with individual firms to encourage competition. Even for actively managed funds, divestment from a particular stock is not a decision that is taken lightly by asset management companies (Thompson, Citation2018b). Further, if the actively managed fund is also invested across a number of firms in the same sector, its manager similarly has an incentive to encourage performance across the sector, rather than focusing on achieving greater profitability at individual firms.

A variety of anti-competitive effects can arise when firms and their owners prioritize sector wide benefits over individual firm performance (Schmalz, Citation2018). Firms may collude with one another, either explicitly or implicitly, to raise prices, and hence profits, across the sector, without any associated increase in quality or service. The risk of this type of behavior is especially likely in markets that are already oligopolistic in nature (OECD, Citation2017, p. 20). In the airline industry, for example, Azar et al. (Citation2018) found that common ownership among the top airline firms is associated with prices that are 3%–7% higher than they would have been with a more diffuse ownership pattern. Similar outcomes have been documented with respect to higher fees being charged among commonly owned banks (Azar, Raina, & Schmalz, Citation2016). Common ownership can also encourage firms to engage in mergers and acquisitions (M&As) as firms seek to expand their market share not by competing with each other, but by expanding their size within the marketplace. Brooks, Chen, and Zeng (Citation2018) found that there is more likely to be a merger event between firms when they share institutional owners, which can effectively reduce the number of competitors within a sector and increase the market share of each of the firms that remain. Commonly owned firms can also effectively work to discourage new entrants into the market. In the pharmaceutical sector, Newham, Seldeslacts, and Banal-Estañol (Citation2018) found that common ownership is associated with higher barriers to entry within that sector, with higher levels of common ownership resulting in a lower probability of generic drug firms entering the market.

There are several mechanisms by which common ownership can encourage these kinds of anti-competitive outcomes. Shareholders can make their preferences known to firms’ management via direct engagement, threats to sell stock (in the case of actively managed funds), and voting on the board regarding management decisions, including executive pay incentives (Azar et al., Citation2018; OECD, Citation2017). Fichtner et al. (Citation2017, pp. 318–319), for example, found that the three largest asset management firms – BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street – tended vote in unison and typically with, rather than against, management (Fichtner et al., Citation2017). At the same time, managers of firms are typically acutely aware of the identity of their largest shareholders, and may independently act in ways that prioritize sector performance over individual firm performance in order to satisfy those shareholders. As Azar et al. (Citation2018, p. 1518) note, this effect occurs whether or not the asset management firms communicate directly with the management of the firms in which they own shares.

As a result of these dynamics, markets where common ownership characterizes shareholding tend toward greater concentration and market power for both asset management firms as well as the firms they own. In other words, the potential for commonly-owned firms to raise prices, to engage in mergers and acquisitions, and to work together to discourage new entrants from the market, enables those firms to expand their market share and dominance while benefiting their asset management firm owners handsomely. Fichtner et al. (Citation2017) refers to this phenomenon as ‘hidden’ structural power for the asset management firms and the companies they own. Azar et al. (Citation2018) suggest that the anti-competitive effects of common ownership can result in effective levels of concentration that are far beyond what traditional measures of market concentration would indicate, and enables firms to exercise market power at levels above what current anti-trust regulations allow. They note that this effect in the airline industry is 10 times the level of market concentration that US regulatory authorities would permit (Azar et al., Citation2018, p. 1517).

Greater market power of dominant firms, in turn, can lead to broader societal effects that arise from these dynamics, which must also be considered. Three broader effects in particular have garnered attention in recent years. First, according to Elhauge (Citation2016), the power to raise prices that can arise from common ownership can contribute to inequality in the broader economy because it concentrates wealth and income into very few hands – that is, the large asset management companies, and the massive firms in which they invest. Pricing power that arises from concentration enables a perpetuation of high profits for a few firms, but contributes little to economic growth across the economy, because profits are built on market power rather than via competition. Low growth, in turn, can contribute to weak job creation and stagnant wages, which further exacerbates inequality in the broader economy (Khan & Vaheesan, Citation2017, p. 238; Elhauge, Citation2016). A recent IMF study on the rise of corporate giants, for example, finds that the ability of dominant firms to increase prices ultimately results in a lower share of income for workers (Diez, Leigh, & Tambunlertchai, Citation2018, p. 16).

Second, market power that can arise from common ownership can also contribute to a lag in innovation in large companies. Schmalz (Citation2015) notes that commonly owned firms may forego aggressive research and development spending because doing so could harm the profitability of other firms in the sector, thus acting as a drag on the returns to investment across the sector. The IMF study noted above also suggests that the market power of corporate giants, especially those firms that operate in highly concentrated markets, can lead to weaker investment and innovation (Diez et al., Citation2018, pp. 12–14). The authors found that while higher price markups can initially increase investment and innovation, the relationship can turn strongly negative in industries that have higher levels of concentration.

