?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This article assesses the impact of post-neoliberal governments on the level of capital controls in 17 Latin American countries for the period between 1995 and 2017. Contrary to administrations led by other left-of-center parties, especially the ones affiliated to the Socialist International, I contend that post-neoliberal parties, affiliated to the São Paulo Forum, opted to reregulate capital flows for three main reasons: increasing macroeconomic policy autonomy, favoring their constituencies, and/or giving concreteness to the rhetoric against financial and foreign interests. After proposing a new capital controls index and estimating a time-series cross-section model, I find that post-neoliberalism has been associated with an increase in the level of controls. Besides this main conclusion, I also find that larger financial sectors contribute to counteracting the reregulation of capital flows by post-neoliberal governments.

Introduction

Since the dismantlement of the Bretton Woods order, capital mobility has increased around the world through the mutual reinforcement between growing cross-border financial flows and capital controls’ removal (Eichengreen, Citation2008). As this process had repercussions for macroeconomic policymaking, political economists began to discuss the implications for the role of government partisanship. Specifically, the proponents of the capital mobility hypothesis argued that growing pressures from global financial markets would lead to a gradual erosion of the differences between right-wing and left-wing parties (Andrews, Citation1994; Keohane & Milner, Citation1996), while the supporters of the partisan approach contended that these differences would remain relevant (Bearce, Citation2002, Citation2003; Garrett, Citation1995, Citation2000; Kastner & Rector, Citation2003, Citation2005). According to the latter scholars, at least in some countries, left-of-center parties would still be more inclined to adopt expansionary and interventionist economic measures.

In the case of capital account policies, on one hand, as expected by the capital mobility hypothesis, policy uniformization has progressed after many countries took liberalizing measures during the 1980s and 1990s (Crotty & Epstein, Citation1996; Chwieroth, Citation2007a, Citation2007b; Ban, Citation2016). On the other hand, numerous countries have avoided fully opening their capital accounts, managing to keep relevant levels of capital controls, especially amid periods of financial instability (Chinn & Ito, Citation2006; Fernandez et al., Citation2016; Grabel, Citation2017).

Considering that this cross-country divergence may stem from multiple causes, this article aims to investigate to what extent government partisanship still shapes cross-border financial regulationFootnote1. Moreover, as left-of-center parties vary in their historical and ideological background, it also seeks to assess if the effect of government partisanship is contingent on the specific content of party ideologies.

In this regard, there are important reasons to pay attention to Latin America. First of all, contrary to Europe, where mainstream social-democratic parties led most of the progressive administrations, two groups of left-of-center parties went to power in Latin American countries, pushing for different and sometimes opposite economic policies. One group is composed of members of the Socialist International – a worldwide organization of social-democratic parties – like the Democratic Action (Venezuela), the Party for Democracy (Chile), and the National Liberation Party (Costa Rica). Like their counterparts in advanced countries, these parties adhered to the Third Way agenda, becoming fully committed to economic liberalization and macroeconomic orthodoxy (Kirby, Citation2003; Sandbrook et al., Citation2007; Vasconi et al., Citation1993). Another group includes the affiliated to the São Paulo Forum – a regional organization created in the early 1990s to strengthen the resistance against imperialism and neoliberalism – such as the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (El Salvador), the Movement for Socialism (Bolivia), and the Workers’ Party (Brazil). Despite having different ideologies and trajectories, these parties share the commitment with the so-called post-neoliberalism, a political-ideological project that seeks to revert or at least amend inherited neoliberal practices by redirecting market economy towards social concerns and reviving citizenship (Grugel & Riggirozzi, Citation2012; Yates & Bakker, Citation2014; Wylde, Citation2018).

Additionally, the political economy literature on the Latin American pink tide – the turn to the left that took place from the late 1990s to mid-2010s – lacks a systematic assessment of the effects of post-neoliberal governments on the degree of capital account openness across the region. For instance, scholars like Levitsky and Roberts (Citation2011), Flores-Macias (Citation2012), Yates and Bakker (Citation2014), Campello (Citation2015), and Wylde (Citation2018) make only anecdotal references to some countries’ capital controls without investigating them deeply. As the pink tide was a reaction to the negative consequences of neoliberalism, the rise of post-neoliberal parties could have led to one out of two opposite capital account policies: either the new governments could reregulate capital movements by deploying further controls, or they could keep the inherited levels of capital account openness in face of the costs of attempting to restrict cross-border financial flows.

Against this background, this article evaluates the impact of post-neoliberal parties on the level of capital controls in Latin American countries by estimating a time-series cross-section model for the period from 1995 to 2017. Besides this main empirical contribution, I also formulate a new version of the Capital Controls Index, proposed by Fernandez et al. (Citation2016).

Building upon the literature on post-neoliberalism, I argue that Latin American post-neoliberal governments tended to increase the level of capital controls instead of merely adapting to the constraints imposed by financial globalization. Specifically, I contend that the reregulation of cross-border financial flows was part of an effort to obtain further macroeconomic policy autonomy and attend to the interests of constituencies. In some countries, the deployment of capital controls also served to give concreteness to the rhetoric against financial and foreign interests. As these conditions are specific to post-neoliberal parties, there are no reasons to expect that other left-of-center administrations would reduce the degree of capital account openness.

The motivation for this research stems from Wylde (Citation2014), who stated that it is not possible to understand the full nature of Latin American post-neoliberal project without analyzing how national policies intersect with global capital. Regarding the implications for the international debate, this article illustrates the conclusion of Crotty and Epstein (Citation1996), according to whom the primary impediments to the deployment of capital controls are political instead of technicalFootnote2. In this sense, this study contributes by showing that political parties kept their relevance even in a context of growing capital mobility, and that left-of-center parties are not homogeneous on this policy issue.

Besides this introduction, the remainder of this article is organized as follows. The second section presents a literature review on the determinants of capital account regulation, highlighting studies centered on Latin America. The third section introduces the literature about Latin American post-neoliberalism as a means to build the theoretical framework underlying the article. The fourth section discusses the measurement of the level of capital controls, proposing a reformulation of the Capital Controls Index. The fifth section evaluates the effect of post-neoliberalism on the level of controls through time-series cross-section econometrics. Finally, the sixth section summarizes the main findings of the article.

Literature review

Capital mobility can be defined as the ability of investors to move capital flows across national boundaries (Clark et al., Citation2012). Such ability is a function of the restrictions imposed by states in form of laws and norms, the so-called capital controls (Obstfeld & Taylor, Citation2004; Epstein et al. Citation2005).

In this literature review, I opt to organize the determinants of capital mobility into five groups of explanatory variables: institutions, interests, ideas, political parties, and economic conjuncture. For each type of determinant, I highlight publications that make references to capital account regulation in Latin America.

Regarding the institutions, for instance, different authors conclude that autocratic political regimes tend to impose higher levels of capital controls due to three main reasons (Eichengreen & Leblang, Citation2008; Haggard & Maxfield, Citation1993; Milner & Mukherjee, Citation2009; Steinberg et al., Citation2018). First, the liberalization of capital outflows would concede an ability of exit to domestic private capitalists, weakening authoritarian regimes (Dailami, Citation2000; Hirschman, Citation2013). Second, the inflow of foreign capital may alter the economic structure, reducing the dependence of the most competitive sectors on government support (Pepinsky, Citation2008; Rajan & Zingales, Citation1998). Finally, since they do not suffer from international stigmatization in other spheres, democratic political regimes have additional incentives to avoid the stigma of restricting capital mobility within the international community (Chwieroth, Citation2015; Mosley, Citation2010).

In the case of Latin America, however, Macdonald (Citation2018) associates the capacity of implementing neoliberal reforms like the removal of capital controls with incomplete democratization. In line with O’Donnell’s (Citation1994) definition of delegative democracy, this conclusion stems from the various mechanisms adopted to shield democratic governments from societal pressures throughout economic liberalization. These mechanisms went from the insulation of policy experts to the repression of anti-neoliberal social movements (Weyland, Citation1996, Citation2003; De La Torre, Citation2014).

