Abstract

Karl Polanyi’s double movement is a key tool for conceptualising free market fatigue in African business communities wrought by the insecurities of trade liberalisation. Synthesising Polanyi with Kwame Nkrumah’s work on neo-colonialism, the article argues that exhausted business communities in Africa can contest free market reforms and push for a return to developmentalist strategies, underscoring a double movement. In this discussion it highlights Ghana, a ‘donor darling’ in terms of historical implementation of free market reform. It builds upon the author’s engagement with 66 interviewees – business people and policy stakeholders – in relation to the condition of that country’s poultry and tomato industries. Unpacking interviewee narratives, the article points to a striking common theme, namely that business stakeholders call for the re-embedding of the economy via developmentalist strategies to move beyond neo-colonial trade systems. In this vein, the article provides an original contribution to studies of International Political Economy by demonstrating the efficacy of a Nkrumah-Polanyi ensemble for making sense of business communities’ potential role in countermovements for developmentalism in Africa.

Introduction

Karl Polanyi’s warnings about the social repercussions of free markets and his analysis of countermovements to re-embed the economy in society have generated fruitful debate in the context of free market globalisation. His key text, The Great Transformation, predicted his generation’s triumph over free market fundamentalism owing to the emergence of a regulatory Keynesian consensus (Polanyi, Citation2001, [1944]). The implementation of free market reforms from the late 1970s onwards, however, has witnessed the resurgence of laissez-faire economics and free market orthodoxy, with all the intendent social malaise which Polanyi described as being associated with disembedded economic systems. Polanyi’s concept of the double movement, meanwhile, has assisted current scholars to conceptualise: (i) the state and corporate actors driving free market policies and laissez-faire economics which disembed the market from societal control; and (ii) societal actors and organisations which can, and do, form coalitions as part of countermovements that contest disembedding.

Despite the position of African countries as laboratories of free market approaches to ‘development’ from the Washington ConsensusFootnote1 onwards, the African continent has been relatively neglected by literature on Polanyi. Further, it has largely neglected consideration of the potential agency of small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs), whether in Africa or elsewhere, within countermovements aimed toward the re-embedding the market. Instead, applications of Polanyi have often been devoted to the role of ‘progressive’ actors such as peasant farmers, environmental associations, migrant workers, trade unions, women’s associations, and subaltern civil society within a double movement (Burawoy, Citation2010, p. 302). This is in contrast to Polanyi himself, who explicitly detailed the role of small business owners and landlords in contesting market disembedding. Perhaps most notably, Polanyi (Citation2001, p. 174) detailed the relative strength of what he termed ‘enlightened reactionaries’ (landlords) in contesting laissez-faire policies in 19th Century England.

The relative omissions of Africa and the agency of business communities within the existing scholarship on Polanyi is a considerable gap and a missed opportunity to understand private sector contestations of free market reform in the continent (see for instance – Bond, Citation2005; Goodwin, Citation2018; Levien & Paret, Citation2012; Sandbrook, Citation2011; Levien, Citation2018 – who all call for additional Polanyian critiques of development in the Global South). Polanyi’s critique of disembeddedness and the double movement can help to articulate, and to comprehend, the position of African businesses in global free markets. This is particularly so when Polanyi’s insights are married to that of complementary critical theorists for a fuller understanding of the elite power strategies that underpin free markets (see for instance Birchfield, Citation1999, Burawoy, Citation2003 and Peck, Citation2013a who explain the utility of such syntheses).

In this vein, the article argues that the work of Kwame Nkrumah (Citation1965) on neo-colonialism is a vital complement to a Polanyian critique of free market contestation in Africa. Nkrumah’s insights are key to understanding donor impositions of free market policies and to assessing countermovements towards developmentalist alternatives.Footnote2 His critique of neo-colonial power strategies involving the use of donor aid money is particularly important. Nkrumah (Citation1965, p. xv) convincingly explained how donors’ aid-giving could co-opt African elites into acquiescence to free market orthodoxies despite negative consequences for local businesses and SMEs. His critique of neo-colonial trade systems (that is, systems centred around colonial patterns of exchange involving export of raw materials and importation of value-added goods from the metropole), and the need for African states’ diversification into agro-processing and manufacturing, is also essential to understanding contemporary African business calls for developmentalist alternatives to free markets.

The article therefore articulates the benefits of a Nkrumah-Polanyi conceptual ensemble for making sense of business contestations of free markets in the case of Ghana – a West African ‘donor darling’ given successive governments’ faithful implementation of (Post-)Washington Consensus reforms. Through case studies on the Ghanaian poultry and tomato sectors, the article builds upon the author’s field engagement with 66 interviewees – private sector and policy stakeholders – to assess business communities’ feelings of free market fatigue. In so doing it highlights their desire for a re-embedding of the economy in terms of a return to state intervention and developmentalism.Footnote3 In this vein, business communities can be seen as potential actors within countermovements away from neo-colonial trade systems. Perhaps paradoxically, alleged beneficiaries of free market reforms in the Global South – private sector entrepreneurs – may long for a reprieve from the insecurities of free markets and wish to embrace greater market regulation. Through a focus on Ghana, the article provides an important addition to the Polanyian literature, helping to realise the potency of a Nkrumah-Polanyi conceptual combination for making sense of development conundrums in Africa today.

The discussion is structured as follows. The first section spells out the utility of a Nkrumah-Polanyi conceptual combination. The second section contextualises the history of free market reform in Ghana and underscores the hegemonic status of free market orthodoxy. The third section examines Ghanaian business narratives regarding the impact of trade liberalisation and desire for a return to a developmental state. The fourth section reflects on the benefits of the Nkrumah-Polanyi combination for making sense of societal pressure for a return to state intervention and developmentalism. The conclusion summarises key arguments and reflects on the need for Polanyian literature to embrace African intellectuals in the critique of free market approaches to ‘development’ in the Global South.

A Nkrumah-Polanyi combination: Understanding free market contestations in Africa

Polanyi’s analysis of the double movement has had a marked impact on debates surrounding free market globalisation and the contestation of laissez-faire economics. In The Great Transformation, Polanyi (Citation2001 [1944]) put forth his famous treatise regarding the historical anomaly of free markets. He explained that throughout history, economies had been ‘embedded’ in their societies. That is, they had been regulated by societal institutions and societal norms concerning the limits of acceptable economic behaviour. He pointed, for instance, to feudal and mercantilist economies as being embedded in the societies which had practised those forms of production and exchange (Polanyi, Citation2001, p. 70). In the 19th Century up to the 1930s, however, Polanyi explained that liberal economists had promulgated a utopian free market ideology based upon the philosophy of self-regulating markets. Accordingly, free market systems which arose from implementation of liberal economic ideology became increasingly disembedded from the societies in which they came into being. Economic life under the free market system, for Polanyi, was not (and is not) subordinate to societal institutions and societal norms. Instead, free markets become ‘disembedded’ from society and function according to their independent prerogatives of supply, demand, competition, and profit (Polanyi, Citation2001, p. 73). In this process, the free market also commodifies aspects of social relations which are previously unencumbered by economic demands. What he termed ‘market societies’ arise, in which societal needs come second place to free market imperatives (Polanyi, Citation2001, pp. 74–75).

This concept of (dis)embeddedness was of course married to Polanyi’s other key concept – that of the double movement. Simply put, Polanyi argued that while there were liberal ideological forces which successfully pushed for the construction of free markets, their actions provoked a countermovement from opposing social forces that experience the material hardships associated with untrammelled capitalism (Polanyi, Citation2001, p. 151). Groups in society who had lost their jobs as a result of free market competition, seen their businesses decline due to the removal of protective import tariffs, or had suffered pollution and health hazards from market deregulation would coalesce within a social coalition aimed at re-embedding the economy. Importantly, Polanyi recognised here that ‘enlightened reactionaries’ such as landowners and small business owners could often play a key role in contesting free market orthodoxy. Moreover, in Polanyi’s own lifetime he saw that countermovements to push back against free market advances (hence the double movement) in numerous Western societies had won significant gains. As such, he was optimistic that his generation had intellectually put paid to free market fundamentalism (Polanyi, Citation2001, p. 242).

