Abstract

How do crisis perceptions interrelate with the emergence and re-constitution of policy problems? By using a novel combination of interviews with a content and network analysis of hand-coded parliamentary questions, this article maps the emergence of brain drain as a policy problem at the level of the European Union and follows the evolution of the issue over the last four parliamentary periods (from 1999 to 2019). I identify a skills storyline (emphasizing reform of vocational and educational training to address skills mismatches) and a solidarity storyline (emphasizing worker conditions, rights, and wages) as the main contending narratives that define the contours of the debate. The article analyzes how each of these storylines interacted over time with changes in the perception of crisis urgency facing the European Union in ways that run counter to what we would expect. I explain this by examining the capacity of each storyline to problematize or de-problematize the movement of labor, as well as their institutionalization over time. The article contributes to the study of the political economy of labor mobility with an original case study from the EU’s Single Market, and challenges conventional wisdom regarding the role of framing during times of crisis.

Introduction

The rules and politics of labor mobility are becoming increasingly contentious and important to the political economy of the European Union (EU). Where issues such as brain drain within the Single Market used to be taboo, European politicians have recently become bolder in drawing attention to the potential ‘dark sides’ of labor mobility (Coman, Citation2017). Brain drain reflects a tendency for human capital to agglomerate where it is already abundant ‘in what appears as an international competition to attract global talent’ (Beine, Docquier, & Rapoport, Citation2008). The question of whether and to what extent this competition also occurs within the borders of the Single Market is unclear (Atoyan et al., Citation2016; Barslund & Busse, Citation2016; Galgóczi, Leschke, & Watt, Citation2012; Münz, Citation2014). But what is clear, is that the politics of labor mobility are only loosely connected to the economic reality of labor markets, which was demonstrated most forcefully in the case of the Brexit debate (Hobolt, Citation2016; Schmidt, Citation2017). Regardless of how labor flows may be impacting the economy, Member States are increasingly eager to be perceived as being in control (or ‘taking back control’, as the Leave slogan in the Brexit campaign put it) of migration flows (Menz, Citation2010). The EU’s experience of ‘poly-crisis’ (debt, unemployment, refugees and so on) in recent years has only exacerbated this need (Seabrooke & Tsingou, Citation2019).

What we see when looking at brain drain in the European context is the emergence and re-constitution of a policy area through contesting forms of ‘problematization’ (Bacchi, Citation2012; Hülsse, Citation2007). In this article, I address the following over-arching question: how do changing crisis perceptions interrelate with the emergence and re-constitution of policy problems? The way the policy problem of intra-European ‘brain drain’ has been framed as a problem has varied over three periods of recent political discourse: the pre-crisis years (coinciding with the parliamentary terms of the Prodi Commission and the first Barroso Commission: 1999–2009), the height of the crisis (2009–2014, the second Barroso Commission) and the post-crisis years (2014–2019, the Juncker Commission). At the same time, policymakers have been shifting their attention back and forth between a drain from the newer Member States in Eastern Europe (which I refer to as the Eastern drain), and the older, but crisis-stricken Member States in Southern Europe (which I refer to as the Southern drain). During each of these stages, the conflict has been shaped by the competition between two opposed ‘storylines’ (Hajer, Citation1997; Tomlinson, Citation2010): a skills storyline and a solidarity storyline. Each of these storylines aligns particular actors, causal stories, political preferences and economic assumptions that coordinate expectations about what brain drain is and what is to be done about it. These storylines represent two different collections of frames that I identified through a manually coded content analysis of parliamentary questions raised in the European Parliament as well as semi-structured interviews with 27 key policy actors. Using discourse network analysis (Leifeld, Citation2016), I discover the connections between frames and actors, allowing the storylines to emerge inductively through the analysis. By observing the emergence and shifting pressures over time on the policy area, the analysis follows the logic of a longitudinal case study (Gerring & Cojocaru, Citation2016).

The puzzle of this case study is that the relative dominance of each storyline at different stages of the crisis runs counter to what we should expect. At the height of the Eurozone crisis, the skills storyline and not solidarity, was dominant. The skills storyline encourages the free movement of labor and views brain drain as caused by skills mismatches. In contrast, the solidarity storyline views brain drain as caused by macroeconomic differences between EU Member States, leading to excessive differences in wages, rights and conditions for workers. The crisis made evident and greatly exacerbated these macroeconomic differences – so why was the conversation about skills? According to conventional wisdom about the relationship between framing and crisis perceptions, we should expect emotional, heuristic responses at the height of the crisis and greater rational and technical deliberation following it (Seabrooke & Tsingou, Citation2019; Widmaier, Citation2016; Widmaier, Blyth, & Seabrooke, Citation2007). This should have led to ‘fast-thinking’, emotional responses directly addressing and appealing to solidarity, and not the ‘slow-thinking’ calculation of efficiently reallocating skilled labor to address skills gaps and mismatches. Additionally, in the post-crisis years, the focus on skills has remained and increased, even in the face of a mounting challenge from the solidarity storyline. I explain the puzzle by demonstrating the capacity of the skills storyline to naturalize and de-problematize brain drain as a policy issue, turning it into a complementary part of the solution to the Eurozone crisis. Increasing institutionalization of the skills storyline over time explains its enduring dominance. The institutionalization of a successful storyline is to be expected when viewing framing as a process, as I will explain in the theoretical section of the article.

The article contributes to the study of the international political economy (IPE) of migration and labor mobility in several ways. At least since Saxenian’s (Citation2007) study on ‘the new Argonauts’ (technically skilled entrepreneurs from primarily India, China and Taiwan that travel back and forth between Silicon Valley and their home countries), there has been a growing appreciation within IPE of ‘brain circulation’ as a powerful economic force for development of peripheral regions (Cañibano & Woolley, Citation2015; Graham, Citation2014; Pellerin & Mullings, Citation2013; Phillips, Citation2009). Brain circulation carries political risks, however, especially if it leads to personnel or skills shortages in politically sensitive sectors such as health, where studies have analyzed the social and political repercussions of the neoliberal and transnational restructuring of care provision (LeBaron, Citation2010; Woodward, Citation2005; Yeates, Citation2009). This makes it clear that more attention is required to the rules and politics governing transnational labor mobility. This study of the European brain drain debate focuses an in-depth longitudinal case study on exactly this question.

In the next section, I turn to theoretical considerations of how to conceptualize the relationship between frames, storylines and crises. Subsequently, I provide the details of my data and method. This is followed by the analysis, which itself proceeds according to the three stages specified above (1999–2009, 2009–2014 and 2014–2019). In the discussion section, I then consider what the analysis tells us about the relationship between frames and crisis perceptions, as well as reflect on the broader institutional environment of the brain drain debate. The conclusion presents theoretical, empirical and practical implications of the study and proposes next steps.

Theoretical overview: frames, storylines and crises

Within IPE, there is a strong tradition for appreciating the sociological and ideational dimensions of crises (e.g. Blyth, Citation2002), in other words granting that crisis perceptions matter. Widmaier, Blyth, and Seabrooke (Citation2007, p. 749) develop this strain of thought by theorizing a more ‘agent-centered’ constructivism. During times of crisis, they argue, ‘agents’ persuasive practices come to the fore’. These persuasive practices are understood as examples of ‘strategic social construction’ (Finnemore & Sikkink, Citation1998, p. 888), in which agents engage in efforts to shape shared meanings and interpretations of events. The underlying logic is that although the material changes of a crisis impart objective effects on societies, agents act upon their interpretations of the meanings of those effects rather than on the effects themselves. These interpretations do not only condition agents’ perceptions of events but also render them contentious when incompatible interpretations collide (Widmaier et al., Citation2007, p. 748).

