Abstract

Due to its focus on high tech sectors and the role played by FDI, the literature dealing with developmental opportunities in Central and Eastern European (CEE) economies underestimates the room for domestic developmental agency. In this paper, we contrast diverging strategies of positioning the Polish and Hungarian dairy sector in European markets. In Hungary, ‘outsourcing’ the integration of fragmented producers to multinational corporations (MNCs) led to competitive downgrading, providing a fertile terrain for economic nationalism in the wake of the financial crisis. In Poland, a developmental alliance between state and farmers upgraded the competitiveness of domestic cooperatives under the constraint of EU accession. Contrary to narratives that describe passive competition states in CEE, we show that the domestic politics of developmental alliances determined whether EU integration resulted in the neoliberal outsourcing of development to MNCs or gave rise to a sector-level developmental state. Using the notion of dynamic institutional complementarity, we explore why lesser-developed countries with similar initial conditions diverge in developmental strategies and outcomes within the same transnational integration regime that imposes the same rules and provides the same opportunities to member states.

1. Introduction

Central Eastern Europe (CEE) has functioned as a laboratory for the political economy of transnationalization as the region received major FDI inflows from EU15 countries between the pre-accession phase of the 1990s and the great recession of the 2010s (Medve Bálint, Citation2014). Students of semi-peripheral capitalism studied capital- and technology-dependent high-tech (HT) manufacturing sectors in the Visegrad 4 countries (Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia) as strategic cases for theorizing a dependent variety of capitalism in CEE (Nolke & Vliegenhart, Citation2009).

While we do not question the need to explore developmental opportunities in HT sectors, in this paper we call for a deeper exploration of low and medium tech (LMT)1 manufacturing sectors as politicized sites of social and economic upgrading to explore the room for industrial policy and understand the role of transnational integration regimes (TIR) in shaping developmental opportunities (on TIRs see Bruszt & Langbein, Citation2014).

Although the high-tech share of exports is considered an indicator of economic development, most HT sectors accumulate trade deficits in CEE (Bruszt, Lundsted and Munkacsi, in this issue), typically using low skilled workers and assembling imported intermediaries, which Robert Wade calls ‘import intensive deficit-prone industrialization’ (Wade, Citation2010). Sectors listed in LMT represent the bulk of manufacturing industries in these countries (Kaloudis, Sandven, & Smith, Citation2005), with production segments that require HT inputs (such as biotechnology) and/or using highly skilled labor (in R&D, marketing, production of pesticides). This conjunction might increase domestic value added at least as much or more than firms in proper HT sectors. If R&D expenditure in relation to output is the measure of technology content, then a country with high domestic value-added content in LMT sectors might be better off than a country with a high ratio of HT sector with low domestic value-added content. In a world of GVCs, ‘tasks’ or ‘activities’ matter more than products: having high domestic value-added in LMT sectors may be better than being stuck in low value-added, assembly-type manufacturing in a HT sector.

Focusing on a LMT sector, our goal in this paper is to understand why lesser-developed countries with similar initial conditions diverge in developmental strategies and outcomes within the same TIR that imposes the same rules and provides the same opportunities to member states. Why did the same LMT sector in one country become the site of industrial upgrading, and why did developments move in diametrically opposing directions in a similar country? We propose to explain this divergence by focusing on the politics of domestic political developmental alliances. We explore the emergence of a robust developmental alliance in one country and the lack thereof in the other, devoting special attention to the role played by the EU in shaping the formation of developmental alliances. We depart from the CEE version of the varieties of capitalism (VoC) literature, for it offers a depoliticized view of post-communist restructuring and reifies the image of passive competition states where FDI-dependence over-determined similar policies, developmental opportunities and constraints for domestic firms. Rather, we draw on the converging ideas developed in the political economy of development and the political economy of growth models (Amable & Palombarini Citation2008; Baccaro & Pontusson, Citation2016; Bohle & Greskovits, Citation2012; Stark & Bruszt, Citation1998). In exploring the effects of TIRs on the evolution of domestic developmental alliances, we also draw on the emerging literature on regional developmental regimes (Bruszt & Palestini, Citation2016).

We examine the Hungarian and Polish dairy agri-food LMT subsectors to demonstrate how the different developmental strategies followed by two most similar CEE countries, Hungary and Poland, yielded divergent developmental outcomes. Whereas agriculture is tied to domestic assets (land), the agri-food industry is a more complex assemblage of different production segments, stretching from agriculture to retail via processing. Agri-food is the biggest manufacturing sector in the EU and the third largest employer with 2.6 million employees (van der Meulen & van der Velde, Citation2006, p. 561). Given the complex causalities between institutional change and the political strategies of diverse actors in the period and sectors studied, we use a comparative most-similar case research design. We seek to identify continuities and junctures in policies, institutional structures and political alliances between public and private actors. Our study is based on extensive fieldwork conducted in Poland and Hungary between 2011 and 2014, semi-structured interviews with stakeholders, archival material collected from national development agencies and international organizations, expert interviews and open access datasets.

The EU’s goals and instruments of intervention in dairy evolved over time: EU institutions layered market-distorting and market-enhancing instruments, simultaneously seeking competitive upgrading via concentration and installing protections for producers threatened by it (Reardon, Henson, & Berdegue, Citation2007; Swinnen, Dries, Noev, & Germenji, Citation2006; Vorley, Fearne, & Ray, Citation2007). It is in this evolving regulatory framework that domestic strategies ought to be understood.

Poland and Hungary are most similar cases at the macro-institutional level (Bohle & Greskovits, Citation2012). In dairy, they also faced similar problems after 1989: the genetic stock of existing cow herds was poor, resulting in low productivity (milk yields) and low quality. Neither public nor private actors were prepared for the implementation of standards such as HACCP and ISO 9000 that functioned as non-tariff trade barriers on Western European markets. Domestic producers and processors needed access to capital and technology as their governments liberalized markets and enhanced competition followed the irruption of better capitalized multinational corporations (MNCs) both on domestic and export markets.

Yet only a decade later, Hungarian dairy was concentrated in the hands of MNCs that controlled 82% of the retail market, while their share in processing rose from 59% in 1997 to 87% by 2000 (Vőneki & Mándi-Nagy, Citation2014). By contrast, Polish dairy cooperatives control close to 80% of the domestic market with a market share of MNC processors around 10% (Dries & Noev, Citation2006; Szajner & Vőneki, Citation2014). The two routes could have equally led to developmental gains or bottlenecks and, during the EU pre-accession phase, both seemed functionally equivalent answers to the requirement of regulatory harmonization.

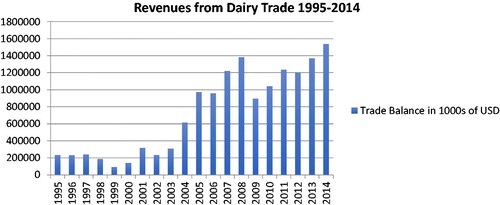

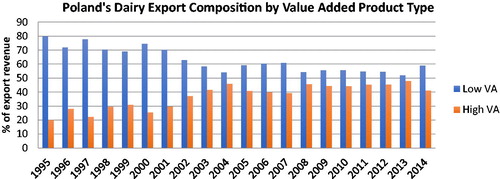

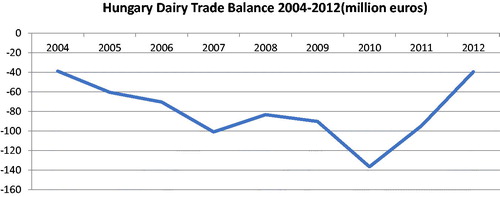

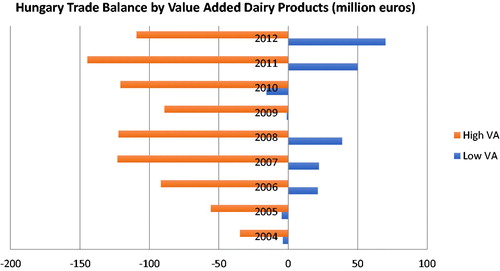

The economic outcomes in these two countries diverged dramatically: Poland’s trade balance in dairy surged from 91 million USD in 1999 to 1.2 billion USD by 2011 (), and while 80% of export revenues came from low value-added products in 1995, by 2013, the share of low and high value-added products was virtually equal (). Poland was the only new member state which radically improved its dairy trading profile since EU accession and became the fourth biggest exporter (Benedek, Bakucs, Fałkowski, & Fertő, Citation2017). Hungary by contrast experienced value-added downgrading and aggravated trade deficits: the trade balance of the sector went from a surplus of 25 million euros in 2003 to a deficit of 140 million in 2010 (). By 2013, 76% of dairy exports were concentrated in the lowest value-added products in the industry (). Even though the executive intervened to replace foreign with domestic capital in dairy processing and food retail after 2010, the trade deficit and lower value-added specialization remain.

