Abstract

Despite the important International Political Economy (IPE) scholarship on the impact of neoliberal marketisation on women in the Global South, the linkages with reproductive and informal work are often neglected, as is its interaction with multi-level varieties of patriarchy. Developing a theoretical framework merging social reproduction theory and varieties of gender regimes, this article examines how women navigate market and non-market pressures during the ongoing processes of Uzbek agrarian marketisation. By applying the concept of domestic and public patriarchy to analyse the gendered practices of food production and reproduction in Uzbekistan, the article unpacks the household-led and state-led forms of dispossession and exploitation of women's work in everyday life and investigates why women's position has not improved as a result of marketisation. The paper contributes to feminist IPE in two ways. By bringing together two strands of gender theories, it explores the link between the institutional and cultural connotation and the economic ‘valuation’ of women's work. Along these lines, it examines the weaknesses of the policy solutions proposed by the neoliberal development governance in the Global South.

Introduction

The feminist International Political Economy (IPE) literature extensively problematised the contested impact that neoliberal (capitalist) development had on women in paid work (Elson, Citation2002; Elson & Pearson, Citation1981; Kabeer, Citation2003; Razavi, Citation2009). By unpacking the weak premises on which the idea of female empowerment was built, and the correlated limitations of so-called gender mainstreaming policies, they unveiled the exploitative patterns resulting from the increased participation of women in the international division of labour—i.e. the feminisation of labour—during processes of marketisation (Barrientos, Citation2019; Seguino, Citation2010; Standing, Citation1999). The marketisation of life made employment for wages increasingly necessary; however, the types of work and wages created were highly gendered and unequal (Cousins et al., Citation2018:1064). Empirical studies on India (Agarwal, Citation2016; Mezzadri, Citation2016, Citation2019), South Africa (Barrientos et al., Citation2016) and other regions of the Global South (Arslan, Citation2020; Kabeer, Citation2012; O’Laughlin, Citation2013; Seguino, Citation1997) noted that although paid employment has often provided women with stable income and improved social status through pensions and other mechanisms of public support (Kabeer, Citation2012; Karshenas et al., Citation2014), the integration of women in the labour force as a result of new labour demand did not automatically correspond to their emancipation (Barrientos et al., Citation2016). These studies made explicit that a combination of historical events, local realities, social norms, and household dynamics in which women negotiate their participation in paid labour produces heterogenous outcomes which are co-constituted during processes of marketisation (or commodification) (Katz, Citation2001; Kabeer, Citation2013). However, although these authors have touched upon the issue of care, the significance of social reproduction (SR)—namely the set of activities on, and relationship between, the processes of producing labour power (Ferguson et al., Citation2016; Kunz, Citation2010), and the processes of producing value for capitalism (i.e. maintaining life)—vis-à-vis modalities of reproductive work, patriarchal institutions and norms, is not always explicit. Hence, this article develops a theoretical framework converging SR theory and theories of varieties of gender regimes of patriarchy to understand the everyday reproduction and maintenance of commodity labour power within the totality of non-market institutions, relations, forms and processes associated with ongoing social and natural life. Starting from a broad understanding of patriarchy as a ‘system of social structures and practices in which men dominate, oppress, and exploit women’ (Walby,Footnote1 Citation1990:214), I deploy the concepts of domestic and public patriarchy to analyse the gendered practices of food production and reproduction in Uzbekistan, in order to unpack family-led and state-led forms of dispossession, oppression and exploitation of women’s work. How, why, and in which patriarchal regimes women perform reproductive work is often given as exogenous and not understood as part of an organic system which defines and organises both work and life at the international, macro, meso and micro level. Along these lines, by engaging with the IPE of everyday life, the article also investigates how women navigate and resist market and non-market pressures during the ongoing process of Uzbek agrarian marketisation. Women in Uzbekistan are major food producers and core contributors to food availability (Agarwal, Citation2016:311) but are also involved, formally or informally, in food commercialisation. I argue that women have always been dispossessed but that processes of marketisation, shaped by multi-level and time-specific patriarchal dynamics, have changed the modalities of dispossession, which can be enlightened through a social reproduction framework. In conclusion, this paper, by offering a gendered discussion on the way food is produced, consumed and distributed beyond the circuit of marketised commodities, offers a useful lens through which to understand the tensions occurring across marketisation and social reproduction. The paper is organised as follows. Section 2 discusses the literature on patriarchy and social reproduction to gender the analysis of agrarian marketisation. Section 3 outlines the methodology. Section 4 discusses women’s position in the marketisation process. Section 5 analyses the empirical evidence on productive and reproductive work in rural Uzbekistan. Section 6 concludes by discussing the inadequacy of the available policy solutions proposed by the contemporary neoliberal governance to address the structural challenges of social reproduction in processes of agrarian marketisation.

Agrarian marketisation, patriarchy and social reproduction

Although marketisation was recommended by development organisations because it was considered instrumental to economic development and gender equality (Duflo, Citation2012; WB, Citation2012), it has often led to the worsening of women’s material conditions. Indeed, marketisation often corresponds to an increased commodification of social reproduction activities, which creates time and money pressures upon women (Cousins et al., Citation2018). MarketisationFootnote2 marks the structural passage to a mode of production based on domination and expropriation of labour-value as necessary labour time for social reproduction to surplus labour time for capital accumulation (Bhattacharya, Citation2017). In rural areas, marketisation entails a process of labor specialisation, commodification of labour (Arun, Citation2012; Razavi, Citation2003, Citation2009) and nature (i.e. land or food) and monetisation. Such a process alters the access to means for subsistence, such as land and inputs which shape labour-time and, hence, gendered dynamics of accumulation and exploitation. Agrarian change entails a struggle for accumulation of resources, which can reorder intra-household relations or asset distribution in ways that can upset the household head and have different impacts on men and women (Cousins et al., Citation2018; Kabeer, Citation2013; Razavi, Citation2009).

However, marketisation does not enable gender dispossession in isolation. Public institutions and localised social norms deeply contribute to enabling patterns of exploitation and oppression which shape the circuits of social reproduction. The state, for instance, being male-dominated in its political leadership and control of economic power, regulates the patriarchal bias through which relations of production and reproduction are interlinked (Pearson, Citation2014) and organised, by, for instance, defining the pace and regimes under which reproductive work become subsidised (Kunz, Citation2010; LeBaron, Citation2010) or land individualised as a result of (re-)privatisation and enclosure. Furthermore, social policies and legal systems linked to property influence women’s position in social relations of production and reproduction.

While social reproduction theory has the merit of making explicit the mechanisms of material exploitation and the dialectic synergies between productive, informal and reproductive labour relations performed by both women and men in capitalistic social relations (and related process of accumulation), it does not necessarily untangle the context- and time-specific institutional domains and structures—both bottom-up and top-down—that shape social reproduction outcomes, for instance, during processes of agrarian change. In contrast, theories of gender regimes enable an unpacking of the multiple forms of patriarchy, because they allow an understanding of the context-specific, male-dominated exclusionary institutional structures and norms which co-shape patterns of gendered oppression. Nevertheless, contrary to social reproduction theory, theories of gender regimes do not always make explicit the material determinants of exploitation and extractions in labour relations, or capital expropriation, concealing the inequality resulting in the economisation of surplus-value creation across productive and reproductive work. In other words, theories of gender regimes scrutinise the deviances of the teleological outcomes moulded by the social reproduction of capitalism. Thus, two such combined strands of theories are crucial for untangling how the connotation of women’s work, as a totality, relies on, and contributes to, social and economic inequalities during the marketisation of life. Agrarian marketisation in this matter creates gendered social stratification through tasks and rewards, shaping polarisation of wealth across gender.