When it comes to crisis perceptions themselves and how they intervene in governance, here I distinguish between what Seabrooke and Tsingou (Citation2016, Citation2019, pp. 470–471) call ‘fast-burning’ and ‘slow-burning’ crises. They argue that to assess ‘the intensity, tempo, and rhythm of crises … we need a framework that considers what is in leaders’ minds and also makes connections between governing institutions and social change’. Whether crises are fast or slow is primarily a question of interpretation and perception on the part of policymakers and publics as they confront problematic and ambiguous situations. Fast-burning crises are perceived as obvious and alarming and characterized by urgent demands for political action. Knowledge in these situations is ‘hot’, meaning that interests seek clear and applied models and ideas to put out the flames quickly. Slow-burning crises, on the other hand, are less obvious, smoldering away until there is sufficient public interest in them. Their effects are perceived as extending beyond normal political and business cycles. An example of a fast-burning crisis would be the skyrocketing youth unemployment during the Eurozone crisis, while a slow-burning example would be the political and socioeconomic consequences of chronic unemployment or demographic change.

The purpose of Seabrooke and Tsingou’s (Citation2019, p. 471) framework is to ‘attain the subject positions on how crises will evolve’. To further differentiate the types of subject positions that those involved in a crisis can experience, they distinguish between the tempo and intensity of crises. Tempo is defined as ‘the speed at which policy failures are transmitted between authorities and social actors’, and intensity as ‘a combination of the political salience and emotional valence that an issue has for both authorities and social actors’ (p. 471). Because both of these properties are claims about the inter-subjective experiences of involvement in a crisis, their framework lets us unpack varieties of crisis situations from the vantage point of an agent-centered constructivism without having to mobilize claims about objective or material changes ‘on the ground’. Crisis perceptions effectively close down certain meanings and interpretations of events in directions that can exhibit patterns over time and become the object of empirical scrutiny (e.g. Cross & Ma, Citation2015).

In making the distinction between fast- and slow-burning crises, Seabrooke and Tsingou join a number of other scholars drawing loosely on the ideas contained in Kahneman’s (Citation2012) popular work, Thinking, Fast and Slow. For example, Widmaier (Citation2016) distinguishes between ‘fast-thinking’, emotional reactions to crises and ‘slow-thinking’, rational responses and policy settlements to study the interaction between economic ideas and the temporality of political life. Schmidt (Citation2017) draws on Kahneman’s understanding of the framing power of ‘anchors’ and heuristics to find parallels between the Brexit referendum and the election of Donald Trump.

What the fast-thinking versus slow-thinking frameworks all assume is that rational, technical treatment of policy issues (Kahneman’s ‘Type 2 thinking’ or Widmaier’s ‘slow-thinking’) is more likely during ‘slow-burning’ periods of limited political urgency and attention to that issue, and vice versa, that heuristics (Kahneman’s ‘Type 1 thinking’ or Widmaier’s ‘fast-thinking’), ‘persuasive practices’ (Widmaier et al., Citation2007) or ‘strategic social construction’ (Keck & Sikkink, Citation1998) play a greater role during ‘fast-burning’ periods of alarm and emergency. These frameworks equate framing (‘persuasive practices’ or ‘strategic social construction’) with fast-thinking heuristics and place it in opposition to slow-thinking rational deliberation. This move underappreciates the full meaning of framing as a theory of social action. In contrast to this conventional wisdom, I argue that whether a particular run of social interaction is understood by participants to be fast-burning and dominated by framing and heuristics or slow-burning and dominated by rational deliberation is itself the outcome of framing processes.

Fast and slow are two different frames of activity – the register of a crisis (whether it is perceived as fast-burning or slow-burning and the types of tasks and thinking that are viewed as associated with each of these) is established through actors deploying frames and storylines strategically. In other words, it is not only during fast-burning crises that we see strategic social construction, and not only during slow-burning crises that we see technical, rational deliberation. The analysis will show that it is completely within the capacity of actors to deploy frames and storylines that turn this convention on its head, making ‘fast-thinking’ emotional responses effective during slow-burning crises, and slow-thinking rational responses effective during fast-burning crises. Framing is completely endemic to social interaction (it is the essence of social interaction) and not only present when policy actors are stressed by perceptions of high intensity and tempo.

Connecting crises to frames and storylines

To see crises as frames of activity follows from Goffman’s (Citation1974, pp. 10–11) description of a ‘frame’: ‘definitions of a situation are built up in accordance with principles of organization which govern events – at least social ones – and our subjective involvement in them’. To analyze frames is to examine the ‘organization of experience’. Fundamentally ambiguous situations may be framed as a crisis, but they may also not be – policy actors can be strategic in terms of how they choose to deal with this ‘inherent indeterminacy’ (Best, Citation2008, Citation2012). If they are framed as a crisis, they may be framed as different kinds of crises, for example, fast-burning or slow-burning ones (Seabrooke & Tsingou, Citation2019). This framing always takes place against the background of ‘real things’ happening in the world outside the subjective experiences of agents, but in keeping with the tenets of an agent-centered constructivism (Widmaier et al., Citation2007), what matters for whether crises are fast or slow are the perceptions of agents and how these are shaped through interactions with other agents. We can, therefore, productively analyze crises by considering primarily what is in their minds (through the proxy of what they say).

This argument distinguishes between framing as a process and frames as objects. Frames as objects can be understood as concrete pieces of communication that ‘select some aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient in a communicating text, in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation and/or treatment recommendation for the item described’ (Entman, Citation1993). But frames as objects are only the individual, constituent parts of the total ‘organization of experience’ (Goffman, Citation1974), and they have to be considered together with their connection to other frames and over time for the analyst to observe framing as a process. In other words, experiences are organized by more than just one framing object. For example, an impact assessment for a public policy contains multiple individual frames in the form of sections of communicating text that variously promote different problems, causes, solutions and moral evaluations – all to the detriment of other opposed sets of problems, causes, solutions and moral evaluations. An impact assessment is only one text that competes with various other texts (such as strategy documents, media articles, or speeches) in comprising the total organization of experience of a public policy debate.

This style of ‘cognitive analysis of public policy’ (Muller, Citation2000) argues that debates about public policy should be seen as processes where societies construct their relationship to the world, and that acting on the world requires a representation of the problem you mean to act on. It is these ‘référentiels’ or ‘frames of reference’ that organize perceptions and through which proposed solutions are made meaningful. This is a theme that McNamara (Citation2015) explores in detail in her study on the role of story and narrative in constructing European identity. She argues that the deliberate transformation of symbols and practices of everyday life in Europe played a decisive role in the cultural legitimation of the EU’s political development.

Both policy problems and solutions emerge out of the stories policy actors tell each other, which implies that ‘political changes may therefore well take place through the emergence of new storylines that re-order understandings’ (Hajer, Citation1997, p. 57). Especially the way problems are defined and represented (how they are ‘problematized’) is an important and contested process (Bacchi, Citation2012; Hülsse, Citation2007), in that their particular framing entails more direct connections to some set of solutions rather than others. When frames are bundled together they form storylines that act as ‘a generative sort of narrative that allows actors to draw upon various discursive categories to give meaning to specific physical or social phenomena… they suggest unity in the bewildering variety of separate discursive component parts of a problem…’ (Hajer, Citation1997, p. 57). Storylines simplify the picture by arranging sets of frames in narrative sequences that involve actors and causal plots. Storylines are aggregated and stabilized arrangements of frames. They are manifestations of multiple frame objects that tend to appear together and support each other. In doing so, they present one particular framing process that establishes an organization of experience.

