Abstract

Saudi Arabia's Public Investment Fund (PIF) has grown from marginal player to the most important economic actor in the Kingdom since 2015. Nevertheless, we know surprisingly little about the political economy of the PIF revamp. Against an unfavorable macroeconomic backdrop, I argue that shifts in PIF organization and orientation are fundamentally driven by the centralization of power within the circles of the Saudi ruling family since the rise of Mohammed bin Salman (MBS). The fund's governance framework and network of insiders forming the board of directors mirror the concentration of authority around MBS. In turn, PIF domestic activities shifted from scattered investment patterns associated with the competing influence of senior decision-makers to a highly authoritative and personalized strategy. Moreover, the PIF's response to COVID-19 further exemplifies the turn from a conservative strategy toward a short-term oriented approach to sovereign wealth management. Going beyond macro-level economic and institutional dynamics, the article introduces the role of political agency in SWF choices by stressing how political actors and the distribution of power within ruling elites shape SWFs. The article thus adds to the scholarship on domestic drivers of SWFs and contributes to debates surrounding the interplay between states and markets under processes of financialization.

Introduction

On April 23, 2020, a virtual event of the Future Investment Initiative (FII) hosted by Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund (PIF) brought together a group of global investment experts to discuss the challenges of governance, macroeconomics and technology associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. Over the conference, Yasir Othman Al-Rumayyan, governor of the PIF, discussed the SWF’s approach and declared to the online audience: ‘You don’t want to waste a crisis…So for us, definitely we are looking into any opportunities’ (England & Massoudi, Citation2020). Two weeks after the conference, the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) filings disclosed that the PIF assumed stakes in multiple companies over the first quarter (Q1) of 2020, growing the PIF's portfolio of US-listed assets from $2.2 billion to $10.1 billion. However, as markets rebounded in the second quarter (Q2), the PIF quickly exited most of its ventures in US-listed firms assumed over the previous quarter (SEC, Citation2020a, Citation2020b). The Saudi SWF reacted to the COVID-19 economic shock not by following its stated strategy to invest with a low-risk and long-term investment horizon but by opportunistically acquiring undervalued stocks in developed markets to provide immediate returns. The PIF’s speculative shopping spree amid the coronavirus outbreak is part of a broader strategic reorientation of the fund’s activities since 2015.

The PIF was created in 1971 to support newly created state-owned enterprises but ultimately remained a marginal player in the Kingdom. Since 2015, the fund is becoming the single most important actor in Saudi Arabia's economy and arguably the fastest-growing sovereign wealth fund (SWF) in the world. The PIF's total assets under management nearly quadrupled since 2015, growing from $150 billion to $580 billion in 2022, making the fund as the 6th-largest (PIF, Citation2021; SWFI, Citation2022). Beyond the global financial markets, the SWF established more than 30 firms in 10 sectors, including military industries, power and utilities, real estate and tourism. The PIF is the centrepiece of ambitious projects such as the $500 billion futuristic mega-city NEOM and the Sudair Solar project, one of the world's largest solar plants by capacity (ACWA Power, Citation2021; Scheck et al., Citation2019). The sovereign fund, which had around 40 employees in 2016, now has a staff count surpassing 1000 since 2020 (Azhar, Citation2020). Nevertheless, we know surprisingly little about the political economy of the PIF revamp. Why did the Saudi government significantly upgrade the PIF since 2015?

Since the global financial crisis and, more recently, the 2014 oil price crash, various countries created sovereign development funds like the PIF to pursue economic diversification and national industrial policy. In contrast to the predominant paradigm of SWFs as primarily created to manage current account surpluses or commodity price booms (e.g. Aizenman & Glick, Citation2008; Al-Hassan et al., Citation2013; Das et al., Citation2009), sovereign funds have increasingly become ‘demand-driven’, motivated less by the need to capture and invest surplus wealth than by driving nation-building agendas (Dixon, Citation2022; Schena et al., Citation2018). Such trends bring the relationship between domestic politics and SWF choices into sharp relief. Hence, a growing body of work suggests that the logic driving SWFs is fundamentally political and domestically oriented (Braunstein, Citation2017, Citation2019; Hatton & Pistor, Citation2011; Helleiner, Citation2009; Shih, Citation2009). However, whereas this literature acknowledges that state power is closely tied to SWFs, we know little about how this relationship works; that is, the concrete mechanisms of how political agency influences SWF decision-making.

From this perspective, the article takes on the Saudi case to develop the literature on domestic drivers of state investment funds by unpacking how political actors, their interests and the distribution of power within the ruling elite carry significant implications for SWFs’ choices. By analyzing both PIF’s institutional design and investment initiatives, I argue that the concentration of political authority moulds PIF choices as cross-temporal variation in institutional design and investment policy follows the change in state fragmentation. Without rejecting the quest for risk-adjusted returns and a market-oriented logic at the firm level, the PIF’s structure and investment strategy are enmeshed in elite politics characterized by a centralization of royal authority around Mohammed bin Salman (MBS) in the post-2015 political landscape. In its historical-institutional approach, this article looks at the period of regime change initiated in 2015 to illustrate how the centralization of political and economic power within the circles of the Saudi ruling family since the rise to power of MBS is associated with shifts in the PIF’s organization and investment strategy. The analysis relies on primary sources, including the Capital IQ and Tadawul databases, U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) filings, state documents and publications, in addition to data from company websites. Moreover, it draws on academic literature and business-oriented news reports.

The article contributes to three interrelated streams of literature. The PIF's swift expansion and its central role in the Kingdom's economy led scholars to raise concerns about the extent to which the SWF is more than an engine of growth but might also evolve as a political tool at the hands of the ruling elite (Seznec & Mosis, Citation2018; K. E. Young, Citation2020). Nevertheless, the political drivers underlying the PIF’s expansion receive little systematic academic attention. The article closes this empirical gap by shedding light on the interplay of elite politics and institutional formation behind the management and allocation of sovereign wealth in the Middle East’s largest economy.

The research also speaks to a growing literature treating SWFs not as mere products of macroeconomic forces but as manifestations of power distribution in the political landscape (Braunstein, Citation2017, Citation2019; Schwartz, Citation2012; Shih, Citation2009). As the role of political agency in SWF choices is often obscured by the analysis of generic groups such as ‘state’ or ‘society’, I stress the role of political agents, coalitions and rivalries within the Saudi royal circles in SWF design and use. Accordingly, the Saudi case casts light on the concrete mechanisms of how domestic politics influence SWF governance and strategy by demonstrating how the personalized rule and institutional design under MBS also transform SWF decision-making.

The article also seeks to contribute to broader IPE debates surrounding the interactions between states and the global financial market. Recent research sought to identify the sources and outcomes of patient capital (Deeg & Hardie, Citation2016; Lerner & Ivashina, Citation2019; Thatcher & Vlandas, Citation2016). This literature identifies SWFs as major pools of patient capital based on their focus on long-term, apolitical investments alongside low pressure for short term profits. While SWFs have become significant providers of patient equity investments in various instances, this article moves beyond the putative conceptualization of SWFs as pure case studies of long-term asset allocators by shifting the analytical focus towards the players behind sovereign funds and the political relationship between actors, highlighting how and when political agency and political choice in particular institutional configuration can produce incentives towards impatience and politicization of investment decisions of state investment funds.

The article is structured as follows. The subsequent section discusses the article’s framework rooted in the perspective of SWFs as inherently political institutions. Thereafter, as a first step, I will engage with the conjuncture of the 2015 regime change in more detail, addressing the age of King Salman and the rise to power of his son MBS. Then, in a chronological review, the article moves to illustrate how changes in the balance of power in 2015 prompted a shift in the PIF’s institutional design and investment initiatives in the Kingdom and abroad. As a second step, the article explores contrasting theory-informed explanations of SWF design and use grounded in macroeconomic indicators. Finally, the last section offers conclusions.

Internal political dynamics and sovereign wealth funds

A growing body of international political economy (IPE) literature illustrates how SWFs are outcomes of policy decisions, themselves interwoven in a set of particular historical and political relations and institutions. Braunstein (Citation2017, Citation2019) provides a systematic and comparative causal analysis of how legacies of state formation and institutional settings shape SWFs in Hong Kong, Singapore and the small Gulf states (Kuwait, Qatar, Abu Dhabi and Bahrain). The distribution of power among groups in state-society relations expressed by different levels of concentration of decision-making power, state autonomy, and organizational properties of the private sector emerges as systematically related to the different types and use of SWFs. A centralized and autonomous state facing weakly mobilized private industrial interests is expected to allow the creation of developmental SWFs dominating the industrial landscape like the PIF.

