Abstract

In recent years, IPE research has increasingly tried to better understand the nature and implications of China’s rise in a changing global landscape. However, in IPE teaching, China is often treated as an afterthought to a familiar transatlantic story. IPE students thereby are not adequately prepared to explain important developments in the 21st-century global economy, their underlying causes, mechanisms and particularities. This article provides a roadmap for rethinking the IPE curriculum. In an initial step, we suggest incorporating more comparative political economy into the teaching of IPE theories to create an analytical sensitivity for understanding (Chinese) state-market relationships that significantly diverge from Western-centric narratives. In a second step, these conceptual frameworks should be taken into account when teaching core IPE issue areas such as finance, development, production and trade, in which we argue China must be treated as an integral part rather than an outlier of IPE teaching. Such a revised curriculum, we argue, equips students with the conceptual tools and empirical knowledge for understanding diverging domestic institutional configurations of different economies, and thereby enables students to analyze, compare and critically evaluate fundamental assumptions and arguments about how the global economy functions in the context of a rising China.

Introduction: China in IPE teaching

China’s rise and its implications for the global political economy have become central research topics in IPE scholarship. From China’s growing footprint in development finance (Chin & Gallagher, Citation2019; Chen, Citation2020) and the geopolitics of the Belt-and-Road-Initiative (Beeson, Citation2018), to whether China challenges the liberal international order (LIO) in areas such as trade (Weinhardt & ten Brink, Citation2020), finance (McNally & Gruin, Citation2017; Petry, Citation2021) or global governance (Breslin, Citation2013; de Graaff et al., Citation2020), IPE scholars have been trying to better understand the impact of China’s rise in a changing global context (Chin et al., Citation2013). Given China’s growing global importance, does contemporary IPE teaching provide students with the tools to explain 21st-century shifts in the global economy, their underlying causes, mechanisms and particularities?

While China has become increasingly central in IPE research, it remains curiously absent in IPE teaching. Our analysis of IPE textbooks and syllabi shows that students are equipped with neither the conceptual tools nor the empirical knowledge for understanding China’s political economy and its impact on core IPE issue areas. Prominent IPE textbooks often describe China as an afterthought to a familiar transatlantic story. The most-read textbook, Oatley (Citation2019) for instance, discusses Germany in more detail than China.Footnote1 Notwithstanding the former’s role as a manufacturing power, the latter is arguably much more central to understanding contemporary changes in the global economy. Neither do IPE syllabi place a particular emphasis on China. This is highly problematic since Western-centric IPE teaching creates an important blind spot that makes it difficult to understand crucial shifts in the global economy (Bhambra, Citation2021). We therefore argue that China must play a much more important role in IPE teaching.

This article provides both a rationale and roadmap for rethinking the IPE curriculum to properly understand China and its impact on the global economy. In an initial step, IPE teaching must integrate more comparative political economy (CPE) into its conceptual toolkit since China contradicts the state-market dichotomy that informs much of conventional IPE teaching. A greater emphasis on CPE approaches, we argue, would provide students with the analytical sensitivity to understand not only China’s political economy and rise, but also other economies whose institutional configurations and state-market relationships differ from Western (typically Anglo-American) conceptions that dominate IPE teaching. In a second step, China needs to be treated as an integral part rather than an outlier in empirical analyses of the global economy. Therefore, we argue that IPE syllabi need to incorporate more China-focused research in their investigation of core issue areas. Such a revised IPE curriculum enables students to analyze, compare and critically evaluate fundamental assumptions and arguments about the global economy, thereby equipping the next generation of IPE scholars and policymakers with the conceptual tools and crucial knowledge to understand the 21st century global economy in the context of a rising China.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 discusses the different engagement with China in IPE research and teaching. Section 3 demonstrates how the IPE curriculum can be complemented with CPE approaches to convey the necessary conceptual tools for understanding China’s political economy and consequently global impact. Focusing on core IPE issue areas (global trade, production, finance, development), section 4 demonstrates how adding China-focused research to the IPE curriculum would provide students with crucial knowledge to analyze a changing global economy. Section 5 concludes and outlines further avenues of exploration.

Reviewing the IPE curriculum: the curious absence of China in IPE teaching

A mismatch exists between IPE research and teaching on China. Based on analyses of IPE publication patterns and IPE teaching material (textbooks/syllabi), we demonstrate that while increasingly central in IPE research, China is mostly neglected in IPE teaching.Footnote2

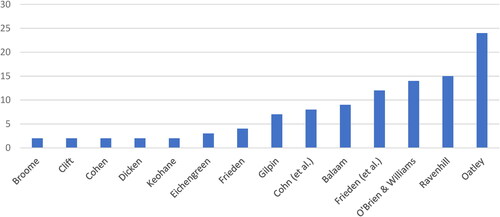

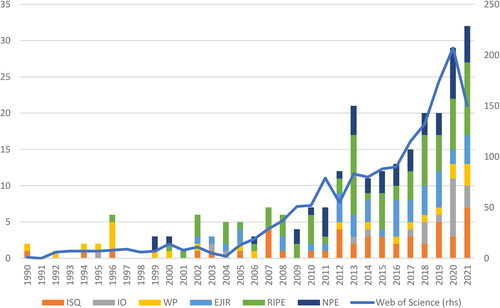

China’s growing centrality within IPE research is evident in academic publication patterns (). While only 59 China-focused articles were published in leading IPE journals in 1990–2009, China has been the subject of 68 articles in 2020 and 2021 alone.Footnote3 An analysis of the Web of Science database reveals a similar growth of China-focused IPE research in ‘Political Science’/‘International Relations’ journals more broadly. Whereas China was only the subject of 100 IPE-articles by the mid-2000s, since then almost 1,500 articles had been published on this topic. Accounting for only 2.36% of all published IPE research in the 1990s, China-focused articles represented 11.37% of all IPE publications in the 2010s, even increasing to 16.49% in 2020–2022. Over time, China has become a central node in IPE research.

Figure 1. China’s growing importance for IPE research.

Source: Web of Science, journal websites; *excludes online first articles (2021).

In contrast, there is a curious absence of China when it comes to IPE teaching. To this end, we analyzed whether and how the ‘conventional’ IPE curriculum—consisting of the most-used IPE textbooks (n = 7) as well as a large sample of IPE syllabi (n = 128)—engage with China.Footnote4

First, we analyzed the most-used IPE textbooks. We identified these by coding textbooks taught in IPE classrooms based on our IPE syllabi sample ().Footnote5 Textbooks matter because ‘[they] are at the heart of IPE teaching and crucial sources of initial knowledge for students’ (Baumann, Citation2021, p. 4). They determine what the discipline deems as ‘mainstream’ or ‘legitimate’, thereby setting disciplinary standards and defining the boundaries of the field (Clift et al., Citation2022). As de Carvalho et al. (Citation2011, p. 738) note, the importance of textbooks goes beyond teaching ‘as many active researchers become increasingly reliant on textbook-knowledge of issues that are not directly related to their own areas of expertise’(also Seabrooke & Young, Citation2017). However, core IPE textbooks do not sufficiently engage with China.

