Abstract

This article critically discusses the scope for decolonizing economics teaching. It scrutinizes what it would entail in terms of theory, methods, and pedagogy, and its implications for scholars grappling with issues related to economics teaching. Based on a survey of 498 respondents, it explores how economists across different types of departments (economics/heterodox/non-economics), geographical locations, and identities assess challenges to economics teaching, how they understand the relevance of calls for decolonization, and how they believe economics teaching should be reformed. Based on the survey findings, the article concludes that the field’s emphasis on advancing economics as an objective social science free from political contestations, based on narrow theoretical and methodological frameworks and a privileging of technical training associated with a limited understanding of rigor, likely stands in the way of the decolonization of economics. Indeed, key concepts of the decolonization agenda—centering structural power relations, critically examining the vantage point from which theorization takes place and unpacking the politics of knowledge production—stand in sharp contrast to the current priorities of the economics field as well as key strands of IPE. Finally, the article charts out the challenges that decolonizing economics teaching entails and identifies potential for change.

Introduction

The calls to decolonize the social sciences have recently permeated, albeit marginally, the discipline of economics. These calls have especially gained momentum in the wake of the escalation of the Black Lives Matter movement in the US in 2020 that questioned the discipline’s limited capacity to address the structural underpinnings of racialized inequalities. This is relevant for all scholars, including scholars of International Political Economy (IPE), whose teaching involves an engagement with standard economic theories and approaches. What is more, there are strands of IPE that are also thoroughly Eurocentric, especially American IPE which is strongly influenced by methodological and theoretical developments in economics (Cohen, Citation2008). Nonetheless, there have been serious efforts to address the needs to decolonize IPE itself as well, including in this journal. However, thus far, those efforts have mostly come from the more culture-focused postcolonial traditions rather than the more materialist anti-imperialist, Marxist post-colonial, and decolonial traditions. The former interventions often tend to treat colonialism as a ‘blind spot’ (Best et al., Citation2021; Bhambra, Citation2021; LeBaron et al., Citation2021). This stands in contrast to a radical decolonization agenda, which, instead of seeing Eurocentric aspects of the social sciences as blind spots to be corrected within dominant paradigms, seeks to unpack how dominant approaches may preclude the study of systemic processes associated with decolonization, such as structural racism and imperialism. A radical decolonization agenda seeks to foreground the need for theoretical apparatuses whose frameworks might be more amenable to studying the systemic processes that both aid in subordinating societies that were formerly colonized and facilitate new forms of colonization (Alves et al., forthcoming). In doing so, a questioning of the very building blocks of economic theory becomes necessary. To carry out such a questioning, we find it fruitful to draw from anti-imperialist (Amin, 1988/2009), decolonial (Quijano, Citation2000), Marxist post-colonial (Sanyal, Citation2007), as well as feminist IPE scholarship (Hartsock, Citation2006). Economics’ strong influence on other disciplines also adds urgency to the task of unpacking biases in the field for a broader understanding of decolonization and Eurocentrism in the social sciences (Fine & Dimitris, Citation2009).

In the following section, we first introduce what we mean by Eurocentrism in the context of economics before laying out what decolonizing economics—and specifically decolonizing economics teaching—entails. Next, based on a survey of 498 economists conducted between January and March 2020 we assess the extent to which economists at the ‘top’ of the discipline are concerned with decolonizing economics teaching. The survey, drawing on established debates about economics teaching as well as insights from the decolonization agenda and decolonial pedagogy, seeks to understand what the respondents think about economics teaching, the ways in which economics teaching could be reformed, and what the constraints to such reform are. Analyzing ‘top’ universities is important since they play a central role in what gets accepted as legitimate knowledge. Further, we evaluate how different departments—including mainstream economics, heterodox/pluralist economics, and non-economics departments—approach the question of decolonizing teaching differently, before examining how approaches toward decolonization differ across geographies, universities, and identities. The results suggest that the field’s prevalent understanding of ‘rigor’ allows only for ‘weak objectivity’ (following Harding, Citation1992) without providing space for alternative ways to make sense of social phenomena, let alone for ways to grasp structural oppression and inequalities. This, in turn, acts as a constraint on the decolonization of economics teaching. In contrast, we argue that decolonization of economics teaching might be better achieved through an approach that introduces students to frameworks that are more amenable to capturing structural processes and allows for explicit theorization from a variety of vantage points, including from the perspective of marginalization. Such an approach, while providing a broader understanding of objectivity and rigor, may also pave the way for a more relevant and critical discipline fit for tackling the structural societal challenges we are facing.

The evolution of a colonial field and the challenges of decolonizing economics teaching

The Eurocentric bias in knowledge production has been critiqued by several traditions, including in decolonial, anti-imperialist and postcolonial scholarship. While most of these critiques have remained on the periphery of social science disciplines, as pointed out by Kayatekin (Citation2009, p. 1113), ‘economics proved to be the discipline most resistant to change’. In this section we first define what we mean by Eurocentrism and how it relates to a colonization of economics, before providing some illustrations of how the field itself can be understood as Eurocentric. We then move on to lay out what we mean by decolonizing economics and, relatedly, IPE, and how this pertains to teaching.

Eurocentrism and colonialism in economics

There are many entry-points from which to understand Eurocentrism in economics and IPE (Wallerstein, Citation1997). For example, postcolonial theorists such as Edward Said (Citation1978) view Eurocentrism as a set of attitudes that take the form of a particular discourse, but do not necessarily explore the ways in which they might produce specific regimes of accumulation, expropriation, and exploitation. Meanwhile, anti-imperialist Marxian strands and critical scholarship on post-colonial capitalism, following Samir Amin (1988/2009) and Kalyan Sanyal (Citation2007), do not see Eurocentrism as merely a particular understanding of the world, but instead view it either as a polarizing global project that reinforces imperialism and systemic inequalities and/or unpack how dominant understandings of capitalism fail to recognize post-colonial experiences of capitalist development. For the purpose of this article, and with a view of the economics field in particular, our understanding finds resonance with Amin’s materialist perspective and strands of literature on post-colonial capitalist development that focuses specifically on the ways Eurocentrism has shaped capitalism as well as economists’ view of it. In this context, Eurocentrism can be seen as an understanding of the world that centers the idea of endogenous capitalist development in Western Europe, which in turn is associated with the Enlightenment values of rationality and objectivity and views the rest of the world only in relation to it. All social processes that do not align with this capitalist imagination, including alternative views of and forms of identities, rationalities, and institutions, are then devalued as imperfections (Zein-Elabdin & Charusheela, Citation2004).

Following this, the reason Europe emerges as the ‘center’ lies in the emergence of capitalism as the hegemonic global order, with Europe coming to represent its essence (Lazarus, Citation2011). In such an understanding, capitalist development is presented as a rational and all-pervasive progression that is expected to unfold, often organically. throughout the world, with all economies transitioning along the lines of this Eurocentric capitalist imagination (Bhattacharya & Kesar, Citation2020; Rist, Citation1997; Sanyal, Citation2007). Absent from this understanding are the processes of colonialism, the slave trade, drain of wealth, racial violence, and other forms of structural subordination that underpinned the development of capitalism in Europe, while, simultaneously, restricting the possibility of such a realization universally (Blaut, Citation1993; Robinson, Citation1983). What is more, this idealized view sweeps under the carpet all forms of systemic oppression that the development of capitalism was founded upon, and continues to rely upon, to maintain stable regimes of accumulation, including the disciplining of women’s bodies that was necessary to establish a patriarchal order to guarantee the reproduction of labor power (Federici, Citation2004; Gibson-Graham, Citation2006). It is, therefore, no coincidence that the radical decolonization agenda can gain from interacting with ideas from feminist political economy.

