Abstract

Sustainability standards verify that goods and services meet minimum social and environmental norms. They have rapidly gained traction in value chains that connect lead firms with dispersed global suppliers. Historically, such standards have been created by firms, civil society and state regulators in the global North to govern global value chains sourcing goods and services from Southern producers. However, this century has witnessed the emergence of Southern-led sustainability standards. While a few studies have investigated this development, little is yet known about how Southern standards are shaped by public and private actors, or how domestic as well as global value chain dynamics impact their development. We address these gaps through a comparative study of Chinese clothing and Indian tea standards. Drawing upon the concepts of synergistic and antagonistic forms of governance, this article analyses how, when and why Southern actors (public, private and social) choose to develop new sustainability programmes which either emulate or else disrupt established transnational standards within this governance arena. Recognising the agency of Southern actors, but also their constraints to act within this established field, we examine how the sector-specific political economy dynamics of apparel and tea production shape the mechanisms, processes and relations through which Southern sustainability standards are forged in this increasingly multi-polar world of trade and production.

Introduction

Sustainability standards have become significant governance institutions within global value chains (Ponte & Gibbon, Citation2005; Nadvi, Citation2008). While questions remain regarding the efficacy of such standards, they often represent a critical lever to govern highly complex and geographically disparate production relationships between lead firms and their local suppliers. Sustainability standards transmit complex information along such value chains to producers at local sites of production as well as to consumers in global end-markets. Initially considered a neoliberal form of governance within which private actors (such as corporations and NGOs) cooperate through multi-stakeholder initiatives (MSIs) (O’Rourke, Citation2006), there is now an extensive debate on the ways through which public as well as private actors interact in the shaping and implementation of such standards (Locke et al., Citation2013; Nadvi & Raj-Reichert, Citation2015; Bartley, Citation2018) and how this differs within contrasting political economic contexts.

A majority of sustainability standards govern global value chains (GVCs) where goods and services produced in the global South are consumed in the global North. However, since the turn of the century, the geographies of global trade flows and consumption have shifted, with emerging economies now accounting for an ever-growing proportion of global imports (Staritz et al., Citation2011; Guarín & Knorringa, Citation2014; Horner & Nadvi, Citation2018). While some scholars argue that developing country markets either lack the capacity and/or interest to develop similar standards (Kaplinsky & Farooki, Citation2011), recent studies point to a diverse range of global standards being applied within Southern end markets (Schleifer & Sun, Citation2018) as well as the emergence of Southern-led sustainability standards governing domestic and regional value chains across numerous sectors (Hospes, Citation2014; Schouten & Bitzer, Citation2015; Langford, Citation2019). The nascent literature on ‘Southern standards’ suggests that they are often driven by local actors who have created alternatives to the dominant standards set by lead firms and NGOs governing sustainability challenges within GVCs. Yet, this characterisation overlooks the relational aspect to their development, through which complex intersections between powerful commercial actors and local standard-setters may likely influence the extent to which Southern standards deviate from, or conversely imitate pre-established sustainability standards. This is an important gap given the rapid expansion of Southern end markets under twenty-first century patterns and structures of globalised production and trade.

This article addresses this gap. It examines the key actors and processes shaping the development of new Southern-led sustainability standards in Chinese apparel and Indian tea, and how these standards intersect with the pre-existing governance arrangements of GVCs led by private actors in the global North. China and India are the dominant producers and leading exporters within the two sectors of focus: apparel and tea. As major exporters into global markets, Chinese and Indian producers in these two sectors are already governed by numerous sustainability standards. Yet as leading emerging economies, China and India have actively sought to emphasise their sovereignty and challenge the dominant ‘rule-setting’ agenda in relation to the governance of global trade (Narlikar, Citation2013). The introduction of China Social Compliance 9000 for Textile and Apparel Industry (CSC9000T) as a Chinese-led sustainability standard in apparel in 2005 and the Trustea standard as an Indian-led sustainability standard for tea in 2013 represent a fitting comparative case study to examine how public and private actors in emerging economies shape Southern sustainability standards, the extent to which these standards challenge, or conform to, existing types of sustainability governance within the respective value chains, and how intersections between the agency of standard-makers and the structural power of lead firms ultimately affects the uptake of Southern sustainability standards.

We draw on the emergent literature on the role of public actors in shaping GVCs (Mayer & Phillips, Citation2017; Alford & Phillips, Citation2018), alongside recent conceptualisations of multi-scalar governance within GVCs (Gereffi & Lee, Citation2016; Alford, Citation2020) to analyse the development of Southern sustainability standards through the concepts of ‘synergistic’ and ‘antagonistic’ governance. Using this framework, we demonstrate how states and other governance actors seek to shape Southern sustainability standards in relation to pre-existing standards led by corporate actors within the GVC. We pose two distinct, but inter-related, research questions: First, how do public and private actors interact in the development of Southern standards. Second, how do wider commercial dynamics shape the uptake of such standards?

We define ‘Southern standards’ as voluntary standards that are formulated within the global South, in other words within developing countries. They can seek to regulate production for, and consumption within, domestic markets in the global South, in other developing country markets or even in markets situated within developed economies (i.e. the global North). A range of different actors can be engaged in their formulation and implementation. This includes private actors; such as firms, business associations, and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) as well as public actors; from state ministries to specialised government agencies and national standard-setting bodies. In some contexts, the distinction between public and private may blur: lead firms could be state-owned enterprises, while apex business associations and standard setting agencies could be public, semi-public or private organisations. These voluntary standards, as in the global North, are distinguished from national regulations to enforce minimum norms on sustainability concerns around environmental impacts and/or labor and working conditions. What is distinctive about ‘Southern standards’ is that they are framed in the global South and thus expected to better incorporate the interests and values of developing country actors than global (or ‘Northern’) standards have tended to do.

While some studies on Southern-led sustainability standards highlight their differences in relation to pre-established standards in relation to legitimation and form (Schouten & Bitzer, Citation2015; Langford & Fransen, Citation2022), the ways through which these standards develop over time and in relation to value chain dynamics is often overlooked (for exception see Alford et al., Citation2021). This article examines the development of two new Southern-led sustainability standards through a relational approach, seeking to understand the degree to which processes of standard formation in the South are influenced by commercial pressures within value chains.

The article makes two key contributions to the literature: Firstly, by situating the development of standards within the established ‘transnational field’ of buyer-driven value chains (focused on apparel and tea), we highlight the direct and indirect role that powerful (and often global) lead firms play in shaping the form and structure of Southern standards. Our cases illustrate that lead firms continue to play a critical legitimating role within the uptake of Southern standards and therefore play a decisive role in how widely they are adopted. This suggests that value chain dynamics remain critical to the study of new standards and how they are established. Secondly, we highlight that, in spite of the important role played by lead firms and established GVC-oriented sustainability standards, local political relations between public and private actors do continue to affect the degree to which new sustainability standards mimic established norms as set in the global North, even at the risk of a wider failure of uptake. Ultimately, the degree and extent to which Southern actors engage in synergistic versus antagonistic practices can be seen as an outcome of these two competing tensions (between the structural constraints of value chains and the agency of Southern actors). These, in turn, are shaped by the entangled, complex and ever-changing nature of public-private intersections at the transnational and local levels within specific sector and country contexts.

Overall, the cases highlight the significance of structural power within value chains and how this in turn shapes the agency of Southern actors in creating new sustainability standards in the South. Our findings emphasise the need for a more careful, multi-scalar consideration of how the agency of public and private actors shaping standards intersects with powerful lead firms, and with what consequences for the development of new sustainability standards.