We first analyzed how many index entries on China exist compared to other countries (Table D, appendix), and see increasing mentions of China over time. While Japan and Britain were most prominently discussed in the 1st editions of IPE textbooks, China is now mentioned more often in most textbooks (with the exception of Oatley Citation2019, the most-used textbook). However, China is only discussed as an addition to an existing narrative that focuses on Western-led global institutions, which is also indicative by the absence of structural changes in those textbooks.

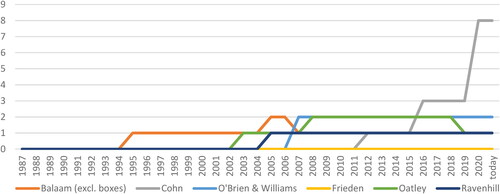

We then analyzed textbooks’ table of contents. Even in their latest editions (2017–2020), not one IPE textbook had a chapter dedicated to China (122 chapters in total). The picture is only slightly better for sub-chapters with 13 sub-chapters (+3 text boxes), representing merely 2.5% of all sub-chapters (735). Only Cohn and Hira (Citation2020) substantially added subchapters that focus on China’s impact on the global political economy, discussing its impact on trade, technology, development and investment patterns. Other textbooks’ engagement remained small in this respect ().

Figure 3. Subchapters on China in different IPE textbook editions (1987–2020).

Source: author’s calculation.

Importantly, these textbooks are frequently updated (except Gilpin, Citation2001) and were recently published in their 6th–8th edition (2017–2020). They hence had ample opportunity to revise their curriculum since their initial publication (1987–2005) to incorporate insights from the growing body of China-focused IPE research. Importantly, we are not arguing that there is no engagement with China; there is clearly an acknowledgement given China’s increasing indexation. However, this engagement is neither systematic nor supported by appropriate conceptual tools to make sense of China’s rise (see section 3).

To complement our textbook analysis, we also analyzed a large dataset of IPE syllabi. Our sample consists of 128 syllabi in ‘International/Global Political Economy’ from undergraduate (70) and postgraduate courses (58), predominantly from North America (67), Europe (30), Asia-Pacific (22), Latin America (8) and MENA (1) that were on average taught in 2018 (see appendix 1). Syllabi are important since course instructors might compensate for the lack of China-related material in IPE textbooks by assigning readings from the growing China-focused research literature discussed above.

However, besides readings from core IPE textbooks, only 58 syllabi out of our sample taught any additional content on China—meaning that more than half of our sample did not include any China-related readings at all.Footnote6 In a total of 1,707 individual sessions, only 83 sessions discussed China-focused textsFootnote7 that had been assigned as core (78) or advanced (65) readings (). Assuming an average of two core readings per session, only 2.28% of all readings were China-related; this is not even representative of China-focused IPE research in the 1990s. One might assume topics not considered part of the core curriculum but nonetheless important be included in advanced readings, but these fare even worse.

Table 1. China in IPE syllabi.

This lack of systematic engagement is similar for other countries and symptomatic for a broader problem within IPE teaching. The way IPE is narrated in textbooks and syllabi seems to be stuck in the 20th century. The development of the global economy is framed as a familiar Western story characterized by Bretton Woods, US hegemony and liberal internationalism that remains Eurocentric (Baumann, Citation2021; de Carvalho et al., Citation2011), neglecting the institutional diversity of state-market configurations in countries beyond the Western/Anglo-American core. This is not only problematic for the reasons highlighted by recent calls to decolonize the curriculum (Bhambra, Citation2021; Mantz, Citation2019), but also because it does not adequately explain one of the most important developments in the world economy: the rise of China.

While increasingly central for IPE research, China is largely neglected in IPE teaching. The conventional IPE curriculum neither provides students with the right conceptual tools to understand China’s political economy (section 3), nor engages with the changing empirical realities of the 21st-century global economy in which China’s rise has been complementing, contesting or altering the norms, rules and procedures that govern international economic relations (section 4). We thereby provide a roadmap for IPE instructors of how to incorporate China into their IPE curriculum—both conceptually and empirically—to remedy these shortcomings.

Conceptual blind spots and the state-market dichotomy: the need for incorporating CPE into IPE teaching

The relationship between states and markets is at the core of theoretical discussions in IPE, propagating particular modes of interaction between states and markets as intertwined but largely separate entities (Gilpin, Citation2001; Schwartz, Citation2018; Strange, Citation1988). But the emergence of China challenges this analytical framework (Gruin, Citation2019; Naughton & Tsai, Citation2015; ten Brink, Citation2019). It presents an ‘outlier’ where the boundary between state and market is significantly blurred, challenging the state-market dichotomy in conventional IPE conceptualizations (Massot, Citation2020).

This conceptual blind spot can only be remedied by introducing CPE approaches into the IPE curriculum, which is so far largely absent from IPE teaching. Essentially, CPE demonstrates how different national institutional configurations create different state-market relationships, which is crucial for understanding the global economy. As Katzenstein (Citation1976) long noted, ‘foreign economic policy can be understood only if domestic factors are systematically included in the analysis’. Actors within national institutional contexts are not just ‘passive recipients’ of pressures emanating from the global economy, but ‘play an active role in shaping its dynamics’ (Clift, Citation2021, p. 38; also Nölke, Citation2011). Consequently, the more a country’s state-market configurations differ from IPE’s conventional state-market dichotomy and the larger its global impact is, the more important it is to convey such conceptual frameworks to IPE students. We hence argue that CPE approaches are direly needed to understand China and how its differing state-market relationships impact the global economy.

China’s state-market boundary appears rather 'blurred’. Despite the presence of a vibrant private sector, major economic actors are state-owned, most prominently state-owned enterprises (SOEs) (Milhaupt & Zheng, Citation2015) and state banks (Chen, Citation2021). While undoubtedly state-led, these actors are also products of market-oriented institutional reforms, pursuing commercial strategies despite state ownership and competing with their (privately-owned) Western counterparts on international markets. This leads to a more fundamental question—how to understand state-market relations in a Chinese context?

China is not the only case where the state-market dichotomy is blurred. CPE literatures on varieties of capitalism (VoC) (Hall & Soskice, Citation2001), developmental states (Amsden, Citation2011) or industrial catch-up (Chang, Citation2002) have discussed the varying role of states within domestic institutional arrangements in nurturing markets with respect to Continental European and East Asian economies; and these approaches can also be helpful to (at least partially) understand China’s different state-market configurations. Yet the state-market configuration in China differs significantly from these cases. In China’s post-reform and opening-up era, ‘markets’ grew out of ‘the state’. Scholars of China’s political economy have highlighted this state-permeated nature of Chinese markets (ten Brink, Citation2019), demonstrating for instance how the state regulates industrial sectors (Hsueh, Citation2011), utilizes finance to achieve development objectives (Gruin, Citation2019), or how markets exist as part of a state-centered economic order (Zheng & Huang, Citation2018), aiming to advance existing literature and conceptualize China’s state-market relationship (Naughton & Tsai, Citation2015).

