Abstract

This paper provides a domestic explanation for variation in de jure central bank independence (CBI) in nondemocracies. I argue that there is a nonlinear relationship between personalism and CBI: regimes with very low and very high levels of personalism tend to have lower CBI compared to states with intermediate personalism. Where personalization is low, autocrats face greater constraints and more frequent political challenges, leading to increased contestation over political institutions. In these states, leaders choose lower CBI to signal their control over monetary policymaking and prevent dissent over economic policy. In contrast, in strongly personalist regimes, leaders face few risks associated with CBI, but they discount the benefits of CBI and thus prefer not to implement costly central bank reforms. Nondemocracies with intermediate levels of personalism tend to have the highest levels of CBI. I support these arguments using recent data on CBI from 1970–2012.

Introduction

In 2019, Iranian lawmakers passed a comprehensive set of banking reforms, the country’s first in over thirty years (Kalhor, Citation2016). Although the bill included major changes to central bank legislation, including a price stabilization mandate, the reforms fell short of an earlier 2016 bill, in which the central bank governor had proposed sweeping enhancements to the bank’s formal policymaking independence (Financial Tribune, Citation2016). When this first bill failed to advance, parliament introduced an alternative bill that notably omitted all provisions on central bank independence (CBI). The change received criticism from central bank governor Abdolnasser Hemmati, who warned that it ‘is at odds with the [Central Bank’s] independence,’ and noted that ‘central banking experts were not consulted in its the design.’ (Financial Tribune, Citation2019) Currently, the Central Bank of Iran continues to require presidential approval for monetary policymaking decisions, significantly limiting the bank’s autonomy.

Iran’s recent attempts at central bank reform illustrate that such reform can be difficult and contentious, and that it is not uncommon for central bankers and political leaders to be publicly at odds with one another even in autocratic settings. But the case also raises broader questions about the role of CBI in authoritarian countries. Over the previous three decades, the idea that central banks should operate without operational and political interference from governments has become a global norm, and many countries have increased the independence of their central banks.

Yet even where laws granting authority to central banks are in place, banks can still be subject to political pressures that limit their independent decision-making power in practice. Legal CBI can thus diverge significantly from actual, de facto independence. Because of this potential disconnect between legal status and actual practice, central bank reforms may not lead to the intended monetary policy stability.Footnote1 Scholars have noted that this difficulty is most pronounced in autocracies, where policymaking is subject to fewer checks and balances (see Bodea & Hicks, Citation2015). Because dictatorial governments often retain the power to unilaterally reverse or ignore existing laws, and to fire or imprison opponents, it is difficult for central banks to signal that they are operating independently of government interference (e.g. Broz, Citation2002). Because of this, CBI in nondemocracies is thought to be ineffective and to have little effect on monetary policy stability (see Bodea & Hicks, Citation2015; Broz, Citation2002; Keefer & Stasavage, Citation2003; but see also Garriga & Rodriguez, Citation2020 ).Footnote2

Still, the Iranian reform case presents a clear puzzle: if it is true that de jure CBI lacks effectiveness in nondemocracies, then it is unclear why these states would ever implement potentially costly CBI reforms, in either direction of reform. We also would not expect to find extensive political debate and contestation over such reforms. Similarly, if CBI does not matter in autocracies, then we would expect to see little overall variation in CBI across these states. Nevertheless, de jure CBI varies considerably across nondemocracies and central bank reforms occur not infrequently, with 171 identified cases of reform in nondemocracies between 1970–2012, most of which changed towards greater independence (Bodea et al., Citation2019).Footnote3 Overall, legal central bank autonomy varies significantly across nondemocracies, ranging from nearly nonexistent to higher than that of the average democracy.Footnote4 There is also a trend towards greater CBI across time for all states, although this trend is less pronounced for nondemocracies.

Despite this variation, the causes and effects of CBI in authoritarian states are not fully understood. The central puzzle that this paper therefore seeks to address is what factors determine legal CBI under nondemocracy; specifically, what might explain the significant variation in CBI across these states. In evaluating this puzzle, I assess domestic autocratic preferences for CBI and explore autocrats’ concerns about how much to delegate to central banks.

In particular, this paper suggests that autocrats weigh the potential benefits of CBI against the domestic costs of such reform. Because CBI is such a strong international norm, a nominally independent central bank can lead to greater international creditworthiness and increased foreign investment. It also suggests a commitment to stable economic policy and development of the banking sector (e.g. Garriga, Citation2010; Garriga & Rodriguez, Citation2020; Maxfield, Citation1997).Footnote5 These motivations notwithstanding, autocrats also consider the domestic political consequences of an independent central bank.

CBI can pose unique domestic threats to autocratic governments. In addition to their formally defined functions, autocratic central banks play an active part in managing regime funding; they hold a symbolic role as beacons of sound economic policy, providing transparency and expertise; and they are frequent sites of political protest and dissent. In many autocracies, central bankers interact with diverse political actors and play an active role in government critique. As such, central banks can be influential in either supporting or undermining autocratic rule. Because of this, autocrats worry about providing central banks with formal independence, and some autocrats prefer to keep central banks dependent.

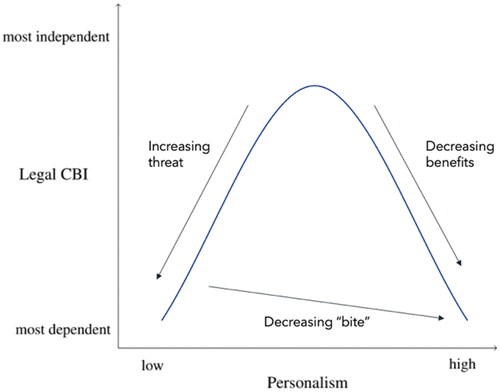

However, this calculus is not the same for all autocrats. My central argument is that there is a non-linear relationship between the level of personalism in a dictatorship and de jure CBI. Authoritarian leaders with very low and very high personalism prefer lower levels of CBI, whereas CBI tends to be highest in states with intermediate levels of personalism. In other words, I suggest that there is an inverted U-shaped relationship between CBI and personalism.

To explain this nonlinear relationship, I argue that autocrats in states with low personalism are particularly likely to view CBI as a threat. Nonpersonalist states tend to be subject to greater constraints that limit their ability to respond to political challenges, making CBI potentially risky. As a result, nonpersonalist autocrats prefer to keep central banks dependent to signal that they are firmly in control of economic policy. In contrast, where personalism is very high, CBI is associated with fewer political risks for leaders and lower costs, but leaders tend to discount the potential benefits of reform. This is partly because such reforms have low credibility in the eyes of investors, but also because highly personalist leaders prefer to maintain tools of repression and rent extraction to building sound monetary institutions. As a result, personalist autocrats have few incentives for central bank reforms.

Instead, I find that states with intermediate personalism are most likely to delegate to central banks. CBI is still potentially effective in these states and can help moderately strong personalists signal to elites that they are committed to stable monetary policy, while also placing some potential limitations on elite spending. Overall, I suggest that autocrats need to feel somewhat domestically secure, but not ‘too’ secure, to implement CBI.

This paper contributes to the existing literature on central banks by exploring the competing domestic pressures autocrats face when determining central bank legislation. Existing scholarship suggests that autocratic institutions often have functions that go beyond mere appearance and that may be important to the survival of a regime (see e.g. Gandhi, Citation2008; Magaloni, Citation2006; Pepinsky, Citation2014; Svolik, Citation2012). I argue that a similar reasoning can be extended to central banks, which have received less scholarly attention. I find abundant evidence that central banks are of close concern to autocrats. Statistical analysis using recent data on worldwide CBI between 1970–2012 supports this theoretical argument. The next section provides an overview of the existing literature.

Background: when do states increase CBI?

The key functions of central banks include conducting monetary policy, ensuring the stability of the financial system, and acting as a lender of last resort. CBI is important because it solves the time-inconsistency problem of monetary policy (see Kydland & Prescott, Citation1977), which arises because policymakers are motivated to promise low-inflation policies, but subsequently have incentives to renege on this promise to gain short-term political advantages. Because private actors can predict this, announcements of low-inflation policies will not lead to the expected growth. Hence many governments delegate to independent central banks.