Figure 2. Dairy exports by value added product type in Poland.

Source. own calculations based on UNCTAD.

Figure 3. Hungary’s trade balance in dairy products 2004–2012.

Source. AKI (Hungarian Agricultural Research Institute)

Figure 4. Hungary’s trade balance in dairy products by value added categories.

Source. own calculations based on KSH and UNCTAD data.

Our study reveals counter-intuitive findings. At the very zenith of the Washington consensus in the 1990s, the Polish state utilized forms of intervention reminiscent of a twentieth century developmental state, managing a developmental coalition with farmers that turned the latter into national champions. This would have seemed unlikely for a state that was widely perceived as being deeply rooted in the neoliberal camp at the time (Orenstein, Citation2001). Having followed the recipe of FDI-based development, the Hungarian pathway shows how deficient public support systems and ‘outsourced’ development might lead to marginalizing domestic labor and capital relative to MNCs instead of mechanic upgrading through contractual relations (Gow, Streeter, & Swinnen, 2000). Foreign-led restructuring resulted in value-added downgrading and ‘import intensive deficit-prone industrialization’ that Robert Wade associates with FDI-based development in HT sectors (Wade, Citation2010). Following MNC divestment in Hungary, the void was replaced by a national coalition of strongly capitalized entrepreneurs and a state that encouraged domestic ownership. After 2010, economic nationalism was used under the guise of crisis management to rebalance an ownership structure benefiting MNCs in the value chain and to improve the competitiveness of ‘farmers’. However, beyond this rhetoric device only a restricted pool of entrepreneurs benefited from rents allocated by the government, while the sector’s competitiveness continues to falter.

Our case studies contrast two coalitions driven by nationalist narratives in post-communist regimes: one emerged in Poland immediately in 1989 as a reaction to neoliberal hegemony. The other coalesced in Hungary after two decades of laissez-faire. Yet, the first emanated from bottom-up societal demands, increased the state’s accountability while giving rise to competitive upgrading for private actors and extended administrative capacities for the state. The second was the top-down project of an unaccountable executive strengthening its own clientele.

We will use the dynamic notion of institutional complementarity (Amable, Citation2016) to explain the role of the EU in these diverging outcomes. For a social group, two or more institutions are complementary when their joint presence reinforces the group or protects their interests (Amable, Citation2016). The external imposition of a new institution might strengthen these groups and further their interests or, it might have exactly the opposite effect in a different domestic institutional setting. As we will show, the bottom-up pressure exerted by Polish peasants in the early 1990s has had two consequences: incumbents in Poland considerably upgraded the sectoral institutions’ complementary to the regulatory institutions imposed by the EU in the second half of the 1990s and strengthened the evolving developmental alliance between state and non-state actors. In Hungary, the importation of EU regulatory institutions, in a different institutional setting further marginalized producers and increased the dependence of the state on MNCs that pursued their short-term interests only. After EU accession, we can observe similar dynamics at play as a result of the inclusion of these countries in the institutional framework of EU assistance.

In the next section, we discuss factors that can help or hinder the formation of developmental alliances in countries entering transnational markets. Section 3 and 4 will discuss the development in Hungary and Poland in detail, and Section 5 concludes.

2. The politics of developmental alliances

The common starting point of authors who reject a depoliticized view of development is that change in developmental paths requires large-scale institutional investment, extraordinary collective action and coalition building (Doner & Schneider, Citation2016). To identify and exploit developmental opportunities, as well as to mobilize resources to change a developmental path requires states with increased autonomy from status quo-oriented groups and new institutional capacities. It also takes institutions that allow non-state actors to coordinate, to provide effective representation and to enter in arrangements that need inter-temporal tradeoffs.

The problem of changing developmental paths is that these institutions and capacities are not at hand when new opportunities arise or when external shocks would demand considerable change. States are either captured by powerful status quo-oriented actors or even if they are not, they are weak and non-state actors have no or weak capacity to make effective demands and alter the institutional status quo. External actors can help or hinder modification in developmental paths by altering the parameters of domestic institutional change (Jacoby, Citation2010).

Why does the transfer of the same institution yield diametrically opposing outcomes? Our theoretical frame to answer this question starts with the converging ideas of the political economy of development and the political economy of growth models (Amable & Palombarini Citation2008; Baccaro & Pontusson, Citation2016; Bohle & Greskovits, Citation2012; Stark & Bruszt, Citation1998). They have in common a focus on the politics of institutional change, the exploration of the factors that can help or hinder the emergence of developmental alliances, coalitions of social and political forces that can conserve or alter the institutions responsible for a specific developmental path and (re)define the goals of development.

The outcomes of previous struggles for change in developmental paths (Doner & Schneider, Citation2016), the pre-existing structure of political institutions (Stark & Bruszt, Citation1998), and the specifics of national identity (Bohle & Greskovits, Citation2012) shape the chances of forming more or less inclusive coalitions that respond differently to similar international constraints and opportunities of development. Dominating social blocs might build complementary institutions within the state and the economy that allow for increasing the capacities of private and public actors in the coalition. These can in turn detect and exploit new developmental opportunities. Alternatively, dominating coalitions might block institution-building and conserve a suboptimal path of development (Doner & Schneider, Citation2016; Amable & Palombarini Citation2008). Finally, hegemonic conceptions of development, dominating ideas about the proper role of states and markets in development might consolidate or alter diverging national approaches to these issues (Ban, 2016).

Translated to the level of sectors, we can expect four factors to play the most important role in shaping developmental alliances and making them more inclusive. First, the institutional characteristics of the polity in which the sector level decision-making is embedded provides the terrain on which coalitions for or against changing developmental paths are formed. The presence of checks and balances within the state, and of electoral regimes that favor coalition governments extend the accountability of incumbents while limiting the room for arbitrary decisions. Extended horizontal accountability of incumbents creates an institutional environment conducive to the emergence of more inclusionary developmental alliances.

Second, extended vertical accountability of incumbents provided by strong effective competition among political parties with solid roots in society can create favorable conditions to politicize development in specific sectors and mobilize political support for change. Third, the presence of sectoral bureaucracies staffed with skilled and autonomous bureaucrats is the sine qua non condition to build an inclusive developmental alliance. Finally, the presence of autonomous organizations of non-state actors in the sector with the capacity to provide unified representation and to create alliances among different categories of producers might force incumbents to care about more inclusive notions of development. While many of the lesser-developed countries do not meet these institutional conditions, the actual situation might differ from sector to sector in most of the countries, depending on the specific combination of the above factors (Evans, 1995).