I reflect on two forms of patriarchy: domestic patriarchy, which in this context explains the household and localised system of social relations characterised by male bias, oppression and discrimination in the house and in the local community,Footnote3 and public patriarchy, which echoes the collective forms of institutionalised appropriation, control and expropriation by the state by means of its regulatory and social policies, but also through the market (Brown, Citation1981). The patriarchal state is the central agent which enables a system of public patriarchy constituted not only by the state itself, but also by a set of market, non-market and non-public agents and institutions. ‘The identification of different [and context-specific] forms of domestic [and public] gender regime is particularly important in the global South, where gender-based exclusionary strategies have a greater impact upon state-formation, capitalist development, civil society, and culture and religion in comparison to the global North’ (Kocabicak, Citation2020:1). Historically, through its gender-neutral regulatory power, the state has been a promoter of gender inequalities, dispossession and discrimination (Naidu & Ossome, Citation2016; Walby, Citation1990) which trickled down to lower levels and helped to keep patriarchal exploitation of labour within the family (Kocabicak, Citation2020:2). Therefore, although social reproduction is embedded in domestic patriarchal domains such as the family, which exercise material exploitation of women, it is important to also consider the linkages with inter-scalar forms of oppression and subordination at meso and macro levels. Such inter-dependency produces time and context-specific outcomes which, as Elson and Pearson suggest (Citation1981), decompose, recompose, and intensify women’s work and subordination through multiple forms of domestic and public patriarchy. Hence, due to a combination of women’s weak bargaining power within the household, and their pre-assigned roles within public and domestic patriarchal norms, women tend to end up in low-paid, informal and seasonal jobs in the market, possess fewer capital assets and take on more domestic work.

These gender-unequal outcomes suggest that the peasant household is not a homogenous institution with aligned interests of production and exchange and an equal intra-household division of labour (Harriss-White, Citation1990; Razavi, Citation2009) but the object of tensions and contradictions which make visible the way social reproduction is performed, for example through food. When looking at agrarian social relations of food production and reproduction in contexts of marketisation, agrarian political economists offer useful analytical starting points for ‘engendering’ its understanding. Bernstein refers to subsistence as the production by household farmers of food used for social reproduction (2010:3), which emphasises that in contexts of incomplete marketisation, the objective of domestic labour is the final consumption of the non-commodity produced. Domestic labour produces and consumes non-commoditised food for and through its use-value, thus does not pass through capitalist mechanisms (i.e. exchange-value) of exploitation and dispossession. This ‘productivist’ framework could help make explicit the crucial role of women’s work for the maintenance of rural social reproduction; however, it bypasses three crucial points. First, it hides which household member performs, and which patriarchal institutions enables (or forces), the production of such non-commoditised goods and services. Second, it does not make explicit that such reproductive work is value-generating beyond its use (Mezzadri, Citation2019), which is a central analytical point of social reproduction theory to understand the political and economic importance of women’s work during processes of marketisation. Third, it does not acknowledge the biased perception of the role of women’s work by men and by society at large.

By tackling those analytical limits, feminist agrarian political economists denounce the neglect of the operationalisation of social reproduction. Women hold a crucial role in the rural economy by overwhelmingly dealing with reproductive work such as food preparation, child and elderly care, and shelter-related maintenance (Cousins et al., Citation2018; Katz, Citation2001; Razavi, Citation2009). However, women also engage in several informal, unpaid yet productive duties within the household, such as small-scale garden and animal care; fetching wood and water; petty trading and informal petty trading (Naidu & Ossome, Citation2016; O’Laughlin, Citation2013). What women’s work produces, through both material food crops and immaterial services within the household and for the capitalistic system, holds a use-value realised in the process of consumption of the same services and goods, and a labour-time value, exemplified by the opportunity cost of not being engaged in remunerated forms of work. Thus, women’s work entails value but it is economically and politically unvalued because it is performed outside the marketised forms of labour relations of production.

In assessing how processes of agrarian marketisation interplay with social reproduction domains, gender economists describe and classify—in a rather descriptive way (Stevano et al., Citation2019)—productive and reproductive work depending on when, for how long and by whom unpaid domestic work is executed. The explanatory variables identified are usually (a) the location of the activity where the work is performed: within or outside home; (b) for whom or for what purpose: self-consumption or for sale, or for government; (c) with whom: for example, whether work is performed with household members; (d) type of activities: whether the activity is paid, unpaid or secondary (Hirway, Citation1999). However, in agrarian settings, non-commodified rural labour for subsistence and labour exchanged for cash are often mutually constitutive and not spatially and temporally separate, which problematises even further the dichotomic taxonomy of productive versus reproductive work, and invites us to reinterpret the implications of work performed by women, including its connotations vis-à-vis the socio-economic totality of life, namely social reproduction.

Unpaid domestic work is not only delegitimised because its value creation is not financially rewarded, meaning its ‘proxy value’ is not tagged to a price through which it can be bought and sold in the market, but also because the time worked to support social reproduction is not cost-free for those who perform it. Those activities entail an extensive use of non-commoditised time, which not only problematises the standard analysis of empirical studies on work and gender, but also invites a more sophisticated reflection on the multiple forms of work in, outside, and between market value (i.e. price-wages). Indeed, such epistemological categories affect the way productive and reproductive work is (not) recognised in society and bypasses the understanding of how surplus value is created, used, and expropriated outside and inside the household. Hence, in contexts where fluid informal labour and domestic work subsidise marketised and non-marketised work and nature, women’s contribution to agrarian production is left implicit because it is harder to categorise and legitimise as co-determinant of marketisation outcomes. Such simplistic ontological taxonomy needs to be overcome in order to bypass the dichotomy of patterns of capitalist accumulation versus social reproduction domains (Cousins et al., Citation2018; Mezzadri, Citation2019). Through empirically informed analysis, we need to strengthen the recognition of women’s work as co-constitutive of (and exploitation determined by) the social reproduction of the household but also of the capitalistic mode of production at large (Mies, Citation1986; Munro, Citation2019). So far, analyses of agrarian marketisation have rarely made explicit the interlinkages between the commodification processes of food and labour as sources of accumulation and how such processes reconfigure the ensemble of women’s unpaid (de-commodified), productive, informal and reproductive work (Razavi, Citation2009:198). Yet, these are fundamental social relations through which gender oppression can be assessed because they exemplify the imbalances of reproductive work responsibilities and the patriarchal forms of oppression though which social reproduction is maintained.

This article brings these levels together and analyses them as a social totality. The reconfiguration of social reproduction is underexplored in the context of post-Soviet transition; thus, food can provide insights into understanding the complexity of social reproduction in everyday agrarian change. In particular, the Uzbek case study helps shed light on the complexity of social reproduction informed by the reproductive and productive work linked to food, and how its outcomes are moulded by public and domestic patriarchy.

Methodology

Due to the scarcity of secondary data on Uzbekistan, I collected primary data, both qualitative and quantitative. My fieldwork took place between August and December 2015 in the Samarkand region, and in Autumn of 2018 to follow up some stakeholder interviews in Tashkent. In Samarkand, I conducted a farmers’ survey with a stratified sample. The criteria of stratification were based on classifications used in national and regional statistics, and on previous surveys conducted in the country in 2010, in which dekhans (small household plots) and fermers (big farms producing either cotton, wheat of fruits and vegetables) were divided based on the crop produced, forms of land tenure and labour relations (Veldwisch & Bock, Citation2011; Veldwisch & Spoor, Citation2008). The survey does not pretend to be exhaustive of the micro-complexities of the farming population; however, complementarily with the other methods, it offers an insightful perspective on the main patterns around gendered relations during the recent processes of marketisation. Out of 120 interviewees, 16 respondents were women (). It is not a coincidence that women are not represented among fermers’ managers: this category of farmers is dominated by men, which is why the women interviewed were predominantly waged farm workers and household farm workers (dekhans). Yet, including both managers and non-farm managers in the analysis enabled an understanding of the material differences and social relationship between them. At the scoping stage, I selected various districts in the Samarkand region to identify fermers that produce cotton, wheat and fresh fruits and vegetables (FFVs). This criterion allowed an understanding of different relations of production and reproduction attached to the different marketisation of the crops. Samarkand was chosen because it represents well the different strands of crop marketisation taking place in Uzbekistan. Interviews started from either the administrators at the local administrative office or from a farmer and continued through a snowballing process.

