Abstract

Recent IPE scholarship locates the key dynamics of financial globalization in two areas: public money flows between the US and Asia, or private banking flows between the US and Europe. This dichotomy presents the globalization of private finance as firmly anchored within transatlantic, neoliberal financial norms. We argue that this creates a blind spot regarding the growing role of East Asian finance within the global financial system. Combining CPE insights on institutional characteristics of Asian financial systems with a macro-financial analysis of the global financial system, this paper analyzes the global implications of the geographic shift towards East Asia. First, we demonstrate the growing importance of East Asia for global macro-financial flows, actors and markets that goes beyond the rise of China. Second, we explore how the institutional arrangements that underpin Asian financial systems differ significantly from transatlantic finance. By investigating the growing importance of global investors in Asian markets and Asian investors in global markets, we explore how the shift towards East Asia introduces a growing role of developmental characteristics within global finance. This calls for a reconsideration of conventional analyses of the global financial system which often assume its role as a force of neoliberal globalization.

Introduction

After Lehman Brothers’ collapse on 15 September 2008, the bankrupt global powerhouse was broken up and its remaining operations sold to financial institutions who had better weathered the global financial storm. Winning against competing offers from Barclays and Standard Chartered, Japan’s biggest investment bank Nomura acquired Lehman’s Asia-Pacific and European operations, solidifying its foothold in European markets only a year after expanding its US presence through the acquisition of Instinet. Nomura acquired Lehman’s operations only weeks after state-owned Korea Development Bank had walked away from acquisition talks that could have rescued Lehman, while in March 2008 China’s largest investment bank CITIC had launched an (ultimately unsuccessful) bid to acquire the failing US investment bank Bear Stearns. These early advances of Asian financial players on the global scene foreshadow a larger shift which has—despite its far-reaching implications for the post-crisis politics of global finance—only received limited attention in International Political Economy (IPE) research: The growing importance of East Asia within the global financial system.

Since the 2007-09 North Atlantic financial crisis (NAFC), IPE scholarship has located the key dynamics of financial globalization in two distinct areas. The first focuses on money flows associated with macroeconomic imbalances, such as the relationship between excess savings and FX reserve accumulation in Asian economies on the one hand, and ballooning US debt and deficit on the other hand (Kalinowski, Citation2013). This dynamic is sustained by the dominance of the US dollar, which bestows a well-known ‘exorbitant privilege’ on the US to pursue domestic policy without facing external constraints (Eichengreen, Citation2010). In contrast, peripheral states are limited in their ability to use their currency in international trade and finance. In this interpretation, the relative role of major currencies has implications for the balance of power between states, drawing analytical attention to the relationship between major powers in today’s globalized world. Thus, the primary focus of analysis is China’s rise and potential contestation of US (dollar) hegemony (Cohen, Citation2018; Helleiner & Kirschner, Citation2014; McNally, Citation2012). This, however, comes at the expense of analyzing the broader significance of East Asia, its more varied integration and potential challenge of the global financial system.

The second approach seeks to gain a more intimate understanding of the role of private finance in the international system: from understanding the NAFC’ origins in market-based banking (Hardie et al., Citation2013); investigating the post-crisis rise of non-bank investors in global markets (Bonizzi & Kaltenbrunner, Citation2019; Gabor, Citation2021); to exploring the politics behind the infrastructural entanglements between state actors and market instruments (Braun, Citation2020; Gabor, Citation2016). Influenced by the experience of the NAFC, these interpretations tend to emphasize the centrality of transatlantic financial relations between the United States and Europe (Beck, Citation2022; Hardie & Thompson, Citation2021). European regulatory interventions and business practices were key to the rise and resilience of market-based finance (Gabor, Citation2016; Thiemann, Citation2014) and highly leveraged transatlantic banking relationships dominated by European banks were central during the NAFC, serving as an important conduit for the global intermediation of US dollars and the growth of shadow banking (Tooze, Citation2018). By focusing on the activities of private financial actors in intermediating financial flows between different national jurisdictions, this approach offers unique insights into the mechanics and politics of the global financial system. In this interpretation, ‘macro-financial’ rather than macroeconomic imbalances are at the heart of financial globalization.

In somewhat stylized terms, then, we are presented with a picture in which IPE scholarship has focused either on public money flows between the US and Asia (China), or on private banking flows between the US and Europe. As we argue, this implicit division of labor creates a false dichotomy by ignoring the growing importance of private international finance in East Asian economies and their integration into the global financial system. This generates important shortcomings: by considering the globalization of private finance first and foremost as an Anglo-American or European affair, the governing logics and dynamics of private international finance (both pre- and post-crisis) are tacitly assumed to be informed by transatlantic financial relations. As a result, IPE scholarship has largely failed to question whether there is anything distinctive about the interaction of private international finance and East Asian economies, and how such interactions could impact the norms, rules and procedures that govern the global financial system.

Despite offering unique insights into the mechanics of the global financial system, we argue that the macro-financial research program suffers from a blind spot regarding East Asia’s rising importance in global finance. In recent years, Asian investors have greatly expanded their operations into global markets and increasingly drive global investment flows. At the same time, East Asian capital markets have grown at extraordinary rates, outsizing and outperforming their European peers as they attract evermore global capital inflows (see section 4). However, the growing integration of East Asia into global finance should not be likened to a seamless continuation of neoliberal financial liberalization. Instead of converging towards a neoliberal logic that conflates ‘efficient’ outcomes with maximizing (private) profit (see section 2), the institutional arrangements that underpin financial transactions and relationships in East Asia retain what we refer to as ‘developmental characteristics’. Here, finance takes on an important role in facilitating national developmental objectives, thereby blurring the state-market boundary (see section 3). East Asia’s rise within global finance thus calls for a reconsideration of conventional IPE analyses of the global financial system which often assume its role as a force of neoliberal globalization that reinforces the (infra)structural power of finance. Instead we see new public-private institutional arrangements emerging that challenge the neoliberal norms of market organization, strengthening public authority within global finance and through private financial actors. While these are ideal-types and there is of course significant variation within/between East Asian (developmental) and European (neoliberal) finance, our findings nevertheless indicate that we need to pay closer attention to this shift.

To make sense of these changing institutional arrangements that underpin private international finance, we argue that the macro-financial IPE framework for analyzing the global financial system needs to integrate insights from Comparative Political Economy (CPE) scholarship on commonalities and differences between the institutional configurations of national financial systems (Deeg & Jackson, Citation2007; Vitols, Citation2001; Zysman, Citation1983). While both IPE and CPE scholarship have substantially advanced our understanding of the politics of global finance (Deeg & O’Sullivan, Citation2009), these two strands of literature have seldom been integrated into one framework to analyse the dynamics of the global financial system (but see Kalinowski, Citation2013). Although a substantial body of CPE scholarship sheds light on the development of East Asian financial systems from a national, comparative, or regional perspective (see section 3), East Asia’s role within the global financial system has been neglected in these debates.

By combining CPE’s focus on institutional characteristics with a macro-financial IPE analysis of the global financial system, our paper provides a novel approach to exploring the geographic shift of international finance towards East Asia. We analyze the global financial system as constituted by financial flows that are facilitated by globally active financial actors and take place between financial markets which are part of distinct national models of capitalism. By breaking down the global financial system into these observable, constitutive parts our framework is attentive to the role of institutional specifics within the global system. In an initial step, we demonstrate that East Asia matters for global finance by presenting empirical financial data that points towards East Asia’s growing importance for global financial flows, actors and markets (and the subsequent declining centrality of European finance).

But more than documenting a mere quantitative shift in investment flows, our framework also allows us to explore why East Asia matters as the institutional characteristics that drive the global integration of East Asian financial systems differ (in part) markedly from European finance, with broader implications for the dynamics and politics of the global financial system. We do this by analyzing the global integration of China, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan, since these four Asian economies are the most important drivers of this shift (see section 4). While we cannot conduct in-depth explorations of each case, this paper highlights potential implications for the global financial system and develops a research agenda to further study this important issue.

