Abstract

Since the pioneering role of Kenya’s mobile money service – M-PESA, a consortium of international development agencies, philanthropists, academics, tech corporations and governments – have led an optimistic account of a poverty-eradicating, prosperity-spreading power of financial technology (fintech) in the global South. In contrast, a growing critical IPE literature has demonstrated that the optimistic accounts are broad-brush and misleading. Drawing from recent theorization on digital financialisation and Marxian conceptualization of capital accumulation, this article shifts the focus of the Kenya-centered critical response to Ghana, the second largest mobile money market in Africa. Relying on quantitative data from the Bank of Ghana, and qualitative data from 42 semi-structured interviews, the article provides evidence to show that the mobile money boom in Ghana is underpinned by (1) customer indebtedness from digital microloans, (2) high transaction costs, (3) excessive taxation, and (4) a prevalence of dormant accounts. Collectively, the findings confirm the wider critical literature suggesting that, far from ending poverty and inspiring prosperity, the fintech-financial-inclusion agenda in Africa is opening new frontiers for a sustained and intensified capitalist exploitation of working-class labor in the continent.

Introduction

A new optimism about African economies has emerged following the retreat of the ‘Africa rising’ narrative founded on Gross Domestic Product (GDP) figures. Unlike before, the good news about Africa is not based on the trickle-down power of GDP—it is premised on a postulated poverty-eradicating, prosperity-spreading power of financial technology (fintech). Mobile money (MoMo),Footnote1 a notable fintech, has gained popularity in the continent. From M-PESA in Kenya to MTN MoMo in Ghana, telecommunication companies have expanded their primary focus on communication technologies to include banking services, marking a peculiar phase of finance capitalism described as digital financialisation (Jain & Gabor, Citation2020). To have access to a transaction account, subscribers need a mobile phone and a phone number from the operator. With an account, they can make payments, send money, receive payments, and for some, access microcredit. This service has become commonplace in the continent. Currently, half of the world’s registered MoMo users are in sub-Saharan Africa, with transaction values totaling over $700 billion at the end of 2021 (GSMA, Citation2022).

Two sets of opposing narratives have accompanied this explosive growth of MoMo in Africa and across the global South. On the one hand is an optimistic account given by a consortium of international development agencies, philanthropies and governmentsFootnote2 who have for years promoted a financial inclusion agenda in the global South. Their case is that the MoMo boom in Africa has enabled the financial inclusion (FI) of large sections of the previously unbankedFootnote3 population, which has led to poverty reduction. This view has received validation within mainstream Economics circles (Suri & Jack, Citation2016). On the other hand, there is a critical perspective held by scholars in International Political Economy (IPE). Put in context, these IPE scholars argue that optimistic claims of a fintech-FI-development nexus in the continent and elsewhere in the global South are broad-brush and misleading. They cite the problematic of financial inclusion as a measure (Aitken, Citation2017; Dafe, 2020; Mader, 2015, 2018; Soederberg, Citation2013); gender and spatial inequalities in the digital finance boom (Bernards, Citation2022; Natile, Citation2020;); increasing fintech-engineered surveillance, commodification, monetization and exploitation of customer data (Bernards, Citation2019a; Jain & Gabor, Citation2020); customer indebtedness (Donovan & Park, Citation2019, Citation2022a, Citation2022b; Kusimba, Citation2021); and continued neoliberal capitalist exploitation through fintech (Boamah & Murshid, Citation2019; Bernards, Citation2019b). More troubling accounts of fintech point to its view of poverty as an opportunity for profit making and accumulation (Gabor & Brooks, Citation2017).

This paper follows in line with the critical IPE perspective and at the same time seeks to address two shortfalls in its critique of the fintech-led development narrative in Africa. One, the IPE literature has overly focused on Kenya’s M-PESA, the premier MoMo service, to the neglect of fintechs in other African countries. Two, where attempts have been made to address this (such as Boamah & Murshid, Citation2019), the work has been largely conceptual and less empirical. Accordingly, this paper addresses these two issues by unpacking the political economy of digital financial inclusion in Ghana. Relying on payment systems data from the Bank of Ghana and 42 semi-structured interviews across seven regions in Ghana, the paper provides evidence in support of four criticisms of fintech-led development in Africa. In the case of Ghana, the contradictions to the fintech hype include: (1) customer indebtedness from digital microloans, (2) high transaction costs, and (3) excessive taxation of digital finance, resulting in (4) a prevalence of dormant MoMo accounts. The choice of Ghana is based on its significantly large MoMo market. Ghana has the third highest mobile money usage globally after Kenya and China (Creemers et al., Citation2020), and is the fastest-growing MoMo market in Africa (Geiger et al., Citation2019). It therefore provides a good case study, outside the Kenya-focused narrative, in explaining the contradictions associated with Africa’s fintech boom.

Theoretically, I engage two perspectives on finance capitalism. One, I employ Jain and Gabor’s recent theorization of digital financialisation (Jain & Gabor, Citation2020) to distinguish fintech from traditional forms of finance or banking in Africa. Two, I situate fintech’s FI agenda in Africa within a Marxian theorization of capital accumulation. Traditional notions of finance capitalism require updating to take account of the ‘reorganisation of finance around digital infrastructures’ (Jain & Gabor, Citation2020, p. 813). Jain and Gabor’s conceptualization should be situated in longstanding Marxist theorization of the capitalist mode of accumulation. Reflecting on Marx allows us to sift through the complexity of how digital financial markets ‘obscure yet remain reliant on particular configurations of productive activity’ (Bernards, Citation2019b, p. 1444). I explore this conceptual framework further in section three.

The rest of the paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 explains the fintech-led development agenda, provides the facts on MoMo, and reviews the criticisms raised in the IPE literature. Section 3 analyses digital financialisation and Marx’s circuits of capitals, which serve as the theoretical basis for this study. Section 4, the empirical part, outlines the methodology and discursively presents the findings of the study. Section 5 concludes with implications for IPE research on fintech and development.

