Abstract

Despite the narrative of a globalized economy, there is no effectively working global payment system. Although there is an infrastructure that allows the transmission of data about global payments, the movement of actual money is executed indirectly, making it an incalculable endeavor. The reason is that money is not simply data, but a complex bundle of rights closely tied to the nation state. In the absence of infrastructure that reliably links payments with guarantees of the nation state, intermediaries that facilitate global payments are forced to create trust in a different way. This is only possible by occupying a highly centralized and therefore powerful position. In this article, we investigate which actors were historically able to hold such a position and how these actors are challenged by digitalization. We suggest that there are three models of payment infrastructure provision. Bank-based systems were dominant until the 1980s, but in the following decades, a second model emerged: the provision of financial infrastructure by global companies. Since the early 2000s, we see a third model: the entrance of tech-driven companies in the payment sector. We conclude that digital technologies will not necessarily solve the problems, but might in fact exacerbate them.

Introduction

When I want to transfer US$100 from the United States to the Philippines, I have two basic options: I can do this via an international wire transfer through the banking system or via a financial service provider (closed-loop system) such as Western Union or MoneyGram. If I choose Western Union, which is for smaller amounts probably the better option, I have to pay US$7 in fees and my recipient only gets US$98 converted to Philippine pesos.Footnote1 This means that I have to pay Western Union around 9 per cent of the amount I want to transfer. Even if the global average for remittances is fortunately a bit lower (6.51%) (World Bank Group, Citation2020), the costs for transferring money are still surprisingly high. What is going on here? Why is it possible to send an email almost for free that arrives at its recipient within seconds, while global payments can take up to 10 working days and cost 9 per cent of the transferred value? Is money not basically data, numbers in the balance sheet of a bank or any other financial institution that can be altered easily?

The answer to questions about the difficulties in making cross-border payments leads us right into the heart of questions about the substance of modern money and the role of nation states in its production. Ingham (Citation2004) describes money as a private-public partnership. The object of this partnership is a constant struggle between three main groups of actors: governments, the people (the taxpayers), and rentiers and their banks. At the core of this conflict lies the question, ‘What counts as money at all?’ (Koddenbrock, Citation2019, p. 9), since this question is crucial for the contemporary distribution of wealth (Pistor, Citation2019).

In this article, we claim that financial infrastructure is a mostly ignoredFootnote2 but crucial component of the puzzle of ‘what counts as money’, since only this infrastructure can execute the private-public partnership in everyday life. Such infrastructure ensures that the guarantees provided by the nation state in its own currency area are not mere promises; it links these promises to day-to-day payments in commercial bank money. This material underpinning linking payments with the promises of the nation state is absent in the global context and, therefore, cross-border payments have a very different nature than domestic payments. Through the absence of infrastructure that reliably links payments with the guarantees of the nation state, intermediaries that facilitate global payments are forced to create trust in a different way. In this article we will show how these preconditions lead to the development of powerful intermediaries in the global payment industry that are able to dictate the conditions of cross-border payments.

This article advances a simple argument: modern credit money is in its essence dependent on the institutions of the nation state, and therefore all payments across the borders of the nation state or other currency area mean jumping from one ledger system to another, from one money to another money. This entails that cross-country payments are never executed directly and therefore no frictionless global infrastructure for payments exists. The closest approximation to a global payment system can be provided only by globally acting, centralized intermediaries that are able to maintain expectations as to the temporal and spatial stability of money. This dependence on these global intermediaries for doing cross-border payments engenders specific power relations. In the past, the powerful intermediary position was taken by a small number of majorFootnote3 banks, but as they became entwined in national financial structures their position was weakened. The entry of tech-driven companies in the payment sector signals the potential for change, but does not ensure it.

Our research into the complexities of cross-border payments contributes to two streams of literature and aims to link them. The first stream follows the nascent debate about financial infrastructure as a political economy issue (Bernards & Campbell-Verduyn, Citation2019; Krarup, Citation2019; Westermeier, Citation2020). In this debate the design of financial infrastructure is associated with a wide range of topics, but three phenomena are of particular interest:

financial inclusion: at the center of these studies is the question of whether startups that provide financial services on the basis of digital technologies (fintechs) are able to promote financial inclusion, e.g. of (unbanked) people in the Global South. The results of these studies are mixed: while some scholars conclude that digital financial technologies allow some sort of agency and economic opportunity for disadvantaged communities (Rodima-Taylor & Grimes, Citation2019), other studies (Gabor & Brooks, Citation2017) find that fintech accelerates financialization as companies gain access to the consumer data of previously excluded communities.

financial stability: especially after the crisis of 2007/2008 the role of financial infrastructure for financial stability became obvious since financial infrastructure is sustained not only by centralized counterparties (Genito, Citation2019, Kress, Citation2011), but also by the provision of reliable information about financial transactions (Campbell-Verduyn et al., Citation2019).

the renegotiation of power in financial markets through infrastructure and the actors who provide it. The globalization and digitalization of the financial markets have engendered new types of actors and changed the existing ones. In examining this process, international political economy (IPE) scholars have concluded that private actors engage in providing financial infrastructure in order to shape financial markets to their own advantage (Petry, Citation2021). Other studies try to understand the struggle for power between the incumbents (banks) and the startups (fintechs) (Brandl & Hornuf, Citation2020). Westermeier (Citation2020) concludes that tech companies demote banks to providers of infrastructure, while they use financial services to gain access to data.

While previous IPE debate on financial infrastructures mainly sought to link science and technology studies or social studies of finance with IPE scholarship (Bernards & Campbell-Verduyn, Citation2019; Krarup, Citation2019), we aim in this article to link these debates with a different stream of research, namely the sociology of money (Beckert, Citation2016; Ingham, Citation2004; Carruthers & Babb, Citation1996; Dodd, Citation2014; Ganßmann, Citation2013; Mirowski, Citation1991). The combination of the two debates is immensely fruitful since infrastructure is a crucial piece in the puzzle of what counts as money. In his highly influential essay, Brian Larkin (Citation2013, p. 327) describes infrastructures as networks that facilitate the flow of goods over space. For financial infrastructures it is reasonable to add that infrastructures allow the flow of goods (money) over time (Merton, Citation1992). In the next section we argue that financial infrastructure is an essential component of maintaining the private-public partnership that constitutes modern money, since only through infrastructures can the promise of the nation state be linked across time and space.

Although for non-experts financial infrastructures might seem to be a monolithic bloc, they are actually provided by a broad range of actors and institutions. The main difference is between those focusing on the settlement of payments and those focusing on the settlement of securities. The primary focus of our article is the provision of infrastructures for payments, which is regarded as part of the critical infrastructure of a nation state equal to that of energy, water supply, food and agriculture, healthcare or transportation and is, therefore, closely linked to political regulation.

This article draws on 21 semi-structured interviewsFootnote4 with regulators and market participants such as employees of central banks, commercial banks and startups between May 2018 and December 2020, and on analysis of publications such as financial news coverage, corporate reports of the studied actors and relevant blog articles. The main goal of the interviews was to learn about the principles and mechanics behind global payments as understood by those directly involved. The interviews were carried out within of a research project on financial infrastructure with a focus on digital technologies such as blockchain.Footnote5 Inevitably there are limitations to the data: because of the topic and the involvement of economic interests, our interview partners had to be cautious in answering our questions. Wherever possible our analyses use multiple sources to triangulate the results, often going back and forth between interview transcripts and technical reports.

