Abstract

In this article, we engage with contemporary debates about South-South regionalism as spaces to advance collective development agendas. Our starting point is recent scholarship emphasizing regions as important political spaces where new development possibilities are being conceived in a changing global order. We build upon the emphasis this literature places on regions as sites of policy innovation but argue that insufficient attention has been paid to regional institutional dynamics. We explore these issues with reference to the East African Community (EAC) and its decision in March 2016 to ‘phase-out’ second-hand clothing imports, a decision which was soon abandoned by the majority of EAC states (the exception being Rwanda), following opposition from the US. While the EAC served as a crucial forum to conceive and promote this policy, we argue that its institutional foundations proved insufficient to produce the level of regional coordination necessary to ensure its implementation and to withstand external pressure. In this way, we also challenge the prevailing logic that portrays regional institutions in Africa as ‘empty spaces’ by both demonstrating the role of the EAC as a site of policy development and its institutional dynamics in shaping political outcomes.

Introduction

On 2 March 2016, the heads of state of the East African Community (EAC), then comprising Burundi, Kenya, Tanzania, Rwanda and Uganda, issued a directive for ‘member-states to procure their textiles and footwear requirements from within the region where quality and supply capacities are available competitively, with a view to phasing out the importation of used textiles and footwear within three years’ (The East African Community (EAC), Citation2016a, p. 17). The ostensible aim of the directive was to arrest the decline of the region’s indigenous textile and clothing (T&C) industry, for which second-hand clothing was held responsible. More fundamentally, the directive signified an attempt by the EAC states to exercise collective agency through the implementation of a coordinated trade and industrial strategy. Almost immediately, however, the Secondary Materials and Recycled Textiles (SMART) industry group in the United States filed a petition with the Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR), demanding the withdrawal of the region’s eligibility for the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) preference scheme. The reasoning here was that the EAC’s directive amounted to an import ban and was thus in contravention of the principle enshrined in AGOA that preference-receiving countries gradually open their markets to US trade and investment. Following the SMART petition, the USTR announced an out-of-cycle review of the EAC’s AGOA eligibility, which prompted the majority of the EAC (the exception was Rwanda) to quickly – but unilaterally – abandon the proposed policy change.

As we show in the article, the rollout and later abandonment of the second-hand clothing directive was significant for two reasons. The first is that EAC states developed this strategy collectively and, at least initially, implemented it also. This runs counter to the common tendency in the African Studies literature to portray regional institutions as ‘empty spaces’ or ‘clubs’ whose purpose is merely to boost the external sovereignty of political elites and their clientelist networks (Gibb, Citation2009; Herbst, Citation2007; Söderbaum, Citation2004). The second reason concerns the abandonment of the second-hand clothing directive by the EAC member states. Emily Wolff (Citation2021) has argued that the threat of losing AGOA eligibility placed varying degrees of external economic pressure on EAC states and that the ability of national governments to hold out against this was dependent on the specific features of each country’s domestic political settlement. This explanation is certainly not without merit, but we argue that appealing to domestic determinants alone underplays the regional institutional context in which the second-hand clothing directive was conceived. Furthermore, we show that this same regional context is key to understanding both why and how the directive was abandoned. In short, our contribution shows the importance of regional economic spaces as potential sites of policy innovation, but that the institutional norms and political practices that define these spaces can constrain as well as enable policy innovation.

Theoretically, we build from an emerging strand of International Political Economy (IPE), which takes the local institutional dynamics of South-South regionalism more seriously: that is, as institutional spaces where actors converge to contest prevailing global norms and construct new visions of development (Briceño-Ruiz & Morales, Citation2017; Riggirozzi, Citation2012; Riggirozzi & Tussie, Citation2012, Citation2015). In contrast to the ‘empty space’ caricature, this literature highlights the importance of South-South regions as distinct political spaces where actors collectively define and redefine the appropriateness of particular development agendas and practices. The main thrust of this IPE literature so far has been to emphasize the global context as the enabling environment in facilitating regional policy experimentation. We argue, however, that not enough attention has so far been paid to the internal institutional dimension of regionalism, not least the way in which pre-existing regional norms and practices define political possibilities.

To this end, we develop a theoretical framework that draws explicitly on constructivist institutionalism (Hay, 2004, Citation2016) to emphasize the complex institutional environment in which political decisions are taken and the unintended consequences which can emerge from this. In other words, the advancement of collective regional development agendas hinges not only on an appropriate global context, but also on an enabling institutional environment through which these agendas can be articulated and implemented. Institutions are understood here as encompassing formal organizations and rules as well as informal practices, norms and shared meanings. Institutional rules and norms are intersubjectively shared between actors and decision-making within these institutions exhibit a strong path-dependent logic. At the same time, institutions are characterized by ambiguity and uncertainty, to the extent that they offer the possibility of different interpretations and responses by political actors (see Heron & Murray-Evans Citation2017). In short, political institutions are ‘strategically and discursively selective’ but do not fully determine how actors will choose to behave (Hay Citation2002: 212–214).

In the specific case of the EAC, we argue that institutions served as a crucial focal point, whereby policy actors from across the region convened and conceived the second-hand clothing ban. We go on to note, however, that as the ban was rolled out in 2016, it soon came up against institutional constraints and coordination challenges that have characterized the EAC since its re-establishment in 2000. In effect, though the threat of losing AGOA eligibility placed varying degrees of pressure on each EAC state, these alone were insufficient to explain the manner and, importantly, the sequencing of the abandonment of the second-hand clothing directive. In emphasizing the importance of regional institutional contexts, we offer a corrective but also complimentary analysis to existing accounts, such as Wolff’s (Citation2021), focused on the domestic determinants of this case.

We use this case study to assess our broader theoretical argument about the role (and limitations) of South-South regionalism as sites of policy innovation. We validate our arguments by situating them in relation to existing literature and the possible alternative theoretical explanations this might offer for the political outcomes studied (Mahoney, Citation2015, p. 215-217). The empirical material for the article was gathered during a three-month period of fieldwork conducted in East Africa in 2018, alongside desk-based research and a series of follow-up (online) interviews in 2021. In total, 33 interviews were conducted with: EAC Secretariat officials (5), national government officials (1), African Development Bank officials (1), private sector representatives (3), representatives of civil society groups and NGOs (10), experts and consultants (7) and representatives of donor countries (6). Participants were chosen using a non-probability sampling method, based on their experience of working with and through the EAC. These interviews offered an insider perspective into the conception, rollout and demise of the EAC’s second-hand clothing directive. Taken together, the interviews provide crucial insights into the inner workings of the EAC and the institutional dynamics which underpin it. In corroborating the validity of our interview accounts, we are careful to triangulate this data against other interview accounts we have collected alongside other data sources (Davies, Citation2001). This includes official EAC meeting reports and documents, trade statistics, media reports and secondary academic literature.

The remainder of the article is organized as follows. First, we begin by setting out a theoretical framework that combines relevant insights from the IPE literature examining South-South regionalism with insights from constructivist institutionalism. Second, we offer contextualization to the EAC’s second-hand clothing directive, emphasizing how the strategy formed part of a broader (albeit tentative) shift in the region towards coordinated trade and industrial policies, and the institutional tensions this exposed. Third, we then turn to our case study of the EAC second-hand clothing directive itself. Here, we explore the origins and rationale of the directive. We also discuss the fate of the second-hand clothing directive and the variegated response of the EAC states to the threat of losing the benefits of AGOA. Fourth, and finally, we summarise our key arguments and theoretical contributions in the concluding section.

