Abstract

The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) was created in the early 1990s to promote the transition to a market economy and advance democracy in the post-communist countries of East Central Europe. How and why did this international organization, established for an entirely different purpose, then become an active investor in Egypt? Building on field theory, we explain the EBRD’s move to Egypt as an attempt to overcome the hysteresis effect of its anachronistic operational logic (habitus) within a changing field. Once in Egypt, the EBRD aspired to leverage its symbolic capital of technical assistance, democratic commitment and the privileging of the private sector. However, given Egypt’s increasingly autocratic and state capitalist evolution, it found delivering on its symbolic capital problematic. Its solution was to adapt to the very active European development finance field’s modalities. However, the European field’s logic ultimately de-prioritized democracy, human rights promotion, and poverty reduction and instead focused on sustainable investment, migration mitigation and containing Europe’s geo-economic rivals. In our case study, we demonstrate that the EBRD operated deftly within this field, while it also gained permission and even reward for its mandate management. It is a problematic finding for the future of the EU development policy.

Introduction

The weakening of the Bretton Woods system and its multilateral institutions has given rise to a new interest in regional development banks (RDBs) (Lütz, Citation2021; Jędrzejowska, Citation2020). RDBs have been revitalized, such as the European Investment Bank (EIB) in Europe through the investment plan of the Juncker Commission (Mertens & Thiemann, Citation2018), or the European Bank for Restructuring and Development (EBRD) through its expansion into the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). New regional banks have been created, such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the New Development Bank (NDB) of the BRICS countries. Today, RDBs are called upon—and eager—to combat climate emergency, build infrastructure and green the economy (Marois, Citation2021).

The operation of revitalized RDBs should be especially interesting for International Political Economy (IPE) scholars due to their position at the meso level of international politics, where the interplay of global and local factors is most visible. Therefore, it is surprising that, until recently, there has been very little written on RDBs from an IPE perspective. In this article, we contribute to the few existing explorations of RDBs (Clifton et al., Citation2017; Park, Citation2017, Citation2021; Park & Strand, Citation2020; Shields, Citation2019, Citation2020) by examining an RDB’s strategic reaction to the restructuring of the global development finance field. In this study, we connect the EBRD’s practice in Egypt to changes in the European development finance field brought about by the logics of Wall Street Consensus (WSC) and state capitalism (Schindler et al., Citation2022).

Looking at the EBRD is a particularly appropriate case against which to evaluate RDBs’ adaptation to the global restructuring of the field. The EBRD is one of the seven Western-leaning RDBs that contributed to the framing of the World Bank’s From Billions to Trillions: Transforming Development Finance note in 2015.Footnote1 This document contains the key policy scripts that RDBs should follow in order to create bankable projects for global financial investors in the Global South. The EBRD’s participation in framing the agenda also shows its commitments to the World Bank’s ‘Maximizing Finance for Development’ agenda (Gabor, Citation2021). Moreover, the EBRD has been mandated to prefer private-sector lending in countries committed to multiparty democracy and has provided technical assistance from the beginning of its operation. As such, this bank has the most institutional know-how, skills and resources to carry out the World Bank’s new agenda.

From the MENA region—Morocco, Tunisia, Egypt and JordanFootnote2 where the EBRD started operations in 2011—the case of Egypt allows us to best evaluate claims about increasing state capitalism in defining RDBs’ operations (Alami & Dixon Citation2020, Citation2021; Alami et al., Citation2021). Since the downfall of the Arab Spring, the Sisi-led government in Egypt has systematically undermined any attempt at democratization and it also launched the Vision 2030 strategy in 2016. This grandiose investment plan includes the construction of an interconnected system of new ports, logistic centers, roads, railways and industrial zones accompanied by the design and establishment of a New Administrative Capital (NAC) along with a significant transformation of Cairo’s urban landscape (Tawakkol, Citation2020). The EBRD became actively involved in a number of sub-projects within the Sisi regime’s state-led developmentalism. Moreover, Egypt allows us to observe geopolitical rivalries because of the recent arrival of large investments from China, Russia, Turkey and the Gulf States (Roccu, Citation2018b).

We take it as a research puzzle to explain the EBRD’s practice in Egypt. We would like to understand how and why the EBRD—a bank created to advance transitions to private-actor-driven market economies and to promote democracy in post-communist countries in the early 1990s—became an active investor in Egypt in 2011 and advanced lending to Sisi’s authoritarian regime to fund public infrastructure projects. Egypt today is thus strikingly different from the EBRD’s original countries of operation. Yet, on a country-level basis, Egypt’s share of the EBRD’s lending portfolio was the second largest after Turkey in 2021.Footnote3

Combining field theory with an IPE focus (Bourdieu, Citation2005; DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983; Fligstein & McAdam, Citation2012; Leander, Citation2011), we analyze how the EBRD’s operational logic (habitus) reacts to changes in the development finance field. The depletion of its symbolic capital in its (1) technical assistance, (2) private sector and (3) democratization mandates is due to the restructuring of the development finance field in Eastern Europe and Central Asia. This phenomenon is called ‘hysteresis’ in field theory: a disruption between habitus and field (Bourdieu, Citation2000; 160). Moving to Egypt and to the MENA region by the time of the Arab Spring, the EBRD hoped to convert its symbolic capital from liability into asset. Our analysis reveals a re-creation of the mismatch between the EBRD’s habitus and the logic of the development finance field in Egypt. However, over time the EBRD has adapted to the new modalities of the European development finance field. The European development finance field, as it operates in the MENA region, deprioritizes the EU neighborhood policy’s former goals of humanitarian assistance, democracy promotion and human rights and instead embraces goals such as fighting climate change, mitigating migration threats and containing the EU’s geoeconomic rivals. Because the EU field now functions without respect for effective democratic oversight of market economies, it sanctions the EBRD’s own disregard for these values. The EBRD’s problematic mandate management is thus a function of the logic of the European field.

We set this approach against neorealist or neoliberal views, which would only conceptualize the EBRD’s practice in relation to powerful states. These theoretical approaches would expect the EBRD to compose its strategies as reflections of the interests of its most powerful shareholders, namely the US, UK, Germany, France, Italy and Japan (Guzzini, Citation1998; Strand, Citation2003). A narrow principle-agent framework would lead to the wrong conclusion of blaming the EBRD only for a violation of its mandate. Our field-theoretical approach draws attention to the modalities of the European development finance field to explain the EBRD’s problematic mandate management. It is the EU’s development field that leaves little room for the promotion of democracy and democratic oversight over liberal markets.

Throughout our study, we reviewed relevant data sets provided by the EBRD and other development banks, including project summaries (PSDs), country strategies, transition reports and summary datasets. EBRD-provided data are scarce, sketchy, selectively updated, and at times, inconsistent for Egypt (https://www.ebrd.com/egypt-data.html accessed on 6th December 2021). Moreover, we explicitly question the EBRD’s classification of private and public investment in Section 7. Additionally, we engaged with general media outlets which target investor and development finance audiences, official statements of Egyptian state authorities and EU institutions, as well as NGO reports. We also conducted seven semi-structured interviews with EBRD personnel both from its Board of Governance as well as operation managers from its Egyptian and Balkan missions ().

Table 1. List of interviews.

Setting the stage: Regional development banks and field dynamics

The IPE literature on RDBs is still surprisingly limited. A welcome general introduction to RDBs has only been recently published by Clifton et al. (Citation2021). In this volume, regional specialists provide insights into various RDBs, e.g. the African Development Bank (Kraemer-Mbula, Citation2021), the Asian Development Bank (Barjot & Lanthier, Citation2021) or the Inter-American Development Bank (Babb, Citation2021). Among the few IPE analyses of RDBs is the constructivist work of Susan Park, who—in observing norm creation and transformation made in relation to the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF) (Park & Vetterlein, Citation2010) and the nature of global governance (Park & Strand, Citation2020)—analyzes accountability mechanisms in multilateral development banks in general (Park, Citation2017) and in the EBRD in particular (Park, Citation2021). In addition, from a neo-Gramscian perspective, Stuart Shields has exposed the working of the EBRD in Eastern Europe while conceptualizing it as an organic intellectual that stands behind neoliberal reform processes (Shields, Citation2019, Citation2020). We join them by focusing on tensions between RDBs and changing development finance fields.