Besides political institutions, the provision of public goods and social protection by the government may also favor financial liberalization through the mitigation of its risks. According to the so-called compensation hypothesis, countries with higher public expenditure are more willing to remove capital controls (Rodrik, Citation1998; Burgoon et al., Citation2012). Considering the case of Latin American countries, Brooks (Citation2004) associates the underdevelopment of social protection with the difficulties to complete capital account liberalization in the region.

Moving to the role of interests, according to Li and Smith (Citation2003), the level of capital controls can be an outcome of the balance of power among competing socioeconomic interest groups. In this framework, the ability of interest groups to influence the level of capital controls is a function of their importance in the national economy as well as their access to policymakers.

To map sectoral preferences on capital mobility, it is possible to rely on the contribution of Frieden (Citation2015) and Walter (Citation2008, Citation2013) on the politics of the exchange rate. Such connection is straightforward since cross-border financial flows affect both level and stability of the exchange rate (Blanchard, Citation2017; Davidson, Citation2002; Rodrik & Subramanian, Citation2009).

Based on this approach, tradable producers like manufacturing industries are expected to support capital controls to keep a competitive and stable exchange rate (Blanchard, Citation2017; Gallagher, Citation2015a, Citation2015b; Rodrik & Subramanian, Citation2009; Thirlwall, Citation2002). In this regard, Frieden (Citation2015) makes reference to the recurrent lobby of Latin American manufacturing producers for an undervalued currency, especially after the removal of trade barriers.

Domestic manufacturing industry can also take an intermediate position in face of the benefits of foreign direct investment (FDI), controlling the timing and the degree of liberalization (Encarnation & Mason, Citation1990). According to Brooks and Kurtz (Citation2008, Citation2012), such trade-off between exchange rate competitiveness and access to foreign investments helps to explain, for example, why internationally oriented manufacturing sector advocated for partial capital account liberalization in the most industrialized Latin American economies. In this regard, Steinberg (Citation2016) finds that State-owned banks contribute to manufacturing industry choose currency undervaluation instead of cheap foreign credit, which may have implications for capital controls.

This attitude of manufacturing industries towards capital account openness in Latin America may also reflect the legacy of impost-substitution industrialization. In this sense, Etchemendy (Citation2011) argues that business groups with higher economic and organizational power demanded compensation or protection to support economic liberalization, leading to hybrid arrangements in several Latin American countries. According to Oliveira (Citation2019), after the rise of post-neoliberal left-wing governments in the early 2000s, manufacturing firms went even further by supporting restrictive measures towards the financial sector.

Despite being more favorable to capital account openness than manufacturing industries, domestic private banks also have a dual position, accepting the full mobility of short-term financial flows, but demanding protection against foreign banks competition in the domestic market (Haggard & Maxfield, Citation1996; Mosley, Citation2010; Pepinsky, Citation2008, Citation2013). In line with this argument, Latin American private banks contributed to partial capital account liberalization, seeking government protection against the entrance of foreign competitors (Brooks, Citation2004; Etchemendy & Puente, Citation2017).

The support for an open capital account tends to be stronger among firms that rely on an overvalued currency to accumulate foreign currency-denominated debts (Henning, Citation1994; Broz et al., Citation2008). Due to its positive impact on purchasing power, the nexus between capital inflows and strong currency may even win the support from workers and middle classes to capital account liberalization, especially in countries with a high inflation record as observed in Latin America (McCarty, Poole & Rosenthal, Citation2013; Gallagher, Citation2015a, Citation2015b; Frieden, Citation2015).

It is also possible to assess the relationship between interests and capital account policies from a historical materialist perspective. For instance, Soederberg (Citation2002) contends that capital controls may serve to enable specific forms of capital accumulation by conciliating the needs of different capitalist factions. In a similar vein, Alami (Citation2019) sheds light on the role of capital controls in the redistribution of the surplus between different sectors and the management of capital-labor antagonism.

Besides institutions and interests, there are studies centered on the role of ideas in the formulation of capital account policies. For example, since the dismantlement of the Bretton Woods order, neoclassical economics became the dominant paradigm among policymakers, supporting several market reforms. Thus, the participation of neoclassical economists in the government staff can help to explain capital account liberalization (Chwieroth, Citation2007a, Citation2007b). Conversely, the prevalence of economists aligned with heterodox theories such as Post-Keynesian economics and Latin American structuralism favors the deployment of capital controls (Gallagher, Citation2015a, Citation2015b).

Recently, the 2007 Global Financial Crisis also changed the international ideational setting around capital account policies (Grabel, Citation2017). For instance, mainstream economists aligned with the so-called new welfare economics admitted that cross-border financial restrictions may generate positive effects by correcting market failures like information asymmetries and pecuniary externalities (Korinek, Citation2011). In face of this ideational change and the pressure from emerging economies’ policymakers, even the IMF updated its institutional view and officially recommended capital controls, renamed as capital flows management measures, as a last resort and temporary option to deal with massive inflows (Ostry et al., Citation2010; IMF, Citation2012).

Being pivotal to translate ideas and preferences into policies, political parties shape different macroeconomic policies, affecting economic outcomes. In this regard, the classical partisan approach argues that right-wing and left-wing parties tend to adopt opposite economic policies, being the latter ones more inclined to expansionary and interventionist policies (Hibbs, Citation1977). After the dismantlement of the Bretton Woods order, however, the capital mobility hypothesis predicted gradual erosion of these differences due to the growing pressures of the global financial markets (Andrews, Citation1994; Keohane & Milner, Citation1996).

Given this new context, some authors adapted the classical partisan approach, adding conditions to the maintenance of the differences between left-wing and right-wing parties. Garrett (Citation1995, Citation2000), for example, concludes that government partisanship still matters for fiscal and monetary policies in countries with strong labor unions and corporatist institutions.

This literature has also adopted distinct perspectives on the relationship between partisanship and capital mobility. Closer to the classical approach, Bearce (Citation2002, Citation2003) argues that left-of-center parties are still more willing to impose capital controls to attend to the interests of specific economic sectors. Similarly, Kastner and Rector (Citation2003, Citation2005) observe that government partisanship may shape capital account policies, but this impact is mediated by the international context, being stronger for right-wing parties committed to liberalization. On the other hand, Alfaro (Citation2004) and Quinn and Inclán (Citation1997) conclude that partisanship is relevant, but left-of-center policies depend on the endowments of each country.

In the case of Latin America, Kingstone and Young (Citation2009) did not find any evidence that left-of-center parties had reverted market reforms, however, their sample years go from 1975 to 2003, overlooking most of the so-called pink tide period. In this regard, Yates and Bakker (Citation2014) contend that post-neoliberal parties, which went to power during the pink tide, shared the option for expansionary policies despite their ideational and organizational differences. In contrast, Strange (Citation2014) and Stallings and Peres (Citation2011) observe that these governments adopted an intermediate strategy, aiming to regulate speculative financial flows as a means to safeguard financial and exchange rate stability.

The capacity of left-of-center parties to diverge from orthodox macroeconomic policies may also stem from intervening variables. Relying on this notion, Levitsky and Roberts (Citation2011), Flores-Macias (Citation2012), and Etchemendy and Puente (Citation2017) argue that the degree of economic interventionism depends on the organizational features of the left-of-center party, the institutionalization of party system, and the occurrence and deepness of currency crises.

In comparison to these scholars, Campello (Citation2015) gives more relevance for capital controls, although this does not save these regulations from occupying a switching position in her theoretical framework. For instance, in the theory building, the lack of cross-border financial restrictions is taken as uniform for all cases, functioning as an antecedent variable. In other moments, as in the case of Argentina, the different capital account policies seem to be an independent variable, helping to explain why countries pursued divergent economic policies. Finally, in the case of Venezuela, the author takes the level of capital controls as a dependent variable, which responds to the interaction between the global economic cycle and the government partisanship.