If the storyline succeeds in providing an organization of experience that solves coordination problems, for example by permitting a new understanding of a problem that opens the policy imagination to new solutions, or by re-casting a problem such that it is no longer a problem, the storyline stabilizes even further, in the sense that the collection of frames becomes more tightly interconnected and more strongly embedded in the policy imagination of involved actors. Another way to think of this is that the actors who achieve their goals with the use of a particular storyline incorporate it into their habitus – they develop a ‘feel for the game’ through socialization and habitualization (Bourdieu, Citation1990, pp. 66–67). As storylines inculcate in participants this practical sense for how to approach a particular policy problem, they become ‘social rules [that] do not simply describe but actively generate and confirm social and economic realities’ (Hoffman & Ventresca, Citation1999, p. 1373). We might say that, in the manner suggested here, successful storylines tend to become institutionalized, to become more permanently embedded in broader discursive structures.

To sum up this section, crises as viewed from the vantage point of agent-centered constructivism stresses the subjective experiences of those involved in fundamentally ambiguous and malleable situations. Whether a given crisis is understood to be fast-burning or slow-burning depends on the perceptions of involved actors, and in particular on how those perceptions are shaped by the frames and storylines that circulate throughout a policy debate. Whether fast-thinking or slow-thinking responses are deemed appropriate is not conditional on the intensity or tempo of the crisis, but depends on how storylines establish a given policy problem through processes of problematization that connect representations of the problem with a given set of solutions to that problem. In the next section, I provide the details of a method for extracting storylines from policy debates and studying their interaction and evolution over changing periods of crisis.

Data and methods

To study storylines, and to allow them to appear inductively out of the mass of communicative texts all competing to establish the dominant frame of reference for a policy debate, we require a way of identifying individual frame objects and tracing their connections to other frame objects and how those change over time in the framing process. Studies on ‘discourse networks’ address this problem using content analysis to trace and chart specific frame objects by policy actors and using network analysis to discover which sets of frames tend to be used together (Fisher, Waggle, & Leifeld, Citation2013; Hurka & Nebel, Citation2013; Kukkonen, Ylä-Anttila, & Broadbent, Citation2017; Leifeld, Citation2013b; Leifeld & Haunss, Citation2012). Similar approaches combining content analysis with network analysis have been conducted within IPE on financial and economic governance (Ban, Citation2016; Ban, Seabrooke, & Freitas, Citation2016). When mapping discourse networks, the storylines emerge out of the analysis as constellations of frames that change over time. The relative importance of frames within each storyline can be deduced from their centrality in the network, their connections to other frame objects, and their frequency of usage by different policy actors. The relative dominance of each storyline can be assessed by considering the aggregate positions and connections of the multiple frame objects that comprise each storyline. I include interviews with key policy actors to probe deeper into the brain drain policy debate and corroborate the frames and storylines that came out of the content and network analysis of parliamentary questions. As a qualitative multi-method approach, the combination of two different data sources and methods increases robustness through a complementary mobilization of various types of evidence (Lamont & Swidler, Citation2014).

Parliamentary questions

In legislative studies, parliamentary questions have been understood as harboring useful information about the preferences and behavior of members of parliament, as well as how they view their roles and responsibilities (Martin, Citation2011; Raunio, Citation1996). Studies on parliamentary questions at the EU-level stress their potential for linking the electorates of MEPs to European issues and exercising executive and regulatory scrutiny (Auel & Raunio, Citation2014; Proksch & Slapin, Citation2011). Because MEPs are sensitive both to domestic-level issues and to the political inclinations of their respective groups, they provide useful data on how brain drain is brought from the domestic level to the EU-level and framed politically. The Parliament is also more sensitive to popular concerns and sentiments than the other European institutions, which makes it a good place to study the politicization of issues such as mobility.

I compiled a dataset of parliamentary questions and answers through a simple keyword search on ‘brain drain’ at the European Parliament’s database, looking for any mentions of the term in any part of the question or answer, including both question titles and the actual body of text. I corroborated the validity of the search results by cross-checking with terms such as ‘skilled migration’ and ‘human capital flight’ – ‘brain drain’ encompassed the other terms and served as a key concept around which these debates were oriented. displays the number of questions found during each parliamentary period from 1999 onwards, clearly indicating the increasing topicality of the issue over time. The table also summarizes findings from the analysis in the form of the dominant storyline and crisis perceptions during each stage, as well as whether a brain drain from South or East European Member States was the primary concern of policymakers. I will return to the table in greater detail in the Discussion section.

Table 1. Stages of the policy debate, including crisis perceptions and storyline fit.

I imported the entire text of questions and answers into the Discourse Network Analyzer (DNA) software (Leifeld, Citation2013a). The DNA program is a qualitative content analysis tool with network export facilities. I analyzed the imported text files for statements showing the different ways brain drain was framed as a problem and the solutions offered to the problem. The problem and solution dichotomy makes sense in the question and answer format of parliamentary questions and remains sensitive to the existence of multiple interpretations. Statements were coded with the name and organization of the speaker and analyzed according to an iteratively developed coding frame comprised of 27 different frame objects presented in and .

Table 2. Problem frames – how is brain drain defined as a problem?

Table 3. Solution frames – how is brain drain framed as a solution?.

Interviews

Coding parliamentary questions is a good way to get a bird's-eye view of the political conversation around brain drain as it evolves over time. But to gain a deeper insight into how brain drain is constructed and negotiated politically, interviews with key policy actors provide more detail and a different angle of attack. provides an anonymized overview of interviewees by ranks, organizations and dates interviewed. The Commission services represented by the interviewees include the Directorate-Generals for Employment (DG EMPL – the majority of interviewees were from here); Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs (DG GROW); Communications Networks, Content & Technology (DG CONNECT); and Education and Culture (DG EAC). Interviewees were identified through desk research and referrals.

Table 4. Overview of interviewees by rank, organization and dates interviewed.

The interviews were not recorded to allow interviewees to speak more freely and at ease. Instead, I took extensive notes during the interviews and reflected on the content of each interview in field memos that were written immediately afterward. There is a balance between detailed records and more detailed off-the-record information when interviewing (Harvey, Citation2011). I opted for the latter to boost the potential for generating novel insights, and because detailed and carefully phrased records already exist in the form of parliamentary questions. Off-the-record interviews are a stronger complement to the parliamentary questions. I cite interviews in the analysis by referring to the codes given in the last column.

Analysis

I analyze the evolution of the European politics of brain drain over three stages defined with reference to the parliamentary periods given in . Stage 1 deals with the time period from 1999 to 2009 – the Prodi Commission (1999–2004) and the first Barroso Commission (2004–2009). Because there are only five questions asked about brain drain during the Prodi Commission, I merge this into Barroso I. These are the earliest questions about brain drain on record in the database, so I opt to keep them rather than discount them and just start the analysis from Barroso I. Stage 1 is also characterized by very little engagement on intra-European brain drain, focusing instead on flows of scientists and doctors entering and leaving the Union. Stage 2 runs from 2009–2014 (the second Barroso Commission). Separating Barroso, I and II allows me to more closely map the effects of the Eurozone crisis (2009–2014) on the politics of brain drain, as these periods closely map on to each other. It also provides a better balance in terms of the amount of questions analyzed in each stage. Stage 3 from 2014–2019 (the Juncker Commission) is ongoing at the time of writing, and it shows that brain drain is still topical, even though the worst of the Eurozone crisis has passed. Each stage combines data from the coding of parliamentary questions with interview data to provide a full account of the emergence and (re-)constitution of brain drain as a policy issue.