Third, the political power of firms can also be enhanced in cases where common ownership results in fewer firms within a sector due to mergers and acquisitions and elevated barriers to entry. When fewer, larger firms dominate in a sector, those firms are more likely to secure more air time with government policymakers in their attempts to influence policy outcomes. As Khan and Vaheesan (Citation2017, p. 266) note, it is easier for fewer, larger firms to organize around common policy interests. These firms are able to influence policy and governance via a number of mechanisms, including lobbying policymakers directly, structural influence over policymaking owing to their significance in the economy, and through the ability to shape discourse (Fuchs, Citation2007; Ruggie, Citation2018). Large firms are more likely to engage in lobbying (Khan & Vaheesan, Citation2017, p. 266) and over the 1997–2012 period, corporate lobbying increased markedly (The Economist, Citation2016). In the US, lobbyists spend around US$2.6 billion per year making their voices heard by policymakers in Washington, DC, which amounts to 30 times the amount spent by labor unions and public interest groups combined (Drutman, Citation2015). Structural power has also been enhanced in recent decades. As Ruggie (Citation2018) notes, firms are able to exercise this type of influence through their ability to sue governments and to take advantage of tax havens and transfer pricing practices if they are not satisfied with government policies. Firms can also shape ideas that inform policy through discursive information and advertising campaigns (Fuchs, Citation2007), which tend to be more influential when there are fewer firms in the marketplace competing to deliver their message.

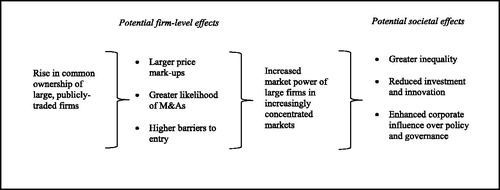

The possible effects of common ownership, both with respect to anti-competitive corporate behaviors at the firm level as well as the potential wider effects on society that result from concentrated market power, are summarized in . The studies noted above have begun to analyze the effect of common ownership on corporate practices with detailed empirical studies based on econometric methods that test the extent to which the available data on the change in common ownership over time correlates with those practices. Such data is not always easily available and there is an emerging debate regarding the most appropriate methods for analysing that data (e.g. Azar et al., Citation2018; Elhauge Citation2018; O’Brien & Waehrer, Citation2017; OECD, Citation2017). More research is needed to widen the analysis of the effects of common ownership to other sectors and other possible effects.

The examination of the wider societal effects of common ownership is also challenging, given that there are often multiple causes for the broader observable phenomena, such as inequality, weak investment and innovation, and enhanced corporate power, and because the effects are mediated through corporate practices. The cause and effects are, in other words, distanced from one another (Clapp, Citation2015; Princen, Citation2002). For this reason, it is important to map out the potential causal pathways as a first step to understanding how the rise of new forms of investment funds, and in turn the rise of common ownership by large asset management firms, matters for society.

Potential implications of new investment patterns in the agrifood sector

In what ways is the agrifood sector likely to be affected by the recent increase in mutual funds and ETFs with investments in the sector and the new patterns of common ownership that accompany those new investments? The literature on common ownership outlined above suggests that anti-competitive behaviors, as well as broader societal effects, may arise when large firms in the same sector share the same owners. Corporate concentration, which itself is associated with some anti-competitive tendencies, has already been well documented across the entire agrifood sector – from inputs to agricultural commodity trading, to food processing, to food retail – and the firms that dominate at each point are able to exercise extraordinary power (Howard, Citation2016; IPES Food, 2017). When common ownership of these firms is added to the existing analysis of corporate power and concentration, a number of important questions and areas for further inquiry emerge. In particular, there is a real possibility that the levels of corporate power and influence in the sector are much higher than previously understood as a result of rising levels of common ownership among agrifood firms. Below, I offer a preliminary analysis of how the firm-level and broader societal dynamics associated with common ownership more generally have the potential to play out in the agricultural inputs sector and point to areas where further research is required to test the extent to which common ownership in fact plays a role in shaping outcomes in the broader food system.