In the literature, RDBs are usually defined as development banks with an ownership structure and operation connected to a specific region (Park & Strand, Citation2020). Most RDBs were set up in the 1950s and ‘60 s, modeled on the World Bank, and their key function was to generate additional funding for their region. They could fulfill these goals more efficiently than the World Bank because RDBs are historically, culturally and geographically more connected to their specific region (Clifton et al., Citation2021). As a result, RDBs exhibit large organizational heterogeneity which makes it difficult to classify them. Moreover, it would also be misleading to connect all RDBs over time to only one pre-defined region. In fact, RDBs have been known to (re)interpret ‘their’ region of operation quite loosely. They include shareholders or countries of operation from outside their original region and have been quite active in setting new boundaries and legitimating their expansion or withdrawal from different countries, regions or sectors (Park & Strand, Citation2020; Clifton et al., Citation2021).

Today, however, there are a few essential characteristics of RDBs that are key to understanding their practices in the global economy. First, RDBs’ staff usually enjoy larger degrees of autonomy from shareholders than in other international organizations. RDBs are usually controlled by a large number of shareholders with different weights of voting power and different and changing interests in the banks’ geographical regions. This allows staff considerable room to influence the banks’ agendas (Strand, Citation2003). In addition, board members of the smaller RDBs (delegates of member states) remain in these positions for a longer period of time. Arguably, this allows for their greater socialization into the RDBs’ staff cultures. They are thus more likely to ‘go native’ than board members at World Bank (Clifton et al., Citation2021). Moreover, RDBs’ staff also enjoy larger degrees of autonomy from donor and recipient states, private financial markets, NGOs and watchdogs, etc., than the World Bank while working in a field densely populated by various competing actors (Barnett & Finnemore, Citation2004; Weaver, Citation2008).

Second, throughout their history, RDBs have functioned in the background of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund, which set important constraints on RDBs’ operations, but also enable their activities in certain neglected areas. Up until the recent crisis of multilateralism, RDBs left agenda-setting up to Bretton Woods institutions while focusing on carving out a niche for themselves in the economic governance of their region. From the 1980s, when the World Bank focused on conditional program lending backed by the IMF’s own conditionality (Kentikelenis & Babb, Citation2019), RDBs lent less for programs and with considerably less conditionality and oversight than the World Bank (Park & Strand, Citation2020: 5). They addressed the same policy issues as the World Bank, but differed in speed, depth and strategies. However, working mainly under the radar of public opinion (being ‘invisible organizations’ (Shields, Citation2020)), with fewer watchdogsFootnote4 checking their steps, allows them greater room to maneuver in defining their political commitments (Weaver, Citation2008).

Third, and connectedly, RDBs’ operations require them to create a field of like-minded actors whose connections and support they can rely on for their own operation. Lacking the explicit support of global powers, RDBs must learn to co-operate with other multilaterals, private actors and public actors to ensure the success of their operation (loan repayment, conditionality, etc.). From within the field, RDBs build either cooperative or competitive relations and often take over functions from either Bretton Woods institutions or from national development players (Clifton et al., Citation2021). RDBs consequently value negotiations with national actors, technical assistance, and other forms of soft power exercise even more than Bretton Woods institutions. Lacking the overwhelming capacity to set conditions that ensure the repayment of their lending, they favor shaping the social environment as a safeguard. Recently, with the weakening of multilateralism and the rise of China, RDBs can exercise a larger impact on the global development agenda and set the contours of local practices, depending on their own institutional identity (Lütz, Citation2021).

In this article, we take the RDBs’ field dynamic as a starting point to explore RDBs’ practice. This analytical focus allows us to take advantage of a key promise of field analysis for IR/IPE, namely to combine analytically individual agents with their social field to understand the agents’ motivation, various capital and power struggles. This is possible because field analysis is capable of ‘making basic divides—such as public/ private and inside/ outside—part of the analysis rather than its point of departure’ (Leander, Citation2011: 296). Looking at RDBs as part of a development finance field allows us to circle in all relevant agents—irrespective of national boundaries—and point to the field as having a formative impact on an RDB’s practices (Schmitz & Witte, Citation2020). In this way, the development finance field becomes a site of interaction in which agents recognize the field itself and each other as members of the same field (Fligstein & McAdam, Citation2012). The field is defined by the ‘stake at stake’ or the logic of the field’s operation, which agents mutually accept to be the rules of the game (Leander, Citation2011). An individual agent’s disposition (habitus) is derivative of the field’s logic, although they also actively seek to influence this logic as well. Habitus is an agent’s ‘taken-for-granted, unreflected—hence largely habitual—way of thinking and acting’ (Leander, Citation2010). In the case of an RDB, we take its operational logic to refer to its habitus. An agent’s practice becomes meaningful in relation to their habitus and the field logic (Leander, Citation2006). Thus, in the case of an RDB it is not enough to explicate the motivations of its shareholders (principles); the logic of the development finance field within which it operates and the RDB’s corresponding habitus must be evaluated.

Using field theory in the IPE of development finance, we can focus on and explain reactions to a situation when a particular RDB’s symbolic and material capital is depleted, with a profound effect on its habitus, due to changes in the global development finance field. Field theory uses the concept of hysteresis to draw attention to a mismatch between the stability of an agent’s habitus and the changes in the field’s logic. Hysteresis is a disruption between habitus and field that occurs when habitus remains unaltered while 'the field undergoes a major crisis and its regularities (even its rules) are profoundly changed’ (Bourdieu, Citation2000: 160). Thus, in the case of an RDB, hysteresis helps us observe a growing mismatch between the RDB’s operational logic and the changing logic of the field, which importantly weakens the RDB’s position within it. Therefore, over time, the RDB starts actively seeking a way out of this habitus-field mismatch and engages in accommodating strategies. Gradually, the RDB will embrace the new logic of the field as its own habitus, allowing it to manage its symbolic and material capital more effectively. In the case of an RDB, symbolic capital may include its mandate, its defining practice such as technical assistance provision, loan distribution and other financial revenue generating practices.

For our selected case, the EBRD, such a conceptual focus entails discussing how a gap opened up between the EBRD’s operational logic and the global development finance field as it began to change. It allows us to draw attention to how and why the EBRD realized its position was weakened in the field in Eastern Europe and Central Asia. Its undermined position, an increasing existential threat to be closed, urged the EBRD to find new goals and strategies to reduce the problem it faced due to the hysteresis effect. To explain the EBRD’s strategy in Egypt, we follow DiMaggio and Powell (Citation1983). They argue that organizations not only compete with each other, but also draw powerful injunctions from their broader institutional environments about what they should look like and do (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983). Out of three isomorphic mechanisms (coercive, normative and mimetic) in organizational field-defined contexts, we evaluate mimetic adaptation as the most likely option chosen in the highly uncertain context of a new country outside the EBRD’s core region of operation. As DiMaggio and Powell (Citation1983) explain, mimetic adaptation occurs ‘when organizational technologies are poorly understood …, when goals are ambiguous, or when the environment creates symbolic uncertainty’ (p. 151).

While EBRD mimetically adapted its practice to the European field, it also engaged in mandate management. Mandate management occurs when an international organization discovers that its operational field has changed, and its mandate no longer fits the field logic at all or well. Its mandate for existence comes into question and it must, without simply abandoning its previous position in the field or disavowing its prior habitus, which would explicitly call its mandate into question, transform its operations in its operating field. This can involve taking on new activities, proactive public relations management, concept stretching and changes in personnel and expertise, as well as, new cooperative and/or competitive relations with other organizations in the field.

In the following, we map out the buildup of the EBRD’s habitus-field mismatch that weakened its position in the field in Eastern Europe and Central Asia and drove it to seek a new blueprint of operation in the highly uncertain Egyptian context. In the next section, we introduce the European development finance field and its field logic as it operates in the MENA region. We argue that the EBRD mimetically adapts in this new context while it manages (variously gives up and retains) its past practices of democracy promotion, market building and technical assistance as it embraces the new logic of the European development finance field.