Besides these approaches, it is possible to explain the evolution of the level of capital controls as a reaction to economic conjuncture. Regarding the impact of crises, Agnello et al. (Citation2015) find that inflation and banking crises are the key drivers of capital account liberalization, while Leblang (Citation1997), Pepinsky (Citation2012) and Young and Park (Citation2013) conclude that currency crises favor the adoption of financial restrictions like capital controls.

Specifically about the case of Latin American countries, Frieden (Citation2015) associates the resilience of inflationary pressures with the need for attracting capital inflows through liberalizing reforms, while Edwards (Citation2008, Citation2010) points out that recurrent external crises have been inversely related to the degree of economic openness across the region.

Still regarding the role of conjunctural factors, Remmer (Citation2012) contends that the mid-2000s commodity boom was responsible for allowing Latin American countries to pursue statist, nationalist, and redistributive political projects. Besides creating further policy space, the commodity boom may also have increased the support for capital controls due to its impact on the level and stability of exchange rates (Gallagher & Prates, Citation2016). More skeptical, Kaltenbrunner (Citation2016) characterizes the recent deployment of capital controls by emerging and developing countries as a temporary response in face of strong capital inflows and the exhaustion of the conventional framework.

Before moving to the next section, it is important to highlight which aspects are missing in the reviewed literature. As mentioned in the introduction, this article focuses on the case of Latin American countries, therefore, the literature gaps and the aimed contributions are discussed from this perspective.

First of all, there is no systematic assessment of the impact of left-of-center governments on the level of capital controls in Latin America, especially in the case of post-neoliberal administrations, which followed the pink tide. Such gap is not addressed by the existent studies as they discuss macroeconomic policies as a whole, demanding the formulation of statistical analyses to disentangle the drivers of cross-border financial regulation across the region.

In terms of theory building, the literature does not explore the relationship between chosen capital account policies and specific left-of-center political-ideological projects such as post-neoliberalism and Third Way. Similarly, there is also some confusion between party ideology and policy framing, especially in the countries where post-neoliberal administrations resorted to quiet politics as a means to mitigate the opposition to the deployment of capital controls. In this regard, I contend that both moderate and radical currents of Latin American post-neoliberalism may be equally committed to the reregulation of capital flows.

In the next section, my main objective is to hypothesize the impact of post-neoliberal governments on capital account policies. This goal demands to contextualize the rise of post-neoliberal parties as well as their objectives and ideological foundations. Additionally, it is also important to contrast post-neoliberalism with other left-of-center projects in Latin America.

Theoretical framework

According to Ban (Citation2016), neoliberalism can be defined as a set of ideas and policies that aim to expand the market realm by dismantling institutional arrangements that restrict its self-regulatory mechanismFootnote3. This policy regime first arrived in Latin America under the military dictatorships of Chile and Argentina in the 1970s, becoming dominant in the 1990s (Macdonald & Ruckert, Citation2009; Sankey & Munck, Citation2016). In this context, even some left-of-center political parties – especially the ones affiliated to the Socialist International (SI), which embraced the Third Way agenda – adhered to economic liberalization and macroeconomic orthodoxy (Kirby, Citation2003; Sandbrook et al., Citation2007; Vasconi et al., Citation1993).

In terms of financial policies, as expected, the rise of neoliberalism led to the removal of most capital controls, the liberalization of interest rates, the retrenchment of directed credit supply, and the dismantlement of prudential regulations (Frenkel & Simpson, Citation2003; Aizenman, Citation2005; Ocampo & Bertola, Citation2012). This impulse for financial liberalization aimed to attract foreign credit and equalize domestic interest rates as a means to boost private investment and, consequently, economic growth (Edwards, Citation1999; Henry, Citation2007; McKinnon, Citation1973; Shaw, Citation1973).

The assessment of this extensive policy reform shows a clearly negative balance. After favoring the attraction of massive capital inflows in the early 1990s, the abrupt removal of capital controls forged a debt-led growth pattern in Latin American countries (Onis, Citation2006; Petras & Veltmeyer, Citation2009). During the late 1990s and early 2000s, the increased financial fragility led to successive currency crises across the region (Edwards Citation2010, Tude & Milani, Citation2015).

In general, the outcomes of market reforms were at best mixed. Even though it is possible to associate economic restructuring with inflation control and improved access to new technologies (Gwynne & Kay, Citation1999; Oxhorn, Citation2009), neoliberalism failed to achieve sustained growth, fostering the growth of inequality, unemployment, and poverty (Grugel & Riggirozzi, Citation2012; Macdonald, Citation2018).

These harmful effects of neoliberalism fueled popular discontentment, strengthening the left-of-center political parties that opposed market reforms (Grugel & Riggirozzi, Citation2018; Oxhorn, Citation2009; Weyland, Citation2010). The supporters of these organizations were not only labor unions, which were negatively affected by economic liberalization and macroeconomic orthodoxy, but also new civil society actors such as neighborhood organizations, landless peasants, unemployed workers, and feminist and environmentalist organizations (Roberts, Citation2008; Macdonald & Ruckert, Citation2009; Macdonald, Citation2018). In most of the countries, it was even possible to attract new constituencies by building what Saad-Filho (Citation2007) defined as the losers’ alliance, composed of unionized workers, domestic manufacturing producers, unorganized and unskilled workers, and even some rural producers.

The opposition to neoliberalism and the need for appealing to broader social groups contributed to forging a new dominant political-ideological project within the Latin American left, known as post-neoliberalism. As suggested by Wylde (2018), these constitutive aspects implied that post-neoliberal parties rejected excessive marketization, but abandoned anti-capitalism, becoming less hostile towards market economy and liberal democracy (Lomnitz, Citation2006).

It is important to note, however, that post-neoliberalism did not break with distinctive ideological foundations of the Latin American left. For instance, post-neoliberal parties kept the historical leftist commitment to economic nationalism, especially in face of the US influence across the region (Remmer, Citation2012). Similarly, aspects like democratic fragility, extreme inequality, and heterogeneous class structures favor the prevalence of populism among these parties (Oxhorn, Citation1998). In this sense, scholars like Mudde and Kaltwasser (Citation2013) and De La Torre (Citation2014) classify numerous Latin American post-neoliberal organizations as inclusionary populists due to their focus on the opposition between the virtuous people, composed by different excluded social groups, and the local elites, taken as allies of imperialism.

In general, post-neoliberal parties share the aim to resubordinate the economy to society through the reinforcement of state functions (Macdonald & Ruckert, Citation2009; Sankey & Munck, Citation2016, Pickup, Citation2019). Specifically, it is possible to define post-neoliberalism as a political-ideological project that seeks to redirect market economies towards social concerns and revive citizenship through a new politics of participation and sociocultural alliances (Grugel & Riggirozzi, Citation2012; Yates & Bakker, Citation2014).

The convergence in the struggle against imperialism and neoliberalism also motivated the regional exchange between post-neoliberal parties. This cooperation gained momentum when the Workers’ Party (Brazil) proposed a joint conference in July 1990 (FSP, Citation1990). This space of political debate, institutionalized as São Paulo Forum (Foro de São Paulo – FSP) in 1991, gathered organizations from different ideological backgrounds, including communist, socialist, social-democratic, and national-popular ones (FSP, Citation1991; French, Citation2009). Despite this political diversity, most of the FSP members are not affiliated with the SI, which includes parties that supported or even implemented neoliberal policies (Kirby, Citation2003; Vasconi et al., Citation1993).

