Abstract

What are the consequences of the rise of foreign state-led investment for international politics? Existing research oscillates between a ‘geopolitical’ and a ‘commercial’ logic driving this type of investment and remains inconclusive about its wider international reverberations. In this paper, I suggest going beyond this dichotomy by analyzing its systemic consequences. To do so, I conceptually delineate a geoeconomic approach that emphasizes the globalized nature of foreign state investment. I argue that foreign state investment creates system-level patterns, which can be studied by observing similar sectoral and geographic investment behavior. I map this phenomenon globally for the first time, drawing on the largest dataset on foreign state investment. Empirically, I show how foreign state investment is highly concentrated in Europe, North America and East Asia, and is owned by a handful of dominant states. It is especially European geo-industrial clusters that represent the hotspots of such concentration. The findings also suggest that three global industries – energy production, high-tech manufacturing, and transportation and logistics – form the key areas for current and future state-led investment concentration. With these contributions, the paper illuminates the increasing presence of states as owners in the global political economy, and facilitates its study as a geoeconomic phenomenon.

Foreign state investment and international politics

In early 2020, the Norwegian Sovereign Wealth Fund (SWF) announced a record return on its global investments of an astonishing 20% for 2019. At that moment, it held more than $1.1 tn. in assets under management and owned about 1.5% of all globally listed stocks (CNBC, Citation2020). But Norway is not the only state owning and steering massive amounts of capital in the global economy. The largest outward FDI transaction ever coming out of China, as well as the largest inward FDI deal in India, have both been conducted by transnational state-owned enterprises (SOEs). A large number of SWFs from the Middle East and many other powerful transnational SOEs from Asia and Europe bring into clearer focus the fact that states have risen as major owners and investors in the global economy. States are today more than ever involved in acquiring foreign firms, setting up state-owned subsidiaries abroad, or engaging in portfolio investment in global financial markets. This development begs a crucial question for International Political Economy (IPE): what are the consequences for international politics if resource-rich states rise as large-scale owners and investors in the global economy? Some observers argue that this brings back geopolitical questions: the Chinese state-directed mega-project of a ‘Belt and Road Initiative’ (BRI) (Ferdinand, Citation2016) or the state-led Nord Stream 2 project strengthening Russia’s grip on European gas supply are often-cited examples of state capital internationalization with a geopolitical motive. State investment appears here as the projection of state power abroad, especially from authoritarian regimes (Carney, Citation2018).

Quite apart from such prominent cases however, recent research demonstrates that transnational state capitalFootnote1 is a much broader phenomenon than the focus on these attention-grabbing projects and their geopolitical aspects suggests (Haberly & Wójcik, Citation2017). Geopolitics play only a subordinate role when SWF investment from the Gulf states flows into the South European energy sector; or when foreign SOEs buy up large parts of British railway operations. These capital movements are not primarily geopolitical gambits, but rather strategies of states as owners to reap the financial rewards of a globalized economy. They can, however, also produce critical consequences for international politics: the case of British railways was soon politicized and portrayed as German, French, and Dutch SOEs competing to prey on a formerly state-owned sector in Britain (The Guardian, Citation2014). Similarly, the large-scale takeover of the agrochemical giant Syngenta by state-owned ChemChina has been discussed in the light of growing consolidation and harsher competition in the global seed business (OECD, 2018), provoking reactions ranging from the EU Commission scrutinizing the transaction (EC, Citation2017) to divestment demands by the US Federal Trade Commission (FTC, Citation2017).

These and other cases exemplify how the rise of foreign state investment can affect international politics in ways that often fly under the radar of scholarly attention. States engage, as owners as well as steerers of capital, in the pursuit of various goals such as returns on investment, technological dominance, or the acquisition of high-value assets. Classical approaches in the disciplines of International Relations (IR) and IPE have, however, so far lacked a compelling framework to capture this important development. As a consequence, analyses of foreign state investment tend to apply explanatory frameworks that oscillate between a geopolitical and a commercial logic. In many discussions, state-led investment forms are then either subordinated to – and an instrument for – the interests of states, who are key actors within the international system (Gilpin, Citation1987). Or they are primarily commercial actors that are not a threat to national security or the liberal order (Drezner, Citation2008; Schwartz, Citation2012). As a consequence, state-led foreign investment is either one among many geopolitical tools for projecting state power abroad (Braunstein, Citation2019), or its relevance for international politics is negligible (Kirshner, Citation2009). Both perspectives leave us with overly unilateral accounts that are either state-centric or that fail to notice the profoundly political nature of state capital. Yet, the above-described cases speak a different language: there is an immense variety of ways that states control and move enormous amounts of capital across the globe. By doing so, some states put themselves in powerful positions in the global political economy. How can IPE research then bring together this variety of forms of state investment with the question of its effects on international politics?

In this paper, I contribute two important building blocks for shedding light on this question. The first one is an analytical framework that conceptualizes the consequences of foreign state investment as a geoeconomic phenomenon (Roberts et al., Citation2019). This framework presents a means of capturing the engagement of states as owners in the cross-border pursuit for goals such as return on investment, technological catch-up and dominance, or the acquisition of high-value assets. It hence goes beyond the gridlocked discussions between a geopolitical and a commercial reading that impeded the systematic exploration of the geographical and sectoral patterns of foreign state-led investment, and its potential consequences for international politics. The increasing presence of states as owners in the global political economy, and the various forms states engage in cross-border investment, urge us to rethink and extend the ‘geopolitics versus commerce’-thinking to account for the ‘polymorphic’ (Alami & Dixon, Citation2020a) nature of contemporary foreign state investment.

Second, I suggest and illustrate an empirical strategy for excavating and mapping where state-led investment is concentrated in the global economy, through what I call geo-industrial clusters. Beyond headline-making great-power battles for technological and economic supremacy, foreign state-led investment is an empirically elusive phenomenon: different economic actors pursue different goals, with a variety of instruments and often go unnoticed on the stage of great power politics. When a case like the recent takeover battle between the German government and Chinese state-owned SGCC for an important power grid network finally makes it into the newspapers and causes high-level political reverberations (Stratmann, Citation2018), IPE often lacks a systematic understanding of the broader phenomenon at hand. I argue that we need to go beyond such agnosticism when it comes to the patterns of cross-border state-led investment; and instead develop analytical perspectives that allow us to study its extent on a global scale. This paper provides a first methodological and empirical step in this direction, so that IPE can better navigate through the complexities of foreign state investment.

The approach I explain in the following is of a quantitative and descriptive nature. This is a purposeful choice. Our understanding of the state as a transnational owner is still fairly limited; and only recently have researchers made progress in mapping and studying this important phenomenon on a global scale (Haberly & Wójcik, Citation2017). The clarification of which strategies states as owners employ in the global political economy (see Babic et al., Citation2020) leaves open the question of where this investment goes and what sorts of geographical and sectoral patterns this engagement creates. Beyond the mentioned headline-making cases, we lack robust descriptive insights that would allow us to build a comprehensive body of knowledge, within which we could engage in testing causal claims and conducting qualitative, case-based and comparative research. In this paper, I draw on the largest firm-level dataset of foreign state ownership, which allows me to precisely and comprehensively map the geo-industrial clusters states are invested in and to outline the global sectors and regions where states as owners are particularly concentrated. This empirical contribution reflects recent calls to move beyond ‘variables-based’ towards ‘pattern-based’ (Oatley, Citation2017) IPE research that helps us in uncovering and understanding global dynamics that are under-researched and poorly understood within the discipline.

The findings of the paper show that transnational state capital is a highly concentrated phenomenon: it is a handful of powerful states and attractive geo-industrial investment targets that represent its backbone. North America, East Asia, and Europe are the core geographical targets of foreign state investment. I also I identify three major industries – energy production, high-tech manufacturing, and transportation and logistics – that form the key sectors of this concentration. Together, these findings shed light on a hitherto under-researched, but pivotal, phenomenon of the contemporary global political economy; and help IPE research to better come to grips with the rise of the state as global owner and steerer of capital.

