Abstract

It is typically argued that civil war acutely inhibits inward flows of foreign direct investment (FDI). However, the evidence is inconsistent and does not support the assumed negative relationship between civil war and FDI. Some studies suggest that FDI enters countries with internal armed conflicts unabated; others show that civil war economies exhibit strong increases in FDI during conflict. Underpinned by a liberal interpretation of war, this scholarship finds these trends to be surprising, counter-intuitive and curious, arguing that FDI enters conflict zones in spite of violence. In contrast, critical perspectives can provide insights by acknowledging that violence can facilitate economic processes such as FDI, creating a particular form of security and stability that can be conducive to FDI inflows. This article examines the Second Sudanese Civil War (1983-2005), a country which exhibited strong increases in FDI during phases of the conflict. It is argued that particular types of violence perpetrated by the government’s armed forces and pro-government militias – groups which were sympathetic to the interests of key investors in the oil industry – facilitated FDI in Sudan’s oil sector during the 2000s to the detriment of large sections of the civilian population affected by the violence.

Introduction

Civil war is often assumed to acutely inhibit foreign direct investment (FDI).Footnote1 However, while the evidence is mixed, studies increasingly suggest that inward flows of FDI enter many civil war economies unabated and, at times, civil war economies attract significant increases in FDI. For some, this appears to be paradoxical, with studies describing this trend as surprising, counter-intuitive and curious, typically arguing that FDI can enter countries with civil wars in spite of political violence. This literature often subscribes to a liberal interpretation of war which assumes political violence has acutely negative impacts on economic processes such as FDI. In contrast, more critical approaches acknowledge the often-violent tendencies of globalised capitalism. By using a case study approach, this article investigates if violence in the Second Sudanese Civil War (1983-2005) facilitated inflows of FDI, which were largely channelled into the oil sector. By appreciating critical perspectives on conflict and development, and presenting evidence from the Sudanese case, this article contributes to the literature by providing insights into why FDI can often flow into civil war economies, helping to shed light on a trend that appears paradoxical to some observers.

The key arguments of this article are as follows: in the 1990s and 2000s, violence perpetrated by the Sudanese military and pro-government militias – targeted at both rebel groups and civilians – facilitated large inflows of FDI to Sudan’s oil sector. On the one hand, this violence cleared large areas of rebels and civilians to enable oil exploration and the construction of key oil-related infrastructure. On the other hand, the military and pro-government militias served to protect the assets of oil companies from rebel attacks in strategically important areas. In response, rebel groups intensified their campaigns but were not able to significantly impact the investor-friendly environment created by the Sudanese government and pro-government militias. In this light, high levels of violence perpetrated by the military and pro-government militias facilitated FDI inflows in the oil sector, creating a particular form of security and stability that benefitted foreign direct investors at the cost of widespread suffering for large sections of Sudanese civilians.

Civil war and FDI

As scholarship on the links between conflict and development grew during the 1990s and 2000s, a prominent set of studies within the civil war literature argued that political violence acutely inhibits economic development (for an overview, see Maher, Citation2018; see also Cramer, Citation2006). Assumed to have inherently destructive effects on physical, human, and social overhead capital, the idea that civil war has negative economic effects is epitomised by an often-used dictum that ‘civil war represents development in reverse’ (Collier et al., Citation2003). Civil wars are said to ‘wreak havoc on economies’ (Gates et al., Citation2012, p. 1715), with ‘astronomical’ costs (Collier et al., Citation2003, p. 80).

A lack of foreign investment in civil war economies is often highlighted as a significant reason – and often the principal cause (e.g., Gates et al., Citation2012; Mehlum & Moene, Citation2012) – as to why conflict stymies economic development. It is argued that civil war directly and indirectly inhibits FDI by destroying assets, increasing the operating costs for companies and, crucially, by the political uncertainty that civil wars foster (e.g., Barry, Citation2018; Blanton & Apodaca, Citation2007; Collier et al., Citation2003; Gates et al., Citation2012; Mehlum & Moene, Citation2012; Mihalache-O’Keef & Vashchilko, Citation2010; Murdoch & Sandler, Citation2002). As Barry (Citation2018, p. 270) notes, the negative relationship between war and FDI is often causally assumed. ‘Intuitively’, Barry observes, ‘states ravaged by the horrors of conflict and war should be viewed negatively by foreign investors’ (Barry, Citation2018, p. 270).

Similar to the broader literature investigating civil war and development, studies into conflict and FDI are often econometric in nature and are typically found within the international business/economics literature, international relations/political science literature and development studies literature. It is increasingly recognised that this research has produced inconsistent results (Barry, Citation2018; Blair et al., Citation2022; Chen, Citation2017; Li, Citation2006; Witte et al., Citation2017), with different studies showing declining, rising and varied flows of FDI during civil wars (Aziz & Khalid, Citation2019; Barry, Citation2018; Blair et al., Citation2022; Busse & Hefeker, Citation2007; Chen, Citation2017; Driffield et al., Citation2013; Guidolin & La Ferrara, Citation2007; Li et al., Citation2017; Mihalache-O’Keef & Vashchilko, Citation2010; Skovoroda et al., Citation2019; Suliman & Mollick, Citation2009; Witte et al., Citation2017). What has become clear, as Barry (Citation2018, p. 273) acknowledges, is that the ‘existing evidence does not support the strong, negative relationship between conflict and investment that is typically assumed’.

Studies that observe higher FDI flows into civil war economies often find this to be paradoxical and this trend has been described as ‘surprising’, ‘counter-intuitive’ and ‘curious’ (Barry, Citation2018; Mihalache-O’Keef & Vashchilko, Citation2010; Skovoroda et al., Citation2019). When evidence suggests that civil war does not deter FDI – and that the latter may increase during conflict – it is typically assumed that FDI inflows occur in spite of civil war violence. For example, in the primary sector, it is argued that firms are bound by geography and are therefore compelled to operate in countries with civil wars if natural resources are located there (Mihalache-O’Keef & Vashchilko, Citation2010; see also Mehlum & Moene, Citation2012, p. 707; Driffield et al., Citation2013; Li et al., Citation2017; Witte et al., Citation2017). It is also argued that if areas of economic interest are located away from areas of conflict, then FDI will be unaffected by the violence; business activities may not face a continuous risk from different types of violence; varied severities of conflict can have varied effects; and Bilateral Investment Treaties can also attenuate policy uncertainty linked to civil wars (e.g., Chen, Citation2017; Dai et al., Citation2013; Mihalache-O’Keef & Vashchilko, Citation2010; Witte et al., Citation2017).

Critical perspectives

Notwithstanding the inconsistent findings of the studies discussed above, they nevertheless typically share a core assumption: that civil war is incongruent with economic processes such as FDI. Similar to broader research into the links between conflict and development, by assuming the negative macro-economic impacts of conflict, much of the scholarship investigating conflict and FDI is underpinned by what Cramer (Citation2006) identifies as an attitude that since the First World War has become known as the liberal interpretation of war. For Cramer (Citation2006, p. 6, 9, 17), this liberal interpretation is flawed and ‘may only be sustained by a form of historical amnesia’, as economic development has typically been ‘accompanied by, hastened by and made by appalling human disruption and violence’. Violence and war were often and are still frequently ‘integrated into the appropriation and production process’ (Cramer, Citation2006, p. 17; see also Tilly, Citation1990). For Gutiérrez-Sanín (Citation2009), while there are indeed many negative economic effects of political violence, the civil war literature has tended to overlook the other side of the balance sheet, for example, the anti-intuitive externalities of conflict that can be pro-growth and distributional. Moreover, while studies subscribing to the liberal interpretation of war readily acknowledge some positive economic outcomes of conflict, this often focuses on how specific actors economically benefit from civil war and its continuation, particularly rebel groups and (typically) illiberal governments. These studies have been criticised for failing to extend this observation to central actors of the global economy, including liberal states and Transnational Corporations (TNCs) operating within the formal economy, with the potential to produce positive macro-economic effects (Maher, Citation2018).