TIRs can alter several of the above discussed parameters of domestic change. They can strengthen both the autonomy and the efficiency of core state institutions (see the paper on Collateral Benefits in this issue), they can shape a domestic political agenda via positive and negative incentives, transfer know-how and resources to strengthen sectoral state institutions or the organization of non-state actors. Whether and to what degree TIRs change the parameters of core state institutions and of the polity might determine the effects of imposing specific institutions from outside. While in some domestic institutional contexts the externally imposed institutions might help pushing development in the right direction, in others they might even worsen the conditions of change.

The dynamic notion of institutional complementarity (Amable, Citation2016) might be helpful to understand these diverging outcomes. Contrary to the depoliticized notion of institutional complementarity of the VoC approach, Amable’s concept of dynamic institutional complementarity focusses on shifting alliances among diverse types of actors. For a social group, two or more institutions are complementary when their joint presence reinforces the group or protects their interests (Amable, Citation2016). The external imposition of a new institution might strengthen domestic actors and allow them to further their interests in other institutional fields too. But the external imposition of the same institution might have exactly the opposite effect in a different domestic institutional setting. The regulatory institutions imposed by the EU, for example, perfectly complemented the pre-existing institutional conditions in the Polish dairy sector and have considerably strengthened the developmental alliance between state and non-state actors. As we will show below, the imposition of strict regulatory institutions by the EU provided incentives for deepening the developmental coalition in Poland and worked as a disciplinary mechanism, preventing the developmental alliance from turning into a pure rent-seeking association. In Hungary, where sectoral state institutions were fragmented, and weak producers did not have effective political representation, the imposition of the same regulatory institutions had the opposite effect: they further marginalized producers and increased the dependence of the state on MNCs that pursued their short-term interests only.

After EU accession, we can observe similar dynamics at play as a result of the inclusion of these countries in the institutional framework of EU assistance. In Poland, the developmental alliance between the sectoral state and the representative organizations of dairy cooperatives, endowed with robust institutional capacity for policy coordination and monitoring could use the opportunities provided by EU transfers for industrial upgrading. The high-level politicization of development in agriculture and agri-business by competing political parties helped to reduce the room for large scale misuse of EU transfers. By contrast, after 2010 the decreasing horizontal and vertical accountability of the Hungarian government was combined with the low monitoring oversight of EU transfers. This has provided an ideal terrain for consolidating a rent-seeking alliance between the ruling party and large agri-business entrepreneurs.

The ad hoc nature of EU interventions plays a key role in the diametrically diverging outcomes. Comparing EU interventions in post-accession dairy in Hungary with the pre-accession EU interventions in the automotive sector (see the paper on Romania in this special issue) might help to make this point. In the pre-accession period, the EU played a direct role in the simultaneous transformation of several core state institutions that could affect the chances of forming developmental alliances and alter the developmental path of the sector. The interventions of the EU increased the overall autonomy and bureaucratic capacity of the state, thus preventing the consolidation of domestic rent-seeking alliances. They also provided assistance to transform the properties of the sectoral state and endowed it with resources to obtain the support of labor for privatization. Their combined effects helped the Romanian state to successfully insert the automotive sector in the regional market. In the post-accession period, the interventions of the EU in the dairy sector in Hungary were more limited, leaving the pre-existing sectoral institutional framework largely unchanged. Worse, in the post-accession period the EU did not apply the strict pre-accession criteria for the autonomy and effectiveness of core state institutions (CitationSee the paper of B/M/L in this issue). Incumbent governments could reduce the autonomy of the state bureaucracy and the judiciary and use these institutions to strengthen their own political power. In the automotive sector, the EU-induced upgrading of core state institutions yielded considerable developmental convergence between Romania and Poland. But because in the post-accession period, the EU does not prevent member states from manipulating the properties of their core state institutions, the importation of the very same EU developmental programs has contributed to developmental divergence between Poland and Hungary.

3. Hungary: developmental bottleneck

3.1. Outsourcing development and competitive downgrading

The first democratically elected government of Hungary did not have a comprehensive strategy for inserting the dairy sector in transnational markets, improving its competitiveness, and supporting domestic farmers and firms. The milk producers and the firms in the processing segment of the industry did not have strong political representation, and short-term economic and political interests played a central role in fragmenting the previously integrated sector, thus marginalizing producers and preparing the ground for FDI-led transformation.

The ownership structure of the dairy supply chain was the product of successful land and processing collectivization during state socialism, leaving the state as sole proprietor of dairy processing assets. After 1990, the privatization of dairy processing was insulated from political demands and divorced from the question of land and cooperative restructuring: the sectoral bureaucracy of the state was truncated as the management of restructuring strategies in processing and production fell to ministries controlled by political parties in the governing coalition with different objectives. On the one hand, the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Privatization were both controlled by the senior Christian-Conservative coalition partner MDF and leveraged privatization to secure hard currency in order to service external debt: The Socialist Dairy Trust was disbanded in 1991, with its 15 processing plants fragmented into 36 units and transferred to the Privatization Agency to be auctioned to MNCs (Gorton & Guba, Citation2002; Mong, Citation2012). On the other hand, the Ministry of Agriculture controlled by junior coalition partner Smallholders Party FKGP was in charge of land restitution, headed by József Torgyán, an urbanite lawyer only loosely connected to peasants (Cseszka & Schlett, Citation2009). Cooperatives provided 92.3% of land for restitution – a policy enjoying high support among better endowed farmers and cooperative managers, who hoped to form a new rural bourgeoisie (Harcsa, Kovács, & Szelényi, 2003). The breaking up of cooperatives enjoyed high support among better endowed farmers and cooperative managers, who hoped to form a new rural bourgeoisie (Cseszka & Schlett, Citation2009). The obliteration of cooperatives created small plots, fragmented land tenure and accelerated the marginalization of farmers: by 1997, cooperatives only represented 3% (697 million HUF) in the capitalization of the dairy sector, which stood at 23.4 billion HUF (Szabó, Citation1999).

The institutional, political and strategic separation of privatization in the production and processing segments of the sector led to a segmentation of the dairy supply chain. The sellout of dairy processing to MNCs spurred a rapid concentration in the processing segment, all the while land privatization destroyed producer cooperatives and fragmented production. By 1993, both the vertical coordination of the sector and the question of upgrading the supplier bases were outsourced to MNCs. As the farmers lacked autonomous organizations to voice effective demands, the incumbents faced neither resistance nor incentives to develop new institutions or a sector-level industrial policy.

Without a cohesive sectoral bureaucracy and a developmental alliance, changing MNC interests shaped the development of the sector. MNCs, controlling 80% of processing, pursued aggressive merger and acquisition strategies, fueled by the global concentration of food processing in the 1990s (Allen, Citation2010), which translated in a ‘scorched-earth’ strategy to buy out domestic processors and reduce competition. MNCs did not make longer term commitments and exploited the availability of cheap inputs from the producers.

The systematically unfair contractual clauses and low prices resulting from MNC processors had several consequences: suppliers often sold their produce (fresh milk) in small quantities for export, MNCs complained that suppliers were unreliable, and producers complained that MNCs used unfair contracts. Overall, the sector began importing high VA and exporting low VA dairy goods, thus increasing the trade deficit. The output in milk dropped from an average of 2850 tons in the late 1980s to 1812 tons in 2012 (Tej Terméktanács, Citation2013, p. 6). Small producers were the first victims of the concentration spurred by MNCs. The number of dairy farms decreased by a third in the first decade of the transition and was further halved between 2002 and 2012 (Bakucs, Fałkowski, & Fertő, Citation2012). The elimination of small producers was accompanied by a reduction in output, and the trade balance dropped from a surplus of 25 million euros in 2003 to a deficit of 140 million by 2010. Value-added downgrading would only accelerate after 2004: trade deficits in higher value-added goods such as cheese, curd and butter soared after EU accession, while the sector specialized in the export of fresh milk, cream and powder so that by 2013, 76% of dairy exports were concentrated in the lowest value-added products ( and ).