Beyond ‘empty spaces’: agency, ideas and institutional contexts in South-South regionalisms

Until the 1990s, the study of regionalism was synonymous with the classical theories of integration associated with the European project (Rosamond, Citation2000). Since then, various regional integration and cooperation initiatives emerged across the globe, giving rise to a wave of ‘new’ or comparative regionalism scholarship (Söderbaum, Citation2015). Unlike earlier studies of European integration, which largely saw regionalism as a process that emerged from intra-regional factors, this new comparative approach was rooted in the field of IPE and lay greater emphasis on the broader global context – specifically, processes of economic globalization – inside of which regionalism emerged (Fawcett & Hurrell, Citation1996; Gamble & Payne, Citation1996; Hettne, Inotai & Sunkel, Citation1999).

For these early accounts, the emergence of South-South regionalism was driven by and a reaction to the (assumed) imperatives of globalization (Hettne, 2005). For instance, the creation of a common investment area among the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in 1998 was said to be motivated by the prospect of attracting increasingly ‘footloose’ foreign investment while simultaneously shielding domestic firms from increasing global competitive pressures (Nesadurai, Citation2003). A more recent strand of the IPE literature considers how broader shifts in the global order – characterized by the decline of US hegemony and, with it, associated neoliberal policy norms – have opened space for new forms of ‘post-hegemonic’ regionalism to emerge. Here, particular attention has been paid to Latin America, where the ‘reimagining’ of regionalism is said to have gone furthest (Briceño-Ruiz & Morales, Citation2017; Riggirozzi, Citation2012; Riggirozzi & Tussie, Citation2012, Citation2015). In this context, it is argued that space has opened for actors in the region to construct alternate or heterodox forms of regionalism, aimed at promoting progressive welfare, social policy and human rights agendas, that contrast to the market rationalities that underpinned Latin American regionalism during the 1990s.

Two important observations can be inferred from the more recent literature. The first is that regionalism has often served as an important strategy for governments across the Global South to collectively attempt to navigate and manage the threats and opportunities that the globalized economy is perceived to present. Understood in this way, regionalism can be conceived as an exercise in agency rather than a byproduct of external economic structures.Footnote1 In other words, regions are social constructions that are imagined, instituted and legitimated by actors in relation to their external environment (see Rosamond, Citation2002). The second point is that regions are not fixed or static entities. As the example of Latin American regionalism above shows, the purpose and meaning of regionalism can be signified and re-signified across time (Riggirozzi & Tussie, Citation2015, p. 1052). Rather, the key point is that regions are social environments (Mumford, 2021, p. 9) where actors' beliefs can converge to define and redefine the appropriateness of particular policy agendas in the light of changing environments. For instance, while African regionalism was associated with self-reliance and reducing external dependencies in the 1980s (Ravenhill, Citation1986), it became synonymous with promoting global economic integration in the 1990s and 2000s (Söderbaum, Citation2004).

At the same time, regions are neither static nor entirely fluid either. In other words, South-South regional policy spaces can serve as important sites where novel development agendas can be conceived and articulated. Attempts to implement such agendas, however, occur within specific institutional settings that favour certain strategies over others (Hay, Citation2006, p. 63), something which is overlooked within the comparative global regionalism literature reviewed previously. This is a point acknowledged by key scholars working within this field, as Pia Riggirozzi (Citation2012, p. 437) notes in reference to Latin America: ‘the extent to which new regional initiatives can consolidate coherent and resilient projects is still to be seen’. This is a crucial point, since the viability of regional institutions to promote particular policy strategies lies not only in their capacity to articulate but to also institutionalize and successfully implement them. In other words, the political feasibility of collective development strategies rests as much on the internal character of regional institutions as it does on the wider global environment.

To address this, we draw upon theoretical insights from constructivist institutionalism (Hay, Citation2006, Citation2016; see also, Heron & Murray-Evans, Citation2017). The distinctiveness of a constructivist institutionalist approach is its understanding of agency as context bound. Actors are assumed to operate within complex institutional contexts defined by formal rules and informal norms and practices, which channel agents (often unintentionally) towards certain courses of action over others. Crucially, however, it also emphasizes that actors' understanding of their immediate institutional context is often uncertain, incomplete and proves ‘to have been inaccurate after the event’ (Hay, Citation2006, p. 63). The result is that actors will often pursue strategies without full knowledge of their institutional context which can result in unintended consequences and outcomes. The significant point here is that while the literature discussed above points to the role of regions as sites for deliberation and the transmission of new policy agendas, less emphasis has been placed on how these interact with existing regional institutions. In this article, we conceive of regions as institutional environments which have embedded within them rules, norms and practices (the significance of which is not always evident to actors in question) that can unintentionally shape and constrain policy outcomes.

In conceiving of regional institutions in this way, our account pushes against the prevailing logic that characterizes African regional organizations as ‘empty spaces’ (see, inter alia, Gibb, Citation2009; Herbst, Citation2007; Söderbaum, 2010). This logic holds that regional institutions principally serve as spaces where African leaders can performatively and symbolically engage in processes of regionalism to boost their sovereignty and political status. The underlying premise is that the internal political authority of African leaders and their governments is much weaker than in other parts of the world. They will, therefore, participate in regionalism as a way to boost their external image and sovereignty, but will stop short of implementing the substance of regional agreements (e.g. trade liberalization, delegating competences to supranational institutions), which may weaken their domestic authority. In short, regional institutions in Africa are understood as empty spaces whose formal rules can be cast aside when national elites no longer perceive them to serve their interests.

We depart from this logic in two important ways. First, we view regional institutions in Africa as dense policy spaces where actors (not just political leaders) from across national boundaries can converge to define and redefine collective challenges they face to establish strategies to respond to them. For instance, the EAC consists of various forums where actors converge for these very purposes. This includes an annual Heads of State summit and the biannual Council of Ministers meetings, alongside sectoral committees which bring together lower-level bureaucrats and policy experts from across the region to deliberate on issues such as trade, health and infrastructure. Regional institutions in Africa, then, constitute distinctive arenas – that sit in tandem with but separate from national political spheres – where specific policy agendas can be conceived, developed and legitimized. As we demonstrate in this article, the EAC served as a forum where the regional second-hand clothing ban was proposed, agreed to and developed into a formal strategy (EAC, 2017). We also emphasize that this strategy formed part of a broader normative shift across the region towards state-oriented trade and industrial policies: a shift we argue was partly facilitated and consolidated within EAC policy spaces.

Second, we emphasize the significance of regional institutional dynamics and political practices in shaping outcomes and behaviour. This point has already been acknowledged to some degree in other regions of Africa. For instance, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) has been said to have played a crucial role in consolidating norms of democratization, constitutionalism and supranationalism in West Africa (Ateku, Citation2020; Hartmann, Citation2017; Júnior & Luciano, Citation2020; Mumford, 2021). Our account is more cautious about the emancipatory potential of regional institutions in this regard by laying greater emphasis on the unintended consequences of institutional norms and practices. Regions can serve as forums where collective development strategies can be conceived, but the implementation of these occurs in complex institutional environments which shape political possibilities. In this way, we view regional institutions as constitutive norms and practices which shape the context in which actors interact, as opposed to formal rules that can be simply ignored. As we outline in this article, while the EAC served as a forum in which the second-hand clothing directive was conceived, its institutional foundations were unable to provide the level of regional coordination necessary for both its implementation and resistance to US pressure. Specifically, we outline how the second-hand clothing directive formed part of a normative shift within the EAC towards more coordinated trade and industrial strategies. We note, however, that realization of this agenda – and the second-hand clothing directive specifically – was soon impeded by the specific institutional features of the EAC and its close affinity with market-based integration and zero-sum conceptions of economic sovereignty.

The EAC and the reshaping of regional governance: from enabling markets to trade and industrial policy coordination

Before exploring the emergence and rollout of the second-hand clothing ban, we first offer some background regarding the evolution of the EAC since 2000. Formal regionalism in East Africa dates to the early twentieth century (Ingham, Citation1963; Nye, Citation1966) and the EAC was first established in 1967 (Hazlewood, Citation1979). The first iteration of the EAC, however, collapsed in acrimony in 1977 as its members fought over claims of unfairness concerning how the benefits of integration were distributed. The current EAC was established in 2000 between Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda (Burundi and Rwanda became members in 2007).Footnote2 The revived EAC set out an ambitious agenda that envisaged a step-by-step integration process, from the establishment of a customs union to a common market and monetary union, and ultimately the creation of a political federation.