Scholars distinguish several dimensions of CBI, including whether the central bank can set its own policy goals, whether it may lend to the government, and whether the government has influence over hiring the central bank’s board members.Footnote6 A large body of research suggests that CBI leads to more stable monetary policy and lower inflation in democratic states (See e.g. Alesina & Summers, Citation1993; Crowe & Meade, Citation2008; Cukierman, Webb, & Neyapti, Citation1992; Grilli et al., Citation1991). Yet this mechanism may not hold in countries with weak rule of law, particularly in autocracies.

Although most of the existing literature focuses on democracies in assessing the determinants of CBI, many of its arguments can be applied to autocracies. Early work suggests that instability of the executive negatively affects CBI (Cukierman & Webb, Citation1995, p. 401), finding that dependent central banks are associated with frequent political transitions, and that replacement of a governor is more likely shortly after transition. Other research finds that the presence of multiple veto players (Keefer & Stasavage, Citation2002, Citation2003; Hallerberg, Citation2002), checks and balances (Moser, Citation1999), and diverse political coalitions (Crowe, Citation2008) make credible delegation to central banks more likely. Bernhard (Citation1998) argues that CBI can help resolve coalitional conflicts. Related research finds that CBI reforms are more likely when a democratic government expects to lose office and wants to ‘lock in’ monetary policy reforms (e.g. Boylan, Citation1998).Footnote7

In addition, it is widely accepted that diffusion processes have played an important role in the spread of nominal CBI, with exposure to international trade and investment as key drivers (e.g. Polillo & Guillén, Citation2005). This can be due to socialization (Bodea & Hicks, Citation2015; McNamara, Citation2002), epistemic communities, and the emergence of economic ideas about the benefits of CBI (e.g. Johnson, Citation2016).

Existing literature also suggests that autocracies face unique difficulties with respect to monetary policy. Overall, nondemocracies have persistently lower levels of CBI. CBI is positively correlated with political stability and civil liberty (Bagheri & Habibi, Citation1998), and is higher in OECD countries with strong checks and balances (Moser, Citation1999). Yet previous research makes somewhat inconsistent predictions with respect to autocracies. While diffusion processes might explain why some autocracies have adopted CBI (Polillo & Guillén, Citation2005), the persistent differences between regime types point to additional, domestic drivers of CBI among autocracies.

Relatedly, CBI could have international benefits, by signaling to foreign investors that autocrats are committed to stable monetary policy and have the institutional capacity for longer-term reforms, as existing research on central banks in non-OECD states finds. For instance, Garriga notes that ‘CBI is one of the principal signals that international investors and lenders ask for’ (Garriga, Citation2010, p. 58), because it can signal creditworthiness (Maxfield, Citation1994, p. 564). Nominal CBI in autocracies could then primarily be a signal to foreign audiences. Lastly, some authors have noted that independent central banks make more credible ‘scapegoats’ during economic crises (e.g. Boylan, Citation2001, p. 55). For all these reasons, we might expect authoritarian states to adopt CBI.

Yet there are other reasons to think that autocracies have fewer incentives to implement CBI than democracies. Autocratic governments often have wide-ranging means for extracting rents, decreasing the relevance of formal monetary institutions (e.g. Geddes et al., Citation2018). Lack of transparency is also an obstacle to credible CBI, making autocracies more reliant on fixed exchange rates (Broz, Citation2002). Others have pointed out that in practice, autocracies can choose any combination of CBI and fixed or floating exchange rates, implying that they are not simple substitutes.Footnote8

Relatedly, while most of the literature focuses on time inconsistency, many autocracies do not hold regular elections. Even in electoral autocracies, autocrats can set elections in a way to coincide with positive economic performance, when the leader’s popularity is at its peak, and so may be less dependent on short-term manipulation. Nevertheless, there is growing evidence that electoral business cycles do exist in autocracies (see Blaydes, Citation2011; Higashijima, Citation2016). Changing international norms have also led autocrats to hold elections more frequently, and CBI may have increasing relevance as a result (see Gandhi & Lust-Okar, Citation2009).

If autocrats view central bank reform as relatively inexpensive, then it would make sense for them to adopt CBI to potentially capture its benefits, even if these reforms fall short of true autonomy. Yet there are reasons to believe that it can be associated with significant costs in nondemocratic settings. For instance, in one of the few works specifically addressing autocratic central banks, Bodea et al. argue that CBI limits fiscal spending in party-based regimes, decreasing access to patronage and thereby increasing their likelihood of breakdown. (Bodea et al., Citation2019). Based on this finding, some types of autocracy may be less likely to have independent central banks, pointing a need for a broader analysis of autocratic CBI.

Importantly, we do not yet have a clear understanding of the exact channels through which central banks support autocratic rule, what political conflicts exist over central banking, or what role central banks may play in potential regime change processes. Central bankers are often viewed as technocratic, apolitical actors (see e.g. Lohmann, Citation1998; Braun et al., Citation2020; see also Adolph, Citation2013 ). This view obscures the extent to which central banks are sites of complex political interactions between central bankers, governments, and third-party actors. This paper seeks to remedy this by providing a framework for conceptualizing CBI in autocracies. The next section explains my theoretical argument.

Personalist and nonpersonalist rule

Although the primary goal of authoritarian leaders is to remain in office, autocrats vary in the extent to which they need the support of other elite actors to survive. I follow Geddes, Wright, and Frantz in defining ‘personalism’ as the degree to which an autocrat has concentrated his political power. (Geddes et al., Citation2018, p. 1) Highly personalist autocrats, such as Turkmenistan’s Niyazovv, tend to be unconstrained by political parties, whereas nonpersonalist regimes require the support of a larger number of actors inside a party or central committee to remain in office. Personalism has received much attention in recent academic research in part because it has proven to be one of the most enduring features of authoritarian politics, with levels of personalism increasing in recent years (Geddes et al., Citation2018). Personalism has been found to influence a wide range of autocratic policies, including conflict behavior (e.g. Weeks, Citation2012) and membership in international institutions (e.g. Vreeland, Citation2008).

While earlier research on authoritarianism classifies regimes into distinct categories, with personalist regimes grouped into one ‘box’, recent research advocates for a unified approach, arguing that all nondemocracies have an underlying degree of personalism that varies both across states and within countries over time (Geddes et al., Citation2018). This has the advantage of avoiding issues of overlap and gaps between regime categories. The continuous approach chosen by Geddes et al. focuses on the latent dimensions of personalism, in which personalism is a function of how much control an individual leader has over the party, appointments to key political office, and the military. Notably, it does not explicitly consider the role of other formal institutions, such as courts or central banks. While it is certainly reasonable to assume that highly personalist autocracies also have central banks with low de facto independence, this is not explicitly a component of how personalism is measured. In addition, since personalist measures focus on actual power concentration rather than de jure institutional rules, personalism alone cannot answer questions about legal variation in central banks.

How does the continuous approach map onto existing regime classifications? Most states with low levels of personalism are party-based autocracies, but they also include some institutionalized military dictatorships. States with the highest level of personalism tend to fall firmly within previous personalist classifications, but also include a few highly personalist monarchies. However, states with intermediate levels of personalism do not form a unique category, but are a diverse set of states that includes, for instance, certain monarchies (e.g. Jordan) and some established civilian autocracies with a strong party leader (e.g. Belarus in the 1990s). Despite their significant differences, this paper argues that states with middling personalism share some features that are of importance when it comes to CBI.Footnote9

This paper therefore explores the relationship between CBI and personalism, finding that it is not as straightforward as one may expect. First, I argue that central banks have the capacity to support or undermine dictatorial rule, and because of this, autocrats pay close attention to the institutional rules that govern their central banks. One notable consequence of this is that nonpersonalist autocracies often prefer dependent central banks, even as they mirror democratic states in many other respects. On the other hand, I find that legal CBI is most likely in states with middling levels of personalism. The next section explores this mechanism in detail.