The article is structured as follows: The following section conceptualises the emergence of sustainability standards, examining the shifting roles played by firms, states and civil society organisations in the development of sustainability standards during the late 20th and early 21st century. Section 3 provides an overview of our methodology and case selection. Section 4 discusses the changing commercial and institutional environments within China and India during the period within which CSC9000T and Trustea were created. Sections 5 and 6 examine the extent to which local and/or global dynamics have shaped the development of the two standards, and how political and institutional variation have intersected with broader value chain and trade dynamics to produce differentiated outcomes for the two standards. Section 7 concludes by drawing out the comparative findings.

Conceptualising Southern-led standards through a GVC lens

The ascendancy of private governance in the North: lead firms as ‘global governors’

Sustainability standards developed by corporations and NGOs are emblematic of the shifting role and responsibilities of public and private actors within the regulation of cross-border trade and production (Nadvi & Wältring, Citation2004). The proliferation of these standards can be understood through the cognate global value chain (GVC) and global production network (GPN) approaches which conceptualise the role of lead firms, states and civil society actors in governing globalised supply chains (Gereffi et al., Citation2005; Henderson et al., Citation2002). Whilst these approaches have typically looked at the governance of exports to global markets, there is a growing literature examining the governance of domestic and regional value chains (DVCs/RVCs) (Horner & Nadvi, Citation2018; Langford, Citation2021).

During the 1990s, mounting evidence of severe labor exploitation and environmental degradation within supply chains led civil society actors to pressure corporations to protect social and environmental aspects of production in developing countries (Cashore et al., Citation2004; Seidman, Citation2007). Concerns over reputation incentivised corporate responses, especially as multinational firms increased their power and influence within the global economy. Initially, these firms developed standards through firm-specific codes of conduct but the lack of transparency within these standards led to the growth of multi stakeholder initiatives (MSIs) wherein corporate actors collaborated with NGOs to co-create standards. This development underlined the growing influence of a range of private actors as regulatory players within the global economy (Nadvi, Citation2008; De Bakker et al., Citation2019) and the rise of multi-stakeholder governance became associated with the weakening of state power whereby markets became global whilst regulatory institutions remained national (Mayer & Gereffi, Citation2010).

While earlier accounts tended to emphasise the significance of private actors, recent scholarship within the GVC and GPN literature has underlined and categorised the complex and multifaceted role of nation-states within ‘the construction and maintenance of a GVC world’ (Mayer & Phillips, Citation2017, p. 134; Horner, Citation2017; Alford & Phillips, Citation2018). States provide a facilitative role by assisting firms within GVCs through trade and competition rules, standard-setting and industrial policies (Mayer & Phillips, Citation2017). Additionally, states provide a regulatory role through measures that ‘limit and restrict the activities of firms’ within GVCs in relation to labor and environmental norms through legal frameworks and public regulations (Horner, Citation2017, p. 7). Of course, states may also seek to deregulate, and may facilitate a move towards private (re)regulation (Mayer & Phillips, Citation2017).

Seen from this political economy perspective, the rise of private governance under neoliberalism is not a simple transfer of power from states to corporations, but instead represents a process whereby states have actively facilitated a transition towards privatisation and the re-regulation of labor and the environment by supporting the development of private standards (LeBaron & Phillips, Citation2019). Further studies illustrate how public actors provided both financial and discursive support for the development of standards, as well as setting the legal regulatory norms that private standards should meet (Fransen, Citation2013; Mayer & Phillips, Citation2017). Overall, the expansion of private governance does not imply a decline in public power, but rather reflects the ways through which states have actively reshaped roles and responsibilities for governing in an age of neoliberalism via a process of outsourcing governance (Mayer & Phillips, Citation2017).

Considerations of how ‘private-public’ interactions produce outcomes through the layering of rules and norms has become a significant area of research, with the concept of ‘hybrid’ governance being used to explore these relationships (Bair, Citation2017). Some studies have highlighted the benefits of hybridity: demonstrating that state regulations within export-oriented sectors are most effective when they intersect with private forms of governance (Locke et al., Citation2013; Amengual & Chirot, Citation2016). Others highlight the delegation of regulatory roles within hybrid governance, in which the layering of public and private standards creates a situation whereby state bodies are ‘critical in determining the content of labour standards’ but ‘enforcement…[is] effectively outsourced to private agencies’ along the value chain (Alford & Phillips, Citation2018, p. 106).

The notion of ‘layering’ between public and private is key to both the framing of standards and their effective implementation, especially where the state is weak in enforcing standards. Therefore, the multi-actor (firms, states and NGOs) and multi-scalar (global, national, local) dimensions of social and environmental governance in global production is crucial to any analysis of standard-setting within value chains. depicts this through a typology that recognises territorial, institutional and organisational distinctions between various governance actors, thus facilitating the analytical demarcation of actors and interests based on their position within GVCs.

Table 1. Multi-scalar governance actors.

The recent focus on the multi-scalar dimensions of public-private interactions has led to the notion of ‘synergistic governance’ (Gereffi & Lee, Citation2016) in which a combination of different governance initiatives led by firms, states and civil society actors (representing private, public and social governance) may strengthen the overall effectiveness of regulation. Synergistic governance builds on the idea of complementarities (Locke et al., Citation2013) to offer ‘a promising pathway to bring together corporate, governmental and civil society actors in a global setting to achieve joint objectives, where active collaboration among GVC and [local] actors is required…to simultaneously achieve economic and social gains’ (Gereffi & Lee, Citation2016, p. 35).

While this concept is helpful in mapping the complex array of actors involved in governing production and the potential synergies which may emerge, this cooperative framework does little to address the underlying power structures which mediate relations between different Northern and Southern governance actors within GVCs. Bair (Citation2017) argues that the overarching focus on complementarities masks the degree and nature of complex intersections between transnational standards and domestic laws and regulations; wherein the local political context is shaped by the ‘transnational field’ within which it is embedded (Bair, Citation2017, p. 182). In turn, the transnational field is inevitably shaped by local political contexts. This relational approach is important for the study of Southern standards which are presumably shaped by the ‘relations of force’ between different governance actors seeking to regulate specific nodes of production (Levy, Citation2008; Bair & Palpacuer, Citation2015). This raises the possibility of ‘antagonistic governance’ which describes the dynamic processes of contestation and compromise that exist ‘within and across private, public and civil society governance, and that serve to forge, challenge and transform hegemonic stability in GVCs’ (Alford, Citation2020, p. 43).

This article operationalises the concepts of synergistic versus antagonistic governance to analyse how, when and why Southern actors choose to create sustainability standards which imitate or mimic pre-established standards and/or challenge and disrupt established sustainability standards. Recognising the agency of Southern actors, but also their complex relations within the established ‘transnational field’ of the value chain, we examine how the sector-specific dynamics of apparel and tea production shape the mechanisms, processes and relations through which Southern sustainability standards are forged.

Southern standards: initial findings

Southern-led sustainability standards are a recent phenomenon in global governance. While Southern actors have long engaged with sustainability standards, they did so generally as standard-takers rather than standard-makers. Yet since 2010, Southern-led sustainability standards have developed in various sectors including tea, soya, timber and apparel (Schouten & Bitzer, Citation2015). The emergence of Southern standards in traditionally export-oriented sectors, such as the Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO) standard, the Brazilian soya standard SojaPlus, and the Indian tea standard Trustea, must be analysed in relation to the wider value chain dynamics that shape those sectors because historical and ongoing interactions are critical to understanding the context for their emergence. Initial studies suggest Southern standards can be led by public and/or private actors and are sometimes interpreted as an outcome of state-led attempts to reassert sovereignty when it comes to the governance of sustainability challenges (Giessen et al., Citation2016). The case of Chinese timber illustrates that state actors created an alternative domestic certification programme to reduce the regulatory ‘space’ for Northern forestry standards (Bartley, Citation2014, p. 103). In the case of Indonesian palm oil, state actors challenged private and transnational certification institutions ‘in support of government-driven international certification regimes’ (Giessen et al., Citation2016, p. 71). Such cases are reflective of antagonistic governance; in which local actors have responded to GVC-based forms of governance through the creation of different standards which better meet their interests.

