Abstract

After years of placing faith in the markets, we are seeing a revival of interest in statist economic policy across the world, particularly with regards to finance. How much policy space do previously liberalized developing countries still have to renationalize their financial sectors by exerting direct control over the process of credit allocation, despite the constraints posed by economic globalization? Under what conditions do they actually use this policy space? Bolivia is an especially important case because it is one of the few peripheral countries that implemented strongly interventionist financial reform in the 2010s. Using Bolivia as a least likely case, I argue that two factors, increased availability of external financing sources, and domestic popular mobilization, create favorable conditions for developmentalist financial reform because these make it possible to reduce external conditionalities and overcome opposition by the domestic financial sector. Popular mobilizations paved the way for reform by bringing developmentalist policymakers to power and exerting pressure on them to 1. Maximize policy space by diversifying into newly available alternative sources of foreign borrowing to reduce external conditionalities, and 2. Mitigate the importance of disinvestment threats by domestic economic elites by incrementally increasing public ownership and control of the economy.

Introduction: Renationalizing finance for development

Developmentalist or activist financial policies entailing state intervention to allocate credit to strategic sectors, through tools such as interest rate controls, lending quotas, or state-owned banks, were a critical component of industrial policy and political control in postwar developmental states (Amsden, Citation1992).Footnote1 Since then, most developing countries have deregulated domestic finance, opened their capital accounts to international financial flows, surrendering credit allocation decisions to private banks, and by and large, moved away from statist models characterized by heavy public ownership and government planning, often under Structural Adjustment Program conditionalities of their external creditors, the IMF and World Bank.

In the aftermath of the 2008 crisis, the benefits of financial liberalization and deregulation have come into question, and activist financial policies to direct credit are once again being seen as vital to serving national industrial policy and climate mitigation objectives (Griffith-Jones & Ocampo, Citation2018; Mazzucato & Penna, Citation2016). Yet following over three decades of economic globalization it is not clear how much policy space, defined as ‘the flexibility of international institutions to allow sovereign states to deploy and coordinate desired policy outputs’ (Gallagher, Citation2015, p. 7), developing countries still have to conduct such policies. Under what conditions do previously liberalized developing countries renationalizeFootnote2 their financial sectors despite three main sets of constraints: the liberalization conditionalities of external official and bilateral creditors’, the preferences of foreign private investors, and the opposition of the domestic private financial sector, which may be concerned such reforms will limit its profitability?

Using Bolivia, a highly liberalized peripheral country that nonetheless renationalized its financial sector in 2013, as a least likely case, I argue that two factors, the increased availability of low-conditionality sources of external finance, and domestic popular mobilization, create favorable conditions for even peripheral countries to renationalize finance despite opposition by foreign creditors and domestic financial elites. While the supply of external financing options exogenously determines how much potential a government has to increase policy space, the balance of power between domestic financial elites, and countervailing popular sectors determines whether governments will actually increase their policy space, and also whether they are able to overcome domestic opposition to reform. Policy space is not purely exogenous, but also varies partly as a function of domestic political conditions. This paper contributes to the literatures on policy space and business power by offering a detailed causal explanation of how popular sectors can reduce both the ‘instrumental’ or political and ‘structural’ or economic power of domestic business, and increase external policy space.

Popular mobilization can bring developmentalist policymakers who represent the interests of non-elite groups to power, reducing economic elites instrumental power. Sustained mobilization then pressures policymakers to 1. Increase policy space by diversifying into alternative external financing sources to reduce vulnerability to creditor conditionalities, and 2. Reduce the structural power of domestic financial elites through a program of incremental reform that decreases the importance of the private sector in the economy and reduces the credibility of disinvestment threats. Mobilizations strengthen the hand of policymakers in enacting these incremental reforms because policymakers are able to credibly threaten economic elites with popular demands for even more radical reform.

Economic globalization and policy space

An extensive literature has debated the extent to which globalization has constrained developing countries ability to use key industrial policy tools in trade and investment (see for example Shadlen, Citation2005; Wade, Citation2003). In the realm of finance, the use of developmentalist financial policies is governed mainly by the conditionalities of external creditors.Footnote3 Balance of payments constraints have historically made late industrializing countries structurally dependent on external finance for growth (Chenery & Strout, Citation1966), and therefore vulnerable to creditor conditionalities. Constraints have intensified since economic globalization began in the 1980s, increasing pressures for convergence towards the neoliberal model. External constraints include market opening pressures from industrialized country bilateral creditors looking to promote their own financial sectors, or to ensure repayment of sovereign debt (Loriaux et al., Citation1997), or financial liberalization conditionalities from the Bretton Woods Institutions (BWIs) who represent the interests of these powerful states (Woods, Citation2006) and have increasingly become dominated by neoliberal economists (Chwieroth, Citation2007). With financial globalization, developing countries also have to contend directly with the policy preferences of private external financiers, including international financial markets and foreign direct investors, who are can ‘discipline’ governments who deviate from market oriented policies by withdrawing their investment (Campello, Citation2015; Mosley, Citation2003). The increase in capital mobility associated with globalization is thought to have increased the power of these foreign private investors, as well as domestic economic elites which may be opposed to interventionist policies (Winters, Citation1994).

A weakness in this literature is that since it focuses primarily on constraints, less attention has been paid to what factors can increase policy space. Nonetheless, one important explanation focuses on how the availability of new, low-conditionality sources of external financing enables developing countries to escape both the conditionalities of BWIs and traditional OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) lenders, as well as private market discipline. Cyclical abundance of capital inflows during boom periods caused by high international commodity prices, or highly liquid international financial markets, are seen to reduce governments’ need to attract private foreign capital, or increase government spending power, and thus widen governments’ room to reject neoliberal policies (Campello, Citation2015; Winters, Citation1994). Others point to the rise of bilateral lending by ‘nontraditional’ emerging economic powers, most importantly China, as a structural shift which has fundamentally transformed the nature and availability of foreign credit. Because these lenders eschew policy conditionalities they allow borrowers to increase policy autonomy by reducing dependence on BWIs and DAC bilateral lenders (Bunte, Citation2019; Grabel, Citation2018).

However, an increase in the supply of low-conditionality external financing does not automatically translate into increased policy space. Many countries including in sub-Saharan Africa, and South and South East Asia, benefitted from the commodity boom, excess financial market liquidity, and increased availability of BRICS financing in the 2000s, but there is great variation in the extent to which they implement developmentalist financial policies. A second weakness in this literature is that it tends to treat policy space as determined exogenously to domestic factors in developing countries.

Recent work (Bunte, Citation2019; Calvert, Citation2018) has highlighted the important role that domestic factors can play in influencing policy space. Building on this, I argue that in the realm of financial policy, the increased availability of low-conditionality external financing options opens up only the potential to increase policy space. This does not mean all governments will take advantage of these alternative financing sources to reduce the conditionalities they are subject to and increase the actual policy space they have, i.e. the conditionalities they are subject to by external creditors at a given moment. Many countries have the option of borrowing from BRICS lenders, but prefer instead to take IMF or DAC loans in order to lock in liberal reforms, or send positive market signals to foreign investors (Bunte, Citation2019). Similarly, policymakers also have to take strategic action to capture a greater share of commodity revenue, for example, through increasing royalties on, or outright nationalization of, resource producing MNCs. Otherwise conditionality free foreign exchange earned from the export of commodities will flow directly to the coffers of MNCs where it can be repatriated to headquarters.

While potential policy space depends on the exogenously determined supply of external finance, and is outside the borrowing governments’ control, within these bounds, governments do have some room to manipulate their external environments in order to negotiate access to new sources of finance and increase their actual policy space. Domestic factors are crucial in explaining why some governments maximize their actual policy space, while others do not. Domestic factors also explain why some governments are able to use the policy space they do have to implement their preferred policies against domestic opposition, while others fail to overcome these domestic barriers despite having the requisite policy space from external constraints.

