Abstract

This article asks how Germany could have pursued a far-reaching ‘National Industrial Strategy 2030’ despite the fierce opposition of German industry. To resolve this puzzle—which realist-inspired and institutionalist analyses struggle with—it deploys a critical state theory attuned to the uneven and combined development of global capitalism. The twin challenge of China catching up and the US forging ahead has not only prompted German officials to develop a ‘defensive-mercantilist’ response; new qualitative and quantitative evidence indicates that it has also deepened conflicts within Germany’s export industry. Small and large firms are divided over how to respond to the growing lead of US capital in the digital economy, and its major sectors have experienced Chinese inroads into high-tech manufacturing differently. I argue that the German state was/is able to advance its industrial strategy insofar as it reconciles these divergent interests. First, it has offered laxer EU cartel rules to big business and enhanced protection from digital oligopolies to the Mittelstand, in exchange for tighter foreign direct investment controls. And second, I suggest that it could win over the chemical and electrical industry, through selective state subsidies, to its plans to re-shore transnational value chains in the name of ‘technological sovereignty’.

Introduction

A global manufacturing powerhouse and world-leading exporter, Germany has for decades been held to be firmly committed to open markets and resolutely opposed to state intervention (e.g. Katzenstein, Citation1977: 900; Abelshauser, Citation2016: 12–14). And yet, in February 2019, the economics ministry startled many when it unveiled an ambitious and deeply controversial ‘National Industrial Strategy 2030’ (NIS 2030).Footnote1 To preserve Germany’s social market economy in a world transformed by new technologies, a rapidly rising China, and a protectionist US, the NIS 2030 proposed that the state invest in strategic growth sectors, foster national champions big enough to withstand global competition, protect flagship companies from unwanted foreign takeovers, and re-shore global value chains to defend its technological sovereignty (Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Energie [BMWi, Citation2019a; Citation2019b).

There are three reasons for why the NIS 2030—an invaluable because publicly available instance of major policy deliberation—calls for sustained attention within International Political Economy (IPE) (the seminal study is Schneider, Citation2020; see also Alami & Dixon, Citation2020: 8–9). First, it is hotly debated within policy circles as initiating a ‘paradigm shift’ towards a far more proactive, protectionist, and inward orientation of German economic policy that has continued under the Scholz government (Bofinger, Citation2019; Zettelmeyer, Citation2019). Second, it feeds into a wider dynamic that numerous scholars and practitioners characterize as a ‘more visible role of the state across the world capitalist economy’ (Alami & Dixon, Citation2020: 1; van Apeldoorn et al., Citation2012), and that has since been accelerated by the pandemic shock and Western sanctions against Russia. And last, given Germany’s weight within the European Union (EU) and centrality in European value chains (e.g. Stöllinger et al., Citation2018: 31–32), the NIS 2030 has shaped the bloc’s headline initiatives to support its industrial base and competitiveness (European Commission [EC], 2021).

The puzzle addressed in this article is why this once-in-a-generation policy initiative has been advanced despite the organized opposition from German industry. Its lobbies denounced the draft NIS 2030 as antiquated, ill-founded and outright dangerous: it risks abetting global protectionist trends (BDI, Citation2019a: 13), copies the ‘misguided re-nationalisation policies of other countries’ (Löhr, Citation2019), and even amounts to an attack on ‘the foundation of our…economic order’ (Die Familienunternehmer, Citation2019: 3). They subsequently managed, through public statements, counter-drafts and consultations, to water down the final version (Graw, Citation2019: 5; Gersemann, Citation2019; Kaiser, Citation2020). And yet while most media commentators concluded that the NIS 2030, by December 2019, had been reduced to ‘a slip of paper’ (Sauga, Citation2019), the German government has continued to pursue legislative action in several areas identified by the NIS 2030: it has progressively tightened its oversight of foreign direct investment (FDI) to guard against Chinese acquisitions, and consistently pushed for greater discretion in applying EU and national competition rules to target US digital giants, foster inter-corporate alliances, and pour state money into selected growth industries. Industry representatives have repeatedly and vocally objected that this infringes on private property rights and investment decisions and discriminates in favor of specific sectors (e.g. Wirtschaftswoche, Citation2020; Sorge, Citation2021). And yet, they seem unable, or perhaps unwilling, to stop the German government from significantly extending its regulatory reach and toolkit.

This policy outcome is perplexing for any approach that recognises the privileged position of business in capitalist economies (e.g. Lindblom, Citation1977; Przeworski & Wallerstein, Citation1988; Culpepper, Citation2015), and the systemic importance of the export manufacturing sector for the German model in particular (Baccaro & Pontusson, Citation2016). What is needed, therefore, is deeper theoretical reflection, and closer empirical examination, of state-business and intra-corporate dynamics in the conflict over the NIS 2030: what, if any, tensions may lie underneath the seemingly united front of German industry? And what, if any, business sections may yet support the NIS 2030 and the potentially far-reaching reformation of German capitalism it holds out?

To resolve the puzzle of the socially contested and yet progressively enacted NIS 2030, the first part reviews the available IPE approaches. The realist-inspired view that a strong state can simply ‘go it alone’, though parsimonious, does not sit well with Germany’s classification as a political economy co-governed by powerful private stakeholders. A strand of the institutionalist literature describes this German model, including organized business power, to be in distress. But while this might offer an answer as to why German industry failed to stop the NIS 2030, the creeping liberalization it attributes this decline to is at odds with the enhanced role of the state envisioned in the NIS 2030. By contrast, this article takes up insights from the literatures on growth models and the political economy of industrial policy: that divisions among dominant social forces, especially likely in the highly contested area of industrial policy, can be productively managed by states to support independent policy action. It grounds these insights in a version of critical state theory attuned to the uneven and combined development (U&CD) of global capitalism, and it proposes that Germany’s awkward position between a trailblazing US and leapfrogging China may (re)activate tensions within German industry that, if reconciled, allow the German state to pursue the ‘defensive-mercantilist’ approach embodied by the NIS 2030.

The main part of the article uses qualitative and quantitative methods to pursue this line of inquiry. Through a comprehensive review of the position papers of industry lobbies involved in the contest over the NIS 2030, the first section identifies a structural conflict between larger and smaller firms intensified by the combined Sino-American challenge: while the former aims to match the size of US (more so than Chinese) capital, the latter fears it will be swept aside in this concentration process. It argues that the German state has mediated between these contradictory demands placed upon it and expanded its margin of maneuver to pursue several elements of the NIS 2030: it is lobbying hard to ease EU competition rules on behalf of large-scale industry, while promising the Mittelstand to defend its independence and market access against abuses by digital tech from the United States and (to a lesser extent) China. In exchange, the German state has pushed through a tightening of FDI controls for sectors deemed to be ‘critical’ that both groups dislike but have come to tolerate.

The second section asks which of Germany’s four key export sectors may be most likely to break ranks and support the NIS 2030 going forward. It examines whether China’s late industrialization and entry into high-tech manufacturing have been experienced differently by the automotive, chemical and electrical and mechanical engineering sector. It presents new quantitative data which indicates that the chemical and electrical industries are most exposed to Chinese competition globally, and, in the case of the chemical industry, least dependent on China as a sales market. It proposes that they may be more receptive to a defensive-mercantilist course, given stronger competitive pressures from China, and because weaker involvement with China means these sectors would suffer less from Chinese retaliation. The section supports this view with textual evidence that shows that their respective lobbies go furthest in calling for targeted state support and incentives to (re)locate value chains to Europe—core features of the NIS 2030 that Germany’s export industry as a whole has opposed.

The conclusion draws together these empirical findings and suggests that if the German state can continue to mediate between large and small capital while focusing support on the chemical and electrical sector, it can assemble a more stable coalition supporting a ‘defensive-mercantilist’ agenda. It invites further research into the wider reconfiguration of class interests and state strategies in Germany and Europe—in view of the uneven pace and character of world capitalist development, after the pandemic and war on the Ukraine, and beyond the sectoral orientations of the dominant export bloc examined here.

Literature review and theoretical framework

In view of a new industrial revolution dominated by China and the United States, Germany’s NIS 2030 envisions an activist state nurturing infant industries, choosing winners, protecting high-tech sectors, and promoting national and regional value chains. But while this major new role for government in the economy was expressly designed to benefit German industry, its associations mobilized against rather than embraced it. How, then, could the German state have pressed forward with such a far-reaching and contested initiative? This section looks at the available answers within the extant IPE literature on state-business relations in general and in Germany in particular.

