?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

According to the literature on economic development, the upgrading of core state institutions is the sine qua non of promoting growth and development in lesser-developed countries. The European Union (EU) is the first transnational integration regime that has experimented with measures to upgrade core state institutions. It did so in the pre-accession period of the would-be member states in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE). In this paper, we empirically explore the developmental effects of the EU-induced upgrading of the judiciary, bureaucracy and competition authority in CEE countries. We base our analysis on two new datasets: one on the quality of foreign trade and the other on institutional reform measures of the judiciary, bureaucracy and competition authority. Our main finding is that EU-induced upgrading of core state institutions, especially the judiciary, significantly improves developmental outcomes. In the post-accession period, however, the European Commission has only a weak capacity to enforce EU-wide norms that can guarantee the quality of these core state institutions. The lack of enforceable standards on the quality of core state institutions undermines the effectiveness of EU policies aimed at achieving economic convergence.

Introduction

The positive developmental effects of upgrading core state institutions like the judiciary, bureaucracy and competition authority are one of the few issues for which economists, political scientists and sociologists can together sing songs of praise. The scholarship exploring the relationship between these core institutions and economic development has a long tradition in the social sciences (Evans, Citation1995; Evans, Rueschemeyer, & Skocpol, Citation1985; Tilly, Citation1975). Economists have also extensively explored the role of these state institutions in shaping developmental outcomes (Acemoglu, Aghion, & Zilibotti, Citation2006; Acemoglu, García-Jimeno, & Robinson, Citation2015; Besley & Persson, Citation2009, Citation2011; Koyama & Johnson, Citation2017). Pioneers in the study of the middle-income trap also stress that upgrading the judiciary, bureaucracy and competition authority is a precondition for altering developmental paths (Acemoglu et al., Citation2006; Aghion, Akcigit, & Howitt, Citation2013; Doner & Schneider, Citation2016). Finally, state capacity is one of the key explanatory variables in research projects that explore pathways away from the (semi-)periphery (Bohle & Greskovits, Citation2012; Gereffi & Wyman, Citation1990).

These approaches differ in their starting premises and methods of inquiry. As a common starting assumption, however, they all reject the idea that the growing transnationalization of markets reduces space for domestic actors to shape developmental outcomes. The capacity of states to produce various public goods is a crucial aspect of economic development. What those necessary public goods are and, consequently, what sort of capacities states need to enhance growth, are contested issues. Some stress the need to have a judiciary or bureaucracy with the capacity to enforce property rights or to create a predictable policy environment (Acemoglu et al., Citation2006, Citation2015). Others emphasize the importance of state capacity to discover, explore and exploit the available room for development and further innovation, or to help economic actors solve collective action problems (Doner & Schneider, Citation2016; Evans, Citation1995).

Most of these approaches focus on the role that domestic actors and institutions have in promoting or hindering change in core state institutions (Acemoglu et al., Citation2015; Aghion & Bircan, Citation2016; Bohle & Greskovits, Citation2012; Hall & Jones, Citation1999). If they appear in the analysis, external actors play a secondary role. There are generally only a few systematic explorations of the interplay between foreign- and state-level actors (Gereffi & Evans, Citation1981; Janos, Citation1989, Citation2000). Within the latter strand of research, considerable efforts have been devoted to the interplay between changes in core state capacities, and the various patterns of interaction between multinational companies (MNCs) and public and private actors from the (semi-)peripheries (Evans, Citation1979, Citation1995; Gereffi, Citation1995; Gereffi, Humphrey, & Sturgeon, Citation2005). Much less has been written on the question of how core countries shape the capacities of states in the (semi-)peripheries (Bruszt & Palestini, Citation2016).

In this paper, we intend to help fill this gap by exploring the developmental effects of the European Union (EU) – the most substantial transnational regime engaged in integrating countries at different levels of development. The EU is the only integration regime that has developed encompassing programs designed to comprehensively upgrade numerous core state institutions in lesser-developed countries (Bruszt & Palestini, Citation2016). State capacities have played a key role in EU policies during the integration of the Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) economies into the single European market (Bruszt & Vukov, Citation2017).

The special attention the EU devoted to state capacities is linked to two fundamental dilemmas of economic integration. The first challenge is making and implementing shared rules and policies. From the perspective of economic actors, integrated markets only work to the degree that member states harmonize a growing number of regulations, and enforce these shared rules in the same way everywhere. The second challenge is that the implementation of uniform rules might produce negative developmental externalities in lesser-developed economies. The countries participating in the process of market integration are endowed with vastly different capacities to foresee and manage the potential developmental consequences of adopting economic rules from more developed countries (Bruszt & McDermott, Citation2014).

The two dilemmas are interlinked: all parties should have both the capacity and the incentive to play by the shared rules and policies. However, all of them should be able to live by these rules in the first place. Key EU actors feared that the weak capacity of the lesser-developed member states could prevent them from fully implementing the rules and policies of the common market. It was feared that the inability of countries in the (semi-)peripheries to play by the common rules and policies of the single market would lead to a race to the bottom; in other words, that it would undermine the transnational market’s integrity. The other fear was that the weaker states might not be able to foresee and manage the potential negative developmental consequences of integrated markets. The resulting economic and political tensions could spill over to the stronger economies in the form of social and political strains, high levels of migration, and primarily, an increased need for financial transfers from the core to the periphery (Bruszt & Langbein Citation2015).

The European Commission brought the domestic institutional change under supranational control during the Eastern enlargement. EU interventions to upgrade institutions were only meant to occur in the pre-accession period. Still, their meticulousness and their encompassing nature were comparatively unprecedented (Bruszt & Campos, Citation2017).

We explore whether and how the EU induced upgrading of core state institutions (the judiciary, bureaucracy and competition authority) helped alter developmental paths in the CEE countries. In this paper, we understand development as a change in the pattern of insertion into regional and global markets. Countries might start market integration in sectors with lower technological complexity requiring unskilled or semi-skilled labor. By increasing the skill content and complexity of their exports, they alter their positions in global value chains, and they gain considerably more from integration in transnational markets. Our focus on qualitative change in developmental paths draws on the Schumpeterian approach: Long-term growth results from innovation, which yields qualitative changes in production (Aghion et al., Citation2013).

We use two unique databases to answer the above questions. First, the paper builds on new data regarding the quality of foreign trade, which we use to measure changes in developmental paths related to international trade (Bruszt & Munkacsi, Citation2016). The quality of foreign trade refers to the complexity of net export goods in terms of technology and labor skill. Since the 1990s, the CEE countries have reoriented their trade toward EU member states and have become part of European production chains. In the 1990s, most of these economies started as exporters of goods with lower technology levels or skill content. As they joined the European and global value chains, many of them began to export products with higher complexity, based mainly on assembling goods imported from more developed countries. By the early 2000s, the export structure of the more successful CEE countries began to resemble those of the most advanced Western European economies. However, the increased complexity of exports, due largely to inclusion in European production chains did not automatically result in enhanced domestic benefits. Indeed, at the start of the EU integration process in 1997, all CEE countries were in the red: they were importing more high-technology or high-skill content goods than they were exporting. The change was slow in most states, but by 2014, some CEE economies managed to improve their position in global trade. Some had even reached a positive balance in their net exports of highly complex goods.