In the following, I first discuss the analytical problems of existing perspectives on foreign state investment and how a geoeconomic perspective can provide a workable alternative. Afterwards, I apply the delineated framework to the largest existing dataset on cross-border state ownership and excavate the main geo-industrial clusters where state capital is concentrated globally. Finally, I discuss the results in the light of recent developments in the global political economy and conclude by proposing avenues for further research that can build on the findings of this paper.

The geoeconomic dimension of foreign state investment

Rising foreign state investment and the geopolitical question

The emergence of transnational state capital is closely intertwined with the rise of neoliberal globalization since the 1980s. In a first phase that started in the early 1990s, multiple privatization waves significantly reduced direct state involvement and state ownership around the world, from post-communist Eastern European countries to Latin America (Megginson & Netter, Citation2001). In this phase, state ownership was widely regarded as an economic anachronism and was expected to be entirely superseded by such privatization efforts. Most of the privatized state-owned assets were located in ‘real’ national companies, whose activity was restricted to their domestic economies. This was the case for German and French ‘national champions’ as well as for industrial conglomerates in the former Soviet Union and Asia. In theory, new programmatic ideas like the Washington Consensus both demanded and predicted a massive withdrawal of states from direct state ownership in their domestic economies. However, as Musacchio and Lazzarini (Citation2014) show, while this withdrawal did happen, it can in many cases better be described as a transformation process. States modified their ownership arrangements with their SOEs, often without or by only slightly reducing their actual ownership and control of those firms. Thus, the great privatization waves of the 1990s were, at least for some large and emerging economies, rather a phase of modernization and flexibilization of existing state ownership structures.

This flexibilization and hybridization of state ownership laid the foundations for a second phase that began around the early 2000s. Emerging economies like China or Brazil used those arrangements to internationalize and globalize their (partly) state-owned vehicles (Nölke, Citation2014). Large SOEs, once the ultimate symbols of economic inertia, corruption, and public burden, increasingly became important global players that were backed by deep state pockets and domestic political support (Cuervo-Cazurra et al., Citation2014). SOEs grew steadily over the last decades in the global economy (Kwiatkowski & Augustynowicz, Citation2015). Firms like Gazprom or Petrobras became champions in their respective industries on a global scale during this period. Around 2007, the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) made SWFs visible as a second major type of globally active state-owned vehicles next to transnational SOEs. SWFs played a decisive role in saving drowning US financial institutions such as Citigroup or Merrill Lynch during the GFC (Helleiner & Lundblad, Citation2008, p. 66). SWFs also grew ever since in terms of both the size of their assets under management as well as their portfolio of high-profile targets, such as large US and European industrial multinationals or successful football clubs (SWFI, Citation2019). Hence, both SOEs and SWFs became central instruments in the rise of transnational state capital on a global scale.

The privatization waves inspired by neoliberal globalization therefore created a paradox: instead of entirely breaking the state’s grip on the economy, new types of state ownership and state-led internationalization emerged. These new types adapted to the demands of a globalized economy, for example by introducing modern corporate governance structures into SOEs (OECD, Citation2020). At the same time, this adaptation created the opportunity for state capital to successfully exploit investment opportunities in the global political economy. Examples like the Chinese State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) show how a nominal reduction and centralization of state ownership can in fact increase state control over vast capital resources (Li & Cheong, Citation2019, p. 50). Such examples illustrate how increasingly flexible state control over capital can be used by governments to transnationalize state investment, and thereby reap the benefits of a globalized economy.

This adaptation to the rules of a globalized economy soon created consequences for international politics. As long as state ownership and control were limited to domestic economies, their relevance for the international system was only indirect. As global owners, however, some powerful states with large natural or financial resources became able to directly move global markets through their investment decisions. The global rise of powerful SOEs provoked analyses that warned of their adverse effects on an ideal-type of global liberal capitalism (Bremmer, Citation2010). At the same time, SWFs came under increased scholarly scrutiny when they stepped in to prop up troubled US and European financial institutions during the GFC (Helleiner & Lundblad, Citation2008).

Based on this ability to move large amounts of capital globally, the discussion of the international political dimension of this phenomenon quickly moved to the question of whether vehicles such as SWFs are to be treated as geopolitical tools or not. Scholars argued both in favor of (Cohen, Citation2009) and against (Kirshner, Citation2009) a ‘classical’ geopolitical reading of the role of SWFs for international politics. This classical geopolitical reading can be summarized as the idea that SWFs (and other state-owned vehicles) represent strategic tools that allow the owning state to further its geopolitical goals through the ownership and control of enormous amounts of cross-border state capital. The counter-argument can be summarized as claiming that state-owned vehicles do not represent strategic tools but have to be considered as just another type of commercial market actor. Similar to SWFs, the (geo-) political question also dominated discussions about the global role of SOEs (Carney, Citation2018; Cuervo-Cazurra, Citation2018; Jones & Zou, Citation2017; Meckling et al., Citation2015).

Already early on, authors like Shih (Citation2009) identified the problematic dichotomy arising out of these discussions: state investment vehicles are in these debates either geopolitical tools or simple profit maximizers, i.e. commercial actors (Shih, Citation2009, p. 329). Studies in the wake of the GFC thus regularly confirmed and emphasized either the political or the commercial nature of transnational state capital. Only recently, studies on Chinese foreign investment (Jones & Zou, Citation2017) or Chinese oil elites (de Graaff & van Apeldoorn, Citation2017) presented nuanced assessments of the hybridity of (Chinese) foreign state-led investment. These studies show how a simple geopolitical or commercial reading of foreign state investment does not capture the underlying political dynamics which oscillate between both aspects; and which are often hard to balance for states and state elites when transnationalizing state capital. Despite these nuanced assessments, the geopolitical dichotomy still retains a strong influence not only on academic research, but also on the wider public perception of ‘state capitalism’ (see Alami & Dixon, Citation2020b).

This geopolitical dichotomy represents a key challenge for IPE research. If foreign state investment is not reducible to either of the two alternatives, and if research in the field wants to draw conclusions beyond case studies and anecdotal evidence, a systemic approach is necessary. The following framework attempts to go beyond this cul-de-sac by incorporating recent research in geoeconomics, which represents an alternative middle-way to the deadlocked geopolitical discussions about foreign state investment.

A geoeconomic alternative

The concept of geoeconomics recently experienced a revival in academic research (Blackwill & Harris, Citation2016; Gertz & Evers, Citation2020; Roberts et al., Citation2019). Different from the original usage of the term by Luttwak (Citation1990), contemporary research in IPE employs the term not simply to implicate a continuation of traditional state conflict through economic means. Rather, geoeconomics describes the increased ‘securitisation of economic policy and economisation of strategic policy’ (Wesley, Citation2016, p. 4; as cited in Roberts et al., Citation2019, p. 1). The fact that globalization created cross-border economic ties and opportunities gives states the possibility to weaponize and exploit those ties (Farrell & Newman, Citation2019). As Gertz and Evers (Citation2020, p. 119) point out, this possible weaponization dissolves the traditionally strict division between economic and security policy: coercion in the name of national security can and is increasingly implemented through economic networks; and the pursuit of economic goals has increasingly security-relevant implications.

The contemporary application of geoeconomics hence entails two important aspects. One is that globalization creates cross-border linkages that open up the possibility for actors to exploit economic and other networks which were not available in a less globally connected economy. The second aspect is that state power does not vanish in such a geoeconomic setting. On the contrary, state power seems to experience a revival through the exploitation of previously unavailable channels created by globalized networks (Crasnic et al., Citation2017). The phenomenon of transnational state capital is a prime example of how particular states capitalize on these opportunities by becoming large-scale global owners (Babic et al., Citation2017). Both of these essential geoeconomic aspects are consequently applicable to transnational state capital: states as owners are able to exploit investment opportunities within a globalized economy and create ownership ties across the globe (see, e.g. Haberly & Wójcik, Citation2017). Furthermore, this rise puts states also in potentially powerful positions within the global economy, as large global owners like China or Norway exemplify (see, e.g. Babic et al., Citation2020).

