Abstract

The theory of international regime complexity that frames this study specifies expectations for international cooperation stemming from different combinations of hierarchy and differentiation among institutions in regime complexes. This paper compares relationships between regional financial arrangements and the International Monetary Fund in the regional complexes for crisis finance in East Asia, Latin America, and the euro area during 2000-2019 and tests these expectations. Creditor states that sit at the nexus between global and regional institutions are particularly influential in the choice of architecture (the combination of hierarchy and differentiation) for these complexes but are constrained by arrangements inherited from previous decades. Once chosen, the complex’s architecture in turn shapes policy adjustment in borrowing countries and influences whether states pursue regime shifting or competitive regime creation when dissatisfied with institutions. These findings generally coincide with expectations, but exceed the degree of policy adjustment that the core theory expected for the euro area. Interinstitutional collaboration, the dynamics of which are elaborated, fills this explanatory gap. The paper concludes that relations among institutions are essential for understanding the outcomes and evolution of regime complexes and underpin a more complete explanation than provided by singular institutionalism, the power-gap hypothesis and other alternative approaches.

Introduction

Global governance in most issue areas can no longer be understood by analyzing individual multilateral institutions but rather clusters of institutions, which have come to be called ‘regime complexes’. The special issue in which this article appears offers a theory for comparative analysis of such complexes and tests its expectations against a broad range of issue areas to explain outcomes and contribute to better cumulation across studies in the research program on regime complexity.Footnote1 Regime complexes in crisis finance offer a particularly illuminating arena in which to examine the approach and compare findings with corresponding studies in other areas.

The present article tests a core proposition of the framework theory, that relations among institutions bear substantially on cooperation outcomes, by conducting a structured, focused comparison of the regime complexes for sovereign crisis finance in East Asia, Latin America, and Europe. It traces the development of each regional financial arrangement (RFA) during 2000-2019 and the extent to which its lending was linked to operations of the International Monetary Fund (IMF or Fund). For each region, it assesses relations of authority and differentiation among the institutions (the two dimensions that the theory identifies as causally important) and the consequences of the chosen architecture for policy adjustment and states’ subsequent strategies for reforming it. These particular complexes were selected for variation in authority and differentiation among the institutions composing them; but the sample also benefits from being regionally diverse, substantively important, as financial assistance provided through them affects millions of people, and thus prominent in policy discourse.

The study finds, first, that the relationship of each regional institution to the IMF is independently consequential and shapes the evolution of the regional complex over time. Second, in so doing, the article broadly confirms the expectations of the framework theory with respect to the combined effects of hierarchy and differentiation on substantive outcomes and strategies of institutional reform. But, third, it explains an outcome that is not anticipated by the framework by introducing inter-institutional collaboration as a separate, independent determinant of substantive outcomes—a supplement to the theory that completes the explanation of the European case.

This study further underscores that we need an institutionally complex analytical framework to understand the international political economy of financial rescues. Credits from multiple institutions are combined in rescue packages to the point where the complex, rather than individual institutions, must be the focus of analysis. These findings advance our knowledge of institutional interaction and the evolution of complexes beyond alternative explanations, namely the power-gap hypothesis and what we might call ‘singular institutionalism’.

The next section presents the concepts and theoretical framework for analyzing regime complexity that are adopted here and the central argument. The subsequent section examines the evolution of the IMF in the context of emerging regional arrangements, while the fourth section compares the regional complex in East Asia to those in Latin America and the euro area, draws analytical lessons from the comparison, and addresses threats to causal inference. The penultimate section introduces institutional collaboration into the theoretical framework, while the concluding section comments further on the evolution of crisis-finance complexes.

Concepts, theory, and argument

Consider now the concept of a regime complex, as the term applies to crisis finance, the main argument of the paper in the context of the theoretical framework, and its application to the regional level of analysis.

Concept and scope

This paper defines a regime complex as a set of international institutions that operate in a common issue area and the (formal and informal) mechanisms that coordinate them (Henning & Pratt Citation2023; Henning Citation2017a).Footnote2 The concept of an institution includes formal intergovernmental organizations (IGOs) at the bilateral, plurilateral, regional, or global levels as well as informal decision-making bodies. Transgovernmental regulatory networks, private transnational regulatory organizations and nongovernmental organizations fall within the definition in general, but the intergovernmental institutions play the leading roles in this particular issue area.

Crisis finance institutions address emergencies in the balance of payments and provide financing over the medium-term or longer, often with policy conditionality. These institutions thus address the financial condition of a country as a whole and its sovereign government. Provision of liquidity for banks and other private firms falls outside the functional boundaries, as we draw them here, except insofar as a private-sector collapse can bring on a sovereign crisis. Similarly, institutions that finance long-term projects for economic development, structural reform and infrastructure construction also fall primarily outside the scope of crisis finance—except when they might lend in support of a balance-of-payments program. An institution can sit in two or more regime complexes simultaneously when it performs governance functions in these issue areas.

Expectations and argument

The theoretical framework motivating this paper addresses both the sources and consequences of regime complexity, which we can refer to as ‘stage-one’ and ‘stage-two’ explanations. Relations among the institutions in the complex, referred to as its ‘architecture’, are intermediate, the product of stage one and the explanatory factor in stage two, in which ultimate outcomes take the form of policy adjustment and principals’ institutional strategies when contesting results.

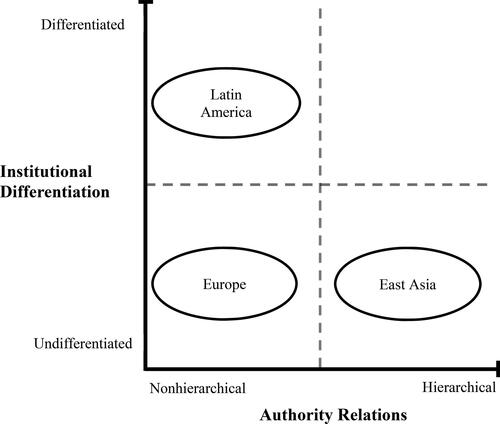

That theory privileges two variables—relations of authority among and differentiation of international institutions—as especially important in the meaningful classification of complexes.Footnote3 It argues that the combination of authority (or hierarchy) and differentiation determines substantive outcomes in global governance. Various combinations of the two variables can be expected to generate distinctive levels of policy adjustment and strategies of institutional reform, the latter taking two possible forms, regime shifting or competitive regime creation.

This paper emphasizes the role of the states with preponderant financial resources and situational leverage—‘linchpin countries’—in shaping the choice of authority relations and differentiation for the regional institutions and incumbent focal institution, the IMF, in the complexes for crisis finance. Linchpin countries sit at the nexus between the IMF and the regions and exercise influence in both directions. They include China and Japan within East Asia, Brazil and Mexico in Latin America, and primarily Germany, sometimes in coalition with other creditor states, in the euro area. The correspondence between the policies of the IMF and their preferences determines linchpin countries’ attraction to alternative institutional arrangements.

Linchpins’ preferences derive primarily from their status as creditors within the regional arrangement and their consequent desire to control its lending. These countries, some of which are borrowers at the global level, are too large to borrow through any regional facility. By virtue of their economic size and holdings of international reserves, they are sources of financing for smaller and more vulnerable countries within their regions. As creditors, they can shape RFAs, influence that can be accentuated by regional decision rules such as unanimity. As important members of the IMF, they exercise some influence over the Fund’s posture toward the RFA in their region. Borrowing countries also influence decisions on how regional institutions will relate to the IMF, but linchpin creditor countries generally hold more sway. Once chosen, hierarchy and differentiation among the institutions have effects on policy adjustment, regime shifting and regime creation that are independent, owing to linchpins’ inability to foresee the future consequences of architecture, autonomy of secretariats, competition or collusion among them, and feedback effects of institutions on member preferences.