Domestic explanations for policy space

Ideational accounts highlight the importance of key policymakers’ normative beliefs in determining how they perceive the costs and benefits of violating international agreements for developmental purposes (Calvert, Citation2018). In finance, a ‘neo-developmentalist’ ideational consensus that finance should be subordinated to the needs of the productive economy through centralized state control (Thurbon, Citation2016, pp. 47–65), as opposed to policymakers who believe financial liberalization is economically beneficial, should lead governments to diversify into conditionality free financing sources where possible, so that they can implement the domestic policies they favor. While policymakers’ ideologies are undoubtedly important, because liberal policymakers would have little interest in interventionist policies, policymakers’ orientations are likely to reflect the interests of those who brought them to power (Bunte, Citation2019; Calvert, Citation2018). We need to explain why developmentalist policymakers came into power in the first place, and why they were able to actually implement their preferred policies against domestic or external opposition in some periods, but not in others. Similarly, explanations that explain noncompliance with international agreements through regime type or voter preferences (Rickard, Citation2010) neglect that domestic economic elites effectively have a ‘second vote’ on the policymaking process due to their control of the economy (Fairfield, Citation2015, pp. 17–20) While electoral motives undoubtedly inform policymakers’ priorities, these do not tell us why some policymakers are able to overcome domestic opposition to popular policies from economic elites, while others are not.

The financial liberalization literature points to domestic finance as a key interest group pushing for financial liberalization and deregulation (Loriaux et al., Citation1997; Pepinsky, Citation2013). Developmentalist financial policies are likely to face opposition from the domestic private financial sector, if they limit its profitability, or increase risk, while being championed by favored priority sectors (Haggard & Maxfield, Citation1993). The financial sector not only opposes diversification into BRICS external financing but also prefers IMF loans because these lock in reforms it considers beneficial (Bunte, Citation2019).

According to an extensive business politics literature, the ability of governments to impose their policies against business preferences depends on the extent of the mutually reinforcing structural and instrumental power of business elites vis-à-vis the state (Culpepper, Citation2015; Fairfield, Citation2015). In contrast to instrumental power which includes deliberate action to influence policy-making and depends on factors such as personal relationships with/access to policymakers, and degree of concentration and cohesion within sectors, which reduce collective action problems in lobbying (Fairfield, Citation2015, p. 2), structural power results from the economic position of a firm or sector. Owners of capital control the investment decisions on which the economy depends for growth, and can destabilise the economy through reducing investment or relocating capital abroad (Culpepper, Citation2015, p. 396; Winters, Citation1994, p. 430). If policymakers anticipate that a reform will provoke reduced investment or capital flight, they may rule it out for fear of harming growth and employment, or disinvestment following reform may force policymakers to backtrack (Fairfield, Citation2015, p. 2). The private financial sector is generally considered to have the most structural power due to its mobile nature (Winters, Citation1994), and because it has a high number of linkages to almost all other sectors of the economy through its lending, which means that decisions to reduce lending have both direct and indirect effects on economy-wide investment (Woll, Citation2014).

Popular mobilization, state action, and business power

Mass mobilization by non-elite groupsFootnote4 is an overlooked factor in the structural power literature, and can help account for variation in business power. According to the literature, non-elite groups such as labor unions or social movements can only act as a countervailing force against business instrumental power through providing attractive potential for electoral mobilization, lobbying by labor groups, or strike action, but because they do not own capital, they cannot challenge business’ structural power (Culpepper, Citation2015; Fairfield, Citation2015). Yet the Bolivian case shows that non-elite groups can be important in counteracting not only instrumental, but also structural power. Countervailing popular sectors can reduce business power in at least three ways: First, they can reduce instrumental power through promoting electoral victory for developmentally oriented parties that represent nonelite groups, which can sever instrumental ties between business and policymakers. Electoral legitimacy also makes it harder for business associations to mount successful public campaigns against government policies. Second, sustained mobilization can pressure policymakers to weaken business structural power through a program of incremental reform that decreases the importance of the private sector in the economy and reduces the credibility of disinvestment threats. Finally, mobilization strengthens the hand of policymakers in negotiations with business because policymakers are able to threaten economic elites with popular demands for even more radical reform, and because these threats are seen to be more credible when they come from a government with electoral legitimacy.

Renationalization of finance in Bolivia

Against the vehement opposition of domestic private banks and BWIs, the left wing Movimiento al Socialismo (MAS) government of Bolivia not only re-established state-owned banks, but also implemented the Financial Services Law (FSL 393) in 2013, constituting a drastic reversal of decades of liberalization policies. The new law intervened in credit allocation decisions of private banks through instituting lending quotas to a list of ‘productive sectors’,Footnote5 and limited profitability by capping interest rates. This was done without offering compensation, making it one of the most strongly interventionist financial policies in comparative terms, short of bank nationalization.

Existing literature on globalization and state autonomy predicts that reversal of liberalization reform is only possible for industrialized core economies that make the rules of the international economic system (Naqvi, Henow, & Chang, Citation2018), and to a lesser extent for large emerging markets that have the resources to assert themselves in global financial governance (Woods, Citation2006). The Bolivian case is puzzling when compared to the handful of other previously liberalized developing countries that have also seen a recent increase in financial activism, because these are either key emerging markets like Brazil and Korea, or countries that are so isolated from the international system like Ethiopia, that we would expect them to face less constraints.Footnote6

Bolivia on the other hand is a least likely case for heterodox reform both in terms of its domestic political economy and its position in the international economy. Like most developing countries, Bolivia followed a statist model during the 1960s and 1970s, until the 1980s debt crisis (Conaghan et al., Citation1992). Since then, high external indebtedness and continued dependency on international financial institutions for financing investment resulted in shock treatment more extreme than in comparator countries. (Kohl & Farthing, Citation2009, p. 66). ‘Big-bang’ financial liberalization, including liberalization of all interest rates in 1985, opening of the capital account, and privatization and closure of state owned banks through the 1980s and 1990s, resulted in an open, highly dollarized, and predominantly privately owned financial system by the early 2000s (Morales, Citation2003). These reforms empowered private finance by increasing its ownership and control over resource allocation, and created strong vested interests in favor of maintaining the liberalized status quo. This made reversal less likely in Bolivia than in countries that had experienced less extreme liberalization.

On the international level, as a lower middle-income country with a small internal market, Bolivia has a peripheral position in the international economy and little bargaining power in the institutions of global governance. Bolivia entered the 2000s heavily externally indebted, with open capital accounts, WTO membership, and a bilateral investment treaty (BIT) with the US – a party to various institutions of global economic governance, but with no voice in shaping their rules according to its domestic priorities. Bolivia therefore provides an excellent case in which to analyze the factors that enable previously liberalized peripheral countries to conduct heterodox economic policies that go against international norms.

Neither the increase in the supply of external finance, nor the presence of developmental ideology among policymakers can by themselves the pattern and timing of developmentalist financial reform in Bolivia (). In period 1, increased availability of low conditionality sources of external finance from the early 2000s opened up potential policy space for Bolivian policymakers, but because private business elites had strong instrumental and structural power over the government, policymakers did not translate this into actual policy space by diversifying external finance sources to reduce conditionality, nor were they interested in financial reform. In period 2, popular mobilization lead to the election of a developmentalist government with ties to non-elite groups, reducing business instrumental power by severing its ties with policymakers. However, policymakers were constrained from undertaking radical financial reform at this stage due to fears of disinvestment and capital flight. Business structural power remained strong due to continued private ownership of productive assets. Under sustained pressure from its support base, policymakers pursued a strategy of simultaneously 1. Increasing policy space by negotiating access to new sources of BRICS financing and increasing royalties on hydrocarbon MNCs and 2. Reducing the structural power of the private financial sector by undertaking a program of incremental economic reform that reduced the importance of disinvestment threats. This reduction of structural power caused business elites to become sectorally divided, further reducing finance’s instrumental power, and paving the way for reform in period 3.

Table 1. Three period within-case comparisons.