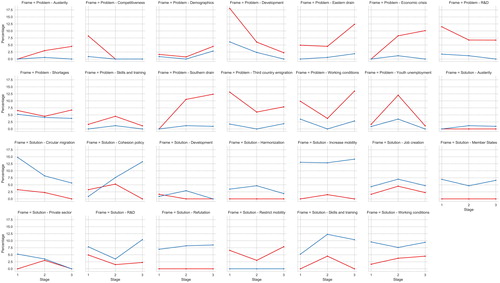

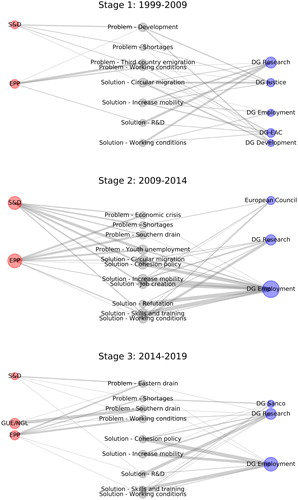

depicts the change in usage of each frame for MEPs (red lines) and Commissioners (blue lines) over each stage of the policy debate. depicts the overall evolution of the policy debate viewed as a discourse network (Leifeld, Citation2017). In , red nodes are political parties in the European Parliament (EPP = the European People's Party, S&D = Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats, GUE/NGL = European United Left/Nordic Green Left) and blue nodes represent the Directorate-General departments of the European Commission. Node size signifies degree centrality in the network and thicker edge sizes denote greater frame usage. To retain a balance between legibility and comprehensiveness, the networks in only feature the connections between the 15 most central nodes, meaning that only the most active actors during each stage are represented in the figure.

Figure 1. Change in frame usage for MEPs (red) and Commissioners (blue) over each stage of the policy debate.

Figure 2. The evolution of brain drain politics viewed as a discourse network. Red nodes are political parties in the European Parliament, blue nodes represent Directorate-General departments of the European Commission.

The analysis in general reveals two opposed storylines vying for influence in the brain drain policy debate. One is the solidarity storyline. This story goes as follows: brains are draining from the periphery to the core of the EU because of structural, macroeconomic differences between richer and poorer countries. These differences are reflected in dramatic gaps in conditions, rights and wages facing workers in the core compared with the periphery. On the basis of solidarity between EU nations, these differences should be quickly reduced by direct investment in the periphery by employer organizations, EU bodies and national governments. Social and workers’ rights should be secured at the EU-level to elevate and harmonize the conditions and status of jobs throughout the Single Market. The goal should be full employment and high-quality jobs for all. This storyline connects trade unions to center-left and leftist parties. Their economic assumptions and theories are drawn from Keynesian demand-side economics. According to this logic, temporary or limited restrictions to freedom of movement can be legitimate if they serve to rebalance EU Member States and ensure solidarity. The main frames that make up this storyline are the problem codes ‘austerity’, ‘economic crisis’, ‘shortages’ and ‘working conditions’ as well as the solution codes ‘cohesion policy’, ‘job creation’ and ‘working conditions’.

In contrast to the solidarity storyline, we find the skills storyline. The skills story is different: here, brains are draining from the periphery to the core because of skills mismatches. The problem is not so much macroeconomic differences as differences in the employability of workers and the demands of national labor markets. This storyline argues that countries that have good vocational and educational training (VET) systems also have low unemployment. Consequently, to fix high unemployment, you should fix VET systems and encourage workers to train or re-train to gain the skills needed by employers, which are typically summarized as more practical, on-the-job training, skills in information and communication technologies (ICT), entrepreneurial and organizational skills, language skills and skills in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM). This storyline connects business and employer organizations to center-right politicians and fiscal conservatives. Their economic assumptions and theories are drawn from neoliberal supply-side economics. Freedom of movement is completely integral to this line of thinking – labor should be free to collect its highest reward. The main frames that make up this storyline are the problem codes ‘R&D’, ‘skills and training’ and ‘third country emigration’ as well as the solution codes ‘circular migration’, ‘increase mobility’, ‘R&D’ and ‘skills and training’.

The picture is not black and white, and almost no policy actors would argue that there is no truth at all to their opponents’ storyline, but it is clear that there are strategic emphases placed on one or the other story. The question for the analysis is how these storylines develop over the stages of the policy debate as they encounter shifting crisis perceptions.

Stage 1: 1999–2009

Because most of the interaction in Stage 1 is over a decade old, the analysis of this stage relies primarily on the parliamentary questions rather than interviews. Content analysis of the parliamentary questions revealed that most discussion in this period dealt with brains entering and exiting the Union rather than intra-European flows. Because I am primarily interested in the intra-European politics of brain drain, I will be brief on this stage and move swiftly to Stage 2. Nonetheless, Stage 1 still tells us something about the emergence of brain drain as a policy issue and how it becomes constituted in connection to two opposing frames of reference.

The most central nodes in the discourse network during this period were the ‘Development’ and ‘Third country emigration’ nodes. Where the ‘Development' node reflects concern with the EU draining brains (especially African doctors) from developing countries to the Single Market, the ‘Third country emigration' node reflects concern with drains from the Single Market to other countries, primarily the United States (U.S.). This means that neither of the two most frequently asked questions in Stage 1 concerned intra-EU brain drain, which is surprising given that the period covers the years immediately following the 2004 enlargement. On the Commission side, the discourse is dominated by DG Research, urging countries to increase spending on research and development (R&D) to retain scientists.

There are only three mentions of an Eastern brain drain in Stage 1 (Parliamentary Questions E-0264/05, E-3941/06 and H-0700/06), and all are commenting on the potential risks of large scale emigration of skilled workers as the transitional border control measures are eased out following the 2004 enlargement. It is still too early at this stage to see any political repercussions of an Eastern drain, even if workers have already started moving.

There is an illuminating exchange between Ján Figel, Commissioner for Education, Training & Culture and MEP Justas Vincas Paleckis (PES) (H-0700/06). Paleckis wants to know whether the Commission will consider establishing a special fund to compensate new Member States that are sending specialists and qualified workers to the old Member States. Figel's response shows the split in Commission thinking that will come to define the European politics of brain drain in future years. After reasserting the sanctity of free movement, he makes two points: first, Eastern workers often stay for a limited time only, send remittances and return home with new skills – this is the circular migration argument mobilized within the skills storyline, or alternatively, the ‘diaspora option’ (Pellerin & Mullings, Citation2013; Phillips, Citation2009). Second, although some workers are draining from East to West, highly educated workers in the West are also leaving for the U.S. due to wage differentials: ‘The problem of brain-drain, insofar as it exists, seems more linked to the salary differential between the country of origin and destination countries than to the quality of the education systems in migrants’ countries of origin'. The answer to this problem, he says, lies in the good use of structural funds to ensure growth, job creation and convergence to eradicate wage differences (the solidarity storyline).

These two answers imply contradictory logics of action: circular migration implies doing nothing (because brain drain is not perceived as an actual problem – it is offset by remittances and upskilled, return migration), but wage differentials imply using structural funds to invest (because the EU should avoid losing highly educated workers to the U.S. and should spend money to reduce the risk of this). The first of these coheres with the skills storyline, the second with solidarity. In response to questions about brain drain from developing countries outside the EU, the most frequent solution also follows a circular migration framing (see DG Development node in ). The movement of Eastern workers (and African doctors) becomes naturalized and desirable, while the movement of Western workers becomes problematized. The key difference is that Western workers are leaving the EU, while Eastern workers are moving to another Member State. But we could have just as easily imagined a skills-based or circular migration framing of the movement of Western workers, where they would be expected to return to the EU with new skills and networks that could be of benefit to the economies of the Western Member States.

The use of both framings in the answer by Ján Figel is also an indication that policy actors and organizations can easily communicate both storylines to reflect the complexity of the issue, to avoid taking strong stances, or to partition the problem into segments where doing either one or the other is better. Storylines create strategic opportunities, in short. The solutions to the problems of brains entering and exiting the Union are mirrored in the approach to intra-EU drain, where they exist side-by-side but with no clear preference, yet, for one or the other. Their juxtaposition creates a space of opportunities for EU action that spans laissez-faire to interventionist policies, meaning that the process of problematization is still open and ongoing.

Stage 2: 2009–2014

The second stage begins with the Barroso II Commission in 2009. The enlargement is 5 years in the past and the financial crisis, soon to become the Eurozone debt crisis, is unfolding.