The coherence of the rules, forum shopping, policy adjustment, and regime shifting and creation that are exhibited depend on the particular combination of authority relations and differentiation that has been adopted within each complex. Complexes that are hierarchical and differentiated are expected to exhibit relative consistency in rules, infrequent forum shopping, strong compliance, and relatively high hurdles to reform despite dissatisfaction on the part of principals. Nonhierarchical-undifferentiated complexes are expected to exhibit the opposite pattern of outcomes.

Complexes that are nonhierarchical and differentiated and those that are hierarchical and undifferentiated are both expected to show intermediate levels of compliance and policy adjustment. But they differ with respect to strategies of contestation. When states become dissatisfied with institutional arrangements, nonhierarchical-differentiated complexes are expected to exhibit competitive regime creation, whereas hierarchical-undifferentiated ones will show regime shifting. States might well pursue both, but we expect these particular outcomes to be the more successful ones in each situation.

This theoretical framework provides the core of the explanation for sovereign crisis finance. To preview one of the other conclusions, though, the study augments this central explanation with an additional outcome-shaping factor: Collaboration among institutions. States might create overlapping institutions without hierarchy yet still wish them to cooperate and therefore guide them to do so via regular institutional governance and external mediation of inter-institutional conflicts.Footnote4 The choice to constrain inter-institutional authority ex ante (when setting up complexes) and mediate deadlock ex post (after complexes have been established) is bound up in principals’ quest for control, which is elaborated in the penultimate section.

These arguments answer questions that two prevalent alternative approaches, namely the power-gap hypothesis and singular institutionalism, do not. The power-gap hypothesis derives ultimately from power transition theory and emphasizes the discrepancy between countries’ influence in formal governing arrangements within institutions and their material capabilities outside them.Footnote5 It expects that countries and regions that are under-represented in IMF governance are more likely to exercise their outside options by establishing alternative institutional arrangements.Footnote6 However, as we will see, the hypothesis fails to explain the relationships that are established between the regional institutions, once created, and the IMF.

Nor can outcomes be analyzed by the approach of singular institutionalism, the notion that institutions can be safely studied in isolation, and the findings of separate studies simply aggregated, to explain cooperation in areas governed by more than one institution. That approach has been implicit but widespread in institutionalist theories of IPE, and transcending it is a primary object of the regime-complexity research agenda. Contrary to it, the substantive consequences of multiple institutions operating in sovereign crisis finance are not the sum of non-interacted institutional output; relationships and interaction among global and regional financial institutions cannot be safely ignored.

Regional-level application

One useful feature of the framework theory is that it applies to different levels of analysis, in this case, to clusters of institutions operating at the regional level. The global financial safety net is best deconstructed into subcomplexes with the relationship between the RFA and IMF being at the heart of each.Footnote7 (Haftel and Lenz (Citation2020), Haftel and Hofmann (Citation2017), Gómez-Mera (Citation2015) and Hofmann (Citation2011) also examine regional complexes.) Relationships between the RFA and IMF within such complexes are the primary unit of analysis in this study and comparison among them its analytical method. For the remainder of the paper, these subcomplexes will thus be referred to simply as ‘regional complexes’.

Comparing regional complexes within the same issue area has a couple of analytical advantages over comparing global complexes across different issue areas as a test of theories of complexity. First, substantive characteristics are held constant across them. Among the regional complexes within crisis finance, there is little or no variation in the issue-specific functional requirements of cooperation or issue-specific coordination games to be resolved. Second, the three regional complexes examined here share the IMF; so, while the Fund is highly relevant to the evolution of these complexes, its own structure and policies are unlikely to be a source of variation among them. Eliminating that source of variation helps us to isolate the effects of hierarchy and differentiation in interinstitutional relations.

When applying the framework theory to regional complexes, we must be attentive to the possibility that actors from outside the complex could influence regional dynamics. If there were robust cooperation between the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) and the ASEAN+3 group, or if the choices confronting Thailand were somehow affected by the ESM’s relationship to the IMF, for example, it might be more appropriate to use a global concept than a regional one. But cross-regional effects are weak to non-existent in crisis finance.Footnote8 Operation of the complex for East Asia is almost entirely independent from that for the Latin American and euro area complexes. Because interaction is far denser within regions than between them, the regional level is the better one at which to apply the theory.

Conversely, attempting to analyze governance in crisis finance as a global complex rather than a collection of regional ones would encounter difficulty in characterizing hierarchy and differentiation, given disparities across the regions. Weighing low differentiation in one region against high differentiation in another, for example, would generate a global score that might not reflect actual differentiation in any region, be only weakly related to outcomes, and thus be misleading. Measurements of authority and differentiation taken at the regional level are thus a more reliable test of theory.

The IMF and its evolution in context

The IMF sits at the center of the web of organizations, facilities, and arrangements that contribute to the prevention of and response to financial crises. The emergence of new institutions over the decades has increased the complexity of institutional interaction in this issue area. This section reviews the challenges posed by the regional institutions and adaptation on the part of the IMF.

It is important to note that the IMF has never monopolized this issue space, and its centrality does not necessarily mean that it is dominant; instead, its leadership varies from one region to the other. From the beginning, the global institution shared this turf with other organizations and initiatives. The IMF was overshadowed, in fact, by the Anglo-American Financial Agreement and Marshall Plan in the second half of the 1940s and marginalized by the European Payments Union through the 1950s. Over the course of the 1960s and 1970s, nonetheless, it emerged as the leading institution in balance of payments and crisis finance. By 1980, although its dominance was circumscribed, it had clearly become focal.

Regional financial arrangements began to emerge in the 1970s and proliferated in the later decades of the twentieth century and early decades of the twenty-first.Footnote9 The early portion of this evolutionary process is examined elsewhere and lies largely beyond the time horizon of this paper. We concern ourselves in this study mainly, albeit not exclusively, with relations between the RFAs and IMF from 2000 to 2019, the two decades after recovery from the Asian financial crisis of 1997-98 until the onset of the Covid-19 recession.

As of 2020, eleven regional financial arrangements had emerged—a heterogeneous set of institutions ranging from the Latin American Reserve Fund (FLAR), which totals $4 billion, to the ESM, whose lending capacity is about €500 billion. As a consequence, financial rescue programs increasingly combine resources from two or more international financial institutions and official bilateral creditors. During 2014-2019, the IMF extended 85 loans, of which more than half were also associated with financing from other international financial institutions. Co-financing has become commonplace for large programs in particular: Virtually all of the 15 loan packages that exceeded $5 billion during those years involved substantial contributions from other institutions.Footnote10

The focus of the present analysis on the relationship between RFAs and the IMF stems from the firm distinction between short-term liquidity provision, on the one hand, and medium- and long-term financing for balance of payments and fiscal contingencies, on the other. Central bank swap agreements are occasionally activated prior to lending programs but are normally confined to facilitating trade settlement or liquidity provision. Medium- to long-term balance-of-payments financing to sovereigns, by contrast, requires risk-bearing commitments that must ultimately be backed by fiscal authorities and usually exact policy adjustments on the part of the borrower. Swap agreements might advertise large amounts to buoy confidence, but the actual activation of swaps is not automatic, and occurs less frequently and in much smaller amounts than advertised. Because central banks assiduously avoid risk, we can safely leave examination of their swaps to other studies and focus presently on the risk-bearing institutions that do the heavy lifting in sovereign contingencies.Footnote11

The increase in size and number of the regional arrangements raised questions as to whether they would cooperate or compete with the IMF and, to the extent they cooperate, the modalities for doing so and the consequences for borrowers and other stakeholders. Addressing such questions became particularly urgent during and after the euro crisis and experience with the troika. The IMF undertook stocktaking exercises and the G20 agreed upon a set of ‘Principles for Cooperation between the IMF and Regional Financing Arrangements’.Footnote12 For their part, the RFAs established their own dialogue separately from the IMF and produced reports on their relationships to the Fund that proposed modes of cooperation.Footnote13 Outside experts and blue-ribbon committees offered blueprints and proposals for bringing greater coherence to the global financial safety net.Footnote14 These efforts did not produce agreement on an architecture (authority and differentiation) for the global system, however; instead, the relationship of each RFA to the IMF evolved separately.

