Abstract

This article theorizes path-dependent changes in the institutional architecture of the nuclear nonproliferation regime complex; it analyses the effects of different regime-complex structures on institutional contestation and policy adjustment. I first offer a general theory of how the preexisting institutional structures of international regime complexes (IRCs) facilitate and constrain subsequent institutional developments in ways that make IRCs prone to endogenous, path-dependent change. Next, I illustrate how strategies of regime shifting and rival regime creation in the nuclear nonproliferation complex have triggered path-dependent ‘reactive sequencing’, resulting in growing institutional fragmentation. To illustrate endogenous dynamics of IRC evolution, I examine the nuclear nonproliferation complex at three ‘critical junctures’: The mid-1970s, the end of the Cold War, and the early-2000s. During each period, exogenous proliferation shocks interacted with pre-existing institutional structures to produce specific patterns of contestation which set in motion a reactive sequence of growing institutional fragmentation. My argument has relevance for global economic governance broadly and for the growing IPE literature which explores reactive sequencing and institutional decay in global governance institutions.

Introduction

‘I will be blunt. Key components of the international arms control architecture are collapsing’ (UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres, Citation2019).Footnote1

Many areas of global governance feature growing institutional density: There are more actors, more rules and norms, and growing overlap between them. Yet, the structures of ‘international regime complexes’ (Raustiala & Victor, Citation2004) differ widely: The number and kinds of institutions governing an issue-area; the degree of overlap between them; the extent to which overlapping rules conflict or cohere; and the presence of clear authority relations vary from one regime complex to the next—and within complexes over time. What explains such variation? And what are the consequences for substantive governance outcomes?

This article explores these questions in the context of the international regime complex governing nuclear nonproliferation. Many observers point to a recent ‘unravelling’ of institutional frameworks governing nuclear nonproliferation, some warning that ‘we are dangerously close to a world without [nuclear] arms control agreements, which would increase the risk of nuclear use’ (Howell, 2019, p. 5; Knopf, Citation2021; Tannenwald, Citation2020). This unravelling—which manifests in a proliferation of incoherent rules and lessened policy adjustment—has been partly fueled by cooling relations between the former superpowers, by the rise of new global powers, and by technological developments which have rocked the foundations of existing nuclear agreements—that is, by factors exogenous to existing non-proliferation institutions. However, I argue, institutional unravelling is also a product of the structure of inter-institutional relations in the nuclear non-proliferation regime complex (hereafter the ‘NRC’) and hence endogenous to institutional frameworks.

To support this argument, I explain how pre-existing institutional structures in the NRC have channelled growing dissatisfaction by states towards specific modes of contestation, and how this in turn has impacted further institution-building in ways that have triggered a negative spiral of increasing forum-shopping and rival regime-creation, ushering in growing rule conflict. The result has been a gradual decrease in system stability, which I define as the ability of a regime complex to adapt to exogenous or endogenous disruptions by re-establishing clear inter-institutional authority relations and task-differentiation, and thereby reconcile conflicting rules and authority claims in ways that enable effective cooperation.

The central argument of this article is that existing institutional ‘architectures’ of international regime complexes (hereafter IRCs) facilitate and constrain subsequent institutional developments in ways that make such complexes subject to endogenous, path-dependent change. Recent work in international political economy (IPE) increasingly views institutional changes as the result of forces endogenous to institutions (Peinert, Citation2018). For example, scholars working from a Historical Institutionalist perspective have examined how initial institutional choices shape subsequent actions (Fioretos, Citation2017; Mahoney & Thelen, Citation2010; Rixen et al., Citation2016)—including further institutional choices (Jupille et al., Citation2013). Processes of path-dependence have conventionally been modelled as self-reinforcing sequences in which increasing returns, learning, and legitimation effects mean that institutional equilibria become increasingly entrenched over time (Pierson, 2004; Rixen & Viola, Citation2015; Jupille & Caporaso, Citation2022). Recently, however, scholars have drawn attention to negative feedback loops in the form of ‘reactive sequences’ (Hanrieder & Zürn, Citation2017; Mahoney, Citation2000) which can lead institutions to become self-undermining (Bunte et al., Citation2022; Greif & Laitin, Citation2004). But while temporal feedback loops—whether self-reinforcing or self-undermining—have been theorized in the context of singular institutions, these dynamics have rarely been explored in the context of the interaction of multiple, overlapping institutions governing similar issues. Hence, the growing IPE scholarship focused on temporality and institutional feedback dynamics has yet to clarify how such dynamics play out in the context of IRCs.

On the other hand, the burgeoning International Relations literature on international regime complexity has so far paid limited attention to temporality. Early studies of IRCs were largely static, examining the effects of institutional overlap on state behaviour at specific moments in time. Later scholarship has adopted a more dynamic approach, focusing on gradual processes of institutional change at the system-level of regime complexes. Drawing on sociological models of complex adaptive systems, scholars have theorized IRCs as ‘self-organizing’ systems that tend to order relations among constituent institutions through voluntary task-differentiation (Eilstrup-Sangiovanni, Citation2022; Gehring & Faude, Citation2014; Oberthür & Stokke, Citation2011) or ‘spontaneous deference’ (Pratt, Citation2018). The general claim of these studies is that IRCs tend to evolve towards an ‘integrated’ state in which inter-institutional relations are marked by growing hierarchy, task-differentiation, and rule coherence. This is also the expectation outlined in the Introduction to this special issue (Henning & Pratt, Citation2023, p. 22).

While this article does not per se disagree with the conjectures of these previous studies, I argue that—under certain circumstances—the opposite can also happen. Specifically, an initial lack of hierarchy or functional task-differentiation among overlapping institutions may invite dissatisfied actors to pursue opportunistic regime-shifting (Raustiala & Victor, Citation2004; Helfer, Citation2009), or to create rival institutions that better suit their interests (Morse & Keohane, Citation2014). In turn, this may further erode hierarchical authority relations, thereby inviting further regime-shifting, rival creation and so on. Absent countervailing forces (such as spontaneous deference or voluntary task-differentiation) this may trigger a negative feedback loop in which an initial unravelling of established authority relations and task-divisions begets further institutional fragmentation. As this process evolves, opportunities for institutional ‘re-integration’ grow steadily dimmer due to growing transaction costs and reduced incentives for actors to compromise within individual existing institutions. Although regime-complex evolution is clearly influenced by how actors respond to growing institutional overlap and rule conflict (agency matters), IRCs may thus be subject to negative feedback dynamics which become progressively harder to restrain or reverse over time. This has been the case in the NRC which started out as relatively integrated but has grown increasingly ‘fragmented’ over time.

Nuclear non-proliferation offers a fertile domain for studying the path-dependent evolution of IRCs for three reasons. First, the number of international institutions governing nuclear non-proliferation has grown exponentially during the past five decades—from a small handful in the 1970s to more than 50 today—yielding significant variation in the independent variables under scrutiny (chiefly, institutional overlap, inter-institutional authority relations, and functional task-differentiation).

Second, high stakes of cooperation imply that states are often hypersensitive to the specific terms of cooperation in the nuclear domain. In turn, this leads to a relatively clear articulation of state preferences over institutional design, and—presumably-a high degree of rationality (understood as informed, goal-directed action) when it comes to choosing among institutional alternatives, whether new or existing. The implication is that individual instances of institutional overlap and rule conflict are less likely to reflect myopic policymaking (Mallard, Citation2014, p. 448), or be a function of institutional expansion by autonomous bureaucratic agents (Raustiala & Victor, Citation2004, p. 301). The benefit, in analytical terms, is to provide a clear view of how ‘local’ deliberate strategic choices can produce an overall regime complex structure that is both unintended and undesired, but that is difficult to ‘re-design’ despite high stakes for states.

Third, the evolution of the NRC is not merely of theoretical but also of substantive importance. Nuclear trade, energy, and, for some states, nuclear weaponry, is a core function of the modern nation state. Nuclear safeguards critically influence not only international security, but also economic growth, stability of energy markets, and sustainable development—especially given the growing importance of nuclear energy for developing energy markets, and for decarbonization. The rapid unravelling of institutions facilitating the development and sharing of peaceful nuclear technology is thus a major concern for global policymakers. At a time when experts describe the risk of nuclear weapon use as higher than at any time since the Cold WarFootnote2, and when nuclear energy holds the potential to alleviate existential risks from climate change, the stakes of halting or reversing deleterious institutional fragmentation in the nuclear domain could hardly be higher.