Our analysis draws on financial data, policy documents and expert interviews. First, we compiled an extensive dataset with descriptive financial statistics gathered from national authorities (e.g. central banks), international financial institutions (e.g. BIS), financial industry associations (e.g. WFE) and financial data providers (e.g. Bloomberg Terminal). Second, we analyzed policy documents, regulatory frameworks and research reports. Third, this was complemented through 48 expert interviews with financial market participants in Beijing, Chicago, Frankfurt, Hong Kong, London, New York, Shanghai, Seoul, Singapore, Taipei, Tokyo and Zurich between June 2017 and December 2022. The paper is structured as follows. After the introduction, the second section discusses the emergence of the macro-financial framework and its analysis of neoliberal transatlantic finance as shaping the pre-crisis global financial system. Contributing to this research paradigm, the third section develops our conceptual framework that combines macro-finance (IPE) and institutional characteristics (CPE), thereby enabling us to grasp both quantitative and qualitative changes in the global financial system. Section four examines the empirical shift from Europe to East Asia in global finance by focusing on changing financial flows, actors, and markets. Section five then illustrate how Asia’s rise has implications for the politics of the global financial system by (1) analyzing how global investors must accept the developmental logics that inform East Asian markets and (2) investigating the growing influence of East Asian investors in global markets that is partially directed and managed through developmental state interventions. Section six concludes and outlines a research agenda.

(Neo)liberalism and the global financial system: a transatlantic affair?

How global money flows are structured and managed has long been a key concern of IPE. Following the NAFC, IPE research has begun to dissect the macro-financial dynamics that connect private financial actors and the credit instruments that dominate the global financial system. Whereas early accounts focused on macroeconomic imbalances caused by a ‘savings glut’ (Obstfeld & Rogoff, Citation2009), the macro-financial approach that has since emerged as an important interpretation of the crisis points to the endogenous role of private finance in expanding credit through complex business practices and transnational operations (Shin, Citation2012).

Proponents of the macro-financial approach have located the NAFC’s geographic center in transatlantic banking relationships that linked European banks to US capital and money markets (Dutta et al., Citation2020; Hardie & Thompson, Citation2021; Shin, Citation2012; Tooze, Citation2018). Historically, private cross-border flows have been dominated by a cluster of American and European banks: following the advent of the Eurodollar markets in London and the re-emergence of global finance after the collapse of Bretton Woods, transatlantic financial flows started to dominate the global financial system (Helleiner, Citation1996). Importantly, while initially comprising of a more diverse set of institutional arrangements (Hall & Soskice, Citation2001; Zysman, Citation1983), the national financial systems of American and European capitalisms gradually transformed according to a neoliberal script provided mainly by US-based financial interests, which some authors have referred to as the ‘Americanization’ of European finance (Beck, Citation2022; Gabor, Citation2020; Konings, Citation2008). While we do not dismiss existing divergencies between European capitalisms, we can arguably observe the adoption of ‘neoliberal characteristics’ across large parts of European financial systems (Prasad, Citation2006).

As the macro-financial perspective highlights, this neoliberal institutional logic contributed to the creation of a highly fragile, crisis-prone global financial system. Banks extended their reach into global markets by turning towards market-based banking (Hardie et al., Citation2013), notably via the repackaging of illiquid loans into tradable securities (Thiemann, Citation2014) and the funding of such assets in wholesale repo markets (Gabor, Citation2016), which was supported by permissive regulation in the US and Europe. These shadow banking practices have been identified as key drivers of financial instability and systemic risk during the crisis (Shin, Citation2012). Despite the post-crisis implementation of macro-prudential policies to address these systemic instabilities, the NAFC has largely been regarded as a ‘status quo’ crisis that has not fundamentally changed or challenged the contemporary order (Helleiner, Citation2014).

The regulatory reinvention of shadow banking as ‘resilient market-based finance’Footnote1 has subsequently been hardwired in what Gabor (Citation2021) calls the ‘Wall Street Consensus’ (WSC). The modus operandum of the WSC is to reorganize state practices in a fashion that removes private sector risks from specific market segments, either by guaranteeing systemic liabilities or by enabling the creation of new investment objects (such as ‘infrastructure-as-an-asset-class’) as for private finance (Gabor, Citation2020, pp. 51–52). The ‘de-risking’ role of state is particularly visible in enabling private capital flows to the Global South, where states reorient policies to create safety nets for global investors. State initiatives range from encouraging capital market liberalization to directly underwriting private profits by protecting investors against political and market risks, for instance by guaranteeing a minimum level of demand for services and by ensuring consistent access to liquid markets for investors. Thereby, the WSC extends the operative logic of liquidity support beyond the usual confines of money markets and applies it to the capital accumulation strategies of financial capitalism more broadly.

The expansive role of the state in sustaining private investments has been integral to the resilience of global finance post-crisis. The macro-financial perspective confirms the persistence of a decidedly neoliberal script in global governance: as states pursue socio-economic development by enabling profit creation for private financial actors, the resulting entanglement with finance acquire an ‘incestuous’ quality (Tooze, Citation2018, p. 309). Financial arrangements are underpinned by a neoliberal narrative built on ‘the superiority of individualized, market-based competition over other modes of [economic] organization’ (Mudge, Citation2008, pp. 706–707). The legitimacy of this underlying narrative depends on neoliberalism’s ability to propose a fictional state-market separation that depoliticizes state support and instead confers responsibility for ‘efficient’ social outcomes to the collective agency of private financial actors (Konings, Citation2016). To defend this purported key organizing principle of the neoliberal arrangement—the reliance on private profit incentives—amidst proliferating social, financial, geopolitical, and ecological crises, technocratic governance has become increasingly reliant on ensuring markets’ overall robustness and liquidity. Transcending moments of crisis, liquidity support through ‘de-risking’ now increasingly shapes the daily operation of financial markets (Musthaq, Citation2021).

But how universal is this script? As we explore in this paper, the importance of the transatlantic space within the global financial system has declined while East Asia has gained in importance. Whereas American and European financial practices were crucial to understanding the pre-crisis politics of global finance in which the (infra)structural power of finance is facilitated by the state, changes in the global financial system should prompt IPE to incorporate into its analysis a better understanding of East Asian financial systems, their institutional characteristics, and how they relate to neoliberal patterns of transatlantic financial globalization. What is distinctive about the growing importance of private international finance in East Asia? How can we analyze public-private financial arrangements that prioritize developmental objectives, rather than private profit creation? What implications has the role of such developmental characteristics within a global financial system hitherto dominated by neoliberal institutional logics? Indeed, as private East Asian investors increasingly internationalize, can developmentalism be sustained throughout the process of global expansion?

A conceptual framework for East Asia’s rise in the global financial system

To better understand the implications of East Asia’s rise within the global financial system, we argue that the IPE literature on global finance must engage more extensively with the CPE literature on East Asian capitalisms. Our conceptual framework combines insights from these two strands of literature. We first utilize a macro-financial perspective that analyses the mechanics of the global financial system as an interlocking network of financial flows, mediated by financial actors between national financial markets. Through this we investigate changes within the global financial system and observe the increasing global importance of East Asia (that East Asia matters). We then complement this framework with insights from CPE literature on East Asian financial systems, highlighting variation between public-private institutional configurations and resulting financial patterns. We demonstrate that many domestic institutional arrangements which underpin financial transactions in East Asia (developmental) differ significantly from those arrangements that underpin transatlantic financial transactions (neoliberal). Consequently, changes in the national composition of the global financial system have systemic implications (why East Asia matters). More than a mere description of changing global investment patterns, our framework helps to illustrate the potential impact of Asia’s growing global importance.