The PIF operates in a political landscape characterized by decision-making structures highly centralized around the Al Saoud and a state apparatus mostly autonomous from business interests. Even if the Saudi private sector significantly developed its capacity, business tends to act as a client and a policy-taker (Hertog, Citation2010b). Business interest representation is still delegated to a small number of tightly supervised and compartmentalized institutions such as the Saudi Chamber of Commerce and Industry and Majlis Ash-Shura. Inclusion to formal institutions of business representation is carefully monitored by the government (Hertog, Citation2006; Kraetzschmar, Citation2015). Saudi Arabia's state dominates politics and policymaking and leaves little space for the emergence of organized groups in society and instead favours personalized networks based on patron-client relationships (Hertog, Citation2010b). Yet, if the highly centralized political context seems to have allowed the Saudi leadership to create a developmental SWF, how domestic politics explain SWF governance and strategy remain obscure.

A related group of authors points to the crucial role of self-interested ruling elites in sovereign wealth management. The assumption is that SWFs are tools to consolidate their political dominance against internal and external threats. The governance framework provides administrative instruments to deal with intra-elite power balancing and ensures that sovereign wealth management is under the ruling elite's control (Hatton & Pistor, Citation2011). On the other hand, ruling elites can leverage SWFs to take minority stakes in companies controlled by the elite and their allies or controlling stakes in financial institutions to shape the structure of economic development (Grigoryan, Citation2016; Hatton & Pistor, Citation2011; Schwartz, Citation2012). Meanwhile, building an international portfolio allows a regime to implement investment strategies to satisfy immediate demands, protecting the economic and political status quo (Dixon, Citation2022).

However, ruling elites are not homogeneous groups; multiple agents may claim authority over an institution, thus creating inconsistent policies or a situation where various competing agents are trying to gain an advantage in a game of power (Carney, Citation2018). Indeed, the Saudi polity comprises several segmented circles of power, simultaneously competing and cooperating to perpetuate the ruling family’s rule (Al-Rasheed, Citation2005; Herb, Citation1999). In that sense, Shih (Citation2009) draws attention to regime unity as the fundamental political dynamic shaping SWF decision-making. In a unified regime (when leadership change is unlikely), the leadership’s perception of threat tends to decrease. Thus, SWFs may pursue long-term and profit-maximization behavior. In contrast, in fragmented regimes where constitutional procedures for leadership transition are vague, SWFs tend to become tools of survival. While SWFs might be institutionalized enough to pursue market-oriented returns, 'there may be a preference for short-term advantages gained through managing an SWF, whether it be quick profit or a way to pay off a politically powerful actor' (Shih, Citation2009, p. 331). However, managers may opt for a conservative approach to mitigate investment losses and avoid exclusion in the event of a shift in leadership.

Building upon such existing literature, this article conceptualises SWFs as byproducts of interactions, contested or otherwise, between various political forces that shape decisions regarding the management and allocation of sovereign wealth. It has been argued that the interplay between conflicts and coalitions among a small number of princes and commoners within circles of the royal family and institutional change at previous historical junctures shaped the form of the modern Saudi state. During the state’s expansion of the 1950s and 1960s, princes were provided with roles and portfolios according to seniority while satisfying their ambitions. Institutions were often adjusted to the authority and status of the agent leading them or even created from scratch to strenghten or undermine specific players (Hertog, Citation2010b; Yizraeli, Citation1998). In the same way, it is received wisdom in historical institutionalism that shifts in socioeconomic contexts or the political balance of power can generate a situation in which old institutions are put in the service of different ends as new actors come into play and pursue their (new) goals through existing institutions. At certain definitive moments in history, institutions can be created or expanded to give the agent an advantage in games of power (Collier & Collier, Citation1991; Thelen & Steinmo, Citation1992). The theoretical point of departure here is that variation in SWF form and function can, to a large extent, be explained by shifts in intra-elite political dynamics. Nonetheless, the agency of political actors over SWF choices in existing approaches is largely obscured by analysis of organizing features of aggregates including ‘state’ and ‘regime’. Hence, even if IPE scholarship acknowledges that state power and SWF choices are intimately related, we need a microfoundation of how domestic politics influence SWF decision-making.

My proposal is to disaggregate the state for a finer-grained analysis of sovereign wealth management. This logic suggests distinguishing how political agency (the players, their interests, and the distribution of power among them) and dynamics of political contexts within historical institutional constraints shape SWF design and use. Hence, I approach the shift in the PIF’s trajectory using a historical-institutional analytical framework. The article first unpacks the historical political legacies and shifts within the circles of the Saudi political elite following the 2015 regime change. Then, through a chronological research design, the article reviews the PIF pre- and post-2015 governance framework (organizational design, management and responsibilities) and investment strategy (time horizon, asset classes and risk appetite) to explore how the shift in the political balance of power since 2015 affected the fund.

The centralization of royal authority in the post-2015 Saudi political landscape

In the early hours of January 23, 2015, King Abdullah passed away, and within hours, crown prince Salman became King. Before 2015, Saudi Arabia’s political landscape was portrayed as a system of segmented and hierarchical centres of power. These institutional fiefdoms were controlled by different factions within the ruling family, each with a life of its own, and allowed the emergence of patronage appointments and rent-seeking clientelist networks allied to one senior prince or another (Al-Rasheed, Citation2005; Hertog, Citation2010b). This institutional inheritance gave veto power to various factions (royal, bureaucratic or others) with overlapping jurisdictions, often resulting in bureaucratic resistance or interagency disputes over policymaking and reforms (Hertog, Citation2010b).

However, King Salman's reshuffle of government positions underlines how, across the Saudi government, high-ranking officials now owe their position to King Salman and crown prince MBS and not to a myriad of senior princely patrons. The crown prince consolidated control over the top level of critical political and economic institutions through a trusted inner circle while presenting himself as the architect of Saudi Arabia's top-down nation-building strategy, Vision 2030. All influential (or potentially influential) relatives were marginalized into an outer circle and stripped of their status and influence (Davidson, Citation2021). The age of King Salman marks a centralization of top-level regime structures around the crown prince MBS.

On April 25, 2016, MBS, then deputy crown prince, unveiled Vision 2030. The wide-ranging top-down socioeconomic reform agenda advertises the pillars driving the Kingdom towards a post-oil economy, all attributed to the individual vision of a new leadership embodied in MBS. Over the following months, King Salman abolished by royal decree a dozen Supreme Councils involved in strategic sectors to be replaced by a single overarching institution, the Council of Economic and Development Affairs (CEDA), which was subsequently placed under MBS’s direction to oversee the Kingdom's diversification efforts (Al-Rasheed, Citation2021; Rundell, Citation2021).

In parallel, King Salman reorganized the Council of Ministers; only Salman remains as a second-generation prince, and various princes were replaced either by technocrats or younger princes with no power base of their own (Rundell, Citation2021). The Ministry of Foreign Affairs, a stronghold controlled by Faisal bin Abdulaziz Al Saoud (King from 1964 to 1975) between 1930 and 1975 and his son Saud (from 1975 to 2015), was placed under Faisal bin Fahran Al Saud, who gained access to MBS’ inner circle by way of his company, Shamal Investment Company, a supplier to MBS’s Ministry of Defence (Al Jazeera, Citation2019; Davidson, Citation2021; Rundell, Citation2021). In June 2017, King Salman issued a royal decree to replace Crown Prince Mohammed bin Nayef (MBN) and advanced MBS from deputy crown prince to crown prince (Al-Rasheed, Citation2018; Hubbard, Citation2020). Moreover, MBN was dismissed from his well-established and influential position as Minister of Interior, a position he held from 2012 to 2017, and his father Nayef bin Abdulaziz Al Saoud had held from 1975 to 2012. Abdulaziz bin Saud Al Saud, known as particularly close to MBS, replaced MBN as Minister of Interior (Davidson, Citation2021). Furthermore, King Salman amended the Basic Law of Government to ensure a shift towards primogeniture as the core principle for succession. This solidifies MBS's position in the prospect of a transition to third-generation leadership as Salman is set to be the last second-generation King (Al-Rasheed, Citation2018).

