Abstract

Under what conditions do high levels of export concentration in a single market generate vulnerability to coercive economic power? This paper investigates that question by examining the experiences of Australian export-oriented industries that lost access to the Chinese market during a sanctions episode beginning in May 2020. Despite China being a dominant and highly valuable export market for many affected industries, the economic – and accordingly political – impacts of sanctions were more modest than anticipated. We argue the reason for this lies in autonomous market adjustments. Theoretically, we extend insights from research on how market dynamics condition the impact of sanctions that generate ‘supply shocks’ (such as oil embargoes) to the new domain of ‘demand shocks’, and present a model of the process of responding to unilateral import sanctions from the perspective of target exporters. We argue impacts can be diminished by three mechanisms: reallocation (selling sanctioned products to alternative markets), deflection (circumventing sanctions via intermediaries), and transformation (adjusting production processes to produce and sell different products). Empirically, we document variation in adjustment processes undertaken in nine Australian industries, and explore the conditions under which adjustments are viable depending upon differences in market dynamics across products.

Introduction

Under what conditions do high levels of export concentration in a single market generate vulnerability to coercive economic power? In 2020, China was the largest export destination for more than 30 countries, and the top trading partner of more than 120. Its economy features a vast and increasingly affluent middle class—making it one of the world’s largest and fastest growing markets for consumer goods and services—and requires enormous quantities of raw materials and other inputs to fuel its industrial development and massive export machine. In an increasingly contested geopolitical landscape, many assess China’s importance as an export market to be a potentially significant source of coercive leverage (see, e.g., Barwick et al., Citation2019; Chen & Garcia, Citation2016; Hanson et al., Citation2020; Harrell et al., Citation2018; Lai, Citation2021; Lim & Ferguson, Citation2021; O’Connell, Citation2021). Beijing is said to be both willing and able to impose significant economic costs on other states during political disputes by denying exporters access to the lucrative mainland market.

China’s campaign of economic coercion against Australia in 2020–21 represents an important test of this conventional wisdom. Easily the most valuable export destination for many Australian industries, Beijing’s abrupt disruption of imports of at least nine different products generated widespread concern, both within Australia and abroad, that Australia’s ‘dependence’ on China left it highly ‘vulnerable’.Footnote1 Commentators and analysts predicted the economic impacts would be severe, and that this would put Canberra under significant political pressure to placate Beijing. Yet, 18 months after the campaign began, the cost to the Australian economy appeared modest. Total merchandise exports to China in 2020 fell by just 2% compared to 2019, in part due to booming trade in non-sanctioned industries like iron ore (Rajah, Citation2021). More importantly, despite losing access to the Chinese market, many sanctioned industries saw the annualized net value of their global exports increase. Limited economic impacts muted the political pressure on Canberra to resolve the dispute, and the government stood firm on all of the policy matters that underpinned Beijing’s grievances.

So what went wrong with China’s sanctions? How and why the economic impact came to be so limited so quickly is puzzling. Sanctions targeted Australian export-oriented industries for which the Chinese market was both highly valuable and a key source of total international demand. Many affected industries sent more than 50% of their exports to China prior to disruption, and scholarship on economic sanctions suggests that such high levels of trade with a single market should have rendered them likely to sustain significant costs when faced by sudden disruption (Drury, Citation1998; Shambaugh, Citation1996). The literature on power and economic interdependence qualifies that proposition, highlighting that what should have ultimately mattered was the availability and costliness of alternatives (Keohane & Nye, Citation1977; Peterson, Citation2014; Wagner, Citation1988). But what do those alternatives look like in the short-medium term for economic actors facing import sanctions? And under what conditions will they be viable?

We argue that the answer to those questions is best uncovered through a detailed examination of the way that markets autonomously adjust in the event of government interventions that distort free economic exchange. Although scholars acknowledge the importance of market structures and dynamics in determining the impact of trade sanctions and other forms of economic coercion (Hirschman, Citation1945; Peksen & Peterson, Citation2016; Rowe, Citation2001), few studies investigate the precise mechanisms through which this occurs or how specific features of different economic industries or products affect that mediating process. Recent research, however, is demonstrating that detailed examination of sector-specific evidence from different markets can provide valuable insights into the microfoundations of coercive vulnerability in the economic domain (Gholz & Hughes, Citation2021; Gjesvik, Citation2022; Hughes & Long, Citation2015; Lim, Ferguson & Bishop, Citation2020).

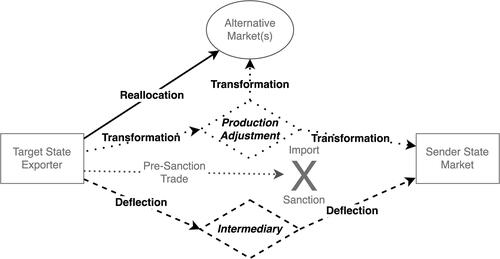

This article advances that literature in two ways. First, by theorizing the specific process of responding to unilateral trade sanctions from the perspective of export-oriented industries in a ‘target’ state that lose access to the sanctioning (‘sender’) state’s market—the challenge created by many contemporary Chinese sanctions.Footnote2 Second, by explicitly detailing the mechanisms through which market adjustments can mediate the quantum of losses initially determined by a target industry’s baseline dependence on the sender’s market. We anchor the process in the decision-making of a firm that is experiencing a ‘demand shock’ due to sender state sanctions and looking to employ strategies to mitigate its losses. We argue that losses can be diminished by three mechanisms—trade reallocation (selling sanctioned products to alternative international or domestic markets), trade deflection (circumventing sanctions via intermediaries) and product transformation (altering production processes to produce and sell different products or similar products not covered by sanctions)—and explore the conditions under which these forms of adjustment are more or less viable, depending on differences in market dynamics across products and industries.

Our research design leverages the Australian case toward two theory-building objectives. First, as a plausibility probe (Eckstein, Citation1975) to establish the validity of our model and begin to specify scope conditions for when each mechanism is viable, and second as a heuristic case study (George & Bennett, Citation2005) to refine the model further by inductively identifying new variables, mechanisms and hypotheses. Our empirical discussion is drawn from a comprehensive analysis of seven affected agricultural commodities (barley, beef, wine, timber logs, lobster, cotton and forages) and two mineral commodities (coal, copper ores and concentrates) contained in an accompanying supplementary appendix, in which we identify the mechanism(s) through which each industry adjusted, how adjustments mediated the impacts of disruption, and how the different market dynamics of each product and their respective industries conditioned those adjustments.

The article offers several contributions that are significant for both research and policy. Empirically, drawing on and triangulating industry-level trade data, media reporting, and interviews with representatives from different Australian export sectors, we offer the first detailed scholarly account of one of the most important contemporary case studies of Chinese economic power. Theoretically, we present a model of how market dynamics and adjustments to exogenous shocks may mediate the impact of unilateral import sanctions.Footnote3 Drawing on the economics and international trade law literatures on how firms adapt to traditional trade barriers, and extending ideas from extant international political economy research on how market dynamics condition the coercive potential of ‘supply shocks’—such as oil embargoes (Gholz & Press, Citation2010; Hughes & Long, Citation2015) or China’s restrictions on rare earth element exports (Gholz & Hughes, Citation2021; Vekasi, Citation2019)—to the new domain of ‘demand shocks’, we identify and illustrate key mechanisms of market adjustment, and refine existing theories of how market dynamics condition the impact of economic sanctions. We also illustrate the unique role that weather patterns and price movements in global markets may play during sanctions episodes that disrupt trade in agricultural and mineral commodities. For policymakers, our finding that market adjustments significantly mediated the impact of Chinese sanctions, even where ex ante market structures appeared conducive to imposing high costs on Australian exporters, is an up-to-date affirmation of the complexity of compelling targets to change their behaviour with economic sanctions alone.

The following section reviews the literature on the relationship between market dynamics and the ability of states to impose costs with economic sanctions. The third section outlines a simple theoretical model of how market dynamics may mediate the impact of import sanctions via the adjustment mechanisms of reallocation, deflection and transformation. The section following that explains our research design, methodology and the role of the appendix. The fifth section probes the plausibility of our theoretical framework using the Australian case, and then the final section leverages the case heuristically to refine and expand our model, before concluding with a discussion of what our findings suggest for both policy and future research.