In this paper, I apply a modified version of such a geoeconomic approach to the question of foreign state investment. This modification concerns one assumption of contemporary geoeconomics research that is not uncritically transferrable to foreign state investment: in the mainstream geoeconomics literature, cross-border state interaction is seen as a projection of state power abroad (Gertz & Evers, Citation2020). Studies in the field tend to place economic coercion center stage, following from the dissolution of the strict distinction between economic and security policy. I argue that such an assumption is not applicable to foreign state investment without qualification. Sovereign investment follows in general rather an economic than a coercive rationale: large-scale takeovers are mainly motivated by the desire to gain a competitive advantage, be it in specific technologies or in other types of global assets (Cuervo-Cazurra et al., Citation2014). Research on sovereign investment vehicles also emphasizes that those vehicles mimic their private peers and adapt to rules of global markets to better reap their benefits (Clark et al., Citation2013). Moreover, the burgeoning literature on state financialization convincingly shows how states themselves transformed into shareholders and adapted respective tools and profit-driven goals (Wang, Citation2015). The modernization of state-owned investment vehicles hence introduced a market logic to the investment decisions of states as owners (Schwan et al., Citation2021, p. 5). This market orientation does at the same time not mean giving up on state power and control, but rather signals a transformation of state power under conditions of globalization and financialization (Wang, Citation2020). State power is hence not so much projected through economic means, but rather put to use in order to exploit transnational investment opportunities created by globalization. From this modified vantage point, state-led investment is a geoeconomic phenomenon, as state-owned capital is used to acquire – and in some cases to compete for – global investment targets.

What follows conceptually from such a geoeconomic perspective, if we seek to map the polymorphism of cross-border state investment? If states as owners are interested in acquiring profits or relevant assets outside their borders, and employ state-owned resources to do so, foreign state investment is not reducible to either geopolitics or purely commercial motives. Beyond motives, the consideration of the targets of state-led foreign investment needs to be more nuanced: it is not the destination states, as the geopolitical reading would have it, that we should focus our empirical attention on, but rather the industries, sectors, companies or regions, where state capital is directed to. This provides us both with a more fine-grained understanding of foreign state-led investment, as well as with a way of thinking beyond the geopolitical ‘state-to-state’ investment ties.

Such a geoconomic perspective rethinks, and goes in major ways beyond, the geopolitical dichotomy of foreign state investment sketched above. contrasts both approaches in important aspects.Footnote2

Table 1. Comparing the geopolitical and geoeconomic approaches to foreign state investment.

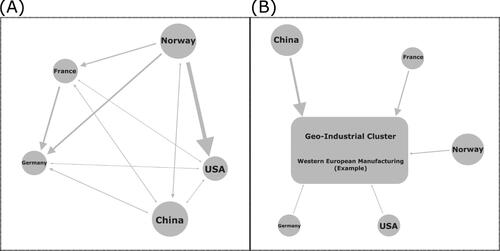

To summarize, a geopolitical approach would assume that foreign state investment is motivated by the desire to project state power abroad for goals like making others act in a state’s interest. This investment consequently targets other states in the global system, which the sending state seeks to coerce. Following from this, the space into which such investment flows is one that is populated by other states and hence inter-national. The nature of the potential political consequences (competition, conflict, cooperation, or otherwise) arising out of this is necessarily direct: states aim to project power into other states. In contrast, a geoeconomic approach understands the motivation of foreign state investment as being primarily rooted in economic motives. States as investors pursue goals like return on investment or the acquisition of high-value assets like foreign technologies. The targets of this investment are consequently not other states, but economic targets such as firms, which are located in specific industries and regions. The global political economy is from this perspective a trans-national space, consisting of the many networks and cross-border ties that economic actors create and that span different levels, from the locally owned SOE to the transnationally active SWF. States as owners move within this space and aim to exploit investment opportunities, in co-existence with other actors. Logically, potential conflict – or cooperation – arises mainly indirectly out of the interest for similar economic targets. visualizes both perspectives.

Figure 1. Illustration of the geopolitical (A) and geoeconomic (B) perspective. Each node is a state as owner, each tie represents total investment into another state (A) or cluster (B). Node size approximates total investment by a state, tie thickness approximates amount of the respective investment into a state (A) or cluster (B). (B) contains only states as owners (and not other actors) for representational reasons.

This comparison of the geopolitical and geoeconomic approaches does not imply that the geopolitical reading becomes irrelevant. Geopolitics do still play a role in cases where states clearly seek to project power cross-border through economic means, as for example Russia’s Gazprom illustrates (Abdelal, Citation2013). The developed framework is however more comprehensive as it, firstly, includes the large chunk of foreign state investment that puzzled IR and IPE research for now over a decade and that led to the described geopolitical dichotomy. It also, secondly,Footnote3 captures a larger variety of power resources that states as global owners possess via their investment. Instead of a narrow focus on either geostrategic and military means (like in the geopolitical view), or on commercial means (the ‘commercial’ view), the geoconomic perspective covers a variety of power resources, such as capturing global value chains, acquiring know-how, gaining access to emerging markets, or occupying nodal points in infrastructure networks, among others. The common denominator of all these power resources is cross-border state-led equity investment, which is the focus of this paper. The employed power resources will vary depending on the motivation of the state as owner employing them and the overall investment capacities of this specific state (see Section 4). Consequently, I argue that the delineated framework overcomes the geopolitical dichotomy and moves the discussion about how to understand and map foreign state investment in the global political economy forward.

Conceptualizing the geoeconomics of foreign state investment

Based on these considerations, I conceptualize the two main components of the geoeconomic phenomenon of foreign state investment as follows. First, the investing state is conceptualized as the sum of state-owned entities investing in other firms outside their own borders and hence creating ownership ties to these targets – regardless of the type of investment vehicle. SWFs, for example, create on average lower ownership stakes in foreign companies, while SOEs tend to acquire majority-owned companies cross-border. In both cases, an ownership tie is created. This means that measuring foreign state investment through ownership ties is a viable way of quantitatively studying the phenomenon at hand (Garcia-Bernardo et al., Citation2017; Haberly & Wójcik, Citation2017).

Aggregating these ownership ties at the national level gives us an idea of the outward strategic orientation of a state as owner – i.e. whether it invests predominantly through portfolio or majority-investment. The former indicates an interest in return on investment, while the latter indicates a strategic interest in owning and controlling the acquired asset (see Babic et al., Citation2020, p. 443). By aggregating the ties created by different state-owned entities at the national level and assigning a strategic profile to the investing state, I integrate the multidimensionality of state investment into a workable strategic orientation of the respective state. Recent research supports this conceptualization of pulling together different outward state investment types at the state level in order to explain its international political ramifications (Carney, Citation2018).

Second, the investment targets are conceptualized as geo-industrial clusters in the global political economy. They are a combination of geographical information on world regions from the UN geoscheme and sectoral information from the ORBIS database (see the next section). What does this mean? As discussed above, the primary targets of foreign state investment are usually firms. To map foreign state-led investment as investment of states into firms would however not be a meaningful way of aggregating this investment. Excavating patterns on a global scale requires a larger unit of analysis in order to provide a comprehensible global map of foreign state-led investment. Using states as targets instead of firms would however throw the analysis back to the above-discussed state-to-state ties and hence reproduce state-centrism in what are transnational dynamics (see Henderson et al., Citation2002). In line with the geoeconomic conceptualization of state investment in the previous section, it is hence reasonable to choose a unit of analysis that is broad enough to facilitate a global analysis, but also specific enough to provide meaningful sectoral and industrial information.

The heuristic of geo-industrial clusters presents a tool that meets these demands. From the considerable work within the Global Production Networks (GPN) literature,Footnote4 we know that today’s global economy is mainly structured across, and no longer exclusively within national borders (Coe & Yeung, Citation2015; Dicken et al., Citation2001; Henderson et al., Citation2002). This makes a focus on geographical regions useful, as they allow us to capture cross-border dynamics that are otherwise ignored in state-centric accounts. Furthermore, the GPN literature has established that sectors and industries are crucial for understanding corporate behavior, since ‘similar technologies, products and market constraints are likely to lead to similar ways of creating competitive advantage and thus broadly similar GPN architecture’ (Henderson et al., Citation2002, p. 454). Studies in this vein have consequently accumulated significant evidence of the cross-border, regionalized nature of industrial and sectoral GPN organization (Coe et al., Citation2008, p. 283). Despite the non-state-centric nature of these studies, states play an important role in these GPNs: next to regulating them, states also importantly act as investors, producers, and owners of lead firms within cross-border production networks (Babic et al., Citation2020; Horner, Citation2017; Lim, Citation2018). These GPN arguments are also reflected in the geoeconomic behavior of states as owners, for example when Chinese state-led investment into Germany and Austria targets not one specific firm, but rather sectors and industries relevant for its ‘Made in China 2025’ strategy (Jungbluth, Citation2018).