The most elegant solution is outlined by realist-inspired approaches that cast the state as ‘an independent, autonomous entity with powers and objectives that are distinct from any particular societal groups’ (Krasner, Citation1977: 641, fn. 11; Zakaria, Citation1998: 35, 38; Skocpol, Citation1985; Mann, Citation1986). From this perspective, we would indeed expect Germany, spurred on by shifts in the global balance of power, to pursue its ‘national interest’ over and against private actors. The NIS 2030, in this view, is a case of the German state ‘going it alone’, and the question becomes solely about what material and institutional resources it has at its disposal. However, the seminal contributions that dwell on this point have identified Germany as a comparatively ‘weak state’—both in terms of the external power it is able to project and in terms of its internal power to dictate economic policy to entrenched private interests (Katzenstein, Citation1977: 900, 904, 912; Katzenstein, Citation1987; Green & Paterson, Citation2005; Streeck, Citation2009: 188).

The institutionalist scholarship on the German political economy might offer a possible solution here. In principle, Germany’s ‘organised capitalism’ is held to be governed by a high degree of institutionalized cooperation between public and private actors, the two principal social partners, and various sectors of the German economy (e.g. Streeck & Yamamura, Citation2001). From this perspective, regulatory reforms of such magnitude as the NIS 2030 would require the consent and collaboration of major stakeholders. At the same time, several scholars in this tradition have stressed that this German model has receded on multiple fronts since the 1990s (Streeck, Citation2009; Rothstein & Schulze-Cleven, Citation2020). Employer associations have lost many of their members (Behrens, Citation2018: 770), business associations are challenged by large firms acting on their own account (Bührer, Citation2017: 72), and the once tightly-knit corporate network—via cross-shareholding, voting blocks, and interlocking directorates—has unraveled (Windolf, Citation2014). Perhaps, then, this could have created a situation in which German business is no longer as united as it used to be, and struggles to organise effectively against unwanted state action?Footnote2

The problem with this particular hypothetical is that it assumes institutional drift—not only as driving the disorganization of German business, but as the general direction of travel for the German political economy (for a critique and modified ‘liberalisation thesis’, see Thelen, Citation2014). A major policy initiative like the NIS 2030, which involves a purposive redesign, and a renovation of state capacities rather than creeping market liberalization, is difficult to square with this overall trend. Whatever we would gain in terms of explaining why German industry is divided, we would lose in terms of explaining why the NIS 2030 came about in the first place.

Rather than rely on institutional erosion, the emerging ‘growth model’ perspective starts from the macroeconomic characteristics to arrive at the business politics of German capitalism (Baccaro & Pontusson, Citation2016; Citation2018; Citation2019; Bohle & Regan, Citation2021). It designates the German political economy as ‘export-led’ and identifies an outwardly oriented manufacturing sector as leading a wider ‘social bloc’ that includes subordinate sectors and class forces. Because export manufacturing is so central to the German economy, this social bloc can claim to represent the ‘national interest’ and enjoys considerable influence over policy (Baccaro & Pontusson, Citation2019: 30).

To be sure, in some respects, this literature magnifies the puzzle: given the structural and direct power attributed to this export bloc, why should it struggle to shut down the NIS 2030? At the same time, the Gramscian-Poulantzasian framing suggests a possible answer. In light of its hegemonic reach across sectoral and class divisions, unwanted policy change would have to spring from cracks in the export bloc—a possibility that Baccaro and Pontusson (Citation2018: 21) allow for and that this article takes up.

The literature on the political economy of industrial policy helps develop this point further. It recognizes industrial strategy as a particularly contentious policy field because the selective character of state interventions in this area is more visible and pronounced (Chang & Andreoni, Citation2020: 336). This literature prepares us for what for Germany’s organized capitalism is an unusually high degree of policy conflict surrounding the NIS 2030. Not only does it help us understand the fierce criticism levelled against the German government by industry lobbies; it also suggests that there may be conflicting business interests underneath it that deserve closer scrutiny. And finally, and most importantly, this literature affords public officials a key role in managing these tensions and assembling political coalitions in support of industrial strategies (Andreoni & Chang, Citation2019: 146).

Conceptually, both the growth model and industrial policy literature connect to critical state theory in so far as the social basis and bias of state action form the common point of departure (Storm, Citation2017: 4, 6; Baccaro & Pontusson, Citation2019: 11). Unlike realist-inspired analyses, this tradition of thought does not presume the state to be fully autonomous but sees it as deeply embedded in complex and conflictive class relations that it must stabilise to sustain itself (e.g. Poulantzas, Citation1978; Jessop, Citation1990; Hirsch, Citation2005; Panitch & Gindin, Citation2012; Brand, Citation2013; Maher, Citation2016; Chasoglou, Citation2019). And unlike pluralist conceptions of state power, critical state theory does not take business to be ‘an interest group like any other’ but to be uniquely influential because it controls the productive resources of society (for this apt quote and a brief summary of this literature, see Culpepper, Citation2015: 392; for a systematic critique, see Offe & Wiesenthal, Citation1980). Because states depend on successful capital accumulation for their material existence and political legitimacy, they are structurally compelled to prioritize capital in its antagonism with labor and over wider social interests, even without direct lobbying (Hirsch, Citation2005: 26). A key problem, and source of the state’s relative independence, is that what capital wants and needs in a given situation is often uncertain and contested even within a dominant social bloc (Hawley, Citation1987: 145). The interest of capital thus needs to be discovered and, in important respects, created through a policy process that routinely solicits business views. This perspective attributes a proactive, though not wholly autonomous, role for the state in organizing a coherent vision out of the fragmented, competing and contradictory capital interests that it frequently encounters (Brand et al., Citation2022: 279–280; Maher, Citation2022: 27–28). Business associations, in this expanded view of state agency, are more than corporate lobbies that act on the state from the outside; they straddle the private and public sphere and serve as key conduits through which the state registers, and then ideally reconciles, conflicts and tensions within the capitalist class (Maher, Citation2022: 19–21). In sum, the hypothesis that we derive from critical state theory is that a contested state initiative like the NIS 2030 can yet succeed even where it faces organized opposition from key business lobbies; insofar as the state picks up on differences and brokers agreements between fractions of capital.

Critical state theory has been criticized for operating with abstract and rigid categories of analysis. On the one hand, the local specificities of actually existing national capitalisms call for a more context-specific treatment than the broad state-theoretical register of ‘class’ and ‘capital’ can deliver (Skocpol, Citation1985: 5). On the other hand, in the context of globalization, it becomes difficult to distinguish a priori between various fractions of capital with supposedly distinct interests as the boundaries between manufacturing and services, industry and finance, other sectors, and internationally and domestically active firms are increasingly blurred (Andreoni & Chang, Citation2019: 146).

To recognize national specificity amidst global integration, this article uses the framework of U&CD, which has recently been brought into the discipline of IPE (Rosenberg & Boyle, Citation2019; Dooley, Citation2019; Antunes de Oliveira, Citation2021; Germann, Citation2021; Rolf, Citation2021) and applied to the question of ‘state capitalism’ (Alami & Dixon, Citation2021). Its basic premise is that capitalist globalization is uneven: it first emerged in one part of the globe, only belatedly spread elsewhere, and gave rise to national varieties that, under pressure to catch up, combined pre-existing with newly imported forms of social organization, knowledge, and technology. The results are hybrid societies with an internal makeup that defies broad-stroke generalizations, and a past and future that diverge from linear conceptions of change. Instead, the interdependence and interaction of diverse, incumbent and late developing, societies not only reshape their domestic trajectories, but also inflects the wider course of capitalist world development in ways that cannot be inferred from a singular logic.

The advantage of bringing U&CD into the remit of critical state theory is twofold. On the one hand, this lens takes national particularities seriously without losing sight of the broader world-historical process of which they are a part. And on the other hand, it replaces a flat-world view of capitalist globalization with a more dynamic notion of world-order change: the global political economy emerges as a complex and open system that continually produces new pressures and opportunities that social and political actors contend with (Germann, Citation2021).

Specifically, the frame of U&CD allows us to investigate the export bloc that characterizes the German political economy without assuming that its interests are uniform and unchanging. And while it recognizes that capitalist globalization has smoothed out differences between capital fractions in some settings and certain respects, we can also expect it—in the current context of a fourth industrial revolution and competing efforts of an incumbent United States and leapfrogging China to dominate it—to introduce new and reopen old lines of division that need to be theoretically grasped and empirically examined.

The remainder of this article applies this frame to the puzzle of the deeply contested and yet progressively enacted NIS 2030. In contrast to the institutionalist scholarship, it approaches this puzzle in class terms; and in contrast to realist-inspired analyses, it starts from the relative rather than absolute autonomy of the state as an organizing force. This take on critical state theory yields the important hypothesis that independent state action is possible when and where dominant social forces are divided and new compromises are forged. The lens of U&CD adds to this a keener sense of how structural changes in the global political economy—specifically the efforts of late developers to catch up and incumbents to stay ahead—may feed through to the domestic scene, introduce splits into dominant social blocs, and alter the policy space available to state elites.