Meanwhile, the IMF itself was not standing still. Fund staff and management undertook numerous reforms to their lending instruments and guidelines on conditionality—including the introduction of the precautionary facilities—beginning shortly after the Asian financial crisis. Discontent with the IMF’s participation in the troika during the sovereign debt crisis of the euro area spurred another round of reviews,Footnote15 including of the Fund’s relationships with RFAs as well as its toolkit of financial facilities.Footnote16 IMF officials were motivated by the recognition that they could be called upon to cooperate with financial institutions in other regions with the same intensity with which they had collaborated with the European institutions in the euro crisis, and some of the new lending instruments were designed specifically to be acceptable to East Asian countries.Footnote17 Such adaptations by the Fund to the emergence of RFAs are therefore endogenous to regime complexity.

The IMF conducted a review of its relationships with the RFAs, published in 2017, in which staff laid out two overall visions for collaboration. Under the ‘lead agency’ model, the terms of co-financed programs would be organized around the IMF’s analysis of the macroeconomic framework and debt sustainability of the country concerned. Policy conditionality attached to financial assistance would follow from that analysis, to which the regional arrangement would defer. Under the ‘coherent program design’ model, the IMF and regional institutions would initiate ‘early engagement’ to head off outright conflicts over analysis on which both institutions claim a mandate and are unable to defer.Footnote18 IMF officials expect to follow the coherent program design model when cooperating with Europe but the lead agency model when cooperating with the other regional arrangements, at least in their present stage of development. The Fund staff also updated the G20 principles, rebranding them as the ‘Six Principles for Strengthening IMF-RFA Collaboration’.Footnote19

Fundamentally, states are not constrained by multilateral obligations when defining the relationship between their regional institutions and other crisis-financing institutions. Although the G20 has declared the IMF to be ‘at the center of the global financial safety net’, the phrase signals the focality of the institution but by no means authority over RFAs. Likewise, the G20 Principles and the IMF’s Six Principles that replaced them are, while indicative of consensus, hortatory. Nothing in IMF documents or their review by the Executive Board commits regional institutions or member states to respect either of the two collaboration models outlined in the 2017 review. The institutions understand that outright conflict can undermine adjustment programs and serving their members requires cooperation when institutions’ mandates overlap. But such incentives to cooperate, which are indeed pervasive, do not underpin any global norm or guidance for regional institutions to defer to the IMF. Certainly, there are no formal rules that structure the relationship among crisis-financing institutions generally.Footnote20

Instead, the relationship between the IMF and other crisis-financing institutions is defined regionally. As a practical matter, the institutions have usually defined their relationship in the course of prosecuting crises when financial turbulence struck their regions over the last two decades. Their choices established different relations of authority (hierarchy) and divisions of labor (differentiation) from one region to the next.

Comparison of three regional complexes

Compare, now, the regional complexes for East Asia, Latin America, and the euro area. This section presents each complex, drawing on the documentary record, lending activity, national policy responses, statistical analysis and interviews with officials in the institutions and national government agencies.Footnote21 Although some attention is devoted to the origins of the institutions, these regional cases focus mainly on 2000-2019, the period between the Asian financial crisis of 1997-98 and the disruptions of the Covid-19 pandemic. Earlier periods have been examined in depth elsewhere,Footnote22 while this period embraces the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-2009, the euro crisis of 2010-2015 and evolution of regional complexes, and thus rewards deeper comparative analysis than it has yet received.

Each subsection below treats the architecture of the regional complex and substantive outcomes. It traces the configuration of the RFA and its linkage with the IMF, including the roles of linchpin creditor countries, and assesses the degree to which the interinstitutional relationship is hierarchical and differentiated. These treatments locate each complex in the 2 × 2 matrix provided by the framework, as shown in , and assess whether substantive outcomes match the expectations of the theory for that quadrant.

East Asia

The regime complex for crisis finance in East Asia consists mainly of the two ASEAN+3 institutions, the Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralisation (CMIM) and ASEAN+3 Macroeconomic Research Office (AMRO), and the IMF.

Hierarchy without differentiation

Since the Asian financial crisis, the countries of ASEAN+3 (plus Hong Kong) have created the Chiang Mai Initiative (CMI) and then, in 2009, expanded it to establish CMIM.Footnote23 The purpose has been to provide supplemental financial assistance to the emerging-market economies in Southeast Asia. Japan and China, as linchpin creditors, led the development of the institution and, with South Korea, provide 80% of the financial resources and dominate the governing arrangements. With a total size of $240 billion, CMIM can lend up to $22.76 billion to its largest members, 3.5 times its quota at the IMF in the case of Indonesia.Footnote24

However, from the beginning, the basic objectives of the CMIM have been to address ‘liquidity difficulties in the region’ and ‘supplement the existing international financial arrangements’.Footnote25 As a consequence, most of the funds can be accessed only if the borrower also agrees to an IMF program and its conditionality—a provision known as the ‘IMF link’. The delinked portion (DLP) of these funds is currently 40% of these totals,Footnote26 or $9.1 billion in the case of Indonesia and the Philippines. In 2014, ASEAN+3 officials introduced a precautionary line into the CMIM, which paralleled the development of precautionary facilities at the Fund but maintained the IMF link.Footnote27

Because the original CMI had been inspired by antipathy toward the IMF after the 1997-98 crisis, the link has been contentious among the membership. The large creditor countries, Japan and China, have adhered to it while the Southeast Asian countries have objected, seeking to roll it back over time to establish a regional rescue vehicle that could operate more independently. It is important to note that the CMIM has never been activated, and the requirement that a borrower agree to a program with the IMF strongly discourages its use. Moreover, the ASEAN+3 finance ministers and central bank governors delayed increasing the delinked portion for years,Footnote28 which contributed to serious rifts with the Southeast Asian members.

Japan and China’s attachment to the link might surprise some scholars. Japan, after all, had proposed the creation of an Asian Monetary Fund (AMF) in 1997. As a rising economic superpower, China was expected by many to challenge the existing multilateral institutional order.Footnote29 Nevertheless, both countries have prioritized risk control through the link over independence for the regional arrangement. Japan has done so since the launch of the CMI in 2000. China’s position became more, not less, favorable toward the IMF link during the decade following the global financial crisis.Footnote30

China’s preference for the IMF link is rooted in its affinity for the IMF in general, notwithstanding the large shortfall in its vote share relative to its share of world GDP.Footnote31 First, the IMF has been a partner for the reformist wing in the domestic debate over economic development, which represents China in international organizations. Second, the IMF has adopted policies that align well with Chinese preferences: It refused to cite China for currency manipulation; incorporated the renminbi into the SDR basket, even though that step was arguably premature, fostering RMB internationalization; and warned against excessive domestic debt accumulation, a reformist priority. The Fund also increased staff hiring of Chinese nationals, not least of which included the appointment of a Deputy Managing Director. In these ways, Fund management has assiduously cultivated Chinese support.

Both key creditors remain skeptical of the region’s ability to independently design and implement an adjustment program for borrowing countries. ASEAN+3 took a major step forward when creating the ASEAN+3 Macroeconomic Research Office in 2011 and locating it in Singapore.Footnote32 In February 2016, the group upgraded the unit to a full-fledged public international organization.Footnote33 Its management and staff monitor and assess macroeconomic policies and financial soundness of members, identify vulnerabilities and recommend measures to mitigate risks, and brief the ASEAN+3 deputies and ministerial meetings. AMRO is also tasked with supporting members in the implementation and occasional reform of the CMIM.Footnote34 But, with about 65 staff members by 2019, AMRO remained relatively modest and had not been definitively delegated the critical task of serving as the analytical backstop for the financial facility.