The article is structured as follows. The next section outlines our theoretical approach, which posits that the expectation of the stability of the value of money has a temporal and a spatial dimension. Both dimensions are affected by the globalization of financial markets, in particular payments. In the following section, we suggest that there are at least three different models of providing payment infrastructure in financial markets. Bank-based systems were the dominant model until the 1980s. In the subsequent decades, a second model emerged: the provision of financial infrastructure by an exclusive group of global companies. After discussing the impact of digital technologies on financial infrastructures, we present the third model of providing financial infrastructure: the entrance of tech-driven companies in the payments sector. We then conclude by assessing whether digital technologies and other alternatives might reduce or exacerbate power imbalances in global financial infrastructures and therefore make cross-border payments more accessible or even more exclusive.

Credit money and the role of centralized intermediaries

In this section, we present a theoretical framework to understand the role of infrastructure for modern money. We suggest that money has not only a temporal but also a spatial dimension, both of which are linked by infrastructure. Our main theoretical argument is that the private-public partnership that constitutes modern money is enabled by infrastructure. Money in capitalist societies is much more than data; it is a bundle of rights related to expectations about temporal and spatial value stability that are tied to guarantees provided by the nation state. The exchange of money is, therefore, not as simple as assumed – and this is especially true for cross-border payments. In this section we lay out the difficulties that occur in the movement of money. We do this by spelling out the different dimensions of these ‘bundles of rights’ and thus identify some key characteristics of modern money. At the end of this section we show how these different dimensions are linked by infrastructure.

In capitalist societies money is not valuable in itself, but it is treated as if it were valuable. Money is therefore essentially a relationship of trust, based on the perceived credibility of promises to pay (Beckert, Citation2016, p. 108).

The sociology of money offers heuristics that can be used to better understand the complex process of extending trust in the future value of money within larger societies (Beckert, Citation2016; Carruthers & Babb, Citation1996; Dodd, Citation2014; Ganßmann, Citation2013; Mirowski, Citation1991). The generation of trust that ensures stable monetary value has at least two dimensions: temporal and spatial. The temporal dimension reflects the phenomenon that a consumer wants to ensure that she can exchange the piece of paper she earned today for things that will also be valuable tomorrow. The second dimension of trust in money – the one far less discussed in sociological debates – concerns its spatial quality. This spatial dimension refers to the confidence that one can pay with ‘the same money’ or the same transfer technology (such as credit cards or current accounts) even just a few hundred kilometers away, or that the money one deposits will reach the desired recipient.

The temporal dimension of the stability of money

The first dimension – confidence in the future value of money – has traditionally been a subject of economics. The problem of monetary stability is usually described by economists as follows: politicians have a constant incentive to increase the money supply within a nation state by incurring debt to finance their own projects (Blanchard, Citation2017). This of course raises the price level and causes inflation in the long run. Thus, a country can potentially reduce confidence in its own currency. To escape this dilemma, at least according to monetarists, the ultimate goal is to keep price levels stable. Generally, this is attempted by creating institutions that are capable of strictly regulating the amount of money circulating and thus encouraging macroeconomic development. This particular framing of the problem explains why, when economists deal with money, the primary focus is on the money supply or the institutions that regulate that supply.

From a sociological perspective, however, it can be argued that monetary stability cannot be understood only as the result of the amount of money circulating. Instead, the creation of trust in money is the outcome of a political-economic discursive process influenced by the money supply, confidence in the interpretation of the procedures by which it is measured and the assessment of the power of monetary institutions (Beckert, Citation2016, p. 110). Thus, trust in the future value of money is the result of a complex process that has performative and political-economic aspects. The stability of a financial system is, therefore, created not only by formal rules (e.g. minimum reserve ratios, capital or security requirements), but also by the degree to which the actors are able to instill trust in the institutional settings.

Afonso et al. (Citation2014) illustrate the extent to which decisions by individual banks in the event of short-term payment bottlenecks are dependent on mutual trust. In their study of the US interbank market, the authors come to the surprising conclusion that the vast majority of these transactions are carried out within a few (concentrated) relationships. In other words, banks always lend money to (and borrow it from) the same banks, which is reflected in better prices (interest rates) since banks usually offer their preferred partners better interest rates. This finding illustrates the importance of (institutionalized) trust in financial markets: banks base decisions such as interbank lending not purely on bare numbers but on personal or institutional relations of trust, which eventually lead to lower prices. Additionally, several studies suggest that the rhetorical strategies that financial market actors (especially central bank representatives) choose in order to communicate their assessment of the current economic situation have a huge impact on financial stability (Abolafia, Citation2010; Holmes, Citation2013).

To summarize, stable trust in the future value of money is generated by the nexus that has developed over time between commercial banks and national central banks as ultimate guarantors (Ingham, Citation2004, Citation2008). This nexus acts as a centralized intermediary that is able to create the credit money that is necessary for capitalist economies and at the same time maintain the expectation of its temporal stability (Esposito, Citation2011). The interaction between private banks and state actors is crucial here, because by observing how much trust the respective other side has in individual markets, risk can be managed (Baecker, Citation2008). Despite the strong interconnectedness of the private and public sectors, there is no guarantee of a stable monetary value over time in capitalist economies because, as the ultimate guarantor, the nation state is fully liable if the promise of the future value of money becomes precarious.

The spatial dimension of the stability of money

In addition to the temporal dimension of trust in money, there is a second, far less discussed dimension: the spatial one, which refers to the expectation that one can pay with ‘the same money’ without major discounts beyond regional contexts. Scholars of economic history have extensively studied the establishment of national currencies (Helleiner, Citation2002; Tilly, Citation1989). Helleiner (Citation2002) emphasized four motivations that drove the early nation states to create territorial currencies: (1) the creation and fostering of domestic markets; (2) the desire to control the domestic money supply; (3) the wish to link currency with fiscal policy; and (4) the strengthening of national identity. The process of the establishment of national currencies, however, did not go as smoothly as expected. As scholars of anthropology and sociology of money have pointed out in multiple studies, the declaration of a currency as legal tender by a nation state does not preclude the existence of another currency (Brunton, Citation2019; Dodd, Citation2014; Zelizer, Citation1997). Consequently, currency or monetary pluralism is regarded not as an exception but as a characteristic of modern currency systems (Guyer, Citation2017; Helleiner, Citation2002). While economic sociologists emphasize the simultaneous existence of currencies that represent varying cultural meanings, anthropologists underline the social inequality dynamics that are perpetuated by currency pluralism (Luzzi & Wilkis, Citation2018; Guyer, Citation2012, Citation2017). In countries with soft currencies, for example, the functions of money have become disaggregated: while soft currencies were only used as a medium of payment or exchange, hard currencies such as the US dollar and euro became the unit of account as well as the store of value.

Alongside their critique of a single uniform national currency, anthropologists in particular have long studied the plurality of economic spheres and currencies and the difficulties of transferring values from one sphere to the other (Barth, Citation1967; Sillitoe, Citation2006). For our purposes the most relevant finding of these classical approaches is the recognition that the conversion of money from one sphere to another sphere is never a simple and frictionless process (Maurer, Citation2012). Contrary to the common assumption, this is true not only for tribal society but also for modern capitalist societies. To understand this problem let us use a simple example: Imagine I received a €50 gift certificate for one clothing store for my birthday, and I am not very fond of this particular shop. The problem is now that I cannot use my €50 voucher at any other store except the one named on the certificate. I cannot even go to the shop and exchange the voucher for cash. My only solution would be to find someone via the internet or just by asking someone in front of the store who is willing exchange my voucher for cash. This option probably involves a minor discount and major transaction costs.

