Abstract

How do Chinese firms assess investment risk? I argue that major Chinese firms tend to invest in countries whose leaders they perceive as strong. However, their perception of a host country leader’s strength arises from a range of subjective and relational factors, including their party school socialization, Chinese state’s preferences for strong leaders, efforts by the host country regime to ‘sell’ the image of a strong leader, and information brokerage by Chinese think tanks. Thus, the path taken by Chinese firms cannot be fully explained by ‘objective’ measurable indicators such as policy bank financing or natural endowments; social relationships and norms are crucial too. There are also unintended consequences of investing in countries where they consider leaders to be strong. If the leader turns out to be weak, this ultimately increases the likelihood of cancellation of ongoing major Chinese projects. In contrast, if the leader is indeed strong, this strategy could result in pushback, leaving Chinese firms vulnerable to the leader’s whim to act against Chinese interests. To illustrate, I draw on elite interviews, contrasting Chinese investment in the Philippines under Arroyo (2001–2010) and Duterte (2016-), Malaysia under Najib (2009–2018), and Indonesia under Jokowi (2014-).

Chinese firms are at the front and center of China’s globalization, providing foreign direct investment (FDI) worth $3.8 trillion (UNCTAD, Citation2019) in stocks by 2018 and official Chinese financing around $351 billion between 2000 and 2014 (Bluhm et al., Citation2018). How do Chinese firms assess investment risk overseas?Footnote1 There are two competing accounts of the investment behavior of Chinese firms. First, the literature surrounding ‘Chinese exceptionalism’ argues that Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and private firms diverge from the conventional pattern of investing, instead selecting locations characterized by weak governance and pervasive rent-seeking (e.g. Buckley et al., Citation2007). Fundamentally, the Chinese exceptionalism literature has argued that Chinese firms perceive risk differently than multinational firms because the Chinese government is willing to politically and economically support investments in risky yet strategic areas. Second, in the last few years, several studies have emerged that draw from advances in the FDI literature, arguing that the findings of Chinese exceptionalism rely on aggregate data that is unable to disentangle country-, regime-, and project-level risks from one another (Chalmers & Mocker, Citation2017; Shi & Zhu, Citation2018; Zhu & Shi, Citation2019). There are also concerns regarding the inability of Chinese exceptionalism to account for temporal variation and sector specific feature.

Nonetheless, these competing accounts of ‘Chinese FDI studies’ make rational choice assumptions about Chinese firms, disembedding firms from their social context and ignoring the role of norms. Indeed, these works assume that Chinese firms exist in a vacuum, responding to fixed signals from Beijing, host country elites, and the projects themselves. In contrast, I propose a dynamic framework that links the prior experience of Chinese firms to the investment opportunities they encounter in the Global South. I argue that major Chinese firmsFootnote2 tend to invest in countries whose leaders they perceive as ‘strong’.Footnote3 However, their perception of a host country leader’s strength arises from a range of subjective and relational factors, including their party school socialization, Chinese state’s preferences, efforts by the host country regime to sell the image of a strong leader, and information brokerage by Chinese think tanks. Thus, the path taken by Chinese firms cannot be fully explained by objective measurable indicators such as policy bank financing and natural endowments; social relationships and norms are crucial too.

As major Chinese firms invest in leaders who are perceived to be strong, two different outcomes can emerge depending on the leader’s actual strength. If the leader is perceived to be strong but is actually weak, this strategy increases the likelihood of cancellation of ongoing major Chinese projects. The more that Chinese firms invest in the projects of the leader, the more likely that they position themselves as a firm supporter of the leader and marginalize other elites, which may further contribute to successful elite mobilization if the leader is weak. In contrast, if the leader is perceived to be strong and is actually strong, then pushback occurs. Host country leaders will realize their indispensability to the entire venture, and be more willing to pursue policies that could be detrimental to the Chinese state and firms on other fronts. In other words, in cases where Chinese firms get the leader right, they endanger their future stakes in the country as they become dependent on a leader who could turn their back any time.

Empirically, I examine two main cases that illustrate cancellation and pushback. I will first examine the case of a leader who was perceived to be initially strong but was actually weak – former Philippine president Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo (2001–10). During the early 2000s, Arroyo brought in six major Chinese projects but was unable to protect Chinese firms from the mobilization of Philippine elites and civil society organizations. At the end of Arroyo’s term, all but one of these major projects were cancelled. The second case analyzes a leader who was perceived as and was actually strong – Philippine president Rodrigo Duterte (2016-present). When Duterte became president, he capitalized on the opportunity to tap the Chinese state to fuel his political and economic goals. Duterte instigated a rapproachment with the PRC and his strength has decimated the opposition. At present, Duterte is leveraging his relationship with China to increase his rent payments by shielding online gambling firms from Beijing’s pressure. These investments worsen Filipino’s perceptions of China and facilitate money laundering, presenting clear problems for the Chinese state.

I strengthen the argument’s external validity by individually examining two shadow cases: Malaysia’s Najib Razak (2009–2018) and Indonesia’s Joko ‘Jokowi’ Widodo (2014-). Like Arroyo, Najib was perceived to be a strong leader, but elite and social mobilization weakened his position over time. Chinese firms were tied down to Najib through their willingness to participate in his rent-seeking ventures. Mobilization against Najib led to the cancellation or renegotiation of most of the major Chinese projects. Meanwhile, similar to Duterte, Jokowi’s ability to consolidate elite interests seems to be a winning formula to Chinese firms. These firms were able to successfully invest in Indonesia’s natural resources, energy, and infrastructures, ultimately tying down the Chinese players to Jokowi and his regime. However, reliance on Jokowi has resulted in pushback against the Chinese state, with Indonesia continuously resisting China’s overtures in the Natuna Islands.

I chose cases from Southeast Asia because the region has greater strategic significance for the Chinese state than other parts of the Global South (Bräutigam, Citation2011; Gallagher & Porzecanski, Citation2010). Unlike mainland Southeast Asia, the three maritime states have territorial disputes or disagreements with China in the South China Sea. These conditions encourage Chinese firms to work with strong leaders in these countries who could protect them from expropriation if, and when, disputes occur. I chose the Arroyo, Duterte, Najib, and Jokowi administrations because they all worked with the Chinese state to primarily put aside the disputes. While Arroyo and Najib were perceived to be strong but actually weak, Duterte and Jokowi were both perceived and actually strong. These differences in their perceived and actual strength illustrate the challenges of cancellation and pushback that China – major firms and the state - face when pursuing a strategy of investing in strong leaders.

I conducted over 120 elite interviews between 2017 and 2020, visiting Metro Manila, Hong Kong, Singapore, Kuala Lumpur, and Jakarta. Across the countries, I interviewed Chinese firm representatives, presidential advisers, senators, parliamentarians, party members, oligarchs, Chinese ministry officials and embassy representatives, and think tanks of various countries. It is very rare for these individuals to give their views publicly, and to my knowledge, this is one of the few studies of Chinese investments that has gained this high-level access across multiple countries. I conducted the interviews in multiple languages, exploring the perception of Chinese elites toward the Southeast Asian leaders, as well as how Southeast Asian leaders reacted to the Chinese actors. I also spoke to both the Chinese and Southeast Asian elites about the various major Chinese projects, cancellation, and pushback.

The Knightian assumptions of Chinese FDI studies

The literature on Chinese investments is divided between Chinese exceptionalism and those who argue against it. Chinese exceptionalism finds that Chinese firms disproportionally invest in places with patronage-driven institutions (Kolstad & Wiig, Citation2012), a huge number of cheap assets (Duanmu, Citation2012), and low amounts of Western FDI stock (Duanmu, Citation2012). This literature reasons that Chinese firms are not afraid of corruption and weak institutions because Chinese policy banks (e.g. China Export-Import Bank, the Chinese Development Bank) provide loan-financed investments that compensate for investment costs (Morck et al., Citation2008), or that the Chinese government, through the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, is able to convince the host country government to protect the interests of Chinese firms. More recently, authors working in this paradigm have analyzed the Belt and Road Initiative’s development impact (Buckley, Citation2020) and the US-China geopolitics (Duanmu & Urdinez, Citation2018). In sum, the core claim of Chinese exceptionalism is that because Beijing is willing to support politically-driven investments, Chinese firms have different risk calculations than Western firms.

