?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Recent mobilization against core tenets of the liberal international order suggests that international institutions lack sufficient societal legitimacy. We argue that these contestations are part of a legitimation dynamic that is endogenous to the political authority of international institutions. We specify a mechanism in which international authority increases the likelihood for the public politicization of international institutions. This undermines legitimacy in the short run, but also allows broadening the justificatory basis of global governance: Politicization allows civil society organizations (CSOs) to transmit alternative legitimation standards to global elite discourses. We trace this sequence for four key institutions of global economic governance – the IMF, the World Bank, the WTO, and the NAFTA – combining data on authority and protest counts with markers for CSOs and legitimation narratives in more than 120,000 articles in international elite newspapers during 1992–2012. The uncovered patterns are consistent with a perspective that understands legitimation dynamics as an endogenous feature of international authority, but they also show that alternative legitimation narratives did not lastingly resonate in the global discourse thus far. This may explain current backlashes and calls for active re-legitimation efforts on part of international institutions themselves.

Introduction

Contemporary world politics confronts the liberal international order with a fundamental tension. While most of today’s pressing societal challenges involve a strong transnational dimension and can hardly be tackled by individual national governments alone, extant institutions of international cooperation face increasing societal opposition in various parts of the world. The highly controversial public debates on TTIP or TPP, the partially violent protests against the International Monetary Fund (IMF) during the Eurocrisis, and especially the electorally successful populist mobilization against core tenets of institutionalized international cooperation on both sides of the Atlantic are striking cases in point. What drives these backlashes against international institutions?

Diverging national interests and economic contexts, specific incentives in domestic political competition, or the vagaries of modern political communication clearly play their part. However, this article argues that the contestation of international cooperation goes beyond the interplay of such idiosyncratic factors in contained short-term episodes. Rather, we claim, it should also be understood as endogenous to the political authority international institutions have acquired during the last decades.

Our argument builds on the premise that the exercise of authority requires justification in modern societies (Forst, Citation2007). Institutions that produce collectively binding decisions need to make credible claims on their right to rule. If these claims do not match the beliefs and standards of those governed, the institutions lose the widespread recognition they need for the effective implementation of their decisions (Cerutti, Citation2011; Parsons, Citation1960; Suchman, Citation1995). Thus, the rise of political authority is usually accompanied by permanent efforts to nurse and nurture the beliefs in its legitimacy (Weber, Citation2013, p. 450). This link between expanding authority and intensifying legitimation processes should also hold in global governance (Brassett & Tsingou, Citation2011; Tallberg & Zürn, Citation2018). We argue that it leads to patterned dynamics that should be taken into account when assessing the societal legitimacy of the current liberal international order.

We specify these dynamics as a causal mechanism that is triggered by the very transfer of authority from national to international institutions. Higher levels of international authority imply increasing societal intrusiveness of decision-making beyond the nation state. This overstretches a narrow technocratic legitimation narrative that solely resorts to effective, expertise-driven international cooperation. We thus firstly expect that upsurges in the authority of international institutions increase the intensity of de-legitimation attempts directed at them. Ceteris paribus, higher levels of authority render the societal politicization of international institutions more likely. We secondly expect that such intensifying public de-legitimation efforts involve the articulation of more demanding narratives regarding the appropriate exercise of international authority. Ceteris paribus, public politicization should increase the emphasis on fair outcomes and more open procedures of international decision-making. Yet, de-legitimation does not have to be the end point – in principle we agree that ‘liberalism contains the seeds of its own salvation’ (Deudney & John Ikenberry, Citation2018, p. 18). We thirdly expect that politicization generates more access of civil society organizations (CSOs) to discourses among global elites, rendering the transmission of alternative legitimation narratives possible. Together, we argue, these three hypotheses form a distinct causal mechanism capturing recurrent legitimation dynamics in global governance. Yet, these alternative legitimation narratives have to lastingly resonate among global authority-holders in order to prevent a widening gap between legitimacy beliefs and legitimacy claims that makes nationalist backlashes more likely.

This perspective adds to extant scholarly views on the legitimacy of international institutions in three ways. First, we deviate from the view that power shifts in the international system are the only fundamental threat that the liberal international order faces (Ikenberry, Citation2008; Stephen, Citation2014). Rather our argument emphasizes that threats to the legitimacy of international institutions also emerge from within the societies in the traditional liberal ‘heartland’. Second, we deviate from the view that international institutions can maintain favorable legitimacy beliefs solely by satisfactory institutional performance along their original mandates (Dellmuth & Tallberg, Citation2015; Keohane, Macedo, & Moravcsik, Citation2009). Rather, our argument suggests that institutional performance has to be justified against the evolving evaluative standards of those affected by this performance (Bernstein, Citation2011; Brassett & Tsingou, Citation2011). And third, our argument deviates from perspectives that defy the need for active re-legitimation by assuming that the wider citizenry is ‘rationally ignorant’ toward international politics (Moravcsik, Citation2002). Even if the citizenry is not following each and every international decision, the basic recognition that there is political authority beyond the nation state creates a latent mobilization potential. In this context, elite cues on governance beyond the nation state matter for whether this latent mobilization potential turns into fundamental opposition (Neuner, Citation2018; Schmidtke, Citation2018; Steenbergen, Edwards, & de Vries, Citation2007).

If our argument holds, solely explaining contemporary backlashes against the liberal international order with particular institutional crises or specific set-ups of domestic political competition falls too short. Understanding the dynamics and contents of long-term legitimation processes is equally decisive for the question whether favorable legitimacy beliefs about the international order can be maintained (Brassett & Tsingou, Citation2011; Tallberg & Zürn, Citation2018).

To substantiate these claims, the remainder of the article proceeds in four steps. The subsequent section theorizes the authority–legitimation mechanism in greater detail. The research design section then develops an empirical plausibility probe of the mechanism. We translate the abstract argument to the context of global economic governance. This keeps the set of legitimation demands manageable, focusses on a key pillar of the liberal international order, and allows us to compare the theorized sequence across four institutions with varying degrees of authority – the IMF, the World Bank, the World Trade Organization (WTO), and the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). We combine quantitative information on the international political authority with mediatized protest counts as a ‘tip-of-the-iceberg’ indicator for societal politicization. This is linked to the presence of CSOs and alternative legitimation narratives in institution specific discourses gathered through an automated text analysis of 128,853 articles in transnational elite newspapers between 1992 and 2012. The analysis section shows that the macro patterns in these data are consistent with a composite mechanism linking authority and its politicization to the presence of CSOs and alternative legitimation narratives in elite discourses on global economic governance. However, we also find that alternative legitimation narratives do so far not lastingly resonate in the elite discourses we analyze. This, we conclude, widens the gap between the societal need for international cooperation and the societal legitimacy of extant institutional arrangements further, contributing to the backlashes we observe.

The mechanism: authority, politicization, and legitimation dynamics in global governance

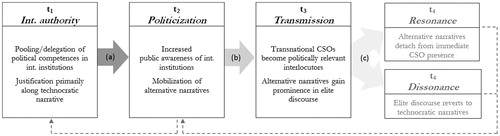

The model of legitimation dynamics proposed here distills a causal mechanism that leads from the authority of international institutions to their (de-)legitimation over time. Rather than isolating immediate bivariate relationships, mechanisms refer to ‘recurrent processes linking specified initial conditions to a specific outcome’ (Mayntz, Citation2004). Our understanding of such causal mechanisms includes both recurrent sequences of events (composite mechanisms) that put relationships between social facts in a broader context and linking mechanisms that describe the social choices leading from one macro phenomenon to the next (Bennett & Checkel, Citation2014; Bunge, Citation1997; Elster, Citation1989). The key recurring sequence in the authority–legitimation mechanism we propose is summarized in . It consists of four composite steps (t1–t4) and three links (arrows a–c) that we will discuss in turn.