In the next section, we describe the complexities of cross-border payments in greater detail. At this point it is important to understand that payments across national borders are never a frictionless process, since they entail jumping from one ledger system to another and, even more difficult, from one money to another money.

Infrastructure: the link between the temporal and spatial dimensions of money

As we have suggested, trust in money has not only a temporal but also a spatial dimension, both of which are linked by financial infrastructures. The spatial stability of money has two components: the enforcement of uniform currencies that are linked to the guarantees of the nation state and the establishment of stable systems for converting one currency to another. These tasks are performed by very different actors and require different levels of trust. In this subsection we will get to the core of the difficulties and complexities of global payments and the role of infrastructures in this process.

Before we look at the global level, however, let us use the historical study of Garbade and Silber (Citation1979) as an illustration of the difficulties in establishing even a domestic payment system. The authors describe how a national uniform currency was established in the US by building up a reliable infrastructure. They start their analysis by describing the phenomenon of domestic exchange rates which existed in the US between 1840 and 1918. The exchange rates between cities behaved much like foreign exchange rates under a gold standard, fluctuating within the limits established by the costs of shipping money (gold or currency) (Garbade & Silber, Citation1979, p. 1). This situation was highly inefficient, since huge risks and uncertainties resulted from every single transaction. The institutional innovation that enabled frictionless payment nationwide was the establishment of the Federal Reserve System (the Fed) in 1914. One major component of the Fed was the establishment of the Gold Settlement Fund, which enabled the member banks to settle their reciprocal claims with central bank money. The costs of shipping gold between the various banks were reduced to zero, and therefore payments at par became possible (ibid, p. 7). This case shows us how the historically developed nexus between commercial banks and the central bank as the ultimate guarantor is able to link the expectation of the temporal stability of money with the expectation of its spatial stability through infrastructure. This historical example also shows us that at the hard of modern payment systems stands a publicly provided infrastructure. This public infrastructure, however, has to be accompanied by another type of infrastructure: the networks of the commercial banks. While the infrastructure provided by central banks is able to actually move money, the infrastructure of commercial banks represents the calculative basis of payment systems. (We will lay out this distinction in the next section).

But what exactly are the challenges in building and maintaining a reliable and frictionless payment infrastructure? Krarup (Citation2019) pointed out that we find a paradox at the heart of most issues surrounding financial infrastructures: the basis for (perfect) markets is an infrastructure that enables transactions with as little friction as possible, i.e. without costs and risks. Markets as one of the fundamental institutions of capitalism function precisely because fragmented actors come together to compete. However, these decentralized encounters are based on a (financial) infrastructure that must be as frictionless as possible, i.e. centralized. The first challenge in setting up financial infrastructure is consequently that competing companies must establish institutions that are able to uphold their trust in one another. Second, all actors involved must jointly provide the technological infrastructure capable of handling such a complex operation and enforce universal standards such as accounting systems. The problems that typically arise in this context are similar to those that generally come up in the provision of public goods: on the one hand, suboptimal incentive structures, which systematically lead to undersupply in the case of the private provision of a public good (Atkinson & Stiglitz, Citation2015); and on the other hand, the occurrence of strong network effects which reinforce concentration tendencies (Katz & Shapiro, Citation1994). Traditionally, the advice for industries with these tendencies has been that the state should be responsible for their provision. However, unlike other industries with a similar structure, such as telecommunication providers or providers of public utilities, the provision of financial infrastructure was only occasionally managed solely by the nation state. Instead we find different models of providing financial infrastructure involving public and private actors.

But why does the primarily private provision of infrastructure work in the finance sector, while it fails in other industries? One key reason for this might be that payment infrastructure can be provided as a club good (Samuelson, Citation1954) such that non-paying actors can be excluded. It is important to understand that this ‘club’ of commercial banks that provide infrastructure is deeply dependent on the close cooperation between private actors and state actors that provide oversight over the financial infrastructure as well as settlement infrastructures, which connect the privately provided infrastructures (Allen et al., Citation2006; Evans & Schmalensee, Citation2004).

As we have shown, the private-public partnership that constitutes modern money is executed through public infrastructure, which is reliably linked to the infrastructure of networks of commercial banks. These infrastructures, which are run by central banks, are able to link day-to-day payments with the guarantees of the nation state by providing an infrastructure that allows banks to settle their reciprocal claims with central bank money. The result is a payment system that works very efficiently in terms of time- and cost-saving for both consumers and vendors.

However, this is only true for domestic payments, since cross-border payments are of a very different nature. On the global level the possibility to settle the reciprocal claims of banks through a public infrastructure with central bank money is naturally absent. The establishment of stable infrastructures that are able to execute cross-border payments by converting one currency into another currency is much more complex. The trust of all participants in payment infrastructures that emerge naturally in the domestic context is built on the basis of the fact that central bank money is the safest possible asset; for cross-border transactions this trust has to be produced by other means. In the next section we will see that only a few globally acting players (major banks) have been able to replace trust in the nation state with trust in their own institutions.

The globalization of payment systems

We began this article with the claim that money in capitalist societies is not simply a number in a ledger, i.e. data; rather it entails a bundle of rights linked to expectations of temporal and spatial stability which are tied to and can only be guaranteed by the nation state. In the previous subsection, we demonstrated how this complex bundle of rights can be transferred through public infrastructure in domestic payments. However, because of its links with the nation state, this bundle of rights cannot be exchanged as such when it comes to cross-border payments; it must first be transformed. In the next subsection see how private and public actors manage this transformation via infrastructure.

Although payment systems are fundamental components of modern capitalism, these infrastructures are opaque. And although we use these services almost every day, we actually have little idea which actors and processes are involved when we transfer money from one bank account to another or from our bank account to a vendor’s. By the end of this subsection we will understand why money is not simply data on a balance sheet. Over time, three models emerged successively – but continue to coexist – in which different types of powerful intermediaries established an infrastructure that is able to transfer money across borders. We discuss the first two models in this section and the third separately.

Bank-based systems

The fundamental task of the financial infrastructure is the processing of reciprocal claims. Although for the sake of simplicity the process of settling reciprocal claims is usually referred to as ‘clearing’, it is more complex than this. Technically only the first step is actually clearing: all reciprocal claims are set off against each other (netting), and at the end of a fixed period only the differences are credited or debited. Thus, ‘clearing’ refers solely to the process of the calculation of the amount that each involved party has to pay or receive. The second step then is called settlement and involves the actual movement of values.

The first clearing houses were established in Great Britain in the 18th century (Millo et al., Citation2005) when several banks began to cooperate with each other and accept claims from other banks (Norman et al., Citation2014). The advantages of clearing houses for the financial sector, as well as for society, are twofold. Firstly, clearing houses significantly reduce the transaction costs for all participating actors. Because clearing houses establish a contractually defined exchange situation for all involved actors, transaction partners do not have to renegotiate individual conditions for every transaction. Clearing houses are the backbone of all modern financial systems, guaranteeing that financial transactions run more smoothly. Beyond efficiency gains, clearing houses have a second advantage: their impact on financial stability. Clearing houses act as central counterparties (CCP), which means that they assume guarantees for their members in the event of default. To be able to do this properly, the clearing houses require large commitments from their members, usually in the form of reserves deposited with the central bank. In addition, the members are often subject to the regulations of the central counterparty (Interview 14). In this way, the central counterparties not only minimize the individual members’ risk, but also reduce the systemic risk of the entire financial sector by homogenizing the individual credit risks, as all members are jointly liable for losses (Genito, Citation2019; Kress, Citation2011).