The EAC’s revival was accompanied by political rhetoric, which appealed to ideas of common political community and East African exceptionalism. This exceptionalism rested on an understanding of the region as a unique and exclusive space, defined by its long history of integration and cooperation (O’Reilly, Citation2019, Ch. 6). Although political narratives converged on ideas of East African exceptionalism, these were overlaid by neoliberal conceptions of development, which stressed not only the desirability but also the necessity of market-conforming policies in meeting the challenges of globalization (ibid., Ch. 4; see also: Hay & Rosamond, Citation2002; Rosamond, Citation2002). As this extract from the EAC’s second regional development strategy notes:

The strategy has considered developments in globalization and implications on the intensification of competition, influence on the position of EAC in the world market and the imperatives of implementing regional cooperation programmes (The East African Community (EAC), Citation2001, p. viii)

Following its revival in 2000, the EAC gained a reputation as one of the more successful examples of regional integration and cooperation in Africa. A customs union and common trade regime, for example, were quickly agreed to by 2004 (The East African Community (EAC), Citation2004). Despite this, tensions were evident within the EAC’s regional project almost from the outset. Although ideas of common political community were commonly invoked to garner support for the EAC’s revival, residual suspicions and national rivalries continued to simmer under the surface. This drew from memories of the EAC during the 1960s and 1970s and, in particular, the perception that the benefits of integration had been skewed towards Kenya (Mold, Citation2015, p. 582).Footnote3 The EAC’s treaty of establishment explicitly sought to placate these concerns by emphasizing that regional integration and cooperation would be underpinned by the principles of ‘equitable sharing of benefits’ and ‘variable geometry’ (The East African Community (EAC), Citation1999; see also Binda, Citation2017). Although setting an institutional precedent for variable geometry and differential treatment, the EAC’s treaty was ambiguous on how and in what circumstances these principles were to be operationalized in practice. The result was that trade practices emerged in an ad-hoc fashion, giving EAC member states considerable flexibility in interpreting the rules. This is evident, for example, in the practice of ‘stays of application’, where national governments in the EAC can derogate from specific tariff lines in the regional CET for a year at a time to protect certain domestic industries or address product shortages (Bünder, Citation2018, p. 4). Stays of application were initially permitted as a short-term measure to smooth over the implementation of the CET, but their use has continued ever since (ibid.).

These tensions between the formal rules and informal practices were broadly kept in check during the 2000s, as the member states' private sector and market-driven development agendas largely aligned with the EAC’s ambitions for the creation of a single regional market. By the latter part of the 2000s, however, governments in the EAC began, albeit tentatively, to articulate national development visions that moved beyond the parameters of market-led development to embrace previously circumscribed ideas of industrial strategy and even import-substitution (Behuria, Citation2019; Fourie, Citation2014; Hickey, Citation2012, Citation2013; Jacob & Pedersen, Citation2018; Paget, Citation2020). Such discursive shifts did not occur in isolation but formed part of an emerging trend across Africa (Harrison, Citation2019) and the global economy (Alami et al., 2021) that saw a tentative re-legitimation of state-led development. In the specific case of the EAC, this shift entailed a changed emphasis away from good governance and macroeconomic stability and towards new agendas centred on industrialization and structural transformation.

The EAC served as a crucial focal point in shifting the policy focus in this direction. In 2006, the EAC Heads of State directed the EAC Secretariat to begin consultations on developing a regional industrialization strategy (The East African Community (EAC), Citation2007, p. 143). This culminated in 2012, when the EAC’s regional industrial strategy (2012a) and industrial policy (2012b) were released. In contrast to the market-conforming logic that had underpinned the revival of the EAC, these policy pronouncements called for ‘a larger governmental role in the promotion of productive restructuring’ (The East African Community (EAC), Citation2012b, p. 4). Taken together, however, this emergent policy prospectus represented an incremental rather than a radical shift in development thinking in the region. Notably, the EAC’s industrial strategy (2012a, p. 5) explicitly ruled out a return to East Africa’s more heavy-handed approach to state development planning, typical during the 1960s and 1970s, and continued to place emphasis on the private sector as the engine of industrialization and development. But the strategy also lamented the wholesale removal of industrial support policies that had gone alongside economic liberalization in the region during the 1990s (ibid, p. 6). It argued that the withdrawal of these policies by East African governments had exposed the region’s industrial sector to external competitive pressures, resulting in its subsequent decline. The significance of the EAC’s 2012 industrialization agenda, therefore, was that it openly articulated a revived (though tentative) role for state and regional institutions in the promotion of specific industrial sectors.

These two documents also emphasized an important role for regional integration as part of this, particularly in terms of providing expanded markets for nascent regional industries (The East African Community (EAC), Citation2012b, p. 5). Significantly, however, the EAC itself was not identified as an agent in these state-directed activities, but more as providing a coordinating environment for its members to pursue their own national strategies (The East African Community (EAC), Citation2012a, p. i). In other words, although the EAC was placed front and centre of this emergent development agenda, tacitly this agenda reaffirmed the primacy of the member states in economic policy making. But in contrast to the market-conforming policy agenda that characterized the EAC’s relaunch, the shifting emphasis on national development planning and coordinated trade and industrial strategies would require a greater rather than a lesser degree of regional policy coordination. Earlier EAC development agendas, particularly those focused on the creation of the regional customs union, had rested on the presumption that by simply removing intra-regional trade barriers, market competition and economies of scale alone would spur economic development in the region (see The East African Community (EAC), Citation2002). In contrast, the tilt towards state-directed development would require national governments to coordinate their industrial and public procurement policies more closely. This requirement, however, jarred with the national rivalries and economic nationalism which had defined the informal practices of the EAC’s regional project from its outset.Footnote4

The ‘new developmentalism’ in East Africa, thus, quickly became associated with campaigns such as ‘Buy Kenya, Build Kenya’, ‘Buy Uganda, Build Uganda’ and ‘Made in Rwanda’, all of which aimed to leverage domestic demand and public procurement towards goods and services produced nationally (CUTS International, Citation2017). These campaigns not only went against the spirit of regional cooperation, but they also appeared to potentially go against the non-discrimination principles outlined in various EAC treaties. For instance, in 2017 Uganda introduced a 12 per cent verification fee on certain imported medicines, even those originating from EAC markets, to encourage their local production (Uganda National Drug Authority, Citation2017). This led other EAC states to accuse Uganda of contravening the non-discrimination principles of the regional common market protocol (The East African Community (EAC), Citation2018a, p. 49). Although some in the region called for these strategies to be harmonized under a ‘Buy East Africa, Build East Africa’ banner, these calls largely fell on deaf ears.Footnote5 Indeed, one interviewee from the Kenya Association of Manufacturers (KAM) explicitly noted that while they maintained links with other business organizations in the region, the sole mandate of KAM was to champion national producers.Footnote6 Alongside this, national deviations from the regional CET in recent years via stays of application have become more commonplace. While such deviations have existed since the implementation of the customs union in 2005, these have increased in volume over the last decade and have been used more and more by the EAC states to unilaterally increase domestic import restrictions to champion national industries (Bünder, Citation2018; Rauschendorfer & Twum, Citation2020).