While these Polanyian concepts have been applied to assess free market reforms in the Global South – notably in Latin American countries vis-à-vis peasant and left-wing social movements – there is a relative dearth of contemporary literature on Polanyi focused on African experiences or on the agency of Polanyi’s ‘enlightened reactionaries’. Notable exceptions in terms of a focus on Africa include Bond (Citation2005); Bond and Mottiar (Citation2013); Bezuidenhout and Kenny (Citation2000), and Edward Webster et al. (Citation2008) who consider the relevance of Polanyi for making sense of labour movements in South Africa. Additionally, Harris and Scully (Citation2015) have considered disembedding in terms of the situation of peasants and workers in Ethiopia and South Africa. Meanwhile, Zayed (Citation2021) and Mati (Citation2013) have assessed democratic protests against authoritarian governments in Ethiopia and Kenya in terms of the double movement. The majority of literature that cites Polanyi in an African context, however, only mentions his concepts in passing and certainly does not consider the agency of African business entrepreneurs in potential coalitions. Again, this omission of the role of business communities in countermovements is common to the broader literature on Polanyi. This is a gap which this article seeks to rectify.

Before considering the benefits of a Nkrumah-Polanyi conceptual combination, however, it is necessary to first engage critiques of Polanyian frameworks. Polanyi’s conception of market (dis)embedding and the double movement has been the subject of diverging interpretations and critique. In particular, the concept of embeddedness has been described as a ‘slippery’ metaphor which generates fruitful debate, but which falls down in terms of analytical utility (Hodgson, Citation2017, p. 18). The implication, for example, that disembedded free markets are somehow totally divorced from society and its moral codes is disputed by a number of authors. Sayer (Citation2000) convincingly argues that all economies – even free markets – are moral economies in the sense that they have a dialectical relationship with societal norms. Sayer explains that free market actors co-opt existing societal norms to legitimise economic behaviours. For instance, multinational corporations portray themselves as being sensitive to public sentiments on social and ecological issues to protect profits (Langan, Citation2013). Likewise, free market actors may reshape societal norms. In Ghana, for example, local entrepreneurs have established Charismatic Pentecostal churches which make substantial profits from their congregations while preaching free market interpretations of the gospels (emphasising wealth accumulation as evidence of God’s favour) (De Witte, Citation2018). Such entrepreneurs have reshaped Ghanaian society and public sentiment in the process. Polanyi’s concept of (dis)embeddedness is therefore seen as problematic as it appears to downplay or outright dismiss how free markets are in a continual two-way negotiation with society and its moral codes to safeguard profitability.

From another angle, Polanyi has been criticised for failing to adequately contend with issues of social class (see for instance Dale, Citation2016). Polanyi’s call in The Great Transformation for a paradigm shift from free markets to socialism is understood to lack specificity about the necessary class configurations for such a transition. The concept of the double movement is also seen to lack a rigorous critique of power relations in society as found in accounts like Gramsci’s radical critique of civil society as a zone for the construction of consent for hegemonic rule. In this context, Peck (Citation2013b) explains the utility of what he calls a ‘Polanyi plus’ stance. This entails marrying Polanyi’s critique of free markets to that of key compatible authors for a more thorough critique of power relations within global capitalism.

These critiques of Polanyi deserve attention before applying his concepts to the examination of free markets and contestations in Africa. Clearly, if the concept of (dis)embeddedness wrongly implies that free trade systems are completely divorced from society’s norms then that is a major analytical danger. One way of overcoming this, however, is to interpret Polanyi’s concept of re-embedding in relation to the complementary idea of ‘resubordination’ – as advocated by Burawoy (Citation2003) and Sandbrook (Citation2011). Reading Polanyi’s call for re-embedding as a call for the re-subordination of the economy to societal needs expresses his intent to emphasise how markets must not be permitted to privilege profit above citizens. While free market systems certainly do – in parasitic fashion – draw upon society’s moral norms to justify business behaviour, nevertheless the wellbeing of democratic society is still subordinated to economic imperatives – with all the corollary social and ecological implications which Polanyi identified. The notion of (re)subordinating the economy thus avoids analytical pitfalls associated with stricter applications of Polanyi’s (re)embedding metaphor. Re-subordination emphasises the need to place markets back under full societal control while avoiding the implication that free markets are completely divorced from strategic negotiation with societal sentiments and norms (which of course they are not).

The class critique of Polanyi, meanwhile, reflects a classical Marxist concern with the role of the working class in overcoming economic inequality. Polanyi, in contrast with classical Marxism, focuses more broadly upon the myriad social groups involved in countermovements to resubordinate the market to democratic social control (Burawoy, Citation2003, p. 214). As discussed earlier, Polanyi (Citation2001, p. 213) even identifies certain ‘enlightened reactionaries’ as important actors in countermovements, such as business communities in Bismarck’s Germany and landowners in 19th Century England who contested laissez-faire economics. This broader approach to the study of the social contestation of free market capitalism is not a pitfall in Polanyi’s analysis. By moving beyond the classical Marxist dichotomy of the proletariat-bourgeoisie struggle, The Great Transformation highlights how disparate social groups can come together to contest liberal economic ideology based upon common experience of free market insecurities. Brown (Citation2011) – drawing upon Stanfield – usefully explains that while Marx was concerned with economic inequality, Polanyi was instead more concerned with economic insecurity. Brown (Citation2011, pp. 69–72) goes on to convincingly argue that Polanyi’s broader conception of the insecurities caused by free markets (job losses, business closures, environmental catastrophe, and so forth) help to focus our minds upon the diverse groups who might play a role in re-subordinating markets to societal needs. Polanyi’s neo-Marxist stance is thus a potential strength in the study of free market globalisation as it makes its mark across the Global South.

A thornier critique of Polanyi, however, comes within neo-Marxist scholarship itself and contends that his view of (civil) society as a forum for progressive action to resubordinate markets unduly simplifies state-societal relations (see for instance Goodwin, Citation2018). Neo-Marxist writers correctly stress that a co-opted civil society can often act as an instrument of capitalist hegemony, as organic intellectuals aligned to elites use social institutions to propagate and uphold the public’s ‘commonsense’ acceptance of the necessity of free market capitalism (see e.g. Birchfield, Citation1999). With significance for African case studies, certain neo-Marxists also point to the need for a fuller understanding of the underpinnings of capitalist rule in former colonies with reference to the work of Frantz Fanon, Citation1961 (see e.g. Burawoy, Citation2003). This critique does not deny the potential of a Polanyian approach but instead draws attention to the need to blend Polanyian insights with that of complementary writers to gain a fuller understanding of state-societal relations.

These neo-Marxist critiques of Polanyi deserve particular attention in terms of the current assessment of free market fatigue in Africa (Burawoy, Citation2003; Peck, Citation2013a). However, it is equally important not to downplay divergences between Polanyi and key figures such as Gramsci and Fanon, who are often favoured within the existing neo-Marxist scholarship. Fanon, for instance, offered a scathing assessment of the inability of African businesspeople (the petty bourgeoisie) to offer opposition to neo-colonial trade systems. Fanon argued that middle class entrepreneurs in African countries would seek to maintain colonial-style trade in alliance with neo-colonial metropoles in the West. They would not offer a class basis for the realisation of the genuine sovereignty of African communities (Langan, Citation2018, p. 8). A divide therefore emerges between Polanyi’s identification of business communities as potential coalition members in relation to countermovements against laissez-faire economics and Fanon’s apparent rejection of their political worth. Gramsci, too, in his writings remained sceptical about the agency of entrepreneurs to meaningfully contest free market capitalism. (Birchfield, Citation1999, p. 45).