This conceptualization of geo-industrial clusters makes it possible to meaningfully aggregate foreign state investment, and to estimate where a concentration of this investment is taking place. At the same time, this analytical choice does not imply that other means of aggregating state investment are ‘wrong’ or misleading. Rather, this choice is deduced from the conceptual considerations above, and hence represents one way of aggregating and presenting the underlying data. Section 4 also provides a breakdown of the data at the sectoral and state level, which I then use to create geo-industrial clusters. The clustering hence represents a heuristic tool, which allows for a comprehensive first mapping of the global reach of state-led foreign investment. By focusing on the issue of investment concentration, this analysis lays the groundwork for studies that are interested in how state capital behaves in the global political economy. For instance, investment concentration could indicate geoeconomic competition between states as owners, or between these owners and other actors such as host governments. Whether such dynamics play a role in the formed clusters, and beyond, needs to be established on the basis of further research such as case-based and quantitative studies building on the insights generated here. Such an approach speaks to recent efforts to promote better ‘pattern-based’ research in IPE that engages in large-scale, data-driven work to better grasp emerging phenomena in the global political economy (Oatley, Citation2019).

Data and methodological considerationsFootnote5

In order to uncover the main sites of state capital investment and concentration, I employ the largest existing dataset on state ownership constructed from raw data from the comprehensive Bureau van Dijk’s ORBIS database. This dataset consists of a snapshot of initially over one million ownership relations, in which states or state entities appear as owners. Since I am interested in the cases of foreign state investment, I reduce the dataset to those relations that represent transnational cases. I apply a threshold of at least $10 mn. in operating revenue of the owned firm in order to filter out the main relevant targets of foreign state investment and to increase data quality. I then use this operating revenue of the target firm as firm size indicator and weigh the ownership tie through this indicator. The resulting 21.389 (weighted) ties represent the sample used for this study. Using ownership ties that build on fine-grained, firm-level data instead of data on investment by specific vehicles has the main advantage of larger coverage (see Haberly & Wójcik, Citation2017).

In the following, I distinguish between different ownership levels the ties represent. Following Babic et al. (Citation2020), I conceptualize investment under 10% of a firm’s ownership stakes as non-controlling portfolio investment. Stakes that cross the 50.01% (majority ownership) threshold, I conceptualize as controlling. This differentiation is relevant in the following analysis, where I estimate the comparability of investment stakes within a cluster through the ratio between both forms of investment. If a state’s outwards investment is predominantly concentrated in majority ownership stakes, I understand this as, on average, reflecting a controlling interest of this state. Portfolio investment on the other hand reflects, on average, a financial interest in returns on investment. Aggregating the different ownership ties at the state level enables me to describe which strategy a state as owner tends towards. Comparability and equality between the invested states is therefore set to be higher in a cluster where the ratio of majority-to-portfolio stakes is higher than in another cluster, since the invested states display a higher degree of control than with portfolio investment. In other words, a higher ratio indicates a more strategic nature of the investment concentrated in the respective cluster.

For the geo-industrial clusters, I use the M49 standard from the United Nations geoscheme (UNSD, Citation2019) to code the data for different geographical regions. I analyze in total 14 different regions for foreign state capital inflows (). For the sectoral analysis, I use the industry classification NACE-codes provided by the ORBIS database itself, which results in 21 different sectors (). By combining industrial and geographical information, I construct the geo-industrial clusters. Whether or not a cluster represents a meaningful concentration of state capital depends on the following factors:

Table 2. Top 10 sectors of total transnational state capital.

The general investment capability and size of the invested states as owners.

The overall relevance of the industry as a target of state investment.

The overall investment into this specific cluster and hence its relevance for foreign state investment.

The comparability of investment stakes (i.e., if there is large or small inequality between the investors based on the size of their investment).

The ratio of controlling to portfolio investment as an indicator of the degree to which states are invested strategically in the geo-industrial cluster.

I apply these factors in the analysis through different thresholds and measurements. Factor (a) is applied by focusing the analysis on the top 20 states as owners. Not all states possess the same ability to invest state capital around the world. Transnational state capital is in fact a highly concentrated phenomenon: the top 20 owners own more than 90% of the total global amount. The Gini coefficient for the whole distribution is very high (0.91), whereas it decreases considerably for the top 20 states (0.49). It is hence not expedient for the analysis to take into account all the states from the original sample (in total 159): I would compare extremely large with extremely small owners. I consider the top 20 states as owning comparable amounts of foreign state capital (at least 1% of the total) and hence being on par as global investors. The range of the top 20 states is 19,9 percentage points, with China owning 20.96% and South Korea owning 1.06%, of total transnational state capital. The mean share of the top 20 is 4.6% and the standard deviation is 5.2 (interquartile range is 3.5).

Regarding (b), a similar logic applies to the destinations of state capital: some geographical areas are receiving such low levels of state investment (for example Central Asia or Northern Africa) that geoeconomic claims about these regions are hardly sustainable on the basis of the data. This does not imply that those regions are not relevant for geoeconomic analyses – in fact some of them are extremely relevant in contemporary international politics – but that they are not crucial ‘hotspots’ for foreign state investment. Since this is the focus of this paper, I exclude the regions where the total amount of transnational state capital is less than 1% of the total.

Furthermore, the invested sectors also display a high degree of inequality: most transnational state capital is invested in sectors like manufacturing, wholesale and retail trade, financial and insurance activities or the energy sector in general. 98% of the total investment by the top 20 owners is in fact concentrated in ten sectors. Sectors like education and human health are marginally present in this regard. I therefore focus the analysis on those ten sectors (with at least 1% of global state investment) which are by far the main targets of transnationally invested state capital.

Regarding (c), I understand clusters as relevant for this study if they entail at least 10% of the total investment in the relevant sector. This means that if a geo-industrial cluster receives less than 10% of the sector’s total investment (across all geographical areas), I do not include it in the analysis. This focuses the analysis further to 31 clusters in total; and allows me to carve out the core patterns on a global scale.

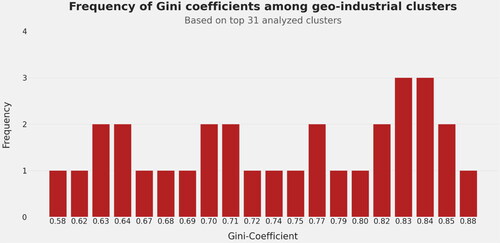

Factors (d) and (e) require different measures for estimating the degree of concentration and hence geoeconomic relevance. For (d), I choose the Gini-coefficient of each cluster as a measurement of the inequality between the invested states. This allows us to see, whether a cluster is relatively (un)equal compared to another. Of the 31 top clusters, the lowest Gini score is 0.58, and the highest 0.88 (the mean is 0.75). I conceptualize a high Gini-coefficient as being higher than the second tertile; whereas a low coefficient is lower than the first tertile. This means that a coefficient below 0.7 would be considered a rather low score for one of the clusters, whereas a coefficient beyond 0.82 would be considered high. In the following analysis, I analyze the clusters which fall within the first two tertiles, and hence on the most concentrated ones ().

Figure 2. The range and frequency of the Gini-coefficients of the top 31 clusters analyzed in this paper.

The control-portfolio ratio (e) serves as a proxy for the degree of control states as owners exhibit within this cluster. The lower this ratio, the more non-controlling foreign investment flows into the cluster. A higher ratio then proxies a situation in which states are invested in target firms with a controlling interest, which increases the geoeconomic relevance of this cluster. For the analysis, I consequently exclude all ratios below 1, which means that I keep those clusters where the value of controlling investment exceeds the value of portfolio investment.