These trends reflect certain institutional limitations of the EAC. To recall, when established in 2000, the EAC was conceived to support a program of market-led development in the region. Regionalism in East Africa, as such, unfolded as a process geared towards the removal of intraregional barriers to trade and investment. The EAC maintains a regional secretariat that, although small, plays a key role as a promoter and contributor to regional policy innovation. Yet, the actual implementation of the EAC’s integration and cooperation agenda primarily occurs through and is reliant upon national ministries. Moreover, beyond the CET, there are very few institutional mechanisms at the regional level to shape patterns of accumulation. Institutional ambiguities around the operationalization of variable geometry have also provided space for national deviations and unilateral action. Indeed, the increasing utilization of stays of application is precisely because the criteria for their use are vague (Bünder, Citation2018, p. 4). According to insider accounts, the EAC’s Council of Ministers rarely deny member state requests for them.Footnote7

These trends also speak to a much deeper disconnect between the EAC’s regional integration process and ideas of political community in the region. As Andrew Mold (Citation2015, p. 582) has noted, there have been very few signs that the member states have sought to meaningfully align their industrial development visions to the EAC’s regional strategy. Part of the reason for this, he argues, rests with the mutual suspicion and economic rivalries that still define the EAC. The key point here is that, although the EAC’s revival in the 1990s was premised on ideas of East African exceptionalism and common political community, the move towards a more activist development agenda exposed the continued appeal of zero-sum conceptions of national economic sovereignty.

The EAC and the regional politics of the second-hand clothing directive

It was within this emergent, but contradictory, policy setting that the EAC’s directive to phase-out second-hand clothing was issued. On 26 February 2016, the EAC’s Sectoral Council of Trade, Industry, Finance and Investment (SCTIFI) met to discuss the findings of a report conducted to examine the modalities for promoting the region’s textile and leather sector. During the meeting, the committee noted that second-hand clothing imports were having a detrimental impact on the development of local industry.Footnote8 Since the early 1990s, imports of used or second-hand clothing from western countries have flooded African consumer markets, but the impact of this trade is still openly debated. For some, the influx of used clothing is said to have undercut domestic African T&C producers, resulting in their decline during this period (Frazer, Citation2008), while for others the link between imported used clothing and the decline of African industry is less clear cut (Brooks & Simon, Citation2012).

In this instance, members of SCTIFI appeared to align with the former, with recommendations being made that a phased approach be taken to reducing – and eventually eliminating – the importation of used clothing into the region to encourage local T&C production. This recommendation was presented to the EAC at a Heads of State Summit in March 2016, which issued a directive for the importation of used clothing to be phased-out within three years (The East African Community (EAC), Citation2016a, p. 17). At this early stage, there appeared to be a consensus among the EAC governments in support of the regional used clothing ban, which broadly aligned with their own national ambitions for reviving their domestic T&C sectors (Wolff, Citation2021). As we detail below, however, this initial consensus soon came up against the coordination challenges and institutional pathologies (detailed previously) which have defined the EAC since its revival.

The directive was operationalized in the months that followed, with a regional gazette issued in June 2016 that doubled import duties on used and worn clothing from 35% or $200/ton to 35% or $400/ton (whichever is higher) (The East African Community (EAC), Citation2016c). In the same gazette, Rwanda applied a one-year stay of application, rolled over in the years since, unilaterally increasing its import duties to $2,500/ton, significantly above what had been agreed by the EAC (ibid.). In April 2017, the EAC secretariat also released an internal draft strategy for the phase-out that indicated that these measures were to be the first in a series of duty increases that would gradually bring regional tariffs on used and worn clothing to $5,000/ton by 2018 (The East African Community (EAC), Citation2017a, p. 7). In effect, the EAC member states were seeking to pursue a program of import-substitution to replace the market for second-hand clothing with locally produced goods.

In part, the EAC’s second-hand clothing directive was a product of a broader shift in terms of what was deemed legitimate in development practice across Africa. Although East Africa’s trade regime had never been wholly open and liberal (Mold, Citation2015), up until this point regional policy discourses had presented the EAC as supporting a market-conforming policy agenda, designed to promote both regional and global integration. The issuing of the second-hand clothing directive, however, symbolized a shift towards a more state-directed and inward-oriented development agenda, particularly in relation to the region’s T&C sector. For instance, the Tanzanian government’s 2016 ‘Cotton to Clothing Strategy’ spoke openly and explicitly about utilizing import-substitution (The Government of Tanzania, Citation2016, p. 31). Similarly, import-substitution – or ‘domestic market recapturing’ – was also integrated into Rwanda’s national development strategy in 2015 (The Government of Rwanda, Citation2015; see also Behuria, Citation2019).Footnote9

The second-hand clothing ban also spoke to the challenges that the EAC economies had faced integrating into global T&C production networks. Following independence in the 1960s, East Africa’s economies had managed to develop a sizable T&C industry (Chemengich, Citation2013; Kabelwa & Kweka, Citation2006; Langdon, Citation1986). The sector, however, fell into sharp decline during the 1990s, as the region’s economies were liberalized under tutelage from the International Monetary Fund and World Bank. This process placed the region’s T&C import-competing sector under increasing competitive pressures, driven by falling domestic demand and an influx of imported new and second-hand clothing available at a significantly lower cost (Brooks & Simon, Citation2012). The introduction of AGOA by the US in 2000 did reverse some of these trends. This preference scheme offered eligible countries across Africa duty- and quota-free access to US markets on certain tariff lines.Footnote10 It also included a so-called ‘third fabric’ provision that allowed ‘lesser developed’ countries to export garments duty-free using fabrics and yarns (intermediary inputs) sourced from third countries. (Heron, Citation2012, p. 137). In East Africa (alongside other African regions), this had a significant impact in spurring garment assembly in the region as foreign - predominantly Chinese - firms set up production in the region to export to the US.

The economic boom fuelled by AGOA, however, was not an unqualified success and the revival of East Africa’s T&C sector was more distorted than revealed by aggregate figures. On the one hand, the growth of apparel and clothing assembly in East Africa was (and still is) entirely dependent upon the AGOA preference scheme. In 2017, for instance, around 96 per cent of Kenya’s apparel exports were destined for US markets.Footnote11 On the other hand, nearly all of East Africa’s garment exports utilize AGOA’s third fabric provision. In other words, garment exports destined for the US market are, almost exclusively, produced using intermediary textiles and fabrics from third-country sources. The growth of garment assembly has therefore brought limited benefits to downstream cotton growers and textile producers in East Africa (Arnell, Citation2016; Chemengich, Citation2013). Kenya’s 2012 national AGOA strategy even goes so far as to suggest that foreign firms have merely used Africa ‘as a staging post’ to take advantage of AGOA preferences rather than investing in an integrated local textile and apparel sector (The Government of Kenya, Citation2012, p. 5). In short, although AGOA enabled the growth of an export-oriented apparel sector in East Africa, it did little to aid import-competing and domestically oriented T&C firms in the region, which had borne the brunt of the externally sponsored liberalization measures of the 1980s and 1990s.

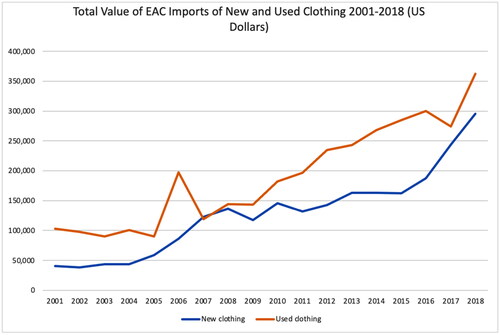

These trends help us to understand the growing attractiveness of import-substitution and the specific targeting of the T&C sector. But what led the EAC’s policy community to converge around a policy of restricting used clothing imports to meet these objectives? As critics of the directive have noted, the EAC states could have pursued other policies to support the development of a more domestically integrated T&C sector (USAID, Citation2017), such as encouraging sourcing from local cotton and textile producers. There is also the question of why used clothing imports were singled out. As indicates, while used clothing imports had increased substantially since 2001, this import growth was not dramatically different than that for unused clothing. Indeed, as one interviewee predicted in 2017, the most likely effect of the used clothing ban would be to flood regional markets with cheap imports of new clothing from low-cost producers in China and elsewhere.Footnote12 This prediction appears to have been borne out in Rwanda (Essa, Citation2018), the only EAC state that remains committed to the spirit and letter of the second-hand clothing directive.