We consider economic theories that choose as their locus this limited and partial understanding of capitalist development as Eurocentric.Footnote1 Notably, despite being founded on a specific ideology and worldview, these Eurocentric theories present themselves as neutral (Harding, Citation2002), which serves to obscure the fact that there are alternative ways of understanding the world that challenge this Eurocentric conception. Such obscuring lays the foundation for claims to universality and neutrality (Grosfoguel, Citation2013; Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Citation2018a).

This view on decolonization pins the debate at the theoretical and methodological foundations of the field, rather than at the main topics covered. This contrasts with the prevalent blind spots approach, where even when the field introduces neglected topics, such as colonialism, the slave trade, race, and gender, it does so in a way that retains the field’s foundation. This is important because it means that if and when Eurocentric theoretical traditions start to introduce neglected topics this will not necessarily challenge the Eurocentrism of those strands as one can study the same issues from both Eurocentric and non-Eurocentric frameworks. If one follows the insights of radical anti-colonial scholars to accept that imperialism and structural racism are intricately connected to the development of capitalism in Europe (Amin, Citation1974; Robinson, Citation1983; Williams, 1944/1994), then ‘correcting’ a Eurocentric theory simply by introducing race or colonialism as a topic, without critically assessing/challenging the economic system that produces and facilitates it, can become a mere lip-service to decolonization.

From a lens of decolonization, the core of economics appears Eurocentric because it conceives of capitalism as a rational, organized system with laws that are ideally supposed to function in the same way everywhere, albeit with certain aberrations, imperfections, and the need of management, and then advances this understanding as objective (Zein-Elabdin & Charusheela, Citation2004). In this understanding, the contradictions and antagonisms that are centrally embedded in capitalism as a system, both in its genesis and expansion, remain absent or peripheral. These Eurocentric underpinnings became increasingly hidden with the formalization of neoclassical economics in the 1950s, when social and historical contexts of capitalist development that provided space to identify such contradictions were gradually removed from economic analyses (Fine & Dimitris, Citation2009). With this development, the field moved further away from considering the economy as a social structure toward a more limited view centered on methodological individualism (Alves & Kvangraven, Citation2020). Furthermore, since the 1970s, there has been an active exclusion of heterodox theories, including those whose theoretical building blocks might be more amenable to studying societal processes and the ingrained antagonism and contradictions in capitalism, narrowing the mainstream of the field even further (Lee, Citation2009). There are, thus, several interlinked ways the field has evolved to deepen its Eurocentrism, related to theory, epistemology, and the politics of knowledge (re)production—a few illustrations of which we outline below.

Firstly, the mainstream of the field has become theoretically narrow, largely relying on neoclassical foundations such as rational (and consistent) economic actors, perfectly functioning markets, and economies in equilibrium as its starting points. Even when these understandings are revisited in the recent decades in terms of introducing imperfections and expanding the definitions of rationality, or the behavioral turn in economics, it has, arguably, failed to break away from these neoclassical tenets (Madra, Citation2017). Embedded in this theoretical foundation is methodological individualism, where units such as agents, firms, and households are considered independent units (although, at times, being endogenously impacted) rather than as mutually co-constitutive parts of a social structure. In a similar vein, even when institutions and culture are introduced to this framework, their roles are limited to either acting as a constraint on rational behavior or as causes that impact individual rationality, thereby leaving the capitalist notion of modernity and rationality unquestioned (Zein-Elabdin, Citation2009). Such an individualizing theoretical paradigm makes it challenging to see structural inequalities, exploitation, and domination (Tilley & Shilliam, Citation2017), interaction of the economic with other social processes, and other inherent contradictions under capitalism, which are much more likely to reveal themselves if one were to begin with social relations—an entry point employed in many heterodox theories (Alves & Kvangraven, Citation2020; Wolff & Resnick, Citation2012). That said, the mainstream of economics is certainly not the only body of scholarship that is founded on Eurocentric principles—such challenges are to be found in strands of heterodoxy (Kayatekin, Citation2009) and IPE (Hobson, Citation2013) as well.

Secondly, alongside this theoretical narrowing of the field, there has also been an epistemological change, as economists have increasingly come to think of themselves as ‘objective’ modelers, analyzing economic phenomena with the help of mathematical deduction, laws, or uniformities, or as empiricist researchers whose primary concern is empirical ‘rigor’ in analyzing narrow interventions (Lawson, Citation1997). The field’s quest for such objectivity and rigor has strengthened the field’s claim to being apolitical and ahistorical (Kayatekin, Citation2009). This has in turn made it increasingly difficult for scholars within it to grasp the Eurocentric biases implicitly present in the empirical categories seamlessly employed, and to consider the heterodox approaches that challenge this neutrality as legitimate starting points for knowledge generation. This trend has been particularly strengthened in recent years with the ‘empirical turn’ of the field (Angrist & Pischke, Citation2010), which culminated in a recent Economics Nobel laureate likening economists to plumbers, thus suggesting that economists’ work is purely technical (Duflo, Citation2017). American IPE has gone through a similar empirical turn (Cohen, Citation2008).

Despite the field’s quest for objectivity and rigor, the narrow approach to empirical phenomena that this has come to entail is in line with what Harding (Citation1992) would call ‘weak’ objectivity, where research rests on technique rather than a reflection on understanding processes and mechanisms and their implications for understanding the society we live in, the vantage point from which the researcher is theorizing and how research questions are formed. Where mainstream economics if often presented as simply ‘economics’, instead of elaborating on the politically contested standpoint from which theorizing takes place, a feminist approach to science argues that by making one’s standpoint clear, one can improve the objectivity of the scientific enquiry. Indeed, Harding argues that the strongest form of objectivity is one that includes all standpoints to enable the revelation of different aspects of truth. Similarly, Nelson (Citation1995) insists that what the mainstream of economics considers objective methodologies does not protect economics against biases, but rather constrains economic analysis.

Decolonizing economics

There are two key tasks that stand before us if we want to decolonize economics.Footnote2 The first is to unpack the mainstream of the field itself to understand how it may generate and perpetuate Eurocentrism. While this is a mammoth intellectual task that needs further development, we outlined a few illustrations of this in the section above. The second is to explore and center non-Eurocentric ways of understanding the world, which include economic knowledge that takes non-Eurocentric theoretical, philosophical, and methodological apparatuses as their starting points (de Santos, Citation2014). Such non-Eurocentric understanding would also allow for a centering of structural forms of oppression such as imperialism, dispossession, and racism as important forces that need to be grappled with to understand how the contemporary global economy is shaped (Mendoza, Citation2016). Indeed, identifying the biases in theory that concealed exploitation globally informed a lot of Latin American intellectuals’ desire to decolonize the social sciences in the 1970s by constructing alternative theories and frameworks to the dominant orthodoxies of the center (Kay, Citation1989).

A radical decolonization agenda does not aim to replace Eurocentric views with other universal projections, but rather seeks to reveal that different theories, and their theoretical building blocks, privilege certain ways of understanding the world, obfuscate and reveal selective aspects of economic processes, and, crucially, have distinct political implications. Given the dominance of Eurocentric theories, one key task for the decolonization agenda thus also becomes to ‘provincialize’ the Western experience (Chakrabarty, Citation2000). As we note this, we must hasten to add two quick clarifications. First, the call to decolonize is not a call for pluralism per se, although pluralism aligns with questioning the universalization of knowledge. Decolonizing social sciences means to recognize that a theory produces a partial explanation of a multidimensional social totality (Wolff & Resnick, Citation2012), and that certain theoretical frameworks and certain vantage points can provide more relevant perspectives than others, depending on the research question at hand (Gibson-Graham, Citation2006; Harding, Citation1992; Hartsock, Citation2006). Second, decolonization entails making space for frameworks that can help shed light on processes related to decolonization in the real, material world, and are, therefore, more amenable to uncover structural inequality and oppression. Frameworks that take social relations—and individuals as entities embedded in and mutually co-constituting social structures—as a starting point are likely to provide relevant answers for such a task. For example, Marxist analyses of class lend themselves to revealing exploitation even in the most perfectly competitive capitalism or the embedded tendencies of crisis under capitalism, which neoclassical frameworks do not lend themselves to.