With these measurement provisions, I am able carve out patterns of state investment that display a high prevalence of strategic behavior and thus indicate geoeconomic relevance. I first analyze and describe the aggregated data on the geographical and sectoral level separately. After this, I construct geo-industrial clusters by combining the geographical and sectoral data and assess and discuss the main geoeconomic dynamics within these clusters.

Analysis

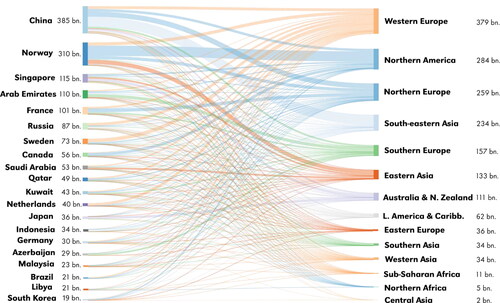

Aggregating the total numbers of transnational state investment per geographical region as well as sector, we get the distributions displayed in and .

Figure 3. Top 20 owners and their investment of transnational state capital in different regions. The left numbers are the total investment by each state, the right the total inflows in each region (in US Dollars). The node size reflects outflows (states) and inflows (regions). The color of the edges reflects the destination (region) of the investment.

Europe, taken together, receives almost half of all transnational state investment. Asia (in total) and Northern America follow with ca. 25% and 16.3%, respectively. The remaining investment is scattered across the globe and compared to the total amount, fairly low. This distribution of state capital inflows mirrors the general geographical distribution of FDI flows with Europe, Asia and Northern America receiving the lionshare (UNCTAD, Citation2017, p. 10). This increases the convergent validity of the measurement of state capital applied in this paper.

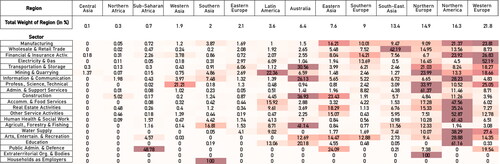

While this overview already reveals interesting overall patterns, the first analytical step consists in identifying the geo-industrial clusters by combining both regional and sectoral data in .

Figure 4. Concentration of transnational state capital in different geo-industrial clusters, in percent. The percentages are to be read row-wise. Darker color indicates a higher percentage of absolute investment in the respective cluster. Each cell represents one geo-industrial cluster.

The resulting patterns reveal the 31 core geo-industrial clusters.Footnote6 After applying the steps (a)–(e) described in Section 3, we are left with twelve clusters in five geographical areas that meet the specifications. In the following, I analyze seven of those twelveFootnote7 clusters closer by examining their internal structure and relevant investment ties. This discussion is aimed at illustrating the approach, giving an overview of state capital concentration, and delineating the firm-level geoeconomic dynamics of foreign state investment. I limit myself here to the most relevant of these clusters for illustration purposes. I proceed from the geographical region with the smallest (Southern Europe) to the one with the largest (Western Europe) total investment.

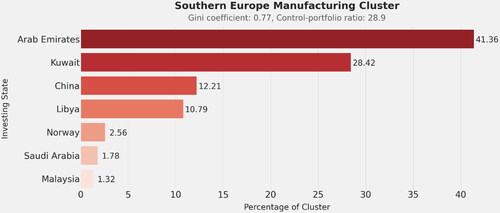

Southern Europe is the first heavily invested geographical area (9% of total foreign state investment), and shaped by investments from the Arab Emirates, France, Kuwait, Azerbaijan and Libya. In the manufacturing cluster, the Arab Emirates dominate with more than 41% of the total investment in the cluster, with full ownership of subsidiaries of industrial heavyweights like Borealis AG or oil firm CEPSA (). The strong position of Kuwait stems from its oil-related majority stakes in Italian firms and Kuwait Petroleum, which has been based in Italy since the 1980s. Chinese investment covers a number of countries (Italy, Greece, Serbia, Spain) and firms, from Pirelli to Syngenta subsidiaries. The prevailing type of ownership in this cluster is majority or full ownership as all the mentioned examples and the ratio (28.9) show. This indicates a high strategic relevance for states invested in the manufacturing cluster. The control of European multinationals in the energy sector is an attractive target for states that themselves rely on oil production and export (like the Emirates or Kuwait), and which can use the technological and operational know-how of multinationals like CEPSA.

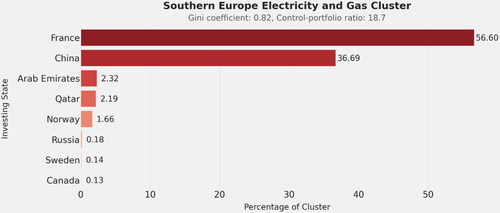

While the second relevant Southern European cluster displays high inequality, a remarkable point is the strong position of both France and China (). Here again Chinese investment is controlling, and China owns several subsidiaries of Portuguese EDP, while France is engaged in Edison (Italy), among others. Edison is a full subsidiary of French energy giant EDF and operates across Europe, the Middle East and Africa. China’s controlling stake in one of Europe’s largest electricity producers and leaders in renewable energies, as well as Portugal’s largest listed company, can be described as strategic. In 2019, the Chinese SOE Three Gorges tried to gain full control of EDP by offering €9 bn to remove a cap on voting rights, which was successfully opposed by other shareholders. Despite this defeat, the Chinese SOE aims to remain a ‘long-term strategic investor’ (Wise, Citation2019) in EDP and the Southern European energy market. This reflects attempts by China to diversify its energy consumption profile, for which it seeks know-how and assets that facilitate the transformation of the largest global economy in the upcoming energy transition. This cluster hence presents strong potential for geoeconomic competition for the control of European energy supply as well as for leading renewables technology.

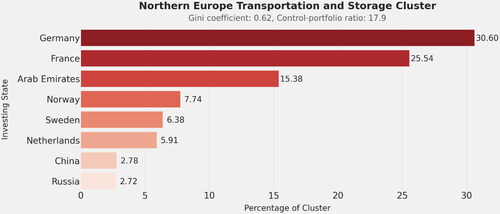

Northern Europe is mainly shaped by inflows into the UK and its associated jurisdictions like Guernsey and Jersey that attract over 80% of the total investment into the geographical area (). While a substantial part of this inflow is driven by the special role of the UK as an offshore financial center (Garcia-Bernardo et al., Citation2017), we can also identify ‘real’ investment ties in sectors like transport and logistics. These ties are mainly established by German and French transportation firms, a large number of which are actual public transport companies. Germany, for example, holds a 50%-stake in the London Overground Rail Operations and fully owns the UK-wide train operating company XC Trains Limited. Further subsidiaries of Deutsche Bahn and its logistics branch Schenker AG are located all across Northern Europe, beyond the UK (for example in Sweden). This reflects a strategic interest of Deutsche Bahn to transform from a ‘national’ to an ‘international’ (or at least European) logistics champion (Berlich et al., Citation2017). French state-owned La Poste/GeoPost owns subsidiaries of DPD across the UK and other European states, as well as it owns London United Busways and other transport services in major UK cities through Transdev. For La Poste, France’s largest employer, its sheer size and control of major subsidiaries in the logistics branch facilitate the capture of assets and commercial expansion similar to Deutsche Bahn.

The prevalence of majority ownership in this cluster, the relatively low Gini-coefficient and the described strong interest of both the French and German state in acquiring transportation and logistics firms, make this cluster strategically relevant. Extending the argument, it is also possible to take into account the Arab Emirates’ strong interest in British container terminals, ferry and port services (such as P&O Ferries) that are part of the state’s larger strategy to acquire and hold major transportation nodes and hubs of global supply chains. In sum, the cluster reveals important geoeconomic characteristics in a vital sector.