In the context of these divergences, a more fruitful combination exists in terms of a marriage of Polanyian insights to the work of Kwame Nkrumah (Citation1965). Bringing together Polanyi’s Great Transformation with Nkrumah’s Neo-Colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism is essential for the analysis of contestations of free market orthodoxy in the African continent. Nkrumah (Citation1965, p. ix) memorably defined the neo-colonial situation in which African states might find themselves after de jure independence as follows:

The essence of neo-colonialism is that the state which is subject to it is, in theory, independent and has all the outward trappings of international sovereignty. In reality its economic system and thus its political policy is directed by outside.

Control over government policy in the neo-colonial state may be secured by payments towards the costs of running the state, by the provision of civil servants in positions where they can dictate policy, and by monetary control over foreign exchange through the imposition of a banking system controlled by the imperialist power (1965, p. ix).

‘Aid’ therefore to a neo-colonial state is merely a revolving credit, paid by the neo-colonial master, passing through the neo-colonial state and returning to the neo-colonial master in the form of increased profits (1965, p. xv).

There is absolutely no doubt that the key to significant industrialization in this continent of our lies in a union of African states, planning its development centrally and scientifically through a pattern of economic integration. Such economic planning can create units of industrialism related to the unit resources, correlating food and raw materials production with the establishment of secondary manufactures and the erection of those vital basic industries which will sustain large-scale capital development (Nkrumah, Citation1963, p. 170).

Moreover, Nkrumah and Polanyi are united by a mutual concern to subordinate economic activities towards benefiting the whole citizenry and not merely an elite minority. Both are optimistic that local entrepreneurs may play a role in pushing for greater state intervention (and developmentalism) conducive to societal gain. Their insights together provide a useful toolkit for making sense of free market contestations in Africa. A Nkrumah-Polanyi ensemble can help us to understand the impact of free markets in Africa, the actors who sustain free trade agendas (including co-opted African elites), as well as the actors who can challenge free market orthodoxy (including business communities impacted by trade liberalisation). The following discussion of Ghana – and assessment of business stakeholders’ views in the tomato and poultry sectors – therefore utilises a Nkrumah-Polanyi conceptual combination.

Free market reform in Ghana and state/society agency

Ghana’s status as one of the most faithful African implementers of free market reform positions it as a useful case study within a Nkrumah-Polanyi critique of market fundamentalism. Following a military takeover by Jerry Rawling’s Provisional National Defence Council (PNDC) in 1981, Ghana soon embarked on far-reaching free market reforms in keeping with the prescriptions of the World Bank. A series of structural adjustment programmes (SAPs) from 1983 to 2000 brought about the radical transformation of the Ghanaian economy away from the developmental state models that had been pursued since independence. Although initial successes were witnessed in terms of the stabilisation of government revenues, the free trade orthodoxy enshrined in the SAPs mandated the dismantling of key protective tariff barriers.

Accordingly, Ghana’s economy soon became open to the importation of cheap foreign manufactures and subsidised foreign agricultural produce. This led to intense competitive pressures being placed upon domestic producers. As Opoku (Citation2010, p. 158) explains, premature market opening led to severe economic retraction. In particular, the rate of growth of Manufacturing Value Added (MVA) starkly declined from ‘12.9% in 1984 to 5.6% in 1989, and then to a mere 1.1% in 1990. By 1996 manufacturing accounted for a mere 4.8% of GDP, down from 7% in 1993.’ The decline of domestic manufacturing and agricultural production upon import flooding of cheap foreign goods had a simultaneous impact on livelihoods. Unemployment rose in the period of SAPs from under 2% in 1987/88 to over 8% in 2000 (Obeng-Odoom, Citation2012, p. 98).

Ghana’s free trade trajectory, meanwhile, has continued into the 2000s and the 2010s. Governments from the two main political parties – the New Patriotic Party (NPP) and the National Democratic Congress (NDC) – have adhered to free market orthodoxy. Perhaps most illustrative of their collective stance, both parties committed to the implementation of a controversial free trade deal with the European Union (EU) – the interim Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA).Footnote5 This is despite the fact that the interim EPA mandates liberalisation across 80% of tariff lines, with serious ramifications for import-competing local industries (CONCORD, Citation2015; European Commission, Citation2017a, p. 2; Langan & Scott, Citation2011). It is also despite the fact that the interim EPA includes a standstill clause which forbids Ghanaian governments from increasing current tariffs on EU goods, even for the 20% of tariff lines which have been exempted from the liberalisation schedule due to their sensitive status (including tomato and poultry) (see ActionAid Citation2013, p. 4; and European Commission, Citation2017b, Article 15).

As a result, Ghanaian governments – of either NDC or NPP hues – would in most scenarios be legally unable to accede to poultry and tomato producers’ demands to raise the current tariff level of 35% to discourage imports of EU frozen meat and tomato paste. The now locked-in 35% tariff falls well below potential WTO tariff ceilings and is deemed by local business stakeholders to be wholly insufficient to discourage import flooding. This is especially so since cheap imports are often dumped below actual production cost, as in the case of frozen poultry meat (see EPA Monitoring, Citation2018). Ghanaian governments would only be able to increase tariffs upon sensitive goods if they were able to prove that dumping or unfair subsidies had caused imports to have an exceptionally damaging impact on local producers. However, in practice the interim EPA’s inclusion of theoretical anti-dumping and countervailing safeguards offers little comfort. This is illustrated by the way in which the EU has resisted Southern African partners who attempted to enact likewise nominal safeguards within their own EPA (see e.g. EPA Monitoring, Citation2019).

It is relevant to note, however, that despite the NDC’s and NPP’s acquiescence to controversial free trade arrangements, Ghanaian governments have recently attempted to introduce limited state-led programmes for reviving select priority manufacturing and agro-processing sectors. The Presidency of the NPP’s John Kufuor (2001–2009) and that of NDC’s President John Mahama (2012–2017), for example, sought to stimulate domestic private sector development in poultry. However, as Opoku (Citation2010, p. 171) explains, their programmes have lacked the resources to meaningfully boost competitiveness (or deal with the issue of insufficiently robust external tariffs).

Ghana’s prolonged period of structural adjustment and its elites’ adherence to free market orthodoxy has subordinated societal needs to the imperatives of the free market – as described in Polanyi’s (Citation2001) work. Developmental state strategies have been largely abandoned in favour of laissez-faire economics involving withdrawal of government from ‘interference’ in the market. Deregulation and privatisation have been combined with the granting of increasingly unfettered access to Ghanaian markets for foreign exporters – in keeping with free market norms of comparative advantage and trade liberalisation. This has led to widening geographical disparities between the south of the country (with some foreign direct investment associated with export processing zones near the ports) and the struggling agricultural northern hinterlands (Awanyo & Attua, Citation2018). By 2001, after two decades of free market reform, Ghana sought international debt relief as a highly indebted poor country (Opoku, Citation2010).

Ghana’s historic economic retraction and attendant social malaise is perhaps best exemplified by the decline of the once thriving cotton-textiles industry. With the implementation of SAPs, Ghana lifted its restrictions upon the entry of foreign second-hand clothing. This led to profits for foreign traders and elite importers but resulted in the decimation of local textiles production that had previously been built under developmentalist strategies dating back to the Nkrumah Presidency (Ayelazuno & Mawuko-Yevugah, Citation2020). It also severed important backward linkages to cotton producers. By 1996, after more than a decade of SAP reforms, the Ghanaian textile sector retained only 60% of its capacity compared to its 1977 levels (Ayelazuno & Mawuko-Yevugah, Citation2020, p. 163). Elites within the NPP and the NDC, meanwhile, have adhered to free market reform packages to secure short-term donor aid revenues that are necessary for electoral success and political survival (Langan & Price, Citation2015).

The subordination of societal needs to the imperatives of laissez-faire economics has also resulted in free market ideology gaining wider cultural ascendancy in Ghanaian society. This is evidenced by the relative absence of civil society protest against reforms. Mawuko-Yevugah (Citation2013, pp. 12–13) points to the relative absence of student resistance since the 1990s and explains that the two-party system has enabled ‘political elites to co-opt recalcitrant youth through party recruitment mechanisms and distribution of political patronage in the form of political party leadership positions, ministerial appointments, and other enticements’ (Mawuko-Yevugah, Citation2013, p. 13). This perspective is corroborated by Ayelazuno (Citation2019, p. 21) who argues that sectarian ethnic affiliations – embodied by the two main parties – have crippled the ability of social movements to confront domestic elites.