Compared with Stage 1, the picture has changed completely. Considerations of brains entering or exiting the Union are relegated to the periphery – this is apparent in charting the sharp decrease in the importance of the ‘Development’ and ‘Third country emigration’ frames over time. Everything now is about youth unemployment in Europe. The crisis has struck. We can observe a strong similarity in the discourse of both main parliamentary groupings (S&D and EPP) in . In addition to youth unemployment, they frequently raise the problem of the economic crisis and drains from Southern Europe to the North. During Stage 2, there is a clear understanding in the Parliament that brain drain primarily has to do with the flight of highly educated young people from Southern to Northern Europe as a consequence of high unemployment caused by the crisis. The Eastern drain is a more peripheral issue in the policy debate during this stage, as can be seen in .

In terms of solutions, the MEPs show no clear preference for any one particular treatment and the menu of remedies spans job creation, skills and training, working conditions and cohesion policy – although the S&D show much higher preference for cohesion policy compared with the EPP, as would be expected. The dynamic is mostly one of asking the Commission what they intend to do about the mounting problems. The split between cohesion policy as a solution on one hand and skills and training on the other echoes the division identified in Stage 1 between circular migration and investment, or between skills and solidarity. Both of these divisions differ in where they place the burden for addressing the identified challenges: either it is a question about the supply of labor or the demand for labor. According to the skills storyline, training and circulation imply that when workers are skilled and mobile, labor will reallocate itself and the crisis will pass. But the arguments concerning cohesion policy or investment in R&D or in the health systems of developing countries follow a contradictory logic. Here it is a question about the demand side, solidarity and addressing structural differences in economies through intervention and investment.

Looking at , we find this division mirrored in Commission/Council responses, but with a preference leaning toward the skills storyline: in , we can observe the dominance of the ‘Increase mobility' and ‘Skills and training' frames. Especially the solution frame ‘Skills and training’ exhibits a dramatic increase during Stage 2 compared with Stage 1. We can also observe an increase in ‘Solution – Cohesion policy’, but by examining , it becomes apparent that this discourse is mostly coming from DG Employment. Interview data reveals that political and organizational weight (DG for Economic and Financial Affairs – ‘Ecfin’) was aligned behind the skills storyline.Footnote1

The mobility argument in Stage 2 is that labor shortages, unemployment and mismatches can be alleviated by encouraging people to move to a different Member State, meaning encouraging the movement from the high-unemployment South to the low-unemployment North. One of the tools for doing so is EURES, the European Job Mobility Portal, which is a network between the Commission and the public employment services of the Member States for matching jobseekers and employers across national boundaries. Especially the 2012 initiative ‘Your First EURES Job' was specifically targeted toward young people as a response to the youth unemployment crisis. Labor mobility was seen as an ‘adjustment mechanism' to alleviate economic shocks, and for substantial parts of the Commission it was understood to be a win-win proposition for both the South and North.Footnote2

The mobility argument places the burden for addressing unemployment squarely on the shoulders of the unemployed, and this is bolstered by the ‘Skills and training' argument. Part of the ‘Skills and training' arguments were directly connected to increasing mobility, for example, by using the Skills Panorama to identify skills mismatches and using the Professional Qualifications Directive to ensure cross-border recognition of skills (see Commissioner for Employment László Andor's responses to Written Question E-006509/12). Transitions from school-to-work were also a central topic, partly through aligning education systems with labor market needs and developing practical training in companies (traineeships). The increasing relevance of the ‘Job creation' node is explained by the Youth Guarantee program, which is a logical extrapolation of the emphasis on skills and training. The Guarantee was a commitment by all Member States to provide all youth under the age of 25 an offer of a job, continued education, apprenticeship, or traineeship within four months of becoming unemployed or leaving formal education. It was funded by Member States and topped up by the European Social Fund and €6 billion Youth Unemployment Initiative.

On the surface, the Youth Guarantee shows how the strict separation between the skills and solidarity storylines breaks down in complex policy environments where compromise, consensus and working solutions are quickly needed. While the Guarantee is partly addressed at boosting the employability of workers, it is backed by cohesion policy funding to stimulate the crisis-stricken economies and create jobs. But when looking into the arguments covered by the ‘Cohesion policy' node, nearly all of them concern the use of structural funds to reform and invest in national education and training systems and ease the transition of youth into labor markets. It is hard to read this as anything other than a continuation of the employability, supply-side logic that would see the crisis overcome by making youth more skilled and mobile.

Interview data strongly supports the notion that the solution to unemployment during the crisis years was characterized by a consensus on using mobility to alleviate the shock, and the risks of brain drain were secondary to the more urgent demands of the fast-burning youth unemployment crisis.Footnote3 The immediate challenges facing the EU were to reduce unemployment levels and ensure fiscal stability in the South: mobility contributed to solving both of those problems, and the expectation was that circular and return migration would upgrade human capital and productivity in the South after the crisis passed. In this manner, the skills storyline de-problematized brain drain by transforming labor mobility from a potential risk into a solution. Where we should have expected fast-thinking, emotionally charged responses that directly addressed the solidarity concerns of Southern Member States and recognized the risk of brain drain, instead we see the deliberate pursuit of a skills and mobility agenda that is better characterized as slow-thinking for its emphasis on the rational reallocation of labor and reform of national VET systems. Brain drain was consequently erased as a policy problem through the skills storyline.

Politically, the skills storyline was attractive for many reasons. It enabled the construction of a center-right consensus that rested on neoliberal economics and the theory of optimal currency areas.Footnote4 Some interviewees referred to the idea of using labor mobility to alleviate economic shocks as ‘textbook economics', which suggests the hegemony of this line of thinking.Footnote5 The storyline positioned labor mobility as a ‘hinge issue’ that aligned professional economic consensus with the policy process (Farrell & Quiggin, Citation2017). Although parts of DG Employment and center-left parties voiced their concerns over relying too much on the mobility solution and the resulting risks of brain drain, the solidarity storyline did not offer a problematization that was as effective in erasing policy problems or easing coordination. Instead, the solidarity storyline framed brain drain as a risk that would offset the short-term benefits of reallocating labor from the South to the North.

Stage 3: 2014–2019

In Stage 3, we have put the worst of the crisis years behind us, but the EU has not emerged entirely unscathed. Following the 2016 Brexit vote, labor mobility has only become increasingly contentious. According to many interviewees, it is in these recent years that brain drain has featured most intensely in debates and communications between the EU institutions – something corroborated by the increasing number of parliamentary questions bringing up the issue. Brain drain is just one aspect of labor mobility's ‘dark side'; other sides include welfare tourism, welfare chauvinism, and social dumping, topics that are the mirror image of brain drain reflected in the receiving countries. The ascendance of these issues alongside the Brexit vote suggests that the taboo of questioning the win-win proposition of labor mobility has been broken in the EU.

shows a changing picture in Stage 3 compared with the earlier stages. We can discern two different sets of interlinked nodes representing two different discourses, where separation between the Eastern and Southern drains indicate different sets of connected problems and solutions. The discourse connecting the Southern drain is a continuation of the discussion observed during Stage 2, but now with less emphasis on youth and more emphasis on questioning the austerity remedy. Southern MEPs were in no position to challenge austerity earlier, but now the consensus is eroding – in part driven by renewed dissensus between Keynesians and pro-austerity economists (Ban, Citation2015; Blyth, Citation2015; Farrell & Quiggin, Citation2017). The discourse connecting the Eastern drain shows that it is only recently that Eastern Europe has gotten more vocal in calling attention to the negative externalities of labor mobility.