The article is organized as follows. Section 1 outlines the concepts central to my analysis. Section 2 derives theoretical expectations regarding the path-dependent evolution of IRCs. Section 3 examines institutional changes in the NRC during three historical periods, each defined by an exogenous shock which sparked a subsequent process of institutional change: The mid-1970s (India’s nuclear test); the end of the Cold War; and the early-2000s (serial proliferation shocks and threats of nuclear terrorism). At each stage, I show how states’ reactions to exogenous stimuli were shaped by pre-existing inter-institutional structures in ways that encouraged further institutional fragmentation. Over time, endogenous constraints have multiplied, limiting states’ ability to respond to external shocks, and reducing system stability. The concluding section generalizes the argument to other domains of global governance.

Concepts and terminology

IRC structures can vary along many dimensions—e.g. the number and diversity of constituent institutions, the density of institutional overlaps, etc. (Eilstrup-Sangiovanni & Westerwinter, Citation2022). In what follows, I focus on two dimensions of variation highlighted in the Introduction to this special issue: Hierarchical authority relations (or ‘hierarchy’) and institutional differentiation. Hierarchy captures the extent to which some institutions acknowledge (implicitly or explicitly) the right of others to craft definitive rules, organize common projects, or otherwise define the terms of inter-institutional cooperation. In formal terms, inter-institutional hierarchy may arise from ‘nesting’ of narrower institutions within broader ones (Aggarwal, Citation1998), or from the separation of ‘primary’ institutions endowed with extensive rule-making powers and ‘secondary’ institutions tasked with downstream implementation (Amable, Citation2003, p. 67). Hierarchical authority relations may also be informal and emergent, arising from dynamics of spontaneous deference (Pratt, Citation2018), whereby some institutional actors tacitly accept the rightful rule of others (e.g. by referencing their rules or routinely deferring to their decisions), or whereby common principals routinely favor some institutions over others. Inter-institutional hierarchy is conceptually distinct from asymmetrical power and influence among member states, which is captured through formal and informal intra-institutional power (Henning & Pratt, Citation2023). Nevertheless, the two are closely entwined. For example, powerful states may shape inter-institutional authority relations by unilaterally enforcing some rules and not others, or by pressuring institutional agents to defer to one another. Both intra- and inter-institutional hierarchies thus tend to mirror power balances among states and may come under pressure as these balances change.

‘Differentiation’ denotes the degree to which institutions in an IRC differ in terms of the functions they perform either geographically (in terms of the physical scope of activities) or functionally (in terms of specific tasks or decision-making procedures).

In what follows, I refer to IRCs that feature both hierarchical authority relations and institutional differentiation as ‘integrated’, whereas complexes in which separate institutions vie for authority and compete to fulfill similar functions are ‘fragmented’. Neither term is binary; IRCs fall on a spectrum from tightly integrated, to highly fragmented. The distinction between integrated/fragmented IRCs underscores that institutional overlap is not synonymous with fragmentation. An IRC that features significant overlap in institutional membership and mandates may be considered integrated insofar as inter-institutional authority relations are clear and transparent (Kim & Mackey, Citation2014; Eilstrup-Sangiovanni, Citation2022), and separate institutions offer complementary rather than conflicting rules and policy instruments (Oberthür & Stokke, Citation2011; Keohane & Victor, Citation2011, p. 8). It may be considered ‘stable’ insofar as institutional actors tend to re-establish hierarchical authority relations and task-differentiation (whether deliberately or spontanously) in the wake of exogenous or endogenous perturbations to either dimension of an IRC’s architecture.

Effects of regime complex architectures

What is the relationship between regime-complex architectures and substantive policy outcomes? To theorize the consequences of variation in IRC structures, the Introduction to this special issue specifies two outcome variables: Policy adjustment captures whether states adjust their behaviour and policies to comply with international agreements. Contestation refers to how actors that grow dissatisfied with institutional arrangements challenge these through strategies of forum-shopping, regime-shifting and rival regime creation. To these standard forms of contestation, I add ‘blocking’ which involves the strategic use of institutional veto-power to increase pressure for re-negotiation of existing agreements or extract rents (see also Hofmann, Citation2019). Blocking as a contestation strategy is frequently used by states that lack power to engage in regime-shifting or rival regime creation.

Hierarchical authority relations are hypothesized to constrain contestation through regime-shifting or rival regime creation since peripheral institutions acknowledge the authority of a more central governance body. In turn, this leads to more coherent rules which promote policy adjustment by preventing opportunistic forum-shopping and reducing uncertainty over international obligations (Henning & Pratt, Citation2023). Differentiated institutions likewise reduce rule conflict and limit contestation through forum-shopping (since separate institutions focus on distinct problems), but not necessarily through rival creation or blocking. Conversely, undifferentiated institutions can be expected to increase rule conflict and encourage forum-shopping since similar functions can be served by different institutions (Henning & Pratt, Citation2023, p. 13; see also Helfer, Citation2009; Drezner, Citation2009; Benvinisti & Downs, Citation2007). Overall, IRCs in which institutions are hierarchically organized and clearly differentiated (integrated IRCs) tend to feature lower levels of institutional contestation and higher levels of policy adjustment than IRCs in which institutions are non-hierarchically arranged and undifferentiated (fragmented IRCs).

Theory: the dynamic evolution of regime complexes

This section presents theoretical expectations regarding how system-level institutional architectures influence IRC evolution. Like most extant literature, the theoretical framework guiding this special issue offers a relatively static view of how different regime-complex architectures influence actors’ downstream choices regarding policy adjustment and institutional selection (e.g. Helfer, Citation2009; Jupille et al., Citation2013; Raustialla & Victor, Citation2004). But while some institutional choices may be ‘discrete’ insofar as actors exploit conflicting rules to shirk specific obligations, many such choices—from regime-shifting to rival creation and blocking—are inherently forward-looking and institutional in that they aim to permanently alter structures of cooperation in ways that modify existing payoff distributions (Morse & Keohane, Citation2014). As opposed to the everyday policy choices that govern standard institutional rulemaking and compliance, these strategies therefore feed back onto a regime complex’s architecture and shape emerging patterns of hierarchy and differentiation. Institutional effects become causes.

Consider, for example, that whenever contestation manifests in regime-shifting or rival regime creation, this will tend to dilute the authority of established ‘focal’ institutions (Drezner, Citation2009, p. 66), thereby loosening constraints on further venue shifting or rival creation. Outcomes of lessened policy adjustment may similarly feed back onto regime-complex architectures insofar as widespread noncompliance may generate demands for institutional change which—if blocked—may prompt regime-shifting or rival creation. Once multiple conflicting rules and decision-making venues exist, this diminishes prospects for institutional re-integration (i.e. re-establishing hierarchical authority relations and task-differentiation) through reform, since opportunities for venue shifting reduces incentives for actors to compromise within individual institutions, and because institutional fragmentation limits opportunities for using issue-linkage or ‘bundling’ to achieve consensus on reform. More broadly, the proliferation of rival authority claims and rulesets increases the transaction costs that states will incur in seeking to reintegrate the resulting legal order (Benvinisti & Downs, Citation2007, p. 595).

Of course, ‘integrative’ dynamics may likewise be self-reinforcing. Updating or expanding the rules of a focal institution will tend to augment its authority, which may in turn pre-empt rival creation or venue shifting and strengthen policy adjustment (I will say more on this below).

These feedback loops between initial institutional choices, the effects of such choices, and further institutional developments suggest that IRCs are prone to dynamic, path-dependent change. Specifically, they suggest the possibility of ‘reactive sequences’ whereby complexes grow increasingly fragmented over time. As defined by Mahoney, reactive sequences involve ‘chains of temporally ordered and causally connected events’ in which each event is both a reaction to earlier events and a cause of subsequent events (Mahoney, Citation2000). As in other path-dependent sequences, final outcomes are strongly conditioned by early events in a sequence. But whereas self-reinforcing sequences involve reproductive processes that perpetuate initial institutional equilibria, reactive sequences are marked by backlash processes that transform and perhaps reverse the initial conditions that gave rise to them (Mahoney, Citation2000, p. 527). As such, reactive sequences can lead institutions—or, in our case, institutional complexes—to become self-undermining (Greif & Laitin, Citation2004).