Furthermore, from a radical decolonization perspective informed by feminist IPE, if one wants to uncover the oppressive processes that have been camouflaged by the Eurocentrism of the field, one must take into account the standpoint of the oppressed (Harding, Citation1992; Hartsock, Citation2006; Mendoza, Citation2016; Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Citation2015). Moreover, outlining one’s perspectives and positionality (Kaul, Citation2008) allows the advancement of a more holistic understanding that is in line with Harding’s ‘strong objectivity’. Note that this is not necessarily about privileging anything that comes from the Global South over the North in geographical terms, but rather to make space for theorization of the same process from the vantage point of the marginalized.Footnote3

While allowing for theorizing from a diversity of vantage points has become increasingly difficult in economics because of the narrowing of the field since the 1970s, theorization from the vantage point of the Global South is particularly marginalized (Mignolo, Citation2010). This is true even among researchers in or from the Global South, given that scholars from the Global South travel to the North for training in Northern intellectual frameworks, to then get published in Northern journals (Hountondji, Citation1997). The relatively recent rise of randomized control trials (RCTs) in development economics, where Northern intellectual and methodological frameworks are held up as a ‘gold standard’ to test the impact of interventions in the Global South, has strengthened this colonial pattern (Kvangraven, Citation2020).

Harding’s (Citation1992) call for increased objectivity is also relevant for methodological entry points. That is, to decolonize economics, being explicit about what methodological assumptions are being made is important, as this will impact the choice of categories and variables, as well as the collection and interpretation of data. This stands in sharp contrast to the dominance of empiricism in economics today. For example, while development economists employing RCTs have repeatedly claimed that their results ‘are what they are’ (Banerjee et al., Citation2007), feminist economists have demonstrated how project design and theoretical framing matters drastically for RCTs’ interpretation (Kabeer, Citation2020). Empiricist accounts prevalent in the mainstream of the field thus remain within what Harding (Citation1992) calls ‘weak’ objectivity. In contrast, non-Eurocentric scholarship often employs methodologies that are not as deterministic as controlled experiments, that do not focus simply on isolating specific variables to prove causation, and that do not obscure systemic and structural oppression by focusing solely on the individual as the most relevant unit of analysis. Instead, non-Eurocentric scholarship often uses data as illustrative in context of a broader theoretical debate, explores the nature of structural relations which are intimately connected, and many seek to unpack the processes through which economic categories used in empirical analysis are produced and normalized (Kay, Citation1989; Smith, Citation1999).

Colonization and decolonization of economics pedagogy

While decolonizing teaching is the natural companion to decolonizing social science, Bhambra et al. (Citation2018, p. 3) find that the relationship between coloniality and pedagogy is ‘deeply understudied’. Despite there being some, albeit limited, awareness in economics research, economics teaching in particular has not yet been subjected to critique from a lens of decolonization. In this section, we delve into how economics teaching is Eurocentric before exploring potential ways to decolonize it.

How is economics teaching eurocentric?

Generally, the core of the economics curricula is fairly standard across the world and has some almost universal features, such as micro and macro theory courses, supplemented by applied options, and a heavy reliance on textbooks.Footnote4 Undergraduate textbooks, which is the first—and for many the only—formal introduction to economics for students, reflect the colonial dimensions of the field highlighted in the previous section. They present economics as a universal and neutral science with little discussion of power and relations of domination as constitutive of the current socioeconomic system. Furthermore, they tend to present economics as a set of principles to be learned, such as ‘markets are usually a good way to organize economic activities’ or ‘governments can sometimes improve market outcomes’ (Zuidhof, Citation2014, p. 175). This is in line with the economics field’s sustained focus on training students to ‘think like an economist’ (Mankiw, Citation2020). As Stilwell (Citation2006, p. 43) points out, teaching students to think ‘like an economist’ only provides students with a ‘sub-set of a broader array of possibilities for understanding the economy in practice’ and it requires students to fit economic questions into pre-existing frames. The foundational textbooks also continue to take economies in the Global North with perfect markets as a benchmark, assessing alternative realities only in relation to this utopia, rather than on their own terms (Zuidhof, Citation2014). Some later revisions to economics textbooks (e.g. CORE, Citation2016) have engaged with these criticisms by centering imperfections rather than perfections and by focusing on tools to analyze the economy (to describe the world ‘as it is’). However, when not engaging with perfect competition representing a normative idea in economics and simply replacing it with a positive representation of the ‘world out there’, such attempts fail to reverse the depoliticization of economics teaching. Furthermore, such attempts present economics mostly as a set of tools and fall markedly short of exposing students to the fundamental differences in distinct theoretical frameworks (neo-classical, Marxian, Keynesian) for understanding economic phenomena and their implications.

This approach to economics teaching has not gone uncontested. Many movements in the Global South are at the forefront of calls to restructure and decolonize the university by questioning the manifestations of racial, colonial, and patriarchal power in universities. Indeed, the most recent movements to decolonize the university originated in South Africa. There, the student protest movement, which was originally directed against a statue of Cecil Rhodes on the University of Cape Town campus, ended up receiving global attention and having reverberations across the world, including in the United Kingdom (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Citation2018b). These movements are tied to concrete demands for ways that universities and teaching should be reformed.

What does decolonizing economics teaching entail?

We have identified three central issues to consider when evaluating how to change what and how we teach. The first issue is to embed our understanding of the economy within broader social processes, given that a central critique of economics teaching is the treatment of the economy as a separate entity instead of analyzing social structures such as relations of domination and exploitation as a part of the economy (Earle et al., Citation2016; see Mantz, Citation2019 for a similar critique of IPE). Indeed, this sole focus on ‘the economic’ may be why economics has become the least interdisciplinary social science field (Fourcade et al., Citation2015) and rather engaged with other disciplines through economics ‘imperialism’ (Boulding, Citation1969)—the practice of seeking to engage with traditionally ‘non-economic’ processes through the lens of neoclassical economics. An example of this is the work of Economics Nobel laureate Gary Becker (Citation1976), who introduced market-like economic interaction to explain social behavior (e.g. marriage). Another example is the individual-based understanding of discrimination in economics, which is based on preferences (as in taste-based discrimination) or rational choices (as in statistical discrimination) made by individuals, which disregards rich heterodox and political economy scholarship on how structural factors facilitate, and are co-constituted by, these inequalities (Kvangraven & Kesar, 2020). Therefore, decolonizing economics teaching would entail creating space for studying approaches that see social structures as co-constitutive of economic processes.

The second issue is to challenge the field’s claim to neutrality and universality and to expose students to different theoretical entry points and their implications. Challenging the field’s neutrality involves presenting various economic understandings as borne out of theoretical and political contestations, not relying on one single authoritative voice, perspective, or approach (Dennis, Citation2018), and exposing how knowledge production in the field itself—including on the history of economic thinking—is embedded in unequal power relations (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Citation2018a). Relatedly, challenging the field’s claim to universality entails going beyond demonstrating the political and contextual aspects of knowledge creation to also explore how various epistemological frames may yield different insights and produce distinct understandings of the same economic process. What is more, there is a strong assumption in economics and the social sciences today that contemporary theoretical approaches originate in the Global North, when ideas in the social sciences have always evolved in a multi-directional manner, with ideas often thought of as being of European or North American origin strongly influenced by scholarship and processes across the globe (Helleiner, Citation2021), including in Asia (Hobson, Citation2020) Latin America (Fajardo, Citation2022; Thornton, Citation2021), and Africa (Mkandawire, Citation2010). Thus, challenging the neutrality of economic concepts also involves engaging with the messy and multi-directional history of their evolution.