Table 1. Survey sample strata by gender.

Two local enumerators, a woman and a man employed at the Agrarian University of Samarkand, supported the process of data collection for the survey in Uzbek and Russian languages. Both Russian and Uzbek are spoken in rural areas, especially among older farmers. Therefore, the enumerators were crucial in the interviews, especially for those with young farmers who usually do not speak Russian. It is important to reflect on the positionality of the researcher and the enumerators, and on the importance of having a balanced gender representation during the process of data collection (England, Citation1994). Having a woman and a man employed as enumerators allowed important observations to be made about their gendered positionality. For instance, it was noticed that, if interviewed by the female enumerator or me, women were more open to answering sensitive questions, for instance on food security. On the other hand, in venues where masculinity is dominant and reinforced through collective rituals of men bonding such as in the tea rooms (chaihona), a male enumerator, by establishing a sense of similarity, enabled a smoother conversation. It is also undeniable that during the process of data collection, being a woman raised specific issues. Respondents frequently asked during the interviews if my female enumerator or I were married, how old we were and if we had children. Being married in Uzbekistan gives social legitimacy to women, which confirms the relevance of domestic patriarchal pressures on women. Thus, such a context certainly risks affecting the power relations between the female research assistant and the respondents (England, Citation1994).

In Tashkent, I lived with an extended family from Samarkand, composed of a retired married couple, her daughter who is a single mother, and her little son. I conducted participant observations, which helped me to write a diary where I reported information about cooking, food consumption and taste, women’s work, and gender relations within the household, which I used as background information. The family members had also been farm workers; thus, they shared life histories and often talked about the differences between Soviet and post-Soviet times, sometime with nostalgia. I also conducted direct observations in two agro-processing companies. The observations helped to shed light on the gendered division of labour in the factory, women workers’ conditions and the tasks they specialised in. I conducted semi-structured and unstructured interviews with key stakeholders and policy makers in the country,Footnote4 as well as in-depth interviews with women in rural areas. I interviewed these women in Russian language, while conducting the survey, or while performing daily activities such as food shopping at the bazaar, taking the buses or taking collective taxis. By triangulating empirical evidence, I used the qualitative primary data from interviews and observations to fill the gaps of the survey, and complementing it with secondary historical and ethnographic sources, I untangled the contemporary gendered inequalities attached to social relations of agrarian production and value creation, through labour, food and land.

Women in the Uzbek marketisation process

This section aims to provide a historical context to illuminate the changing dynamics of women’s dispossession and to enable an up-to-date analysis of gendered relations of production, use and exchange in agrarian Uzbekistan. The Uzbek government, by shaping market transition, has continuously affected women’s role in social reproduction in many respects. During the Soviet Union, women’s access to formal labour markets was incentivised and enforced by affirmative actions and a quota system. The extensive public investment in education resulted in 99% of the population becoming literate (male 99.6% and female 99.2%), confirming the ‘progressive’ heritage of universal education implemented during the Soviet era (Kandiyoti, Citation2007).Footnote5 Every public institution had to reserve 30% of their posts for women, who were also encouraged into public and political participation. This system changed the private and public positions of women compared to pre-Soviet times, since local social norms had disincentivised women from working outside the house, especially in rural areas (ADB, Citation2014). However, in the Soviet Union, women were the object of an emancipation paradox (Kandiyoti, Citation2007). The promotion of women’s employment in the formal sector did not reduce their motherhood responsibilities and reproductive duties within the household (Kandiyoti, Citation2007). Yet, social infrastructures, both formal and informal, were set up to support social reproductive tasks, for instance on health, childcare and education. Such an institutionalised system of social support provided women with a ‘significant source of salaried jobs and non-farm employment’ (Kandiyoti, Citation2003:248) but also with support for their social reproduction duties.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union and Uzbek independence in 1991, the ‘pink quota’ system disappeared and many jobs in the public sector were lost, leading to an informalisation and casualisation of employment (Kandiyoti, Citation2003). As a result, marketisation deprived many women of formal employment—especially in high-skilled jobs—and of social rights, leading to a revival of conservative practices of Islam (Welter & Smallbone, Citation2008) which, by shrinking women’s opportunities for evading family control, led to gender segregation (Kandiyoti, Citation2003). The commodification of the means of production translated into higher costs of social reproduction and lower living standards, especially for women. Market transition overlapped with the ‘de-Sovietification’ of gender norms, especially in rural areas (Cleuziou & Direnbergerb, Citation2016). The newly-independent state developed a gender narrative which emphasised the return to ‘lost traditions’ and to the women’s realm in the domestic sphere (Kandiyoti, Citation2007). Feminist authors have labelled this process the ‘victimization of women’ (Buckley, Citation1997). Data shows that between 2007 and 2015, women’s positions in management roles as well as in male-dominated sectors such as energy and the automotive sector declined, while remaining stable in traditionally female-dominated sectors such as health and education (82% and 72% respectively—State Committee on Statistics n.d.).Footnote6 Furthermore, the disrupted system of social protection engendered socio-economic dispossession and restrained the ability of women to work outside the home (Romanova et al., Citation2017). Most of the financial support for childcare, healthcare or family care provided by the Soviet state disappeared or was reduced to a minimum (Cleuziou & Direnbergerb, Citation2016:198). Hence, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the shrinkage of welfare and public services led to the rise of oppressive gender norms that skewed the domestic division of labour against women. In this context of state withdrawal, government intervention also shaped the biased ways in which women and men access agricultural resources and assets. The commodification of social services resulting from the collapse of the Soviet system and the individualisation of the social relations of production led to the devaluation of women’s productive and reproductive work in two ways: first, through the ‘informalisation of work’ for social reproduction, which passed from being paid and formalised by the state through public services to being unpaid and relegated to the domestic sphere, and second, through the social de-legitimisation of the same work, now treated as part of women’s domestic duties. Thus, the changing forms of state involvement at the level of the household, of the local market and in the public domain, by altering the strategy of social reproduction (Kunz, Citation2010), has contributed to disempowering women domestically, socially and economically.

In rural areas, the collapse of the Soviet Union reconfigured social reproduction through the way land and food were produced and accessed. To understand such mechanisms, it is important to situate Uzbek agrarian marketisation in the broader history of mono-crop cultivation on which agriculture relied during the Soviet time. During the Soviet Union, besides subsistence farming, land was mostly cultivated with cotton through collective and state farms by work brigades (Atta, Citation1993), which got diversified only in the early 2000s with the integration of wheat, fruits and vegetables (Lombardozzi & Djanibekov, Citation2021; Lombardozzi, Citation2020b). Workers whose labour was organised by the state through public procurement received material compensation but also benefitted from an implicit mechanism of paternalistic protection based on access to public goods (Kandiyoti, Citation2003).

Most of the studies documenting the crucial reforms linked to land and food production remain gender-neutral and include women in the black box of ‘peasant farmers’, thus obscuring public and domestic forms of patriarchal exploitation. However, women were key in organising agrarian relations of production and maintaining social reproduction, as some studies illustrated in the early 2000s (Kandiyoti, Citation2003). Indeed, agriculture was organised around a clear gendered division of labour. Most of the food consumed in rural areas was produced in household plots, mainly by women, but in connection with the collective farms. At the time of independence, such settings were providing 40% of food subsistence needs and also created opportunities for petty trading (Atta, Citation1993; Kandiyoti, Citation2003; Veldwisch & Spoor, Citation2008).