Fintech-led development in Africa: the facts and criticisms

The crux of the good news of fintech-led development in Africa can be summarized in three claims that actorsFootnote4 in the global FI agenda make. One, a conceptual claim that access to financial services (that is FI) offers poor people a way out of poverty. Two, a policy claim that where traditional banks and microfinance institutions have failed, fintech (notably MoMo) offers a rapid path to FI. Three, an evidential claim that after more than a decade of fintech boom, more people now have access to transaction accounts and financial services; and that this has reduced poverty levels. Impact analysis within mainstream Economics, such as those by Beck et al. (Citation2015), and Suri and Jack (Citation2016) have provided evidence to support these claims. For instance, in their study of Kenya’s M-PESA, Suri and Jack find that ‘access to mobile money has lifted as many as 194,000 households out of poverty’ (Suri & Jack, Citation2016, p. 1292). What has been the IPE response to these claims? But first of all, what are the facts regarding Africa’s MoMo boom?

The facts

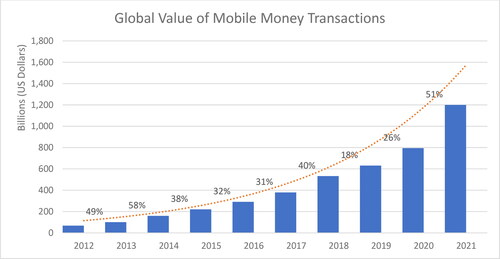

One undisputed part of the claims stated earlier is the significant growth of the number of transaction accounts and the value of overall transactions. Globally, the MoMo industry has grown more than ten times its value in the last decade. Valued at $68 billion in 2012, the annual transaction value reached $1.2 trillion at the end of 2021 (). More than half the decade-long MoMo boom is attributable to Africa (). The evolution of MoMo in Africa is traced to Vodafone Group and Safaricom’s introduction of M-PESA in Kenya on March 6, 2007. Conceived as a development intervention for the huge unbanked, mostly poor population, M-PESA’s subscriber base expanded quickly—a million subscribers in a year, 8.5 million two and half years later, and by 2018, 90% of Kenyans had used the service (Kusimba, Citation2021). Vodafone has since extended its MoMo services to other countries such as Ghana, the DRC, Egypt, Lesotho, Mozambique and Tanzania. At the same time, other telecom companies such as MTN, Airtel and Orange have introduced MoMo to their customers. Together, these services have led the digital finance revolution in the continent. There are now more MoMo services in West Africa (70 services) than in East Africa (57 services) where M-PESA’s pioneering role began (). Notwithstanding that, 55% of the value of transactions in the entire continent comes from East Africa.

Figure 1. Growth in global value of mobile money transactions. Source: Author drawings from GSMA data (GSMA, Citation2021, Citation2022).

Table 1. Distribution of mobile money Statistics in Africa for 2020.

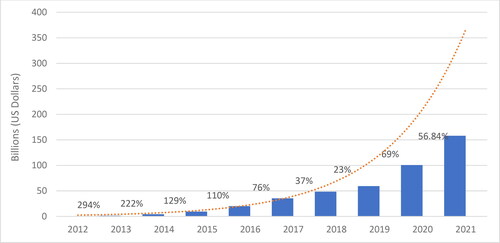

In Ghana, the story has been that of the Kenyan experience. Ghana’s emergence as a MoMo hub is due largely to MTN who introduced the first MoMo service to Ghanaians in 2009. In the last ten years, MoMo has grown faster in Ghana than the global growth rate in transaction values from less than $1 billion in 2012 to about $158 billion at the end of 2021 (). Between 2012 and 2014, transaction values grew more than 200% yearly. By mid-2019, the decade-long exponential growth slowed to about 23% and picked up again with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic that provoked more remote financial transactions. This expansion of the market value of MoMo corresponds with the equally rising numbers of registered users from about 3.7 million registered accounts in 2012 to over 48 million in 2022 (). There is, however, a huge variance between registered accounts and active accounts, an issue which is discussed in Section 4.

Figure 2. Growth in the value of mobile money transactions in Ghana (2012–2021). Source: Bank of Ghana (Citation2020, Citation2021).

Table 2. Mobile money Statistics in Ghana (2012–2022).

The criticisms

Two main concerns dominate the critical response to the optimistic narratives about fintech-FI-development links in the global South, particularly Africa: One, a contestation of the developmental value and methods of FI, and two, a contestation of the reported empirical outcomes of the fintech revolution.

Contesting the value and methods of FI

The works of Dafe (2020) and Soederberg (Citation2013) discounts the conception of FI as a way out of poverty. For Dafe, FI is ambiguous ‘regarding its targets, its relationships to other economic goals, and the role of market’ (Dafe, 2020, p. 506). There is also no clarity about the relationship between FI and other economic goals. The FI agenda is nothing more than an extension of neoliberalism. If there is anything unambiguous, it is that FI ‘serves to legitimate, normalize and consolidate the claims of powerful, transnational capital interests that benefit from finance-led capitalism’ (Soederberg, Citation2013, p. 593). Others (such as Aitken, Citation2017; Bernards, Citation2019a; Gabor & Brooks, Citation2017; Kaminska, Citation2015) go beyond the conceptual value of FI to analyze the methods by which the unbanked are included. One of the postulated benefits of FI is that the poor get access to financial credit since FI mediates the information asymmetry inhibiting lenders’ assessment of the creditworthiness of potential borrowers (see Demirgüç-Kunt et al., Citation2018; World Bank, Citation2022). However, critics such as Aitkens argue against fintech’s reliance on customers’ personal data and psychometric tests for establishing creditworthiness. By analyzing the methods of FI, these critics show that FI through fintech ultimately aims to render the unbanked as visible, legible and calculable subjects of the financial realm and, thus, re-engineer the markets for capitalist profiteering. Consequently, what is promised as FI does not only become financial intrusion (Kaminska, Citation2015), it leads to exploitation by transforming the previously unbanked’s ‘precarious or informal incomes into calculable risks’ (Bernards, Citation2019a, p. 819).

Contesting the outcomes of the fintech revolution

Growing evidence within IPE equally cast doubts on the outcomes reported by the World Bank and its partners in the FI agenda. In this regard, evidence increasingly points to customer/household indebtedness from digital microloans (Donovan & Park, Citation2022a, Citation2022b; Kusimba, Citation2021), and inequalities in the digital finance boom (Bernards, Citation2022; Natile, Citation2020). In their extensive studies of Kenya’s M-PESA story, Kusimba (as well as Donovan and Park) document how subscribers are trapped in debt as they rely on digital microcredit. These studies show that small digital microloans have failed to be the solution to poverty. Borrowers use them for daily survival or just to mitigate their temporal lack of money. A far-reaching concern raised by Donovan and Park is that digitally mediated debt, apart from extracting from people’s limited incomes, effectively makes a claim on their future work. It implies a burden of mortgaging one’s future in order to navigate present financial turbulence.