For measuring EU-induced institutional change, we use data based on the coding of the regular standardized EU Progress Reports that monitor progress in the institutional change required for gaining membership (Bruszt & Munkacsi, Citation2016). Using these reports, we have created a database that registers institutional change on a year-by-year basis. We found that at the start of accession negotiations, the performance of the three key institutions (judiciary, bureaucracy, competition) in all the accession countries was judged to be far below the minimum level required for membership in the single European market. Even the best performing CEE states did not possess the minimum institutional capacities demanded by the EU. By the time of accession 7–9 years later, most would-be Eastern EU member states met or even surpassed the minimum expected levels of core state capacities. In contrast, none of the candidate countries on the ‘waiting list for EU membership’ were even close to the minimum levels in the second half of the 2010s when we produced our data.

Our main finding is that the EU-induced upgrading of the judiciary and the bureaucracy has significantly improved developmental outcomes, increasing both the quantity and the quality of exports. Similarly, we found that enhancing the capacities of competition authorities also had effects on the quality of exports. We also found that a predictable, reliable and calculable judiciary performs the most critical role.

The EU-induced upgrading of core state capacities had no long-term developmental goals. The goal of these interventions was to increase the ability of the new member states (NMS) to implement the rules of the EU markets. At the same time, the EU wanted to reduce the danger of excessive negative developmental consequences resulting from their implementation (Bruszt & Langbein, Citation2015) We were explicitly warned on several occasions by chief Commission administrators not to list ‘development’ as a goal of the EU accession strategy. The typical justification we heard was that ‘our mandate was solely to explore potential large-scale dangers of implementing the EU rules in these countries’ and that the ‘core idea of the integration strategy was that the extended market would take care of the rest’.

However, there was an unintended side effect or collateral benefit of externally induced state upgrading: a gradual change in the quality of international trade that also promised change for developmental pathways.

We start by presenting a political economy framework, which yields hypotheses about the expected effects of upgrading core state institutions. The second section discusses the data while the third outlines our methodology. Section four presents and discusses the findings, while the last section concludes.

The literature on institutions and development

What role can states play in furthering economic development in lesser-developed countries? There are two leading positions on this issue in the literature. According to the first, developmental constraints are primarily exogenous: the rules of transnational markets leave gradually less room for domestic actors to actively shape developmental outcomes (for discussion of this literature, see the introduction of the Special Issue). Having a specific level of state capacity might be the condition for luring foreign direct investment to the lesser-developed countries. However, the actual positioning of lesser-developed economies in transnational markets depends primarily on the strategic decisions of MNCs.

In contrast to the various versions of dependency theory, representatives of a second, much more diverse approach claim that changes in the properties of core state institutions can alter the parameters of development. Capable states can create a conducive environment for innovation. They can enable and actively promote domestic actors’ capacities to improve their positions in transnational markets, form developmental alliances, and negotiate mutually beneficial deals with MNCs (Bohle & Greskovits, Citation2012; Evans, Citation1979, Citation1995; Humphrey & Schmitz, Citation2000).

Three different economic and political economy approaches explore path-changing developments. The first is the research strand dealing with developmental states; the second is the literature dealing with the middle-income trap; and the third is the literature dealing with upgrading in global value chains (Aghion & Bircan, Citation2016; Evans, Citation1995; Gereffi et al., Citation2005). We use them to present plausible mechanisms that can link externally induced upgrading of core state institutions to improvement in the composition of exports. The vibrant and fast-growing general literature on the role of institutions, including the role of state institutions in increasing nominal growth, is outside the scope of this paper.

The literature on the developmental state explores why late developing countries exhibit dramatic variation in their capacities to embark upon export-based developmental paths and improve the position of domestic firms in regional and global markets (Evans, Citation1995; Wade, Citation1990). Researchers in this approach argue for the causal importance of capable and autonomous state bureaucracies in economic development (Evans, Citation1995, 2012; Weiss, Citation1998). Based on this literature, one can identify several mechanisms linking improvements in bureaucratic quality to the composition of exports. First, professionalization and an increase in the autonomy of the state administration helped to detach the state from the short-term interests of domestic firms (Evans, Citation1995). The reduction of rent-seeking opportunities forces firms to pursue other profit strategies, including innovation. More autonomous bureaucrats can design and implement better programs that support departure from the developmental status quo. Second, detecting and exploiting opportunities for development does not only require bureaucrats with the capacity to gather and process information from domestic firms. It also requires specific skills to analyze trends in transnational markets, design programs for adjusting local development to the challenges of volatile markets, transfer know-how to domestic producers, and improve organization and resource mobilization. Civil servants skilled in development management can take more innovative and experimental approaches by collaborating with private and public actors, providing incentives such as technical assistance, supporting local capability-building initiatives and closing off ‘low-road’ options (Evans, 2012; Locke, Citation2013).

In this special issue, several papers demonstrate how these mechanisms can work. Comparing the Polish and Hungarian dairy sectors shows how the insertion and then the qualitative repositioning of the Polish dairy sector in the European market presupposed the prior transformation of the sectoral state (Bruszt and Karas, in this issue). It required the creation of support organizations that transferred European market trends and information about the complex requirements of entry to producers, and helped farmers mobilize their resources to meet these requirements. The papers dealing with the insertion and upgrading of the Polish, Romanian and Spanish automotive sectors in global markets provide similar examples of how changes in state capacities can yield changes in export quality (cf. Markiewicz, Vukov, and Šćepanović, in this issue). According to the literature about upgrading within global value chains, foreign direct investment (FDI) on its own does not lead to a change in the quality of exports (Nölke & Vliegenthart, Citation2009). Possibilities of upgrading depend on the capabilities of local supply bases (Gereffi et al., Citation2005). Changes in the latter, on the other hand, might presuppose local industrial policies and mobilization of regional developmental alliances that require professional bureaucrats with up-to-date knowledge of industrial policy trends (Humphrey & Schmitz, Citation2000).

As for the judiciary, furthering judicial independence and capacity contributes to increases in predictability and opportunities for long-term planning and investment. If economic actors have a stable expectation that more powerful economic or political actors cannot arbitrarily take away wealth and opportunities from them, than there will be more significant incentives for them to spend on innovation (Aghion & Bircan, Citation2016). Innovation, in turn, can increase production and exports, particularly of those goods which require higher technology and labor skills. From the perspective of firms, there is a robust institutional complementarity between capable and independent bureaucracies and competent and autonomous judiciaries that can defend economic players from arbitrary state interventions. Together the upgrading of these institutions can enhance both the quantity and quality of net exports by reducing transaction costs and the chances of bribery and corruption in general. The latter can work against selection and can help firms with lower productivity, but better connections gain domestic and foreign markets. A competition authority with more resources, higher expertise, and well-trained staff can bring about development by creating a business environment that welcomes innovative firms and prevents domestic firms from focusing on rent-seeking by misusing economic power.