Market dynamics and the economic impact of import sanctions

Economic sanctions are deliberate, government-directed measures—or threats thereof—that disrupt ordinary economic exchange between a sender state and target state. They seek to limit transactions between private and/or public actors from each economy.Footnote4 While sanctions can be used to pursue a variety of different objectives (Baldwin, Citation1985; Barber, Citation1979), research overwhelmingly concentrates on their use for the purpose of imposing costs to compel target governments to change their behaviour.

Since the late 1990s, a substantial body of literature has investigated the conditions under which sanctions are effective.Footnote5 While researchers identify a variety of different causal mechanisms and variables that bear upon when and how sanctions work (Biersteker, Eckert, & Tourinho, Citation2016; Blanchard & Ripsman, Citation2013; Solingen, Citation2012), models typically hinge on the imposition of large costs, which appear to be robustly correlated with successful sanctioning outcomes (Akoto, Peterson & Thies, Citation2020; Allen, Citation2005; Bapat et al., Citation2013; Hufbauer et al., Citation2007; Lektzian & Patterson, Citation2015; Morgan, Bapat & Krustev, Citation2009). This is unsurprising given that sanctions are commonly understood to operate primarily by imposing economic losses that are more politically costly for a government than accommodating a sender’s demands (Kirshner, Citation1997). Hence, the anticipated or actual economic cost of sanctions has been described as the “single most significant predictor of their coercive impact” (Allen et al., Citation2020, p. 459).

What determines costs when a sender state imposes an import sanction? If target industries are denied access to an important export market, the maximum potential economic cost is the entire value of that lost trade. Such an aggregated measure provides a straightforward baseline, which is a function of the monetary value of total exports and the ex ante percentage of that trade which was directed to the sender state’s market. However, trade is not static. As the foundational scholarship on the sources of power and vulnerability in dyadic relationships of economic interdependence emphasizes, liability to sustain costs is contingent not on the extent of trade between economic actors, but on their relative ability to adjust to the loss of a trade relationship (Hirschman, Citation1945; Keohane & Nye, Citation1977). Such adjustment turns on the availability and costliness of alternatives; if firms can, for example, redirect exports to third markets, the true ‘exit cost’ may be substantially lower than the baseline (Peterson, Citation2014).

While these theoretical insights are well established, researchers have devoted little attention to the specific conditions under and mechanisms through which exporters faced with import sanctions are able to make adjustments to limit their losses. Scholarship on economic coercion and the weaponization of resource supply shocks, however, suggests that the central determinant of adjustment to economic sanctions is the market dynamics of affected products and industries. Existing research focuses on such dynamics in three areas. The first is at a global level, particularly the composition of international supply and demand. Whether a sender can impose high costs by cutting off exports that are valuable to a target (such as energy inputs like oil or gas) depends on the structure of global supply—if the sender is not a major supplier, the target will be able to blunt the impact of any sanction by switching to other sources (Hughes & Long, Citation2015; Stegen, Citation2011). Conversely, where the sender is imposing an import sanction, the impact will largely turn on the structure of global demand. If the sender (or coalition of senders)Footnote6 dominate global consumption of a sanctioned product, there are unlikely to be many residual markets to receive the target’s redirected exports (Gholz & Hughes, Citation2021). By contrast, if demand exists in many third markets, adjustment may be relatively seamless.

A second body of literature points to market dynamics within the sender’s economy.Footnote7 A sender’s decision to impose sanctions has disruptive effects for firms and individuals in its home market, who may be apolitical and unwilling to absorb costs to support their government in achieving its policy objectives vis-à-vis the target (Bapat & Kwon, Citation2015). Where demand for continued trade with a target industry is inelastic, trade may continue to flow due to the ‘sanctions busting’ initiatives of opportunistic private actors (Drezner, Citation2000; Morgan & Bapat, Citation2003). If exporters in the sender state are banned from sending their products to a lucrative market, they may seek to circumvent restrictions rather than receive less for exports redirected to new markets or have to forego trade (and profit) entirely (Barry & Kleinberg, Citation2015; Kaempfer & Lowenberg, Citation1999; Weber & Stępień, Citation2020). Where the sender restricts imports, sanctions may not eliminate consumer demand, and this may encourage economic actors to secure trade from target industries indirectly, such as via smuggling or transshipment through third markets (Early, Citation2015). Existing literature suggests such activity is more likely when sender governments are unable to monitor and enforce sanctions regimes effectively (Bapat & Kwon, Citation2015; Early & Peterson, Citation2021; Early & Preble, Citation2020). How such market dynamics mediate the effectiveness of Chinese import sanctions, however, has received limited attention.Footnote8

Finally, research also underlines the importance of market dynamics in the target economy. In the case of target exporters faced with import sanctions, scholars expect that the ease or difficulty of adjustment will be influenced by an industry’s ‘mobility of resources’ (Hirschman, Citation1945, 28) or what Crescenzi (Citation2005) terms ‘asset specificity’. Losses may be avoided if capital, labor and other assets can be quickly adapted and diverted to alternative productive purposes, but exacerbated if left idle. This might be the case where, for example, an industry has made significant investments in facilitating bilateral trade—such as in sender-specific production processes—on the premise that normal patterns of trade would continue. However, while scholars have acknowledged the possibility that industry and product-specific sunk costs and characteristics will affect the capacity of target industries to adjust,Footnote9 how such microfoundations shape import sanction episodes is yet to be explored in detail.

In sum, extant research suggests that market adjustments can mediate the impact of import sanctions, and that whether and how such adjustments take place will depend on discrete market dynamics across different industries and products. While the relevance of three broad categories of factors—dynamics in global markets, the sender state, and the target state—is broadly understood, few studies inquire how each might affect target industries during import sanction episodes, nor specify the mechanisms linking them to different types of market adjustment. We seek to fill these gaps in the research program by constructing a single framework for studying the relationship between market dynamics and firm-led adjustments in the specific context where a sender state unilaterally imposes import sanctions.

How target exporters adjust to unilateral import sanctions

In this section we synthesize and build on existing theoretical insights in order to sketch a model of adjustment to import sanctions from the perspective of export-oriented firms in a target state. For such actors, import sanctions generate an exogenous demand shock constituted by the loss of some percentage of their export market. We follow the sanctions literature in assuming that preexisting trade ties reflect the lowest cost (and highest benefit) arrangement for an exporter and their trade partners (Early, Citation2015; McLean & Whang, Citation2010; Peterson, Citation2014). The potential losses of target firms and their respective industries are bounded by the value of exports to the sender state market. In an extreme scenario where, for example, the exports are perishable goods and no other markets can be found, losses could approach this entire amount. However, like with any exogenous market shock, sanctions will prompt economic actors to adjust their behavior in profit-maximizing ways. The relative ability of different actors to adjust will turn on the market dynamics of their industry and product(s).

Conceptually, losses can be stemmed via at least three adjustment mechanisms. The first, which is well established, is to sell sanctioned products to alternative markets (whether international or domestic). We label this trade reallocation, because the exporter is simply shifting (‘reallocating’) its trade patterns. The second is evading the sanctions and continuing to sell the sanctioned product into the sender’s market via third party intermediaries, which we label trade deflection (a term drawn from research on preferential trade agreements).Footnote10 The third method is for target exporters to adjust production processes in order to produce and export similar products not covered by sanctions, or to produce and export entirely different products altogether, whether to the sender state or third markets. We label this mechanism product transformation.Footnote11 Whether reallocation, deflection or transformation (or a combination) represent the most effective loss-mitigation strategy will depend on a number of market dynamics and the time horizons over which adjustments are pursued.