Conversely, several new papers argue that Chinese exceptionalism’s explanatory capacity is limited. Two are worth mentioning here. Zhu and Shi (Citation2019) criticized Chinese exceptionalism’s reliance on aggregate FDI data, which is unable to disentangle the effects of, and relations among, country-, industry-, and firm-level factors. The authors argued that regime type, which some works on Chinese exceptionalism find to be crucial, cannot capture the specific institutional features that induce Chinese firms to invest. Instead, the authors find that Chinese firms are deterred by political and economic risks in the host country. For sectoral variation, Chalmers and Mocker (Citation2017) challenge Chinese exceptionalism by examining the investments of Chinese National Oil companies (NOCs). The authors argue that the most crucial variable that explains Chinese NOCs’ behavior is the question of who bears risk. Prior to 2006, the Chinese NOCs had less autonomy from the Chinese state but that the state was more willing to shoulder the investment risks. After 2006, Chinese NOCs were given more autonomy but were saddled with more of the investment risks. For both authors, this mechanism of risk allocation explains Chinese firms’ risk tolerance prior to, and risk aversion after, 2006.

Nonetheless, despite their disagreements over mechanisms and data, both schools of Chinese FDI studies share the same approach to risk. Chinese FDI studies’ ahistorical and decontextualized approach builds on the concepts of risk and uncertainty developed in Knight’s Uncertainty, Risk, and Profit. For Knight, risk is defined as ‘events subject to a known or knowable probability distribution’ while uncertainty refers to ‘events for which it was not possible to specify numerical probabilities’ (1921, 13). Modern corporations through their experts and networks of affiliates are able to transform uncertainty into risk, identify ‘homogenous groupings’, and ‘manage populations’ for long-term investments. For the Chinese exceptionalism literature, the Chinese state’s willingness to back politically-driven investments would therefore make risk knowable and investing more acceptable to Chinese firms, thus explaining their investments in risky environments. For the contrary works, Chinese exceptionalism does not have enough data with granularity and understanding of sectoral nuances to know whether or not the risk would be reduced. Either way, the Knightian assumptions built into much of FDI studies (e.g. Jensen, Citation2003) is also present in Chinese FDI studies.

These Knightian assumptions cause two problems. First, Chinese FDI studies ignore the social embeddedness of firms in China and their relations with the Chinese state. How firms understand investment risk, their domestic networks within China, and their interactions with the host country are ignored. At best, there are some cursory attempts to map out differential behavior based on direct state support and ownership type. For instance, Shi and Zhu (Citation2018, p. 4) suggest that private Chinese firms, in contrast to SOEs, act closer to Western MNCs. However, as other scholars have argued, Chinese SOEs and private firms at the highest levels cannot be distinguished from one another (Lee, Citation2018). Large private firms have similar political connections and policy linkages as the biggest SOEs (de Graaff, Citation2020), making the distinction between private and public firms in the Chinese context largely irrelevant. Rather, what needs to be analyzed is the national embeddedness of Chinese firms, both public and private. This includes what the social contexts, history, norms, and institutions of the People’s Republic of China do to shape the understanding of firms toward risk and host country context. Overall, this points to the unexplained dimensions of social embeddedness surrounding major Chinese firms. Such an approach entails taking the domestic linkages between firms and states seriously, beyond the notion of the Chinese state’s direct financial and political support.

Second, Chinese FDI studies ignore the temporal dimension of investment risk. The literature is largely quantitative and adept at finding cross-national patterns across sectors and regions, but less useful in accounting for how risk could change due to the dynamic actions of actors reacting to each other. I suggest that the quantitative approach assumes a static definition of risk that holds specific features in time without accounting for the understanding of risk has evolved, i.e. how Chinese actors’ prior understanding of risk interacted with the actions of host country actors. While Chinese exceptionalism ignores time, Chalmers and Mocker (Citation2017) focus on one data point that supposedly accounts for a major change in the behavior of Chinese NOCs. However, adjustment to events happen continuously and dynamically, particularly at the home-, host-, and project-levels. An analysis that takes feedback effect into account requires a deeper qualitative examination of the linkages between Chinese firms, host country actors, and the events at the project. Thus, examining risks qualitatively makes it possible not only to situate risks temporally, accounting for feedback effect and possible change, but also have a historically and contextually grounded understanding of risk. The next section presents my conceptual framework.

Socially embedding Chinese firms

I present a conceptual framework that builds on Dannreuther and Lekhi’s work (2000). They drew out Knight’s framework of boundary, knowledge, and organization, arguing that risk can be placed in one of three categories: rationally calculated, culturally mediated, or reflexively rooted in modernization. I build on a culturally mediated approach to risk, suggesting that meanings are embedded in the society from which it emerges (Granovetter, Citation1985), placing importance on the social norms and values that shape what is considered risky.

This cultural approach towards risk needs to be situated in the context of state and firm. To do this, I integrate this cultural approach with the literatures on IPE and the political economy of Chinese firms. For IPE, Stopford et al. (Citation1991) provide the foundations of the framework, arguing that states not only need to provide security for firms but also maximize the conditions of wealth creation. They recognize that country responses are hamstrung by their economic structures and social norms. Indeed, the role of culture and histories needs to be managed in dealing with firms, which, in the view of the authors, are driven by profit and efficiency. While I largely concur, the premise that firms are engines of profit in this competition for wealth conforms to the Knightian assumptions of rationality. In contrast, I follow the cultural approach to risk and argue that firms are socially embedded, placing emphasis on the role of history and norms in the firms’ relationship with the sending (Chinese) and recipient (host country of Chinese investments) states. Footnote4

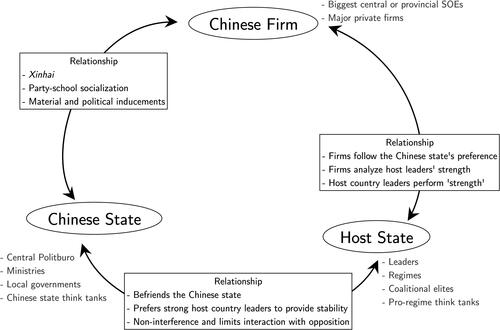

In this framework (see ), firms are the primary actors that act on signals by the Chinese state and host country. Chinese Communist Party (CCP) cadre members, who become the executives, board members, and managers of Chinese SOEs, are educated in the Chinese party school system, comprising approximately 2700 schools (Lee, Citation2015, p. 14). For major private firms, Chinese businessmen who join or work with the CCP often need to go through the same party schools or state-driven universities.Footnote5 Apart from a shared socialization, the personal connections of the executives to the Chinese state at various levels shape the information, outlook, and approach of the firm towards the investment risk (e.g. Gu et al., Citation2016; Pei, Citation2016). For major private firms, many of their executives are former party, state, or SOE officials who left the Chinese government, often getting recruited in management. These ex-officials turn entrepreneurs, the so-called xiahai (Dickson, Citation2003, p. 45), maintain and use their strong party connections.Footnote6 In either case, the social space upon which these executives - ex-cadre and businessmen party-members - exist are shared with the Chinese state officials, which becomes one of the most important sources of information and meaning on investment risk (Huang & Chen, Citation2016).Footnote7

Chinese firms interpret the investability of a host country in concert with their party school training and previous investment experience within China. Party school education shapes how CCP cadre and firm executives interpret investment risk. There has been a decrease in teaching orthodox Marxist theory since the late 1990s and an increase focus on international events, studying the recent history of China’s modernization and its integration in the global economy (Lee, Citation2015, p. 154). Those in the party school spend their time ‘studying the experiences of Asian Tigers, understanding international affairs, and viewing internally circulated films on the downfall of communist parties in Europe and the Soviet Union’ (Lee, Citation2015, p. 165). This shift in the curriculum reflects on what the party schools believe is an ideal cadre member, possessing the ‘five capacities’ of scientific judgement, market economic management, coping with complex situations, adhering to the rule of law, and managing difficult situations (Lee, Citation2015, p. 169).