The third issue is acknowledging the variety of forms of power inequalities that shape socioeconomic processes. While decolonization involves addressing power relations embedded in colonialism, empire, and Eurocentrism (Quijano, Citation2000), it also necessitates acknowledging the variety of power inequalities that exist within communities across the Global North and South, including gender, race, caste, and class (Alves et al., forthcoming). In that sense, decolonization presents a fundamental critique of power in all its forms and manifestations.

These three points relate directly to what and how we teach. In terms of what we teach, decolonizing the curriculum has been a concrete demand from the decolonization movements. These movements have made it increasingly visible that the content of university syllabi continue to remain principally Eurocentric and reproduce and normalize colonial hierarchies (Peters, Citation2015). Teaching about the role of empire and colonialism in shaping societal outcomes and exposing students to theoretical frameworks that are more amenable to capturing such processes is one concrete way that economists can move away from Eurocentric understandings of global history and social relations (Tejeda et al., Citation2003; Zembylas, Citation2018). While some of these calls have been reduced to diversification—challenging the origins and identities of the scholars on the curriculum—radical calls for decolonization recognize that location outside the center or non-whiteness is not a guarantee for epistemic pluriversality (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Citation2015).

Related to calls to diversify and decolonize the curriculum are calls for pluralism—a call that escalated in the wake of 2008, mostly by heterodox economists and economics student movements (Dobusch & Kapeller, Citation2012; Earle et al., Citation2016). However, the calls to pluralize, while focusing on expanding the umbrella of theoretical traditions that the students are exposed to, often do not address the challenge of how (and why) to choose a particular theoretical entry point, and the relationship between the theories presented and Eurocentrism. Indeed, calls for pluralism alone risk resulting in ‘a pluralization of voices that leaves Eurocentric frameworks intact’ (Pradella, Citation2017, p. 147). In contrast, calls to decolonize specifically require that the Eurocentric underpinnings of different theoretical and methodological approaches are laid bare. When doing so, competing understandings of rigor and objectivity can also fruitfully be presented, which can help students identify which theoretical and methodological frameworks may be more amenable to advancing decolonized knowledge. Calls to decolonize teaching, thus, counter Eurocentric epistemic monocultures by identifying ‘other knowledge and criteria of rigor and validity that operate credibly in social practices pronounced nonexistent’ (de Santos, Citation2014, p. 176). This is also in line with calls to re-politicize the process of knowledge creation by bringing to fore the implications of competing frameworks.

Decolonizing the curriculum also entails presenting knowledge in their colonial and postcolonial contexts (Dennis, Citation2018). This may involve providing a better understanding of economic history (James, Citation2012), history of economic thought (Tavasci & Ventimiglia, Citation2018), and the mixed origins of economic ideas (Mkandawire, Citation2010; Hobson, Citation2020). As with all pedagogical reform, how it is done has profound implications for how transformative it is. For example, the way history of thought has been incorporated into the mainstream has often been by presenting the history of thought as cumulative and linear, glossing over disagreements and debates that continue to exist (Mearman et al., Citation2018) as well as their contested origins (Fajardo, Citation2022; Helleiner, Citation2021). Similarly, if decolonization of teaching is limited only to certain aspects of the pedagogical experience, such as the curriculum, it may risk being severely limited and fail to challenge the status quo in a fundamental manner (Moosavi, Citation2022).

In terms of how we teach, decolonial pedagogies can fruitfully draw on critical pedagogies. Mainstream economics tends to be taught through an instrumental approach to pedagogy, rather than a critical, liberal or decolonial approach (Mearman et al., Citation2018). Instrumental pedagogy involves students being trained in concrete, identifiable skills, such as problem solving, specific techniques, knowledge of facts, and perhaps knowledge of how to apply theory. While all education will involve some instrumental outcomes (e.g. students remembering facts or equipping them with tools), only an education specifically with instrumental goals as an end in itself is usually considered ‘instrumentalist’.

Freire (1970/2017) critiqued such approaches to education for limiting students’ critical thinking by treating students as empty containers into which educators should place knowledge. Instead, he promoted critical pedagogy, which aims to liberate those oppressed by the system (Freire, ibid; see also hooks, Citation1994). Critical pedagogy is student-centered and involves unpacking and critiquing everyday concepts in a process of promoting conscientization, which is also in-line with decolonial pedagogy. Decolonial pedagogy also concurs with feminist standpoint theory that all knowledge comes from somewhere (Dennis, Citation2018; Kaul, Citation2008), which means the politics and position of the scholar and theoretical tradition should be exposed. Decolonial pedagogies both open avenues for viewing learning as a transformative process and for recognizing the politics of knowledge creation.

Decolonizing economics in practice: a survey

To explore how economists teach in the classroom, their attitudes to pedagogy, and the constraints they face, we conducted a survey of economists in top departments of economics, heterodox/pluralist economics, politics, and development studies.Footnote5 The survey is an operationalization of the insights from the decolonization agenda as well as the debates about economics teaching discussed above. It includes both questions about identifying problems with economics education and how they relate to the decolonization agenda, and questions investigating if and how economics education should be reformed. 498 economists based in over 20 countries responded to the survey, though with a strong overrepresentation of US and UK universities, given their overrepresentation on university rankings.Footnote6 Note also that the respondents from the Global South accounts for only 5 percent of the sample and needs to be noted while interpreting the results.

Identifying the problem

We begin by asking whether there is a problem with economics education, and if yes, what the nature of that problem is. The responses, interestingly, largely center around issues that do not challenge the essence of the field, such as adding more empirical cases, interdisciplinarity, economic history and history of thought, while retaining the core curriculum (). In short, they do not support the three principles we identify above—situating economic thinking within broader societal processes, challenging the field’s claim to neutrality and universality, or introducing a way to expose and challenge power inequalities in economic thinking. Despite the many relatively non-controversial options available (e.g. lack of interdisciplinarity) and having the option to define other problems aside from those listed, a relatively high proportion of economists (16 percent) responded that there is no major problem with economics education. However, while only 3 percent of economists in heterodox/pluralists and 10 percent in non-economics departments reported that ‘there is no major problem’, 23 percent of economists in mainstream departments respond the same.

Table 1. Do you think there is a problem with traditional Economics education?a

We employ a logit regression to estimate how the likelihood to identify a problem with economic education varies with the respondent characteristics (, Model 1). The categorical dependent variable takes value 1 if the respondents do not identify any major problem and 0 if they do. We find that even after controlling for a vector of characteristics (represented as vector X in the rest of the paper), which includes geography, gender, racial/ethnic minority status, and seniority (proxied by years since PhD), the respondents teaching in mainstream departments were much more likely to not identify any major problem with economics teaching, compared to respondents in pluralist/heterodox and non-economics departments (including development studies, political economy, political science). Note also that more senior academics were relatively more likely than junior to not identify a problem with economics teaching.

Table 2. Logistic estimation; dependent variable for each specification listed below.

To identify specific problems, the survey asked about perception toward common methods of teaching in economics, such as the ‘textbook approach’ and teaching students to ‘think like an economist’, which reflect the tendency among economists to teach economics as if it is a neutral and universal science abstracted from broader societal processes and power. Both approaches involve privileging a set of implicit theoretical assumptions associated with (late) neoclassical economics.

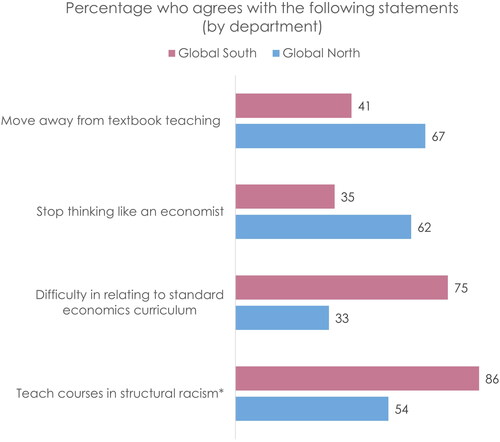

First, the respondents were asked for their agreement with the statement ‘We need to move away from the textbook approach if we are going to be able to teach students to think critically and independently’. 32 percent agreed with this statement (versus disagree/neutral), while 29 percent of the respondents disagreed (). Breaking down the answers by department, we see that it is the economists in mainstream departments driving the enthusiasm for the textbook approach, with respondents from non-economics departments being the most opposed.