After independence in 1991, the slow process of agrarian marketisation transformed social relations around food production and consumption, but also the way women performed their work inside and outside the household. Such processes have been shaped by multiple forces of public and domestic patriarchy. For instance, the decline in public investment in rural infrastructure led not only to a reduction of employment opportunities for women, but also to a greater social reproduction burden, which translated into longer time spent gathering water and finding heating sources for the household (Romanova et al., Citation2017). The obsolescence of the physical infrastructures and the decline of social policy to support reproductive work exacerbated women’s struggles. Last but not least, the individualisation of land titles as a result of the dismantlement of the kolkhoz (state farms) and shirkats (cooperatives) did not correspond to higher levels of wage employment or business opportunities; thus, the reliance on land and self-produced food became essential in a context where public sector employment and services collapsed (Kandiyoti, Citation2003).

By providing an up-to date and empirically grounded analysis of Uzbek agrarian change, the next sections show that forms of patriarchal exploitation and oppressions keep influencing the most recent processes of marketisation, which in turn exacerbates the gendered tensions around social reproduction. The focus on food production and reproduction offers an insightful lens through which to untangle the different forms of gendered work exploitation in the Uzbek agrarian context, and the way these are performed and reconfigured as a result of life marketisation. Non-marketised social relations, exemplified in domestic work and informal labour, but also in barter exchanges and communitarian rituals, persist in rural contexts, and often intensify and reinvent their meaning during the ongoing processes of capitalist (post-Soviet) transition. The article indeed shows that women’s contribution to value-production is not made explicit, while instead being crucial to the process of capital accumulation and social reproduction (Munro, Citation2019). It does that by also understanding the historical evolution of public (patriarchal) institutions, which, as discussed so far, promoted the process of life marketisation and put pressure on social reproduction. Furthermore, the emerging forms of crop diversification and industrialisation in the food processing sector are giving rise to new, yet scattered, forms of wage labour (Lombardozzi, Citation2020a), which reproduce women’s exploitation inside and outside the workplace. In the next section, I investigate how the ensemble of marketisation processes and regimes of domestic and public patriarchy reproduce women’s oppression, and how exploitation through gendered asymmetries in nutrition, social norms that devalue women’s work and wages, and unequal distributions of reproductive work, bolstered by a disinvestment in state policy, have been co-determinants of social reproduction outcomes.

Intra-household relations and gender division of labour in contemporary Uzbekistan

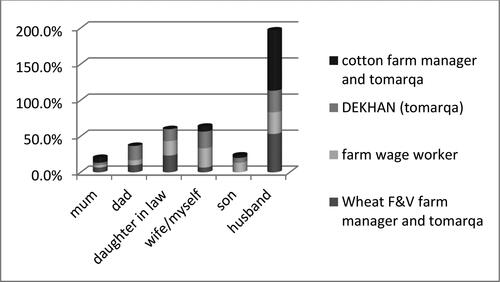

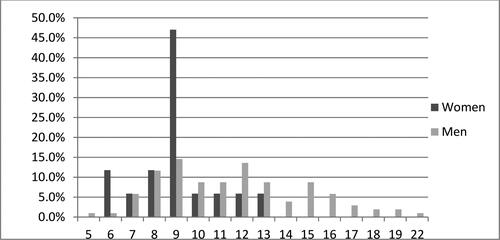

An analysis of food informed by social reproduction theory and gender regimes of patriarchy can unpack the gendered tension between (and across) productive and reproductive work. Yet, one crucial dimension of domestic patriarchy occurs through access to food. Inadequate nutrition can negatively affect the wellbeing of women and girls and it is explicatory of crucial differences between men’s and women’s power in the household. To investigate the discrimination in food consumption between men and women, although the sample size was not balanced between men and women, (which shows from left to right an increasing number of food types consumed) shows that women surveyed, in proportion, consume a smaller variety of food groups relative to men.

Figure 1. Dietary diversityFootnote13 by gender. Source: Author’s survey data.

This result is linked to various reasons: first, observations during meals suggest that men tend to get the best available meal in terms of both quality and quantity. Second, men tend to manage the budget of the household, even if women engage in off-farm jobs. The gendered allocation of money could affect which and how much food is purchased and its distribution within the household, with related gendered asymmetries in nutrition and wellbeing (Agarwal, Citation2016). Diet inequality across gender, however, is not only the outcome of individual negotiations at the household level. Constraints for women are also ascribable to public patriarchal norms, which give stronger power and legitimacy to male-dominated kinship and community. As Kocabicak notes, the patriarchal collective subject shapes politically constituted property relations in a way that sustains gendered dispossession and the patriarchal exploitation of labour within the family {and the state} (2020:3). For instance, based on fieldwork observations, men often eat away from the house in the chaihona (tearoom), which gives them access to a wider variety of food (Farfan et al., Citation2015). Such difference in dietary diversity also depends on women’s limited access to male-dominated public spaces, imposed by the Uzbek domestic patriarchy and reinforced by public control through the institutionalised barrier to women’s movement.Footnote7 Forms of resistance to unequal access to food were nonetheless observed during the process of cooking, as ingredients were chopped and eaten. This demonstrated that the burden of social reproduction is still overwhelmingly borne by women and it manifests through various forms of inequalities, which are resisted daily.

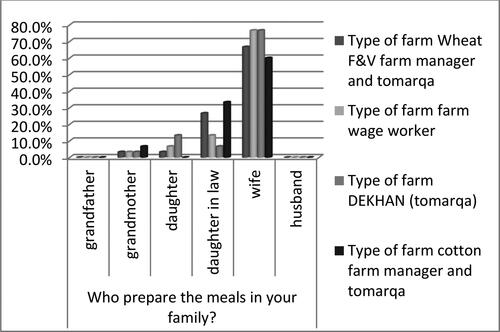

One question asked in the survey related to who goes to buy food at the market (). Although food shopping is part of reproductive work, the survey results and observations confirmed previous studies (Trevisani, Citation2008): that in Uzbekistan, buying food is a male task (performed either by the husband, son, father, etc.).

This is for multiple reasons: firstly, as mentioned above, in rural areas women’s mobility to access public spaces is often limited because public transport is scarce due to the lack of infrastructure and public services, and women usually do not own cars and do not drive. This suggests that public disinvestment in infrastructure and public transport is particularly discriminatory for women living in rural areas because, by shaping mobility, it determines women’s movements, thus proving that dynamics of public and private patriarchy are mutually reinforced. Indeed, even when women go to the bazaar to sell their crops, they are often accompanied by car by their male children, or by older male relatives, extending gendered dynamics of spatial domestic control to the public sphere. Secondly, besides controlling women’s private mobility, men tend to also control cash flow and the budget allocation within the household. Interviews with male respondents confirm that for men, going to the market to buy food is a way to avoid sharing money with women. In this sense, marketisation (i.e. food commodification) has sharpened the gender gap in access to money and food, which, exacerbated by both forces of public and private patriarchy, shapes social reproduction outcomes negatively.

By the same token, the fact that men deal with food shopping does not mean that the burden of domestic tasks is equally redistributed between men and women. Women’s work, by supporting men’s participation in the formal labour market, by managing the household’s assets and care responsibilities, is fundamental for the social reproduction of the household and society. Food requires time to prepare, time which, unpaid and undervalued, does not fall on men. Indeed, except for Plov (rice and lamb), which is a typical male cooking activity prepared for ceremonial occasions, the survey results confirm qualitative observations, namely that food preparation is women’s responsibility and is predominantly performed by wives (80%), daughters-in-law (around 10%) (kalin or nivieska) and, in fewer cases, by daughters (). Interviews with both men and women revealed that the marketisation of life is forcing an increasing number of adult women towards wage labour, both inside and outside agriculture. As a result, interviewees noted that often the reproductive work shifts to the younger female member of the household; thus, the reproductive work needed for social reproduction is still performed within the same gender lines. Yet, while young women take care of the household’s social reproduction, grandmothers still exercise a generational power on their daughters-in-law (Kandiyoti, Citation1998). Some recently married women interviewed reported that their mother-in law assigns to them heavy domestic tasks, even during and after pregnancies, which shows the complexity of women’s exploitation within and outside the household. Yet, it also suggests that the patriarchal-led oppression on which the unequal gendered division of labour is based is transmitted across generations but also sometimes internalised and exercised by women themselves.