Then came along the retreat of foreign capital due to a weakness of the Hungarian fresh milk suppliers and rising tensions with Hungarian suppliers of fresh milk. This vacuum encouraged Hungarian processors to re-purchase the plants left behind by MNCs in a process of re-domestication. Two firms stood out in particular: the Alföldi Milk cooperative and the SoleMizo group. Alföldi Milk is the only successful large-scale producer cooperative: set up in 2003 by 54 large suppliers of Dutch Nutricia and of Italian Sole, its membership is composed of big farms with strong capitalization.2 Alföldi bought Parmalat’s bankrupt operation in 2003 and FrieslandCampina’s flagship plant in Debrecen in 2015 (formerly Hajdú Milk).

The second important domestic group is SoleMizo, controlled by János Csányi,3 one of Hungary’s most prominent tycoons. The group was born from the merger of two firms (Sole and Mizo). After the merger, SoleMizo instantly became the biggest processor in Hungary, and with a market share of 31.7% relegated FrieslandCampina to the third place, behind Alföldi Milk. The latter controlled 20% of the market in 2013: in other words, the two big Hungarian dairy processors now controlled half of the market together, a radical change compared with the 1990s.

3.2. Statist crisis management and economic nationalism

By the end of the 2000s, a nationalist protectionist alliance emerged between the state and key actors in the sector. As the Hungarian dairy processors became central actors in the supply chain, they started lobbying for public re-regulation. In 2007, Hungarian dairy processors enlisted other Hungarian food processors and secured support from the Ministry of Agriculture to draft an Ethical Codex, that is, a self-regulatory standard to impose national quotas onto food retailers. The dominant supermarkets in HU were foreign owned (Tesco, Auchan, Lidl, Spar etc.), so fighting against the ‘unfair margins’ of food retailers was also portrayed as a struggle of national against foreign capital. The processing firms consciously claimed their alliance with producers to frame protectionism as a struggle of Hungarian interests against foreign supermarket chains. The attacks against MNCs did not achieve a breakthrough: the final text signed by the ten biggest foreign retailers only entailed a self-regulatory code restricting unfair business practices (GVH, Citation2006). Yet the state’s support for a protectionist regulatory initiative proved a critical juncture: a new coalition emerged between the state and domestically-owned food processors to curtail MNC market share – still under a Socialist-Liberal government.

The institutionalization of this alliance could rely on changes in EU policies vis-à-vis MNCs in the agri-food industry. In the wake of the financial crisis, the EU Commission sought new strategies to empower national dairy producers threatened by MNC market power. Three EU Regulations, called the Milk Package, were adopted in 2012.4 The objective was (1) to ban unfair business practices by regulating milk purchase contracts, (2) to strengthen the bargaining power of small producers through cooperatives, and (3) to create new regulatory bodies at the national sector level called ‘inter-branch organizations’ (IBO) regrouping all stakeholders.

Large Hungarian dairy processors used these new EU regulations to gain legitimacy and a new legal status: they obtained governmental support to rebrand the Milk Council as an IBO endowed with a nascent regulatory role in 2013. While the Council gained self-regulatory capacities, it represented the specific interests of Hungarian dairy processors: although putatively regrouping 3750 producers, 40 processors, and 6 retailers, nineteen out of 21 Directory Board delegates were Hungarian-owned processors. As FDI had retreated from processing, the strategic enemy became foreign-owned food retailers,5 accused of compressing margins for Hungarian producers and processors, routinely using unfair contractual clauses and dumping prices on imported milk and cheese.

Since 2010, the Fidesz governments shifted away from a decade long practice of tacit support for domestic dairy processors, displayed also by the Socialist Liberal government, to regulations that explicitly discriminated against foreign capital after 2010. They adopted a series of legal acts, which sought to incapacitate MNC retail chains, curb their market share and/or force them out of the country. A new coalition emerged between Hungarian cooperative Alföldi Milk, tycoons in the agri-food sector such as Csányi, domestic retail chains as well as a right-wing Fidesz government elected in 2010 with the promise of breaking away from FDI dependency.

The re-domestication of the sector stood on three feet: (1) transferring public assets to domestic capital through irregular privatizations, (2) squeezing MNC market shares via discriminatory legislation, and (3) empowering a sector-level regulatory body controlled by domestic processors. Back in 2001, the first Orbán government privatized twelve agro-food SOEs that ended up in the hands of tycoons such as Sándor Csányi, who acquired dairy processor Sole-Mizo and grain giant Bonafarm (Tamás, Citation2013). This process was shielded from foreign capital because a moratorium on foreign participation until 2014 was accepted by the Commission. Before the moratorium expired and with Fidesz once more in power, a new Land Act was adopted in 2013 (Csák, Citation2017), paving the way for the privatization of 300,000 hectares of agricultural land. These auctions were marred by irregularities: smallholders were crowded out by owners of agro-processing firms and their relatives, who registered ‘family farms’ just to lease back the acquired land to their processing branch afterwards. This mechanism allowed Fidesz founder Szajkó and his wife to win over 8% of all auctioned land in Western Hungary in 2015, located in the vicinity of their dairy processing plants (Ángyán, Citation2016, p.18). The official status of their facilities also helped Csányi’s farms and Fidesz tycoon Zsolt Nyerges’ Mezort dairies to secure a place among the ten biggest beneficiaries of dairy-targeted EU and national subsidies according to the Treasury’s database.6 Csányi’s SoleMizo benefitted from a further 16 million euros in subsidies from the Ministry of National Economy in 2018 alone.7 While the ECJ condemned the 2014 privatization wave, a decision was only issued in March 2018 (ECJ, Citation2018).

The financial crisis opened venues for radical interventions: ‘crisis taxes’ were imposed in 2010 on retail chains with revenues above 500 million forints and equaled up to 2.5% of their turnover. MNC franchises had to pay higher taxes then similar Hungarian chains (Mihályi, Citation2016).

After being granted IBO status, the Milk Council waged successful lobbying efforts to further strengthen the positions of Hungarian firms. First, against the low purchasing price of fresh milk by MNC food retailers, later to reduce the VAT rate of UHT milk. For the 2015–2020 period, the Ministry of Agriculture earmarked 1 billion euros from EU and national sources for the modernization of dairy processing and raised direct funding for the overall dairy sector from 86 to 166 million euros annually. The Milk Council further secured an envelope of 1.4 million euros for the domestic advertising and promotion of nationally produced milk.8 In October 2015, the European Commission announced an Exceptional Adjustment Aid (EAA) of 500 million euros to compensate farmers after Russia banned EU food imports. A second ‘Solidarity Package’ was announced in July 2016, including 350 million euros specifically earmarked for dairy: Hungary used all its earmarked funds (9.5 million euros twice) to support the dairy sector and further matched EU funds with a 1:1 ratio.9 These developmental funds were hijacked by incumbents to build a clientele under the guise of crisis management.

Although domestic capital replaced FDI, the competitiveness of the sector remains weak on both domestic and export markets. The trade deficit remains structural: it was halved from –94 million euros in 2011 to –46 million euros by 2015. By 2018, the skewed value-added trade deficit remains: imports of higher value added dairy products increased by 6% and exports of low value-added goods decreased by 2% on a yearly basis, while domestic consumption dropped by 10% (MIlk_Council, Citation2018).

4. Poland: the national route to transnationalization

4.1. Restructuring the sector through a domestic developmental alliance

Unlike in Hungary, in Poland agricultural producers and their cooperatives benefitted from a strong political representation that could prevent the fragmentation of the sector and the dissolution of cooperatives. Early on, the government developed agencies to nurture economic transformation and to help the insertion of the sector in European markets.