Yet despite these studies’ focus on these global-local dynamics, they tend to overlook the specific forms of interactions which inevitably occur between lead firms (and their established standards) and the newly emergent Southern sustainability standards. By neglecting this relational aspect, they overlook the possible ways through which value chain structures influence the development of Southern standards as partially, if not sometimes largely, synergistic forms of governance. Southern standards do not emerge within a vacuum, but of course are influenced by the pre-existing ‘transnational field’ (Bair, Citation2017, p. 171). Moreover, Southern standards are not always developed by public actors, but may be instigated by private actors in response to a lack of domestic state regulation and/or enforcement (Alford et al., Citation2021). Therefore, more evidence is needed on how Southern standards use aspects of imitation as well as deviation to develop new sustainability programmes, and how and why these patterns of synergistic and antagonistic governance emerge within specific sectors.

We argue that the current literature on Southern standards could be strengthened through more careful consideration of the sector-specific dynamics of value chains and specifically on how lead firms influence the development of Southern standards through a relational approach. A consideration of the complex intersections between the ‘transnational field’ of the value chain and those actors seeking to create new sustainability standards may lead to a more comprehensive understanding of how and why synergistic and/or antagonistic examples of governance are emerging in the global South.

Synergistic and antagonistic governance within Southern standards

This article applies the GVC framework to the study of Southern sustainability standards. Drawing on recognition of state roles in regulating value chains, we use the concept of synergistic and antagonistic governance (Gereffi & Lee, Citation2016; Alford, Citation2020) to explore the relational dynamics shaping the creation and implementation of CSC9000T for the Chinese apparel industry and Trustea for the Indian tea industry. By placing the empirical study of Southern sustainability standards within this framework, we analyse their development according to both the political factors shaping local interest in sustainability governance as well as the economic imperatives that mould governance within production chains. We explore whether actors’ decisions to engage in synergistic (mimicking, imitating, aligning) versus antagonistic (challenging, deviating, disrupting) governance practices are linked to the specific commercial dynamics of value chains and the underlying power relations between public, private and social governance actors within different sectors and country-contexts.

At present, evidence on why actors in the South are developing voluntary sustainability standards is limited to a few studies (Langford, Citation2019; Alford et al., Citation2021). This study seeks to establish the motivations for Southern actors to shape standards in relation to their interactions with value chain actors; predominately lead firms. The decision for Southern standard setters to engage in synergistic versus antagonistic forms of governance is likely to be linked to the sector-specific dynamics of particular value chains, and to the actors’ reflection on what can realistically be achieved.

Methodology and case study selection

A comparative case study methodology (Yin, 2009) was used to generate insightful data which captured the development of Southern sustainability standards governing Chinese apparel and Indian tea. Fieldwork was undertaken in the UK, the Netherlands, China and India from 2014-2017 and consisted of in-depth, semi-structured interviews with a total of 107 individuals from lead firms, supplier firms, government bodies, trade unions and civil society. The key commercial and institutional actors within Chinese apparel and Indian tea were identified using a GVC-based mapping exercise, which utilised extensive data bases including trade data, company reports and other relevant secondary data. Interviewees were identified who were: (a) explicitly linked to the processes of formulating and implementing CSC9000T for the Chinese apparel sector and Trustea for the Indian tea sector; and/or (b) key actors within the respective value chains of production and/or (c) experts on local sustainability standards in China and India. Accordingly, the majority of interviewees were familiar with the respective standard, albeit to different degrees. and detail the interviewee types, the number of participants and the locations of the interviews for China and India respectively.

Table 2. Interviews in China.

Table 3. Interviews in India.

Following the identification of participants, open-ended interview guides were developed which explored the drivers for the development of CSC9000T and Trustea, with key questions for participants covering the processes through which these standards were implemented, the challenges involved in their roll-out and the role(s) played by state, firms and civil society actors. Interviews also sought to uncover how the process of standard development intersected with the broader political economies of production within the two sectors and countries. Most interviews lasted ninety minutes and in some cases respondents were interviewed more than once. The majority of interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed, with extensive note taking utilised when recording was not possible. The majority of interviews relating to the CSC9000T apparel standard took place in Beijing, in textile and apparel clusters in Zhejiang province and Guangdong province, as well as in Hong Kong and Shanghai while interviews relating to the Trustea tea standard took place in Kolkata, Bengaluru and Delhi, and in the Netherlands and the UK.

Methodologically, the comparative focus on the development of standards in China and India sheds light on how relations between public and private actors at the local and transnational scale impact on the success of such standards. Our purpose here is to challenge the homogenising discourses surrounding the ‘global South’ and to demonstrate how divergent actors approach the development of sustainability standards in an increasingly multi-polar world; one in which corporations dominate the structures of trade and production, but also a world in which trade, production and consumption is growing across and within emerging markets. As such, we contribute to the research challenge to recentre Southern actors within the value chain framework and to empirically demonstrate the ways through which public and private actors in the South have sought to shape voluntary standards within value chains through synergistic versus antagonistic governance processes.

This comparative study offers insights into how public and private actors in different institutional contexts develop Southern-led/oriented sustainability standards and how these efforts co-exist and intersect with established transnational sustainability standards. Our focus on China and India, and the clothing and tea sectors, is purposive. As the leading emerging economies of the last two decades, China and India actively engage in the ‘rule-setting’ agenda around the governance of global trade (Narlikar, Citation2013). This is reflected in their robust participation within the World Trade Organisation (WTO), their claims on ‘sovereignty’ around the setting and enforcement of standards, and the development of new, and increasingly more stringent, regulatory norms on labor, the environment and corporate social responsibility (CSR). Since 2007 China has promulgated a series of labor reforms (Chan & Nadvi, Citation2014) and developed a range of public regulations addressing environmental concerns as well as corporate responsibility (Braun-Munzinger, Citation2018, Citation2019). In 2013 India brought in a CSR law mandating that all profit-making enterprises had to financially contribute to ‘social responsibility’ goals (Gatti et al., Citation2019). Emerging economies, and especially the growth of China, underline the rapidly expanding heterogeneity within the developing world. At the same time, China’s, and India’s, exceptionalism underlines the need for a more careful consideration of how actors within these emerging economies might choose to develop new sustainability standards.

Recent trends in the trade, production and regulation of Chinese apparel and Indian tea

Production, trade and value chain dynamics in the Chinese apparel sector

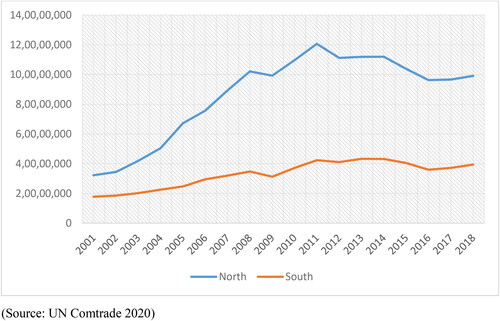

Although the world’s leading player in the global textiles and clothing sector, accounting for 31.6 per cent of global apparel exports in 2020 (Statista 2020), China’s participation within apparel GVCs has a relatively short history dating back to the early 1980s. The opening up of the Chinese economy in 1978 offered an opportunity for Hong Kong and subsequently Taiwanese apparel producers to move to lower cost production locations on the Chinese mainland. Following this, apparel manufacturing became especially visible in the Pearl and Yangtze River deltas, where gradual external opening though Special Economic Zones resulted in a specialization within different aspects of clothing production (Yeung, Citation2015). By 2004, China was the world’s biggest garment exporter, with 22% of global exports (Braun-Munzinger, Citation2018). While export-oriented production into US and European markets remains critical to Chinese apparel, exports to southern markets- particularly India, Brazil, Russia and Turkey have increased in recent years (see ). Moreover, domestic demand has grown, with over half of China’s clothing production now estimated to enter the local market (Zhu & Pickles, Citation2014). Both high and low-end producers have successfully forged links within the domestic market, while rising labor costs has led many producers to relocate to lower cost regions within and outside of China (Zhu & Pickles, Citation2014).