Modelling institutional change as a dynamic process poses several analytical challenges. As Büthe (Citation2002, p. 485) notes, in a static model, adding causal feedback loops from the dependent outcome to explanatory variables risks circular reasoning, making it impossible to determine what causes what. The sequential element of temporality overcomes this problem ‘by allowing us to model causal feedback loops from the explanandum at one point in time to the explanatory variables at a later point in time’ (op.cit.). A second challenge, however, is to determine what marks the beginning and end of a path-dependent sequence. Here I draw on the concept of ‘critical junctures’ that launch institutions along different developmental paths (Jupille & Caporaso, Citation2022). Critical junctures are generally conceived as moments where dramatic institutional change becomes possible due to ‘normal’ structural and institutional constraints on action being relaxed (Capoccia & Kelemen, Citation2007, p. 341). Critical junctures may be a response to contingent events (e.g. exogenous shocks) that lie outside the explanatory core of a theory (Capoccia & Kelemen, Citation2007, p. 350; Mahoney & Thelen, Citation2010), or they may be a reaction to underlying cleavages that are aggravated at a particular moment to produce a crisis (Collier & Collier, Citation1991, p. 30; Smetana & O’Mahoney, Citation2022, p. 355). What makes these junctures critical is that once a particular institutional arrangement is chosen from among a range of alternatives, this triggers a path-dependent process whereby ‘it becomes progressively more difficult to return to the initial point when multiple alternatives were still available’ (Mahoney, Citation2000, p. 512).

Importantly, whilst they imply path-dependence, critical junctures do not imply a pre-determined journey towards a fixed endpoint. As Solingen and Wan (Citation2016, p. 8) observe, ‘new critical junctures and learning can provide mechanisms for change even in processes heavily burdened with path-dependence’. This suggests that temporal sequences can be conceptually and analytically demarcated by critical junctures which define their beginning and end. Following this logic, my model of IRC-evolution takes as its starting point a critical juncture in the form of an exogenous shock that eases ordinary political and institutional constraints on action. This allows for agency to shape outcomes which diverge from the past, and which are locked in after the conditions permitting rapid change disappear and the juncture comes to an end (Soifer, Citation2012). Critical junctures may be followed by periods of relative stability (during which outcomes of the critical juncture are reproduced) until a new shock intervenes to create a window of opportunity for further institutional change. Given the substantive focus of my analysis, the most relevant exogenous shocks are significant technological changes or shifts in state power and interests—explanatory factors often invoked by choice-based theories of institutional change (Keohane, Citation2017, p. 324).

But whilst such exogenous changes may loosen constraints on action, actors’ responses to changing conditions remain constrained—at least in part—by pre-existing institutional structures which shape the costs and benefits of alternative paths of action (Farrell & Newman, Citation2010; Soifer, Citation2012; Solingen & Wan, Citation2016, p. 11). This is especially true in densely institutionalized settings, where the ability of individual institutions to respond to changing environmental demands is likely to be constrained by the state-of-play in other, linked, institutions. This suggests that each move towards institutional fragmentation in a regime complex (i.e. each corrosion of hierarchy and institutional differentiation) increases the likelihood of further steps along that path by lowering the costs of venue-shopping and by making institutional reintegration increasingly difficult and costly. The upshot is that IRCs subject to reactive feedback processes tend to grow increasingly ‘unstable’ over time, meaning that actors are increasingly less capable of re-establishing hierarchical authority relations and task-differentiation in the wake of exogenous perturbations to either dimension of a regime complex’s structure.

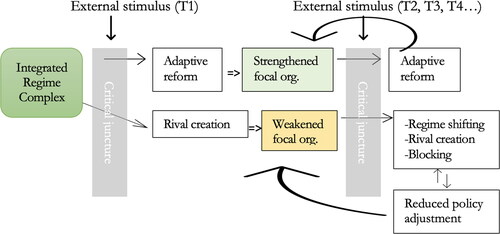

specifies two path-dependent sequences that either reinforce an existing institutional architecture or lead to a progressive unravelling of hierarchy and task-differentiation in an IRC.

The feedback loops depicted in are not exhaustive of the types of feedback processes that may unfold in IRCs, nor deterministic. Agency matters. For example, whilst undifferentiated institutions espousing competing rules may enable states to shirk obligations, it is not given they must do so (Kreuder-Sonnen & Zürn, 2020). States may instead choose to privilege some rules over others, and institutional agents may willingly defer to one another, thereby producing and reproducing hierarchical authority relations. Importantly, rule conflict—once introduced—need not be permanent but may trigger a process of institutional accommodation and re-integration. After all, dissatisfied states frequently engage in regime-shifting or rival creation, not merely to shirk specific obligations, but also to increase their bargaining leverage with the goal of pressuring existing institutions to change (Morse & Keohane, Citation2014). Yet, insofar as the existence of multiple, conflicting rulesets may diminish collective gains from cooperation by reducing scale-economies and increasing uncertainty, a rationalist notion of ‘institutional efficiency’ suggests that institutional fragmentation will generate subsequent pressure for inter-institutional accommodation or re-integration to recapture lost cooperation gains (Amable, Citation2003; Johnson & Urpelainen, Citation2012; Verdier, Citation2022). Indeed, there are many historical examples of states dissolving, merging, or reforming international institutions to better align rules or settle rival authority claims (Eilstrup-Sangiovanni, Citation2022). Likewise, institutions are often found to deliberately differentiate their functions to reduce competition with others (Gehring & Faude, Citation2014), thereby limiting states’ options for venue-shopping (Henning & Pratt, Citation2023). As such, the reactive sequence outlined above is not deterministic. Rather, each step is a probabilistic statement about the effects an exogenous shock can be expected to have on an IRC, given its pre-existing institutional architecture. As the sequence unfolds (from left to right), however, the probability of further institutional fragmentation (as opposed to re-integration) increases. Another way of stating this point is that the weight of ‘contingency’ is reduced while endogenous structural constraints exert increasing influence over institutional outcomes. The result is reduced system stability (as the odds of re-establishing clear authority-relations and task-differentiation during new critical junctures grow progressively dimmer—though not impossible).

The theoretical possibility of both reproductive/self-reinforcing and reactive feedback dynamics in IRCs raises a hurdle for theorizing processes of regime-complex evolution. As Drezner (Citation2009) complains, unless there is some way to divine whether actors will respond to prior events with a reinforcing or reactive strategy, a path-dependent historical explanation for institutional change remains entirely backward-looking and prone to ‘just-so’ narratives of causal chains of events which fail to dismiss a plethora of possible alternatives (Soifer, Citation2012). This raises the question: Under what conditions is path-dependence likely to trigger reactive processes of growing institutional fragmentation rather than institutional reproduction and realignment?

To answer this question, I look to existing institutionalist theories to derive conditioning factors, or what Soifer (Citation2012) labels ‘productive conditions’, which shape the outcomes that emerge from a critical juncture and thus influence an IRC’s susceptibility to reactive sequencing and fragmentation. As the Introduction to this special issue highlights, a strong incumbent focal institution to which other actors orient themselves is widely believed to constrain institutional proliferation (Gehring & Oberthür, Citation2009; Abbott et al., Citation2015; Hofmann & Yeo, Citation2023). Focal institutions are often the original recipients of grants of authority in an issue-area, with the most extensive membership and mandate (Henning & Pratt, Citation2023, p. 11). As prominent ‘first-movers’, these institutions possess informational advantages and elemental expertise that enable them to orchestrate later entrants and defend their regulatory turf (Heldt & Schmidtke, Citation2019). Hence, IRCs that emerge around prominent focal institutions are more likely to uphold hierarchical authority-relations and limit rule conflict (Henning & Pratt, Citation2023, p. 11).

To be sure, an initial vesting of authority in a strong central institution may not ensure path-dependent hierarchy, since a focal institution’s authority can be challenged (Amable, Citation2003, p. 68). Whether or not this happens may depend on institutional design. For example, a focal institution whose formal procedures are too rigid to accommodate demands for change—say, due to unanimity requirements—is less likely to constrain rival rule making. Likewise, a focal institution that excludes one or more central players in an issue-area is more likely to see its authority undermined by noncompliance because noncooperation by outsiders provokes noncompliance by affected regime members (Hanrieder & Zürn, Citation2017). On this basis, I speculate that reactive sequences fueling institutional fragmentation are more likely in IRCs with weak focal institutions (productive condition #1).