Dairy cooperatives had played a key role in the Polish nationalist state-building project since the nineteenth century. During the division of Poland, the cooperative movement was a prelude to independence for the gentry and rural bourgeoisie (Bartkowski, Citation2013). By 1947, Sovietization led the Communist leadership to disband dairy cooperatives, before nationalizing the sector in 1951. However, civilian resistance forced the Party to reverse collectivization (Jarosz, Citation2014): dairy cooperatives were reestablished, and a National Union of Dairy Cooperatives was created in 1958 (Hunek, Juhasz, Fisher, & Stipetic, Citation1994).

In 1990, the first democratic government terminated the central Union of Dairy Cooperative seeking to transform cooperatives into capitalist entities. Resistance to hard privatization among both the Solidarity leadership and the farmers led to the adoption of a new Act on Cooperatives in 1992 co-drafted with cooperative leaders. It defined cooperative ownership a form of private property derived from their individual members (Hunek, Citation1994).

One could suspect that the sheer size of agriculture mechanically explains the state’s policies. In the early 1990s, agriculture accounted for 27% of aggregate employment and 7% of GDP (Winiecki, Citation1997). However, forceful and sustained collective movements by dairy producers proved vital for changing the strategy of policymakers. In June 1990, a road blockade organized by dairy producers protesting against low purchasing prices in Mława was the first instance where the new republic sent the police to dismiss a social movement (JPRS, Citation1990). The economic and symbolic stakes were high: farmers demanded state support for restructuring at the height of the Balczerowicz Plan, which favored shock therapy precisely before democratic accountability could tie the hands of the incumbent government. This first in a series of protests organized by dairy farmers and cooperatives challenged the legitimacy of the Solidarity coalition government born of grassroots mobilization. The rift opened between the Solidarity government and farmers provided political space for the Communist successor party SD and the All-Poland Alliance of Trade Unions (OPZZ) created by the Communist state in 1984. Lech Wałęsa intervened in the conflict as it provided a personal venue to outmaneuver Prime Minister Mazowiecki in the upcoming presidential elections in December and to prevent a coalition of farmers and former Communist organizations. He travelled directly to Mława, endorsing farmers’ demands (Feffer, Citation1992). Mazowiecki refused to give in, but protests continued: throughout 1990 and 1992 sit-in protests in the Ministry of Agriculture and road blockades went on. The protests were supported by parties close to the government such as the agrarian branch of Solidarity (NSZZ RI Solidarność) but also ideological enemies linked to the former Communist apparatus such as Agricultural Circles (KZKiOR) and the Committee for Farmers’ Self Defense.

Meanwhile, the Central Union of Dairy Cooperatives (CUDC) was disbanded by the liberal government, prompting farmers to occupy its building as protests went on. In April 1991, farmers flooded the Ministry of Agriculture with butter asking for support prices (Gorlach, Citation2000). Between 1990 and 1992, the cycle of contention opened by farmers represented the biggest stumbling block for the depoliticized reformism of the first coalition government. Poland was not only a regional model of shock therapy (Appel Orenstein, Citation2018): it also showcased immediate social resistance to neoliberal restructuring.

In the end, the sustained resistance to depoliticized transformation of the sector won. It led to the adoption, in 1992, of a new Law on Cooperatives co-drafted with cooperative leaders which defined cooperative ownership a form of private property derived from their individual members (Hunek, Citation1994). The government went beyond providing rents to pacify discontent. Instead, it used existing resources to build an effective sectoral bureaucracy coopting societal demands: A Governmental Committee for Improving the Competitiveness of the Dairy Sector was set up in the Ministry of Agriculture (MAFE), followed by the creation of an Office of the Plenipotentiary for the Dairy Sector (FAPA, Citation1991) and the setting up of the Agricultural Market Agency (AMA) for market monitoring and intervention (GATT, 1992b). The disbanded CUDC was also reformed in 1992 under the new Law on Cooperatives.

4.2. External constraints and opportunities for development

Unlike in Hungary, external assistance programs were of considerable importance in the creation of developmental state capacities in Poland. The emerging developmental alliance played a key role in integrating external assistance programs with sectoral developmental plans. The first ad-hoc bilateral aid projects, such as the Dutch initiative ‘transfer the Dutch model of dairy farming’ (FAPA, 1992), were replaced with comprehensive programs as the World Bank (WB) and the European Commission (EC) got involved: an Agriculture Task Force set up by the WB submitted the report ‘An Agricultural Strategy for Poland’ to MAFE, which shared it with the EC Council for deliberation. The outcome was a Medium-Term Sector Adjustment Program (MTSAP). Under MTSAP, the WB and the Polish government agreed on an Agricultural Sector Adjustment Program (ASAL) in May 1993, for an investment program of 330 million USD financed by the WB (MAFE, Citation1995). This program also provided the framework for an administrative overhaul of public regulatory organizations. The Foundation of Assistance Programs for Agriculture (FAPA) in charge of overseeing all infrastructural modernization projects as well as credit programs was set up as an implementing organization to ASAL. The Agency for Restructuring and Modernization of Agriculture (ARMA), the chief credit agency, as well as the Foundation for Rural Development (FRD), another fund created for financing modernization investments, were also established under ASAL (MAFE, Citation1991). Polish implementing agencies used the funds under ASAL and the European PHARE program to recapitalize dairy cooperatives. In July 1990, 800 billion PLN were allocated to restructuring the dairy sector, out of which 250 billion were earmarked for credits. By 1991, this credit line was exhausted but it had saved 260 dairy cooperatives on the verge of bankruptcy (MAFE, Citation1991).

The Polish state could count on representatives of the sector to identify externalities and suitable modes of intervention. In August 1994, the National Union of Dairy Cooperatives drafted a document, which became the template for MAFE’s ‘Program for Restructuring and Modernizing Dairy’: cooperatives were coopted in designing a developmental roadmap. Between 1994 and 1997, 355 million PLN for 9284 individual contracts were allocated to milk production and 300 million PLN in 362 projects for processing under MAFE’s 1994 sectoral development program co-drafted with cooperatives (FAPA, Citation2000). Besides direct access to capital, the state also fixed intervention prices to allow for guaranteed revenues for farmers and to offset price fluctuations. The PHARE program ‘Quality Management in the Dairy Sector’, implemented between 1996 and 1998 was a direct offshoot of ASAL, only the funding source changed as EU funds replaced the WB: trainings in ISO 9000 quality monitoring were delivered to key dairy cooperatives. State laboratories and veterinary inspectorates received trainings as well as new machinery (FAPA, Citation1996).

Although Poland was negotiating trade liberalization under GATT and the Europe Agreement (EA), protectionist safeguards for the sector were extended under the pressure of farmer mobilizations in 1991 (Chloupkova, Citation2002). Dairy was deemed a strategic manufacturing sector alongside automobiles, electronics and meat – necessitating protection against imports under asymmetrical liberalization with the EC and dumping by MNC importers (GAO, Citation1995). The EA accepted a Restructuring Clause (article 28) allowing for the temporary protection of strategic infant industries10 (Michalek, Citation2000). A devaluation of the złoty in 1991 was coupled with the implementation of differentiated import duties by product segment: 70% for milk powder, 40% for butter, and 35% for yoghurt and cheese (FAPA, Citation2000). Import licenses for dairy goods delivered by the Ministry of Foreign Economic Relations were introduced in 1992 (GATT, Citation1992a). Taking the example of the public support systems in OECD countries, the state intervened in the market through the newly created AMA for fixed intervention prices, public sales and purchases of key products such as butter as well as for ensuring credit lines towards restructuring the sector (GATT, 1992b). In 1999, import levies were further increased from 9% to 35% on flavored yoghurts and from 40% to 111% on butter (WTO, Citation2000).