Figure 1. Chinese exports of apparel to global North and global South.

(Source: UN Comtrade, Citation2020).

The governance of social and environmental standards in Chinese apparel manufacturing can be seen both within the GVC, in which private standards have become increasingly common, as well as through national public regulations (Braun-Munzinger, Citation2018). In the GVC, standards were first introduced by global buyers such as Levi’s, Nike and GAP in response to anti-sweatshop campaigns of NGOs in the 1990s. These sustainability standards included firm-specific codes of conduct as well as broader standards such as Social Accountability International’s SA8000 code, which is widely credited with ‘bringing CSR to China’ (Bartley, Citation2018, p. 164). The Chinese state has also enacted various labor laws in recent years. In the mid-1990s, a new legal framework for labor, wages and workers’ contractual rights replaced the system of “socialist” administrative regulation (Chan, Citation2010). This was followed in 2007–2008 with the introduction of new labor laws including the Employment Promotion Law, the Labor Dispute Mediation and Arbitration Law and the Labor Contract Law which aimed to regulate workplace relations and limit labor conflict (Chan & Nadvi, Citation2014). Implementation is largely left to provincial and local levels of government; thus compliance is uneven and allegations of poor working conditions and evidence of labor disputes in Chinese export factories have continued to mount (Chan & Hui, Citation2014). While the introduction of new labor laws was a response to growing labor unrest, recent industrial policies created by the Chinese state also incorporate initiatives to tackle social and environmental issues within production as the state pushes apparel firms to move up the value chain (Zhu & Pickles, Citation2014). While domestic demand is growing, exports to the global North remain critical for many Chinese apparel firms, and export production is still largely governed by GVC dynamics and pressures. Conforming to sustainability standards enforced by GVC lead firms is vital to ensure continued exports to high value-adding markets.

Markets, production and regulation in India’s tea sector

India is the world’s second biggest producer, and fourth biggest exporter of tea. However, domestic tea consumption far outstrips tea exports in both volume and value terms (FAO, Citation2015). The GVC is dominated by large global firms, in particular the British-Dutch conglomerate Unilever and the Indian conglomerate Tata which respectively account for 12% and 4% of the global tea market (Potts et al., Citation2014). The domestic value chain (DVC) for tea is also dominated by these same large firms with Hindustan Unilever (a subsidiary of Unilever) and Tata together controlling 54% of the domestic tea market. As their market shares have risen, lead firms have largely divested from direct ownership of tea production to focus on core competencies such as blending, marketing and product innovation (Neilson & Pritchard, Citation2011; Langford, Citation2021).

The Indian tea industry is divided into two distinct production segments: plantation estates (over 10.12 hectares in size) that produce approximately 52% of Indian tea, and smallholder farms (below 10.12 hectares) which produce the remainder. Plantations are governed by a range of national laws and regulations including the 1951 Plantation Labor Act (PLA) which offers statutory protection for workers alongside a tripartite system for wage negotiations between representatives of industry, trade unions and the state government (Neilson & Pritchard, Citation2011). However, circumvention of labor laws is evident in the sector. Smallholder tea farms are not subject to the PLA’s rules and norms and are largely unregulated. While smallholder-produced tea accounted for just 7% of total production in 1991, this has grown rapidly and today an estimated 180,448 small tea growers producing tea on 161,648 hectares provide 48% of India’s total tea production (India Tea Association, 2019). Whereas plantation estates supply global and domestic markets, smallholders exclusively supply the domestic market ().

Table 4. Production (million kg) of plantations/registered tea gardens vs smallholders in India.

To export tea via the GVC, plantations must meet a range of product and process standards set by global lead firms and importing states (Neilson & Pritchard, Citation2011). This includes private standards governing labor and environmental production issues introduced by global lead firms from the late 1990s onwards, as well as national and regional food safety standards. The Rainforest Alliance (RA) certification scheme is the most common private voluntary tea standard worldwide and is used extensively for Indian tea exports to OECD markets. However, evidence suggests that plantation-based tea workers continue to suffer from low wages and inadequate working and living conditions in spite of private certification (LeBaron, Citation2018).

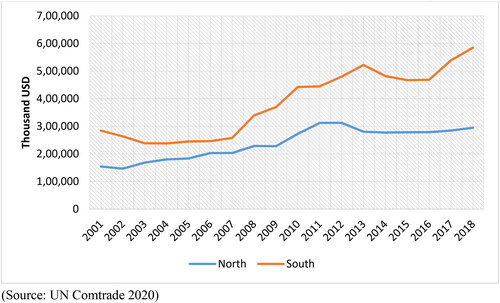

The Indian tea industry has been subject to significant shifts in the geographies of consumption over recent decades. Whilst the value of tea sales increased in both northern and southern markets in recent decades, from 2010, tea sales in the north plateaued whereas the export value of tea sold in southern markets increased by approximately 33 per cent (see ).

Figure 2. Exports of Indian tea to the global North and global South 2000–2018 (USD).

(Source: UN Comtrade, Citation2020).

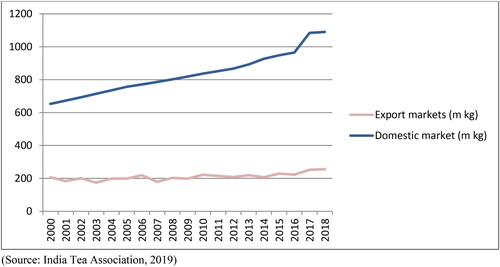

In addition, there has been a significant increase in domestic tea consumption. During the period 2000–2018, the volume of tea consumed domestically rose from 600 million kg to over 1000 million kg (see ) and while per capita consumption is still relatively low, the overall increase in demand means that almost 90 per cent of the tea produced in India today feeds domestic demand (Langford, Citation2021). The rapid growth in domestic tea consumption has been accompanied by only marginal increase in the volume of tea exported since 2000 (see ).

Figure 3. Changing volume of tea production for exports versus domestic market 2000–2018 (in million kg).

(Source: India Tea Association, 2019).

The growing significance of the domestic market warrants further consideration of how domestic production is governed. As stated earlier, the domestic value chain (DVC) is largely controlled by two lead firms: Hindustan Unilever (HUL) and Tata. These firms are simultaneously considered as local and global (HUL is a subsidiary of Unilever while Tata owns the British brand Tetley) with significant overlaps between their global and local identities (Langford, Citation2021). However, while within India both lead firms only source from plantations for exports, they source from plantations and smallholders for the domestic market (Langford, Citation2021). Tea production for the DVC faces different regulatory challenges and Rainforest Alliance and other certification programmes do not cover smallholders nor domestically-focused plantations. Likewise, smallholders are largely unregulated by the state. As domestic lead firms have increased their dependence on smallholders, production has become reliant upon family labor, with some additional use of waged labor when required. Wages are unregulated and often lower than for plantation-based labor (BASIC, Citation2019).