This ambiguity in conceptualizing China leads to a larger problem for IPE teaching—how to understand China’s interplay with the global political economy, or more broadly, how to understand the world in the context of a rising China. When China is not systematically explored through teaching material, students might come to a very reductionist understanding of China—conventional wisdom labels China as ‘state-led’ and as an illiberal authoritarian state whose emergence threatens the stability of the US-led LIO. The result of China’s rise, according to this logic, is either China’s compliance (Steinfeld, Citation2010) or contestation (Allison, Citation2017).

However, China is not just an ‘illiberal’ rising power. As illustrated above, China’s major economic actors demonstrate strong market orientation despite state ownership. Further, rather than being a monolithic actor, the Chinese ‘state’ consists of a variety of actors with often diverging interests and capabilities like municipal, provincial and central governments, different ministries/regulatory agencies or party factions (Shih, Citation2007; ten Brink, Citation2019). Moreover, China has been supporting international trade and global markets, benefiting largely from globalization and also becoming dependent on this openness (Liu & Tsai, 2021). This mixture of ‘stateness’ and ‘marketness’ of the Chinese economy therefore suggests that China’s impact on the LIO cannot simply be reduced to compliance/contestation but is more complicated. China’s rise therefore challenges current IPE teaching, which has been centered primarily on analyzing US-led/dominated international institutions, norms and power constellations.

In response to these intellectual puzzles, IPE research has begun to examine the challenges to/decline of the LIO in the context of China’s rise (de Graaff et al., Citation2020; Ikenberry, Citation2018; Lake et al., Citation2021). While some suggest an analytical focus on international regimes/specific issue areas rather than an overarching LIO (Johnston, Citation2019), as China’s interactions with them differ from one another (Petry, Citation2021; Weinhardt & ten Brink, Citation2020), others point out the necessity of understanding China’s domestic political economy in explaining its differentiated impact on the global economy (Germain & Schwartz, Citation2017; McNally & Gruin, 2017). Importantly, this literature heavily leans on CPE approaches to make sense of how China’s differential state-market relationships inform its global rise (cf. Massot, Citation2020; Nölke, Citation2015).

We therefore analyzed whether IPE teaching explicitly included sessions on: (1) VoC; (2) developmental state; (3) state capitalism; or (4) China’s political economy itself. These approaches range from least to most helpful for understanding China’s and other non-Western state-market configurations. However, our analysis indicates that not much effort has been made in offering appropriate CPE concepts to explain this ‘outlier’ and how it has largely reshaped the global economy.

Out of all China-related subchapters (16) in core IPE textbooks, most focus on China’s impact on specific issue areas such as trade or development. Only two subchapters focus on China’s political economy by looking at ‘China in transition’ (Balaam & Veseth, Citation2018) and ‘Economic reform in China’ (Oatley, Citation2019). Conceptual approaches that might help better understand China’s differing political economy are largely absent. Only one textbook has a theoretical chapter on national capitalisms (Gilpin, Citation2001), with the next-closest being discussions of East Asian developmental states in chapters on ‘development’. Otherwise, we find that mercantilism/economic nationalism/realism is the default option in IPE teaching to discuss (Chinese) state intervention into markets (think, trade barriers), but this perspective usually retains IPE’s state-market dichotomy without unpacking differences between political economies.Footnote8 Discussions of China with respect to key words such as ‘capitalism’, ‘markets’ or ‘development’ mostly focus on the empirical story of China’s growth rather than providing theoretical insights that might advance students’ understanding of China’s state-market relationship (Table D, appendix). Overall, there is very little engagement with CPE in IPE textbooks.

The picture for IPE syllabi is only slightly better. Out of 559 sessions on history, methods and theories, we find that only few syllabi included sessions that could potentially help students understand China’s differing state-market relationship.Footnote9 While many syllabi include sessions on mercantilism/economic nationalism, CPE approaches are only taught in 26 syllabi (40 sessions)—in other words, 80% of IPE syllabi do not teach CPE at all. Thereby, most syllabi focus on the VoC framework that contrasts Western coordinated and liberal market economies (16). Although this perspective is helpful to understand differences between national institutional settings, the state is usually absent in this firm-centered approach, making it difficult to analyze differing state-market interactions. A few sessions discuss perspectives that combine these two aspects, focusing on East Asian developmental states (15), state capitalism in emerging markets (4), or China’s political economy itself (5).

What can we do to fill in this conceptual lacuna? Our proposition is that a necessary condition to provide students with the theoretical toolkit to better understand China is to add at least one CPE session into our IPE syllabi, introducing students to CPE approaches and incorporating literatures on such as VoC, developmentalism and state capitalism. Such a revised curriculum lays a foundation for understanding Chinese state-market relations and their global impact. More broadly, it nurtures an analytical sensitivity for and equips students with the conceptual tools for understanding the greatly diverging institutional configurations and state-market interplay of national economies and how they influence the global activities of economic actors, beyond the Anglo-American core. Second, given China’s importance and unique characteristics, we propose that the revised curriculum could also include some readings that provide students with a better understanding of China’s political economy, since its particular state-market relationship and institutional configurations increasingly shape the global economy (see section 4).Footnote10

20 years ago, Gilpin (Citation2001, p. 148) noted that IPE scholars ‘have given insufficient attention to the importance of national economies to the ways in which the world economy functions’. While IPE research has increasingly engaged with CPE insights (Clift, Citation2021; Katzenstein, Citation1976; Nölke, Citation2015), IPE teaching has not significantly increased its engagement with CPE approaches over time. The variegating domestic configurations of different economies are hardly illustrated empirically or explained conceptually in IPE classes, making it difficult for students to understand a dynamically changing global economy. While this pertains to most countries, China’s extraordinary global impact with its economic model that significantly diverges from state-market interactions in the West that inform conventional IPE teaching material makes this integration of CPE and IPE more urgent than ever.

Incorporating China in the IPE curriculum

Advancing theoretical discussions is not enough, however. We further argue that a sufficient condition for better understanding the 21st-century global economy is to incorporate these conceptual insights into empirical discussions of core issue areas in the IPE curriculum: global trade, finance, development and production (see Table A, appendix).

For each area we briefly outline how they are currently taught and illustrate their lack of engagement with China. We then show why this is problematic since China increasingly matters both quantitatively and qualitatively for each issue area. We finally demonstrate that by complementing existing syllabi with China-focused research which reflects CPE conceptual insights, IPE teaching can provide students with a much better understanding of the global economy in the context of China’s rise.

China in global finance

The development of the global financial/monetary system is usually taught as a story of the re-emergence of global finance following the collapse of Bretton Woods. Floating exchange rates facilitated financial innovation and internationalization of financial activities, while markets were freed from their interwar constraints through abolishing capital controls and liberalizing national financial systems, resulting in the (re)emergence of global financial players centered around Anglo-American financial markets (Helleiner, Citation1996). As the subtitle of Susan Strange’s (1998) Mad Money indicates, IPE’s story of global finance is one ‘when markets outgrow government’, prominently discussing the structural power of finance over states (hot money, investor strikes, credit ratings) or US financial power (dollar hegemony, Wall Street-Treasury-Complex). This framing draws strongly on the familiar state-market dichotomy in IPE teaching.