In light of these criticisms by IPE scholars, this study sought to answer the following questions: (1) Is there any evidence of customer exploitation in the context of Ghana’s fintech boom? (2) If yes, to what extent does such exploitation contradict the good news of fintech-led development? Before considering the evidence, the next section explores the theoretical framework that helps to explain finance-based capitalist exploitation through fintech.

Conceptualizing digital finance as capitalist accumulation in Africa

A key concern in the critical response to the digital FI in the global South has been the attempt to identify the theoretical framework within which to situate the ‘fintech for FI agenda.’ Earlier critiques (Aitken, Citation2017; Gabor & Brooks, Citation2017) analyzed FI as part of wider processes of financialisation. Others drew from science and technology studies, neoliberal logics of marketization (such as Bernards, Citation2019a, Citation2019b), or more strictly inserted fintech into Marxist logics of rentier capitalism (Boamah & Murshid, Citation2019; Donovan & Park, Citation2022b). There is as well a growing body of literature that views fintech as neo-colonial finance (Langley & Leyshon, Citation2022; Timcke, Citation2021). To mediate the theoretical challenge of explaining fintech within conventional notions of finance capitalism as organized around traditional banking systems, Jain and Gabor (Citation2020) proposed a new theoretical framework—digital financialisation. A common theme around these writings is the view of FI as a new frontier for finance capitalist accumulation. Accordingly, I argue for a reconciliation of these conceptualisations. In so doing, we understand two things regarding the fintech for FI agenda. One, fintech is distinct from longstanding forms of finance capitalism in Africa. Two, while distinct from analogue forms of financialisation, fintech feeds into longer-running processes of capitalist exploitation.

How different is digital financialisation from analogue financialisation? For Jain and Gabor (Citation2020), analogue financialisation ‘focuses on the expansion of the financial realm and its increasing dominance over other realms’ (p. 816). It is driven by financial deregulation, innovation and globalization; the main actors often include transnational and domestic financial institutions such as central banks, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. The state plays a dual role in analogue financialisation: First as a promoter, helping to expand the financial sector through monetary and fiscal policies while simultaneously allowing global private players (e.g. fintechs, IFIs, development agencies) significant control of the sector. Secondly, the state acts as a stabilizer, using its central bank monetary tools to manage any bottlenecks in the financial system. Digital financialisation on the other hand, Jain and Gabor continue, is driven by technological innovation built around digital infrastructures. The main actors here are both new and old fintech companies. In this hybrid realm of digital finance, the state employs coercive measures, including demonetization and the integration of citizens’ digital identities to expand the digital-financial sphere. It permits and facilitates fintechs’ collection and monetization of customers’ data through services such as MoMo. The coercive role of the state is motivated by its mutually beneficial bargain with techno-capitalists. While the fintechs want more profits, the state aims to make its citizens more legible and governable through digital surveillance. As digital finance expands, tensions grow between traditional banks and fintechs. This requires the state to act additionally as a mediator in the struggle for control of the financial realm. Effectively, the hybrid process results in the expansion of financial subjects whose lives and data can be commodified in the name of FI, justified by ‘arguments of economies of scale’ (Jain & Gabor, Citation2020, p. 817).

Jain and Gabor’s conception of digital financialisation is clearly manifested in the context of Ghana. Over the last decade and half, global tech firms such as MTN and Vodafone, with varied institutional investors including corporations like BlackRock, J.P Morgan, Norges Bank, Emirati investors and Chinese banks (see online Appendices 2 and 3 for a description of the shareholding of MTN and Vodafone), sought new markets to make profit. Their interests aligned with IFIs and Development Finance Institutions’ (DFIs) shift to private sector-led development financing and that of the Ghanaian government’s goal of expanding telecommunication and financial services to citizens. Consequently, a hybridized financial realm has emerged. MTN and Vodafone have consequently expanded their telecommunication services to include digital finance (MoMo to be precise). The government’s coercive role, as Jain and Gabor posited, is evidenced in Ghana’s aggressive digitization agenda, which requires citizens to integrate all digital identities through mobile sim re-registration. Simultaneously, the MoMo operators have built significant databases of customers. This data has not only been commodified by the fintechs, government is also increasing viewing citizens data both as a means of surveillance and revenue generation. The response of the communications minister (Ursula Owusu-Ekuful) to recent complaints against the government’s coercive digitization captures this reality:

‘If you look at the revenues that these tech giants are generating from managing, analysing and utilizing the data that we freely give them; the Facebook, Google, WhatsApp and all those mega-platforms, then it gives effect to the saying that data is the new oil because if we effectively analyse and utilize it properly, it can generate a lot of revenue for the state for our own development’ (reported in Ghanaweb, Citation2022).

Once capitalist accumulation reaches this point of interest-bearing capital as the means of profiteering, ‘all that we see is the giving out and repayment. Everything that happens in between is obliterated’ (Marx, 1991, p. 471). In the case of customers accessing microloans through fintechs, everything that happens in between as interest-bearing capital circulates, referring to the ‘concrete productive activities that enable the repayment of debts and interests’ (Bernards, Citation2019b, p. 1448). By failing to account for this exploitative nature of digital micro lending, the FI agenda obfuscates the links between the real economy and the financial sector by presenting FI as sufficient in itself. While being silent about the real jobs that provide the money for transactions on digital platforms, the focus of FI has been on low-income earners’ ability to send and receive payments or access financial resources from social networks and micro lending platforms.

In short, my case for reconciling the different conceptualisations of digital finance in Africa is that we capture the novelty of digital financialisation within the context of persisting finance capitalist exploitation in the continent. Consequently, fintech in Africa should be seen from these perspectives—as marking a shift toward digital infrastructures to organize citizens’ engagement with finance (as Jain and Gabor posit) and yet a part and parcel of finance capital accumulation (as in Marx’s conceptualization). In the next section, I focus on providing evidence of what digital financial inclusion has meant for Ghanaians.

The evidence from Ghana

Data and methods

A methodological concern for researchers attempting to explain finance capitalism in the global South is access to financial data. Stefan Ouma noted this when he called for unpacking the grounded operations of finance which is often shrouded in complex and technical jargons (Ouma, Citation2020). But as he wondered, ‘how can we practically produce knowledge about the grounded operations of finance when many of its key players…that ought to be the objects of public scrutiny keep their profiles low and doors closed?’ (Ouma, Citation2020, pp. 16–17). Particularly for fintech is ‘the lack of comprehensive quantitative data on the balance sheets of fintech firms’ (Loannou & Wojcik, Citation2022, p. 59). To provide a comprehensive view of the political economy of fintech in Ghana, in the context of these data constraints, I adopted a mixed methods approach (Jick, Citation1979, cited in Loannou & Wojcik, Citation2022), relying on both quantitative and qualitative data for the analysis.