Research on the Ghanaian situation also highlights that other key social elites – for example, church leaders and tribal chiefs – have adapted (and contributed) to the prevalence of free market norms in society, rather than contest them. Charismatic Pentecostal pastors, for instance, have established mega-congregations based upon a reading of the gospels which emphasises profit accumulation and material ostentation as core objectives within Christian doctrine (De Witte, Citation2018, p. 82). Their agency constructs and reinforces broader societal acquiescence to free trade orthodoxy. Tribal elders, meanwhile, have learned to position themselves within neo-colonial forms of foreign direct investment as actors who mediate between the state, donors and corporations in the granting of land releases. This is despite evidence of foreign corporate ‘land grabbing’ (Lanz et al., Citation2018, p. 1549).

Ghana’s relative lack of societal contestation of free trade reforms chimes fully with the warnings of Nkrumah about how neo-colonial systems may be secured by fostering tribal sectarianism. Nkrumah (Citation1965) warned that foreign powers would ferment ethnic divisions among African populations and support pliable sectarian elites. He argued that the only response would be to foster national unity within African countries and simultaneously to promote pan-African identities conducive to the creation of a Union of African States. Only by constructing developmental state models, overseen by a pan-African executive, would African citizenries overcome both sectarianism and neo-colonial dependency (Langan, Citation2018, p. 220).

Nevertheless, despite Ghana’s relative absence of protest against free market reforms, it is apparent from field engagement in the tomato and poultry sectors that there is free market fatigue within the country’s private sector. Farmers and processors appear united by a desire to see greater interventionism in their sectors, in keeping with developmental state strategies. As the narratives below illustrate, business stakeholders are exhausted by the impact of unfettered free markets and wish for Ghanaian governments to do more to diversify the economy away from neo-colonial patterns of trade.

Free market fatigue within Ghana’s poultry and tomato sectors

Recent field interviews with Ghanaian business communities indicate that there is a significant body of private sector opinion that is highly sceptical of the benefits of free market policies. Whereas donor discourse in the Post-Washington Consensus promotes the image of the entrepreneur as the engine of development and as the beneficiary of free market reform, business people in Ghana’s poultry and tomato sectors routinely expressed doubts as to the economic and moral legitimacy of free market orthodoxy. Business stakeholders regularly expressed the need for greater government intervention – including to do away with trade liberalisation policies embodied in free trade deals such as the controversial interim EPA. This is especially significant given that the business people concerned are not subsistence or peasant farmers (often the focus within the existing Polanyian literature on the Global South) but instead classify as entrepreneurs and managers within SMEs. Aligning to SME classification, a poultry farm on average employs between 30 and 50 workers, with the largest operators employing in the region of 500 persons (Eshun et al., Citation2014, p. 4; Kusi et al., Citation2015). In a similar vein, commercial farms producing tomatoes employ on average around 50 workers in the harvest season, with a permanent staff of around 5–10 workers (Gonzalez et al., Citation2016; Interview K, Citation2017). Focusing on poultry and tomato SME entrepreneurs in terms of their perspectives on free market policies fills an important gap within the Polanyian literature which has largely avoided focus on business persons in studies of countermovements.

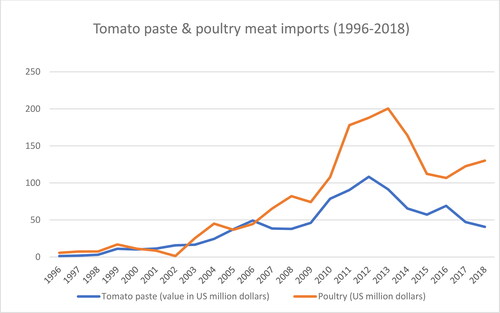

Interviewee business fatigue with free markets is especially significant given the strategic position of these two agro-processing sectors within Ghana. Poultry and tomato are staples in terms of local consumption. The poultry sector alone is estimated to have the potential to create 498,000 jobs under sufficiently robust external tariffs (to prevent import flooding). This is in comparison to only 4,625 actual jobs in 2010 under a low tariff model that encourages influx of cheap frozen chicken (Sumberg et al., Citation2013, p. 8). Poultry meat imports remain high, having reached a zenith of US $200 million in 2013 (see ). Tomato production, meanwhile, employs over 90,000 direct producers and over 300,000 in retail and wholescale (Agyekum, Citation2015, p. 12). Nevertheless, the tomato sector has experienced significant competitive pressures as a result of the import of cheap tinned tomato paste (see ). The value of tomato paste imports reached a peak in 2012 at US $108.3 million. Ghana’s large-scale Northern Star tomato factory created in the 1960s in conjunction with the developmentalist strategies of the Nkrumah government, consequently, remains mothballed despite government attempts to revive domestic processing in 2006 and 2009 (ABK, Citation2015). Indeed, both tomato and poultry are regularly highlighted by the Ghanaian Ministry of Food and Agriculture (MFA) as priority sectors for industrial upscaling in light of their historical decline (see, for instance, MFA, 2013). Poultry has also received a high degree of recent political publicity. In particular, its plight has been presented as evidence of President Akufo Addo’s (NPP) apparent failure to assist agriculture in the John Mahama’s (NDC) ultimately unsuccessful campaign to win back the Presidency in December 2020 (Krow, Citation2019).

Figure 1. Tomato paste & poultry meat imports (1996–2018).

Source: UN Comtrade (Citation2020) data available at: https://comtrade.un.org/data/

Poultry and tomato business stakeholders’ fatigue with free markets was readily apparent in a series of interviews conducted by the author in the country (2017–2020). A total of 66 interviews were held with business people and policy stakeholders. Participants were asked about the impact of free market reform, particularly in terms of the controversial EPA negotiations. Participants were also asked about connections between private sector growth and wider societal prosperity, and the potential role of government therein. Anonymity was granted to protect participants due to the business-sensitive nature of discussions and frank appraisals of government and donor policies. The interviews illustrate disjuncture between private sector perspectives and free market orthodoxy. Both Polanyi’s and Nkrumah’s attention to how business people may play a role in the re-subordination of markets therefore appears highly relevant in the case of Ghana.

Business fatigue with free trade agreements

One of the most prominent themes emerging from interviews was business stakeholders’ tiredness and aversion to external trade deals that entrench free market policies within Ghana. When asked about the much-publicised Ghanaian negotiations with the EU for an EPA, business people expressed their fatigue with premature market opening. Time and again interviewees lamented Ghanaian governments’ acquiescence to tariff dismantling and the resultant import flooding. They explained that such trade policies had decimated agricultural livelihoods since the 1980s. In the context of free trade deals, a poultry farmer explained that the lock-in of a low tariff model in Ghana would spell disaster:

People are making huge money from the importation of chicken. But it’s not the way to go. We should help the local people. If we solely depend on imported chicken, then it’s killing the local industry… [The EPA] it’s just for Europeans to dump stuff here… there should be some sort of sanity in the system (Interview A, Citation2017, 5.4.17).

[A free trade deal] will not help us. It will allow the influx of a lot of products, when you already have local producers struggling… The competition will kick us out… There should be a tax on importation… We should increase the tax, not reduce it…. [The EU is] supposed to be a source of relief but then they impose conditions that we should reduce our import tax. No! There will be an influx of products that we are already producing. No! It will kill our local producers (Interview B, Citation2017, 27.3.17).

In a nutshell, the EPA is not a good agreement… We do not support more imports. We are really suffering… Our restaurants are filled with this chicken coming from Europe… and it is really killing our poultry industry… And we have this tomato thing from Italy, and also coming in from China as well. It’s all over the place, in the supermarkets, the tomato paste, and it doesn’t really help us (Interview C, Citation2017, 24.3.17).