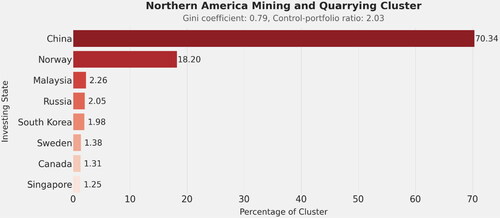

Northern America represents primarily a major target for portfolio investment into large US multinationals for SWF-owners like Norway and other sovereign portfolio investors. The Mining and Quarrying cluster deviates most strongly from this general trend by having a higher control-portfolio ratio (2.03) and being dominated by a single investor (China) (). This dominance is also expressed in the relatively high Gini-coefficient. Interestingly enough, these Chinese investment ties are focused on one country (Canada) and are mostly majority stakes. This reflects a strong interest of Chinese oil SOEs in their Canadian subsidiaries or Chinese-acquired Canadian firms like oil firm Nexen Inc. Canada is one of the largest oil producers in the world and represents a strategic target for Chinese SOEs. The Nexen acquisition in 2013 was the largest Chinese outwards investment at the time and gave its state-owned CNOOC control over crucial offshore production in the North Sea, Gulf of Mexico, and Africa, amongst others (Rocha, Citation2013). Again, the Chinese bid to profit from the resources and technological know-how of oil multinationals is a driving force of this investment: for the first time, CNOOC acquired a ‘global-scale crude oil domain’ (Lim, Citation2018, p. 7), reflecting the asset-capturing motivation of much Chinese foreign state-led investment. Beyond this, the cluster could also be a future site of geoeconomic clashes between the US, that receives over 90% of Canadian oil production, and the Chinese interest.

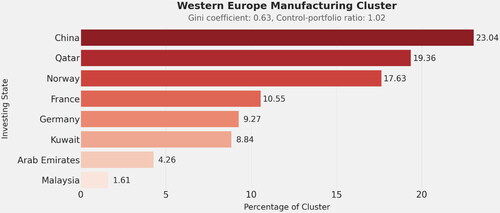

Western Europe is the most attractive geographical investment target for transnational state capital, not least due to the prevalence of large world-leading engineering and industrial firms. Manufacturing represents the largest cluster in Western Europe (). With a relatively low Gini-coefficient and a control-portfolio ratio beyond one, it is particularly interesting from a geoeconomic standpoint. China, as the largest owner, has some of its most relevant foreign companies located here: the aforementioned Syngenta, German manufacturer KraussMaffei, several Pirelli-subsidiaries and Austrian aerospace manufacturer FACC. This reflects the strategic selectivity of its Made in China 2025 industrial strategy, that aims at acquiring assets in ten leading sectors (Jungbluth, Citation2018). The Qatari investment is also large but consists of a much lower number of total ties and is also entirely located in non-controlling investment stakes, such as its shares in Volkswagen or Siemens. Similarly, but with a larger total number of investments, Norway is mainly engaged in large German, Swiss and French listed firms. The Gulf and Norwegian investment can be seen as driven by portfolio diversification; as well as by long-standing relations between ‘patient’ Gulf investment and German industrial capital. The prevalence of Chinese state ownership increases the likelihood of political backlash, as we can already see in the intensified political debates in Germany on tightened investment screening measures (Stompfe, Citation2020).

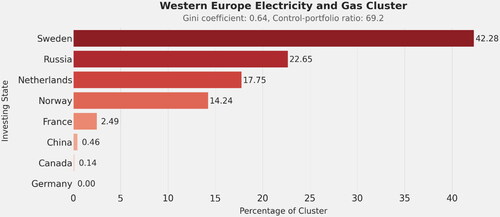

The Western European Electricity and Gas cluster is shaped by Swedish Vattenfall and Russian gas-driven expansion in Europe (). Both cases are quite specific: for Vattenfall, it is mainly its position in the German and Dutch energy markets that grants Sweden a dominant position in this cluster. In the Russian case, the Gazprom subsidiary Wingas controls a large part (around 20%) of the German gas market. Furthermore, some of the few wholly-owned Norwegian foreign companies can be found in this cluster, such as Statkraft – which is also involved in energy trading and is based in Germany. The geostrategic importance of the European gas market for Russian interest has already been analyzed extensively (Goldthau & Sitter, Citation2020). The cluster, which also displays a high control-portfolio ratio, exemplifies this high geoeconomic relevance not only for the German, but also European energy market.

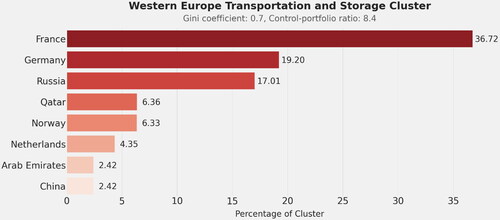

The last analyzed cluster reflects again the geoeconomic patterns we saw in the case of the UK: German and French transportation and logistics firms compete all throughout Europe, mostly by establishing cross-border subsidiaries of their national champions (Deutsche Bahn/Schenker and DPD or La Poste/GeoPost) (). An additional aspect that did not appear in the British case is the presence of the Russian state, largely due to the acquisition of former PSA (France)-owned logistics multinational Gefco. This takeover made Russia a central player in the European logistics market, which, in combination with the Gazprom expansion, grants it an increasingly structural role in the EU single market. The high presence of French and German transportation firms reflects also the ambitions of their respective states to re-create ‘national champions’ under conditions of globalization. Those states already own highly advanced and competitive transportation and logistic firms (such as Deutsche Bahn), that are able to profit from securing a pivotal position in a global logistics market that forms the backbone of present and future global value and supply chains (Memedovic et al., Citation2008). The control of these logistic networks is an essential area for global geoeconomic cooperation and competition.Footnote8

Discussion

The conducted analysis helps us to shed light on the global extent and dynamics of foreign state investment. I first delineate the general results from the analysis and subsequently discuss more specific findings and their implication for further research.

As demonstrated, the majority of large-scale, globally relevant investment is flowing into the substantial core of the global economy (Northern America, Europe and Eastern/South-Eastern Asia). However, this does not imply that the senders of these investments are restricted to this core. The first general result of this paper is therefore the identification and mapping of the many states as owners outside Europe and Northern America that, equally powerfully, pursue different strategies within global capitalism. In many cases they are, in fact, owners that are more globalized than their European and American counterparts: Middle Eastern states such as Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, the Arab Emirates, and Qatar show a wide-ranging and diversified ownership profile that covers most of the analyzed clusters. Large European owners like France focus more on their immediate geographical area, where national champions control almost whole sectors. This finding can serve as a building block for a better understanding of the variegated nature of transnational state investment and ‘state capitalism’ in general: states as owners do pursue different and often diverging goals, but at the same time create geoeconomically relevant patterns that can be detected by looking at specific geo-industrial areas.

The second major empirical finding of this paper is that Europe plays an exceptional role as a site of concentration of state capital. While other areas like Northern America or Asia receive similar total amounts of foreign state investment, the investment into European clusters leads to higher levels of concentration and thus relevance. This can be seen both in the generally high control-portfolio ratios in European geographical areas (ranging from 2.4 in Northern Europe to 13.7 in Southern Europe) as well as in their relatively low Gini-coefficients (from 0.51 in Western Europe to 0.68 everywhere else) ().

Table 3. Control-portfolio ratios and Gini coefficients for all geographical areas. Sorted descending by total state investment.

Europe is an exceptional target for foreign state investment because it combines both factors relevant for strategic concentration. While other areas like Northern America are also high-volume targets, the type of investment here is primarily portfolio and thus less strategic. Other areas however, like South-East Asia, with high volumes of such strategic investment do not display high levels of comparability (Gini-coefficients are quite high here). Finally, areas that are overall close to the European parameters, like Australia and New Zealand, do not show the same degrees of strategic investment and equality within the respective clusters. In sum, Europe is the core site for (strategic) foreign state investment. The analysis of the different clusters demonstrates that this is not only the case from an aggregated perspective, but also at the geo-industrial level. These findings shed light on current policy-discussions about stricter foreign investment regulation within the EU. Besides a dozen of member states, the European Commission itself introduced a far-reaching investment screening coordination mechanism in 2020, that is especially aimed at constraining foreign state-owned enterprises interested in taking over European companies. The above analysis shows, for the first time, where and how states as owners enter Europe in the search for investment opportunities. By focusing on geo-industrial clusters rather than on the state level, these diverging trends within Europe become clear. Better understanding the mechanisms of these dynamics should be a main priority for IPE and European Studies.