Method and operationalization

In line with its theoretical orientation, this article mobilizes a historical materialist policy analysis (Brand, Citation2013; Brand et al., Citation2022) to examine the socially contested process that led to the formation of the NIS 2030 and its translation into several executive decisions and legislatives initiatives. This approach sees public policy making as ‘embedded in historically-developed complex social relations’ that constitute corridors for state action; and it examines how ‘competing and antagonistic interests of social forces are being organized, articulated and translated into specific policies’ (Brand et al., Citation2022: 280, 284, 292).

Methodologically, this article follows an iterative research process of ‘retroduction’ that combines a deductive and inductive moment and moves continuously between theoretically-guided propositions and empirically-grounded investigation (Brand et al., Citation2022: 287; see also Belfrage & Hauf, Citation2017). Two key propositions frame this inquiry. The first is that, given the power attributed to capital interests and the importance of business associations as vehicles of state-corporate interaction, we should pay close attention to the policy positions taken by major industry lobbies. The second is that we should examine whether the unevenness of capitalist development, and intensifying Sino-American high-tech competition specifically, is (re)activating tensions within German export manufacturing.

As noted above, in a world of production networks that cut across borders and sectors, industries are increasingly intertwined and their interests less clearly delineated (Chang & Andreoni, Citation2020: 340). The solution chosen in this article is to approach the growing complexity of global value chains as a practical problem for industry itself rather than an insurmountable hurdle for the analyst. Business associations, which continue to be institutionally independent from one another and frequently compete for competence, influence and members, still strive to organize and represent the collective interest of their membership base, even as they grapple with its greater heterogeneity and hybridity (Schroeder & Weßels, Citation2017: 19–20). Whether this results in distinctive positions on the NIS 2030 is an open-ended empirical question.

The evidentiary basis for this investigation is gathered, in a first step, through a comprehensive review of the government documents that fed into and flowed from the NIS 2030 as it moved from draft to finish between February and December 2019 as well as the publicly available interventions—press releases, interviews, statements, and position papers—of those industry lobbies that found cause to comment. In addition to this self-selection, the literature on German business associations is consulted for insights on who the major industry lobbies are and whose interest they represent (e.g. Kohler-Koch, Citation2016; Bührer, Citation2017). Within the circle of proactive participants in the debate over the NIS 2030, we can distinguish peak business associations such as the Federation of German Industries (Bundesverband der Deutschen Industrie [BDI]) and, though far less involved, the Association of German Chambers of Industry and Commerce (Deutscher Industrie- und Handelskammertag [DIHK]), from the sectoral associations—most importantly here the chemical (Verband der Chemischen Industrie [VCI]), electrical (Zentralverband Elektrotechnik- und Elektronikindustrie), mechanical engineering (Verband Deutscher Maschinen- und Anlagebau [VDMA]) and automotive (Verband der Automobilindustrie [VDA]) industry associations—that the BDI counts among its members. Although it claims to be the general voice of German industry, the BDI is in practice dominated by large corporations (Lang & Schneider, Citation2007: 231–232). By contrast, its regional composition puts the DIHK closer to the interests of the small, medium-sized, and family-owned enterprises (SMEs) that make up Germany’s Mittelstand (Heine & Sablowski, Citation2013: 9; Krickhahn, Citation2017: 124), which are also organized through several independent, if politically less effective, industry lobbies such as the Mittelstandsverbund ZGV and, most vocally, the Die Familienunternehmer. Some smaller sectoral associations also made occasional and focused interventions and are introduced when specific policies of the NIS 2030 are discussed.

In a second step, a close textual analysis is conducted to identify the main points of contention between government and industry, as well as potentially conflicting interests among industry lobbies and the segments and sectors they represent. Where differences in opinion among industry associations are observed, we turn to the critical scholarship on capital fractions for additional insights. Most important here are ‘the division into big and medium capital’ theorized by pioneering scholars (Poulantzas, Citation1973: 43; Aglietta, Citation1979: 299–306), and the sectoral differentiation of internationally operating German capital more recently hypothesized, if not yet empirically examined, by Heine and Sablowski (Citation2013: 7).

Finally, the article uses quantitative data on the trade and investment patterns and global export and profit shares of Germany’s key export sectors—chemical, electrical, machinery, and automotive. Drawing on the United Nations Comtrade Database, publications of the German Bundesbank, annual reports of sectoral business associations, and the Forbes Global 2000 database, it devises a set of four indicators that measure the sectoral importance of China as (1) an export market, (2) FDI destination, (3) a ‘high-tech’ competitor in global markets, and (4) competing for global profits of the world’s leading corporations. The aim is to assess whether there are differences in the structural positions of these sectors vis-à-vis a rising China. I propose that such differences could translate into sector-specific support for the NIS 2030 going forward, and I present these divergent sectoral orientations as an avenue for further research and refinement.

Wrestling with unevenness

The NIS 2030 conjures up a world undergoing a new industrial revolution that puts Germany in ‘an international race… to gain the lead on game-changing technologies’ (BMWi, Citation2019b: 8). Its principal competitors are US firms leading in the digital economy, and Chinese firms breaking into core sectors of high-tech manufacturing. Taken together, the challenge is formidable. Using the example of the self-driving electric car, the NIS 2030 warns that ‘if the digital platform were to come from the USA and the battery from Asia…, Germany and Europe would lose 50 per cent of value added in this area’ (BMWi, Citation2019a: 9). Worse still, Sino-American rivalries threaten the integrated world market on which Germany’s export model relies. Trump’s America First doctrine, largely continued under Biden, epitomises broader ‘trends toward sealing-off and protectionism’ (BMWi, Citation2019a: 8). And China’s Belt and Road and Made in China 2025 initiatives are considered ‘strategies of expansion… with the clear objective of conquering new markets… and monopolising such wherever possible’ (BMWi, Citation2019a: 8).

The central question for German state officials is how to meet competition from China and the US without emulating their (damaging) approaches, and without access to the institutional capacities either of the Chinese Communist Party apparatus or the US military-industrial complex (Starrs & Germann, Citation2021; Block, Citation2008). The NIS 2030 is best understood as an emergent, ‘defensive-mercantilist’ response to this dilemma (). It clearly differs from the ‘offensive mercantilism’ pursued by the Trump and now Biden administration, which deploys its security apparatus to pursue a coercive de-coupling from China (Johnson & Gramer, Citation2020). At the same time, it also diverges in important respects from the ‘defensive’ and ‘offensive’ liberalism characteristic of Germany’s postwar (foreign) economic policy: it neither simply upholds its own commitment to global free trade and multilateralism, nor does it seek to propel others in this direction (Germann, Citation2021). Rather, state power is used to create a protective and supportive environment for the German economy. For German business to achieve ‘a requisite critical mass to realise significant projects’, ‘assert itself in international competition’ and avoid ‘being shut out of an important and growing part of the global market’ (BMWi, Citation2019a: 11), the NIS 2030 aims to encourage the concentration and centralisation of capital through mergers and joint ventures. To match the vastly greater sums that the Chinese state and US venture capital pour into key technological innovations, the state is tasked to sponsor public-private partnerships and enlist institutional investors (BMWi, Citation2019a: 13; BMWi, Citation2019b: 20, 21, 23). And ‘to retain self-determination in key fields of technology’ and preserve ‘the relevant industrial substance’ in Germany and Europe, the state is to tightly screen foreign acquisitions, encourage corporate ‘white knights’ to step in in critical cases, or—failing that—act as investor of last resort (BMWi, Citation2019b: 27–28). This vision of economic sovereignty, lastly, also involves state-subsidised projects such as ‘an autonomous and trusted data infrastructure’ and ‘a new European industrial network of battery cell manufacturing’ (BMWi, Citation2019b: 22, 23).

Table 1. Strategic options of Germany’s foreign economic policy towards China.

Germany’s export bloc has opposed these plans so far because it has benefitted from the commercial opportunities that Chinese late development offered over the past two decades (e.g. Boyer, Citation2015). It fears that a turn to defensive mercantilism could infringe on the sanctity of private property and curtail access to the Chinese market if China were to retaliate (Wirtschaftswoche, Citation2020; Sorge, Citation2021). This has created a situation in which business—in the words of the economics minister—has ‘its sights set on its own advancement and not that of the entire country’ (BMWi, Citation2019a: 2). And it poses the puzzle of how and why the German state could have advanced key elements of the NIS 2030 without this critical constituency. To address it, the remainder of this article uses the lens of U&CD to investigate the structural and sectoral divisions within Germany’s export industry that I argue increase the relational autonomy of the German state.