Composite step t1

The rise of international authority provides the initial trigger for the mechanism we theorize. In the quest to solve particular transnational challenges, national governments deliberately create such authority on the international level. They either limit their unilateral policy options in international agreements, pool formerly national powers in majority voting procedures at the international stage, or even delegate sovereign competences to partially autonomous international institutions (Blake & Payton, Citation2014; Haftel & Thompson, Citation2006; Hawkins, Lake, Nielson, & Tierney, Citation2006; Hooghe & Marks, Citation2015). International authority emerges where actors – initially mostly governments – recognize and accept, in principle or in practice, that international institutions can make competent judgments or issue binding decisions for the affected collective of states. Authority thus refers to the deviation from individual state autonomy and it is a matter of degree. It varies with the policy scope, the bindingness of rule-setting and interpretation, as well as the depth of actual pooling and the delegation of formerly national competences in international institutions (Zürn, Tokhi, & Binder, Citation2018).

Link (a)

The more international institutions limit unilateral policies of individual governments, the broader is the set of societal interests that are directly affected by the international authority. And the more intrusive international institutions are, the more is at stake for those affected. This incentivizes more societal actors to direct their political demands towards the institutions that now hold the relevant authority. Learning processes as wells as re-orientations of material resources might be necessary before different societal interest mobilize effectively on international decision-making. But ceteris paribus, we expect that the broadening and deepening of the international authority will be followed by a growing public awareness of international institutions and an intensification and differentiation of societal demands directed at them.

Composite step t2

The resulting public mobilization of competing political preferences has been labelled as the politicization of international institutions (Zürn, Binder, & Ecker-Ehrhardt, Citation2012). Recent literature traces evidence of such increasing politicization in individual attitudes (Dellmuth, Citation2016; Ecker-Ehrhardt, Citation2012), mobilization of interest groups (Dür & Mateo, Citation2014; Ecker-Erhardt & Zürn, Citation2013; Zürn & Walter, Citation2005), national partisan competition (Hooghe & Marks, Citation2009; Hutter & Grande, Citation2014; Rauh, Citation2015), national media (Rauh & Bödeker, Citation2016; Rixen & Zangl, Citation2013; Schmidtke, Citation2018; Statham & Trenz, Citation2012), and protest events (Della Porta & Tarrow, Citation2004; Uba & Uggla, Citation2011). The authority-politicization nexus is often not direct and linear but rather mediated by specific events, policy crises, or particular national contexts (De Wilde & Zürn, Citation2012; Hooghe & Marks, Citation2009; Hutter & Grande, Citation2014). But despite mediating factors, the key point is that higher levels of international authority will – on average – make it more likely that international institutions are questioned or even contested in the public domain.

Politicization challenges the standard legitimation narrative of institutionalized international cooperation (Steffek, Citation2003, Citation2015). Traditionally, international institutions are defended in a technocratic manner: aggregate welfare gains achieved along credible intergovernmental commitments that resort to impartial coordination and unbiased expertise initially provided sufficient justification – as least as long as international institutions were based on the consent principle and mainly required legitimacy among participating governments. This justification, however, becomes quickly overburdened where international institutions hold authority on their own, thus affecting societally relevant policy choices even beyond the immediate agreement of affected national societies. Public debates involving a more diverse set of societal stakeholders widen the political community that has to grant legitimacy to international institutions, resulting in more complex standards along which international authority is evaluated (Bernstein, Citation2011; Scholte, Citation2011). With a widened audience, we particularly expect that public contestation will feature the fairness of outcomes and procedures more strongly than standards of technocratic efficiency. Public politicization will thus initially involve the de-legitimation of international authority.

Link (b)

But the exposure of alternative legitimation narratives also entails the opportunity to broaden the justificatory basis of international authority. A more widespread debate makes both more affected actors heard which enables the mutual development of political and justificatory alternatives for global choices. Yet, for this to happen the signal of exhausted legitimacy beliefs in domestic settings also needs to be received by global decision-making elites. In this respect we argue that public debates do not only create a supply of alternative narratives but also generate a demand on part of the international authority-holders. Observing public politicization, international officials should have incentives to cater to societal demands – no matter whether we conceptualize them as policy-seekers, who care about effective implementation, or as office-seekers, who care about maintaining or expanding competences (Rauh, Citation2016; Zürn, Citation2014).

Composite step t3

Yet, international institutions hardly have direct accountability chains to the wider public. The literature has rather repeatedly emphasized a key role of the organized civil society for feeding societal demands into international institutions (Keck & Sikkink, Citation1998; Scholte, Citation2004). Particularly transnationally organized groups mobilizing for causes beyond the immediate material interest of their members are seen as the major ‘transmission belt’ capable of connecting the wider citizenry with global decision-makers (Nanz & Steffek, Citation2004). Such CSOs are in the position to bundle and to aggregate various societal demands that emerge in the diverse, often national settings in which the politicization of international authority occurs. Moreover, they are able to communicate both the malpractices and achievements of international institutions back to the different audiences of modern global governance. Both characteristics together make them strategically relevant interlocutors for international authority-holders who face societal politicization (Tallberg, Sommerer, Squatrito, & Jönsson Citation2013, esp. 101–2). We accordingly expect that periods of pronounced politicization grant such CSOs greater access to international elite-level discourses. To meet the demands of their constituencies, we also theorize that CSOs will use this opportunity to actively communicate alternative standards of evaluating the legitimacy of international institutions. Accordingly fairness- and participation-based narratives should gain prominence in the discourse of international authority holders alongside stronger CSO presence.

Links (c)

Civil society organization transmission of alternative evaluation criteria to global elite discourses, however, is necessary but not sufficient for broadening the legitimation base of global governance in the long run. Re-legitimation also requires that international institutions themselves adopt and employ alternative narratives in their efforts to justify their authority. In some instances, stronger communication efforts framing institutional performance in the light of alternative standards might be a sufficient response to declining legitimacy beliefs uncovered by politicization and transmitted by CSOs. In other instances, however, policy or institutional reforms may be needed to credibly claim that the standards of narratives emphasizing fairness of outcomes and procedures are met. In any case, adapting to more complex legitimation demands is costly for international authority holders. Bearing these costs might be rational under immediate politicization pressures, but the more long-term incentives are less clear to predict. Where politicization pressures ensue for a sufficient amount of time, internalization or even persuasion regarding alternative narratives may occur. But against temporarily more contained episodes of politicization, a reversion to the traditional technocratic narrative might appear as more attractive option.

Composite steps at t4

At the final step of the sequence, thus, two outcomes are theoretically tangible which both directly feed back into the dynamic (along the dashed lines in ). Either one could expect resonance of alternative narratives. Resonance means that the discourse of authority holders lastingly features alternative justificatory standards even beyond the immediate pressures from societal politicization or CSO mobilization As such, resonance would accommodate societal mobilization potential, decrease public politicization at step 2, and thus dampen the dynamics we theorize here. Or authority holders avoid adaption cost when immediate political pressures fade and rather revert to the well-worn technocratic narrative. This, however, deepens the dissonance with the more encompassing legitimacy standards in the affected societies in the long run. It would rather reinforce and amplify the theorized mechanism. Where justificatory standards held in the affected societies get repeatedly frustrated, contestation of international authority may take more principled forms (cf. Easton, Citation1975). This strengthens those political forces that emphasize national sovereignty over international cooperation thus limiting the scope for further transfer of political authority to international institutions (cf. Hooghe, Lenz, & Marks, Citation2019, Chapter 6).