As previously mentioned, the context of social polarization and financial instability strengthened the organizations that opposed market reforms, boosting the performance of FSP parties and culminating in several electoral victories across the region (Roberts, Citation2008; Levitsky & Roberts, Citation2011; Cantamutto, Citation2016). As shown by , this turn to the left covered most of Latin American countries after beginning in 1998, when Hugo Chavez won the presidential election in Venezuela (Silva, Citation2009; Munck, Citation2015; Larrbure, Citation2019).

Table 1. Governments led by members of the São Paulo Forum – 1995–2017.

At the level of public policies, these governments substantially varied due to the economic and political specificities of each country (Beasley-Murray et al., Citation2009; Weyland, Citation2010; Levitsky & Roberts, Citation2011; Flores-Macias, Citation2012; Friedmann & Puty, Citation2020). Nevertheless, a list of recurrent post-neoliberal measures includes the expansion of social protection and redistributive policies, the return of industrial policies, the strengthening of participatory democracy, and the emphasis on recognition and identity politics (Grugel & Riggirozzi, Citation2012, Citation2018; Wylde, Citation2018; Macdonald & Ruckert, Citation2009). In some cases, post-neoliberalism also meant the nationalization of strategic companies and natural resources (Yates & Bakker, Citation2014; Singh, Citation2014).

Even though these initiatives signified a departure from the policies adopted during the 1980s and early 1990s, the administrations led by post-neoliberal parties did not overcome many of the inherited neoliberal practices, which were kept or at most amended to avoid conflicts with domestic elites and international markets (Tussie, Citation2009; Yates & Bakker, Citation2014; Chodor, Citation2015). In terms of economic policies, for example, the most important continuities lied in the macroeconomic regime, which kept the commitment to inflation control, fiscal balance, and trade liberalization (Panizza, Citation2005; Hunter, Citation2007; Pickup, Citation2019).

Considering the aforementioned features of post-neoliberalism, it is worth distinguishing between two different uses for this concept. The first one stems from the debate about the possibility of a global demise of neoliberalism after the eruption of the Global Financial Crisis and was criticized for underestimating the adaptative capacity of this regime of socioeconomic governance (Peck, Theodore & Brenner, Citation2010). The second use, followed in this paper, refers specifically to the political-ideological project that became prevalent in the Latin American left since the 1990s (Yates & Bakker Citation2014). As the global resilience of neoliberal practices and the collapse of Latin American pink tide indicate (Fine & Saad-Filho, Citation2017; Grugel & Riggirozzi, Citation2018), the criticisms towards the notion of a global or even a regional post-neoliberal moment proved valid, however, this does not change the adherence of FSP members to the post-neoliberal project, justifying, therefore, the characterization of these organizations as post-neoliberal parties in the scope of this article.

In this regard, it is also important to clarify the difference between post-neoliberal parties – members of the São Paulo Forum – and left-of-center parties that embraced neoliberal policies – most of them affiliated to the Socialist International. The former preserved part of inherited market reforms as a means to build enough support for a transformative agenda (Grugel & Riggirozzi, Citation2012; Wylde, Citation2018), while the latter adopted and sometimes fostered core neoliberal practices such as the privatization of State-owned companies, the pursuit of fiscal austerity, and the impulse for trade openness (Kirby, Citation2003; Sandbrook et al., Citation2007).

As previously mentioned, this article aims to investigate to what extent post-neoliberal governments have reshaped capital account policies towards the reregulation of cross-border financial flows. Building upon the discussion presented in this section, I expect that post-neoliberal parties will increase the level of capital controls after coming to the executive power.

In light of the literature on Latin American post-neoliberalism, this main hypothesis stems from three mechanisms whose presence and relevance vary from country to country. Regarding the conduct of macroeconomic policies, for instance, the pursuit of post-neoliberal goals demands further degrees of freedom than the adherence to neoliberal practices (Wylde, Citation2018). This additional need for autonomy stems from policies such as the expansion of social protection, the increase of the wage share, the incentive for reindustrialization, and the promotion of participatory democracy, which tend to be associated with expansionary policies at credit supply, public expenditure, and management of interest rates (Yates & Bakker, Citation2014). In this regard, the adoption of capital controls seeks to combine this policy orientation with the exchange rate management and the prevention of financial markets’ threats against deviant policies.

It is important to note that this rationale applies to both inflows and outflows controls. The former restrictions seek to safeguard exchange rate stability, while the latter regulations aim to avoid currency crises and redirect investments into the domestic economy (Kregel, Citation2004; Bresser-Pereira et al., Citation2015; Gallagher Citation2015a, Citation2015b).

In addition to the increase of policy autonomy, post-neoliberal governments may also deploy capital controls because of their distributive effects. Specifically, the reregulation of capital flows may seek to achieve and maintain a competitive exchange rate to attend to the interests of the manufacturing sector (Alami, Citation2019; Frieden, Citation2015; Soederberg, Citation2002; Walter, Citation2008, Citation2013). As previously discussed, one of the features of post-neoliberalism is the building of broad and heterogenous socioeconomic alliances (Grugel & Riggirozzi, Citation2012; Saad-Filho, Citation2007). In this sense, attracting the support of elite allies like manufacturing producers is key for the political sustainability of the post-neoliberal project. The interests of this sector gain further importance in face of the nexus between deindustrialization and weakening of labor unions (Anner, Citation2008), which tend to be core supporters of post-neoliberal parties (Roberts, Citation2008; Weyland, Citation2010).

Besides the instrumental relationship with policy reorientation, depending on the context, the deployment of further capital controls may also serve to political mobilization. In line with the ideas of economic nationalism and inclusionary populism, post-neoliberal governments may use capital account policies as a means to show commitment to the fight against neoliberalism, imperialism, and financial interestsFootnote4.

As these mechanisms are specific to post-neoliberal administrations, other left-of-center parties may not have reasons for increasing the level of capital controls. In other words, as governments aligned with the Third Way agenda have not committed to economic nationalism and reindustrialization nor demanded further macroeconomic policy autonomy, they do not seem to have incentives to restrict capital movements.

Still regarding the main hypothesis of this article, I do not contend that the rise of post-neoliberal parties to power was the sole cause for the reregulation of capital flows in Latin America. As discussed in the literature review, different variables may affect the level of capital controls. For example, the pink tide period coincided with changes in the international context – such as the 2000s commodity boom, the inflows surge following the Global Financial Crisis, and the revision of the IMF view on capital flows management – that tended to favor the deployment of further capital controls. Therefore, my argument here is that government partisanship remains a key determinant of capital account policies even after accounting for the impact of other explanatory factors.

In a similar vein, some factors may counteract the expected relationship between post-neoliberalism and capital controls. For instance, as mentioned in the literature review, an overvalued currency, caused, for example, by an inflows surge, has a positive impact on consumers’ purchasing power (Frieden, Citation2015; McCarty, Poole & Rosenthal, Citation2013). In this context, a progressive administration like a post-neoliberal one may refrain from imposing capital controls due to its redistributive aims (Gallagher, Citation2015a, Citation2015b).

Moreover, as discussed in this section, the post-neoliberal turn did not mean a complete rupture with previous market reforms, which sometimes include the decision to safeguard the inherited degree of financial openness (Chodor, Citation2015; Macdonald & Ruckert, Citation2009; Panizza, Citation2005; Hunter, Citation2007; Pickup, Citation2019). This strategy may change throughout time as post-neoliberal parties accumulate electoral victories and, consequently, become more able to implement their ideas.

Finally, the commitment to an open capital account may also stem from the bargaining power of specific economic sectors such as the financial system (Henning, Citation1994; Brooks & Kurtz, Citation2008, Citation2012; Broz et al., Citation2008). Therefore, it makes sense to expect that post-neoliberal parties will face further difficulties to reregulate capital flows in countries with larger financial sectors.