Reallocation involves selling the sanctioned goods elsewhere. Existing sanctions research on the role of market dynamics at the global level establishes that the composition of international supply and demand shapes whether viable alternatives exist (Gholz & Hughes, Citation2021). Consistent with the expectations of the general equilibrium theory of trade (Dixit & Norman, Citation1980), both sides of the market matter. If the sender’s market represents a large proportion of global demand, the volume of trade that can be absorbed by alternative markets for target exporters can be expected to be limited, and vice versa.Footnote12 On the supply side, if global supply is relatively tight (inelastic), then as the sender replaces imports from the target with those sourced elsewhere, target exporters can reallocate by filling any voids created in third markets. However, if other exporters can scale up production quickly to meet new sources of demand, target exporters may struggle to find third markets. This will be particularly true if target exporters are not internationally competitive. Even where alternative markets exist, the efficacy of reallocation will also be conditioned by the transaction costs and changed transport costs of switching over (Williamson, Citation1975). If the sanctioned product is homogenous and heavily traded on global markets, reallocation could be expected to involve relatively less friction. Costs would rise as the product becomes more differentiated and exporters must negotiate variation in national regulations and preferences, as well as construct the necessary bilateral infrastructure to facilitate selling into alternative markets (Wittwer & Anderson, Citation2021).

From the target’s perspective, trade deflection actually resembles trade reallocation, as in both cases exporters sell to an alternative buyer. The difference is the product’s final destination. In deflection, the immediate buyers act as intermediaries, re-exporting into the sender market (whether through formal channels, after relabeling or other efforts to obscure the country of origin, or informally via smuggling). Its feasibility depends upon on how demand conditions inside the sender’s market interact with global supply dynamics, and the sender’s capacity or willingness to enforce sanctions against different products.

When their government sanctions the target, sender importers must either source alternatives or go without the product entirely. As the literature on the role of market dynamics in the sender economy highlights, if demand inside the sender state for the sanctioned product is relatively inelastic, end-users (whether firms using the imports as production inputs, or retail consumers) may be willing to pay a premium to acquire it if they cannot readily source alternatives.Footnote13 Where such conditions prevail, private actors have incentives to ‘bust’ the sanction—facilitating the passage of target state products via transshipment through third markets,Footnote14 or arranging for goods to be smuggled in.Footnote15 Once deflection is in motion, the primary obstacle is the sender state’s capacity and willingness to detect and enforce sanctions violations (Early & Preble, Citation2020). This will differ from product to product. For example, the country-of-origin of homogenous raw materials may be harder for a customs officer to identify than that of highly processed, packaged and labeled consumer goods.

The viability of product transformation turns on supply conditions highlighted by the literature that emphasizes market dynamics inside the target state. Given this adjustment mechanism involves economic actors physically changing what is being produced for sale, its feasibility depends on a variety of cost considerations that are broadly determined by what we term ‘product adjacency’. We highlight two types. The first—building on the insights of Hirschman (Citation1945) and Crescenzi (Citation2005)—is where entirely different products are produced without a major reorganization of production because production inputs are relatively substitutable. A simple example is a farmer planting a different crop or changing species of livestock (for which land and farming equipment is similarly productive). The second involves retaining existing production processes but building upon them, either by processing raw materials into a downstream intermediate input or making minor modifications to a product (such as including a low-cost additive) so that it can be passed off as falling under a different product category that the sender has not sanctioned.Footnote16

The model’s three adjustment mechanisms—reallocation, deflection and transformation ()—offer an analytical template for studying the mediating effect of market dynamics in the China-Australia sanctions episode. Moreover, we have posited broad theoretical expectations about the conditions under which each mechanism will enable exporters to offset potential losses. For reallocation, we highlight three market dynamics: the sender’s concentration in global demand, the elasticity of global supply and the homogeneity of the sanctioned product (given associated implications for transaction costs). For deflection, we emphasize the target’s concentration in global supply, the elasticity of sender firms’ demand and the sender’s enforcement capacity. Finally, transformation turns on the substitutability of target firms’ production inputs and global demand for adjacent products.

Importantly, even where a mechanism operates, it will not mean adjustment is costless. Sanctions will almost always impose meaningful losses on target state exporters compared to the counterfactual where no disruption occurs. Where conditions that facilitate adjustment are present, success at lowering costs will vary across industries and between firms within industries. Measuring the quantum of those losses with any precision requires general equilibrium modeling which is beyond the scope of this paper. Our goal is instead to illustrate pathways for loss mitigation and investigate the conditions under which they are available.

Research design, methodology and the appendix

We employ a case study research design conducted to serve two theory-building objectives (George & Bennett, Citation2005). The first is a plausibility probe of our model of market adjustments to the demand shock caused by unilateral import sanctions across multiple industries. Second, given this type of sanctions case is relatively understudied, the other is the heuristic objective of identifying new variables, hypotheses and causal mechanisms that illuminate how market dynamics and adjustments mediate sanction impacts.

The China-Australia case is appropriate for at least three reasons. First, the impacts of sanctions vary widely across the affected Australian products. Second, there is also significant variation across industries and products in the market dynamics that we expect to condition the viability of the adjustment mechanisms of reallocation, deflection and transformation. As a single sanctions episode, the case allows us to exploit this variation while holding a number of background conditions constant for our theory probing and refining purposes. Finally, as the most recent and wide-ranging instance of Chinese economic coercion in world politics, the case also has intrinsic importance for our broader research objective of illuminating the conditions under which China is able to successfully exercise economic power. Detailed single case studies provide a valuable method for doing so.Footnote17

A variety of methods can be employed to examine the impact of a demand shock caused by import sanctions. The most appropriate strategy will depend on the research objective, as can be seen in early studies of the China-Australia case. One group of studies rely on macro statistical analyses to estimate the trade effects of disruption. Rajah (Citation2021) presents statistics on the value of Australian exports to illustrate trade reallocation effects in sanctioned industries. Laurenceson and Pantle (Citation2021) offer a ‘cost guide’ for a number of industries by comparing the fall in volumes of exports to China with the growth in exports elsewhere, while adjusting for premium pricing. Wickes, Adams and Brown (Citation2021) focus on the extent to which exports to China were lost, and thus compare realized exports after disruptions to the counterfactual where Australian market share was stable. A second group of studies have sought to quantify the actual losses from trade barriers through general equilibrium trade modeling of individual industries that capture reallocation and substitution effects domestically and at a broader sectoral level. Four Australian studies have been conducted, on barley (Cao & Greenville, Citation2020), wine (Gleeson, Addai & Cao, Citation2021; Wittwer & Anderson, Citation2021) and coal (Giesecke, Tran & Waschik, Citation2021), respectively.

Our objective is not to quantify with precision the sanctions’ actual cost, but illustrate and probe the plausibility of our theorized mechanisms of adjustment. To do so we combine both quantitative and qualitative approaches. To capture the volume of reallocated and deflected trade, we quantify variation in the value of Australian exports to China versus Australia’s net global exports, cross-referencing Australian export statistics with Chinese import statistics (see Appendix 2.2).Footnote18 Our first measure of impact compares a six-month period after the sanction for each industry with the same six-month period in the previous year. As a robustness check designed to minimize inter-seasonal variation across the calendar year, a second measure defines the sanction month for each industry (e.g. May 2020 for barley) and then compares the values from the month falling six months before the sanction (November 2019) with the same month six months after the sanction (November 2020). While results of the two methods generally align, notable discrepancies are explained in the analyses. Finally, to understand the mechanisms of reallocation and transformation for differentiated and substitutable products, our analysis incorporates more detailed data on product characteristics and other market dynamics, including descriptions collected from stakeholders in the affected industries. The triangulation of these diverse and independent sources offers a rich and robust account of market adjustments during the sanctions episode.

Conducting such mixed methods analysis for nine separate industries requires a significant amount of descriptive and analytical work. Accordingly, and to maximize research transparency and data accessibility of sources (Elman & Kapiszewski, Citation2014), we document the complete analysis in a supplementary appendix. Taking each industry in turn, the appendix begins by specifying a baseline potential for losses based on the value of exports and the percentage of trade destined for China prior to the disruption. Second, it describes the form that the sanction(s) took. Third, it calculates the two measures of impact outlined above, coupling this with descriptive evidence of whether and how market adjustments occurred. Each individual industry analysis concludes with a discussion of the overall trade effects.

The empirical analysis in the following sections leverages and actively references the case study presented in the appendix toward the two theory-building research objectives. The next section introduces the case, offers some general observations regarding the impact of the entire sanctions campaign, and then conducts the plausibility probe of the three theorized adjustment mechanisms. In the final section, we then leverage the case heuristically to expand and refine the model, and offer some concluding observations.