In the context of FDI, although the logic of capitalism may require stability to help guarantee its largely preferred situation of predictability, it is nevertheless possible that foreign capital has an interest in conflict and instability (Cramer, Citation2006, p. 230, 233). If armed conflicts disrupt existing rights to assets, such as land or natural resources, then conflict or the violent exclusion of local interests can provide new ownership and investment opportunities to foreign capital (Cramer, Citation2006, p. 233; see also Guidolin and La Farrara, 2007). In contrast to the explanation that civil war economies can attract investment if violence occurs away from areas of economic interest, critical perspectives highlight how violence can facilitate economic processes such as FDI in areas affected by conflict. For example, when considering natural resource extraction, high levels of violence in economically important areas can be followed by increased levels of FDI into the extractive industries within those areas. Similarly, political ecology scholars have traditionally investigated conflict over natural resources, recognising that extraction of the natural world has led to various levels and types of violence (e.g., Le Billon & Duffy, Citation2018; Marin-Burgos, Citation2014).Footnote2

The critical civil war literature and political ecology scholarship can provide insights into civil war and FDI. In particular, economic processes such as FDI and international trade are often integral parts of war economies, which are not self-sustaining but instead typically interlink with the global economy in different ways. For example, Le Billon (Citation2001a) highlights how both the Angolan government and rebels benefitted from resource extraction and foreign investment in Angola’s extractive industries (namely oil and diamonds) during the civil war, sustaining the large-scale military capacities and political order of these warring groups. Moreover, the global market has often had few scruples when firms invest in countries with civil wars, with some TNCs cooperating and trading with belligerents accused of human rights violations, including states and non-state groups, and have played an enabling role in terms of the strategies of belligerents (Le Billon, Citation2001b; Maher, Citation2018). Guidolin and La Farrara’s (2007) study suggests that in Angola, the war created counterbalancing benefits that outweighed the costs of conflict for foreign direct investors in the diamond industry, while Le Billon (Citation2012, p. 85) notes how various diamond companies in Angola profiteered from conflict diamonds. In Colombia, TNCs in the oil sector benefitted from the conflict as violence perpetrated by the military and their paramilitary allies challenged guerrilla groups and civilians (including campesino farmers, Indigenous groups and trade unionists) who opposed oil exploration in rural areas (Maher, Citation2015a, Citation2018). Through widespread forced displacement of civilians, oil companies were able to expand commercial activities that would have otherwise been unavailable. Similar trends are found in Colombia’s palm oil sector (Maher, Citation2015b, Citation2018; see also Marin-Burgos, Citation2014).

FDI and development

While a fuller discussion does not fit the scope of this article, it is worth noting that there has been considerable debate regarding if economic processes such as FDI are effective in producing economic and human development (for a good discussion, see Sumner, Citation2005). This links to critiques of neo-liberal globalisation – often referred to as the Washington Consensus, in which privatisation and encouraging greater flows of FDI (inter alia) are core tenets – with development economics duly underpinned by a neo-liberal orthodoxy (Escobar, Citation2012, p. 57). Notions of a ‘liberal peace’ also intertwine with the neo-liberal doctrine, involving ‘an ideological mix of neo-liberal concepts of democracy, market sovereignty, and conflict resolution that determine contemporary strategies of intervention’ (Pugh & Cooper, Citation2004, p. 6). The expansion of the neo-liberal economic model across the Global Political Economy, which particularly accelerated after the Cold War, has therefore bolstered the role of FDI in many developing economies, which ‘clearly rely on FDI as a major source of capital’ (Mihalache-O’Keef & Vashchilko, Citation2010, p. 137).

While acknowledging critiques of neo-liberal globalisation, the liberal peace, and conceptions of development in the context of FDI and civil war (e.g., Escobar, Citation2012; Pugh, Citation2005), this article focuses on a core measure of economic development used in investigations analysing the economic impact of civil wars with an aim to provide insights into why FDI can be attracted to countries with civil wars. Nevertheless, this article further attempts to highlight how, on the one hand, influxes of FDI into civil war economies can benefit actors such as oil corporations and political elites while, on the other hand, be linked to acute levels of suffering and severe declines in the welfare of large swathes of civilians affected by violence. As Thomson (Citation2011, p. 327) argues, while the effects of violence may benefit the economy and may represent ‘progress’ in terms of job creation and foreign exchange earnings, this type of violent development represents the obverse of ‘progress’ for large sections of the population affected by political violence.

A case study approach

In contrast to the bulk of studies investigating civil war and FDI – which are overwhelmingly large-N studies using aggregated-national level data – this article employs a case study approach, providing an in-depth analysis of areas affected by conflict in Sudan. This is important given that civil wars rarely (if ever) engulf entire nations but are instead limited to particular regions of host countries. Similarly, processes linked to economic development vary across the territories of countries, including inward flows of FDI. This is reflected in a body of civil war scholarship that uses disaggregated data to provide regional level analyses of conflict (for datasets, see Raleigh et al., Citation2010; Sundberg & Melander, Citation2013).

The Second Sudanese Civil War was selected for investigation because it is often considered a high-intensity conflict, is consistently coded as a civil war/intrastate conflict/internal armed conflict in relevant datasets and the country attracted high levels of FDI during the civil war. The aim is to investigate if FDI was attracted to Sudan in spite of the civil war or if political violence facilitated FDI inflows. While aggregate-level data is used (e.g., the UCDP dataset and UNCTAD data), the analysis attempts to utilise as much disaggregate-level data currently available to study the conflict (e.g., ACLED’s dataset). In terms of datasets, the raw data were obtained from the relevant sources (e.g., UNCTAD, UCDP and ACLED) and the subsequent statistical analysis is largely descriptive in nature. These data were then used with a range of other qualitative sources, including the observations of international organisations, NGOs, human rights groups, government missions (e.g., on behalf of the Canadian government) and scholarly investigations. Many of these sources utilise observations made during fieldtrips to Sudan during the civil war and the period under investigation in this article. These accounts were used to triangulate observations made from the datasets discussed above, as well as provide deeper insights into the links between violence and FDI in Sudan.

The Second Sudanese Civil War (1983–2005)

Following Sudan’s independence in 1956, the country experienced two civil wars.Footnote3 This article focuses on the Second Sudanese Civil War, which began in 1983 and officially ended in 2005, when a peace deal was signed. The war is considered one of the ‘longest and most destructive’ civil conflicts in the world and in African history (Reeves, Citation2002, p. 167). Fought between the Government of Sudan (GOS) vis-à-vis rebel groups originating in the south of Sudan, the conflict is often understood in terms of the largely Arabic-speaking Muslim population in the north of the country, represented by the Sudanese government in Khartoum, vis-à-vis the south of Sudan, inhabited by a population of typically African heritage with Christian or animist beliefs. This includes the largest ethnic groups, the Dinka and Nuer, who were typically represented by sub-state armed groups, the largest of which was the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA).

However, the civil war was more complex than a simple north/south divide. The conflict was not only fought between the Sudanese government and the SPLA. Various militia groups were also active during the civil war. This includes various pro-government militias that fought alongside the government but could also change sides and fight against the public armed forces and often each other. While pro-government armed groups included the Arab muraheleen militias, non-Arab groups that were based in the south of Sudan also fought on the side of the government, including Nuer militia groups (for a good overview, see Patey, Citation2014).

FDI and oil in SudanFootnote4

In the early 1990s, the Sudanese government began implementing neo-liberal economic reforms and, in so doing, increasingly opened-up the Sudanese economy to foreign investment (IMF, Citation1999). This included the Investment Encouragement Act (IEA) in 1990, which was later amended in 1996. In terms of the oil sector, further government reforms were introduced in 1997, including ‘the gradual opening of the importation and distribution of oil products to private sector participation’ (IMF, Citation1999, p. 19).

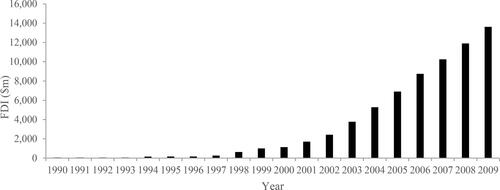

Sudan’s inward FDI stock exhibited strong growth during the 1990s – particularly from the mid-1990s onwards – and continued to grow during the 2000s (). In 1990, Sudan’s total FDI stock was $55.3 million, rising to $165.8 million in 1995 and just over $1 billion in 1999. During the 2000s, FDI stock rose from $1.1 billion in 2000 to $6.9 billion in 2005 and $13.6 billion in 2009. As a percentage of GDP, FDI stock was 1.29% in 1995, rising to 8.7%, 19.6% and 22.5% in 2000, 2005 and 2009, respectively (UNCTAD, n.d.). FDI in Sudan’s oil sector grew rapidly during the 1990s and early 2000s and has been central to the influx of FDI in Sudan. The percentage of FDI in Sudan’s oil sector also increased rapidly from 1996 onwards. In 1995, 6 percent of annual FDI flows was channelled into Sudan’s oil sector, rising to 27 percent in 1996, 40 percent in 1997 and peaking at 95 percent in 2001. Between 1996 and 2005, annual FDI inflows in the oil sector averaged 63 percent of Sudan’s total inward FDI (Alla et al., Citation2015).

Figure 1. FDI stock in Sudan, 1990-2009 (in millions of US Dollars at current prices on 9th April 2019).