In this narrative, China plays only a very subordinated role in IPE textbooks with sporadic references to its foreign exchange (FX) reserve accumulation, sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) or RMB internationalization (Balaam & Veseth, Citation2018, pp. 211–212; Frieden et al., Citation2017, pp. 216–217; O'Brien & Williams, Citation2020, pp. 199–200); only Cohn and Hira (Citation2020, pp. 162–164, 204–206) have longer sub-sections discussing China’s currency and financial system. In our sample of IPE syllabi entailing 305 sessions on global finance, only 12 syllabi have readings explicitly addressing China (11 core/6 advanced readings), focusing on RMB internationalization, Chinese overseas lending and FX management.

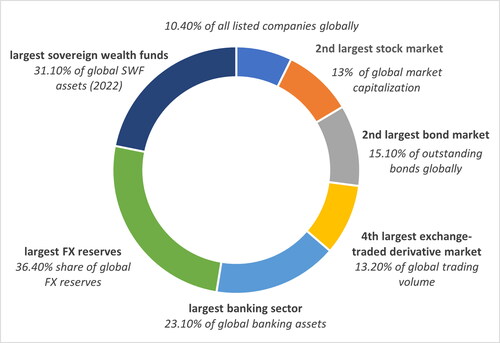

While China’s financial system only started to develop in the 1980s, it has become increasingly central for the contemporary global financial/monetary system (). By 2020, China’s financial markets and banking sector were among the world’s largest, controlling ∼1/3 of global SWF assets and the world’s largest FX reserves. In areas such as FinTech (consumer finance/mobile payments) and central bank digital currencies, China has even emerged as a global leader.

Figure 4. China’s increasing importance in the global financial system.

Sources: WFE, World Bank, ICMA, FIA, Statista, S&PGlobal, Bloomberg Terminal, InstitutionalInvestor, GlobalSWF.

China’s financial system, however, functions differently from global finance. Taking seriously CPE insights in analyses of Chinese finance helps elucidate these differences. While Chinese financial actors are often commercially oriented, the state has an outsized and qualitatively different role in the financial system. First, many of China’s largest financial institutions are (partially) state-owned, motivated by both commercial and policy objectives, significantly blurring the state-market dichotomy. Second, rather than self-/light-touch regulation, financial regulation in China is ‘Leninist’ (Collins & Gottwald, Citation2014), with regulatory actions being more frequent, encompassing and disruptive. Third, the tremendous growth of Chinese finance takes place within a political-economic system where the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) maintains control over socio-economic development (Gruin, Citation2019), thereby aligning market outcomes with state policy (Petry, Citation2020). These configurations have several international implications.

First, despite these differences, global finance is investing into China. By 2021, US investors alone hold an estimated USD1.2 trillion of Chinese assets.Footnote11 China’s financial system promises seemingly unlimited profit opportunities, especially compared to already saturated, highly financialized Western markets; China is therefore at the new frontier of financial globalization. Yet China’s financial opening up maintains a distinctively state-capitalist logic (Petry, Citation2021). Consequently, Western financial actors accept, adapt to and even legitimize China’s illiberal rules (McNally and Gruin, Citation2017).

Second, Chinese financial actors are themselves increasingly venturing abroad, challenging the conventional IPE story of unfettered, market-based finance. By December 2021, Chinese banks represented 26% of lending to developing markets and 7.5% of overall cross-border lending.Footnote12 This activity significantly differs from Western creditors, since Chinese overseas investments are not purely commercially oriented but also informed by Chinese state policies (Kaplan, Citation2016).

Third, China is globalizing and thereby diversifying financial governance. China has led the post-crisis charge for a multipolar financial system (RMB internationalization), increased its presence within existing international financial institutions (IMF-SDR inclusion), spearheaded the creation of new institutions (AIIB) and created alternative financial spaces (Petry, Citation2022). Yes, China’s political economy impacts these developments. With respect to RMB internationalization, for instance, rather than global investor appetite for RMB-denominated assets, domestic policy considerations are crucial for its lack of progress (Germain & Schwartz, Citation2017).

An analysis of China’s relation towards the liberal financial order must therefore be grounded in an understanding of China’s differential state-market relationship. As China becomes the world’s second largest financial power, IPE teaching must engage more thoroughly with its varied set of financial actors and institutional configurations.

China in global development

Written through the lens of advanced industrial economies, most IPE textbooks hint at a hierarchical relationship between rich and poor when describing ‘development’. Students learn how Western-backed institutions like World Bank, IMF and OECD-Development Assistance Committee have assisted the development of the ‘lagged behind’. Development assistance is perceived as charitable gift-giving (Mawdsley, Citation2012), fundraised through taxation in high-income countries and distributed to low- and middle-income countries on concessional terms, differing substantially from private-led, profit-seeking capital that is unlikely to favor less developed regions and less lucrative projects.Footnote13 This often came with strings attached. Especially since the 1980s with the emergence of the (post-)Washington Consensus, development assistance was tied to neoliberal policies like fiscal discipline, tax reform, trade/investment liberalization or financial deregulation. While development aid was charitable, it was also conditional, measured by ‘good governance’ and often linked to structural adjustment programs.

Since the 2000s, however, China has emerged as a major actor in global development. AidData recorded Chinese overseas development finance between 2000–2017 worth USD843 billion, across 13,427 projects and 165 countries.Footnote14 Today, Chinese state banks are as—if not more—influential than Western institutions. This has generated a body of scholarship that rethinks the nature of development finance. China does not rely on fiscal revenue to support development projects but employs various market instruments to capitalize large-scale infrastructure projects nationwide and internationally (Chen, Citation2020). Some see China’s state-supported, market-based finance as a revival of Japan’s ‘development investment’ approach, as Chinese loans support national firms’ exports (Saidi & Wolf, Citation2011). Others interpret it as part of a collective rise of the Global South involving not only China but also India, Brazil and other developing countries which, unlike traditional donors, highlight reciprocity and business benefits from development cooperation (Mawdsley, Citation2012).

This has reshaped global development governance in several ways. First, it complements existing Western-led regimes as much of Chinese development finance goes to countries receiving limited aid from OECD donors (Chin & Gallagher, Citation2019). Moreover, as Kaplan (Citation2016, p. 643) notes, Chinese lending has allowed developing countries to escape the budget constraints traditionally imposed by Western actors. Second, China partially exports its own export-oriented and infrastructure-driven development model through state-guided financing, for instance, by creating export processing zones/industrial parks, actively mobilizing Chinese enterprises/banks to explore overseas market and building/funding large infrastructure and industrial projects (Bräutigam & Tang, Citation2014). This approach differs starkly from both Western development aid and private investment flows. Third, China’s rise as a major development-finance provider has accelerated a major shift in the global development landscape. Western-led institutions have started to advocate narratives/practices associated with Southern development partners: from loosening policy conditionality (Hernandez, Citation2017), to emulating China’s infrastructure-driven development finance (Zeitz, Citation2021) and promoting market-oriented development finance, partially in attempts to rival China’s growing influence in the developing world through advocating and incorporating government-mobilized private investments into development finance (Gabor, Citation2021).