Settlement usually is done with central bank money,Footnote6 since this is the safest possible asset. These services are generallyFootnote7 provided by central banks; via these infrastructures, it becomes possible to link monetary policy with actual payments (Interview 21). At this point it might become clearer how infrastructures link the expectation of the temporal stability (the promise to consequently limit the money supply and thereby retain its value) with the spatial stability of money: the central bank as an institution of the nation state realizes its guarantees through payment systems. The transfer of money is therefore not completed via the simple exchange of data, since this data has to be linked to a bundle of (property) rights that originates in the guarantees of the nation state.

The relationship between privately and publicly provided infrastructure as well as the technical details of payment infrastructures differs slightly between nation states (Tilly, Citation1989). In Germany for example, most payments are cleared in so-called giro networks, which are owned by the three banking groups (savings banks, credit cooperatives, and commercial banks). Bilateral clearing occurs between these giro networks, and the Bundesbank provides additional infrastructures for settlement (Bank for International Settlements BIS, Citation2012, p. 181). In the US, we find a similar structure: payments are processed by seamlessly connected infrastructures of private and public providers. The majority of clearing is done by the association of private banks, the Clearing House Interbank Payment System (CHIPS), and settlement is provided by Fedwire, which is a system run by the Fed.

Global companies with roots in the banking system as global intermediaries

As we have explained, an effective (domestic) payment system depends heavily on the collaboration of the nationally organized networks of commercial banks and infrastructures that are run by central banks. This close collaboration of private and public actors through payment infrastructures contributes to the maintenance of the expectation regarding the stability of money.

The complexity and the risks of cross-border payments, however, are higher than those of domestic payments because of the absence of a uniform currency at the global level. Although this statement sounds banal, it explains the majority of difficulties associated with cross-border payments. Earlier we saw that the transformation of one money into another money is not a simple and frictionless process. This is especially true for cross-border payments, since money is not only data but a bundle of rights that is tied to the guarantees of the respective nation state. This bundle of rights cannot be exchanged as such, since the essence of global transactions is that they leave the borders of the nation state. The only possibility is, therefore, that a powerful intermediary is able to bridge this gap.

We have already seen that payment systems are predominantly based on national institutions. From the 1970s onwards several US-based companies challenged the national frameworks for providing financial infrastructures (see ). Due to the elimination of discounts in the Federal Reserve’s check clearing system and the rising loyalties of merchants (Stearns, Citation2011, p. 28), among other reasons, the US banking industry began to establish an alternative infrastructure to clear retail payments via credit card systems. Credit card companies provide technical and organizational infrastructures that are able to connect competing banks and enable them to exchange data (Evans & Schmalensee, Citation2004; Stearns, Citation2011). Already in the 1970s the credit card companies expanded their territory outside of the US to the European and the Asian markets.

Table 1. Three models of provision of payment infrastructures.

However, it is important to understand that credit card companies, as well as other companies such as the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT), do not supersede the nationally based infrastructures; rather, they are deeply dependent on them. SWIFT, a company that emerged from the association of commercial banks, provides an infrastructure for banks to send and receive messages about financial transactions (Scott et al., Citation2017; Dörry, Citation2014). Credit card companies provide international clearing arrangements, which means they provide the data that allows settlement, but the actual movement of money is carried out by a few major settlement banks. The role of these banks cannot be underestimated. For example, the entire settlement process for Visa (the largest credit card company) is done by Chase Manhattan Bank, which technically becomes a correspondent bank or handles the transactions through its subsidiaries.

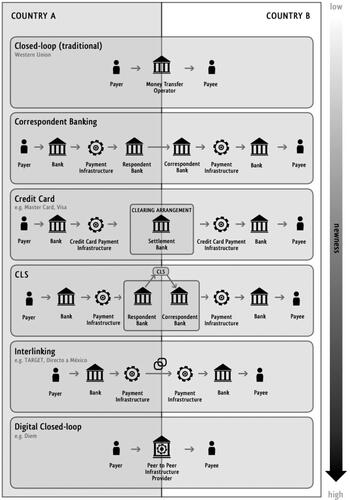

To understand how the cross-border movement of values (foreign exchange, or FX, transactions) works, let us look at some technical details (see ). Banks handle their international transactions via correspondent banks or via their subsidiaries. Correspondent banking is a bilateral agreement between two banks in different countries by which one of them provides services to the other by holding an account (nostro or vostro account) owned by the respective other bank (see ).

Figure 1. Stylized overview of (back-end) cross-border payments.

Source: own representation based on Bank for International Settlements BIS (Citation2018), p. 14.

These agreements enable the respondent bank in Country A to participate in the payment systems of Country B. There are only a few major banks that provide these services globally. One type of correspondent banking is the so-called ‘in-house’ arrangement, which is typically exercised by large banks with branches or subsidiaries in different countries. Through these subsidiaries, the respective bank is able to participate in a number of domestic clearing and settlement systems and is therefore able to route its cross-border payments through its in-house network. The cross-border transfer of money through in-house networks is done not only by financial institutions but also by large globally acting companies (Mehrling, Citation2010)

There are at least two reasons why FX settlements are especially risky. Firstly, while the settlement of domestic transactions is typically done with central bank money (the safest possible asset), the settlement of FX transactions involves commercial bank money. Secondly, the time lag between a currency payment and receipt of the currency being bought creates a risk exposure for the selling party: the risk that the delivery is late (liquidity risk) or in the worst case does not occur at all (credit risk). Although these types of risk also exist in domestic transactions, the risk that goes along with FX transaction settlements is higher (Kos & Levich, Citation2016) since the trading partners operate in different time zones and under different jurisdictions with their respective regulations and standards.

Although these correspondent banks and traditional closed-loop systems are not able to establish a completely frictionless global payment infrastructure, they are the only players that are able to act as global intermediaries – fulfilling the expectation of the spatial stability of money by being able to take the aforementioned risks and to benefit from the guarantees of temporal stability of the nation states of the Global North. However, this service comes with a price: the provision of infrastructure by an oligopoly of private companies. As we previously discussed, the provision of infrastructures develops strong network effects. In this perspective, the institutional setting of networks of commercial banks supported and complemented by the central bank can be understood as a kind of a built-in protection against concentration tendencies, since in smaller, manageable settings in which all actors can watch each other, financial infrastructure can be provided as a club good. In the global context, however, the regulative authority and the settlement infrastructures provided by the central banks are missing, and therefore, the rise of a few major players is structurally predetermined, since credit card companies and major settlement banks deeply depend on the national networks to ensure their positions of power.

Since the late 1990s, at least two innovations have enhanced the speed and lowered the cost of cross-border trades between the countries of the Global North. To reduce the risk exposure of cross-border payments, a network that consists of around 70 financial institutions established a settlement system (see ) for cross-border payments: CLS (continuous linked settlement). While the settlement provided by central banks is done with central bank money, the settlement in the CLS system is executed by the CLS Bank with a ‘payment vs. payment’ system that reduces the risk exposure for the involved parties. However, CLS only settles in 17 currenciesFootnote8 of countries of the Global North as well as some emerging economies. FX transactions with minor or exotic currencies are still only possible via correspondent banks, and therefore even more incalculable and hence expensive.Footnote9

Traditional closed-loop systems (or money transfer operators) such as Western Union have their own proprietary, quite opaque network of banks, exchange bureaus, post offices, and other intermediaries – like retail outlets, cell phone centers, travel agencies, drug stores, and gas stations – to deliver remittances (International Monetary Fund, Citation2009, 9).