Research design and methods

A three time period within-case comparison is employed in order to understand how key variables (external financing, popular mobilization, and business power) differ across time periods. The periods before Evo Morales election, his first term, and his second term, provide a natural periodization according to key business power independent variables. Within rather than cross-case analysis was chosen because it permits intensive investigation of a particular outcome, and holds constant a number of background conditions and factors that are not central to my analytical framework including bureaucratic quality, regime type, and ethnic conflict. Process tracing was conducted in each of the time periods in order to establish how the change in independent variables prevented or led to the dependent variable (financial reform). The conclusion extrapolates from the Bolivian case in order to demonstrate the broader importance of the findings for other countries, as well as other types of external financing and outlines avenues for future research.

The analysis draws heavily on 52 in-depth, semi structured interviews conducted during fieldwork in La Paz and Santa Cruz between 06/03/17 and 26/03/17, and a number of follow up conversations, in order to understand the preferences of each actor, as well as their role in the negotiation process. Interviewees were involved first hand in designing drafting, negotiating, implementing, or monitoring the FSL 393, and included high level policymakers and technocrats at government ministries, central bankers, public bank managers, financial regulators, ratings agencies, politicians from governing, and opposition parties, bureaucrats at the international financial institutions, representatives from business associations from the private sector, from finance, industry, agriculture, and commerce, and senior management from large private banks large agribusiness firms. See Appendix 1 for a full list. Interviews were triangulated with articles in local business newspapers, confidential government and private sector negotiation documents given to the author by interviewees, publicly available documents from the government, BWIs, and ratings agencies, and quantitative data.

The negotiation of the FSL 393 and its effects

The Vice Ministry of Pensions and Financial Services at the Ministry of Economy and Public Finance (henceforth Ministry of Finance) began drafting the new financial sector law in 2012. The private business associations ASOBAN (Association of Private Banks of Bolivia), representing large commercial banks, ASOFIN (Association of Entities Specialized in Microfinance), representing microfinance banks, and CEPB (Private Business Confederation of Bolivia), the peak private sector business association, were called to the negotiating table at the Committee of Planning, Economic Policy, and Finance of the Deputies (Interviews 1–5, Ministry of Finance; 17, former ASOBAN). The FSL393 was debated and passed through the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies in June 2013, and promulgated in August 2013 (La Razon, Citation2013).

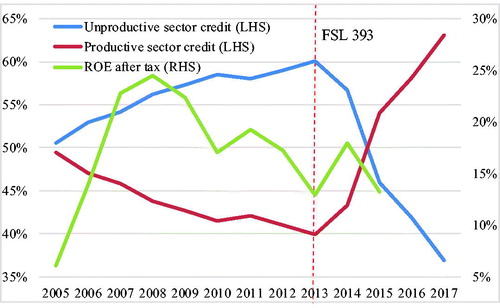

The Ministry of Finance came out the clear winner in the negotiations. The private banks were vehemently opposed to the FSL 393 and associated Supreme Decrees, because these measures were expected to reduce the extraordinarily high bank profits made between 2005and 2013 (), and reduced banks’ autonomy of decision making over credit allocation. From the banking sector’s perspective: ‘You could say in a way the banking system in Bolivia has been nationalized. They tell you where to lend to, at what rate. The private shareholders barely get anything and they are angry’ (Interview 17, former ASOBAN).

Table 2. Major financial sector reforms under MAS, 2006–2014 and their effect on banks.

Even though banks were given till 2018 to comply with their quotas, the FSL 393 had immediate and drastic effects on the distribution of credit and reduced bank profitability (). This shows that the FSL completely reversed of decades of financial deregulation not only formally, but also substantively. Under what conditions was such a transformative financial sector policy possible for the MAS government?

Period 1. (2000–2006): commodity boom, strong business power, and popular mobilization

During this period domestic business was both structurally and instrumentally powerful, and despite an increase in popular mobilization resulting in electoral gains for the left-wing developmentalist MAS party, a pro-market coalition continued to dominate the state apparatus. In this context, despite the commodity boom increasing potential policy space, the government did not diversify its financing sources, and developmentalist financial reform was not implemented despite calls for intervention.

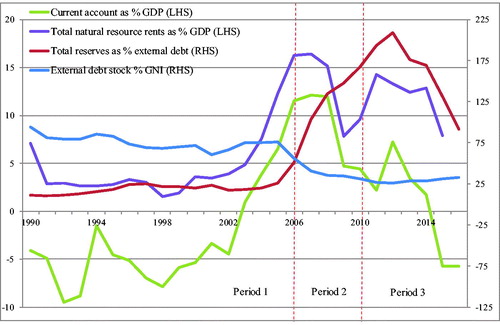

Although Bolivia entered the 2000s highly dependent on external creditors due to continuous current account deficits () two developments on the international level presented it with the opportunity to pursue a more independent economic policy. The commodities boom began in the early 2000s, resulting in the first current account surplus in decades in 2003 (). Beginning in 1998, the HIPC campaign for Bolivia led to a significant debt cancellation by the IMF and World Bank in 2005,Footnote7 which decreased both external debt stock and service (Weisbrot & Sandoval, Citation2006).

Because domestic business elites continued to exercise a high degree of instrumental and structural power, policymakers did not take advantage. Bolivia remained under an IMF Stand-By Arrangement (SBA), in which financial sector conditionalities included privatization of the remainder of publicly held banking assets, including the development bank Nacional Financiera Boliviana (NAFIBO) and Banco Union, a commercial bank which had become insolvent and was nationalised in the early 2000s (IMF, 2005a, p. 16; Interviews 27–30, Banco Union, 31, BDP).

Bolivia’s economy remained dominated by a small number of large domestic private firms in agribusiness, industry, and finance, and foreign multinationals in hydrocarbons (López, Citation2001). These sectors had significant structural power over the government due to their important contribution to GDP and exports (). The rest of the economy consisted of micro enterprises with little economic importance or political voice (López, Citation2001).

Table 3. Bolivian economic structure.

The government was particularly reliant on traditional land owning agribusiness elites, located in the most economically important department of Santa Cruz department (). Santa Cruz business elites represented their interests to the government through the well-organized regional association, FEPSC (Santa Cruz Federation of Private Entrepreneurs), and sectoral associations CAINCO (Santa Cruz Chamber of Industry and Commerce), CAO (Eastern Chamber of Agriculture), and CADEX (Santa Cruz Chamber of Exporters) (Eaton, Citation2011; Fairfield, Citation2015). The leading strata of this business class were organized into family owned economic groups (Orellana, Citation2016; Salmon, Citation2007, pp. 172–174), whose core interests lay in agribusiness, but had diversified into banking and other commercial activities after the late 1960s (Salmon, Citation2007, p. 167).

The liberalized, predominantly private, bank-based financial system was highly concentrated, with the largest five commercial banks holding the most structural power due to their domination of the financial system with over 70% of bank deposits (ASFI, Citation2005). One of the largest banks was foreign owned, and one state owned, and the rest are partially owned by family economic groups from Santa Cruz, La Paz, Sucre, and Cochabamba (Eju, Citation2011), implying a confluence of financial, agribusiness, and other commercial interests (). In 2003, out of partially dollarized economies, Bolivia ranked second in the world (Morales, Citation2003, p. 9) with over 90% of deposits and 97% of loans in US dollars (IMF, 2006, p. 29). The highly profitable microfinance sector, which was growing rapidly during the early 2000s, had high foreign ownership, but was not economically important, making up only 7% of total credit and deposits, and lending mainly to informal sector firms (IMF, 2006, p. 16).

Table 4. Market share and ownership of large Bolivian commercial banks.

Since 1985, despite divisions existing along both regional and sectoral lines, business elites exercised strong instrumental power through pervasive ties to Bolivia’s traditional parties, which dominated the state apparatus (Fairfield, Citation2015, pp. 228–230), especially through the CEPB, which aggregated the interests of regional and sectoral associations, and historically played a key role in national politics (Eaton, Citation2007, p. 88; Fairfield, Citation2015, p. 226). The banking association ASOBAN was highly influential in the government, especially at the central bank and Ministry of Finance, where it was regularly consulted on financial policy due to its perceived technical expertise (Interviews 1–5, Ministry of Finance; Interview 21, Former Central Bank; 17 Former ASOBAN). Key government positions were filled by technocrats such as former CAF economist and World Bank consultant Luis Carlos Jemio as the Minister of Finance, and orthodox economist Juan Antonio Morales as the President of the central bank, who did not have direct links to, but were held in high regard by the financial sector.