Case study: Chinese import sanctions on Australian exports, 2020–2021

Political relations between China and Australia had become increasingly fraught prior to 2020 due to a growing list of disagreements on issues ranging from Canberra’s exclusion of Huawei from its 5G network to Beijing’s conduct in the South China Sea (Kassam, Citation2020). Yet political tensions had not seemingly affected the long-growing and mutually beneficial trading relationship between the two highly complementary economies. That changed in April 2020, with many marking the turning point as the Australian government’s public call for an independent, international investigation into the origins of the COVID-19 outbreak. Shortly after the announcement, China’s Ambassador to Australia warned that Chinese consumers might retaliate by boycotting Australian exports, including beef, barley and wine. In response, the Australian Foreign Minister accused Beijing of “economic coercion”.Footnote19 Beef and barley exporters began experiencing disruptions to their China trade in May. Over the following months, disruption extended to a variety of other industries, including coal, cotton, wine, lobster, timber logs, copper ores and concentrates, and forages.Footnote20 Restrictions on these products remained in place at the time of writing in late 2021, with the exception of coal, which Chinese actors resumed importing in November of that year.

Consistent with its past approach to employing economic sanctions, the Chinese government never explicitly acknowledged that the trade barriers faced by Australian exporters were punishments levied for political purposes. Footnote21 The sanctions were not imposed through explicit sanctions legislation, but rather via ‘informal’—and accordingly largely ‘plausibly deniable’—means (see Lim & Ferguson, Citation2021; Ferguson, Citation2022). Some barriers, such as the cancellation of export licenses and the imposition of anti-dumping duties, were imposed by Chinese authorities due to alleged violations of technical international trade rules by Australian exporters. Others, such as import bans that were reportedly conveyed to Chinese economic actors privately, were denied to be in place at all.Footnote22 For our purpose of studying how market adjustments mediated the losses stemming from import sanctions, the fact that Beijing denied the existence of sanctions is beside the point, as is the fact that there is uncertainty about Beijing’s precise objectives.Footnote23 What is important, as Gholz and Hughes (Citation2021, 628 footnote 12) also note of the China-Japan rare earth elements episode, is that trade was disrupted, and that target exporters believed that they were being sanctioned.Footnote24

Australian exports to China prior to the dispute

China has been Australia’s most important export market for decades. Comparative economic strengths and deep complementarities saw bilateral trade grow continuously after the Chinese market opened up in 1978, leading China to become Australia’s largest two-way trading partner in 2006 and the conclusion of wide-ranging free trade agreement in 2015. The scale and depth of trade continued to expand over the following years, with Australia supplying increasing quantities of agricultural and resource commodity inputs to fuel China’s rapid industrial development, as well a growing number of final goods and services (particularly education and tourism) to China’s increasingly affluent consumer market.

Import sanctions primarily targeted Australian commodity exports. Prior to the episode, Australian agricultural, forestry and fisheries exports to China had grown rapidly to reach US$11.7bn in 2019, representing 32% of the sector’s total exports. This accounted for 11% of the total value of Australian merchandise exports to China (US$103.6bn).Footnote25 Exports of the seven sanctioned agricultural industries represented a total value of US$5.7bn in 2019. Australian resource commodity exports to China had also been growing. Iron ore (US$43.9bn), coal (US$11.6bn) and liquefied natural gas (US$9.8bn) represented the highest value exports in 2019.

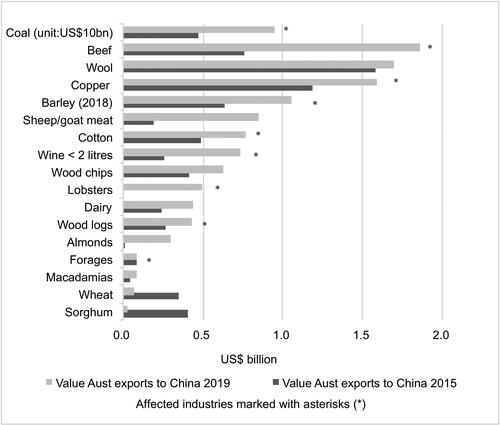

shows the top 15 Australian agricultural exports to China in 2015 and 2019, seven of which faced barriers in 2020-21. Most had undergone high growth since 2015, and all but two had a trade value greater than US$0.5bn in 2019. Also included in are two Australian resource commodities that experienced disruption during the dispute: coal and copper. The value of coal exports is far higher than the other sanctioned commodities and is accordingly presented in units that are higher by a factor of 10. Products are presented in descending order of value, with asterisks indicating industries affected by disruption.

Figure 2. Trade value of major Australian commodity exports to China, 2015 and 2019.Footnote36

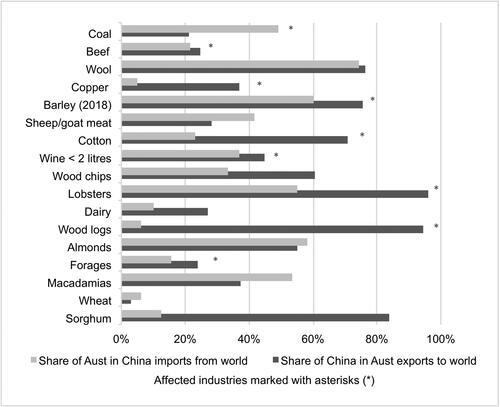

presents data on trade concentration. The data shows the high exposure of many agricultural and resource industries to China. Four of the seven agricultural industries had concentrations of more than 50% (barley, cotton, lobsters, logs). In addition, China accounted for 21% and 37% of Australian coal and copper exports, respectively in 2019.

Figure 3. Trade concentration for major Australian commodity exports to China, 2019.Footnote37

Summary observations

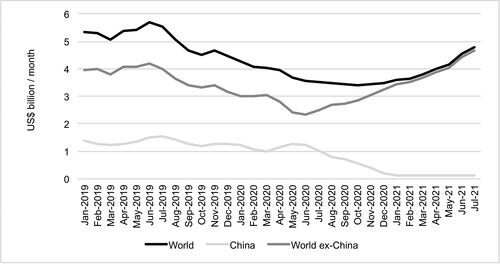

Despite exports of many industries being concentrated in the Chinese market prior to disruption, by mid-2021, the net global trade effects arising from import sanctions were more modest than many expected. Those effects are summarized in , which shows the degree to which Australian exporters in the nine industries we study fared in aggregate in response to the sanctions.Footnote26 The commencement of the campaign in May 2020 is clear, from which point exports to China gradually fell while, simultaneously, exports to the rest of the world grew. For the first six months global exports fell—continuing a trend that began in 2019—while from November 2020 exports to the world began to rise despite, by this point, exports to China falling essentially to zero. Overall, across the first 12-15 months of the sanctions campaign, it is hard to see major losses for the Australian macro economy.

Figure 4. Australian exports of nine commodities sanctioned by China 2020–21.

Source: UN Comtrade, accessed September 2021.

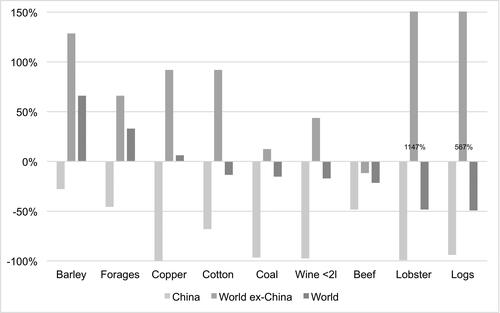

presents a snapshot of the extent of adjustment for each of the nine primary commodities that are analyzed in the appendix.Footnote27 The figure summarizes change in the export value to China, the world, and the world ex-China by comparing the six-month period after the sanction with the same six-month period in the previous year (Measure 1, as discussed in the methods section above and at Appendix 2.2).