They abuse us, the European Union. All it does is give us conditions attached to aid. There will be a long-lasting impact, a social impact, of the EPA on the economy… We should not open up to more [import] flooding. We should be levelling the playing field… creating an enabling environment… with low interest loans, seed inputs… irrigation… sprinklers… research institutions (Interview D, Citation2017, 22.3.17).

In terms of the whole EPA discussion, we are against it [the trade deal]… Opening up 75% of our market will increase dependency. We can’t compete with anything. We have disadvantaged smallholders… and [trade liberalisation] is not good for the local appetite for local commodities. But we went ahead and signed it [the EPA] (Interview E, Citation2017, 23.3.17).

The EU has a ban on some vegetables here… It is bringing our [export] business down… They are complaining about the pesticides residue being so high… They just ban. They don’t give money to help the farmer… It’s not fair…. There has been a two-year ban on chili. Ghana was the best country at producing chili. It was our best. And we still don’t have access to the European market. That is the problem we are having. Big, big challenges. … The training and capacity building is not enough…. We are pleading with the EU to help (Interview F, Citation2017, 31.3.17).

Societal suffering as a result of free market ascendancy

This second key theme – of Ghanaians directly suffering as a result of free trade arrangements – was repeated on regular occasions. With clear parallels to Polanyi, business stakeholders lamented that the market now seemed divorced from wider societal needs. One civil society stakeholder contextualised this in terms of rising insecurity in the country. He explained that the collapse of agriculture under import flooding had encouraged unemployed youths to find money by joining political vigilante groups.Footnote6 He additionally queried how Ghana could be labelled by donors as a ‘middle-income country’ given widespread poverty:

How is this a middle-income country?! Poverty is scaring the youth. With the current government we have vigilante groups – Delta Force, the Invisible Forces, the Kandahar Boys – attacking public officials. The government is doing nothing. These are youth that have no jobs. The government should provide jobs but it is creating vigilante groups! Then what are we heading towards? It is a recipe for disaster… Even as we have these problems we have the EPA liberalisation… liberalisation among unequal partners is not helpful (Interview G, Citation2017, 28.3.17).

A poultry farmer concurred that premature liberalisation had costs jobs and had encouraged the formation of vigilante groups, destabilising the country:

The biggest [poultry] farm in the country has over 600 people… So if the industry is going down it means you have to sack. Then people are unemployed, and it brings poverty. If you’re not lucky it will increase the crime rate in the country. We now have Delta Force [vigilante group]. It’s youth who are not working. If they are well employed then there would be no Delta Force (Interview H, Citation2017, 28.3.17).

We want the industry to grow but it is not going well with us. There are a lot of problems. The main problem is the importation of the frozen chicken into the country. This is our main problem. It’s unfortunate to say that some of the farmers here are in a very dire situation… The young ones have no jobs (Interview I, Citation2017, 3.4.17).

It’s sad that Europe does these things to African countries. It’s very sad. Africa needs to grow and feed itself… But the [EU] competition is horrible. Our currencies are not stable because of all these things [imports]… When you are bargaining [Europeans for trade deals], you have the trump card, and you are just bullying us. If it is not addressed [import flooding] then it can become very chaotic in the end [here in Ghana]. … It must stop. It is very inhuman (Interview J, Citation2017, 5.4.17).

We remove taxes on it [tomato paste] … but we are creating jobs over there in Europe. Meanwhile the [local tomato] factory is dying and so young boys and girls become prostitutes or pickpockets and all sorts of things (Interview K, Citation2017, 19.4.17).

Aid money as lubricant for disadvantageous free trade policies

A third key theme was the issue of foreign aid. When asked why successive Ghanaian governments adhered to free market policies, respondents regularly highlighted the impact of foreign aid. Many pointed to aid conditionalities and explained that donor money lubricated local patronage networks and offered politicians an opportunity to offer some limited gains to the electorate (by spending on health or roads, for example). Nevertheless, business stakeholders viewed aid as offering short-term benefits at the expense of long-term economic growth due to attached free market conditionalities. A tomato farmer, for example, contextualised EU aid money as a threat to democracy:

There was definitely a pressure from somewhere… [the EU] put pressure on the Presidency to do that [sign the interim EPA]. That’s one of the biggest challenges, democracy. And yet we have these undemocratic pressures on our government… They [aid givers] pull the strings as and when they wish… Where is democracy?… We know from the technical studies, we have known it is not the right way to go [the EPA] but we also know if we don’t do it we lose development support…. If you lose development support then you can’t retain power. … [to pay for] health and education and the like…. Governments are very weak to open up to certain demands… and the electorate are not aware of this issue (Interview G, Citation2017, 28.3.17).

The government know what they gain, and it’s not about export rights… It’s about what they get from their partner governments in Europe [aid money]… African governments do not invest in people, they want easy growth. (Interview L, Citation2017, 13.4.17).

There are donor countries agitating the government to follow IMF conditionalities… It’s Western influence I’ll call it… So in terms of resources and investing in infrastructure, the government becomes vulnerable (Interview M, Citation2017, 30.3.17).

Locals always blame the government… But it is not so simple. The government has got to sign trade agreements … Donors talk about trade liberalisation… and there is [aid] conditionality… so there is no choice (Interview N, Citation2020, 21.1.20).

Political networks gaining from foreign importations

A fourth key theme was the role of Ghanaian politicians and their personal networks in terms of the importation of foreign goods. Interviewees explained that many Ghanaian politicians had a direct personal profit motive for adherence to a free market stance:

Most of the Big Men involved in the importation bring in big quantities of this thing [cheap frozen chicken and tomato paste imports]… They are Big, Big Men … That is why the Ministry has been advised not to talk too much about [improving local] livestock and poultry… They are not talking about that because politicians are involved in the [importation] trade. People [farmers] have gone down due to the cheap importation, and it is linked to the top (Interview O, Citation2017, 7.4.17).

It never saw the light of day. There came the huge lobbies in the import sector. They are very powerful and influential. They are friends of big politicians, or their relatives, or one of the politicians who are importing. Because you know who is behind a specific [importation] company. There was some conversation about that [import flooding], then some effort to reduce import of poultry and poultry products… but they [lobbyists] were able to stampede the government not to proceed with the legislation (Interview P, Citation2017, 18.4.17).

Why are we blindly following liberalisation? Why do we allow the import of poultry? Ghana should have to do something about that and have some level of restrictions … Our farmers cannot compete. We have huge balance of payments problems because we import what we produce … We need a level of protection … There should be some level of subsidies. But we have some of the leading importers related to the government… It’s a major problem not because they are a member of the government… But because they are long-time family friends (Interview N, Citation2020, 21.1.20).

The import lobby [is the problem]. The current President Nana… his relations owns one of the biggest cold stores in the country [used to store frozen imports] … It’s not being realistic [to expect policy change]. These people have invested money and they need to make money – profit or super profit [from imports] . … The environment for industry cannot be perceived in isolation from the general political environment… Interests are propped up by the powers that be (Interview Q, Citation2020, 24.1.20).

Government can be powerful in an environment such as ours… But people don’t understand what they are signing or what it means to say ‘yes, we are industrialising our economy’. There are a multiplicity of tools to keep out imports but I am not sure our policy-makers know that (Interview R, Citation2020, 23.1.20).

Business calls for Ghana’s government to pursue developmentalism

Importantly, these perceptions of the free trade status quo were often matched by expressions of the potential for Ghana to move away from its free trade orientation. Business stakeholders expressed some hope that Ghana could move towards a more interventionist economic model vis-à-vis realisation of a developmental state. This was a fifth key theme emerging across interviews. One poultry farmer, for example, contextualised current economic hardships in terms of the potential for government to take bolder decisions:

Unemployment rates are very high, crime rates are going up and the economy is not getting taxes… and imported goods always puts pressure on foreign exchange. It’s having a negative impact on the country and the people, the economy, and our health … I think African leaders must be bold enough to take decisions. The previous government signed [the EU EPA] because there was this [aid] compensation for this… if you sign then they give you some money… without thinking about the bad implications, they went ahead to sign… and so now anyone can bring anything into this country (Interview H 3.4.17).