AMRO and CMIM thus together cover a substantial share of the spectrum of capabilities covered by the IMF. CMIM can provide precautionary and regular arrangements that mirror those in the shorter half of the maturity spectrum offered by the Fund. AMRO surveillance covers similar macroeconomic and financial vulnerabilities as Fund Article IV consultations and shadows the Fund in the style of its published reports. IMF has comparative advantage in program design, but otherwise overlap is substantial; the region possesses a regime complex that is hierarchical and relatively undifferentiated.

Although the linchpin creditors of East Asia are regional rivals,Footnote35 their rivalry does not necessarily impede institutionalization. Japan and China competed for the favor of Southeast Asian countries in part by supporting ASEAN+3 institutions, while at the same time they share as creditors a common interest in conservative institutional design embodied in the IMF link. China adheres to the IMF despite being by far the most underrepresented country in the Fund,Footnote36 as measured by vote share relative to GDP share, in stark contradiction to the power-gap hypothesis.

Outcomes: institutional strategy and policy adjustment

We expect hierarchical-undifferentiated complexes to exhibit intermediate policy adjustment and, when key states are dissatisfied with existing institutional arrangements, regime shifting. Outcomes in East Asia correspond with these expectations, as shown by nonuse of CMIM, strategies pursued by dissatisfied states, and unilateral reserve accumulation.

The hierarchy of the complex, first of all, explains why CMIM has never been used. Southeast Asian countries consistently eschewed the IMF after the Asian financial crisis and creation of CMIM owing to its link to the Fund. It is highly probable, if not certain, that some of these countries, such as Indonesia, would have requested activation of CMIM during the 2008-2009 crisis and the 2014 taper tantrum in the absence of the IMF link.

Over the last two decades, second, Southeast Asian countries have accordingly pressed for an increase in CMIM’s delinked portion. Their efforts have been met with success, albeit delayed and limited: The DLP was raised from 10% (its original level) to 20% in 2005, and then to 30% in 2012. Notwithstanding broad agreement that it would be raised to 40% in 2014, the DLP remained at 30% for eight years until finally being elevated during the Covid-19 crisis in 2020.Footnote37 The reform represents modest regime shifting.

Third, as a consequence of institutional hierarchy, self-insurance has been the byword for governments in Southeast Asia. To avoid a repetition of their experience with the IMF during 1997-98, Southeast Asian governments’ first strategy was to pursue conservative macroeconomic policy, low (if not undervalued) currencies, and accumulate large quantities of foreign exchange reserves.Footnote38 The combined foreign exchange reserves of Southeast Asian countries exceeded $1 trillion in October 2020—well over one-third of the group’s GDP and far more than any other non-oil emerging-market region, including Latin America. Such reserves are resources that could have been invested in higher-yielding domestic projects and thus represent sacrifices in long-term growth that would have been unnecessary under a less hierarchical regional complex.

Latin America

The crisis-finance complex for Latin America comprises principally the IMF and the Latin American Reserve Fund (FLAR, by its Spanish acronym). In contrast to Europe and East Asia, the Latin American complex is missing a full-fledged RFA. Comprising only about 20% of the region’s GDP, FLAR has been more accurately described as a subregional financial arrangement.Footnote39 Older than either CMIM or the ESM, it is also much smaller, which restricts the scope of its activities, places direct competition with the IMF out of reach, and necessitates working in niches. Understanding the architecture of this complex helps to solve the puzzle of the absence of a genuinely regional arrangement.

Differentiation without hierarchy

In contrast to CMIM, FLAR maintains no formal link to the IMF. The FLAR agreement contains no reference to the IMF or any other international organization for that matter.Footnote40 Nor does FLAR apply policy conditionality to its financial support akin to the Fund’s, and it has very rarely denied a loan request, yet has been effectively accorded preferential status as a creditor by its members. It historically maintained a credit rating that was higher than the sovereign bonds of its members, situating it to mediate funds between the financial markets and members. Led by central bankers, FLAR’s lending decisions are made by a majority of six of the eight governors on its Board of Directors.

Size is critical to the functions that FLAR can perform and the role that it can play in the regional complex. FLAR’s subscribed capital, at slightly less than $4 billion, is roughly equal to the endowment of a medium-sized Ivy League university, and its annual budget, which was about $8 million in 2017, is about the size of a small- to medium-sized European think tank. Due diligence, economic analysis, and financial capacity are limited by this resource envelope. FLAR can provide liquidity to members in modest quantities, but countries that encounter more severe crises and require larger volumes of financing and deeper adjustment must turn to the IMF.

The membership of FLAR encompasses both economically heterodox and orthodox states, which accounts for their collective unwillingness to link or subordinate their institution to the IMF. While FLAR does offer medium-term balance of payments assistance, owing to its small size, it cannot compete with the IMF in terms of information gathering, analytic capacity, or financial resources. Moreover, it does not provide financing for government budgets directly. Instead, its comparative advantage lies in reserve management and medium-term liquidity provision.

In sum, although some of its programs have overlapped with those of the IMF and thus been economically influenced by them, FLAR does not explicitly defer to the Washington, DC-based institution. Differentiation enables the two institutions to coexist relatively harmoniously without the need for careful, explicit coordination.Footnote41 The relationship between them is thus non-hierarchical and substantially, though not entirely, differentiated.

Outcomes: policy adjustment and institutional strategy

Given its nonhierarchical-differentiated architecture, we expect the Latin American complex to exhibit intermediate policy adjustment and, when states become dissatisfied, competitive regime creation. We observe, accordingly, multiple initiatives to establish new institutional arrangements and a decidedly mixed record of policy adjustment that includes significant failure.

Lending from FLAR to the IMF from the eight member countries since 2000 can be grouped into the subperiods before and after the global financial crisis. There has been a roughly equal number of credit arrangements in the two subperiods, 14 before 2008 and 13 since that year. But there was a marked shift in the lending pattern: The IMF lent most often in the former period, yet not at all in the second period until the end of the decade.Footnote42

Given differentiation, we would not expect the availability of FLAR to borrowers to affect fiscal adjustment envisioned in IMF programs, and indeed we find no difference in this respect between FLAR and non-FLAR Latin American countries during this period.Footnote43 Consider nonetheless the loans extended to Costa Rica, Ecuador and Venezuela during the period when FLAR lent independently, 2009-2019.Footnote44 At $1 billion, the loan to Costa Rica was the largest and most straightforward, as it was repaid at the beginning of 2020. But Ecuador exhibited recidivism and restructured its debt to other creditors in 2020. Venezuela effectively defaulted on its loan to FLAR, which was resolved by writing down its capital position in the institution and thus reducing overall paid-in capital. This debacle, which damaged members’ confidence, would not have occurred if FLAR had been linked to the IMF. We can conclude that FLAR facilitated postponement of IMF program requests and associated economic adjustment and financed Venezuela to its detriment when the IMF would have refused.

Scaling up FLAR to make it a genuinely regional arrangement—let us call it a ‘Latin American Monetary Fund’—would entail inducting Brazil and/or Mexico. The region as a whole has sufficient reserves to back a robust arrangement. As of September 2020, foreign exchange reserves of Latin American countries totaled about $858 billion, of which Brazil held about $356 billion and Mexico $200 billion. (By comparison, the members of FLAR collectively held about $172 billion.) Expanding the membership of FLAR to these countries was proposed and actively considered during 2011-2015.Footnote45

Brazil and Mexico, however, would be creditors, not borrowers, within such a fund. Like linchpin creditors in other regions, these governments wanted reassurance that adjustment would be secured in programs in which it would be necessary to ensure, among other things, that loans would be repaid. Relatedly, they wanted FLAR to shift governance away from one-country-one-vote decision-making toward weighted voting and build a greater capacity to design, implement, and supervise adjustment programs.Footnote46 (In lieu of such capacity, a regional monetary fund could link to the IMF as other regional arrangements have done.) But none of these changes have so far been palatable to the current members of FLAR.Footnote47

Latin America thus exhibits a significantly greater tendency toward competitive regime creation than regime shifting. Absence of hierarchy permits, and differentiation requires, experimentation with alternative institutional arrangements when countries are dissatisfied with the IMF, even though such initiatives prove to be dead ends. FLAR is not privileged as a focus of innovation. The Banco del Sur, which Venezuela and Argentina originally proposed in 2007 as a crisis-lending organization as well as a development bank, is one good example.Footnote48 As its charter was negotiated, the provisions for financial stabilization were dropped at the insistence of Brazil.Footnote49 Hugo Chávez (Venezuela), Néstor Kirchner (Argentina), Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (Brazil), and four other leftist heads of government signed the scaled-back charter with great fanfare in September 2009, but the bank was never capitalized and never became operational. Whether voting shares should be weighted by the size of members’ contributions was a principal bone of contention.