Figure 5. Summary of changes in export values after sanction imposition (Measure 1).Footnote28,Footnote29,Footnote30,Footnote31,Footnote32,Footnote33,Footnote34,Footnote35,Footnote36,Footnote37,Footnote38

Source: UN Comtrade, accessed September, 2021 and author calculations

While there was significant variation in the trade effects, these basic indicators suggest most industries were able to adjust to the sanctions relatively quickly. However, it should not be inferred that the adjustment process was costless, especially compared to the counterfactual where sanctions were not imposed. As described below and in depth in the empirical appendix, there were opportunity costs in losing particular profitable aspects of the Chinese market, including markets that took large orders of malting, food and feed barley (Appendix 3.3(c)[2]), high value wine (Appendix 3.9(a)), small diameter pine logs (Appendix 3.8(a)) and a full range of low- and high-value beef cuts (Appendix 3.6(a)). Losing the Chinese market also entailed higher transaction costs in selling to a larger number of smaller markets, especially for small companies. Nevertheless, the evidence of adjustment across all the industries suggests losses that were a fraction of the potential derived from the ex ante value of their China trade—albeit to varying extents. We turn now to the plausibility probe.

Reallocation

Reallocation—redirecting products to alternative markets—was the most important adjustment mechanism and the only one pursued by every industry. This may in part be explained by the relatively short time scale over which our analysis was conducted.Footnote28 When hit by a sanction, reallocation may be the only viable immediate or short-term option because the generally more complex changes to production, processing and logistics required by the other adjustment mechanisms take greater time to organize.

We find that the efficacy of reallocation was indeed plausibly conditioned by the three factors posited in our model. Our first expectation was that reallocation would be less viable where the sender dominated global demand for imports. For most products that reallocated effectively, China represented less than a quarter of total international demand and a variety of other sizeable markets existed. However, in cases where China was dominant, only limited reallocation occurred. This was particularly true of timber logs, for which China represented approximately half of total world imports (and dwarfed the next largest markets, see Appendix 3.8(c)[1]), and of lobster, for which China represented a staggering 82% of world imports (Appendix 3.7(c)[1]).

The second factor—the tightness of global supply—also enabled reallocation. Where short-term global supply was relatively inelastic, the decision of third country exporters to exploit new demand in China’s market (arising from Australia’s exclusion) opened up gaps in other markets they had previously supplied, which Australian exporters were then able to fill.Footnote29 The clearest example of this was copper ores and concentrates, for which supply was especially tight due to the limited number of new deposits being discovered or coming online prior to and during the sanctions episode (Appendix 3.1(c)). As China increasingly drew on Chilean exports, Australian exporters redirected shipments to markets in Europe, South Korea and especially Japan. Similar dynamics occurred for products including barley (opportunities opened in markets like Thailand, Mexico and Saudi Arabia: Appendix 3.3(c)[2]), cotton (new opportunities in Bangladesh, Vietnam and Indonesia: Appendix 3.2(c)[2]), and coal (new opportunities in India, Japan and South Korea: Appendix 3.4(c)).

Our third expectation concerned the transaction costs and altered transportation costs of redirecting trade in certain products. We anticipated that reallocation would become less viable as these costs increased. The magnitude of transaction costs turned on how differentiated products were. In general, the more homogenous the product, the more seamless reallocation into alternative markets appeared to be.Footnote30 This was especially true for products like copper, cotton, and coal, which are all traded in bulk in deep international commodity markets. As observed by the managing director of a leading Australian copper exporter which had sent upwards of 90% of their trade to China prior to disruption (Sandfire Resources), “[The company] maintained uninterrupted copper concentrate shipments to a diverse range of international customers … This reflects both the deep and liquid nature of the global market for copper concentrates and the high quality and sought-after nature of our concentrates, giving us considerable flexibility” (Appendix 3.1(d)). By contrast, as products became more heterogeneous, reallocation involved greater friction and thus cost. The clearest example of this was wine, which is a highly differentiated consumer product distinguished by highly variable factors such as taste and brand value, and which needs to be carefully marketed to develop demand (Appendix 3.9(c)[1]). For beef, friction arose from the need to service smaller orders of different cuts to a larger number of countries (Appendix 3.6(c)[1]). All of these factors increased transaction costs, and hence limited the availability of and the extent of relief provided by, reallocation. Transportation costs also created friction for some industries, such as forages, which were difficult to reallocate to geographically distant markets because of their low unit value and bulk (Appendix 3.5(c)[2]).

Deflection

Deflection—circumventing import sanctions to continue trade with the sender via intermediaries—benefited a number of Australian industries. We expected that deflection would be less viable where sender demand could be satisfied by alternative suppliers, and where products were susceptible to effective sanction monitoring and enforcement. Both of these factors appeared to play a meaningful role.

The most significant instance of deflection was in the lobster trade via Hong Kong. This was likely facilitated by strong demand in China for a highly differentiated product for which no competitive alternatives were readily available from third markets. Prior to disruption, 96% of Australian lobster exports went to China, where it was highly sought after. As one seafood trader commented: “Mainland consumers are so used to [Australian lobster’s] taste that the Chinese market demand is still huge, even though direct imports have been banned” (Appendix 3.7(c)[3]). Accordingly, while (formal) exports to China declined by 100% over the six months after the sanction was imposed, total global exports to the rest of the world skyrocketed (from low baselines) by over 1000%. While a small amount of this reflected reallocation, the bulk was deflected through Hong Kong, significantly mitigating the impact on the industry. There is limited evidence of re-exporting in official trade statistics, which suggests the majority of sanction busting activity was undertaken by smugglers who shuttled live lobster either by truck (across the Hong Kong-Shenzen border) or sea (via speedboats or fishing vessels that regularly cross between Hong Kong and China’s southern coastal provinces: see Appendix 3.7(c)[2]). The lobster experience can be contrasted with industries that had less success. Wine saw some deflection but in much lower volumes, likely because Chinese consumer demand was relatively more elastic due to the existence of a variety of accessible alternatives from markets like Chile, France and Italy (Appendix 3.9(c)[3]). An even stronger contrast is with timber logs, for which there was no evidence of deflection, because the product could be so readily substituted (Appendix 3.8(c)[2]).

Some deflection via intermediaries in Chinese special economic zones briefly occurred for barley, but this was stamped out relatively quickly by Chinese authorities (Appendix 3.3(c)[1]). By contrast, the relatively porous sanction on beef facilitated deflection via a novel pathway. Disruption for the industry came in the form of a number of plants losing their export licenses due to alleged regulatory issues (Appendix 3.6(b)). Our expectation was that deflection would occur via international intermediaries (either smuggling or re-exporting), however beef exporters exploited the fact that some Australian abattoirs still retained licenses, using them as domestic intermediaries to re-route their products to China legally. This hole in sanctions monitoring and enforcement is a possible drawback arising from sanctioning in a way that affords ‘plausible deniability’—the need for a Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT) violation to justify license suspensions potentially limited the scope for Chinese authorities to disrupt Australian exports.Footnote31

Transformation

Finally, some exporters also adjusted by transforming products or production processes.Footnote32 It was anticipated that this form of adjustment would be possible where sanctioned products could be processed to fit an adjacent product category without a major reorganization of production, or where production inputs were sufficiently substitutable to enable production of alternative products.

Adjacent product categories only proved valuable if they had meaningful demand or value in the sender’s or other markets. This was partially true for the timber industry, which was offered some respite by the fact that wood chips faced no barriers in the Chinese market. Exporters accordingly chipped (sanctioned) timber logs and sold the processed product into China, with the value of wood chip exports to the market increasing by 270% over the sanction year (Appendix 3.8(c)). For other industries, modifying the form or packaging of products was less viable. Wine only faced barriers in bottled form, so exporters had the option to export to China in bulk form (typically done in 24,000 liter ‘flexitanks’), however transaction costs and quality issues associated with making the switch meant this only occurred at low levels. Some exporters also expressed concern that shifting to the (lower quality) bulk market might have reputational consequences that could erode future price margins for Australian bottled wine: “This will potentially destroy Australia’s fine wine image in the one market where it has avoided the stigma of being a dominantly industrial producer of branded commodity wine” (Appendix 3.9(c)[4]). Nevertheless, the ability to export in bulk form did facilitate some reallocation of lower quality wines to third markets (Appendix 3.9(c)[4]). Lobster exporters were unable to ship their wares in (unsanctioned) frozen form because there was inadequate demand—the Chinese market was for live lobster, which was overwhelmingly consumed out-of-home (Appendix 3.7(c)[3]). Processing capacity was also highlighted as a relevant constraint. For example, copper traders had limited scope to process ores into refined copper, partly because Australia’s smelters were already operating to capacity (Appendix 3.1(c)).