Figure 1. Total value of EAC imports of new and used clothing, 2001-2018 (US Dollar thousand). Source: International Trade Centre’s Trade Map (https://www.trademap.org/Index.aspx). Notes: New clothing imports calculated using an aggregate of imports of HS product codes 61 and 62 by EAC members. Used clothing imports calculated using an aggregate of imports of HS product code 6309 by EAC members. Data does not include South Sudan.

Why then did the EAC states come to single out second-hand clothing imports in their efforts to revive the T&C sector? As previously noted in this article, there has been a tendency within the literature to view regional institutions in Africa in very narrow terms – spaces that function merely to boost the sovereignty of national political leaders and their followers (Gibb, Citation2009; Herbst, Citation2007; Söderbaum, Citation2004). We argue, however, that the case of the EAC’s second-hand clothing ban illustrates that the role of African regional institutions is more significant than this, particularly as spaces where actors can convene to identify specific issues and narrate collective solutions to them. In other words, regions are social environments where particular interpretations and ways of thinking about events and issues can be consolidated among policy actors. Such a consolidation of thinking was evident in the conception of the EAC’s second-hand clothing directive. Despite the various and complex constraints facing the region’s T&C sector, officials participating within regional forums quickly came to identify and single out second-hand clothing imports as the key contributing factor. For instance, an initial survey of East Africa’s T&C sector, conducted by the EAC Secretariat in 2015, found that second-hand clothing imports were one constraint among many facing the sector.Footnote13 Yet, in their review of this study, the SCTIFI largely made recommendations centred on restricting the importation of used clothing, rather than addressing supply constraints that the Secretariat also identified (The East African Community (EAC), Citation2016b, pp. 32-33). These recommendations were then taken up by the EAC Council of Ministers (ibid, p. 33) and then later by the EAC Heads of State, which came to issue the directive for the phasing-out of used clothing imports (The East African Community (EAC), Citation2016a, p. 17).

The singling out and targeting of second-hand clothing imports was prominent within EAC policy discourses. For instance, the EAC’s draft strategy for the phase-out identified used clothing imports as a driving factor behind the historical decline of the region’s T&C sector. As the strategy notes:

In the 1960’s to the early 1980’s, the clothing and shoes industrial sector in East Africa was thriving and producing for both the local markets as well as the export markets, and employing thousands of people. Value chains in the sector were well established right from the production of raw materials to the finished products. However, over the years, the clothing and shoes manufacturing industries have collapsed with the emergence of an informal sector dealing in used clothes and shoes (The East African Community (EAC), Citation2017a, p. 2).

The key point here is that the EAC served as a key site of interaction where policy officials from across the region convened and where particular subjectivities and narratives about second-hand clothing imports were consolidated among governments across the region. Although used clothing imports have long attracted the ire of African governments (Brooks & Simon, Citation2012), we argue that the EAC served as an important site of policy deliberation where the phasing-out of used clothing came to be seen as a viable solution to promoting the region's T&C sector. Indeed, as we point out below, while this collective strategy would soon be unilaterally abandoned in the face of US economic pressure and regional policy incoordination, each of the EAC states did initially converge around its aims. Each government, for instance, committed to an initial doubling of import duties on used clothing in June 2016. This included the Kenyan government, the first to abandon the directive in 2017, which even sought to get second-hand clothing traders in the country to support the policy in 2016 (Wolff, Citation2021, p. 1316).

One alternative explanation might be that the second-hand clothing directive emerged from lobbying from specific elements of the T&C sector in the region. While T&C firms were initially consulted during the EAC Secretariat’s 2015 survey of the sector, there is little evidence to suggest that they actively agitated for second-hand clothing imports to be phased-out or restricted. Indeed, Wolff (Citation2021) suggests that industry representatives in the region were relatively indifferent to the policy. Our briefings with stakeholders also suggest that the EAC has its own institutional dynamic that exists in relation to (but separate from) national politics and policy making. Stakeholders in the region, both from the private sector and civil society, described the policy process at the EAC as quite bureaucratic, insulated from outside interference and even somewhat detached from national politics.Footnote16 A representative from KAM even noted in an interview in 2017 that regional officials behind the strategy were slightly detached from the practical implications that the policy would have on T&C exporters and second-hand clothing traders on the ground.Footnote17

This further confirms our argument about the significance of the EAC as a site of policy deliberation and development. As we mentioned previously, the used clothing phase-out itself was initially proposed and agreed to within various regional meetings and it was the EAC Secretariat that developed a draft strategy for its rollout (The East African Community (EAC), 2017). The point to highlight here is that the EAC was the key focal point and setting in which this ambitious policy agenda emerged. It could even be surmised that the used clothing phase-out served as an important interlocutor through which the continued relevance of the EAC could be demonstrated in a broader policy context that had seen a shift towards state-coordinated trade and industrial strategies. What we reveal in the remainder of this section is the degree to which this shifting policy consensus conflicted with the institutional setting in which it was implemented.

Developmentalism versus US market power – the fate of the EAC second-hand clothing ban

Not long after the EAC second-hand clothing directive was issued in March 2016, it soon attracted the attention of US trade officials and industry groups. In March 2017, the Secondary Materials and Recycled Textiles Association filed a petition with the USTR, calling for a review of the EAC member states AGOA eligibility. The petition argued that the EAC’s second-hand clothing phase-out violated AGOA’s eligibility criteria that beneficiaries make progress towards establishing market-based economies and move towards eliminating barriers to US trade (Secondary Materials and Recycled Textiles Association (SMART), Citation2017b). Following SMART’s petition, the USTR announced that it would hold an out-of-cycle review of Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda’s AGOA eligibility (US Trade Representative (USTR), Citation2017).Footnote18 The Kenyan government had already indicated in May 2017 that it would withdraw from the planned phase-out to preserve its AGOA eligibility, thus exempting it from the out-of-cycle review (Mutambo, Citation2017). In June 2017, the Kenyan government applied a stay-of-application, unilaterally reducing duties on worn clothing to pre-2016 levels (The East African Community (EAC), Citation2017b). In contrast, Rwanda rolled over its stay of application from 2016, maintaining duties of $2500/ton on used clothing (ibid.), indicating its commitment to maintaining the directive in the face of US pressure.

The USTR held the EAC’s out-of-cycle review hearing in July 2017. In this hearing, the USTR heard evidence from the EAC Secretariat, the member states and industry groups such as the African Cotton & Textile Federation (ACTIF).Footnote19 One consistent theme that emerged across the submissions supporting the EAC states was the compatibility of the used clothing ban with World Trade Organisation (WTO) rules. The EAC Secretariat, for instance, argued that increased duties on used clothing were non-discriminatory and applied to all second-hand clothing imports, not just those from the US. Similarly, ACTIF argued that because used clothing was not actually manufactured in the US, it could not be considered as originating goods. In short, the US itself could not claim harm from the used clothing phase-out. Yet, there were also inconsistencies in the evidence defending the EAC. For instance, in their evidence both the EAC Secretariat and Uganda sought to backtrack on previous pronouncements, suggesting that the 2016 tariff increases on used clothing were merely a minor adjustment of duty rates, rather than encompassing a broader attempt to phase-out second-hand clothing. By contrast, both Tanzania and Rwanda offered a more robust defence of their sovereign right to impose import restrictions or to phase-out or ban second-hand clothing. These inconsistencies were later picked up on by opponents of the EAC’s second-hand clothing directive and used to discredit the evidence supporting it.Footnote20

At the time, insider lobbyists in Washington suggested that while the legal argument favoured the EAC, the expectation was that the EAC would have their AGOA eligibility revoked (Kelley, Citation2017a). In anticipation of this, Burundi, Tanzania and Uganda diverged from the official CET tariff on used clothing in February 2018, applying a stay-of-application that reduced duties on second-hand clothing to pre-2016 levels (The East African Community (EAC), Citation2018b). Meanwhile, at an EAC Heads of State summit that same month, a directive was issued that effectively indicated a retreat from the second-hand clothing directive. This followed a suggestion by Harry Sullivan, USTR’s Director for Africa, that the EAC states would maintain their AGOA eligibility if they reduced their tariffs on used clothing to pre-2016 levels (Ligami, Citation2018). Rwanda, however, maintained its duty rate on worn clothing at $2500, prompting the US to suspend its AGOA preferences in March 2018.