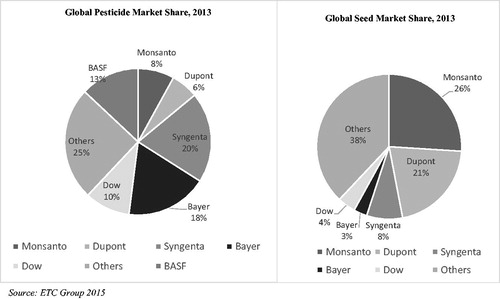

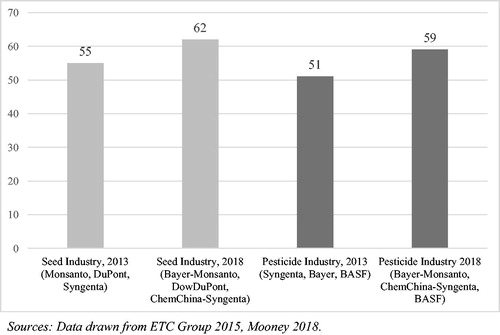

First, it is important to outline the extent to which the global market for agricultural inputs is already highly concentrated (e.g. Fuglie et al., Citation2011; Howard, Citation2016; Mooney, Citation2018). In 2013, prior to a series of recent mergers in the sector (outlined below), the global pesticide market was worth approximately US$54 billion, of which the six largest firms (collectively referred to as ‘the Big Six’ – Monsanto, Bayer, Dow, DuPont, Syngenta, and BASF) controlled a 75% share, with the top three (Syngenta, Bayer, and BASF) alone accounting for a full 51% of the market. In the global seed industry, worth US$39 billion, the same six firms held a combined 62% share of the market in 2013, with the top three (Monsanto, DuPont, and Syngenta) controlling a full 55% share (ETC Group, 2015, p. 5; see ). As outlined in the previous section, common ownership by the five largest asset management companies in 2016 was significant across each of the Big Six agricultural input firms, especially in the cases of Bayer, Monsanto, Dow, and DuPont (see above).

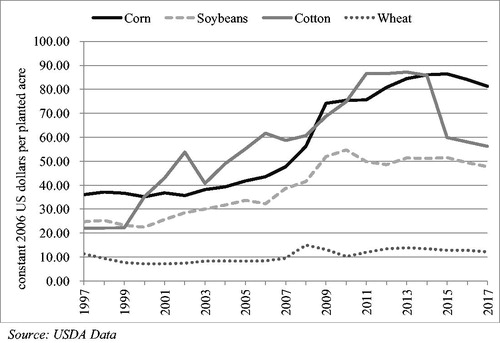

As noted in the wider literature, the ability of firms to raise prices without associated increases in quality or service is potentially much higher in markets that are already concentrated (OECD, Citation2017, p. 20; Diez et al., Citation2018, p. 13), and given the high degree of concentration in the agricultural input sector, it is likely that common ownership has contributed to price increases for both seeds and chemicals. With respect to seed prices, for example, data from the USDA shows that from 1997 to 2017, the inflation adjusted per acre price of corn, soy, and cotton seed (three key crop seeds for which the Big Six agricultural input firms dominate) more than doubled, while the inflation adjusted per acre price of wheat seed (for which research and development largely takes place in the public realm rather than by the Big Six input firms) remained flat over that same period (see ). There are many factors that affect changing farm input prices (Fuglie, Heisey, King, & Schimmelpfennig, Citation2012), and it is difficult to isolate their relative effects without a detailed statistical analysis. However, one recent study finds that common ownership is responsible for approximately 15% of price increases for corn, cotton and soy seed over the 1997–2017 period, while corporate concentration more generally is responsible for approximately another 14% (Torshizi & Clapp, Citation2018).

Figure 5. Market share of top three firms in the global seed and pesticide industries, before and after recent mergers, 2013 and 2018.

Since 2016, the agricultural input sector has been dramatically reconfigured by a series of mergers and acquisitions that have seen some of the biggest players combined into giant firms that command significant market shares. While there are a number of potential explanations for these mergers, such as a drive for efficiencies and a desire to develop product complementarities (OECD, Citation2018), there is some logic to the idea that common ownership could also have played a role. Indeed, the financial investment context appears to be highly relevant to the timing of the mergers. Low commodity prices over the 2013–2016 period depressed demand for the products sold by international seed and chemical companies and led to weaker returns for those firms. Shareholders, including the large asset management companies, could plausibly have encouraged those firms to pursue mergers in order to expand their market share as a means to boost share values (Clapp, Citation2018). The extent to which the asset management companies played a role in these mergers is a question that merits further empirical research. Regardless of the main drivers of the mergers, the result is a much more concentrated sector following consolidation. As of 2018, the top three seed firms (Bayer-Monsanto, Corteva Agriscience (DowDupont), and ChemChina-Syngenta) controlled 62% of the market (up from a 55% share for the top three firms in 2013), and the top three agro-chemical firms (Bayer-Monsanto, ChemChina-Syngenta, and BASF) controlled 59% of the market (up from a 51% share for the top three firms in 2013; ETC Group, 2015; Mooney, Citation2018).