Most products had limited scope for short-term substitution at production level due to high, commodity-specific fixed investments.Footnote33 However, this type of transformation was viable for some farmers whose inputs, such as tractors and land, were sufficiently substitutable. Barley and forage growers were able to switch into other winter crops such as wheat and canola to minimize the impact of losing the Chinese market, however this did not occur at large scales because of limited price or production-side incentives to do so given the viability of reallocation (see Appendix 3.3(c)[3]; 3.5(c)[3]).

Summary

We conclude that there is strong evidence in support of the basic claims and scope conditions of the model posited in the theory section. Target state exporters facing unilateral import sanctions by a sender will try to adjust their market behavior to mitigate losses. The extent to which losses can be mitigated is potentially quite significant, especially via the reallocation mechanism provided that the sender does not dominate global demand, global supply is relatively inelastic, and the transaction and transport costs of directing exports to alternate markets are not prohibitive. Similarly, deflection and transformation offer loss mitigation pathways, albeit generally not as large as reallocation in the short-term. Overall, the economic impact of sanctions has the potential to be significantly diminished by market adjustment processes.

Implications

Heuristic contributions

In this final section we utilize the case study heuristically, drawing inductive inferences that seek to refine and expand our model. We begin by observing that those industries that offset losses most effectively were all examples where reallocation to third markets was the primary (or, if highly effective, only) mechanism of adjustment. As observed above, it was also the only mechanism that was pursued by every industry. This suggests that the mechanisms can be ordered in a hierarchy, with reallocation (where possible) representing the optimal method for adjusting to disruption in the short-term, and deflection and transformation reflecting subsidiary forms of adjustment.

The case also revealed several novel variables and mechanisms that appeared to condition market adjustments, and possible new hypotheses, that we did not consider in the theory section, nor which appear to have received attention elsewhere. The first mechanism is a unique form of transformation enabled by what we tentatively call ‘intertemporal substitutability’—the ability to pivot from ‘trade’ to ‘investment’ with a product for some period of time, which appears to be available for products that are simultaneously consumption goods and capital goods. It was witnessed in the beef industry (with farmers rebuilding herds: Appendix 3.6(c)[3]), the timber log sector (with producers delaying thinning—leaving trees in the ground longer, which may result in thicker and potentially more valuable logs: Appendix 3.8(c)[4]), and the wine industry (with actors putting stocks into storage, where some premium wines may increase in value over time: Appendix 3.9(c)[4]). The extent to which this form of transformation offsets costs is unclear, but may be meaningful if exporters are able to ‘wait out’ sanctions or the process of cultivating new markets, before selling the (enhanced) products at better prices. More broadly, one theoretical implication of these observations is that the extent to which an industry is vulnerable to import sanctions may depend on how the product(s) it exports fare(s) in inventory. It could be hypothesized that such vulnerability varies along a spectrum, with products that have short shelf lives and quickly lose value on one end, those amenable to inventory (but not productive during storage) in the middle, and those that benefit from intertemporal substitutability (i.e. potential to gain value when not traded) on the other end.

Another variable the case highlights is the possibility that other exogenous market shocks may occur during sanctions episodes. One example is weather patterns, which are an important supply-side dynamic in agricultural markets. Another is large swings in global commodity prices. The Australian barley example offers heuristic insight here. Despite China representing well over half Australia’s barley export market, a record harvest (aided by good weather) and strong global prices saw exports increase dramatically over the baseline used to estimate potential losses (Appendix 3.3(d)). Generally buoyant commodity prices throughout the period (World Bank, Citation2021) appear to have facilitated the adjustment of other industries, including copper, coal, cotton, beef and timber logs. While it is strongly intuitive that positive shocks mitigate the damage sanctions can cause, and that negative shocks can exacerbate it, the nature and magnitude of shocks—including the extent to which global supply or demand (and thus prices) fluctuate from year to year—could dwarf the impacts of unilateral sanctions. Importantly, we still do not observe the counterfactual—Australian barley farmers would likely have done even better had exports to China not been disrupted. Nevertheless, exogenous market shocks can strongly mediate the availability of adjustment mechanisms and thus ultimately the effectiveness of unilateral sanctions in imposing costs on targets. The role of these dynamics during sanctions episodes may be a fruitful area for future research.

Conclusions

Stepping back, three broad lessons about economic power and vulnerability emerge from this case. The first relates to the centrality of market dynamics and adjustments as mediating variables that condition the impact of economic sanctions. As the Australian Treasurer Josh Frydenberg noted in September 2021, “In many cases, trade actions simply see a reordering of global trade flows”.Footnote34 Previous research overwhelmingly explores that dynamic in sanctions episodes that involve ‘supply shocks’, where sender states deny targets access to valuable inputs such as energy resources. In this paper, we extended those insights to an instance where economic coercion involved the sender denying a target access to an important export market, requiring traders to navigate a ‘demand shock’. In doing so, we not only provided new evidence that validates existing understandings of how broad market dynamics—such as the structure of global supply and demand—affect the viability of adjustments, but also highlighted the important role of additional factors such as the specific characteristics of particular products. Sector- and product-specific dynamics are central to any explanation of economic vulnerability, and should be a focus of future research on the possibilities and limitations of economic coercion. While our framework for studying adjustment was premised on the extreme situation where target firms are forcibly excluded from a market, it may equally offer insights for research on how firms who retain the option to trade respond to political conflict or risks in key markets (see, e.g., Davis & Meunier, Citation2011; Lin, Hu & Fuchs, Citation2019). Building on this paper, future studies in that stream could consider how and to what extent scope for market adjustment operates as an explanatory variable shaping the decision of firms to exit or remain in politically volatile export markets.

The first lesson, and the evidence of relatively successful adjustments during the Australian case generally, also have implications for new research on the concept of ‘weaponized interdependence’ (Farrell & Newman, Citation2019).Footnote35 Qualifying earlier liberal claims that economic globalization has led to fragmented networks of interdependence in which coercive strategies are harder to employ (see, e.g., Keohane & Nye, Citation2012), Farrell and Newman highlight that the business-led drive for efficiencies and increasing returns to scale in many sectors has in fact created highly centralized, asymmetric network structures in which ‘privileged states’ that control ‘hubs’ may have more—rather than less—coercive power. However, their account is unclear about why the forces of globalization have produced such structures in some sectors (such as the internet and financial communications) but not others. Our findings, especially regarding how decentralized global commodity markets facilitated adjustment, appear more consistent with standard liberal accounts of globalization tempering economic coercion. Many markets—such as those for bulk energy, mineral and agricultural products—do not exhibit network asymmetries, suggesting the need for narrower boundary conditions on where and why the conditions necessary for weaponized interdependence will arise.

A second lesson, flowing from the first, concerns the relationship between the broad structure of a country’s trade profile and vulnerability. The underlying complementarities of the Sino-Australian economic relationship meant that Australian exports were highly concentrated on China, which was suggestive of vulnerability. However, those complementarities rested upon a particular market structure, which for Australia largely meant exposure in the raw commodity-based exports of widely traded mineral, energy and agricultural products. Compared to other national export profiles, Australia’s may have been less exposed because many dominant products had characteristics that facilitated relatively frictionless reallocation, and further because in some instances where sanctions were not applied—such as iron ore and wool—there were no realistic substitutes to Australian supply. Moreover, prior to this episode Australia had reinforced its natural resource endowments with efficient production and logistics systems through a mix of deregulation and decades of exposure to strong international competition, leaving many exporters in a relatively good position to adjust to disruption. One important avenue for future research will be to compare the adjustment experience of Australian firms with that of exporters in states with different trading profiles. In particular, our framework raises interesting questions for economies that predominantly export manufactured intermediate inputs or elaborately transformed commodities. Compared to raw commodities, such differentiated products may have narrower and less accessible global demand (complicating reallocation), and involve higher fixed costs and less substitutable production inputs (making transformation less viable). At the same time, highly differentiated products may be more costly for sender firms to replace, especially if they are an important input in their supply chains (suggesting a greater likelihood of deflection). Interrogation of these issues in future empirical studies may enable researchers to identify new mechanisms and place tighter scope conditions on our arguments about the ways in which market dynamics may mediate the impact of sanctions in the short-medium term.