How, then, do we account for the manner in which the EAC states abandoned the second-hand clothing phase-out? The obvious explanation is to appeal to structural asymmetries and the degree of trade dependency of the EAC states on AGOA preferences. This explanation is not without merit. As indicates, the US represents a significant export market for regional apparel products, in particular for Kenya and Tanzania. Yet, the trade dependency explanation only takes us so far. For instance, Uganda was much less reliant on AGOA preferences and Burundi had been (and still is) suspended from the preference scheme since 2015. Yet, both countries still succumbed to US pressure and withdrew from the planned phase-out. Moreover, while on aggregate Rwanda’s apparel exports to the US were relatively low, it had lately made significant investments in the local T&C sector (Behuria, Citation2019) and apparel exports under AGOA had also begun to increase (see: ).

Table 1. US Apparel Imports from EAC states, 2011-2018 (US Dollar thousand).

Emily Wolff (Citation2021) has supplemented this trade dependency explanation by developing an account that incorporates the domestic political dimension of the EAC states. Drawing upon a political settlements framework (cf. Khan, Citation2018), Wolff argues that domestic distributions of power are key to understanding why the EAC member states did or did not succumb to US pressure. For instance, despite being a relatively small economy, Wolff argues that Rwanda was able to maintain the used clothing phase-out because there is a strong concentration of power in and around the ruling coalition of President Paul Kagame and the Revolutionary Patriotic Front. Wolff argues that this contrasts to the other EAC states, where the holding power of ruling coalitions is weaker, meaning that they were less capable of absorbing the economic costs of losing AGOA eligibility.

Wolff’s analysis certainly offers important insight into the domestic political dynamics of this case. By focussing solely on the national level, however, Wolff overlooks the intermediary regional dynamics of the second-hand clothing directive, which were crucial not just to its original conception but also the sequencing of its abandonment. The key point is that even though US intervention in 2017 certainly posed a looming threat to the region’s AGOA eligibility, it was not an immediate one. Rwanda, for instance, only lost its AGOA apparel preferences in March 2018, almost a year after SMART’s initial petition to the USTR. Considering this, and the fact that the second-hand clothing directive was conceived as part of a regional strategy, the question that remains is why was there not more of a concerted effort on the part of the EAC states to coordinate a collective response to US pressure?

To understand this, we need to return to the previously discussed coordination challenges and institutional ambiguities that characterize the EAC’s regional project. At the time of writing, although the official EAC CET rate for used and worn clothing still stood at the increased 2016 rate of 35% or $400/ton, none of the member states were currently applying this rate (The East African Community (EAC), Citation2019, Citation2020). Put another way, what this demonstrates is the limited capacity of regional institutions, or more precisely the EAC Secretariat, to prevent member states from reneging on policy commitments previously agreed at the regional level. As we have seen, the EAC was initially conceived as a space to support market-led integration - a policy agenda that, paradoxically, depended on considerably less policy coordination. It is not the case that market-led integration weakened the EAC’s regional institutions, but nor did it strengthen them either. The point is that market-led integration - at least the version of this introduced in East Africa - did not require the depth of policy coordination that would be required of the more state-directed policy innovations that emerged in the 2010s. The second-hand clothing directive and its challenge by the USTR required a degree of regional policy coordination that the EAC was ill-equipped to provide. East Africa’s national governments were further able to capitalize on institutional ambiguities within the EAC, particularly around variable geometry and differential treatment, to utilize the practice of stays-of-application to derogate from the second-hand clothing directive in the face of US pressure.

The fate of the EAC’s second-hand clothing directive was also telling of the disconnect between the EAC’s regionalist project and ideas of political community within the region. Crucially, while these institutional ambiguities offered the space for the member states to abandon the directive, their rationale for doing so stemmed more from the persistence of zero-sum conceptions of national sovereignty and development in the region. Put another way, even though the second-hand clothing phase-out was pursued on a regional scale, it was a policy whose perceived benefits were understood largely (if not exclusively) in terms of national development. In fact, economic nationalism was evident from the initial conception of the second-hand clothing directive in March 2016, not just at the point at which it was abandoned. To recall, when the directive was first implemented in June 2016, the Rwandan government immediately issued a stay of application increasing its own import duties above those of its regional partners. More tellingly, Rwanda’s continued pursuit of a second-hand clothing ban is technically now in contravention of the current EAC position, which endeavours to promote the region’s T&C sector through other measures.

The significance of the EAC’s 2017 AGOA review was that it further brought this disconnect to the fore and exposed the shallowness of the member states' commitment to regional solidarity and collective action. When SMART petitioned the USTR to review the EAC’s AGOA eligibility, Kenya immediately sought to distance itself from the second-hand clothing directive to protect its preferential access to the US market.Footnote21 The decision to immediately and unilaterally withdraw from the used clothing phase-out was not, however, the only option open to the Kenyan government. For instance, Kenya could have deliberated with its regional partners and attempted to try and alter the policy to make it consistent with AGOA. Further, the Kenyan government could have collaborated with other EAC states in defending the proposed used clothing phase-out at the USTR review hearing in July 2017.

Instead, the Kenyan government abandoned any pretence of regional solidarity or collective action and hired a US-based lobbying firm to assist in their efforts to retain their national AGOA preferences (Kelley, Citation2017b). Even for those EAC states that persisted in their defence of the used clothing ban at the USTR hearing, collective action was lacking. As pointed out earlier in this section, there were inconsistencies in the evidence presented by the different delegations supporting the EAC at this hearing. What all this reveals is that the abandonment of EAC’s second-hand clothing directive is not entirely reducible to factors relating to external trade dependency or domestic distributions of power. In short, the intervention of the US in this case further exacerbated and exposed pre-existing institutional tensions long embedded within the EAC. As we have shown, these tensions are critical for understanding how and why the directive was abandoned.

Conclusion

In this article, we have offered a theoretical and substantive contribution to ongoing debates around South-South regionalism. We have built on an emergent strand of IPE literature, which highlights the growing importance of regions as political spaces where new development possibilities are being conceived in the context of a changing global order. In common with this literature, we have emphasized the notion of regions as social environments, that is: transnational spaces where actors can convene and reconvene across time to define and redefine the appropriateness of particular policy agendas in the light of changing global circumstances. Whereas the existing literature has, in the main, stressed the importance of the external context as an enabling environment, our focus has been on the internal institutional dynamics of regionalism, not least the way in which regional institutions define political possibilities. As such, we developed a theoretical argument that drew explicitly on constructivist institutionalism, to emphasize the complex institutional environment in which political decisions are taken and the unintended consequences which emerge from these. In short, we argued that the feasibility of collective development strategies depends not only on an accommodating global environment, but also the internal institutional context of regionalism in providing the level of policy coordination necessary for their implementation.