Source: UNCTAD (n.d.).

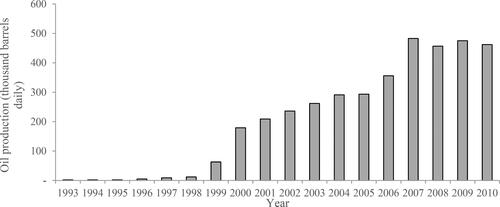

Oil was first discovered in Sudan in 1979 but production did not begin until 1993 when approximately 2,000 barrels of oil per day (bpd) were produced (BP, Citation2019). Relatively small amounts of oil were produced in Sudan until 1999, when production rose by 425 percent, from 12,000 bpd in 1998 to 63,000 bpd in 1999 (). Oil production also grew rapidly in 2000, increasing by 184 percent to 179,000 bpd. While growth predictably slowed from these high growth rates, oil production continued to exhibit strong increases, growing at an annual average of 16 percent in the period 2001-2007, increasing from 209,000 bpd in 2001 to a peak of 483,000 bpd in 2007. In light of the strong growth of FDI in Sudan’s oil sector, oil has benefitted the Sudanese economy and contributed to economic growth, particularly during the 2000s following increases in oil production from 1999 onwards (e.g., IMF, Citation2005; Moro, Citation2009). Sudan’s oil production predictably fell from 2011 onwards, following the independence of South Sudan (July 2011), where significant oilfields were located when the country was unified.

Figure 2. Annual oil production in Sudan, 1993–2010.

Source: BP. (Citation2019).

In a broader context, Sudan has performed well in terms of increases in inward FDI. shows inward FDI stock for small oil producing countries of the Global South (countries producing under 500,000 bpd).Footnote5 Of the 16 countries in , while larger economies attracted overall higher levels of FDI (e.g., Thailand), Sudan exhibited the second highest average annual growth of inward FDI stock between 1995 and 2005 (the year the Sudanese conflict officially ended).

Table 1. Inward FDI stock, average annual increase of FDI stock ($million) between 1995-2005 and oil production in the smaller oil producing countries of the Global South (<500,000 bpd).

Conflict dataFootnote6

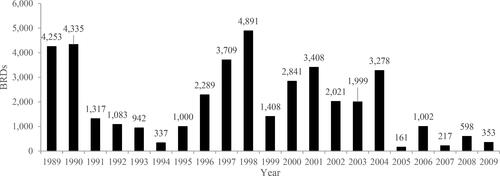

Sudan’s oil sector and levels of FDI grew as the country experienced widespread political violence. As shows, between 1989 and 1992, annual Battle Related Deaths (BRDs) were consistently above 1,000 in Sudan, with an annual average of 2,747. While BRDs fell to below 1,000 in 1993 and 1994 (to 942 and 337, respectively), violence began to rise again from 1995 onwards, reaching 4,891 BRDs in 1998, representing the highest number of BRDs recorded in UCDP’s dataset for Sudan. BRDs remained high between 1999 and 2004, averaging 2,493 annually. Notwithstanding a drop in BRDs in 2005, as the peace agreement between the GOS and SPLA was signed, the period 1995-2006 represents an intensive period of political violence in Sudan, with 28,007 BRDs recorded, representing 68 percent of total BRDs for the entire 1989-2009 period. In terms of forced displacement, there were 35,000 IDPs in 1983, rising to 1.88 million in 1989 and 3.7 million in 2003, according to the GOS’ data. The UN estimated approximately 4 million IDPs in Sudan by the end of 2003, with about 1.7 million displaced in Southern Sudan (see Global IDP Database, Citation2005, p. 54).

Figure 3. Annual BRDs in Sudan, 1989-2009 (BRDs best estimate).

Source: Pettersson et al. (Citation2019).

Conflict data in Sudan’s oil regions

The data above show high levels of civil war violence during the period when Sudan’s economy exhibited strong increases in inward FDI, particularly during the mid- to late-1990s and early-2000s. If civil war violence has facilitated FDI in Sudan, we should expect to see high levels of violence in oil areas, followed by increased levels of FDI in the Sudanese oil industry. This article now considers a key area of expanding oil exploration and production in Sudan during the 1990s and 2000s, with analysis focusing on the Greater Upper Nile of southern Sudan,Footnote7 particularly the oil-rich region of Unity State (for Maps, please refer to Appendix 1).

Unity State was the principal oil producing area of Sudan and included the Unity oilfield (Oil Concession Block 1) and the Heglig oilfield (Block 2).Footnote8 These are the oldest producing oilfields in southern Sudan. Other important concessions included Block 4, part of which (the southern-most section) is in Unity State and includes the Kaikang oilfield, and Block 5A, which straddles Unity State and is where the Thar Jath oilfield is located. Other areas that form important parts of the Unity concession include Rubkona County, as well as key towns such as Bentiu (the capital of Unity State) and Rubkona (see Moro, Citation2009, p. 15). Another important area is Ruweng County, located in the northeast of Unity State and which is straddled by concession Blocks 1 and 5A (for a summary, see ).Footnote9 Unity State is mostly inhabited by Nuer groups (constituting the second-largest ethnic group in the south of Sudan), as well as a minority of Dinka (who, overall, form the largest ethnic group in south Sudan) (Franco, Citation1999, p. 12).

Table 2. Key oil areas of Unity State, Greater Upper Nile.

Due to the availability of data, the figures below focus on events between 1997 and 2009. Nevertheless, studies show significant levels of violence before this period. For example, the work of Millard Burr (Citation1998, pp. 10–11) – including a study designed to quantify (inter alia) estimated deaths in the Sudanese conflict – indicates high levels of violence in the Upper Nile region.Footnote10 Data compiled by Burr suggest potentially hundreds of thousands of war-related deaths in this region during the 1990s, including a spike in 1992-3.Footnote11

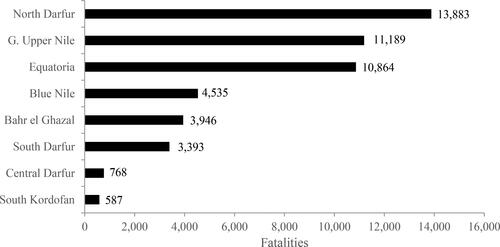

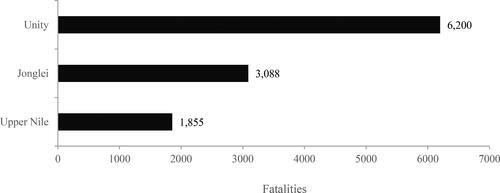

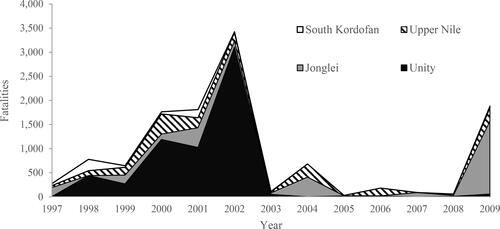

Similarly, in the period 1997-2009, the ACLED dataset shows high levels of fatalities within the Greater Upper Nile region. As shows, following North Darfur, the Greater Upper Nile region recorded the second highest number of fatalities (11,189) in the period 1997-2009.Footnote12 Furthermore, high numbers of fatalities were recorded in the oil producing areas of the Greater Upper Nile region, with Unity recording most fatalities ().

Figure 4. Fatalities in Sudan (top 8 regions by fatalities), 1997-2009.

Source: Raleigh et al. (Citation2010).

Figure 5. Fatalities in Greater Upper Nile, 1997-2009.

Source: Raleigh et al. (Citation2010).

As illustrates, ACLED’s dataset shows rising violence in Unity State after 1997. More specifically, in the period 1998-2002, ACLED records 6,036 fatalities in Unity State, representing 97 percent of all fatalities recorded in Unity State during the entire 1997-2009 period. While fatalities in Unity fell slightly in 1999, they rose sharply between 2000 and 2002, peaking at 3,109 in 2002. Similarly, South Kordofan – immediately north of Unity State – exhibited episodes of violence during this period, including increased fatalities in 1998 and 2001, when 236 and 168 fatalities were recorded.

Figure 6. Annual fatalities in Greater Upper Nile (top 3 regions by fatalities) and South Kordofan, 1997-2009.

Source: Raleigh et al. (Citation2010).