In summary, we see key points of convergence and divergence within these two sectors and countries. Both sectors were historically export-oriented and have long been governed by global standards set by lead firms, MSIs and public agencies. Yet, in both China and India we see a growth in domestic and southern market sales for clothing and tea respectively. While the Chinese state has become increasingly interventionist regarding social and environmental problems within apparel production, Indian state actors continue to govern through archaic laws which only cover approximately half of the tea produced within the country. These differing approaches to regulation may offer insights into wider state engagement within the development of Southern sustainability standards. In light of these similarities and differences, and the wider political economy of trade, production and regulation in Chinese clothing and Indian tea, we now turn to a closer analysis of the development of the CSC9000T standard for Chinese apparel (Section 4) and the Trustea standard for Indian tea (Section 5). We investigate the role of public and private actors, at local and global scales, in the formulation and uptake of these Southern standards, recognising that production in both sectors is embedded within intersecting value chains feeding global and domestic markets.

Actors driving the development and uptake of CSC9000T

The CSC9000T standard is primarily driven by national state interests. It was launched in 2005 by the China National Textile and Apparel Council (CNTAC), which is both the umbrella business association for the Chinese textile and apparel sector as well as a state-linked organisation (Braun-Munzinger, Citation2018). CSC9000T comprises voluntary guidelines on labor and environmental standards for Chinese apparel firms. It was created as a management system and promoted as the first Chinese-led CSR management system to govern the apparel GVC.

There are three key shifts which provide the rationale for the development of CSC9000T from a political economy perspective. Firstly, in 2005 the Multi-Fibre Arrangement (MFA) governing global apparel trade, ended. Following this, Chinese apparel exports (both woven and knitted fabric) soared, rising from US$54.8 billion in 2004 to US$162 billion in 2015 (UN Comtrade, Citation2021). Whilst expanding exports were welcomed by producers, this was accompanied by the requirement to meet export standards set by lead firms relating to labor and the environment. This led to a growing domestic interest in capacity building to better meet the requirements of transnational sustainability standards.

Secondly, the industry was experiencing growing labor shortages and numerous wildcat strikes which led the government to develop new regulatory frameworks and initiatives to respond to the crisis (Silver & Zhang, Citation2009). This was accompanied by a growing interest in CSR in China, in which the traditional perception of CSR standards as trade barriers in export markets was supplanted by a growth in indigenous domestic policies and standards related to the social responsibility of firms (Lin, Citation2010, Noronha et al., Citation2013, Jiang, Citation2011),

Thirdly, these developments in the apparel sector took place in a broader context where domestic political concerns regarding the reach of international private standards were emerging. In 2004, just one year before the launch of CSC9000T, the Certification and Accreditation Administration (CNCA) (a Chinese state agency) announced that the US-based Social Accountability International’s SA8000 certification standard (which was widely used by US apparel brands in certifying their Chinese suppliers), would require Chinese government approval to continue operating within the country (Bartley, Citation2018).

It is within this context, marked by increased exports, adherence to transnational sustainability standards and growing domestic interest in regulatory reform, as well as growing resistance to international standards, that CSC9000T emerges. The following section explores how these three transformations shaped the tendency for local actors to engage in synergistic and/or antagonistic practices within the development of CSC9000T.

CNTAC, the primary organisation responsible for creating CSC9000T, originates out of the former Chinese Ministry of Textiles and is considered a state-driven organisation due to the contemporary political economy of state-business relations within China. Alongside CNTAC, CSC9000T also received additional support from the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) and the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) who co-hosted several of CNTAC’s annual CSR meetings. While CNTAC’s members (individual apparel companies) and sub-associations were consulted during the design phase, the initiative was driven by CNTAC’s Beijing headquarters and not from any pressure or demand by individual member companies. This reflected the hierarchical relationship between CNTAC and its members, as well as the ‘top-down’ nature of state rule within China (Braun-Munzinger, Citation2018).

lists the key public and private actors shaping CSC9000T at the global and local scales, in which public actors played a primary role. It illustrates an explicit role for local actors within the shaping of CSC9000T and a more implicit role for global actors.

Table 5. Actors involved in shaping CSC9000T.

The design of CSC9000T can be seen as synergistic in the sense that CNTAC took existing global voluntary standards prevalent within the apparel GVC as reference points for formulating CSC9000T. The 2005 version of CSC9000T refers to UN conventions on human rights, the global compact, various International Standards Organisation (ISO) standards and the business-run Business and Social Compliance Initiative (BSCI) management manual. In addition, CSC9000T broadly corresponds to requirements of both BSCI and the Social Accountability International’s SA8000 standard, and, like SA8000, operates as a management system.

Another interesting example of initial mimicry relates to CNTAC’s development of a multi-stakeholder forum, again replicating best practices within Northern-led sustainability standards. This MSI was referred to as the Responsible Supply Chain Association (RSCA) and was designed to allow the participation of global lead firms and Chinese suppliers. Synergistic practices are also evident in CSC9000T’s formalised attempt to align with established standards within the transnational field of sustainability governance. For example, CNTAC pursued recognition of CSC9000T by the European BSCI, and in 2007 a cooperation agreement was formalised by the two parties with the intention of mutual recognition.

In spite of these synergistic practices, there are important local dynamics which undermined these efforts and instead demonstrate resistance to imitation of GVC-led standards. For example, the multi-stakeholder forum RSCA remained nested within the internal structures of CNTAC and therefore did not mimic the typical MSI structures seen in established standards. As a result, interest among global lead firms in joining was limited with just one Western retailer, Hudson’s Bay, becoming a member. The dominance of CNTAC over the RSCA therefore came at the expense of its multi-stakeholder intention (Braun-Munzinger, Citation2018, p. 146).

Likewise, the attempt to align CSC9000T with BSCI may in fact represent attempts by the Chinese state to undermine the dominant apparel standard SA 8000. A strategy of partnering with one international standard to challenge the dominance of another was used in Chinese forestry certification during this period wherein a state-led certification programme (China Forest Certification Council) partnered with a global initiative (Program for the Endorsement of Forest Certification) whilst subjecting the dominant standard Forestry Stewardship Council (FSC) to increased controls (Bartley, Citation2018). Given state hostility to the apparel standard SA8000, it is possible that the partnership between CSC9000T and BSCI was pursued out of an antagonistic motivation to marginalise SA8000 in Chinese apparel. The 2004 declarations by the state regarding SA8000’s legitimacy to govern in China could indicate that this may have been a factor (Bartley, Citation2018).

Alongside these synergistic dynamics, there is also evidence of antagonistic practices present within the development of CSC9000T in which CSC9000T’s insistence upon the maintenance of local distinctions prevented alignment with BSCI. Primarily, this related to the role of third-party auditing within the certification process. CNTAC wanted CSC9000T to be a largely capacity building management system in which firms were not required to conduct regular audits after being awarded a CNTAC certificate as an ‘implementing enterprise’. In contrast, BSCI required the conduct of regular performance evaluation audits which would be conducted by independent auditors. Given the fact that third-party auditing was a widely adopted norm within sustainability governance within GVCs and was associated with higher levels of legitimacy (due to the regular and independent nature of the audits), CSC9000T’s alternative system was unable to garner credence amongst global standard setters or amongst the lead firms sourcing from China. CSC9000T has not been used by any of the global apparel lead firms to govern their value chains.