The more specific findings show that three global industries are key to understanding state-led foreign investment. The first is a ‘classic’ site of state ownership and state control in the global economy, namely large oil and energy multinationals. The described clusters include assets and technology for oil (Northern America), gas (Western Europe), as well as renewable (Southern Europe) energy sources. This finding is in line with the strong presence of state-owned firms among the top global energy producers. The finding reflects this standing and expands our knowledge of this phenomenon. A reliable energy supply will remain a vital priority for states in the coming global energy transition; and owning and controlling both global energy production as well as cutting-edge technology of this production is an integral part of this strategic aspect of foreign state investment.

The second relevant industry is transportation and logistics. Transportation industries in Northern and Western Europe represent geoeconomic opportunity structures for European states that have a history of state-owned national champions in the sector and managed to retain (some) of this state ownership despite the privatization waves of the last decades. Besides the already discussed railway business, transportation firms developed a comprehensive global strategy within the e-commerce business, where companies like French state-owned GeoPost acquired already over 840 international hubs in 23 countries with the focus on Europe as of 2018 (GeoPost, Citation2018). The stated strategic goal of GeoPost is thereby an ‘active policy of acquisitions in the express parcels market’, especially in emerging economies (GeoPost, Citation2018). Logistics are also a major cooperation and competition ground in a world in which the control of global value chains is crucially dependent on the logistical infrastructure enabling them (see, e.g. Khalili, Citation2020). The described role of the Emirates-owned P&O Ferries in the Northern European cluster reflects this type of geoeconomic relevance. Its mother company, DP World, has been a vital asset in the foreign policy ambition of its owner, the Arab Emirates (Borchert, Citation2019, p. 42). The control of key hubs and nodes in global logistics networks through state ownership can provide even ‘small’ states with high degrees of control and leverage in a geostrategic sense.

The third main industry where we can identify relevant strategic concentration is manufacturing in the broadest sense. We have seen that this can relate to engineering in the energy industry as in Southern Europe, but also to globally leading manufacturing firms as in the Western European case. It is especially important for China, whose transition from a global manufacturing center to a knowledge economy requires not only domestic scientific hubs and R&D upscaling, but also leading global expertise on cutting-edge industrial technologies, from semiconductors to bioengineering. This expertise and know-how are often found in European top companies and world-leading niche SMEs. The Chinese quest for foreign technology is thereby not only reducible to espionage, as often claimed, but extends to a state-led acquisition strategy of critical global assets and technologies (Hannas & Tatlow, Citation2020). Western Europe, especially Germany, is a major target of these efforts. While a direct geoeconomic rival for those targets is not visible, the adverse reactions from German and European policy-makers, and in some cases even industry associations, to Chinese takeovers make this a central area of future geoeconomic disputes caused by foreign state investment.

Conclusion

In public debates, states and markets are often treated as separate entities with their own working logics. In cases where this separation becomes obviously blurred – for example by states rising as economic owners – common explanations often nevertheless stick to these working logics. States that engage in foreign investment are hence under the general suspicion of exporting (geo)political ambitions via economic means. But, as this paper argues, both the geopolitical hypothesis as well as its counterpart (that foreign state investment is only a commercial phenomenon) come with different conceptual and empirical problems that are at odds with the demonstrated dynamics of foreign state investment. In this paper, I proposed an alternative that takes the polymorphism of foreign state investment seriously, but at the same time opens up conceptual and empirical avenues to a better understanding and mapping of the state as global owner.

The paper then provides a concrete body of findings that can help and guide future research into the dynamics of foreign state investment. First, the conceptual contribution of this paper will hopefully motivate further research into one of the fundamental topics for international politics in the next decade, which are the geoeconomic implications of the rise of states as owners. States play a major role in this context, also and maybe primarily as owners and steerers of capital. Some effects of this rise are already tangible, such as the protectionist reactions of the EU vis-à-vis the increased presence of state-owned entities in Europe. As I argued, these dynamics can hardly be explained from a geopolitical standpoint, but require a conceptual consideration of both the commercial and political aspects of foreign state investment. The conceptual contribution of this paper fills this gap and can help to further scrutinize the role of foreign state investment in a geoeconomic world.

Second, the empirical contribution of this paper enables us to see and map, where states as owners are prone to invest; and where this investment is especially concentrated. By uncovering global patterns of foreign state investment, the paper provides a rich repertoire of insights and possibilities for further research into better understanding the particular dynamics of these investment flows. Many clues from the financial press or other sources about such dynamics over the last years were treated as anecdotal at best. While those glimpses of geoeconomic dynamics between states as investors and other actors increased over time, IPE has for a long time either ignored them, or stuck to conventional explanations of state-market dynamics. Only recently, large-scale, pattern-based analyses have shed some light on those dynamics. The empirical findings of this paper add another important building block and provide concrete evidence of where to start investigating this phenomenon further.

It is clear that a thorough understanding of how these dynamics play out requires additional techniques and perspectives which this paper does not cover, such as in-depth qualitative inquiry and rigorous hypothesis-testing. Three possible next steps are, first, to clearly outline and classify the vast spectrum of motivations and reasons of states to transnationalize their investment, ranging from attempts to avoid Dutch disease (Norway) to aspirations to become the world-leading knowledge economy in the next decade (China). Second, scholars could engage in analyzing why state-led investment tends to be invested in specific areas and sectors more than in others. The strong presence of foreign state ownership in transportation and logistics industries around the world could, for example, indicate a strategic capture of important nodes of global capitalism and thus the ‘infrastructure’ of global value chains. We still lack a good understanding of the extent of this phenomenon and what it could possibly mean for the future of global material and financial infrastructures under (economic) state control. Third, studies could scrutinize the notion that state-led investment leads to geoeconomic competition – or cooperation – between the invested states, private actors, and host governments. Some of the more anecdotal evidence this paper touched upon indicates that specific geo-industrial clusters, and specific states as owners, are more prone to such dynamics than others. These indications could be followed up in more case-based investigations of the phenomenon at hand.

Based on a wealth of data on cross-border state ownership, this paper for the first time uncovers, where these and further important research efforts can be directed to; and which methodological instruments can help in uncovering further dynamics and consequences of state-led foreign investment. In a world of rising protectionism, of nationalist backlashes, and the dismantling of institutions of global economic governance, the relevance of the state as economic actor will only increase. IPE needs to be able to study, illuminate, and critique these dynamics, for which this paper offers a set of tools and findings to start with.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (576.2 KB)Acknowledgments

I am grateful for the help, advice and comments on previous manuscript versions from Ilias Alami, Malcolm Campbell-Verduyn, Daniel DeRock, Adam Dixon, Jan Fichtner, Annette Freyberg-Inan, Javier Garcia-Bernardo, Naná de Graaff, Eelke Heemskerk, Elsa Massoc, Daniel Mügge, and Arjan Reurink. I am also indebted to the organizers and participants of various panels at the 2019 Politicologenetmaal, SASE, and IIPPE conferences as well as all participants of the PETGOV PhD club at the University of Amsterdam. I also thank three anonymous reviewers for excellent and constructive comments. Randall Germain and the RIPE editorial board provided exceptional guidance in the review process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Bureau van Dijk’s ORBIS database (https://www.bvdinfo.com/). Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study. Data are available from the author with the permission of Bureau van Dijk. The nationally aggregated and processed data as well as more supplementary material and the Python script are freely available at the Open Science Framework at https://osf.io/rkx7e/?view_only=2759b4b447204420b1353c62e7a6febe.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Milan Babic

Milan Babić is a postdoctoral researcher within the SWFsEUROPE project at Maastricht University and incoming Assistant Professor of Global Political Economy at Roskilde University. He is a member of the CORPNET research group at the University of Amsterdam. His work deals with the transition of the global political economy from a neoliberal towards a post-neoliberal global order.

Notes

1 In this paper, I use the terms ‘foreign state investment’ and ‘transnational state capital’ as describing the same phenomenon from different perspectives: the former describes the process, the latter the substance of states creating ownership ties cross-border.

2 I do not discuss the ‘commercial’ reading of cross-border state investment separately here because this position remains agnostic about most of the compared aspects. It is thus in many respects a ‘non-position’, as state investment is not understood as being significantly different from private investment.