Figure 1. Evaluating various aspects of economics teaching, by department.

Full statements respondents were asked to evaluate:

(1) We need to move away from the textbook approach if we are going to be able to teach students to think critically and independently.

(2) We need to stop teaching students to ‘think like an economist’ and rather teach them that there are many equally valid ways of thinking about economic phenomena.

(3) Do you find it difficult to relate the standard economics curriculum to the specific country or socioeconomic context in which you teach?

(4) Do any of the courses you teach allow for an understanding of structural racialized inequalities and/or the role of European colonialism in shaping economic outcomes?

The difference remains significant after controlling for the set of characteristics identified above (represented as vector X above) and estimate the difference using a maximum likelihood (logit) estimation. On average, ceteris paribus, economists in heterodox/pluralist departments are twice as likely, and those in non-economics departments were almost 3.5 times as likely, to respond in favor of moving away from a textbook approach relative to those in mainstream departments (, Model 2). Further, women and respondents from the Global South were also much more likely to respond that it is necessary to move away from the textbook approach (; ). However, note that the sample from the Global South is thin, making it difficult to assess whether geographical base is a good predictor.

Furthermore, only 23 percent of economists in mainstream departments agreed with it being necessary to ‘stop teaching students to think like an economist’, while 60 and 56 percent of economists in heterodox/pluralist and non-economics departments, respectively, said the same (). The difference is significant even after controlling for other characteristics, with odds of being critical of training students to think like an economist being almost 5 times higher for non-mainstream economics and non-economic departments (, Model 3). Further, 62 percent of respondents in the Global South agreed with the need to stop teaching students to think like an economist, versus 35 percent from the Global North (). However, the difference between Global North and South are not statistically significantly different after controlling for other characteristics (X as identified above), which may not be surprising given that the thin sample from the Global South . Note also that economists with more than 30 years since their PhD were less likely than more junior academics to agree that we need to stop teaching students to think like an economist.

The resistance to moving away from a textbook approach and training students to think like an economist points either to ignorance of the existence of distinct approaches to studying economics or to a belief that the dominant paradigm is, in fact, the best framework for teaching about the world. Such a resistance to other ways of teaching and seeing the world is squarely in line with the discipline’s claim to neutrality and universality, which makes radical decolonization challenging.

Furthermore, our results demonstrate that economists from pluralist/heterodox departments, as well as economists in non-economics departments, are significantly more likely to respond that they find it difficult to relate the standard economics curriculum to the specific country or socioeconomic context in which they teach (). 75 percent of respondents based in the Global South responded that they found this difficult, versus only 33 percent of those based in the Global North. This might not be unexpected since a lot of textbooks are contextualized in a Global North setting and exported globally often without any tailoring. These results are significant, even after controlling for the respondents’ other characteristics (, Model 4). Interestingly, junior academics were also significantly more likely to find it difficult to relate the economic curriculum to the socioeconomic context in which they teach.

When it comes to whether the courses economists teach allow for an understanding of structural racialized inequalities and/or the role of European colonialism in shaping economic outcomes, we find that while 87 percent and 84 percent of economists in heterodox/pluralist departments and non-economics departments, respectively, were likely to teach courses that allow for such an understanding, the corresponding figure for those in mainstream departments was merely 38 percent (). This result, while particularly striking, may not be surprising, given the individualizing paradigm of mainstream economics reduces racism to individual actions, while hiding structural forms of oppression (Tilley & Shilliam, Citation2017). Here, the logistic regression (, Model 5) suggests that the odds of those from heterodox/pluralist as well as those from non-Economics departments responding yes are more than eleven times higher relative to those in the mainstream department, indicating that the former were more likely to teach about racialized inequality and colonialism. Moreover, the odds for those based in the Global South, relatively more senior academics, and women to teach such courses is significantly higher than those based in the Global North, relatively more junior academics, and men, respectively. The differences between junior and senior academics may suggest a generational shift in engaging with such questions in economics teaching.

Finally, the time required for technical training comes up as the most common answer to the main constraints to reforming economics teaching (). This striking finding resonates with a worry expressed by the American Economic Association on the Graduate Education in Economics (COGEE) over three decades ago: ‘the commission’s fear is that graduate programs may be turning out a generation with too many idiot savants skilled in technique but innocent of real economic issues’ (Krueger et al., Citation1991). Despite this strong conclusion, there appears to have been an increased prioritization of technical training in mainstream economics teaching. This is also in line with a recent survey, which found that UK employers consider economics graduates to have strong quantitative skills but to not know how to apply them to real world problems (Giles, Citation2018).

Table 3. What are the main constraints to reforming Economics teaching, in your own experience? (by department, in percentages).a

Identifying solutions

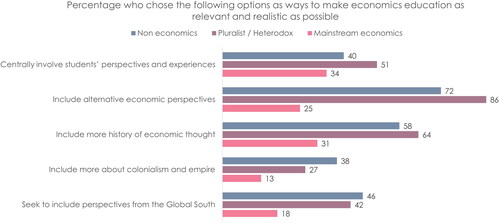

To identify how to address the problems identified, we asked the respondents for ways to make economics education as relevant and realistic as possible ().Footnote7 The ‘give students realistic/real case studies’ dominates the answers. Notably, the top answers with more than 200 respondents are about providing case studies (empirically motivated reforms), including readings from other disciplines (interdisciplinarity), including alternative economic perspectives (pluralism), moving away from mathematics (methodology), including more history of economic thought, and embedding teaching in economic history. While welcome reforms, none of these directly challenge Eurocentrism. Instead, these ways of addressing the problems in the field retain the dominant frameworks while patching ‘blind spots’.

Table 4. Percentage who chose the following options as ways to make Economics education as relevant and realistic as possible.a

Strikingly, the least voted answers were those that dealt directly with aspects of decolonization as identified above, such as challenging neutral expertise, integrating colonialism and empire, and seeking to include perspectives, scholars, and case studies from the Global South (the only answers chosen by less than 150 respondents). The answers that have to do with critical pedagogy—shifting assessments and involving students’ experiences in the courses—were somewhat more popular. What is more, we find that economists in mainstream departments appear the most resistant to attempts to center non-Eurocentric perspectives or alternative ways of understanding economic theory (). Few respondents chose not knowing how to decolonize the curriculum or not having resources as one of the main constraints.

These results are in line with the most recent attempt to reform economics teaching through the launch of the Curriculum Open-access Resources in Economics (CORE), which around half of our survey-respondents believed to be an improvement over standard economics curricula. CORE—an educational reform project led by many top economists—in many ways represents how the mainstream has moved on pedagogy since the global financial crisis. However, CORE’s e-textbook mainly allows for deepening of technical knowledge to be applied to real-world data, rather than critically broadening the curriculum to introduce competing theories and approaches (Mearman et al., Citation2018). Notably, such a focus on empirical analysis without critical discussion of the biases in various theoretical and methodological approaches suggests to students that empirical observation is theory-free.