In the absence of similar institutions in the Global South, Chinese executives in SOEs or major private firms, from their own lessons of international events, are wary of the multiple power holders – armed or politically-important elites, civil society, and social movements – that could derail an investment project.Footnote8 As such, Chinese executives interpret investable host countries as those ruled by leaders who could provide strong leadership, political stability, and policy predictability. In China, the Central Politburo (CP) promotes and works with provincial elites who crush radical movements, protect the business environment, and maximize wealth-creation (e.g. Li, Citation2019). These leaders somewhat reflect the ‘five capacities’ needed to strengthen the CCP that is identified in the party school curriculum.Footnote9 These ‘strong’ leaders regularly ascend from provincial to national-level leaderships, conforming to the executives’ view that Chinese economic development would not have been possible had there been multiple powerholders to interrupt China’s rise. In other words, Chinese executives gauge the investability of regimes by comparing their experience of working with provincial Chinese leaders with the host country leader.Footnote10

The degree to which the Chinese state can direct the firms to invest or participate in a project vary. The Chinese state – defined as the Central Politburo along with the main ministries – exercise considerable influence by setting the agenda, signaling new opportunities, and allocating financial support (e.g. Kastner & Pearson, Citation2021). However, the decision to participate or bid for the project is often up to the firm. The degree of state mandate varies and could wane over the investment process where provincial governments or firm-level decisions take on precedence (Lee, Citation2018). As the framework focuses on major firms, the Chinese state can signal opportunities through their ex-cadre members and party-member affiliates in the firm. The Chinese state could incentivize firms by offering political capital or economic assistance through the policy banks (Gu et al., Citation2016). Nonetheless, Chinese executives and firms have agency over their participation in investment projects. I suggest that the perceived strength of the host country leader is crucial in their decision making.

Like the firms, the Chinese state is also wary of multiple power holders (e.g. Hung, Citation2020b). This wariness is informed by China’s experience of competing with Taiwan for sovereignty and limiting Hong Kong’s autonomy. As the Chinese state expects host country leaders to fully recognize the CCP’s sovereignty over China and Taiwan, the Chinese state accords this same level of respect to host country leaders. Known as the principle of ‘non-interference’, an unexplored implication of this approach is the Chinese state’s preference for working with those who hold legitimate power, either through elections, elite consensus, or military junta. These preferences are reflected in the Chinese state’s institutional protocols that privilege the regime in power, limiting interactions with, and information acquisition from, opposition elites and non-government organizations (NGOs). As Alden and Hughes (Citation2009) argued, the Chinese state and the firms largely engaged with governments in Africa due to the lack of experience and procedures on how to deal with NGOs. Although the Chinese state and firms have engaged more with Burmese NGOs (Zou & Jones, Citation2020), these engagements still occurred under the umbrella of China’s ‘win-win’ cooperation. In other words, the institutional protocols of the Chinese state still privilege the regime in power, limiting any meaningful engagements with opposition politicians or NGOs without the host state leader’s approval.

In front of the Chinese state and firms, host country leaders ‘prop up’ their investability by presenting their own regime and leadership through the lens of strength. IPE scholars have found that states in international settings need to perform ‘stateness’ as a way to demonstrate authority and interests (e.g. Hopewell, Citation2015). Extending their insights, I suggest that because host country leaders need investment, there is an incentive to selectively present information about the leader’s strength and the country’s stability. This draws from Goffman’s (Citation1978) ‘presentation of the self’, which is strategically deployed by host country leaders and their regimes. The regime would recommend business partners who would also present favorable views about the leader. Furthermore, though networks between Chinese firms and host state business elites are formed (de Graaff, Citation2020; Hung, Citation2020a), the latter group has the incentive to generally reflect the views of the regime in order to keep the investment project alive. Additionally, regime-approved think tanks or NGOs work with the Chinese actors to maintain the regime’s image. Put differently, there is a self-reinforcing relationship between the Chinese actors’ – firms and state - preference for working with those in power and the host state regime’s performativity.

The Chinese think tanks that have come to pervade the Chinese state, firms and host regimes are crucial non-state actors in these processes. They gather information on investment risks as well as conduct their own assessments for their own business (e.g. Abb, Citation2015). A central point in the rise of think tanks is that China’s globalization generated multiple problems that the state alone cannot handle directly. Think tanks, often located in the grey area between government and non-government, have the flexibility to deal with issues that require more suppleness - working with host country elites, NGOs, and their counterparts to acquire information. Chinese think tanks are akin to Western credit-rating agencies, which Soudis (Citation2015) has described as performing an information brokerage role for investing countries. However, unlike credit-rating agencies, Chinese think tanks are constrained by the norms and institutions of the Chinese state. Accordingly, I suggest that they also suffer from the same problem of selectively dealing with host country regime’s elites.

How do Chinese firms, state, and think tanks deal with feedback effects? I suggest that feedback effects can alter the belief in a host country leader’s strength, but it is a long and complex process that might not give the Chinese actors sufficient time to adjust. The reason for this lag is because the Chinese state and firms prioritize the information that they receive from the host country leaders and their elites over other sources. To a large part, this goes back to the Chinese state’s institutional structure of prioritizing relationships with host country leader counterparts, casting doubt on information from opposition political parties, social movements, and the international community. This doubt leads to mutual distrust and selective engagement between the Chinese state and firms with opposition elites and social movements. Another reason is that Chinese state actors and firms prioritize their personal relationship and own experience with host country leaders. Nonetheless, once major events occur, such as the cancellation of, or attacks against, multiple Chinese projects, Chinese actors will gradually adjust their impressions of the host country leader accordingly. This lagged feedback effect links back to what Nightingale (Citation2000) called ‘costly redesign feedback loops’, where changes in one subsystem could only be solved by changing interdependent systems. As the Chinese state institutions are difficult to change and norms are well-embedded, feedback effects will be slow. The behavior of Chinese firm executives will be difficult to alter quickly.

Perceived to be strong, actually weak: cancellation under Arroyo (2001–2010)

While Arroyo had dealt with China before, she was largely an unknown to Chinese firms.Footnote11 After deposing Joseph Estrada (1998–2001) and coming to power, the Chinese came to perceive her as a strong leader. Between the Chinese government and Arroyo was Francis Chua, one of the leaders of the Federation of Filipino-Chinese Chambers of Commerce Inc. (FFCCCI). Chua, a member of Arroyo’s circle, is a Filipino economic elite outside the well-established ranks of the Philippine oligarchy, who wanted to build stronger ties with China in order to benefit his business enterprise.Footnote12 Chua sold Arroyo’s image to China, promoting her sincerity, expertise, and intelligence in protecting the interest of the Chinese firms and state. A political broker familiar with the deal notes that ‘when Estrada was deposed, we sold Arroyo to the Chinese. We focused on her popularity among Filipinos, respect among factions of the elites, the fealty of the armed forces and police, and her practicality’.Footnote13 Indeed, Arroyo was widely popular in the early stages of her rule, garnering a 63% popularity rate between 2000 and 2003 - far higher than her predecessor (Camba, Citation2017). Arroyo united factions of the left, won the support of the coercive apparatus of the state, and led a coalition of political parties.

The Chinese government also formed their opinions on Arroyo and the Philippines based upon their interactions with Arroyo herself. In an interview, a former Chinese ambassador in the Philippines recalled being invited to the Presidential Palace in early 2000s. He stated that ‘[Arroyo] doesn't say much to her people working for her, but they know what to do. They follow her orders, and they respect her. That reminded me of a lot of leaders back in my country’.Footnote14 To a Chinese think tank analyst, he explained that ‘if you win Arroyo, you win the Philippines. So, the support for projects kept on pouring’.Footnote15 Put simply, winning Arroyo’s friendship was an opportunity to secure the Chinese state’s goals of placating opposition in the South China Sea and supporting Chinese firms looking for new opportunities (Camba, Citation2017).