Finally, the Australian case also highlights the difficulty of exercising economic power unilaterally. Economic sanctions overwhelmingly prove ineffective when a target has alternatives to the sender state market. Sanctioning coalitions—typically led by the United States—encountered this issue in the 20th century, leading to significant research and policy innovation regarding the design and implementation of multilateral sanctions regimes. China has so far largely eschewed the multilateral approach. While its considerable economic heft gives it real capacity to impose costs, going it alone limits Beijing’s ability to effectively remove the market entirely for a target, and this provides greater scope for the sorts of dynamics and adjustments documented in this paper to dampen the impact of its sanctions.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (1.2 MB)Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Benjamin Herscovitch, Llewelyn Hughes, William Norris, Anthea Roberts, Jeffrey Wilson and three anonymous reviewers for helpful comments and criticism. They also thank all of the industry actors who participated in interviews. Previous versions of this paper were presented at Texas A&M University’s Economic Statecraft Speaker Series on 21 September 2021 and to the Australia-China Business Council on 9 November 2021. The authors are also grateful to the participants at both events for their feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Victor A. Ferguson

Victor A. Ferguson is a PhD Candidate in the School of Politics and International Relations at the Australian National University.

Scott Waldron

Scott Waldron is an Associate Professor in the School of Agriculture and Food Sciences at the University of Queensland. He researches agricultural development, policy and trade, especially in China.

Darren J. Lim

Darren J. Lim is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Politics and International Relations at the Australian National University. His research spans the fields of international political economy and international security, with a focus on geoeconomics.

Notes

1 See, e.g., Alexandra Veroude, ‘Australia’s China Addiction Leaves it Vulnerable to Trade Spat’, Bloomberg, 14 May 2020, https://web.archive.org/web/https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-05-13/australia-s-china-addiction-leaves-it-vulnerable-to-trade-spat; Tony Walker, ‘Australia has dug itself into a hole in its relationship with China. It’s time to find a way out’, The Conversation, 14 May 2020, https://web.archive.org/web/https://theconversation.com/australia-has-dug-itself-into-a-hole-in-its-relationship-with-china-its-time-to-find-a-way-out-138525; Gerry Shih, ‘China sharply ramps up trade conflict with Australia over political grievances’, Washington Post, 27 November 2020, https://web.archive.org/web/https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/china-australia-dispute-wine-exports/2020/11/27/9da5e298-3060-11eb-9dd6-2d0179981719_story.html; Mark Thirwell, ‘Australia's trade dependency on China highlights our vulnerability’, Australian Institute of Company Directors, 1 July 2020, https://web.archive.org/web/https://aicd.companydirectors.com.au/membership/company-director-magazine/2020-back-editions/july/australias-trade-dependency-on-china-highlights-our-vulnerability; Jamie Smyth, ‘Australia: has the ‘lucky country’ run out of luck?’, Financial Times, 24 May 2020, https://web.archive.org/web/https://www.ft.com/content/73c4f0b6-d5c7-47c8-b91c-8e84343dfd85; David Uren, ‘Australia’s asymmetrical trade with China offers little room to move’, The Strategist, 10 Nov 2020, https://web.archive.org/web/https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/australias-asymmetrical-trade-with-china-offers-little-room-to-move/.

2 See, e.g., Paul Vieira, ‘Canadian Canola Gets Entangled in China Diplomatic Dispute’, Wall Street Journal, 22 March 2019, https://web.archive.org/web/https://www.wsj.com/articles/canadas-canola-growers-say-china-has-ceased-buying-their-seed-11553268082; Finbarr Birmingham, ‘Lithuanian exports nearly obliterated from China market amid Taiwan row’, South China Morning Post, 21 January 2022, https://web.archive.org/web/https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3164170/lithuanian-exports-nearly-obliterated-china-market-amid-taiwan; Thompson Chau, ‘China flexes economic muscle with ban on Taiwanese grouper’, Nikkei Asia, 15 June 2022, https://web.archive.org/web/https://asia.nikkei.com/Economy/Trade/China-flexes-economic-muscle-with-ban-on-Taiwanese-grouper.

3 I.e. sanctions that prohibit imports from a target state. Export sanctions ban exports to a target state. See Kirshner (Citation1997). While economists have devoted some attention to firm-level responses to import sanctions, the subject has not received detailed consideration by scholars of international political economy. For examples from the economics literature, see, e.g., Haidar (Citation2017); Crozet & Hinz (Citation2020); Gullstrand (Citation2020).

4 Some scholars distinguish ‘negative’ sanctions from ‘positive’ sanctions that are designed to increase economic exchange between a sender and target. We do not consider the latter here. See Baldwin (Citation1971).

5 Early sanctions research overwhelmingly focused on whether, rather than when, sanctions ‘work’. See, e.g., Galtung (Citation1967); Hufbauer et al. (Citation1985); Baldwin & Pape (Citation1998).

6 Multilateral sanctions regimes are often implemented where the principal sender state lacks sufficient market power alone. See Martin (Citation1992); Bapat & Morgan (Citation2009).

7 The price elasticity of demand for imports is one metric that large-n studies have used to estimate exit costs (Crescenzi, Citation2003; Peterson, Citation2014).

8 One exception is Chen and Garcia (Citation2016).

9 Gholz and Hughes (Citation2021) discuss ‘target elasticity’: 616-617. However, given their focus on the vulnerability of Japanese firms to Chinese export restrictions, they do not give significant consideration to the types of factors relevant to the elasticity of targets faced by import sanctions.

10 See, e.g., Felbermayr, Teti & Yalcin (Citation2019). In this literature, trade deflection describes the situation where a third party outside a preferential trade agreement (PTA) routes its trade through the PTA member with the lowest external tariff in order to access the market of all PTA members. Sanctions may be considered a kind of PTA over certain industries that include all countries except the target state.

11 Transformation can occur at the production and/or processing levels.

12 There is strong empirical support for the proposition that, where a sender or coalition of sender states does not represent a dominant share of global demand, reallocation will minimize the cost of sanctions for target exporters. See Evenett (Citation2002); Haidar (Citation2017).

13 Either because consumers prefer the target product (and no alternative exists), or global supply is tight.

14 This strategy is used by firms to circumvent more traditional barriers to trade, including tariffs, anti-dumping duties, and quotas, and is well documented in the economics and international trade law literatures. See, e.g., Ferrantino, Liu & Wang (Citation2012); Rotunno, Vézina & Wang (Citation2013); Liu & Shi (Citation2019).

15 Smuggling tends to be done for arbitrage or rent seeking purposes. See Kaempfer & Lowenberg (Citation1999).

16 In the China-Japan rare earths case, Chinese exporters disguised rare earth elements as other products by slightly alloying them with different metals: Gholz & Hughes (Citation2021, 622). Firms seeking to circumvent more traditional trade barriers, such as anti-dumping duties, use similar strategies. See, e.g., Gaylor & Kleinfeld (Citation1994); Forganni & Reed (Citation2019).

17 See, e.g., Gholz & Hughes (Citation2021); Lim & Ferguson (Citation2021).

18 An expanded discussion of the data, our measurements, and our methodological approach is contained in Section 2.2 of the supplementary appendix.

19 Kirsty Needham, ‘Australia rejects Chinese “economic coercion” threat amid planned coronavirus probe’, Reuters, 27 April 2020, https://web.archive.org/web/https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-australia-china-idUSKCN2290Z6.

20 See Section 2.3 of the supplementary appendix for an expanded discussion of the potential range of industries that experienced disruption, and how we selected industries for analysis.

21 Some have interpreted remarks by Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian in July 2021 as form of acknowledgement: Stephen Dziedzic, ‘Chinese official declares Beijing has targeted Australian goods as economic punishment’, ABC News, 7 July 2021, https://web.archive.org/web/https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-07-07/australia-china-trade-tensions-official-economic-punishment/100273964. However, no trade barriers have been explicitly described as sanctions, and Chinese officials have maintained that they were in place for other reasons (which we describe in greater detail below and in the accompanying appendix).