In the Eurozone and a few other regions,Footnote10 we see a second innovation emerging from attempts by nation states to bridge the national financial infrastructures and build interlinking models (see ). In the context of the integration of the European capital market, one major step was the harmonization of the providers of financial infrastructure, which was done through TARGET 2 (Trans-European Automated Real-time Gross Settlement Express Transfer System) that was implemented between 2006 and 2017. The core of the Target system is a platform which allows all central banks of the euro system to settle their euro payments in real time. The Single Shared Platform is operated by the three major central banks: France (Banque de France), Italy (Banca d’Italia) and Germany (Bundesbank). Although the Bank for International Settlements (Bech et al., Citation2020) sees great promise for the interlinking model, global companies continue to dominate infrastructure provision.

Although there is a lot of variation, ultimately all possibilities of transferring money across borders have one element in common: the actual movement of money (not only the transmission of information about payments) is executed by a small and exclusive group of large banks. In the next section we will ask whether this oligopolistic structure is threatened by the entrance of tech-driven companies in the payment industry.

The entrance of tech-driven companies in the finance sector

Thus far, we have discussed two different models of providing financial infrastructure for payments that currently coexist (see ). On the national level, the provision of financial infrastructure by bank-based systems and the central banks dominates. On the international level, we see that transnational (credit card) companies collaborate with major banks that provide financial infrastructure for cross-border payments. In this section, we explore whether new emerging actors might change these arrangements.

The new model of the provision of financial infrastructure was driven by two mutually reinforcing factors. The first factor is the second wave of digitalization in the financial sector, which was heralded by the emergence of fintechs and the advent of new digital technologies such as blockchain. This technological development was reinforced by a second factor: the promotion of these technological developments through legislation and regulation.

In the European Union (EU), we see a massive regulatory push to disaggregate the value chain of the payment sector by promoting digital technology (Interviews 11 & 16). This process is closely tied to the revision of the 2015 directive on payment services (PSD2), which aimed to open up the market for payment services. The core of this directive is that banks are required to grant other providers access to their customers’ account data. As a result, the business models of the providers of digital payment systems were strengthened. The initial aim behind this initiative was to challenge the cartel of credit card companies from the European side (Stiefmüller, Citation2020). Guaranteed access to consumer data should foster competition in the market for payment services and should at best trigger the foundation of a European equivalent to PayPal. This initiative of the European Commission was almost exclusively motivated by competition law and supply-side concerns, but comes with a price tag: the limitation of data protection and the potentially related violation of privacy (Stiefmüller, Citation2020, p. 299). The exclusion of data protection concerns in the PSD2 directive is presumably due to fact that the EU regulators want to establish an economic area that can compete with the US to spawn innovation.

Both trends, the wave of digitalization in the financial sector and the regulatory push to promote these digital technologies, made the financial sector attractive for new types of players: startups and, of course, big tech companies such as Apple, Amazon and Facebook. The payment sector is particularly interesting for these companies because it produces highly attractive raw material: transactional data. Westermeier (Citation2020) described this process as platformization of financial transactions. The big tech companies aim to integrate payment systems in their platforms to gain access to this highly valuable transactional payment data and to increase the time customers stay on their platforms. However, the key question is whether this development affects the oligopolistically provided financial infrastructure that now executes global payments. The answer at this point in time is far from clear. Generally, we see at least two different developments.

The first and more widely known development is the transformation of the front endFootnote11 of banking by tech-driven companies. This means that authorization of payments or loan applications can be done without using the interface of banks. These new players use digital technologies that initiate payments or access the account information of customers and make it available for third-party providers on behalf of the customer, for example, to check creditworthiness as part of an online loan application. The back end of banking, which means clearing and settlement, however, largely remains unchanged – as confirmed by several of our interview partners.

The first company working this way on the front end was PayPal, founded in 1998.Footnote12 It was over a decade later when the large wave of startup formations in the payment sector began. As of 2021, the most successful actors in this field are startups such as Klarna or iZettleFootnote13 as well as the big tech companies that provide financial services such as Apple Pay and Google Pay. The end of the 2010s saw a consolidation in the market for payment service providers, but it is far from clear who will be the market leader in this segment. However, we know from the example of the credit card companies that the market of payment providers develops strong network effects and, therefore, the further consolidation of the market is very likely.

In addition to tech-driven companies that provide financial services without becoming banks themselves, we can identify a second, much more radical strategy: the (almost) complete detachment of financial services from banks via the establishment of closed-loop systems. Although digital closed-loop systems emerged only recently, the principle is much older. More traditional remittance companies such as Western Union work on the same principle but require a physical presence in every jurisdiction. By contrast, digital closed-loop systems are based on digital currencies which are created by the networks themselves. The first attempt to establish such a digital closed-loop system for cross-border payments was made by Ripple. On the basis of distributed ledger technologyFootnote14 Ripple creates its own currency (XRP), which is used for settlement (Qiu et al., Citation2019). While we have seen that the companies that emerged from banking networks such as SWIFT or credit card companies only provide infrastructure that transmit information about payments, digital closed-loop systems are able to provide infrastructure that is able to move money. However, rather than actual currencies that are legal tender, these systems move their own digital currencies that eventually have to be exchanged in the currency of the respective country.

Closed-loop systems (see ), in which one company decides on standards and processes, are easier to establish than are bank-based systems (Interview 17), in which the need for group consent can result in collective action problems. But the risks associated with digital, proprietary closed-loop systems are evident. First, since these systems were established outside the highly regulated state–bank nexus, the lack of supervisory oversight might fail to identify shortcomings in risk management. The second concern is much more fundamental. Digital closed-loop operations may drive fragmentation through non-compatible payment systems within an economy. This could also lead to the dominance of one or only a few private providers of payment infrastructures, not unlike the current analog system (Bank for International Settlements BIS, Citation2018, 25).

While Ripple’s ultimate goal is to revolutionize the global interbank market by convincing banks to join the Ripple network, we see initiatives from the big tech companies in the US to establish digital closed-loop systems for end users. In one of the best-known examples, Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg announced plans to launch the digital currency Diem (originally called Libra) in cooperation with other companies.Footnote15 Although Diem is based on a blockchain, it differs significantly from other cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin. In contrast to the majority of the existing cryptocurrencies, Diem is based on a permissioned blockchain, where only accepted members can participate. A second important difference is that the Diem blockchain does not create new value. Instead, the value on the Diem blockchain is fixed to that of existing currencies (so called stablecoinsFootnote16), and all values are fully backed by money that is deposited into Diem Reserve. According to its own statements, the Reserve exclusively relies on high-quality liquid assets or assets that can be easily converted into high-quality liquid assets.Footnote17 Contrary to its own claims, however, we argue that Diem is not a cryptocurrency but a hybrid between a bank, an equity fund and a currency directed by a private company.