Enlargement of the membership and resources of FLAR would have in principle constituted regime shifting. But the failure to attract the two large reserve holders demonstrated the rigidity of FLAR’s governing arrangements and how that rigidity redirects discontent toward competitive regime creation, even though such efforts have proven unfruitful. Its members have been unwilling to surrender the one-country-one-vote decision rule or countenance intrusive conditionality in programs. Without better prospects for reform, Brazil and Mexico fear recidivism or repetition of the Venezuelan effective default and have remained aloof like conservative creditors—which explains persistence of the distinctive aspects of the Latin American complex, the small size and subregional scope of the local arrangement.

Euro area

The euro crisis is the case of the most intensive competition and cooperation among international financial institutions, not only in this study but in the era of modern finance. The rescue programs were executed by the ‘troika’, composed of the IMF, European Commission, and the European Central Bank (ECB). To these we must add the Eurogroup, the European Council, and the European Stability Mechanism.

These institutions collaborated in providing loan packages for the crisis-stricken countries and defining the policy reforms that would be exacted from borrowing governments. Between late 2009 and the middle of 2015, five countries succumbed to the crisis, secured financial assistance from the European partners and the IMF, and underwent severe economic adjustment. (Table A5.7, Supplementary Material). A sixth, Italy, managed to escape having to secure financial assistance but nonetheless suffered a prolonged period of economic stagnation.Footnote50

There was some variation in the institutional mix over the course of the seven country programs. The ESM was introduced into the mix after its establishment in 2012. The IMF did not make a financial contribution to the package in the cases of Spain and the third Greek program. But even in those cases, the IMF continued to participate in the troika, shaping the program, defining conditions, and monitoring implementation and follow-through once the program was concluded. Despite discontent among the institutions themselves, the troika arrangement was replicated from one program to the next.

Overlap without hierarchy

European officials deliberated extensively over the institutional form of the financial rescues during the crisis. They confronted two principal questions: (i) how to evolve the institutions of the euro area and, (ii) whether to include the IMF in the rescue programs. Northern countries anticipated being creditors under these arrangements, and Germany had become disillusioned with the Commission on several macroeconomic and financial matters and regarded it as an unreliable agent for negotiating lending programs. Significant distrust of the Commission, which oversaw both sides in the debtor-creditor conflict, was effectively baked into the institutional arrangements of the euro area. Although the Commission’s involvement in program design was regarded as necessary, that distrust was pivotal in deciding both questions.

With respect to the role of the IMF, European policymakers initially supported a ‘go it alone’ strategy almost unanimously. European governments had the resources, personnel, and analytical capacity to design financial rescue programs, and they had done so on four (albeit less challenging) occasions during the 1980s and 1990s without the IMF. But Chancellor Angela Merkel, leader of the indispensable linchpin creditor, insisted on including the IMF and thus forming the troika for the first Greek program—and the Fund’s inclusion was repeated for the subsequent programs.Footnote51

Euro area member states chose to constitute the rescue facilities mainly by means of an intergovernmental treaty, separate from the EU treaties but linked to them in a number of ways, including by ‘borrowing’ the European institutions for various functions. Those functions included analysis and design of rescue programs—not alone, but rather in close conjunction with the ECB and the IMF.Footnote52 Those facilities included the European Financial Stability Mechanism, European Financial Stability Facility, and finally the permanent ESM, constituted by its own treaty. With lending capacity of €500 billion, the ESM funded programs for Spain, Cyprus and Greece’s third rescue.Footnote53

The European complex has in the ESM a fund that can devote more financial resources to euro-area rescues than the IMF and a lending toolkit that is more versatile than the Washington, DC-based institution. In addition to the standard macroeconomic stabilization, precautionary, and emergency tools, the ESM can purchase government bonds in the primary and secondary markets (Table A5.9, Supplementary Materials). As of 2013, its Managing Director, Klaus Regling, could advocate jettisoning the IMF from the troika, arguing that the euro area already possessed the functional equivalent of a full-fledged European monetary fund, with the functions dispersed across the Commission, ESM, and ECB.Footnote54

Retaining the IMF in one fashion or another in all of the programs was thus a political decision on the part of creditors to control drift on the part of the Commission rather than a functional necessity born of any gaps in European facilities (discussed further in the section on institutional collaboration, below). Although it possessed broader expertise in program design, the Fund’s technical and financial capabilities were largely duplicative. The choice of the intergovernmental approach to establishing the new facilities ensured that decisions on financial assistance would be made by unanimity, which enabled Germany to insist on including the Fund as a condition for approving financial assistance.

While they considered the matter at length, however, European governments refused to establish a hierarchy among the institutions. The Fund’s involvement in the troika did not grant it any authority to direct the work of regional institutions either formally or informally. Far from dominating the European institutions, the IMF was criticized by its own staff and outside observers for being too deferential to them during the first two years of the euro crisis.Footnote55 Although the participation of the IMF is to be sought when providing financial assistance, euro area member states deliberately declined to require it in the ESM treaty.Footnote56 Moreover, European officials openly questioned the preferred creditor status of the IMF.Footnote57 These touchstones indicate equality, not hierarchy, in relations between the IMF and European institutions.

Outcomes: institutional strategy and policy adjustment

What outcomes have institutions’ relatively equal authority and substantive overlap produced? We observe both regime shifting and regime creation in the euro area’s complex, which is consistent with expectations. Regime shifting took the form of rolling back the financial participation of the IMF in financial programs in favor of the ESM, relying more heavily on the ESM and the Commission for debt sustainability analysis, and re-designating the division of labor between those two European institutions through memoranda of understanding.Footnote58 Regime creation took the form of establishing the ESM and other new facilities, negotiating amendments to its founding treaty.

With respect to policy adjustment, however, the expectation of the framework theory is exceeded. Rather than high rule conflict, endemic forum shopping, and feeble policy discipline, as we expect in nonhierarchical-undifferentiated complexes, we find that the troika was highly effective in imposing adjustment on borrowers, which it enforced through strict monitoring. The scope and number of policy conditions was unprecedented, and the magnitude of the fiscal correction was very large—averaging 5.1% of GDP on a cyclically adjustment basis for the five program countries, much larger than adjustment in Latin American programs—and in some cases draconian.Footnote59 Greece is the case that proves the rule: Despite the absence of a reliable parliamentary majority for reforms, and repeated slippage on their implementation, the country was ultimately unable to avoid a punishing austerity. In no program case was the borrower able to effectively play one creditor off against the other, preemption of which being a paramount purpose of the troika.

Comparison

These regional cases underscore the role of linchpin-creditor countries and their preferences’ alignment with IMF policies for the choice of authority and differentiation between that multilateral institution and the RFA.Footnote60 Interestingly, though, the institutional arrangements inherited from earlier decades constrained linchpins’ ability to subordinate the RFA to the Fund. China and Japan were least constrained by such arrangements and could thus link CMIM to the IMF. Brazil and Mexico, as non-members, lacked the leverage to do so, and FLAR thus remained aloof and sought to differentiate itself from the Fund. Meanwhile, the corpus of EU treaties and legislation precluded subordinating European institutions to the Fund notwithstanding a great deal of functional overlap. Different architectures emerged in each regional complex as a result, and in a manner at odds with the power-gap hypothesis: The most under-represented country and region, China and East Asia, subordinate their regional institution to the IMF, while the over-represented region, the euro area, does not.