A second conditioning factor of IRC stability (i.e. the capacity to accommodate demands for change in a manner that preserves hierarchical authority relations and task-differentiation) is the capacity for autonomous action by institutional bureaucracies or independent judiciaries that may use their agenda-setting power, decision-making competences, and epistemic authority to arbitrate conflicting state demands, or to creatively adapt existing rules and practices to new political realities. Thus, reactive sequences are more likely in IRCs featuring low institutional autonomy (productive condition #2).

A third conditioning factor is preference alignment among member states. Somewhat self-evidently, if central players in an IRC are relatively united in their desire for institutional change (e.g. because they are similarly affected by an exogenous shock), adaptation of existing institutions through reform or constructive re-interpretation of existing rules becomes more likely. Conversely, if state preferences clash during critical junctures, these junctures are more likely to usher in regime-shifting or rival creation. Nevertheless, I argue, even states with relatively aligned preferences will find it progressively harder to respond to exogenous shocks in ways that reinforce existing institutional boundaries and hierarchies, the more fragmented the pre-existing institutional architecture is. Thus, I expect diverging state preferences to increase the likelihood of reactive sequences in IRCs (condition #3).

To summarize, I have argued that changes in regime-complex architectures are shaped, not merely by exogenous changes in material factors, but also, importantly, by endogenous feedback loops whereby existing institutional architectures produce effects which in turn affect these architectures. Specifically, I have explained how exogenous shocks can trigger reactive sequences in which successive institutional choices lead to growing fragmentation. In addition to this core proposition (P1), I have identified three conditioning factors (strength of focal institution, institutional autonomy, and state preference alignment) which affect the likelihood of reactive sequences. Importantly, I do not argue that endogenous factors are per se more important than exogenous ones in explaining the fragmentation of IRCs, only that they are substantively consequential, and increasingly so over time.

In line with the broader theoretical framework guiding this special issue, I expect an erosion of hierarchy and task-differentiation to lead to reduced policy adjustment (Proposition 2) ().

Table 1. Theoretical expectations.

Methodology

As already discussed, the reactive sequences outlined here are not deterministic. Rather, each step is a probabilistic statement regarding the expected effects of an exogenous shock on an IRC, given its pre-existing institutional architecture. As such, as Hanrieder and Zürn (Citation2017, p. 112) note, the concept of reactive sequences can ‘hardly be translated into hypotheses that posit a strong relationship between an initial condition and a final outcome’. Indeed, citing Keohane (CitationCitation2017, p. 330), ‘it is not reasonable to demand strong ex ante hypotheses…from an orientation that emphasizes the contingency of history and its dependence on complex sets of contextual factors’. Nevertheless, my model identifies clear causal mechanisms whose influence can be confirmed ex-post through careful process-tracing (Bennet, 1999).

To probe the validity of my path-dependent model of IRC evolution, the next part examines the NRC during three historical periods: 1974–1990; 1990 to early 2000s; and 2000–2020. The start of each of period has been identified in previous scholarship as a ‘critical juncture’ at which a ‘proliferation shock’ prompted significant institutional change (Cottrell, Citation2016, p. 8; Solingen & Wan, Citation2016). While the NRC has arguably undergone additional critical junctures since its inception, my narrative thus follows established literature in highlighting three major turning-points in the NRC’s history. Within each period I examine whether institutional change reinforced or undermined existing authority relations and task divisions, and through what processes. In doing so, I rely on causal process observation (Brady & Collier, Citation2004, p. 277); looking for insights that provide critical information about the context, process and mechanisms that produce given outcomes. By examining three discrete (but adjoined) periods of the NRC’s evolution, I am able to probe the relevance of my hypothesized conditioning factors which, although they may be relatively invariant within each period, are liable to vary from one period to the next.

Exogenous shocks and reactive sequences in the NRC

Regime complexity in nuclear politics: a brief introduction to the NRC

Before introducing my analytical narrative, I briefly introduce the set of overlapping international institutions governing nuclear non-proliferation. Within the conceptual boundaries of the NRC, I include formal and informal institutions tasked with regulating nuclear issues—including non-proliferation, trade in dual-use items, peaceful nuclear power, weapons testing, and disarmament, as well as major bilateral nuclear arms limitation treaties.

The cornerstone of the NRC is the 1968 Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT). The NPT institutes a legal framework based on three core principles or ‘pillars’: (1) The five states that exploded nuclear weapons before January 1967 commit not to proliferate such weapons, while non-nuclear weapon states (NNWS) vow to forego nuclear weapons indefinitely, subject to verification by the IAEA; (2) Nuclear-weapons states (NWS) pledge ‘to pursue general and complete disarmament’ (Article 6); (3) All parties are granted the ‘inalienable right’ to develop nuclear energy for peaceful purposes and to participate in ‘the fullest possible exchange of equipment, materials, and scientific and technological information for the peaceful uses of nuclear energy’ (Article 4).

Closely aligned with the NPT is the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) created in 1957 to promote the ‘contribution of atomic energy to peace, health and prosperity’. Predating the NPT, the IAEA was not originally conceived as a non-proliferation agency but focused on technical assistance (Wan, Citation2014). Upon negotiating the NPT in 1968, however, states entrusted the IAEA with verifying NPT obligations through its Model Safeguard Agreement. The IAEA today serves both as a diplomatic forum and a technical bureaucracy.

A third central institution is the UN Conference on Disarmament (CD), founded in 1979 to serve as ‘the single multilateral disarmament negotiating forum of the international community’. During the 1960s and 1970s, the CD and its forerunnersFootnote3, negotiated pivotal nuclear arms-control treaties—including the NPT and several nuclear test-ban treaties—but since then the Conference has been largely deadlocked.

Other central multilateral institutions include the six Nuclear-Weapons Free Zones (NWFZs)Footnote4 negotiated between 1959 and 2006; the 1963 Limited Test-Ban Treaty prohibiting nuclear test detonations above ground; the 1967 Outer Space Treaty banning nuclear weapons in space; the 1972 Seabed Treaty which bars states from placing nuclear weapons on the ocean floor beyond a 12-mile coastal zone; the 2005 Convention for the Suppression of Acts of Nuclear Terrorism; and the 2017 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear-Weapons.

Major bilateral nuclear arms-control treaties also form part of the NRC insofar as they restrict vertical proliferation by countries (mainly the US and Russia) that control the bulk of the world’s nuclear arsenals. These include the 1974 US-USSR Threshold Test-Ban Treaty which bans underground nuclear tests with an explosive force of more than 150 kilotons; the Peaceful Nuclear Explosions Treaty (1976) which limits the explosive yield of nuclear tests; and the now abrogated Anti-Ballistic Missile (1972–2001), and Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces treaties (1987–2019).

Finally, a wide network of informal export control institutions and transgovernmental non-proliferation initiatives has emerged around the NPT and IAEA; inter alia, the Nuclear Suppliers Group; the Proliferation Security Initiative; the Global Threat Reductive Initiative; and the G8 Partnership against Spread of WMD.

In sum, the NRC comprises myriad formal and informal institutions focused on nuclear non-proliferation, arms-control, disarmament, and nuclear safeguarding. These institutions intersect and overlap to produce both reinforcing and conflicting obligations. Conjointly (and individually in the case of the NPT), they institute three fundamental principles of nuclear governance, namely ‘nonproliferation’, ‘gradual disarmament’ (preserving stable nuclear deterrence), and ‘peaceful nuclear cooperation’. Whilst they were originally viewed as complementary, as they have been advanced through separate but overlapping institutions, these principles have come into growing conflict thereby fueling institutional fragmentation.