Reproductive work serves not only short-term social reproduction needs but also long-term ones. During fieldwork, it was observed that in the cold season, to compensate for the unavailabity of FFVs in remote rural areas, women prepare food conserves of fruit juice (kompot) and pickled vegetables (marinotvka of tomato, carrots, and cucumber). This food practice has important implications because it sheds light on the close interconnections between marketisation, patriarchy and social reproduction outcomes. Firstly, food conservation, by offsetting potential shocks linked to food seasonality and by also being rich in probiotics, is a coping strategy that contributes positively to the nutritional status, and thus to the social reproduction, of the household. Secondly, such time-intensive unpaid domestic work generates value outside the market but has consequences for market demand and supply as well. In particular, the lack of demand for wage labour forces women into domestic work, who engage with informal yet value-producing survival strategies. Third, the slow liberalisation of the Uzbek food system leads to a ‘lag’ in food supply, which in turn makes necessary—and possible—the preparation of time-intensive food, especially in winter. Thus, the persistence of women’s reproductive work,Footnote8 and so the value generation attached to it, is crucial for social reproduction in two directions. By compensating for the lack of wages and commodities in the market (due to low purchasing power), such value creates an inflationary effect on food as a commodity, and a deflationary effect on wages. In other words, the existence and persistence of women non-wage labour, on the one hand, does not boost the demand for food commodities and slows down the marketisation of social reproduction; on the other hand, it subsidises wage labour. Similar patterns are reinforced by the lack of labour-saving devices, such as washing machines, dishwashers and sewing machines, in the household. Therefore, state-regulated marketisation (Lombardozzi, Citation2020a, Citation2020b), negotiated by domestic and public patriarchy, defines and shapes the way women engage with the market and its social forms of money and work.

Furthermore, fieldwork observations unveiled that women often marketise homemade food. For instance, women bake lipioshka (bread) at home for domestic consumption but often also sell it in the bazaars, thus co-generating both use- and exchange-values with the same bread. Interviews confirm that in agrarian contexts, it is difficult to draw a clear line between work executed for social reproduction and labour exchanged for money and accumulation, and value is continuously and simultaneously created both inside and outside the market. Hence, a distinction between productive and reproductive work is impossible to make, especially when such categories shape social reproduction in their totality. Furthermore, women deliberately use this space-time work fluidity to develop dynamics of resistance to escape men’s control over their limited, or curtailed, financial resources, such as women-led barter. Through women-only local gatherings called gaps, women join ‘public life’ but also seek mutual support (Kandiyoti, Citation1998). Interviews revealed that women barter food, or domestic assets such as sewing machines, in exchange for favours or information, but also engage with informal credit scheme organised by and for women only. By bypassing formal monetary forms of exchange, they not only generate dual value, one for reproduction, one for exchange (Mezzadri, Citation2019), but they also resist both the circuit of marketisation and patriarchal control.

Such observations hold two further theoretical implications. They disprove the neoclassical household model, which assumes that time allocation is determined by efficiency and prices, instead of looking at the mechanisms of demand in the market and power within the houshold and the state. The disinvestment in the public productive system creates indeed a dielectic which enables the domestic patriarchy to impose women’s segregation because reproductive work-time is valued less than others, which exposes them to hierarchy of exploitation (Mezzadri, Citation2019). Second, it proves that women’s work and social reproduction practices are at the heart of the process of capitalist accumulation through multiple forms of value creation, which in turn leads to gender-biased outcomes of accumulation.

Another case in which women’s work is embedded in the blurred circuits of life marketisation is through the appropriation of the ‘commons’ (Cousins et al., Citation2018), which is again enabled by the state regulation of land. At the end of the cotton harvest, women pick bushes for fire, cotton seeds and residuals of cotton flowers in the fields. These informal practices are based on the free appropriation of ‘common goods’ and uncoupled from the logic of private accumulation (Lombardozzi, Citation2020b). Hence, the slow pace of commodification of the ‘commons’ is resisted through the appropriation of natural resources by women and contribute to support social reproduction. Yet, such a non-marketised economy is reproduced through the extra exploitation of women’s labour-time for use-value, which worsens women’s double burden (Naidu & Ossome, Citation2016) and reinforces the invisibility of women’s work (Himmelweit & Mohun, Citation1977). These practices are indicative of the perpetuation of a relatively closed agrarian market which, as discussed above, on the one hand does not create paid jobs, but on the other hand, through the gendered control of work, helps maintain monotonous patterns of consumption and value creation which rely on minimal forms of commodified labour and food to sustain social reproduction. In this sense, the Uzbek agricultural sector continues to function as an economic and social buffer for rural communities’ social reproduction.

Yet, women make a big contribution to formal agriculture. While men are typically hired in full-time farm jobs and involved in the use and management of technology and machineries, women are mostly confined to unskilled daily or seasonal labour. Such gendered division of agrarian labour has persisted since the Soviet times, as women were specialised in low-skilled tasks such as weeding, harvesting and planting, whereas men dealt with machineries and higher-skilled tasks (Trevisani, Citation2008). Yet, tasks and rewards in Soviet times were less individualised, which left women less exposed to forms of institutionalised patriarchal discrimination. Since the Soviet time, a distinctive state-enabled task is cotton picking. Quasi-free labour is mobilised from the education sector (nowadays, mostly university students—the government arranges travels and provides very basic shelter and meals during the cotton-picking season) or from the public administration sector, but poor women are also recruited through local networks (Lombardozzi, Citation2020b). During my fieldwork, I did not register any substantial differences between the daily wages paid to students and to the women hired in the ‘free market’. Research has estimated that cotton picking represents on average 12% of women’s annual income and can reach 30% for the very poor.Footnote9 This confirms once again that women’s exploitation and discrimination is realised within the household through multiple forms of private patriarchy, but it is also reinforced by broader political, historical and economic state policies—i.e. public patriarchy—which, by shaping labour relations and production, co-opts women’s labour and impacts their wages. Informal conversations with women in the field confirmed that these jobs are not desirable, but the lack of alternative forces them to pick cotton, even if it is in exchange for meagre pay.

Furthermore, previous surveys underestimated women’s contribution to labour. Authors denounced the scarcity of reliable and comprehensive data on women’s labour because that is often considered seasonal, or unremunerated, hence ‘invisible’ (Agarwal, Citation2016; Doss, Citation2010; Lastarria-Cornhiel, Citation2008). Fieldwork observations confirm that, because men take care of large-scale farms (fermers), women not only deal with domestic reproductive work, but also manage the tomarqua, the small household plot present in every rural and peri-urban household (dekhan) and usually take care of the livestock, thus playing a crucial role in food production, processing, and preparation. The tomarqua is the food basket of rural Uzbekistan because it is where most fruits and vegetables are sourced and livestock is grazed (UNICEF, n.d.; UNDP, Citation2017); thus, it is a key source of nutrition and key for social reproduction. Furthermore, women play a crucial role in the fermer by cooking for the workers, or by helping the workers in case extra work is needed, especially for cotton (weeding, picking and thinning cotton bolls). The overlapping of productive and reproductive work proves that women cover multiple spatial but uni-dimensional timed activities at home, in the household plots and in the big state crop or commercial farms, which are hard to separate and rarely acknowledged for their value creation for social reproduction.

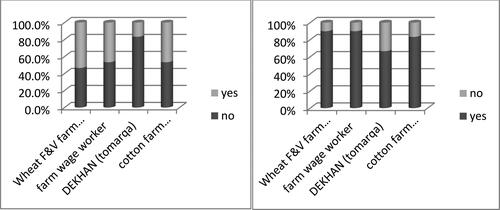

Although such gendered labour dynamics are clearly visible on the ground, men’s biased perception of women’s work, which is seen as something circumscribed to the private sphere, persists. For example, when asking farmers whether their mothers/wives worked, many men answered ‘no’ (). However, it was necessary to disentangle this answer. Indeed, when the answer was ‘no’, when I asked to specify whether the woman was rather ‘helping’ with the farm, ‘yes’ was the predominant answer. Thus, women’s role in productive activities is perceived as ‘help’ rather than work and thus underestimated when it comes to redistributing material and financial rewards within the household. Interviews with men confirmed that care responsibilities and any kind of work done by women is not perceived as essential to the reproduction of the family or society, but simply seen as women’s ‘duty’.