A dynamic global system: financial flows, actors, and markets

Macro-finance analyzes interactions between disparate financial actors operating across multiple markets and institutional settings, rather than focusing on macroeconomic imbalances in trade flows. Here we draw on Morgan and Goyer (Citation2012), who shortly after the NAFC posed a seemingly strange question: ‘Is there a global financial system?’. They argue that rather than assuming that financial globalization created an amorphous, intangible ‘global’ financial system, scholars should move ‘beyond the rhetoric of globalization’ and acknowledge how global finance is constituted by financial flows that are facilitated by globally active financial actors and that take place between financial markets which are rooted within distinct national models of capitalism (Morgan & Goyer, Citation2012, pp. 120–121).

First, eliminating capital controls after the demise of Bretton Woods facilitated an unprecedented growth of financial flows between countries, including cross-border banking operations, foreign direct and portfolio investment. Global capital flows follow push and pull factors, as expectations about future cash flows play a functional role in investment decisions (Fratzscher, Citation2011). Among push factors, low interest rates have accelerated the global search for yield, whereas domestic, country-specific pull factors account for growing capital inflows into regions like Emerging Asia. Further, as global financial flows are denominated in key currencies, typically the US dollar, investors that accumulate asset-liability positions in foreign currency face a structural demand for foreign currency funding that subjects them to the pace and rhythm of global liquidity conditions (Bonizzi & Kaltenbrunner, Citation2019). While such flows were historically dominated and shaped by private financial actors from America and Europe, more recent investment flows and associated funding patterns indicate the growing importance of East Asia in global markets.

Second, these financial flows are mediated by financial actors, thereby linking investors from different jurisdictions in a complex global network of interlocking balance sheets. As Morgan and Goyer (Citation2012, pp. 130–131) emphasize, this process of global financial intermediation is a task of high organizational and technological complexity, requiring financial institutions to establish local presences and operational capabilities in multiple countries and across market segments. While global banks continue to occupy the central nodes of financial networks, cross-border links of non-bank financial institutions gained momentum in recent years (BIS., Citation2020). Non-banks have pushed into global bond markets and accumulated large holdings of foreign currency assets, often funded through short-term money market liabilities. By analyzing the new linkages between these previously disparate financial actors, we demonstrate the increasingly global reach of East Asian investors.

Third, the activities of financial actors interlink different financial markets. Locationally, financial activities are concentrated within international financial centers (IFCs) such as New York, London or Tokyo that form the centerpieces of national financial systems. But more than just booking centers for transactions, these IFCs are crucial parts of national financial markets that form the ultimate investment destinations for the flows intermediated by financial institutions. Financial assets such as sovereign bonds, futures contracts or company stocks are ultimately located within national jurisdictions, denominated in specific currencies and subject to the laws/regulations that determine the organization of cross-border investments. By highlighting the growing importance of Asian IFCs/markets as investment destinations, our analysis equally points towards the growing importance of East Asian markets for global finance.

Rather than simply describing the global financial system, this conceptual framework enables us to understand changes within global finance and observe the increasing importance of East Asia within the global financial system since the NAFC (that Asia matters). Further, instead of focusing on a stylized ‘global’ system, our framework also shifts the analytical focus towards the composition of this system and the interactions between its constitutive elements.

Bringing institutions into macro-finance: CPE and the developmental characteristics of East Asian financial system

By zooming in on the ‘matrix’ of interlocking balance sheets that underpins global finance, the macro-financial perspective has arguably sharpened our understanding of the financial processes and instruments that underlie modern markets. Yet by methodologically rendering all institutions as fundamentally alike, it tends to abstract from socio-institutional specificity and assumes a neoliberal logic as modus operandum. To avoid such pitfalls, we draw attention to the different institutional logics that underpin financial transactions.

In the CPE literature, financial systems are considered an important institutional sphere within national capitalisms (Hall & Soskice, Citation2001; Vitols, Citation2001), which consist of financial markets and actors that are informed by different institutional logics/characteristics. These distinct logics emerge as national institutional configurations create distinct patterns of constraints and incentives that shape and channel actors’ behaviors (Deeg & Jackson, Citation2007, p. 152). Importantly, within our framework we then need to pay attention to the fact that financial flows are mediated between institutionally diverse national markets and by financial actors that are equally embedded within/informed by different institutional structures.

As established in the previous section, despite some variation/differences European and US finance are underpinned by a broadly neoliberal institutional logic (Hardie et al., Citation2013). Financial actors are primarily motivated by profit considerations, while financial markets are designed to enable the free flow of capital across borders (Deeg & O’Sullivan, Citation2009). While there are instances of developmentalism as evidenced by the growth of national development banks (NDBs; Mertens & Thiemann, Citation2018), these arrangements only represent a fraction of transatlantic finance. The state’s priority remains enabling private profit creation instead of other socio-economic outcomes by making these markets more resilient or de-risking financial investments, cementing the power of private finance capital (Gabor, Citation2021).

By contrast, many aspects of East Asian financial systems exhibit ‘developmental characteristics’. While we acknowledge variation between individual Asian economies and the organization of their financial systems (Walter & Zhang, Citation2012; Witt & Redding, Citation2014), we explicitly do not subscribe to a more specific conceptualization of political-economic interaction as these include some while excluding other countries. Authoritarian capitalism, for instance, fits China but not other East Asian economies, while the developmental state concept is more applicable to, say, Korea than China. Instead, we focus on this meta-level by arguing that—similar to European and US finance sharing neoliberal characteristics—one commonality of East Asian capitalisms is that their financial systems share similar institutional configurations that facilitate developmental objectives (Rethel & Thurbon, Citation2020; Walter & Zhang, Citation2012).

We thereby follow Thurbon’s (Citation2016, p. 18) definition that ‘developmentalism is essentially a set of ideas about the necessity and desirability of strategically governing the […] economy for nation-building purposes’. At its core, developmentalism thereby differs from neoliberalism with respect to the dominant principles that underlie market organization (profit creation vs national development) and the actor constellations that consequently dominate/shape these markets (private finance vs larger role of public actors). It is not the existence/growth of financial markets, per se, but rather their institutional characteristics that create different politics and lead to diverse socio-economic outcomes that differentiate these financial systems.

Like neoliberal variegation within the transatlantic constellation, we posit that this developmental orientation is a shared characteristic of financial systems across different conceptualizations of Asian capitalisms: whether this is state(-led/-permeated) capitalism (Kurlantzick, Citation2016; Nölke et al., Citation2020), authoritarian capitalism (Gruin, Citation2019), Sino-capitalism (McNally, Citation2012), the entrepreneurial (Rethel & Sinclair, Citation2014) or developmental state (Wade, Citation2004; Woo-Cummings, Citation1999). This assumption is also supported by comparative literature on Asian capitalisms (Storz et al., Citation2013, p. 219; Witt & Redding, Citation2014). As Eaton and Katada (Citation2022, p. 2) noted, scholars have thereby ‘drawn attention to transnational lineages of developmentalist thought in East Asia’, despite differences in how developmentalism manifests itself within national capitalisms.

Rather than (primarily) oriented towards private profit creation, we argue that national developmental considerations influence financial market structures and investor behavior across East Asian countries. Instead of a leading sector in its own right, finance is seen as input to other economic sectors.Footnote2 Importantly, these developmental characteristics have persisted despite the increasing financialization of East Asian economies, as public-private institutional arrangements evolved that continuously facilitate developmentalism in East Asian financial systems (Rethel & Sinclair, Citation2014; Rethel & Thurbon, Citation2020; Underhill & Zhang, Citation2005). Despite disruptions through the Asian Financial Crisis (AFC) (Wade & Veneroso, Citation1998), we see the persistence of such institutional specificities within Asian financial systems with different degrees and forms of public-private configurations underpinning developmentalism across countries.