Costs and benefits of CBI under autocracy

Because existing evidence suggests that the link between inflation and CBI is significantly weakened under autocracy, inflation control may not be a primary motivation for autocrats in reforming CBI. Nevertheless, a wealth of literature has shown that nominal CBI can provide significant economic benefits even in states with weak rule of law, by increasing international creditworthiness and legitimacy and helping attract foreign investment (Garriga, Citation2010; Garriga & Rodriguez, Citation2020; Maxfield, Citation1994). A country that keeps central banks dependent, particularly at a time when CBI is a global norm, forgoes these potential gains.

Contrasting these benefits, autocrats also face potential costs in reforming central banks. While previous research often presumes that CBI is relatively costless under autocracy (e.g. Johnson, Citation2016, p. 58), I argue that autocratic central banks can be important sites of political contestation. Since the costs of CBI under autocracy have not been clearly articulated in most existing work, I briefly illustrate my point by describing two key functions of autocratic central banks: (1) information provision and political dissent; and (2) regime funding.

Information provision and dissent

Examples of contestation over central banks are surprisingly common. In February 2021, for instance, more than a thousand protesters gathered outside the central bank in Yangon, Myanmar, and called for the bank staff to join their pro-democracy movement - and many staffers did (Myanmar Times, Citation2021; VOI, Citation2021). The site of these protests had both a symbolic and a practical purpose. In practical terms, the protestors were hoping to limit the military’s ability to finance a return to military rule. As one protestor, a banker, noted, ‘the strike by the bank employees themselves will make it difficult for the junta to manage money’ (Walker, Citation2021).

On a more symbolic level, central banks matter because they tend to be seen as beacons of sound economic policy. This role transcends monetary policy in a narrow sense: central bank bureaucrats have deeper insights into the structure of regime finance than other elite actors, giving them potential political leverage over autocrats. Central bankers tend to be highly educated and well-connected both domestically and internationally (e.g. Johnson, Citation2016). As such, bankers who criticize authoritarian governments on economic policy often have high credibility. Arguably, this is one reason why protesters in Myanmar approached the central bank directly. In the aftermath of the protests, the military government had trouble maintaining the banking system and upholding international financial ties (Radio Free Asia, Citation2021; Minami, Citation2021). Protests outside central banks have similarly occurred in many other authoritarian countries, including Bahrain, Armenia, and Iran (e.g. Radio Farda, Citation2020)

When central bankers critique the government or even join in public protests, this can threaten a government’s legitimacy. Central bank elites do not just manage monetary policy, but it is common for them to comment on government policy more broadly, including fiscal policy and budget decisions (e.g. Moser-Boehm, Citation2006). In a particular authoritarian context, this can be seen in the recent conflict between Turkey’s President Erdogan and central bank governor Naci Agbal, who was dismissed after openly investigating misconduct by the former finance minister, who also happened to be Erdogan’s son-in-law (Coskun & Spicer, Citation2021).

An independent central bank can become more vocal in ‘calling out’ bad economic policy and publicly critiquing the government over time, which can in turn strengthen political opposition and facilitate opposition coordination (e.g. Fernández-Alberto, Citation2015). Nominal CBI can therefore increase the likelihood of political dissent in several ways. First, bankers may feel empowered to speak more openly against the government and may try to leverage their formal independence to increase their de facto autonomy, essentially competing with autocrats over monetary policy autonomy. Even initially loyal central bankers may seek to enhance their de facto policy-making autonomy in the long-run.

In some cases, bankers themselves side with political challengers or opposition members. For example, in 1998, several high-ranking bank officials were forced to resign in Malaysia after finance minister Anwar Ibrahim began to challenge Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad. The fired bankers ‘were widely seen as allies’ of Ibrahim (Agence-France Presse Hong Kong, Citation1998a), who himself was subsequently imprisoned as part of Mahathir’s consolidation of power (e.g. Slater, Citation2003). Mahathir himself acknowledged that political arguments had led to the central bank resignations (Agence-France Presse Hong Kong, Citation1998b).

In the eyes of autocrats, even firing a central bank governor is not always sufficient for eliminating them as a potential threat. This explains why some central bank governors are arrested or disappeared, such as Turkmenistan’s former governor Seitbai Kandimov (Prove They Are Alive! Campaign, Citation2017; Saidazimova, Citation2007). Furthermore, although disloyal bankers will likely be removed from office, frequent removal of central bank executives can cast a negative light on authoritarian governments by portraying a sense of chaotic policymaking and political instability.Footnote10 In addition, politically motivated dismissals may be subject to greater public scrutiny where CBI is high.

For all these reasons, CBI can be risky for nondemocratic governments fearing protests and opposition challenges. As a result, autocratic leaders concerned about compliance may prefer a more dependent central bank ex ante, allowing them to monitor central bankers’ training and professional activities more closely. Rules facilitating the hiring and firing of governors can signal to them that they must comply carefully with government wishes if they want to remain in office, thereby possibly preventing high-profile dismissals and arrests, but also providing autocrats with legitimate, legal avenues for firing these powerful actors in case of non-compliance. Overall, keeping central banks dependent makes it clear to domestic audiences that these institutions operate at the discretion of autocrats, which may limit dissent.

2. Central banks and regime funding

In addition, it is well known that central banks support regime funding. Autocrats need to finance militaries, fund repression, and distribute patronage to stay in power, and they frequently draw on central banks in doing so. In states such as Argentina and Myanmar, central banks have been known to directly support the regime’s repressive apparatus (e.g. Central Banking, Citation2015).Footnote11 The central bank’s role in regime funding can be open and direct, i.e. through lending, or more clandestine channels.Footnote12 Although the financial ties between central banks and autocratic governments are too complex to explore in this paper, there are a few key considerations when it comes to the choice of legal CBI.

First, many autocrats prefer legal channels in utilizing central banks. Increasing CBI can disrupt the patronage flows that autocratic parties rely on for their survival, e.g. by decreasing fiscal spending (Bodea et al., Citation2019). Other funding mechanisms include lending to the government and supporting state-owned enterprises that employ regime supporters, such as in China and Vietnam (e.g. see Channel News Asia, Citation2020), and the supervision of commercial banks that are vehicles for patronage and regime support (e.g. Claessens, 1999). Central banks are thus a crucial part of the autocratic government apparatus.

Central banks also support regimes through informal clandestine activities, direct theft, or funding of repression. Thus, they constitute a key element in the ‘sticks and carrots’ autocrats use to induce political compliance by targeting opposition financing. For example, the Nigerian central bank recently froze bank accounts of activists who had protested against police brutality (Clowes, Citation2020). Other autocrats have stolen directly from the central bank or used it in money laundering. In Angola, for instance, the son of President dos Santos was accused of transferring 500 million dollars from the central bank into private accounts (Sharife & Anderson, Citation2020). In Iraq, Saddam Hussein withdrew up to one billion dollars from the central bank shortly before the start of US airstrikes (BBC News, Citation2003). In these regimes, autocrats may prefer central bank leadership that turns a blind eye to these activities or even directly supports clandestine transactions.

These concerns about regime funding can motivate autocrats to keep central banks legally dependent. While some prefer weak central banks to facilitate theft, others rely extensively on patronage and may prefer to keep central banks dependent to maintain these patronage flows. Either way, central bank reform can be risky. A nominally independent bank may gain sufficient de facto autonomy to disrupt regime finance, whereas a dependent central bank signals that the government is firmly in control of regime finance and distribution of rents. In the next section, I discuss how autocrats assess these costs and benefits of CBI under different levels of personalism.

Personalism and de jure CBI: the mechanism

How, then, do autocrats assess the relative costs and benefits of CBI? I argue that the interplay of two conditions makes CBI potentially costly: (1) Bite: the potential effectiveness of legal independence, and (2) Threat: the political risk associated with independence.