To sum up, the mechanism conceptualizes a recurrent legitimation dynamic in global governance. The pooling and delegation of formerly national political competences make the politicization of international institutions more likely. In response to public contestation, particularly transnationally organized CSOs can gain access to elite-level discourses about global governance, which enables them to transmit fairness- and participation-based legitimation narratives. To the extent that these narratives find lasting resonance in elite-level discourses, re-legitimation of international institutions appears feasible. In case authority holders do not lastingly incorporate such narratives in their legitimation efforts, however, de-legitimation through politicization will intensify further, rendering more radical opposition to international authority likely.

This sequence unfolds over time and contains endogeneity in two respects. On the one hand, the mechanism stresses that the dynamics of de-legitimation and re-legitimation are inherent to the authority of international institutions themselves. On the other hand, the final steps open up one of two feedback loops: resonance or dissonance mediate whether the theorized dynamic is dampened or becomes self-reinforcing over time. To the extent that such an endogenous legitimation dynamic is not only theoretically but also empirically plausible, explanations of the societal legitimacy of institutionalized international cooperation can neither be reduced to specific instances of domestic political competition nor to the features of the respective international institution alone. Rather, a recurrent link between international authority and a systematic broadening of legitimation demands suggests that the interaction of societal de-legitimation and re-legitimation efforts of international authority holders have to be taken seriously when assessing the prospects of institutionalized international cooperation.

Research design: tracing the mechanism in global economic governance

The empirical evaluation of causal mechanisms requires more than an analysis of the immediate relationships between input and output variables. Mechanisms rather direct attention to the sequence of phenomena that link the trigger condition to the outcome and the regularity of this sequence, thus aiming at a deeper explanation of the outcome. Evaluating the proposed authority-legitimation mechanism translates into three distinct empirical challenges. First, we want to establish that the theorized legitimation dynamics are triggered by international authority itself. This condition, however, varies only rarely for individual international institutions and we expect that it unfolds its effects only slowly over time. Second, our mechanism-based argument implies that each composite step increases the likelihood of the subsequent one. However, the theoretical discussion has also highlighted various scope conditions and complementary factors that may moderate or delay the causal relationships implied by each linking step. Third, our argument describes a long-term dynamic so that international authority, politicization, and the presence of very specific legitimation narratives in international elite-level discourses need to be operationalized consistently in a way that allows covering comparatively long-time periods.

Against these empirical challenges, our ambition is nothing more but also nothing less than a plausibility probe of the authority-legitimation mechanism (Eckstein, Citation1975). To see whether our argument bears enough empirical plausibility to warrant further attention, neither isolating the statistical effect of international authority on some measure of legitimation intensity at fixed points in time2 nor tracing the theorized sequence solely in individual case studies appears sufficient. The former approach falls short of capturing the theorized causal sequence while the latter approach falls short of showing that the theorized sequence operates regularly and across institutions. Rather, we follow the idea that the empirical analysis of causal mechanisms has to combine cross-case comparison along variation in the trigger condition with within-case inference focusing on temporal variation along the theorized sequence (Goertz, Citation2017). Specifically, we compare four international institutions that operate with comparable legitimation narratives but exhibit varying levels of authority. Then we offer systematic macro-level operationalizations of the mechanism’s four components – authority, politicization, transmission, and resonance/dissonance – that allow us to analyze their temporal variation descriptively and in a set of structural equations capturing the theorized causal pathway explicitly.

The cases: four institutions of global economic governance

Translating the abstract mechanism to a specific context, our empirical approach focusses on global economic governance. Three considerations drive this choice. First, institutional cooperation to manage economic interdependence is a cornerstone of the liberal international order as it has developed in recent decades. Second, economic governance is a particularly relevant issue area for our argument as it often resorts to technocratic management but has strong political effects by determining the resources available for distribution in various other policy domains. And third, the domain of global economic governance offers different international institutions that should exhibit comparable legitimation narratives while holding varying levels of political authority.

The transfer of political competences on economic governance to the global realm took off with the 1944 Bretton Woods conference which aimed to establish a post-war economic order that could prevent spirals of protectionism and currency-devaluations. Against the experience of the Great Depression, the negotiations revolved around enhanced international cooperation along open markets. The resulting institutions – the IMF, the World Bank, later the WTO, and regional trade agreements – have been equipped with significant political authority since then.

The IMF was originally geared to ensure the stability of the international financial system by fostering cooperation in monetary and fiscal policy. It oversaw the then fixed exchange rate agreements and provided short-term loans to countries facing imbalances of payment. Despite the collapse of the fixed-rate system in 1971, the scope of IMF activities widened significantly during the 1980s in the light of the accelerating interdependence of international money and finance (O'Brien, Goetz, Scholte, & Williams, Citation2000, pp. 161–4). First, the IMF ventured into enhanced surveillance of the international political economy. Assessing the economic performance of the world as a whole through its biannual World Economic Outlook and, more importantly, of individual governments through the Article IV consultations, the Fund nowadays issues authoritative interpretations of economic policy choices around the globe (Lombardi & Woods, Citation2008). Second, the Fund’s monetary assistance moved from short-term loans to medium- and long-term facilities geared toward structural adjustment of creditors’ economic systems. The corresponding conditionality – i.e. the policy reforms expected from countries in exchange for IMF resources – is strongly oriented along the Washington Consensus, and revolves mainly around trade and foreign direct investment liberalization, deregulation, privatization, and fiscal reform. In addition, the IMF’s efforts to avert national debt defaults in various crises such as in Mexico (1994–5), Southeast Asia (1997–8), Russia (1998), Brazil (1998), Argentina (1998–2002), and more lately Greece (2010–15), have turned it into a powerful global lender of last resort. Since IMF decisions are taken along weighted majority votes they go significantly beyond the consent of individual governments, thus expressing international authority.

Its sister organization, the World Bank,3 should originally facilitate economic growth and infrastructure reconstruction by providing capital investment loans mainly to the war-torn European countries. After the 1947 Marshall Plan, the Bank increasingly turned its attention to the developing world outside of Europe. It defined long-term economic growth and poverty alleviation as its central purposes and expanded its loan targets from physical infrastructure to other public services such as education or rural development. Particularly since the 1980s, World Bank loans are coupled with structural adjustment demands, which also focus primarily on debt reduction and liberalization along the Washington Consensus. Similar to the IMF, these decisions are based on a weighted majority voting system. And like the IMF, also the World Bank acquired epistemic authority over time. Since the early 1970s, the Bank gathers and distributes structured data, and has developed analytical expertise on national economic governance systems across the globe. While these competences grant influence over economic policy choices of individual states, the World Bank’s overall authority should be somewhat lower compared to the IMF, as its actions focus mainly on the developing world and voluntary projects.

The attempt to also establish an institution governing international trade initially failed at Bretton Woods. However, the idea was revived in 1947 with the signature of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) leading to several rounds of tariff reductions. With the Uruguay round initiated in 1986, the scope of negotiations was considerably widened also to include a broader range of non-tariff measures such as state subsidies, formerly strongly protected economic sectors such as textiles and agriculture, as well as trade in services and intellectual property rights. In 1994, this negotiation round resulted in the institutionalization of the WTO. The organization provides a framework for continued intergovernmental negotiation in regular ‘ministerial conferences’, generates and distributes information on individual countries’ compliance with trade agreements, and – most important – controls a mechanism to settle trade disputes and to enforce compensatory measures even against the will of individual governments (Barton, Goldstein, Josling, & Steinberg, Citation2008). While the WTO thus also embodies significant levels of political authority, the transfer of further competences has recently stalled. The negotiations of the Doha round are blocked mainly by quarrels over agricultural subsidies and diverging priorities of the developed and developing nations. As a consequence, additional trade liberalization has moved towards bilateral and regional agreements.