In China’s authoritarian state capitalism the state’s role within the financial system is most prominent. Petry (Citation2020) illustrates how state control was retained amidst the financialization of China’s authoritarian state capitalism and how finance was directed towards national development objectives, with research on China’s banking system (Gruin, Citation2019) and currency internationalization (McNally & Gruin, Citation2017) painting a similar picture. Thurbon (Citation2016, p. 2) demonstrates the presence of a ‘developmental mindset’ in South Korea’s political elites, which facilitates ‘national techno-industrial catch-up and export competitiveness via strategic interventions by the state’. Despite structural adjustment measures and increasing financialization after the AFC, state direction of the financial system remains persistent (Kalinowski, Citation2015). Taiwan also gradually integrated into global finance while maintaining control over its domestic financial system through a high degree of financial activism, albeit in a less coordinated fashion than in Korea (Thurbon, Citation2020). In Korea and Taiwan, public ownership of financial institutions is less pronounced than in China (albeit not absent). Here, public authorities more indirectly influence private financial actors and engage in more ‘covert’Footnote3 market intervention (Gallagher, Citation2015; Thurbon, Citation2016). In Japan, public authorities only have limited capabilities of directly steering the activities of private financial actors. While partially liberalized, Japan’s financial system retains many developmental elements (Katada, Citation2020; Kushida & Shimizu, Citation2013). Gotoh (Citation2019) for instance demonstrates how Japanese finance resisted pressures to conform with neoliberal norms, while Kamikawa (Citation2013) shows how banks have not followed European banks’ path towards market-based banking. Existing cross-country studies show that this persistence of developmentalism is largely consistent across Asian economies (Kalinowski, Citation2015; Rethel & Sinclair, Citation2014; Witt & Redding, Citation2014).

Despite important variations, we hence posit that important institutional commonalities exist that shape East Asian finance. As Wade (Citation2018, p. 537) noted, rather than noting the ‘death’ of developmentalism in Asia we should rather investigate how it evolved in response to changing parameters. An increasing financialization of East Asian economies should therefore not be equated with neoliberal financial liberalization. Based on this conceptual framework we argue that the changing composition and subsequently different interactions of financial flows, actors and markets have implications for the global financial system.Footnote4 In contrast to the neoliberal institutional logic prevalent in transatlantic finance, we argue that the developmental logic that informs East Asian financial systems leads to different patterns of cross-border integration ().

Table 1. Institutional logics and patterns of cross-border financial integration.

Instead of liberalized capital accounts, Asian markets are opened more selectively to pre-empt volatile capital flows and/or maintain control over domestic markets. Further, the internationalization of Asian investment is significantly informed by national development objectives that supplement private profit considerations. By complementing a macro-financial perspective with CPE insights, our conceptual framework thereby enables us to illustrate that East Asia increasingly matters within global finance and points to how this changing constellation—with diverging public-private institutional arrangements between European, Asian and US finance—has implications for the politics of the global financial system (i.e. why East Asia matters).

From Europe to Asia: a global shift in financial flows, actors and markets

Over the past years, Asian financial centers, markets, and investors have emerged as central nodes in the global financial system as evermore financial flows are directed towards or originate from Asia. While the US maintains its central position within global finance, we can observe a shift from Europe towards Asia.

In the first instance, publicly-directed investment flows from East Asia into global markets have expanded dramatically since the NAFC as state-directed/controlled financial actors are important features of those economies. East Asian NDBs account for a 41.4% share of global NDB assets, compared to 8.4% for Western NDBs.Footnote5 Similarly, China’s largest SWF, China Investment Corporation (CIC), managed $1.2trn by end-2020, making it the second largest source of state-directed capital, globally.Footnote6 Asia’s growing importance thereby coincides with more state-led investment within the global financial system.

Yet the relative shift within global finance away from East Asia and towards Europe is also visible within private financial investments. The figures are particularly remarkable within global banking: whereas European banks accounted for 62.7% of assets held by the largest 50 banks globally in 2008, their share had decreased to 35.2% by 2020. In contrast, Asian banks increased their share from 17.0% to 43.8% over the same period ().

Table 2. Top-50 largest banks globally (% of assets).

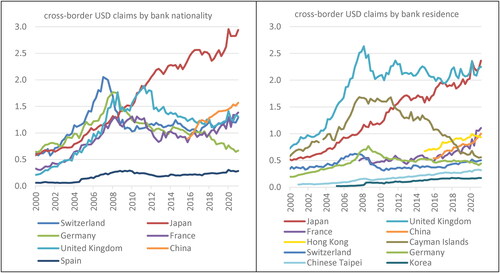

This shift is not only observable in the increasing size of banks, but also in their international activities. As McCauley et al. (Citation2017) demonstrate, European banks considerably scaled back foreign operations as part of their post-crisis deleveraging. While global dollar assets of European banks have shrunk by 42% between 2007 and 2017, those of Japanese banks increased by 88%, reaching $2.7trn in 2017 (; also, Aldasoro et al., Citation2019). Other large Asian depository institutions have also dramatically expanded their footprint in international markets. For instance, Norinchukin, a Japanese cooperative financial institution, has become a large investor in the US corporate loan obligation (CLO) market. By 2020, the bank held around $72bn of US CLO debt, equivalent to 10% of the market.Footnote7

Figure 1. Non-US banks’ US dollar-denominated claims (USD trillion).

Source: BIS locational banking statistics.

Following in the footsteps of Japanese institutions, other Asian economies such as China have increased their participation in the global dollar system, especially via bond markets (BIS., Citation2020), with estimated Chinese portfolio holdings of US securities ranging between $1.5-2.1trn.Footnote8 When measuring cross-border banking claims by bank nationality, Japanese and Chinese institutions are the two largest sources of cross-border USD investment. Asian USD banking remains sizable when measuring cross-border claims by bank residence, even though residence criteria arguably skew the results in favor of IFCs such as the City of London or Cayman Islands and underestimate the overseas activities of Asian economies.Footnote9 But even here, Japan has overtaken the UK as largest jurisdiction, while China (no.4) and Hong Kong (no.5) only marginally trail France (no.3). Other European countries’ shares have also fallen, while the shares of Korea and Taiwan have doubled ().

Driven by the post-crisis deleveraging of European banks’ dollar assets (McCauley et al., Citation2017), cross-border banking lost in relative significance, while non-bank investors like insurers, pension funds and index funds have become more important facilitators of global financial flows in recent years. This corresponds to what Hyun Song Shin, BIS’ Head of Research, has termed a shift away from the ‘first phase’ of global liquidity centered around cross-border banking flows (2003–2008), and towards a ‘second phase’ focused on global bond markets (2010 onwards). This ‘portfolio glut’ (Gabor, Citation2021) is dominated by buy-side investors that have expanded their foreign portfolios in a global search for yield (Bonizzi & Kaltenbrunner, Citation2019).

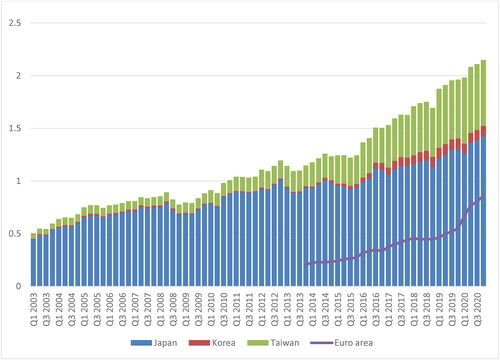

East Asian investors play a significant role in driving these cross-border portfolio flows. Life insurers from Japan and Taiwan (and to a lesser degree Korea) have almost doubled their foreign assets to nearly $1.5trn since 2015, accounting now for an overall share of about 20% of global life insurance premium volumes (IMF, Citation2019). When adding the investments of pension funds, holdings of international securities are estimated to be as much as $2.2trn (). By contrast, foreign (non-EU) bond holdings of Euro area insurers and pension funds remained modest at roughly $550bn before the pandemic. The largest increase in dollar assets here is visible in investment funds, who had doubled their US assets in recent years to about $1trn (BIS., Citation2020, pp. 24–26). Further, trading during Asian time zones has increased across global markets, indicating a larger role of Asian investors globally.Footnote10

Figure 2. Investments in Foreign Securities by Insurance Companies and Pension Funds (USD trillion).

Source: Central bank websites.