A number of sources illustrate that widespread forced displacement has occurred in regions of Sudan’s oil exploration, particularly Unity State, further indicating an intensification of violence between 1999 and 2002. Human Rights Watch (HRW) provides a conservative estimate of 204,500 people forcibly displaced in Unity State from mid-1998 to February 2001; the International Crisis Group estimates 500,000 IDPs in Unity State in the first 10 months of 2002; the UN OCHA estimated 150,000 to 300,000 people were displaced in Unity State between January and April 2002. Violence displaced 110,000 to 180,000 people between October 2002 and February 2003 in Unity State (for a summary of these figures and sources, see Global IDP Database, Citation2005, p. 50).

Violence in Sudan’s oil areas: context and accounts on the ground

Numerous accounts illustrate increasing levels of violence in Unity State and areas of strategic interest to the oil sector. This includes between 1992 and 1993, violence directed against civilians in the mid-1990s and high levels of violence between 1998-2002, consistent with the data discussed above.

By 1988, the SPLA had become a serious threat to the Sudanese government and, from this position of strength, the rebels began peace negotiations with the government in the same year; however, a peace settlement was precluded by the 1989 Islamist-military coup planned by the National Islamic Front (HRW, Citation2003, p. 114, 121; Jok, Citation2016, p. 173). The newly formed Islamist-military government was ‘determined to develop Sudan’s oil potential’ (HRW, Citation2003, p. 114, 121). To do this, the GOS needed to establish a presence in areas of economic interest to the oil sector. As this article will now discuss, gaining territorial control in areas of strategic importance to the oil sector served a dual purpose: firstly, it provided oil companies with access to oil producing regions and, secondly, it enabled the GOS and its allies to provide security and protect the assets of oil companies.

Territorial control: providing access to Sudan’s oil rich areas

By the mid-1980s, the SPLA dominated most of Unity State (e.g., see Burr, Citation1998; HRW, Citation2003, p. 113). However, during the 1990s, the Sudanese military and pro-government militias achieved territorial control in oil areas by attacking the SPLA and civilians. While the UCDP dataset suggests that, from peaks in 1989 and 1990, BRDs fell between 1991 to 1993 across Sudan as a whole (), the evidence suggests that violence in Sudan’s oil regions continued to be high during this period. In particular, Burr’s (Citation1998) study observed very high levels of violence in 1992-3 in Sudan’s oil regions, particularly directed at civilians (much of which would not be recorded as BRDs), including widespread forced displacement.

It is important to note that forced displacement should not be simplistically viewed as a by-product of armed conflict but is instead typically employed as a concerted strategy of war (e.g., Maher, Citation2018), which has often been the case in Sudan (see Jok, Citation2016). Forced displacement can clear territories of inhabitants who live in areas rich in natural resources, which are subsequently extracted by domestic and transnational corporations (Maher, Citation2015a, Citation2015b, Citation2018). Some refer to such processes as ‘land grabbing’ and development-induced displacement (for example, Grajales, Citation2011). This resonates with Cramer’s (Citation2006, p. 217) critique of the ‘development in reverse’ logic, in which the dual process of forceful asset accumulation and forced displacement are viewed to be central to much of the violence and war around the world.Footnote13 In Sudan, by clearing land of civilians, forced displacement enabled the Sudanese oil sector to expand and allowed for further exploration and extraction of oil, as well as enabling the construction of key infrastructure.

During the early-mid 1990s, Dinka civilians in Ruweng County (the north-eastern part of Unity State, which includes Blocks 1 and 5A) were affected by widespread pro-government militia raiding (HRW, Citation2003, p. 106) and intensive forced displacement perpetrated by militia groups and the Sudanese military, which ‘was everywhere on the attack in the South’ (Burr, Citation1998, p. 14). In February 1992, the GOS intensified its forced displacement campaign in oilfield areas north of Bentiu (Blocks 1 and 2) and began planning for oil exploration (Harker, Citation2000, p. 44; HRW, Citation2003, p. 125). Throughout 1992, an increase in air attacks by the Sudanese government led to thousands of IDPs (Burr, Citation1998, p. 14). Between November 1992 and April 1993 (i.e., the dry season), the Sudanese military (including high altitude bombers and helicopter gunships) and Arab murahleen militias collaborated in a five-month offensive which involved killing, looting, burning and abduction, including in the town of Heglig in Block 2 (Harker, Citation2000, p. 10; HRW, Citation2003, p. 125).

From February 1992 to December 1993, the GOS carried out various military offensives in Unity State, allegedly in preparation for oil production by clearing the area of all villages (Switzer, Citation2002, p. 12). In December 1993, the GOS then launched a new offensive near Heglig. ‘It was after this’, noted the Harker mission (2000, p. 11),Footnote14 ‘that the area around Heglig was more or less deserted except for GOS forces’. Following a 1993 survey of Ruweng County, it was estimated that as much as 70 percent of the population had died due to displacement, migration, and disease between 1989 and 1993 (HRW, Citation2003, p. 106).

Numerous military offensives and episodes of forced displacement continued in Ruweng County, culminating in a large military offensive launched by the Sudanese government with muraheleen militias in October 1996 (Harker, Citation2000; HRW, Citation2003, p. 126). A relief agency assessment team that visited Ruweng County observed high levels of violence, including violence perpetrated by pro-government militias, leading to considerable forced displacement (HRW, Citation2003, p. 128, 162–167). Shortly after this violence – in December 1996 – the Greater Nile Petroleum Operating Company (GNPOC) was formed, a consortium responsible for production in concession Blocks 1, 2 and 4.Footnote15 Furthermore, between 1996 to 1999, the Harker report notes the gradual and permanent displacement within villages closest to the Heglig oilfield. Reports show an acceleration of forced displacement during this period (Harker, Citation2000; HRW, Citation2003).

In addition to Arab murahleen militias, the GOS expanded its presence in oil areas by collaborating with Nuer militia groups in the south, particularly following a split in the SPLA in 1991 which led to a new Nuer armed faction that targeted the rebels and Dinka civilians. The Nuer pro-government forces were key players in the oilfields because they controlled the rural land of Unity State (HRW, Citation2003, p. 117, 129; Patey, Citation2014, p. 66). As Patey (Citation2014, p. 60) notes, supporting and collaborating with these armed factions handed the GOS ‘what its predecessors in Khartoum had failed to achieve for decades: control of the oil regions’. While the SPLA continued to be a significant fighting force and continued to fight against the GOS and pro-government militias, a large amount of GOS-militia violence was directed at the civilian population during this period. This included widespread forced displacement used to further expand and consolidate the GOS-militia presence in oil producing areas (e.g., Jok, Citation2016).

Violence continued to rise between 1998 and 2002 in the oilfields of southern Sudan, peaking in the latter year, according to the ACLED dataset (). This included numerous episodes of violence recorded during these years in the Heglig area, as well as Ruweng County and Unity State more broadly, ‘with a view to clearing a 100-km swathe of territory around the oilfields’, according to a report of the UN Special Rapporteur Leonardo Franco (Franco, Citation1999, p. 10). During this period, other sources similarly observed violence and widespread displacement around oil development areas in Unity State (e.g., Amnesty International, Citation2005; Gagnon & Ryle, Citation2001; Harker, Citation2000; Moro, Citation2009). For example, between April 1999 and July 1999, it was estimated that the decline in population in Ruweng County was approximately 50 percent (Harker, Citation2000, p. 11).

This rise in violence is also linked to key infrastructure projects that cost billions of dollars. The need for the GOS to control territory for infrastructure projects such as pipelines, refineries, bridges and roads increased as the oil sector developed during the 1990s and 2000s (e.g., Gagnon & Ryle, Citation2001, p. 39). A case in point is the construction of the Greater Nile Oil Pipeline, a 1,600-kilometre pipeline that transports oil to market from the oilfields of Heglig and Unity to the Port of Sudan. Core developments of this key infrastructure project occurred during 1997-1999, with high levels of violence observed in oil producing areas during this period, particularly directed at civilians, including widespread forced displacement. In March 1997, the GNPOC agreed to build the pipeline, with construction beginning in 1998. The pipeline was completed 1999 with the inauguration in May 1999. In August 1999, the pipeline became operational and Sudan began exporting crude oil. During this period, the Sudanese government signed contracts worth $1 billion in 1999 with Chinese, Malaysian and European suppliers; moreover, other infrastructure projects were completed, including a refinery with a 2.5 million-ton processing capacity near Khartoum, inaugurated in June 1999 (HRW, Citation2003, p. 120, 173, 458).

The violence perpetrated by the military and pro-government militias facilitated the development of the pipeline by ‘clearing’ areas of civilians and rebel groups. Oil areas that were ‘targeted for population clearance’ were those where a concession had been granted or areas in or close to where the pipeline would traverse (HRW, Citation2003, p. 13; Moro, Citation2009, p. 13). According to Christian Aid (Citation2001, p. 6), hundreds of thousands of villagers were terrorised into permanently fleeing their homes in the Upper Nile region since construction of the pipeline began in 1998, including the destruction of tens of thousands of homes across both Unity State and Eastern Upper Nile (see also Amnesty International, Citation2005, pp. 9–10; HRW, Citation2003, p. 172).