First, reforms granting CBI are more likely to be effective in certain autocracies. In particular, highly institutionalized non-personalist autocracies have better policymaking capacity and more checks and balances in place. In these states, there is a greater likelihood that formal independence will result in actual autonomy. In contrast, because of the power concentration in highly personalist autocracies, CBI lacks credibility in these states and leaders have few incentives to reform central banks. Thus, the weak institutional environment under personalism provides a ceiling to the bite that CBI reforms can have. Footnote13

In contrast, CBI does have the potential to constrain autocrats in nonpersonalist autocracies, where leaders do not hold as much power. Nonpersonalist autocracies tend to have stronger policymaking capacity, more actors involved in policymaking, and existing institutions, that can potentially reinforce legal CBI and increase its effectiveness, such as parties and legislatures,.Footnote14 As a result, CBI has more bite in nonpersonalist compared to highly personalist regimes.

Yet such ‘bite’ is potentially problematic for autocratic governments if it is associated with increased political risks. As I argued above, central banks can undermine autocratic rule through several mechanisms, including through information provision, public dissent, disruptions of regime funding, and through their role in banking supervision. Because of this, self-interested autocrats are concerned about how much to delegate to independent central banks. Where bite and threat coincide, autocrats prefer low levels of CBI, because the threats tend to be more immediate than future economic benefits. This is particularly the case in autocracies with low levels of personalism.

Only in states where CBI has sufficient bite and potential to constrain autocrats, but where the threats associated with CBI are not too great, will autocratic governments be willing to implement legal CBI. In other words, I suggest that autocrats need to feel at least somewhat secure to reform central banks. States with intermediate levels of personalism are most likely to meet these requirements and consequently also have the highest levels of CBI. In explaining my argument, I will first consider the extremes of very high and very low personalism, and then derive implications for states with intermediate personalism.

High personalism

In highly personalist autocracies, CBI is associated with few political risks to leaders. Personalist autocrats are less concerned about central bankers gaining de facto autonomy since they have a variety of repressive mechanisms available to reduce the threat of an independent central bank. Yet because CBI also has fewer potential benefits in these states, personalist autocrats are unlikely to implement CBI.

Given their extreme concentration of power, highly personalist autocracies are less likely to implement institutional reforms or seek power-sharing arrangements. Since leaders can undermine or reverse laws at any point, CBI lacks effectiveness and credibility in the eyes of audiences. Similarly, since they depend less on coalition-building for their political survival, the potential public benefits of CBI are less important to personalist leaders. Instead, they are more likely to rule by repression and intimidation than attention to sound monetary policy.

Highly personalist autocrats also frequently rely on extraction, including direct theft from central banks as discussed above (e.g. Winthrobe, Citation1990). Again, the ability to steal directly from central banks reduces incentives to implement complex institutional reforms and incentivizes autocrats to keep central banks weak. Instead, these autocrats often create personality cults that place them at the center of all policymaking. Even nominal CBI is squarely at odds with such notions of extraction and personalized decision-making.

In addition, strong power concentration in highly personalist autocracies also makes it easier for foreign investors to observe that dictators retain policymaking control even where central banks are nominally independent. As a result, CBI reforms in these states tend to be less effective, having less credibility in the eyes of investors and foreign audiences. This reduced credibility again reduces the size of the potential benefits of CBI and makes central bank reforms less attractive to personalist autocrats.

For all these reasons, under personalism, we may expect at most cheap partial reforms as a form of window dressing, but never the complex and extensive reforms that generally accompany CBI in democracies. Moreover, even partial reforms may be quickly reversed in times when autocrats seek to further consolidate their political power.

This dynamic is apparent in Angola, where long-term President dos Santos was able to further consolidate his power in 2010 by passing a new constitution. (Dugger, Citation2010) This shift towards increased personalism was accompanied by legislation decreasing CBI. In particular, the country’s new constitution contains provisions that formally weaken the authority of the central bank to the extent that ‘Central […] bank activities shall be the exclusive responsibility of the state’ (Constitute Project, Citation2010). It is reasonable to interpret these reforms as a way for dos Santos to signal to domestic audiences that he is firmly in charge of all aspects of politics, including monetary policy, demonstrating his increased power concentration in order to discourage challenges to his regime. While dos Santos had tolerated partial independence prior to 2010, the ease with which he reversed existing central bank legislation illustrates that he saw little value in CBI.

Low personalism

In contrast, nonpersonalist leaders are not strong enough to rule alone and therefore depend on successful coalition-building for their survival. As a result, nonpersonalist autocracies tend to have greater checks and balances, stronger policymaking capacity, and more actors involved in policymaking. These states often have existing power-sharing institutions such as strong parties or legislatures, which can potentially reinforce legal CBI and increase its effectiveness. This in turn increases the potential gains from CBI, because it will be more credible in the eyes of investors. Autocracies with larger ruling coalitions are also associated with greater public goods provision, which again increases the potential benefits of CBI in these states (e.g. Bueno de Mesquita et al., Citation2003).

Despite this greater bite of CBI in nonpersonalist regimes, I argue that nonpersonalist autocracies also prefer to keep central banks dependent. While existing institutions can potentially reinforce legal CBI, bite can also pose an obstacle to CBI reform by creating political risks and posing a threat to autocratic survival. This threat can be more immediate than any future economic benefits of CBI. Thus, recent work suggests that power-sharing is a ‘double-edged sword’ (Meng et al., Citation2022, p. 15), because institutions can turn against leaders: ‘[c]hallengers can leverage initially small institutional concessions to create a slippery slope whereby they accrue more privileges than the ruler originally intended.’ Meng et al call these the ‘countervailing commitment and threat-enhancing effects’ of power-sharing. (ibid, 2022)

Thus, in more institutionalized, nonpersonalist states, there will be more opportunities for central bankers to translate legal independence into de facto autonomy gains. As a result, central bankers may become more empowered to speak out openly against a government, or support opposition groups in states where CBI has more bite.Footnote15 The greater number of actors involved in policymaking also creates increased opportunities for political challenges and dissent.

In addition, CBI can also enhance threat in nonpersonalist autocracies by disrupting existing patronage structures, as these states have broader elite coalitions that they have to fund and are more likely to depend on legal funding mechanisms that involve central banks (e.g. Bodea et al., Citation2019; Magaloni & Kricheli, Citation2010). Autocracies only delegate as much as they must to maximize regime survival, and states with strong power-sharing institutions such as parties may be hesitant to strengthen additional institutions, i.e. central banks, that could disrupt preexisting power-sharing arrangements.

Consequently, where autocrats view central banks as potentially destabilizing to their rule, they prefer to keep them legally dependent. Low levels of CBI clearly convey that monetary policymaking is firmly in the hands of the government. This can help autocrats signal their control over economic policy to political elites inside the central bank as well as to the opposition. In doing so, central bank legislation shapes actors’ expectations about economic policy, puts an upper bound on the extent to which bankers can increase their de facto policymaking autonomy, and ensures that bankers and other political actors comply with the wishes of the authoritarian government. It also permits autocrats to control central banks through legal and legitimate channels as opposed to methods of violent repression that are more prominent in personalist states.

Similarly, while CBI can increase monetary policy transparency, a dependent central bank can signal that a government is in control of regime finance and distribution of rents. Central bank dependence can therefore be a costly signal to domestic audiences in authoritarian states, communicating that the government ‘holds the purse strings.’ This is particularly relevant when an authoritarian government’s hold on power is uncertain or likely to be challenged.

These arguments can explain why nonpersonalist autocracies such as Vietnam have been hesitant to grant their central bank legal independence despite overall strong institutionalization. Similarly, China has made it very clear that their central bank is politically dependent on the government, and that it does not plan to increase the bank’s legal independence. In China’s case, officials often frame this dependence in terms of policymaking efficiency. For instance, in a 2014 interview, the governor of the People’s Bank of China has frequently voiced his support for keeping the central bank dependent (Wall Street Journal, Citation2015).Footnote16

Intermediate personalism

Although states with intermediate personalism are a highly diverse group with significant differences, they share some important features with respect to CBI. In particular, they share a leader who holds significant political power relative to other elite groups, such as a party or monarchic family, but not enough power to rule alone. Typically, autocrats in these states seek to further consolidate their political power with respect to other elites, but they may be balanced by other strong elites within the regime party or ruling family. These elites will seek to place checks and balances on the leader to prevent him from getting too powerful.