Based on a Schumpeterian model of development in which change in developmental paths comes primarily from innovation, the literature on middle-income traps stresses precisely these types of institutional complementarities. More specifically, this approach suggests complementary roles in encouraging research and development (R&D) investments and innovation by competent and efficient courts and an empowered and capable competition policy. Patent protection by a capable judiciary increases post-innovation rents, whereas enforcement of competition reduces pre-innovation rents for highly competitive firms (e.g. Aghion, Akcigit, & Howitt, Citation2013). At the level of core state institutions, this model predicts improvement in the quality of exports in parallel with increases in judicial efficiency to enforce the rights of innovators and in the capacity of public competition agencies to implement the rules of competition.

The political economy version of the same research strand is closer to the developmental state literature in that it stresses the need for highly trained and capable bureaucrats. The upgrading reforms required to move out of middle-income status ‘operate at multiple levels’. They are ‘difficult and complex’, requiring ‘institutions to coordinate, monitor and reconcile the interests of multiple actors, and to help provide specialized information’ (Doner & Schneider, Citation2016, p. 612). It requires highly trained civil servants with the capacity to run various specialized state agencies that promote innovation (Doner & Schneider, Citation2016). The need for bureaucrats with the ability to run specialized state agencies can also be deduced from the emerging literature on the ‘entrepreneurial state’ (Mazzucato, Citation2011).

To summarize, we should expect improved judiciaries, bureaucracies and competition authorities to result in qualitative improvements in the developmental paths of lesser-developed economies.

The EU and state institutions in Central and Eastern Europe

The problem of building and upgrading core state capacities is that in many cases, social and economic divisions created in earlier stages of development prevent the establishment of developmental alliances with sufficient power to induce institutional change (Doner & Schneider, Citation2016). Improvements in the autonomy and capacity of core state institutions might deprive strong economic or political actors of stable flows of rents. Therefore, they will resist change if they can (Hellman, Citation1998). Alternatively, the potential beneficiaries of state upgrades might have insufficient capacity, resources and organization to wield an effective voice. Even if the groups that benefit from a mediocre institutional status quo are weak, core developmental state institutions do not change (Bruszt & McDermott, Citation2014). Because of such endogenous constraints, institutional change might be slow.

In these situations, external actors can alter the incentives and capacities of domestic actors, helping to instigate a departure from an inadequate institutional status quo. Something similar happened during the Eastern enlargement of the EU (Bruszt & Vukov, Citation2017, see also Bruszt and Langbein, in this issue). Unlike during the previous waves of EU enlargement, the EU has invested considerable energy in upgrading core state institutions in the CEE countries. As discussed above, the EU feared that due to the weakness of these states, new members would not be able to implement the continental market’s rules, nor would they be able to foresee and manage the potential negative developmental consequences of applying those rules. The governance of economic integration in the Eastern periphery reflected these fears. Instead of using an arm’s-length checklist for compliance-based solely on the incentives linked to membership, the Commission included the accession countries’ governments in a nearly decade-long joint problem-solving process for institution building. The EU took what Wade Jacoby (Citation2006) calls a coalition approach to guide institutional change in the would-be member countries. Usually, the process started with the EU monitoring report that provided the Commission’s opinion on the distance between EU requirements and the situation on the ground. In their mandatory reply, applicant states had to include a plan, which consisted of how these problems would be remedied and with what resources. While these steps were repeated yearly until the Commission closed the specific chapter, the Commission embedded Eastern state restructuring in twinning programs: a transnational network of technical assistance that mobilized thousands of public and private actors in the old EU member states. The latter not only helped the Commission to gather intimate knowledge on institutional change during the monitoring process, but also to participate in joint problem-solving with domestic actors (Bruszt & McDermott, Citation2014).

The EU involvement in institutional upgrading in the CEE countries had no developmental goals; it did not aim to change developmental paths in these countries (Bruszt & Langbein, Citation2015). Any developmental outcomes can be considered unintended side effects or collateral benefits (or damage).

In 1997, the Council gave the Commission the task of monitoring the CEE countries’ progress toward accession on a year-by-year basis. The Commission summarized the outcome of this exercise in the annual Progress Reports, which intended to work as a mechanism to help accession countries align their legislation with the acquis (European Council, 1997). The Commission used these reports to assist the countries engaged in domestic institution building, a process that generally lasted for 7–9 years.

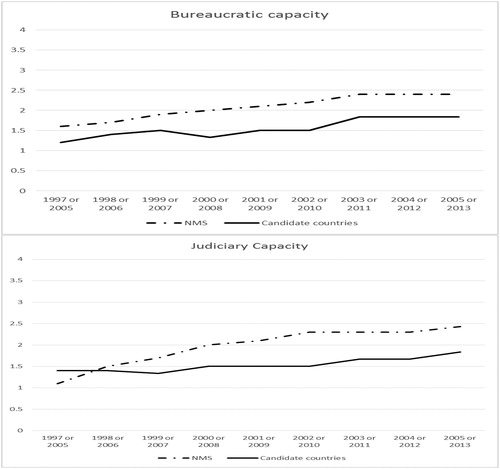

The Commission’s first monitoring reports, published in 1997, painted a rather bleak picture of the applicant countries’ institutional capacities. The reports demonstrated the need for significant changes to the judiciary, public administration and competition authorities in all applicant countries. In a previous analysis, we found little difference at the start of EU monitoring and assistance (Bruszt & Campos, Citation2017). Indeed, there is one realm – judicial capacity – in which the average score of the Western Balkan countries at the time of gaining candidate status was higher than the score of NMS at the beginning of the EU monitoring period (). The beginning of the monitoring period was 1997 for NMS and 2005 for candidates, allowing the latter group to catch up in various dimensions. A few years before accession, several of the would-be member states met the essential institutional requirements and were only requested to introduce minor changes. Other states were still required to make considerable changes in the final year before accession1 (for discussion about the diverging paths in civil service reform in the CEE countries, see Meyer-Sahling, Citation2004).

Figure 1. Building state capacity: yearly averages of bureaucratic and judicial capacity for new member states (1997–2005) and Candidate countries (2005–2013).

By the end of the accession period, the NMS had converged to EU norms, whereas there was no significant change in the other candidate countries. EU conditionality and assistance were the same in all cases; the differences in outcomes are mainly due to political elites’ lack of commitment to EU integration (Bieber, Citation2011).