Figure 4. Does your wife/mother work outside the home? (L) Does your wife/mother work on the farm? (R). Source: Author’s survey data.

The lack of acknowledgement of women’s labour—as a value creator—in local, private and public domains perpetuates the oppression of Uzbek women in multiple ways. First, in the way information, inputs and assets are distributed (Agarwal & Herring, Citation2013); second, it affects women’s abilities and power to negotiate intra-household resource allocation (Doss, Citation2010). Third, it raises issues around the recognition and classification of women’s work in society and the consequent political and material rewards redistributed to them (Agarwal, Citation2016). Unpaid labour, by making their value creation invisible, excludes women from the means of social reproduction but also from any possibility of saving or accumulating.

One of the most evident forms of women’s discrimination during the process of Uzbek marketisation is related to land. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, land, as well as other income-generating assets, remained non-commodified and owned by the state, but its access was individualised through use-rights (Kandiyoti, Citation2003). Interviews confirm that land titles are almost entirely held by men, although it is not jurisdictional barriers that prevent women from managing a state crop farm (Romanova et al., Citation2017). Fieldwork observations conducted in many hokimiat (local administration offices) show that women rarely or never participate in farm management meetings (Kandiyoti, Citation2003). In one of the interviews in the Ishtihan district, a cotton farm manager revealed that because he had many businesses in construction and car repair, his wife acted as a figurehead, being the official manager of his large farm. These kinds of ‘anomalies’ reveal that, even in domains of the social relations of production where state patriarchy is not explicitly discriminatory and women have equal rights to land titles, structural gender inequalities still occur due to discriminations imposed by domestic patriarchal norms. Being excluded from the circuit of land management also means that women suffer a divide with regard to access to credit, and other critical inputs, such as tractors and fertilizers, for enhancing their productive capacity. Land indeed plays a crucial role in shaping both class differentiation and social reproduction (Cousins et al., Citation2018) and therefore women’s conditions of subordination (Agarwal, Citation2016). This restriction also leaves women unable to access market opportunities in higher-value sectors and gain better earnings, thus forcing them to keep working in low-productivity house plots. Such examples further confirm that the unequal reproductive workload, weak bargaining power within the community, and unequal resource distribution are reinforced by a dialectic made of multi-scalar regimes of patriarchy.

The slow-paced Uzbek marketisation (Lombardozzi, Citation2020b), by preventing a deeper formal division of labour, does not redistribute reproductive tasks, which perpetuates a system of production and exchange based on male-controlled income and male-biased spending patterns. However, among richer households, women tend to be employed in services or in the public sector. Survey data shows that women’s off-farm jobs are still circumscribed to nurses and teachers. Yet, based on interviews in rural areas, even if women engage in formal paid jobs, they are often expropriated of their own wages by their husband or family, who often invest the money in the farm. Akida,Footnote10 a 35-year-old teacher who I interviewed, lived in a small village 80 km away from Samarkand. She lost her mother at a young age, and while her younger sister managed to go to study in Germany, she could not oppose her father’s ‘suggestion’ to marry her younger cousin because, being 28 years old, she was getting ‘old’. She is now married, has two children and takes care of her husband’s six-member household, while working as an English teacher in a school. Yet, if she needs to buy a jacket for herself, she must ask for money from her husband, a university student. This story seems to confirm the point made by Folbre (Citation1994): paid work can improve women’s bargaining power (and consequent purchasing power) but can also expose them to dynamics of expropriation, which exemplify the widespread lack of recognition of any kind of women’s work, regardless of the marketised value attached to it. As discussed earlier, such forms of expropriation and oppression often incentivise women to build female solidarity to enable actions of micro-resistance. The establishment of local female associations allow women to spend longer time outside the house and offer mutual assistance to each other.

Since 2005, a new wave of marketisationFootnote11 in agriculture has taken place, through a series of state–led reforms which led to the diversion of land from cotton to FFVs and to the establishment of agro-processing firms in the peri-urban areas of the country. These new venues of private capital accumulation are creating new wage-labour opportunities (Lombardozzi, Citation2019)Footnote12 and recent data show that women are increasingly active in the agro-processing industry (Romanova et al., Citation2017). Based on observations and interviews in one of the biggest processing companies in the Samarkand region, Agromir, women were 80% of the workforce. While men work with machinery, transport and logistics, women work in manual activities of the preparation phase (i.e. cleaning, filling, dealing with raw material). According to semi-structured interviews, the average wage for women is 30.000 sums per day for a 12-hour shift in a 24-hour production cycle, on average 1/3 less than a male wage. Workers face long working days far from the household, which require long periods of standing, no days off and limited opportunities for training and skill development. Thus women, even when integrated into the formal circuit of wage employment, are exploited more than men through the wage gap and because of their professional segregation in unskilled and manual work (Elson & Pearson, Citation1981; Lastarria-Cornhiel, Citation2008). Indeed, these formal jobs in the agri-processing sector incentivise the demand for gender-specific skills which expose women to new venues of labour exploitation and vulnerabilities (Barrientos et al., Citation2016). However, these jobs offer women an official working status, a regular wage which is higher than the farm wage, access to transport and canteen services, and social protection which can contribute to developing a sense of community, identity and social solidarity (Pearson, Citation2014).

Those forms of proletarisation could create an opportunity for organising, and potentially re-negotiate their working conditions within and outside the household (Kabeer, Citation2012; Mezzadri, Citation2016). In contrast, women who cannot reach those firms remain stuck in their roles of house-workers and ‘informal’ care givers without a source of income. Yet, unless state policy reinvests in public social services and incentivise the shift of domestic patriarchal norms to redistribute tasks across gender, working outside the house will worsen women’s position vis-à-vis men (Kabeer, Citation2013). A stable cash income or a formal job is not a reliable indicator of women’s empowerment, if this does not occur alongside investment in social care to redistribute the burden of reproductive work across society and the state, and through the acknowledgment of the value produced by women’s work for social reproduction. Empirical evidence shown so far confirms that the extraction of female labour value is guaranteed by multi-level forces of patriarchy linked to the market, the family and the state.

Untangling the gendered dimensions of market transition

In poor agrarian contexts, marketisation—or market transition—determines an alteration of asset distribution and livelihood diversification, which also happens across divisions of gender (Cousins et al., Citation2018). However, in the analysis of such a complex transition, very often the gender dimension has been overlooked (Harriss-White, Citation1990; Kandiyoti, Citation2003), and it includes shifting patterns of gender relations around assets and work. Looking at the gendered work of Uzbek agrarian households, this article has uncovered tensions between the transformational forces of marketisation and inter-scalar forms of patriarchy in which gendered social relations operate, and how the negotiation and resistance between the two generate value, hence shape social reproduction outcomes. This article has unpacked the mechanisms through which private and public patriarchy, by dialectically defining the drivers and dynamics of capitalistic accumulation, shape value-generating work and reproduce gendered inequality during processes of marketisation. Along these lines, it has investigated the gendered division of labour within the household and, by challenging the false dichotomy of productive and reproductive work linked to food provision, preparation, production and consumption, it has untangled women’s work on the edge of informal, productive and reproductive domains. Food, through the way is produced, provisioned and accessed as both commodity and nourishment, has provided a useful lens through which to understand how women’s work is exploited for social reproduction, and how the value it generates is hidden within exploitative economic and social forms. Gendered social relations of production are embedded and re-negotiated in the economic transformation, which affects the formation of commodities and non-commodities (Polanyi et al., Citation1957).