We can also observe that the Southern and Eastern drains are understood as distinct problems in MEP discourse: the Southern one as exacerbated by the economic crisis and austerity and the Eastern one as driven by the gap in wages and working conditions. Labor shortages are also more frequently identified in the East, particularly in the area of health. Problems of R&D spending and demographics are connected to both the East and the South, but demographics are more frequently mentioned in connection to the Southern drain. After the immediate shock of the crisis years, MEPs are now looking further into the future and concerning themselves with questions of long-term sustainability and convergence. As perceptions shift from fast-burning to slow-burning crises, the solidarity storyline emerges as a prominent framing of the Eastern drain.

When we look at Commission/Council responses, a continuation in thinking from the second Barroso Commission to the Juncker Commission can be identified. The calls to increase European labor mobility remain the most dominant argument, and this node is tightly interlinked through DG Employment discourse with the ‘Cohesion policy' and ‘Skills and training' nodes. But cohesion policy has gained much in prominence, while the skills frame has tapered off somewhat, as evidenced in . However, when looking into the content of cohesion policy arguments, we find that they are still oriented toward employability and skills. For example, Commissioner for Research Carlos Moedas, in answers to written questions in 2015,Footnote6 notes that cohesion policy funds are being used by several Member States to fund doctoral training programs. Commissioner for Employment Marianne Thyssen, in her answers to other written questions in 2015,Footnote7 also notes that cohesion policy funds support investments in education, training and school-to-work transitions. Brain drain is clearly constituted in terms of supply-side employability policies. The framing of cohesion policy here does not imply a solidarity storyline.

This makes it unsurprising that the first official policy action to address intra-EU brain drain finds its home within the New Skills Agenda for Europe (European Commission, Citation2016a). The Skills Agenda contains ten actions aimed at upgrading European human capital in support of employability, growth and competitiveness. The actions include such initiatives as a Skills Guarantee, a review of the European Qualifications Framework and a ‘Digital Skills and Jobs Coalition'. On the topic of brain drain, the Communication announcing the Agenda notes that ‘better local interaction between education and training on the one hand and the labor market on the other, supported by targeted investment, can also limit brain drain and help develop, retain and attract the talent needed in specific regions and industries' (European Commission, Citation2016a, p. 11). Action 8 in the Communication proposes a further analysis of the issue of brain drain and the sharing of best practices as regards effective ways of tackling the problem.

In the current political climate, brain drain has become entirely subsumed to the question of skills and skills mismatches in particular. According to the Skills Agenda, mismatches in skills are one of the main obstacles in the way of European employability, competitiveness and growth: ‘Skills gaps and mismatches are striking. Many people work in jobs that do not match their talents. At the same time, 40% of European employers have difficulty finding people with the skills they need to grow and innovate' (European Commission, Citation2016a, p. 2). The connection to brain drain is that a closer link between education systems and the labor market will ensure that graduates quickly find a job. The argument is a clear echo of the skills storyline. We can also find this argument in the 2015 version of the Employment and Social Developments in Europe report: ‘In addition to global competitive challenges, future EU growth will be under greater pressure due to the steady decline of the working-age population in most EU Member States, which may combine or exacerbate skills mismatch in regional labor markets, often resulting in brain drain' (European Commission, Citation2016b, p. 14).

Interviewees also confirmed the importance of executive politics (Lodge & Wegrich, Citation2012) and political entrepreneurship (Parsons, Citation2003) in placing brain drain on to the Commission’s work program. Emigration and brain drain are the most important political topics in Lithuania and Latvia,Footnote8 and Valdis Dombrovskis, the current Latvian Commission Vice-President for the Euro and Social Dialogue, was instrumental in bringing attention to this at the highest level.Footnote9 That it was inserted into the Skills Agenda rather than some other policy suggests the lasting influence of the skills storyline after it came to prominence during the crisis years. The analysis demonstrates that the capacity of the skills storyline to address key concerns raised through fast-burning crisis perceptions has stabilized the narrative and ensured its continuing relevance in the post-crisis stage. However, the solidarity storyline is beginning to challenge the assumptions of the skills framing, now that the crisis is perceived as slow-burning and attention is shifting toward the East.

Discussion

The period under observation in the study was marked by shifting perceptions of the intensity and rhythm of crisis situations impacting European political economy. Against this background, the movement of labor was variously framed according to different storylines. The skills storyline naturalized the movement of labor; the solidarity storyline problematized it. The relative dominance of each of these storylines varied according to changing crisis perceptions: during Stage 1, the groundwork for each of the storylines was established with reference to how to frame the problem of brains entering and exiting the Single Market. During Stage 2, which was characterized by perceptions of an acute, fast-burning crisis, the highly intense Southern drain moved into the foreground. Dramatic increases in youth unemployment and emigration from the South led to highly salient and emotionally charged discussions, especially in the European Parliament. Here, the skills storyline ascended by providing a frame of reference that re-constituted this movement of labor as part of a solution to the Eurozone crisis instead of a problem created by the crisis. During Stage 3, the Southern drain became less relevant, but the intensity of the Eastern one increased, especially due to high-level political attention to the issue from vocal East European members of the Juncker Commission. Although the tempo of crisis perceptions has decreased and the solidarity storyline gained strength, it could not supplant the skills storyline.

This means that the problem with European brain drain politics today is that fixes established at a time of fast-burning crisis (during Stage 2) are now dominating the discussion of a slow-burning crisis (during Stage 3), closing down certain interpretations and policy options or re-imagining the use and purpose of different instruments. Although the solidarity storyline is becoming more prominent in MEP discourse during Stage 3, Commission responses subsume solidarity to a skills-based, employability logic, for example when arguing for the use of structural funds to address skills mismatches. This use of cohesion policy frames to support the skills storyline reveals that individual frames do not neatly fit either one or the other storyline at all times, which is why it is important to look at bundles of frames and the larger storylines they feed into. The meaning of frames varies over time as their position and connections in discourse networks change – this is a challenge to forms of research that assume stable meanings of frames.

One key question requires an answer: why is the skills storyline still dominant today? In MEP questions and in interview data, there is a much clearer separation now between the causes of the Eastern and Southern drains: the Eastern one being seen as differences in wages and working conditions, the Southern one as connected to the economic crisis and austerity. But the responses from the Commission and Council still display a clear preference for the skills storyline today. The answer to this puzzle is that the skills storyline, after serving immediate and urgent political needs during Stage 2 by re-constituting the risk of brain drain from the South as a complementary part of the response to the Eurozone crisis, has now become increasingly institutionalized within the Commission. Problems concerning brain drain are immediately met by references to skills mismatches and the necessity of reforming of national VET and education systems. The act of writing brain drain into the Skills Agenda is an example of this.

Additionally, the skills storyline served key purposes for other parts of the Commission and European policy environment. With the growing emphasis within the EU on innovation, for example through the Innovation Union and Industry 4.0 initiatives, skills serve as a focal point and silver bullet to a growing portfolio of issues. Storylines that can ‘do more’ by showing ‘generosity’ and applicability to connected institutional concerns have more power than those that are more restrictive or narrow (Eyal, Citation2013). Another example of the strategic potential of the skills storyline is that by focusing on national systems of VET, brain drain becomes ‘nationalized’ and understood as a problem that is generated and treated on the domestic level of Member States, not at the European level. In this manner, the Commission can exert strategic influence over which problems demand EU-level attention, thereby managing their work load, priorities and political pressure.