T0. The NRC (1969–1973)

As they were initially arranged, institutions of the nascent NRC were relatively hierarchically organized and functionally differentiated insofar as different institutions governed separate geographic regions (e.g. the NWFZs) or functional domains (e.g. nuclear testing in space, under water, etc.). Preeminent bureaucratic, technical, and moral authority was assigned to the NPT, while other institutions—including the incumbent IAEA—served a supplementary role of implementing or reinforcing NPT rules. Rule conflict was low insofar as the rules of existing NWFZs and test-ban treaties, and the practices of existing regional regulatory bodies like EURATOMFootnote5, overlapped the NPT in ways that strengthened its core principles by layering multiple mutually reinforcing prohibitions atop one another. This was also true of bilateral arms-control measures introduced during this period, such as the ABM Treaty and the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks Agreement (SALT-1) signed in 1972. By limiting the nuclear arsenals of the superpowers, these agreements presented a means to fulfil NPT disarmament obligations under Article 6. At the same time, however, they also institutionalized a parallel norm of ‘negotiated and controlled nuclear possession’ which has increasingly come to clash with how Article 6 obligations are interpreted by many NNWS.

The 1968 NPT tied together existing treaties and regulatory bodies into a loosely integrated governance system based on principles of verified non-proliferation, gradual disarmament, and peaceful nuclear cooperation. However, it also left open crucial questions related to monitoring and restrictions on nuclear trade. Article 3 of the NPT provides that suppliers of nuclear materials and technology must withhold these from NNWS unless specific safeguards are agreed with the IAEA. This requirement was given substance by the IAEA’s 1972 Model Agreement which outlines practices for reporting and inspection of nuclear facilities through so-called Comprehensive Safeguard Agreements (CSAs) with the IAEA (Wan, Citation2014, p. 219). However, CSAs apply only to NPT parties, leaving open the question of how to restrict nuclear transfers to non-members. Thus, in 1971, a group of seven major nuclear supplier states,Footnote6 chaired by Claude Zangger, met informally to agree upon rules for transfers of nuclear materials to non-NPT members. As an informal body, the Zangger Committee’s decisions bypassed the IAEA’s Safeguard Committee and the NPT’s formal treaty review structure. Instead, the ‘Common Understandings’ agreed by the Zangger Committee were given legal effect through unilateral declarations to the IAEA (Wan, Citation2014; INFCIRC/209). Nevertheless, by adding non-proliferation controls vis-à-vis outsiders to existing controls applicable to NPT members, the Zangger Understandings served to increase—for now—the rule coherence of the nascent regime complex. Overall, institutional developments during this early period thus served to reinforce the authority of the NPT and IAEA. This confirms my theoretical expectations given the presence of an initially strong focal institution that was able to guide the elaboration of supplementary rules to extend its regulatory reach (Condition 1) as well as relatively aligned state preferences (Condition 3).

T1: india’s nuclear test (1974–1989)

The successful explosion of a nuclear device in May 1974 by India—a non-NPT member—provided the first critical test for the nascent NRC, raising acute concerns about the effectiveness of existing rules regarding state-to-state transfers of nuclear materials and technology (Simpson & Howlett, Citation1994, pp. 45–47; Solingen & Wan, Citation2016, p. 11).Footnote7 Given the IAEA’s preeminent technical and bureaucratic authority in this domain, Director-General Sigvard Eklund swiftly established a Standing Advisory Group for Safeguards Implementation (SAGSI) (Wan, Citation2014). Comprising experts from ten states with advanced nuclear programs, SAGSI was tasked with urgently evaluating and improving the effectiveness of IAEA safeguards.

However, two problems undermined the IAEA’s ability to adjust to the shock dealt by India’s nuclear test by tightening existing nuclear safeguards. First, while the Zangger Understandings limited nuclear transfers to non-NPT members, they did not apply among NPT parties. Second, nuclear supplier states not party to the Understandings were under no obligation to restrict nuclear exports to states inside or outside the regime. For example, France (not an NPT member) had provided reprocessing plants to Pakistan, South Korea, and Taiwan, while West Germany (an NPT member but not party to the Zangger Understandings) had shared sensitive nuclear technology with Brazil. These patchwork obligations hampered efforts to strengthen nuclear export restrictions through IAEA negotiations and thus provide an early illustration of how institutional fragmentation can undermine a focal institution’s ability to adapt to an exogenous shock.

Given these constraints, in parallel to negotiations through SAGSI, a group of major nuclear supplier states met in 1974 to form the informal Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG). Unlike the existing Zangger Committee, the NSG included West Germany, Japan, and France. Moreover, while the Zangger’s so-called ‘Trigger List’ of substances subject to export restrictions was limited to items falling under NPT Article 3, the NSG’s ‘Guidelines on Nuclear Transfers’, published in 1978, bore no direct relation to NPT requirements, and were significantly more stringent than the Zangger Understandings (Simpson & Howlett, Citation1994, p. 48). Yet, despite differences in membership and rules, the two groups ‘serve the same objective and are equally valid instruments of nuclear non-proliferation efforts’ (nti.org). The creation of the NSG thus demonstrates how the failure of the Zangger Committee to include all relevant stakeholders undermined the IAEA’s ability to defend its regulatory turf and facilitated the emergence of conflicting rules and rival authority claims.

The fault-line introduced by the NSG was not immediately evident. Indeed, the period following the NSG’s creation was one of significant growth for the IAEA, as more and more nuclear facilities in NNWS became subject to IAEA Safeguards (Solingen & Wan, Citation2016, p. 12). Nevertheless, over time, the NSG’s strong bias towards denial of transfers of dual-use nuclear technology has increasingly been decried by NNWS as a violation of Article 4 of the NPT which states that ‘all Parties…have the right to participate in, the fullest possible exchange of equipment, materials and scientific and technological information for the peaceful uses of nuclear energy’ (Miller, Citation2012, p. 25). In turn, this has led to growing institutional contestation.

As predicted, conflicting rules have also reduced policy adjustment by facilitating forum-shopping and raising uncertainty regarding obligations (Proposition 2). Although more stringent than the Zangger Understandings, the NSG ‘Guidelines’ are not legally binding, leaving participating states significant discretion. Thus, after joining the NSG, Russia and China continued to honor nuclear contracts with India and Pakistan, claiming these were ‘grandfathered’ by previous agreements.Footnote8 Likewise, during the 1980s, the Reagan Administration looked the other way as Pakistan assembled its nuclear arsenal with the aid of millions of dollars’ worth of restricted, high-tech materials bought in the US, Germany, and Switzerland (Hersh, Citation1993). Thanks partly to such compliance gaps, horizontal proliferation inched forward as countries like Iraq and South Africa developed nuclear weapon programs in relative secrecy assisted by Western firms (and complicit governments).

T2: end of the Cold War (1990–1999)

The collapse of the Soviet Empire marked a second critical juncture for the NRC (Cottrell, Citation2016). After widespread institutional inertia and compliance setbacks during the 1980s, the sudden end of East-West confrontation opened new opportunities for cooperation on non-proliferation and disarmament. However, it also gave rise to acute challenges (Cottrell, Citation2016). Overnight, the USSR gave way to 15 independent states, three of which (Belarus, Kazakhstan, Ukraine) possessed nuclear weapons (Schimmelfennig, Citation1994, p. 115). Meanwhile, traditional Cold War alliances weakened, prompting an acceleration of clandestine nuclear programs in countries like Pakistan, India, North Korea, Iran, and Iraq whose governments and militaries feared the loss of superpower security assurances (Verdier, Citation2008).Footnote9

As predicted (condition 3), the combination of a sudden exogenous shock and broadly aligning interests among major nuclear powers initially facilitated a strengthening of existing non-proliferation institutions. In 1990, Russia and the US approved the Threshold Test-Ban Treaty and the Peaceful Nuclear Explosion Treaty (signed in 1974 and 1976 but never ratified). From 1991, bilateral cooperation gained further pace with a new round of Strategic Arms Reduction Talks (START2). Finally, starting in 1991, a series of informal US-led initiatives, including the Cooperative Threat Reduction (CTR) Program and the Global Threat Reduction Initiative (GTRI), provided funding and technical assistance to safeguard ‘loose nukes’ and fissile materials in the former USSR (Council on Foreign Relations, 2012; Eilstrup-Sangiovanni, Citation2009, Citation2016).

Multilateral institutions were also reinforced. To preserve the integrity of the NPT, Russia assumed the USSR’s position as the only official NWS among the former Soviet Republics, while Azerbaijan, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Uzbekistan joined the NPT as NNWS parties. A supplementary protocol to the START2 Accord was signed in Lisbon in 1992 which committed Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Ukraine to renounce nuclear weapons and join the NPT within seven years. The NRC also expanded geographically as South Africa renounced its nuclear-weapons program and joined the NPT in 1991, followed by France (1991) and China (1992). Meanwhile, the CD admitted 23 new state parties, making it both more inclusive and less vulnerable to charges of ‘institutional capture’ by NWS.