One prominent example of such agreements is the NAFTA. Compared to the other three cases, NAFTA is an international institution with comparatively little authority. It was negotiated among Canada, Mexico and the United States and entered into force in 1994. Its major goal is stimulating economic growth through increasing trade and foreign direct investment opportunities among the signatory parties. It comes with a highly detailed set of mutual obligations on trade in goods and services, investment, intellectual property rights, and it covers various non-tariff barriers for economic exchange. NAFTA limits national regulatory autonomy to some extent, has an own secretariat and also entails a limited dispute-settlement mechanism. In this sense, NAFTA is clearly more than just an international treaty (Hooghe & Marks, Citation2015). But compared to the other three institutions, the negotiators took care to regulate most relevant instances ex ante rather than allowing for pooled future decisions or actual delegation to a supranational organization (Abbott, Citation2000). In result, NAFTA’s main decision-making body, the Free Trade Commission, only acts by consensus and issues recommendations rather than binding measures while the dispute settlement mechanism resorts to external experts and is designed to limit national sovereignty to the least possible extent (ibid). Therefore, NAFTA is an international institution with a significantly lower level of authority than the other three institutions. It is a contrasting case, in which we expect the authority-legitimation mechanisms to be much less pronounced.4

Taken together, these global economic governance institutions have acquired political authority which, however, varies noticeably. The original narratives justifying the transfer of formerly national economic policy competences to these four international institutions are furthermore comparable. In all four cases, creating international authority is justified with the overarching aim to stimulate stable economic growth. This aim should be achieved through open markets with limited governmental intervention which should be guaranteed through the expertise, impartial coordination and efficient decision-making procedures that the created institutions offer. In all four instances, the initial justificatory narrative thus boils down to an expert-driven, effective management of exchange of economic resources across national borders.

The resulting international authority, however, addresses not only governments, but also touches upon ‘behind-the-border’ issues (Kahler, Citation1995). The political choices taken by or enshrined in the IMF, the World Bank, the WTO and NAFTA in fiscal and monetary, in development, and in trade policy, invariably define the budgetary and regulatory leeway of national governments. They thus constrain the distribution of resources across different societal interests. In consequence, ‘each of the international economic organizations is now involved in decision-making, which directly affects local communities, interest groups, national domestic political and economic arrangements, and also specific groups of countries’ (Woods & Narlikar, Citation2001, p. 572). Along our argument, political authority with high intrusiveness should overtax a purely technocratic legitimation narrative thus triggering the mechanism theorized above. To assess the plausibility of this mechanism, we then require indicators for its main components that are consistently available for sufficiently long periods.

Operationalizations: authority and (de)legitimation in mediatized public discourses

We base our quantitative assessment of authority on the WZB International Authority Database (Zürn et al., Citation2018). It compares the formal competences of 36 institutions between 1949 and 2012. For each of seven stages in the policy cycle, the project codes the level of authority conceptualized as an additive index of pooling and delegation, weighted by bindingness and policy scope (supplementary information Appendix A). This aggregate perspective mirrors the qualitative judgments on variation in international authority above: especially the IMF ranks comparatively high in the upper third of the distribution, where it is mainly trumped by general purpose organizations such as the EU or the UN only. Institutional WTO authority is also comparatively high while the World Bank ranks somewhat lower. We contrast these three IOs with NAFTA which only ends up in the lower third of observed authority values in the sample of 36 IOs.

Note that this measure of institutionalized authority varies only rarely over time. The major authority transfers to the IMF and the World Bank have occurred in the 1980s already, with a minor increase of IMF authority during the Eurocrisis in 2011. After its founding in 1994, authority of the WTO has increased only once with the instalment of the dispute settlement body in 1995. Likewise, as intended during the original negotiations, authority of the NAFTA has remained limited and constant since its 1994 entry into force. Thus the subsequent analyses mainly exploit cross-sectional variation and level effects of authority.

The second composite step in the theorized mechanism is politicization. Particularly the IMF, the WTO and the World Bank are relatively prominent in national media (Rauh & Bödeker, Citation2016) and in citizens’ minds (Ecker-Ehrhardt, Citation2012) when compared to other international institutions. They have also experienced contentious public debates. Especially the ‘Battle of Seattle’ during the WTO Ministerial Conference in 1999 and its continuation in the A16 protests during the IMF/World Bank meetings in Washington in the following year stand out. They are often seen as the birth of a transnational ‘anti-globalization movement’ contesting both the substance and procedures of global economic governance (Smith, Citation2001). NAFTA experienced less politicization but was confronted with civil society opposition and electoral contestation especially during its negotiation and ratification phase (Millner, Citation1997, pp. 208–12; Vogel, Citation1995, pp. 234–9).

Beyond such anecdotal evidence, our plausibility probe requires a systematic politicization indicator that is comparable over time and institutions. Politicization is a multi-dimensional concept that can be observed in the public visibility and awareness of international authority, the polarization of corresponding opinions and positions, as well as the mobilization of a broadened set of societal actors (De Wilde, Citation2011; Rauh, Citation2016; Zürn et al., Citation2012). Since there is no longitudinal data that would allow capturing all of these dimensions, our proxy resorts to mediatized protest events addressing the four institutions under analysis. Given that protests involve costly actions of a large number of individuals and require a minimum level of organization before they get mediatized, we consider this as a ‘tip of the iceberg’ measure. It systematically underestimates the overall level of politicization, but this bias should be the same for all for institutions under analysis while offering reliability over time. We retrieve respective counts of mediatized IO-specific protests from the TransAccess data set for the period 1969–2010 (Tallberg et al., 2013, p. 102) and extend the coding scheme to cover the 2011–2 as well. These data count yearly co-occurrences of keywords for protest actions in direct proximity to respective institution references in all articles in the LexisNexis ‘major world newspapers’ (MWN) file. In other words, our politicization proxy captures acts of societal resistance related to the four institutions, as they are publically reported in more than 60, primarily domestic news outlets around the world.5

Consistent indicators for the transmission of alternative legitimation narratives– the third composite step of the mechanism – are the most important, yet also most challenging pieces of empirical information we require. Our proxy for this step resorts to media sources as well. But while our politicization indicator is drawn from domestic media sources, our data collection on global economic elite discourses focuses on renowned quality newspapers with decidedly transnational audiences and an explicit focus on global economic coverage. We assume that such outlets are read by the traditional beneficiaries, proponents and authority holders of internationalized economic integration and liberalization. We consider these renowned newspapers as indicative for the elite discourses and juxtapose this elite discourse with national quality papers as indicators for a broad public discourse. To the extent that non-governmental organizations (NGOs) can place their narratives in this segmented elite part of the public sphere, they can be deemed successful in entering the debates among the holders and defenders of international political authority.

There are three additional reasons to resort to these media sources in this step. First, from the perspective of CSOs willing to hold international decision-makers to account, presence in this segment of public media is of special importance since a crucial part of the discourses between authority holders and important parts of the societal audience mostly consist of indirect encounters in mediated public spheres (Gamson & Wolfsfeld, Citation1993; Koopmans, Citation2004). Second, even where CSOs gain more direct access to international institutions, their presence in public discourses remains an asset as it signals sustained political pressure to decision-makers (Beyers, Citation2004). And, third, even if CSOs actually influence international decisions, such successes have to be communicated to establish accountability chains to the CSOs constituency and the wider public more broadly (Nanz & Steffek, Citation2004; Scholte, Citation2004).

Combining this conceptual choice with the pragmatic need to focus on English language resources that are digitally available for a sufficient amount of time, our newspaper sample contains the Financial Times (London, UK, roughly 426,000 daily copies in 2012), the New York Times (New York City, USA, 1,086,798 copies), and the Straits Times (Singapore, 365,800 copies). These newspapers are selected because they have a decidedly transnational readership, are all known widely beyond their countries of origin, represent the three economically most important world regions, share a global outreach in their reporting, operate large correspondent networks across the globe, and extensively cover international politics and business.