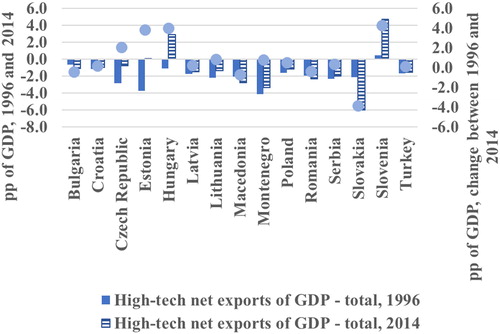

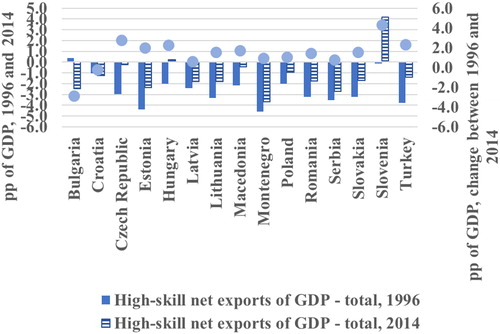

Measuring the quality of foreign trade

The quantity of foreign trade is measured, as usual, by net exports of goods. We measured international trade quality using two different variables: high-tech net exports of goods and high-skill net exports of goods (as a percentage of GDP). Before the advent of global value chains, the share of high-tech (net) exports of goods was by itself useful for measuring the quality of insertion in transnational markets. In a world dominated by GVCs, a large share of high-tech goods in exports might be caused, in some countries, by a considerable upgrading of domestic production. But the same measure might also hide the fact that local producers are at the low end of value chains; they use unskilled labor to assemble technologically sophisticated goods that are produced outside of the country. This means that ultimately, little value is added to the country. Therefore, we also use the high-skill share of net exports of goods to measure changes in the quality of trade. In both cases, we consider the quality of imports and use high-tech and high-skill net exports of goods as our measures for change in the quality of trade. Data on high-tech and high-skill net exports of goods come from Bruszt and Munkacsi (Citation2016). They based their calculation of technology and skill intensity on input data from the United Nations Commodity Trade Statistics Database,2 a dataset of annual product-level international trade flows reported by about 200 countries since 1962. Data from 15 Eastern and Central European countries between 1996 and 2014 were considered. These include 8 out of the 10 states that joined the EU in 2004; Bulgaria and Romania, which joined the EU in 2007; Croatia, which became a member in 2013; and four candidate countries (Montenegro, Macedonia, Serbia and Turkey). The original product-level data were transformed over several steps into Lall’s (Citation2000) technology taxonomy and Peneder’s (Citation2001) skill breakdown.

Lall (Citation2000) makes a distinction between five technology levels: primary, resource-based, low-technology, medium-technology and high-technology. For the sake of simplicity, we merged the first three categories. Both primary and resource-based products include mainly food and natural resources, while the latter group consists of more processed goods. Low-technology goods include textiles, footwear and metal products. Medium-technology goods are more sophisticated, the main examples being automotive and engineering products. High-technology manufacturing includes electronic and electrical equipment, and pharmaceuticals. Compared to other technology classifications, Lall’s (Citation2000) approach avoids overlaps between categories, provides a significant number of categories, and is based on more detailed product-level data.3

Peneder (Citation2001) distinguishes between low, medium and high levels of skills. The classification depends on the share of blue-collar low-skill, blue-collar high-skill and white-collar low-skill (together medium-skill), and white-collar high-skill employees. Low-skill sectors mainly employ workers who operate factory machines. The blue-collar industry mainly employs skilled agricultural workers and artisans; the white-collar category includes clerks, salespeople and service workers; and the high-skill industries employ legislators, managers and professionals. Thus, most of the food and textile industries are low-skill, medium-skill sectors include transport and electrical equipment, and the production of computers and pharmaceuticals usually require high-skill workers.4

illustrates changes in the developmental paths as measured by the high-skill content of net exports of goods. In 1996, most of the countries – except for Bulgaria – imported more high-skill goods than they exported. This slowly changed over time with only a few exceptions: high-skill goods still contribute negatively to net exports of goods. In 2014, the only country that exported more high-skill goods than it imported was Slovenia. At the same time, in other CEE countries, high-skill net exports of goods slowly increased. Except for Bulgaria, which experienced a deterioration in the skill content of net exports of goods between 1996 and 2014, the net change reached or surpassed 2% in most of these countries.

Figure 2. Net exports of high-skill goods in 1996 and 2014 (percentage and percentage points of GDP).

Note: The chart shows data from 1996 to 2014 (if available). The blue points show the difference between high-skill net exports of GDP in 1996 and 2014.

presents a similar pattern for the technology intensity of net exports of goods. Eastern and Central European countries usually import more high-tech products than they export. This has not significantly changed over time. The only exceptions are Hungary and Slovenia, although in both countries the contribution of high-tech goods to net exports has decreased since 1996.

Measuring institutions

We look at six institutional dimensions that deal with a critical aspect of enforcing the EU’s rules regarding the judiciary, public administration and competition (including state aid). These are the following: judicial capacity and independence, bureaucratic independence, bureaucratic capacity and civil servants’ training, and the capacity of the competition authority. We collected data for the six institutional dimensions by coding the European Commission’s annual Progress Reports. One of the key advantages of this source is the Progress Reports’ detail, which makes it possible to look at different dimensions of the reform process. Also, it is reliable and independent of political considerations. The desk officers freely gave highly negative opinions about institutional conditions in the accession countries, including in the final year before accession. We found that according to the monitoring reports, institutional change in some of the core state institutions fell short of the minimum requirements in several of the countries accepted for membership in 2004 and 2007.

A possible drawback of the Progress Reports is how they were constructed. In evaluating the progress made in the different countries, the European Commission was in constant negotiations with the relevant national ministries. There was ‘give and take’ during the drafting of the reports: the report softened some criticism in exchange for more significant reform initiatives. For example, instead of stating bluntly that the country under review had not made any progress in implementing judicial reform, we sometimes found in its place an expression such as ‘one can expect progress in implementing judicial reform in the medium term’. Since this is a potential drawback, we tried to code such elements of ‘diplomacy’ in monitoring reports.

The area of competition policy provides an illustrative example of the coding. In addition to the transposition of the relevant parts of the acquis, the EU required the accession countries to set up a national competition authority. Would-be member states had to give to the competition authority the ‘necessary powers enabling it to investigate anti-competitive practices, and the powers to order the termination of such practices, including the rights to impose sufficient deterrent sanctions’ (European Commission, Citation2005). In its evaluation of the Czech Republic, the Commission found that the country’s competition authority generally had a well-qualified staff to perform its duties (European Commission, Citation1999, p. 66). In evaluating progress in Romania in 2002 for the same policy, the Commission still found problems with all the dimensions mentioned above. The competition authorities were still not empowered ‘to oppose legislation restricting competition’, and the existing regulations had not yet established rules such that ‘legislation on competition takes precedence over legislation on businesses and legislation under which state aid is provided’. While the Competition Office and the Competition Council are necessary organizations for enforcing EU competition rules, they still ‘require further strengthening in terms of human resources and training’. Finally, the Commission found significant problems in the behavior of the enforcer: ‘Application of the state aid rules is not comprehensive, and numerous state aid measures are not notified to the competition authorities. The Competition Council should take a firmer and more pro-active approach to ensure the effective application and enforcement of the state aid rules, including non-notified aid, and the alignment of existing aid schemes and legislation under which authorities at various levels grant aid’.