The data sources relied on include: one, payment systems’ data for the past ten years (2012—2021) gleaned from the Bank of Ghana’s Payments Systems Report for 2020 and its Summary of Economic and Financial Data for 2021; and, two, responses from 42 semi-structured interviews (for reviews on semi-structured interviews, see Dunn, Citation2005; Longhurst, Citation2010). Interviewees comprised 32 MoMo customers and10 MoMo agents– carried out in Greater Accra, Ashanti, Central, Eastern, Northern, Volta, and Upper East regions.

Face-to-face interviews were conducted in Greater Accra, Ashanti, Central, Eastern and Volta Regions during field trips in February and March 2022. Interviews in Northern and Upper East regions were conducted online in April 2022. The interview questions were framed on five issues: (i) ownership of a MoMo account, (ii) usage—type of transaction and frequency of usage, (iii) customers’ assessment of MoMo transaction fees (charges), (iv) access to microloans, purpose for borrowing, and repayment of loans, and (v) customers’ views on the 1.5% electronic transactions’ levy. For in-person interviews, respondents (owning a MoMo account or being an agent) were randomly selected. In the case of online interviews, I relied on my networks in Northern Ghana to suggest potential interviewees who matched the criteria above. Those suggested by my networks in turn suggested others. Interviews were conducted in two languages: English and Twi. Where consent was given, the interviews (mostly lasting 5–10 min) were recorded and transcribed. MoMo operations have recently become deeply politicized in the wake of the 1.5% tax that has met widespread resistance. As such, many declined to be recorded; in those instances, I took notes during our interactions. To protect the identity of interviewees, I used codes for each person interviewed, ranging from N1, N2, up to N42 (see online Appendix 1).

The regions were chosen to reflect the socio-economic dynamics of Southern and Northern Ghana. A notable political-economic concern in Ghana is the North-South development gap. To provide a complete analysis of any socio-economic issue, it is crucial to account for the mostly urbanized, relatively richer South (particularly Greater Accra, Ashanti and Eastern regions) and the mostly rural, relatively poorer Northern Ghana (Northern, Savannah, North-East, Upper East and Upper West regions). The Volta region lies between the rich-South-poor-North dichotomies. Collectively, this sample provides a broader view of MoMo operations across Ghana. While this geographical spread of interviewees is important, it must be noted, as Longhurst (Citation2010) echoing Valentine (Citation2005) observed, that the purpose of interviews is not to be representative as they are usually mistakenly criticized for. Rather, the aim of interviews is to ‘understand how individual people experience and make sense of their own lives’ (Valentine, Citation2005, p. 111). Ultimately, a crucial concern in my interaction with interviewees is a question of reflexivity and positionality (Roulston, Citation2010). As a Ghanaian who has used MoMo for nearly ten years, I recognize that such a financial technology is far more than an inclusion into a formal financial system and that subscribers’ experiences of it can be diverse depending on not just their location but also their socio-economic conditions. Semi-structured interviews allowed for the expression of those varied experiences with MoMo.

Findings

Like most Kenyans who had access to M-PESA, the ease of financial transactions was what attracted many Ghanaians to MoMo services, beginning with MTN in 2009. The number of MoMo accounts expanded rapidly, and so did the services. Over the last ten years, MoMo has gone beyond sending and receiving money to several other services including accessing microcredit. Simultaneously, the hybridization Jain and Gabor posited is actively in place in Ghana—the initial conflict between banks and tech firms has been resolved, ensuring that MoMo accounts are now seamlessly linked to bank accounts. Banks (such as Ecobank, AfB, CBG) even offer the microloans on MoMo platforms such as MTN’s Qwik Loan and Vodafone’s Ready Loan. However, as the euphoria recedes, MoMo subscribers in Ghana are realizing, like their counterparts in Kenya, perhaps too late, that FI comes at a huge cost. Collectively, the findings show, in answer to research questions 1 and 2 in Section 2, that there is significant evidence of customer exploitation accompanying Ghana’s fintech boom, and that this negates the good news of fintech-led development. As Jain and Gabor’s digital financialisation suggests, the confluence of private (global) fintechs’ and Ghanaian government’s interests account for the exploitation of MoMo customers. On the one hand, the fintechs continue to accumulate profits through (1) predatory micro lending which creates customer indebtedness and (2) high transaction fees. On the other hand, government, instead of taxing the profits of the fintechs, shifts its financing needs to citizens through (3) excessive taxation of MoMo. As the state supported fintech exploitation grows and the low-income MoMo users cannot afford transaction fees, loan interests, and digital finance taxes, (4) MoMo transaction accounts increasingly lie dormant. These results are discussed below.

Customer indebtedness from digital microloans

One of the popular financial products offered by MoMo operators is micro lending. To access a loan, subscribers have to be 18 years or older and hold an active MoMo account. MTN Ghana, the largest MoMo operator, runs the Qwik Loan, Ahomka Loan and Xpress Loan. Vodafone Ghana runs its own version called Ready Loan. Applicants can access between ¢50 (about $6) and ¢1000 (about $125) repayable in 30 days, at an average interest of 6.9%. In case of default, loan recipients face three penalties: (1) an instant additional charge of 12.5% on the total outstanding loan amount; (2) a downgrade of their credit score; and (3) disqualification from the loan service for a minimum of three months (see Loanspot, Citation2022; Vodafone Ghana, Citation2022). The ease and speed of access to such loans without collateral has resulted in a rapid growth in the numbers of borrowers. MTN alone disbursed over one million loans in less than a year after the launch of its Qwik Loan in November 2017 (Letshego, Citation2018). However, widespread accounts of loan defaults (see ModernGhana, Citation2019) raise concern over customer indebtedness from microloans. Several MoMo users interviewed admitted to having defaulted at some time (N9, N11, N15, N16, and N34) or were currently in default (N1, N23, N27, N17, N38).