Because of these dynamics, leaders and elites can have conflicting economic incentives under intermediate personalism. Autocrats in states with intermediate personalism cannot be concerned purely with provision of private goods. In contrast to highly personalist autocrats, their ruling coalition is large enough that some combination of public and private goods is required. This raises the potential benefits of CBI. Yet moderately powerful autocratic leaders also have incentives to extract private rents and increase their means of extraction in the long run to increase their power. Elites, on the other hand, have incentives to increase economic transparency and limit the leader’s ability to extract rents. Yet these elites are also motived to use economic benefits to increase their own relative power with respect to leaders.

Because of these intra-elite bargaining dynamics, states with intermediate personalism can potentially benefit from power-sharing arrangements via central banks. Power-sharing institutions place formal constraints on autocratic leaders, making it more difficult to renege on promises. They also provide institutional mechanisms for distributing economic benefits between a ruler and elites and offer information about the size of available spoils (e.g. Boix & Svolik, Citation2013; Magaloni, Citation2006, Citation2008). Thus, CBI could allow elites to place checks on a leader and limit his ability to extract private rents. In turn, autocratic leaders in states with intermediate personalism may want to signal that they will work with elites and share economic benefits.

On the other hand, from the point of view of leaders, delegation to central banks may also be attractive because it can place some constraints on elite spending. Autocrats may worry that direct access to central bank funding will further empower parties and other elites in the future. Thus, many states with intermediate levels of personalism, such as Morocco, still hold elections and have the potential for political budget cycles and large-scale patronage distributions. In this situation, power-sharing via an institution outside of parties or legislatures may be attractive. An independent central bank can, at least in principle, limit political business cycles and reign in party spending.

Yet as Moser argued in an early paper, CBI can only be effective when there are ‘some costs of withdrawing the independence.’ (Moser, Citation1999, p. 1571) While the bite of CBI is somewhat diminished in states with intermediate personalism, the potential effectiveness of CBI is still significantly higher than in fully personalist regimes, and CBI does not lack a priori credibility as in personalist autocracies.Footnote17 This means that there is a potential for CBI to be associated with real delegation and longer-term economic benefits.

While states with intermediate personalism may still be vulnerable to some of the threats of CBI, including dissent and limitations to regime funding, there are reasons to believe these threats are reduced compared to nonpersonalist autocracies and may be outweighed by the benefits of CBI. Since there is a higher chance of conflicting economic preferences in these states, the potential economic constraints and increased transparency of CBI may be perceived as more beneficial than harmful in these states. More personalist leaders also often have relatively long time horizons and are concerned with attracting foreign investment, and thus may seek to gain the potential economic and political benefits of CBI. Lastly, political coalitions in states with intermediate personalism tend to be smaller than in nonpersonalist regimes, somewhat diminishing the potential threats of dissent.

To sum up, states with intermediate personalism have a number of potential benefits from delegating to independent central banks. CBI can both place limitations on patronage through parties, and at the same time place limitations on direct theft via dictators and signal that autocrats are willing to tie their hands. CBI also increases information about economic policy, potentially making it more difficult for either group to gain sole control over regime finance.

One example of this is the National Bank of Kazakhstan (NBK), which adopted a price stabilization mandate and has enjoyed legal independence following reforms in the early 2000s. In contrast to other autocrats, President Nazarbayev encouraged NBK leaders to seek professional training abroad, an indication that he did not feel threatened by CBI. As Johnson and others have argued, the bank’s independence and professionalization have helped Kazakhstan build legitimacy abroad and strengthen the domestic economy without undermining autocratic rule (Johnson, Citation2016; Schatz, Citation2006). Similarly, in early 1990s Peru, central bank reforms were part of a legitimation strategy by President Alberto Fujimori that centered around economic development.

In conclusion, based on the described mechanisms, I expect the relationship between personalism and CBI to follow an inverted U-shape.

Empirical Implication (Personalism): There is a nonlinear relationship between personalism and CBI in nondemocracies: nondemocratic regimes with low levels of personalism and those with very high levels of personalism tend to have lower levels of CBI. Nondemocracies with intermediate levels of personalism have the highest level of CBI.

In autocracies with low personalism, CBI tends to be low because autocrats view it as potentially threatening. As a result, it is precisely the potential effectiveness of central bank autonomy that undermines the prospect of reform. As personalism rises, the costs of central bank reform decline. However, highly personalist autocrats discount the benefits of nominally independent central banks. As a result, it is the states with middling levels of personalism, where the costs are moderate, but the benefits are still significant, that are most likely to choose legally autonomous central banks. This theoretical mechanism is summarized in .

Research design

Data and variables

Dependent variable

The dependent variable, weighted CBI, is an overall measure of de jure CBI.Footnote18 The most widely used measure of CBI is by Cukierman et al. (Citation1992), who calculate a weighted average of sixteen measures, ranging from policy formation to limitations on lending to the government. The index ranges between 0 and 1, where 1 represents the highest degree of independence. An updated version by Garriga (Citation2016) now includes yearly data on CBI for most states between 1970 and 2012, including nondemocracies that were previously missing from the index.Footnote19

Independent variables

The data is in country-year format. The sample consists of countries that were nondemocratic, as defined by a polity2 score of 5 or less, between 1970–2012 (Marshall et al., Citation2017). A country is in the sample only for those years in which it is nondemocratic, resulting in a total of 2935 observations. For the key independent variable, I use data by Geddes et al. (Citation2018) to measure the degree of personalism within autocracies, where Personalism is a continuous variable that ranges from 0 to 1, with 1 indicating the highest degree of personalism. One advantage of the continuous personalism measure, compared to the earlier Geddes et al. (Citation2014) personalism dummy, is that the continuous measure has within-country variation whereas the dummy had primarily between-country variation. Approximately 1/3 of the variation in personalism is within-country (Geddes et al., Citation2018).

I expect there to be a nonlinear, inverted u-shaped relationship between personalism and CBI in nondemocracies. To model this U-shaped relationship, I also include a squared Personalism variable in the regression analysis. I expect the coefficient on the personalism variable to be positive, indicating that higher levels of personalism tend to have higher CBI, but the squared term to be negative, suggesting that the positive effect of personalism on CBI decreases for higher values of personalism.

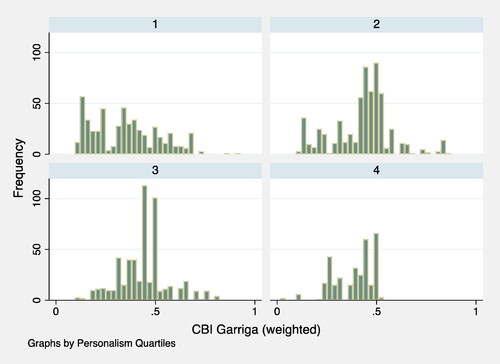

To gain an initial sense of the data, Table A1 in the Appendix, Supplementary materials summarizes average values of CBI for different regimes. Without controlling for confounding factors, differences in CBI are apparent across regime types: The mean CBI across all democracies is 0.52 and median is 0.48; for nondemocracies, the average is 0.41. This difference is highly statistically significant. Consistent with my theoretical argument, median CBI is 0.39 for highly personalist regimes and 0.35 for regimes with low personalism, but for intermediate quartiles of personalism, the median values are 0.43 and 0.44. Notably, this is still lower than the median for democracies, which suggests that autocracy has a negative impact on CBI overall. Again, all these differences in mean are highly statistically significant based on a t-test.Footnote20 In addition, it is also notable that there are no highly personalist autocracies that have reformed central banks past a CBI of 0.52, whereas there is more CBI variation in all other autocracies, as can be seen in . This supports the argument that highly personalist autocrats may see little value in extensive central bank reform or that they lack the capacity to do so.