The EBRD’s past 30 years: Managing the opening gap between the EBRD’s operational logic (habitus) and field logic

The EBRD came into existence as one of the Western states’ responses to the fall of communism in Eastern Europe. In 1989, French and US-American political leadership (PM Mitterrand and Jacques Attali and President Reagan and James Baker) backed the foundation of the EBRD most strongly (Walker, 1998). In the 1990s, however, Germany came to the forefront as the bank’s largest supporter when the EBRD’s activities corresponded to its own Ostpolitik and the strategy of the German KfW in Eastern Europe (Mertens, Citation2021). The EBRD’s operational logic was defined by the early 1990s’ neoliberalism. It benefited from its endowment with symbolic capital derived from mandates to promote private enterprise and democracy as well as recognized excellence in providing technical assistance in its early years. However, over time, a few critical changes occurred in its field that transformed these assets into liabilities and made the underlying contradictions in them more apparent. In particular, the accession of Eastern European countries to the EU, the coming to power of illiberal politicians, the advancement of state capitalism in Central Asia, and the rise of China weakened the EBRD’s position. At the same time, global development actors embraced the WSC (Gabor, Citation2021), and the EU Commission’s greater reliance on development banks to pursue its geopolitical ambitions presented opportunities for the EBRD to strengthen its position within the field.

The EBRD’s staffs enjoy a considerable degree of autonomy from shareholders which allows it to become reflexive over time toward the bank’s dispositions. The bank has a very large number of shareholders, and they hold considerably divergent views on the bank (Strand, Citation2003). The majority of its shareholders are from the EU (altogether more than 75% of voting shares). However, the EBRD’s largest shareholder is the United States, with 10 percent of voting shares, followed by France, Germany, the UK, Italy and Japan, each with 8.3 percent of voting shares (45 percent in total).Footnote5 Currently, the EBRD has 71 members in addition to the EU and the EIB and includes every borrowing country. From the outset, the management of the bank has been dominated by donor countries (through voting shares and managerial positions) and recipient countries’ influence has been weak (Walker, 1998). The bank’s presidents, its chief economists and occasionally the Chairs of its Board of Governors were key personalities in the bank (Kilpatrick, Citation2020).

Since the early years of the post-communist transition, the EBRD operated in a densely populated development finance field where competing institutions provided similar forms of aid and technical assistance (on the density and propensity of the international aid network, see, Appel & Orenstein, Citation2018; Ban, 2016; Epstein, Citation2008; Orenstein et al., Citation2008; Johnson, Citation2016; Piroska & Mérő, Citation2021). Throughout the 1990s, the policy script to which the EBRD adjusted its practice came from Washington-based institutions, especially from the IMF,Footnote6 due to the region’s looming foreign debt crisis (Ban, 2016). Key actors in the development finance field were Eastern European governments, the IMF, the World Bank, the International Finance Corporation (IFC), the EU through its PHARE (Poland and Hungary: Assistance for Restructuring their Economies) program, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), private donors and governments from all over the world. The EBRD was an important—but by no means key—actor in this field. The economic assistance it distributed in Eastern Europe was much smaller than that of other actors and thus mattered mainly in its symbolic value (Haggard et al., Citation1993). Therefore, EBRD staff had to learn to maneuver between its large and ambitious mandates and its limited financial resources from the outset.

The EBRD’s solution to this dilemma was to put a large emphasis on technical assistance—i.e. to increase its symbolic capital since it lacked material capital. Technical assistance thus became its defining feature. The EBRD developed state institutions, legal frameworks for capital markets, Public Private Partnership (PPP) laws and projects and financed training programs for public personnel (Kilpatrick, Citation2020). However, technical assistance provision came with two caveats that, over time, conditioned its usefulness for the EBRD. First, EBRD-provided technical assistance, through the use of donor funds, tilted the ‘liberal market’ to the advantage of Western investors. The EBRD’s founding documents did not allow the use of the bank’s own capital for the purpose of technical assistance. Instead, it had to be financed through donor funds that the staff brokered out each time it identified a clear purpose and form.Footnote7 However, according to the EBRD’s charters, while the bank’s own capital must be distributed in a market-conforming manner, donors to particular funds can set requirements with regards to the beneficiaries of the funding (interviewee #3). As a result, instead of pure liberal market principles, technical assistance was provided while honoring donor states’ interests and thus through a donor state’s preferred legal and advisory firms. Second, in the EBRD’s practice, technical assistance was disguised as liberal market expertise that post-communist policy makers lacked. Thus, technical assistance was delivered while the quite apparent politics involved in state building remained concealed. Depicted in neutral, liberal terms, quantified and presented as a common practice across several nations, technical assistance made it incredibly difficult to challenge its muted distributional consequences. As such, EBRD-provided technical assistance not only built state institutions to align Eastern markets with Western investors’ interests, but also decreased the capacity and appeal of democratic politics in Eastern Europe.

The EBRD’s mandate contained two additional aspects of its symbolic capital that became problematic over time. First, the EBRD’s particularly narrow development mandate—‘to promote private and entrepreneurial initiative’Footnote8—initially made the EBRD appealing to FDI-hungry Eastern European politicians (although less so to nationalist-conservative political forces (Myant & Drahokoupil, Citation2010)). In the EBRD’s statute, the share of private sector investments had been set at 60%,Footnote9 and the EBRD was vocally proud of its private-sector mindset as its distinguishing feature from other development banks.Footnote10 In fact, the EBRD, in its embrace of private enterprise, occasionally went as far as to conflate economic development with the privatization of state-owned enterprises (Shields, Citation2020). In the privatization of banks and large public utility companies—energy, water, sanitation, transportation, etc.—the EBRD’s equity investments functioned as a reassuring bid for private investors. And as private investors in the capital-poor East almost always meant Western investors, the EBRD functioned as a market-builder for Western businesses through its private sector promotion as well (Jacoby, Citation2010). Until 2020, around 10 percent of total FDI into the region could be linked to the EBRD (Kilpatrick, Citation2020: 316). Thus, the EBRD was among the key actors which shaped the FDI-dependence of Eastern European economies (Medve-Bálint, Citation2014), an achievement that was forcefully questioned by post-crisis illiberal governments.

Second, an additional symbolic capital—the EBRD’s political mandate to assist only countries that are ‘committed to and applying the principles of multi-party democracy, pluralism and market economics’Footnote11—initially ameliorated its position. Having an explicit political mandateFootnote12 is at odds with most other multilateral development banks which are, like the World Bank, prohibited from taking politics into consideration when lending (Weaver, Citation2008: 74). While originally it made the EBRD particularly appealing to Eastern European post-communist governments as a legitimizing force, over time it posed a number of challenges to the EBRD’s practice.

To see the nature of the challenges that its political mandate presented, it is important to review the EBRD’s staff’s own take on this mandate. The EBRD’s view on democracy has been very narrow from the outset (Walker, 1998). Democracy promotion in the practice of the EBRD in Eastern Europe, and later in Central Asia and Russia, never meant the promotion or build-up of social institutions of democratic oversight. Democracy promotion in the form of actively funding democratic actors, institutions, critical press, civil actors, trade unions, etc., has never been seen by the EBRD as part of its mandate. Democracy in the thinking of EBRD staff was to spring from market practice, from the spirit of smallholders, and from the activities of entrepreneurial middle classes (Walker, 1998). EBRD staff could argue that democratic practice had been strengthened by pointing to the neoliberal solutions that they had promoted. Indeed, neoliberal regulations proved effective in important cases (e.g. Estonia) to weaken powerful political actors, curb corruption and halt the economic advances of well-connected businesses (Khakee, Citation2018).

Still, in its ‘state-building as market-building’ efforts (Fligstein, Citation1996), the EBRD mainly focused on those qualities of state institutions that were conducive to growth and neglected institutions necessary to channel the voice of the losers of transition into politics. When pressed to define what exactly it was doing in Eastern Europe, the EBRD’s chief economist defined its tasks in 1997 as, first, ‘the creation, expansion and deepening of markets… the establishment and strengthening of institutions, laws and policies that support the market (including private ownership)… [and] the adoption of behavior patterns and skills that have a market perspective.’Footnote13 Missing from the list are considerations about the redistributive consequences of economic growth and the building of institutions that could channel discontent into the political arena. Strengthening effective democratic oversight was not on the EBRD’s agenda.