During this period, the financial system was criticized for a lack of long-term real economy lending, especially to the industrial and affordable housing sectors, and for medium and small sized agribusiness firms, and for profiting instead from providing consumer finance at high interest rates, and fees based activities (Interviews 1–5 Ministry of Finance, 13, ASFI). The non-financial private sector lobbied in favor of reviving public banking, prompting the Ministry of Economic Development to prepare a plan to recreate a state-owned development bank (Morales, Citation2005; Interview 21, former Central Bank). However, as a result of the financial sector’s structural and instrumental power, interventionist plans were not implemented, and market based solutions favored instead (IMF, Citation2003, 2005). For example, in a 2005 presentation, Juan Antonio Morales stated that the solution to lack of real economy lending is not the re-establishment of state owned banks, but to enforce better contracts through strengthening the rule of law (Morales, Citation2005).

Popular mobilization and the rise of MAS

From the late 1990s onwards, in the context of growing dissatisfaction with Bolivia’s economic disparities, BWI conditionalities, and exclusionary social structure, popular mobilization increasingly acted as a countervailing force against business elites’ instrumental power (Fairfield, Citation2015, p. 230). Although pro-business governments remained in power during this period, popular protests against BWI sponsored water and hydrocarbon privatization escalated into violence between 2000 and 2005 and led to repeated crisis and leadership changes. The challenge came from a broad coalition of peasant, indigenous, and urban middle class voters, which coalesced into a support base for the indigenous-left MAS party, led by Evo Morales, which was the only popular party able to articulate mass grievances (Molina, Citation2010).

Period 2 (2006–2009): increased policy space, weakened instrumental power and strong structural power of finance

Popular mobilization brought the developmentalist MAS party to power in 2006, reducing the instrumental power of business. Under pressure from its non-elite support base, the developmentalist government diversified into alternative forms of external finance and increased hydrocarbon royalties to remove external constraints to reform. However, the strong structural power of domestic business remained unchanged from period 1, due to continued private ownership of productive assets, and credible threats of capital flight and financial instability. This dissuaded policymakers from enacting drastic financial reform. Under sustained popular pressure, the government began using the favorable external environment to increase the importance of public investment, de-dollarize, and accumulate reserves, in order to reduce business structural power by mitigating the importance of disinvestment threats.

Popular mobilization, electoral victory, and developmental policymakers

The massive popular mobilization finally resulted in the historic victory of the MAS party in the December 2005 elections (Molina, Citation2010), and gave Morales the political legitimacy to appoint developmentalist policymakers to key positions at the most important economic ministries, including the Ministry of Finance, the Central Bank, and the financial regulator, ASFI (Financial System Supervisory Authority). Industrialization, and promotion of higher value added exports were seen as vital to achieving sustained improvements in living standards for the MAS support base. To this end, the new developmentalist ‘Economic-Social-Communitarian-Productive’ model, with an active role for the state, was established, in sharp contrast to the old ‘neoliberal model’ (Ministry of Development and Planning, Citation2007, henceforth Ministry of Planning; (Ministry of Finance, Citation2015, p. 11). Multinational hydrocarbons companies and new domestic industrial SOEs were seen as the main agents of development, the former to generate foreign exchange, and the latter to generate domestic employment and demand, with little role for the domestic private sector (Ministry of Planning, 2007; Interviews 6–7, Ministry of Finance; 12, Former Ministry of Productive Development and Plural Economy, henceforth Ministry of Development).

In 2006 Morales appointed Luis Arce Catacora, former central banker under the academic influence of the left-wing economist Carlos Villegas,Footnote8 as Minister of Economy to show the MAS support base that the party was serious about economic change. Key policymakers in the Ministry of Finance were of the view that left to the market mechanism, credit would flow to profitable but unproductive sectors, and that in order for the financial sector to perform its role in servicing the productive sectors of the economy in the new model, strong state control would be necessary (Interview 1–6 Ministry of Finance; Interview 8, Central Bank). According to officials in the Ministry of Finance ‘Our vision was to guide the financial sector through directing credit towards productive sectors unlike the old law which was oriented towards the commercial and services sectors’ (Interview 1, Ministry of Finance).

Strategic use of international financing

Unlike their predecessors, the MAS government seized the opportunity for greater policy autonomy presented by the commodity boom and availability of funds from nontraditional lenders in order to translate potential into actual policy space. BWI conditionalities were widely blamed for declining living standards by MAS’s popular support base, and had triggered the protests of the early 2000s (Kohl & Farthing, Citation2009). The MAS’s anti-IMF electoral campaign linked slow growth and declining living standards to the lack of national economic sovereignty (Movimiento al Socialismo [MAS], 2005a), necessitating urgent action on the government’s part once it came to power. Senior officials at the Ministry of Finance, Planning, and Development ministries, and the Central Bank also believed that removal of IMF and other external conditionalities was a perquisite to delivering on important campaign promises, including improved working conditions, which would require transitioning to a new development model (Interview 1, Ministry of Finance; 10 Ministry of Planning; 12, Former Ministry of Development; 8, Central Bank; Ministry of Planning, 2007, pp. 242–258).

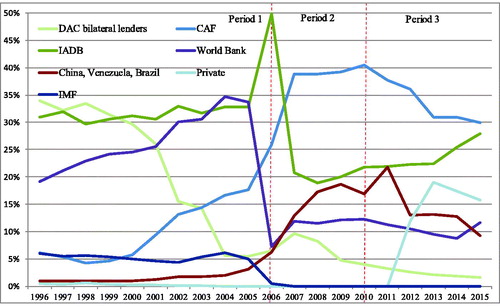

The MAS government increased taxes on hydrocarbon MNCsFootnote9 in 2006 to enjoy a vastly greater share of booming commodity rents than would have been the case under previous taxation regimes. The government then used these resources strategically to abandon the standby agreement (SBA) with the IMF, releasing it from the attached conditionalities (Interview 10, Ministry of Planning; 12, Former Ministry of Development). The Ministry of Planning began a program of replacing traditional financing sources, namely IMF and World Bank loans and bilateral loans from DAC creditors, with finance that came with fewer conditionalities, including loans from the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB) and Andean Development Corporation (CAF) and bilateral loans from China, Venezuela and Brazil (Interview 10–11, Ministry of Planning; 12, Ministry of Development; ). Later, Bolivia further diversified into private external finance through issuing government debt on the international bond markets in 2012 and 2013 (Mitchell, 2013).

Instrumental power of business

Business’s instrumental power was greatly reduced after MAS won the election, as elites found their institutional and personal connections to the incoming executive and top policymakers severed (Wolff, Citation2016). This loss of instrumental power was not absolute: MAS did not win control of the Senate in the legislative election, which made passing controversial laws difficult, although not impossible.Footnote10 Furthermore, elites mounted a regionally and sectorally cohesive opposition. Santa Cruz agribusiness elites escalated demands for regional autonomy, with the conflict even escalating to the brink of civil war in 2008 (Eaton, Citation2007, Citation2011; Molina, Citation2010). Financial elites, and the La Paz elite, although not directly part of the autonomist movement, were allied with it due to hostility towards the government, especially as a result of proposed wage and tax increases (Interview 14, CEPB).

Although lower on the agenda of the MAS support base than issues such as wage and hydrocarbons policy, financial reform had become a salient issue, as high interest rates in microfinance fuelled perceptions that the banks were exploitative. This led MAS to pledge that it would establish a public development bank to provide subsidized credit to small and micro enterprises during its 2005 electoral campaign (MAS, Citation2005b). Particularly important in fuelling anti-finance sentiment were high rates on mortgage loans in the midst of a housing shortage in La Paz, where an important middle-class section of MAS’s support base was located (Interviews 32–5, Ratings agency). This also led the Ministry of Finance to include construction on the list of productive sectors, as it was hoped this would contribute to increasing the supply of houses (Interviews 1 Ministry of Finance).