Table 1. Summary statistics.

I also include several control variables frequently associated with CBI in the existing literature. First, logged GDP and GDP per capita (from Penn World Tables) are included since poorer countries may be more reliant on central bank lending and may be less willing to grant CBI (following e.g. Bodea & Hicks, Citation2015). In addition, because of the relationship between fixed exchange rates and CBI discussed earlier, I include a dummy variable for a fixed exchange rate regime based on the IMF classification (Ilzetzki et al., Citation2019). In Model 3, I control for additional confounding factors by including dummy variables for whether there is a regional central bank, Regional, which would remove control over CBI from national governments, and for the average CBI of a country’s neighbors to assess possible diffusion effects (see Bodea & Hicks, Citation2015), since states that border countries with more independent central banks should also be more likely to adopt CBI. In addition, countries that have experienced high inflation may be more likely to reform central banks, since CBI is linked to lower inflation. (Cukierman, Citation1994) Although it is not clear to what extent this mechanism holds in nondemocracies, I include also include an inflation variable (measured as annual percentage, from the World Bank).

Because trade openness affects how sensitive inflation is to changes in domestic economic conditions, a country’s trade openness may influence the choice of CBI (see Keefer & Stasavage, Citation2002; Romer, Citation1993). Trade openness may also affect CBI through diffusion processes. For instance, states with greater trade openness may seek to lower inflation and reform CBI to increase their international prestige and attractiveness to investors. (Polillo & Guillén, Citation2005). Therefore, I also include a measure of Trade Openness, measured as the sum of imports and exports over GDP (from the World Development Indicators). By a similar argument, I also include a measure of foreign direct investment (FDI) flows, measured as the log of FDI as a share of GDP. Furthermore, participation in IMF programs is frequently attached to conditionality terms. These conditions can include CBI reform (e.g. Polillo & Guillén, Citation2005) I therefore include a dummy that takes value 1 if a country participated in an IMF program over the past two years (from Romelli, Citation2015).

Lastly, in Model 4, I control for other institutional factors that may influence choice of CBI. In particular, I include measures of whether the country holds regular executive and legislative elections (from Cheibub et al., Citation2010). Recent research suggests that political business cycles exist in autocracies and that, similarly to their democratic counterparts, autocrats manipulate economic policy prior to elections (e.g. Higashijima, Citation2016). Thus, the presence of elections may influence the likelihood of CBI reform, although the direction of the effect is not clear for nondemocracies.Footnote21 I also control for the presence of opposition parties, since coalitional conflicts are associated with CBI reforms in democratic states (e.g. Bernhard, Citation1998), and I include a dummy variable for whether the autocratic government is communist, since we would expect communist states to have more dependent central banks.

The empirical models use pooled ordinary least squares (OLS) with panel-corrected standard errors.Footnote22 All independent variables are lagged.Footnote23 All models also include year fixed effects in order to account for temporal effects. Country fixed effects are less appropriate here, given that some countries do not vary in personalism over time. As a result, including country fixed effects would drop these states from the analysis. To avoid this, and to further account for possible geographic effects, I include region dummy variables as an alternative. Descriptive statistics are presented in .

Empirical results and discussion

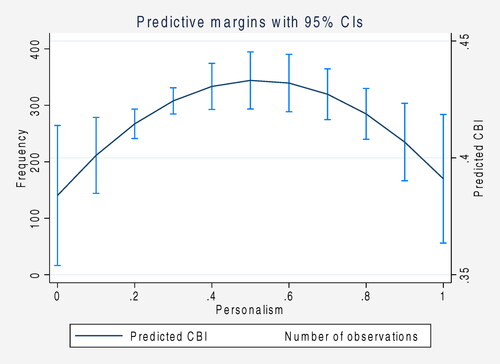

presents my empirical results. Model 1 analyzes the basic nonlinear relationship between personalism and weighted CBI. Model 2 includes basic economic controls, and Models 3 and 4 respectively add further control economic and political control variables. The results generally confirm my hypotheses: First, the coefficient on personalism is positive and significant. The squared term is negative and significant, suggesting the inverted U-shaped relationship hypothesized.

Table 2. Main results: effect of personalism on CBI.

To illustrate the size of the effect of personalism on CBI, plots the predicted quadratic effect of personalism on CBI (based on Model 3). For regimes with personalism scores of 0, predicted nominal CBI is 0.38. Predicted CBI then increases to 0.43 for regimes with intermediate levels of personalism of 0.5, and then declines again. The most personalist autocracies have a predicted CBI of 0.39, which is similar to nonpersonalist regimes. Thus, predicted CBI is 13 percent higher for states with intermediate personalism compared to personalist and nonpersonalist regimes. While weighted CBI is somewhat difficult to interpret, this difference in predicted CBI corresponds to significant CBI reforms. For example, a reform that would provide the central bank board with sole authority to appoint the central bank governor, removing this authority from the executive branch, would lead to an approx. 0.037 increase in CBI. Footnote24

These results support my theoretical argument about the nonlinear relationship between CBI and personalism. Again, although autocracies with intermediate personalism have notably higher CBI, it is still lower than the average democracy.

Across all models, higher GDP is associated with small decreases in independence, and no effect of per capita GDP on CBI. The effect of trade openness on CBI is significant, but again very small in size, and the presence of a fixed exchange rate is associated with lower levels of CBI. As expected, states whose neighbors have independent central banks also have significantly higher CBI. This supports the argument that diffusion plays a role in the spread of CBI. Similarly, the presence of a regional central bank is associated with greater CBI, suggesting that regional oversight is beneficial to CBI in nondemocracies. I do not find a significant effect of inflation, trade openness, or IMF programs on CBI, whereas FDI is associated with greater CBI.

Furthermore, the regular legislative and executive elections as well as opposition parties are strongly associated with lower CBI under autocracy. This suggests that while elections and opposition presence may impact CBI under autocracy, autocrats behave differently from democratic leaders, in the sense that they are less willing to give up control over monetary policy to address time inconsistency problems. Again, this could be due to the fact that autocrats view CBI as a potential existential threat to their rule. Lastly, as expected, states with communist leaders tend to have lower CBI, likely due to their history of strong state intervention.

Overall, the fact that several of the economic variables in the analysis are not statistically significant, combined with the strong effects of most of the political variables, suggests that domestic political factors may play a greater role in the choice of central bank legislation under autocracy than economic factors. As suggested throughout this paper, the choice of CBI may largely be linked to political pressures rather than macroeconomic considerations under autocracy.

Robustness checks

Table A3 in the Appendix, Supplementary materials reports several robustness checks. First, Model 1 includes a measure of veto players (from Henisz, Citation2000) to evaluate the potential alternative argument that lower levels of personalism are associated with more veto players who may block central bank reform. I find that the hypothesized relationship between personalism and CBI holds and that veto players are associated with higher CBI, which confirms arguments by Keefer and Stasavage (Citation2002, Citation2003).Footnote25 I also control for the possibility that the presence of leftist parties account for variation in CBI across nondemocracies. I do not find a relationship between CBI and this this measure. In addition, my main analysis was based on Barbara Geddes’ definition of autocracy. Model 2 presents alternative results using the Polity definition of nondemocracy, where ‘nondemocracy’ includes states with a Polity2 score of 5 or lower. Again, the hypothesized relationship between Personalism and CBI continues to hold in this model.

Furthermore, I also analyze how regime type affects four sub-component measures of CBI, reported in .Footnote26 Based on my arguments, I expect the relationship between personalism and each central bank component measure to be similar as in the aggregate measure and the hypothesized relationship should hold for these subcomponents. In particular, the rules for CEO appointments indicate the relationship between central bank governors and the regime. In states that fear dissent by central bank governors, CEO appointments should be under close control of the government. Overall, the results support my argument, although the effect is weaker for rules regarding policy formulation and central bank lending.

Conclusion

This paper specifies the conditions under which autocracies assign greater autonomy to central banks, arguing that personalism has a nonlinear relationship to CBI, such that states with very low and very high levels of personalism prefer to implement lower CBI compared to those with intermediate personalism. This research contributes to an understanding of variation in CBI across nondemocracies, thereby adding to the existing literature on monetary policy.