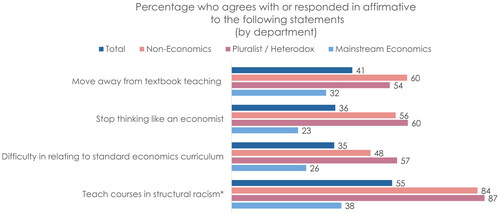

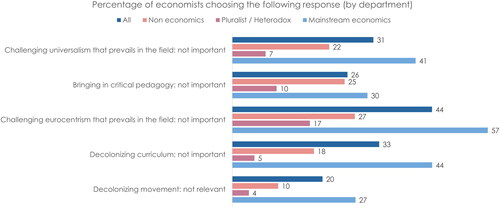

Taking this forward, we asked ‘what aspects of the movement to decolonize science, if any, do you find to be the most relevant for improving Economics education and teaching, especially in your own course(s)?’ The respondents could choose a maximum of three options out of ‘challenging eurocentrism’, ‘challenging universalism’, ‘Bringing in historical context to economic theories and concepts’, ‘Taking positionality, relationality and difference seriously’, ‘Equipping students with tools to question existing power structures and norms’ and ‘They are not relevant’. While the top options chosen deal with bringing in historical context and equipping students with tools to question power structures, 28 percent of economists in mainstream departments said the question was not relevant (versus only 4 percent in heterodox/pluralist departments). Following the same pattern, the logit regression, which controls for other characteristics, suggests that economists in heterodox/pluralist and non-economics departments were significantly less likely to say that efforts to decolonize are not relevant. Women respondents were also significantly less likely to respond that such efforts are not relevant (, Model 1). Again, this suggests more openness among women and economists in non-mainstream departments toward applying principles of decolonization in economics teaching.

Table 5. Logistic estimation: dependent variable for each specification noted below (odds ratio).

Next, we analyze what our respondents think about the ‘importance of challenging the Eurocentrism that prevails in the field’. The respondents could choose two options among ‘Unpacking how Eurocentrism in Economics arose and in what ways it persists’, ‘Challenge Eurocentric portrayals of the “developing world”’, ‘De-canonizing and de-centering the Eurocentric mainstream (e.g. by teaching non-European economic theories)’ and ‘I don’t think this is important.’ Notably, over half of respondents from mainstream departments said it was not important (57 percent), versus only 17 percent of respondents from heterodox/pluralist departments and 27 percent from non-Economics departments. The results stand even after we control for other characteristics such as sex, ethnicity, years after PhD, and geographical location (, Model 3). Furthermore, women are twice as likely to respond that it is important to challenge the Eurocentrism that prevails in the field compared to men, and respondents further out of their PhD (15 years or more) are more likely to say that this was not important compared to junior respondents. This trend needs further exploration but may suggest that the younger generation of economists are more attuned to challenges related to decolonization, when compared with senior academics, many of which have played a formative role in ossifying the narrow boundaries of the discipline.

When asked specifically about decolonizing the curriculum, 33 percent of the respondents replied that decolonizing the curriculum is not important. Here, too, economists in mainstream departments were significantly more likely to not find it important, as were men relative to women, and more senior economists relative to more junior (; , Model 2). This is also reflected in terms of bringing in critical pedagogy, which, as we argued in the previous section, is a key constituent of the decolonization agenda. Again, economists in heterodox/pluralist departments as well as women are less likely, while economists that received their PhD 30 or more years ago are more likely than their counterparts to say that this is not important (; , Model 4). Similarly, in terms of challenging the universalism that prevails in the field, economists in heterodox/pluralist and non-economics departments as well as women respondents are less likely to say that this is not important (; , Model 5). While there was generally not much enthusiasm for reforms associated with critical pedagogy, heterodox economists were no doubt the most concerned with ‘teaching students to be critical of their own field’ (13 percent of economists in heterodox/pluralist departments considered this important versus 6 percent in mainstream).

Figure 4. What aspects of the movement to decolonize science, if any, do you find to be the most relevant for improving Economics education and teaching, especially in your own course(s)?

The survey suggests some substantial differences between economists’ attitudes to economics and pedagogy based on both their gender and location. For example, women are more likely to respond that it is important to challenge the Eurocentrism that prevails in the field, they are less likely to say that bringing in critical pedagogy is not important, and they are more likely to say that challenging universalism is important, than men. Meanwhile, respondents from the Global South being more likely to say that we need to move away from the textbook approach, that they find it difficult to relate the standard curriculum to their socioeconomic context, and to say their courses allow for an understanding of structural racialized inequalities and/or the role of European colonialism in shaping economic outcomes, suggests that location may also be an important factor shaping economists’ attitudes. However, for many of the responses, there are no significant differences between respondents from the Global North and the South, which may also not be that unexpected an outcome, given that most institutions in the South also work within the same global hegemony and are often under an even higher pressure to emulate the mainstream (Hountondji, Citation1997; Kesar, Citation2020). Furthermore, this also underscores the point that decolonization is not simply about geographical location per se, but rather about the theoretical and methodological vantage point. However, while our results suggest that the drive to decolonize economics pedagogy appears to neither be primarily driven by scholars in the Global South nor the Global North, further research is required to include a larger sample from the Global South to establish the extent that variation in location makes a difference.

Concluding reflections

The historical anchoring in a Eurocentric worldview of the economics field and key strands of IPE has had a dramatic impact on how the field is taught and how socioeconomic realities are shaped. However, the survey results presented in this article demonstrate that economists in the mainstream of the field appear to not be particularly convinced by reforms to economics education that are associated with calls to decolonize. Indeed, the survey demonstrates that scholars in top economics departments tend to favor narrow and instrumental approaches to teaching economics and that they see the need for more technical training in economics education as an important constraint to any attempt to change economics teaching. This view of economics teaching stands in contrast to the three central aspects of decolonizing economics teaching identified in this article, namely placing the economy within broader societal processes, challenging neutrality, and universality, and recognizing power inequalities. The results suggest that the continued dominance of narrow theoretical and methodological approaches in economics and certain strands of IPE, along with claims to neutrality and universality, constitute major obstacles to decolonization of teaching.

Nonetheless, these findings, while providing a landscape of the pedagogical practices in economics, also identify some scope for progress. In contrast to the mainstream of the discipline, the respondents in heterodox or pluralist economics departments fared somewhat better in terms of their openness to the decolonization agenda. This should perhaps not be surprising, given many heterodox economists’ and economists in non-economics departments’ explicit focus on structural inequalities between groups, embedded antagonisms in economic and social processes, and structural factors in shaping economic outcomes. However, as the results show, even among heterodox economists, decolonizing economics is not a top priority. This may have to do with the Eurocentrism and universality that is embedded in a lot of heterodox theorizing as well (Kayatekin, Citation2009). Nevertheless, given the centrality of the role of power, structures, and the politics of knowledge creation in heterodox strands and a recognition of multiple entry-points to theory and methods, they lend themselves more easily to a decolonization agenda than the mainstream economic framework does. In other words, decolonizing heterodox economic theory can be a fruitful process, while decolonizing mainstream economic theory may be infeasible. However, the marginalization of heterodox and radical strands makes the task of decolonizing economics even harder. Similarly, for IPE, the marginalization of heterodox approaches such as Marxism, world systems theory and critical geography in recent years may make it more difficult for the field of IPE to address the radical calls for decolonization effectively (Clift et al., Citation2022). While the relatively forthcoming attitude toward decolonizing economics pedagogy of those with a relatively recent entry into academia when compared to those with more senior economists provides hope for a more critical engagement going forward, for those in mainstream departments, even junior academics with a strong commitment to diversifying and decolonizing the field may be constrained by the tight theoretical and methodological boundaries of the discipline.