Satisfying its political mandate was easier in the 1990s. At that time, it classified most of the countries in its region of operation as ‘on the way to democracy.’ As such, established democratic practices were not necessary conditions for the EBRD to operate in these countries.Footnote14 However, over time, the EBRD found it increasingly difficult to deliver on its democratic mandate. One attempt was made in 2013 to publish a list of 17 qualifying criteria to check in a country of operation. The list includes free and fair elections, media freedom, independent judiciary, independence of civil society and a host of civil liberties.Footnote15 However, this same document advised the staff to consider other contextual factors as well. The advice amounts to a reversal of the democracy mandate in as much as it states that staff should ‘recognise nuances and variety of contexts; effective engagement with the authorities; preserve gains already attained; learn from and take into account the actions of international leading voices on democratic governance (e.g. OSCE, Council of Europe); engage with key, local stakeholders.’Footnote16

In the 2000s, three major changes occurred in the social context of the EBRD’s field that weakened its position. First, the launch of the UN’s Millennium Development Goals (2000 to 2015) refocused global development actors’ attention toward poverty reduction, education, gender equality, child mortality, maternal health, etc. These were goals that were largely missing from the EBRD’s portfolio. The EBRD’s insistence on private enterprise promotion as ‘the key’ to development marginalized the bank in development finance circles (Chakrabarti, Citation2020). Even if the bank experimented with a neoliberalized gender equity program to help women entrepreneurs and supported drinking water provision in the form of public utility development (Wallin, Citation2018; Kilpatrick, Citation2020), the bank’s occasional declarations that public services are inefficientFootnote17 opened a mismatch between the EBRD’s habitus and the logic of the global development finance field.

Second, the EBRD’s shareholders sent the bank to Central Asia, where economic growth projections opened new market opportunities for Western investors (Kilpatrick, Citation2020: 322). However, the EBRD’s operation in Central Asia made its democracy and private enterprise mandates exceptionally problematic. Here, the bank’s operation was premised upon the expectation that although these countries were a lot slower in democratic state-building, nevertheless they were ‘on the way’ to such a state. They were referred to as Early Transition Countries (ECTs) in the EBRD’s documents.Footnote18 When autocracies solidified in many of these countries, the EBRD not only had to silence its democracy mandate, but increasingly found its privatization mandate in conflict with assertive state capitalists that strengthened their positions with the rise of China and Russia in the region (Groce & Köstem, Citation2021).

Third, the 2004 and 2007 EU accession of Eastern European countries created a considerable disruption for the EBRD’s operations in the post-communist region. For one, its British and American shareholders saw that the need for the EBRD’s operations in its current form and geography had come to an end (Kilpatrick, Citation2020; interviewee #2). The US regarded these countries as now part of the EU’s economic bloc—its most important competitor—and thus found that spending US development resources there was against US taxpayers’ interests (interviewee #2). However, other shareholders, notably Germany and France, continued to hold an interest in the EBRD’s further operation and promoted it to find new purposes (Kilpatrick, Citation2020: 339). Moreover, the EBRD had a Russia-dependency problem to tackle. Disbursed loan volumes disproportionately mounted in the Russian economy. In search of new ways to use its symbolic capital, the EBRD started operations outside the post-communist region in Turkey in 2004.

After the financial crisis in 2008, the global context within which the EBRD had operated changed dramatically. The gap that opened up between the EBRD’s habitus and practice and the development finance field’s logic was so wide that the EBRD was forced into increasingly unsustainable compromises. With the coming to power of Eastern European governments that not only embraced financial nationalism (Johnson & Barnes, Citation2015), but were openly illiberal and covertly authoritarian, the EBRD faced difficult choices. Orbán, Kaczyński, Putin, Erdoğan and others questioned the legitimacy of the foreign ownership of key sectors of their economies. Their illiberal turn confronted the EBRD’s very logic of operation, built upon key presumptions that economic development and liberal democracy go hand in hand and that the latter follows from the former. In response to Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, it suspended commitments before eventually withdrawing from Russia in 2022 due to the invasion of Ukraine.Footnote19 While this move clearly diminished the EBRD’s dependence on Russian operations, it also deprived the EBRD of one of its most lucrative investment opportunities.

However, changes in the global development finance field also presented new opportunities for the EBRD to close the gap between its habitus and the field’s logic. In 2015, the UN launched a new set of development goals—the Sustainable Development Goals—which were much more in line with the EBRD’s private-sector mindset. Correspondingly, the World Bank’s new agenda, also launched in 2015—Maximizing Finance for Development—and the ‘Billions to Trillions’ agenda presented an opportunity for the EBRD to successfully use its symbolic capital. Moreover, in Europe, the Juncker Commission’s launch of the InvestEU program in 2014 to reinvigorate national development banks and the EIB, as well as the 2016 launch of the Capital Markets Union, also provided the EBRD with the opportunity to link up with its European partners. It also helped that the EU’s international development policy shifted away from poverty reduction towards more ‘acute challenges’ with the adaptation of the New European Consensus on Development in mid-2017 (Rozbicka & Szent-Ivanyi, Citation2020). In 2016, the announcement of the EU External Investment Plan called directly for the EBRD’s expertise.

Inside the EU, however, the EBRD has struggled to build good working relations with the EIB (Gómez Peña, Citation2018). Recently, the European Council (pressured by Germany and France) requested a Wise Persons Group reportFootnote20 on the future placement of the EBRD, the EIB and national development banks. The report pointed out redundancy and the possibility of transforming the EBRD into a specialized, EU-external green bank. Moreover, following Brexit and the recent volatilities of US–EU cooperation, its London headquarters—with strong embeddedness in the city’s financial circles and its overall reliance on British connections—became a drawback to its potential role in the evolving European development finance field (Hodson & Howarth, Citation2022).

In sum, the opening gap between its habitus and the development finance field’s logic in Eastern Europe—and the opening of new opportunities in global and European development finance—propelled the EBRD to escape from the hysteresis effect and close the gap between its habitus as ‘the expert of transitology’ (Shields, Citation2020: 233) and the field within which it operated.

The EBRD enters Egypt—an opportunity to resuscitate its symbolic capitals (2011–2015)

In 2011, President Mubarak’s unexpected departure opened a window of opportunity for the EBRD’s staff to strengthen the bank’s position in the development finance field and benefit from its symbolic capital, while also taking advantage of new business opportunities to increase its material capital. However, the decision to move into Egypt was not universally supported by its shareholders. The stance of the American, British and some non-EU shareholders pushing for a more significant role in the MENA region was initially opposed by Germany and Eastern European countries with fewer vested interests in the Egyptian economy (Interviewee #1). Nevertheless, by November 2011 the political support of the EU Commission and the G8-initiated Deauville Partnership paved the way for the EBRD to establish the SEMED Multi-Donor Fund with a specific goal to finance its operation in the region. The SEMED Fund was part of a broader US-backed MENA Transition Fund,Footnote21 to which most major European shareholders as donors also contributed.Footnote22 Positioning itself as a ‘multilateral initiative to support democratic and economic transition in the MENA,’ the Deauville Partnership echoed the need for the EBRD’s symbolic capital, namely reforms in governance (technical assistance), an increased role of the private sector and the impulse to move MENA states ‘towards democracy.’Footnote23 In this phase, the most important donors and agenda setters were the US and the UK, both for the Transition Fund and for the EBRD’s own SEMED Fund.

The EBRD’s first years were quantitatively and qualitatively restricted as a consequence of its inexperience with the Egyptian economy, the absence of a comprehensive EU-level strategy and the political instability and short-termism in Egypt. First, the Egyptian economy was already privatized and deregulated while also being a rentier state (Adly, Citation2020; Roccu, Citation2013). In the past, the Egyptian liberalization and deregulation reforms were driven by economic crises and subsequent pressures from the IMF and World Bank, creating an economy of coexisting privatized, military-controlled, foreign-owned and state-owned actors with abundant cronyism (El-Tarouty, Citation2003). In order to overcome its inexperience in this new context, and its relatively weak negotiation and conditionality setting power, the EBRD conducted a screening of the Egyptian private sector with the intention of identifying potential private partners and signaling those closely related to the former regime (Interviewee #3). However, driven by the EBRD’s ontology on clear-cut differences between private and state actors, the list made little sense in the hybridity of the Egyptian economy, where private businesses and state projects had been intertwined for generations. It described a reality that did not exist, thus paving the way for the EBRD’s consequent struggle to satisfy its private sector mandate.

Second, while the US and UK provided some funding and political leadership for development actors in the region, the EU’s and its member states’ response to the Arab Spring was initially uncoordinated and scarcely funded (Börzel et al., Citation2017). In the EU’s neighborhood policy, some development finance elements had already appeared, such as the 6.4 billion USD package dedicated to the EBRD and the EIB in November 2012.Footnote24 However, the realization of these new trends did not unfold until the adoption of the new neighborhood strategy, the opening up of financial resources and the crystallization of the Juncker Plan in 2014.