The fact that the largest firms that currently dominate the agricultural input sector are now larger and command even more market share creates a context in which it is difficult for new firms to enter the market. Over the past 20 years, the dominant firms have developed seed and chemical technologies that were protected by patents that have functioned as powerful barriers to entry (Fuglie et al., Citation2012). These types of technologies require enormous capital outlays, which is difficult for new entrants to match. Further, the largest firms in the sector are increasingly working together in ways that lock in their dominance as a concentrated group, effectively shutting out new entrants into the market. As Howard (Citation2015) notes, the firms that dominate in the sector are collaborating with one another on their seed and chemical research activities through a series of cross-licencing and collaboration agreements that further entrench their collective commitment to this model of agriculture, and make it difficult for new players to break into the market.

The increased market power associated with rising common ownership, as described above, has the potential to result in broader societal outcomes. To gain greater insight into this potential, it is helpful to look to work that examines the implications of corporate concentration in the food system (IPES Food, 2017). To begin, more market power on the part of agrifood firms could result in greater inequality within the food system. As critics have noted in the face of the mergers transforming the agricultural input sector, if firms are able to increase prices based simply on their enhanced market power rather than on the basis of improved product quality or choice, those higher prices are likely to translate into lower incomes for farmers, or higher food prices for consumers, or some combination of both (American Antitrust Institute, Food & Water Watch, & National Farmers Union, Citation2016; Friends of the Earth, Citation2017). Inequality can also arise as a result of workers being made redundant, especially in instances where merging firms reduce their combined workforce in order to achieve cost savings in the newly merged firm. Both Dow-DuPont and Bayer-Monsanto, for example, presented justification for their respective mergers on the grounds that they could achieve cost ‘synergies’ through such a strategy (e.g. Bayer, Citation2016; Dow & Dupont, 2016). In early 2019, Bayer announced plans to eliminate 12,000 jobs – 10% of its workforce – in a cost-cutting move following its acquisition of Monsanto (Buck Citation2019).

Levels of investment and innovation in the sector could also be weakened and/or narrowed by growing market power that can arise as a result of high levels of common ownership. Common ownership, for example, may discourage firms from innovating in ways that are either costly for the individual firm or that might harm the profitability of other firms in the sector, or both. When evaluating the effects of the Dow-DuPont merger in 2017, for example, the European Commission concluded that incentives to engage in R&D were likely to be dampened by high levels of common ownership. It noted in its decision:

…the decision taken by one firm, today, to increase innovation competition has a downward impact on its current profits and is also likely to have a downward impact on the (expected future) profits of its competitors. This, in turn, will negatively affect the value of the portfolio of shareholders who hold positions in this firm and in its competitors. Therefore, as for current price competition, the presence of significant common shareholding is likely to negatively affect the benefits of innovation competition for firms subject to this common shareholding. (European Commission, Citation2017, p. 383).

Investment and innovation in the sector can also be weakened when common ownership contributes to more consolidation among firms in the sector and/or creates higher barriers to entry. In the 1980s to 1990s, the merger of smaller firms in the sector to form larger ones did result in larger R&D budgets for the merged firms, which enabled companies to develop new seed traits and varieties. Fuglie shows that by the late 2000s, however, increased concentration in the sector slowed the intensity of private research on biotech corn, cotton, and soy relative to what would have been the case without that level of concentration (Fuglie et al., Citation2012). Indeed, as noted above, in the case of the recent Dow-DuPont and Bayer-Monsanto mergers, the firms indicated that they would be introducing some cuts to their R&D budgets once the firms merged, in order to reduce duplication and save costs. Dow and DuPont referred to this as ‘global optimization of R&D’ in its agriculture division (e.g. Dow & Dupont, 2016, p. 22). One analyst noted that of the thousands of R&D job losses at Dow and DuPont associated with the merger: ‘it’s almost the death of innovation’ (quoted in Parrish, Citation2016). The result of this weakening of R&D spending is that firms tend to focus narrowly on expanding market share for technologies that have already been developed or exploring only those innovations that deliver the highest commercial payoffs. As the International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems notes, this tendency is likely to result in fewer innovations that will benefit smallholder farmers in the Global South (IPES Food, 2017, p. 28).