Block 5A

With successful production in Blocks 1 and 2 and the near completion of the pipeline, violence rose from 1999 onwards as the GOS aimed to develop oil interests in Block 5A, leading to ‘disastrous human rights developments’ in this area (HRW, Citation2003, p. 49). With completion of the pipeline, the oilfields in Block 5A became commercially viable and, subsequently, became a military priority for the Sudanese government, which had previously conceded the area to sub-state armed groups (HRW, Citation2003, p. 49, 66, 139). Therefore, another key reason for the rise in violence between 1998 and 2002 was not only the GOS’ attempts to consolidate its presence around older oilfields but also the GOS’ attempts to expand its presence into Block 5A (e.g., see Jok, Citation2016).

As Block 5A was more densely populated when compared to Blocks 1, 2 and 4, levels of forced displacement were particularly high. As HRW (Citation2003, p. 137) notes, no war-related displacement was recorded in Block 5A prior to 1998, the year that a new consortium led by the Swedish company Lundin started oil exploration in the block at Thar Jath. However, from 1998 onwards, displacement became widespread as the military began displacing communities in this area, with claims that this was undertaken to enable international oil companies to develop the oil in this concession (e.g., HRW, Citation2003, p. 76).

In addition to extending the pipeline, other key infrastructure projects were required for Block 5A to be commercially viable. This included core Lundin-funded projects, such as the bridge over the Bahr El Ghazal River (completed in 2000) and the so-called ‘oil road’ (completed in 2001) south of Bentiu, allowing year-round access to Block 5A and the Thar Jath oilfield (Gagnon & Ryle, Citation2001; HRW, Citation2003; MSF, 2002). While the oil road enabled heavy oil equipment to be transported to Block 5A, it also enabled the government’s heavy armour and tanks to travel southward.

In 2000, HRW (Citation2003, pp. 274–275) reported that government-armed offensives to clear areas for the oil road left tens of thousands of civilians uprooted, further claiming that government attacks using helicopter gunships and government troops, in collaboration with pro-government militias, were designed ‘to drive civilians from the oil road and from the area of Lundin’s desired operations’. As Muindi (Citation2002, n.p.) notes, human rights groups claim that the construction of this road ‘precipitated some of the worst cases of oil-linked abuses, with government forces and militias attacking, killing, raping, and maiming civilians living near the road’. In April 2001, Swedish journalist Anna Koblanck visited the oil road, writing that it was ‘bordered with misery and military’ and observed that ‘any villages along the road are empty’, with ‘groups of grey grass huts where not a person can be seen’ (Koblanck, Citation2001, n.p.). ‘In the displaced people’s camps in Bentiu and Rubkona’, she added, ‘there are more witnesses who testify that they have been forced out of the area where Lundin’s road has been built’. The areas depopulated through forced displacement formed ‘a wide ring around the operating sites of the Lundin Petroleum-led consortium and extend the length of its access road’ (deGuzman and Wesselink, Citation2002, p. 11). While Lundin strenuously denies involvement in human rights violations, the company’s chief executive and chairman were charged in Sweden in 2018 for allegations regarding aiding and abetting war crimes in southern Sudan from 1997 to 2003.Footnote16

Research conducted by Prins Engineering (Citation2022, n.p.), employing a multi-temporal study of the Block 5A concession using Landsat satellite images, supports accounts that highlight the impact of forced displacement in Block 5A. The research found ‘massive changes in the traditional farming pattern since the introduction of oil industry’, particularly between 1999 and 2002 (Prins Engineering, Citation2022, n.p.). The pattern of change corresponded with reports of fighting in the respective areas; changes in farming activity were observed between 1999 and 2003 in Block 5A, when ‘farming activity was moved away from areas of the expanding oil industry’ (Prins Engineering, Citation2022, n.p.).

Territorial control: protection of oil assets and infrastructure

In addition to providing access to oil areas for TNCs, a key function of the GOS’ consolidation of territorial control was to provide security for oil assets and infrastructure, particularly from rebel attacks. This was important because the SPLA’s domination of Unity State during the 1980s enabled the rebels to target oilfields in the region (e.g., see Burr, Citation1998; HRW, Citation2003, p. 113). Moreover, throughout the conflict, the SPLA stated that the oil industry represented a legitimate military target, attacking targets with small units in strategically important areas to the oil industry, as well as attacking oil workers, pipelines and other oil company assets (such as trucks) (e.g., see International Crisis Group, Citation2002, pp. 118–119; HRW, Citation2003, p. 460).

From 1992, providing a secure environment for oil companies to operate in Sudan’s oil regions had become a central tenet of the government’s economic policy (Switzer, Citation2002, p. 11). Following the intensive GOS attacks in 1992-1993 (discussed above), survivors claimed that the GOS aimed to clear the SPLA away from areas close to the oilfields (HRW, Citation2003, p. 126). This included forced displacement, which enabled the GOS/militias to provide security for the oil sector and secure strategically important infrastructure by weakening support (whether perceived or real) for rebel groups, as well as seizing and denying resources to opposing groups. Furthermore, following episodes of forced displaced, rebel groups such as the SPLA were often forced to move with the displaced civilians (Jok, Citation2016).

During the 1990s, the GOS was ‘bent on maintaining and extending its security grip on the oil installations and concession areas’ (Jok, Citation2016, p. 197). By attacking opposed armed groups and the civilian population, the GOS created security buffer zones to protect key oil infrastructure and make the oilfields easier to defend (see deGuzman and Wesselink, 2002, p. 3; International Crisis Group, Citation2002, p. 136). Moreover, the Nuer pro-government forces were key players in the oilfields because, with the exception of a few garrison towns, they controlled the rural land of Unity State, including territory that extended into – or was in proximity to be able to protect – concession Blocks 1, 2 and 4 (HRW, Citation2003, p. 117, 129; Patey, Citation2014, p. 66). Nuer armed groups aligned with the government were used as the principal surrogate forces keeping the SPLA presence to a minimum in Blocks 1, 2, and 4 and to provide a buffer zone to protect against SPLA incursions into the Sudan’s oilfields (HRW, Citation2003, p. 114, 118; see also Moro, Citation2009, p. 13; Young, Citation2012, p. 55; Jok, Citation2016, p. 198). Together with the military, these forces provided protection for oil firms in the area, enabling these firms to operate (Moro, Citation2009, p. 13).

The military also provided protection for the Greater Nile Oil Pipeline. As Jok (Citation2016, pp. 188–189) notes, the GOS ‘immediately began to wage war against the civilian population inhabiting the oil region with a view to eliminating any threats these people might pose to the pipeline’. A few days before its inauguration, the GOS announced it was sending an additional 2,500 military volunteers to protect the pipeline (HRW, Citation2003, p. 184). Following a pipeline attack in September 1999, the GOS sent an additional 3,000 police officers to work with the security forces already tasked with protecting the pipeline, oilfields and pumping stations (HRW, Citation2003, p. 175). Within the south, the military provided security for further pipeline development, so that the pipeline could be extended to oilfields in Block 5A for production to proceed in that area (Franco, Citation1999, p. 12).

Similarly, the GOS provided protection for the oil road built as part of the Block 5A development and, by early 2001, the road was heavily defended by patrols of the Sudanese military and guard posts (HRW, Citation2003, p. 42). Widespread displacement in Block 5A was also recorded in 2002 (after the construction of the road was completed), the result of government attacks, with an estimated 50,000 to 60,000 IDPs during this time (deGuzman and Wesselink, 2002). The importance of providing security against attacks on infrastructure was noted by Lundin, whose security head stated the company would not be able to operate in these areas without the army and pro-government militias, with the former providing security along the road and the latter providing security in the entire concession area (Koblanck, Citation2001; see also HRW, Citation2003, p. 265).

As one NGO observed during a 2002 research trip to Ruweng County, forced displacement is quickly followed by the arrival of the Sudanese government, which quickly builds infrastructure such as new roads and then garrisons to protect that infrastructure (Carstensen, Citation2002; Jok, Citation2016; see also deGuzman and Wesselink, 2002). This is followed by the arrival of oil companies and further inward flows of FDI, as well as an influx of oil workers from outside the affected areas (often skilled Chinese or Arab workers were brought in from the north of Sudan, e.g., see Harker, Citation2000; HRW, Citation2003). The GOS also provided protection for foreign oil workers from rebel attacks (e.g., HRW, Citation2003, p. 460).