Third, the Egyptian governments lacked a longer-term development strategy, and their organizational instability also heavily constrained the EBRD’s opportunities. The once strong capacity of the Egyptian government in defining the contours of development declined considerably amid the 1980s extensive liberalization and privatization of its public sector, driven by both internal interest and external conditionality from institutions like the IMF and World Bank. The resulting crony (cleft) capitalist system—with powerful state-linked businessmen and a semi-autonomous military-economic sector—made coordination more difficult. Already in the 2000s, new reform projects appeared on the agenda, including EU-originated sectoral regulatory reforms (Roccu, Citation2018a; Roccu, Citation2018b) and key legislative changes for accommodating PPPs, but comprehensive planning and successful implementation fell short. Interim governments (together with President Mursi’s short-lived tenure) proceeded with some of the planning. However, their economic policy primarily targeted foreign assistanceFootnote25 for short-term currency and regime stabilization (Qatar,Footnote26 Saudi ArabiaFootnote27) or military aid (US,Footnote28 RussiaFootnote29). PPPs and the more general involvement of the private sector remained unpopular due to earlier experiences of austerity and corruption. Interim governments remained reluctant to fulfill earlier economic policy pledges to the World Bank and the IMF, which paradoxically both enabled the EBRD to fill this gap as a new and different actor in the field while restricting its choices.

Following the 2013 coup d’état and the stabilization of the Sisi regime, the EBRD started to accelerate its efforts to pressure government agencies with reform commitments in exchange for the further provision of funds. Its more important investments (such as the regulatory and technical upgrade of electric transmission systems) targeted projects that would enable and prepare larger ones to be realized later. During this period, the EBRD’s staff could more or less successfully turn its symbolic capital into assets, and thus compensated for the absence of real material capital. Real change in the EBRD’s Egyptian mission occurred only in 2015, when the Egyptian government embarked upon a comprehensive state-led development strategy under the umbrella of Vision 2030. It was also at that time that the European development finance field entered into the EU’s neighborhood policy.

The EU development finance field infiltrates the EU’s Mediterranean partnership

The European development finance field emerged in 2014 with the launch of the Juncker Commission’s investment plan to revitalize investment inside the European Union. It was this field of development actors (Mertens et al., Citation2021) that gradually infiltrated the EU’s long-term Mediterranean Partnership policy. However, in this course, the field logic underwent a few important changes. In addition to its intra-EU logic of market-based but state-led development finance (Mertens & Thiemann, Citation2018), it embraced the EU development policy’s new goals such as climate accommodation, migration mitigation and countering the EU’s geo-economic rivals (Hadfield & Lightfoot, Citation2021).

The European development finance field emerged as the EIB and national development banks (NDBs) formed a network to finance investment within the governance structure of capital markets (Mertens et al. Citation2021; Braun et al., Citation2018). The intra-EU field continued to be governed by a post-financial crisis logic: the state was now legitimated to selectively finance certain economic actors and give direction to the development of the economy. However, the state was also inclined to invite private investors to jointly provide finance either in the form of PPPs or through de-risking (taking over investment risk) in projects deemed public goods (Mertens & Thiemann, Citation2018). Clearly, the European field’s logic is an amalgam of state capitalism and Wall Street Consensus principles. It (re-)legitimates industrial policy and the public ownership of enterprises, while at the same time filtering private financial interests and the logic of financial markets into sectors that were hitherto protected from financialization (e.g. housing, public transport, healthcare, education, etc.) (Gabor, Citation2021). It blends the public and private both in the functioning of the state as well as the market. The key instruments of investment policy are development banks that work out a new balance between public and private financial interest through the design of bankable projects. Moreover, working within the framework of a restrictive EU budgetary regime, coordination of off-balance-sheet financial institutions also allows for a reworking of the European integration project with the Commission, the EIB and NDBs joining forces to set investment priorities (Guter-Sandu & Murau, Citation2022) although in a highly uneven way for differently positioned member states (Bruszt et al., Citation2022). Inside the EU, the emergence of the field, and especially of the EIB, has been followed by intensified politicization, with demands for more transparency, accountability and more democratic oversight overall (Mertens & Thiemann, Citation2019).

In the meantime, the EU’s Mediterranean Partnership—the EU’s key neighborhood policy directed toward the MENA region—also started to change. In 2008, the EU’s Neighborhood Investment Facility (NIF) was set up as a financial instrument to address ‘infrastructure projects in the transportation, energy, social and environmental sectors as well as to support private sector development (in particular SMEs).’Footnote30 In 2011, the Arab Spring heightened European interest in the MENA region. However, the EU’s response was initially inconsistent: in its immediate aftermath, between 2011 and 2015, the promotion of democracy, protections of human rights and ‘more for more’ conditionality was strengthened. Following the 2015 migration crisis and the collapse of multiple states, the EU’s focus has shifted and ‘security’ began dominating the EU’s neighborhood policy (Roccu, Citation2018a). Gradually, the traditional ‘more for more’ ‘region building’ approach was replaced by a more geopolitical one (Bicchi, Citation2014; Dandashly, Citation2018), reducing the relevance of traditional development goals of poverty reduction, humanitarian assistance and the democratization agenda (Khakee & Wolff, Citation2021).

Starting around 2014, a remarkable shift occurred in the institutional setting and the scope of the EU’s Mediterranean Partnership: development finance took a leading role. In 2014, a new EIB facility called MED5PFootnote31 was invoked under the NIF umbrella dedicated to Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco and Tunisia to support the preparation, procurement and implementation of PPP infrastructure projects.Footnote32 The MED5P was jointly financed by the EIB, the EBRD and the KfW, Germany’s own development bank.Footnote33 The same year, the already existing Facility for Euro-Mediterranean Investment and Partnership (FEMIP) was upgraded and joined by the EBRD and other banks.Footnote34 In 2016, the EU Commission published its new foreign policy strategy (Shared Vision, Common Action) with explicit reference to development funds and investment as key instruments to achieve the EU’s goals in promoting SDGs. They highlighted the need for ‘building stronger links between our trade, development and security policies in Africa,’ ‘synergies between humanitarian and development assistance,’ and ‘sustainable development and climate change.’Footnote35 In 2017, the Neighborhood Investment Platform (NIP) was established. By the early 2020s, external aid and neighborhood funds were further centralized and consolidated under the External Investment Plan (EIP). Along with the EBRD, the EIB, the Council of Europe Bank and the Nordic Investment Bank, a number of other EU-based public banks were involved, such as the AfD, the KfW, the AECID, the OeEB, SIMEST and SOFID.Footnote36 Right at the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, the EU launched the Team Europe initiative, framed as a mixture of a traditional humanitarian aid and development banking instruments with the flagship roles played by the EBRD and the EIB (Burni et al., Citation2022). Finally, in 2021, the geopolitical von der Leyen Commission announced the Global Gateway strategy to mobilize up to 300 billion EUR in public and private funds by 2027 to finance EU infrastructure projects abroad to counter China’s Belt and Road.Footnote37

At the same time, at the EU program level, new and reorganized umbrella funds and incentives came into existence, including the EU Trade Competitiveness Program and the European Fund for Sustainable Development (EFSD),Footnote38 which provided targeted funding for development banks. The EBRD also set up its own Green Economy Financing Facility (GEFF) to ‘provide loans for small-scale renewable energy investments by private companies through a group of participating banks’ in Egypt.Footnote39 Moreover, providing technical assistance as a key means of state-building became the leading task of development banks in the EU neighborhood policy as an extended legacy of state-to-state Twinning projects.Footnote40

In sum, the EU’s Mediterranean Partnership now invites development banks to focus on the private sector with a large emphasis on and funding allocated for technical assistance. These goals—echoing logics from both the WSC and state capitalism—on paper fit the EBRD’s own mandate of private sector promotion and technical assistance perfectly. Thus, they promise to ameliorate the EBRD’s position in the field, relying on its symbolic capital. The strategic neglect of traditional developmental objectives of poverty reduction and humanitarian assistance are bonus features for the EBRD, while the EU’s neglect of democratization sanctions its own disregard for democracy. To see how this worked out in practice, we turn now to the analysis of the Egyptian case.