In October 2001, Arroyo visited China and held bilateral talks with Chinese President Jiang Zemin. With the support of the Chinese leadership, China Import-Export (CHEXIM) and other Chinese banks made loans available to Arroyo’s Philippines, funding projects that Chinese firms and the Arroyo government want. Similar to the Chinese state, major Chinese investors and firms formed their opinion of Arroyo through Chua, who was their middleman to various Philippine elites at that time. For instance, a group of Chinese investors visited the Philippines in 1999 went through Chua and the FFCCCI rather the Philippine Department of Trade and Industry under the Estrada government. Between 1999 and 2003, there were 13 visits by groups of Chinese investors that Chua and the FFCCI welcomed to the country.Footnote16 Other Chinese investors also capitalized on Chua and his connections.Footnote17

Filipino think tanks and organizations that met with Chinese think tanks propagated the same, favorable view.Footnote18 By 2005, several major Chinese think tanks met with Philippine academics who had strong links with the Arroyo government at that time. Indeed, established Filipino academics who went to China constituted the initial linkages between the Chinese and Arroyo’s governments.Footnote19 While the Chinese actors consulted various pro-Arroyo Philippine actors, the Chinese state never consulted opposition elites, civil society, or other organizations that would put forth a different point of view about the Philippines. An interview with a Philippine Senator, who was one of the few opposition leaders against Arroyo at that time, said that ‘the Chinese government never approached us. We never developed a relationship with them, and we felt that they were always on Arroyo’s side’.Footnote20 As explained by a Philippine Congressman who heads one of the two major leftist groups in the country, ‘for the Chinese, we were simply enemies of the state. We never approached them too’.Footnote21

Apart from their own calculations, Chinese firms based their decisions on the actions of the Chinese state, host country elites, and Chinese think tanks. Despite the Chinese state’s financial and political support, Chinese firms at this point had an opportunity to not participate and pursue other endeavors elsewhere. Thus, what made some firms participate was their shared belief of Arroyo’s strength. As explained by a Chinese manager in one major investment project, ‘[at the start] Arroyo seemed to be a strong leader. She possessed ability to govern in the world today. These are talents we also value in China.’Footnote22 In the same interview, I asked the manager why was strength even a major consideration for investment instead of institutional stability, profitability, and domestic markets. Referring to the party school that CCP cadre and businessmen had to attend, he explained that ‘there are lot of unknowns in investing outside China. As we learned from our lessons that we all took to study international politics, there is a lot of infighting in other countries’.Footnote23 This quote was also echoed by the Vice President of a Chinese SOE who, when asked about the importance of strength, said that ‘infighting was bad for China, the leader had to be capable in handling rivals. So, here [outside China], the only thing we can count on is the leader’s strength’.Footnote24

Although other factors are important, such as economic viability or incentives from the Chinese government, strength is a key reason for Chinese firms to invest. From the interviews with the firms, it seems to be that the project’s economic viability is secondary to the strength and the positive predisposition of the leader.Footnote25 In speaking with an executive of another SOE, he explains that ‘deals are flexible to win the goodwill of the leader, and we also adjust this to short-term and long-term gains. This explains why, for example, ZTE, a telecommunications company, tried to invest in a $2 billion mine in the Philippines’.Footnote26 The Vice President was referring to the ZTE’s attempted investment in Nonoc mines, which confused Philippine commentators and analysts because the firm had no experience in the extractive industries (Gamboa, Citation2018). Arroyo supported the bid before it was shot down by local elites.

However, the perceived and actual strength of the leader is different. As I argue, when the leader is perceived to be strong but actually weak, it increases the likelihood of cancellation as the leader is unable to protect Chinese firms from opposition elites. In the Philippine case, there comprise a variety of competing elites with different interests. Some wanted to bring Arroyo down, others thought Arroyo was selling Philippine assets to China, and a few, particularly members of the Philippine oligarchy, worried about the impact of the deals on their monopoly of the Philippine markets. Indeed, Chinese actors – state, think tanks, and firms - perceived Arroyo to be strong in the early 2000s, limited interaction with the opposition, and largely relied on Arroyo, hindering their ability to see the shifts in the balance of power in the Philippines. After the 2004 Philippine elections, the opposition was arguably more powerful than the administration. The Chinese were not fully cognizant of these dynamics and still progressed the investment deals agreed upon before 2004. Even after the opposition gained ground, the approach of Chinese firms and state in befriending the leader and limiting their interaction with opposition elites constrained their capacity to adjust quickly. Below, I summarize several outward investments and analyze Arroyo’s inability to protect the Chinese firms.

First, one project was a construction contract between the Philippines’ Department of Transportation and Communication and the Zhongxing Semiconductor Corporation (ZTE). Signed in mid-2007 and worth US$329.5 million, ZTE acquired a loan from CHEXIM in order to upgrade National Broadcasting Network’s (NBN) telecommunication infrastructure. Jose De Venecia Jr., one of the most important elites in Arroyo’s administration, had his son’s company, Amsterdam Holdings Inc. (AHI), bid for the deal. AHI legitimately won the bid but was later encouraged to bow out in favor of ZTE due to threats from Arroyo’s people. De Venecia defected to the opposition and mobilized against Arroyo. Mass protests of approximately 15,000 to 75,000 people occurred regularly in Metro Manila’s business center.Footnote27 Multiple congressional hearings about the deal and several ombudsman investigations against Arroyo’s family went on from July to October 2007. Eventually, the NBN-ZTE scandal culminated in a Supreme Court moratorium in October 2007.

A second case was a $503 million construction contract to build a 32-kilometer railway. A 20-year CHEXIM loan with 3 percent annual interest (Camba, Citation2017), earmarked for the North Luzon Railway (North Rail), was used to hire the China National Machinery and Equipment Group (CNMEG) to work with the Philippine North Luzon Rail Corporation to upgrade and modernize existing Philippine railway infrastructure. While this project progressed until 2007, De Venecia’s defection fueled the opposition against CNMEG.Footnote28 Opposition elites took advantage of the situation by mobilizing against North Rail. Members of congress started legislative hearings about North Rail in 2008. The opposition also decided to take the matter out of the legislature and into the courts, the media, and the streets. Similar to ZTE, renewed street protest roughly with the same number of people occurred in Metro Manila in the first and second quarters of 2008. Mobilization against North Rail also began in nearby cities, particularly in Tarlac, Pangasinan, and Bulacan.Footnote29 Eventually, the opposition filed a Supreme Court injunction against North Rail, pushing Arroyo to effectively place a moratorium on the project.

For both the ZTE and North Rail, Arroyo was unwilling to use the military or police against the opposition elites. She had already lost clout at that time, which meant that using either organizations would have likely led to a coup. Elites also mobilized against all the other major Chinese projects,Footnote30 particularly the $2.5 billion mining investments of the Jinchuan Non-Ferrous Metal Corp and ZTE, the $1 billion agro-export investment of the Fuhua Agricultural Science and Technology Development Co., and the $3 billion investment of the International Construction Bank of China (see Camba, Citation2021a). All these projects initially moved forward because Chinese firms believed that Arroyo was strong, but her actual weakness led to cancellation of the deals (see ). China’s institutional structures, which largely worked with regime (Arroyo) elites limited the feedback effect. As the former Philippine Vice President of ZTE saidFootnote31:

Table 1. Major Chinese Projects, Arroyo (2001–2010).

We really did not know how unstable her administration was until we [ZTE] got cancelled. Our Philippine counterparts kept telling us that the opposition just wanted to bring down Arroyo. We lost money in the Philippines. Other firms changed their minds after 2009 [when ICBC was cancelled] when they saw that Arroyo was actually far weaker than she is.

Perceived to be strong, actually strong: pushback during Duterte (2016-)

Before discussing Duterte, there should be a brief mention of the effects of, and the administration that came after, Arroyo’s administration. The cancellation of multiple deals in the Philippines made the Chinese wary of Philippine politics and more cognizant of the multiple powerholders in the country. Additionally, there was enmity to non-militarized territorial disputes between the Philippines and China. Benigno Aquino III (2010–2016) disputed China’s claims in the South China Sea, which led to the deterioration of Philippine-China relations (De Castro, Citation2019). The Chinese government was also burned by their relationship with Arroyo because of the domestic elites and population’s backlash against China. It made the entire effort of investing in Arroyo’s government not only futile but also counterproductive to the Chinese government’s goals. Aquino III resisted the Chinese government and rallied most of the Philippine elites to his position (see Camba, Citation2018). To win the Philippines over, China thus needed a Philippine leader who is not only open to dialogue but also willing and able to police Philippine elites.Footnote32

By the time Duterte came into power, the Chinese government already viewed him as a promising leader. Duterte was not new to China. Links between the Chinese government and Duterte’s people started as early as the 2000s when Dennis Uy, a known Duterte financier and Davao-based businessman, started to export fruits and minerals to China.Footnote33 Bong Go, Duterte’s former righthand man and a current Philippine Senator, allegedly visited China several times, communicating with members of the CCP in 2014.Footnote34 As one of Duterte’s aides said in an interview, ‘we established links with the Chinese government early on because they will be an importance source of investments and markets for those in Mindanao. We knew they were looking for someone strong enough to keep the peace between the Philippines and China’.Footnote35