Managing ‘bigness’

In light of a rapidly industrializing China, the problem of ‘bigness’ that Alexander Gerschenkron (Citation1962) famously posed as the critical precondition for capitalist late development has re-emerged as a key concern that German industry shares with the economics ministry. But while China is more often invoked, the immediate threat comes from US capital. Even before the pandemic depressed stock markets and raised fears of a corporate sell-off, the Financial Times reported that ‘[s]ome leading German executives also worry that Silicon Valley tech companies could swallow up significant parts of German industry because of their immense scale’ (McGee & Chazan, Citation2020). Measured in terms of market capitalization, Apple alone is larger than the DAX 30 companies combined (McGee & Chazan, Citation2020), and Tesla far outweighs the major German automakers taken together (Richter, Citation2020). Data from the Forbes Global 2000, used to calculate global profit shares of the world’s largest companies, shows that German corporations, with the exception of the automotive industry, are dwarfed by their US counterparts ().Footnote3

Table 2. Forbes Global 2000 National Profit Shares in Key Sectors, 2019.

While the challenge is recognized, the question of how to respond has divided German industry. Big business seeks to grow larger faster and aims to revise EU regulations on cross-border mergers and acquisitions (M&As). Invoking the China threat, the BDI—which is dominated by large corporations (Lang & Schneider, Citation2007: 231–232)—asks that ‘the market-driven formation of European champions should be permitted’ (BDI, Citation2019b: 9). Its counter-draft to the NIS 2030 holds that it is problematic for the European Commission to be both investigator and decider of M&A deals and asks for ‘checks and balances’ to be strengthened (BDI, Citation2019c: 10). And in a position paper on European policy, the BDI suggests that the Commission take global markets into account. In the age of Industry 4.0, the paper argues, cartel laws ought to be simplified and relaxed in order to encourage European competitors ‘to form a countervailing power to the big extra-European digital companies’ (BDI, Citation2019c: 9).

At the same time, this solution threatens smaller and family-owned enterprises that fear they will lose out or become the target of such a concentration drive (Heine & Sablowski, Citation2013: 10). In fact, much of the ire directed at the economics ministry and its ‘size matters’ outlook in the NIS 2030 reflects disagreements within industry (Schneider, Citation2020: 33). The Mittelstand lobby Die Familienunternehmer worries that ‘[t]his strategy is a frontal attack… If [economics minister] Altmaier wants to support large corporations and mergers, it’s to the detriment of everyone else’ (Bauchmüller, Citation2019; Die Familienunternehmer, Citation2020: 5). Similarly, the mechanical engineering industry association VDMA, which represents predominately smaller and medium-sized corporations in mechanical engineering (Kohler-Koch, Citation2016: 67), has defended the Commission’s independence against the more ambitious regulatory overhaul favored by the BDI (VDMA, Citation2020a: 2; VDMA, Citation2020b).

These conflicting interests call into question a distinctive feature of German capitalism: the surprisingly prominent role of manufacturing SMEs, as intermediate suppliers and directly as ‘hidden champions’, within Germany’s export-led bloc. Despite a rapid concentration drive following the Second World War (Leaman, Citation1988: 64–67), the regional support provided by a federalised state, the representational work of the BDI, and cross-shareholding banks ensured that a rough symmetry between Mittelstand and large-scale industry (Großindustrie) was maintained (Herrigel, Citation1996; Leaman, Citation1988: 116; Pistor, Citation2002: 117; Simonis, Citation1998: 260). Indeed, over the last forty years, the 50 largest industrial companies have accounted for a relatively stable share of about 32% of total industry sales (Monopolkommisison, Citation2020: 112). Sceptics have long suspected that structural imbalances might build up over time (Deubner et al., Citation1992: 161), and important political frictions appeared during the Eurozone crisis (Heine & Sablowski, Citation2013: 31). The lens of U&CD suggests that it is under the competitive pressures of a trailblazing US and a leapfrogging China that this compromise has unraveled further. This then offers the first piece of the puzzle as to how a contested initiative like the NIS 2030 could nevertheless translate into policies. This uneven development, and the renewed importance it places on the size, scope and scale of capitalist enterprise, has reactivated the latent structural conflict between big and medium capital. In this context, the state appears to reprise, and rethink, the traditional balancing role it played between Großindustrie and Mittelstand. It takes up, and aims to reconcile, their competing interests and—as we will see below—has been able to exact concessions from both sides.

On the one hand, the German government has consistently thrown its weight behind the plans of big business (BMWi, Citation2019b: 10; Schneider, Citation2020: 30). Ever since the Commission nixed a deal between Siemens and Alstom in 2018–2019, it has warned that EU competition policy ought not to so rigid as to ‘threaten the free development of industry’ (Doll, Citation2019). Together with France, Italy, and Poland, the economics ministry has pushed the Commissioner for Competition to overhaul the guidelines ‘on the assessment of horizontal mergers and the definition of the relevant market’ (Altmaier et al., Citation2020: 1; Chee, Citation2020). The catalogue of measures they propose is for the Commission to make the world market the relevant reference point in its investigations, to consider the state aid and domestic protection which foreign competitors receive, and to exempt joint ventures in foreign markets from stringent regulations (Altmaier et al., Citation2020: 2).

On the other hand, the German state has also addressed the concerns of many SMEs, who fall under national rather than EU regulation because of the size and source of their revenue. To demonstrate that they too can benefit from a new emphasis on corporate champions, the economics ministry in 2019 allowed the joint venture of two Mittelstand producers of industrial bearings, the German Zollern Group and Austrian Miba, to go ahead—overturning a ruling by the Federal Cartel Office and going against the advice of the German Monopoly Commission. Similarly, the 2021 update of the Competition Act (Gesetz gegen Wettbewerbsbeschränkungen, Act against Restraints of Competition) also promises to cut red tape by raising the domestic turnover threshold at which the Federal Cartel Office needs to be notified.

Most importantly, the core of what is also titled the ‘Digital’ Competition Act aims to increase the level of protection afforded to SMEs against large companies in the digital economy including e-commerce, online advertising, media streaming, computer software, cloud computing, social networking and artificial intelligence. The Act creates a legal basis for the German cartel office to launch pre-emptive antitrust probes into digital companies deemed to have ‘paramount cross-market importance for competition’ and impose harsh sanctions against the abuse of market power (Riecke, Citation2021). These new regulatory powers are unprecedented globally (Neuerer, Citation2020), and have been accompanied by a German bid—together with France and the Netherlands—to toughen up the EU’s Digital Markets and Digital Services Act (Espinoza, Citation2021). The explicit target is a handful of Silicon Valley digital giants—Alphabet (Google), Amazon, Apple, Meta (Facebook), and Microsoft—rather than European, let alone German, corporations. Soon after being passed into law, the German cartel office used its new toolbox to investigate Facebook and Amazon (Kipp, Citation2021; Jahberg, Citation2021).

In short, while the German state is removing obstacles to the greater concentration of German capital, it is checking market power in an area that affects a range of SMEs but where large German firms are unlikely to run afoul of stricter rules. A review of position papers indicates that this strategy has been successful.Footnote4 The associations of the Mittelstand, from the digital economy and other sectors, embrace the Act (Bundesverband Digitale Wirtschaft, Citation2020; Die Familienunternehmer, Citation2020; Der Mittelstandsverbund ZGV, Citation2020), while associations that count digital tech firms among their members are either skeptical or divided (ECO, Citation2020; Bitkom, Citation2020). The BDI cautions that these regulations could prevent the future rise of German and European tech giants (BDI, Citation2020: 2–3). And yet the German Telekom, the most likely contender for such a position, endorses the revised Act (Deutsche Telekom, Citation2020: 1). Overall, the US digital giants, who submitted individual position papers, are alone in their fierce criticism of the legislation.

In effect, then, the German government seeks to relax antitrust rules for German (and European) firms while tightening them for US (and Chinese) competitors in the digital economy.Footnote5 This selective intervention caters to both big business and the Mittelstand, and has allowed the German state to advance another highly controversial element of the NIS 2030: to expand its scope to screen and pre-empt unwanted FDI through a major revision of its Foreign Trade and Payments Act (Außenwirtschaftsgesetz) and Foreign Trade and Payments Ordinance (Außenwirtschaftsverordnung), passed in 2020 and 2021, respectively. The new Act allows the economics ministry to launch an investigation when a corporate deal is deemed ‘likely to affect’ public order or security, or ‘projects and programmes of EU interest’. Previously, this was limited to ‘factual threats’. The new Ordinance sets out a wide range of high-tech sectors where foreign (non-EU) acquisitions of more than 20% of voting interest in a company need to be reported and are automatically frozen until a decision is reached.Footnote6 For investments in critical infrastructures, the threshold is set at 10%. And lastly, the new Ordinance also expands the list of defense technology items where acquisitions above 10% undergo a ‘sector-specific’ review.