A relative lack of competition from new entrants, such as start-ups based on new cost-saving or more environmentally sustainable innovations, could also have the effect of reinforcing the current high cost industrial agricultural model promoted by the dominant firms. As noted above, the vast majority of farm inputs that are brought to market by the largest firms are genetically modified seeds and associated agro-chemicals. This model of farming promoted by these firms relies on large-scale monoculture farming practices that have been associated with high fossil fuel use, climate change, biodiversity loss, water shortages, and chemical run off from the increased application of fertilizers and pesticides (Benbrook, Citation2016; Foley et al., Citation2011; Garnett, Citation2013). The largest agricultural input firms are also increasingly teaming up with farm equipment companies that are developing digital farming platforms that they claim will result in more efficient use of resources, and thus improve sustainability (e.g. Bayer, Citation2016). However, these technologies are deeply integrated with the continued promotion of existing genetically modified seeds and associated herbicides (Bronson & Knezevic, Citation2016). Corporate market power incentivizes firms to lock in the profitability of these existing technologies (Mooney, Citation2018; IPES Food, 2017), rather than to experiment with other types of agricultural innovation such as lower-tech, agroecological farming practices that have been shown to be more sustainable (e.g. Altieri, Citation2018).

Corporate influence over food system policy and governance is also likely enhanced by the increased levels of market power and concentration that are associated with high levels of common ownership. The agricultural input firms have been very active in lobbying policymakers in both the US and the EU, spending millions of dollars every year in their efforts to influence policy and regulation (Clapp, Citation2018). Critics have warned that this kind of concentrated lobbying can lead to governments favoring the large-scale industrial agricultural model, which is likely to reduce the responsiveness of these firms to farmer and consumer demand for more sustainable agriculture and food systems (Friends of the Earth, Citation2017).

Conclusion

This paper has sought to bring investment in equity-related funds linked to the agrifood sector, and its potential consequences, to light. The paper makes the case that large asset management companies that market equity-related funds linked to the agrifood sector control a significant proportion of shares of the largest transnational food and agriculture firms. In this way, the world’s largest asset management firms and the dominant transnational agrifood firms – both very highly concentrated segements of the global economy – are increasingly entwined in ways that can subvert competition and undermine broader social goals. Large asset management firms have incentives to encourage the agribusiness firms in which they have a significant ownership stake to undertake strategies that result in higher returns to shareholders, especially by pursuing market strategies that benefit the entire sector, rather than the individual firms. Such incentives can lead to anti-competitive behavior, resulting in price mark-ups, mergers and acquisitions, and higher barriers to entry in those markets. As was shown with a closer look at the agricultural input sector, these corporate strategies can collectively lead to broader effects, such as greater inequality in the food system, a weakening of innovation in the sector, and enhanced market and political power of the sector’s leading firms. Further research is needed to assess whether and to what extent each of these trends are borne out in practice, as a first step to better understanding what policy directions is required to remedy the potential ill-effects of these financial investment and ownership patterns.

The research highlights an important aspect of financialization in the agrifood sector that to date has received relatively little attention: the way in which the rise of financial motives and institutions has effectively prioritized shareholder value in the food system via increased investment in equities by large asset management firms. As financial shareholders gain in significance – in this case, the large asset management companies – they can wield power to reshape the agrifood sector in new ways. With respect to the agricultural input sector as assessed here, this growing power of large common shareholders appears to have contributed to accelerating corporate concentration and market power in the sector, including in ways that have broader social and ecological consequences.

These insights regarding the role of shareholders in the agrifood sector are an important complement to the existing literature on the financialization of food, which focuses mainly on commodity and land investments and how these activities open new arenas for financial profit-making and represent a financialization of everyday life. In the case of equity-related investments in the agrifood sector, multiple aspects of financialization feature prominently. ETFs and index-based mutual funds, including those specifically linked to food and agriculture, represent new avenues for financial investment and profit, while ordinary individuals increasingly partake in these investment vehicles via their pension funds and individual retirement savings accounts. And as this paper has highlighted, the rise of these equity-linked investment funds also works to reshape agrifood systems in ways that prioritize the needs of shareholders over other social and environmental goals.