Although CSC9000T failed to align with BSCI, CNTAC continued to partner with international actors during its training programmes- including ILO, UNIDO, BSCI and the EU-China Trade project. From a perspective of synergistic governance, some actors presented CSC9000T as a stepping-stone to international standards required by lead firms. From this point of view, the training activities on CSC9000T as a social management system may have contributed to preparing companies for adoption of these standards, or with social management systems as new tools of sustainability governance. At the end of the pilot programme, 62 out of the initial 92 companies were awarded ‘implementing enterprise’ status after a successful re-evaluation of compliance. Yet, these international partnerships during the training programme did not compensate for the lack of interest amongst global lead firms to adopt the standard for their Chinese apparel suppliers, nor the failure to achieve joint recognition with the BSCI. Given the hegemonic power of global lead firms to determine which governance systems should be adopted within GVCs, this meant that there was little incentive for Chinese apparel suppliers to become CSC9000T compliant if GVC lead firms did not recognise the standard.

CSC9000T’s inability to become a mainstream standard arguably also reflects that it emerged as part of a process of experimentation with voluntary sustainability standards as regulatory tools in China. Sustainability standards governing GVCs have often been seen as emerging in response to regulatory ‘gaps’ but given that apparel production was already governed by numerous sustainability standards as well as new state legislation (as discussed in Section 4), it became less clear what the exact regulatory purpose of CSC9000T was. However, CSC 9000 T did help state-led Chinese sectoral bodies, such as CNTAC, ‘learn’ how to formulate and develop a major sectoral standard, involving both learning, as well as differentiating, from existing global standards within the apparel sector.

Developing national sovereignty in the arena of standard setting is clearly of critical and competitive value to the Chinese state. However, other studies of the apparel sector in China illustrate an evolution in attitude to transnational standards over this period; moving from initial hostility towards a recognition that such standards do not in fact challenge low wages or harm China’s competitive advantage. For example, Bartley (Citation2018) illustrates that SA 8000 ‘diffuse[s] managerialism to Chinese factories’ through its emphasis on record-keeping and management systems as assurances of decent conditions. Transnational standards therefore aren’t challenging the fundamental competitiveness of the sector on low wages and exploitation, but instead contributing to the enhanced efficiency of management systems. The development of CSC9000T not only seeks to replicate such efforts at the firm level; it also builds capacity to develop such sustainability standards and the management systems needed to implement them.

CSC9000T, as a state-led sustainability standard, exhibits elements of both synergistic and antagonistic behaviour within its development and implementation. The case illustrates that the transnational field remains important within the development of Southern standards, even when they are directed by state actors within authoritarian contexts. Indeed, antagonistic practices within CSC9000T’s development ultimately prevent its wider uptake by lead firms- and the refusal to adopt third party certification and regular audits means it is unable to partner with BSCI or become more widely recognised as a legitimate standard. This refusal is an important indicator of what Southern actors in the Chinese context see as acceptable in relation to sustainability governance, which differs from the dominant transnational sustainability standards.

Although CSC9000T has evolved over time, it remains relatively unsuccessful in achieving adoption by companies. The CSC9000T example suggests that state-led voluntary standards are unlikely to succeed in GVCs where global lead firms hold hegemonic power and continue to dictate governance over local suppliers that shape trade and production practices. This ‘top-down’ and state-directed standard was developed partly as a synergistic and partly as an antagonistic form of governance. It was launched in a period in which on the one hand, Chinese policymakers were actively promoting the concept of CSR (Lin, Citation2010) and experimenting with new forms of sustainability governance, and on the other hand, at a time when the Chinese state was seeking to reassert sovereignty over the governance of GVCs.

Actors, drivers and influences in the creation of trustea

Trustea launched in 2013 as the first multi-stakeholder initiative governing the labor and environmental conditions of tea produced for India’s domestic market. By 2019, it claimed to have certified over 49% of India’s total tea production, including 81,841 small tea growers and 622 estates and bought leaf factories (IDH 2019). Trustea’s code of conduct applies to plantations and smallholders and covers social concerns (addressing labor standards, worker protection and welfare), environmental concerns (on pesticides, waste disposal and water management) and food safety standards. Audits take place on a bi-annual basis through a third-party verification scheme. Trustea markets itself as a locally owned sustainability standard which discursively distances itself from export-oriented standards by claiming that it is ‘for the [Indian] industry, by the industry’ (Trustea website, 2013). Whilst Trustea was explicitly developed for the domestic value chain (DVC), it should be noted that the DVC is predominately co-ordinated by the same lead firms as the GVC (as discussed in Section 4). Therefore, its development should still be considered as part of a wider discussion on how Southern actors interact with other GVC and DVC based actors (predominantly lead firms) involved in Indian tea production, and how such interactions ultimately shape the degree to which Trustea seeks to imitate or deviate from the established, and corporate-led, global standards governing the tea GVC.

Like CSC9000T, Trustea developed during a turbulent moment within the wider political economy of the Indian tea industry; with the expansion of domestic consumption, the growth of smallholder production and the divestment of corporations from plantation ownership creating numerous regulatory challenges (Langford, Citation2021). At the global scale, leading corporations within the industry were also considering the implementation of sustainability standards within emerging markets. illustrates the key public, private and social governance actors shaping the development of the Trustea standard.

Table 6. Private actors shaping Trustea’s development: global-local intersections.

While the Tea Board of India (a state-based actor) is a prominent member of Trustea, illustrates that Trustea involves corporates and NGOs, as well as state actors, within its development. We investigate how this confluence of public and private actors, some of whom can be considered governance actors within the GVC as well as the DVC, have come to shape Trustea and how relations between public and private actors within such processes can be understood through synergistic versus antagonistic processes of standard development.

In 2010, Unilever announced a ‘Sustainable Living Plan’ in which it committed to certify production in all markets it operated within. This included the Indian tea market where its subsidiary Hindustan Lever (HUL) has a large market share. Rainforest Alliance (RA) (at the time the largest global tea standard certifying tea exported by Unilever) was tasked with expanding certification to the domestic Indian tea market. However, two critical obstacles emerged. Firstly, RA lacked the capacity to certify smallholder producers who were a major supply base for domestic tea. Secondly, RA was unwilling to align its global code to the specificities of local Indian labor laws on minimum working age (Langford, Citation2019). These local considerations presented a dilemma, and realising the need to mirror national regulations, Unilever and HUL decided that a separate standard based on the ‘realities’ of the domestic tea sector was needed. However, this standard also had to be modelled on global norms for it to be credible and effective in meeting the criteria outlined within Unilever’s ‘Sustainable Living Plan’. Due to these circumstances, numerous linkages were maintained with GVC-based governance actors: RA was appointed to Trustea’s advisory board, and the Trustea code was largely aligned with RA whilst also incorporating local laws and regulations. Trustea’s initial conception was therefore largely imitative and therefore developed in synergy with pre-established sustainability standards within the sector. However, closer co-ordination with local organisations, in particular the Tea Board of India and alignment with Indian regulations, was seen as necessary to lend legitimacy to Trustea and to increase producer support (Langford & Fransen, Citation2022).

The Tea Board of India was invited to join Trustea as a key state representative almost a year into Trustea’s development and was afforded two prominent positions within the internal governance structure as Chair of the Programme Committee and Chair of the Advisory Committee. It also became the public champion of Trustea and its logo was frequently displayed on Trustea-related publications. Initially, there was scepticism on the part of lead firms who were concerned about the possible politicisation of the Trustea standard and the Tea Board was not included in the Funders Committee (which met privately before other stakeholder meetings took place) (Bitzer & Marazzi, Citation2021). Nevertheless, Tea Board participation ameliorated producer scepticism regarding the role of private governance within the domestic industry.