To understand their indebtedness, it is important to consider two things: one, the principal, repayment period and interest rate; and two, what borrowers use the funds to do. It can take several months of regular, faithful borrowing and repayment to reach a credit score that allows borrowers to access any amount close to ¢1000 ($125). Nevertheless, even if we assume that subscribers can borrow ¢1000 from the start, is that significant to start a small-scale business in Ghana (as advocates of FI suggest credit from MoMo are used for)? Retail shops, which are fast becoming rare in crowded urban areas, cost between ¢1000 and ¢20,000 to rent. That is just one part of the cost of doing business. One subscriber observed, ‘they don’t give large amounts when we request for MoMo loan, we only get some small amount which can’t even solve the problem we need the loan for or do business’ (N9). For others, there is no intention from the outset to use the credit for business; it is simply an attempt to manage a precarious economic life marked by low, and/or irregular income streams: ‘the salary cannot even take me to the middle of the month. So I take Qwik Loan to survive until salaries are paid’ (N38).

It is at this point that digital microcredit becomes a temporary measure to ‘buy time’ as Donovan and Park (Citation2022b) found in Kenya. At worse, some borrowers in Ghana hardly ever buy enough time: ‘The time frame at which MoMo loan is to be paid is very limited. The deadline comes and I struggle to get money to pay back the loan’ (N1). Even if N1 took that loan for entrepreneurial reasons, what business in Accra could yield enough profit in 30 days to pay back the loan with 6.9% interest? Even for borrowers (like N20) who choose debt juggling—borrowing from one lender to pay another, it is only a question of when, not if, such debt crisis management reaches its limits. And when it does, the default will cost more than the 12.5% penalty. They will be inundated with calls and texts reminding, perhaps threatening, them to repay. From this point, any cash flows into their MoMo account are instantly deducted by the MoMo operator to offset the loan. Their misery gets complicated: They not only owe, they also need money to survive but no one can send financial assistance through their MoMo account, unless the remittance is enough to mitigate both crises. That is why it has become a norm in Ghana that, ‘…before I (you) send money to anyone through MoMo, I (you) ask them if they owe QwikLoan. Otherwise, I (you) send it and MTN will just take the money’ (N40).

Ultimately, a lot of productive labor, future labor as Donovan and Park suggest in Kenya, is geared toward the repayment of debts. At least, that is for borrowers who have jobs—formal or informal. For the majority of jobless youth, including those of the Unemployed Graduates Association,Footnote5 it could turn into unproductive activities, notably online sports betting. One Qwik Loan defaulter put it as follows:

‘I owe them for so many months. My brother (referring to the interviewer), I am a graduate but as you know there are no opportunities. The only thing is for me to bet, maybe I will win big so I can pay them and stop taking it’ (N17).

High transaction costs

The optimism about MoMo as part of the FI agenda has been built on an inaccurate notion that it lowers the cost of financial transactions. It has become increasingly evident, contrary to this claim, that MoMo transactions are costly, especially for the poor (Anyanzwa, Citation2019). This is largely because MoMo is based on profit motives, requiring that ‘most transactions incur a fee that many poor (people) find difficult to pay, even if they are willing to do so because of the convenience and speed of transfer’ (Donovan Citation2012, p. 70). Because MoMo platforms allow subscribers to send smaller amounts of money than they could or would have done in a traditional bank, it may appear at first that using MoMo is cheap. However, put together, and in the long run, those seemingly ‘small’ fees become unbearable. Ghanaians know this (see Dowuona, Citation2021) and try to avoid the charges in multiple ways. One way is to ask the sender to include withdrawal fees; another trend is to revert to the old ways—send the money through a bank transfer since most banks do not charge customers for transfers and withdrawals. It is not only MoMo users who recognize the exorbitant MoMo fees, some operators do and attempt to take competitive advantage in the market by lowering or waving certain tariffs. Vodafone is a notable example (). That presents subscribers a third option to avoid the fees—they can simply switch to cheaper platforms. However, it does not come that easy with issues of poor network connectivity:

Table 3. Comparison of mobile money fees and tariffs by operators.

‘My problem with mobile money is the network connections and the charges. I was using MTN but due to the connection and charges, that is why I switched to Vodafone and still I am facing the same problem. They should learn to build a strong connection and reduce their charges…’ (N24).

As customers attempt to navigate poor connectivity and cost by holding multiple accounts with different operators, it presents another cost constraint. MoMo interoperability (that is transfers across different MoMo operators) leads to higher tariffs. For instance, while the charge for an MTN MoMo user sending between ¢50 and ¢1000 is 1%, that increases by 50% (1% to 1.50%) if she transfers the same amount to a Vodafone or AirtelTigo account (). For unregistered customers who receive payments from MTN accounts, the cost triples (1% to 3%) or even more (1% to 5%) (). It should be noted that not everyone is concerned about the transactional cost of MoMo:

‘Mobile money is good; it has come to help a lot. Many Ghanaians complain about the charges and other issues. But for me it has been really helpful. I do a lot of transactions, sometimes in a day I can send 1000, 2000, or even 5000 cedis. Can you imagine walking to the bank to do all that, when I have a lot of business going on? I can quickly do it on my phone. So I mostly transfer money from my bank accounts to the MoMo wallet and then use it to do the payments. Besides, dealing with some of these people in the bank can be annoying; with MoMo, I avoid all that’ (N22).

Increased taxation

As the government-private actors’ alliance in digital financialisation unfolds, subscribers’ burden of paying excessive microloan interests and transaction fees is compounded by the recent introduction of a 1.5% electronic transactions levy (e-levy) (see Citi Newsroom, Citation2022). Constrained by its current sovereign debt crisis (see Akolgo, Citation2022), the Ghanaian government sees the e-levy as an easy way to shift its financing needs onto citizens. However, the levy has been widely condemned as a ‘lazy’ and punitive tax (Karombo, Citation2022), particularly within the current context of economic hardships occasioned by COVID-19 and the Russia-Ukraine war. Prior to the parliamentary approval of the e-levy in March 2022, surveys indicated that a majority of Ghanaians, about 81% (Myjoyonline, Citation2022) disapproved of the levy. With a majority of MPs in parliament, government nonetheless passed the e-levy bill into law.