Although it is a possibility, it is difficult to find anything in the data that points to a systematic under- or overvaluation of one or more of the candidate countries. Furthermore, the Progress Reports are vulnerable to many of the same criticisms that have been directed at other operationalizations of institutional capacity, namely that the measure is based on subjective assessments rather than objective criteria. However, this is only partly true as the country experts had to evaluate institutional conditions in each sector according to the standards set by the Commission’s experts (e.g. European Commission, 2005).5

To extract the data from the Progress Reports, we build on the approach used by Hille and Knill (Citation2006), who collected data from the Progress Reports on institutional quality in 13 transition countries between 1999 and 2003. Instead of using a computer algorithm in the coding process, we opted for manual coding. There are two rationales in favor of a manual process. The first is that the Progress Reports contain multiple dimensions that would be difficult to separate based on an algorithm. Manual coding simplified the collection of data on several aspects of institutional reform. Second, to comprehend the Progress Reports for any given year, knowledge about previous years is often required due to frequent references to earlier reports.6

We coded all the relevant dimensions for this paper as binary outcomes. A 1 indicates that the country is not living up to the EU minimum requirements, whereas a 2 suggests that a satisfactory level has been reached in that particular area.

Judiciary

We measure two aspects of the judiciary in the paper. The first – what we call the judiciary capacity dimension refers to the unbiased and efficient application of the law and it includes three interlinked concepts: (1) access to courts; (2) the court procedure (i.e. legal certainty, which refers to a unified interpretation of the law by courts, the requirement of justification for judicial decisions, and an even-handed procedure); and (3) the enforcement of legal judgements.

The second dimension of the judiciary refers to judicial independence in terms of appointment, promotion and remuneration. This aspect of the courts is something that the European Commission emphasizes in the Progress Reports. Many of the countries that were or are taking part in the accession process suffer severe problems with politicians using their political power to appoint, promote and or remunerate judges and other ‘non’-political professionals in the court system. These issues jeopardize the independence of the judicial system, undermining its capacity and, by extension, the rule of law in the country. Evaluations of this institutional arena are quite detailed and precise, like the one from the monitoring report for Albania in 2006. The report stated that

…judicial proceedings remain lengthy, poorly organized and lack transparency. The proposed new Law on the Judiciary does not address three long-standing shortfalls: improving the independence and constitutional protection of judges, improving the pay and status of the administrative staff of the judicial system and the appropriate division of competences between the judicial inspectorates of the High Council of Justice and the Ministry of Justice. A system for the evaluation of prosecutors is not yet in place. Implementation of a planned reorganization of district courts is needed to improve efficiency, but has not yet begun. Many courts still lack adequate space for courtrooms, judges’ offices, archives and equipment. The draft Law on the Judiciary provides that all new judges must be graduates of the Magistrates’ School, but no other steps have been taken towards appointing judges and prosecutors through competitive examinations. Expansion of the academic possibilities for studying law will require an appropriate system of quality control. The profession of notary and advocate continue to be weak points in the judicial system, with little legal or practical development.

Bureaucracy

The evaluation of public administration is based on the European Principles of Administration, developed by SIGMA in cooperation with the European Commission. To measure its quality, we focus on three dimensions of public administration: its independence, capacity, and civil servants’ training.

Independence refers to the public administration’s de jure and de facto independence from political pressure. Just as with the judiciary, the Progress Reports place a strong emphasis on the bureaucracy’s autonomy from political influence. The civil service must follow the law and treat all citizens as equal in order for it to serve the public interest. Based on the EU monitoring reports, we measure bureaucratic independence by the degree to which professional and non-political criteria dominate the civil service career structure (i.e. whether professional standards apply to performance evaluation, recruitment, promotion and employment protection).

Bureaucratic capacity in the Progress Reports refers to the existence of a set of coherent institutional and organizational administrative structures that ensure that the bureaucracy can deliver. The Progress Reports specifically emphasize the importance of civil servants’ training, as many civil servants in former communist countries were not trained to deal with the challenges of administering a market economy.

Competition and state aid

The national state aid authority is often referred to as the Competition Office, Competition Council, or the Division of Competition and State Aid. Some countries divide responsibilities across several bodies, while others have only one responsible authority. Sometimes, these authorities are responsible for anti-trust policy, mergers, and state aid. They also guarantee that the entry of economic players into the domestic market is free of discrimination and independent of their country of origin within the EU. Their other main task is keeping state aid confined within the narrow boundaries of EU regulations.

Competition policy capacity is the quality of the enforcement of EU state aid rules. It refers to the resources, expertise and training that the agency is equipped with to fulfill its duties satisfactorily.

Empirical analysis

Based on the two-panel datasets (described in the previous sections) and a set of control variables defined below, we employed a fixed-effect model. This has the advantage of utilizing the panel structure of the data. Fixed-effect models explore the relationship between the dependent and independent variables within each country over time. This method accounts for several factors. Some do not change over time but differ across countries, while others vary over time but are constant across the different countries. In other words, it accounts for individual and time heterogeneity.

Regression methodology

Formally, the fixed-effect model can be expressed as:

(1)

(1)

where

is the set of dependent variables (quantity and quality of foreign trade) and

is the set of independent variables (institutional measures and control variables) for country i at time t;

is the coefficient vector for those independent variables;

and

are country and time-specific dummy variables, and

is the error term for each country at time t.

We calculated the different variables of net exports of goods () as a percentage of GDP. To this end, we use purchase price-adjusted GDP figures from the World Bank, which are defined as the sum of gross value added by all resident producers in the economy, plus any product taxes and minus subsidies not included in the value of the products. We converted national currencies to U.S. dollars.7 Institutional measures (part of

) are dummy variables coded as 1 and 2, with 2 standing for having met the institutional requirements of the EU. Provided that reform implementation and the materialization of gains in the quality of foreign trade takes time, we consider 2- and 3-year lags in this exercise. We describe the control variables (also belonging to

) in the next section.