The principal target, ever since the 2016 Kuka takeover, are Chinese investors, who are feared to buy up strategic assets, transfer technology, and relocate production. Independent of size and sector, German industry opposes this tightening: it infringes on private property and contractual freedoms, starves the German economy of much-needed investment, and threatens access to the Chinese market (BDI, Citation2020; VDMA, Citation2020a; Die Familienunternehmer, Citation2021).Footnote7 And yet this opposition is weakened by contradictions. Big business relies on the German state to clear a path for its continued expansion across Europe, which it justifies by invoking unfair Chinese competition even as it worries more about Corporate America. Consequently, it is compelled to accept that similar reasons are cited by German regulators seeking to monitor Chinese investment more closely. The Mittelstand, meanwhile, has approved giving national authorities far-reaching regulatory powers to tackle the predominance of US digital giants. Given the new interventions in property rights and corporate conduct this opens the door to, it is difficult to challenge similar infringements in an area that has been elevated to a key national concern in word and law. As the employer-led German Economic Institute concluded its appraisal on investment screening, ‘[a]las, we have got to bite this bullet’ (Bardt & Matthes, Citation2019).

While vastly expanding its powers to protect German strategic assets with explicit reference to growing ‘global geo-economic competition’ (BMWi, Citation2021: 1), the German government also made some concessions to industry (BMWi, Citation2020b). For instance, the categories of target companies are more tightly defined than the summary term ‘critical technologies’, and the threshold for high-tech acquisitions, initially set at 10%, was raised to 20% to address the concerns of start-ups and financial investors (Hoppe, Citation2021). As a result, opposition to the final draft bill was more muted. Most notably, the DIHK (Citation2021: 2) reported with unease that, while most of its members reject the growing restrictions of entrepreneurial decisions, others now support the legislation as ‘the call for a strong state with a corresponding protectionism is becoming louder in some quarters of business’.

This observation raises the question, addressed below, of which elements of the export bloc could be won over to the NIS 2030. As with the divisions between capitals of different sizes discussed above, I postulate that the dynamics of uneven development may also have affected key sectors differently, and that this may be reflected in how their respective lobbies position themselves vis-à-vis the NIS 2030. This then delivers the second piece of the puzzle: in so far as the state can tailor elements of the NIS 2030 to specific sectors, it may get them to endorse the ‘defensive-mercantilist’ perspective embodied therein.

Seizing on sectoral divisions?

Over the last two decades, Chinese late industrialization has offered a vast market for German export manufacturers. Only in 2019 did the BDI (Citation2019a: 7) voice concerns that ‘[t]he primarily complementary nature of German-Chinese trade… is increasingly interspersed with fields in which German and Chinese manufacturers are in direct competition’ (BDI, Citation2019a: 7). This section uses trade and investment data to examine whether China’s entry into high-tech value chains has had a differential impact on ‘the key industries of Modell Deutschland’ (Heine & Sablowski, Citation2013: 9)—the chemical and automotive industry, and electrical and mechanical engineering. The central hypothesis—visualized in —is that the sectors least involved with China and most exposed to Chinese competition may be the most likely to support the defensive-mercantilist orientation embodied by the NIS 2030: they have the most to gain from industrial policies that protect and promote them, and they have the least to lose from Chinese retaliation compared to sectors that are heavily invested in and dependent on the Chinese market.

Table 3. Expected sectoral support for NIS 2030, ranked highest to lowest.

The section examines sectors according to four indicators: (1) the relative importance of the Chinese market for German exporters compared to their principal post-war trading partners, the US and France; (2) the relative concentration of FDI in China compared to the US; (3) their share in global exports of ‘high-tech’ products; and (4) their shares in the profits of the world’s top 2,000 corporations, as reported by Forbes Global 2000.

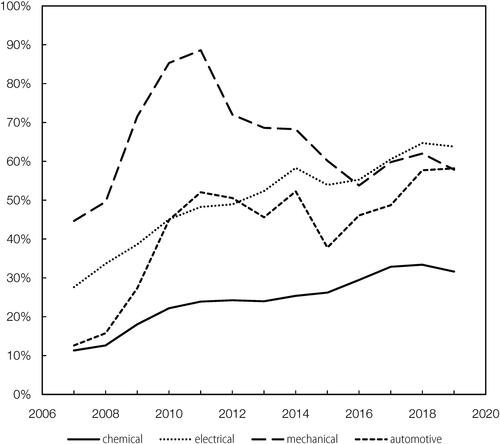

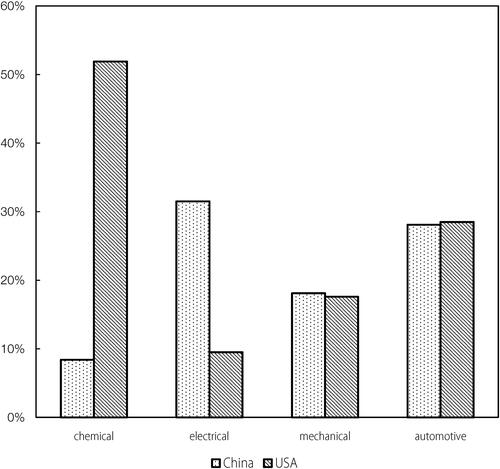

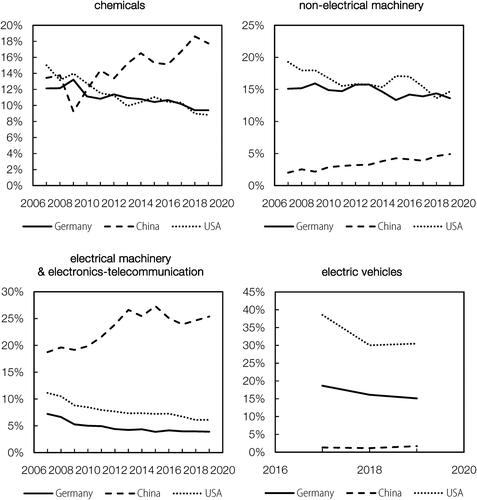

Our first question is which major markets the four sectors trade with and invest in most. On both counts, the chemical industry is by far the least involved with China. Chinese exports make up less than a third of its exports to the US and France (see ). A look at German FDI confirms this impression. In 2019, a whopping 52% of FDI by the chemical industry was located in the US, compared to only 8% in China (see ). The low level of FDI in China gives another important clue. It suggests that the German chemical industry is less likely to own Chinese firms and benefit from their economic success, and more likely, at least in principle, to confront them as competitors in third markets. To determine whether this is the case, the second step compares countries’ shares in global exports of ‘high-tech’ manufactures (). And indeed, for ‘high-tech’ chemical exports, the Chinese share rose from 13 to 18% between 2007 and 2019, and is now twice as large as Germany’s. It is only at the very top, and in terms of national profit shares, that German chemical companies retain a comfortable lead—double that of their Chinese competitors ().

Figure 1. German exports to China, percentage of combined exports to France and US, by sector.

Source: UN Comtrade; VDMA (various annual issues) Maschinenbau in Zahl und Bild

Figure 2. Host country share of German FDI by investing sector, 2019.

Source: Deutsche Bundesbank (2022) Direktinvestitionsstatistiken: Statistische Fachreihe.

Figure 3. Country share in global ‘high-tech’ exports, by product.

Note: Calculations based on the classification and aggregation of ‘high-technology’ product groups used by Eurostat (dividing research and development expenditure by total sales) in its indicators on high-tech industry and knowledge-intensive services (https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Archive:High-tech_statistics_-_economic_data#Trade_in_high-tech_products). For the automotive industry, the new product class (available since 2017) ‘motor vehicles powered by electric motors only’ (HS 870380) is used, as first calculated by Daniel Workman: http://www.worldstopexports.com/electric-cars-exports-by-country/

Source: UN Comtrade (SITC Rev. 4 & HS 2017)

In terms of trade and investment, the German automotive industry is far more dependent on the Chinese market. Its exports have nearly quintupled since 2007. In 2019, they made up 58% of its exports to France and the United States put together, compared to just 13% in 2007 (). Note also that a focus on exports underestimates the depth of integration, as most vehicles sold by German manufacturers in China are produced there (VDA, Citation2020: 33). A look at the stock of FDI in China, as a percentage of total German FDI, sets the automotive industry apart from the chemical sector. In 2019, it stood at 28%, about equal to its US investment (29%) (). Judged by its global export shares in ‘motor vehicles powered by electric motors only’—available from 2017—the German auto industry does not yet appear to be threatened by Chinese companies in international markets, though significantly outsized by US carmakers. This picture is rounded off by the massive lead German automotive companies enjoy over their Chinese rivals in global profit shares—29% compared to 9% ().