Rising violence: challenging territorial control

The SPLA challenged GOS/militia territorial consolidation in oil rich areas and violence rose throughout the 1990s/early 2000s. On the one hand, rebel groups directly resisted GOS territorial expansion and control. On the other hand, when the rebels retreated from the immediate areas where the GOS consolidated control, violence rose as armed groups continued to attack and ambush government forces and pro-government militias. This resembled a situation of classic guerrilla warfare, with dire consequences for civilians. In Blocks 1 (Unity), 2 (Heglig) and 4 (Kaikang), the military, pro-government militias and the SPLA fought in battles that were ‘frequent, bloody, and unsparing of civilians’ (HRW, Citation2003, p. 114, 118; see also Moro, Citation2009, p. 13; Young, Citation2012, p. 55; Jok, Citation2016, p. 198).

As discussed, during most of the 1990s, the GOS secured oil areas by collaborating with Nuer armed groups which had territorial control of these areas. However, this situation changed in the latter years of the 1990s. While violence between the GOS/militias and the SPLA continued, a key reason for the increased violence in Sudan’s oil areas was because some of the Nuer armed groups ended their alliance with the GOS in 1999, with some eventually re-joining the SPLA in 2002 (HRW, Citation2003, p. 30; Young, Citation2012, p. 57). While not all Nuer groups turned against the government, this development nevertheless led to key Nuer armed groups and the GOS fighting each other from 1999, with the GOS beginning to capture significant parts of the oil concessions. As the government wanted its own troops to secure and guard the oilfields, attention moved away from primarily targeting the SPLA to also removing Nuer militias in Blocks 1, 2 and 4, replacing them with regular government forces (e.g., Jok, Citation2016, p. 198, 201). During this uptick in violence, all armed groups intensified their levels of violence to challenge the GOS expansion into oil areas.

This was particularly the case as the SPLA and local Nuer militia groups attempted to establish a presence within artillery range of oil installations in and around the Unity and Heglig oil fields, as well as new drilling sites such as the Kaikang oilfield in Block 4. For example, during the dry season between November 2000 and April 2001, the GOS initiated a major offensive to ‘put them in a position to seal off the western boundary to Talisman Energy’s Concession Block 4, a site where drilling and exploration activities had just begun’ (Jok, Citation2016, p. 201). As the conflict intensified and all armed groups increased their activities, the violence rose in the latter years of the 1990s and displacement again became widespread during 1998 and 1999.Footnote17

The situation was similar in Block 5A. As with other blocks, by the late 1990s the government wanted its own troops to secure and guard the oilfields in Block 5A. From 1999, the GOS began to consolidate its military presence in the area and opposed armed groups – including groups previously aligned to the governmentFootnote18 – increased their activities to challenge this consolidation, culminating in fierce fighting and increased levels of violence between 1999 and 2002 in Block 5A (deGuzman and Wesselink, 2002; see also ).

Notwithstanding the resistance the GOS faced to its expansion and consolidation in areas of strategic importance to the oil industry, the rebels were not able to significantly challenge the GOS in these areas throughout the 1990s and early 2000s. Moreover, revenues generated by the oil sector enabled the GOS to more effectively challenge rebel groups. The GOS was often able retake areas lost to the rebels due to the new weaponry it was able to purchase following increasing oil revenues (Jok, Citation2016, pp. 201–202). As such, as levels of violence rose, so too did oil production in Sudan. As the next section will discuss, broader trends in Sudan’s oil production further suggest that oil production – bolstered by the influx of FDI into Sudan’s oil sector – has benefitted from an intensification of the civil war and increases in violence perpetrated by the military/pro-government militias.

Oil production

Oil exploration and production are long-term activities; it can take a number of years for oil to be found and then several more before oil is brought into production and sold to market (e.g., Batruch, Citation2004, p. 151, fn9). As discussed above, Sudan first produced oil in 1993, with production beginning to increase from 1996 onwards, primarily in Blocks 1, 2 and 4. Following entry of ArakisFootnote19 into Sudan’s oil sector in 1992, oil increasingly came online in Sudan within five years. This is also four to five years after the spike in violence in Unity State in 1992 and 1993 and during the period when widespread forced displacement was recorded in oil producing areas (namely, in and/or around Blocks 1, 2 and 4). Moreover, once the larger firm Talisman acquired Arakis and its interests in 1998, bringing superior technology and experience to Sudan’s developing oilfields, it took only one year to boost development of these oilfields.Footnote20 By 1999, Blocks 1, 2 and 4 were producing the bulk of Sudan’s oil, with production rising annually in the period 1997-2006, peaking at 328,000 barrels of oil per day in 2005 for these blocks (FTECOS, Citation2008, p. 24).

Following Lundin’s agreement with the GOS to explore for oil in Block 5A, the company conducted scouting trips and gathered seismic data in 1997 and 1998, followed by exploratory drillings in 1999. In the latter year, Lundin commissioned a socio-political assessment of the concession area and did not expect revenues to be generated for several years given that activities were at the exploration stage (Batruch, Citation2004, p. 151). As discussed above, Unity State exhibited high levels of violence during this period. According to Lundin (Citation2016), while oil exploration and production were disrupted by security concerns following attacks on its facilities – namely, in May 1999 until late 2000, and in January 2002 for 14 months – oil in Block 5A came online in 2006, just five years after oil was discovered and four years after the violence peaked in 2002 in Unity. When drilling was suspended, the company focused on multimillion-dollar infrastructure projects, including Lundin’s ‘oil road’. It has also been alleged that the company used rebel attacks as an excuse to temporarily pull out of the area in order to give government troops the space to clear the concession of suspected rebels and their civilian sympathisers (Muindi, Citation2002). According to relief workers, Lundin’s operations did not resume until March 2001, ‘after the government and its militia had attacked, burned out, and displaced many thousands of civilians from the area’ (Muindi, Citation2002, n.p.). It is also worth noting that oil development and exploration is difficult to conduct during the wet season (typically between April and November), particularly in the absence of an all-weather road to access Block 5A (which was completed in 2001).

Wider implications

The evidence suggests that the territorial control achieved during the 1990s and 2000s by the military and pro-government militias in areas of economic interest served to (a) enable commercial activities to be established and expand within those areas, and (b) protect the interest and assets of investors in those areas from rebel attacks and broader opposition to those commercial activities. This territorial consolidation led to (c) increases in civil war violence, as rebel groups challenged the GOS and militias. However, the rebels were not able to pose a strong enough challenge to deter inward FDI. Thus, in the 1980s, the SPLA controlled most of the oil areas; in contrast, during the 1990s and 2000s the presence of the military and pro-government militias became preponderant in areas of economic interest in Sudan, facilitating higher levels of inward FDI. While violence increased overall, threats to the interests of oil investors nevertheless declined. Moreover, while the neo-liberal economic reforms implemented by the GOS during the 1990s provided favourable conditions for oil investors, GOS-militia violence served to armour those reforms by providing security and exploration opportunities for TNCs operating and investing in the oil sector. Without this security, achieved through intensifying levels of violence in the civil war, Sudan would have been a less attractive place for TNCs to invest. With this in mind, a tipping point was reached during the 1990s whereby the benefits of investing in Sudan’s oil sector outweighed the costs.

A key implication is that violence in civil wars can facilitate FDI inflows if armed groups who support the interests of foreign investors are able to achieve territorial control in areas of strategic and economic importance, thus creating opportunities for investors and limiting threats to those investors. In addition to attacking opposed armed groups, the widespread forced displacement of civilians in and around areas of economic interest is also a key aspect of such violence. In this way, rather than create instability, rising levels of violence can produce a particular form of security and stability that benefits foreign direct investors. This security is likely to be accompanied by economic reforms and investor friendly policies to further attract FDI, with the violence serving to armour those reforms and policies, often with acutely negative impacts on large sections of the civilian population.

The mechanisms outlined above may be particularly important in high-rent industries such as petroleum, perhaps the natural resource most commonly associated with armed conflict and which is linked to violence in various ways (e.g., Le Billon, Citation2012; see also Ross, Citation2015). Moreover, as Li et al. (Citation2017) study indicates, inward FDI flowing into primary sector industries such as oil appears less likely to be deterred by civil war. Given the large export revenues that can be generated from oil extraction, states have an incentive to encourage high levels of FDI in this sector. For example, on the one hand, as oil firms realised large profits from extracting Sudan’s oil, the expansion of the oil sector was accompanied by corruption amongst Sudanese elites (e.g., Jok, Citation2016). On the other hand, revenues generated from oil exports enabled the GOS to purchase weaponry and more effectively challenge rebel groups (e.g., Jok, Citation2016, pp. 201–202).