3 I thank an anonymous reviewer for pointing this issue out to me.

4 Due to the limited wordcount, I discuss the role of GPN theory and other issues around the cluster construction in-depth in the appendix. The appendix (Supplemental Material tab online) furthermore details and discusses these methodological choices also with regard to alternatives to geo-industrial clusters.

5 See the appendix (Supplemental Material tab online) for an explanation and discussion of the various methodological choices and data cleaning steps taken in this section.

6 A list of all 31 clusters can be found in the Appendix (Supplemental Material tab online).

7 For space reasons, I do not separately discuss three clusters in Northern and Western Europe, one in Latin America, and one in Southern Europe that exhibit a relatively low degree of comparability. The first three are located in areas with enough other illustrated clusters that give a substantive overview of the area. The fourth case is largely dominated by an offshore construct by Russian state-owned Rosneft into the Virgin Islands and is thus not geoeconomically relevant. The last case is also dominated by a single tie of a holding company.

8 For a recent cooperation between state-owned Rosatom (Russia) and DP World (Emirates) on container shipments see Kolodyazhnyy et al. (Citation2021); for state-led geoeconomic competition within global logistical networks and other infrastructures see Schindler et al. (Citation2021).

References

- Abdelal, R. (2013). The profits of power: Commerce and realpolitik in Eurasia. Review of International Political Economy, 20(3), 421–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2012.666214

- Alami, I., & Dixon, A. D. (2020a). State capitalism(s) redux? Theories, tensions, controversies. Competition & Change, 24(1), 70–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/1024529419881949

- Alami, I., & Dixon, A. D. (2020b). The strange geographies of the ‘new’ state capitalism. Political Geography, 82, 102237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2020.102237

- Babic, M., Fichtner, J., & Heemskerk, E. M. (2017). States versus corporations: Rethinking the power of business in international politics. The International Spectator, 52(4), 20–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/03932729.2017.1389151

- Babic, M., Garcia-Bernardo, J., & Heemskerk, E. M. (2020). The rise of transnational state capital: State-led foreign investment in the 21st century. Review of International Political Economy, 27(3), 433–475. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2019.1665084

- Berlich, C., Daut, F., Freund, A. C., Kampmann, A., Killing, B., Sommer, F., & Wöhrmann, A. (2017). Deutsche Bahn AG: A former monopoly off track? The CASE Journal, 13(1), 25–58. https://doi.org/10.1108/TCJ-07-2014-0051

- Blackwill, R. D., & Harris, J. M. (2016). War by other means: Geoeconomics and statecraft. Belknap Press.

- Borchert, H. (2019). Flow control rewrites globalization (HEDGE21 strategic assessment). ALCAZAR Capital Ltd.

- Braunstein, J. (2019). Domestic sources of twenty-first-century geopolitics: Domestic politics and sovereign wealth funds in GCC economies. New Political Economy, 24(2), 197–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2018.1431619

- Bremmer, I. (2010). The end of the free market: Who wins the war between states and corporations? Penguin.

- Carney, R. W. (2018). Authoritarian capitalism. Sovereign wealth funds and state-owned enterprises in East Asia and Beyond. Cambridge University Press.

- Clark, G. L., Dixon, A. D., & Monk, A. H. B. (2013). Sovereign wealth funds. legitimacy, governance, and global power. Princeton University Press.

- CNBC. (2020). Norway wealth fund earned a record $180 billion in 2019. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2020/02/27/norway-wealth-fund-earned-a-record-180-billion-in-2019.html

- Coe, N. M., Dicken, P., & Hess, M. (2008). Global production networks: Realizing the potential. Journal of Economic Geography, 8(3), 271–295. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbn002

- Coe, N. M., & Yeung, H. W. (2015). Global production networks: Theorizing economic development in an interconnected world. Oxford University Press.

- Cohen, B. J. (2009). Sovereign wealth funds and national security: The great tradeoff. International Affairs, 85(4), 713–731. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2346.2009.00824.x

- Crasnic, L., Kalyanpur, N., & Newman, A. (2017). Networked liabilities: Transnational authority in a world of transnational business. European Journal of International Relations, 23(4), 906–929. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066116679245

- Cuervo-Cazurra, A. (2018). Thanks but no thanks: State-owned multinationals from emerging markets and host-country policies. Journal of International Business Policy, 1(3–4), 128–156. https://doi.org/10.1057/s42214-018-0009-9

- Cuervo-Cazurra, A., Inkpen, A., Musacchio, A., & Ramaswamy, K. (2014). Governments as owners: State-owned multinational companies. Journal of International Business Studies, 45(8), 919–942. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2014.43

- de Graaff, N., & van Apeldoorn, B. (2017). US elite power and the rise of ‘statist’ Chinese elites in global markets. International Politics, 54(3), 338–355. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41311-017-0031-2

- Dicken, P., Kelly, P. F., Olds, K., & Yeung, H. W. (2001). Chains and networks, territories and scales: Towards a relational framework for analysing the global economy. Global Networks, 1(2), 89–112. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0374.00007

- Drezner, D. W. (2008). Sovereign wealth funds and the (in)security of global finance. Journal of International Affairs, 62(1), 115–130.

- EC. (2017). Mergers: Commission clears ChemChina acquisition of Syngenta, subject to conditions. European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_17_882

- Farrell, H., & Newman, A. L. (2019). Weaponized interdependence. How global economic networks shape state coercion. International Security, 44(1), 42–79. https://doi.org/10.1162/isec_a_00351

- Ferdinand, P. (2016). Westward ho-the China dream and ‘one belt, one road’: Chinese foreign policy under Xi Jinping. International Affairs, 92(4), 941–957. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2346.12660

- FTC. (2017). FTC requires China National Chemical Corporation and Syngenta AG to divest U.S. assets as a condition of Merger. Federal Trade Commission. https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2017/04/ftc-requires-china-national-chemical-corporation-syngenta-ag

- Garcia-Bernardo, J., Fichtner, J., Takes, F. W., & Heemskerk, E. M. (2017). Uncovering offshore financial centers: Conduits and sinks in the global corporate ownership network. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 6246.

- GeoPost. (2018, July 10). GeoPost: Parcels, even at the other end of the world. https://www.groupelaposte.com/en/geopost–parcels-even-at-the-other-end-of-the-world

- Gertz, G., & Evers, M. M. (2020). Geoeconomic competition: Will state capitalism win? The Washington Quarterly, 43(2), 117–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163660X.2020.1770962

- Gilpin, R. (1987). The political economy of international relations. Princeton University Press.

- Goldthau, A., & Sitter, N. (2020). Power, authority and security: The EU’s Russian gas dilemma. Journal of European Integration, 42(1), 111–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2019.1708341

- Haberly, D., & Wójcik, D. (2017). Earth incorporated: Centralization and variegation in the global company network. Economic Geography, 93(3), 241–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2016.1267561

- Hannas, W. C., & Tatlow, D. K. (Eds.). (2020). China’s quest for foreign technology: Beyond espionage. Routledge.

- Helleiner, E., & Lundblad, T. (2008). States, markets, and sovereign wealth funds. German Policy Studies, 4(3), 59–82.

- Henderson, J., Dicken, P., Hess, M., Coe, N., & Yeung, H. W.-C. (2002). Global production networks and the analysis of economic development. Review of International Political Economy, 9(3), 436–464. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290210150842

- Horner, R. (2017). Beyond facilitator? state roles in global value chains and global production networks. Geography Compass, 11(2), e12307.

- Jones, L., & Zou, Y. (2017). Rethinking the role of state-owned enterprises in China’s rise. New Political Economy, 22(6), 743–760. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2017.1321625

- Jungbluth, C. (2018). Kauft China systematisch Schlüsseltechnologien auf? Chinesische Firmenbeteiligungen in Deutschland im Kontext von “Made in China 2025“. Bertelsmann Stiftung.

- Khalili, L. (2020). Sinews of war and trade: Shipping and capitalism in the Arabian Peninsula. Verso.

- Kirshner, J. (2009). Sovereign wealth funds and national security: The dog that will refuse to bark. Geopolitics, 14(2), 305–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650040902827765