While the social and ecological impact of agricultural commodities and farmland investments sparked enormous public outcry and calls for improved international governance initiatives to address them, to date there has been little public awareness of financial investments in agrifood equities and their potential effects. This lack of attention is likely due to the fact that it is difficult to tease out patterns of equity investments in the sector in the first place. Further, the impacts of these investments are mediated through both asset management companies as well as agrifood firms, which makes tracing the wider implications of those investments especially challenging. There is, however, growing awareness among economic and legal analysts of heightened patterns of common ownership across the economy more generally, and a growing number of studies that point to its potential to encourage anti-competitive behaviors among firms. These studies have been accompanied by calls for strengthened anti-trust regulations that incorporate measures to address common ownership in merger control and competition policy decisions (e.g. Elhauge, Citation2016, Citation2018; Khan & Vaheesan, Citation2017; Posner, Morton, & Weyl, Citation2017). These studies have captured the attention of the OECD (Citation2017), and may signal future initiatives to tackle the problems created by these types of investment patterns, at least in the wider economy. These efforts, however, have already been challenged by the large asset management companies, who question the methodologies utilized by these analysts as well as the need for additional regulation (see, for example, Novick et al., Citation2017).

Early calls for stronger governance on commodities and land investments were also initially met with skepticism from financial institutions which pushed back against attempts to strengthen international governance regimes in ways that would prevent or at least soften the worst potential impacts of those investments. Further research is necessary to build a solid base on which to formulate policy directions moving forward in the case of equity-related investments in the food and agriculture sector.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Rachel McQuail for editorial and data support. Thanks are also due to Eric Helleiner, Sarah J. Martin, Mohammed Torshizi and three anonymous reviewers for helpful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jennifer Clapp

Jennifer Clapp is a Canada Research Chair in Global Food Security and Sustainability and Professor in the School of Environment, Resources and Sustainability at the University of Waterloo, Canada. She has published widely on the global governance of problems that arise at the intersection of the global economy, the environment, and food security. Her most recent books include Speculative Harvests: Financialization, Food, and Agriculture (with S. Ryan Isakson, Fernwood Press, 2018), Food, 2nd Edition (Polity, 2016), Hunger in the Balance: The New Politics of International Food Aid (Cornell University Press, 2012), and Corporate Power in Global Agrifood Governance (co-edited with Doris Fuchs, MIT Press, 2009).

Notes

1 Equities typically refer to stocks or shares in a company. Equity funds that invest in firms that are publicly-traded on the stock exchange are sometimes referred to as public equity funds, which is distinct from private equity funds that focus on investments in private firms that are not publicly-traded on the stock exchange.

2 This phenomenon is also sometimes referred to as ‘horizontal shareholding’ (e.g. Elhauge Citation2016) or institutional cross-ownership (e.g. Brooks et al., Citation2018). In this paper, I refer to the phenomenon as ‘common ownership’ (for a review, see Schmalz Citation2018).

References

- Aitken, R. (2007). Performing capital: Toward a cultural economy of popular and global finance. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Altieri, M. A. (2018). Agroecology: The science of sustainable agriculture. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

- American Antitrust Institute, Food & Water Watch, & National Farmers Union (2016). Letter to U.S. Department of Justice Re: The Proposed Dow-DuPont Merger. Retrieved from: https://www.foodandwaterwatch.org/sites/default/files/aai_fww_nfu_dow-dupont_5.31.16.pdf

- Azar, J., Schmalz, M. C., & Tecu, I. (2018). Anti-competitive effects of common ownership. Journal of Finance, 73(4), 1513–1565. doi:10.1111/jofi.12698

- Azar, J., Raina, S., & Schmalz, M. C. (2016). Ultimate ownership and bank competition. Working paper. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2710252 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2710252

- Baines, J. (2017). Accumulating through food crisis? Farmers, commodity traders and the distributional politics of financialization. Review of International Political Economy, 24(3), 497–537. doi:10.1080/09692290.2017.1304434

- Bayer (2016). Bayer and Monsanto create a global leader in agriculture. Retrieved from: https://media.bayer.com/baynews/baynews.nsf/id/ADSF8F-Bayer-and-Monsanto-to-Create-a-Global-Leader-in-Agriculture

- Benbrook, C. M. (2016). Trends in glyphosate herbicide use in the United States and globally. Environmental Sciences Europe, 28(3), 1–15.

- BlackRock (2018a). COW – iShares Global Agriculture Index ETF Fact Sheet – As of November 30, 2018. Retrieved from: https://www.blackrock.com/ca/individual/en/products/239548/ishares-global-agriculture-index-fund

- BlackRock (2018b). VEGI – iShares MSCI Global Agriculture Producers ETF Fact Sheet– As of September 30, 2018. Retrieved from: https://www.ishares.com/us/products/239652/ishares-msci-global-agriculture-producers-etf

- BlackRock (2018c). BlackRock World Agriculture Fund Fact Sheet – As of November 30, 2018. Retrieved from: https://www.blackrock.com/hk/en/products/229904/blackrock-world-agriculture-fund-a2-usd

- BlackRock (2018d). BlackRock iShares Core S&P 500 ETF – Key Facts as of September 30, 2018. Retrieved from: https://www.blackrock.com/investing/products/239726/ishares-core-sp-500-etf

- BlackRock (2018e). BlackRock iShares Global Consumer Staples ETF Fact Sheet – As of September 30, 2018. Retrieved from: https://www.ishares.com/us/products/239740/ishares-global-consumer-staples-etf

- Bronson, K., & Knezevic, I. (2016). Big data in food and agriculture. Big Data & Society, 3(1), 1–5.