We want regulation…. To impose a ban so we can produce some [agricultural goods] quietly…. We need a ban to protect the local vegetable producers. … (Interview F, Citation2017, 31.3.17).

We should reduce the percentage of the importation, and raise the prices a little bit on it… the government needs to sit down and work out all these things with the farmer… Government know how to control all these things….[they] need to put good structures like storage facilities, processing and packaging, that needs to be done by the government (Interview S, Citation2017, 10.4.17).

We are begging to do something about the new import varieties… It’s not only one company, it’s different varieties so we are pleading if you can do something to stop it…. [then] we will be happy. If the government put more tax on it, it would also benefit. We are pleading with the government to put more tax on tinned tomatoes and also help the local farmers (Interview T, Citation2017, 21.4.17).

There should be a conscious effort to build Ghana and we can do it… in Ghana we will import or we could make a system for ourself, which is riskier. It is the duty of government to take that risk, for five to ten years to see if we can build our industry. The government should take the lead to develop the market… with technology and know-how, with R&D. But the conscious effort is not there… we are not creating innovation (Interview U, Citation2017, 24.4.17).

Export sector solidarity with import-competing producers in Africa

It is important to note that this business fatigue with free markets – and desire for re-subordination of the market to societal needs – is not confined to producers in import-competing sectors facing the consequences of insufficiently robust external tariffs (such as poultry and tomatoes). It also appears evident within key export sectors in Ghana such as cocoa (see Langan & Price, Citation2020). This is particularly interesting since free trade deals – such as the EU EPAs – ostensibly benefit Ghanaian exporters by securing their ongoing access to European markets. Even cocoa stakeholders – dependent on such access to EU member states – expressed their fatigue with Ghanaian governments’ acquiescence to free trade models. They sympathised with the plight of their colleagues in import-competing sectors (Langan & Price, Citation2020). Such fatigue was also evident in interviews with exporters in East Africa in relation to field engagements in Uganda’s flower farm sector. Again, interviews found that Ugandan exporters of cut-flowers were concerned about the wider social impact of premature trade liberalisation with the EU (Langan, Citation2011). Flower farm stakeholders called, too, for greater government intervention to bolster sector competitiveness and to shift away from laissez-faire economic policies. The views of poultry and tomato stakeholders cannot be dismissed therefore as an anomaly or as the complaints of ‘sore losers’ from free trade reforms. Exporters, who nominally ought to benefit from free trade deals, appear equally concerned about trade liberalisation and the retraction of the state from economic life.

The double movement and the implications of free market fatigue

As the interviewee narratives above make clear, certain business communities in Ghana are experiencing free market fatigue. Namely, they are experiencing ennui with free market competition and a lack of government assistance to private sector development. Business actors regularly queried the societal benefits of trade liberalisation, pointing to consequences in terms of lost livelihoods and social instability. Moreover, they pinpointed donor aid as a corrupting influence – and highlighted politicians’ personal networks as profiting from foreign importations. They lamented the historical lack of assistance that their businesses had received despite the onslaught of cheap frozen chicken and tinned tomato paste from Europe and beyond. Nevertheless, they remained hopeful that, with sufficient government determination, the situation could improve through the reimposition of protective tariffs coupled to appropriate government assistance to improve productive capacities in key priority agro-processing sectors.

Applying a Nkrumah-Polanyi combination, it is clear that business communities can and do play an important role in articulating a societal need for countermovements aimed towards the re-subordination of the market. Private sector actors who experience the insecurities of free market systems provide important voices in articulating the need to re-embed the market vis-à-vis democratic societal control of the economy. Just as Polanyi highlighted the role of the ‘enlightened reactionaries’ – landowners and small business owners – in the 19th Century as important actors contesting free market orthodoxy, so too are Ghanaian business stakeholders today articulating contestations of free market orthodoxy. Based on their lived experiences, they are explicitly challenging governments’ acquiescence to donor demands. Coupling this to Nkrumah’s insight on developmental states as an avenue to combat neo-colonialism, it is clear that certain business communities can provide a political voice for the re-construction of developmentalism in Africa. Although developmental structures were dismantled during the Washington Consensus, there nevertheless remains business will for greater state co-ordination and planning. Business leaders in sectors such as poultry and tomato remain wholly unconvinced that free market comparative advantages will allow Ghana to diversify and to provide jobs for its youth. In keeping with Nkrumah’s vision of a thriving domestic business community aligned to developmental state strategies, stakeholders in these sectors long for the return of government intervention in the market – against free market orthodoxy.

In pinpointing donor aid and the role of politicians’ networks in the foreign importation business, meanwhile, business stakeholders also highlight the dangers of neo-colonialism articulated by Nkrumah. The interviewee narratives illustrate business community beliefs that donor aid unduly sway governments in Ghana. Business leaders explain that short-term aid is necessary for politicians’ short-term survival and so they acquiesce to trade deals despite the longer-term consequences for Ghana’s sectors. Due to foreign partners’ imposition of non-tariff barriers, meanwhile, they do not believe that the woes faced by import-competing sectors will be compensated by greater opportunities for export sectors (such as chili). Instead, they fear that Ghanaians will remain locked out of European markets, while forced to accept an unmitigated influx of cheap manufactures and subsidised agricultural produce. Tomato and poultry stakeholders’ scepticism of free trade deals, meanwhile, is corroborated by exporters themselves – for instance in the Ghanaian cocoa and Ugandan floriculture sectors (Langan, Citation2011; Langan & Price, Citation2020). Exporters often concur that the wider impact of premature free trade deals will have deleterious consequences for African economies (while condemning non-tariff barriers as a form of hidden protectionism on the part of their international trade partners, including the EU).

There are clear opportunities, therefore, for societal actors in Ghana – whether in trade justice organisations, trade unions or left-leaning political parties – to forge coalitions with fatigued business persons wracked by the insecurities of laissez-faire policies. The lived experiences, testimonies and political articulations of business persons in sectors such as poultry and tomatoes provide ample insight on how neo-colonial trade patterns disadvantage Ghana. These fatigued business communities are well positioned to challenge the free market status quo in Ghana and the wider region. Interestingly, signs of coalition building between such business actors and civil society have already emerged in the Western African nation of Cameroon, where the ‘Chickens of Death’ campaign united poultry farmers with trade justice organisations to contest the importation of hazardous frozen chicken produce from Europe and to call for greater government intervention (ACDIC et al., Citation2007, 2). Opportunities are present in Ghana for like-minded coalitions – uniting discontented business communities, trade unionists, progressive politicians, and others – to contest the free market consensus embodied in the governing elite of the NPP/NDC. This is a key insight of Polanyi’s writings – one often omitted in the contemporary literature – that it is a myriad of diverse forces, including ‘enlightened reactionaries’ in the business world, who may converge to re-embed the market in society, not solely subaltern groups deemed by scholars to be ideologically progressive.

It is clear from the above discussion of Ghana, meanwhile, that the Nkrumah-Polanyi combination is highly useful for making sense of development quandaries in Africa and the wider Global South. This blended approach – synthesising insights from Nkrumah and Polanyi – reminds us of the need for coalition building as part of countermovements in response to untrammelled free markets. It reminds us of the potential role played by business leaders when their efforts are aligned to national (or pan-African) developmental strategies. In the African context, the combined approach also reminds us of the dangers of neo-colonial intrusion. For instance, in the form of aid-giving attached to disadvantageous free trade deals such as the EU’s EPAs. It can also help keep scholars and developmentalist coalitions alert to the dangers of civil society and political party co-optation under conditions of neo-colonialism.