The European development finance field’s entry into Egypt and the EBRD’s mandate management (2015–2022)

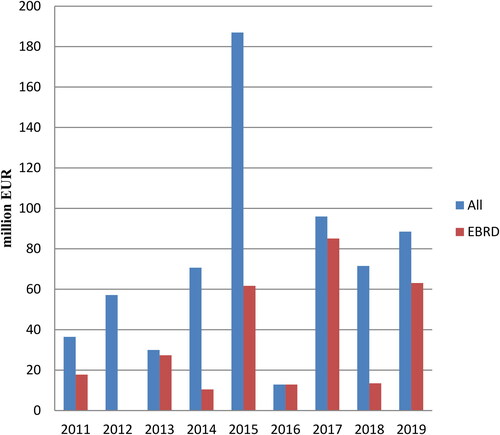

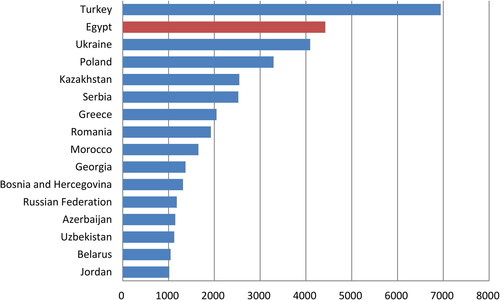

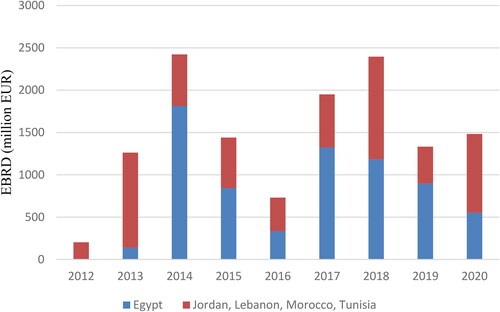

The EBRD’s position within the European development finance field grew to prominence between 2015 and 2022. Starting in 2015, EU-financed projects in Egypt had increased significantly, and the EBRD soon became the largest provider of EU funds among all EU development actors (). At the same time, the EBRD’s portfolio in Egypt had developed into the second largest share of the EBRD’s total lending by 2020 (). The EBRD operation became pronounced in all of the ‘Arab’ SEMEDFootnote41 region, with Egypt the key recipient of funds (). This excellent position within the European field could only be achieved with the adaptation of its operational logic (habitus) to the European field logic.

Figure 1. NIF-financed technical assistance, grants, and guarantees in Egypt (including regional projects) (2011–2020).

Source: Neighbourhood Investment Facility Operational Annual Reports.Footnote42

Figure 2. EBRD portfolio in 2020 (million EUR).

Source: EBRD investments 1991–2020 datasheet accessed on 6th December 2021Footnote43

Figure 3. EBRD investment in the ‘Arab’ SEMED region (2012–2020).

Source: EBRD investments 1991–2020 datasheet accessed on 6th December 2021

At the core of this exercise was its habitus mimetic adaptation to the EU’s field logic. A key to this effort was President Chakrabarti (2012–2020). During his leadership, ‘the EBRD moved center stage among the MDBs in delivering the Sustainable Development Goals,’; Chakrabarti ‘also led the drive for EBRD to become the leading MDB in the field of the green economy’; and under his leadership ‘the EBRD business model proved flexible and responsive to different geo-political and economic contexts’.Footnote44 The EBRD’s habitus adaptation to the EU field logic went hand in hand with the adjustment of its inherited symbolic capital to the new field logic

The EBRD excelled in delivering on goals both embraced by the EU’s Mediterranean Policy and the Egyptian government’s energy, trade and security policies. It must be emphasized that it is the Egyptian state, with its power and choice to conduct only bilateral negotiations that blends these two interests. In terms of energy policy, the EU’s interest in fighting climate change is in harmony with Egypt, which is the most active African state to decarbonize its energy sector. This allowed the EBRD to become the key financial partner of the energy pillar of the Egyptian government’s Nexus on Water, Food, Energy (NWFE) program, proposed by the US, EU, UK, Germany, France, the Netherlands and Denmark at the 2022 COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh.Footnote45 The EBRD’s complex engagement in the Benban solar plant and a number of other projects, such as the Green Cities and Green Value Chain programs, specifically aimed at producing a larger supply of sustainable energy in Egypt.Footnote46 In the area of trade, the October 6th dry port, the EBRD’s Egyptian flagship PPP project,Footnote47 and the planned Ramadan 10,Footnote48 meet both the Vision 2030s infrastructure targets and the EU’s trade facilitation agenda, in addition to satisfying other criteria to be included under the Green Cities facility.Footnote49 With regards to security, while the EU agreed on a 80 million EUR border control deal with Egypt just weeks before the NWFE deal,Footnote50 the EBRD-sponsored wastewater treatment PPPs and planned desalination facilities match the EU’s and Egypt’s joint interests to mitigate the water shortage consequences of the GERD dam and facilitate the solution of the related trilateral Egypt-Ethiopia-Sudan conflict.Footnote51

In addition to carefully selecting investment targets, to be successful in the EU-Egyptian development finance field the EBRD could best rely on its symbolic capital of technical assistance provision. As we saw above, EU funds from the NIF and the Mediterranean Partnership were set up in a way that they primarily provided funding for development banks to carry out state capacity building, technical assistance provision, or other forms of knowledge dissemination rather than direct and full project lending. Similarly, the SEMED Donor Fund also primarily targeted legal-institutional reforms. The EBRD took advantage of these and negotiated important technical assistance projects with the Egyptian government. Its most important achievement was to make the Egyptian PPP law work. The EBRD developed an action plan to overcome obstacles and key impediments for which it hired an international legal advisory firm with the help of a donor fund (interviewee #3), while it also sponsored the updating of the PPP Unit of the Egyptian administration to manage PPP projects.Footnote52 Moreover, the ERBD organized international conferences and roadshows in the MENA region (in 2017 in Cairo) and beyond—for high-ranking political and administrative decision makers, potential local and international advisors and other international financial institutions—to promote particular PPPs.Footnote53

Beyond public offices, the EBRD’s technical assistance also targeted public corporations. In line with the logic of the Wall Street Consensus, the EBRD also engaged in the securitization of public corporations and infrastructure loans (El Tamir securitizationFootnote54), corporate reform-linked loan restructuring schemes (NEPCO restructuringFootnote55) and sub-contracting and efficiency-enhancing knowledge diffusion. At the same time, the EBRD remained a market builder for European investorsFootnote56 and involved European advisors in technical assistance projects—e.g. Italian Railway managers hired for corporate reform through the Egyptian National Railways’ new rolling stock purchases.Footnote57

The EBRD also used its own funds for technical assistance provision. In 2015, it launched a new Infrastructure Project Preparation Facility (IPPF)Footnote58 with a pledged budget of 40 million EUR. The facility aimed at upgrading infrastructure preparation activity and providing ‘high-quality, client-oriented project preparation, policy support and institutional strengthening.’ The facility also positioned the EBRD to be ‘a leading provider of comprehensive, sustainable and inclusive infrastructure solutions.’Footnote59 As such, the EBRD delivered on the European development finance field’s logic that aims at the blending of private and public interest in the functioning of the state.

Adapting to the European development finance field’s logic of blending private and state interests in the functioning of the market revived the EBRD’s mandate-field mismatch and required active mandate management in the historically hybrid Egyptian political economy. The hysteresis effect of its strictly private sector mandate led the EBRD to disguise its funding of public Egyptian entities as if it promoted a distinctly private sector. The blended logic, however, also legitimized the funding of the sustaining actors of the authoritarian Sisi regime. To be sure, the EBRD provided direct or syndicated loans to private companies, both local and foreign-owned enterprises, the private sector loans taking up 53% of its 2022 portfolio.Footnote60 However, it also importantly increased its lending to public entities, hybrid public-private entities, the military and crony businesses that have formed the backbone of the Egyptian economy for a long time.