- Brooks, C., Chen, Z., & Zeng, Y. (2018). Institutional cross-ownership and corporate strategy: The case of mergers and acquisitions. Journal of Corporate Finance, 48, 187–216. doi:10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2017.11.003

- Buck, T. (2019). Bayer Keen to Shift Attention from Monsanto Woe to Tech Vision. Financial Times. January, 24

- Burch, D., & Lawrence, G. (2013). Financialization in agri-food supply chains: Private equity and the transformation of the retail sector. Agriculture and Human Values, 30(2), 247–258. doi:10.1007/s10460-012-9413-7

- Capital Group. (2018). American Mutual Fund Fact Sheet – As of September 30, 2018. Retrieved from: https://www.capitalgroup.com/us/pdf/shareholder/mfaassx-003_amfffs.pdf

- Clapp, J., & Isakson, S. R. (2018). Speculative harvests: Financialization, food, and agriculture. Halifax, NS: Fernwood.

- Clapp, J. (2018). Mega-mergers on the menu: Corporate concentration and the politics of sustainability in the global food system. Global Environmental Politics, 18(2), 12–33. doi:10.1162/glep_a_00454

- Clapp, J. (2015). Distant agricultural landscapes. Sustainability Science, 10(2), 305–316. doi:10.1007/s11625-014-0278-0

- Clapp, J. (2014). Financialization, distance and global food politics. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 41(5), 797–814. doi:10.1080/03066150.2013.875536

- Cotula, L. (2013). The great African land grab?: Agricultural investments and the global food system. London, UK: Zed Books.

- Davis, G. (2008). A new finance capitalism? Mutual funds and ownership re-concentration in the United States. European Management Review, 5(1), 11–21. doi:10.1057/emr.2008.4

- De Schutter, O. (2010). September). Food commodities speculation and food price crises. UN special rapporteur on the right to food briefing note 02. Retrieved from: https://www2.ohchr.org/english/issues/food/docs/briefing_note_02_september_2010_en.pdf

- Desmarais, A. A., Qualman, D., Magnan, A., & Wiebe, N. (2017). Investor ownership or social investment? Changing farmland ownership in Saskatchewan, Canada. Agriculture and Human Values, 34(1), 149–166. doi:10.1007/s10460-016-9704-5

- Diez, F., Leigh, D., & Tambunlertchai, S. (2018). Global market power and its macroeconomic implications. IMF Working Papers, 18(137), 1. Retrieved from: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2018/06/15/Global-Market-Power-and-its-Macroeconomic-Implications-45975

- Dow and DuPont (2016). Merger of equals update. Retrieved from: https://s2.q4cdn.com/752917794/files/doc_presentations/2016/presentation/DWDP-Investor-Deck-Final.pdf

- Drutman, L. (2015). How corporate lobbyists conquered american democracy. The Atlantic. Retrieved from: https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2015/04/how-corporate-lobbyists-conquered-american-democracy/390822/

- Elhauge, E. (2018). Horizontal shareholding harms our economy – And why antitrust law can fix it. SSRN Electronic Journal. Retrieved from: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3293822

- Elhauge, E. (2016). Horizontal shareholding. Harvard Law Review. 129(5), 1267–1317. Retrieved from: https://harvardlawreview.org/2016/03/horizontal-shareholding/

- Epstein, G. A. (2005). Introduction: Financialization and the world economy. In G. A. Epstein (Ed.), Financialization and the World Economy (pp. 3–16). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- ETC Group. (2015). Breaking bad: Big Ag Mega-Mergers in Play: Dow + DuPont in the Pocket? Next: Demonsanto? Communiqué #115. Retrieved from: http://www.etcgroup.org/sites/www.etcgroup.org/files/files/etc_breakbad_23dec15.pdf

- ETFGI (2018). ETFGI ETF/ETP Growth Charts: Global. Retrieved from: https://etfgi.com