Conclusion

A Polanyian critique of market disembeddedness and the double movement is highly relevant for making sense of development quandaries in Africa in an era of free market globalisation. African countries have long been treated as laboratories for far-reaching reforms from the Washington Consensus to the contemporary Post-Washington Consensus. In this process, conditions have arisen for social groups affected by free market insecurities to come together in opposition to the continued roll-out of free trade policies and to promote re-subordination of the market to societal needs. The above discussion has illustrated how a Nkrumah-Polanyi conceptual combination can give a full account of both the opportunities for, and the potential dangers facing, such societal coalitions. Moreover, Nkrumah and Polanyi remind us of the potential inclusion of ‘enlightened reactionaries’ in business communities in relation to countermovements that contests laissez-faire economics and free market orthodoxy. Moving beyond the proletariat-bourgeois dichotomy, Nkrumah and Polanyi remain optimistic that manufacturers and agricultural producers aligned to developmental state strategies can play an important role in moving societies beyond free market dependencies. The article’s discussion of the perspectives of business stakeholders within Ghana’s tomato and poultry sectors largely confirms their optimism given the abundant private sector fatigue with free market reforms and interviewees’ clear desire for greater government market intervention. The article also stands as a corrective within the existing literature on Polanyi, which has largely omitted consideration of business actors’ potential importance within coalitions driving countermovements – despite Polanyi’s own emphasis on their influence within his own conceptualisations of the double movement. It also corrects that existing literature’s relative geographical omission of African contexts when assessing free market contestations in the Global South.

Furthermore, the article has demonstrated that Polanyi – when combined with critical political economy perspectives from the Global South – provides us with a powerful conceptual toolkit for understanding (i) the role of free market policies in securing global capitalism in developing regions and (ii) the forces which can bring about countermovements focused upon developmentalism. Engaging African business perspectives and African scholars like Nkrumah, meanwhile, pays conceptual dividends and helps to realise a decolonization agenda not only in terms of North-South economic relations but within the discipline of International Political Economy. Engaging the writings and speeches of African leaders – ranging from Kwame Nkrumah to Thomas Sankara to Bobi Wine to Samia Nkrumah, among many others – is an essential task for a radical Polanyian literature that seeks to open up space for contestations of donor-imposed free markets in the African continent, and the wider Global South.

Acknowledgements

Sincere thanks to the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and recommendations which helped to hone the argument in this article. Many thanks also to Luis Lopes Costa and Katharine Wright for their encouragement and support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Mark Langan

Mark Langan is Senior Lecturer in International Political Economy at King’s College London. He is particularly interested in the trade and development aspects of EU relations with African countries. In the context of his study of intrusive donor interventions, Mark is interested in African liberation thought, neo-colonialism, pan-Africanism and democratic developmentalism.

Notes

1 See, for instance, Cammack (Citation2004) and Fine and Saad-Filho (Citation2014) for critique of the free market footing of current day Post-Washington Consensus donor policies.

2 Nkrumah’s government actively provided state support for the creation of key industries as part of a developmentalist drive to move Ghana beyond colonial patterns of production. This coincided with the wider Keynesian consensus of the immediate post-war period in which Western donors themselves envisaged a role for the state in economic development in former colonies (see for instance Bilotti, Citation2015 on the Keynesian consensus and development approaches in the Cold War period). Contemporary business demands for state intervention and developmentalism in Ghana, therefore, reflect a desire to return to an embedded economic model, as had historically been pursued prior to donor-sponsored free market reforms in the Washington Consensus. See Ayelazuno and Mawuko-Yevugah (Citation2020) for extensive discussion of Nkrumah’s historical economic programmes.

3 Ha-Joon Chang (Citation2010) defines the concept of developmentalism/developmental states as follows: ‘developmental state… [is] a state that intervenes to promote economic development by explicitly favouring certain sectors over others’. He also explains that the historical literature on developmental states focuses upon East Asian varieties that involved active state involvement in economic co-ordination through robust industrial policies. State actors in return gained popular legitimacy through impressive economic performance in the region.

4 Again please see Ayelazuno and Mawuko-Yevugah (Citation2020) for an extensive discussion of Nkrumah’s historical developmentalist strategies.

5 It is known as the interim EPA since the EU hopes that Ghana will eventually accede to a full West African EPA alongside Nigeria, Ivory Coast and other regional partners (see CONCORD, Citation2015). The ongoing refusal of Nigeria to implement this regional free trade deal, however, has effectively put paid to the EU’s wider ambitions for the time being.

6 See Asamoah (Citation2020) on political vigilantism in Ghana.

References

- ABK. (2015, December 14). What led to the closure of the Pwalugu tomato factory? News Ghana. Retrieved September 14, 2020, from https://newsghana.com.gh/what-led-to-the-closure-of-pwalugu-tomato-factory/

- ACDIC, EED, ICCO and APRODEV. (2007). No more chicken, please: How a strong grassroots movement in Cameroon is successfully resisting damaging chicken imports from Europe, which are ruining small farmers all over West Africa. Jaunde: ACDIC. Retrieved August 9, 2021, from https://actalliance.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/071203_chicken_e_final.pdf

- ActionAid (2013). Ghana under Interim Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA): Analysis of socio-economic development and policy options under the Interim EPA regime with the European Union. Accra: ActionAid

- Agyekum, E. (2015). Overview of tomato value chain in Ghana. Ministry of Food and Agriculture.

- Asamoah, K. (2020). Addressing the problem of political vigilantism in Ghana through the conceptual lens of wicked problems. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 55(3), 457–471. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021909619887608

- Awanyo, L., & Attua, E. M. (2018). A paradox of three decades of neoliberal economic reforms in Ghana: A tale of economic growth and uneven regional development. African Geographical Review, 37(3), 173–191.

- Ayelazuno, J. A. (2019). Neoliberal globalisation and resistance from below: Why the subalterns resist in Bolivia and not in Ghana. Routledge.

- Ayelazuno, J. A., & Mawuko-Yevugah, L. (2020). Kwame Nkrumah’s political economy of Afirca. In S. Oloruntoba & T. Falola (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of African political economy (pp. 171–192). Palgrave.

- Bezuidenhout, A., & Kenny, B. (2000). The language of flexibility and the flexibility of language: Post-apartheid South African labour market debates. Sociology of Work Unit.

- Bilotti, E. (2015). From Keynesian consensus to Washington non-consensus: A World-systems interpretation of the development debate. Review (Fernand Braudel Centre), 38(2), 205–218.

- Birchfield, V. (1999). Contesting the hegemony of market ideology: Gramsci’s ‘good sense’ and Polanyi’s ‘double movement. Review of International Political Economy, 6(1), 27–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/096922999347335

- Bond, P. (2005). Gramsci, Polanyi and impressions from Africa on the social forum phenomenon. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 29(2), 433–440. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2005.00596.x

- Bond, P., & Mottiar, S. (2013). Movements, protests and a massacre in South Africa. Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 31(2), 283–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/02589001.2013.789727

- Brown, D. (2011). The Polanyi-Stanfield contribution: Reembedded globalization. Forum for Social Economics, 40(1), 63–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12143-010-9066-5

- Burawoy, M. (2003). For a sociological Marxism: The complementary convergence of Antonio Gramsci and Karl Polanyi. Politics & Society, 31(2), 193–261. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329203252270

- Burawoy, M. (2010). From Polanyi to Pollyanna: The false optimism of Global Labour Studies. Global Labour Journal, 1(2), 301–313. https://doi.org/10.15173/glj.v1i2.1079

- Cammack, P. (2004). What the World Bank means by poverty reduction, and why it matters. New Political Economy, 9(2), 189–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/1356346042000218069

- Chang, H. J. (2010). How to ‘do’ a developmental state. In O. Edigheji (Ed.), Constructing a democratic developmental state in South Africa – Potential and challenges. Human Science Research Council Press.

- CONCORD. (2015). The EPA between the EU and West Africa: Who benefits? Coherence of EU policies for development. S. Jeffreson. Retrieved September 13, 2020, from https://library.concordeurope.org/record/1589/files/DEEEP-PAPER-2015-045.pdf

- Dale, G. (2016). Reconstructing Karl Polanyi. Pluto Press.

- De Witte, M. (2018). Pentecostalism and politics in Africa. In A. Afolayan, O. Yacob-Haliso & T. Falola (Eds.), Buy the future: Charismatic Pentecostalism and African liberation in a neoliberal world (pp. 65–85). Palgrave.