My arguments suggest that nondemocratic governments have unique domestic motivations in choosing the level of CBI that are related to their desire for political survival. Where personalism is low, political leaders tend to face greater contestation over political institutions. As a result, they have incentives to signal their control over these institutions to induce compliance with institutional rules and prevent dissent. On the other hand, in states with high levels of personalism, CBI is less risky for leaders, but leaders discount the potential benefits of central bank reforms. Where personalism is at an intermediate level, however, leaders associate fewer threats with CBI, but still expect to gain the potential benefits of reform. As a result, I found these states to have relatively higher levels of CBI. The empirical results supported my theoretical arguments.

By suggesting that domestic political motivations drive central bank legislation in autocracies, my findings contribute to an emergent literature in IPE that highlights the unique concerns of autocratic actors in economic policymaking. A large body of research has shown that institutional constraints can make delegation to central banks more effective in democracies. Yet for autocratic governments, potential threats to survival loom large and informal factors, such as the potential role that central banks play in political protests, can influence monetary policy as much as an autocrat’s formal institutional constraints. Leaders thus weigh the economic benefits of CBI against the risks of empowering bankers to speak out openly against the government or of losing power to an opposition. The consequences of the latter may be more immediate and severe and may therefore outweigh concerns about attracting foreign investment. Overall, paying greater attention to autocracies can enrich our understanding of monetary policymaking more broadly.

My results are also relevant for the study of authoritarian institutions, which has paid less attention to central banks. I have argued that monetary policy is more contentious in autocratic regimes than previous literature acknowledges, and that autocrats pay close attention to central bank legislation. Future research should further analyze the non-formal functions of autocratic central banks, such as protest and regime funding, since these can influence central bank legislation and policymaking under autocracy. Future work should also analyze in greater detail how the choice of CBI relates to other forms of economic policy, such as exchange rates and fiscal policies, as well as examine whether there are ways for nondemocracies to increase the effectiveness and credibility of monetary policy reforms.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (408 KB)Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Jessica Weeks, Jon Pevehouse, Mark Copelovitch, Samantha Vortherms, Hannah Chapman, Anna Oltman, Rachel Jacobs, Rachel Schwartz, Sujeong Shim, and Ana Carolina Garriga, for advice and comments on previous drafts of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Susanne M. Redwood

Susanne Redwood is Assistant Professor of Politics at Montana State University. Her research focuses on international organizations, economic policy, and domestic-international linkages, with a particular emphasis on the role of authoritarian states in the global economy.

Notes

1 In fact, only de facto independence is strongly associated with lower inflation (e.g. Maxfield, Citation1994, p. 557).

2 While earlier work argued that de jure CBI has no positive effect on inflation in nondemocracies, some work has found a small, but significant effect on inflation even in nondemocracies (e.g. Garriga & Rodriguez, Citation2020).

3 32 reforms, about 19%, resulted in decreased CBI.

4 See Figure 1 in Appendix, Supplementary Materials.

5 Existing research suggests that at least some of these benefits hold even if de facto CBI lags behind nominal CBI.

6 The most common measure is a weighted aggregate measure by Cukierman et al. (Citation1992), updated by various scholars.

7 But other research does not find a relationship between transitions and central bank reform. (de Haan & Siermann, Citation1994; de Haan & Van’t Hag, Citation1995; Eijffinger & de Haan, Citation1996)

8 In theory, the credibility problem of central banks applies similarly to exchange rate pegs, because governments can choose to adjust or abandon fixed exchange rates. Thus some nondemocratic governments adopt both or neither. (See Bodea, Citation2010, p. 411) This paper focuses on CBI while controlling for the presence of fixed exchange rates.

9 Another regime classification that has received a lot of attention in the literature is “competitive authoritarianism,” raising the question to what extent intermediate personalism may intersect with competitive authoritarian regimes. Competitive authoritarianism is a particular type of hybrid regime in which “elections are regularly held and are generally free of massive fraud, [but] incumbents routinely abuse state resources, […] harass opposition candidates and their supporters, and in some cases manipulate electoral results.” (Levitsky & Way, Citation2002, p. 53) In contrast, personalism is a broader concept that can be applied to the universe of nondemocracies and that focuses on the relations between leaders and their supporting coalitions rather than on the quality of elections. While some states with middling personalism would fall under competitive authoritarianism, such as Botswana in 2008, the categories do not overlap in many other cases, such as Cameroon, which Levitsky and Way consider competitive authoritarian, but which scores highly on the personalism scale.

10 It is not uncommon for governments to emphasize removal was not for political, but personal reasons, suggesting that dictators are indeed concerned about how removal of governors is perceived.

11 For example, recently declassified documents from Argentina show that the military regime used secret central bank loans to make weapons purchases and build economic ties with other dictatorships (e.g. Veigel, Citation2010, p. 65).

12 Autocrats sometimes go to extreme measures to gain access to central bank finance during war. In a stark example, during the Libyan civil war rebels of the transitional National Council announced that they had founded a rival central bank, funded through reserves stolen by drilling a hole in the vault of the Central Bank of Libya (Raghavan & Grimaldi, Citation2011).

13 This is consistent with existing arguments about democracies that CBI is more effective in states with strong checks and balances (Bagheri & Habibi, Citation1998; Keefer & Stasavage, Citation2002, Citation2003; Moser, Citation1999). Similarly, Bodea et al. (Citation2019) suggest this may be the case for party-based autocracies.

14 I distinguish potential effectiveness or bite from actual, de facto CBI. De facto CBI is very difficult to determine or measure under autocracy. Expectations about bite can shape actors’ political expectations around CBI even if de facto CBI is not known.

15 See also Woo and Conrad (Citation2019), for an argument that authoritarian institutions can both co-opt elites and create new opportunities for dissent.

16 But also see: Moss (Citation2018).

17 There are several reasons to believe that CBI is at least potentially effective in these states. While respect for the rule of law is generally weakened under autocracy, legal effectiveness is a spectrum, and less personalist autocracies may show respect for the rule of law for several reasons. First, greater legal effectiveness can enhance regime legitimacy; secondly, it can place formal constraints on rulers and facilitate power-sharing (see Ginsburg & Moustafa, Citation2008). Less personalist autocrats may not be politically strong enough to fully subvert the rule of law and may show some respect for rule of law to maintain ruling coalition cohesion. For instance, research has found that institutionalized, nonpersonalist autocracies can make more credible commitments to investors not to expropriate them and to respect economic rules (see Gehlbach & Keefer, Citation2011). Furthermore, legal effectiveness can vary strongly by issue area under autocracy. In particular, autocrats may show some respect for economic legislation in hopes of attracting investment, while simultaneously violating human rights (e.g. Ginsburg & Moustafa, Citation2008). Overall, there is reason to believe that legal effectiveness is stronger in less personalist compared to highly personalist autocracies.

18 Results are similar if an unweighted aggregate measure of CBI is used (not reported).

19 The majority of nondemocratic countries did not have modern central banks prior to the 1960s.

20 Although both highly personalist and nonpersonalist autocracies have low CBI, the latter have, on average, the lowest CBI.

21 It may be that, similarly to democracies, electoral autocracies are more likely to reform CBI to solve the time inconsistency problem. But electoral autocracies could also be more hesitant than democracies to give up the ability to manipulate economic conditions prior to elections. Either way, the presence of recent elections may affect the likelihood of central bank reform.

22 The standard errors are clustered by country. Following Beck and Katz (Citation1995), these standard errors perform well in panel data even in the presence of heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation.

23 Except for the presence of a regional central bank, where lagging would not be appropriate, and for the IMF programs variable, an IMF loan within the past two years is included.

24 As a comparison with a developed democracy, states with intermediate personalism are predicted to have approximately the same level of CBI as Japan. Alternatively, worldwide average CBI was approximately 0.38 in the early 1980s and reached about 0.43 ten years later, marking a decade in CBI development.