The electrical and mechanical engineering industry are difficult to isolate analytically. But if we follow the Harmonized System classifications used by the electrical industry association ZVEI to compile its reports, we find that for the electrical industry, the size of the Chinese export market was 64% of that of France and the US, up from 28% in 2007 (). The FDI stock of the electrical industry in China is triple the figure for the United States, 32% compared to 10% (). China’s global dominance in this sector, meanwhile, is unmistakable. In 2019 China accounted for a quarter of all global exports of electrical machinery and telecommunications equipment classifiable as ‘high-tech’, while Germany’s share declined from 7 to 4% between 2007 and 2019 (). The top Chinese firms also account for twice as large a share of profits in this sector (). Together, these two indicators suggest that Chinese competition is pronounced.

The picture for the mechanical engineering sector is more mixed. It does not stand out either in terms of exports to or investment in China. To be sure, its share in the profits of the Forbes Global 2000 firms in this sector is lower than that of their Chinese rivals—6% compared to 10%—which suggest that the largest firms do face Chinese competition. But what sharply distinguishes it from the electrical industry is that it still has a large lead over China in ‘high-tech’ ‘non-electrical machinery’ exports. In 2019, it accounted for 14% of global exports, compared to 5% for China (and roughly on par with the US at 15%).

What does this data tell us? At a minimum, it shows that the commercial opportunities and pressures of a late industrializing China have been unequally divided between Germany’s main export sectors. An important finding in its own right, this adds nuance to the debate over how important China is to the German economy, and how big of a challenge it poses. Moreover, as summarized in , these sectoral differences might also translate into different degrees of support for the NIS 2030 within the ranks of the German export bloc. On the basis of the four indicators presented here, we would expect the chemical industry, followed by the electrical industry, to be most amenable to the defensive-mercantilist outlook outlined in the NIS 2030: the former is the least reliant on China as a sales market and would suffer least if China was to restrict access to its market; and alongside the latter, it faces China as a serious global competitor, and may therefore be more likely to seek the protection and support promised by the NIS 2030.

There is some qualitative evidence that aligns with these sectoral divisions. On the controversial issue of stricter FDI screening, for instance, it is striking that the VCI (Citation2021a: 2) floated a compromise that would have exempted close security allies—like the US but clearly unlike China. This position stands in contrast to the VDMA, which worries that stricter FDI rules will undermine efforts to broaden access to Chinese markets (Dierig, Citation2021). It most likely reflects the outsized importance of the US relative to the Chinese market for the chemical sector. Similarly, whereas the VDMA, and industry more broadly, firmly rejects the preferential treatment of certain industries and selective state intervention (Sorge, Citation2021), the VCI most vocally calls for a ‘sectoral approach’ of targeted state subsidies exempted from normal EU state aid rules (VCI & France Chimie, Citation2021: 1; VCI, Citation2021b: 2, 18)—a reflection, presumably, of the massive share in global ‘high-tech’ exports of Chinese firms in this sector.

And lastly, while the ZVEI rejects reshoring or decoupling as ‘political strategies’, it adds that these can ‘in individual cases be business decisions by industrial players themselves’ and urges regulators to incentivize ‘companies to build up capacities in Europe’ (ZVEI, Citation2020a: 11; 2020b; 2020c). Of the four major sectors, the electrical industry lobby goes furthest here in signaling conditional support for re-building strategic value chains in Germany and Europe (ZVEI, Citation2020b; Citation2020c)—plans that a former German official and critic of the NIS 2030 called its ‘most Trumpian feature’ (Zettelmeyer, Citation2019: 7), and that the German export bloc as a whole rejects. It stands to reason that Chinese competition, in terms of both global export and profit shares, is an important driver here.

In sum, this analysis suggests that if the German state seizes on these splits and courts the chemical and electrical industry with the promise of state aid—currently pursued, under so-called ‘Important Projects of Common European Interests’ (IPCEIs), in the areas of semiconductors, cloud computing, pharmaceuticals, batteries, and hydrogen fuels (EC, Citation2021: 14)—it may be able to enlist them in its plans to secure its ‘industrial and technological sovereignty’ (BMWi, Citation2019a: 10; BMWi, Citation2019b: 31).

Conclusion

The NIS 2030 marks the first time in decades that German officials openly contemplated a significantly augmented role for the state in promoting and protecting its industrial base, technological lead, and economic independence—much to the chagrin of German export industry, which rejected this new interventionism as outdated and misguided. To understand how the German state could nevertheless proceed with these plans, this article has mobilized critical state theory and the frame of U&CD to contextualize the NIS 2030 and investigate the underlying state-capital dynamics. The main argument is that the unevenness of capitalist globalization—with the US at the forefront and China at the rear—has introduced tensions into Germany’s export bloc along two lines that increase the state’s scope for initiative. The digital lead and economic scope and scale of US corporations have deepened the structural conflict between large corporations seeking to keep up with their American competitors and smaller and family-owned enterprises that fear they will be left behind. A late-developing China making inroads into high-tech manufacturing, meanwhile, is experienced differently by Germany’s major export sectors.

The article has argued that the German state has navigated divisions between big business and the Mittelstand—offering laxer cartel rules to the former and protection from digital oligopolies to the latter, in exchange for tighter FDI controls. And it has suggested that the chemical and electrical industry, the former least reliant on China and the latter most exposed to Chinese competition, could be won over to its plans to re-shore global value chains. Overall, the article concludes that if the German state can cater to these two sectors while continuing to mediate between capital of different sizes, it may be able to construct a broader coalition in support of its defensive-mercantilist approach.

Further research is needed to extend this investigation. First, while German policy and corporate elites reject the offensive-mercantilist approach the US has taken against China (and now Russia), the defensive-liberal and offensive-liberal orientations are still in play. They should be examined as parallel tracks in the wider reconfiguration of German (foreign) economic strategy, inaugurated by the NIS 2030 and driven—I have argued—by tectonic shifts in global capitalism. Second, the investigation should extend to social forces and corporate interests outside the German export bloc (Schneider, Citation2020: 32–34). In this regard, an analysis of specific production networks that bring together large and small firms from different sectors and from across Europe would be a welcome addition.

Lastly, the analysis presented here needs to be extended beyond the cesurae represented by the pandemic and the Ukraine war. The virus demonstrated just how fragile the current form of globalization is, and Russia’s invasion has made a geopolitical case for why Germany ought to reassess its relationship with and dependence on China. Together, these two shock events have greatly accelerated the momentum towards new types of state intervention beyond the classical field of industrial policy—from reliable and renewable energy sources to access to critical raw materials and industrial inputs, control over advanced technologies, and diversified export markets. In view of the added urgency to reduce economic vulnerabilities and secure political autonomy, even fierce critics of the NIS 2030 now acknowledge that its authors ‘recognised a dangerous tendency better than many others’ (Felbermayr, Citation2022: 103). As the ground-breaking step in this wider strategic rethink, the NIS 2030 thus remains instructive; and Germany, as the centre of a regional hub-and-spoke manufacturing system with deep ties to China, Russia, and the US, will be the critical case to watch for IPE scholars interested in the ‘return of the state’ across the global political economy, and in the EU in particular.

The key to understanding this global movement, this article has proposed, is a frame that holds in view both the social forces vying over new forms of state, and a globalizing capitalism that intervenes in and rearranges this terrain of struggle. A purely domestic analysis, not least when it relies on institutional models, falls short whenever these wider dynamics spill onto the national scene; and many international analyses, beholden to a realist worldview, reduce them to an invariant logic of inter-state competition. The lens of U&CD offers a better vista of these systemic forces. It approaches global capitalist development as a staggered process spaced out over the past century and reshaped by the particularities that each newcomer adds to the whole. Uneven in timing, pace, and composition, capitalist globalization creates new risks and opportunities that can shift the social balance of interest and strategic calculus of policy elites of a given country in novel directions, including in the current debate over the purview of state power.

Acknowledgement

This article benefitted enormously from the feedback of three anonymous reviewers and the editors. I would also like to thank Milan Babić, Mareike Beck, Alan Cafruny, Mark Schwartz and Sean Starrs for their comments on earlier drafts. And lastly, I am particularly grateful for a productive exchange with Etienne Schneider, whose 2020 article on the topic offered theoretical and empirical insights that the present article takes up and aims to add to.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Data availability statement

The primary data that support the findings of this study are derived from resources available in the public domain. URLs to the original source are provided.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Julian Germann

Julian Germann is Senior Lecturer in International Relations at the University of Sussex (Department of International Relations, School of Global Studies, Brighton, United Kingdom) and author of Unwitting Architect: German Primacy and the Origins of Neoliberalism (Stanford University Press, 2021).