What is the effect of the tax on the cost of MoMo transactions? Take for example an MTN MoMo user sending amounts in the range of ¢200 and ¢2,000. The 1.5% tax is charged on any additional amount after the first ¢100. To understand the effect of the tax on the transaction cost, we calculate the total fees the customer will pay with and without the tax component. The calculations are done using two sets of tariffs: One, the prevailing MTN MoMo tariffs given by the Bank of Ghana (), and two, MTN’s planned tariff reduction (see NewsGhana, Citation2022). With the addition of the 1.5% tax, the customer pays about twice or more, as transfer fees (). The cost quadruples if she transfers more than ¢2000. Even if we consider MTN’s plan to reduce its own tariffs to 0.75% (instead of 1%) for transfers below ¢1000 and a fixed tariff of ¢7.5 (instead of ¢10) for transfers above ¢1000, the negative effect of the tax is still significant. Instead of paying a ¢7.5 fee for sending ¢1000, a customer now pays ¢22.5 due to the tax (). But the problem with e-levy goes beyond one-off deductions:

Table 4. Impact of e-levy on transaction cost.

‘…how can you tax the same money several times? I work, and at the end of the month receive salary, which I have already paid tax and when I send part of it to my mother in the village, you will tax it again. Imagine she wants to send part of it to another relative, and you tax it again…’ (N6).

Effectively, if N6’s chain of transfers continues electronically, the money could be exhausted in the multiple taxation and operator fees. The tax does not apply once they money falls below ¢100 but the operator fees do, until the last cedi. MoMo agents and subscribers (N33 and N12 respectively) are adamant that government tax fintechs and enforce fiscal discipline:

‘If government thinks telcos are making huge money from MoMo, then it should tax their profit not adding to our woes. What have they done with all the money we borrowed from outside Ghana? Because of the tax, we are not getting customers like before; people are withdrawing their monies from MoMo…’ (N33).

‘Look at the huge number of ministers and other government appointees. The huge government expenditure is part of the reason we are in this financial crisis. The ministries and presidency should cut down the unnecessary expenditure before asking us to pay more taxes through MoMo’ (N12).

The prevalence of dormant accounts

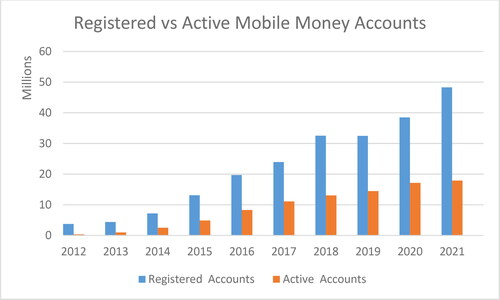

The consequence of the ‘new possibilities for profit generation and governance’ (Jain & Gabor, Citation2020, p. 814) created by digital financialisation in Ghana is the prevalence of dormant transaction accounts. The good news about MoMo in the Global Findex Report is premised on the number of mobile money accounts which are taken to be indicative of FI of the ‘unbanked.’ Such logic presumes that once people create accounts, they automatically use them. However, the data informing such claims show large numbers of inactive accounts. Data from the Bank of Ghana for the last 10 years () show significant variances between registered and active accounts. On average, more than half of registered accounts remain inactive. For instance, only 5 million of the 13 million registered accounts in 2015 were used by account holders. By the end of 2021, registered accounts stood at 48 million but subscribers actively used only 38% (about 18 million). What explains the huge number of dormant accounts? I offer two explanations: one, multiple account registrations. With a population of about 30 million citizens (Ghana Statistical Service, Citation2021), 48 million MoMo accounts imply some people are holding more than one MoMo account. Why do subscribers acquire several accounts? As indicated on the issues of debt and transaction costs, subscribers keep multiple accounts to navigate various challenges: some want to avoid interoperability fees; others want to forestall the potential of network breakdowns with one operator. Moreover, there are those whose aim is to juggle debt across MoMo operators or completely run away from a debt. The second plausible explanation for the dormant accounts is that subscribers have no money or do not regularly earn money:

Figure 3. Registered vs active MM accounts in Ghana (2012–2022). Source: Bank of Ghana (Citation2020, Citation2021, Citation2022).

‘I will say I haven’t used my account in the last three months. I am a mason and we don’t get contracts that often. Sometimes you can get many jobs to build for people and they send you money through MoMo. But there are times you stay two, three or more months and no job comes’ (N36).

The findings contradict fintech-led development

The evidence shown above regarding fintech players, financial institutions, and the Ghanaian government’s ongoing coercive and exploitative creation of new financial subjects in the name of FI cast doubts on any optimism of a fintech-engineered development. The hype about the developmental value of FI obscures the real problems facing poor or low-income unbanked people. The pressing issue for people in Ghana or anywhere else is not so much how to send or receive money as it is about how, when, and where they will get the means (including money) necessary to afford a decent life. The claim of FI offering the unbanked better livelihoods through increased access to credit for social entrepreneurship is not consistent with the Ghanaian evidence. As demonstrated above, microloans are not sufficient to run any profitable business. Worse than that, the loans are given at exploitative interest rates. Suri and Jack (Citation2016) also suggest that holding MoMo accounts means the poor can access financial support from their social networks. In the absence of decent jobs, those accounts in Ghana are predominantly not used. Besides, financial support is only possible, as Bateman et al. (Citation2019) explain, if their networks are wealthy enough to be capable of offering handouts. With poor networks, a MoMo account cannot magically invite financial support. If even social networks send remittances, it has been shown that costly transaction fees and regressive taxes are eroding any finances sent through or received on digital platforms. The grand claims of FI success in the presence of widespread accounts of fintech exploitation shown in Ghana and earlier in Kenya should not come as any surprise. Reliance on modest economic gains to draw sweeping conclusions about development in Africa is not new. Not long ago, global development agencies and western mainstream media (in particular, The Economist, Citation2011) relied on ‘superficial features’ like GDP figures, widespread use of mobile phones, among others to propagate an optimistic narrative of ‘Africa rising’ (Taylor, Citation2016). It was later shown to be empty rhetoric (Obeng-Odoom, Citation2015) and rightly so because the euphoria was a sharp contrast to the realities on the ground (Akolgo, Citation2018). The present stage of optimism built around FI is no different.