To put our findings into perspective, we add data from two more nationally oriented newspapers with center-left political leanings. The Guardian is based in London and sells currently about 175.000 copies a day. According to its self-description, the Washington Post is the ‘standard breakfast-time reading for members of Congress, diplomats, government officials, journalists, business lobbyists and lawyers in Washington’ and sells about 400,000 copies. These two sources serve as more domestic and politically more skeptical control group allowing us to see how different the discourses of global economic elites in the other three sources are.

From these newspapers we then manually retrieved all 128,853 articles that refer at least once to one of the four global economic governance institutions between 1992 and 2012 (supplementary information Appendix B). summarizes the article sample. The distribution shows a dominance of the Financial Times in reporting about global economic governance organizations, which can be explained out of particularly strong business focus of this outlet. Regarding the four covered institutions, the IMF receives most journalistic attention followed by the World Bank, the WTO and, way further down the line, the NAFTA.

Table 1. Distribution of newspaper articles.

Having inspected this corpus we refrain from taking the full article texts as the unit of analysis as they often deal with a variety of issues and mention the respective institution only once or twice. In order to ensure that the retrieved variables are plausibly associated with the institutions of interest, the analyses cover the immediate five-sentence context around references to one of the four institutions.

Within these text pieces we then need to capture the presence of CSOs and a references to legitimation narratives. To handle this in a text corpus of this volume we resort to a dictionary-based approach of automatic text classification. This approach sorts individual text pieces into a priori set categories based on the presence or the relative frequency of specific keywords or phrases. Like all automated content analyses, dictionary-based approaches face a trade-off between efficiency and reliability on the one hand, and the valid operationalizations on the other. Dictionary-based approaches in particular are limited to those literal language patterns that the researcher passes to the algorithm. Since we hardly can fully anticipate all ways in which a newspaper may refer to the concepts of theoretical interests, our approach is a conservative estimation of the presence of evaluative standards and actors in the debate about global economic governance. Yet, this affects all categories alike, can be assumed to be stable over time, and avoids additional assumptions of unsupervised text classification algorithms.

We tackle the validity challenge with three additional steps. First, we develop very encompassing dictionaries and flexibilize them by using regular expressions. Second, we validated and extended the individual terms and phrases in the dictionaries through an intense back-and-forth between close readings of secondary literature and individual articles in the corpus, various keyword-in-context (KWIC), co-occurrence, and co-location analyses of individual dictionary terms. Third and finally, we fully lay all used dictionaries open and set up interactive tools by which skeptical readers can assess themselves whether individual terms and phrases affect our results.6

To capture the presence of CSOs, we start from lists of all NGOs ever accredited to a WTO ministerial conference and, more importantly, all organizations in the Civil Society Database provided by the United Nations (UN) Department of Economic and Social Affairs. After extensive cleaning, our resulting dictionary contains more than 25,000 unique entries. This provides a rather encompassing representation of non-governmental groups that have ever tried to gain access to global governance institutions. A tagging script then automatically counts the occurrences of each group within the five-sentence contexts around each institutional reference in the newspaper corpus. To identify the theoretically relevant CSOs – that is, groups representing and mobilizing for causes beyond the immediate material interests of their membership – we manually classified all groups that actually appeared in the corpus to exclude other types of non-governmental actors such as business representations, unions, or think tanks (see supplementary information Appendix C for details).

To capture the presence of legitimation narratives we start from the scholarly literature of civil society mobilization on global economic governance. The concise overviews of publically articulated discontent with the four institutions provided by O'Brien et al. (Citation2000), Scholte and Schnabel (Citation2002), Della Porta and Tarrow (Citation2004), as well as Wallach (Citation2002) indeed show that civil society actors invoke fairness-based demands that stretch beyond the technocratic legitimation narrative of global economic governance. Civil society challengers doubt that the rules and measures in and by the NAFTA, the IMF, the World Bank, and the WTO are beneficial for societies as a whole. Rather, they emphasize detrimental side effects of global economic governance on environmental policies, public debt, social equality, poverty, and human rights protection. In addition, civil society mobilization against global economic governance also points to insufficient procedural justifications of international authority. Rather than judging the institutions along their effectiveness and expertise, civil society discontent addresses democratic standards and participatory narratives by criticizing biased voting rules of the IMF and the World Bank or disproportional negotiation powers of the developed countries in the WTO and the NAFTA. Corresponding demands are more equal participation, greater transparency, as well as mechanisms of societal accountability. Also in this way, civil society deviates from the technocratic legitimation narrative of international authority. summarizes these patterns of legitimation and de-legitimation.

Table 2. (De-)legitimation narratives of global economic governance.

To translate these (de-)legitimation standards into a text analysis dictionary we first automatically marked all pieces of text in which key terms of traditional justifications and main challenger demands occurred (e.g. ‘growth’, ‘social equality’, ‘expertise’, ‘transparency’). We then read a random sample of about 50 articles from this reduced corpus. This exercise indicated that relying on single terms results in an inacceptable amount of false positives (consider examples such as ‘equal market access’, ‘growth in sales’, etc.). We thus consecutively refined the dictionary in an iterative process between deriving more specific phrases from the sample texts, screen the corresponding output of KWIC analyses, re-applying the search, and then re-reading similar subsamples of the retrieved texts. This iterative procedure results in the expressions provided in supplementary information Appendix D, which we finally used to classify references to different legitimation narratives.

These measurements for the presence of both, CSOs and alternative legitimation narratives then allow us to operationalize the final two steps of the theorized mechanism. We can observe the theorized transmission (step 3) if CSOs and alternative narratives co-occur in the elite discourse after high politicization periods. And we can observe the theorized resonance (step 4) if the alternative narratives remain present in elite discourse even when the more immediate pressures of politicization and CSO activity fade away. In contrast, we would speak of dissonance if the elite discourse reverts to the technocratic narrative – especially in comparison to our control group of more domestic discourses. Taking all these indicators together, we can then assess in how far the legitimation dynamics in elite-level discourses about global economic governance between 1992 and 2012 are consistent with the theoretical mechanism developed in the theory section above.

Analysis: patterns in politicization, CSO presence and legitimation narratives

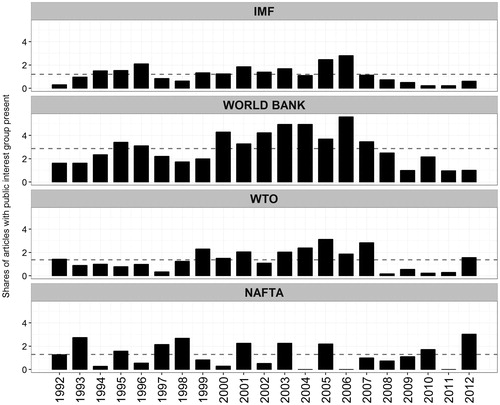

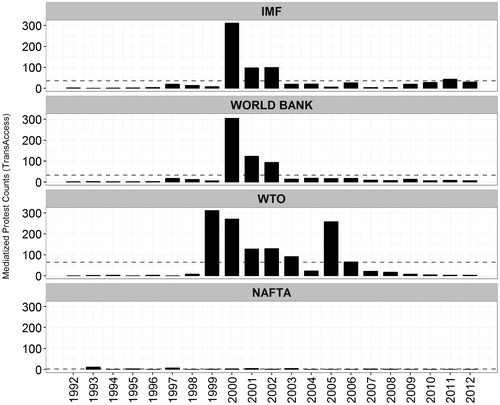

We start with a descriptive analysis of cross-sectional and temporal co-variation patterns. Link (a) in the theorized mechanism implies that more political authority of international institutions (step 1) renders the societal politicization of international institutions (step 2) more likely. Comparing across institutions, the annual investigation-period averages of mediatized protests counts (dashed lines in ) during the 21-year-period are by and large consistent with this argument. While they indicate relatively high average levels of politicization for the high-authority institutions WTO, IMF, and World Bank, mediatized protest counts for the NAFTA – the institution with the lowest level of authority in our sample – are hardly discernible in this comparison.7

Figure 2. Politicization of global economic governance institutions as captured in domestically mediatized protest counts.