Although China is outside of the scope of our analysis it is important to note that while most projects of western tech companies are still under development, these capabilities are already developed in China and other Asian countries. For example, a handful of companies in China, such as Alibaba’s Alipay or Tencent’s WeChatPay, provide digital infrastructures that link social media, commerce and banking, which work almost independently from banks. Next to these initiatives in the private sector, the efforts of China’s central bank to provide a digital payment version of China’s fiat currency – the Renminbi – are much further developed than comparable projects in the U.S. or Europe (Gruin, Citation2019, Citation2021).

While Facebook tries to enter the financial sector with high visibility and publicity, another big tech actor has quietly withdrawn from its intentions to become a bank itself. In 2011, Amazon started its lending service for suppliers and small businesses.Footnote18 At the end of 2019 Amazon had outstanding small business loans of more than $863 million on its own balance sheet.Footnote19 Amazon’s financial products were not quite as successful as hoped, with growth rates slowing significantly after launch. One countermeasure was collaboration with banks: in February 2020 Amazon announced a deal with Goldman Sachs that would help mitigate the risks that arise out of small business credit. These examples show that the establishment of financial infrastructure is not as simple as the big tech companies might have thought.

Here we have suggested that the vast majority of attempts by tech-driven companies to transform the payment industry only affects the front end of banking and therefore leaves the role of major banks untouched. There are, however, a few attempts by tech-driven companies to establish digital closed-loop systems, which are based on distributed ledger technologies. Whether digital closed-loop systems indeed imply a disintermediation of the financial system remains unclear. While Ripple eventually turned to providing more efficient technology for the existing correspondent bank relations (Rella, Citation2019), Facebook’s Diem still hopes to detach payments from the traditional banking system.

Conclusion

Despite the narratives touting a globalized economy, one of the most surprising findings of our analysis is that there is no effectively working global payment infrastructure. Although there is an infrastructure that allows the frictionless transmission of data regarding cross-border payments, the actual movement of money only happens indirectly and is, therefore, always a risky and complex endeavor that makes it inaccessible or highly costly for most people and businesses. The reason is that money is not only data or a simple written entry in a ledger, but a complex bundle of rights that are closely tied to the nation state or currency area. This is true since modern money is constituted by a private-public partnership between the rentiers and their banks, the nation state and the people.

In this article we have shown that the private-public partnership that constitutes modern money is made possible only via a nationally bounded financial infrastructure. While at the national level the nexus of commercial banks and the central bank as an ultimate guarantor is able to link the expectations of the temporal stability of money with its spatial stability through such infrastructure, this is not possible on the global level. The bundle of rights tied up with these expectations and guaranteed by the nation state cannot be exchanged outside the nation state’s or currency area’s borders, certainly not without friction. The only actors that can provide anything close to a frictionless global payment infrastructure are a small network of correspondent banks. These banks are able to instill enough trust in their institutional collaborations by maintaining well-stocked accounts with each other so that they can involve commercial bank money (rather than central bank money) as a settlement asset and, therefore, manage the attendant higher risks and navigate the increased complexity of cross-border payments.

It is important to understand the uniqueness of this institutional setting, since there is currently no alternative for sending money globally. The network of correspondent banks is the only reliable arrangement to move money across borders, with the exception of a hand full of opaque closed-loop systems such as Western Union. This service, however, comes with a price tag: a club of a few major banks which collaborate with each other and therefore are able to dictate the conditions of cross-border payments.

The power of this club of major banks does not affect all actors in the same way. Powerful actors such as global companies are able to establish private solutions to bypass this problem via corporate treasury functions through their subsidiaries. However, consumers and small businesses that import and export goods and services, and migrants who are dependent on the transfer of small sums of money mainly from countries in the Global North to countries of the Global South (remittances), are disproportionately affected by this problem.

While we see some progress in facilitating payments between countries in the Global North (especially interlinking and CLS), payments in or between countries of the Global South are still especially costly. The exclusive nature of the global payment infrastructure is more evidence of the situation highlighted by social science scholarship in recent decades: Infrastructures are never neutral; they maintain the power relationships which are inscribed in their construction (Appel et al., Citation2018). The global payment infrastructures provided by major banks therefore mirror the global power structure with a few major currencies of industrial countries and the dollar as the unchallenged leading currency.

So far, digital technology, especially blockchain, has not challenged the concentration of power in only a few major players that are able to provide global financial infrastructure; instead it appears to strengthen existing intermediaries. This result is in line with other results from IPE scholarship. For instance, Rella (Citation2019) and Maurer (Citation2016) show that blockchain does not weaken the trend of the formalization and capitalization of remittances (e.g. by promoting peer-to-peer networks). Campbell-Verduyn and Goguen (Citation2019) and Beaumier and Kalomeni (Citation2021) show that blockchain was not able to fulfill its promise of making trusted third parties redundant by creating trust purely through an algorithm. Instead, traditional financial firms provide blockchain-based networks that have little in common with the original idea of blockchain and therefore maintain their role as trusted third parties.

The resistance of the banking sector to disruptive changes driven by digital technology shows that the establishment of financial infrastructure is not as simple as the big tech companies might have thought. Banks and their organically grown infrastructures seem to have some advantages that cannot be easily copied by tech-driven companies. The reason for this might point to the characteristics of infrastructure, which are not purely technological arrangements, but as such evolving socio-technical systems which combine human and non-human elements for the provision of key functions in global finance (Bernards & Campbell-Verduyn, Citation2019).

The only project that might eventually prove this statement wrong is Facebook’s digital closed-loop system Diem, which goes beyond the front end of payments. However, it is currently unclear how Diem will actually function. Following Facebook’s grandiose announcements in July 2019, the Diem project lost its initial revolutionary spirit. Due to the massive protests in both the US and Europe, the initial design of Diem was changed.Footnote20 In November 2020, the Diem Association announced a much more modest version: a single coin backed one-for-one by the US dollar; the other currency-backed coins and the composite would be rolled out at a later time point. The regulatory framework that would govern Diem at this point remains undetermined. Next to the concerns about the creation of money by a non-state actor, Diem has faced criticism for pegging the Diem one-for-one to the US dollar. The Diem Reserve is a great source of concern for regulators. Opponents are afraid that that the Reserve is a new form of shadow banking, since it means that the safekeeping of huge amounts of money will be beyond the balance sheets of the much more strictly regulated banks. In the US, a legislative bill was introduced in the Congress that called for regulating the issuers of stablecoins as if they were banks.

The question of whether banks or tech companies can establish digital solutions to the provision of more inclusive global payment infrastructures remains unanswered. However, our research suggests that only powerful actors are able to build up enough trust to settle reciprocal claims with commercial bank money or, in the case of CLS and Ripple, with tokens they have created by themselves. The only possible alternative to powerful global companies (be it a club of major banks or a big tech company) that maintain the infrastructure of global payments is that nation states become more invested in the construction of settlement infrastructures, as we have seen in the few attempts of the establishment of interlinking two settling infrastructures by the central banks of two countries.

The attempts of central banks to introduce digital central bank currencies might lead in the right direction. For example, the introduction of the Digital Euro might open up the possibility for participants outside of the EU to have access to central bank money. This would mean a big step in creating a global infrastructure that is actually able to move money and not only data. The consequences of an increase in euro-denominated assets outside of the EU, on the other hand, are completely unpredictable at this point. It is, therefore, not clear if this step is really desirable or whether it would ultimately break the exclusivity of the current infrastructure and make cross-border transactions more frictionless and less costly for everyone.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (87.1 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Barbara Brandl

Barbara Brandl earned her PhD at LMU Munich and is currently Professor for Sociology with a focus on organization and economy at Goethe University/Frankfurt.