Once Arce was appointed to the Ministry of Finance, the contrast in instrumental power that ASOBAN enjoyed was marked in comparison to previous administrations. According to a former Central Bank employee:

When I was in the Central Bank in 2005 in the previous administration, ASOBAN had a lot of power over our policies… For example, once we increased reserve requirements for USD deposits in April 2005. ASOBAN disagreed and told us this would be catastrophic. So we immediately made the terms more generous, the increase more gradual. After Arce came to power everything changed, he wouldn’t accept the attitude of ASOBAN (Interview 21, former Central Bank)

According to private bank representatives, Arce in was particularly hostile towards the industry, ‘Arce doesn’t trust the industry… All conversations start with the fact we are making too much money, that we are not fulfilling our social function’ (Interview 25, Foreign commercial bank). The financial sector claimed that the Arce administration targeted banks in order to increase political capital among supporters ‘His [Arce’s] point of view is that the banking sector is a good way to make political gains because were in a socialist state and doing things against the rich people and private sector is politically good’ (Interview 23, Private commercial bank). However, ASOBAN was constrained in their ability to lobby publicly against Arce’s policies due to the popular support the MAS party enjoyed: ‘ASOBAN couldn’t do anything because Morales… won the [2005] election by 54%, which hasn’t happened since the 50 s. He came with strong political support and that changed the dynamics for ASOBAN, who had supported the opposition parties’ (Interview 21, former Central Bank).

Structural power of business

Despite MAS’s electoral victories, both financial and real sector business elites, especially those located in Santa Cruz, continued to hold significant structural power, as most of the economy remained under private control (Eaton, Citation2011; Fairfield, Citation2015; Webber, Citation2008).

On the one hand, pressures from their support base, and new real-sector oriented development strategy meant that policymakers no longer feared reduced bank profitability, since finance was not considered a priority sector in and of itself Furthermore, policymakers wanted to discourage lending to sectors they considered unproductive in any case, so the consequences of disinvestment in these areas were not seen to be that great (Interviews 1–5 Ministry of Finance).

On the other hand, although policymakers’ ideologies and perceptions were clearly important to structural power, material conditions continued to constrain them. Even though interviews with key architects of the FSL 393 at the Ministry of Finance confirmed the financial reform had been on their agenda from day one, the economic conditions that characterized the first years of MAS government were such that policymakers feared passing a controversial financial reform would cause capital flight by bank depositors, which in turn would cause bank runs, and disrupt domestic economic activity, as well as put pressure on the currency. According to a Ministry of Finance official: ‘Our first goal was to provide stability, then after that we could do what we wanted… in 2006 the populationFootnote11 was scared that because we were a left government this would cause financial instability. They were scared that what would happen in Argentina [in 2001] would happen… But the idea was always to direct credit’ (Interview 1, Ministry of Finance). According to a former ASOBAN representative, the day after Morales was elected ‘he visited officially the banking association – why? Because he was a populist candidate who just won the election and he didn’t want the banks to bleed in terms of deposits. He said he realises the banks are important for the economy and we aren’t going to do anything that will put in danger the deposits of the public’ (Interview 17, former ASOBAN).

Extremely high levels of dollarization compounded financial fragility for two reasons. First, under dollarization, the central bank’s ability to act as lender of last resort is constrained by extent of its dollar reserves (IMF, Citation1999). Second, capital flight in the form of withdrawal of dollar deposits exerts pressure on the dollar liquidity of the banking system and therefore on central bank reserves (IMF, Citation2003, p. 19, 2005b, p. 16). Capital flight was also expected to put downward pressure on the currency, which if devalued would result in an increase in the value of external debt, which was denominated in hard currency (Interviews 1–4 Ministry of Finance; 8, Central Bank).

Bolivia’s long history of struggling with business elites moving capital abroad in response to domestic uncertainty (Conaghan, Citation1992, p. 7) made the Ministry of Finance wary. Due to high-income inequality, large private companies or wealthy individuals held almost 60% of total deposits in 1% of deposit accounts, mainly in US dollars (IMF, 2005b, p. 16), (ASFI, Citation2005, p. 6). This made the Bolivian banking system particularly vulnerable to bank runs caused by these large depositors moving their dollars abroad (IMF, 2005b, p. 16). The Ministry of Finance was also cognizant that depositors were anxious about the security of their deposits under a leftist government, as Bolivia’s previous leftist government had frozen dollar deposits and converted them to local currency in 1982, in response to high inflation (Interviews 1–4 Ministry of Finance; 8, Central Bank). Repeated banking crisis through the 1990s and early 2000s, including runs on bank deposits as recently as 2002 and 2004 (IMF, 2005b, p. 12), as well as Argentina’s recent experience with the corralito in 2001Footnote12 brought back these traumatic memories (Interview 8, Central Bank; IMF, Citation2003, p. 15).

Foreign investors were a secondary concern for Ministry of Finance officials, and played a role in moderating the reform agenda. While the government did not wish to attract foreign investment into the financial sector, foreign direct investors in other sectors, mainly in hydrocarbons, were important, and the government had plans to diversify into private borrowing on international financial markets. According to Ministry of Finance officials outright bank nationalization was not considered as a serious policy option because of the negative spillover effects it would have on foreign investors (Interview 1–5, Ministry of Finance; 17, Former ASOBAN).

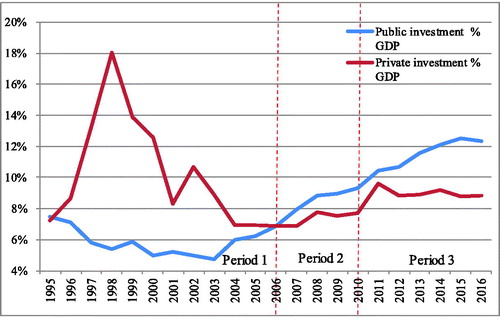

A number of policies were put in place by the government over this period that gradually decreased the structural power of both financial and real sector business, laying the foundations for passing the FSL in 2013. Commodity revenues were channeled via the Central Bank into newly established SOEs, which took the lead in designated strategic industries (Interviews 6-7 Ministry of Finance). This decreased the structural power of the private sector because the government became less reliant on them for investment (; Ministry of Finance 2012).

The Central Bank took advantage of the commodity boom to embark on a successful program of de-dollarization to decrease financial fragility and regain control of monetary policy, while the beginning of a period of high economic growth boosted the health of the banking system by decreasing the risk of loan default (Interview 8, Central Bank; WDI, World Bank). External debt to GDP ratios continued falling, and the central bank built up vast foreign exchange reserves, reducing the negative impact potential capital flight could have on the currency and external debt (; Interview 8, Central Bank). Frustrated by the private banks’ lack of real economy lending, the Ministry of Finance reversed the planned privatizations of the largely inactive remaining public banks, instead increasing their capital with funds from the treasury, and began using them to compensate for lack of private finance (Interview 31, BDP; 27–30 Banco Union). In 2007, NAFIBO was re-established as second tier development bank Banco Desarrollo Productivo (BDP), and the commercial Banco Union took on a new role as the government’s ‘model bank’, setting low interest rates and increasing lending to productive sectors (Interviews 27–30, Banco Union).

Period 3 (2010–2014): Reduced structural power: From conflict to an unstable coalition

The interventions undertaken in period two gradually created the material conditions for the passing of the FSL 393 in period 3 through increasing actual policy space and reducing the structural power of domestic real and financial elites. The beginning of the period of high global liquidity in international financial markets after 2009, due to quantitative easing and low interest rates in the US and other advanced economies further increased the availability of low cost and conditionality foreign capital to developing countries, and reinforced the boom in commodity markets (Akyüz, Citation2017). Plentiful global liquidity, build-up of foreign exchange reserves, reduction of external debt, and domestic de-dollarization mitigated the threat of capital flight. After 2009, the political landscape also shifted significantly in MAS’s favor, when the autonomist right became increasingly discredited after a series of strategic mistakes, including an alleged assassination plot against Morales (Reuters 2009). MAS won a landslide victory in the December 2009 election, with Morales re-elected with over 60% of the vote, and a two-thirds majority in both houses of the legislature (La Razon, Citation2016), leading to further declines in business instrumental power.