We extended these theoretical insights to explore how the EAC’s second-hand clothing ban was conceived, implemented and subsequently abandoned. While existing accounts have explored the individual national responses of the EAC states to US pressure, we focused instead on the regional origins and dynamics of this case. We argued that the EAC and its regional institution served as a crucial focal point in which political actors and officials from across the region convened and conceived of the used clothing ban. We went on to show that, although external economic pressure from the US and domestic political determinants were decisive factors in determining the fate of the second-hand clothing directive, the unilateral manner in which it was abandoned was, in no small part, due to the specific institutional character of the EAC. In sum, although the EAC’s institutional foundations were sufficient to provide space for the policy deliberation that gave rise to the second-hand clothing directive, they were insufficient to provide the levels of regional coordination for its implementation and to collectively withstand US pressure.

The broader contribution of this article, then, is a theorization of South-South regionalism as sites of collective agency and policy innovation, which are bound not just by external structures - as others have emphasized - but also by internal institutions that defined them. As such, our theorization offers a necessary corrective to the prevailing caricature of South-South - and African more specifically - regional institutions as ‘empty spaces’, in which political elites performatively and symbolically engage in processes of regionalism to boost their sovereignty and political status, only to cast them aside when they no longer serve their interests. The case of the EAC’s second-hand clothing directive illustrates that regional institutions in Africa are more significant than this. As this article has shown, regional institutions in Africa can serve as forums where new development possibilities can be conceived and the norms and political practices embedded within them can shape political outcomes. The findings of this article also point to tensions within development discourses emerging across Africa. Since the launch of negotiations for the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA) in 2012, regionalism in Africa has been framed in terms of its potential to promote industrialization and structural transformation across the continent (Odijie, Citation2019; O’Reilly, Citation2020). The case of the EAC’s second-hand clothing ban, however, illustrates the challenges of attempting to coordinate a region-wide industrial strategy in a context where strong attachments to national economic sovereignty still endure. We invite future work to explore how these complex institutional dynamics have played out in other regions and contexts.

Acknowledgements

Previous versions of this article were presented at the Development Studies Association Conference, University of Manchester (June 2018), the International Politics Research Seminar, Department of Politics – University of York (December 2018) and the European International Studies Association Annual Conference, Sofia University (September 2019). We would like to thank the panel and audience at these events, alongside the anonymous reviews, for their insightful comments and feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential competing interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Peter O’Reilly

Peter O'Reilly is Lecturer in International Relations and Politics at Liverpool John Moores University. His research broadly focuses on the politics of regionalism and trade governance in Africa. In 2019, he completed his PhD at the University of York, where he examined how changing conceptions of development have been both articulated through and constrained by the institutional and discursive landscape of the East African Community.

Tony Heron

Tony Heron is Professor of International Political Economy. He is currently serving as a Parliamentary Academic Fellow to the UK House of Commons International Trade Committee. Tony is the author of three books and numerous articles in journals including the European Journal of International Relations, the Review of International Political Economy, New Political Economy, the Journal of Common Market Studies, Third World Quarterly and Global Policy.

Notes

1 We are careful not to equate agency with power and influence but instead define it in social constructivist terms (see Murray-Evans, Citation2015). Agency then can be defined then as the capacity of actors to interpret and navigate their uncertain and often changing external environment (ibid; see also Hay, 2004, pp. 63-64).

2 South Sudan also joined the EAC in April 2016. However, according to insider accounts, beyond official summitry and meetings, South Sudan has yet to actively participate in the regional integration process (Interview 26: Regional Advisor – EAC Development Partner, May 2018, via phone call).

3 An official from the Kenyan government noted in an interview that they believed that ‘memories of mistrust’ and fears that Kenya will come to dominate the EAC still lingered across the region in the present day (Interview 08: Senior Official – Kenyan Government: State Department for East African Community Integration, July 2017, Nairobi).

4 Implementation of the deeper forms of economic integration associated with the EAC’s 2010 common market protocol and 2013 monetary union protocol have also been impeded for these very reasons.

5 Such proposals were referenced in a media interview by the EABC’s former chairperson Kassim Omar. See: https://www.trademarkea.com/news/we-can-produce-competitive-products-eabc-chairperson/.

6 Interview 06: Representative – Kenya Association of Manufacturers, June 2017, Nairobi.

7 Interview 11: Regional Policy Expert, July 2017, Nairobi.

8 These recommendations are paraphrased within the 33rd EAC Council of Ministers meeting report (EAC, 2016b).

9 Interview 24: Representative - Rwanda Private Sector Federation, October 2017, via phone call.

10 Eligibility for AGOA is determined using the World Bank’s classification of a ‘lesser developed country’ (Gross National Product per capita of less than $1,500).

11 Authors own calculations, source: https://agoa.info/data/apparel-trade.html (accessed 2 April 2020).

12 Interview 05: Regional Policy Expert, June 2017, Nairobi.

13 An overview of the EAC Secretariat’s findings can be found in the 33rd EAC Council of Ministers report (EAC, 2016b, pp. 31-32).

14 Interview 06: Representative – Kenya Association of Manufacturers, June 2017, Nairobi; Interview 21: Official – EAC Secretariat, October 2017, via phone call.

15 Interview 21: Official – EAC Secretariat, October 2017, via phone call.

16 Interview 06: Representative – Kenya Association of Manufacturers, June 2017, Nairobi; Interview 26: former Governing Council member - East African Civil Society Organisations Forum, June 2021, via Zoom; Interview 27: Governing Council member - East African Civil Society Organisations Forum, July 2021, via Zoom

17 Interview 06: Representative – Kenya Association of Manufacturers, June 2017, Nairobi.

18 Burundi was not placed under review as its AGOA eligibility had previously been revoked in 2015.

19 Transcripts of evidence submissions can be found here: https://agoa.info/downloads/agoa-out-of-cycle-reviews.html

20 In a letter to the USTR’s Trade Policy Staff Committee in August 2017, SMART highlighted the discrepancies between the testimony of the EAC Secretariat at the USTR review hearing in July 2017, where it was claimed that 2016 tariff increases on used clothing were simply a ‘realignment’ of existing duty rates, and the EAC’s draft strategy for the phase-out (EAC, 2017a), which outlined the intention to increase regional duties to $5000/ton by 2018. Available at: https://www.smartasn.org/SMARTASN/assets/File/advocacy/smart_comments_agoa_review.pdf.

21 Interview 06: Representative – Kenya Association of Manufacturers, June 2017, Nairobi.

References

- Arnell, E. (2016). Cotton-textile and apparel sector in EAC: Value chain analysis & trade concerns: A snapshot. CUTS International. http://www.cuts-geneva.org/pdf/BP-EACGF4-Cotton_Textile_EAC_Value_Chains_and_Trade_Concerns.pdf.

- Ateku, A. J. (2020). Regional intervention in the promotion of democracy in West Africa: An analysis of the political crisis in the Gambia and ECOWAS’ coercive diplomacy. Conflict, Security & Development, 20(6), 677–696. https://doi.org/10.1080/14678802.2020.1854954

- Behuria, P. (2019). Twenty‐first century industrial policy in a small developing country: The challenges of reviving manufacturing in Rwanda. Development and Change, 50(4), 1033–1062. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12498

- Binda, E. M. (2017). The Legal Framework of the EAC. In E. Ugirashebuja, J.E. Ruhangisa, T. Ottervanger & A. Cuvyers (Eds), East African Community law: Institutional, substantive and comparative EU aspects. Brill.

- Briceño-Ruiz, J., & Morales, I. (2017). Post-hegemonic regionalism in the Americas: Toward a Pacific-Atlantic divide. Routledge.

- Brooks, A., & Simon, D. (2012). Unravelling the relationships between used‐clothing imports and the decline of African clothing industries. Development and Change, 43(6), 1265–1290. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.2012.01797.x

- Bünder, T. (2018). How common is the East African Community’s common external tariff really? The influence of interest groups on the EAC’s tariff negotiations. SAGE Open, 8(1), 215824401774823–215824401774814. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244017748235

- Chemengich, M. (2013). Policy research on the Kenyan textile industry, findings and recommendations. African Cotton & Textile Industries Federation (ACTIF). https://agoa.info/downloads/reports/5264.html.