Control variables

It is commonly argued in the literature that the number of veto players present in the political system affects a country’s reform capacity. Tsebelis (Citation2002) claims that everything else being equal, countries with numerous veto players will be less likely to adapt to new circumstances. To control the number of veto players, we use the Polcon variable developed by Henisz (Citation2000), which takes the number of independent branches of government with veto power over the policy change as a point of departure. We then build a simple spatial model of political constraints in a country by assuming that the preferences for the status quo in each of these branches are independently and identically drawn from a uniform and unidimensional policy space. The advantage of this variable, compared to many other variables used in the literature, is objectivity (compared, for example, to International Country Risk Guide (ICRG) and the Polity index). It can be seen as a proxy for the number of independent veto points over policy outcomes and the distribution of those actors’ preferences.8

Researchers often use the share of government consumption in GDP as a proxy for the degree of state inefficiency. For instance, an early example by Barro (Citation1991) demonstrates that higher government consumption is negatively associated with growth because of the distortive effects of taxation and government expenditure programs. Other examples include Barro and Sala-i-Martin (Citation1992), Henrekson, Torstensson, and Torstensson (Citation1997) and Canova (Citation2004). To control for this, we include the government consumption variable released by the World Bank, which covers all current government expenditures for purchases of goods and services (including compensation of employees).9

R&D should naturally affect the quality of foreign trade via enhancing innovation and productivity, which is why it is necessary to control for it in our statistical analysis. The World Bank’s R&D indicator measures a country’s expenditure (both private and public) on creative work that has been systematically undertaken to increase society’s knowledge. It covers basic research and applied research, and experimental development.10

We have included three additional variables as controls: urbanization, corruption and economic growth. Urbanization refers to the proportion of the population that lives in urban areas; the measure is commonly used in studies of transition economies as a proxy for societal development. Corruption is another commonly used variable in the literature. In short, more corrupt countries tend to be less efficient than their less corrupt counterparts, which affects production and competitiveness. We use the Worldwide Governance Indicators’ control of corruption index released by the World Bank to measure the degree of corruption in each country.11 To control for economic growth, we use the World Bank’s national account data of GDP in current USD, from which the growth level is calculated.

Empirical findings

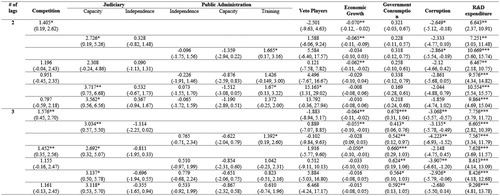

Based on our panel regression analysis, several dimensions of the judiciary, bureaucracy and competition authority seem to positively influence the quantity and quality of international trade. While significance varies, we find evidence that suggests EU-mandated core state institutions have a positive impact on countries’ developmental paths.

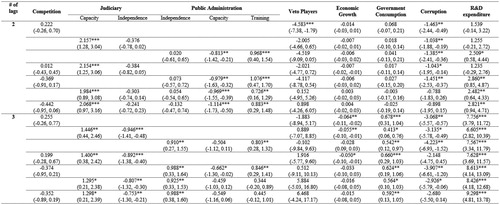

First, there is strong evidence that an ‘EU conforming’ judicial capacity improves net exports of goods (). Once countries meet the minimum EU requirements, there is a 2.7 to 3.7 percentage point increase in net exports of goods in their GDP. To put this in perspective, countries increased their net exports of goods as a share of GDP by an average of about 2–3 percentage points over a decade. Furthermore, given that net exports of goods usually vary between 5 and 15% of GDP in our sample, this impact can be considered quite large (although the improvement required in judicial capacity is also sizable).

Figure 4. Regressions – total net exports of goods (as a share of GDP).

Note: All regressions contain country and time fixed effects. Significant codes: ***0.001, **0.01 and *0.05.

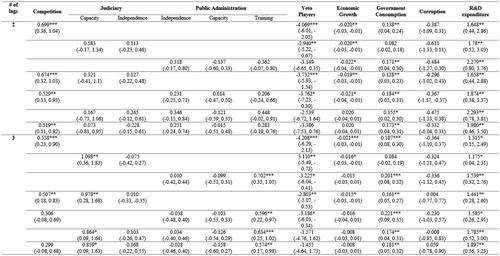

Second, the quality of foreign trade, as measured by high-tech net exports of goods, is similarly affected by judicial capacity (). Notably, meeting minimum EU requirements for judicial capacity implies a 1.3–2.2 percentage point increase in high-tech net exports of goods. This effect seems to be smaller unless we consider that high-tech net exports of goods vary between −4 and 4% of GDP. Hence, this impact is even more profound than the effect of judicial capacity on the quantity of foreign trade. We also find evidence for the importance of bureaucratic independence, which is measured by the dominance of professional, non-political criteria in the career structure of the civil service, and civil servants’ access to training. These aspects respectively promote high-tech net exports of goods by 0.9–1 and 0.7–1.1 percentage points.

Figure 5. Regressions – high-tech net exports of goods (as a share of GDP).

Note: All regressions contain country and time fixed effects. Significant codes: ***0.001, **0.01 and *0.05.

Third, countries that meet EU requirements in terms of judicial capacity, civil servants’ access to training, and the availability of resources for the competition authority see significant effects on their high-skill net export of goods (). The impacts of these three variables amount to 0.9–1.1, 0.6–0.7 and 0.5–0.7 percentage points, respectively.

Figure 6. Regressions – high-skill net exports of goods (as a share of GDP).

Note: All regressions contain country and time fixed effects. Significant codes: ***0.001, **0.01 and *0.05.

Among our critical institutional variables, judicial capacity plays the most salient role: meeting the level required by the EU has significant effects (with a 2- or 3-year lag) on net exports of goods and the quality of foreign trade, whether from the perspective of high-tech or high-skill content. Only EU-mandated training of bureaucrats – which empowers them with specialized knowledge – has similar effects on the quality of net exports. Improvement in bureaucratic independence has a significant impact on high-tech net exports of goods. Additionally, competition authorities with a sufficient resource endowment yield a sizable increase in high-skill net exports. In comparing the complexity of exports and changing skill content, we find that in both cases, judicial capacity is the most critical variable. Public servant training explains changes in export complexity better than the independence of the civil service. In general, the findings show that the emergence of a capable judiciary is crucial in changing developmental paths. Our finding lends support to the middle-income trap argument, which states that a competent judiciary contributes to development by helping to build stable expectations among economic actors so that they can safely profit from innovation. But they also support the neo-Weberian claim that the judiciary is key to the emergence of a predictable bureaucracy – one that keeps its actions within the boundaries of the law, defends the rights of private actors from erratic state interventions and shields the bureaucracy from arbitrary interference by incumbents (Bruszt & Campos, Citation2017). A professional and depoliticized bureaucracy can make policies that directly support innovation. In this way, professionalization contributes directly to changes in the quality of the export.

Conclusions

In this paper, we explored the developmental effects of EU-mandated institutional changes to core state institutions: the judiciary, bureaucracy and the competition authorities in Central and Eastern Europe. According to the annual Progress Reports, none of these countries met the minimum level of EU institutional requirements at the start of the accession process. However, all of them made significant progress by the time they received EU membership. Our key finding is that EU-mandated institutional changes have had significant effects on the quantity and the quality of net exports in these countries. Since regional integration of countries at different levels of development is deepest in the EU, the results of our research may pertain to integration regimes in other parts of the world.