This structural and instrumental weakness resulted in elite division, as it prompted Santa Cruz elites to calculate that forming an alliance with the MAS government, and supporting financial reform was in their long-term interests. The government was interested in reconciliation because it realized that when the commodity boom reached its end, it would once again need the agribusiness sector to invest and generate foreign exchange (Interviews 12, Ministry of Development; 8, Central Bank; 14, CEPB; 17, Former CEPB). This alliance reduced the remaining instrumental power of finance, and further allayed policymakers’ fears of capital flight, enabling the government to finally implement the FSL 393 in 2013, ten full years since the start of the commodity boom.

External constraints

The IMF and World Bank were not consulted before the FSL 393 was passed (Interview 45 World Bank; 46, IFC), and have been publicly and privately critical (45 World Bank; 46 IFC; 20 ASOFIN). A 2015 IMF report on the FSL 393 warns of the financial stability risks credit quotas and interest caps pose (Heng, Citation2015), while the 2014 IMF article IV Consultation argues that the law will actually reduce total lending, and recommends more market friendly measures to attain financial inclusion goals (IMF, Citation2014). However, the Ministry of Finance, no longer being a borrower, could afford to ignore this criticism: ‘from 2006 the opinions of IMF were against everything we did, so we didn’t care about them… Even if they are right we’re not going to listen to them’. (Interview 5, Ministry of Finance). According to one former Ministry of Finance interviewee, an example of this was when the Ministry of Finance noticed that the housing banks were unable to meet their social housing lending quotas, and so considered lowering the quota. However, before they did so, the IMF independently suggested the same thing. Because they did not want their support base to see them as listening to the IMF, the Ministry of Finance decided not to lower the quota (Interview 5, Ministry of Finance).

The private ratings agencies, Moody’s, Standard and Poor’s, Fitch, and Fitch’s Bolivian subsidiary, AESA Ratings, had indicated they would react very negatively to the FSL 393 (Interviews 32–35, Ratings Agency), and followed up by downgrading some individual banks, citing increased financial stability risks. However, this was not a major consideration for the Ministry of Finance, since there was no foreign exchange shortage at the time due to the boom in international financial and commodity markets, the government’s growth strategy did not rely on attracting foreign or new private investment into the financial sector, and Bolivian banks no longer funded themselves abroadFootnote13 (Interviews 1–5, Ministry of Finance; 9, Central Bank). While banks were downgraded, Bolivia’s sovereign rating remained unaffected. In late 2012, Bolivia even began issuing sovereign bonds on the international capital markets for the first time in almost a century, which allowed it to tap in to yet another source of low-conditionality foreign capital (). Despite its heterodox policies, these issues were massively oversubscribed (Kilby, Citation2012) indicating that in the midst of a financial boom capital inflows were forthcoming regardless of domestic policy. MNCs in other sectors came with finance from their headquarters, or home country banks, and therefore had little stake in the domestic Bolivian financial system and did not mount strong opposition to financial reform (Interview 19, ASOBAN).

Business preferences and power

Real economy business elites. Policymakers succeeded in further reducing structural power as the share of public investment continued outpacing private investment (), and due to the commodity boom, MNCs and state controlled hydrocarbons had far overtaken agribusiness as the main contributor to value added and exports, putting Santa Cruz agribusiness elites in a relatively weak position (). According to the CEPB, because private sector was seen as less important for investment and job creation, their input was not considered important for making key economic decisions ‘They see us as very secondary. They think the primary engine of the economy is the state… if we invest… then they have to invite us to the table for many key decisions, and they don’t’ (Interview 17 CEPB).

During the FSL negotiations ASOBAN and ASOFIN had launched a concerted offensive to try to convince the rest of the private sector that it was in their interests to present a united front against the reforms, or intervention would spill over into their sectors too. (Interview 17, Former ASOBAN). However, this strategy was met by limited success, and ASOBAN felt that their negotiating position was weakened because of this (Interview 18, ASOBAN). Although real economy elites remained opposed to the MAS government due to wage and tax increases, they began to perceive that the MAS government had the upper hand due to its economic power and electoral legitimacy, especially its second term, and that accommodation might be a better long-term strategy. According to a representative of CEPB ‘The private sector wasn’t able to put up against the FSL because the government is so powerful because of how much they won in the elections… So you cannot argue with them. It’s a very strong government for Bolivian standards. They control all three branches, executive, two thirds of congress, and the judiciary. And because of commodity boom they didn’t need the private sector’ (Interview 14, CEPB). As a result, real economy business elites either took no clear position on the FSL, or supported it, undermining elite cohesiveness ().

Table 5. Preferences of business associations with regards to the FSL 393.

In particular, the powerful Santa Cruz business associations, FEBBSC, CAO, CAINCO, and CADEX, supported the FSL prior to its passingFootnote14 (Interviews 1-5 Ministry of Finance; 15, FEPSC). They calculated that in the longer run, given their structural and instrumental weakness, they would be better off in an alliance with the government, rather than with the financial sector, even though the FSL 393 had both costs and benefits for their businesses. On the one hand, since some Santa Cruz family groups owned shares in the banks (), any reduction in banking profits or increase in risk would impact them directly (Interviews 23 Private bank; 15 FEPSC). On the other hand, their core agribusiness was the main beneficiary of the FSL, since these firms were among the least risky borrowers, leaving banks scrambling to lend to them to fulfil their productive sector quotas (Interviews 19, ASOBAN; 23–25, Private banks; 16, CAO). Furthermore, supporting the government in financial reform would bring concessions in areas more important to their core agricultural businesses, including a nonretroactivity clause exempting existing agricultural holdings from land reform, legalization of deforestation and removal of limits on exports of foodstuffs (Interviews 15, FEPSC; 16, CAO; 22, CAINCO).

Structural power of finance. The Ministry of Finance’s initial FSL proposal had included a higher 70:30 ratio of productive sector lending, lower productive sector interest rate caps, as well as caps for unproductive sector loans (Interviews 5, Ministry of Finance; 17, ASOBAN). During a negotiations between the Ministry of Finance and ASOBAN, the banks claimed that reduction in their profits would lead to a decline in credit in the medium to long-term, and harm the poor the most. They also threatened to shut down their operations if the FSL 393 was approved, and used the arguments from the 2014 and 2015 IMF reports to support their claims (Interviews 19, ASOBAN; 23-25, Private banks; 32–35 Ratings agency).

The Ministry of Finance did not take these threats seriously because the danger of capital flight by bank depositors no longer preoccupied Ministry officials (Interview 5, former Ministry of Finance). Now that foreign exchange reserves were plentiful, dollarization was at a historical low, and bank balance sheets were healthy (Heng, Citation2015, p. 13), Ministry of Finance officials were reassured that the reform would not cause mass capital flight. These fears were further allayed by the alliance with key Santa Cruz business elites, which were among the largest depositors. Although one of the major banks was foreign owned and threatened to leave Bolivia in 2013, two factors prevented them. Firstly, it was difficult to find a buyer given the recent FSL announcement, and secondly, due to the booming economy, their venture in Bolivia was still relatively profitable compared to failed ventures in Columbia, and limited operations in Chile and Panama (Interview 25, Foreign private bank). The other most politically important universal banks were mainly domestically owned, which meant that they had no easy exit option. Some microfinance institutions were owned by foreign conglomerates, such as Banco los Andes, which did sell their Bolivian operations following the FSL, these were not considered important to the functioning of the financial system by the Ministry of Finance as they were lending mainly to informal, unproductive firms, at exploitative interest rates, and so did not constitute a credible disinvestment threat (Interviews 1–5, Ministry of Finance; 20, ASOFIN). Importantly, increased public ownership in banking through the BDP and Banco Union meant that the government could compensate declines in private lending, making its economic consequences less consequential. Arce exploited demands for bank nationalization from mine workers, cooperatives, and peasant farmers in order to frame the FSL 393 as a compromise solution (Interview 1-5 Ministry of Finance; 14, former ASOBAN. Banks considered nationalization a credible threat, due to the strong support the MAS government enjoyed from its radical support base (Interview 25, Foreign commercial bank).