Conclusion

In this article, I have analyzed the proliferation of mobile money services in Ghana within the broader development agenda of fintech-engineered financial inclusion. Like the wider critical literature on financial inclusion, the point is not to argue that providing technologies that facilitate convenient and speedy transactions is inherently bad. Far from renouncing technology, the attempt has been to analyze the political-economic logic underpinning the turn to technology for financial inclusion. In Ghana, fintech has improved the ease and speed of financial transactions. However, the profit motive informing its creation has exposed subscribers to debt and exorbitant transaction costs. These are worsened by the Ghanaian government’s introduction of a 1.5% electronic levy, a regressive tax as it disproportionately burdens the poor. These outcomes are not accidental—the rollout of mobile money in Ghana should be viewed as part of global processes of digital finance capitalism intended to sustain, open new frontiers for, and intensify capitalist accumulation in the global South. Capitalism’s long history has been characterized by its ‘unlimited flexibility’ and ‘capacity for change and adaptation’ (Braudel, 1982, cited in Arrighi, Citation2010, p. 4). The turn to technology, pacified with claims of inclusion, is just one way capitalism is adapting to make ‘informal labor visible, decode wealth, and accumulate for the sake of accumulation’ (Boamah & Murshid, Citation2019, p. 254). Looking forward in Ghana and beyond, it is crucial for IPE scholarship on fintech to consider the macro-level implications of digital financial inclusion for the longstanding financial subordination of African economies. As foreign fintechs with shareholders located in the global North expand, the foreign control of the African financial system (as earlier posited by (Nkrumah, Citation1965) and recently affirmed in (Alami et al., Citation2022) gets entrenched. Therefore, macro-level analyses of how fintech contributes to foreign control of the domestic financial sector will provide a broader understanding of the financial inclusion agenda. In this regard, Jain and Gabor’s conceptualization of digital financialisation lends itself as an important theoretical framework. It offers a comprehensive approach to explaining finance capitalism in the global South, accounting for the roles of digital technologies, global actors and domestic governments.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (458.2 KB)Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Professors Franklin Obeng-Odoom, Kai Koddenbrock, and Stefan Ouma for their comments on the initial draft of this paper, as well the editors at RIPE and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. I will also like Enock Kesse for his field assistance during the interviews in Ghana.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Isaac Abotebuno Akolgo

Isaac Abotebuno Akolgo is a Research Associate in the Monetary and Economic Sovereignty research group at the Africa Multiple Cluster of Excellence, University of Bayreuth. As a heterodox economist, he currently researches the Political Economy of Money and Finance in Ghana, with a focus on banks, financial technologies, and debt.

Notes

1 In Ghana, MoMo is a term used by MTN Ghana but which is now used loosely to refer to all mobile money services.

2 The World Bank, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Alliance for Financial Inclusion, the G20.

3 Adults who have no access to formal banking services.

4 See footnote 1.

5 The Unemployed Graduates Association of Ghana was formed in 2011 as a response to the growing numbers of jobless university graduates.

References

- Aitken, R. (2017). All data is credit data: Constituting the unbanked. Competition & Change, 21(4), 274–300. https://doi.org/10.1177/1024529417712830

- Akolgo, I. A. (2018). Afro-euphoria: Is Ghana’s economy an exception to the growth paradox? Review of African Political Economy, 45(155), 146–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/03056244.2017.1389716

- Akolgo, I. A. (2022). Collapsing banks and the cost of finance capitalism in Ghana. Review of African Political Economy, 49(174), 624–633. https://doi.org/10.1080/03056244.2022.2044300

- Alami, I., Alves, C., Bonizzi, B., Kaltenbrunner, A., Koddenbrock, K., Kvangraven, I., & Powell, J. (2022). International financial subordination: A critical research agenda. Review of International Political Economy, 1–27.https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2022.2098359

- Anyanzwa, J. (2019). Mobile money transfer more costly for the poor. The EastAfrican. Retrieved June 18, 2022. https://bit.ly/3Oi09fj

- Arrighi, G. (2010). The long twentieth century: Money, power and the origins of our times. Verso.

- B&FT. (2020). BoG must sanction banks for poor customer service – Dr. Atuahene. Retrieved June 18, 2022, from https://thebftonline.com/2020/06/15/bog-must-sanction-banks-for-poor-customer-service-dr-atuahene/

- Bank of Ghana. (2020). Payment systems oversight annual report, 2020. Accra: Bank of Ghana. Retrieved March 2, 2022. https://www.bog.gov.gh/news/payment-systems-oversight-annual-report-2020/

- Bank of Ghana. (2021). Summary of economic and financial data November 2021. Bank of Ghana. Retrieved May 1, 2022, from https://www.bog.gov.gh/econ_fin_data/summary-of-economic-and-financial-data-november-2021/

- Bank of Ghana. (2022). Summary of economic and financial data - March 2022. Bank of Ghana. Retrieved April 18, from https://www.bog.gov.gh/econ_fin_data/summary-of-economic-and-financial-data-march-2022/

- Bateman, M., Duvendack, M., & Loubere, N. (2019). Is fin-tech the new panacea for poverty alleviation and local development? Contesting Suri and Jack’s M-Pesa findings published in Science. Review of African Political Economy, 46(161), 480–495. https://doi.org/10.1080/03056244.2019.1614552

- Beck, T., Haki, P., Ravindra, R., & Burak, R. U. (2015). Mobile money, trade credit and economic development: Theory and evidence. Discussion Paper No. 2015-023. Tilburg, Netherlands: Tilburg University.

- Bernards, N. (2019a). The poverty of fintech? Psychometrics, credit infrastructures, and the limits of financialization. Review of International Political Economy, 26(5), 815–838. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2019.1597753

- Bernards, N. (2019b). Tracing mutations of neoliberal development governance: ‘Fintech’, failure and the politics of marketization. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 51(7), 1442–1459. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X19862576

- Bernards, N. (2022). Colonial financial infrastructures and Kenya’s uneven fintech boom. Antipode, 54(3), 708–728. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12810

- Boamah, E. F., & Murshid, N. S. (2019). Techno-market fix? Decoding wealth through mobile money in the global South. Geoforum, 106, 253–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.08.012

- Citi Newsroom. (2022). 1.5% E-levy takes effect today. Retrieved May 10, from https://citinewsroom.com/2022/05/1-5-e-levy-takes-effect-today/

- Creemers, T., Murugavel, T., Boutet, F., Omary, O., & Oikawa, T. (2020). Five strategies for mobile-payment banking in Africa, Boston Consulting Group. https://www.bcg.com/publications/2020/five-strategies-for-mobile-payment-banking-in-africa

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A., Klapper, L., Singer, D., Ansar, S., & Hess, J. (2018). The Global Findex Database 2017: Measuring financial inclusion and the fintech revolution. World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-1259-0

- Dowuona, S. (2021). Mobile Money – the chief driver of digital economy – Part 2. Business and Financial Times. Retrieved May 18, 2022, from https://bit.ly/3Oh06jV

- Donovan, K. P., & Park, E. (2019). Perpetual debt in the Silicon Savannah. Boston Review. Retrieved December 29, 2021. https://bostonreview.net/articles/kevin-p-donovan-emma-park-tk/

- Donovan, K. P., & Park, E. (2022a). Algorithmic intimacy: The data economy of predatory inclusion in Kenya. Social Anthropology/Anthropologie Sociale, 30(2), 120–139. https://doi.org/10.3167/saas.2022.300208

- Donovan, K. P., & Park, E. (2022b). Knowledge/seizure: Debt and data in Kenya’s zero balance economy. Antipode, 54(4), 1063–1085. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12815

- Dunn, K. (2005). Interviewing. In I. Hay (Ed.), Qualitative research methods in human geography (2nd ed., pp. 79–105). Oxford University Press.