The Polish developmental alliance even used the stringency of the EU’s sectoral food safety regulations as an incentive structure for competitive upgrading. In 1997 the EU’s Food and Veterinary Office Inspectorate banned Polish milk exports to the EU arguing that food safety standard compliance was not satisfactory. The ban boosted cooperation between the state and cooperatives (Bruszt & Langbein, Citation2014): the government program provided help for cooperatives that could not meet the ISO 9000 and HACCP standards. In 1999, Poland introduced the EU’s classification system of milk quality in three classes. It prohibited processors from buying ‘third class’ (lowest quality) milk in 2000 and ‘second class’ milk was phased out in 2003 (Dries & Swinnen, Citation2007, p. 426). The incentive was a subsidy for first class milk producers (Malak-Rawlikowska, Citation2006). The strategy proved successful as 85% of milk complied with EU criteria by 2003. The EU Commission accepted that Poland continued financing dairy upgrading programs even after accession alongside the objectives fixed in the 1994 document ‘Development Strategy for Polish Dairy’ co-produced with cooperatives. It did so on the condition that these programs differ from the criteria of EU structural fund support. This proved important as it allowed ARMA to finance a further 14.8 million EUR for preferential credits in 2003 (Malak-Rawlikowska, Citation2006). External financial resources thus played an important role not only in direct transfers and subsidies but also financing the state’s own expanding sectoral bureaucratic oversight and competence.

Contrary to claims that FDI in processing and food retail played the most important role in the modernization of Polish dairy (Dries & Swinnen, Citation2002, Citation2007; Swinnen et al., Citation2006) we found the Polish case to be a success story based on the developmental alliance of the state and dairy cooperatives. The specificity of Polish dairy is precisely the low level of FDI penetration: in 2004 domestic cooperatives controlled 80% of the market and foreign owned companies only 10% (Seremak-Bulge, Citation2005).

MNC processors first functioned as importers through joint-stock companies under a 3-year tax exemption scheme. When one of the MNCs imported cheese selling at dumping prices the Polish cooperatives successfully lobbied the state to raise import duties. This forced MNCs to invest in local production (Chloupkova, Citation2002). Integrating local capacities lagging behind in technology proved costly: the quality of fresh milk was so bad that Danone had to import Dutch animal feed (Ricard, Citation2010; Zinsou, Citation1997). After exploratory investments, many MNCs left the market: Friesland did so in 1998, Nestlé in 2003, Campina and Avonmore in 2004. Successful MNCs specialized in high value-added niche products such as premium cheese and yoghurt drinks, where they could leverage stronger capital and service intensity, as did Danone, Zott, Hochland, Bongrain and Lactalis. MNCs could not outcompete Polish dairies on volumes. While the bigger Polish cooperatives integrate thousands of producers, MNCs are confronted with the fragmentation of land tenure, which weakens their supply base: in 2008, 87% of dairy farms still had under ten cows (Bryla & Domanski, Citation2012). Among MNCs, only Danone became a major player with a market share of 6% (Janiuk, Citation2014).

The market share of the biggest dairy cooperatives is considerably larger than that of MNCs. Mlekpol and Mlekovita are the two largest Polish cooperatives, with a 13% market share each and yearly revenues over 710 million EUR (Janiuk, Citation2014). They both export 30% of their production. Both dairies grew by absorbing smaller plants in the 1990s: Mlekpol acquired 11 dairies between 2005 and 2011, while Mlekovita now operates a network of 14 collection and distribution centers across Poland.11 Mlekpol integrates 14,000 farmers and employs a further 2300 people, its exports target the EU market and it covers all value added (VA) categories with 500 products.12 Mlekovita employs 4000 people, has 16 production plants and offers 700 products.13 It established its own distribution wholesale network complemented with a Cash and Carry retail store in Warsaw, undercutting supermarkets. It is the only Polish dairy with its own R&D laboratory, a project co-financed by the EU’s Regional Development Fund and the Polish regional development program in 2013.14 It entered the Russian market via FDI by building its own processing plant in the Kaliningrad exclave, specializing in the high VA cheese market and came to control 10% of this market in Russia.15

5. Conclusion

Our goal in this paper was to understand why lesser-developed countries with similar initial conditions diverged in developmental strategies and outcomes within the same TIR that imposed on them the same rules and provided them the same opportunities. Why did the same LMT sector in one country become the site of industrial upgrading yielding fast increase in domestic value added and why did developments move in diametrically opposing directions in a country with similar starting conditions? We focused on the politics of the emergence of sectoral developmental alliances and developmental state capacities, and the role played by EU in shaping both. We have identified four institutional areas, settings that can structure in their different combinations the domestic politics of developmental blocks. In a nutshell, we argued that strong horizontal accountability within the state combined with vertical accountability of incumbents by competing parties with strong roots in society provide a conducive macro-political framework for the emergence of sectoral developmental alliances. Well-organized economic actors with strong representative institutions can have better opportunities to make effective demands on the state in such a framework with or without the help of institutional actors within the sectoral state and of political parties with stakes in sectoral developmental outcomes.

This analytical frame lists only the key institutional arenas that shape the chances of forming a developmental alliance. But this frame served us well, combined with Bruno Amable’s dynamic concept of institutional complementarity to explore why the imposition of the very same regulatory institution and assistance program by the EU TIR could yield dramatically different outcomes. In Poland the upgraded sectoral institutions smoothly complemented the regulatory institutions imposed by the EU and strengthened the evolving developmental alliance between state and non-state actors. In Hungary, in a very different domestic institutional setting, the same regulatory institutions further marginalized producers and increased the dependence of the state on MNCs. Unlike in the automotive sector, in the dairy the EU did not intervene in the evolution of sectoral state institutions (see the paper on Romania in this SI).

The ad hoc nature of EU interventions in domestic institutional settings is a key factor in inducing developmental divergence after the accession. In the pre-accession period, the EU interventions included measures to upgrade core state institutions by increasing the autonomy and the capacity of bureaucracy and judiciary. After accession the EU interventions targeted solely a narrow set of institutions, basically leaving it to the national governments to change the properties of core state institutions at will to stabilize their own political power. Such limited external interventions, however, leave to bona fortuna the effects of the externally imposed institutions. With some luck, the externally imposed institution is a good match to domestic institutions, themselves outcomes of attempts by domestic actors to form developmental alliances and complementary developmental state capacities. With bad luck, the same externally imposed institution can strengthen pre-existing rent-seeking alliances and weaken actors who might benefit from increased developmental state capacities.

In 1989 neither the administrative capacities of the state, nor the competitiveness of Polish dairy were better than in Hungary. However, farmers organized in cooperatives created societal demand for an expansion of state intervention in Poland. Helped by political parties, the demand for public developmental intervention yielded governmental efforts at strengthening public administrative capacities and the coming about of a sectoral state willing and capable to enter a developmental alliance with the representatives of producers. This developmental alliance could capitalize on the imposition of regulatory institutions of the EU and it could make extensive use of opportunities and resources offered by Brussels.

In Hungary, producers did not have the resources and the organization to make effective demands on the state and, unlike producers in Poland, they did not have political representation within the state. The fragmented sectoral state left the problem of upgrading to MNCs. The imposition of EU regulatory norms in this setting led to the marginalization of domestic producers and it further increased the dependence of the state on MNCs. The decrease in the accountability of incumbents after 2010 has further strengthened the room for incumbents to use EU transfers to enrich loyal domestic entrepreneurs at the price of the further marginalization of the producers. While the Polish sector’s dominant cooperatives represent a social class of farmers, in Hungary farmers are a rhetorical device without political representation and virtually absent from an industry controlled by strongly capitalized entrepreneurs. While the Polish developmental alliance effectively improved the value-added and export competitiveness of the sector with the use of EU transfers, in Hungary the latter helped to consolidate a new social class in alliance with a de-democratizing political elite.