Yet, we also observe sizeable variation over time. With regard to the three more authoritative global economic governance institutions, our protest data initially highlight the 1999 Battle of Seattle. The subsequent protest wave slowly levelled out until 2005 in the case of the IMF and the World Bank. The WTO – probably due to the conflicts over the deepening of the organization in the Doha round – experienced a second, but weaker episode of politicization which levelled out until 2010. Yet in none of these three cases, the mean protest level fell back to its pre-1999 levels.8 Consistent with the one-shot transfer of limited authority to the NAFTA, this institution experienced transnationally observable protest mainly in 1993 during the ratification of the original agreement.

According to link (b) in our mechanism, upsurges in such public politicization (step 2) should lead to the transmission of alternative narratives by CSOs (step 3). Politicization should thus initially be positively related to an increased presence of CSOs in transnational elite level discourse. In this regard, we initially have to note that the presence of CSOs in transnational elite-level newspapers is rather low in total. Although we look for 25.00 organizations, we detect CSO presence only in between 1.2% and 2.9% of all institution-specific articles. The sample of present CSOs is furthermore heavily skewed in favor of very few, well-endowed, and transnationally organized CSOs of Western origin (Thrall, Stecula, & Sweet, Citation2014), most notably Oxfam, Transparency International, Greenpeace, Christian Aid, and the World Wide Fund for Nature (more detail in supplementary information Appendix E).

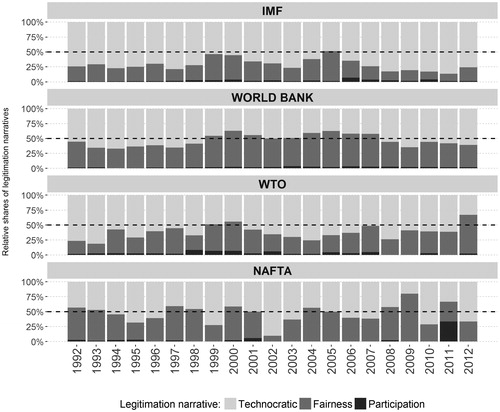

For evaluating our mechanism, however, the decisive issue is whether this CSO presence varies with the observed patterns of politicization. plots the annual shares of institution-specific articles with CSO presence. We see that the slightly enhanced protests against NAFTA in 1993 and 1997 coincide with local peaks in the presence of CSOs in respective reports published by elite newspapers. More strikingly, we observe that the high politicization period from 1999 to 2005 onwards is matched by higher CSO presence in elite-level reporting on the World Bank, but also on the WTO and the IMF. The shares of corresponding articles that made reference to a CSO almost doubles for these institutions during the period with more pronounced protest activity. This pattern is consistent with step 3 of the mechanism we propose.

But we also see that politicization works neither as the only trigger of CSO presence nor like an on/off switch. Especially in reporting on the IMF and the World Bank, some CSO presence can already be detected before the high protest phase in 1999. Moreover, politicization does not have an immediate but probably a delayed effect: presence of CSOs seems to increase slowly and, for the three more authoritative IOs in our sample, peaked between 2003 and 2006 after they had experienced a number of years with sustained politicization already. We arguably leave out a range of unobserved factors - such as the World Bank’s reliance on CSOs in project implementation, for example – but the patterns are still consistent with a positive but lagged relationship of domestic politicization and CSO presence in elite-level discourses (link b in the mechanism).

Step 3 in our mechanism (transmission), however, also requires that the presence of CSOs is also linked to an increased presence of alternative legitimation narratives. thus plots the relative share of our respective dictionary-based markers. This aggregate perspective initially confirms the expected dominance of the technocratic legitimation narrative directed at growth stimulation through efficient, expertise-driven procedures. Across the 21 years covered, this narrative accounts on average for more than 60% of the articles in which our dictionary found at least one narrative marker. The alternative fairness narrative – focusing on issues such as poverty alleviation, fair distribution of wealth, and, to some extent, environmental and human rights concerns – figures in the covered elite discourse as well, but to a much lesser extent than in our control group of more left-leaning, domestic newspapers (supplementary information Appendix G). This supports our assumption, that de-legitimation intensity is much higher in domestic debates than in the discourses of transnational economic elites. References to the participatory narrative pointing to standards such as equal representation, transparency, and accountability can be detected, too, but the overall amount of respective references is rather marginal.

For evaluating the association between politicization and the transmission of alternative narratives (link b in our mechanism), again, variation in these patterns over time is decisive. The dominance of the technocratic legitimation narrative is most pronounced for the WTO, the IMF and the World Bank before the change of the century. With increasing politicization during and after the Battle of Seattle, however the relative presence of alternative narratives becomes more pronounced as well. The fairness narrative then makes up around 50% of articles with legitimation markers. Although on a much lower level, markers for the participatory narrative in the reports on the three most authoritative global economic organizations figure only after this intense politicization period. There is still considerable fluctuation but in line with step 3 of our mechanism it should be noted that CSOs seem to matter: those years that indicate a high presence of CSOs in tend to be also the years that indicate a particularly high intensity of alternative narratives in . Across all 80 IO-years covered, the correlation between the average presence of CSOs and alternative legitimation narratives is 0.55***.

These indicators can then also be leveraged to analyze step 4 in our mechanism. Recall that we would speak of resonance if the alternative narratives remain prevalent in the elite discourse even if the short-term pressures from public politicization and CSO presence fade away. Yet, in the later years with less CSO presence, we observe a decline in the presence of alternative legitimation standards. This leads to a clear descriptive conclusion with regard to the final juncture of our mechanism: we find little evidence for an independent resonance of alternative narratives in the transnational elite discourse we cover here.

This lack of resonance is particularly striking when we compare the three transnational elite newspapers to our control group of the two more nationally oriented and center-left leaning newspapers. In the Washington Post and especially in The Guardian, both the presence of CSOs and the references to the fairness-based narrative are significantly and almost consistently higher throughout the whole investigation period and all four global economic governance institutions (supplementary information Appendix G). As such, the descriptive evidence implies that step 4 of our mechanism empirically materialized in dissonance rather than resonance. Along our theoretical argument this should intensify rather than dampen the authority–legitimation dynamics further.

But although resonance has not been happening along our measures, the evidence thus far is consistent with the first three steps of the theorized authority–legitimation mechanism. But how robust are these descriptives against the unexplained variation we observe as well? To push our analysis one step further, we finally assess the correlational relationships among our annual observations. Rather than treating authority, societal politicization, and CSO presence as independent factors explaining the presence of alternative legitimation narratives in elite discourse, however, we focus on the internal consistency of our claim and explicitly analyze a path model (Wright, Citation1921) by jointly estimating the following set of structural equations:

(1)

(1)

(2)

(2)

(3)

(3)

(4)

(4)

(5)

(5)

EquationEquations (1)–(3) model the theorized indirect effect of international authority on the intensity of alternative legitimation narratives running through politicization in the wider society and CSO presence in elite discourses. With EquationEquations (4)(4)

(4) and Equation(5)

(5)

(5) , we control for possible direct effects of politicization and authority.