Finally, on November 4, 2017, eleven senior princes and hundreds of businessmen were detained in Riyadh’s Ritz Carlton. Detainees included the wealthy entrepreneur Prince Alwaleed bin Talal and the late King Abdullah’s sons Mishaal, former governor of the Mecca region, Mit’ib, head of the powerful National Guard, and Turki, the former governor of Riyadh, as they still commanded significant followings. In the wake of the event, Abdullah bin Bandar replaced Mit'ib as the head of the powerful National Guard and thus ended the separation between the Ministry of Interior, National Guard and Ministry of Defence, which historically reported to separate senior princes (Davidson, Citation2021; Hope & Scheck, Citation2020; Rundell, Citation2021). The crown prince presented this measure as an anti-corruption crackdown, but in the context of the shift in succession and government reshuffle, the selective nature of the event instead points to an attempt to defuse intra-elite contestation from other senior princes and their related allies and gatekeepers (Al-Rasheed, Citation2021).

MBS simultaneously became crown prince, deputy prime minister, Minister of Defence, and Chief of the Royal Court. Moreover, the Saudi crown prince is the figurehead of Vision 2030, thereby chairman of CEDA and the PIF, which indirectly grants MBS control over most civilian ministries and state-owned enterprises and assets. Al-Rasheed (Citation2018) claims that ‘no other prince has ever held as many key positions at such a young age as MBS. Even at the height of creating a centralized state, King Faysal (d.1975) did not hold so many responsibilities’ (p. 46).

In a chronological overview, the following section will unpack how the institutional changes and power shifts among the ruling elite in the post-2015 political landscape shaped the PIF’s governance framework and investment strategy. First, the article explores the history of the PIF from its creation in 1971 until 2015, then proceeds to analyze the fund's governance framework and investment strategy in the Kingdom and over the global financial market following the 2015 regime change.

Political interests, regime change, and PIF activities

The PIF from 1971 to 2015

The PIF was initially established in 1971 under the Royal Decree N° M/24 as a development fund to provide capital for new state-owned enterprises in a period of rapid institutional expansion. From its establishment in 1971 to 2015, the PIF was under the umbrella of the Ministry of Finance (MoF). The fund operated with around 40 employees and acted as the investment arm of the ministry under a manager model, where a separate fund was set up to manage assets under a mandate given by the MoF. As a result, strong ties linked the two institutions; the fund was embedded within the ministry, and the PIF's managing director sat immediately next to the minister's office (Seznec & Mosis, Citation2018).

By the end of the 1970s, the fund's principal investments were in the Saudi Basic Industry Corporation (SABIC), while also growing to be the main shareholder in the Saudi Public Transport Company (SAPTCO), the mining and aluminium company Ma’aden and the national shipping carrier Bahri (Seznec & Mosis, Citation2018). SABIC became the second most valuable chemical company globally, while Ma’aden is among the ten largest mining companies judged by market capitalization (BrandFinance, Citation2021; Ma’aden, Citation2020). The PIF also provided various loans to the state-owned Petromin, a national oil company established in 1962 to replace the US-owned Aramco. For instance, the PIF attributed approximately $1 billion in loans to facilitate the construction of the East-West Crude Oil pipeline (McPherson‐Smith, Citation2021). Petromin eventually fell from grace between 1983 and 1986, Aramco assumed control over the company between 1993 and 1996 and the company was dissolved in 2005 (Hertog, Citation2008). Beyond non-oil diversification objectives, the contrasting PIF ventures in Petromin and SABIC reveal how earlier investments were intertwined with rivalries and coalitions among high-level elite players, technocrats and a network of key merchant families.

The PIF-backed Petromin was under technocrats fostered by King Faisal (1964-1975): the oil minister Ahmad Zaki Yamani and his right-hand man Abdulhadi Taher, Petromin’s governor (Vitalis, Citation2007). Petromin became the primary vehicle for industrialization with activities encompassing oil refineries in the Kingdom and abroad, oil and gas exploration, glass and steel plants, power generation projects, distribution of refined products within Saudi Arabia and even its own shipping operations (Hertog, Citation2008). Following the death of Faisal in 1975, crown prince Fahd was given great administrative liberty by new King Khaled (1975-1982) and thus sought to foster technocrats closer to him than Yamani and Taher. The newly established Ministry of Industry and Electricity (MOIE) under Fahd’s client, Ghazi al-Gosaibi, restricted Petromin’s activity as the MOIE took control of petrochemicals, mining, and other heavy industries. Large numbers of Petromin projects were transferred to the MOIE to be evaluated by the Industrial Studies and Development Center under the eye of Abdulaziz Zamil. Every Petromin project was reformulated or dismissed. Then, the MOIE established SABIC in 1976 to consolidate control over petrochemicals and other heavy industry projects. SABIC was capitalized at $2.8 billion, with 70% coming from the PIF, with Gosaibi standing as chairman and Zamil as CEO (Hertog, Citation2008).

The fund’s earlier investments in Petromin and SABIC reflect a political landscape consisting of overlapping bureaucratic strongholds acting as veto players in decision-making, each controlled by factions of the ruling family and their related networks infiltrating the state apparatus and the economy. In this vein, PIF activities were subject to a constellation of distinct and competing political forces leading to reactive and scattered investment patterns. Between 1971 and 2015, the PIF played a central role in some of the most ambitious and successful state-led economic development projects but ultimately displayed uncoordinated and targeted investment patterns related to the fragmented regime structure.

From 1971 to 2015, the PIF had been relegated to domestic investments, while the country’s central bank, the Saudi Arabian Monetary Authority (SAMA), was the central agency in charge of managing and investing Saudi sovereign wealth. SAMA was created in 1952 as US advisor Arthur N. Young convinced King Abdulaziz (1932-1953) and Abdullah Sulaiman, the King’s close advisor and finance minister, of the need for banking and monetary regulations (A. N. Young, Citation1983). Following its creation, SAMA’s charter and the use of foreign technocrats, based on a claim that no Saudis would have had the required training, strengthened its autonomy. In contrast to other agencies, SAMA was insulated from the regular civil service structures and possessed distinct payment and recruitment mechanisms (Hertog, Citation2010b; A. N. Young, Citation1983). SAMA managed two strictly separated portfolios: a reserve portfolio to manage the liquidity requirements of a central bank and an investment portfolio with a stabilization mandate under SAMA Foreign Holdings. SAMA displayed a passive investment strategy with the majority of its portfolio invested in highly liquid and low-risk assets, mainly US Treasury bonds (Banafe & Macleod, Citation2017; Bazoobandi, Citation2013)1. A significant portion of its assets was short-term oriented, reflecting a conservative investment orientation to satisfy the demands for liquidity and safety (Alsweilem et al., Citation2015; Banafe & Macleod, Citation2017).

Furthermore, multiple ministries and other state agencies possessed their own foreign investment vehicles, each with their own investment strategy, whereas several ministers embedded their private investment funds within the overall structure of ministries2. In this sense, Smith Diwan’s (Citation2009) study of the creation of Sanabil-al-Saudia in 2008 shows how Saudi Arabia’s first attempt at creating an official SWF was predominantly driven by King Abdullah’s (2005-2015) attempt to subdue intra-state rivalries and manage the Kingdom’s fragmented investment activities. Nevertheless, the fund rapidly fell from grace in the face of sustained interagency disputes and was subsequently absorbed by the PIF (Sanabil Investment, Citation2020). From 1971 to 2015, sovereign wealth management under SAMA was associated with a conservative international investment orientation. The institutional fragmentation of the Saudi political landscape created interference in establishing a coherent national investment strategy and a separate government-owned investment vehicle acting as a distinct sovereign fund operating across the global financial markets.

The post-2015 PIF: form follows family

In 2015, Saudi leaders started to grant more authority to the PIF. As part of these steps, on March 23, 2015, the Council of Ministers issued the resolution N°270 formalizing the shift in the fund's oversight from the MoF, known for being secretive and insulated (Hertog, Citation2010b) to CEDA under the control of MBS. The PIF's institutional framework transitioned from the manager model to the investment company model as the PIF is now set up as a separate investment company that legally owns the assets it manages (PIF, Citation2017a). The SWF’s board was reconstituted and MBS placed as chairman. In addition, the political network of high-level elite players forming the board of directors and the fund’s governance framework reflects the centralization of authority around the crown prince and his inner circle.

Excluding MBS, of the other eight board members, three are members of the Council of Ministers, and a total of six board members control different portfolios, including two ministers of state, the minister of investment, commerce, tourism and finance. On an informal level, the minister of finance, Mohammed Abdullah Al-Jadaan, is often described as one of MBS’s closest associates, while the advisor Al-Tuwaijri and Al-Shaikh, a minister of state, are known as trusted advisors within the crown prince’s tight inner circle (Davidson, Citation2021). Finally, Yasir Othman Al-Rumayyan, governor of the PIF, is the technocratic agent leading the SWF. Al-Rumayyan is also chairman of Saudi Aramco, Ma’aden, and Sanabil Investment. He also sits on various boards of directors, including the Red Sea Company, Qiddiya, and PIF's key foreign holdings such as Uber Technologies, the UK-based SoftBank's chip designer Arm Holdings, and as board director of SoftBank Group (Argaam, Citation2018; SoftBank Group, Citation2020). On a more informal level, Al-Rumayyan began his career as a local banker but began to appear as a key member of MBS's inner circle in 2015 (Davidson, Citation2021; Hope & Scheck, Citation2020). Al-Rumayyan is an advisor to the Royal Court and the General Secretariat of the Cabinet of Ministers.