- CUTS International. (2017). Safeguarding regional trade integration in the Buy Kenya, Build Kenya strategy (Action Alert, November 2017). CUTS International. http://www.cuts-geneva.org/pdf/AA%20-%20Safeguarding%20Regional%20Trade%20Integration%20In%20The%20Buy%20Kenya%20Build%20Kenya%20Strategy.pdf

- Davies, P. H. (2001). Spies as informants: Triangulation and the interpretation of elite interview data in the study of the intelligence and security services. Politics, 21(1), 73–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9256.00138

- The East African Community (EAC). (1999). The treaty for the establishment of the East African Community. East African Community Secretariat.

- The East African Community (EAC). (2001). The second East African Community development strategy. East African Community Secretariat. http://repository.eac.int/bitstream/handle/11671/204/2nd%20EAC%20Development%20Strategy.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- The East African Community (EAC). (2002). East African customs union: Information and implications. EAC Reports Database (EAC 382.91676 EAS), Information Resource Centre, East African Community Secretariat.

- The East African Community (EAC) (2004). Protocol on the establishment of the East African customs union. : East African Community Secretariat. https://www.eac.int/documents/category/eac-customs-union-protocol

- The East African Community (EAC). (2007). Report of the 14th ordinary meeting of the Council of Ministers. EAC Reports Database (EAC/CM 14/2007), Information Resource Centre, East African Community Secretariat.

- The East African Community (EAC). (2010). Institutional review of the EAC, organs and institutions. East African Community Secretariat.

- The East African Community (EAC). (2012a). East African Community industrialization strategy: Structural transformation of the manufacturing sector through high value addition and product diversification based on comparative and competitive advantages of the region. East African Community Secretariat. http://repository.eac.int/bitstream/handle/11671/542/Final_EAC_Industrial_Strategy_edited%20final-%20FINAL-17-04-2-12.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- The East African Community (EAC). (2012b). The East African Community industrialization policy 2012-2032: Structural transformation of the manufacturing Sector through high value addition and product diversification based on comparative and competitive advantages of the region. East African Community Secretariat. http://repository.eac.int/bitstream/handle/11671/539/Final%20%20EAC%20Industrialization%20Policy.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- The East African Community (EAC). (2016a). Report of the 17th East African Community summit of the heads of state. EAC Reports Database (EAC/SHS 17/2016), Information Resource Centre, East African Community Secretariat.

- The East African Community (EAC). (2016b). Report of the 33rd East African Community council of ministers. EAC Reports Database (EAC/CM/33/2016), Information Resource Centre, East African Community Secretariat.

- The East African Community (EAC). (2016c). East African Community gazette, vol. AT1 – no.5, 30th June 2016. East African Community Secretariat.

- The East African Community (EAC). (2017a). Draft EAC strategy/action plan for the phase-out importation of second-hand clothes/shoes within the period 2017-2019. East African Community Secretariat.

- The East African Community (EAC). (2017b). East African Community gazette, vol. AT.1 – no. 8, 30th June 2017. East African Community Secretariat.

- The East African Community (EAC). (2018a). 36th meeting of the council of ministers. EAC Reports Database (EAC/CM/36/2017), Information Resource Centre, East African Community Secretariat.

- The East African Community (EAC). (2018b). East African Community gazette, vol. AT.1 – no. 4, 26 February 2018. East African Community Secretariat.

- The East African Community (EAC). (2019). East African Community gazette vol. AT. 1 – no. 10, 30 June 2019. East African Community Secretariat.

- The East African Community (EAC). (2020). East African Community gazette vol. AT. 1 - no. 10, 30 June 2020. East African Community Secretariat.

- Essa, A. (2018, October 5). The politics of second-hand clothes: A debate over “dignity”. Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/politics-hand-clothes-debate-dignity-181005075525265.html.

- Fawcett, L. & Hurrell, A. (Eds.) (1996). Regionalism in world politics: Regional organization and international order. Oxford University Press.

- Fourie, E. (2014). Model students: Policy emulation, modernization, and Kenya’s Vision 2030. African Affairs, 113(453), 540–562. https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adu058

- Frazer, G. (2008). Used-clothing donations and apparel production in Africa. The Economic Journal, 118(532), 1764–1784. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2008.02190.x

- Gamble, A. & Payne, A. (Eds.) (1996). Regionalism & world order. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Gibb, R. (2009). Regional integration and Africa’s development trajectory: Meta-theories, expectations and reality. Third World Quarterly, 30(4), 701–721. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436590902867136

- The Government of Kenya. (2012). Kenya national AGOA strategy: Supporting the ability of Kenyan firms to successfully sell into the US market, leveraging every opportunity that AGOA provides. Government of Kenya.

- The Government of Rwanda. (2015). Domestic market recapturing strategy. Government of Rwanda. Available at: http://www.minicom.gov.rw/fileadmin/minicom_publications/Planning_documents/Domestic_Market_Recapturing_Strategy.pdf.

- The Government of Tanzania. (2016). Cotton-to-clothing strategy 2016–2020. http://unossc1.undp.org/sscexpo/content/ssc/library/solutions/partners/expo/2016/GSSD%20Expo%20Dubai%202016%20PPT/Day%202_November%201/SF%204_Room%20D_ITC/Value%20chain%20roadmaps/Tanzania/Tanzania%20Cotton%20to%20Clothing%20Strategy%20.pdf.

- Harrison, G. (2019). Authoritarian neoliberalism and capitalist transformation in Africa: All pain, no gain. Globalizations, 16(3), 274–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2018.1502491

- Hartmann, C. (2017). ECOWAS and the restoration of democracy in The Gambia. Africa Spectrum, 52(1), 85–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/000203971705200104

- Hay, C. (2002). Political analysis: A critical introduction. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hay, C. (2006). Constructivist institutionalism. In S. A. Binder, R. A. W. Rohdes & B. A. Rockman (Eds), The Oxford handbook of political institutions (pp. 56–74). Oxford University Press.

- Hay, C. (2016). Good in a crisis: The ontological institutionalism of social constructivism. New Political Economy, 21(6), 520–535. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2016.1158800

- Hay, C., & Rosamond, B. (2002). Globalization, European integration and the discursive construction of economic imperatives. Journal of European Public Policy, 9(2), 147–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760110120192

- Hazlewood, A. (1979). The end of the East African Community: What are the lessons for regional integration schemes. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 18(1), 40–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.1979.tb00827.x

- Herbst, J. (2007). Crafting cooperation in Africa. In A. Acharya & A.I. Johnston (Eds), Crafting cooperation: Regional international institutions in comparative perspective (pp. 129–144). Cambridge University Press.

- Heron, T. (2012). The global political economy of trade protectionism and liberalization: Trade reform and economic adjustment in textiles and clothing. Routledge.

- Heron, T., & Murray-Evans, P. (2017). Limits to market power: Strategic discourse and institutional path dependence in the European Union–African, Caribbean and Pacific Economic Partnership Agreements. European Journal of International Relations, 23(2), 341–364. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066116639359

- Hettne, B., Inotai A., & Sunkel, O. (Eds.) (1999). Globalism and the new regionalism. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hickey, S. (2012). Beyond ‘poverty reduction through good governance’: The new political economy of development in Africa. New Political Economy, 17(5), 683–690. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2012.732274

- Hickey, S. (2013). Beyond the poverty agenda? Insights from the new politics of development in Uganda. World Development, 43, 194–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2012.09.007

- Ingham, K. (1963). A History of East Africa (3rd ed.). Frederick A. Praeger Publishers.

- Jacob, T., & Pedersen, R. H. (2018). New resource nationalism? Continuity and change in Tanzania’s extractive industries. The Extractive Industries and Society, 5(2), 287–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2018.02.001