Measuring the level of capital controls: towards a new indicator

This section discusses the alternative strategies for measuring the level of capital controls or financial openness to build time-series cross-section datasetsFootnote5. In the empirical literature, this assessment uses to rely on the IMF Annual Report on Exchange Arrangements and Exchange Restrictions (IMF-AREAER). This publication provides comprehensive descriptions of the foreign exchange arrangements and capital controls of all IMF member countries, being the basic source of information for the indicators proposed by Grilli and Milesi-Ferretti (Citation1995), Quinn (Citation1997), Chinn and Ito (Citation2006, Citation2008), and Fernandez et al. (Citation2016).

Among these measures, the so-called KAOPEN, formulated by Chinn and Ito (Citation2006, Citation2008), has been the most recurrent in the empirical literature. In terms of construction, KAOPEN is the first standardized principal component of four variables, which indicate the presence of multiple exchange rates, the existence of restrictions on current account transactions, the share of a five-year window of restrictions on capital account transactions (encompassing year t and the preceding four years), and the requirement of export surrender proceeds.

The main contribution of the Chinn-Ito index lies in its coverage, which includes data for 181 countries for the 1970-2017 period. However, KAOPEN also presents two setbacks. The most important one stems from how Chinn and Ito (Citation2006, Citation2008) incorporate capital account restrictions into their final measure. As observed by Karcher and Steinberg (Citation2013), by introducing systematic measurement errors, the use of a five-year average in the assessment of capital account policies increases the risk of false positives and reverse causality as well as contributes to underestimating the impact of political variables like government partisanship on the level of capital controls.

Another shortcoming of KAOPEN arises from relying on the existence of other restrictions on international transactions to assess the intensity of capital controls. If, on one hand, it makes sense to expect that strict capital account regulations correlate with other restrictions; on the other hand, this strategy introduces the risk of conflating trade and capital account policies as well as underestimating the level of capital controls in countries with high levels of trade openness.

Against this background, the Capital Controls Index (CCI), proposed by Fernandez et al. (Citation2016), emerges as an alternative. This measure assesses the annual level of capital controls by taking the average degree of restrictions over ten types of cross-border financial inflows and outflowsFootnote6 for 100 countries for the 1995-2017 periodFootnote7. For each kind of flow, the authors aggregate binary variables that show the existence or not of restrictions over different subcategoriesFootnote8. This procedure results in a continuous value between 0 and 1, where 1 is the value obtained by countries that control all subcategories in all types of flows.

In contrast with the strategy followed by Chinn and Ito (Citation2006, Citation2008), Fernandez et al. (Citation2016) contend that the CCI captures the intensity of capital controls by tracking variations across asset categories, directions of transactions, and time. Underlying this approach, there is an assumption that the intensity of controls is correlated with how many types of capital movements are targeted by restrictions. Therefore, one of the advantages of CCI is the capacity of assessing the intensity of controls based only on capital account policies, avoiding the risks associated with the incorporation of restrictions on other international transactions.

The main setback of CCI lies in the use of simple average for measuring the annual level of capital controls in each country. Such approach overlooks the sixth and latest edition of the Balance of Payments and International Investment Position Manual, published by the IMF (Citation2009), which classifies capital flows into four functional categories: direct investments, portfolio investments, derivatives, and other investmentsFootnote9. As six out of ten types of flows considered by Fernandez et al. (Citation2016) can be characterized as other investments, there is a risk that relevant flows like direct and portfolio investments are underestimated.

In face of these aspects, I opted to reformulate the Capital Controls Index with aim of attributing the same weight to each one of the four IMF functional categories. Therefore, relying on data provided by Fernandez et al. (Citation2016), the new CCI is the first standardized principal component of the level of capital controls over direct investments, portfolio investments, derivatives, and other investments (see the appendix). As the original CCI, this index takes higher values the more closed the country is to capital flows.

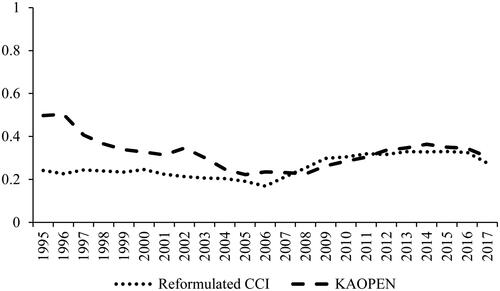

Based on the reformulated CCI, it is possible to plot the evolution of the level of capital controls in Latin America from 1995 to 2017, which can be divided into three sub-periods (see ). Between the late 1990s and the mid-2000s, there was a trend in favor of capital account liberalization. After the crisis, the reregulation of cross-border financial flows gained momentum until the mid-2010s, when the impulse for capital controls faded away, coinciding with the ebb of pink tide. As also shown in , the same periodization emerges from the analysis of KAOPENFootnote10. However, this measure lags behind in detecting the lower level of controls in the late 1990s as well as the reregulation of capital flows in the late 2000s. One explanation for this delay lies in the composition of KAOPEN, which includes a five-year average to assess capital account policies and restrictions on other international transactions.

Figure 1. Normalized level of capital controls – Latin America – unweighted country shares – 1995–2017.

Source: the author based on Fernandez et al. (Citation2016); Chinn and Ito (Citation2006, Citation2008).

Post-neoliberalism and capital controls in Latin America: empirical analysis

According to my argument, developed in the theoretical framework, Latin American post-neoliberalism should induce the reregulation of cross-border financial flows as a response to its macroeconomic agenda, distributive objectives, and ideational underpinnings. As discussed in the literature review, little systematic empirical work exists on this topic. I test my argument while also trying to control for the leading contending propositions, centered on political institutions, economic sectors, and conjunctural pressures. My data set is a time-series cross-section (TSCS) one, containing 17 Latin American countries from 1995 to 2017. Ceteris paribus, my hypothesis is that countries led by post-neoliberal parties should have a higher level of capital controls.

My central independent variable is the government partisanship in a country at time t. This variable reflects the adherence of the ruling political party in the executive power to post-neoliberalism. Specifically, I built a binary variable, where countries are coded as post-neoliberal at time t if the ruling party is a member of the São Paulo ForumFootnote11 (FSP = 1).

To increase the robustness of the analysis, I also estimate the model using other measures of government partisanship as the main independent variable. In this regard, I considered the accumulated number of years of post-neoliberal government in a country at time t (AFSP) to assess to what extent the duration of post-neoliberal experience shapes its impact.

Additionally, I built a binary variable for governments led by parties affiliated to the Socialist International (SI = 1). This exercise aims to check if all left-of-center parties pursue similar capital account policies. As discussed in the theoretical framework, unlike post-neoliberal administrations, I do not expect that governments led by SI members will be willing to deploy further capital controls.

My dependent variable is the level of capital controls in a country at time t. As discussed in the previous section, I reformulated the Capital Controls Index (CCI), proposed by Fernandez et al. (Citation2016).

Changes in capital account regulation may also arise because of factors other than government partisanship. In this sense, based on the literature review, I added control variables to the baseline model (see ).

Table 2. Descriptive statistics.

To capture the impact of political institutions, I included the level of democracy (DEM), which tends to be positively correlated with capital account openness. As usual in the literature, this measure comes from Polity IV.

According to the pluralist literature, each industry has different preferences regarding the conduct of capital account policies, gaining influence in function of its economic size. In this regard, I added the domestic credit to private sector as percentage of GDP (CRED), provided by the World Bank, as a means to assess the relevance of the financial sector, which tends to be correlated with the progress of capital account liberalization.

Moreover, I included the sophistication of a country’s productive structure as provided by Hidalgo and Hausmann’s (Citation2009) Economic Complexity Index (ECI). As discussed in the literature review, the effect of more sophisticated industrial structures is uncertain since manufacturing producers must balance their need for foreign credit with their demand for a stable and competitive exchange rate.