Along with widening and deepening of NPT commitments, the IAEA’s authority also received a boost. During the 1990 NPT Review Conference (RevCon), state parties tasked the Agency with developing new inspections approaches (Solingen & Wan, Citation2016, p. 12), and in 1991, the Security Council tasked the IAEA with special monitoring missions to Iraq and South Africa. Building on these mandates, IAEA Governors in 1993 launched a program to strengthen the NPT’s verification regime by introducing an ‘Additional Protocol’ to the existing Comprehensive Safeguard Agreements.

But while the end of the Cold War prompted a strengthening of existing institutions and the layering of new institutions which served to reinforce existing rules and principles, the end of bipolar confrontation also pulled on threads which would threaten to destabilize the expanding NRC. The nuclear arms-control institutions created during the 1970s and 1980s were mainly designed to constrain superpower arms-racing (Glaser, Citation1992, p. 34). However, as viewed from Washington, superpower competition now gave way to an acute danger of horizontal nuclear proliferation. American intelligence revealed in May 1990 that Pakistan had assembled 6–10 nuclear weapons (Hersh, Citation1993). While this and other proliferation shocks—in North Korea and Iraq—facilitated efforts to strengthen IAEA safeguards through the Additional Protocol (Roehrlich, Citation2018) they simultaneously lessened US commitments to existing disarmament agreements.

The first retreat was the US decision to deploy limited ballistic missile defenses to protect against ‘accidental’ Russian attacks and ‘future third world threats’ (Glaser, Citation1992, p. 35). Despite Russian objections that this violated the 1972 ABM Treaty, the Bush Administration declared in 1992 that ‘We must have this protection because too many people in too many countries have access to nuclear arms’.Footnote10

The evolving IAEA safeguards regime also came under pressure. An IAEA-UN Joint Mission in Iraq in 1991 revealed that Bagdad had procured dual-use items that allowed it to build an advanced nuclear-weapons program, raising demands to tighten restrictions on state-to-state nuclear transfers (Solingen & Wan, Citation2016, p. 12). Yet rather than work through the IAEA, nuclear-supplier states turned to a rival regime: The NSG which had not met in formal session since 1978 resumed regular meetings in March 1991. The list of ‘sensitive items’ subject to outright export denials was expanded into a broader ‘Dual-Use List’ (INFCIRC/254-2) with effect from 1992. By using the NSG, rather than the IAEA, to institute tougher export controls, nuclear-supplier states were able to sidestep opposition from NNWS who regarded blanket denials of dual-use exports as a violation of their statutory rights under the NPT to benefit from access to peaceful nuclear technology (Miller, Citation2012, p. 26, 33). This instance of regime-shifting directly challenged the authority of the IAEA and imposed de facto changes in the NPT regime which lacked universal acceptance, angering many NNWS parties (op. cit.).

Tensions rose further during the 1995 NPT RevCon, which would decide whether to extend the NPT indefinitely.Footnote11 The five NWS favored indefinite extension while many NNWS objected this would imply the permanent legitimization of the nuclear privilege of the P5 (Grotto, Citation2010, pp. 18–19). Opposition by NNWS was kindled by several longstanding grievances. Since the 1970s, many NNWS had identified negotiation of a Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) as a decisive test for progress on nuclear disarmament (Grotto, Citation2010, p. 18). But whilst an ad hoc committee was established at the CD in 1982, formal negotiations failed to commence due to lack of support from nuclear powers.Footnote12 Exemplifying a ‘blocking’ strategy,Footnote13 many NNWS now refused to approve the indefinite extension of the NPT lest progress was made on negotiating the CTBT and the previously proposed Fissile Material Cut-off Treaty (FMCT), which would prohibit production of fissile materials for military purposes.

By blocking the NPT reform process, NNWS secured several concessions from NWS. Formal negotiations on the CTBT began in 1994. In March 1995 the CD established a committee to prepare negotiations of the FMCT. Agreement to extend the NPT was narrowly secured on 11 May 1995 after the parties had further agreed on a set of Political Benchmarks for progress on disarmament, including the conclusion of the CTBT no later than 1996; conclusion of the FMCT; and ‘[t]he determined pursuit by nuclear-weapon states of systematic and progressive efforts to reduce nuclear weapons globally, with the ultimate goal of eliminating those weapons’ (NPT, 1995). This package deal would be the last ‘big bargain’ within the NPT regime, achieved by bundling together several separate issues of nuclear nonproliferation and disarmament. In hindsight, however, NNWS gave up an important instrument of leverage as their agreement to extend the NPT indefinitely reduced immediate pressure on NWS to accommodate their demands (Pretorius & Sauer, Citation2022).

Perhaps as a result, the limited progress signaled by the 1995 RevCon soon proved illusory. A draft CTBT was presented to the CD in June 1996 where it failed to gain sufficient support. The same draft (submitted by Australia) was approved by the UN General Assembly in September 1996,Footnote14 but was essentially a dead letter as Washington ruled out ratification.Footnote15 Meanwhile, negotiations on a FMCT failed to start due, inter alia, to opposition from Pakistan (citing discriminatory NSG practices) and China who tied support for the FMCT to a third proposed agreement—the Prevention of an Arms Race in Space Treaty—which was opposed by the US (Sauerteig, Citation2019). This intricate deadlock vividly illustrates how reliance on multiple parallel institutions to close gaps in existing agreements can frustrate cooperation by preventing effective bundling of issues, given that each element of a ‘package deal’ requires separate approval by separate groups of states (Benvinisti & Downs, Citation2007).

Overall, what began as an era of cooperation and institutional reinforcement soon gave way to growing institutional contestation through regime-shifting and blocking. This confirms my core theoretical expectations regarding path-dependent institutional fragmentation. On the one hand, the sudden alignment of superpower preferences facilitated an initial process of institutional deepening and re-alignment through reform and institutional layering. On the other hand, an existing fragmented institutional structure meant that new horizontal proliferation threats (which divided NWS and NNWS in terms of their perceived risk and ideal solutions) prompted regime-shifting by NNWS and led to agreed disarmament objectives being abandoned. This in turn triggered growing contestation by NNWS through blocking of reform efforts.

In addition to being fueled by previous institutional ruptures (particularly the creation of the NSG), growing institutional contestation was also driven by procedural barriers to NPT reform (Condition 1). Given unanimity requirements, the NPT was slow and costly to reform. The adaptive capacity of the focal institutions was further reduced by years of perceived ‘double-dealing’ by the P5 which reduced willingness to compromise among NNWS. Thus, the end of the Cold War juncture illustrates how previous steps towards institutional fragmentation meant that states were unable to adapt to new geopolitical realities by strengthening NPT rules and safeguards, despite broad agreement by major nuclear powers that this was desirable.

As predicted (Henning & Pratt, Citation2023), growing contestation and the proliferation of conflicting rules during this period reduced behavioral adjustment. The US, Russia and China all walked back on promises to curtail nuclear testing, while the US Congress approved the National Missile Defense Act in 1999 in defiance of established arms-control norms (Wan, Citation2014, p. 713). In 1998, India and Pakistan conducted successful nuclear weapon tests, underscoring the seeming ineffectiveness of a nonproliferation regime complex that elicited limited compliance from core state parties.

T3. Rogue states & nuclear terrorism (2000–2020)

At the dawn of the twenty-first century, the specter of ‘rogue’ states and nonstate actors acquiring nuclear weapons dealt another shock to the NRC. North Korea’s withdrawal from the NPT in 2003 was followed by revelations that Pakistan’s chief atomic scientist, AQ Khan, had shared weapons technology with North Korea, Iran, and Libya. Inspections in Iran in 2004 revealed a secret enrichment program that had gone undetected by the IAEA, while evidence emerged that Syria was building a clandestine nuclear reactor with North Korean assistance (Nikitin & Hildreth, Citation2012). Meanwhile, concerns about nuclear terrorism grew in the wake of 9/11.