- Gabor, D., & Brooks, S. (2017). The digital revolution in financial inclusion: International Development in the fintech era. New Political Economy, 22(4), 423–436. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2017.1259298

- Geiger, M. T., Kwakye, K. G., Vicente, C. L., Wiafe, B. M., & Boakye Adjei, N. Y. (2019). Fourth Ghana economic update: Enhancing financial inclusion - Africa region (English). Ghana Economic Update, no. 4. World Bank.

- Ghana Statistical Service. (2021). Ghana 2021 population and housing census volume 1 prelimnary report. Ghana Statistical Service.

- Ghanaweb. (2022). Data is the new oil, it can generate a lot of revenue for the state - Ursula Owusu-Ekuful. Rerieved December 10, 2022, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YnH7V5iSkoY

- GSMA. (2021). State of the industry report on mobile money 2021. GSMA Association.

- GSMA. (2022). State of the industry report on mobile money 2022. GSMA Association.

- Jain, S., & Gabor, D. (2020). The rise of digital financialisation: The case of India. New Political Economy, 25(5), 813–828. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2019.1708879

- Jick, T. (1979). Mixing qualitative and quantitative methods: Triangulation in action. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24(4), 602–611. https://doi.org/10.2307/2392366

- Kaminska, I. (2015). When financial inclusion stands for financial intrusion. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/fd319ea7-e0fd-32cf-a50a-776ae22f0f0c

- Karombo, T. (2022). “It’s a lazy tax”: Why African governments’ obsession with mobile money could backfire, Rest of the World. Retrieved January 8, from https://restofworld.org/2022/how-mobile-money-became-the-new-cash-cow-for-african-governments-but-at-a-cost/

- Kusimba, S. (2021). Reimagining money: Kenya in the Digital Finance Revolution. Stanford University Press.

- Kwakofi, E. (2018). Informal workers earn GH¢150 monthly. Citinewsroom. Retrieved June 18, 2022. https://bit.ly/3OyDmvm

- Langley, P., & Leyshon, A. (2022). Neo-colonial credit: FinTech platforms in Africa. Journal of Cultural Economy, 15(4), 401–415. https://doi.org/10.1080/17530350.2022.2028652

- Letshego. (2018). afb Ghana celebrates one million qwikloan customers and commences rebrand to Letshego. Retrieved June 17, 2022, from https://www.letshego.com/afb-ghana-celebrates-millionth-qwikloan-customer

- Loannou, S., & Wojcik, D. (2022). The limits to FinTech unveiled by the financial geography of Latin America. Geoforum, 128, 57–67.

- Loanspot. (2022). MTN QwikLoans in Ghana – How to get up to GHS1000 in 1 minute. https://loanspot.io/gh/mtn-qwikloans-in-ghana/

- Longhurst, R. (2010). Semi-structured interviews and focus groups. In N. Clifford, S. French, & G. Valentine (Eds.), Key methods in geography. SAGE.

- ModernGhana. (2019). We have no evidence our loan defaulters are NABCO trainees -MTN mobile money. Retrieved June 17, 2022, from https://www.modernghana.com/news/932463/we-have-no-evidence-our-loan-defaulters-are-nabco-trainees-.html

- Myjoyonline. (2022). 81.6% of Ghanaians want E-Levy cancelled – Survey. Retrieved April 20, 2022, from https://myjoyonline.com/81-6-of-ghanaians-want-e-levy-cancelled-survey/

- Natile, S. (2020). The exclusionary politics of digital financial inclusion: Mobile money, gendered walls. Routledge.

- NewsGhana. (2022). E-Levy implementation: MTN to cap MoMo service fee at GH¢7.5. Retrieved May 24, 2022, from https://newsghana.com.gh/e-levy-implementation-mtn-to-cap-momo-service-fee-at-ghs7-5/

- Nkrumah, K. (1965). Neo-colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism. Panaf Books.

- Obeng-Odoom, F. (2015). Africa: On the rise, but to where? Forum for Social Economics, 44(3), 234–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/07360932.2014.955040

- Ouma, S. (2020). Farming as financial asset: Global finance and the making of institutional landscapes. Agenda Publishing.

- Roulston, K. (2010). Considering quality in qualitative interviewing. Qualitative Research, 10(2), 199–228. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794109356739

- Soederberg, S. (2013). Universalising financial inclusion and the securitisation of development. Third World Quarterly, 34(4), 593–612. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2013.786285

- Suri, T., & Jack, W. (2016). The long-run poverty and gender impacts of mobile money. Science (New York, N.Y.), 354(6317), 1288–1292. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aah5309

- Taylor, I. (2016). Dependency redux: Why Africa is not rising. Review of African Political Economy, 43(147), 8–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/03056244.2015.1084911

- The Economist. (2011). Africa rising. Retrieved May 1, 2022, from https://www.economist.com/leaders/2011/12/03/africa-rising#footnote1

- Timcke, S. (2021). Kwame Nkrumah and imperialist finance in Africa today. Retrieved April 20, 2022, from https://roape.net/2021/07/06/kwame-nkrumah-and-imperialist-finance-in-africa-today/

- Valentine, G. (2005). Tell me about using interviews as a research methodology. In R. Flowerdew & D. Martin (Eds.), Methods in human geography: A guide for students doing a research project (2nd ed., pp. 110–127). Addison Wesley Longman.

- Vodafone Ghana. (2022). Ready loan. Retrieved May 18, 2022. https://support.vodafone.com.gh/help/ready-loan/

- World Bank. (2022). World development report 2022: Finance for an equitable recovery. World Bank Group. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-1730-4