‘In agrarian settings, the manner in which social reproduction occurs can facilitate accumulation, but in other cases act as a key constraint on accumulation’ (Cousins et al., Citation2018:1081). In the Uzbek agrarian setting, the persistence of women’s burden of social reproduction can be explained by reversing the chain of causality of Cousins’ quote, namely that the way through which accumulation occurs can facilitate social reproduction practices, but in other cases act as a key constraint to social reproduction. Women’s oppression is determined by two intertwining factors: firstly, the slow pace of accumulation has perpetuated semi-proletarianisation and informal labour relations outside the household, which have only marginally altered local labour relations and the gendered distribution of reproductive work. Secondly, a revamp of public and domestic patriarchy has put women in a subordinated role within the household. As a result of institutionally enforced dynamics of gendered material exclusion, namely the dismantlement of the Soviet system of social service provision, in Uzbekistan women’s work and responsibilities tend to be confined to the informal and domestic sector, with no remuneration and limited decision-making power within the family and community. In other words, state policy, or the lack of it, has paradoxically enabled the conditions for oppressive domestic patriarchy to be reinforced. Such tensions have made gender inequalities reproduce themselves under different political and socio-economic conditions. This case study indeed confirms that the history of women’ empowerment is not unidirectional, and it can go backward as a result of political-economic reforms and historical shocks that organise social reproduction.

Furthermore, recent job opportunities in the scattered agro-processing industry are shaping new labour patterns which are absorbing women into new, patriarchally-dominated circuits, also dominated by private capital. The new processing industry might be a venue to renegotiate bargaining positions and challenge gender privileges in rural Uzbekistan, through labour organisation. However, processes of capitalist transformation are deeply entrenched in gender inequalities (O’Laughlin, Citation2007) and local dynamics of exploitation remain, and affect daily social reproduction in and outside the household. Despite macroeconomic figures showing a steady growth of the Uzbek economy and a pattern of structural transformation, little has changed with respect to what was documented by earlier work in the early years of independence on women in agriculture, which described how precarious work, patriarchal domestic norms and the retreat of public services negatively affected women. The most vulnerable fringe of rural women has seen little or no benefit at all from the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Whether in upcoming years marketisation will include or exclude women will depend on both top-down (capital-state) and bottom-up (labour) patriarchal forces, which are not mutually exclusive but rather, mutually constitutive. First, the implementation of state policies which regulate both local and global capital accumulation and its modalities of local surplus labour extraction, along with the establishment of labour protection legislation (minimum wage, trade union legislation etc.) and social security. Second, the forging of bottom-up labour organisations, which challenge patriarchal oppression, discrimination and exploitation and channel the labour force and their possibility to organise as a political identity. The dialectic of these two political forces would determine not only how women’s work in Uzbekistan will integrate into the gendered global division of labour, but also how value will be created and treated, and who will benefit from it. Gendered value creation is indeed dialectically explained by productive and reproductive work and by the informalities in between, but also by the institutional national and international landscapes in which capital unleashes and defines the pace and trajectories of market transition.

An exhaustive feminist IPE analysis of social reproduction during processes of agrarian industrialization, but also capitalistic development at large, has to encompass an understanding of how value is created, and capital is subsidised beyond marketised forms of work.

The empirical evidence presented here thus challenges the linearity of the gender narrative promoted by the mainstream development agenda, which argues in favour of a clear association between agricultural marketisation, capitalistic development, and gender empowerment (Agarwal, Citation2016; Doss, Citation2010; O’Laughlin, Citation2013) on multiple stands: firstly, this approach sees women’s work in the economy as detached from men’s agencies and from institutionalised domestic forms of patriarchal oppression, with no mention of the role the state plays in enabling or preventing its exploitation; secondly, it treats women as a homogenous category, instrumental to economic growth, without addressing its relation to class and race (Pearson, Citation2005); thirdly, it assumes a unidirectional, linear and ahistorical trajectory of women’s empowerment as a result of market development. Finally, in the current analysis, a missing link persists between the commodification processes happening in the market and the implications for productive and reproductive work (Razavi, Citation2009), which this article has contributed to unveiling. Thus, a social reproduction framework has been useful for overcoming the dichotomy of production and reproduction and understanding the intertwining patterns of gendered value creation in and outside the marketisation process. This work has proved that relying on interdisciplinary ontological and epistemological approaches may be useful to challenge and unpack the misleading classifications around social relations of production and reproduction. Women’s work, regardless of whether it is paid or unpaid, should be understood as constitutive, at once, of both relations of production and reproduction, hence treated as a value creator. Further empirical and theoretical studies are needed to make explicit the missing links between paid and unpaid work in contemporary capitalism, and to shed light on how women’s daily life-work struggles are shaped by the political contexts in which they operate and resist.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank all the women interviewed for this research and those who contributed to make it happen, including the anonymous reviewers and the editors and participants of the special issue. This work was funded by SOAS University of London, and UCL-CEELBAS contributed to fieldwork expenses.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Funding

This research was supported by the Economics department of The School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. The fieldwork was also supported by CEELBAS-UCL.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Lorena Lombardozzi

Lorena Lombardozzi is Lecturer in Economics at the School of Social Sciences & Global Studies at The Open University, and research affiliate at Cambridge Central Asia Forum, University of Cambridge.

Notes

1 Walby conceptualises six levels of patriarchy, including a patriarchal mode of production, patriarchal relations in paid work, in the state, male violence, sexuality and cultural institutions (Citation1990).

2 Such a complex transition has often been studied within a broad framework of interpretation which includes: (a) historical roots, (b) transformation of production within agriculture and outside of agriculture, (c) the formation of classes and their patterns of accumulation, and ultimately, (d) the nature of the state.

3 ‘Domestic patriarchy’ here draws on Kandiyoti’s ‘classic patriarchy’ (Citation1988) but it extends it to emphasise the inter-scalar political economy implications of gendered work exploitation and asset expropriation. Instead, the pre-modern domestic patriarchy posited by Kocabicak in the Turkish context fits the Uzbek context only partially, with commercialisation being a key feature of the transition from the Soviet system to capitalistic marketisation.

4 ADB, UNDP, FAO, UNICEF, Women’s committee of Uzbekistan.

5 In the 1980s, feminist IPE criticised the neoliberal wave identified in structural adjustment policies because of their cuts to public expenditure, including social protection, education, health, and care (Elson, Citation2002; LeBaron, Citation2010; Kunz, Citation2010), which aggravated women’s burden of reproductive work. Also, the state changes the regulation of property rights, which shape access and control over assets and resources (Cousins et al., Citation2018), often against women.

6 Female labour force participation in Uzbekistan increased from 50% to 53% between 1990 and 2015 (Romanova et al., Citation2017). If compared with other low-middle income countries, these figures are high. However, they do not grasp complex forms of irregular and informal employment. In particular, recent data show that less than 40% of women are classified as employed. Women’s share of jobs in small and micro businesses (including farms) slowly increased from 21.7% in 2014 to 22.5% in 2016, which nevertheless does not tell us much about the quality of these occupations.

7 This situation might have been exacerbated after the Soviet system of food provision collapsed, but the data are unavailable to prove that.

8 In the Soviet time, each household was given in-kind food as compensation—oil, flour and milk—or was given vouchers to buy food. As result of marketisation, rural households increasingly rely on the market to buy food (Zanca, Citation2010).

9 Based on survey interviews and direct observation, the standard daily wage is between 18,000 and 20,000 sums per day (4US$), or 240 sum/kg of cotton picked, which in practice means that every worker gets paid per piecework.

10 Not her real name.

11 The share of agriculture in GDP declined from 28% to 17% in less than two decades. The share of employment in agriculture has been declining, from 36.2% in 1999 to 27.4% in 2016, and has now reached 26% and 18% respectively for both women and men (Romanova et al., Citation2017; Lombardozzi, Citation2019).

12 The characteristics of these new forms of accumulation in the countryside differ from the typical forms of agro-processing industry described in liberalised contexts of the Global South. FDI is very limited and foreign players engage with local production through institutional trialogue coordinated by local administrations.