First, the EBRD’s lending in Egypt includes a large public infrastructure component—45% of all projects—and an extensive engagement with state-owned enterprises in public utilitiesFootnote61, e.g. the Kitchener solid wasteFootnote62 and the Cairo Metro lines.Footnote63 Second, some of the EBRD’s projects classified as ‘private’ benefit public actors either as partners in PPPs or in less institutionalized public-private schemes. The EBRD’s projects also target private actors through public intermediaries (e.g. through the National Bank of Egypt or the Banque Misr SME funds). In some cases, the EBRD justified these investments as the ‘most private-like public alternatives’ (interviewee #3). ‘Private’ beneficiary intermediaries have also included subsidiaries of Gulf State banks and funds (e.g. Kuwaiti-Egyptian AAIB, Kuwaiti NBK,Footnote64 Qatari Al-Ahli,Footnote65 and Emirates NBDFootnote66), displaying another dimension of internationalized state capitalism in Egypt. Third, even in cases of direct loan disbursement to private companies, sometimes the aim is to support other interrelated projects where the public sector participates. This is the case with the new legal framework for electricity that preceded the Benban solar plant’s constructionFootnote67 or the chain of investment in private oilFootnote68 and gas production,Footnote69 their refineries,Footnote70 and transportation and storageFootnote71 enterprises. Fourth, the EBRD in some cases classified its own involvement as a private subcontractor in Egyptian PPPs. This was the case when Aqualia—the EBRD’s partly-owned subsidiary—acted in an EBRD-financed wastewater management project (New Cairo Wastewater),Footnote72 in the acquisition of Infinity Energy in the Benban solar park,Footnote73 and in the case of Adwia Pharma, 99.6% of which was co-acquired by the EBRD, a British private equity fund and the UK’s Commonwealth Development Corporation.Footnote74

Fifth, despite distancing itself from Mubarak-linked businesses, and its emphasis on competitive and transparent bidding processes (interviewee #3), the EBRD has increasingly cooperated with actors in the military economy. The military—having substantial economic power and political embeddedness through Sisi’s past as Minister of Defense and Military Production, and as the Commander-in-Chief of the Egyptian Armed Forces—was able to reinforce its position following the return of autocracy. Key roles were distributed to military personnel in the Vision 2030 plan as subcontractors, planners, constructors, land allocators and supervisors (Roll, Citation2019; Khalil & Dill, Citation2018) in some cases replacing the former Mubarak-era business elite. In this context, the EBRD both advocated privatization and engaged with them through securitization and as indirect partners.

Finally, the EBRD’s loan provision to and cooperation with politically-linked local businesses, such as the construction company OrascomFootnote75 and El Sewedy ElectricFootnote76, not only highlights the contradiction inherent in the initial screening and blacklisting exercise, but also underlines the difficulties in avoiding such collaborations in state-led projects or where key sectors are dominated by local elites, often with competing interests and dynamically changing relations with state authorities. Here the EBRD cooperates with powerful actors with regime-sustaining economic and political influence (Smierciak, Citation2021). Naguib Sawaris—the Mubarak-era owner of the Orascom—is both a liberal critic of Sisi’s state capitalism and politically active advocate of the military coup, as well as a trustee of the Central Bank’sFootnote77 Long Live Egypt FundFootnote78 The owner of Elsewedy Electric, Mohammed Zaki El-Sewedy—an industrial strongman of Mubarak-era (Roll Citation2019)—was not only appointed by Sisi’s government as President of the Federation of Egyptian Industries without the approval of the Federation’s members,Footnote79 but also became the head of Sisi’s Support Egypt political coalitionFootnote80 as a vocal promoter of Sisi’s development policies.Footnote81 While the interim military government tried to exclude this clique from political leadership amid fears of public backlash and limited opportunities for military businesses to take over rents, they nonetheless returned as valuable private partners and PPP subcontractors of the EBRD within Sisi’s Vision 2030 (Smierciak, Citation2021).

The proposed pivotal green hydrogen facility illustrates powerfully the cumulation of these hybrid solutions: under the climate agendas of both Egypt’s Vision 2030 and the EU, the EBRD brokers and finances the joint project of a Norwegian private company with Sawaris’s Orascom, his brother’s Fertiglobe, the Sovereign Fund of Egypt and the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company. This deal is highly dependent on previously facilitated energy, logistics and transport infrastructure projectsFootnote82 and the EBRD’s involvement at the legal and strategic levels.Footnote83

With the adaptation to the EU field logic, the EBRD had to significantly rework the use of its once defining symbolic capital, its democracy mandate. This is paradoxically also the EBRD’s symbolic capital that has been most leveraged within the context of the promises of democratic transition in the MENA region in 2011 and particularly in Egypt. To see the EBRD’s struggle with this mandate, we reviewed its Egypt country reports from 2017Footnote84 and 2022.Footnote85 According to its statute, the EBRD is required to assess the democratic transition process in each country where it operates. In Egypt, this proceeded in three ways. First, the EBRD started to reinvent and rephrase ‘democratic transition’ as synonymous with employment creation, sustainability and broader (trickle-down) economic growth, sometimes complemented by the European development finance field’s equation of good governance and a lack of corruption with ‘human rights.’ Concepts of ‘sustainability’ and ‘green transition’ also seemed to address the earlier criticism of its market-oriented approach, connecting market promotion and commercialization under the broader (SDGs-compatible) goals of human dignity and climate change mitigation. Second, the EBRD reports’ assessments of democratic transition consistently applied a technocratic legal-technical framing wherein progress is defined in terms of procedural changes or opportunities, highlighting the constitutional right for election participation (2017) and the assumed strengthened constitutional role of the Parliament under Sisi (2022). Third, and connectedly, whenever the EBRD employs criticism, it always does so from the position of an unbiased and descriptive outsider, abstaining from any kind of substantive evaluation. This comes in stark contrast to its authoritative metric scores for PPP regulation or green transition. The concerns of NGOs and IGOs about human rights and the rule of law are always presented as opinions. In the 2022 report, there is a relatively more balanced presentation, while sections from the 2017 report always end with an unreflective display of official government refutations to a given claim. In other cases, the report merely cites descriptive and uncontextualized information (e.g. non-voting penalties in elections).

In its political mandate management, the EBRD benefits tremendously both from the low level of politicization of the functioning of European development banks (both national and the EIB) outside the EU, as well as from its ‘invisibility’ (Shields, Citation2020) to major NGOs, watchdogs, press, researchers and the scrutiny of politicians. Aside from occasional press coverageFootnote86 and NGO reports,Footnote87 the EBRD faces remarkably little criticism for its mandate violation.Footnote88 We argue that the EBRD’s success in avoiding harsher criticism lies in its successful adaptation to the logic of the European development finance field, where its lending practices and technical assistance—and its new ‘green bank’ status—ensures its ameliorated position and long-term survival.

Conclusions

Our study analyzes an RDB’s operation within the new modalities of the global development finance field in the Global South. The unique case of the EBRD allowed us to evaluate how the European development finance field’s logic (which incorporates elements from both WSC and state capitalism) impacted the EBRD’s ability to take advantage of its symbolic capital— including technical assistance, its democratization mandate, and its private-sector mindset—in Egypt, where it arrived ready to use these assets to ameliorate its position in the development finance community. Our field-theoretical analysis revealed that the EBRD faced no obstacles in delivering technical assistance to the Egyptian legal infrastructure and public companies, in developing securitization schemes and designing PPP projects, i.e. transforming the social infrastructure of the Egyptian political economy towards the de-risking logic of the WSC while also driving state capitalism.

However, working in Sisi’s Egypt, the EBRD faced important barriers to deliver on its private sector mandate (in terms of directly financing private enterprise), and especially its political mandate that requires it to operate only in countries that are committed to democracy. It is the EBRD’s habitus mimetic adaptation to the European development finance field which legitimizes its operations and the management of its symbolic capital (democratic and market mandates) in Egypt. However, the EBRD is not only a passive adapter to the European field, it is instrumental in transforming the European field and blending the logic of the WSC with state capitalism in Egypt.

Our findings are in line with the observed proliferation of spatialized industrial policies around large infrastructure projects in the Global South at the axis of WSC and state capitalist drive (Schindler et al., Citation2022). Nevertheless, there are multiple interacting state capitalist policies and interests in Egypt, including China’s bid to build the Central Business District of the New Administrative CapitalFootnote89 Russia’s involvement in a planned Suez industrial zoneFootnote90 and the multiple state-led Gulf capital in EBRD-linked projects, as well as the activity of European NDBs and bilateral economic diplomacies (#interviewee 3).

The increasing globalization of EU neighborhood policies and the marketization of its aid agenda through development banks mean that our observations could have broader implications. As the EU’s development policy embraces the fight against climate change as a both symbolically and materially appealing strategy to engage with the Global South, our findings critically underline that the lack of democratic, deliberative and redistributive principles in development finance are to be addressed at the level of the EU field because the adverse impacts of WSC-driven market forces and the state capitalist logic on these principles cannot be resolved at the level of individual development banks.