Estimating such a model against the data we have is quite demanding. As noted, the authority of the four institutions varies mainly in the cross section so that EquationEquations (1)(1)

(1) and Equation(5)

(5)

(5) estimate mainly level effects and can, strictly speaking, not rule out effects of other institutional idiosyncrasies. In addition, there are no authority observations for the WTO and the NAFTA prior to 1994 so that we lose a total of four institution-years. And since we have seen above that the presence of CSOs as well as markers for the fairness-based and especially for the participatory narrative are comparatively rare events we aggregate our daily observations to the annual level and add incidences of fairness-based and participatory narratives into a common indicator for the presence of alternative legitimation narratives. We then pool the observations for the IMF, the World Bank, the WTO, and the NAFTA which leaves us in total with 80 observations available for estimation. Finally, given their skews the three dependent variables were log-transformed (supplementary information Appendix F).

Given this high level of aggregation and the fact that we cannot systematically control all factors that might impinge on protests, CSO presence and the intensity of alternative legitimation narratives, the overall low fit of this estimation is unsurprising.9 But despite a high level of noise, the theorized pathway markedly improves the explained variance over taking only bivariate relations into account.

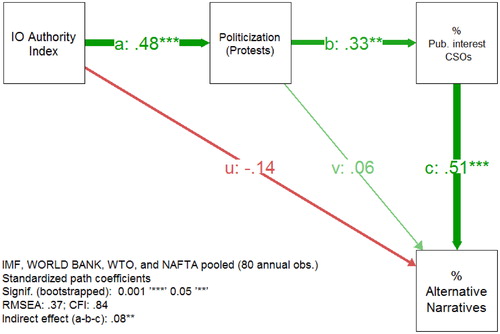

Most importantly the patterns of co-variation in the structural model plotted in are consistent with the sequential nature of legitimation dynamics we theorize. There are positive and statistically significant coefficients along the pathway with the links a–b–c that we have theorized above. A one standard-deviation increase in the IO authority index is on average associated with a .48 standard-deviation increase in our politicization proxy protest counts. One standard deviation more on this latter measure is then associated with 0.33 standard deviations more in the share of CSOs present in the elite discourse on global economic governance we cover here. One standard deviation more on this variable then is linked to a 0.51 standard deviation increase in the share of alternative narratives in this discourse. Due to the various unobserved disturbances and possibly lagged effects, the co-variances with authority become weaker throughout the path but still amount to an indirect effect of 0.08 standard deviations along a–b–c route that is statistically significant at the five percent level in our limited annual data.

Neither politicization, as culminated in protest counts, nor varying levels of authority alone can account for an increasing share of alternative legitimation narratives in transnational elite newspapers. The negative direct tendency of the authority variable supports the baseline expectation that the technocratic narrative provides the fallback option of justifying global economic governance organizations in the transnational elite newspapers under analysis.

In sum, the descriptive as well as the correlational data presented in this section are consistent with the theoretical argument that politicization and CSO presence account for an indirect, positive effect of the amount of international authority on the broadening of its justificatory discourse. Though less robust, these relationships also hold in a replication excluding the NAFTA case as the only regional institution in our sample (supplementary information Appendix H). We also find, however, that the alternative legitimation narratives transmitted by this process did so far not lastingly resonate in the elite discourse we cover here.

Discussion and conclusions

This article starts from the observation the prospects of successful political cooperation though international institutions are impaired by a current wave of pronounced political resistance in the societies they affect. Rather than treating such instances of contested global governance only as idiosyncratic and temporarily limited events, we argue that more complete explanations of these phenomena should take more long-term legitimation dynamics into account as well. Specifically, we suggest that the growing recognition of the political authority contemporary international institutions control renders the traditional, technocratic way of justifying them insufficient. This makes the societal politicization of international institutions more likely. Yet, the more complex demands articulated through this politicization do not necessarily have to lead to a lasting de-legitimation of international institutions. Where politicization amasses enough pressure, we argue, especially transnationally organized CSOs become a more sought-after interlocutor, thereby enabling them to transmit alternative narratives to the discourses of international authority holders. To the extent that these new narratives lastingly resonate, the opportunity to re-legitimate the exercise of authority by international institutions opens up.

To assess the empirical plausibility of this mechanism, we focused on four key institutions of global economic governance – the IMF, the World Bank, the WTO and the NAFTA. We scrutinize macro-level quantitative data on the institution’s authority, corresponding public protests, and the presence of CSOs and alternative legitimation markers in IO-specific reports in international business elite newspapers between 1992 and 2012. Clearly, our empirical results do not allow immediate generalization. We propose a mechanism that slowly unfolds over long time periods, we cannot explicitly control all alternative explanations at each link of the mechanism, and we look at highly aggregated data only. Yet, especially four findings in the co-variational patterns of the macro-level indicators we have scrutinized suggest that proposed mechanism is also empirically plausible enough to warrant further attention.

First, the patterns are consistent with the claim that higher international authority is on average associated with higher levels of domestic politicization. The aggregate protest counts clearly discriminate the three high-authority institutions from the contrasting low-authority case. Second, higher levels of politicization are associated with a stronger presence of CSOs in the discourses about the four institutions in global elite newspapers. We also do observe, however, that this mainly benefits a few, well-endowed groups of Western origin. Third, a higher presence of CSOs goes together with more alternative legitimation narratives in the elite-level discourse. The technocratic narrative, as present in references to the aim of stimulating economic growth through efficient and credible procedures, remains dominant in the international business press throughout the investigation period. But once CSOs gain presence in the wake of high politicization periods, markers of fairness-based narratives highlighting social justice, poverty alleviation, or environmental concerns increase as well. These findings are consistent with the endogenous legitimation mechanism we theorize, which is further bolstered by a path analysis on the annual aggregates of our data. Fourth, however, we find that alternative legitimation dynamics have not lastingly resonated in the elite discourse we study. Once protests and corresponding CSOs presence decay in the short term, the relative dominance of the technocratic legitimation narrative increases again.

In a benign reading, one may interpret this lack of resonance as a successful accommodation of societal critique by substantial changes in policy or institutional design. However, this seems implausible for two reasons. First, we do not really observe corresponding reforms during our investigation period. Once ratified, NAFTA was hardly changed at all. Reforms in the WTO essentially did not take place as evident in the failed Doha round. The IMF changed its institutional design and policies in response to the financial crisis, but too late to be seen as a response to the high politicization period. Only the World Bank enacted some reforms regarding project participation CSOs and the incorporation of environmental issues (Nielson & Tierney, Citation2003; Rodrik, Citation2006; Weidner, Citation2013). But even for this organization, doubts about these reforms remain strong (Weaver, Citation2009). Second, and more importantly, reforms or policy changes would only contribute to re-legitimation if international elites would also actually employ alternative narratives to justify international authority. This is clearly not reflected in our data, however.

In this light, our findings call for more detailed research on the final stage of the theorized mechanism: why and when do international institutions lastingly adopt alternative narratives to justify their authority (for recent efforts see Dingwerth, Schmidtke, & Weise, Citation2015; Rocabert, Schimmelfennig, Winzen, & Crasnic, Citation2018; Schmidtke, Citation2018)? Resonance of alternative legitimation narratives seems to depend on further scope conditions. We can think of three such conditions in particular. First, to the extent that resonance depends on internalization of alternative narratives on part of authority holders, the amount of time for which political pressure is sustained becomes an important variable (Checkel, Citation2005). If this is true, the current wave of political resistance against international institutions may also increase the incentives for active re-legitimation efforts. Second, adoption of alternative justifications may significantly depend on the material and strategic resources of the CSOs transmitting them (Kelley, Citation2004; Schimmelfennig & Sedelmeier, Citation2005; Tallberg et al., Citation2013). Also in this regard the current wave of politicization might induce more re-legitimation by incentivizing a broader set of groups to mobilize in favor of institutionalized international cooperation. Third, the organizational structure of the institution in authority should be conducive to learning (Reinold, Citation2017). These speculations may indeed explain why in the case of the World Bank, the resonance of alternative legitimation narratives is higher, has started earlier and has been accompanied by some reforms. The World Bank depends more strongly on cooperation with CSO networks and it is credited with a comparatively flat organizational structure that has significant reflexive capacities (Moschella & Vetterlein, Citation2016; Reinold, Citation2016).