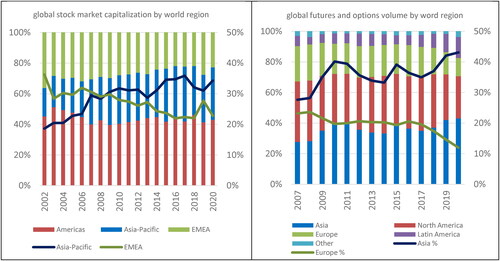

But not only Asian investors, financial markets in Asia have also grown enormously post-crisis, increasingly outsizing and outperforming European markets as well as becoming more important global investment destinations. Whereas Asian stock markets only accounted for 18.6% of global market capitalization, their share had almost doubled (34.3%) by 2020. And while the share of US markets remained relatively stable, Europe’s share decreased from 36.3% to 22.8% (, lhs). A similar picture emerges for derivative markets. Between 2007 and 2020, Asia’s share of global futures/options trading volume increased from 27.6% to 43.1% while Europe’s share declined from 23.1% to 12.0% (, rhs). And with respect to bond markets, Asia accounted for 29.3% of global bond markets by 2020, in contrast to 14.8% for the euro area (ECB, Citation2021; ICMA, Citation2021).

Further, while European IFCs were major locations of global financial market activity in the 2000s, apart from London they declined in relative importance as Asian financial centers became crucial for global financial activities. While according to the Global Financial Centre Index (GFCI) nine European IFCs ranked among the top-20 in 2007, by 2020 only five were left, whereas the number of Asian IFCs rose from four to eight ().

Table 3. The rise of Asian financial centers.

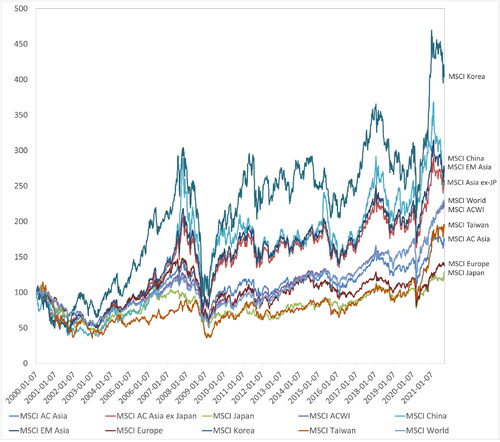

Asia’s rise is thereby also reflected in global investment benchmarks. Its share in MSCI’s Emerging Market Index increased from 52.8% (1994) to 63.23% (2007) and now 80.16% (2020), as a result of which a majority of emerging market investments are nowadays steered towards Asia. Further, as an analysis of Asian and European stock index performances illustrates, Asian equity markets have not only outgrown but also outperformed their European peers since the NAFC (). When excluding Japan—which experienced sluggish growth since the early 1990s—from the analysis, European markets trail even further behind as Asia also outperforms global benchmarks.

Figure 4. Relative performance of Asian and European stock markets.

Source: MSCI index data via Bloomberg.

Overall, the data presented in this section illustrates that Asia increasingly matters for the global financial system while Europe is declining in relevance. Importantly, four countries thereby account for the majority of Asia’s growing footprint within the global financial system: China (incl. Hong Kong), Japan, Korea and Taiwan. Together, these markets account for 73.1% of Asian stock market capitalization (WFE., Citation2021), 50.3% of Asian futures trading (FIA, Citation2021a, FIA., Citation2021b) and 88.1% of Asian bond markets (ICMA, Citation2021). They also account for 24.0%, 21.7% and 25.8% of global stock, futures, and bond markets, respectively.Footnote11 And while other Asian markets like India or Russia have also grown in recent years, East Asian financial actors have ventured into global markets to a much larger degree.

But what are the implications of this shift beyond mere quantitative changes of macro-financial flows? Switching from a macro-level analysis of financial flows, the following section systematically analyses how the growing global importance of these four Asian financial systems is significantly informed by developmental logics. This, we argue, potentially challenge the neoliberal rules, norms and procedures that have hitherto governed the global financial system.

Why Asia matters: developmental logics and the global financial system

Analyzing the interplay of developmental and neoliberal characteristics of Asian and ‘global’ finance, the following two subsections explore the implications of this shift in global finance—why East Asia matters. First, we analyze how global investors accept the developmental rules of East Asian markets when reallocating investments. Second, we analyze the persistence of developmentalism in the internationalization of East Asian finance. These processes illustrate both instances of convergence with but more prominently also challenges to the neoliberal politics of the global financial system.

Global investors in Asian markets: adapting to developmental rules?

Over the last decade, Asian markets outperformed European markets, both in terms of short-term stock market valuations and medium/long-term macro-economic growth forecasts, making them attractive investment destinations. Consequently, we can observe an influx of foreign capital into Asian markets. For actors that strive to maximize their investment returns, the principle of free capital movement is typically crucial to achieve ‘efficient’ outcomes (via profit creation). Following a neoliberal logic, global norms of market access stipulate very few restrictions on capital flows and investor access, with international investors’ ability to access markets and withdraw funds functioning as a disciplinary mechanism.

However, such unfettered access can lead to foreign investors’ dominating local markets while often also introducing considerable financial volatility (Bonizzi & Kaltenbrunner, Citation2019), both of which can severely disrupt national development objectives—a lesson many Asian countries learned during the AFC.Footnote12 While complete isolation from global investors is hardly possible nor desirable, we can observe commonalities in how Asian capital markets’ international integration is designed to resist pressures from profit-oriented global investors. This financial opening is a more selective, strategic process designed to pre-empt volatile capital flows and/or maintain national control over domestic markets and listed companies by restricting and monitoring the access, activities and ownership of foreign investors. As one interviewee noted, ‘[Asian] markets are quasi-public organisations [with] less focus on commercial objectives, […] you can see this in India, China, Korea, even Japan, where there is a completely different mindset’.Footnote13 While European finance increasingly converged towards neoliberalism since the 1980s, as our subsequent analysis highlights a persistence of developmental characteristics that can be observed in East Asian markets despite an increasing influx of global capital (see Appendix, Table SA).

This is most pronounced in China which has emerged as the largest destination of investment flows into Asian markets. By 2020, US investor holdings of Chinese assets have increased to $1.2trn,Footnote14 with $275bn flowing into Chinese bond and stock markets in 2020-2021 alone. However, Chinese financial markets function fundamentally different from European/US markets. The state maintains ‘control over the commanding heights of the economy’ (McNally, Citation2012, p. 754), regulating and pragmatically utilising financial markets to achieve development objectives as they ‘are intricately linked with state institutions and play an active role in facilitating national development goals’ (Petry, Citation2021b: 607). Consequently, despite an influx of global investors, we can observe a persistence of the developmental characteristics of China’s financial markets.Footnote15 Importantly, this is not only a China story. Thurbon (Citation2020, p. 331) for instance discussed how—motivated by a developmental mindset—Taiwanese authorities engaged in ‘monitoring of capital flows [and] clamping down on speculative activities to ensure that finance met productive ends’, while Korean markets have also been actively shielded from volatile global investment flows (Gallagher, Citation2015; Thurbon, Citation2016).Footnote16 And while closest to the neoliberal ideal type, Gotoh (Citation2019) demonstrates how the institutional structures of Japan’s financial system prevented a convergence with neoliberal global norms.

While evermore global capital flows into these markets, the inbound investment regimes of East Asian financial systems are mostly informed by developmental logics (). By analyzing the distinctive features of their financial opening processes—restrictions and monitoring of foreign investor access, activities, and ownership—the following comparative analysis illustrates commonalities between China, Korea, Taiwan and (to a lesser extent) Japan, in how their financial openings constrain global investors and facilitates national development objectives.