These multiple crises pointed to acute failures of existing nonproliferation institutions and thus loosened constraints on institutional change. Specifically, they exposed a gap in the NPT which does not address proliferation to or by nonstate actors. They also exposed a weakness in the 1980 Convention on the Physical Protection of Nuclear Material which is silent on the dangers of nuclear terrorism. Efforts to close the latter gap had begun in 1996 when the UN General Assembly established an ad hoc committee to draft a convention for suppressing nuclear terrorism (Resolution 51/210). However, in a now familiar pattern, talks had soon stalled as many NNWS opposed treaty language that could be perceived to legitimize continued state possession of nuclear weapons. To break the deadlock, the 2000 NPT RevCon now agreed on ‘Thirteen Practical Steps’ towards nuclear disarmament. Like the ‘Political Benchmarks’ agreed in 1995, these included conclusion of the CTBT and FMCT, reaffirmation of the objective of ‘general and complete disarmament’, and continued adherence by the US and USSR to the 1972 ABM treaty.

Evidencing a ‘critical juncture’ with heightened opportunities for change, some progress was made towards fulfilling the Thirteen Steps as Russia, UK and France all ratified the CTBT in 2000. However, the second Bush Administration soon introduced policies that reversed progress (Council on Foreign Relations, Citation2005). In the wake of 9/11, the US National Security Strategy of 2002 drew a sharp line between a Cold War world in which ‘WMD were considered weapons of last resort’ and a new world order in which the US was ‘confronted by “rogue states” and terrorists that see WMD as weapons of choice’.Footnote16 This new reality demanded not merely stronger nonproliferation efforts but also ‘proactive counter-proliferation’. In the summer of 2002, the US withdrew from the ABM treaty labelling it a ‘hindrance to effective defenses against non-state actors and “rogue states”’. Russia responded by withdrawing from START-2.Footnote17 In response many NNWS declared their unwillingness to sign off on further nonproliferation safeguard measures during the upcoming 2005 RevCon (Council on Foreign Relations, Citation2005).

As formal processes of multilateral nonproliferation cooperation and bilateral arms-control ground to a halt, a new wave of regime-shifting and rival regime-creation unfolded through which de facto amendments of existing agreements were accomplished via extra-legal workarounds and new informal initiatives. In May 2003, Washington launched the Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI), an informal initiative focused on intercepting transfers of WMD and dual-use technology. Next, in February 2004, the US turned to the NSG to tighten nuclear export controls and safeguards. ‘I propose a way to close the loophole’ President Bush declared in reference to the NPT’s Article 4 which grants NNWS the right to acquire nuclear technology for peaceful purposes. ‘The 40 nations of the NSG should refuse to sell enrichment and reprocessing equipment to any state that does not already possess full-scale, functioning enrichment and reprocessing plants’.Footnote18 He thereby highlighted the deepening rift between NPT parties who regarded cooperation on nuclear energy as an ‘inalienable right’ and those who viewed Article 4 commitments as a fundamental design flaw in the NPT (Miller, Citation2012, p. 22).

As during earlier junctures, international bureaucracies attempted to shore up the authority of central institutions and preserve institutional coherence by amending existing multilateral agreements to reflect new geopolitical realities. Following President Bush’s remarks, IAEA Director-General, Mohamed ElBaradei, publicly reiterated the IAEA’s recommendations for strengthening existing NPT safeguards (ElBaradei, Citation2004). These included ‘universalizing the NSG’s export-control system’ to enact ‘binding, treaty-based controls’ for all NPT parties; universal adherence to the Additional Protocol; amending the NPT to bar state withdrawals; starting negotiations on a FMCT; and bringing into force the CTBT (Council on Foreign Relations, Citation2005). But while Washington welcomed the proposal to universalize the Additional Protocol, CTBT ratification was flatly rejected (Braun & Chyba, Citation2004; Council on Foreign Relations, Citation2005).

With dim prospects of gaining agreement to tighten existing nonproliferation controls through the NPT/IAEA, NWS shifted their focus to alternative venues (Nikitin & Hildreth, Citation2012). In April 2004, the Security Council adopted Resolution 1540, a binding instrument requiring all UN members to ‘criminalize proliferation, enact strict export controls and secure all sensitive materials within their borders’.Footnote19 Although it involved the assertion of formal hierarchical authority, this act of UNSC ‘lawmaking’ undermined the authority of the IAEA and anticipated the outcome of ongoing negotiations of a convention for suppressing nuclear terrorism by imposing rules upon all UN members regardless of treaty endorsement (Fehl, Citation2014).

Reliance on informal institutions also increased. In May 2004 China joined the NSG which it had long labelled ‘discriminatory’. In June that year the G8 agreed to limit sales of enrichment and reprocessing-related nuclear technology to states that already possessed full-scale enrichment and reprocessing capability, thereby implementing Bush’s proposed reform of the NSG through the even more exclusive G8. In doing so, NWS preempted the IAEA’s proposals to universalize export controls through formal treaty amendments (Braun & Chyba, Citation2004, p. 40; Miller, Citation2012, p. 33). Finally, in July 2006, Russia and the US announced the Global Initiative to Combat Nuclear Terrorism, a ‘flexible framework to prevent, detect, and respond to threats of nuclear terrorism’. Together these steps aptly illustrate how an initial weakening of hierarchical authority relations can loosen constraints on further rival regime creation and regime-shifting, as predicted in the theoretical section. They also illustrate how institutional ‘blocking’ can prompt venue-shifting given the existence of outside options: Owing largely to disillusion among NNWS with nuclear powers’ use of informal agreements to introduce ‘discriminatory measures’ that exceeded the differential treatment foreseen in the NPT (Fehl, Citation2014), both the 2005 and 2010 RevCons failed to achieve agreement on new formal safeguards. Blocking by NNWS in turn prompted NSG members to further strengthen informal guidelines governing the transfer of nuclear fuel cycle facilities during a 2011 Plenary meeting in the Netherlands (Miller, Citation2012, p. 33), evidencing a distinct negative feedback loop.

The perhaps clearest example during this period of how an initial erosion of inter-institutional hierarchy and functional differentiation can fuel further institutional fragmentation is the 2005 US-India Nuclear Agreement which extended cooperation on civil nuclear technology to India—an unrecognized nuclear power outside the NPT. This deal was followed by the so-called ‘NSG waiver’ in 2008, which lifted sanctions against India, promoting it overnight from being a major target of nuclear export controls to a trusted recipient of nuclear technology (Fehl, Citation2014). Formally recognizing India’s nuclear-power status through NPT accession stood little chance of success since this would require approval by all existing state parties (Wan, Citation2014). But by shifting cooperation to the NSG—an exclusive club with fewer veto-points whose members stood to profit directly from nuclear trade with India—NWS were able to grant unofficial recognition of India’s nuclear-power status, thereby awarding the privileges associated with NPT membership through the backdoor (Frankenbach et al., Citation2021; Fehl, Citation2014). This move, which was made possible by the existence of two parallel regimes that claim an equal right to regulate transfers of nuclear technology (Miller, Citation2012), is widely seen to have undermined the NPT’s authority by leading many NNWS to question what benefits they gain from treaty compliance (Nikitin & Hildreth, Citation2012; Meier, Citation2019, p. 270). Due to tight institutional overlaps, negative feedback effects have rippled beyond the NPT through the wider regime complex. For example, observers link Pakistan’s refusal to endorse formal negotiations on a FMCT to its disillusionment with the privileged treatment of India through the NSG/NPT (Ghoshroy, Citation2016).

To be sure, institutional developments during the 2000s were not all disintegrative. A limited re-alignment of institutional objectives was achieved in April 2005 when the General Assembly approved the Convention for Suppression of Acts of Nuclear Terrorism. But whilst it signified a partial assimilation of parallel institutional efforts to tackle nuclear terrorism (in the IAEA, NSG, and UNSC), the Convention also highlighted existing fissures within the NRC. Article 4 reads: ‘This Convention does not address, nor can it be interpreted as addressing, in any way, the issue of the legality of the use or threat of use of nuclear weapons by States’.