Similar to other case studies that specifically investigate civil war and FDI – namely, investigations into Angola and Colombia – the case of Sudan suggests civil war violence can facilitate inward FDI. Moreover, the Sudan case exhibits similar mechanisms to those found in Colombia’s civil war (see Maher, Citation2015a,Citation 2015b, Citation2018), a country which also attracted high levels of FDI during particular periods of the conflict. In this light, while this article can provide specific insights into the Sudanese case, it is also possible to investigate if particular mechanisms observed in Sudan’s civil war are present/absent in other armed conflicts, particularly oil-rich countries with civil wars, and whether these mechanisms can result in important (but non-invariant) regularities.Footnote21 Such an approach can provide insights into why the bulk of literature on civil war and FDI has produced inconsistent results and why evidence increasingly suggests that FDI can be attracted to some civil war economies.

It is important to note that violence in civil wars is not only linked to the oil sector (e.g., violence within the diamond and palm oil industries, discussed above). Moreover, evidence from some studies suggest that secondary and tertiary sectors – such as services, manufacturing and high-technology sectors – also attract FDI during civil wars (e.g., Driffield et al., Citation2013; Mihalache-O’Keef & Vashchilko, Citation2010). There are also several examples of civil war economies attracting FDI. As Table 3 shows (Appendix 2), between 1990 and 2019, countries which had intrastate conflicts (lasting at least five years, continuously)Footnote22 overwhelmingly exhibited increases in inward FDI stock, although growth rates varied significantly. From the 34 periods of conflict presented in the table, only two countries (Burundi, 1994-2006 and Indonesia, 1997-2005) exhibited declines in FDI. In contrast, 32 countries exhibited increases in FDI during their respective conflicts, of which nine countries exhibited average annual increases in FDI stock ranging from 20% to 62% during conflict, 14 countries exhibited average annual increases ranging from 10% to 20%, and 10 countries exhibited annual increases ranging from 1% to 8%. While Table 3 does not suggest that violent mechanisms explain why FDI has increased in these countries, future research investigating civil war and FDI could benefit from acknowledging that, under certain conditions, civil wars may facilitate economic processes.

Conclusion

The Second Sudanese Civil War and its intensification in the 1990s and early 2000s did not deter FDI entering Sudan. Large inflows of FDI – mostly in the oil sector – occurred during some of the most intensive periods of violence and in some of the areas most affected by violence. The evidence suggests that, rather than civil war violence deterring inflows of FDI in Sudan, particular forms of violence perpetrated by the military and pro-government militias, targeted at rebels and civilians, facilitated inward FDI flows during the 1990s and 2000s. Instead of creating political uncertainty for investors, this violence created a particular form of stability and security that benefitted oil corporations.

In contrast to studies that suggest FDI may enter civil war economies because the violence is located away from areas of economic interest, the observations of this article suggest that FDI was attracted to the very epicentres of Sudan’s civil war. This supports observations within political ecology scholarship; for example, as Le Billon (Citation2001b: 569) notes, the focus of military activities often become centred on areas of economic significance as natural resources gain in importance for belligerent groups. This indicates that research into civil war and FDI, having already provided important insights into the negative effects of conflict on flows of investment, may benefit from a more nuanced understanding of how internal armed conflicts interact with commodities – particularly (but not limited to) natural resources such as oil – which can bolster our understanding of how civil war economies can attract FDI. By considering the other side of the balance sheet (Gutiérrez-Sanín, Citation2009), a fuller appreciation of the economic effects of conflict can be attained. This should include acknowledging that particular types of civil war violence can facilitate FDI inflows.

It is also important for investigations into conflict and FDI to appreciate that even in high intensity conflicts such as Sudan, high levels of violence do not inevitably create instability for investors. In contrast, a key reason for rising violence in a given case could be a corollary of armed actors – who are sympathetic to the interests of foreign investors – consolidating territorial control in areas of economic importance, with positive outcomes for investors. It is notable that during intensive periods of political violence within Sudan’s oilfields, investors and CEOs (for instance, two former CEOs of Arakis) spoke in positive terms about stability and security, which, as Patey (Citation2014, p. 61) laments, ‘glossed over the brutal counterinsurgency campaign’ waged by the Sudanese government in and around the oil regions in Sudan.

Acknowledging that political violence can be positively linked to processes of economic development such as FDI must not lead to the indulgence of violence or a ‘give war a chance’ mentality that espouses the development benefits of violence (Cramer, Citation2006, p. 47, 288). Instead, accepting that violence can facilitate processes of economic development can highlight that although progress is something that is worth striving for, ‘The idea needs to be tempered by a sharper awareness that it will not erase the essential sources of suffering in society’ (Cramer, Citation2006, p. 47). The challenge is to ‘secure social and economic transformations, inevitably conflictual experiences, while minimising the devastation involved’ (Cramer, Citation2006, p. 288). An appreciation that civil war violence can facilitate FDI inflows could also provide insights for the development orthodoxy. This includes key polices and policy reports of IFIs such as the World Bank, which have tended to overlook the potential for certain types of civil war violence to have positive impacts on economic processes such as FDI. In a similar light, aspects of the liberal peace that are intertwined with the neo-liberal doctrine and promote peace through deeper integration of civil war/post-conflict economies into the global economy through processes such as FDI, may need further scrutiny. Moreover, promoting the role of private capital in conflict zones may require further analysis and nuance. As Guidolin and La Ferrara (Citation2007, p. 1978) note, finding a link between conflict and benefits for investors ‘suggests that much of the wisdom on the incentives of the private sector to end conflict may need closer scrutiny’. Given that some firms can benefit from civil war, this may impact their incentives to exert political and economic pressure to avoid or stop ongoing conflicts (Guidolin & La Ferrara, Citation2007, p. 1992). It is also important to reiterate that while violent forms of development can produce benefits for some actors (including states, sub-state armed groups and TNCs) and facilitate economic processes such as FDI, this type of violent development has acutely negative effects on millions of people affected by violence, who typically experience immense welfare losses and suffering.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (359.2 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

David Maher

David Maher is a Reader in International Relations at the University of Salford, where he is currently the Head of Subject Group for Politics and Contemporary History. His research adopts a political economy approach to analyse the links between political violence, economic development and processes of economic globalisation, particularly international trade and foreign direct investment.

Notes

1 A broad definition of civil war violence is employed in this article that includes various forms of violence, including battle-related deaths, fatalities, forced displacement, and violence against combatants and civilians perpetrated by recognised armed groups of the conflict. In Sudan, this refers to the Sudanese military, pro-government militias and rebel groups. Terms such as ‘civil war and internal armed conflict are used interchangeably.

2 The author would like to thank an anonymous reviewer for this suggestion.

3 The First Sudanese Civil War was fought between 1955 and 1972.

4 Throughout this article, reference is made to Sudan as a unified country (i.e., before South Sudan gained independence in 2011).

5 Oil production refers to 2005.

6 For this article, the dataset this author considered to have the most complete data have been used where possible.

7 Often simply referred to as the Upper Nile.

8 Whether Heglig falls within the boundaries of Unity State or South Kordofan is disputed. Up to 2003, Heglig was generally understood to be part of the Unity State administration (Johnson, Citation2012, p. 565). It is worth noting that the available maps used in Appendix 1 were all produced post-2003.

9 Ruweng County is also known as Pariang.

10 In 1994, the GOS divided Greater Upper Nile into the states of Upper Nile, Jonglei and Unity State. The data provided by Burr refer to all three states.

11 Unfortunately, the report does not provide a precise definition of what constitutes a war-related death but it appears that a broad definition is used to include deaths from famine, murder and so on.

12 Fatalities’ in ACLED’s dataset cover events – such as massacres – that are not captured in UCDP’s BRD dataset, which records deaths directly related to combat. Therefore, the ACLED figures are higher. Moreover, ACLED’s data are not available before 1997.

13 Cramer (Citation2006) identifies this as primitive accumulation. However, applying primitive accumulation to contemporary debates, including concepts such as accumulation by dispossession (Harvey, Citation2003), has been critiqued (for instance, see Zarembka, Citation2002). Nevertheless, critical scholars typically accept that capitalist accumulation was violent in its incipiency and continues to be violent in many places of the world today. It is this broad framework that is employed by this article.

14 Named after John Harker, who led a human rights team appointed by the Canadian government in 1999 to investigate the links between war and oil in Sudan.

15 When it was formed, the GNPOC consisted of Talisman Energy (previously the Canadian branch of British Petroleum), the China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC), Malaysia’s Petronas and Sudan’s state oil company, Sudapet.

16 At the time of writing, the case is still pending.

17 As UCDP’s and ACLED’s data show only BRDs and fatalities, levels of forced displacement are not reflected in these data.