Another set of determinants of capital account regulation stems from the economic conjuncture. In this regard, based on data provided by the Bank of International Settlements, I considered the occurrence of currency crises as measured by Reinhart and Rogoff (Citation2009), who define this type of crisis as an annual depreciation of national currency versus US dollar of 15 percent or more (CCRISIS = 1). Additionally, relying on IMF databases, I incorporated an index of commodity terms of trade (TT) as well as capital inflows as percentage of GDP (INFLOWS).

Finally, since the structural features of each country may also shape the cross-border financial regulation, I included the real GDP per capita (GDPPC), the size of government expenditure as percentage of GDP (GOVEXP), and the level of trade openness (TO), measured by trade as share of GDP. All these variables come from the Penn World Table database.

The basic equation estimating the relationship between government partisanship and capital account openness is:

TSCS data have numerous problems that violate the standard assumptions necessary for ordinary least squares (OLS) to be unbiased and efficient. For instance, to mitigate problems caused by heteroskedasticity, I used panel-corrected standard errors (PCSE) as suggested by Beck and Katz (Citation1995). Similarly, I included country and year fixed effects to deal with problems of omitted variable bias. Moreover, I addressed problems of serial correlation by using an AR (1) correction.

Moving to the analysis of the results, I first tested my central independent variable without any control variable. As shown by , model 1 indicates that post-neoliberal governments are positively correlated with the level of capital controls. This finding corroborates my hypothesis, which contends that post-neoliberal parties tend to reregulate capital flows as a means to obtain further macroeconomic autonomy, favor their constituencies, and show commitment to national and popular interests.

Table 3. Baseline model.

This relationship between government partisanship and cross-border financial regulation stands after including the control variables (see model 2). In this regard, a larger size of capital inflows is associated with increased levels of capital controls, which can be part of an attempt to gain policy space amid financial booms.

On the other hand, the level of democracy presents a significant liberalizing impact on capital account policies. As discussed in the literature review, it is important to note that this result may also stem from the relationship between incomplete democratization and economic liberalization in Latin America.

Moving to the robustness checksFootnote12, I included interaction variables between post-neoliberal governments and economic interests to assess what factors may counteract the reregulation of capital flows (see ). As expected, stronger financial sectors contribute to mitigating the impact of post-neoliberal governments on capital account policies.

Table 4. Model with the interaction between post-neoliberal governments and economic interests.

For instance, the maximum capacity of post-neoliberalism to deploy further capital controls would be observed in the absence of a financial sector in the country. After that, larger financial sectors seem to discourage the reregulation of cross-border financial flows by post-neoliberal governments (see model 3). As discussed in the literature review, this finding may stem from the interest of banks in accessing external sources of credit and safeguarding capital mobility.

In the case of the productive structure, potentially reflecting the contradictory interests within higher-value-added industries, the interaction variable is not statistically significant. However, after its inclusion in the model, the negative correlation of economic complexity and capital controls increases its significance (see model 4).

As previously mentioned, I also conducted robustness checks based on different main explanatory variables. For instance, I replaced the government partisanship with the duration of post-neoliberal administrations (see ). Despite the increased statistical significance, the results are quite similar, indicating that longer post-neoliberal experiences contribute to reregulate capital flows (see models 5 and 6). This finding may reflect the fact that successive electoral victories strengthen the pursuit of a post-neoliberal policy reorientation. In line with this interpretation, the administrations led by FSP members in Argentina, Brazil, Bolivia, and Venezuela deployed stricter capital controls after the first term (Campello, Citation2015; Fritz & Prates, Citation2018; Naqvi, Citation2019; Wylde, Citation2016).

Table 5. Model with the duration of post-neoliberal governments.

Finally, I tested the impact of governments led by members of the Socialist International on the level of capital controls (see ). This exercise aimed to check if the reregulation of cross-border financial flows was a recurrent policy of any left-of-center government or a specific commitment of post-neoliberal parties. As expected, the results indicate that parties affiliated with the Socialist International do not tend to deploy further capital account restrictions. On the contrary, these governments are correlated with the removal of capital controls (see models 7 and 8). As previously discussed, this finding may stem from the fact that parties aligned with a Third Way agenda have little incentives to restrict capital mobility as they tend to embrace macroeconomic orthodoxy and refrain from committing to economic nationalism and reindustrialization.

Table 6. Model with governments led by members of the socialist international.

Final remarks

This article assessed the impact of post-neoliberalism on capital flows management in Latin America. Methodologically, I pursued this objective through the estimation of a time-series cross-section model that used data from 17 countries for the period between 1995 and 2017. In addition to this main contribution, I relied on principal component analysis to reformulate the Capital Controls Index, originally proposed by Fernandez et al. (Citation2016).

Building upon the political economy literature about the topic, I argued that post-neoliberal governments had three complementary reasons to reregulate capital flows. At the level of macroeconomic policies, the deployment of further capital controls was part of the effort to obtain further policy autonomy, which was a necessary condition for fostering economic growth and social inclusion as well as attending to the interests of constituencies like labor unions and manufacturing producers. Furthermore, in some countries, the adoption of capital account restrictions gave concreteness to the rhetoric against financial and foreign interests.

As expected, the results of the econometric estimation corroborated this theoretical argument. Specifically, contrary to other left-of-center administrations, post-neoliberal governments were found to have a positive impact on the level of capital controls in Latin American countries. Besides this main conclusion, observed in different variations of the baseline model, the empirical evidence also sheds light on the role of the financial sector as a factor that potentially counteracts the reregulation of capital flows during post-neoliberal administrations.

Concerning the international political economy literature, it is worth highlighting four contributions of this article. First of all, the aforementioned econometric results showed that the differences between political parties still matter for macroeconomy policymaking, providing additional support to the so-called partisan approach. Even though the deepness of these differences deserves further research, this conclusion gains relevance because it emerged from the analysis of cross-border financial regulation, which is one of the policies that globalization has most constrained.

Still regarding the relationship between government partisanship and economic policies, this article also sheds light on the pivotal role of the specific content of party ideologies. In this sense, a proper assessment of the impact of government partisanship requires ideological classifications that address the diversity within the left-of-center camp.

Moving beyond the theoretical debate, the empirical relevance of government partisanship for capital account policies in Latin America may have implications for the analysis of interventionist responses that followed the Global Financial Crisis. In the case of capital controls, for example, the crisis indeed favored the deployment of further restrictions, however, the national reactions to this opportunity also reflected the ideology of each country’s ruling party.

Finally, it is important to position this article in the current regional context. In this regard, even though post-neoliberal administrations did not break with capital mobility and inherited market reforms, their option for reregulating capital flows may explain the ebb of Latin American post-neoliberalism, which opened the way for the recent strengthening of right-wing political forces. In terms of historical lessons, the empirical findings of this article support another argument put forward by Crotty and Epstein (Citation1996), that is, any progressive economic restructuring, however moderate, demands at least the threat of deploying capital controls.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (204.2 KB)Acknowledgements

The author is grateful for the helpful comments provided by the anonymous referees, Andrew X. Li, Anil Duman, Cristina Corduneanu-Huci, Evelyne Hubscher, Julia Bandeira, Mark Hallerberg, and Martino Comelli on earlier drafts of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Data availability statement

The author confirms that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article or its supplementary materials.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Pedro Perfeito da Silva

Pedro Perfeito da Silva is a Ph.D. candidate in political science at the Central European University. His research interest mainly lies in international political economy, specifically, in the politics of external financial policies in emerging and developing countries after the dismantlement of the Bretton Woods order.

Notes

1 In this article, terms like capital controls, capital account policies, capital account regulation, cross-border financial regulation, and capital flows management techniques are used interchangeably.

2 The effectiveness of capital controls is not necessary to justify the study of this topic since this assessment is controversial, dynamic, and a function of political process. Even if we classify capital controls as ineffective, understanding the adoption of ineffective public policies is also a topic of interest of political science.