Overall, the period is best described as one of institutional fragmentation. During the early 2000s, the IAEA saw its bureaucratic, technical, and moral authority to regulate civilian nuclear technologies on basis of the NPT eroded by informal export-control measures and formal UNSC Resolutions which claimed an equal authority to govern transfers of nuclear technology (Miller, Citation2012). Growing reliance on ‘non-integrative’ arms control dominated by a few states undermined core principles underlying the NPT, such as universality, formal equality, and consensus-based decision making (Fehl, Citation2014). Meanwhile, the ‘securitization’ of sharing of nuclear technology for peaceful purposes was seen by many NNWS to further distance the NPT regime from disarmament (Verdier, Citation2008). In protest, they blocked reform of nonproliferation measures within the NPT, thereby incentivizing further venue-shifting by NWS.

Institutional developments during the 2000s clearly illustrate how initial acts of regime-shifting and rival creation, by undermining the authority of a focal institution and facilitating forum-shopping and regime-shifting, can trigger a reactive sequence of reduced policy adjustment, and growing institutional contestation through blocking, rival creation, and further venue-shifting. They also show how a fragmented institutional architecture can impede adjustment to exogenous shocks through reform of existing institutions. As Solingen and Wan observe (Citation2016, p. 13), compared with proliferation challenges in the 1990s which initially expanded the powers of the IAEA, successive non-compliance shocks during the 2000s ‘did not elicit more than operational tweaks within the IAEA’. Instead, ‘adjustment’ took the form of rival institutional creation and extra-legal workarounds that further eroded inter-institutional hierarchy and differentiation. The stronger ‘reactive’ response to exogenous change during the 2000s (compared to the 1990s) reflected both a more fragmented institutional landscape and the presence of several ‘conditioning factors’ including high barriers to reform of the focal NPT (Condition 1), lacking institutional autonomy (Condition 2), and clashing preferences among NPT parties (Condition 3) which further reduced prospects for institutional (re)integration.

Fast-forwarding to the present, the perhaps starkest illustration of how a non-hierarchical and undifferentiated NRC has fueled further institutional fragmentation is the adoption of the 2017 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW). By outlawing possession of nuclear weapons, the TPWN represents a departure from the principle of ‘gradual and controlled disarmament’ enshrined in the NPT. Whereas proponents depict the TPNW as a ‘pathway for the implementation of Article 6 of the NPT’ (Heisbourg, Citation2019; Ingram, 2019), critics argue it reduces the NPT’s moral authority by introducing a rival international norm regarding nuclear disarmament (HOL, 2019, p. 395; Price, Citation2019, p. 403; Schulte, Citation2019, p. 402; Tannenwald, Citation2020; Wheeler, Citation2019), and by bringing ‘duplicate obligations upon the signatory states’ which may provide political cover for abandoning NPT obligations (Roberts, Citation2019, p. 399; Tzinieris, Citation2019). Importantly, whereas previous instances of rival institutional creation were, at least in part, reactions to exogenous changes (but facilitated by nonhierarchical authority relations), the TPNW is a product of longstanding cleavages within the NRC. It thus illustrates how ‘reactive sequences’ in IRCs can become largely self-sustaining and essentially endogenous.

Conclusions

This special issue focuses on the consequences of different international regime-complex architectures for contestation and policy adjustment. But regime-complex architectures are not static. During the 1960s and early-1970s, institutions comprising the NRC were largely hierarchically arrayed and functionally differentiated. Cooperation was centered on a clear focal institution, the IAEA/NPT, with broad membership and mandate, and extended through supplementary, and mostly subordinate, treaty agreements and implementing bodies. Over time, however, the NPT’s authority has been progressively eroded by the creation of new formal and informal institutions; inter alia, informal export-control regimes, UNSC Resolutions, high-level diplomatic initiatives, and rival treaties that claim an equal right to regulate nuclear transfers and arms limitations. Institutional differentiation has likewise decreased as new institutions such as the TPNW and various UNSC Resolutions have intruded upon the turf of existing regulatory bodies, offering alternative means of reporting and monitoring similar processes.

This article has illustrated how IRCs evolve through an interchange between endogenous path-dependent processes and contingent exogenous shocks or ‘critical junctures’. Specifically, by charting shifting constellations of hierarchy and differentiation in the NRC, I have shown how IRCs may be subject to self-reinforcing reactive sequences which make it progressively harder to restore a measure of inter-institutional hierarchy and differentiation in the wake of exogenous disruptions to either dimension—i.e. that lead to a loss of system stability.

The evolution of the NRC confirms the broad theoretical expectations outlined in the Introduction to this special issue (Henning & Pratt, Citation2023). As forecast, non-hierarchical authority relations and lack of differentiation have fuelled institutional contestation through regime-shifting, rival creation, and blocking. In turn, this has resulting in low policy adjustment as conflicting rules have made it easier for states to proliferate restricted materials or disregard disarmament obligations with low reputational costs. While my findings support the main conjectures of this issue’s Introduction, they also suggest qualifications and avenues for future research. The issue Introduction hypothesizes that a strong focal institution with a broad mandate and membership will constrain rule conflict through effective ‘meta-governance’. Despite having a broad mandate and near-universal membership, the NPT defies this expectation. Although it is the world’s most inclusive security treaty, there is a perilous gap in the NPT’s coverage: Three of the world’s nine nuclear powers (India, Pakistan, and Israel) have never joined, and a fourth (North Korea) withdrew in 2003. These states’ penchant for self-help provides an omnipresent incentive for NPT parties to shirk their treaty obligations (cf. Hanrieder & Zürn, Citation2017), and thereby limits its NPT’s gravitational pull.

Another fault-line in the NPT concerns the recognized centrality of nuclear weapons to international security. The twin principles of nonproliferation and ‘gradual disarmament’ enshrined in the NPT coexist with a rival principle (i.e. a set of beliefs of fact, causation, and rectitude; Krasner, Citation1982), which holds that a balanced possession of nuclear weapons is instrumental to international peace. This principle has been institutionalized in a series of bilateral agreements between the US and Russia which place limited, verified constraints on nuclear arsenals (Walker, Citation2000, p. 703). While helping to discharge NPT disarmament obligations, these agreements have also grounded a competing principle of ‘stable nuclear deterrence’ as the most reliable way to limit nuclear risk (Miller, Citation2012; Ritchie, Citation2019, p. 419; Wan, Citation2014, p. 707) which has curtailed disarmament and created growing tension between the NPT’s three pillars.

A third distinguishing feature of the NPT is its inflexible design. The NPT establishes a rigid formal hierarchy of official NWS v. nuclear ‘have-nots’, reflecting the temporary nuclear monopoly of the P5 at its foundation (Ritchie, Citation2019, p. 418). The constitutional impossibility of parties changing status has rendered the NPT incapable of adjusting to shifting power-balances or absorbing shocks from proliferation by bringing new nuclear powers like India fully into the institutional order (Wan, Citation2014). The solution so far has been extra-legal workarounds, such as the US-India nuclear deal and NSG waiver, that have directly challenged the NPT’s authority. By comparison the biological and chemical weapons conventions—neither of which differentiate the substantive rights of party states (Fehl, Citation2014) or leave out important stakeholders—have not struggled to defend their focality to the same extent. These observations suggest a need for further research into how the specific design of a focal institution impacts the evolution of an IRC.

A second area for future research is the design of secondary institutions. Previous literature has argued that overlapping institutions, when faced with competition due to conflicting rules, tend to adapt through ‘strategic differentiation’ or ‘spontaneous deference’. On this basis, the Issue Introducion suggests that while many new IRCs start out non-hierarchical and undifferentiated, competitive pressures tend to push gradually towards greater institutional hierarchy and differentiation (Henning & Pratt Citation2023, p. 11). The NRC fails to meet this expectation. Rather than hierarchy being an ‘emergent property’ of institutional interactions (Green, Citation2019; Pratt, Citation2018), hierarchical authority relations that were embedded in the NRC at birth have been progressively eroded. My theoretical discussion (in Part 2) suggests that lacking institutional autonomy may be partly to blame. Decentralized task-differentiation and spontaneous deference demand bureaucratic autonomy to allow institutional agents to develop effective strategies of specialization or mutual accommodation. Yet, in the context of nuclear arms-control, high stakes of cooperation have limited states’ willingness to grant independent powers to regulatory bodies to make or implement decisions, thereby reducing adaptive capacities. However, since institutional autonomy does not vary significantly during the period(s) under examination, my empirical analysis does not offer a direct test of this conjecture. The system-level effects of different levels of institutional autonomy is thus another area for future research.