These different architectures were associated with distinctly different degrees of policy adjustment and institutional strategy, manifesting variously across regions. compares our framework’s expectations to the observed outcomes during the period 2000-2019. Where relations between the RFA and IMF were hierarchical-undifferentiated (East Asia) and nonhierarchical-differentiated (Latin America), we see intermediate levels of adjustment, skewing positively with hierarchy and negatively in its absence, and a tendency toward regime shifting and creation respectively. The nonhierarchical-undifferentiated case (euro area) exhibited both regime shifting and creation. Outcomes thus generally match expectations well, providing solid support for the theory that frames this special issue. However, institutional-strategy outcomes match expectations better than policy-adjustment outcomes in the nonhierarchical-differentiated case: The framework underpredicts adjustment in the euro crisis lending programs—a gap that is explained by institutional collaboration in the section below.

Table 1. Comparison of theoretically expected and observed outcomes.

What confidence can we have that this overall confirming association is causal and not simply the (endogenous) consequence of linchpins’ preferences? Significant correspondence between those preferences and ultimate outcomes is not inconsistent with our expectations, but process tracing provides substantial evidence that the architecture of complexes also intervenes. First, state preferences were sometimes themselves shaped by the contours of the institutions: The establishment of CMIM shifted South Korea’s perspective from that of a debtor toward that of a creditor, for example, and the establishment of AMRO persuaded Japan to loosen the CMIM’s link to the Fund. The IMF’s presence in the troika, to cite another example, was critically important to constructing and maintaining the coalition in the German Bundestag that supported the Greek programs; without it, those programs would have been in serious jeopardy. Second, as mentioned, these states were constrained in their ability to modify institutions to their preferences by the institutional arrangements inherited from preceding decades.Footnote61 Finally, linchpin countries failed to correctly anticipate the stances adopted by institutions and policy outcomes on several occasions. The IMF’s lenience toward Ireland and Greece relative to the postures of the ECB and Commission surprised Berlin, and Venezuela’s effective default certainly surprised most FLAR member states. We can safely conclude that substantive outcomes were not the un-refracted consequence of linchpin-country preferences ‘all the way through’ the causal chain.

Institutional collaboration

While authority and differentiation are fundamental to explaining cooperation and policy outcomes, they alone do not provide a complete explanation in the European complex. Collaboration among the institutions can fill the explanatory gap, however, specifically with respect to the severity of policy adjustment.Footnote62 Collaboration is defined here simply as cooperation among institutions and can take the form of exchanges of information, coordination of operations, harmonization of rules, and other activities that advance their goals.Footnote63

Collaboration has both a dependent and explanatory side. It is dependent on choices made about the relationship between the institutions. Collaboration is unnecessary when institutions are fully differentiated, for example. With differentiation, a state of harmony prevails among institutions in which conflicts cannot arise for which collaboration would be useful in addressing.Footnote64 Overlap, on the other hand, creates a substantive need for collaboration, which is particularly feasible when institutions are arrayed hierarchically. When deciding to create undifferentiated institutions, states could well foresee the need for and facilitate collaboration by granting one institution the right and wherewithal to coordinate the work of the institutional group.

However, as we have seen in the euro crisis, there remain instances when states (and other actors) create functionally overlapping institutions and want them to cooperate, without at the same time wishing to confer authority on one institution over the others. Under such circumstances, states can create a complex without hierarchy but with mechanisms of collaboration, which can be formal (mandated in founding charters) or informal (guided by member states through their interventions in boards of governors and executive boards, or directly with secretariats). Principals’ decisions on hierarchy and differentiation can be separated from decisions on collaboration. Collaboration derives from principals’ preferences directly, in these cases, and affects ultimate outcomes without necessarily passing through hierarchy or differentiation.

States’ concern to preserve control over institutions and substantive outcomes can favor such a strategy. When states introduce new or existing institutions into a regime complex in order to better control agency drift, inter-institutional conflict can be part of the control mechanism (Henning Citation2017a, 33-34, 242-243). When institutions arrive at impasses, key states mediate these disputes and, in the process, tilt outcomes toward their preferences. Mediation is thus one way in which key states maintain control, and as a consequence they under-invest in mechanisms that might otherwise anticipate and resolve institutional conflict ex ante.

Such a strategy, which we can call ‘complexity for control’, further illuminates why states often prefer institutions to collaborate without establishing hierarchy among them. Designating one institution as authoritative would not only signal ex ante which should prevail in a dispute but also disintermediate principals whose intervention would otherwise be needed to resolve conflict ex post, elevate the secretariat of the peak institution, and thereby risk enabling a ‘rogue’ agent. Key states and other principals must have a high degree of confidence in their direct control of the peak institution through its governing bodies to establish such a hierarchy, which is often not realistic. Moreover, states and other principals might agree that institutions should cooperate but nonetheless disagree over whether authority should be conferred on one institution over others or which institution that should be.

In the euro crisis, therefore, institutional collaboration reconciles strong policy adjustment with the nonhierarchial-undifferentiated architecture of the regional complex. Key creditor states had been unwilling to grant one institution authority over others in the troika, but sponsored and monitored collaboration among them, effectively preempting forum shopping on the part of borrowers. Collaboration was sometimes fraught, but key creditor states mediated institutions through episodes of temporary deadlock.Footnote65 Because they were successful, moreover, Germany and its partners adhered to this architecture notwithstanding widespread dissatisfaction with the troika.

Because the quest for control is pervasive, and establishing hierarchy within a complex threatens to weaken it by increasing principals’ dependence on one institution, we would expect principals to solve problems of overlap through collaboration reasonably frequently in global governance. By introducing collaboration as a supplementary causal variable, therefore, we can explain outcomes more precisely than by relying on hierarchy and differentiation alone.

Conclusion

This study reviews the architectures of regime complexes for crisis finance in East Asia, Latin America and the euro area during 2000-2019, defined by relations of hierarchy and differentiation between the RFA and IMF in each region, and outcomes in terms of policy adjustment, regime shifting and creation, and subsequent evolution of the complex. It finds that complex architecture is consequential for such outcomes and provides solid support for the framework theory in most cases. Where policy adjustment exceeded levels anticipated by the theory, the European case, institutional collaboration fills the explanatory gap, and the paper develops it as a supplement to the framework. Collaboration solves problems of overlap while allowing key states to better maintain control over the institutions. None of these interactions could be productively explored within a singular institutionalist approach.

The hierarchy-differentiation framework can help us better understand the evolution of regime complexes over time, a third stage of analysis of regime complexity. Once established, the architectures of regional complexes altered the choices available for deepening them even decades later. Where the local institution is independent from the IMF, as in Latin America, linchpin creditors withheld resources and the RFA languished as a subregional institution and avoided collisions with the Fund. Where the local institution is subordinated to the IMF, as in East Asia, creditor states devote more resources to it, although the facility is unattractive to borrowers and thus remains underutilized. Where regional creditors have not subordinated their local institutions but can nonetheless effectively coordinate them with the IMF, as in the euro area, regional institutions are granted substantial new resources that are drawn by borrowers and the arrangements evolve in a sophisticated manner.

Comparison with East Asia provides insight into the counterfactual scenario for Latin America, had an IMF link been in place in that regional complex. The ASEAN Swap Arrangement (ASA) and FLAR were both created as subregional arrangements in the late 1970s with roughly equivalent resources. When Southeast Asians became alienated from the IMF in the 1990s, ASEAN+3 expanded upon the ASA to launch its full East Asian arrangement, the CMI. But CMI was allowed to go forward only because it was linked to the IMF. With the link, Japan and China had the confidence they required as creditors to contribute to the full-fledged regional facility; without it, by contrast, the existing arrangement in Latin America languished. Governance of FLAR and its relationship to the IMF constrained the choices available to Brazil and Mexico, making enlargement of FLAR to encompass the full region unattractive, and are thus largely responsible for the disappointing trajectory of that regional complex.