22 Amanda Lee, ‘China-Australia relations: looming ban on Australian goods clouds Shanghai import expo’, South China Morning Post, 6 November 2020, https://web.archive.org/web/https://www.scmp.com/economy/china-economy/article/3108787/china-australia-relations-looming-ban-aussie-goods-clouds.

23 Beijing may have had a variety of objectives, including compelling Australian policy change, advancing domestic economic objectives, or deterring third countries from taking certain actions in the future. Evaluating the strategic logic that underpinned the sanctions, and whether different objectives were achieved, is beyond the scope of this paper. For our purposes, we only need to assume that one goal was disrupting Australian exports.

24 For an example of the Australian agricultural industry’s insight into the logic of the sanctions, see Andrew Tillett and Brad Thompson, ‘Canberra keeps wary eye on wheat after China’s latest trade strike’, Australian Financial Review, 2 September 2020, https://web.archive.org/web/https://www.afr.com/politics/federal/canberra-keeps-wary-eye-on-wheat-after-china-s-latest-trade-strike-20200902-p55rmk.

25 DFAT, Australia’s Merchandise Exports and Imports, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, 2021, https://web.archive.org/web/https://www.dfat.gov.au/about-us/publications/trade-statistical-pivot-tables.

26 Coal, copper ores and concentrates, barley, beef, wine, timber logs, lobsters, cotton and forages. We note that the aggregated statistics are weighted heavily by coal, which is of higher value than the other eight sanctioned commodities combined. However, similar results are produced if coal is excluded from the calculations. We also note that this chart does not capture domestic reallocation or transformation—additional forms of adjustment for many industries, as discussed in the appendix (Appendix 2.2).

27 See ibid.

28 We thank Jeffrey Wilson for drawing our attention to this point.

29 This was partially due to the nature of the affected products. Compared to certain manufacturing sectors where firms retain scope to operationalize any excess capacity to increase output over short time scales, the seasonal nature of agricultural production places limits on the ability of exporters to rapidly scale up output to meet new sources of demand. Likewise, bringing additional supplies of mineral resources online takes years.

30 This is consistent with findings in the economics literature. See Haidar (Citation2017).

31 See Ferguson (Citation2022). This can be contrasted with forages, where virtually all exporters lost their licenses. In that case, the informal sanction was relatively robust because of the pre-determined timing of license expirations.

32 While transformation and deflection were less prominent than reallocation, they nevertheless played meaningful roles. Existing economic studies that model the effects of trade disruption do not consider deflection, or the possibility that processors may transform sanctioned products into adjacent products (Cao & Greenville Citation2020; Giesecke, Tran & Waschik Citation2021; Gleeson, Addai & Cao Citation2021; Wittwer & Anderson Citation2021). Future efforts to quantify the cost of sanctions should build these additional dimensions into equilibrium modeling.

33 This was especially true for minerals but also see, e.g., cotton (Appendix 3.2(c)[3]), lobster (Appendix 3.7(b)[4]) and wine (Appendix 3.9(c)[4]).

34 Josh Frydenberg, ‘Building Resilience and the Return of Strategic Competition’, Keynote Address ANU Crawford Leadership Forum, 6 September 2021, https://web.archive.org/web/https://joshfrydenberg.com.au/latest-news/building-resilience-and-the-return-of-strategic-competition/

35 We thank Llewelyn Hughes for prompting us to reflect on this implication.

36 Author calculations. Data from UN Comtrade. Common commodity terms are based on HS codes for copper ores & concentrates (2603), coal (2701), wool (5101), frozen or chilled beef (0201 + 0202), barley (1003), cotton (5201), wine >2l (220421), logs (4403), chips (4401), mutton (0204), live lobsters (030631), wheat (1001), sorghum (1007), almonds shelled or in-shell (80211 + 80212), macadamias shelled or in-shell (080261 + 080262); dairy (0401 + 0402 + 0405 + 0406) and forages (121490). 2018 values are used for barley as it is more representative of previous years.

37 Author calculations. Data from UN Comtrade.

38 Change in lobster and log exports to World ex-China higher than vertical scale. Change specified in label.

References

- Akoto, W., Peterson, T. M., & Thies, C. G. (2020). Trade composition and acquiescence to sanction threats. Political Research Quarterly, 73(3), 526–539. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912919837608

- Allen, S. (2005). The determinants of economic sanctions success and failure. International Interactions, 31(2), 117–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050620590950097

- Allen, S., Cilizoglu, M., Lektzian, D., Su, Y.-H., Early, B. R., & Cilizoglu, M. (2020). The consequences of economic sanctions. economic sanctions in flux: enduring challenges, new policies, and defining the future research agenda’ (Forum). International Studies Perspectives, 21(4), 438–477. In https://doi.org/10.1093/isp/ekaa00

- Baldwin, D. (1971). The power of positive sanctions. World Politics, 24(1), 19–38. https://doi.org/10.2307/2009705

- Baldwin, D. (1985). Economic Statecraft. Princeton University Press.

- Baldwin, D., & Pape, R. (1998). Evaluating economic sanctions. International Security, 23(2), 189–198. https://doi.org/10.1162/isec.23.2.189

- Bapat, N. A., Heinrich, T., Kobayashi, Y., & Morgan, T. C. (2013). Determinants of sanctions effectiveness: Sensitivity analysis using new data. International Interactions, 39(1), 79–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050629.2013.751298

- Bapat, N. A., & Kwon, B. R. (2015). When are sanctions effective? A bargaining and enforcement framework. International Organization, 69(1), 131–162. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818314000290

- Bapat, N. A., & Morgan, T. C. (2009). Multilateral versus unilateral sanctions reconsidered: a test using new data. International Studies Quarterly, 53(4), 1075–1094. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2478.2009.00569.x

- Barber, J. (1979). Economic sanctions as a policy instrument. International Affairs, 55(3), 367–384. https://doi.org/10.2307/2615145

- Barry, C., & Kleinberg, K. B. (2015). Profiting from sanctions: Economic coercion and US foreign direct investment. International Organization, 69(4), 881–912. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002081831500017X

- Barwick, P. J., Li, S., Wallace, J., & Weiss, J. C. (2019). Commercial casualties: political boycotts and international disputes. Working Paper, 10 July. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3417194

- Biersteker, T. J., Eckert, S. E., & Tourinho, M. (eds). (2016). Targeted sanctions: The impacts and effectiveness of united nations action. Cambridge University Press.

- Blanchard, J.-M. F., & Ripsman, N. M. (2013). Economic statecraft and foreign policy: Sanctions, incentives and target state calculations. Routledge.

- Cao, L., & Greenville, J. (2020). Understanding how China's tariff on Australian barley exports will affect the agricultural sector. Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences. Research Report 20.14, https://www.awe.gov.au/abares/research-topics/trade/understanding-chinas-tariff-on-australian-barley.

- Chen, X., & Garcia, R. J. (2016). Economic sanctions and trade diplomacy: Sanction-busting strategies, market distortion and efficacy of China’s restrictions on Norwegian Salmon imports. China Information, 30(1), 29–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/0920203X15625061

- Crescenzi, M. (2003). Economic exit, interdependence, and conflict. The Journal of Politics, 65(3), 809–832. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2508.00213

- Crescenzi, M. (2005). Economic interdependence and conflict in world politics. Lexington Books.

- Crozet, M., & Hinz, J. (2020). Friendly fire: the trade impact of the Russia sanctions and counter-sanctions. Economic Policy, 35(101), 97–146. https://doi.org/10.1093/epolic/eiaa006

- Davis, C., & Meunier, S. (2011). Business as usual? Economic responses to political tensions. American Journal of Political Science, 55(3), 628–646. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2010.00507.x

- Dixit, A., & Norman, V. (1980). Theory of international trade: A dual, general equilibrium approach. Cambridge University Press.

- Drezner, D. (2000). Bargaining, enforcement, and multilateral sanctions: When is cooperation counterproductive? International Organization, 54(1), 73–102. https://doi.org/10.1162/002081800551127

- Drury, A. C. (1998). Economic sanctions reconsidered. Journal of Peace Research, 35(4), 497–509. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343398035004006

- Early, B. R. (2015). Busted Sanctions: Explaining Why Economic Sanctions Fail. Stanford University Press.