In October 2016, Duterte met with the Chinese government with over 200 well-connected businessmen. While the Chinese had an idea who Duterte was, the Philippine delegation focused on a strategy of selling Duterte’s strength, particularly his willingness and capacity to use violence. In an interview with a Davao-based businessman who accompanied Duterte, he said that, ‘we were selectively invited since many of us supported his campaign and could benefit from China too. Before we went, we were briefed to talk about how strong of a leader Duterte is, such as his death squads and strict policies in Davao’.Footnote36 These delegates exceedingly praised Duterte’s no-nonsense approach to drugs, enmity towards human rights, and disgust with protestors.Footnote37 A well-connected businessmen in the Philippine beauty industry said that he stuck to talking points around Duterte’s battle against the Philippine oligarchy, American imperialism, and weariness over the maritime disputes.Footnote38 While Arroyo was framed to be an intelligent and skilled technocrat, Duterte was seen as an anti-colonial strongman who could be a promising ally for the Chinese government.Footnote39 Dialogues between Chinese think tanks and their Philippine counterparts repeated Duterte’s own narrative: a silent majority that supports him, fake news peddled by the Americans and the oligarchs, and elite consolidation.Footnote40

While China needed Duterte for geoeconomics reasons (De Castro, Citation2019), they also needed a leader who could check Philippine elites. In talking about these statements, an interview with a delegate from the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs said that, ‘we were not sure about him [Duterte] at first, but we needed someone strong. Unlike China, it’s difficult if you do not know who is in charge of the country’.Footnote41 After the October 2016 state visit to Beijing, Duterte showed that he was much stronger than Arroyo, willing and able to deploy force against Philippine elites. For example, Duterte moved money to the discretionary intelligence fund, which was used on police spending. Duterte’s intelligence fund gradually increased yearly, reaching 230 million USD by 2020, which was 4 times the amount of his predecessors (Rappler, Citation2021). These funds were not only used in the drug war but, importantly, also against anti-Duterte elites. In first full year of his rule, Duterte’s administration killed several Philippine mayors, filed cases against a handful of governors, and incarcerated a senator (Elemia, Citation2016; HRW, Citation2017). For instance, mayors Rolando Espinosa and Samsudin Dimaukom, were killed during their encounters with the police (Hinks, Citation2017).

Duterte’s actions sent a message to Philippine elites - work with us, let’s make money together, or else face the consequences – and China interpreted this as proof of Duterte’s strength. This willingness to use force was an act that Arroyo never did. In an interview with a firm executive in one of the Chinese construction firms, he said that, ‘Duterte punished those elites. This was something that the other Philippine leaders could not do, or they [the governments] were taken over by people who believed in US propaganda’.Footnote42 In an interview with a consultant in one of the Chinese dam projects in the Philippines, he said that, ‘my colleagues and I believe that Duterte has the capacity to stand up to the elites and lead the Philippines using scientific governance’.Footnote43 Chinese firms have always wanted to expand in the Philippines, which had one of the lowest levels of FDI and foreign aid in Southeast Asia (Camba & Magat, Citation2021). During an interview with a Chinese SOE manager looking to invest in Philippine railways, I asked why the Chinese actors are willing to believe in Duterte even though Arroyo failed them. The manager said that, ‘the difference is that everyone is saying that Duterte is strong. Americans keep calling him a dictator, and he [Duterte] even cussed Obama. We also know the truth from our personal experience, and our think tanks also praised Duterte’s strength’.Footnote44

Duterte’s proof of his strength resulted in many of the agreed-upon investment and foreign aid projects. While Duterte and Xi agreed upon a $24 billion deal in October 2016, the viable projects only moved forward at the end of 2017 after Duterte proved his strength. However, the issue with working with a leader who is actually strong is that this leader can pushback against Chinese interests. Chinese projects moved forward but Duterte took the opportunity to invite Chinese online gambling firms to the country, which are criminal enterprises for the Chinese government. Let me briefly illustrate some of the deals that are moving forward and Duterte’s online gambling boom, his pushback against Beijing.

The first deal is the Kaliwa Dam (hereafter, Kaliwa), located between the municipalities of General Nakar and Infanta in Quezon province. Kaliwa is intended to store 57 million cubic meters of water in 113 hectares in a 60-metre-high dam. In 2018, CHEXIM lent a $211 million loan to the Duterte government to build the dam. The China Energy Engineering Corporation Limited won the bid to construct the project.Footnote45 As Kaliwa’s construction began, the government railroaded various procedures, such as manipulating the rate of internal economic return (Cruz & Juliano, Citation2021), expediting the free and prior informed consent (Camba, Citation2021b), and ignoring the commission of audit’s protest about Kaliwa (Camba, Citation2020a). Communities were forcibly evacuated from their homes (Gotinga, Citation2019). Due to these issues, multiple civil society groups organized mobilizations (Gotinga, Citation2020) but Duterte responded by incarcerating civil society organizers. By and large, Philippine elites refused to join the movement against Kaliwa, illustrating how Duterte’s strength paved the way to silencing the majority of elites.Footnote46 Ultimately, Kaliwa is progressing and even made substantial progress despite the COVID-19 pandemic.

The second deal is Dito Telecommunity (hereafter, Dito), a $5 billion joint venture between China and Duterte-crony Dennis Uy.Footnote47 Since the early 2000s, Philippine telecommunication has been dominated by two Philippine consortiums (Camus, 2018). With the intention to break this oligopoly, Duterte engineered a Dito Telecommunity victory, rigging the bid over the two other firms. Specifically, National Telecommunications Committee (NTC), the state body that facilitates the bidding and approval of telecommunications firms, was staffed by Duterte loyalists.Footnote48 During the final round of the bidding, the NTC awarded the license to Dito over Sears Telecom and PT&T (Rivas, Citation2018). The two losing firms believed NTC gave an arbitrary decision in favor of Dito. Sears thought of filing a Supreme Court case, but a lawyer close to the deal said that, ‘the other firms tried to reach out to other politicians to get support, but no one wanted to do anything. The previous decision to stack NTC with loyalists could have been contested, but no one did it. What more of a billion-dollar deal?’Footnote49 Overall, apart from Kaliwa and Dito, most Chinese projects are signed, progressing or completed (see ). Not a single Chinese project has been canceled by elite or social mobilization.

Table 2. Major Chinese Projects, Duterte (2016-).

However, working with leader who is actually strong could result in pushback. Specifically, leaders push back on China’s interest, using their indispensability to the relationship as leverage to pursue conflicting policies on other fronts. Duterte has used his newfound leverage to attract and protect Chinese online gambling firms, which are allegedly owned by ex-Chinese citizen billionaires (Camba & Li, Citation2020). Since 2017, approximately 128 new online gambling firms have successfully expanded in the Philippines despite the Chinese government’s objections (Camba & Li, Citation2020). These firms knew that the Duterte government’s support was crucial to their success, so many of them partnered with Duterte’s cronies.Footnote50 The Chinese government has repeatedly asked Duterte to shut down the firms, even filing extradition cases against dozens of Chinese citizens (Venzon & Turton, Citation2019). However, at the time of the paper’s writing, Duterte’s government has indirectly helped import illegal Chinese workers (Rivas, Citation2019), foster illicit sectors (Luna, Citation2020), and launder money (Camba, Citation2020a).Footnote51

Investments by the online gambling sector led to a surge of real estate prices in Metro Manila and other major cities, vastly angering Filipinos (Luna, Citation2020). This backlash against Chinese online gambling comes at the expense of the Chinese state and major firms. Indeed, every goodwill mission by China is rebutted by the problems generated by online gambling in the Philippines (Camba, Citation2020c). In actuality, the Chinese government and online gambling firms are mutually influencing the Duterte government through their different networks in the government.Footnote52 But with the expansion of the online gambling firms, it becomes more and more apparent that the Chinese state and major firms placed all their eggs in one basket. Put simply, they now have no choice but to accept that online gambling firms will be going into the Philippines. As a top Chinese official in the Manila embassy said:

We filed many extradition cases against high level individuals [Chinese citizens involved in online gambling] between 2017 and 2019. But even now, we are only getting minor workers and occasional policing against the firms. We can't pressure Duterte because other things are more important. We need to maintain our relationship.Footnote53

Two shadow cases: investing in Najib (2009–2018) and Jokowi (2014-)

This final section analyzes two shadow cases to reinforce the paper’s external validity. First, Najib Razak established strong economic relations with China. Malaysia follows a multi-party system and the ruling coalition exercises significant power (Gomez & De Micheaux, Citation2017). For decades, the United Malay National Organization (UMNO) united the other political parties under Barisan Nasional coalition. Malaysia is largely an authoritarian state and becomes an elite-led democracy at times (Lim et al., Citation2021). Just like the Arroyo administration, the Malaysian government billed Najib as a ‘strongman’ who wields absolute power over the UMNO and can suppress elite mobilizations.Footnote54 For the Chinese state and firms, it was easy to fathom since Malaysian political economy depends on the ruling leader, party, and elites.Footnote55 As a manager of a Chinese firm in steel production said, ‘UMNO has been in power since the 1960s, having centralized political and economic rent distribution while also co-opting the traditional [Malaysian] ‘kings’ in the process’.Footnote56

During Najib’s administration, Chinese firms engaged in several projects designed to overprice Malaysia’s payments of, and move payments for, Chinese construction contracts to allegedly pay for 1MDB’s debt. The East Coast Railway (ECRL), a project that links the wealthier Western states to the poorer Eastern provinces, was overpriced by $2.4 billion (Liao & Katada, Citation2021). Overpriced contracts were also awarded to Chinese firms in the TSGP oil and gas pipeline and MPP Malacca-Johor pipeline (Strait Times, Citation2018). China’s Xiamen University in Malaysia was formed with Najib’s Malaysian Chinese Association cronies. The Malaysia China Kuantan Industrial Park (MCKIP) was built in Najib’s home province of Pahang.Footnote57 Najib’s presence gave Chinese firms a sense of security in these ventures.Footnote58 The only project that did not go directly through Najib is the controversial Forest City, which was an overinflated real estate project (Liu & Lim, Citation2019). Nonetheless, the Sultan of Johor and Najib have good relations, which means that the framework is still applicable. The other Chinese projects were also indirectly supported by Najib ().Footnote59

The 1MDB scandal and intense opposition against Najib led to Mahathir Mohamad’s (2018–2020) surprise victory, which marked UMNO’s first electoral loss for half a century. While numerous factors account for Najib’s loss, it is the pattern of investments that largely focuses on catering to Najib at the expense of other elites that directly affected Chinese firms.Footnote60 Despite Mahathir’s long-standing reputation to have engaged China during the 1980s, Chinese firms largely worked with Najib and his handpicked elites.Footnote61 When Pakatan Harapan, Mahathir’s coalition, came into power, it renegotiated some deals and scraped some overpriced contracts. For instance, the ECRL’s renegotiated deal included greater participation for Malaysian SOEs through the transit-oriented development.Footnote62 Six out of ten major Chinese projects during Najib were cancelled, delayed, or renegotiated (see ).Footnote63 Overall, Najib is another leader who is perceived to be strong but is actually weak, resulting the cancellation of several major projects after intense elite mobilizations.

Table 3. Major Chinese Projects, Najib (2009–2018).

Joko ‘Jokowi’ Widodo acquired civil society support on his route to win his first term. Nahdlatul Ulama, the largest Sunni Indonesian religious organization with millions of members, mobilized mass support for Jokowi.Footnote64 Under the Partai Demokrasi Indonesia Perjuangan, Jokowi became president, garnering sufficient elite support and an initially strong base among the Indonesian populace.Footnote65 Jokowi used infrastructure development to strengthen his rule, announcing the ‘Global Maritime Fulcrum’ (Tritto, Citation2020, Citation2021), an infrastructure initiative that is intended to expediently build roads, railways, and bridges across Indonesian to attract manufacturing FDI.

Chinese firms patterned their investments by catering to both Jokowi’s development strategy and his elites.Footnote66 The Jakarta-Bandung Highspeed Railway (HSR) was given to the Chinese firms because of their willingness to turn the project into an FDI-financed venture, a preference of the Jokowi administration (Camba, Citation2020b). The Indonesia Morowali Industrial Park (IMIP), a joint venture between a Chinese and Indonesian firm that was planned under the previous regime, has been facilitated through Luhut Binsar Pandjaitan, Jokowi’s righthand man. IMIP combines efficient nickel extraction with the latest smelting technologies.Footnote67 Luhut and Jokowi also tapped Chinese firms to increase the number of energy projects across the country (Wijaya, Citation2021). All these projects represent a broader trend of Chinese firms investing with some of Indonesia’s SOEs and Jokowi-linked Indonesian oligarchs in energy, infrastructure, and natural resources.Footnote68

Jokowi is a leader who is perceived to be strong and is actually strong. Elite and social mobilization against Jokowi has largely been unsuccessful. Prabowo Subianto, Jokowi’s opponent in the 2019 elections, attempted to politicize the Jakarta-Bandung HSR by bringing up the debt of the project. Jokowi incorporated Prabowo’s political party in a coalition after he won the election. There was also social mobilization against IMIP (Camba et al., Citation2020), which was stopped in the first instance by the Indonesian military in 2014.Footnote69 Due to the nickel export ban of the Indonesian government, IMIP and other mining-smelting firms control the sector since domestic nickel companies are unable to export, leading to extortionary prices (Camba et al., Citation2020). Put differently, the export ban has disproportionally benefited IMIP and all the other mining-smelting firms supported by Jokowi’s regime.Footnote70 At the time of this writing, the lobbying of nickel mining companies has not generated any traction.

Overall, Jokowi’s strength has helped attenuate elite mobilization, allowing Chinese firms to complete their investments (see ). Despite the continuation of these projects, pushback has occurred against China. At the moment, Jokowi is pushing back on China in the South China Sea’s Natuna islands (Reuters, Citation2020). As a captain in the Indonesian coastguard has argued, ‘Jokowi mobilizes the navy and coastguard against Chinese fishing boats. We give them no quarter. If we give them an inch, they take a mile’.Footnote71 Just like in the Philippines, the Chinese state and major firms have now been reliant on Jokowi and his coalition.

Table 4. Major Chinese Projects, Jokowi (2014–).

Conclusion

Building on over 120 elite interviews across five countries, I found that Chinese firms prefer to work with national leaders whom they perceive as strong. If the Chinese firms get it wrong, it results in cancellation where the national leader is unable to protect the Chinese firm from elite and social mobilization. If the Chinese firms get it right, pushback occurs where host country leaders use their indispensability to pushback against the interest of the Chinese state and firms. I make four conceptual contributions to IPE. First, the paper employs a cultural approach to investment risk, arguing that firms draw from their own social norms, departing from the conventional Knightian assumption of firm rationality. This argument illustrates the concept of ‘social embeddedness’, which is usually used to analyze states in the IPE literature but rarely applied to firms. Applying this cultural approach to investments opens new avenues of research in IPE, particularly by examining how firms still root their investment logic in socially embedded and culturally-specific national frames. For instance, to what extent do human rights and environmental justice, key norms that many EU states follow, shape the investment behavior of EU firms? Is the heavy involvement of Japanese firms in the infrastructure sector, which needs host government involvement, a product of Japan’s historically strong state? These hypotheses are open to future questions, such as the sectoral-specific characteristics of norms, the variety of norms in a nation, or the conditions under which socially embedded norms or national frames are unable to shape firm behavior.

Second, the paper’s framework brings out the agency of host countries. IPE often looks at the state-firm relations of sending countries and the alliances that host countries pursue in order to enact their goals. In contrast, this paper somewhat demonstrates the willful manipulation by host country actors. In my analysis, the host country leader and their elites will act strong in front of the Chinese actors. Future research can, therefore, further analyze to what extent this is a trend among host country elites. There is potential in enlarging this ‘presentation of the self’ approach, a classical sociological theory by Erving Goffman, in studying foreign capital. Will host country leaders change their behavior in front of EU firms and politicians, displaying human rights and environmental concerns? In front of US firms, will host country leaders pretend to accept the logic of the market and also forward American ideals of democracy (broadly interpreted)? Discerning the ‘different’ faces that these actors show one another has been done in studying international organizations or bureaucracies. However, I illustrate this trend in the context of firms and national leaders interacting and bargaining with each other, demonstrating how decisions at the micro-level shape the movement of capital above and beyond ‘objective’ indicators.