3 This policy-centered definition of neoliberalism differs from other conceptualization strategies. For instance, according to Fine and Saad-Filho (Citation2017), neoliberalism is not reducible to ideas or policies, rather they characterize it as a stage of capitalist development. Despite the advantages of this structural approach for understanding neoliberalism at the global level and across time, I argue that the narrow policy-centered approach is better suited for analyzing and classifying the policies adopted by individual governments.

4 In comparison with the macroeconomic and distributive mechanisms, this mobilizational channel seemed to be less prevalent across the region, remaining absent in the moderate cases of post-neoliberalism like Peru and Uruguay. However, in countries like Argentina and Ecuador, the deployment of capital controls used to follow confrontational rhetoric against financial interests and international organizations (Muños & Retamozo, Citation2008; Riggirozzi, Citation2009; Wolff, Citation2016). Even though refraining from heated rhetoric, the motivations for capital controls in Bolivia also included the need for addressing the anti-finance sentiment of core constituencies (Naqvi, Citation2019). Similarly, in the case of Brazil, Gallagher (Citation2015a, Citation2015b) mentioned that capital controls had some relevance in the electoral debate, resonating with the anti-imperialist sentiment of trade unionists and progressives.

5 To make comparisons easier, in this article, I take the level of controls as exactly the inverse of the degree of capital account openness.

6 The covered types of cross-border financial flows are: money market instruments; bonds or other debt securities with an original maturity of more than one year; equity, shares or other securities of a participating nature; collective investment securities; financial credits; derivatives; commercial credits; guarantees, sureties and financial back-up facilities; real estate transactions; and direct investments.

7 The shorter coverage of CCI is not a problem for the objectives of this article due to its focus on policy decisions that followed the complete dismantlement of the Bretton Woods order. In this regard, Kirshner (Citation2014) divides the Postwar period into three subperiods: (i) the Bretton Woods order (1947–1973); (ii) the transition period; and (iii) the Globalization project (after 1994).

8 For example, the level of capital controls over direct investments is the average of three binary variables, which indicate the existence of restrictions over direct investments’ inflows, outflows, and liquidations. Considering the ten types of capital flows, CCI covers 32 subcategories.

9 The fifth functional category refers to official reserve assets, which are not cross-border financial flows.

10 For purposes of comparison with the reformulated CCI, I converted KAOPEN to make larger values represent more restrictions on capital account transactions.

11 Since I rely on yearly data, I consider as ruling party the one that governed the country for the largest number of days in each year.

12 Considering that the control variables related to each country's structural features can lead to endogeneity issues, I re-estimated the models without them. Additionally, I repeated the empirical exercises with a different measure for the integration into international trade, the index of participation in the global value chains (GVC) as provided by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. As shown in the appendix, despite some variation in the level of significance of some variables, the conclusion about the impact of post-neoliberal administrations on the level of capital controls remains the same.

References

- Agnello, L., Castro, V., Jalles, J., & Sousa, R. (2015). What determines the likelihood of structural reforms? European Journal of Political Economy, 37, 129–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2014.10.007

- Aizenman, J. (2005). Financial liberalisations in Latin America in the 1990s: A reassessment. The World Economy, 28(7), 959–983. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2014.10.007

- Alami, I. (2019). Post-crisis capital controls in developing and emerging countries: Regaining policy space? An historical materialist engagement. Review of Radical Political Economics, 51(4), 629–649. https://doi.org/10.1177/0486613418806635

- Alfaro, L. (2004). Capital controls: A political economy approach. Review of International Economics, 12(4), 571–590. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9396.2004.00468.x

- Andrews, D. (1994). Capital mobility and state autonomy: toward a structural theory of international monetary relations. International Studies Quarterly, 38(2), 193–218. https://doi.org/10.2307/2600975

- Anner, M. (2008). Meeting the challenges of industrial restructuring: labor reform and enforcement in Latin America. Latin American Politics and Society, 50(02), 33–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-2456.2008.00012.x

- Ban, C. (2016). Ruling ideas how global neoliberalism goes local. Oxford University Press.

- Bearce, D. (2002). Monetary divergence: Domestic political institutions and the monetary autonomy-exchange rate stability trade-off. Comparative Political Studies, 35(2), 194–220. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414002035002003

- Bearce, D. (2003). Societal preferences, partisan agents, and monetary policy outcomes. International Organization, 57(2), 373–410. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818303572058

- Beasley-Murray, J., Cameron, M., & Hershberg, E. (2009). Latin America's left turns: An introduction. Third World Quarterly, 30(2), 319–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436590902770322

- Beck, N., & Katz, J. (1995). What to do (and not to do) with time-series cross-section data. American Political Science Review, 89(3), 634–647. https://doi.org/10.2307/2082979

- Blanchard, O. (2017). A new index of external debt sustainability. Peterson Institute for International Economics Working Paper, 17/(13), 1–24.

- Bresser-Pereira, L., Oreiro, J., & Marconi, N. (2015). Developmental macroeconomics. Routledge.

- Brooks, S. (2004). Explaining capital account liberalization in Latin America: A. World Politics, 56(3), 389–430. https://doi.org/10.1353/wp.2004.0014

- Brooks, S., & Kurtz, M. (2008). Embedding neoliberal reform in Latin America. World Politics, 60(2), 231–280. https://doi.org/10.1353/wp.0.0015

- Brooks, S., & Kurtz, M. (2012). Paths to financial policy diffusion: Statist legacies in Latin America’s Globalization. International Organization, 66(1), 95–128. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818311000385

- Broz, L., Frieden, J., & Weymouth, S. (2008). Exchange rate policy attitudes: Direct evidence from survey data. IMF Staff Papers, 55(3), 417–444. https://doi.org/10.1057/imfsp.2008.16

- Burgoon, B., Demetriades, P., & Underhill, G. (2012). Sources and legitimacy offinancial liberalization. European Journal of Political Economy, 28(2), 147–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2011.10.003

- Campello, D. (2015). The politics of market discipline in Latin America: Globalization and democracy. Cambridge University Press.

- Cantamutto, F. (2016). Kirchnerism in Argentina: A populist dispute for hegemony. International Critical Thought, 6(2), 227–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/21598282.2016.1172325

- Chinn, M., & Ito, H. (2006). What matters for financial development? Capital controls, institutions, and interactions. Journal of Development Economics, 81(1), 163–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2005.05.010

- Chinn, M., & Ito, H. (2008). A new measure of financial openness. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 10(3), 309–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/13876980802231123

- Chodor, T. (2015). Neoliberal hegemony and the pink tide in Latin America. Breaking up with TINA?. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Chwieroth, J. (2007a). Testing and measuring the role of ideas: The case of neoliberalism in the international monetary fund. International Studies Quarterly, 51(1), 5–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2478.2007.00437.x

- Chwieroth, J. (2007b). Neoliberal economists and capital account liberalization in emerging markets. International Organization, 61(02), 443–463. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818307070154

- Chwieroth, J. (2015). Managing and transforming policy stigmas in international finance: Emerging markets and controlling capital inflows after the crisis. Review of International Political Economy, 22(1), 44–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2013.851101

- Clark, W., Hallerberg, M., Keil, M., & Willett, T. (2012). Measures of financial openness and interdependence. Journal of Financial Economic Policy, 4(1), 58–75. https://doi.org/10.1108/17576381211206497

- Crotty, J., & Epstein, G. (1996). In defense of capital controls. The Socialist Register, 32, 118–149.

- Dailami, M. (2000). Financial openness, democracy and redistributive policy. Policy Research Working Paper., World Bank. n. 2372. https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-2372

- Davidson, P. (2002). Financial markets, money and the real world. Edward Elgar.