Lilith Dieterich

Lilith Dieterich is a research assistant at Goethe University/Frankfurt.

Notes

1 Based on the prices published on https://www.westernunion.com/us (prices for the option ‘pay cash’ in a Western Union store). The prices for payments via bank account are lower, while payments via credit card are much higher. In addition to the transfer fee, Western Union makes money form currency exchange. The exchange rate Western Union charges differs from the actual exchange rate, which we retrieved from https://www.exchange-rates.org/ on February 5, 2021.

2 An exemption is Maurer (Citation2012).

3 For the definition of major banks, we refer to the list of systemically important banks, which is published and updated by the Financial Stability Board.

4 See Appendix 1.

5 “Technology instead of institutions? The blockchain technology as a threat to the banking system” funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG).

6 In every economy there exists some kind of tiering, which means that not all banks are direct participants in a payment system. While top-tier banks settle with central bank money, low-tier banks use instead the services of top-tier banks to make and receive payments from other banks. For example, in the most important German settlement system (RPS provided by the German Bundesbank), some 75% of the financial institutions are direct participants. In Fedwire, the most important settlement system in the US, the degree of tiering is mixed and ranges between 25% and 75% (Committee on Payments & Market Infrastructures, Citation2003, 90 ff).

7 A list of exemptions can be found here: Committee on Payments & Market Infrastructures, Citation2003, Annex 3, Table C.

8 US dollar, Canadian dollar, Mexican peso, Israeli shekel, South African rand, Danish krone, euro, Norwegian krone, Swedish krona, Swiss franc, pound sterling, Australian dollar, Hong Kong dollar, Japanese yen, Korean won, New Zealand dollar and Singapore dollar.

9 Recent studies have shown that more and more banks have withdrawn from countries where governance and controls on illicit financing were poor. Rice et al. (Citation2020) show that the number of correspondent banks fell by 20% between 2011 and 2018, even as the value of payments increased. Rella (Citation2019) sees this decline as a result of de-risking strategies and shrinking revenues in cross-border payments. To better understand the reasons and circumstances certainly more research is needed here.

10 E.g.: ‘Directo a México’ was set up in 2005. It facilitates remittances from the US to Mexico by linking the Federal Reserve’s automated clearing house (FedACH) with the Mexican RTGS (Real Time Gross Settlement) (SPEI).

11 Front-end services of banks describe services that connect customers with the bank such as digital platforms to initiate payments.

12 According to company’s website: https://www.paypal.com/us/webapps/mpp/about

13 In 2018 iZettle was acquired by PayPal and in 2021 renamed Zettle.

14 Distributed ledger technologies (DLTs) are a type of database that is spread across multiple sites, countries or institutions (Government Office for Science (UK), 2016). DLTs are largely based on the same technological principles as blockchain (for differences see Voshmgir Citation2019).

15 An updated list of all members of the Diem Association (formerly Libra Association) can be found on the Diem homepage (https://www.diem.com/en-us/association). In addition to blockchain startups such as Coinbase and venture capital companies, members include tech-driven companies such as Uber and Spotify.

16 Stablecoins are tokens that are pegged to existing currencies (or a basket of currencies) and backed by collateral. The value of stablecoins is, in contrast to the highly volatile cryptocurrencies, relatively steady.

17 On the (then) Libra homepage (March 12, 2021) we found the following information about the structure of the Reserve: ‘We will require the Reserve to consist of at least 80 percent very short-term (up to three months’ remaining maturity) government securities issued by sovereigns that have very low credit risk (e.g., A + rating from S&P and A1 from Moody’s, or higher) and whose securities trade in highly liquid secondary markets. The remaining 20 percent will be held in cash, with overnight sweeps into money market funds that invest in short-term (up to one year’s remaining maturity) government securities with the same risk and liquidity profiles’.

18 Nicholas Megaw: Amazon seeks to revive its faltering loans business. Financial Times from June 14, 2019.

19 Laura Noonan: Goldman Sachs talks with Amazon to offer small business loans. Financial Times from February 3, 2020.

20 This process was possibly accelerated by the fact that traditional payment service providers such as PayPal, Master Card and Visa left the association prior to its first official meeting in October 2019.

References

- Abolafia, M. Y. (2010). Narrative construction as sensemaking: How a Central Bank Thinks. Organization Studies, 31(3), 349–367. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840609357380

- Afonso, G., Kovner, A., & Schoar, A. (2014). Trading partners in the interbank lending market. Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports No. 620.

- Allen, H., Christodoulou, G., & Millard, S. (2006). Financial infrastructure and corporate governance. Working Paper No. 316. Bank of England.

- Appel, H., Anand, N., & Gupta, A. (2018). Introduction: Temporality, politics, and the promise of infrastructure. In N. Anand, A. Gupta, & H. Appel (Eds.), The promise of infrastructure (pp. 1–38). Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781478002031-002/html

- Atkinson, A. B., & Stiglitz, J. E. (2015). Lectures on public economics (Revised ed.). Princeton Univers. Press.

- Baecker, D. (2008). Womit handeln Banken?: Eine Untersuchung zur Risikoverarbeitung in der Wirtschaft. Suhrkamp.

- Bank for International Settlements BIS. (2012). Payment, clearing and settlement systems in the CPSS countries—Volume 2.

- Bank for International Settlements BIS. (2018). Cross-border retail payments.

- Barth, F. (1967). Economic Spheres in Darfur. In R. Firth (Ed.), ASA Monograph 6, Themes in economic anthropology (pp. 149–174). Routledge.

- Beaumier, G., & Kalomeni, K. (2021). Ruling through technology: Politicizing blockchain services. Review of International Political Economy, in press. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2021.1959377.

- Bech, M., Faruqui, U., & Shirakami, T. (2020, March). Payments without borders. BIS Quarterly Review.

- Beckert, J. (2016). Imagined Futures: Fictional expectations and capitalist dynamics. Harvard University Press.

- Bernards, N., & Campbell-Verduyn, M. (2019). Understanding technological change in global finance through infrastructures. Review of International Political Economy, 26(5), 773–789. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2019.1625420

- Blanchard, O. (2017). Macroeconomics, Global Edition. (7th ed.). Pearson.

- Brandl, B., & Hornuf, L. (2020). Where Did FinTechs come from, and where do they go? The transformation of the financial industry in Germany after digitalization. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence, 3, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/frai.2020.00008

- Brunton, F. (2019). Digital cash: The unknown history of the Anarchists, Utopians, and technologists who created cryptocurrency. Princeton University Press.

- Campbell-Verduyn, M., & Goguen, M. (2019). Blockchains, trust and action nets: Extending the pathologies of financial globalization. Global Networks, 19(3), 308–328. https://doi.org/10.1111/glob.12214

- Campbell-Verduyn, M., Goguen, M., & Porter, T. (2019). Finding fault lines in long chains of financial information. Review of International Political Economy, 26(5), 911–937. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2019.1616595

- Carruthers, B. G., & Babb, S. (1996). The color of money and the nature of value: Greenbacks and gold in postbellum America. American Journal of Sociology, 101(6), 1556–1591. https://doi.org/10.1086/230867

- Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures. (2003). The role of central bank money in payment systems. Bank for International Settlements (BIS).