Decolonizing economics is not simply a question of teaching or even only limited to research and knowledge production. Indeed, there is a strong relationship between Eurocentric science and imperial expansion, as well as with the unequal nature of capitalist development (Amin, 1988/2009; Harding, Citation2002). Even after the fall of the old forms of colonial oppression, advancement of specific kinds of knowledge have been used as a powerful tool by the imperial powers to exert their influence over the rest of the world, for example through legitimizing policies associated with the Washington Consensus, post-Washington Consensus, and the contemporary Wall Street Consensus (Gabor, Citation2021; Rist, Citation1997). Decolonizing economics and IPE teaching must be seen in this context too: a small step toward a more radical project of anti-imperialism and decolonization more broadly. Although taking anti-colonial approaches seriously cannot guarantee increased justice or equality, it can effectively help to undermine and challenge the romanticized view of capitalism in economics and IPE and enable fresh perspectives on marginalization and structural inequalities.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (458.2 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ariane Agunsoye, Carolina Alves, Snehashish Bhattacharya, Danielle Guizzo, Paul Gilbert, Lucia Pradella, and Reinhard Schumacher for their helpful comments, feedback, and suggestions at various stages of this project. We are also grateful to all fellow members of Diversifying and Decolonising Economics (D-Econ) for inspiring efforts and reflections on how to decolonize the field of economics. We are particularly grateful for the continuous discussions with Devika Dutt and Carolina Alves these past few years while working on our book on decolonizing economics. Finally, thank you to everyone who showed support for this project and concerns regarding the results, including participants at conferences and workshops organized by the European Association for Evolutionary Political Economy, the Post-Keynesian Economics Society, the Italian Association for the History of Political Economy, and the American Economic Association.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ingrid Harvold Kvangraven

Ingrid Harvold Kvangraven is a Lecturer in International Development at King’s College, London. Her research is broadly centered on the role of finance in development, structural explanations for global inequalities, the political economy of development, and critically assessing the economics field itself, in particular from an anti-colonial perspective. She holds a PhD in Economics from The New School.

Surbhi Kesar

Surbhi Kesar is a Lecturer in the Department of Economics at SOAS, University of London. Her research interests are in the fields of development economics and political economy of development, focusing on issues of informality and structural transformation in labor surplus economies, issues of economic and social exclusion, and decolonized approaches in economics. She has a PhD in Economics from South Asian University, New Delhi.

Notes

1 See Hobson (Citation2013) and Blaney and Inayatullah (Citation2010) for similar reflections on how IPE can be considered Eurocentric.

2 See Bhambra et al. (Citation2018) for an introduction to the multitude of definitions and interpretations of decolonization in social sciences.

3 For example, Western feminism and African ethics of care are similar in certain aspects because they are a reaction to approaches of Euro-American men (Harding Citation1987/1998). The relevant similarity is that they theorize from the vantage point of marginalization, not their location or cultural origin.

4 Even in countries where economics education has long been known for its heterodox and pluralist curriculum, the neoliberalization of higher education suggests that this is about to change (e.g. Guizzo et al., Citation2021).

5 The ‘top’ of the discipline is defined by the power hierarchies of the field, not by any measure of quality or relevance of the research that those departments produce. We draw on standard rankings of departments of Economics, Politics, and International Development, namely RePEC for Economics and QS World University Rankings for the others. Survey respondents were asked to identify which kind of department they are in, and it is this self-identification we use in the analysis. See Table A8 for the departments surveyed. Also note that there exists a high correlation between a respondents’ training and the department in which they work. For example, of the total economists working in mainstream departments, 85 percent were also trained in mainstream economics.

6 For the composition of targeted institutions, see Table A1 in the online appendix. For the distribution of respondents across disciplinary, geographical, social, and demographic characteristics, see tables A2-A7 in the online appendix.

7 There was no restriction to how many answers they could select, which explains the high percentages.

References

- Alves, C., Dutt, D., Kesar, S., & Kvangraven, I. H. (forthcoming). Decolonising economics – An entroduction. Polity Press.

- Alves, C., & Kvangraven, I. H. (2020). Changing the narrative: Economics after Covid-19. Review of Agrarian Studies, 10(1), 147–163.

- Amin, S. (1974). Accumulation on a world scale: A critique of the theory of underdevelopment. Monthly Review Press.

- Amin, S. (2009). Eurocentrism: Modernity, Religion, and Democracy: A Critique of Eurocentrism and Culturalism. Pambazuka Press (Original work published 1988).

- Angrist, J. D., & Pischke, J. (2010). The credibility revolution in empirical economics: How better research design is taking the con out of econometrics. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 24(2), 3–30. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.24.2.3

- Becker, G. (1976). The economic approach to human behavior. University of Chicago Press.

- Banerjee, A. V., Amsden, A., Bates, R., Bhagwati, J., Deaton, A., & Stern, N. (2007). Making aid work. MIT Press.

- Bhattacharya, S., & Kesar, S. (2020). Precarity and development: Production and labor processes in the informal economy in India. Review of Radical Political Economics, 52(3), 387–408. https://doi.org/10.1177/0486613419884150

- Best, J., Hay, C., LeBaron, G., & Mügge, D. (2021). Seeing and not-seeing like a political economist: The historicity of contemporary political economy and its blind spots. New Political Economy, 26(2), 217–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2020.1841143

- Bhambra, G. (2021). Colonial global economy: Towards a theoretical reorientation of political economy. Review of International Political Economy, 28(2), 307–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2020.1830831

- Bhambra, G., Gebrial, D., & Nişancıoğlu, K. (2018). Introduction: Decolonising the university? In G. Bhambra, D. Gebrial, & K. Nişancıoğlu (Eds.), Decolonising the university (pp. 1–15). Pluto Press.

- Blaney, D. L., & Inayatullah, N. (2010). Savage economics: Wealth, poverty, and the temporal walls of capitalism. Routledge.

- Blaut, J. M. (1993). The colonizer’s model of the world: Geographical diffusionism and eurocentric history. Guilford Press.

- Boulding, K. (1969). Economics as a moral science. American Economic Review, 59(1), 1–12.

- Chakrabarty, D. (2000). Provincialising Europe: Postcolonial thought and historical difference. Princeton University Press.

- Clift, B., Kristensen, P., & Rosamond, B. (2022). Remembering and forgetting IPE: Disciplinary history as boundary work. Review of International Political Economy, 29(2), 339–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2020.1826341

- Cohen, B. J. 2008. International political economy: An intellectual history. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- CORE. (2016). About our e-book. CORE Project, University College London.

- de Santos, B. S. (2014). Epistemologies of the south: Justice against epistemicide. Paradigm Publishers.

- Dennis, C. A. (2018). Decolonising education: A pedagogic intervention. In G. K. Bhambra, D. Gebrial, & K. Nisancioglu (Eds.), Decolonising the university (pp. 190–207). Pluto Press.

- Dobusch, L., & Kapeller, J. (2012). Heterodox united vs. mainstream city? Sketching a framework for interested pluralism in economics. Journal of Economic Issues, 46(4), 1035–1058. https://doi.org/10.2753/JEI0021-3624460410

- Duflo, E. (2017). Richard T. Ely lecture: The economist as plumber. American Economic Review, 107(5), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.p20171153

- Earle, J., Moran, C., & Ward-Perkins, J. (2016). The econocracy: The perils of leaving economics to the experts. Manchester University Press.

- Fajardo, M. (2022). The world that Latin America created: The United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America in the development era. Harvard University Press.

- Federici, S. (2004). Caliban and the witch: Women, the body and primitive accumulation. Autonomedia.

- Fine, B., & Dimitris, M. (2009). From political economy to economics method, the social and the historical in the evolution of economic theory. Routledge.

- Fourcade, M., Ollion, E., & Algan, Y. (2015). The superiority of economists. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 29(1), 89–114. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.29.1.89

- Freire, P. (2017). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Penguin Books (Original work published 1970).

- Gabor, D. (2021). The Wall Street consensus. Development and Change, 52(3), 429–459. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12645

- Gibson-Graham, J. K. (2006). The end of capitalism (as we knew it). A feminst critique of political economy. University of Minnesota Press.

- Giles, C. (2018, July 26). UK economics graduates lack required skills, study finds. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/1ca4c34a-90e3-11e8-bb8f-a6a2f7bca546

- Grosfoguel, R. (2013). The structure of knowledge in westernized universities – Epistemic racism/sexism and the four genocides/epistemicides of the long 16th century. Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge, 11(1), 73–90.