To support the expansion of PIF activities, the initial staff of around 40 employees grew to 450 in 2019 and surpassed 1000 by the end of 2020 (Argaam, Citation2020; Azhar, Citation2020). Insulated from the regular civil service’s employment structures more conducive to patronage, the fund has its own competitive recruitment process and remuneration structures. Nonetheless, competence has been highlighted as a significant issue in many Gulf SWFs (Clark & Monk, Citation2012). The PIF launched its Academy for Training and Development in partnership with HEC Paris, the University of California Berkeley and AMT Training (PIF, Citation2021). This strives to build the skillset of local employees either going into junior or senior positions to drive the PIF's increasingly sophisticated investment activities efficiently.

However, the governance structure is still conducive to influence from MBS over day-to-day operations and promotes his grip on the mechanisms to fill senior management positions through his ascendency over the board of directors and his position as chairman of the Executive and Remuneration Committees. Reports from late December 2018 and March 2020 show that various senior expatriate PIF executives (including two heads of strategy, head of legal, head of risk, chief of public investments, and private-equity associate) resigned and issued remarks on the lack of analysis and consultation in addition to the micromanagement of MBS. For instance, Eric Ebermeyer left in 2018 just weeks after joining as the fund's head of strategy, bemoaning MBS’s micromanagement, unclear strategy and an unstable work environment. Cyrille Urfer followed Ebermeyer. Urfer led the PIF's investments in global public markets and hedge funds but claimed that ‘ideas and deals are driven from the top down’ (Jones, Citation2018). In a further statement, he added: ‘at the end of the day, the owner and the one who takes the decision is the Saudi government, and the PIF is the tool that is supervising the execution of these projects’ (Azhar & Kalin, Citation2019).

Nevertheless, proximity to the ruling group does not automatically lead to inefficiency. The successes of Gulf state-owned enterprises (SOEs) like the SABIC and SAMA in relation to other rentier states are attributed, among other things, to their form of 'pockets of efficiency', or in other terms, their autonomy associated with the direct protection of high-level unified principals in the ruling group. Being insulated from the rest of the state apparatus, high-ranking technocratic managers reporting directly to the ruler, crown prince or other senior royals can focus on market-oriented management outside of political and bureaucratic predation from senior bureaucrats and minor royals (Hertog, Citation2010a). Nonetheless, the PIF does not enjoy substantial decisional autonomy from the regime leadership, a fundamental determinant of pockets of efficiency. The concentration of royal authority around the crown prince from 2015 prompted a process of centralization among decision-making structures around a closely knit coalition of senior royals and technocrats reflected in the PIF’s governance structure. SWF institutional design appears as an instrument of legitimacy and control as much as an attempt to consolidate the appropriate governance of sovereign wealth management.

The post-2015 PIF in Saudi Arabia’s economy

Before 2015, the PIF’s activities were limited to supporting emerging SOEs under the pressure of multiple rival senior princes resulting in dispersed investment patterns. As the government redefined the institutional structure of the PIF, the fund's mission evolved to act as the catalyst for economic development and enabler of the private sector (PIF, Citation2021). The PIF's recent domestic ventures demonstrate a qualitative shift in the fund's domestic investment strategy driven by the centralization of royal authority around MBS. The SWF is now the central engine of growth in the Kingdom’s economy driven by the ambition of MBS. The ruling elite now mobilizes the PIF to achieve growth and structural transformation as part of a nation-building program and explicit socioeconomic goals operationalized through targeted sectors or intrusive wide-ranging state interventions across the Kingdom’s economy.

The SWF is now the largest investor on the Tadawul. The PIF simultaneously perpetuates the state’s authority over the structure of economic development through control of financial institutions and historical growth sectors such as building materials, petrochemicals, and mining. For instance, the PIF is the main shareholder in the largest Saudi banks, the Saudi National Bank, the Riyad Bank and Alinma Bank, which together hold 48% of market shares3 (Aljazira Capital, Citation2020b). In the cement industry, the SWF holds the majority of shares in Southern Province Cement Company, Qassim Cement, Yanbu Cement, and Eastern Cement, totalling 37% of market shares (Aljazira Capital, Citation2020a)4. In mining, the PIF is the largest shareholder in the world-leading Ma'aden, with 67,18% of outstanding shares5. This support of the domestic equity market protects the domestic economy from volatility but also favors specific business players. Through interlocking directors and shareholders, these PIF-targeted firms are connected to privately-owned conglomerates controlled by prominent business families benefiting from historical ties with the Al Saoud, including the Al Rajhi, Alissa, Alireza, Al Zamil, Al Muhaidib and Juffali Groups6.

However, the giga-project and sector development investment pools distinguish the post-2015 shift in domestic PIF activities. While the fund gained the operating right to the King Abdullah Financial District, the PIF is also the primary developer of the flagship NEOM project, the entertainment destination Qiddiya, and the luxury tourist destination The Red Sea and Soudah. (PIF, Citation2017b; Saudi Press Agency, Citation2021b). State-led large-scale projects are not a novelty in the Kingdom. Rather, what differentiates the age of King Salman is the centralization of decision-making structures underpinning the development of such projects under the auspices of MBS through the PIF.

Past ventures like the cluster of economic cities under the King Abdullah Economic City (KAEC) banner got entangled in the pitfalls of interagency feuds and competing interests to ultimately stall (Hertog, Citation2010b). In contrast, the PIF is the primary financier and sole developer of projects and thus allows the crown prince to override the multiple entrenched veto players in Saudi economic policymaking and drive forward his agenda. The giga-projects also diverge from typical SWF equity investments and offer more than economic diversification and technological progress. They offer the ability to rearrange the geospatial and social environment and become concrete manifestations of the intersection between PIF investments and the ruling elite’s political-economic strategy personified by MBS (McPherson‐Smith, Citation2021). Furthermore, the closed joint-stock companies charged with developing the giga-projects are chaired by MBS and fully owned by the PIF. They consolidate the crown prince’s oversight and provide limited space for private sector involvement (Al Arabiya, Citation2020; Arab News, Citation2018; Saudi Press Agency, Citation2021b).

The PIF also holds the role of investor, developer, and operator of completely new ecosystems across various key domains identified as promising economic sectors by the Saudi leadership via Vision 2030. For instance, the Saudi SWF launched the Saudi Military Industries Company (SAMI) in 2017. Chaired by Ahmed Aqeel Al-Khateeb, member of the PIF’s board and minister of tourism, SAMI localizes the Kingdom's military spending by developing technologies and manufacturing products in aeronautics, land systems, defence electronics, weapons and missiles (SAMI, Citation2021). SAMI launched SAMI L3 Harris Technologies, a joint venture with L3Harris Technologies, one of the world's largest aerospace and defence systems manufacturers (Saudi Press Agency, Citation2021a). As part of the effort to enhance the Kingdom’s tourism and entertainment opportunities, the PIF established the Saudi Entertainment Ventures Company (SEVEN) as its investment arm to expand and diversify entertainment and cultural activities such as concerts by various high-profile artists and growing festivals.

The swift development of the military, entertainment, culture, and tourism sectors help to some extent, diversify the Kingdom's economy. However, when one considers PIF subsidiaries almost exclusively source expertise, events and partners from abroad, the decision to create new ecosystems appears to provide quick and apparent manifestations of structural transformations and nation-building fitting within the broader narrative of the new leadership as an embodiment of a new era of diversification, openness and prosperity (Al-Rasheed, Citation2021). Moreover, the lucrative military industry, historically under the umbrella of the Ministry of Defence, which 'enabled princes to sign massive weapons contracts with the United States and other Western countries to underpin alliances and networks of middlemen', remains under close government control through the PIF (Hubbard, Citation2020, p. 31).