13 Dietary diversity is a measurement of food consumption that reflects access of individuals to a variety of foods, and is also a proxy for nutrient adequacy.

References

- ADB (Asian Development Bank). (2014). Uzbekistan country gender assessment. Report, ADB, Manila. https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/institutional-document/42767/files/uzbekistan-countrygender-assessment.pdf

- Agarwal, B. (2016). Property, family, and the state. Oxford University Press.

- Agarwal, B., & Herring, R. (2013). Food security, productivity, and gender inequality. In The Oxford handbook of food, politics, and society. Oxford University Press.

- Arun, S. (2012). We are farmers too’: Agrarian change and gendered livelihoods in Kerala, South India. Journal of Gender Studies, 21(3), 271–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2012.691650

- Atta, D. V. (1993). The current state of agrarian reform in Uzbekistan. Post-Soviet Geography, 34(9), 598–606. https://doi.org/10.1080/10605851.1993.10640946

- Arslan, A. (2020). Relations of production and social reproduction, the state and the everyday: Women’s labour in Turkey. Review of International Political Economy, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2020.1864756

- Barrientos, S. (2019). Changing gender patterns of work in global value chains: Capturing the gains? Cambridge University Press.

- Barrientos, S., Knorringa, P., Evers, B., Visser, M., & Opondo, M. (2016). Shifting regional dynamics of global value chains: Implications for economic and social upgrading in African horticulture. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 48(7), 1266–1283. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X15614416

- Bernstein, H. (2010). Class dynamics of agrarian change (Vol. 1). Kumarian Press.

- Bhattacharya, T. (Ed.). (2017). Social reproduction theory: Remapping class, recentering oppression. Pluto Press.

- Brown, C. (1981). Mothers, fathers and children: From private to public patriarchy. In L. Sargent (Ed.), Women and revolution: A discussion of the unhappy marriage of Marxism and Feminism (pp. 239–268). Pluto.

- Buckley, M. (Ed.). (1997). Post-Soviet Women: From the Baltic to Central Asia. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511585197

- Cleuziou, J., & Direnberger, L. (2016). Gender and nation in post-Soviet Central Asia: From national narratives to women's practices. Nationalities Papers, 44(2), 195–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/00905992.2015.1082997

- Cousins, B., Dubb, A., Hornby, D., & Mtero, F. (2018). Social reproduction of ‘classes of labour’ in the rural areas of South Africa: Contradictions and contestations. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 45(5–6), 1060–1085. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2018.1482876

- Doss, C. R. (2010). If women hold up half the sky, how much of the world’s food do they produce? Background paper, 2011 State of Food and Agriculture (SOFA) Report, FAO.

- Duflo, E. (2012). Women empowerment and economic development. Journal of Economic Literature, 50(4), 1051–1079. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.50.4.1051

- Elson, D. (2002). Uneven development and the textiles and clothing industry. In Capitalism and development (pp. 203–224). Routledge.

- Elson, D., & Pearson, R. (1981). Nimble fingers make cheap workers’: An analysis of women's employment in third world export manufacturing. Feminist Review, 7(1), 87–107. https://doi.org/10.1057/fr.1981.6

- England, K. V. (1994). Getting personal: Reflexivity, positionality, and feminist research. The Professional Geographer, 46(1), 80–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0033-0124.1994.00080.x

- Farfan, G., Genoni, M. E., & Vakis, R. (2015). You are what (and where) you eat: Capturing food away from home in welfare measures (No. 7257). The World Bank.

- Ferguson, S., LeBaron, G., Dimitrakaki, A., & Farris, S. R. (2016). Special issue on social reproduction. Introduction. Historical Materialism, 24(2), 25–37. https://doi.org/10.1163/1569206X-12341469

- Folbre, N. (1994). Who pays for the kids?: Gender and the structures of constraint. Routledge.

- Harriss-White, B. (1990). The intrafamily distribution of hunger in South Asia. In J. Dreze and A. Sen (Eds.), The political economy of hunger. Volume I: Entitlement and well-being (pp. 351–424). Clarendon Press.

- Himmelweit, S., & Mohun, S. (1977). Domestic labour and capital. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 1(1), 15–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.cje.a035348

- Hirway, I. (1999). Estimating work force using time use statistics in India and its implications for employment policies. Paper presented at the international seminar on time use studies. Ahmedabad, India, 7–10 Dec. http://hdrc.undp.org.in/resoruces/gnrl/ThmticResrce/gndr/Indira_Estimate.pdf. (Accessed 27 May 2005).

- Kabeer, N. (2003). Mainstreaming gender in poverty eradication and the Millennium Development Goals London. Commonwealth Secretariat/IDRC Publication.

- Kabeer, N. (2012). Women‘s economic empowerment and inclusive growth: Labour markets and enterprise development. SIG Working Paper 2012/1, IDRC and DFID.

- Kabeer, N. (2013). Paid women, women’s empowerment and inclusive growth: Transforming the structures of constraint. UN Women.

- Kandiyoti, D. (1988). Bargaining with Patriarchy. Gender & Society, 2(3), 274–290. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124388002003004

- Kandiyoti, D. (1998). Rural livelihoods and social networks in Uzbekistan: Perspectives from Andijan. Central Asian Survey, 17(4), 561–578. https://doi.org/10.1080/02634939808401056

- Kandiyoti, D. (2003). The cry for land: Agrarian reform, gender and land rights in Uzbekistan. Journal of Agrarian Change, 3(1–2), 225–256. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0366.00055

- Kandiyoti, D. (2007). The politics of gender and the Soviet paradox: Neither colonized, nor modern? Central Asian Survey, 26(4), 601–623. https://doi.org/10.1080/02634930802018521

- Karshenas, M., Moghadam, V. M., & Alami, R. (2014). Social Policy after the Arab Spring: States and Social Rights in the MENA Region. World Development, 64, 726–739. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.07.002

- Katz, C. (2001). Vagabond capitalism and the necessity of social reproduction. Antipode, 33(4), 709–727. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8330.00207

- Kocabicak, E. (2020). Why property matters? New varieties of domestic patriarchy in Turkey. Social Politics, 27(4), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/jxaa023

- Kunz, R. (2010). The crisis of social reproduction in rural Mexico: Challenging the ‘re-privatization of social reproduction’ thesis. Review of International Political Economy, 17(5), 913–945. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692291003669644

- Lastarria-Cornhiel, S. (1997). Impact of privatization on gender and property rights in. World Development, 25(8), 1317–1333. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(97)00030-2

- Lastarria-Cornhiel, S. (2008). Feminization of agriculture: Trends and driving forces. World Development Report World Bank. http://wdronline.worldbank.org/worldbank/a/nonwdrdetail/92

- LeBaron, G. (2010). The political economy of the household: Neoliberal restructuring, enclosures, and daily life. Review of International Political Economy, 17(5), 889–912. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290903573914

- Lombardozzi, L. (2019). Can distortions in agriculture support structural transformation? The case of Uzbekistan. Post-Communist Economies, 31(1), 52–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/14631377.2018.1458486

- Lombardozzi, L. (2020a). Unpacking state-led upgrading: Empirical evidence from Uzbek horticulture value chain governance. Review of International Political Economy, 1–27.

- Lombardozzi, L. (2020b). Patterns of accumulation and social differentiation through a slow‐paced agrarian market transition: The case of post‐Soviet Uzbekistan. Journal of Agrarian Change, 20(4), 637–658. https://doi.org/10.1111/joac.12366

- Lombardozzi, L., & Djanibekov, N. (2021). Can self-sufficiency policy improve food security? An inter-temporal assessment of the wheat value-chain in Uzbekistan. Eurasian Geography and Economics, 62(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/15387216.2020.1744462

- Mezzadri, A. (2016). Class, gender and the sweatshop: On the nexus between labour commodification and exploitation. Third World Quarterly, 37(10), 1877–1900. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2016.1180239