We found that of our three institutional variables, judicial capacity is most important for inducing developmental change related to international trade. Meeting EU requirements for judicial capacity has significant effects on both net exports of goods and their complexity, contributing to improvements in their high-tech and high-skill content. Our finding supports the claims of economists, introduced in the theoretical section of this paper, who stress that a predictable, reliable and calculable judiciary is a necessary precondition for development. It also provides direct support to students of the middle-income trap, who argue that a strong defense of intellectual property rights is the fundamental precondition for innovation. A capable judiciary is also key to bureaucratic autonomy. It reduces the dangers associated with arbitrary interventions in the civil service by politicians or powerful economic actors, and increases the capacity of competition authorities (Bruszt & Campos, Citation2017).

Furthermore, we found strong support for the neo-Weberian idea that an increase in bureaucratic professionalization is the precondition for the emergence of state capacity that is sufficiently able to support development. EU-mandated training empowers bureaucrats with specialized knowledge, which has significant effects on the quality of foreign trade. Finally, we found that enhanced bureaucratic independence has a considerable impact on high-tech net exports of goods and competition authorities endowed with sufficient resources yield an increase in high-skill net exports of goods.

These EU-mandated, externally induced institutional changes were not intended to have developmental effects. Instead, they were designed to help manage the increased interdependence resulting from the deeper economic integration of economies at dramatically different levels of development upon joining the single market. More specifically, their goal was twofold: to defend the interests of the stronger and more developed economies in the integration regime, and to increase the probability that the lesser-developed new members would be able to play by the common rules without extra transfers after full membership. The good news is that externally induced institutional changes yielded an unintended collateral benefit of improving the quantity and quality of net exports in these countries. The discouraging news is that in the post-accession period, the European Commission has only weak willingness and capacity to enforce EU-wide norms for core state institutions (Kochenov & Bárd, Citation2018; Kovács & Scheppele, Citation2018). Recent attacks against the independence of the judiciary and civil service in Hungary and Poland endanger the political and economic benefits of the institutional upgrading undertaken during the enlargement process, and undermine the effectiveness of EU policies aimed at achieving economic convergence. The subversion of the autonomy and professionalism of these core state institutions sends these countries on a developmental path where loyalty to state incumbents, rather than innovation, is the criterion for economic success. Brussels’ weak reaction to attacks against core state institutions places the EU in an ambiguous position. By its own rules, the EU is obliged to transfer significant resources to the lesser-developed member states to support economic convergence between them and the more developed states. Until the Commission introduces effective measures to control the quality of state institutions in the member countries, it will have to transfer EU monies to member states that undermine the very state institutions that could support convergence.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Philipp Chapkovski, Gabor Oblath, Istvan Schindler and Peter Vakhal for their valuable comments. In addition, we have received valuable feedback from participants of seminars at the Bank of Lithuania, at the European Commission and at the International Monetary Fund. Finally, we would like to thank for great comments to the anonym referees.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

László Bruszt

László Bruszt is a professor of Sociology at the Central European University (Budapest). His more recent studies deal with the politics of market integration. His latest publications include Leveling the Playing Field – Transnational Regulatory Integration and Development, Oxford University Press (co-edited with Gerald McDermott); ‘Varieties of Dis-embedded Liberalism EU Integration Strategies in the Eastern Peripheries of Europe’, Journal of European Public Policy (with Julia Langbein); and ‘Making states for the single market: European integration and the reshaping of economic states in the Southern and Eastern peripheries of Europe’ West European Politics (with Visnja Vukov).

Ludvig Lundstedt

Ludvig Lundstedt is a political scientist and currently works for the Swedish Municipal Workers’ Union. He obtained his MSc at the London School of Economics in 2012 and his PhD in Social and Political Science from the EUI in 2017. Among his research interest is the political economy of reform. Ludvig is currently working on wage formation and labor market policy in the Swedish public sector.

Zsuzsa Munkacsi

Zsuzsa Munkacsi is an applied macroeconomist who works for the International Monetary Fund. She obtained a PhD in Economics from the European University Institute in 2016. Prior to joining the Fund, she has worked for several policy institutions, including the former Office of the Fiscal Council of Hungary, the Bank of Lithuania and the European Central Bank (external advisor). Her research deals with macro-structural issues, such as labor market reforms, demographics, retirement and diversification – with a focus on their macroeconomic relevance.

Notes

1 The final decision regarding membership was a political one; it did not solely depend on the Commission’s evaluations of institutional change.

2 The UN dataset is available at http://comtrade.un.org/data/

3 Other classifications include Eurostat (Citation2005), and OECD Science, Technology and Industry Scoreboard (Citation2007).

4 As a first step, we downloaded the product-level data: a 3-digit level breakdown of exports of goods imports of goods by the 4th revision of the Standard International Trade Classification (SITCr4) from the beforementioned UN database. This could be directly transformed into Lall’s (Citation2000) technology breakdown. Nevertheless, Peneder’s (Citation2001) skill structure is based on the Statistical Classification of Economic Activities in the European Community (NACEr1.1). Hence, several transformation steps were needed; notably, the SITCr4 breakdown we converted into Central Product Classification version No. 2 (CPCv2), which we retransformed into Central Product Classification version No. 1.1 (CPCv1.1). The next step was a retransformation into Rev 3.1 of the International Standard Industrial Classification of All Economic Activities (ISICr3.1), which we finally converted into NACEr1.1.

5 Wherever possible, we controlled our variables with others that were similar. The institutional variables linked to democracy and bureaucracy used in this paper show a robust correlation with those used in the Varieties of Democracy project (Staffan et al., 2018).

6 Coders – all of them doctoral students with European integration training – used Atlas.ti dedicated software to create a high degree of inter-coder reliability. Two coders simultaneously and independently coded each chapter. In cases of disagreement between coders, a third coder was brought in to make the final judgment. The use of the Atlas.ti software has the advantage of increasing the transparency of the coding process because it allows the researcher to review the coding and discern why a country received a specific score. This increased the inter-subjectivity of the data. Data codebook is available online (Bruszt & Munkacsi, Citation2016).

7 More information is available on the following website: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD

8 More information is available on the following website: https://mgmt.wharton.upenn.edu/profile/henisz/.

9 More information is available on the following website: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NE.CON.GOVT.ZS.

10 More information is available on the following website: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/GB.XPD.RSDV.GD.ZS.

11 More information is available on the following websites: http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/#home, http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.URB.TOTL.IN.ZS, and http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/#home

References

- Acemoglu, D., Aghion, P., & Zilibotti, F. (2006). Distance to frontier, selection, and economic growth. Journal of the European Economic Association, 4(1), 37–74.

- Acemoglu, D., García-Jimeno, C., & Robinson, J. (2015). State capacity and economic development: A network approach. American Economic Review, 105(8), 2364–2409. doi:10.1257/aer.20140044

- Aghion, P., Akcigit, U., & Howitt, P. (2013). What do we learn from the Schumpeterian growth theory? (NBER Working Paper No. W18824). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Aghion, P., & Bircan, C. (2016). The middle-income trap from a Schumpeterian perspective (ADB Economics Working Paper Series No. 521). Mandaluyong: Asian Development Bank.

- Barro, R. J.. (1991). Economic Growth in a Cross Section of Countries. Quarterly Journal of Economics, CVI, 407–443.