This is, for instance, exemplified through the regulation of foreign investor access. While in Japan no foreign investor registration is necessary, in China, Korea and Taiwan investor access is subject to regulatory approval. In these markets, foreigners can only invest after obtaining regulatory approval as qualified foreign investors (RQFII/QFII, IRC, FINI/FIDI schemes) or through dedicated investment channels (Stock/Bond Connect, KRX-Eurex/CME Link or Eurex/Taifex Link). These access channels should be understood as ways to manage capital flows; as one interviewee noted, ‘with Stock Connect [Chinese authorities] have this beautiful sort of capital control mechanism […] they can always turn off the tap…’.Footnote17 As a result, foreign ownership of exchanges—which enforce these rules, monitor markets and manage controlled access—is restricted in all East Asian markets: in Japan foreigners are only allowed to own up to 49%, in Korea and Taiwan this is capped at 25%, whereas exchanges are fully state-owned in China. In Asia, ‘government regulations protect exchanges’Footnote18, which is quite different from how neoliberal markets operate. Foreign investor access is restricted to prevent disruptions of local markets and enable a degree of control over capital market dynamics and outcomes.Footnote19

A similar pattern exists for the monitoring of foreign investor trading and ownership. Utilizing their existing registration systems, in China and Korea the exchanges/authorities monitor foreign ownership levels and trading activities (e.g. FIMS in Korea, SAFE/CFMMC in China). Foreign stock ownership and trading activity are even partially restricted by regulatory agencies. These monitoring systems are also hard-wired into capital market structures.Footnote20 In China, Korea and Taiwan, for instance, investor-ID systems exist, and brokers have to use segregated investor accounts to ease regulatory oversight, while Japan has a hybrid system that allows both omnibus and segregated accounts. In contrast, neoliberal markets usually operate omnibus systems which reduce trading costs (profit/neoliberal logic) at the expense of oversight (control/developmental logic). As one interviewee noted, in these Asian markets ‘you have to be registered—they really want to monitor who’s doing what and where’.Footnote21

This system influences foreign trading and ownership patterns. Whereas from a neoliberal perspective, an open, active market for corporate control is an important feature to facilitate shareholder value orientation (profit creation), in Asian capital markets strategic companies are often protected from foreign control in order to create national champions or facilitate industrial strategy by restricting foreign ownership in strategically important companies. Foreign investors hold between 40.8%-66% of major European stock markets, whereas foreign ownership only accounts for 5% in China, ∼20% in Korean markets as well as ∼30% in Japan and Taiwan. Foreign ownership for any listed Chinese company is even capped at 30% of its (free float) shares and restrictions also exist in Korea and Taiwan. As a result, while global capital is increasingly allocated in Asian markets, this process is structured in a way that restricts the influence of foreign investors while maintaining national policy autonomy.Footnote22 This access regime also extends to capital and currency controls. While the Japanese Yen has a flourishing global FX market, offshore currency markets do not exist for the other countries and their onshore trading is quite restricted by national authorities.Footnote23 Further, all countries but Japan have enacted various forms of capital controls in recent years, albeit Taiwan and Korea less regularly than China.

Overall, we can observe a persistence of developmental logics in the financial opening of East Asian capital markets. Whereas China clearly exhibits the most restrictive approach to foreign investors, Korean and Taiwanese authorities also actively manage inbound financial flows and foreign investor activities. Only Japan exhibits clear neoliberal characteristics. And while Japan’s financial opening is closest to a neoliberal model, it is noteworthy, that according to index provider MSCI, ‘Japan is the only Developed Market where improvements in the foreign investment regime are encouraged’.Footnote24 Here, Japan scores the same rating as Korea, Taiwan and China (while ‘no issues’ are reported for European markets). So, even in Japan—which has for a long time been firmly integrated into global financial circuits—neoliberal logics have not fully replaced existing institutional configurations (see Gotoh, Citation2019; Kamikawa, Citation2013; Kushida & Shimizu, Citation2013).Footnote25 While the aggregate volume of global financial flows towards Asia has increased, foreign investors are not dominating or taking over Asian markets as investor access/power is constrained by the developmental logics that inform this opening process. Rather than taking a larger share of the pie, global investors seem to grow with Asian markets as the pie becomes bigger.

These developments likely have implications for the global financial system. East Asia is becoming an increasingly important constitutive element of global finance. Given the institutional differences within financial opening processes of European and East Asian finance, a growing portion of the contemporary global financial system functions different than just 15 years ago. Especially in China, but also Korea and Taiwan, global investors must adapt to the developmental characteristics of these markets and play by their rules when allocating investments. Thereby, global investors accept—and by investing their money, even legitimize—these different market practices.

Asian investors in global markets: developmentalism going global?

Along with Asian markets, Asian financial actors have also become more important globally. Yet whereas Asian economies are highly successful in setting the ‘rules of the game’ for foreign investors domestically, a more nuanced picture emerges with respect to the internationalization of Asian finance and its challenge of the liberal global financial system. Focusing on the growing global footprint of East Asian investment, this section analyses the growing role of developmentalism within global finance across three levels: (1) through the growth of publicly-directed investment flows that deviate from neoliberal norms; (2) through the active role of public authorities in facilitating/managing outward private investment; and (3) by analyzing moments of accommodation/contestation of East Asian developmentalism. Together, we show how East Asia introduces new dynamics into a previously mostly neoliberal global system (see Appendix, Table SB).

Our starting point is the variety of Asian public investment flows into the global financial system. Such investment is informed by national development goals and significant levels of state intervention, marking a variation from neoliberal norms (notwithstanding variation in scope and characteristics between countries).

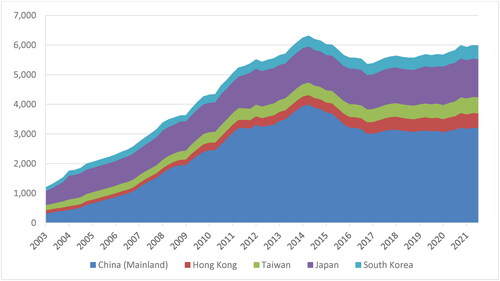

The most obvious case of such investments is the accumulation of FX reserves which Asian economies have been actively utilizing to manage their exposure to global finance since the AFC. By 2021, Asia accounted for 68.8% of global FX reserve holdings, dwarfing those of developed countries (20.8%), with our four cases accounting for 52.4% of global holdings (). Yet liquidity insurance is not the only motive behind FX reserve accumulation. Efforts to manage the domestic economy, such as to shield export-oriented economies from appreciating exchange rates, have often been a driving force (cf. McCauley, Citation2019). The most prominent case here is China, which sold about $1trn in FX reserves in 2015 to stabilize domestic markets,Footnote26 albeit Taiwan also has a history of ‘recycling’ FX reserves for national development purposes (Thurbon, Citation2016, pp. 59–60).

Figure 5. FX reserves by East Asian countries (in billion USD; 2003-2021).

Source: Bloomberg Terminal.

National developmental objectives also inform the activities of state-directed/controlled market actors from East Asia, like SWFs and NDBs. Created to diversify accumulated FX reserves, SWFs often have a dual role of seeking return while also serving national policy objectives by investing into strategic industries (Liu and Dixon, Citation2021).Footnote27 With regards to NDBs, the spotlight is typically on China’s development banks, yet Korea Development Bank and Development Bank of Japan are also among the largest NBDs globally and actively further national development objectives.Footnote28 Additionally, sizeable state-owned banks and non-banks in Taiwan, Korea and China have been used to facilitate national development objectives—from stabilizing domestic stock marketsFootnote29 to financing the internationalization of national companies.Footnote30 Motivated by its public mission to stabilize the national pension system, Japan’s publicly-owned Government Pension Investment Fund (GPIF)—the world’s largest asset owner—has obtained a leadership role in the global push towards sustainable investing,Footnote31 a move that was recently followed by Korea’s National Pension Service, the third largest pension fund globally.Footnote32 This forms a stark contrast to the lackluster approach of dominant Western asset managers such as BlackRock with profit-driven business/investment allocation models (Baines & Hager, Citation2022).