IPE teaching on development has not reflected these major changes. China only plays a minor role in IPE textbooks with reference to global development (O'Brien & Williams, Citation2020, p. 238) or as example of South-South cooperation (Balaam & Veseth, Citation2018, pp. 305–307, 688–689). Only Cohn and Hira (Citation2020, pp. 383–387, 420–422) and Oatley (Citation2019, pp. 158–159) properly discuss China’s alternative model for development and its challenge to existing paradigms. Out of 131 sessions on development, only 10 syllabi include China-related readings (10 core/5 advanced readings) which discuss Chinese development lending and its characteristics (see appendix 2).

Failing to understand the differences between Chinese and Western approaches of development assistance/finance often leads to false conceptual and policy conclusions. While the Belt and Road Initiative, for instance, fueled discussions over the emergence of a ‘China Model’ that challenges the US-led Washington Consensus, China scholars caution against such sweeping generalizations by highlighting the contentious debates within China about how to characterize Chinese economic governance (Ferchen, Citation2013). In order to understand these ongoing discussions and debates, IPE students must gain a better understanding of China’s development approach and its variegated global impact.

China in global production

IPE teaching on global production usually focuses on its transformation through the emergence of Western multinational corporations (MNCs). The business activities of these private corporate actors span the globe in search for profits, thereby dominating global value chains (GVCs) which produce goods/services largely for Western consumer markets. They channel vast amounts of foreign direct investment (FDI) between countries and hoard most of the world’s industrial knowledge through intellectual property rights. Thereby, MNCs have also become immensely powerful vis-à-vis states, with consequences ranging from tax evasion in developed countries, questions of FDI dependency and neo-colonialism in developing countries, to a race to the bottom in environmental/labor regulations across nations. This narrative is largely informed by the state/market dichotomy that underlies much of IPE teaching.

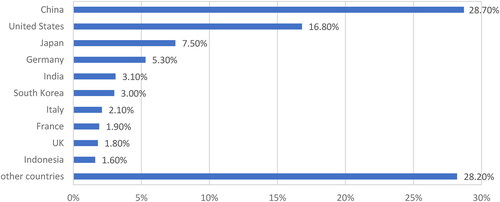

In most teaching material on global production, China is largely ignored. Among our textbooks, only Ravenhill (Citation2020) has a dedicated sub-chapter on ‘China as the world’s factory’. Other textbooks only partially discuss China’s role in global production, describing its impact on the global division of labor (O’Brien & Williams, Citation2020, pp. 224–227), industrial policy (Balaam & Veseth, Citation2018, pp. 119–120) or outward investments (Cohn & Hira, Citation2020, pp. 337–338). This neglect of China is not remedied in IPE syllabi either: out of 103 sessions on global production/MNCs, only 6 courses include China-focused readings (6 core/2 advanced). However, as Thun (Citation2020, p. 188) notes, ‘the impact of China on global manufacturing is difficult to overstate’; after all, China accounted for 28.7% of global manufacturing output by 2019, by far outpacing its competitors ().

There are at least three dimensions of this development that IPE teaching needs to incorporate. First, there is lacking acknowledgement that China enables global production in its contemporary form. Without China’s ‘competition-driven form of state-permeated capitalism with a heterogenous internal structure’ (ten Brink, Citation2019, p. 13), there would have never been a seemingly endless supply of cheap labor to man the world’s factory. While central authorities utilized policy experimentation to facilitate China’s controlled opening (Heilmann, Citation2008), individual municipal/provincial authorities competed for FDI and institutional structures (e.g. the hukou system) suppressed wages and consumption. Focusing mainly on the globalization of Western MNCs misses crucial factors that not only shape the contemporary structures of global production but also help explain its political repercussions. The backlash against outsourcing/globalization, exemplified by the US-China trade war, can only be fully understood when taking into consideration China’s domestic context.

Second, China’s rise as a large consumer market affects the activities of MNCs, which previously produced mostly for Western consumer markets. Today China is the world’s second largest consumer market,Footnote15 accounting for 25% of global consumption growth (compared to 7% in 2000)Footnote16 and Western MNCs with their market-based business approaches have to take into consideration China’s political factors to a much larger degree. As O’Connell (Citation2022) illustrates, China’s growing role as consumer market increases self-censorship by MNCs, since taking a stance on politically sensitive topics can lead to boycotts/bans that seriously threaten their revenues.Footnote17 While MNCs could afford to boycott certain other countries, they have become significantly dependent on what will probably soon be the world’s largest consumer market.

Third, China changes the politics of global production as Chinese companies are becoming global players themselves. In 2000, only 9 Chinese companies made the Fortune Global 500. By 2021, the list included 135 Chinese companies (including 82 SOEs), outnumbering the US (122). These companies are increasingly venturing abroad, creating their own GVCs, penetrating consumer markets and accumulating intellectual property.Footnote18 The global composition of MNCs is changing, and so are the state-market relationships that underpin global production. Compared to Western MNCs, the Chinese state is much more entangled with Chinese corporations and facilitates their internationalization (Malkin, Citation2022; Zhu, Citation2018).Footnote19

Yet China’s economic transition has loosened direct state control and turned Chinese companies, even SOEs, into commercially viable entities with considerable technical expertise and operational leeway, especially in their international activities. As Norris (Citation2016) highlights, instead of simplifying the rise of China’s MNCs as a grand strategy orchestrated from Beijing, it is important to identify the conditions under which Chinese authorities can utilize commercial actors to facilitate economic statecraft.

Overall, China’s rise fundamentally challenges narratives in IPE teaching that mostly focus on Western MNCs. IPE teaching must take into consideration China’s influence on global production, consumption and corporations by more explicitly drawing on China-related research.

China in global trade

In most IPE textbooks, students learn about the rise of free trade as a core component of the post-war LIO (Ikenberry, Citation2018). Western-led multilateral institutions like the WTO and OECD determine how cross-border trade functions and restrain member states from over-subsidizing national business. Trade liberalization has thereby become more intrusive, increasingly promoting domestic policy reforms. Supposedly benefiting from joining the global trade system, countries are incentivized to conform with its market-based rules. A strong state is ‘legitimized’ only for late development and industrial catch-up (Amsden, Citation2011), despite the fact that now-developed economies have all employed protectionist policies during their own industrialization (Chang, Citation2002).