Notes on contributors

László Bruszt is Professor of Sociology at the Central European University (Budapest). His more recent studies deal with the politics of market integration. His latest publications include Leveling the Playing Field – Transnational Regulatory Integration and Development (Bruszt & Langbein, Citation2014); ‘Varieties of Dis-embedded Liberalism EU Integration Strategies in the Eastern Peripheries of Europe’, Journal of European Public Policy (with Julia Langbein); and ‘Making states for the single market: European integration and the reshaping of economic states in the Southern and Eastern peripheries of Europe’(with Visnja Vukov).

David Karas holds a PhD in Political and Social Sciences from European University Institute, he is currently Assistant Professor in European Studies at Manipal Academy of Higher Education where he teaches postgraduate courses on European integration and International Relations. His research interests focus on the comparative political economy of development in Central Eastern Europe and the Global South.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 There are several classifications, technology taxonomies, for example, Kaplinsky-Santo Paulino (2005) or the the United Nations Commodity Trade Statistics (UN Comtrade) Database. In this paper, we rely on the classification used in the United Nations Commodity Trade Statistics (UN Comtrade) Database, which contains detailed international trade flows data reported by about 200 countries all over the world. The dataset is available here: http://comtrade.un.org/data/

2 Interview with Tibor Mélykuti, CEO of Alföldi Milk, Székesfehérvár, 01 December 2013.

3 Csányi is notably the CEO of Hungarian bank OTP. The agricultural part of his empire is called the Bonafarm Group, regrouping a dozen processing firms in meat (Pick), cereals (Bábolna), wine (Csányi) and dairy (Sole-Mizo).

4 Regulation 511/2012 on ‘Interbranch organizations’, Regulation 880/2012 on transnational producer groups and Regulation 261/2012 on contractual relations.

5 Interview with László Lukács, Hungarian Milk Council, Budapest 13 October 2013.

6 https://www.mvh.allamkincstar.gov.hu/-/tamogatasi-adatok-a-bizottsag-908-2014-eu-vegrehajtasi-rendelete-alapjan-publication-of-data-according-to-commission-implementing-regulation-no-908-20.

7 http://kamaraonline.hu/cikk/beruhazasok-kormanyzati-tamogatassal-ezek-a-cegek-nyertek.

10 Art. 28 states of the EA states: ‘These measures may only concern infant industries, or certain sectors undergoing restructuring or facing serious difficulties, particularly where these difficulties produce important social problems’ (Michalek, Citation2000).

11 Source: http://www.mlekpol.com.pl/ accessed 01/03/2013.

12 Source: http://www.bialystokonline.pl/mlekpol-zarabia-i-inwestuje-w-swoje-zaklady,artykul,11230,4,66.html accessed 01 March 2013.

13 Source: http://unibep.pl/en/media-en/news/2060-topping-out-ceremony-at-the-mlekovita-construction-site.html accessed 12 December 2016.

14 Source: http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/projects/poland/mlekovita-strengthens-market-position-with-cutting-edge-laboratory accessed 01 May 2016.

15 Source: http://www.forbes.pl/mlekovita-dariusza-sapinskiego-sukces-mlekiem-plynacy,artykuly,176958,1,1.html accessed 19 June 2014.

References

- Allen, F. (2010). Opinion of the European Economic and Social Committee on the Future Strategy for the EU dairy industry for the period. Brussels, 2010–2015 and beyond. NAT/450.

- Amable, B. (2016). Institutional complementarities in the dynamic comparative analysis of capitalism. Journal of Institutional Economics, 12(1), 79–103. doi: 10.1017/S1744137415000211

- Amable, B., & Palombarini, S. (2008). A neorealist approach to institutional change and the diversity of capitalism. Socio-Economic Review, 7(1), 123–143. doi: 10.1093/ser/mwn018

- Ángyán, J. (2016). Állami földprivatizáció – Intézmémyesített földrabás. II. Megyei Elemzések: Győr-Moson-Sopron Megye.

- Appel, H., & Orenstein, M. A. (2018). From triumph to crisis. Neoliberal economic reform in postcommunist countries Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Baccaro, L., & Pontusson, H. J. (2016). Rethinking comparative political economy: The growth model perspective. Politics & Society, 44(2), 175–207. doi: 10.1177/0032329216638053

- Bakucs, Z., Fałkowski, J., & Fertő, I. (2012). Price transmission in the milk sectors of Poland and Hungary. Post-Communist Economies, 24(3), 419–432. doi: 10.1080/14631377.2012.705474

- Bartkowski, M. (2013). Imagining a Polish nation. Nonviolent resistance in Poland under partitions. In M. Bartkowski (Ed.), Civil resistance in liberation struggles. Boulder, Colorado: Lynner Rienner Publishers, Inc.

- Benedek, Z., Bakucs, Z., Fałkowski, J., & Fertő, I. (2017). Intra-European Union trade of dairy products: insights from network analysis. Studies in Agricultural Economics, 119(2), 91–97. doi: 10.7896/j.1621

- Bohle, D., & Greskovits, B. L. (2012). Capitalist diversity on Europe's periphery. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Bruszt, L., & Langbein, J. (2014). Strategies of regulatory integration via development: The integration of the Polish and Romanian dairy industry into the EU single market. In L. Bruszt & G. A. McDermott (Eds.), Leveling the playing field. Transnational regulatory integration and development (pp. 58–80). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bruszt, L., & Palestini, S. (2016). Regional development governance. In T. A. Börzel & T. Risse (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of comparative regionalism (pp. 374–404). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bruszt, L., Munkacsi, Zs, & Lundtsted, L. (in this issue). Collateral benefit: The developmental effects of EU induced state building in Central and Eastern Europe.

- Bryla, P., & Domanski, T. (2012). The fragile strength of a leading Polish yoghurt company (case study of Bakoma). British Food Journal, 111(5), 618–635. doi: 10.1108/00070701211229927

- Chloupkova, J. (2002). Polish agriculture: Organisational structure and impacts of transition. Copenhagen: The Danish Royal Veterinary and Agricultural University. Retrieved from https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/bitstream/24186/1/ew020003.pdf

- Csák, C. (2017). The regulation of agricultural land ownership in Hungary after land moratorium. Zbornik Radova Pravnog Fakulteta, Novi Sad, 51(3–2), 1125–1135. doi: 10.5937/zrpfns51-14099

- Cseszka, É., & Schlett, A. (2009). Reprivatizációtól a kárpótlásig. A Független Kisgazdapárt és a Földprivatizáció. Múltunk, 4, 92–120.

- Doner, R. F., & Schneider, B. R. (2016). The middle-income trap: More politics than economics. World Politics, 68(4), 608–644. doi: 10.1017/S0043887116000095

- Dries, L., & Noev, N. (2006). A comparative analysis of vertical coordination in dairy chains in Poland, Slovakia and Bulgaria. In J. Swinnen (Ed.), Case Studies on vertical coordination in agri-food chains in Eastern Europe and Central Asia (Vol. ECSSD Working Paper 42). Washington D.C.: World Bank.

- Dries, L., & Swinnen, J. (2007). Globalisation, quality management and vertical integration in food chains of transition countries. In L. Theuvsen, A. Spiller, M. Peupert & G. Jahn (Eds.), Quality management in food chains (pp. 423–434). The Netherlands: Wageningen University Press.

- Dries, L., & Swinnen, J. F. M. (2002). Globalisation, transition and restructuring: Evidence from the Polish dairy sector. Food policy, transition and development. Working Paper 2. Leuven: Katholieke Universiteit Leuven.