We may note the congruence of the skills storyline with the interests of employer organizationsFootnote10 and centre-right parties on the one hand and the congruence of the solidarity storyline with the trade unions and centre-left parties on the other.Footnote11 This is to be expected. But Commission staff, even within the same DG, fell both ways on the issue, depending on political preference or economic assumptions, some agreeing with the skills storylineFootnote12 and others saying that the impact of the Skills Agenda on brain drain would be negligible at best and highly uncertain.Footnote13 Country of origin (sending or receiving) of officials could not predict adherence to a skills or solidarity storyline. Several interviewees within DG Employment mentioned that there were two schools of thought, or that the service was ‘walking on two different legs’: mobility or cohesion, corresponding to the skills or solidarity storylines.Footnote14 These storylines do not have to be mutually exclusive, but in the policy imagination and default mindset of interviewees, work often proceeded from an assumption of one or the other and overlaps or complementarities between cohesion and mobility policy are seldom sought. As perceptions of a fast-burning crisis recede, there should be greater possibility for DG Employment and the rest of the Commission to engage with these contradictory logics as the solidarity storyline comes forward.

The account challenges conventional wisdom that periods characterized by perceptions of a fast-burning crisis should favor ‘hot knowledge’, heuristics that can be straightforwardly applied, and emotional responses whereas slow-burning periods provide a greater space for rational deliberation and expert knowledge (Seabrooke & Tsingou, Citation2019; Tsingou, Citation2014; Widmaier, Citation2016). The parliamentary questions raised by MEPs do contain several such ‘hot’, emotional responses, but only in their problem definition – when it comes to the solutions proposed by either MEPs or Commissioners, we do not get very far with the fast-thinking versus slow-thinking typology. Instead, by looking at how the two storylines respectively problematize brain drain in relation to the crisis, we can better understand their appeal to policy actors and their potential to structure the debate. The skills storyline was dominant because it erased the risk of brain drain as a problem whatsoever, and actually re-constituted the large-scale movement of labor from the South to the North as something desirable and a fix to the crisis. The solidarity storyline, on the other hand, problematized this labor flow as a potential brain drain that did nothing to quell the crisis, but only exacerbated existing imbalances. The power of the storylines to orient policy has nothing to do with their fast-thinking or slow-thinking properties. The storylines construct both the pace of the crisis and the place of labor mobility within it. This means that we have to pay better attention to how storylines frame policy problems in ways that allow involved actors to build coalitions that can overcome crisis-induced coordination problems.

We would also expect that as perceptions changed toward a more slow-burning crisis, we would see greater deliberation and expert knowledge opening up an even broader menu of policy alternatives. Instead, it was surprising to see the entrenchment of the skills narrative, even in the face of a growing challenge from the solidarity storyline. This was not so much an example of ‘cool’ and rational deliberation as an example of doubling down and closing off alternative viewpoints – something we would generally expect during fast-burning crises, not slow-burning ones. The enduring relevance of the skills storyline demonstrates the potential for successful storylines to institutionalize by entrenching ideas and actor positions in a manner that gives them priority over contending storylines at later points in time. Storylines are always embedded in broader structures of discourse (Hajer, Citation1997), and storylines that become institutionalized shift these structures in ways that make them more amenable to the frames communicated by the storyline.

Coman (Citation2018), in her analysis of the 2013 structural funds reform, finds that changes in crisis perceptions also interacted with changing power relations between EU institutions and changes in the ideational structure of prevailing discourse (see also: Coman, Citation2017). Also drawing on the fast- versus slow-burning distinction, she argues that the Parliament was sidelined during the fast-burning years by a strong partnership between the Council and Commission, but as perceptions changed toward slower-burning crises, the Council in turn became sidelined by a growing partnership between the Parliament and the Commission. Even within the Commission, DG Ecfin was empowered to the detriment of DGs working with regional policy and structural funds. In addition, there was a powerful ideological consensus during the fast-burning years on the need to increase fiscal and budgetary discipline.

Coman’s analysis raises the question of alternative explanations to the case study I present. In particular, to what extent might the emphasis on skills be explained purely by the interests of more powerful actors such as DG Ecfin, employer organizations and Northern Member States? The observations that she makes in her study are in accordance with my own analysis, but I argue that the changes in power relations are the outcome of framing processes, not their cause. The skills storyline provided a problematization of brain drain that made it possible to build a coalition (or at least to coordinate expectations) between powerful policy actors. Coalitions have to rest on something more than purely material considerations – storylines provide the social context that aligns expectations about what the nature of a given policy problem is and what kinds of solutions are deemed appropriate. In this manner, storylines precede material interests by providing actors with the reasons for why their material interests are what they are (see also Woll, Citation2008). Having said that, I have chosen to focus on storylines and crisis perceptions to advance debates on agent-centered constructivism in IPE, but the analysis presented here is compatible with and would be enriched by a further consideration of the material resources and interests of the involved policy actors.

Conclusion

All in all, the article demonstrates that the intersection between storylines and crisis situations produces insights into the emergence and constitution of new policy areas. The form of analysis employed here is best suited for policy issues that are controversial, uncertain and open-ended (to allow multiple storylines to emerge and clash) and where the duration of analysis allows for changes in the pace and rhythm of institutional life. A limitation of the approach is that the requirements for both quantity and quality of data are very high. Studying storylines can also detract attention from changing distributions in resources and shifts in coalitional strength, although I argue that these may be seen as outcomes of changes in framing processes, and not their cause. The storyline approach can produce telling insights into the reasons and beliefs underlying executive action, which is particularly useful during times of crisis (Lodge & Wegrich, Citation2012).

In terms of theory, the study challenges conventional wisdom that fast-burning crises are associated with ‘hot’ knowledge and slow-burning crises with ‘cool’ knowledge (Seabrooke & Tsingou, Citation2019; Widmaier, Citation2016). At the height of the crisis, we should expect the emotional appeals and solutions mobilized through the solidarity storyline to trump the more technical calculations of efficiently reallocating skilled labor. As the crisis cools down, we should expect greater scope for deliberation and expertise. The case study that I presented challenged both of these expectations. The key theoretical contribution I make is to argue that the relation between storylines and perceptions of crisis has to be made the object of scrutiny rather than assumed to be one thing or another. In other words, the relation is contingent on the content of storylines (in terms of frame objects and the problematizations they present) and how they fit into the broader network of discourse of a given policy debate.

Empirically, the study contributes by providing a method for identifying and mapping these storylines, as well as charting them over time. Using a qualitative multi-method approach (Lamont & Swidler, Citation2014) comprised of a content analysis of Parliamentary Questions in connection with interviews is a robust way to get a sense of the development and relative strength of storylines. Mapping these debates as discourse networks (Leifeld, Citation2017) lets us intuitively visualize changes in discursive structure over time. This method can be applied to other areas of international political economy marked by contentious policy debates.

In terms of practical implications, it is clear that precision and clarity is required in European discussions of brain drain as to the geography of the drain, the tempo and intensity with which it is perceived and the storyline through which it is understood. The analysis here identified several ways in which each of these could vary and the resultant constraints produced on policymaking. These constraints are caused by framing processes and are therefore open to contestation. We should encourage policymakers and publics to question these narratives and make conscious choices rather than reproduce dominant storylines, which can have the effect of closing down certain interpretations and the space of imagined solutions (Cross & Ma, Citation2015).

Following on from this point, an implication is to consider what is lost by framing brain drain as skills mismatch. The assumption that more or better education or training will help potential migrants find work in their home countries seems to be contradicted by the statistical conclusion that most Eastern European migrants are already overqualified for the work they carry out abroad (Galgoczi, Leschke, & Watt, Citation2009). Increased schooling does tend to help individuals find better work, but the belief that every labor problem on a societal level can be solved by increased schooling has been strongly questioned – Grubb and Lazerson (Citation2004) refer to the blind faith in this idea as the ‘education gospel’. The same criticism can be leveled at the ideas of brain circulation and upskilling, which have received attention in IPE as development strategies (Pellerin & Mullings, Citation2013; Phillips, Citation2009; Saxenian, Citation2007) – the analysis here suggests that these strategies also risk displacing more difficult but necessary structural interventions or investments. Aside from this, the Skills Agenda, by emphasizing technical and digital skills, risks missing the potential opportunities in devoting more attention and resources to emotional labor and care work, an area where robots and algorithms will struggle to replace human workers (Gershon, Citation2017). What the dominance of the skills storyline means for the transnational reorganization of care chains (Yeates, Citation2009) and social reproduction (LeBaron, Citation2010) is an open question demanding further research. As taboos about the ‘dark sides of mobility’ are being broken in the EU and elsewhere, increased attention to storylines can help us untangle the rules and politics of this increasingly contentious issue.