Notes

1 The final version published in December 2019 dropped “national” from its title, but for ease of reading the article uses the abbreviation “NIS 2030”.

2 I would like to thank an anonymous reviewer for inviting me to contemplate this proposition.

3 For a longer time series, see Starrs and Germann (Citation2021). For the original approach to this dataset, see Starrs (Citation2013).

4 The stakeholder responses to the draft Competition Act can be found here: https://www.bmwi.de/SiteGlobals/BMWI/Forms/Listen/Stellungnahmen-GWB-Digitalisierungsgesetz/Stellungnahmen-GWB-Digitalisierungsgesetz_Formular.html?resourceId=1673768&input_=1709136&pageLocale=de&templateQueryStringListen=&titlePrefix=Alle&addSearchPathId=1673902&addSearchPathId.GROUP=1&selectSort=&selectSort.GROUP=1#form-1673768.

5 For a long-term comparison of the trajectories and complexities of German and US competition policy, see Ergen and Kohl (Citation2019).

6 The pandemic prompted the cabinet to pass an advance version of the Ordinance in May 2020 that set the reporting threshold for health, state communications infrastructure, and raw materials at 10% (BMWi, Citation2020a).

7 The stakeholder responses to the recent updates of the Foreign Trade and Payments Ordinance and Act can be found here: https://www.bmwi.de/Redaktion/DE/Artikel/Service/Gesetzesvorhaben/aenderungen-im-investitionspruefungsrecht.html; https://www.bmwi.de/Navigation/DE/Service/Stellungnahmen/15-VO-AWV/15-vo-awv.html.

References

- Abelshauser, W. (2016). Einleitung: Der deutsche Weg der Wirtschaftspolitik [Introduction: The German path of economic policy]. In W. Abelshauser (Ed.), Das Bundeswirtschaftsministerium in der Ära der Sozialen Marktwirtschaft: Der deutsche Weg der Wirtschaftspolitik [The Federal Economics Ministry in the era of the social market economy: The German path of economy policy] (pp. 1–21). De Gruyter.

- Aglietta, M. (1979). A theory of capitalist regulation. Verso.

- Alami, I., & Dixon, A. (2020). State capitalism(s) redux? Theories, tensions, controversies. Competition & Change, 24(1), 1–11094. https://doi.org/10.1177/1024529419881949

- Alami, I., & Dixon, A. (2021). Uneven and combined state capitalism. Economy and Space, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X211037688

- Altmaier, P., Patuanelli, S., Le Maire, B., & Jadwiga, E. (2020, February 4). Letter to Mrs Margrethe Vestager, Executive Vice-President and Commissioner for Competition. https://www.politico.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Letter-to-Vestager.pdf

- Andreoni, A., & Chang, H. (2019). The political economy of industrial policy: Structural interdependencies, policy alignment and conflict management. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 48, 136–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.strueco.2018.10.007

- Antunes de Oliveira, F. (2021). Of economic whips and political necessities: A contribution to the international political economy of uneven and combined development. Cambridge Review of International Affairs, 34(2), 267–295. https://doi.org/10.1080/09557571.2020.1818690

- Baccaro, L., & Pontusson, J. (2016). Rethinking comparative political economy: The growth model perspective. Politics & Society, 44(2), 175–207. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329216638053

- Baccaro, L., & Pontusson, J. (2018). Comparative political economy and varieties of macroeconomics. MPflG Discussion Paper 18/10.

- Baccaro, L., & Pontusson, J. (2019). Social blocs and growth models: An analytical framework with Germany and Sweden as illustrative cases. UNIGE Working Paper.

- Bardt, H., & Matthes, J. (2019, November 29). Industriestrategie: Ein schmaler Grat [Industrial strategy: A fine line]. Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft. https://www.iwkoeln.de/presse/iw-nachrichten/beitrag/hubertus-bardt-juergen-matthes-ein-schmaler-grat.html

- Bauchmüller, M. (2019, April 8). Wirtschaft empört sich offen über Altmaier [Business up in arms against Altmaier]. Süddeutsche Zeitung. https://www.sueddeutsche.de/wirtschaft/altmaier-kritik-industriestrategie-1.4400963

- BDI. (2019a, May 6). Deutsche Industriepolitik: Zum Entwurf der Nationalen Industriestrategie 2030 [German industrial policy: On the draft national industrial strategy]. https://issuu.com/bdi-berlin/docs/20190506_position_bdi_industriepoli

- BDI. (2019b, January). Partner and systemic competitor: How do we deal with China’s state-controlled economy? https://english.bdi.eu/publication/news/china-partner-and-systemic-competitor/

- BDI. (2019c, June 20). Eine Zukunftsagenda für Europa: Sieben industriepolitische Prioritäten [An agenda for the future of Europe: Seven industrial policy priorities]. https://bdi.eu/publikation/news/eine-zukunftsagenda-fuer-europa/

- BDI. (2020, March 10). Zum Referentenentwurf des BMWi zum Zehnten Gesetz zur Änderung des Gesetzes gegen Wettbewerbsbeschränkungen für ein fokussiertes, proaktives und digitales Wettbewerbsrecht 4.0 [On the BMWi’s first draft of the Tenth Revision of the Competition Act for a focused, proactive and digital Competition Law 4.0] https://www.bmwi.de/Redaktion/DE/Downloads/Stellungnahmen/Stellungnahmen-GWB-Digitalisierungsgesetz/Verbaende-und-Unternehmen/bdi.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=6

- Behrens, M. (2018). Structure and competing logics: The art of shaping interests within German employers’ associations. Socio-Economic Review, 16(4), 769–789.

- Belfrage, C., & Hauf, F. (2017). The gentle art of retroduction: Critical realism, cultural political economy and critical grounded theory. Organization Studies, 38(2), 251–271. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840616663239

- Bitkom (2020, March 23). Stellungnahme zur 10. GWB-Novelle [Statement on the 10th revision of the Competition Act]. https://www.bitkom.org/sites/default/files/2020-03/20200323_bitkom-stellungnahme-zur-10.-gwb-novelle.pdf

- Block, F. (2008). Swimming against the current: The rise of a hidden developmental state in the United States. Politics & Society, 36(2), 169–206.

- BMWi. (2019a, February 5). National Industrial Strategy 2030: Strategic guidelines for a German and European industrial policy. https://www.bmwi.de/Redaktion/EN/Publikationen/Industry/national-industry-strategy-2030.html

- BMWi. (2019b, November 29). Industrial Strategy 2030: Guidelines for a German and European industrial policy. https://www.bmwi.de/Redaktion/EN/Publikationen/Industry/industrial-strategy-2030.html

- BMWi. (2020a, January 30). Stärkung des nationalen Investitionsprüfungsrechts: Kerninhalte des ersten Teils der Novelle des Außenwirtschaftsrechts [Strengthening investment control regulations: Key contents of the first part of the revised Foreign Trade and Payments Act] https://www.bmwi.de/Redaktion/DE/Downloads/J-L/kerninhalte-des-ersten-teils-der-novelle-des-aussenwirtschaftsrechts.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=4

- BMWi. (2020b, October 29). Änderungen im Investitionsprüfrecht [Changes in investment control law]. https://www.bmwi.de/Redaktion/DE/Artikel/Service/Gesetzesvorhaben/aenderungen-im-investitionspruefungsrecht.html

- BMWi. (2021, 27 April). Siebzehnte Verordnung zur Änderung der Außenwirtschaftsverordnung [Seventeenth Ordinance to revise the Foreign Trade and Payments Ordinance] (Bundesanzeiger AT 30.04.2021 V1). https://www.bundesanzeiger.de/pub/de/amtliche-veroeffentlichung?1

- Bofinger, P. (2019). Paradigmenwechsel in der deutschen Wirtschaftspolitik [Paradigm shift in German economic policy]. Wirtschaftsdienst: Zeitschrift für Wirtschaftspolitik, 99(2), 95–98.

- Bohle, D., & Regan, A. (2021). The comparative political economy of growth models: Explaining the continuity of FDI-led growth in Ireland and Hungary. Politics & Society, 49(1), 75–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329220985723

- Boyer, R. (2015). The success of Germany from a French perspective: What consequences for the future of the European Union? In B. Unger (Ed.), The German model: Seen by its neighbours (pp. 201–236). SE.