- De La Torre, C. (2014). Populism in Latin American Politics. In the many faces of populism: Current perspective. Research in Political Sociology, 22, 79–100. https://doi.org/10.1108/S0895-993520140000022003

- Edwards, S. (1999). How effective are capital controls? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 13(4), 65–84. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.13.4.65

- Edwards, S. (2008). Globalisation, growth and crises: The view from Latin America. The. Australian Economic Review, 41(2), 123–140. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8462.2008.00498.x

- Edwards, S. (2010). Left behind: Latin America and the false promise of populism. The University of Chicago Press.

- Eichengreen, B. (2008). Globalizing capital. A history of the international monetary system. Princeton University Press.

- Eichengreen, B., & Leblang, D. (2008). Democracy and globalization. Economics & Politics, 20(3), 289–334. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0343.2007.00329.x

- Encarnation, D., & Mason, M. (1990). Neither MITI nor America: The political economy of capital liberalization in Japan. International Organization, 44(1), 25–54. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002081830000463X

- Epstein, G., Grabel, I., & Jomo, K. (2005). Capital management techniques in developing countries: An assessment of experiences from the 1990s and lessons for the future. In G. Epstein (Ed.), Capital flight and capital controls in developing countries. Edward Elgar.

- Etchemendy, S. (2011). Models of economic liberalization business, workers, and compensation in Latin America, Spain, and Portugal. Cambridge University Press.

- Etchemendy, S., & Puente, I. (2017). Power and crisis: Explaining varieties of commercial banking systems in Argentina, Brazil and Mexico. Journal of Politics in Latin America, 9(1), 3–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1866802X1700900101

- Fernandez, A., Klein, M., Rebucci, A., Schindler, M., & Uribe, M. (2016). Capital control measures: A new dataset. IMF Economic Review, 64(3), 548–574. https://doi.org/10.1057/imfer.2016.11

- Fine, B., & Saad-Filho, A. (2017). Thirteen things you need to know about neoliberalism. Critical Sociology, 43(4–5), 685–706. https://doi.org/10.1177/0896920516655387

- Flores-Macias, G. (2012). After neoliberalism? The left and economic reforms in Latin America. Oxford University Press.

- French, J. (2009). Understanding the Politics of Latin America's Plural Lefts (Chávez/Lula): Social democracy, populism and convergence on the path to a post-neoliberal world. Third World Quarterly, 30(2), 349–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436590802681090

- Frenkel, R., & Simpson, L. (2003). The two waves of financial liberalization in Latin America. In A. Dutt & J. Ross (Eds.), Development Economics and Structuralist Macroeconomics. Edward Elgar.

- Frieden, J. (2015). Currency politics: The political economy of exchange rate policy. Princeton University Press.

- Friedmann, G., & Puty, C. (2020). Sailing against the wind: The rise and crisis of a low-conflict progressivism. Latin American Perspectives, 47(1), 83–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/0094582X19884361

- Fritz, B., & Prates, D. (2018). Capital account regulation as part of the macroeconomic regime: Comparing Brazil in the 1990s and 2000s. European Journal of Economics and Economic Policies: Intervention, 15(3), 313–334.

- FSP. (1990). Declaração de São Paulo. http://forodesaopaulo.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/01-Declara%C3%A7%C3%A3o-de-S%C3%A3o-Paulo-1990.pdf

- FSP. (1991). Declaración de México. https://forodesaopaulo.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/02-Declaracion-de-Mexico-1991.pdf

- Gallagher, K. (2015a). Ruling capital: Emerging markets and the reregulation of cross-border finance. Cornell University Press.

- Gallagher, K. (2015b). Countervailing monetary power: Re-regulating capital flows in Brazil and South Korea. Review of International Political Economy, 22(1), 77–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2014.915577

- Gallagher, K., & Prates, D. (2016). New developmentalism versus the financialization of the resource curse: The challenge of exchange rate management in Brazil. In B. Scheneider (Ed.) New order and progress development and democracy in Brazil (pp. 78–104). Oxford University Press.

- Garrett, G. (1995). Capital mobility, trade, and the domestic politics of economic policy. International Organization, 49(4), 657–668. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818300028472

- Garrett, G. (2000). Capital mobility, exchange rates and fiscal policy in the global economy. Review of International Political Economy, 7(1), 153–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/096922900347081

- Grabel, I. (2017). When things don't fall apart: Global financial governance and developmental finance in an age of productive incoherence. MIT Press.

- Grilli, V., & Milesi-Ferretti, G. (1995). Effects and structural determinants of capital controls. Staff Papers - International Monetary Fund, 42(3), 517–551. https://doi.org/10.2307/3867531

- Grugel, G., & Riggirozzi, P. (2012). Post neoliberalism: Rebuilding and reclaiming the state in Latin America. Development and Change, 43(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.2011.01746.x

- Grugel, G., & Riggirozzi, P. (2018). Neoliberal disruption and neoliberalism’s afterlife in Latin America: What is left of post-neoliberalism? Critical Social Policy, 38(3), 547–566. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261018318765857

- Gwynne, R., & Kay, C. (1999). Latin America transformed: Globalisation and modernity. Oxford University Press.

- Haggard, S., & Maxfield, S. (1993). Political explanations of financial policy. In S. Haggard, C. Lee, & S. Maxfield (Eds.), The politics of finance in developing countries. Cornell University Press.

- Haggard, S., & Maxfield, S. (1996). The political economy of financial internationalization in the developing world. International Organization, 50 (1), 35–68. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818300001661

- Henning, R. (1994). Currencies and politics in the United States, Germany, and Japan. Peterson Institute.

- Henry, P. (2007). Capital account liberalization: Theory, evidences, and speculation. Journal of Economic Literature, 45(4), 887–935. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.45.4.887

- Hibbs, D. (1977). Political parties and macroeconomic policy. American Political Science Review, 71(4), 1467–1487. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055400269712

- Hidalgo, C., & Hausmann, R. (2009). The building blocks of economic complexity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(26), 10570–10575. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0900943106

- Hirschman, A. (2013). Exit, voice, and the state. In A. Hirschman (Ed.), The essential Hirschman, edited and with an introduction by Jeremy Adelman, afterword by Emma Rothschild and Amartya Sen (pp. 309–330). Princeton University Press.

- Hunter, W. (2007). The normalization of an anomaly: The workers' party in Brazil. World Politics, 59(3), 440–475. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0043887100020888

- IMF. (2009). Balance of payments and international investment position manual. International Monetary Fund.

- IMF. (2012). The liberalization and management of capital flows: An institutional view. International Monetary Fund.

- Kaltenbrunner, A. (2016). Stemming the tide: Capital account regulations in developing and emerging countries. In P. Arestis, M. Sawyer (Eds.), Financial Liberalisation: Past, Present and Future. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Karcher, S., & Steinberg, D. (2013). Assessing the causes of capital account liberalization: How measurement matters. International Studies Quarterly, 57(1), 128–137. https://doi.org/10.1111/isqu.12001

- Kastner, S., & Rector, C. (2003). International regimes, domestic veto-players, and capital controls policy stability. International Studies Quarterly, 47(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2478.4701001

- Kastner, S., & Rector, C. (2005). Partisanship and the path to financial openness. Comparative Political Studies, 38(5), 484–506. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414004272540

- Keohane, R., & Milner, H. (1996). Internationalization and domestic politics. Cambridge University Press.

- Kingstone, P., & Young, J. (2009). Partisanship and policy choice: What's left for the left in. Political Research Quarterly, 62(1), 29–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912908314198

- Kirby, P. (2003). Introduction to Latin America: Twenty-first century challenges. Sage.

- Kirshner, J. (2014). American power after the financial crisis. Cornell University Press.

- Korinek, A. (2011). The new economics of prudential capital controls: A research agenda. IMF Economic Review, 59(3), 523–561. https://doi.org/10.1057/imfer.2011.19

- Kregel, J. (2004). Can we create a stable international financial environment that ensures net resource transfers to developing countries? Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 26(4), 573–590. https://doi.org/10.1080/01603477.2004.11051418