In any case, our plausibility probe highlights that future research along these lines is theoretically and politically relevant. Contrasting the lacking resonance of alternative narratives in elite discourses, we find that in particular references to the fairness of outcomes continue to play a more prominent role in the more left-leaning, and national newspapers we have exploited as a control group (supplementary information Appendix G). While they are not internalized in global elite discourse, respective demands are still virulent and create politicization potential. This suggests that the authority-legitimacy gap has not been bridged yet.

The outcome of this mismatch is disillusioning. The evidence for a by now severe legitimacy crisis of international authorities especially in the economic realm is overwhelming. The ongoing rise of right-wing populist parties in Western democracies – among them key beneficiaries of the extant liberal order – is the most visible expression of this development. These thriving platforms have two things in common: they all emphasize popular sovereignty and share a generalized rejection of international authority. To the extent that such right-wing populist gain power or lure other parties into taking up their agenda, they effectively push back institutionalized decision making in the international realm. The Trump administration, for instance, seems to ignore the WTO completely. Similarly, many European governments equate authority with control over national borders. Even those more or less authoritarian populist leaders that govern economies that have gained or stand to gain most from open economic borders fiercely attack the international institutions in this domain for double standards and inequality. India, Turkey, and Poland are well-known examples. In this way, public politicization may hamper the further pooling and delegation of political competences in the international realm (Hooghe et al., Citation2019, Chapter 6).

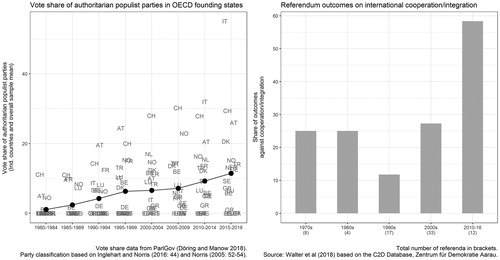

Two indicators underline this growing mobilization potential against international authority further (). The data in the left panel show the vote shares of authoritarian populist parties10 in the 20 OECD founding members, that is, states that have in principle committed to the institutions of embedded liberalism. While there is notable cross-sectional variation, we see that the electoral support is on average increasing across the last four decades in these states. Moreover, it has accelerated in the last 10 years for which our data indicate that international institutions turned again more strongly to purely technocratic legitimation patterns.

The number and outcome of referendums about international cooperation (Walter, Dinas, Jurado, & Konstantinidis, Citation2018) in the right panel of show a similar pattern. Again, the data point to increasing societal dissatisfaction with governance arrangements beyond the nation state and are indicative of a legitimacy crisis. Popular votes on international cooperation and integration have not only become more common over time but also face increasing opposition at the ballot box.

Crucially, the arguments and findings presented in this article suggest that this nationalist backlash is also related to endogenous legitimation dynamics in global governance. Beyond the need to dig deeper into the micro linkages of the mechanism we propose, the major implication of the composite argument and the patterns presented in this article is that societal resistance to international cooperation should not only be attributed to exogenous policy crises or specific set-ups of domestic political competition alone. Rather, our findings make it plausible to claim that this resistance is also rooted in the insufficient legitimation of the political authority that contemporary international institutions control.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (1 MB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Christian Rauh

Christian Rauh is a Senior Researcher in the research unit ‘Global Governance’ of the WZB Berlin Social Science Center. His work focusses on the causes and consequences of the public politicization of inter- and supranational institutions with a particular view on elites’ policy and communicative responses. More information is available at www.christian-rauh.eu.

Michael Zürn

Michael Zürn is Director of the research unit ‘Global Governance’ at the WZB Berlin Social Science Center and Professor of International Relations at the Freie Universität Berlin. He is also speaker of the Cluster of Excellence ‘Contestations of the Liberal Script’. More information is available at www.wzb.eu/en/persons/michael-zurn.

Notes

1 This work benefits from the inputs of various colleagues. We thank the participants of a series of workshops at University of Stockholm and the WZB Berlin Social Science on Legitimacy and Legitimation of IOs for excellent discussions. Moreover, the participants of the workshop “Transnational Advocacy, Public Opinion, and the Politicization of International Organizations” at the 43rd ECPR Joint Sessions of Workshops, Warsaw, April 2015, participants of the CIS colloquium at University of Zürich in May 2016, and members of WZB Global Governance Colloquium in July 2016 as well as other colleagues from the WZB have provided many helpful comments. We are especially grateful to Jan Beyers, Lisa Dellmuth, Marcel Hanegraaff, Macartan Humphreys, Ruud Koopmans, Dorothea Kübler, Daniel Maliniak, Wolfgang Merkel, Frank Schimmelfennig, Jonas Tallberg, and Mike Tierney. We also appreciate research assistance by Luisa Braig, Rebecca Majewski, Daniel Salgado-Moreno and Pavel Šatra. Replication data are available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/FZ1HZR.

2 For approaches in this vein see Schmidtke (Citation2018), Rauh (Citation2016), or Rixen and Zangl (2013).

3 When referring to the World Bank, we primarily mean the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), which is part of the now broader World Bank Group.

4 NAFTA differs from the other three cases also in with regard to its more confined geographical scope. Note, however, that this does not directly disqualify it as a comparative case for the theorized authority-politicization nexus. A smaller geographical scope also implies lower authority since a more limited set of societal actors is affected on average. Yet, one may argue that regional agreements are qualitatively different on other, unobserved dimensions. In order to ensure that our findings are not solely driven by the NAFTA case we initially present our descriptive results for each institution separately. We furthermore replicate our correlational analyses on a sample excluding the NAFTA case (see below).

5 For the full set of sources see http://w3.nexis.com/sources/scripts/grpInfo.pl?237924 (last accessed: December 9 2016)

6 Available via www.christian-rauh.eu/geg-corpus-explorer (last accessed: 05.09.2017).

7 WTO mean: 64.24 mediatized protests per year (SD: 99.2); IMF: 26.29 (68.78); WBANK: 32.19 (69.49); NAFTA: 1.85 (2.89).

8 There are some indications that the role of the IMF in the Eurocrisis and the imposition of austerity policies on the Greek government in 2015 and the following years may be the exception to this.

9 The residual variances are .75*** for politicization, .87*** for CSO presence, and .68*** for alternative legitimation narratives.

10 In identifying such parties we follow the party classifications provided by Inglehart and Norris (Citation2016, p. 44) and Norris (Citation2005, pp. 52–4) and collect the corresponding vote shares from the ParlGov Database (Döring & Manow, Citation2018).

References

- Abbott, F. M. (2000). NAFTA and the legalization of world politics: A case study. International Organization, 54(3), 519–547. doi:10.1162/002081800551316

- Barton, J., Goldstein, J., Josling, T., & Steinberg, R. (2008). The evolution of the trade regime: Politics, law, and economics of the GATT and the WTO. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Bennett, A., & Checkel, J.T. (Eds.). (2014). Process tracing: From metaphor to analytic tool. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

- Bernstein, S. (2011). Legitimacy in intergovernmental and non-state global governance. Review of International Political Economy, 18(1), 17–51. doi:10.1080/09692290903173087