Third, the paper engages the literatures on global risk frames. As the paper shows that practices in China are brought outside by major Chinese firms, are global risk frames and the norms also outcomes of dominant national lines? The IPE of global governance has produced numerous indexes and frames in investment matters, such as the ‘ease of doing business’, ‘budget deficits’, and ‘public sector management’. Multinationals and states have differentially adapted these indicators in their activities. These indicators are products of the Breton Woods institutions, which were shaped by the West during the post-war period. Similarly, Social Development Goals and Good Governance, which are used by international organizations to score and assess the development pathways for the Global South, are products of international financial institutions. Other risk frames are possible results of nationally constructed norms. For the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, is the principle of non-interference, which is currently followed by states and firms in the region, an outcome of Mao Zedong’s support for communist revolutionary movements during the post-war era? There is potential research to show how current practices in IPE emerge from one or a combination of different national norms.

And finally, this paper challenges the IPE literatures on China’s globalization, engaging Chinese exceptionalism and those who argue against it. Both literatures were built on the assumptions of FDI studies, which, more broadly, follow Knightian assumptions of rational choice. In contrast, this article demonstrates a more sociological and dynamic approach by considering four sources of risk construction: the Chinese firm, the Chinese state, the host country, and the Chinese think tanks. This cultural approach is much more nuanced as it uncovers the historical relations of states and firms in China, the institutions of the Chinese state and think tanks, and the agency of host country actors. It is possible to probe the limits of this approach based on the type of firm and the changes within China. Chinese investments illustrate variation, particularly inflows in the West that comprise laundered money in real estate, smaller and non-major Chinese firms. Indeed, some works illustrate that these firms are trying to ‘escape’ the Chinese state’s control. Chinese firms also invest in places with strong institutions. These firms and their inflows may be outside the framework’s scope. Additionally, China’s approach to investing may be changing. In January 2021, China produced a white paper that favors ‘teaching’ global south states how to develop. This illustrates that the Chinese state and major firms may have realized the problem of investing in a strong leader. The degree to which this move will affect Chinese firms remains to be seen, and will need future research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Alvin Camba

Alvin Camba, an Assistant Professor at the Korbel School of International Studies at the University of Denver, and a research fellow at the Climate Policy Lab at Tufts University, studies Chinese investments in Southeast Asia. More information about his work can be found on his website (alvincamba.com).

Notes

1 Investment risk primarily refers to the host country rather than the project or sector.

2 This paper focuses on major firms alone, constituting the largest or wealthiest SOEs and private firms. As Lee argues (Citation2018), the mode of ownership seems to be a poor indicator of firm interest and activity.

3 Strength here refers to the capacity to protect the business environment, bypass institutional checks, and generate elite-mass support. These views emerged from interviewing executives or representatives of major Chinese firms. The views of these Chinese elites were corroborated by their Southeast Asian elite counterparts.

4 There is an argument in the FDI literature called ‘home country embeddedness’ arguing that familiarity with rent-driven institutions make emerging market multinational companies invest in risky environments. However, home country embeddedness collapses all forms of rent-seeking into a single category, assuming that the success of Chinese firms in dealing with corrupt provincial elites will result in higher chances of success in other corruption-driven environments.

5 Party schools socialize CCP cadre members, military officers, and business executives. Chinese party schools increasingly reflect a strong degree of coherence and, to some degree, major Chinese universities also follow the direction of the party-schools.

6 Many of China’s wealthiest individuals come from this class. However, a far large number of xiahai comprise mid-level CCP members who left their post for the private sector.

7 Firms are connected differently to various levels (CP, provincial, city, local, ministries) of the Chinese state.

8 Interviews with representatives of major Chinese firms in the Philippines, Indonesia, and Malaysia.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

11 SOE representative, Singapore, 07-25-2017.

12 Chua’s links with Chinese firms started in the 1990s when he began importing basic goods and machineries.

13 Arroyo’s Political Adviser, Manila, 08-21-2017.

14 Former PRC ambassador, Hong Kong, 09-04-2019.

15 Think tank analyst, Singapore, 07-14-2017.

16 FFCCI board member, Manila, 08-03-2017.

17 Ibid.

18 Former APPFI President and Chief Executive Officer, Quezon City, 10-22-2018.

19 Ibid.

20 Philippine Senator, Quezon City, 08-13-2017.

21 Philippine Congressman, Quezon City, 08-13-2017.

22 Chinese Manager, Hong Kong, 07-05-2019.

23 Ibid.

24 Chinese Vice President, Hong Kong, 07-02-2019.

25 For the interviewees, projects need to have a minimum level of economic viability.

26 Chinese Executive, Hong Kong, 07-01-2019.

27 These are different estimates provided by the Philippine National Police and the protest organizers (Conde Citation2008).

28 Former Undersecretary, Quezon City, 10-13-2017.

29 See Camba (Citation2021a) for the summary.

30 For a summary of the three projects, see Camba (Citation2018).

31 Makati, 08-14-2017.

32 Representative, Ministry of Commerce, Manila, 11-04-2018.

33 Davao City Broker, Davao City, 11-14-2019.

34 Former Philippine Senator, Manila, 10-27-2018.

35 Duterte’s Aide, Makati City, 01-18-2020.

36 Davao Businessman, Davao City, 11-18-2019.

37 Duterte’s Former Adviser, Manila, 09-15-2019.

38 Philippine Oligarch, Makati, 09-16-2019.

39 Former Presidential Spokesperson, Malacañang Palace, Manila, 09-19-2019.

40 Pro-China Philippine think tank, Director, Manila, multiple conversations between 2017 and 2018.

41 Representative, Manila, 11-10-2018.

42 Chinese Executive, Manila, 10-11-2019.

43 Chinese Consultant, Rizal, 09-17-2019.

44 Chinese Manager, Manila, 10-12-2019.

45 See Camba (Citation2020a) for a summary of the project.

46 Jerik Cruz, University Lecturer, Manila, 1-21-2020.

47 The American Enterprise Institute’s Chinese Global Investment Tracker places China Telecommunication’s investment at 860 million (see Camba, Citation2021c: 8).

48 Former NTC Official, Metro Manila, 1-13-2020.

49 Top law firm, lawyer, Makati, 1-14-2020.

50 These online gambling cronies refer to Duterte’s fraternity brothers. Oligarch, Makati, 09-20-2019.

51 Since the global pandemic, Chinese online gambling firms have decreased their investment. This revenue shortfall resulted in a greater desire by the Duterte government to extract taxes, leading to the divestment of some online gambling firms. This suggests a possible rift in the partnership between Duterte and the online gambling firms.

52 Oligarch, Makati, 09-21-2019.

53 Official, Manila, 11-04-2018.

54 UMNO representative, Kuala Lumpur, 03-05-2019.

55 Official, Kuala Lumpur, Chinese Embassy, 03-04-2019.

56 Manager, Kuantan, 03-08-2019.

57 MCKIP floor manager, Kuantan, 03-08-2019.

58 Malaysian Chinese Oligarch, Kuala Lumpur, 02-23-2020.

59 UMNO Representative, Ipoh, 06-20-2019.

60 Pangkatan Harapan Representative, Kuala Lumpur, 03-03-2020.

61 UMNO Representative, Ipoh, 06-20-2019.

62 Ministry of Trade and Industry, Kuala Lumpur, 02-28-2020.

63 All the other Chinese investments survived elite mobilizations. Mahathir’s government made these Chinese-Malaysian firms adjust their business practices.

64 Nahdlatul Ulama National Leader, Jakarta, 09-08-2018.

65 Partai Demokrasi Indonesia Perjuangan Parliamentarian, Jakarta, 10-23-2019.

66 Tsingshan Manager, Morowali, 04-25-2019.

67 Jokowi’s allies also supported all the other Chinese mining and industrial park investments.

68 Political broker, Morowali, 04-27-2019.

69 Ibid.

70 Member, Nickel Mining Association, Kendari, 11-27-2019.

71 Jakarta, 09-13-2019.

References

- Abb, P. (2015). China's Foreign Policy Think Tanks: Institutional evolution and changing roles. Journal of Contemporary China, 24(93), 531–553. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2014.953856

- Alden, C., & Hughes, C. R. (2009). Harmony and discord in China's Africa strategy: Some implications for foreign policy. The China Quarterly, 199, 563–584. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741009990105

- Bluhm, R., Dreher, A., Fuchs, A., Parks, B., Strange, A., & Tierney, M. (2018). Connective financing: Chinese infrastructure projects and the diffusion of economic activity in developing countries [Working Paper No. 64]. AidData at William and Mary College.

