Abstract

As in other countries, regulated savings in France are intricately woven into dense regulatory frameworks driven by explicit governmental objectives. The anticipated marketization of the French economy should have eradicated them; however, a substantial portion of regulated savings has managed to evade this process. Is this phenomenon attributable to the tenacious grip of the French state-led tradition? Not entirely, as another subset of these savings has indeed undergone marketization. The landscape of French regulated savings is notably distinguished by a growing dichotomy: on one side, non-marketized products offered by banks, and on the other, increasingly marketized products provided by insurers. Drawing upon process tracing, we contend that these ostensibly conflicting developments emanate from the distinct and precise institutional dependencies between state and private actors in which these products are enmeshed. The prevailing status quo within the banking sector is owed to banks’ engagement in a mutually advantageous, long-term exchange of favors with state actors. Faced with the trade-off between offering less lucrative products and risking the endangerment of this relationship, banks have opted for the former. In contrast, an assertive strategy has gained traction in the insurance industry. Yet, strategies for the marketization of regulated savings aligned with state priorities have been implemented, even when insurers expressed opposition.

Introduction

A sizeable array of term and savings deposits offered by the financial industry are embedded into dense regulatory settings. The features and the market share of these products vary both within and across countries—but despite their diversity, these ‘regulated savings’ share two essential commonalities. First, they are all subjected to sustained and prolonged state intervention on their pricing, return, liquidity and fiscal regime. Second (though relatedly), the creation of these products does not emanate from the private sector itself, but is instead motivated by some explicit governmental objectives. Hence, and in addition to protecting people’s savings, they may aim at financing large-scale public programs, small and medium-sized enterprises, social housing or the ecological transition, among many possible others. Prominent examples include Postal saving schemes that have existed in high income countries since the nineteenth century—as Italy’s Libretti di risparmio postale created in 1876 or France’s Livret de caisse d’épargne, which dates back to 1818. In various emerging economies like India, they are still crucial devices for rural communities that have limited access to the banking system. Regulated savings, particularly on the most recent period, may have also been integrated into broader ‘asset-based welfare’ policy strategies to encourage individuals to accumulate assets to meet their future welfare needs (Hay & Benoît, Citation2023). In this context, they might include several retail investment arrangements, like British Individual savings accounts, as well as less liquid (and possibly riskier) life insurance schemes. Arguably, several types of related retirement and pension plans also fall into that broad category.Footnote1

Overall, that regulated savings play a substantial role in various countries is widely acknowledged. Given their wide diffusion and their accessibility, they are also regularly scrutinized by non-academic experts and various media outlets. Yet, political economists have rarely investigated these various products as a unified category. Notably, and while there is an extensive literature on the financialization of private retirement accounts in Europe (e.g. Naczyk & Palier, Citation2014; van der Zwan, Citation2017), not much has been written about the tensions between other kinds of regulated savings and their mutual (or contrasted) developments. By documenting recent (non-) changes that have affected different categories of regulated savings in France through a cohesive comparative lens, this paper constitutes an early effort at filling this gap—and, conceptually, an attempt at reflecting on the broader (and somewhat unnoticed) implications the study of these products tells about the polymorphism of state involvement in the financial sector.

Empirically, we are primarily concerned with characterizing and accounting for an important trend that has occurred in the area of French regulated savings over the last ten years. During this period, policymakers have sought to increase the return and the profitability of a series of products mostly offered by insurance companies. This was done through merging existing schemes while softening their regulatory and fiscal regime—eventually leading to their increasing marketization. By contrast, despite some reform in the collection and uses of regulated savings offered by banks, the status quo has prevailed in this sector, in the sense that they have remained completely insulated from marketized logics despite their poor or negative profitability. Overall, we thus observe a growing segmentation between banks’ non-marketized and insurers’ increasingly marketized regulated savings—and more generally, a puzzling situation that we believe is hardly specific to the case under study.

The return (or the persistence) of an extensive state intervention coupled with the simultaneous deepening of marketization or financialization is indeed a paradoxical (yet recurring) feature of present-day capitalism, especially since the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) (van Apeldoorn et al., Citation2012). In recent years, a buoyant literature on ‘state capitalism’ has started tackling this paradox. It has notably shown that this phenomenon spares no political economies both in the Global North and in the Global South (Babić, 2021), and has further confirmed that state capitalism was ‘hardly monolithic’ as it came with various instruments, goals, and state-private interactions (Kurlantzick, Citation2016).

In order to explore further the role of the state in shaping contemporary capitalism, it makes particular sense to examine regulated savings. People’s savings have existed in diverse modalities and have been regulated differently across countries and time. In Germany, for example, the public and the savings banks are in charge of savers’ savings accounts and are required by law to use these funds for the development of the region in which they are based, and are known to have close relationships to local governments, which use them to fulfill electoral or political objectives (Choulet, Citation2016; Krahnen & Schmidt, Citation2004; Markgraf & Rosas, Citation2019; Massoc, Citation2020, Citation2021). In the UK, retail savings have followed a market-based approach and been open to competition between banks in the aftermath of the Sandler reform of 2002. They have since then developed in parallel with privately managed pensions products, largely used by savers (Littler & Hudson, Citation2003; Slattery & Nellis, Citation2005).