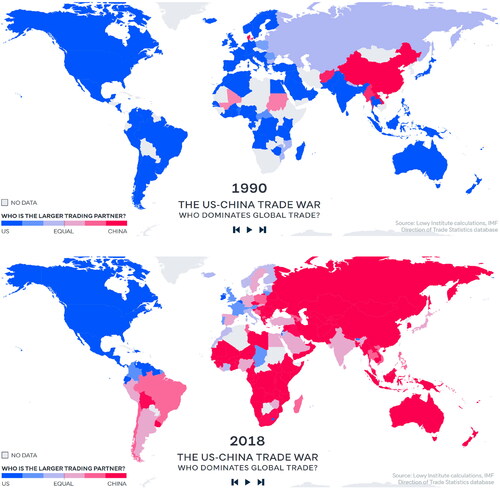

Over the last decades, China has emerged as the world’s largest trading nation (). Yet, most IPE textbooks ignore the profound changes China has brought to global trade, only briefly discussing its role in the WTO (Balaam & Veseth, Citation2018, pp. 176–177; Frieden et al., Citation2017, pp. 254–255) or more generally the emergence of the BRICS in global trade governance (Cohn & Hira, Citation2020, pp. 245–249). In our syllabi sample, among 247 sessions on global trade, only 6.48% of sessions include China-related content across 16 syllabi (10 core/12 advanced readings).

Figure 6. China’s emergence as world’s largest trading nation.

Source: https://www.visualcapitalist.com/china-u-s-worlds-trading-partner/

However, China’s emergence has brought conceptual challenges to the prevailing IPE trade narrative. The first challenge is China’s duality as state-led economy but also beneficiary of the international trade system. China’s export-oriented growth model has benefited largely from trade liberalization, especially since its WTO accession in 2001, and still officially claims to be a strong supporter for multilateral trade mechanisms and economic openness.Footnote20 Chinese SOEs have emulated Western companies in reshaping their organizational structure/operating models, conducted large-scale cross-border M&As and listed on overseas stock exchanges, ‘playing the game’ created by Western industrial economies (Steinfeld, Citation2010). Yet, the Chinese state kept a tight grip over enterprises in strategic sectors even though government-business ties have been significantly refashioned through market-oriented reforms (Milhaupt & Zheng, Citation2015). Major state banks offer large-volume loans and finance industrial parks to support the international expansion of enterprises (both state-owned and private), nurturing national champions with global competitiveness, and finance infrastructure projects that could collectively reshape the contours of global trade. Ambiguous government-business ties muddle the argument that China would entirely comply with Western rules and norms, and emerging research has thus examined the conditions under which China is a rule maker, rule follower or rule breaker in global trade (Hopewell, Citation2020; Weinhardt & ten Brink, Citation2020).

The second challenge is the rise of China as both a developing country and major challenger to the US-led global trade governance (Hopewell, Citation2020). China is not the first country that has employed state support to facilitate international export and investments. IPE textbooks, for instance, discuss Japan’s state-led, export-oriented ‘economic miracle’ in the early post war decades and European countries’ employment of state subsidies to boost trade in the post-oil crisis era. Yet these industrialized ‘challengers’ did not undermine the US-led liberal trade governance. China’s rise, nonetheless, is the first time that an economy is still undergoing industrialization and thereby has ‘legitimate reasons’ to use statist instruments but has become sufficiently powerful to rival the US, the dominant rule maker.

Emergent issues in global trade, therefore, cannot be sufficiently explained with existing theories taught in IPE textbooks: a trade war between a challenger that has benefited largely from free-trade principles and a rule maker that has increasingly adopted industrial policies;Footnote21 that both China and the West have taken leadership roles in facilitating regionalism, establishing trade agreements;Footnote22 or that China has proactively participated in Western-led organizations like the WTO and yet threatens to create a gridlock of multilateral trade governance.

Without understanding differences in state-market relations between China and advanced industrial economies, IPE students may fail to explain the unprecedent changes that the global trade system is going through. Again, this calls for a more systematic incorporation of China-focused IPE research into the teaching of IPE issue areas.

Conclusion: China and the teaching of IPE in the 21st century

From its role as factory of the world to its rise in global development and its reshaping of international trade, China has become crucial for understanding contemporary changes in the global economy. While increasingly important in IPE research, China is curiously absent in IPE teaching, which often ‘others’ the Chinese experience and provides few insights for understanding the 21st-century global economy. Although China is increasingly mentioned in IPE teaching material as our analysis highlights, there is a lack of systematic analysis of and conceptual engagement with China and its global impact on core IPE issue areas such as trade, finance, production and development. China is not just an exogenous shock that suddenly disrupts the global economy but an integral part of it, and China’s integration into the global economy continues to reshape the latter’s dynamics, actors and structures.

With this paper, we aim to provide a two-step roadmap for IPE instructors to revise their syllabi in order to reflect this global tectonic shift. First, a revised IPE curriculum should incorporate CPE teaching to create an analytical sensitivity for different state-market relationships in China (and other countries) that differ substantially from Western-centric IPE narratives, thereby making sense of the significant global economic changes caused by China’s emergence. We advise IPE instructors to add at least one CPE session to their IPE syllabus. Importantly, this should go beyond Western-centric VoC and incorporate a discussion of developmentalism and state capitalism, ideally also incorporating a discussion of China’s political economy. This is the necessary condition for understanding China’s global impact.

However, advancing theoretical discussions is not enough. Second, in the absence of textbooks that sufficiently explore China’s importance for IPE issue areas (finance, development, trade etc.), we advise IPE instructors to incorporate one China-focused reading in each empirical session to systematically explore China’s global impact and complement conventional IPE narratives. Such empirical engagement with China is a sufficient condition for better understanding the changing global economy.Footnote23

By moving away from a largely Eurocentric perspective, our revised curriculum not only aims at providing a more nuanced understanding of China’s rise and its implications but also equipping students with the conceptual tools and crucial knowledge to analyze, compare and critically evaluate fundamental assumptions and arguments about how the global economy functions. Beyond China, such a curriculum potentially provides greater insights for students to understand the diverging institutional configurations of national economies beyond the Western/Anglo-American core, which are often under-examined in conventional IPE teaching. It also enables IPE students to better analyze other major shifts in the global economy like South-South cooperation, the BRICS or the growing impact of Asia (Pape & Petry, Citation2023) as well as changing state-market dynamics within Western political economies like the state’s changing role in derisking financial activity (Gabor, Citation2021).

Echoing Susan Strange’s criticism of IR and international economics (1970), we argue that the neglect of CPE in IPE teaching creates dangerous blind spots. We hope that our proposed curriculum will inspire further revisions of IPE teaching in ways that incorporate more discussion on the diversity of national economies through case-based examination, which we believe is a prerequisite for further decolonizing the IPE curriculum. In addition, we hope that our survey of IPE teaching material might spark discussions about other blind spots in IPE teaching like the lacking engagement with climate change or security - which seems striking considering contemporary societal challenges.