The Tea Board’s willingness to support Trustea is indicative of its close ties with corporate actors within the industry, especially Tata Global Beverages. While public actors chose to abrogate responsibility for governance to the private sector, they nevertheless benefited from participation as ‘champion’ of Trustea. For example, when the Minister of Commerce was asked in the Indian Parliament (Lok Sabha) what the government was doing to tackle the problems raised by the Greenpeace campaign on pesticide use and working conditions in the Indian tea sector (Greenpeace, Citation2013), they positioned Trustea as a state-led, rather than a corporate-led response (Langford, Citation2019). Overall, the membership of the Tea Board did lead to the incorporation of local standards and norms including the adoption of the Plant Protection Code and food safety regulations created by the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI). Thus, examples of synergistic governance were present in relation to both national regulations as well as conforming closely to norms set by RA and Unilever within the pre-existing governance of the tea GVC.

More prominent within the development of Trustea was the critical role played by various global actors. This included the Dutch state who, at the request of Unilever funded Trustea’s development through IDH (Initiatief Duurzame Handel); an organisation formed in 2008 in the Netherlands to facilitate public-private partnerships (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands, 2014). One condition of funding was that Unilever’s major competitor, Tata, would be invited to join the standard. Therefore, state actors based in the global North were instrumental in shaping the institutional design of Trustea and creating a larger, industry-wide standard. This was due to IDH’s policy to only fund MSIs where there was more than one corporation involved. IDH funded one third of the total costs of Trustea’s development and the two lead firms (Hindustan Unilever and Tata) contributed a further third each. Additional evidence of global-local ties can be found in the role played by Solidaridad Asia; a nationally registered NGO which nevertheless has institutional and financial linkages to the Netherlands and is the de facto regional office of the Dutch-based international NGO Solidaridad. HUL approached Solidaridad Asia to design Trustea’s governance and audit systems. Whilst both HUL and Solidaridad Asia can be considered Southern actors, it was the prior relationship between the Dutch headquarters of the two organisations which helped to forge the partnership between Solidaridad Asia and HUL. Overall, state willingness to allow private actors to shape the overall design of Trustea led to a synergistic model of governance which not only involved active collaboration but also the involvement of public and private actors outside the domestic institutional environment.

Trustea has become the most widespread sustainability standard in the Indian tea sector, covering 49% of total Indian tea production and widely recognised as legitimate by both producers and domestic consumers in the Indian tea market. Trustea’s development reflects the broader political economy structures of Indian tea production in which GVC-based governance actors can assert influence within the construction of a domestically oriented standard. Its code of conduct largely draws upon Rainforest Alliance norms and thus imitates existing ‘rules’ shaping exports to Northern markets. Yet, whilst Trustea developed out of global corporate interest in governing Southern markets, its success depended upon acceptance by local state actors and state willingness to support private governance as a mode of regulating the domestic industry.

Overall, Trustea can be considered a form of synergistic governance which aligned with pre-existing corporate-led standards within the GVC. It is representative of a process wherein states and corporations cooperated for mutual benefit. By developing a synergistic standard through a collaborative process, both private and public actors were able to benefit from Trustea’s reputation and legitimacy. The significant role of private actors (i.e. firms and civil society) within Trustea’s development therefore represents a continuation of, rather than a break from, the key norms and actors guiding the development of sustainability standards in the global North since the 1990s.

The case of Trustea illustrates the importance of situating the development of Southern sustainability standards within a political economy framework which accounts for the structural power of lead firms, the changing market preferences of end markets as well as the efficacy of pre-existing public and private forms of governance. Synergistic and antagonistic governance practices are largely shaped by these complex intersections between weak regulatory enforcement, consumer and civil society pressures as well as the dominant role of multinationals who control large percentages of both the global and domestic value chains. Overall, the standard is predominantly shaped by lead firms who are open to cooperation with public actors (and vice versa) due to the identification of common interests.

Conclusion

The emergence of Southern-led sustainability standards in the 21st century raises important questions regarding the origins of their development and the role that key public and private governance actors play within this. It further calls for a closer analysis of how these voluntary standards relate to, intersect with, and potentially imitate or deviate from the pre-existing sustainability standards governing GVCs. Whilst initial studies have positioned their emergence in relation to political struggles between Southern actors and pre-existing GVC-based standards, the exact nature of relations between various public and private actors at different scales within the processes of standard creation remains overlooked. Furthermore, the role that wider value chain dynamics within specific sectors can play in shaping power relations between governance actors and the resulting interdependencies and intersections that these structures produce (in the form of synergistic versus antagonistic governance practices) is also not well understood.

This article addressed these gaps through a comparative study of Chinese clothing and Indian tea standards. Our central research questions were: First, how do public and private actors interact in the development of Southern standards? Second, how do wider commercial dynamics shape the uptake of such standards? Drawing on the concept of synergistic versus antagonistic governance, we examined the interests of, and tensions between different public and private governance actors in the development and uptake of the Chinese CSC9000T apparel and the Indian Trustea tea standards. By placing the empirical study of these Southern sustainability standards within this framework, we analysed their development through a relational approach. Consequently, our analysis has illustrated how the ‘transnational field’ interacts with the local political environment as well as different value chain dynamics to shape specific standards and their uptake.

Our comparative case study analysis provided a detailed empirical analysis of the processes of standard formation which considered local processes of standard development alongside wider value chain dynamics. This allowed for a multi-scalar comprehension of how and why standards develop through synergistic and/or antagonistic practices of governance. The findings of this multi-scalar approach challenge predominant claims within the literature on Southern-led sustainability standards in two key ways: Firstly, by situating the development of standards within the established ‘transnational field’ of buyer-driven value chains (apparel and tea), we highlight the direct and indirect role that powerful lead firms play in shaping the form and structure of Southern standards. Our cases suggest that lead firm involvement and/or imitation of established sustainability standard norms (which lead firms are participating within) may influence the overall uptake of new standards. We find that the CSC9000T standard failed to gain traction due to a reluctance of local state-linked actors to align their audit systems to pre-existing global standards. Given that lead firms already had established standards and codes of conduct, it was unclear what the added value of CSC9000T would be. Trustea, on the other hand, largely develops without the explicit control of state-linked actors. Whilst some adaptations are made to meet the specificities of the local institutional environment, the actors and norms driving Trustea’s development are largely linked to the wider value chain and predominantly to the interests of lead firms. Therefore, many aspects were formed through synergistic processes that drew on existing global standards. Together, the cases of CSC9000T and Trustea suggest that the agency of Southern actors in shaping Southern standards is heavily impacted by wider value chain dynamics within the broader transnational field of sustainability governance, and that Southern standards may in fact be led by transnationally-linked actors and/or processes to begin with.

Secondly, we highlight that, despite the important role played by lead firms and established GVC-oriented sustainability standards, local political relations between public and private actors affect the degree to which new sustainability standards choose to mimic established norms (as set in the global North), or to seek to create alternatives. The case of China illustrates that public actors were largely hesitant to replicate global norms because the state is the primary governor of production and there is little space for private and/or civil society leadership within this authoritarian context. In contrast, the case of India illustrates that public actors were willing to allow the private sector to shape a domestic standard that mirrored existing global standards and their certification processes; reflecting a more generalised inertia on the part of public actors when it comes to the development of new regulations as well as the enforcement of existing labour and environmental regulations. What is perhaps most interesting, is that the CSC9000T standard was designed to govern global value chains whereas Trustea was focused on the domestic market. This highlights a willingness on the part of the Indian Tea Board to embrace private standards within the domestic context, as well as an interest on the part of CNTAC to replicate and challenge pre-existing international standards at a global, rather than national scale.

Altogether, our findings demonstrate the need to conceptualise Southern standards not as a national response to governance challenges led by Southern actors, but instead as the outcome of often entangled, complex and ever-changing public-private intersections at the transnational and local levels. Seen from this perspective, the degree and extent to which Southern actors engage in synergistic versus antagonistic practices when shaping sustainability standards can be seen as an outcome of competing tensions between the structural transnational field of value chain governance and the agency of local actors.