- Barro, R. J., & Sala-i-Martin, X. (1992). Convergence. Journal of Political Economy, 100(2), 223–251. doi:10.1086/261816

- Besley, T., & Persson, T. (2009). The origins of state capacity: Property rights, taxation, and politics. American Economic Review, 99(4), 1218–1244. doi:10.1257/aer.99.4.1218

- Besley, T., & Persson, T. (2011). Pillars of prosperity: The political economics of development clusters. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Bieber, F. (2011). Building impossible states? State-building strategies and EU membership in the Western Balkans. Europe-Asia Studies, 63(10), 1783–1802. doi:10.1080/09668136.2011.618679

- Bohle, D., & Greskovits, B. (2012). Capitalist diversity on Europe’s periphery. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Bruszt, L., & Campos, N. (2017). Deep economic integration and state capacity: A mechanism for avoiding the middle-income trap? (ADB Economics Working Paper Series No. 547). Mandaluyong: Asian Development Bank.

- Bruszt, L., & Langbein, J. (2015). Development by stealth: Governing market integration in the eastern peripheries of the European Union (Working Paper No. 17, MAXCAP Working Paper Series). Berlin: Freie Universität Berlin.

- Bruszt, L., & McDermott, G. (Eds.). (2014). Leveling the playing field: Transnational regulatory integration and development. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bruszt, L., & Munkacsi, Z. (2016). Foreign trade sophistication in Eastern and Central Europe. Central European University, Department of Political Sciences (Manuscript-available at request).

- Bruszt, L., & Palestini, S. (2016). Regional development governance. In T. Börzel & T. Risse (Eds.), Oxford handbook of comparative regionalism (pp. 374–405). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bruszt, L., & Vukov, V. (2017). Making states for the single market: European integration and the reshaping of economic states in the Southern and Eastern peripheries of Europe. West European Politics, 40(4), 663–687. doi:10.1080/01402382.2017.1281624

- Canova, F. (2004). Testing for convergence clubs in income per capita: A predictive density approach. International Economic Review, 45(1), 49–77. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2354.2004.00117.x

- Doner, R., & Schneider, B. R. (2016). The middle-income trap: More politics than. World Politics, 68(4), 608–644. doi:10.1017/S0043887116000095

- European Commission. (2005). Guide to the main administrative structures required for implementing the acquis. Working Document. Brussels.

- European Commission. (1999). Regular Report – 13/10/99 on Czech Republic.

- Eurostat. (2005). What is high tech trade? Definition based on the SITC nomenclature. Brussels: European Commission, Eurostat.

- Evans, P. (1979). Dependent development: The alliance of multinational, state, and local capital in Brazil. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Evans, P. (1995). Embedded autonomy: States and industrial transformation. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Evans, P., Rueschemeyer, D., & Skocpol, T. (1985). Bringing the state back in new perspectives on the state as institution and social actor. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gereffi, G. (1995). Global production systems and third world development. In B. Stallings (Ed.), Global change, regional response: The new international context of development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gereffi, G., & Evans, P. (1981). Transnational corporations, dependent development, and state policy in the semi-periphery: A comparison of Brazil and Mexico. Latin American Research Review, 16(3), 31–64.

- Gereffi, G., Humphrey, J., & Sturgeon, T. (2005). The governance of global value chains. Review of International Political Economy, 12(1), 78–104. doi:10.1080/09692290500049805

- Gereffi, G., & Wyman, D. (1990). Manufacturing miracle. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Hall, R. E., & Jones, C. I. (1999). Why do some countries produce so much more output per worker than others? The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(1), 83–116.

- Hellman, J. S. (1998). Winners take all: The politics of partial reform in postcommunist transitions. World Politics, 50(2), 203–234. doi:10.1017/S0043887100008091

- Henisz, W. (2000). The institutional environment of economic growth. Economics and Politics, 12(1), 1–31. doi:10.1111/1468-0343.00066

- Henrekson, M., Torstensson, J., & Torstensson, R. (1997). Growth effects of European integration. European Economic Review, 41(8), 1537–1557. doi:10.1016/S0014-2921(97)00063-9

- Hille, P., ' Knill, C. (2006). It's the Bureaucracy ‘Stupid’: the implementation of the acquis communautaire in EU candidate countries, 1999–2003 (Vol. 7, pp. 531–552). European Union Politics.

- Humphrey, J., & Schmitz, H. (2000). Governance and upgrading: Linking industrial cluster and global value chain research (Working Paper No. 120). Brighton: Institute of Development Studies, The University of Sussex.

- Jacoby, W. (2006). Inspiration, coalition, and substitution: External influences on postcommunist transformations. World Politics, 58(4), 623–651. doi:10.1353/wp.2007.0010

- Janos, A. (1989). The politics of backwardness in continental Europe, 1780–1945. World Politics, 41(3), 325–358. doi:10.2307/2010503

- Janos, A. (2000). East Central Europe in the modern world: The politics of the borderlands from pre- to postcommunism. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. doi:10.1086/ahr/108.4.1243-a

- Kochenov, D., & Bárd, P. (2018). Rule of law crisis in the new member states of the EU: The pitfalls of overemphasising enforcement (July 27, 2018). Reconnect Working Papers (Leuven) No. 1. Retrieved from SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3221240

- Kovács, K., & Scheppele, K. L. (2018). The fragility of an independent judiciary: Lessons from Hungary and Poland – and the European Union. Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 51(3), 189–200. doi:10.1016/j.postcomstud.2018.07.005

- Koyama, M., & Johnson, N. (2017). States and economic growth: Capacity and constraints. Explorations in Economic History, 64(2), 1–20. doi:10.1016/j.eeh.2016.11.002

- Lall, S. (2000). The technological structure and performance of developing country manufactured exports, 1985–1998 (Working Paper No. 44, QEH Working Paper Series). Oxford: Queen Elizabeth House, University of Oxford.

- Locke, R. M. (2013). The promise and limits of private power: Promoting labor standards in a global economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mazzucato, M. (2011). The entrepreneurial state. London: Demos.

- Meyer-Sahling, J. (2004). Civil service reform in post-communist Europe: The bumpy road to depoliticization. West European Politics, 27(1), 71–103. doi:10.1080/01402380412331280813

- Nölke, A., & Vliegenthart, A. (2009). Enlarging the varieties of capitalism: The emergence of dependent market economies in East Central Europe. World Politics, 61(4), 670–702. doi:10.1017/S0043887109990098

- OECD. (2007). OECD Science, Technology and Industry Scoreboard 2007. Paris: OECD.

- Peneder, M. (2001). Entrepreneurial competition and industrial location. Chapter 3: Intangible investment and human resources. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Tilly, C. (Ed.). (1975). The formation of national states in Western Europe. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Tsebelis, G. (2002). Veto players: How political institutions work. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Wade, R. (1990). Governing the market: Economic theory and the role of government in East Asian Industrialization. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Weiss, L. (1998). The myth of the powerless state. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.