25 Yet veto player measures tend to be less informative when analyzing nondemocracies, since autocratic veto players may not hold official government positions (e.g. a dictator’s family member). As a result, the veto player measure may be zero even if there are de facto veto players in a regime. This is another reason why the personalism measure is more appropriate for analyzing monetary policy under autocracy.

26 These are (1) legal rules for the appointment of CEO; (2) rules governing the formation of policy objectives; (3) legislation regarding policy formulation; and (4) rules regarding limitations on lending to governments

References

- Adolph, C. A. (2013). Bankers, bureaucrats, and central bank politics: The myth of neutrality. Cambridge University Press

- Agence-France Presse Hong Kong. (1998a). Anonymous central bank official, cited in “Third Malaysian Central Banker Leaves”, August 29, 1998.

- Agence-France Presse Hong Kong. (1998b). “Malaysia: Mahathir Admits Policy Clash with Central Bank”, August 29, 1998.

- Alesina, A., & Summers, L. H. (1993). CBI and macroeconomic performance: Some comparative evidence. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, 25(2), 151–163. https://doi.org/10.2307/2077833

- Bagheri, F., & Habibi, N. (1998). Political institutions and central bank independence: A cross-country analysis. Public Choice, 96(1/2), 187–204. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005055317499

- BBC News. (2003). Saddam ‘took $1bn from Bank’. 6 May 2003. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/middle_east/3004079.stm

- Beck, N., & Katz, J. N. (1995). What to do (and not to do) with time-series cross-section data. American Political Science Review, 89(3), 634–647.

- Bernhard, W. (1998). A political explanation of variations in CBI. American Political Science Review, 92(2), 311–327. https://doi.org/10.2307/2585666

- Blaydes, L. (2011). Elections and distributive politics in Mubarak’s Egypt. Cambridge University Press.

- Bodea, C. (2010). Exchange rate regimes and independent central banks: A correlated choice of imperfectly credible institutions. International Organization, 64(3), 411–442. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818310000111

- Bodea, C., Garriga, A. C., & Higashijima, M. (2019). Economic institutions and autocratic breakdown: Monetary constraints and fiscal spending in dominant-party regimes. Journal of Politics, 81(2), 601–615.

- Bodea, C., & Hicks, R. (2015). Price stability and CBI: Discipline, credibility, and democratic institutions. International Organization, 69(1), 35–61. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818314000277

- Boix, C., & Svolik, M. (2013). The foundations of limited authoritarian government: Institutions, commitment, and power-sharing in dictatorships. The Journal of Politics, 75(2), 300–316. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381613000029

- Boylan, D. M. (1998). Preemptive strike: Central bank reform in Chile's transition from authoritarian rule. Comparative Politics, 30(4), 443–462. https://doi.org/10.2307/422333

- Boylan, D. M. (2001). Defusing democracy: Central Bank autonomy and the transition from authoritarian rule. University of Michigan Press.

- Braun, B., Krampf, A., & Murau, S. (2020). Financial globalization as positive integration: Monetary technocrats and the Eurodollar market in the 1970s. Review of International Political Economy, 28(4), 794–819. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2020.1740291

- Broz, J. L. (2002). Political system transparency and monetary commitment regimes. International Organization, 56(4), 861–887. https://doi.org/10.1162/002081802760403801

- Bueno de Mesquita, B. R., A. Smith, R. M. Siverson, and J.D. Morrow. (2003). The logic of political survival. MIT Press.

- Central Banking. (2015). Central Bank of Argentina publishes secret minutes from last dictatorship. 8 April 2015. https://www.centralbanking.com/central-banks/governance/2403223/central-bank-of-argentina-publishes-secret-minutes-from-last-dictatorship

- Channel News Asia. (2020). China central bank tries to soothe market nerves after SOE debt shock. 16 November 2020. https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/business/china-central-bank-120-billion-yuan-state-owned-enterprises-debt-13566848

- Cheibub, J. A., Gandhi, J., & Vreeland, J. R. (2010). Democracy and dictatorship revisited. Public Choice, 143(1–2), 67–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-009-9491-2

- Clowes, W. (2020). Nigerian court says central bank can block protest accounts. Bloomberg, 7 November 2020. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-11-07/nigeria-central-bank-gets-court-order-to-block-protest-accounts

- Constitute Project. (2010). Angola’s constitution of 2010. Available at: https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Angola_2010.pdf?lang=en

- Coskun, O., & Spicer, J. (2021). ‘The Last Straw’: Why an Irked Erdogan fired Turkey’s Central Bank Chief. Reuters, 31 March 2021. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-turkey-cenbank/the-last-straw-why-an-irked-erdogan-fired-turkeys-central-bank-chief-idUSKBN2BN1I1

- Crowe, C., & Meade, E. E. (2008). CBI and transparency: Evolution and effectiveness. IMF Working paper WP/08/119. https://doi.org/10.5089/9781451869798.001

- Crowe, C. (2008). Goal independent central banks: Why politicians decide to delegate. European Journal of Political Economy, 24(4), 748–762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2008.05.002

- Cukierman, A. (1994). Central bank independence and monetary control. The Economic Journal 104(427), 1437–1448. https://doi.org/10.2307/2235462

- Cukierman, A., & Webb, S. B. (1995). Political influence on the central bank: International evidence. The World Bank Economic Review, 9(3), 397–423. https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/9.3.397

- Cukierman, A., Web, S. B., & Neyapti, B. (1992). Measuring the independence of central banks and its effect on policy outcomes. The World Bank Economic Review, 6(3), 353–398. https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/6.3.353

- de Haan, J., and C. L. J. Siermann. (1996). Central bank independence, inflation, and political instability in developing countries. Journal of Policy Reform 1(2), 135–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/13841289608523360

- de Haan, J., and G.-J. Van't Hag. (1995). Variation in central bank independence across countries: some provisional empirical evidence. Public Choice 85(3-4), 335–351. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01048203

- Dugger, C. W. (2010, January 22). Angola moves to make president stronger. New York Times.

- Eijffinger, S. C., & de Haan, J. (1996). The political economy of CBI. Special Papers in International Economics, 19.

- Fernández-Alberto, J. (2015). The politics of CBI. Annual Review of Political Science, 18, 217–237.

- Financial Tribune. (2016). Bill proposes enhanced central bank autonomy. August 30, 2016. https://financialtribune.com/articles/economy-business-and-markets/48752/bill-proposes-enhanced-central-bank-autonomy

- Financial Tribune. (2019). Banking bill ratified amid Iran’s CB concerns. December 17, 2019. https://financialtribune.com/articles/business-and-markets/101265/banking-bill-ratified-amid-irans-cb-concerns

- Gandhi, J. (2008). Dictatorial institutions and their impact on economic growth. European Journal of Sociology, 49(1), 3–30. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003975608000015

- Gandhi, J., & Lust-Okar, E. (2009). Elections under authoritarianism. Annual Review of Political Science, 12(1), 403–422. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.11.060106.095434

- Garriga, A. C. (2010). Determinants of CBI in developing countries: A two-level theory [Doctoral Dissertation].

- Garriga, A. C. (2016). CBI in the world: A new dataset. International Interactions, 42(5), 849–868. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050629.2016.1188813

- Garriga, A. C., & Rodriguez, C. M. (2020). More effective than we thought: CBI and inflation in developing countries. Economic Modeling, 85, 78–105.

- Geddes, B., J. Wright, and E. Frantz. (2014). Autocratic breakdown and regime transitions: A new data set. Perspectives on Politics 12(2), 313–331. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592714000851

- Geddes, B., Wright, J., & Frantz, E. (2018). How dictatorships work. Cambridge University Press.

- Gehlbach, S., & Keefer, P. (2011). Investment without democracy: Ruling-party institutionalization and credible commitment in autocracies. Journal of Comparative Economics, 39(2), 123–139.

- Ginsburg, T., & Moustafa, T. (2008). Rule by law: The politics of courts in authoritarian regimes. Cambridge University Press.