From buying bonds to buying the dip

In support of its considerable domestic investments, the Saudi leadership aims to transform the PIF into a ‘global investment powerhouse’ by pledging to invest 25% of its assets in international portfolios, split between the International Diversified Pool and International Strategic Investment Pool (PIF, Citation2017a, p. 21). In contrast to the historically conservative approach to sovereign wealth management under SAMA, mainly built around US Treasury bonds, the critical juncture of 2015 induced a shift to a strategy increasingly oriented towards short-term goals. In addition to a centralization of foreign investment activities reflecting intra-elite dynamics and growing external pressures such as non-regulatory political risks, the PIF's speculative approach to the COVID-19 shock illustrates how shifts in elite politics are associated with a reposition of Saudi Arabia's strategy from buying bonds to buying the dip.

In the wake of the PIF's expansion from 2015, the fund gained the legal prerogative to invest outside Saudi Arabia, implying an overhaul of the Kingdom's financial management (Seznec & Mosis, Citation2018). The PIF's post-2015 expansion aggregated the Kingdom's foreign investment activity under a single umbrella as the SWF is now the sole foreign investor in the Kingdom (Roll, Citation2019). The concentration of sovereign wealth management under the PIF's umbrella, on the one hand, helps bypass SAMA’s largely autonomous technocratic body and, on the other, aggregates the fragmented investment vehicles under a single overarching fund overseen by a tightly knit group of high-level insiders close to MBS.

Recent cross-country analysis demonstrates that Saudi Arabia is a clear sender of sovereign investments with Qatar, Kuwait, Russia, China and Norway. The absolute majority of Saudi foreign investments (80.4%) are in majority stakes ownership (50.01% stakes) and indicate controlling interests (Babic et al., Citation2020). Moreover, the PIF's latest activities illustrate a preference for high-risk and high-profile ventures in technology and transport. Amongst PIF's high-profile investment decisions is a $45 billion investment in the SoftBank Vision Fund (45% of outstanding shares), the world's largest techno-focused venture capital fund. Furthermore, the PIF acquired 4.9% of Tesla in 2018 before selling its shares in 2020 to, in turn, inject $1.3 billion for majority ownership in Silicon Valley's Lucid Motors (Arab News, Citation2021; Li, Citation2020). The PIF also owns 5.3% of Uber Technologies for approximately $2.3 billion. The PIF created partnerships in entertainment, hospitality, and travel, such as a 500 million (5.73%) stake in the event promoter Live Nation Entertainment and 8.24% of the cruise operator Carnival Corporation for $369.3 million (C. Kelley, Citation2020; Reuters, Citation2020). The SWF also acquired a 2.32% stake in the Indian telecommunication giant Jio Platforms for $1.5 billion (Parkin & Raval, Citation2020).

Despite successes in establishing various international investment partnerships through the PIF, ‘there is a growing disconnect between the expectations of Saudi Arabia's government and the interests motivating the global investment community’ (Mogielnicki, Citation2019). The net inflows of foreign direct investments (FDI) have significantly declined from $39.5 billion in 2008 to a low of $1.4 billion in 2017, and then slightly rebounded to $4.6 billion in 20197. Roll underlines that ‘the decisive factor for the inflow of FDI is not the investment policy of the SWF, but rather the general investment climate in Saudi Arabia’ (Roll, Citation2019, p. 21). This points to growing non-regulatory political constraints facing PIF international activities stemming from the personalization of the SWF under the crown prince’s leadership (McPherson‐Smith, Citation2021). In response to the alleged involvement of the Saudi leadership, more specifically MBS, in the death of Jamal Khashoggi in October 2018, several PIF initiatives crumbled. For instance, several world business leaders withdrew from the 2018 Future Investment Initiative8 whereas Endeavor, one of the largest U.S. talent agencies, called off and returned a $400 million investment (K. Kelley & Hubbard, Citation2019; McPherson‐Smith, Citation2021). The Virgin Group cancelled a $1 billion investment and cut ties with the Kingdom citing MBS' involvement in the Khashoggi affair (Reuters, Citation2018).

On the other hand, The PIF’s investment strategy amid the economic downturn following the 2020 coronavirus outbreak further exemplifies the shift in strategy. The PIF reacted to the COVID-19 economic shock by opportunistically acquiring undervalued stocks in developed markets for immediate returns. The more authoritative and personalized role in sovereign wealth management adopted by the Saudi ruling elite is associated with a speculative and short-term oriented view of returns instead of a medium to long-term perspective underpinning the PIF’s stated goal of intergenerational wealth accumulation.

In the first quarter (Q1) of 2020, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) filings disclosed that the PIF assumed stakes in numerous US-listed companies (SEC, Citation2020a). In May 2020, at the outset of an economic downturn associated with the 2020 COVID-19 outbreak, PIF investments included stakes such as $713.7 million in Boeing, $522 million in Facebook, $521.9 million in Citigroup, $514 million in Marriott, $495.8 million in Disney, and $487.6 million in Bank of America. Furthermore, the PIF deployed significant investments in the energy sector, which could appear counterintuitive given the fund's goal of diversifying the Kingdom's economy (Bortolotti & Fotak, Citation2020). The Saudi SWF disclosed an $827.8 million stake in BP, $483.6 million in Royal Dutch Shell, $481 million in Suncor Energy, $408.1 million in Canadian Natural Resources, and $222.3 million in Total. In addition, the PIF acquired a $490.8 million stake in CISCO, $78.5 million in Pfizer, and a $78.4 million stake in Berkshire Hathaway (Azhar & Singh, Citation2020; Kamel, Citation2020; Kane, Citation2020; Mogielnicki, Citation2020; SEC, Citation2020a).

In the wake of these investments, PIF officials underlined intergenerational wealth as the key driver of the investment initiative: ‘PIF is a patient investor with a long-term horizon. As such, we actively seek strategic opportunities both in Saudi Arabia and globally that have strong potential to generate significant long-term returns while further benefitting the people of Saudi Arabia and driving the country's economic growth’ (Kamel, Citation2020)9. However, as markets rebounded in the second quarter (Q2), the PIF exited most of its ventures in US-listed firms assumed only three to four months prior. The fund’s total US-listed holdings dropped from 24 in Q1 to 12 in Q2. For instance, the Saudi SWF released its stakes in Boeing, Facebook, Marriott, Citigroup, Bank of America, BP, Royal Dutch, Total, IBM, QUALCOMM, Broadcom, and Pfizer. The PIF also sold a significant part of its shares in Berkshire Hathaway, CISCO, and Canadian Natural Resources Limited. In turn, the SWF considerably increased its positions in ADP, Suncor Energy, Carnival Corporation and Live National Entertainment (SEC, Citation2020b) (). The PIF's investment strategy during the economic contraction related to the 2020 coronavirus pandemic shock helped not to diversify the fund’s portfolio or position the SWF as a ‘patient investor with a long-term horizon’ and thus ‘further benefiting the people of Saudi Arabia’ but instead capitalized on the COVID-19 triggered sell-off to buy undervalued stocks for short-term tactical investments and expeditious returns.

Table 1. Variation in PIF US-Listed Holdings from Q1 to Q2 2020.

Other SWFs also saw in the COVID-19 downturn an opportunity to find attractive investment ventures. Aside from the PIF, the other Gulf SWF with a development mandate most active over the period was Abu Dhabi's Mubadala, which had invested more than $11 billion by December 2020 (Jones & Gottfried, Citation2020). Nonetheless, in contrast to other SWFs such as Mubadala, the PIF promptly existed most of its positions as the market rebounded. This pattern challenges SWF behavior during the pandemic and previous experiences of SWF investment in times of market volatility such as the 2007-08 financial crisis. Following the 2007-08 financial crisis, many large firms and banks sought equity investments by SWFs based on their long-term horizon and their disposition to provide patient capital (Deeg & Hardie, Citation2016). Gulf SWFs significantly contributed to the global bail-out by recapitalizing western financial institutions. For instance, Abu Dhabi's ADIA invested $7.5 billion in Citigroup, Kuwait's KIA injected $3 billion in Citigroup and $2 billion in Merril Lynch, and Qatar’s QIA invested $3.5 billion in Barclays (Pistor, Citation2009; Raymond, Citation2017; Saadi, Citation2009). Most notably, Gulf SWFs did not promptly disinvest following incurred losses and short-term volatility but held their positions at least until 2009 as the urgency of the global financial crisis was somewhat alleviated by government bail-out funds (Pistor, Citation2009).

While the 2007-08 global financial crisis and the coronavirus crisis are very different in character, both have produced extraordinary volatility in financial markets. Thereby, they provide a window to analyze SWFs' institutional discipline and the vulnerability of strategy, rules, and mandate to political influence. It underlines the distinctiveness of the PIF's strategy during the COVID-19 crisis not only in contrast to other SWFs over the same period but across previous instances of SWF behavior in times of market volatility. By doing so, it challenges the putative conceptualization of SWFs as an ideal type of patient capital providers, who maintain their investments even in the face of short-term volatility, given their mandate to generate returns through an extended timeframe and low pressure to generate short-term profits (Deeg & Hardie, Citation2016; Lerner & Ivashina, Citation2019; Thatcher & Vlandas, Citation2016).