18 Until 2002, these breakaway groups and the SPLA also fought each other.

19 A small Canadian oil exploratory company which acquired oil concessions from Chevron.

20 It must be noted that Chevron had already begun developing some of these sites, particularly during the early 1980s.

21 For a detailed discussion of a scientific/critical realist position on causality in the context of civil war, see van Ingen (Citation2016).

22 FDI involves a high level of commitment from the investor and host country. It can be difficult for investors to quickly exit an economy. To reflect this, Table 3 shows conflicts lasting at least five years.

23 Other oilfields in these Blocks include: El Toor, Toma South, El Nar, Talih, Munga, Timsa and Bamboo.

References

- Alla, O., Abdelmawla, M., Mohamed, A., & Mudawi, S. (2015). Evaluation of foreign direct investment inflow in Sudan: An empirical investigation (1990–2013). Journal of Business Studies Quarterly, 7(2), 149–168.

- Amnesty International. (2005). Sudan: Who will answer for the crimes? AFR 54/006/2005. https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/afr54/006/2005/en/.

- Aziz, N., & Khalid, U. (2019). Armed conflict, military expenses and FDI inflow to developing countries. Defence and Peace Economics, 30(2), 238–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242694.2017.1388066

- Barry, C. M. (2018). Peace and conflict at different stages of the FDI lifecycle. Review of International Political Economy, 25(2), 270–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2018.1434083

- Batruch, C. (2004). Oil and conflict: Lundin Petroleum’s experience in Sudan. In A. J. K. Bailes & I. Frommelt (Eds.), Business and security: Public-private sector relationships in a new security environment (pp. 148–160). SIPRI; Oxford University Press.

- Blair, G., Christensen, D., & Wirtschafter, V. (2022). How does armed conflict shape investment? Evidence from the mining sector. The Journal of Politics, 84(1), 116–133. https://doi.org/10.1086/715255

- Blanton, R. G., & Apodaca, C. (2007). Economic globalization and violent civil conflict: Is openness a pathway to peace? The Social Science Journal, 44(4), 599–619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soscij.2007.10.001

- BP. (2019). Statistical review of world energy. Underpinning data. https://www.bp.com/en/global/corporate/energy-economics/statistical-review-of-world-energy.html.

- Burr, M. (1998). Working document II: Quantifying genocide in Southern Sudan and the Nuba Mountains 1983–1998. U.S. Committee for Refugees (USCR).

- Busse, M., & Hefeker, C. (2007). Political risk, institutions and foreign direct investment. European Journal of Political Economy, 23(2), 397–412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2006.02.003

- Carstensen, N. (2002). Hiding between the streams: The war on civilians in the oil regions of southern Sudan. Christian Aid and Dan Church Aid.

- Chen, S. (2017). Profiting from FDI in conflict zones. Journal of World Business, 52(6), 760–768. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2017.06.005

- Christian Aid. (2001). The scorched earth: Oil and war in Sudan.

- Collier, P., Elliot, L., Hegre, H., Hoeffle, A., Reynal-Querol, M., & Sambanis, N. (2003). Breaking the conflict trap: Civil war and development policy. World Bank.

- Cramer, C. (2006). Civil war is not a stupid thing; Accounting for violence in developing countries. Hurst & Company.

- Dai, L., Eden, L., & Beamish, P. W. (2013) Place, space, and geographical exposure: foreign subsidiary survival in conflict zones. Journal of International Business Studies, 44(6), 554–578. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2013.12

- deGuzman, D., & Egbert, W. (2002). Depopulating Sudan’s oil regions. European Coalition on Oil in Sudan.

- Driffield, N., Jones, C., & Crotty, J. (2013). International business research and risky investments, an analysis of FDI in conflict zones. International Business Review, 22(1), 140–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2012.03.001

- Escobar, A. (2012). Encountering development the making and unmaking of the third world. University Press.

- Fatal Transactions and the European Coalition on Oil in Sudan (FTECOS). (2008). Sudan’s oil industry: Facts and analysis, April 2008’.

- Franco, L. (1999). Situation of human rights in the Sudan (Human rights questions: Human rights situations and reports of special rapporteurs and representatives). United Nations. http://digitallibrary.un.org/record/312719

- Gagnon, G., & Ryle, J. (2001). Report of an investigation into oil development, conflict and displacement in Western Upper Nile Sudan. Canadian Auto Workers Union.

- Gates, S., Hegre, H., Nygard, H. M., & Strand, H. (2012). Development consequences of armed conflict. World Development, 40(9), 1713–1722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2012.04.031

- Global IDP Database. (2005). Profile of internal displacement: Sudan. Compilation of the Information Available in the Global IDP Database of the Norwegian Refugee Council. Norwegian Refugee Council/Global IDP Project.

- Grajales, J. (2011). The rifle and the title: Paramilitary violence, land grab and land control in Colombia. Journal of Peasant Studies, 38(4), 771–792. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2011.607701

- Guidolin, M., & La Ferrara, E. (2007). Diamonds are forever, wars are not: Is conflict bad for private firms? American Economic Review, 97(5), 1978–1993. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.97.5.1978

- Gutiérrez-Sanín, F. (2009). Stupid and expensive? A critique of the costs-of-violence literature. Crisis States Working Papers Series No. 2. LSE/DESTIN.

- Harker, J. (2000). Human security in Sudan: The report of a Canadian Assessment Mission. Prepared for the Minister of Foreign Affairs. Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade.

- Harvey, D. (2003). The new imperialism. Clarendon lectures in geography and environmental studies. Oxford University Press.

- Human Rights Watch (HRW). (2003). Sudan, oil, and human rights. Human Rights Watch.

- IMF. (1999). Sudan: Recent developments. IMF Staff Country Report No. 99/53. IMF.

- IMF. (2005). Sudan: Staff report for the 2005 Article IV consultation. IMF Country Report No. 05/180. IMF.

- International Crisis Group. (2002). God, oil and country: Changing the logic of war in Sudan. International Crisis Group Africa Report N° 39. International Crisis Group.

- Johnson, D. H. (2012). The Heglig oil dispute between Sudan and South Sudan. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 6(3), 561–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/17531055.2012.696910

- Jok, J. M. (2016). Sudan: Race, religion, and violence. 2nd ed. Oneworld Publications.

- Koblanck, A. (2001). The oil road. ACNS. https://www.anglicannews.org/news/2001/06/the-oil-road.aspx

- Le Billon, P. (2001a). Angola’s political economy of war: The role of oil and diamonds, 1975–2000. African Affairs, 100(398), 55–80. https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/100.398.55

- Le Billon, P. (2001b). The political ecology of war: Natural resources and armed conflicts. Political Geography, 20(5), 561–584. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0962-6298(01)00015-4

- Le Billon, P. (2012). Wars of plunder: Conflicts, profits and the politics of resources. Oxford University Press.

- Le Billon, P., & Duffy, R. (2018). Conflict ecologies: Connecting political ecology and peace and conflict studies. Journal of Political Ecology, 25(1), 239–260. https://doi.org/10.2458/v25i1.22704

- Li, Q. (2006). Political violence and foreign direct investment. In M. Fratianni (Ed.), Regional economic integration (pp. 225–249). Elsevier/JAI Press.

- Li, C., Murshed, S. M., & Tanna, S. (2017). The impact of civil war on foreign direct investment flows to developing countries. The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development, 26(4), 488–507. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638199.2016.1270347

- Lundin. (2016). Lundin history in Sudan: 1997-2003. Lundin Petroleum AB. https://www.lundinsudanlegalcase.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/legacy-document_en-1-decpdf.pdf

- Maher, D. (2015a). The fatal attraction of civil war economies: Foreign direct investment and political violence, a case study of Colombia. International Studies Review, 17(2), 217–248. https://doi.org/10.1111/misr.12218

- Maher, D. (2015b). Rooted in violence: Civil war, international trade and the expansion of palm oil in Colombia. New Political Economy, 20(2), 299–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2014.923825

- Maher, D. (2018). Civil war and uncivil development: Economic globalisation and political violence in Colombia and beyond. 1st ed. 2018 ed. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Marin-Burgos, V. (2014). Access, power and justice in commodity frontiers: The political ecology of access to land and palm oil expansion in Colombia. https://research.utwente.nl/en/publications/access-power-and-justice-in-commodity-frontiers-the-political-eco.

- Mehlum, H., & Moene, K. (2012). Aggressive elites and vulnerable entrepreneurs: Trust and cooperation in the shadow of conflict. In M. R. Garfinkel & S. Skaperdas (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of the economics of peace and conflict (pp. 706–729). Oxford University Press.