Notes on contributors

Jacob A. Hasselbalch is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Department of Political Science, Lund University. His research interests are in the political economy of governance, regulation and technology. Besides brain drain, Jacob has worked on hydraulic fracturing, electronic cigarettes and is currently working on plastics. His research has been published in the Journal of European Public Policy and the Journal of Professions and Organization.

Acknowledgments

For comments on earlier drafts of the article, the author would like to thank László Andor, Cornel Ban, Mads Dagnis Jensen, Matthias Kranke, Janine Leschke, Leonard Seabrooke, Eleni Tsingou and Duncan Wigan.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Data availability statement

The data and code for producing the figures in the manuscript is available online at https://osf.io/w4vt8 in the form of an interactive Python notebook.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Interview E3.

2 Interviews E3, E5 and E6.

3 Interview E1, E3, E6 and P1.

4 Interview E3 and P1.

5 Interview E6 and E11.

6 Written Questions E-010225/15 and E-003247/15.

7 Written Questions E-001947/15, E-008851/15 and E-015052/2015.

8 Interview E9.

9 Interview E1, E9 and E10.

10 Interview B1, B2, B3 and B4.

11 Interview U1, U2, U3, U4 and U5.

12 Interview E2, E5 and E7

13 Interview E1, E4, E6, E9 and E10

14 Interview E3, E4 and E11

References

- Atoyan, R., Christiansen, L., Dizioli, A., Ebeke, C., Ilahi, N., Ilyina, A., … Zakharova, D. (2016). Emigration and Its Economic Impact on Eastern Europe (IMF Staff Discussion Note No. 16/07). Washington, DC. Retrieved from https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/sdn/2016/sdn1607.pdf doi: 10.5089/9781475576368.006

- Auel, K., & Raunio, T. (2014). Introduction: connecting with the electorate? Parliamentary communication in EU affairs. The Journal of Legislative Studies, 20(1), 1–12. doi: 10.1080/13572334.2013.871481

- Bacchi, C. (2012). Why study problematizations? Making politics visible. Open Journal of Political Science, 02(01), 1–8. doi: 10.4236/ojps.2012.21001

- Ban, C. (2015). Austerity versus stimulus? Understanding fiscal policy change at the international monetary fund since the great recession. Governance: An International Journal of Policy, Administration and Institutions, 28(2), 167–183. doi: 10.1111/gove.12099

- Ban, C. (2016). Ruling ideas: How global neoliberalism goes local. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ban, C., Seabrooke, L., & Freitas, S. (2016). Grey matter in shadow banking: international organizations and expert strategies in global financial governance. Review of International Political Economy, 23(6), 1001–1033. doi: 10.1080/09692290.2016.1235599

- Barslund, M., & Busse, M. (2016). Labour Mobility in the EU. Addressing challenges and ensuring “fair mobility.” Centre for European Policy Studies, Brussels. Retrieved from https://www.ceps.eu/ceps-publications/labour-mobility-eu-addressing-challenges-and-ensuring-fair-mobility/

- Beine, M., Docquier, F., & Rapoport, H. (2008). Brain drain and human capital formation in developing countries: winners and losers. The Economic Journal, 118(528), 631–652. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0297.2008.02135.x

- Best, J. (2008). Ambiguity, uncertainty, and risk: rethinking indeterminacy. International Political Sociology, 2(4), 355–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-5687.2008.00056.x

- Best, J. (2012). Bureaucratic ambiguity. Economy and Society, 41(1), 84–106. doi: 10.1080/03085147.2011.637333

- Blyth, M. (2002). Great transformations: economic ideas and institutional change in the twentieth century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Blyth, M. (2015). Austerity: The history of a dangerous idea. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (1990). The logic of practice. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Cañibano, C., & Woolley, R. (2015). Towards a socio-economics of the brain drain and distributed human capital. International Migration, 53(1), 115–130. doi: 10.1111/imig.12020

- Coman, R. (2017). Values and power conflicts in framing borders and borderlands: the 2013 reform of EU Schengen governance. Journal of Borderlands Studies, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/08865655.2017.1402201

- Coman, R. (2018). How have EU “fire-fighters” sought to douse the flames of the eurozone’s fast- and slow-burning crises? The 2013 structural funds reform. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 20(3), 540–554. doi: 10.1177/1369148118768188

- Cross, M. K. D., & Ma, X. (2015). EU crises and integrational panic: the role of the media. Journal of European Public Policy, 22(8), 1053–1070. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2014.984748

- Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

- European Commission. (2016a). COM(2016) 381: a new skills agenda for Europe. Working together to strengthen human capital, employability and competitiveness. Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=15621&langId=en

- European Commission. (2016b). Employment and Social Developments in Europe 2015. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. https://doi.org/10.2767/950897

- Eyal, G. (2013). For a sociology of expertise: the social origins of the autism epidemic. American Journal of Sociology, 118(4), 863–907. doi: 10.1086/668448

- Farrell, H., & Quiggin, J. (2017). Consensus, dissensus, and economic ideas: economic crisis and the rise and fall of Keynesianism. International Studies Quarterly, 61(2), 269–283. doi: 10.1093/isq/sqx010

- Finnemore, M., & Sikkink, K. (1998). International norm dynamics and political change. International Organization, 52(4), 887–917. doi: 10.1162/002081898550789

- Fisher, D. R., Waggle, J., & Leifeld, P. (2013). Where does political polarization come from? Locating polarization within the U.S. climate change debate. American Behavioral Scientist, 57(1), 70–92. doi: 10.1177/0002764212463360

- Galgoczi, B., Leschke, J., & Watt, A. (Eds.). (2009). EU Labour Migration since Enlargement: Trends, Impacts and Policies. Surrey & Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing Ltd.

- Galgóczi, B., Leschke, J., & Watt, A. (Eds.). (2012). EU Labour Migration in Troubled Times: Skills Mismatch, Return and Policy Responses. Surrey & Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing Ltd.

- Gerring, J., & Cojocaru, L. (2016). Selecting cases for intensive analysis. Sociological Methods & Research, 45(3), 392–423. doi: 10.1177/0049124116631692

- Gershon, L. (2017). The key to jobs in the future is not college but compassion. Retrieved from https://aeon.co/essays/the-key-to-jobs-in-the-future-is-not-college-but-compassion

- Goffman, E. (1974). Frame analysis: An essay on the organization of experience. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Graham, B. A. T. (2014). Diaspora-owned firms and social responsibility. Review of International Political Economy, 21(2), 432–466. doi: 10.1080/09692290.2012.747103

- Grubb, W. N., & Lazerson, M. (2004). The education gospel: The economic power of schooling. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Hajer, M. A. (1997). The politics of environmental discourse: Ecological modernization and the policy process. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Harvey, W. S. (2011). Strategies for conducting elite interviews. Qualitative Research, 11(4), 431–441. doi: 10.1177/1468794111404329

- Hobolt, S. B. (2016). The Brexit vote: a divided nation, a divided continent. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(9), 1259–1277. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2016.1225785

- Hoffman, A. J., & Ventresca, M. J. (1999). The institutional framing of policy debates: Economics versus the environment. American Behavioral Scientist, 42(8), 1368–1392. doi: 10.1177/00027649921954903

- Hülsse, R. (2007). Creating demand for global governance: The making of a global money-laundering problem. Global Society, 21(2), 154–178. doi: 10.1080/13600820701201731.