Abundance in the age of scarcity: the PIF’s expansion and international factors

So far, the analysis accentuates how the PIF revamp is associated with shifts in regime structures and intra-elite politics characterized by a concentration of political and economic power within the circles of the Saudi ruling family since the rise of MBS. Can this turn in institutional design and investment initiatives be primarily explained by factors linked to regime structure? What about international factors? Authors like Aizenman and Glick (Citation2008), Das et al. (Citation2009) see sovereign development funds in commodity-exporting countries like the Saudi PIF as mainly driven by macroeconomic indicators. The focus is on sustained fiscal budget or current account surpluses following a resource boom in addition to challenges of economic diversification. While the PIF's expansion appears coherent considering Saudi Arabia's need for greater economic diversification10, a cursory look at macroeconomic trends illustrates how the SWF’s revamp took place in an age of scarcity characterized by falling oil prices, growing public debt, sustained budget deficits and increasing demographic pressures.

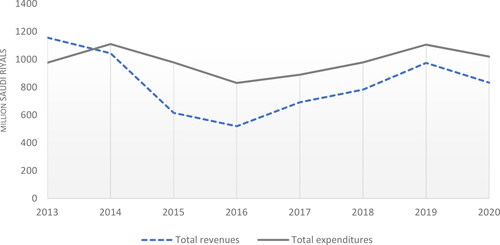

In 2014 the oil market turned and sent Brent prices tumbling from $98.97 in 2014 to $41.96 in 2020 (EIA, Citation2021). This drop in oil prices directly affected the Saudi oil-dependent state revenues, which declined twofold between 2013 and 2016 to reach 72% of their pre-oil shock level in 2020. In contrast to a sharp decline in revenues, government expenditures decreased much more slowly. As a result, the Saudi government has been experiencing sustained fiscal deficits since 2014 (). The public debt rose by 221% in 2015, 123% in 2016 and continued to grow between 40% and 21% until 2019 (Saudi Arabian Monetary Authority, Citation2017, Citation2020).

In addition, the last Saudi demographic survey (2016) exposes how of the 20.1 million Saudi nationals, 49% were under the age of 25, and 30% were under 15 years of age (Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Citation2016). In 2016 the total sum of Saudi nationals was more than eight times the size of any Gulf country (Gulf Research Center, Citation2016). Consequently, the available sovereign wealth per citizen in 2017 was $422 in Kuwait, $1,043 in Qatar and $1,085 in the UAE, while it stood at $42 per Saudi citizen (Gross & Ghafar, Citation2019). The dual prospects of a growing number of Saudis entering the labor market and a steady decline in resource revenues challenge the sustainability of the Saudi distributive state built mainly around large-scale public employment, social transfers, and heavily subsidized public utilities. For instance, in 2015, the government reported that salary and allowance expenditures alone exceeded total oil income (Hertog, Citation2018). Macroeconomic trends underscore the paradoxical disconnect between the Kingdom’s dire fiscal situation and the PIF’s significant expansion since 2015.

The Kingdom's deteriorating fiscal circumstances also directly affect the PIF funding source highly dependent on oil income. Sovereign development funds like the PIF often raise capital through bond issuance to support their investment program (Schena & Chaturvedi, Citation2011). Rather than issuing bonds considering shortfalls in resources revenues, the PIF shows an increasing appetite for private debt. The SWF opted to tap international banks to secure an $11 billion loan in 2018 and a $10 billion loan in 2019 (Abdellatif, Citation2019; Afanasieva, Citation2018). Then in March 2021, the PIF announced a $15 billion multicurrency revolving credit facility with 17 international banks (Saudi Press Agency, Citation2021c). Private loans allow the fund to avoid the scrutiny and various constraints associated with disclosure and issuing requirements of bonds but also illustrate a turn towards a more short-term approach to sovereign wealth management.

Another common assumption is that countries with geographical and cultural proximity, similar export profiles and exposed to similar external pressures will adopt similar SWF types and behaviour either through a process of cross-national emulation (e.g. Chwieroth Citation2014) or shared macroeconomic characteristics (Aizenman & Glick, Citation2008; Das et al., Citation2009; Lee, Citation2007). Consistent with this diffusion-based hypothesis (Chwieroth, Citation2014) Saudi Arabia, Bahrain and Abu Dhabi have indeed established SWFs with a development mandate when confronted with similar challenges, namely industrial upgrading or economic diversification. However, Abu Dhabi and Bahrain's sovereign development funds were launched in 2002 and 2006, coinciding with the oil boom of the early 2000s. Saudi Arabia became the last Gulf country to set up an SWF with a development mandate in 2015, a period counterintuitively characterized by a dramatic fall in state revenues and considerable fiscal deficits.

Moreover, one finds that Saudi Arabia's SWF varies more than in context of establishment but also in terms of strategic orientation, as previously demonstrated by the discrepancy between the PIF's speculative approach and Mubadala's more patient response to the COVID-19 shock. In addition, Mubadala carries the reputation of a reliable multi-year investor and the Gulf's most professional state investment vehicle; the fund was Global SWF’s Citation2021 fund of year and also takes part in the IFSWF’s self-assessment and transparency initiatives (Global SWF, Citation2022). Can factors linked to distinct regime dynamics explain this variation between the two Gulf SWFs? Despite sharing many similarities in terms of macroeconomic features, most notably dependence on oil revenues and exposure to external pressures like commodity cycles, the UAE has the most diversified economy in the GCC, and Abu Dhabi has most of the UAE’s oil wealth (Gross & Ghafar, Citation2019). Besides, the total sum of UAE nationals (including Abu Dhabi and other emirates) of 950 368 in 2016 contrasts the 20.1 million Saudi nationals (Gulf Research Center, Citation2016; Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Citation2016). As a high-rent country, the emirate is thus in a much stronger macroeconomic position than a low-rent Saudi Arabia. Therefore, under the assumption of SWFs as driven by macro-level indicators, Mubadala, rather than the PIF, emerges as the SWF in a better position to implement a more aggressive and riskier investment policy based on higher sovereign wealth per capita and a superior macroeconomic position.

At the socio-political level, Saudi Arabia and Abu Dhabi share similarities in concentration of authority, state autonomy, and power distribution in state-business relations. Like MBS, Muhammad bin Zayed Al-Nahyan (MBZ), crown prince and de facto ruler of Abu Dhabi and the UAE since 2004, side-lined previously influential officials or senior ruling elite members and concentrated power in the hands of trusted relatives or within a small circle of technocrats. For instance, Khaldun Al-Mubarak, known as MBZ's closest associate, is entrusted with various significant economic and political portfolios but is also the renowned managing director of Mubadala (Davidson, Citation2021). Much like the PIF and MBS, Mubadala is chaired by MBZ and was established to drive Abu Dhabi's diversification efforts towards technology-focused activities, mainly in aerospace, electronics and defense. While major institutions are under MBZ’s grasp or his inner circle, the crown prince also consolidated his authority over the business elite mainly through anti-corruption campaigns. In addition, institutions of business representation enjoy a low degree of autonomy and limited political strength (Braunstein, Citation2019; Davidson, Citation2021). The design and working logic underpinning SWFs is a multi-faceted and complex issue. Nonetheless, against a backdrop of counterintuitive macroeconomic trends and in contrast with an SWF embedded in comparable socio-political dynamics, the PIF’s revamp and shift towards a more aggressive and wide-ranging investment strategy appears as fundamentally driven by distinct regime dynamics following the 2015 regime change.

Conclusion

Beyond the logic of SWFs as outcomes of macro-level trends, the political dimension underlying the PIF's reconfiguration is crucial to understanding SWF development in Saudi Arabia. More specifically, the article demonstrates how the concentration of royal authority and power politics within the family following the accession of King Salman and the rise of MBS drove the shift in the PIF's post-2015 institutional design and investment initiatives. The outcome was a shift from scattered and uncoordinated investment patterns associated with interagency feuds and the influence of competing senior decision-makers to a personalized and highly interventionist strategy driven by a tightly knit group of regime insiders evolving around the crown prince.