- Guizzo, D., Mearman, A., & Berger, S. (2021). TAMA’ economics under siege in Brazil: The threats of curriculum governance reform. Review of International Political Economy, 28(1), 258–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2019.1670716

- Harding, S. (1998). The curious coincidence of feminine and African moralities. In E. C. Eze (Ed.), African philosophy: An anthology (pp. 360–372). Blackwell (Original work published 1987).

- Harding, S. (1992). Rethinking standpoint epistemology: What is “strong objectivity?” The Centennial Review, 36(3), 437–470.

- Harding, S. (2002). Must the advance of science advance global inequality? International Studies Review, 4(2), 87–105. https://doi.org/10.1111/1521-9488.00256

- Hartsock, N. (2006). Globalization and primitive accumulation: The contributions of David Harvey’s dialectical Marxism. In N. Castree & D. Gregory (Eds.), David Harvey: A critical reader (pp. 167–190). Blackwell.

- Helleiner, E. (2021). The neomercantilists: A global history. Cornell University Press.

- Hobson, J. M. (2013). Part 1 – Revealing the Eurocentric foundations of IPE: A critical historiography of the discipline from the classical to the modern era. Review of International Political Economy, 20(5), 1024–1054. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2012.704519

- Hobson, J. M. (2020). Multicultural origins of the global economy: Beyond the Western-centric frontier. Cambridge University Press.

- hooks, b. (1994). Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom. Routledge.

- Hountondji, P. (1997). Endogenous knowledge: Research trails. Codesria.

- James, H. (2012). Finance is history! In D. Coyle (Ed.), What’s the use of Economics? (pp. 87–90). London Publishing Partnership.

- Kabeer, N. (2020). Women’s empowerment and economic development: A feminist critique of storytelling practices in “randomista” economics. Feminist Economics, 26(2), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2020.1743338

- Kaul, N. (2008). Imagining economics otherwise – Econounters with identity/difference. Routledge.

- Kay, C. (1989). Latin American theories of development and underdevelopment. Routledge.

- Kayatekin, S. (2009). Between political economy and postcolonial theory: First encounters. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 33(6), 1113–1118. https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/bep067

- Kesar, S. (2020). Identity in economics or identity of economics? Miami Institute for the Social Sciences. https://www.miamisocialsciences.org/home/4kjktd9cucyr431igamed9xsdz8gfz

- Krueger, A., et al. (1991). Report on the commission on graduate education in economics. Journal of Economic Literature, 29(3), 1035–1053.

- Kvangraven, I. H. (2020). Nobel rebels in disguise — Assessing the rise and rule of the randomistas. Review of Political Economy, 32(3), 305–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/09538259.2020.1810886

- Kvangraven, I. H., & Kesar, S. (2020, August 3). Why do economists have trouble understanding racialized inequalities? INET. https://www.ineteconomics.org/perspectives/blog/why-do-economists-have-trouble-understanding-racialized-inequalities

- Lawson, T. (1997). Economics and reality. Routledge.

- Lazarus, N. (2011). What postcolonial theory doesn’t say. Race & Class, 53(1), 3–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306396811406778

- LeBaron, G., Mügge, D., Best, J., & Hay, C. (2021). Blind spots in IPE: Marginalized perspectives and neglected trends in contemporary capitalism. Review of International Political Economy, 28(2), 283–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2020.1830835

- Lee, F. (2009). A history of heterodox economics: Challenging the mainstream in the twentieth century. Routledge.

- Madra, Y. M. (2017). Late neoclassical economics the restoration of theoretical humanism in contemporary economic theory. Routledge.

- Mkandawire, T. (2010, April 2). Running while others walk: Knowledge and the challenge of Africa’s development. In Inaugural Lecture, LSE. London School of Economics.

- Mankiw, G. (2020). Principles of economics (9th ed.). Cengage.

- Mantz, F. (2019). Decolonizing the IPE syllabus: Eurocentrism and the coloniality of knowledge in International Political Economy. Review of International Political Economy, 26(6), 1361–1378. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2019.1647870

- Mearman, A., Guizzo, D., & Berger, S. (2018). Whither political economy? Evaluating the CORE project as a response to calls for change in economics teaching. Review of Political Economy, 30(2), 241–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/09538259.2018.1426682

- Mendoza, B. (2016). Coloniality of gender and power: From postcoloniality to decoloniality. In L. Disch & M. Hawkesworth (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of feminist theory (pp. 100–121). Oxford University Press.

- Mignolo, W. (2010). Delinking the rhetoric of modernity, the logic of coloniality and the grammar of coloniality. In W. Mignolo & A. Escobar (Eds.), Globalization and the decolonial option (303–368). Routledge.

- Moosavi, L. (2022). Turning the decolonial gaze towards ourselves: Decolonising the curriculum and ‘decolonial reflexivity’ in sociology and social theory. Sociology. https://doi.org/10.1177/00380385221096037

- Nelson, J. (1995). Feminism and economics. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 9(2), 131–148. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.9.2.131

- Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. (2015). Empire, global coloniality and African subjectivity. Berghahn Books.

- Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. (2018a). Epistemic freedom in Africa – Deprovincialization and decolonization. Routledge.

- Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. (2018b). Why Rhodes must fall. In S. Ndlovu-Gatsheni (Ed.), Epistemic freedom in Africa – Deprovincialization and decolonization (pp. 221–242). Routledge.

- Peters, M. (2015). Why is my curriculum white? Educational Philosophy and Theory, 47(7), 641–646. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2015.1037227

- Pradella, L. (2017). Marx and the global south: Connecting history and value theory. Sociology, 51(1), 146–161. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038516661267

- Quijano, A. (2000). Coloniality of power, eurocentrism and Latin America. Duke University Press.

- Rist, G. (1997). The history of development: From Western origin to global faith. Zed.

- Robinson, C. (1983). Black Marxism: The making of the black radical tradition. Zed.

- Said, E. (1978). Orientalism. Pantheon Books.

- Sanyal, K. (2007). Rethinking capitalist development: Primitive accumulation, governmentality and post-colonial capitalism. Routledge India.

- Smith, L. T. (1999). Decolonizing methodologies research and indigenous peoples. Zed Books.

- Stilwell, F. (2006). Four Reasons for pluralism in the teaching of economics. Australasian Journal of Economics Education, 3(1&2), 42–55.

- Tavasci, D., & Ventimiglia, L. (2018). Teaching the history of economic thought integrating historical perspectives into modern economics. EdwardElgar.

- Tejeda, C., Espinoza, M., & Gutierrez, K. (2003). Toward a decolonizing pedagogy: Social justice reconsidered. In P. Trifonas (Ed.), Pedagogies of difference: Rethinking education for social justice (pp. 10–40). RoutledgeFalmer.

- Thornton, C. (2021). Revolution in development: Mexico and the governance of the global economy. University of California Press.

- Tilley, L., & Shilliam, R. (2017). Raced markets: An introduction. New Political Economy, 23(5), 1–10.

- Wallerstein, I. (1997). Eurocentrism and its avatars: The dilemmas of social science. New Left Review, I(226), 93–107.

- Williams, E. (1994). Capitalism and slavery. University of North Carolina Press (Original work published 1944).

- Wolff, R., & Resnick, S. (2012). Contending economic theories: Neoclassical, Keynesian, and Marxian. MIT Press.

- Zein-Elabdin, E. (2009). Economics, postcolonial theory and the problem of culture: Institutional analysis and hybridity. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 33(6), 1153–1167. https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/bep040

- Zein-Elabdin, E., & Charusheela, S. (2004). Introduction: Economics and postcolonial thought. In E. Zein-Elabdin & S. Charusheela (Eds.), Postcolonialism meets economics (pp. 1–18). Routledge.

- Zembylas, M. (2018). Reinventing critical pedagogy as decolonizing pedagogy: The education of empathy. Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies, 40(5), 404–421. https://doi.org/10.1080/10714413.2019.1570794

- Zuidhof, P. (2014). Thinking like an economist: The neoliberal politics of the economics textbook. Review of Social Economy, 72(2), 157–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/00346764.2013.872952