- Dodd, N. (2014). The social life of money. Princeton University Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt6wq0p6

- Dörry, S. (2014). Strategic nodes in investment fund global production networks: The example of the financial centre Luxembourg. Journal of Economic Geography, 15, 797–814. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbu031

- Esposito, E. (2011). The future of futures. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Evans, D. S., & Schmalensee, R. (2004). Paying with plastic, second edition: The digital revolution in buying and borrowing. (2nd ed. Auflage). The MIT Press.

- Gabor, D., & Brooks, S. (2017). The digital revolution in financial inclusion: International development in the fintech era. New Political Economy, 22(4), 423–436. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2017.1259298

- Ganßmann, H. (2013). Doing money. Routledge.

- Garbade, K. D., & Silber, W. L. (1979). The payment system and domestic exchange rates: Technological versus institutional change. Journal of Monetary Economics, 5(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3932(79)90021-7

- Genito, L. (2019). Mandatory clearing: The infrastructural authority of central counterparty clearing houses in the OTC derivatives market. Review of International Political Economy, 26(5), 938–962. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2019.1616596

- Government Office for Science (UK). (2016). Distributed ledger technology: Beyond block chain.

- Gruin, J. (2019). Financializing authoritarian capitalism: Chinese fintech and the institutional foundations of algorithmic governance. Finance and Society, 5(2), 84–104. https://doi.org/10.2218/finsoc.v5i2.4135

- Gruin, J. (2021). The epistemic evolution of market authority: Big data, blockchain and China’s neostatist challenge to neoliberalism. Competition & Change, 25(5), 580–604. https://doi.org/10.1177/1024529420965524

- Guyer, J. (2017). Cash and livelihood in soft currency economics: Challenges for research. In M. Burchardt & G. Kirn (Eds.), Beyond Neoliberalism: Social analysis after 1989 (pp. 97–116). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-45590-7

- Guyer, J. I. (2012). Soft currencies, cash economies, new monies: Past and present. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 109(7), 2214–2221. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1118397109

- Helleiner, E. (2002). The making of national money: Territorial currencies in historical perspective. Cornell University Press.

- Holmes, D. R. (2013). Economy of words: Communicative imperatives in central banks. University of Chicago Press.

- Ingham, G. (2004). The nature of money (1st ed.). Polity Press.

- Ingham, G. (2008). Capitalism: With a new postscript on the financial crisis and its aftermath. Polity Press.

- International Monetary Fund. (2009). International transactions in remittances: Guide for compilers and users.

- Katz, M. L., & Shapiro, C. (1994). Systems competition and network effects. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 8(2), 93–115. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.8.2.93

- Koddenbrock, K. (2019). Money and moneyness: Thoughts on the nature and distributional power of the ‘backbone’ of capitalist political economy. Journal of Cultural Economy, 12(2), 101–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/17530350.2018.1545684

- Kos, D., & Levich, R. M. (2016). Settlement Risk in the Global FX Market: How Much Remains? (SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 2827530). Social Science Research Network.

- Krarup, T. (2019). Between competition and centralization: The new infrastructures of European finance. Economy and Society, 48(1), 107–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147.2019.1578064

- Kress, J. C. (2011). Credit default swaps, clearinghouses, and systemic risk: Why centralized counterparties must have access to central bank liquidity. Harvard Journal on Legislation, 48, 49.

- Larkin, B. (2013). The politics and poetics of infrastructure. Annual Review of Anthropology, 42(1), 327–343. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-092412-155522

- Luzzi, M., & Wilkis, A. (2018). Soybean, bricks, dollars, and the reality of money: Multiple monies during currency exchange restrictions in Argentina (2011–15). HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory, 8(1–2), 252–264. https://doi.org/10.1086/698222

- Maurer, B. (2012). Payment: Forms and functions of value transfer in contemporary society. The Cambridge Journal of Anthropology, 30(2), 15–35. https://doi.org/10.3167/ca.2012.300202

- Maurer, B. (2016). Re-risking in realtime. On possible futures for finance after the blockchain. BEHEMOTH - A Journal on Civilisation, 9(2), 82–96. https://doi.org/10.6094/behemoth.2016.9.2.917

- Mehrling, P. (2010). New Lombard street. University Press.

- Merton, R. C. (1992). Financial innovation and economic performance. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 4(4), 12–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6622.1992.tb00214.x

- Millo, Y., Muniesa, F., Panourgias, N. S., & Scott, S. V. (2005). Organised detachment: Clearinghouse mechanisms in financial markets. Information and Organization, 15(3), 229–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infoandorg.2005.02.003

- Mirowski, P. (1991). Postmodernism and the social theory of value. Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 13(4), 565–582. https://doi.org/10.1080/01603477.1991.11489868

- Norman, B., Shaw, R., & Speight, G. (2014). The history of interbank settlement arrangements: Exploring central banks’role in the payment system. Bank of England Working Paper No. 412.

- Petry, J. (2021). From national marketplaces to global providers of financial infrastructures: Exchanges, infrastructures and structural power in global finance. New Political Economy, 26(4), 574–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2020.1782368

- Pistor, K. (2019). The code of capital: How the law creates wealth and inequality. Princeton University Press.

- Qiu, T., Zhang, R., & Gao, Y. (2019). Ripple vs. SWIFT: Transforming cross border remittance using blockchain technology. Procedia Computer Science, 147, 428–434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2019.01.260

- Rella, L. (2019). Blockchain technologies and remittances: From financial inclusion to correspondent banking. Frontiers in Blockchain, 2, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbloc.2019.00014

- Rice, T., von Peter, G., & Boar, C. (2020, March). On the global retreat of correspondent banks. BIS Quarterly Review.

- Rodima-Taylor, D., & Grimes, W. W. (2019). International remittance rails as infrastructures: Embeddedness, innovation and financial access in developing economies. Review of International Political Economy, 26(5), 839–862. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2019.1607766

- Samuelson, P. (1954). The pure theory of public expenditure. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 36(4), 387–389. https://doi.org/10.2307/1925895

- Scott, S. V., Van Reenen, J., & Zachariadis, M. (2017). The long-term effect of digital innovation on bank performance: An empirical study of SWIFT adoption in financial services. Research Policy, 46(5), 984–1004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2017.03.010

- Sillitoe, P. (2006). Why spheres of exchange? Ethnology, 45(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.2307/4617561

- Stearns, D. L. (2011). Electronic value exchange: Origins of the VISA electronic payment system (2011 ed.). Springer.

- Stiefmüller, C. (2020). Open Banking and PSD 2: The Promise of Transforming Banking by ‘Empowering Customers. In J. Spohrer & C. Leitner (Eds.), Advances in the Human Side of Service Engineering: Proceedings of the AHFE 2020 Virtual Conference on The Human Side of Service Engineering., July 16-20, 2020, USA (pp. 299–305). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-51057-2

- Tilly, R. H. (1989). Banking institutions in historical and comparative perspective: Germany, Great Britain and the United States in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics (JITE)/Zeitschrift Für Die Gesamte Staatswissenschaft, 145, 189–209.

- Voshmgir, S. (2019). Token economy: How blockchains and smart contracts revolutionize the economy. Shermin Voshmgir-BlockchainHub.

- Westermeier, C. (2020). Money is data – The platformization of financial transactions. Information, Communication & Society, 23(14), 2047–2063. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2020.1770833

- World Bank Group. (2020). Remittance prices worldwide qaterly, (No. 36, December 2020).

- Zelizer, V. A. (1997). The social meaning of money: Pin money, paychecks, poor relief, and other currencies. Princeton University Press.