The connection between PIF choices, elite politics, and reshuffle at the top-level of the Saudi state apparatus following the rise of MBS illustrate that despite theoretical efforts to depoliticize SWF design and use, the personal ambition of political agents and their political network carry weight in choices relating to sovereign wealth management. In line with patterns in the Kingdom’s state formation since the 1950s (Hertog, Citation2010b; Yizraeli, Citation1998), institutional initiatives are often tokens of authority in an intra-elite power game as much as attempts at modernizing or reforming the state. The PIF is yet another reminder of how competing interests and coalitions between senior royals and technocrats can shape the trajectory of the Saudi state at historical junctures.

These findings have implications for research on drivers of sovereign investments in IPE more broadly. While Thatcher and Vlandas (Citation2016) underline the growing role of SWFs as allocators of long term capital, Lerner and Ivashina (Citation2019) point to SWFs as pools of much-needed patient capital in the face of pressing issues such as climate change, global health and decaying infrastructure. Nonetheless, the present analysis underlines that this portrait of SWFs as pure cases of risk-averse and long-term capital providers regardless of mandates and political contexts is painted with too broad of a brush. Instead, the findings illustrate how investment patterns may be driven by the ambition to bolster national champions or further political and strategic goals, either through acquiring controlling stakes in targeted companies or even speculative and short-term oriented blitz on markets. Faced with a shift in the political balance of power, the Saudi leadership consciously and conspicuously deployed the SWF locally and globally to legitimize and sustain existing structures of political authority rather than merely seeking profit-maximization through a long-term horizon. Decisions regarding SWFs are not fixed in an apolitical vacuum but are instead enmeshed in specific social, economic and political contexts.

This analysis touches upon crucial theoretical and empirical issues in IPE. The growth of SWFs and their increasingly heterogenous and aggressive market positions, either domestically or across the global financial market as exemplified by the PIF, stresses how restrictive a clear state-versus-market dichotomy is. The process of state financialization and SWFs reassert state authority and thus signal that states participate in global finance beyond a mere regulative role (Babic et al., Citation2020; Helleiner & Lundblad, Citation2008; Schwan et al., Citation2021). In this sense, including political agency and relational structure underlying the rise of SWFs as key market actors in our analysis can accentuate the political and strategic objectives of state investment funds, whether it be at home or over the global financial markets. The quantitative SWF analyses can be complemented by closer, qualitative and case-oriented research in order to heighten the political dimension behind the broader expansion of transnational state capital. With numerous established or planned funds in countries as diverse as Turkey, Cape Verde, Switzerland or Uruguay, recognizing the interplay of domestic politics and sovereign wealth management is crucial to address the opportunities and challenges underlying the governments' leverage of state finance institutions. The fast-growing interest in SWFs in a wide array of socio-political contexts calls attention to the need for scholars and practitioners to further engage with the frontiers of SWFs’ design and use.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Ewan Stein, Charlotte Rommerskirchen, Lucy Abbott and the anonymous referees for helpful and insightful comments on earlier versions of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Alexis Montambault Trudelle

Alexis Montambault Trudelle is a doctoral candidate in Politics and International Relations at the University of Edinburgh.

Notes

1 SAMA does not provide any currency breakdown of foreign exchange reserves. Nevertheless, in 2008, SAMA was believed to hold 85% of its foreign exchange reserve in US$(Bazoobandi, Citation2013).

2 Smith Diwan (Citation2009) judged that 50 to 60 government agencies were involved in foreign investment activities.

3 Data on the Saudi bank sector's market share as of Q1-2020 (Aljazira Capital, Citation2020b).

4 Data on shareholders from Tadawul as of January 2022.

5 Data from Tadawul as of January 2022.

6 Data on directors and shareholders from Tadawul, Capital IQ, publicly available data from LinkedIn and Hanieh’s (Citation2018) extensive work on Gulf conglomerates.

7 FDI net inflows data from the World Bank as of January 15, 2021, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.KLT.DINV.CD.WD?end=2019&locations=SA&start=2008&view=chart

8 The global CEOs and finance officials who dubbed the event include Stephen Schwarzman (CEO of Blackstone), Christine Lagarde (then director of the IMF), Jamie Dimon (CEO of JPMorgan Chase), AOL’s founder Steve Case, Siemens CEO Joe Kaeser, Blackrock and Uber CEOs Larry Fink and Dara Khosrowshahi, Virgin CEO Richard Branson, and Bill Ford of Ford Motor (Alkhalisi, Citation2018; BBC, Citation2018; Stanley-Becker, Citation2018).

9 Statement from email communications between PIF officials and Abu Dhabi’s daily, The National News (Kamel, Citation2020).

10 From 2000 to 2019, oil income averaged 81,4% of total state revenues (SAMA annual reports).

References

- Abdellatif, R. (2019, September 28). Saudi Arabia’s PIF finalizes terms for $10 billion loan. Al Arabiya. https://english.alarabiya.net/business/economy/2019/08/28/Saudi-Arabia-s-PIF-finalizes-terms-for-10-billion-loan

- Power, A. C. W. A. (2021, April 8). Public Investment Fund (PIF) reaches major milestone in landmark solar PV project. ACWA Power. https://www.acwapower.com/news/public-investment-fund-pif-reaches-major-milestone-in-landmark-solar-pv-project/

- Afanasieva, D. (2018, September 24). Saudi sovereign fund PIF raises $11 billion loan. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-saudi-aramco-ipo-loan/saudi-sovereign-fund-pif-raises-11-billion-loan-source-idUSKCN1L90WK

- Aizenman, J., & Glick, R. (2008). Sovereign wealth funds: Stylized facts about their determinants and governance (NBER Working Paper WP/14562; p. 57). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Arabiya, A. (2020, January 30). NEOM set up as joint stock company owned by Saudi state fund PIF. Al Arabiya. https://english.alarabiya.net/en/business/economy/2019/01/30/NEOM-set-up-as-joint-stock-company-run-by-Saudi-state-fund-PIF

- Jazeera, A. (2019, October 23). Saudi king names Faisal bin Farhan Al Saud foreign minister. Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/10/23/saudi-king-names-faisal-bin-farhan-al-saud-foreign-minister

- Al-Hassan, A., Papaioannou, M., Skancke, M., & Sung, C. C. (2013). Sovereign wealth funds: Aspects of governance structures and investment management. IMF Working Papers, 13(231), 1. https://doi.org/10.5089/9781475518610.001

- Aljazira Capital. (2020a). Monthly report: Saudi cement sector (p. 4) (Monthly Rep.). Aljazira Capital. https://argaamplus.s3.amazonaws.com/94fb8c01-8e91-4047-a95d-0a16774bdc27.pdf

- Aljazira Capital. (2020b). Quarterly report: Saudi banking sector (p. 8) (Quaterly Rep.). Aljazira Capital. https://argaamplus.s3.amazonaws.com/502ae17b-0219-4504-ac0a-32405aeae76c.pdf

- Alkhalisi, Z. (2018, October 22). Saudi Arabia tries to salvage its investment conference after A-listers pull out. CNN Business. https://www.cnn.com/2018/10/21/business/saudi-investment-conference/index.html

- Al-Rasheed, M. (2005). Circles of power: Royals and society in Saudi Arabia. In P. Aarts & G. Nonneman (Eds.), Saudi Arabia in the balance: Political economy, society, foreign affairs (pp. 185–2013). Hurst & Company.

- Al-Rasheed, M. (2018). Mystique of monarchy: The magic of royal succession in Saudi Arabia. In M. Al-Rasheed (Ed.), Salman’s legacy: The dilemmas of a new era in Saudi Arabia (pp. 45–71) Oxford University Press.

- Al-Rasheed, M. (2021). The son king: Reform and repression in Saudi Arabia. Oxford University Press.

- Alsweilem, K. A., Cummine, A., Rietveld, M., & Tweedie, K. (2015). A comparative study of sovereign investor models: 142.

- News, A. (2018). May 21). Qiddiya Investment Company officially established as standalone company. Arab News. https://www.arabnews.com/node/1306771/saudi-arabia

- Arab News. (2021, February 24). PIF makes billions on its investment in Lucid Motors. Arab News. https://www.arabnews.com/node/1815241/business-economy

- Argaam. (2018, June 14). Saudi PIF chief joins board of SoftBank’s Arm Holdings. Argaam. https://www.argaam.com/en/article/articledetail/id/554353

- Argaam (2020, December 17). Saudi PIF eyes opportunities with focus on medium, long-term investments: Governor. Argaam. https://www.argaam.com/en/article/articledetail/id/1429311

- Azhar, S. (2020, December 17). RPT-Saudi sovereign fund PIF says total staff count crossed 1,000 in Dec. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/saudi-pif-hires-idUSL1N2IX09D

- Azhar, S., & Kalin, S. (2019, June 28). Saudi Arabia’s hometown ambitions could clip wealth fund’s wing. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-saudi-pif-investment-insight-idUSKCN1TT0OE

- Azhar, S., & Singh, K. (2020, May 16). Saudi wealth fund boosts U.S. holdings with stakes in Citi, Boeing, Facebook. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-saudi-pif/saudi-wealth-fund-boosts-u-s-holdings-with-stakes-in-citi-boeing-facebook-idUSKBN22S0BQ

- Babic, M., Garcia-Bernardo, J., & Heemskerk, E. M. (2020). The rise of transnational state capital: State-led foreign investment in the 21st century. Review of International Political Economy, 27(3), 433–475. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2019.1665084

- Banafe, A., & Macleod, R. (2017). The Saudi Arabian monetary agency, 1952–2016. Central Bank of Oil. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bazoobandi, S. (2013). Kuwait’s Sovereign Wealth Fund. In The political economy of the Gulf sovereign wealth funds: A case study of Iran, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (pp. 33–55). Routledge.