- EPA Monitoring. (2018). South African and Ghanaian poultry industries to join forces against EU dumping of poultry parts. EPA Monitoring. Retrieved September 15, 2020, from https://epamonitoring.net/south-africa-and-ghanaian-poultry-industries-to-joint-forces-against-eu-dumping-of-poultry-parts/

- EPA Monitoring. (2019). EU formally challenges application of SACU safeguard duties in the poultry sector. Retrieved September 15, 2020, from https://epamonitoring.net/eu-formally-challenges-application-of-sacu-safeguard-duties-in-the-poultry-sector/

- Eshun, G., Agbadze, P. E., & Asante, C. (2014). Agrotourism, entrepreneurialism and skills: A case of poultry farms in the Kumasi metropolis. Ghana. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 3(2), 1–10.

- European Commission. (2017a). Interim economic partnership agreement between Ghana and the European Union: Factsheet. European Commission. Retrieved September 15, 2020, from https://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2017/february/tradoc_155314.pdf

- European Commission. (2017b). Stepping stone economic partnership agreement between Ghana, of the one part, and the European Community and its member states, of the other part. European Commission. Retrieved September 15, 2020, from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=uriserv:OJ.L_.2016.287.01.0003.01.ENG

- Fanon, F. (1961). The wretched of the earth. François Maspero.

- Fine, B., & Saad-Filho, A. (2014). Politics of neoliberal development: Washington Consensus and post-Washington Consensus. In H. Weber (Ed.), The politics of development: A survey (pp. 154–166). Routledge.

- Gonzalez, Y., Dijkxhoorn, Y., Koomen, I., van der Maden, E., Herms, S., Joosten, F., & Mensah, S. (2016). Vegetable business opportunities in Ghana: 2016. The Ghana Vegetable Programme.

- Goodwin, G. (2018). Rethinking the double movement: Expanding the frontiers of Polanyian analysis in the Global South. Development and Change, 49(5), 1268–1290. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12419

- Harris, K., & Scully, B. (2015). A hidden counter-movement? Precarity, politics and social protection before and after the neoliberal era. Theory and Society, 44(5), 415–444. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-015-9256-5

- Hodgson, G. (2017). Karl Polanyi on economy and society: A critical analysis of core concepts. Review of Social Economy, 75(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/00346764.2016.1171385

- Interview A. (2017). Interview with poultry farmer. April 2017.

- Interview B. (2017). Interview with supplier to tomato sector. March 2017.

- Interview C. (2017). Interview with official in farmers’ association. March 2017.

- Interview D. (2017). Interview with poultry farmer. March 2017.

- Interview E. (2017). Interview with civil society stakeholder. March 2017.

- Interview F. (2017). Interview with official in farmers’ association. March 2017.

- Interview G. (2017). Interview with civil society stakeholder. March 2017.

- Interview H. (2017). Interview with poultry farmer. April 2017.

- Interview I. (2017). Interview with poultry sector stakeholder. March 2017.

- Interview J. (2017). Interview with poultry farmer. April 2017.

- Interview K. (2017). Interview with tomato farmer. April 2017.

- Interview L. (2017). Interview with poultry sector stakeholder. April 2017.

- Interview M. (2017). Interview with tomato farmer. March 2017.

- Interview N. (2020). Interview with civil society stakeholder. January 2020.

- Interview O. (2017). Interview with agricultural stakeholder. April 2017.

- Interview P. (2017). Interview with civil society stakeholder. April 2017.

- Interview Q. (2020). Interview with agricultural stakeholder. January 2020.

- Interview R. (2020). Interview with trade unionist. January 2020.

- Interview S. (2017). Interview with poultry farmer. April 2017.

- Interview T. (2017). Interview with tomato market seller. April 2017.

- Interview U. (2017). Interview with civil society stakeholder. April 2017.

- Krow, A. (2019, December 6). Farmers matter so much to John Mahama and the NDC. Modern Ghana. Retrieved September 11, 2020, from https://www.modernghana.com/news/972152/farmers-matter-so-much-to-john-mahama-and-the.html

- Kusi, L., Agebeblewu, S., Anim, I., & Nyarku, K. (2015). The challenges and prospects of the commercial poultry industry in Ghana: A synthesis of literature. International Journal of Management Sciences, 5(6), 476–489.

- Langan, M. (2011). Uganda’s flower farms and private sector development. Development and Change, 42(5), 1207–1240. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.2011.01732.x

- Langan, M. (2013). Governing trade. In S. Harman & D. Williams (Eds.), Governing the World? Cases in global governance. Routledge.

- Langan, M. (2018). Neo-colonialism and the poverty of ‘development’ in Africa. Palgrave.

- Langan, M., & Price, S. (2015). Extraversion and the West African EPA development programme: Realising the development dimension of ACP-EU trade? The Journal of Modern African Studies, 53(3), 263–287. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X15000579

- Langan, M., & Price, S. (2020). West Africa’s cocoa sector and development within Africa-EU relations: Engaging business perspectives. Third World Quarterly, 41(3), 487–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2019.1684190

- Langan, M., & Scott, J. (2011). The false promise of aid for trade. Brooks World poverty institute working paper. University of Manchester.

- Lanz, K., Gerber, J. D., & Haller, T. (2018). Land grabbing, the state and chiefs: The politics of extending commercial agriculture in Ghana. Development and Change, 49(6), 1526–1552. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12429

- Levien, M. (2018). Reconstructing Polanyi? Development and Change, 49(4), 1115–1126.

- Levien, M., & Paret, M. (2012). A second double movement? Polanyi and shifting global opinions on neoliberalism. International Sociology, 27(6), 724–744. https://doi.org/10.1177/0268580912444891

- Mati, J. M. (2013). Antinomies in the struggle for the transformation of the Kenyan constitution (1990–2010). Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 31(2), 235–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/02589001.2013.785145

- Mawuko-Yevugah, L. (2013). From resistance to acquiescence? Neoliberal reform, student activism and political change in Ghana. Postcolonial Text, 8(3&4), 1–17.

- Nkrumah, K. (1963). Africa must unite. Heinemann.

- Nkrumah, K. (1965). Neo-colonialism: The last stage of imperialism. Panaf Ltd.

- Obeng-Odoom, F. (2012). Neoliberalism and the urban economy in Ghana: Urban employment, inequality and poverty. Growth and Change, 43(1), 85–109. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2257.2011.00578.x

- Opoku, D. K. (2010). From a ‘success’ story to a highly indebted poor country: Ghana and neoliberal reforms. Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 28(2), 155–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/02589001003736801

- Peck, J. (2013a). For Polanyian economic geographies. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 45(7), 1545–1568. https://doi.org/10.1068/a45236

- Peck, J. (2013b). Disembedding Polanyi: Exploring economic geographies. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 45(7), 1536–1544. https://doi.org/10.1068/a46253

- Polanyi, K. (2001). The great transformation. Beacon Press. (Kindle edition)

- Sandbrook, R. (2011). Polanyi and post-neoliberalism in the Global South: Dilemmas of re-embedding the economy. New Political Economy, 16(4), 415–443. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2010.504300

- Sayer, A. (2000). Moral economy and political economy. Studies in Political Economy, 61(1), 79–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/19187033.2000.11675254

- Sumberg, J., Awo, M., Flankor, D., Kwadzo, G., & Thompson, J. (2013). Ghana’s poultry sector: Limited data, conflicting narratives, competing visions. STEPS Centre. Retrieved September 14, 2020, from https://steps-centre.org/wp-content/uploads/Ghana-Poultry-online.pdf

- UN Comtrade. (2020). UN Comtrade database. Retrieved September 15, 2020, from https://comtrade.un.org/data/

- Webster, E., Lambert, R., & Bezuidenhout, A. (2008). Grounding globalization: Labour in the age of insecurity. Blackwell.

- Zayed, H. (2021). The political economy of revolution: Karl Polanyi in Tahrir Square. Theory, Culture and Society. Early Online Version.