Overall, the state retains an active role in facilitating and encouraging both public and private investments which follow not just profit motives but also strategic, developmental and sometimes geopolitical objectives. The geostrategic dimension is particularly visible in the surge of overseas infrastructure investments. While China’s BRI has received considerable attention, in Southeast Asia, for example, Japan ($259bn) remains a larger provider of infrastructure finance than China ($157bn). Japan has thereby partially reverted to its post-war strategy of nurturing close government-business partnerships in facilitating overseas infrastructure financing (Katada, Citation2020, pp. 175–182). Similarly, Korea’s government facilitates private infrastructure investment under the ‘New Southern Policy’ framework to support the international expansion of Korean companies,Footnote33 while Taiwan included infrastructure projects/financing into its ‘New Southbound Strategy’.Footnote34 Thereby, Asian governments often push private financial actors to co-finance investments and actively support the internationalization of domestic companies, following them into other markets.Footnote35 Rather than primarily profit-driven, the international activities of Asian financial actors are thus (partially/initially) informed by developmental objectives.

A similar geostrategic and developmental logic can be observed in the acquisition of financial infrastructures (Petry, Citation2022). Japan Stock Exchange’s acquisition of the Yangon Stock Exchange was partially motivated by the desire to gain political allies and to fend off competition, such as from Chinese and Korean exchanges, which have invested in and operated marketplaces in Bangladesh, Pakistan, Kazakhstan and Germany (China) or Uzbekistan, Laos and Cambodia (Korea). As these countries compete for their standing as regional economic powers, according to an exchange representative ‘the Japanese government encouraged that relationship’ while ‘the Korean government [also] strongly encourages KRX to expand their business in Southeast Asia, even though it’s not profitable’.Footnote36 This is fundamentally different from the profit-driven approach followed by Western stock exchanges (Petry, Citation2021a). Collectively, these more developmental investments utilize finance to strengthen domestic industries and geopolitical standing and stand in stark contrast with the ‘infrastructures-as-an-asset-class’ approach increasingly central to neoliberal finance (Gabor, Citation2021).

While these investments offer a good indication of developmental logics at play in the internationalization of East Asian capital, national objectives do not extend to all foreign investments. A large part of foreign financial investments is profit-oriented and conducted by private financial actors without geostrategic considerations. Especially following the NAFC, East Asian private sector purchases of foreign assets have expanded rapidly, which now outsize official reserves by 200%.Footnote37 Yet even here East Asian states retain an important entrepreneurial role in managing the globalization of such investments.

Notably, the internationalization of private East Asian investors is driven not just by cross-border banking but also through sizeable investments by non-bank financial institutions (e.g. pension funds, life insurers). Non-banks are unable to access global (dollar) funding markets through the same range of instruments as banks and lack a direct central bank backstop. As a result, these investors tend to depend more heavily on short-term funding like the FX swap market to obtain dollar liquidity for international investments (BIS., Citation2020). Due to the currency/liquidity risks inherent in these operations, fluctuating exchange rates or refinancing conditions can induce considerable losses. To avoid such situations, Asian central banks intervene to provide sufficient liquidity and cushion the volatility of currency movements, allowing investors to adjust their portfolios when necessary. Central bank interventions are thus crucial in sustaining investment strategies (Musthaq, Citation2021).

The growing support for East Asian private finance through (indirect) central bank liquidity support seems to suggest that these economies are adopting a neoliberal model of private sector de-risking. Yet important differences remain. As Western central banks have become more interventionist in the wake of the crisis, their primary objective of macroprudential interventions remains to backstop, rather than to channel, investment flows.Footnote38 By contrast, Asian central banks assumed not just enhanced lender of last resort functions for globalizing Asian capital but have proactively supported private overseas investment strategies by cushioning exchange rate movements.Footnote39 FX interventions thus arguably blur the boundaries between macroeconomic and macroprudential management, even though they are typically framed in terms of macroprudential stability objectives (on Korea, see Gallagher, Citation2015). One example of this dynamic can be witnessed during 2022 as East Asian countries saw a considerable depreciation of their currencies against the dollar. As Chinese, Korean, and Japanese authorities intervened to stem acute currency sell-offs, investors faced considerable difficulty in ascertaining whether interventions were targeted at exchange rate volatility or at ensuring a certain exchange rate level.Footnote40

The tensions between de-risking and developmentalism inherent to such interventions point to broader questions of accommodation or contestation as East Asian finance internationalizes. Notably, while persistent exchange rate interventions and other means of support for East Asian investment have drawn accusations of currency manipulation, Western states have focused on China and generally shied away from officially labelling US allies like Korea, Taiwan and Japan as such.Footnote41

This is partially because the growing size and heft of East Asian finance has conferred a systemic importance onto the region: As East Asia has emerged as the largest buyer of US sovereign and corporate debt, vulnerabilities within East Asian finance could destabilize the global financial system. In recognition of this systemic interconnectedness, the US Federal Reserve has become a more active international lender of last resort within East Asia, as evidenced by the uptake of swap lines: while the ECB accessed almost 80% of swap line lending during the NAFC, during the market turmoil caused by Covid-19 in early 2020, the Bank of Japan accounted for the largest share of dollar swap line uptake, about 47%, with Korea accounting for another 2.5% (Pape, Citation2022). The growing importance of East Asia in dollar-centric private international markets was also a key motivation behind the creation of the Fed’s FIMA repo facility in early 2020.Footnote42 Designed to avoid the politicization of lending that followed swap lines in the past, the repo facility appears intended for those countries with large FX reserve holdings, growing dollar exposures and strained political ties to the US—most notably, China. According to former Fed trader Joseph Wang, ‘the new FIMA Repo Facility is largely a China Repo Facility’.Footnote43

Overall, this signifies how the growing centrality of Asian investors in USD markets forced a reconfiguration of US macro-financial policy and an extension of central bank backstop arrangements despite the developmental challenge of East Asian finance to key norms of neoliberal finance. Accommodation despite contestation could be interpreted as a weakness of US state capacity: amidst the rise of Asian finance and its systemic relevance for the global dollar system, the Fed has little choice but to extend liquidity support to East Asian actors in times of crisis (cf. Hardie & Thompson, Citation2021).

Yet below the systemic level, we are also witnessing an increasing politicization of specific East Asian investment practices—as visible in debates about currency manipulation, the recent ban of Korean equity derivative trading by US securities regulators,Footnote44 or recent moves towards investor screening/bans targeted at Chinese companies.Footnote45 In contesting East Asian investment strategies and practices, Western states are thus themselves moving towards greater interference and control of purportedly ‘free’ market processes. Here, geopolitical competition might facilitate the diffusion of developmental norms on a broader scale or, alternatively, we could feasibly interpret recent interventions—often framed in terms of national security interests—as a response to the developmental challenge, designed to safeguard or securitize private finance and investment opportunities against geopolitical challengers.

While investors typically acquiesce to the rules of global finance when investing in foreign (currency-denominated) markets/assets, with respect to the globalization of East Asian finance a more nuanced picture emerges where some Asian investments partially challenge the logics underpinning the global financial system while others sustain its modus operandum. While the growth of market-based global operations of Asian financial actors has pushed East Asian states into a stronger de-risking stance, they also retain an important entrepreneurial role in managing the globalization of Asian investments. More than passively facilitating investment, these public authorities play an active role in directing (strategic investments) and safeguarding (FX operations) investment flows while contesting (currency intervention) and reconfiguring (swap lines/repo facility) global macro-financial arrangements. These practices challenge the liberal global financial system as evidenced by the increasing politization of FX interventions, growing rhetoric about currency manipulations, or the accommodation of developmental Asian investment through Western central banks. Importantly, while current academic and policy debates mostly focus on China, we have illustrated that these should rather be understood as characteristic of the growing contestation of neoliberal finance by East Asian financial internationalization.

Conclusion: exploring the new normal of global finance

Whereas Europe was crucial to understanding the pre-crisis politics of global finance, today East Asian financial flows, actors, and markets are gradually replacing them as central nodes in the global financial system. Combining a macro-financial IPE perspective that investigates changing financial flows, actors, and markets within the global financial system with insights from CPE literature on the developmental characteristics of Asian financial systems, this paper demonstrated the quantitative shift towards Asia (that Asia matters) and points towards the implications of this shift for the politics of global finance (why Asia matters). We illustrate this by analyzing the activities of Asian investors in global markets and how global investors engage with Asian markets.