- BBC. (2018, October 23). Saudi summit begins amid boycott. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/business-45944854

- Bortolotti, B., & Fotak, V. (2020). Sovereign wealth funds and the COVID-19 shock: Economic and financial resilience in resource-rich countries. BAFFI CAREFIN Centre Research Paper, 2020–147, 29.

- BrandFinance (2021, February). Chemicals 25 2021: The annual report on the most valuable and strongest chemicals brands. BrandDirectory. https://brandirectory.com/rankings/chemicals

- Braunstein, J. (2017). The domestic drivers of state finance institutions: Evidence from sovereign wealth funds. Review of International Political Economy, 24(6), 980–1003. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2017.1382383

- Braunstein, J. (2019). Domestic sources of twenty-first-century geopolitics: Domestic politics and sovereign wealth funds in GCC economies. New Political Economy, 24(2), 197–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2018.1431619

- Carney, R. W. (2018). Authoritarian capitalism: Sovereign wealth funds and state-owned enterprises in East Asia and beyond (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108186797

- Chwieroth, J. M. (2014). Fashions and fads in finance: The political foundations of sovereign wealth fund creation. International Studies Quarterly, 58(4), 752–763. https://doi.org/10.1111/isqu.12140

- Clark, G. L., & Monk, A. (2012). Modernity, imitation, and performance: Sovereign funds in the Gulf. Business and Politics, 14(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1515/1469-3569.1417

- Collier, R. B., & Collier, D. (1991). Shaping the political arena: Critical junctures, the labor movement, and regime dynamics in Latin America. Princeton University Press.

- Das, U. S., Lu, Y., & Sy, A. (2009). Setting up a sovereign wealth fund: Some policy and operational considerations (IMF Working Paper WP/09/179; p. 22). International Monetary Fund. https://doi.org/10.5089/9781451873269.001

- Davidson, C. (2021). From Sheikhs to Sultanism: Statecraft and authority in Saudi Arabia and the UAE. Hurst & Company.

- Deeg, R., & Hardie, I. (2016). What is patient capital and who supplies it? Socio-Economic Review, 14(4), 627–645. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mww025

- Dixon, A. D. (2022). The strategic logics of state investment funds in Asia: Beyond financialisation. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 52(1), 127–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2020.1841267

- EIA. (2021, February 18). Europe Brent Spot Price FOB. U.S Energy Information Administration. https://www.eia.gov/dnav/pet/hist/rbrteM.htm

- England, A., & Massoudi, A. (2020, May 25). Never waste a crisis’: Inside Saudi Arabia’s shopping spree. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/af2deefd-2234-4e54-a08a-8dbb205f5378

- Global SWF. (2022, January 1). Fund of the Year (2022): Mubadala. Global SWF. https://globalswf.com/news/fund-of-the-year-jan-22-mubadala

- Grigoryan, A. (2016). The ruling bargain: Sovereign wealth funds in elite-dominated societies. Economics of Governance, 17(2), 165–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10101-015-0168-7

- Gross, S., & Ghafar, A. A. (2019). The shifting energy landscape and the Gulf economies’ diversification challenge. The New Geopolitics, Middle East 25.

- Gulf Research Center (2016, April 20). GCC: Total population and percentage of nationals and foreign nationals in GCC countries (national statistics, 2010–2016). Gulf Research Center. https://gulfmigration.org/gcc-total-population-percentage-nationals-foreign-nationals-gcc-countries-national-statistics-2010-2016-numbers/

- Hanieh, A. (2018). Money, markets, and monarchies: The Gulf cooperation council and the political economy of the contemporary Middle East (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108614443

- Hatton, K. J., & Pistor, K. (2011). Maximizing autonomy in the shadow of great powers: The political economy of sovereign wealth funds. SSRN Electronic Journal, 50(1), 1–82. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1787565

- Helleiner, E. (2009). The geopolitics of sovereign wealth funds: An introduction. Geopolitics, 14(2), 300–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650040902827740

- Helleiner, E., & Lundblad, T. (2008). States, markets, and sovereign wealth funds. German Policy Studies, 4(3), 59–82.

- Herb, M. (1999). All in the family: Absolutism, revolution, and democracy in Middle Eastern monarchies. SUNY Press.

- Hertog, S. (2006). Modernizing without democratizing? The introduction of formal politics in Saudi Arabia. Internationale Politik Und Gesellschaft, 3, 65–78.

- Hertog, S. (2008). Petromin: The slow death of statist oil development in Saudi Arabia. Business History, 50(5), 645–667. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076790802246087

- Hertog, S. (2010a). Defying the resource curse: Explaining successful state-owned enterprises in rentier states. World Politics, 62(2), 261–301. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0043887110000055

- Hertog, S. (2010b). Princes, brokers, and bureaucrats: Oil and the state in Saudi Arabia. Cornell University Press.

- Hertog, S. (2018). Challenges to the Saudi distributional state in the age of austerity. In M. Al-Rasheed (Ed.), Salman’s legacy: The legacy of a new era in Saudi Arabia (pp. 73–96) Oxford University Press.

- Hope, B., & Scheck, J. (2020). Blood and oil: Mohammed bin Salman’s ruthless quest for global power. Hachette Books.

- Hubbard, B. (2020). MBS: The rise to power of Mohammed bin Salman (1st ed.). Tim Duggan Books.

- Jones, R. (2018, December 31). Expats flee Saudi Fund, Bemoan Crown Prince control. Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/expats-flee-saudi-fund-bemoan-crown-prince-control-11546257600

- Jones, R., & Gottfried, M. (2020, December 5). Abu Dhabi’s $230 billion man bet the world would overcome Covid-19. Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/abu-dhabis-230-billion-man-bet-the-world-would-overcome-covid-19-11607144409

- Kamel, D. (2020, May 16). Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund invests billions of dollars in Boeing, Disney, and Facebook shares. The National News. https://www.thenationalnews.com/business/saudi-arabia-s-public-investment-fund-invests-billions-of-dollars-in-boeing-disney-and-facebook-shares-1.1020204

- Kane, F. (2020). May 17). Saudi Arabia buys $7.7 billion shares in world’s best known companies. Arab News. https://www.arabnews.com/node/1675796/business-economy

- Kelley, C. (2020, April 29). Saudi Arabia’s public investment fund buys $500 million stake in live nation. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/caitlinkelley/2020/04/29/saudi-arabias-public-investment-fund-buys-500-million-stake-in-live-nation/?sh=31940ffa1daf

- Kelley, K., & Hubbard, B. (2019, March 8). Endeavor returns money to Saudi Arabia, prostesting Khashoggi murder. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/08/business/endeavor-saudi-arabia.html

- Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. (2016). Demography survey (p. 208). General Authority for Statistics. https://www.stats.gov.sa/sites/default/files/en-demographic-research-2016_4.pdf

- Kraetzschmar, H. J. (2015). Associational life under authoritarianism: The Saudi chamber of commerce and industry elections. Journal of Arabian Studies, 5(2), 184–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/21534764.2015.1129723

- Lee, B. (2007). Robust portfolio construction in a sovereign wealth context. In J. Johnson-Calari & M. Rietveld (Eds.), Sovereign wealth management (pp. 157–178). Central Banking Publications.

- Lerner, J., & Ivashina, V. (2019). Patient capital: The challenges and promises of long-term investing. Princeton University Press.

- Li, Y. (2020, February 4). Saudi Arabia fund dumped nearly all of its Tesla shares in the fourth quarter before the rally. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2020/02/04/saudi-arabia-fund-dumped-nearly-all-of-its-tesla-shares-in-the-fourth-quarter-filing-shows.html

- Ma’aden. (2020). About story. https://www.maaden.com.sa/en/about/history