What we teach matters immensely for how future generations of IPE scholars make sense of the world, of which China is an evermore important part. Of course, some instructors teach additional courses that focus on ‘China and the global economy’, but China’s impact in the global economy is too outsized and poses intellectual challenges to our understanding of the global economy that are far too fundamental to leave to specialized, selective courses. Many of the IPE students end up populating the world’s universities, think tanks, corporations and public administrations. These future policymakers will have to understand and interact with China’s significant impact on global finance, development, trade and other issue areas. In a world that is becoming more fractured, equipping students with the tools to better understand China is crucial. We hope that this paper and our roadmap for revising the contemporary IPE curriculum can contribute to this endeavor.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (180.6 KB)Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Andreas Nölke, Ben Clift, Juliet Johnson, Randall Germain and Saori Katada as well as the participants of the RIPE/ISA-IPE Section Workshop (Nashville, 2022) for comments on earlier versions of this paper. We also thank Florian Dierich and Yujun Zou who assisted in the development of the dataset. Further, we are grateful to the students from our ‘China in the Global Economy’ (Free University Berlin) and ‘China and Global Development’ (Peking University) courses that enabled us to think through these issues and develop the idea for this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Muyang Chen

Muyang Chen is an Assistant Professor at Peking University’s School of International Studies. Her research examines the role of the state in development and addresses the question of how China’s overseas development finance affects global governance. She also studies how public financial agencies facilitate development assistance, export finance, and industrialization. She holds a Ph.D. from the University of Washington.

Johannes Petry

Johannes Petry is the Principal Investigator of the DFG-funded StateCapFinance project at Goethe University Frankfurt and CSGR Research Fellow at the University of Warwick. His research focuses on the internationalisation of China’s financial system, market infrastructures in the politics of global finance, and post-crisis transformation of the global financial system.

Notes

1 Measures by number of indexed pages: Germany has 31, while China has only 27 indexed pages; this measurement approach follows Baumann (Citation2021).

2 For a detailed description of data collection/coding/analysis, see Appendix 1.

3 Even 93 if counting online first articles.

4 Importantly, such a document-based analysis does not cover the nuances of IPE teaching. In many courses, China is a prominent subject in classroom lectures and discussions. However, this type of engagement relies on the individual knowledge of students/lecturers instead of collective engagement based on systematic China-focused IPE research (readings in syllabi/textbooks).

5 Selection excludes textbooks that were only mentioned once; this selection largely overlaps with IPE textbooks identified in earlier studies (Baumann, Citation2021; Clift et al., Citation2022).

6 Compared to 46.3% China-related content in the overall sample, only little variation exists between degrees (undergraduate = 41.4%; postgraduate = 50.0%) and world regions (North America = 47.8%; Europe = 43.3%; Asia-Pacific = 45.5%; Other = 33.3%); see Appendix 1.

7 Where ‘China’ or ‘Chinese’ is included in the article/chapter/book title.

8 This is also noted by Clift (Citation2021: 38), who argues that while some IPE theories such as realism/economic nationalism/mercantilism place larger emphasis on the state, these ‘assume common structural properties between states’, thereby ‘obscuring’ CPE insights on ‘a more nuanced appreciation of the changing relationship between a given state, its scope and its capacities, and the wider global political economy.’

9 From this analysis, we excluded ‘generic’ sessions (e.g. ‘theories of IPE’) which usually introduce a realist/mercantilist/nationalist-liberal/institutional-critical/constructivist triad.

10 This should at least be advanced readings for added CPE session(s).

11 https://rhg.com/research/us-china-financial/ (accessed 31 August 2022).

12 https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/global-footprint-chinese-banks (accessed 31 August 2022).

13 This donor-approach has never been the only approach to global development. Developmental states practiced development assistance in a business-driven way, tying official loans to national firms, thereby facilitating the latter's overseas market expansion. Yet, this alternative approach was hardly incorporated into IPE teaching.

14 https://www.aiddata.org/data/aiddatas-global-chinese-development-finance-dataset-version-2-0 (accessed 31 August 2022).

15 https://www.bcg.com/publications/2015/globalization-growth-new-china-playbook-young-affluent-e-savvy-consumers (accessed 31 August 2022).

16 http://blog.oxfordeconomics.com/chinas-consumers-shake-the-retail-world (accessed 31 August 2022).

17 See also: https://signal.supchina.com/all-the-international-brands-that-have-apologized-to-china (accessed 31 August 2022).

18 https://www.reuters.com/article/us-un-patents-idUSKCN2AU0TM (accessed 31 August 2022).

19 While the case is clear for SOEs, Chinese authorities have also been promoting the presence/power of ‘party organizations’ (dang zuzhi) to boost private sector compliance: the share of private enterprises with party organizations increased from 4% to 48.3% between 1993-2018 (including 463/500 top500-firms). https://macropolo.org/party-committees-private-sector-china/?rp=m (accessed 31August 2022).

20 http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2021-11/04/content_5648886.htm (accessed 31 August 2022).

21 For instance, the US Export-Import Bank created the ‘China and Transformational Exports Program’ to use state-subsidized export credits to rival Chinese export finance (https://www.exim.gov/about/special-initiatives/ctep; last accessed 25 May 2022).

22 For instance, the China-led Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and US-led Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF).

23 The absence of China-related content in IPE textbooks makes this task more difficult for introductory undergraduate courses that rely more on textbook teaching than postgraduate courses. However, it is still possible to introduce this in undergraduate sessions, e.g. by including chapters from CPE textbooks (e.g. Clift, Citation2021).

24 Includes globalization/global governance_(105), labor/migration_(59), environment_(54), regional studies_(41), current trends_(36), knowledge/innovation_(21), security_(19), gender_(16), global health_(6), illicit economy_(5).

References

- Allison, G. (2017). Destined for war: Can America and China escape thucydides’s trap? Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Amsden, A. H. (2011). The rise of “the rest”: Challenges to the west from late-industrializing economies. Oxford University Press.

- Balaam, D. N., & Veseth, M. (2018). Introduction to international political economy. Routledge.

- Baumann, H. (2021). Avatars of Eurocentrism in international political economy textbooks: The case of the Middle East and North Africa. Politics. https://doi.org/10.1177/02633957211054739

- Beeson, M. (2018). Geoeconomics with Chinese characteristics: The BRI and China’s evolving grand strategy. Economic and Political Studies, 6(3), 240–256.

- Bhambra, G. K. (2021). Colonial global economy: Towards a theoretical reorientation of political economy. Review of International Political Economy, 28(2), 307–322.

- Bräutigam, D., & Tang, X. (2014). “Going global in groups”: Structural transformation and China’s Special Economic Zones overseas. World Development, 63, 78–91.

- Breslin, S. (2013). China and the global order: Signalling threat or friendship? International Affairs, 89(3), 615–634.

- Chang, H.-J. (2002). Kicking away the ladder: The 'real’ history of free trade. Anthem Press.

- Chen, M. (2020). State actors, market games: Credit guarantees and the funding of China development bank. New Political Economy, 25(3), 453–468.

- Chen, M. (2021). Infrastructure finance, late development, and China’s reshaping of international credit governance. European Journal of International Relations, 27(3), 830–857.

- Chin, G. T., & Gallagher, K. P. (2019). Coordinated credit spaces: The globalization of Chinese development finance. Development and Change, 50(1), 245–274.

- Chin, G. T., Pearson, M. M., & Yong, W. (2013). Introduction – IPE with China’s characteristics. Review of International Political Economy, 20(6), 1145–1164.

- Clift, B. (2021). Comparative political economy: States, markets and global capitalism. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Clift, B.,Kristensen, P. M., &Rosamond, B. (2022). Remembering and forgetting IPE: Disciplinary history as boundary work. Review of International Political Economy, 29(2), 339–370.