Thereby, we identify commonalities and differences, both between Asian countries as well as between outward investment and internal markets: First, as global investors increasingly venture into East Asian financial markets, their investment activities are often monitored, regulated, and restricted, and they must largely adopt to non-liberal rules of market organization. Second, while the internationalization of Asian investments is informed by both developmental and de-risking logics, East Asian public authorities nevertheless play an active role in managing investment flows for developmental purposes, introducing new public-private interactions into a formerly passively regulated private global financial system. Third, we identify variation within East Asia: Japanese markets/investors are more in tune with neoliberal ideas whereas the financial openings of Korea, Taiwan and especially China are much more aligned with developmental characteristics. We can thereby also see a shift within Asia’s constellation as part of the global system. While before the NAFC, Japan—which has the closest institutional similarity with European capitalisms (Witt & Redding, Citation2014)—largely represented Asia within the global financial system, the financial rise of more developmentally-oriented East Asian economies, especially China, makes it more difficult to subsume Asia within a neoliberal paradigm. At the same time, our analysis also points towards a growing importance of East Asia beyond a narrow focus on China’s contestation of US hegemony as a potential challenge of the liberal international order.

Overall, we observe that instead of converging with prevailing global norms, Asian finance remains substantially informed by developmental logics despite its increasing financialization and globalization. This makes the composition of the global financial system more heterogeneous, marking a tectonic shift that challenges the neoliberal transatlantic consensus that defined the pre-crisis global financial system. Our study points towards an important blind spot in IPE analyses of global finance. Both IPE research that focuses on public money flows driven by reserve-accumulating Asian economies as well as macro-financial analyses of private international finance need to expand their analytical focus to take into consideration the newly emerging Asian public-private institutional arrangements that entangle public authorities with the investment strategies of financial actors and challenge neoliberal norms of market organization. Going forward, a key question thereby will be to distinguish structural from cyclical factors: how sustained—amidst geopolitical, social, and environmental crises—is the rise of Asia? While the patterns identified in this paper, points towards a strategic and thus potentially structural integration of East Asia into the global financial system, this question remains open to future scholarship.

Indeed, given the scope of this project, this paper can only be exploratory in nature. More research and a better understanding of Asia’s growing role within the global financial system is needed. On the one hand, this calls for more in-depth case studies of how individual Asian economies are integrating into global finance as well as how their investments impact neoliberal financial systems. On the other hand, a closer integration of IPE and CPE approaches that provides a more accurate understanding of the conditions under which national institutional logics translate into global market practices is warranted. While this paper focused on East Asia, future research should include other Asian financial systems into their analysis: India is among the world’s fastest growing and increasingly internationalizing financial systems with likely developmental characteristics; growing Islamic Finance sectors in Malaysia or Dubai equally challenge liberal norms of market organization; and Russia’s financial markets—especially in the wake of Western sanctions after the Ukraine invasion and growing Sino-Russian financial collaboration—also warrant closer scrutiny. Furthermore, we see moments of contestation as powerful Western financial actors often consider developmentalism as violation of the neoliberal rulebook of how global finance should function. Index provider MSCI, for instance, threatened to downgrade China, India, and Korea for not properly opening their markets. Similarly, the US Treasury recently placed several Asian countries on its currency manipulation watch list, and the ongoing US-China trade war equally stems from a clash of neoliberal and developmental logics. How do Asian actors mediate pressures to adopt neoliberal rules? Are these pressures effective or are we instead witnessing the emergence of an Asian financial sphere of influence that is largely informed by developmental logics?

Finally, Asia’s growing importance in global finance raises important conceptual considerations for IPE’s study of global finance. As Yeung (Citation2009, p. 202) emphasized with respect to changing global growth patterns ‘the rise of East Asia provides fertile research ground for us to “theorize back” at dominant IPE theories in the “North”’. This also applies to the global financial system. Are contemporary theories of the (infra)structural power of finance sufficient to analyze non-Western financial systems? Can East Asian developmentalism help us to better understand the recent emergence of more non-liberal practices (e.g. investment screening/bans) in the West within the context of growing geopolitical tensions? Given the backdrop of an increasing geopolitical global finance, more scholarly dialogue between political economy and security studies might be warranted, especially in the context of a financial system where non-Western actors are seemingly gaining power. Finally, what are the implications for conceptualizations of financial globalization, financialization or neoliberalization in ongoing debates about convergence or path dependency of national capitalisms in the face of a more heterogeneous, potentially more developmental global financial system? This paper does not claim to provide answers to all these questions. Yet with financial activity within the global economy gradually shifting towards the East, we argue that more research is needed to explore this new world in which global financial transactions increasingly take place.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (211.4 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Aaron Benanev, Amrita Narlikar, Andreas Nölke, Andrew Hurrell, Charlotte Rommerskirchen, David Yarrow, Hielke Van Doorslaer, Iain Hardie, Katrijn Siderius, Mark Hallerberg, Matthew Watson, Manolis Kalaitzake, Michael Zürn, Ruben Kremers, Sahil Dutta, Steffen Murau, Tanja Börzel, Tim Summers, Tobias Pforr, Tobias ten Brink and the participants of the Warwick Critical Finance 3.0 Manuscript Development Workshop for their comments on earlier versions of this paper. A great thanks also to Apolline Simons, Florian Dierich and Robin Jaspert for their research assistance, and to three anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Fabian Pape

Fabian Pape is a Fellow in International Political Economy at the London School of Economics and Political Science. His research interests include monetary theory, central banking, and the institutional configuration of money markets.

Johannes Petry

Johannes Petry is the Principal Investigator of the DFG-funded StateCapFinance project at Goethe University Frankfurt and CSGR Research Fellow at the University of Warwick. He researches the internationalisation of China’s financial system, market infrastructures in the politics of global finance, and post-crisis transformation of the global financial system.

Notes

2 Interview_5, interview_8, interview_20, interview_29, interview_39, interview_42

3 We thank an anonymous reviewer for this point.

4 This reasoning follows a ‘second image’ approach, demonstrating how domestic factors explain changes at the international level (Katzenstein, Citation1985); also Kalinowski Kalinowski (Citation2013).

5 https://www.swfinstitute.org/fund-rankings/development-bank (07-Mar-2022).

10 Interview_5, interview_9, interview_11, interview_15, interview_31, interview_41

11 In contrast, Europe only accounts for 22.8% (stocks), 12.0% (futures), 14.8% (bonds).

12 Interview_7, interview_17, interview_19, interview_26, interview_32, interview_36, interview_43, interview_44

13 Interview_10; also: interview_6, interview_41

15 Interview_4

16 Interview_8, interview_27, interview_36, interview_39

17 Interview_4

18 Interview_8

19 Interview_6, interview_36

20 Interview_15

21 Interview_14

22 Interview_1, interview_37, interview_46

23 Interview_22, interview_32, interview_33, interview_36, interview_45

25 Interview_47

26 Interview_29.

27 Interview_21, interview_37, interview_41

28 Interview_32

29 https://www.reuters.com/markets/stocks/taiwan-prods-state-owned-banks-buy-stocks-market-falls-sources-2022-03-08/, https://www.regulationasia.com/korea-to-relaunch-stock-market-stabilisation-fund-this-month/, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/when-stocks-crash-china-turns-to-its-national-team/2022/03/15/bd4d319e-a4d8-11ec-8628-3da4fa8f8714_story.html

30 Interview_35, interview_44

32 https://www.asianinvestor.net/article/korean-fund-giants-kic-and-nps-to-ramp-up-esg-stewardship-on-overseas-investments/472344; also: interview_27, interview_48.

33 Korean construction companies have outstanding orders worth USD98.9bn (2018) from South/Southeast Asia.