Overall, this article illustrates that the development of Southern sustainability standards is not simply the outcome of the agency of local actors; but that lead firms in key end markets are important to their overall success. This is of course linked to the fact that voluntary standards aim to govern value chains, rather than territories. Therefore, despite the significance of state sovereignty at the national scale, wider uptake of voluntary sustainability standards must dovetail with the market-based imperatives of corporations, thereby favouring standards developed through synergistic processes. Future research on the development and overall success of Southern-oriented sustainability standards must therefore go beyond the politics of who shapes southern standards (within confined national contexts) to also examine the wider structures of production (as maintained through global, regional and domestic value chains) that influence the shaping of such standards.

Disclosure statement

The authors confirm that there are no relevant financial or non-financial competing interests to report. Dr Corinna Braun Munzinger wishes to express that the article does not reflect the views of GIZ, but the research conducted by the author as part of their PhD research at the University of Manchester’s Global Development Institute.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Natalie J. Langford

Dr Natalie J. Langford is a Lecturer in Sustainability at the University of Sheffield, United Kingdom. Her work is focused on globalisation in the 21st century and the governance of production through various rules-based systems. Her primary focus has been on the development of Southern sustainability standards and the interaction of public and private actors within questions of ‘rule-making’ within the global economy.

Khalid Nadvi

Professor Khalid Nadvi is a Political Economist based at the Global Development Institute at the University of Manchester, United Kingdom. His work is focused on issues relating to trade and development. In particular, his work has focused on small enterprise clusters, global value chains and production networks, global standards, corporate social responsibility and technological upgrading.

Corinna Braun-Munzinger

Dr Corinna Braun-Munzinger is an Advisor in the GIZ Competence Centre on Economic Policy and Private Sector Development in Eschborn, Germany. Her work focuses on international trade and development. In her PhD research conducted at the University of Manchester she examined the role of local business associations in the governance of sustainability standards in global production networks.

Notes

1 3 interviews with international actors outside China were conducted remotely via Skype.

References

- Alford, M. (2020). Antagonistic governance in South African fruit global production networks: A neo‐Gramscian perspective. Global Networks, 20(1), 42–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/glob.12223

- Alford, M., & Phillips, N. (2018). The political economy of state governance in global production networks: Change, crisis and contestation in the South African fruit sector. Review of International Political Economy, 25(1), 98–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2017.1423367

- Alford, M., Visser, M., & Barrientos, S. (2021). Southern actors and the governance of labour standards in global production networks: The case of South African fruit and wine. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 53(8), 1915–1934. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X211033303

- Amengual, M., & Chirot, L. (2016). Reinforcing the state: Transnational and state labour regulation in Indonesia. International Labour Review, 69(5), 1056–1080. https://doi.org/10.1177/0019793916654927

- Bair, J. (2017). Contextualising compliance: Hybrid governance in global value chains. New Political Economy, 22(2), 169–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2016.1273340

- Bair, J., & Palpacuer, F. (2015). CSR beyond the corporation: Contested governance in global value chains. Global Networks, 15(s1), S1–S19. https://doi.org/10.1111/glob.12085

- De Bakker, F. G. A., Rasche, A., & Ponte, S. (2019). ‘ Multi-stakeholder initiatives on sustainability: A cross-disciplinary review and research agenda for business ethics. Business Ethics Quarterly, 29(03), 343–383. https://doi.org/10.1017/beq.2019.10

- Bartley, T. (2014). Transnational governance and the re-centered state: Sustainability or legality? Regulation and Governance, 8(1), 93–109. https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12051

- Bartley, T. (2018). Rules without rights: Land, labor, and private authority in the global economy. Oxford University Press.

- BASIC. (2019). Study of Assam tea value chains research report. Bureau for the Appraisal of Social Impacts.

- Bitzer, V., & Marazzi, A. (2021). Southern sustainability initiatives in agricultural value chains: A question of enhanced inclusiveness? The case of Trustea in India. Agriculture and Human Values, 38(2), 381–315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-020-10151-4

- Braun-Munzinger, C. (2018). [Business associations and the governance of sustainability, standards in global production networks: The case of the CSC9000T standard in the Chinese apparel sector]. [PhD thesis]. The University of Manchester.

- Braun-Munzinger, C. (2019). Chinese CSR standards and industrial policy in GPNs. Critical Perspectives on International Business, 16(2), 165–185. https://doi.org/10.1108/cpoib-12-2017-0086

- Cashore, B. W., Auld, G., & Newsom, D. (2004). Governing through markets: Forest certification and the emergence of non-state authority. Yale University Press.

- Chan, C. K. C. (2010). The challenge of labour in China: Strikes and the changing labour regime in global factories. Routledge.

- Chan, C. K. C., & Hui, E. S. L. (2014). The development of collective bargaining in China: From collective bargaining by riot to party state-led wage bargaining. The China Quarterly, 217, 221–242. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741013001409

- Chan, C. K. C., & Nadvi, K. (2014). Changing labour regulations and labour standards in China: Retrospect and challenges. International Labour Review, 153(4), 513–534. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1564-913X.2014.00214.x

- FAO. (2015). World tea production and trade: Current and future developments. http://www.fao.org/3/a-i4480e.pdf.

- Fransen, L. W. (2013). The embeddedness of responsible business practice: Exploring the interaction between national-institutional environments and corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 115(2), 213–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1395-2

- Gatti, L., Vishwanath, B., Seele, P., & Cottier, B. (2019). Are we moving beyond Voluntary CSR? Exploring theoretical and managerial implications of mandatory CSR resulting from the new Indian Companies Act. Journal of Business Ethics, 160(4), 961–972. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-3783-8

- Gereffi, G., & Lee, J. (2016). Economic and social upgrading in global value chains and industrial clusters: Why governance matters. Journal of Business Ethics, 133(1), 25–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2373-7

- Gereffi, G., Humphrey, J., & Sturgeon, T. (2005). The governance of global value chains. Review of International Political Economy, 12(1), 78–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290500049805

- Giessen, L., Burns, S., Sahide, M. A. K., & Wibowo, A. (2016). From governance to government: The strengthened role of state bureaucracies in forest and agricultural certification. Policy and Society, 35(1), 71–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polsoc.2016.02.001

- Greenpeace. (2013). Trouble brewing: Pesticide residues in tea samples from India. http://www.greenpeace.org/india/Global/india/image/2014/cocktail/download/TroubleBrewing.pdf [Accessed: 3 March 2015].

- Guarín, A., & Knorringa, P. (2014). New middle-class consumers in rising powers: Responsible consumption and private standards. Oxford Development Studies, 42(2), 151–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600818.2013.864757

- Henderson, J., Dicken, P., Hess, M., Coe, N., & Yeung, H. W. C. (2002). Global production networks and the analysis of economic development. Review of International Political Economy, 9(3), 436–464. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290210150842

- Horner, R. (2017). Beyond facilitator? State roles in global value chains and global production networks. Geography Compass, 11(2), e12307–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12307

- Horner, R., & Nadvi, K. (2018). Global value chains and the rise of the global South: Unpacking twenty-first century polycentric trade. Global Networks, 18(2), 207–237. https://doi.org/10.1111/glob.12180

- Hospes, O. (2014). Marking the success or end of global multi-stakeholder governance? The rise of national sustainability standards in Indonesia and Brazil for palm oil and soy. Agriculture and Human Values, 31(3), 425–437. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-014-9511-9

- Jiang, L. (2011). Chapter 7 development of corporate social responsibility in China, developments in corporate governance and responsibility Vol. 2. Emerald.