- Bräutigam, D. (2011). The Dragon's Gift: The real story of China in Africa. OUP.

- Buckley, P. J. (2020). China’s belt and road initiative: Changing the rules of globalization. Springer.

- Buckley, P. J., Clegg, L. J., Cross, A. R., Liu, X., Voss, H., & Zheng, P. (2007). The determinants of Chinese outward foreign direct investment. Journal of International Business Studies, 38(4), 499–518. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400277

- Camba, A. (2017). Inter-state relations and state capacity: The rise and fall of Chinese foreign direct investment in the Philippines. Palgrave Communications, 3(1), 1–41. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-017-0033-0

- Camba, A. (2018). The Philippines’ Chinese FDI boom: More politics than geopolitics. New Mandala (blog). January 30.

- Camba, A. (2020a). The Sino‐centric Capital export regime: State‐backed and Flexible Capital in the Philippines. Development and Change, 51(4), 970–998. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12604

- Camba, A. (2020b). Derailing development: China’s railway projects and financing coalitions in Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines [Working Paper 8]. Global Development Policy Centre. bu.edu/gdp/files/2020/02/WP8-Camba-Derailing-Development.pdf

- Camba, A. (2020c). Between economic and social exclusions: Chinese online gambling capital in the Philippines. Made in China Journal, 5(2), 209–217. https://doi.org/10.22459/MIC.05.02.2020.26

- Camba, A. (2021a). Sinews of politics: State Grid Corporation, investment coalitions, and embeddedness in the Philippines. Energy Strategy Reviews, 35, 100640. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esr.2021.100640

- Camba, A. (2021b). How Duterte strong-armed Chinese dam-builders but weakened Philippine institutions. China Local/Global Series. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Washington, D.C., June 15, 20121. Retrieved June 19, 2021, from 202106-Camba_Philippines.pdf (carnegieendowment.org).

- Camba, A. (2021c). The “strong leader” trap: The unintended consensuses of China's global investment strategy.” [Doctoral dissertation, The Johns Hopkins University]. Baltimore.

- Camba, A., & Li, H. (2020). Chinese workers and their “linguistic labour": Philippine online gambling and Zambian onsite casinos. China Perspectives, 2020(4), 39–47. https://doi.org/10.4000/chinaperspectives.11189

- Camba, A., & Magat, J. (2021). How do investors respond to territorial disputes? Evidence from the South China sea and implications on Philippines economic strategy. The Singapore Economic Review, 66 (01), 243–267. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0217590819500681

- Camba, A., Tritto, A., & Silaban, M. (2020). From the postwar era to intensified Chinese intervention: Variegated extractive regimes in the Philippines and Indonesia. The Extractive Industries and Society, 7(3), 1054–1065. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2020.07.008

- Chalmers, A. W., & Mocker, S. T. (2017). The end of exceptionalism? Explaining Chinese national oil companies’ overseas investments. Review of International Political Economy, 24(1), 119–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2016.1275743

- Conde, C. (2008). Thousands in Philippines call for Arroyo to resign. New York Times, February 29. Retrieved January 21, 2021, from https://www.nytimes.com/2008/02/29/world/asia/29iht-phils.1.10571127.html

- Cruz, J., Juliano, H. (2021). Assessing Duterte’s China projects. Asia Pacific Pathways of Progress Foundation. https://appfi.ph/publications/50-working-papers/2953-assessing-duterte-s-china-projects

- Dannreuther, C., & Lekhi, R. (2000). Globalization and the political economy of risk. Review of International Political Economy, 7(4), 574–594. https://doi.org/10.1080/096922900750034554

- De Castro, R. C. (2019). China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the Duterte Administration’s Appeasement Policy: Examining the connection between the two national strategies. East Asia, 36(3), 205–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12140-019-09315-9

- de Graaff, N. (2020). China Inc. goes global. Transnational and national networks of China’s globalizing business elite. Review of International Political Economy, 27(2), 208–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2019.1675741

- Duanmu, J. L. (2012). Firm heterogeneity and location choice of Chinese multinational enterprises (MNEs). Journal of World Business, 47(1), 64–72.

- Duanmu, J. L., & Urdinez, F. (2018). The dissuasive effect of US political influence on Chinese FDI during the “Going Global” policy era. Business and Politics, 20(1), 38–69. https://doi.org/10.1017/bap.2017.5

- Dickson, B. J. (2003). Red capitalists in China: The party, private entrepreneurs, and prospects for political change. Cambridge University Press.

- Elemia, C. (2016). De Lima denies Duterte drug matrix: 'It's garbage.' Rappler, August 25. Retrieved January 21, 2021, from, https://rappler.com/nation/de-lima-denies-duterte-drug-matrix-garbage

- Gallagher, K., & Porzecanski, R. (2010). The dragon in the room: China and the future of Latin American industrialization. Stanford university press.

- Gamboa, R. (2018). Take two for China. Philippine Star. 08 March. Retrieved January 21, 2021, from https://www.philstar.com/business/2018/03/08/1794474/take-two-china

- Goffman, E. (1978). The presentation of self in everyday life (p. 56). Harmondsworth.

- Gomez, E. T., & De Micheaux, E. L. (2017). Diversity of Southeast Asian capitalisms: Evolving state-business relations in Malaysia. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 47(5), 792–814. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2017.1322629

- Gotinga, J. (2019). Conclusion. Experts warn of spying risk in AFP deal with China-backed telco. Rappler, 11 November. Retrieved January 21, 2021, from https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/in-depth/244602-conclusion-experts-warn-spying-risk-military-contract-china-backed-telco

- Gotinga, J. C. (2020). Kaliwa Dam access road construction broke the law – Imee Marcos. Rappler. February 17. Retrieved January 21, 2021, from https://www.rappler.com/nation/252056-imee-marcos-says-kaliwa-dam-road-access-construction-broke-law

- Granovetter, M. (1985). Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology, 91(3), 481–510. https://doi.org/10.1086/228311

- Gu, J., Zhang, C., Vaz, A., & Mukwereza, L. (2016). Chinese state capitalism? Rethinking the role of the state and business in Chinese development cooperation in Africa. World Development, 81, 24–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.01.001

- Hinks, J. (2017). Duterte has brazenly reinstated 19 Police who murdered a Philippine mayor last year. Time. July, 17. Retrieved January 21, 2021, from https://time.com/4858028/rolando-espinosa-police-murder-philippines-duterte/

- Hopewell, K. (2015). Different paths to power: The rise of Brazil, India and China at the World Trade Organization. Review of International Political Economy, 22(2), 311–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2014.927387

- HRW. (2017). Philippine police kill another city mayor questions arise around reliability of police’s account of raid, killings. July 13, 2017. Retrieved June 17, 2021, from https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/07/31/philippine-police-kill-another-city-mayor#

- Huang, D., & Chen, C. (2016). Revolving out of the Party-State: The Xiahai entrepreneurs and circumscribing government power in China. Journal of Contemporary China, 25(97), 41–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2015.1060763

- Hung, H. F. (2020a). The periphery in the making of globalization: The China Lobby and the Reversal of Clinton’s China Trade Policy, 1993–1994. Review of International Political Economy, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2020.1749105

- Hung, H-f. (2020b). China and the Global South. In T. Fingar & J. Oi (Eds.), Fateful decisions: Choices that will shape China's future (pp. 247–271). Stanford University Press.

- Jensen, N. M. (2003). Democratic governance and multinational corporations: Political regimes and inflows of foreign direct investment. International Organization, 57(3), 587–616. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818303573040

- Kastner, S. L., & Pearson, M. M. (2021). Exploring the parameters of China’s economic influence. Studies in Comparative International Development, 56, 18–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-021-09318-9

- Knight, F. H. (1921). Risk, uncertainty and profit (Vol. 31). Houghton Mifflin.