Some minor concessions were made to the banks so that profitability would not become unsustainably low, as policymakers feared this could lead to financial instability. The 70:30 productive lending quota was lowered to 60:40, interest rate caps were lifted by two to three points, and unproductive loans were left uncapped. A later concession was the inclusion of the construction, tourism, and intellectual property sectors in the productive sector category to ease pressure on banks in meeting their targets (Interviews 5, Ministry of Finance; 17, ASOBAN).

Fallout from the FSL 393 and lower commodity prices (2014–2018)

As intended by policymakers, the industrial, agribusiness, and construction sectors have been the main beneficiaries of cheaper bank credit (ASFI, Citation2018, p. 10), but it is still too early to assess whether the FSL is achieving its stated developmental aims. Despite the predictions of private bankers and the IFIs, the FSL 393 did not result banking or currency crisis due to mass capital flight, or foreign banks disinvesting. Instead total credit to the private sector grew at an average rate of 12% per year between 2013 and 2018 (ASFI online database, https://www.asfi.gob.bo.; Heng, Citation2015). Private banks have accommodated themselves to the FSL despite lower profitability, and the alliance between the MAS government and agribusiness elites remains intact. So far no strong demands for reversal of the FSL 393 have emerged (Interview 22, CAINCO; Interview 50, former Ministry of Finance).

The end of the commodity boom since 2014 raises questions about the sustainability of this reform. Since commodity prices have fallen, a current account deficit has emerged, external indebtedness is increasing, and FX reserves are declining. However, at the time of writing, the sheer scale of reserves accumulated the boom has meant the economy has not yet felt the full impact of low commodity prices (Kehoe, Machicado, & Peres-Cajías, Citation2019). From 2014, the government has been compensating for declining commodity revenue by increasing foreign borrowing, and by encouraging domestic private investment through their alliance with agribusiness (Interview 14, CEPB). At the same time, popular forces have become co-opted by the government and de-mobilized (Farthing, Citation2019), which means they may not be as strong a countervailing force if business power increases again. This means that as reserves run low, the private sector could regain economic and political power and may reverse financial reform.Footnote15 Furthermore, external imbalances could eventually lead to a balance of payments crisis unless adjustments are made. If this necessitates an IMF program, then interventionist reform could be reversed under IMF conditionality, even if the domestic financial sector remains weak. On the other hand, if the new financial regulation builds up a significant support base, including among real economy business, then reversal may not occur even in the face of adverse external or domestic circumstances.

Discussion and conclusion: Bolivia in comparative perspective

Bolivia benefitted from two factors, which enabled it to increase external policy space and reduce domestic business power to re-assert state control over a previously liberalized financial sector, despite the opposition of both the IMF and domestic business: plentiful external finance and domestic popular mobilization. The following sections provide a brief sketch of contrasting cases in order to provide insights into prospects for similar action in other countries.

The arguments made here should travel to the broader set of developing countries that are resource rich, and thus have access to resource rents during boom periods. It should also apply to the even wider range of countries that have access to nontraditional loans from emerging powers, including Sub-Saharan African, and Latin American countries where China has increased investments, and a number of South and South East Asian countries, especially as China’s Belt and Road Initiative gains in importance. An important finding from the Bolivian case is that the supply of alternative external financing options only determines potential policy space. Whether this is translated actual policy space is mediated by domestic political factors, highlighting that external financing constraints are partly endogenous to domestic political factors. Not only do developing countries need to have access to outside financing options, they also need to use these strategically to reduce conditionalities associated with traditional creditors. This implies that resource rich countries where popular mobilization is absent, resulting in the sector remaining predominantly privately or foreign owned, and not heavily taxed, will not necessarily experience an increase in policy space even during boom times. Neither will countries that have access to outside financing options, but do not use them to move away from BWI and DAC lenders.

Even if actual policy space is increased through successful manipulation of the external environment, governments must also use these favorable external conditions strategically to reduce the structural power of domestic finance in order to implement reforms that they are opposed to. In this regard, comparison with other Latin American ‘pink tide’ countries like Ecuador where governments broke instrumental ties to private finance and also benefitted from the commodity boom, would be a fruitful avenue for future research, even though outside the scope of this paper. For example, the structural power of domestic finance could explain why similar attempts to intervene directly in private banks’ sectoral lending decisions by the developmentalist Correa administration in Ecuador were unsuccessful, even though it had successfully increased its external policy space by diversifying into BRICS financing sources (Bunte, Citation2019), and increasing taxes on oil exporters (Calvert, Citation2018, p. 91). Continued dollarization left the financial sector vulnerable to capital flight, similar to Bolivia in period 2, and forced the Correa administration to drop the sectoral lending targets that were present in an earlier draft of the September 2014 Monetary and Financial Code as a compromise with banks (Economist Intelligence Unit, Citation2014).

To what extent do the arguments made about commodities revenue and South-South finance also apply to other forms of investible external finance? While foreign aid usually comes with conditionalities, countries that are important to donors from a geopolitical perspective should be able to leverage their position to obtain a steady flow of funds, while avoiding conditionalities, as Korea did with US aid during the Cold War era (Woo-Cummings, Citation1991, pp. 6–7). Booms in access to external private finance in the form of portfolio flows or bank loans are often conflated with commodity booms in the literature, even though commodity exports produce revenue while private financial inflows produce debt. Heavy dependence on portfolio flows might have distinct implications for policy autonomy. Because downturns inevitably result in capital outflow, reliance on private capital flows could result in financial crisis, necessitating a return to traditional lenders and consequent structural adjustment. Similarly, when foreign reserves are built from portfolio inflows rather than export surplus (‘borrowed reserves’), this increases external liabilities, and leaves the country more vulnerable to capital flight than reserves figures suggest (Akyüz, Citation2017).

Findings from the Bolivian case have important implications for the viability of state-led growth strategies under economic globalization. These are difficult to implement, because developing country governments are constrained not only by official and private international creditors, but also domestic economic elites. On the other hand, though external constraints are strong, they are not constant, and vary at least partly as a function of domestic political conditions. Furthermore, popular mobilizations can reduce not only elite instrumental power, but also structural power, if they exert sufficient pressure on policymakers.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (113.6 KB)Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Ngaire Woods, Robert Keohane, John Ikenberry, Diego Sanchez Ancochea, Sylvia Maxfield, Tom Hale, Florence Dafe, Jose Peres Cajias, Linda Farthing, and the participants of the Global Leaders Fellowship Colloquium at Princeton University for comments on earlier drafts of this paper. Special thanks also go to Edwin Rojas Ulo, Peter Knaack, Bismarck Averecilia, Pablo Mendietta Ossia, and Sara Shields, without whom conducting fieldwork would have been impossible. All views expressed in this paper are the authors’ own.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Natalya Naqvi

Dr. Natalya Naqvi is Assistant Professor in International Political Economy at the Department of International Relations at the London School of Economics. She was previously a postdoctoral research fellow at the Global Economic Governance Program at Blavatnik School of Governance, Oxford University and the Neihaus Center for Globalization and Governance, at the Woodrow Wilson School, Princeton University. She holds a PhD from the Centre of Development Studies, University of Cambridge. Her research interests revolve around the role of the state and the financial sector in economic development, and how much policy space developing countries have to conduct selective industrial policies despite the constraints posed by economic globalization.

Notes

1 Existing studies on the effectiveness of developmentalist financial policy show it has been successful in some cases, but not in others (see Griffith-Jones & Ocampo, Citation2018; Heng, Citation2015; Staking, Citation1997). This paper examines the conditions under which these policies are implemented, but the question of their effectiveness is outside its scope.