The argument advanced here goes well beyond the claim that institutions matter in international relations and even beyond the separate claim that multiple institutions are needed to explain outcomes in most issue areas. This study advances a theoretical framework that focuses analysis on the causal implications of the relationship and interaction among the institutions—the architecture of regime complexes—and demonstrates that these are impactful in crisis finance. That architecture, captured analytically by the dimensions of hierarchy and differentiation, produces outcomes that vary from the simple sum of the effects of institutions considered in isolation—a principal proposition of regime complexity theory.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (1.8 MB)Acknowledgements

This article is prepared for the special issue on International Regime Complexity, organized by the author and Tyler Pratt. Previously, it was presented to the project workshops at American University, Washington, DC, July 16-17, 2020, and Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, December 10-11, 2020, and at the APSA annual meetings, Seattle, October 3, 2021, and the workshop ‘Linking IO Authority and Overlap’, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, May 25-26, 2022. The manuscript benefits substantially from comments from James Boughton, Ricky Clark, Jeffrey Colgan, Christina Davis, Tamar Gutner, Stephanie Hofmann, Ayse Kaya Orloff, Tyler Pratt, Miles Kahler, Phillip Lipscy, Louis Pauly, Melanie Ram, Bernhard Reinsberg, Henning Schmidtke, Duncan Snidal, Oliver Westerwinter, Qi Zhang, and other participants in the meetings to which it has been presented, three anonymous reviewers and the journal’s editorial team. Sahil Mathur provided excellent research support and insightful comments. Analysis draws significantly upon research generously supported by the Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

C. Randall Henning

C. Randall Henning is Professor of International Economic Relations at the School of International Service at American University in Washington, DC.

Notes

1 Henning and Pratt (Citation2023).

2 Reviews of the literature on regime complexity can be found in Henning and Pratt (Citation2023), Alter (Citation2022) and Eilstrup-Sangiovanni and Westerwinter (Citation2022), among other places.

3 Authority reflects “the extent to which institutions implicitly or explicitly recognize the right of other institutions to craft definitive rules, organize common projects, or otherwise set the terms of cooperation” and ranges from complete nonhierarchy to extreme hierarchy. Differentiation describes the extent to which institutions vary in the functions they perform. See, Henning and Pratt (Citation2023), which cites in turn Lake (Citation2009), Zürn and Faude (Citation2013), and Mattern and Zarakol (Citation2016). Appendix 1 of the Supplementary Materials addresses the operationalization of these variables.

4 Henning (Citation2017a, Citation2019).

5 See, Tammen, Kugler and Lemke (Citation2017), drawing on Organski (Citation1968), and Zangl et al. (Citation2016), among others.

6 Pratt (Citation2021) and Lipscy (Citation2015) address this argument.

7 Lütz (Citation2021) similarly examines the interface between regional and global institutions.

8 Although RFAs maintain a dialogue in which they compare notes and exchange views (Cheng, Miernik, & Turani Citation2020), it does not structure their relationships with the Fund or coordinate lending activities.

9 “Regional financial arrangements” refers to individual institutions, not to the complexes themselves, in keeping with convention in international financial discourse. For comparisons of RFAs, see, also, Henning (Citation2020), Kring and Gallagher (Citation2019), Krampf and Fritz (Citation2015), and Clark (Citation2022).

10 Calculated from information provided by the Monitoring Financial Arrangements (MONA) database of the IMF, program documents, and RFA reports.

11 Readers interested in central bank swaps can consult, among others, McDowell (Citation2017), Sahasrabuddhe (Citation2019), and Henning (Citation2015).

12 Miyoshi et al. (Citation2013) and Group of Twenty (Citation2011).

13 Supra, note 8.

14 See, for example, G20 Eminent Persons Group (Citation2018).

15 Independent Evaluation Office (Citation2016).

16 See, especially, IMF (Citation2017a, Citation2017b, Citation2017c).

17 In 2010, Fund staff proposed that several Southeast Asian countries request joint qualification for its new Precautionary Credit Line, a precursor to the Precautionary and Liquidity Line, though was in the end unsuccessful. Interviews with IMF officials, Washington, D.C., November 22, 2016, and March 6 and September 24, 2018, and Southeast Asian officials, Singapore, October 2, 2018.

18 See IMF (Citation2017a, pp. 2, 17, Box 3). In no case would the Executive Board of the IMF accept the lead of one of the RFAs in jointly financed programs.

19 IMF (Citation2017c).

20 States systematically underinvest in rules and mechanisms for ex ante coordination of institutions in order to retain control. Henning (Citation2017a; 34, 242-43).

21 A list of interviews and discussion of method appear in Supplementary Material Appendix 2.

22 Earlier developments are treated in the historical work cited.

23 See, among others, Grimes and Kring (Citation2020), Katada (Citation2012), Kawai (Citation2015), Henning (Citation2017b), Pitakdumrongkit (Citation2016), and Lipscy (Citation2003).

24 Greater in the case of the Philippines. See Table A5.1, Supplementary Materials.

25 “Key Points of CMI Multilateralisation Agreement,” Joint Media Statement of the ASEAN Plus Three Finance Ministers’ Meeting, Annex 1, Bali, Indonesia, May 3, 2009, paragraph 1.

26 ASEAN+3 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors (Citation2020, pp. 2–3).

27 See Henning (Citation2015) and IMF (Citation2017a).

28 See, ASEAN+3 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors (Citation2017, Citation2018) and Khor (Citation2017).

29 Relatedly, see, Kahler (Citation2013).

30 See, for example, Ministry of Finance of the People’s Republic of China (Citation2016) and Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China (Citation2017). Corroborated by interviews with a Chinese official, Beijing, December 13, 2016, Asian creditor-country official, Washington, D.C., October 13, 2017, and IMF official, Washington, D.C., November 14, 2018.

31 China’s share is 6.08 percent of total votes, Japan’s 6.15 percent, and United States’ 16.51 percent.

32 See Chabchitrchaidol, Nakagawa, and Nemoto (Citation2018).

33 See AMRO (Citation2016a, Citation2017a).

34 See AMRO (Citation2016b). On the evolution of AMRO, see, also, Grimes and Kring (Citation2020), and Katada and Nemoto (Citation2021). On earlier evolution of IMF surveillance, see, Pauly (Citation2008).

35 Cohen (Citation2012).

36 China alone accounts for more than half of the total under-representation of members in the IMF. IMF (Citation2018).

37 Kawai (Citation2015, 13-16); ASEAN+3 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors (2020).

38 Lipscy and Na-Kyung Lee(Citation2019); Ito (Citation2012).

39 See, Table A5.2, Supplementary Material.

40 FLAR (Citation2017).

41 Interviews with Latin American officials, Bali, Indonesia, October 10, 2018, and an IMF official, Washington, D.C., November 9, 2018.

42 Table A5.3 in Supplementary Materials displays loans to the eight FLAR members since 2000.

43 Or in the size of fiscal deficits at the outset or amount of adjustment over the course of programs. Statistical comparisons and tests of significance are shown in Tables A5.4 and A5.5 and Appendix 6, Supplementary Material.

44 Details of these cases are presented in Appendix 3, Supplementary Materials.

45 Interviews with a former Mexican official, December 2, 2020; a Mexican official, February 26, 2021; and a Brazilian official, March 11, 2021.

46 Ibid.

47 Interviews with a former Colombian official, Washington, D.C., April 10, 2019, and online, November 9, 2020; two Latin American officials, online, November 24, 2020; and a former Mexican official, online, December 2, 2020.