- Brand, U. (2013). State, context and correspondence. Contours of a historical-materialist policy analysis. Österreichische Zeitschrift für Politikwissenschaft, 42(4), 425–442. https://webapp.uibk.ac.at/ojs/index.php/OEZP/article/view/1478

- Brand, U., Krams, M., Lenikus, V., & Schneider, E. (2022). Contours of historical-materialist policy analysis. Critical Policy Studies, 16(3), 279–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/19460171.2021.1947864

- Bundesverband Digitale Wirtschaft. (2020, February 13). Stellungnahme des Bundesverbands Digitale Wirtschaft e.V. zum GWB-Digitalisierungsgesetz [Statement of the Bundesverband Digitale Wirtschaft e.V. on the Digital Competition Act]. https://www.bvdw.org/fileadmin/bvdw/upload/publikationen/digitalpolitik/BVDW.Stellungnahme.GWBDigitalisierungsgesetz.13022020.pdf

- Bührer, W. (2017). Geschichte und Funktion der deutschen Wirtschaftsverbände [History and function of Germany’s business associations]. In W. Schroeder & B. Weßels (Eds), Handbuch Arbeitgeber- und Wirtschaftsverbände in Deutschland [Handbook of employer and business associations in Germany] (pp. 53–84, 2nd ed.). Springer.

- Chang, H., & Andreoni, A. (2020). Industrial policy in the 21st century. Development and Change, 51(2), 324–351. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12570

- Chasoglou, I. (2019). Krisenpolitik und Kapitalfraktionen: Deutschland, Frankreich und die Unternehmerverbände in der Krise der EU [Crisis policy and capital fractions: Germany, France and the associations of business during the crisis of the EU] [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen.

- Chee, F. Y. (2020, February 6). EU antitrust regulators stresses fair rules as Germany, France call for overhaul. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/eu-antitrust-idINL8N2A66ZU

- Culpepper, P. (2015). Structural power and political science in the post-crisis era. Business and Politics, 17(3), 391–409. https://doi.org/10.1515/bap-2015-0031

- Deubner, C., Rehfeld, U., & Schlupp, F. (1992). Franco-German economic relations within the international division of labour: Interdependence, divergence or structural dominance? In W. Graf (ed.), The internationalization of the German political economy (pp. 140–186). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Deutsche Telekom. (2020). Stellungnahme zur Novellierung des GWB [Statement on the Revision of the Competition Act]. https://www.bmwi.de/Redaktion/DE/Downloads/Stellungnahmen/Stellungnahmen-GWB-Digitalisierungsgesetz/Verbaende-und-Unternehmen/deutsche-telekom.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=6

- Der Mittelstandsverbund ZGV [Zentralverband Gewerblicher Genossenschaften]. (2020, February 12). Stellungnahme zum Referentenentwurf eines Zehnten Gesetzes zur Änderung des Gesetzes gegen Wettbewerbsbeschränkungen für ein fokussiertes, proaktives und digitales Wettbewerbsrecht 4.0 [Statement on the ministerial draft of the Tenth Revision of the Competition Act for a focused, proactive and digital Competition Law 4.0]. https://www.mittelstandsverbund.de/media/b23664e2-3b4b-43b3-93c4-d09f648db780/DxjVnw/Download/Inhaltliche%20Papiere/2020-02-13-ZGV-Stellungnahme%2010.%20GWB%20Novelle.pdf

- Die Familienunternehmer. (2019, May) Nationales Fitness-Programm [National Fitness Programme]. https://publikationen.familienunternehmer.eu/fitness-programm/

- Die Familienunternehmer. (2020, 13 February). Zum Referentenentwurf eines Zehnten Gesetzes zur Änderung des Gesetzes gegen Wettbewerbsbeschränkungen für ein fokussiertes, proaktives und digitales Wettbewerbsrecht 4.0 [On the ministerial draft of the Tenth Revision of the Competition Act for a focused, proactive and digital Competition Law 4.0]. https://www.familienunternehmer.eu/fileadmin/familienunternehmer/publikationen/stellungnahmen/2020/familienunternehmer_stellungnahme_10_gwb_novelle.pdf

- Die Familienunternehmer. (2021). Referentenentwurf für die 17. Verordnung zur Änderung der Außenwirtschaftsverordnung [Ministerial draft for the Seventeenth Ordinance to revise the Foreign Trade and Payments Ordinance]. https://www.familienunternehmer.eu/fileadmin/familienunternehmer/publikationen/stellungnahmen/2021/Stellungnahme_DIE_FAMILIENUNTERNEHMER_17te_AWV.pdf

- DIHK. (2021, February 26). Stellungnahme: Referentenentwurf des Bundesministeriums für Wirtschaft und Energie vom 22.01.2021: Siebzehnte Verordnung zur Änderung der Außenwirtschaftsverordnung—Ausweitung der Investitionsprüfungen [Statement: ministerial draft of the Federal Ministry of Economics and Energy of 22 January 2021: Seventeenth Ordinance to revise the Foreign Trade and Payments Ordinance—Extending Investment Controls]. https://www.dihk.de/resource/blob/37558/ca987825c192c555d41d3ed99bf7e255/dihk-stellungnahme-aussenwirtschaftsverordnung-data.pdf

- Dierig, C. (2021, May 8). Wegen 2 von 40.000 Artikeln: Staat beschneidet Freiheit der Maschinenbauer [For 2 out of 40,000 articles: State curtails freedom of machine builders]. Die Welt. https://www.welt.de/wirtschaft/article230964625/Aussenwirtschaftsverordnung-Staat-beschneidet-Freiheit-deutscher-Maschinenbauer.html

- Doll, N. (2019, February 20). Berlin und Paris machen Industriepolitik [Berlin and Paris pursue industrial policy]. Die Welt. https://www.welt.de/print/welt_kompakt/print_wirtschaft/article189079091/Berlin-und-Paris-machen-Industriepolitik.html

- Dooley, N. (2019). The European periphery and the Eurozone crisis: Capitalist diversity and Europeanisation. Routledge.

- ECO. (2020, February 13). Stellungnahme zum Referentenentwurf eines Zehnten Gesetzes zur Änderung des Gesetzes gegen Wettbewerbsbeschränkungen für ein fokussiertes, proaktives und digitales Wettbewerbsrecht 4.0 [Statement on the ministerial draft of the Tenth Revision of the Competition Act for a focused, proactive and digital Competition Law 4.0]. https://www.eco.de/wp-content/uploads/dlm_uploads/2020/04/20200213_ecostn-zur-10.novelle-des-gesetzes-gegen-wettbewerbsbeschraenkungen-1.pdf

- Ergen, T., & Kohl, S. (2019). Varieties of economization in competition policy: Institutional change in German and American antitrust, 1960–2000. Review of International Political Economy, 26(2), 256–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2018.1563557

- Espinoza, J. (2021, May 27). EU is too soft on big tech, say France, Germany, and the Netherlands. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/e0248106-e6d5-4b2a-aaef-b52d464dcc03

- EC. (2021, May 5). Updating the 2020 New Industrial Strategy: Building a stronger Single Market for Europe’s recovery (Com(2021) 350 final). https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/communication-industrial-strategy-update-2020_en.pdf

- Felbermayr, G. (2022). Wandel durch Handel funktioniert durchaus [Change through trade does work]. Perspektiven der Wirtschaftspolitik, 23(2), 94–107. https://doi.org/10.1515/pwp-2022-0020

- Germann, J. (2021). Unwitting architect: German primacy and the origins of neoliberalism. Stanford University Press.

- Gerschenkron, A. (1962). Economic backwardness in historical perspective. Belknap.

- Gersemann, O. (2019, November 29). Industriestrategie 2030: Die vier weichgespülten Wunschträume des Peter Altmaier [Industrial Strategy 2030: The four watered-down dreams of Peter Altmaier]. Welt Online. https://www.welt.de/wirtschaft/article203918238/Industriestrategie-2030-Altmaier-nimmt-Abstand-von-Rettungsschirm-Idee.html

- Graw, A. (2019). May 9). Stimmt in unserem Land etwas nicht? Der Bundestag debattiert über die 'Wirtschaftsverfassung Deutschlands' [Is there something wrong in our country? The Bundestag debates 'Germany’s economic constitution']. Die Welt. https://www.welt.de/print/welt_kompakt/print_politik/article193198869/Stimmt-in-unserem-Land-etwas-nicht.html

- Green, S., & Paterson, W. E. (2005). Introduction: Semi-sovereignty challenged. In S. Green & W. E. Paterson (Eds.), Governance in contemporary Germany: The semi-sovereign state revisited (pp. 1–20). Cambridge University Press.

- Hawley, J. (1987). Dollars and borders: U.S. government attempts to restrict capital flows (1960–1980). M.E. Sharpe.