Acknowledgments

We thank Daniel Mertens, Matthias Thiemann, Lama Tawakkol, Stuart Shields, David Karas, David Howarth, Michael Merlingen, Susan Park, Rachel Epstein, Eric Brown, and Robert Lieli who provided comments that greatly enriched this article. All errors are ours.

Disclosure statement

No conflict of interest has been reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Dóra Piroska

Dr. Dóra Piroska is an Assistant Professor at the IR Department of CEU, Vienna. Her research focuses on the IPE of banking and development finance. She has a particular interest in the Eastern Central European region. She has published on the Banking Union, macroprudential regulation, the Regulatory Sandbox, the EIB and the EBRD. She investigated financial nationalism, financial power and democracy.

Bálint Schlett

Bálint Schlett holds an M.Sc. degree in Development Economics from SOAS University of London; he is a graduate of the Széchenyi István College for Advanced Studies (Budapest) and a current Economic Geography M.Sc. student at the University of Groningen. His interests include international relations, development economics, economic geography and the politics of the Middle East and North Africa.

Notes

1 ‘From Billions to Trillions: Transforming Development Finance Post-2015 Financing for Development: Multilateral Development Finance’ was written by the African Development Bank (AfDB), the Asian Development Bank (ADB), the EBRD, the European Investment Bank (EIB), the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the World Bank (WB).

2 The EBRD also commenced its operation in Lebanon and the West Bank and Gaza in 2018, while Algeria, Libya, UAE and Iraq have recently become non-recipient members.

3 https://www.ebrd.com/standard-poor-supranational-special-edition.html (p. 90), accessed on 6th December 2021.

4 Bankwatch is the only watchdog organization that explicitly monitors the EBRD.

5 https://www.ebrd.com/shareholders-and-board-of-governors.html, accessed on 25th November 2021

6 https://www.imf.org/external/np/g20/pdf/2018/082918.pdf (p. 3), accessed on 23rd November 2021.

7 https://www.ebrd.com/who-we-are/our-donors.html accessed on 19th August 2022.

8 Article 1 of the Agreement Establishing the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development.

9 Paragraph 3 of Article 11 of Agreement establishing the EBRD, https://www.ebrd.com/news/publications/institutional-documents/basic-documents-of-the-ebrd.html, accessed on 27th November 2021.

10 https://www.ebrd.com/who-we-are/our-donors.html accessed on 22nd August 2022.

11 https://www.ebrd.com/who-we-are/history-of-the-ebrd.html# accessed on 22nd August 2022.

12 https://eur-lex.europa.eu/EN/legal-content/glossary/european-bank-for-reconstruction-and-development.html# accessed on 9th August 2022.

13 https://www.ebrd.com/our-values/transition.html accessed on 29th August.

14 https://www.ebrd.com/our-values/transition.html accessed on 29th August.

15 https://www.ebrd.com/documents/comms-and-bis/pdf-political-aspects-of-the-mandate-of-the-ebrd.pdf accessed on 24th August 2022.

16 https://www.ebrd.com/documents/comms-and-bis/pdf-political-aspects-of-the-mandate-of-the-ebrd.pdf access on 24th August 2022.

17 https://bankwatch.org/publication/ebrd-transition-role-in-the-spotlight-again, accessed on 25th November 2021.

18 https://www.ebrd.com/documents/comms-and-bis/pdf-transition-and-transition-impact.pdf, (p. 10), accessed on 7th November 2021.

19 https://www.ebrd.com/where-we-are/russia/overview.html accessed on 24th of November 2022.

20 https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/40967/efad-report_final.pdf, accessed on 25th November 2021.

21 https://www.menatransitionfund.org/donors-and-partners accessed on 28th August 2022.

22 https://www.ebrd.com/deauville-partnership.html, accessed on 6th December 2021.

23 https://www.ebrd.com/deauville-partnership.html accessed on 28th August 2022.

24 https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-20322407 accessed on 29th August.

25 https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/162759/WP_EGYPT.pdf accessed on 29th August.

26 https://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/09/world/middleeast/qatar-doubles-aid-to-egypt.html accessed on 29th August.

27 https://english.ahram.org.eg/NewsContent/3/12/12683/Business/Economy/Saudi-aid-to-include–billion-Egypt-central-bank-d.aspx accessed on 29th August.

28 https://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/feb/04/egypt-protests-us-military-aid accessed on 29th August.

29 http://america.aljazeera.com/articles/2014/2/13/russia-putin-sissiegyptmilitaryaidcoup.html accessed on 29th August.

30 https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/285a3c64-5152-4cb4-aff6-ea5a307324ba, accessed on 23rd November 2021.

31 MED5P: Public-Private Partnership Project Preparation in the Southern and Eastern Mediterranean

32 https://www.eib.org/en/projects/regions/med/med5p/index.htm, accessed on 22nd December 2021.

33 https://ufmsecretariat.org/, accessed on 22nd December 2021.

34 https://www.eib.org/en/publications/femip-2014-annual-report, accessed on 22nd December 2021.

35 https://eeas.europa.eu/archives/docs/top_stories/pdf/eugs_review_web.pdf, accessed on 6th December 2021.

36 https://ecdpm.org/wp-content/uploads/BN-55-Blending-loans-and-grants-for-development.pdf, accessed on 23rd November 2021.

37 https://www.politico.eu/article/eu-launches-global-gateway-to-counter-chinas-belt-and-road/, accessed on 6th December 2021.

38 https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegDaa/etudes/BRIE/2019/637893/EPRS_BRI (2019)637893_EN.pdf, accessed on 22nd December 2021.

39 https://ebrdgeff.com/egypt/ accessed on 22nd December 2021.

40 https://neighbourhood-enlargement.ec.europa.eu/funding-and-technical-assistance/twinning_en accessed on 24th November 2022

41 SEMED: Southern and Eastern Mediterranean, regional classification of the EBRD.

42 The annual cumulative investment of NIF targeting Egypt. Regional programs are calculated according to the average share of Egyptian NIF investments in the region (50%). Multiannual investments are divided evenly between the indicated years. All: All NIF investments for Egypt (including EBRD, EIB, KfW, AFD, AECID as grantees). EBRD: NIF investments for Egyptian projects where EBRD is the only or one of the grantees. https://neighbourhood-enlargement.ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-investment-platform_enaccessed on 24th November 2022

43 http://www.ebrd.com/cs/Satellite?c=Content&cid=1395250404279&d=&pagename=EBRD%2FContent%2FDownloadDocument accessed on 6th December 2020. Note: the datasheet is no longer accessible on the website.

44 https://www.ebrd.com/who-we-are/ebrd-president-sir-suma-chakrabarti.html accessed on 13th September 2022.

45 https://www.ebrd.com/news/2022/egypts-nwfe-energy-pillar-gathers-international-support.html accessed on 24th November 2022.

46 https://www.ebrd.com/news/2022/how-the-ebrd-became-egypts-leading-partner-for-renewable-energy-.html. Accessed on 24th November 2022.

47 https://www.ebrd.com/work-with-us/projects/psd/51830.html accessed on 29th August 2022.

48 https://www.ebrd.com/news/2021/ebrd-supports-new-dry-port-development-in-egypt.html accessed on 29th August 2022.

49 https://www.ebrd.com/news/2021/ebrd-finances-6th-of-october-dry-port-in-egypt-under-ebrd-green-cities-.html accessed on 24th October 2022.

50 https://www.reuters.com/world/eu-funds-border-control-deal-egypt-with-migration-via-libya-rise-2022-10-30/#:∼:text = CAIRO%2C%20Oct%2030%20%28Reuters%29%20-%20The%20European%20Union,when%20Egyptian%20migration%20to%20Europe%20has%20been%20rising. Accessed on 24th November 2022.

51 https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/29957/W18012.pdf?sequence=4&isAllowed=y accessed on 29th August 2022.

52 https://www.ebrd.com/work-with-us/procurement/p-pn-67753-egypt-ministry-of-finance-ppp-unit-support.html accessed on 5th September 2022.

53 https://www.ebrd.com/news/2017/ebrd-and-egypt-join-forces-in-dry-port-ppp-development.html, accessed on 3rd December 2021.