2 By renationalization I mean policies that assert national public control over the domestic financial sector to guide resource allocation according to domestic policy priorities. I do not necessarily mean the nationalization of private banks, although historically this has been one of the main tools used to guide credit.

3 Because industrial policy tools in the areas of finance, trade, and investment, are governed by different sets of international arrangements and face different domestic constraints, policy space is likely to be specific to the policy instrument used and the regime that governs it.

4 Nonelite groups are defined as those that do not own or manage capital.

5 These include industrial manufacturing, agriculture and agribusiness, and extraction and processing of metals, minerals, and natural gas. ‘Unproductive sectors’ are broadly services sectors including wholesale and retail (IMF, 2015).

6 A number of countries, including China, India, Vietnam, and Nigeria, continue to pursue varying degrees of activist financial policy, but are not included in the analysis because they never seriously liberalised in the first place.

7 and the IADB in 2007.

8 Villegas was one of the key architects of the National Development Plan (PND).

9 While often termed a nationalization, the 2006 hydrocarbons reform did not involve changes in ownership.

10 The government can however pass reforms as ‘Supreme Decrees’ rather than laws to bypass parliament.

11 The official refers not to non-elite groups but capital owners and the professional upper middle classes

12 The Argentinian government froze all bank accounts in order to stop capital flight and converted US dollar deposits to pesos.

13 External financing was high in the 1990s but came down to 1.6% of bank liabilities in the 2000s (ASFI, Citation2005, p. 9).

14 CAINCO and FEPSC sent a letter stating their agreement with the FSL, prior to final negotiations (Interviews 1–4, Ministry of Finance).

15 This scenario appears to have materialized in the coup of November 2019, although it remains to be seen how long the unelected government representing Santa Cruz elites will last, and what their attitude towards financial policy is.

References

- Akyüz, Y. (2017). Playing with fire: Deepened financial integration and changing vulnerabilities of the global south. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Amsden, A. H. (1992). Asia's next giant: South Korea and late industrialization. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ASFI. (2005). Analisis del Sistema Financiero a Diciembre 2016. Retrieved from https://www.asfi.gob.bo/index.php/analisis-del-sistema-financiero.html.

- ASFI. (2018). Cartera de Creditos al Sector Productivo. Retrieved from https://www.asfi.gob.bo/images/INT_FINANCIERA/DOCS/Publicaciones/Credito_Productivo.pdf.

- Bunte, J. (2019). Raise the debt: How developing countries choose their creditors. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Calvert, J. (2018). Constructing investor rights? Why some states (fail to) terminate bilateral investment treaties. Review of International Political Economy, 25(1), 75–97. doi:10.1080/09692290.2017.1406391

- Campello, D. (2015). The politics of market discipline in Latin America: Globalization and democracy. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- CEPB. (2013). Ley de Bancos: Propuestas y lineamientos. Propuesta de política pública – UAL. Retrieved from http://www.cepb.org.bo/wpcontent/uploads/2017/01/LineamientosParaUnaLeyDeBancosPropuestaPoliticaPublica.pdf.

- Chenery, H. B., & Strout, A. (1966). Foreign assistance and economic development. American Economic Review, 56(4), 679–733.

- Chwieroth, J. M. (2007). Testing and measuring the role of ideas: The case of neoliberalism in the International Monetary Fund. International Studies Quarterly, 51(1), 5–30. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2478.2007.00437.x

- Conaghan, C. M. (1992). The private sector and the public transcript: the political mobilization of business in Bolivia (Vol. 176). Notre Dame, Indiana: Helen Kellogg Institute for International Studies, University of Notre Dame.

- Culpepper, P. D. (2015). Structural power and political science in the post-crisis era. Business and Politics, 17(3), 391–409. doi:10.1515/bap-2015-0031

- Eaton, K. (2007). Backlash in Bolivia: Regional autonomy as a reaction against indigenous mobilization. Politics & Society, 35(1), 71–102. doi:10.1177/0032329206297145

- Eaton, K. (2011). Conservative autonomy movements: Territorial dimensions of ideological conflict in Bolivia and Ecuador. Comparative Politics, 43(3), 291–310. doi:10.5129/001041511795274896

- Economist Intelligence Unit. (2014). Ecuador's new monetary code takes effect with revisions EIU Financial Services. Retrieved from http://www.eiu.com/industry/article/1122267296/ecuadors-new-monetary-code-takes-effect-with-revisions/2014-09-10.

- Eju (2011). 21 Grupos corporativos son dueños de la banca en Bolivia. Eju Tv. Retrieved from http://eju.tv/2011/08/21-grupos-corporativos-son-dueos-de-la-banca-en-bolivia/.

- Fairfield, T. (2015). Private wealth and public revenue. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Farthing, L. (2019). An opportunity squandered? Elites, social movements, and the government of Evo Morales. Latin American Perspectives, 46(1), 212–229. doi:10.1177/0094582X18798797

- Gallagher, K. P. (2015). Countervailing monetary power: Re-regulating capital flows in Brazil and South Korea. Review of International Political Economy, 22(1), 77–102. doi:10.1080/09692290.2014.915577

- Grabel, I. (2018). When things don't fall apart: Global financial governance and developmental finance in an age of productive incoherence. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Griffith-Jones, S. and Ocampo, J. A. (Eds.). (2018). The future of national development banks. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Haggard, S., & Maxfield, S. (1993). Political explanations of financial policy. In S. Haggard, C. Lee, and S. I. Maxfield (Eds.) The politics of finance in developing countries. New York, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Mazzucato, M., & Penna, C. C. (2016). Beyond market failures: The market creating and shaping roles of state investment banks. Journal of Economic Policy Reform, 19(4), 305–326. doi:10.1080/17487870.2016.1216416

- Naqvi, N., Henow, A., & Chang, H. J. (2018). Kicking away the financial ladder? German development banking under economic globalisation. Review of International Political Economy, 25(5), 672–698. doi:10.1080/09692290.2018.1480515

- Heng, D. (2015). Impact of the New Financial Services Law in Bolivia on Financial Stability and Inclusion. Working Paper No. 15/267. Washington DC: IMF. doi:10.5089/9781513598420.001

- IMF. (1999). Monetary Policy in Dollarized Economics. IMF Occasional Paper 171, Retrieved from https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/nft/op/171/.

- IMF. (2003). Selected Issues and Statistical Appendix. Retrieved from http://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2016/12/30/Bolivia-Selected-Issues-and-Statistical-Appendix-16818.

- IMF. (2005a). Bolivia: Sixth Review Under the Stand-By Arrangement. Retrieved from http://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2016/12/31/Bolivia-Sixth-Review-Under-the-Stand-By-Arrangement-and-Requests-for-Modification-and-Waiver-18682.

- IMF. (2005b). Bolivia: Ex-Post Assessment of Longer-Term Program Engagement. Retrieved from http://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2016/12/31/Bolivia-Ex-Post-Assessment-of-Longer-Term-Program-Engagement-18210.

- IMF. (2006). Bolivia: Staff Report for the 2006 Article IV Consultation. Retrieved from http://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2016/12/31/Bolivia-Staff-Report-for-the-2006-Article-IV-Consultation-19472.

- IMF (2014). Bolivia: Staff Report for the 2013 Article IV Consultation. Retrieved from http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/cat/longres.aspx?sk=41310.0.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadistica, INE online database. Retrieved from https://www.ine.gob.bo/index.php/estadisticas-por-actividad-economica.

- Kehoe, T. J., Machicado, C. G., & Peres-Cajías, J. (2019). The Monetary and Fiscal History of Bolivia, 1960–2017 National Bureau of Economic Research. Working paper No. W25523.

- Kilby, P. (2012). Rare Bolivia Bond Market Issue Surprises Market. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/bonds-bolivia-latam/rare-bolivia-issue-surprises-bond-market-idUSL1E8LO6RG20121024.