- ECJ (2018). Depriving Persons of their Right of Usurfruct if they do not have a close family tie with the owner of agricultural land in Hungary is contrary to EU Law Judgment in Joined Cases C-52/16 and C-113/16 “SEGRO. Kft. Vas Megyei Kormányhivatal Sárvári Járási Földhivatal and Günther Horváth v Vas Megyei Kormányhivatal: Author.

- FAPA (1991). Agricultural sector adjustment loan supporting volumes. Vol. 1. Warsaw: FAPA.

- FAPA (1996). Evaluation of PHARE programmes Vol. I. Main Report. Warsaw: FAPA.

- FAPA (2000). The strategic options for the Polish agro-food sector in the light of economic analyses Warsaw: Warsaw Agricultural University.

- Feffer, J. (1992). Shock waves. Eastern Europe after the revolutions Montreal: Black Rose Books.

- GAO (1995). Poland. Economic restructuring and donor assistance. Washington: US GAO. Retrieved from https://www.gao.gov/assets/160/155158.pdf.

- GATT (1992a). Trade policy review mechanism – The Republic of Poland. https://www.wto.org/gatt_docs/English/SULPDF/91660074.pdf

- Gorlach, K. (2000). Freedom for credit: Polish peasants protests in the era of communism and post-communism. Polish Sociological Review, 129, 57–85.

- Gorton, M., & Guba, F. (2002). FDI and the restructuring of the Hungarian dairy sector. Journal of East-West Business, 7(4), 5–28. doi: 10.1300/J097v07n04_02

- GVH. (2006). A Gazdasági versenyhivatal sajtóközleménye a kereskedelmi etikai kódex jóváhagyásáról. Budapest: GVH.

- Hunek, T. (1994). Reorienting the cooperative structure in selected Eastern European countries: Case-study on Poland. Central and Eastern Europe agriculture in Transition 5. Rome, Italy: FAO.

- Hunek, T., Juhasz, J., Fisher, K., & Stipetic, V. (1994). Reorienting the cooperative structure in selected Eastern European countries. Report of the Workshop. Rome: FAO.

- Jacoby, W. (2010). Managing globalization by managing Central and Eastern Europe: The EU's backyard as threat and opportunity. Journal of European Public Policy, 17(3), 416–432. doi: 10.1080/13501761003661935

- Janiuk, I. (2014). Manufacture of dairy products in Poland as an example of a fragmented industry. M: Se Slovak Scientific Journal of Management: Science and Education, 3(1), 36–41.

- Jarosz, D. (2014). The collectivization of agriculture in Poland: Causes of defeat. In C. Iordachi & A. Bauerkamper (Eds.), The collectivization of agriculture in Communist Eastern Europe: Comparison and entanglements. Budapest: Central European University Press.

- JPRS. (1990). JPRS report East Europe. Washington DC: JPRS.

- Kaloudis, A., Sandven, T., & Smith, K. (2005). Structural change, growth and innovation: The roles of medium and low tech industries 1980–2002. Paper Presented at the Low-Tech as Misnomer: The Role of Non-Research-Intensive Industries in the Knowledge Economy, Brussels.

- MAFE. (1991). Agricultural sector adjustment loan supporting volumes. Vol. II. Warsaw: The Agricultural Marketing and Processing Sectors.

- MAFE. (1995). ASAL-3000 agricultural sector adjustment programme implementation update. Warsaw: MAFE.

- Malak-Rawlikowska, A. (2006). Farm management and extension needs under the EU milk quota system in Poland. In A. Kuipers (Ed.), Farm management and extension needs in Central and Eastern European countries under the EU Milk Quota. The Netherlands: Wageningen Academic Publishers.

- Medve Bálint, G. (2014). The role of the EU in shaping FDI flows to East Central Europe. Journal of Common Market Studies, 52(1), 35–51.

- Michalek, J. J. (2000). The Europ agreement and the evolution of Polish trade policy. Yearbook of Polish European Studies, 4, 99–123.

- Mihályi, P. (2016). Discriminatory, anti-market and anti-competition measures in Hungary 2010–2015. Budapest: MTA.

- MIlk_Council (2018). Piaci helyzetelemzés. Budapest: MIlk_Council.

- Mong, A. (2012). Kádár Hitele. A magyar allamadósság története 1956–1990. Budapest: Libri.

- Nolke, A., & Vliegenhart, A. (2009). Enlarging the varieties of capitalism: The emergence of dependent market economies in east Central Europe. World Politics, 61(4), 670–702.

- Orenstein, M. A. (2001). Out of the red: Building capitalism and democracy in postcommunist Europe. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Reardon, T., Henson, S., & Berdegue, J. (2007). Proactive fast-tracking' diffusion of supermarkets in developing countries: Implications for market institutions and trade. Journal of Economic Geography, 7(4), 399–431. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbm007

- Ricard, D. (2010). Les firmes agroalimentaires occidentales a la conquete de l'Europe centrale. Les Industriels Laitiers en Pologne, Slovaquie et République Tcheque. Revue Géographique de L'Est, 50(3). Retrieved from https://journals.openedition.org/rge/3087

- Seremak-Bulge, J. (2005). Rozwoj rynku mleczarskiego i zmiany jego funkcjonowania w latach 1990–2005. Warsaw: IERiGŻ.

- Stark, D., & Bruszt, L. (1998). Postsocialist pathways: Transforming politics and property in East Central Europe Cambridge England; New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Swinnen, J. F. M., Dries, L., Noev, N., & Germenji, E. (2006). Foreign investments, supermarkets and the restructuring of supply chains: Evidence from Eastern European dairy sectors. LICOS Discussion Paper 165/2006. LICOS Center for Transition Economics. Leuven: Katholieke Universiteit Leuven.

- Szabó, M. (1999). Vertikális koordináció az Európai Unió és magyarország tejgazdaságában, Budapest: AKI.

- Szajner, P., & Vőneki, É. (2014). Structural changes in Polish and Hungarian agriculture since EU accession: Lessons learned and implications for the design of future agricultural policies. Budapest: Agrárgazdasági Kutató Intézet (Research Institute of Agricultural Economics).

- Tamás, G. (2013, December 19). Az orbáni tizenkettő – Szemfényvesztő dolgozói privatizáció. Magyar Narancs: Budapest, 51. Retrieved from https://magyarnarancs.hu/kismagyarorszag/az-orbani-tizenketto-87952#

- Tej Terméktanács, M. T. S. S. É. (2013). A magyar tejágazat helyzete és fejlődésének lehetséges iránya. Budapest: Tej Terméktanács.

- van der Meulen, B., & van der Velde, M. (2006). Modern European food safety law Safety in the agri-food chain. The Netherlands: Wageningen Academic Publishers.

- Vőneki, É., & Mándi-Nagy, D. (2014). A tejágazat kilátásai a kvótarendszer megszüntetése után Budapest: Agrárgazdasági Kutató Intézet.

- Vorley, W., Fearne, A., & Ray, D. (2007). Regoverning markets: A place for small-scale producers in modern agrifood chains? Aldershot, England; Burlington, VT: Gower.

- Wade, R. (2010). After the crisis: Industrial policy and the developmental state in low-income countries. Global Policy, 1(2), 150–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-5899.2010.00036.x

- Winiecki, J. (1997). Seven years' experience. In J. Winiecki (Ed.), Institutional Barriers to Poland's Economic Development. The Incomplete Transition. London: Routledge.

- WTO. (2000). Trade policy review Poland. (WT/TPR/S/71). Geneva: WTO.

- Zinsou, D. (1997). A la Conquete de l'Est. Comment le groupe Danone s'est implanté en Europe de l'Est des l'ouverture de ces pays. Paris: Ecole de Paris.