- European Commission (2017). Case M.7932 Dow/DuPont. Retrieved from: http://ec.europa.eu/competition/mergers/cases/decisions/m7932_13668_3.pdf

- Fairbairn, M. (2014). ‘Like gold with yield’: Evolving intersections between farmland and finance. Journal of Peasant Studies, 41(5), 777–795. doi:10.1080/03066150.2013.873977

- Fichtner, J., Heemskerk, E. M., & Garcia-Bernardo, J. (2017). Hidden power of the big three? Passive index funds, re-concentration of corporate ownership, and new financial risk. Business and Politics, 19(02), 298–326. doi:10.1017/bap.2017.6

- Fidelity Investments. (2018a). Select Consumer Staples Portfolio Mutual Fund FDFAX Fact Sheet – As of November 30, 2018. Retrieved from: https://fundresearch.fidelity.com/mutual-funds/summary/316390848

- Fidelity Investments. (2018b). Fidelity MSCI Consumer Staples Index ETF Fact Sheet – As of September, 30, 2018. Retrieved from: https://institutional.fidelity.com/app/funds-and-products/etf/snapshot/FIIS_ETF_FSTA/fidelity-msci-consumer-staples-index-etf.html

- Flood, C. (2018). ETF Market Smashes through $5tn Barrier after Record Month. Financial Times. Retrieved from: https://www.ft.com/

- Foley, J. A., Ramankutty, N., Brauman, K. A., Cassidy, E. S., Gerber, J. S., Johnston, M., … Zaks, D. P. M. (2011). Solutions for a Cultivated Planet. Nature, 478(7369), 337–342. doi:10.1038/nature10452

- Food and Agricultural Organization. (2017). Agriculture organization. The future of food and agriculture: Trends and challenges. Rome: FAO.

- Friends of the Earth et al. (2017). Sign-on Letter on Agrochemical and Seed Industry Mergers. Retrieved February 13, from https://www.panna.org/sites/default/files/letter-regarding-agricultural-mergers.pdf

- Froud, J., Haslam, C., Johal, S., & Williams, K. (2000). Shareholder value and financialization: Consultancy promises, management moves. Economy and Society, 29(1), 80–110. doi:10.1080/030851400360578

- Froud, J., Johal, S., Leaver, A., & Williams, K. (2006). Financialization and strategy: Narrative and numbers. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Fuchs, D. (2007). Business power in global governance. Boulder, CO: Lynn Reinner.

- Fuglie, K. O., Heisey, P. W., King, J. L., Pray, C. E., Day-Rubenstein, K., Schimmelpfennig, D., L., … Karmarkar-Deshmukh, R. (2011). Research Investments and Market Structure in the Food Processing, Agricultural Input, and Biofuel Industries Worldwide. USDA Economic Research Service. Retrieved from: https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/44951/11777_err130_1_.pdf?v=41499

- Fuglie, K. O., Heisey, P., King, J., & Schimmelpfennig, D. (2012). Rising concentration in agricultural input industries influences new farm technologies. USDA economic research service. Amber Waves, Retrieved December 3, from https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2012/december/rising-concentration-in-agricultural-input-industries-influences-new-technologies/

- Garnett, T. (2013). Food sustainability: Problems, perspectives and solutions. The Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 72 (1), 29–39. doi:10.1017/S0029665112002947

- Ghosh, J. (2010). The unnatural coupling: Food and global finance. Journal of Agrarian Change, 10(1), 72–86. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0366.2009.00249.x

- Global, X. (2018). SOIL – Global X Fertilizers/Potash ETF Fact Sheet – As of September, 30, 2018. Retrieved from: https://www.globalxfunds.com/content/files/SOIL-factsheet.pdf

- He, J., & Huang, J. (2017). Product market competition in a world of cross-ownership: Evidence from institutional blockholdings. The Review of Financial Studies, 30(8), 2674–2718. doi:10.1093/rfs/hhx028

- Helleiner, E. (2018). Positioning for stronger limits? The politics of regulating commodity derivatives markets. In E. Helleiner, S. Pagliari, & I. Spagna (Eds.), Governing the World’s Biggest Market: The Politics of Derivatives Regulation After the 2008 Crisis (pp. 199–225). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- HighQuest Partners, US (2010). Private financial sector investment in farmland and agricultural infrastructure. OECD food, agriculture, and fisheries papers, no. 33. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Howard, P. H. (2016). Concentration and power in the food system: Who controls what we eat? London, UK: Bloomsbury.

- Howard, P. H. (2015). Intellectual property and consolidation in the seed industry. Crop Science, 55(6), 2489–2495. doi:10.2135/cropsci2014.09.0669