- Cohn, T., & Hira, A. (2020). Global political economy: Theory and practice. Routledge.

- Collins, N., & Gottwald, J.-C. (2014). Market creation by Leninist means: The regulation of financial services in the People’s Republic of China. Asian Studies Review, 38(4), 620–638. https://doi.org/10.1080/10357823.2014.964173

- de Carvalho, B., Leira, H., & Hobson, J. M. (2011). The big bangs of IR: The myths that your teachers still tell you about 1648 and 1919. Millennium, 39(3), 735–758.

- de Graaff, N., ten Brink, T., & Parmar, I. (2020). China’s rise in a liberal world order in transition. Review of International Political Economy, 27(2), 191–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2019.1709880

- Ferchen, M. (2013). Whose China model is it anyway? The contentious search for consensus. Review of International Political Economy, 20(2), 390–420.

- Frieden, J. A., Lake, D. A., & Broz, J. L. (2017). International political economy: Perspectives on global power and wealth. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Gabor, D. (2021). The wall street consensus. Development and Change, 52(3), 429–459.

- Germain, R., & Schwartz, H. M. (2017). The political economy of currency internationalisation: The case of the RMB. Review of International Studies, 43(4), 765–787.

- Gilpin, R. (2001). Global political economy: Understanding the international economic order. Princeton University Press.

- Gruin, J. (2019). Communists constructing capitalism: State, market, and the party in China’s financial reform. Manchester University Press.

- Hall, P. A., & Soskice, D. (2001). Varieties of capitalism: The institutional foundations of comparative advantage. Oxford University Press.

- Heilmann, S. (2008). Policy experimentation in China’s economic rise. Studies in Comparative International Development, 43(1), 1–26.

- Helleiner, E. (1996). States and the reemergence of global finance: From bretton woods to the 1990s. Cornell University Press.

- Hernandez, D. (2017). Are “new” donors challenging World Bank conditionality? World Development, 96, 529–549.

- Hopewell, K. (2020). Clash of powers: US-China rivalry in global trade governance. Cambridge University Press.

- Hsueh, R. (2011). China’s regulatory state: A new strategy for globalization. Cornell University Press.

- Ikenberry, G. J. (2018). The end of liberal international order? International Affairs, 94(1), 7–23.

- Johnston, A. I. (2019). China in a world of orders: Rethinking compliance and challenge in Beijing’s international relations. International Security, 44(2), 9–60.

- Kaplan, S. B. (2016). Banking unconditionally: The political economy of Chinese finance in Latin America. Review of International Political Economy, 23(4), 643–676.

- Katzenstein, P. J. (1976). International relations and domestic structures: Foreign economic policies of advanced industrial states. International Organization, 30(1), 1–45.

- Lake, D. A., Martin, L. L., & Risse, T. (2021). Challenges to the liberal order: Reflections on international organization. International Organization, 75(2), 225–257.

- Liu, M., & Tsai, K. S. (2021). Structural power, hegemony, and state capitalism: Limits to China’s global economic power. Politics & Society, 49(2), 235–267. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329220950234

- Malkin, A. (2022). The made in China challenge to US structural power: Industrial policy, intellectual property and multinational corporations. Review of International Political Economy, 29(2), 538–570. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2020.1824930

- Mantz, F. (2019). Decolonizing the IPE syllabus: Eurocentrism and the coloniality of knowledge in international political economy. Review of International Political Economy, 26(6), 1361–1378. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2019.1647870

- Massot, P. (2020). The state of the study of the market in political economy: China’s rise shines light on conceptual shortcomings. Competition & Change, 25(5), 534–560.

- Mawdsley, E. (2012). From recipients to donors: Emerging powers and the changing development. Zed Books.

- McNally, C. A., & Gruin, J. (2017). A novel pathway to power? Contestation and adaptation in China’s internationalization of the RMB. Review of International Political Economy, 24(4), 599–628. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2017.1319400

- Milhaupt, C. J., & Zheng, W. (2015). Beyond ownership: State capitalism and the Chinese firm. The Georgetown Law Journal, 103, 665–722.

- Naughton, B., & Tsai, K. S. (2015). State capitalism, institutional adaptation and the Chinese miracle. Cambridge University Press.

- Nölke, A. (2015). Second image revisited: The domestic sources of China’s foreign economic policies. International Politics, 52(6), 657–665.

- Nölke, A., ten Brink, T., May, C., et al. (2020). State-permeated capitalism in large emerging economies. Routledge.

- Norris, W. J. (2016). Chinese economic statecraft: Commercial actors, grand strategy and state control. Cornell University Press.

- O'Brien, R., & Williams, M. (2020). Global political economy: Evolution and dynamics. Red Globe Press.

- O’Connell, W. D. (2022). Silencing the crowd: China, the NBA, and leveraging market size to export censorship. Review of International Political Economy, 29(4), 1112–1134.

- Oatley, T. (2019). International political economy. Routledge.

- Pape, F., & Petry, J. (2023). East Asia and the politics of global finance: A developmental challenge to the neoliberal consensus? Review of International Political Economy. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2023.2170445

- Petry, J. (2020). Financialization with Chinese characteristics? Exchanges, control and capital markets in authoritarian capitalism. Economy & Society, 49(2), 213–238.

- Petry, J. (2021). Same same, but different: Varieties of capital markets, Chinese state capitalism and the global financial order. Competition & Change, 25(5), 605–630.

- Petry, J. (2022). Beyond ports, roads and railways: Chinese economic statecraft, the Belt and Road Initiative and the politics of financial infrastructures. European Journal of International Relations. https://doi.org/10.1177/13540661221126615

- Ravenhill, J. (2020). Global political economy. Oxford University Press.

- Saidi, M. D., & Wolf, C. (2011). Recalibrating development co-operation. OECD Development Centre Working Papers No. 302.

- Schwartz, H. M. (2018). States versus markets: The emergence of a global economy. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Seabrooke, L., & Young, K. L. (2017). The networks and niches of international political economy. Review of International Political Economy, 24(2), 288–331.

- Shih, V. (2007). Factions and finance in China: Elite conflict and inflation. Cambridge University Press.

- Steinfeld, E. S. (2010). Playing our game: Why China’s rise doesn’t threaten the west. Oxford University Press.

- Strange, S. (1988). States and markets. Pinter.

- ten Brink, T. (2019). China’s capitalism: A paradoxical route to economic prosperity. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Thun, E. (2020). The globalization of production. In: Ravenhill J. (Ed.), Global political economy (pp. 175–196). Oxford University Press.

- Weinhardt, C., & ten Brink, T. (2020). Varieties of contestation: China’s rise and the liberal trade order. Review of International Political Economy, 27(2), 258–280.

- Zeitz, A. O. (2021). Emulate or differentiate? The Review of International Organizations, 16(2), 265–292.

- Zheng, Y., & Huang, Y. (2018). Market in state: The political economy of domination in China. Cambridge University Press.

- Zhu, Z. (2018). Going global 2.0: China’s growing investment in the west and its impact. Asian Perspective, 42(2), 159–182.