48 Negotiations soon included Bolivia, Paraguay, Uruguay, Brazil, and Ecuador, the latter being particularly supportive of including the financial stabilization function. Rosales (Citation2013). See, also, Rosales (Citation2010, 5-6).

49 Henderson and Clarkson (Citation2016).

50 The extensive literature on the euro crisis also includes Pisani-Ferry, Sapir, and Wolff (Citation2013), Matthijs and Blyth (Citation2015), Jones, Kelemen, and Meunier (Citation2016), Caporaso and Rhodes (Citation2016), Véron (Citation2016), Kincaid (Citation2016), Schelkle (Citation2017), Moschella (Citation2020) and d’Erman, Schure, and Verdun (Citation2020).

51 Henning (Citation2017a) and Supplementary Material Appendix 4.

52 We confine our consideration of the ECB to its role in the troika because it was only in that (advisory) capacity that the central bank was involved in sovereign crisis finance. A prohibition on lending to governments, "monetary financing," is one of the supreme principles of the ECB. The ECB instead lent to the banking system, which naturally had ramifications for the fiscal sustainability of sovereigns. But, to safeguard its independence, the ECB took great pains to separate its monetary operations from the lending conducted by the euro area financial facilities, Commission and IMF to stricken governments. Similarly, the ECB’s activation of its swap with the Federal Reserve provided dollar liquidity to European banks rather than financing for governments.

53 See Supplementary Material Appendix 4 and Table A5.8.

54 “Europe Can Handle Future Crises without IMF – Bailout Fund Chief,” Reuters, August 28, 2015.

55 Independent Evaluation Office (Citation2016).

56 Henning (Citation2017a, 174-77).

57 Interviews with a former Greek official, Cambridge, Massachusetts, August 1, 2012; a German official, Berlin, July 15, 2017; and a European official, Luxembourg, July 19, 2018. See, also, Appendix 4, Supplementary Materials.

58 “Joint Position of the European Commission and the European Stability Mechanism on Their Future Cooperation,” Brussels, November 4, 2018, at https://ec.europa.eu.

59 See, Table A5.10, Appendix 5, Supplemental Materials. Greece alone improved its cyclically adjusted balance by 12.9 percent of GDP, while the average fiscal adjustment of non-program countries in the euro area was much smaller, 2.9 percent of GDP.

60 Compare to Mühlich and Fritz (Citation2021) and Clark (Citation2021), for example.

61 Heldt and Schmidtke (Citation2019) and Hanrieder (Citation2015), for example, emphasize path dependency.

62 On collaboration, see, Zürn and Faude (Citation2013), Clarke (2022) and Westerwinter (Citation2022).

63 Such activities also include exchange of observer status in working groups and governing bodies, mutual recognition of standards and practices, joint missions to member countries, common programs, collective decision-making, and dispute resolution procedures.

64 See Keohane’s (Citation1984, 51-55) discussion of harmony and cooperation.

65 Chancellor Merkel’s convening of the heads of the three institutions in Berlin on June 1, 2015, to resolve conflict over the third Greek program is one such instance among many.

References

- Alter, K. (2022). The promise and perils of theorizing international regime complexity in an evolving world. The Review of International Organizations, 17(2), 375–396. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-021-09448-8

- AMRO. (2016a). Agreement Establishing ASEAN+3 Macroeconomic Research Office (‘AMRO’). Singapore, April. https://www.amro-asia.org/amro-agreement/.

- AMRO. (2016b). Key Points of the CMIM Agreement. Singapore, April. https://www.amro-asia.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/For-web-updating-Key-Points-of-the-CMIM-Agreement.pdf (accessed December 3, 2020).

- AMRO. (2017a). Annual Report 2016.

- ASEAN+3 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors. (2017). Joint Statement of the 20th Meeting. Yokohama, Japan, May 5.

- ASEAN+3 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors. (2018). Joint Statement of the 21st Meeting. Manila, Philippines, May 4.

- ASEAN+3 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors. (2020). Joint Statement of the 23rd Meeting. Virtual format, September 18.

- Caporaso, J., & Rhodes, M. (Eds.). (2016). The political and economic dynamics of the Eurozone crisis. Oxford University Press.

- Chabchitrchaidol, A., Nakagawa, S., & Nemoto, Y. (2018). Quest for financial stability in East Asia: Establishment of an independent surveillance unit ‘AMRO’ and its future challenges. Public Policy Review, (Policy Research Institute, Ministry of Finance, Japan), 13(4), 1–16.

- Cheng, G., Miernik, D., & Turani, T. (2020). Finding complementarities in IMF and RFA toolkits. ESM Discussion Paper No. 8. European Stability Mechanism.

- Clark, R. (2021). Pool or duel? Cooperation and competition among international organizations. International Organization, 75(4), 1133–1153. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818321000229

- Clark, R. (2022). Bargain down or shop around? Outside options and IMF conditionality. The Journal of Politics, 84(3), 1791–1805. https://doi.org/10.1086/719269

- Cohen, B. (2012). Finance and Security in East Asia. In A. Goldstein and E. Mansfield (Eds.), The Nexus of economics, security, and international relations in East Asia (pp. 39–65). Stanford University Press.

- d’Erman, V., Schure, P., & Verdun, A. (2020). Introduction to ‘economic and financial governance in the European Union after a decade of economic and political crises. Journal of Economic Policy Reform, 23(3), 267–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/17487870.2020.1762599

- Eilstrup-Sangiovanni, M., & Westerwinter, O. (2022). The global governance complexity cube: Varieties of institutional complexity in global governance. The Review of International Organizations, 17(2), 233–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-021-09449-7

- FLAR. (2017). Convenio Constitutivo (edición no. 19). Bogotá.

- G20 EPG [Eminent Persons Group]. (2018). Making the global financial system work for all. Report of the G20 Eminent Persons Group on Global Financial Governance. www.globalfinancialgovernance.org.

- Gómez-Mera, L. (2015). International regime complexity and regional governance: Evidence from the Americas. Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations, 21(1), 19–42. https://doi.org/10.1163/19426720-02101004

- Grimes, W., & Kring, W. (2020). Institutionalizing financial cooperation in East Asia: AMRO and the future of the Chiang Mai initiative multilateralization. Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations, 26(3), 428–448. https://doi.org/10.1163/19426720-02603005

- Group of Twenty. (2011). G20 Principles for Cooperation between the IMF and Regional Financing Arrangements. Paris, October 15.

- Haftel, Y., & Hofmann, S. (2017). Institutional authority and security cooperation within regional economic organizations. Journal of Peace Research, 54(4), 484–498. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343316675908

- Haftel, Y., & Lenz, T. (2020). Organizational complexity and regional authority: Africa and Latin America compared. Paper presented to the Barcelona Workshop on Global Governance. January 23–24.

- Hanrieder, T. (2015). International organization in time: Fragmentation and reform. Oxford University Press.

- Heldt, E., & Schmidtke, H. (2019). Explaining coherence in international regime complexes: How the World Bank shapes the field of multilateral development finance. Review of International Political Economy, 26(6), 1160–1186. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2019.1631205

- Henderson, J., & Clarkson, S. (2016). International public finance and the rise of Brazil: Comparing Brazil’s use of ergionalism with its unilateralism and bilateralism. Latin American Research Review, 51(4), 43–61. https://doi.org/10.1353/lar.2016.0048

- Henning, C. R. (2015). The global liquidity safety net: Institutional cooperation on precautionary facilities and central bank swaps. New Thinking and the New G20 Paper No. 5. Centre for International Governance Innovation.

- Henning, C. R. (2017a). Tangled governance: International regime complexity, the Troika, and the Euro Crisis. Oxford University Press.

- Henning, C. R. (2017b). Avoiding fragmentation of global financial governance. Global Policy, 8(1), 101–106. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12394

- Henning, C. R. (2019). Regime complexity and the institutions of crisis and development finance. Development and Change, 50(1): 24–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12472