However, in a context of growing geo-political tensions and where states follow (green) industrial policy, across the globe, governments have sought available ways to mobilise private capital in order to fulfill explicit political priorities (Alami et al., Citation2021; Massoc, Citation2022a; Mazzucato, Citation2013). Of particular interest for this paper, government officials have started looking at how retail savings could be mobilised more actively in the pursuit of industrial policy’s objectives. It is from that point of view revealing that an EU delegation led by a team from the Ministry of Finance was recently sent to the French Caisse des Dépôts in order to explore how regulated savings operated in France.Footnote2 In that sense, it can be argued that France is no longer deviant or an outlier as often understood in the CPE literature, but should be seen as an increasingly typical case of state-led capitalism, which can help us understand the strengthening, yet polymorphic, involvement of the state in the global political economy.

This paper thus contributes to the ongoing discussion in IPE on the role of the state in the governance of the global economy. Through accounting for the seemingly contradictory developments observed in the French case, it offers a series of general and counter-intuitive explanations. For both banks’ and insurers’ regulated savings, we indeed show that the French state has been in the position to use private actors to fulfill some kind of public goals. For banking, and due to long-term institutionalized relations, state officials have dealt with compliant and reliable partners in the person of the French banking community. Although they are bank-managed, the state never had trouble imposing its own priorities regarding how and to what purpose regulated savings should be offered. Consequently, policymakers didn’t challenge this non-marketized effective way to govern through markets. The story differs for the insurance community—but the outcome is largely similar. State officials can’t govern regulated savings for state-defined priorities through insurance markets without encountering the opposition of the industry. As a result, they have purposely designed the conditions for greater marketization of regulated savings offered by insurers with the aim to stimulate capitalization and investment in large domestic firms. Here, it is a series of industrial policy objectives that the design of financial products has served.

Theoretically, we believe that there are lessons to draw from this overall process. By stressing the importance of endogenous institutional factors, our study undermines two familiar interpretations as to why active state involvement co-exists with marketization processes. The first argues that non-marketized domains are pockets of resistance, ‘relics’ of central planning (Bruton et al., Citation2015, p. 93). The comparison of two important subsectors of the financial industry in France shows that the dynamics at play are not primarily about fostering (or resisting) marketization—but that both are the result of pro-active state-led policy strategies. The second conventional explanation argues that neoliberal states largely act at the service of market interests (Grosman et al., Citation2016, p. 202). Although we show that they come with a cost for public actors, both marketization (or the absence of) can be understood through the lens of state priorities per se.

To arrive at these conclusions, we test in the following pages a range of explanations for what is further described as a process ‘dualization’ of regulated savings in France. Methodologically, we follow a qualitative, Bayesian process tracing approach in which we confront prior beliefs about the likelihood of several causal propositions to our data. We do so by combining different sources that include a rich analysis of documents and semi-structured interviews with policymakers and private actors.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In the subsequent section, we describe in greater length the dualization process that has occurred in the area of French regulated savings markets. Next, we evaluate the explanatory purchase of a series of likely explanations that account, at best, for a limited share of the observed variation. A third section then examines the involvement of state actors in both cases, followed by a concluding section that summarizes and discusses the implications of our findings.

Regulated savings in France: growing through partial marketization

Our goal in this paper is to explain the growing segmentation of regulated savings in France that have a longstanding high level of coverage and still account today for the vast majority of savings in the country. These products are diverse and might serve different policy objectives. Yet they all belong to the same broad category, as they have shared for decades some essential commonalities and have mostly consisted in risk-free, liquid and poorly remunerated products. In this context, the marketization of (even part of) regulated savings in France was very unlikely. That we observe the design and the growing share of more financialized products, however, constitutes only one aspect of the puzzle—as, far from being a unidirectional movement, marketization has been partial and largely segmented within the financial sector. These contrasted developments are further described below. Next, we introduce our analytical and methodological strategy to elucidate their underlying causes.

Banks’ regulated savings: status quo and non-marketization

In France, regulated savings offered by banks have a long history. The Livret A was established in 1818 by King Louis XVIII to pay back the debts incurred during the Napoleonic Wars (Constantin, Citation1999). In the aftermath of WWII, the French government actively promoted regulated savings products (épargne populaire réglementée), the funds of which were explicitly dedicated to funding public missions (until recently, mostly social housing). To this day, regulated savings products have remained very popular among the French. They represent 20% of the total financial wealth of the French (including real estate). 54.9 million have a Livret A, which represents a penetration rate of 81.5% in 2020.Footnote3

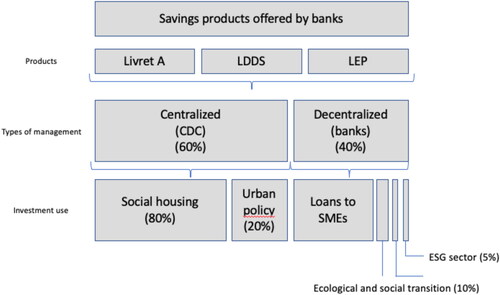

In the last few decades, there have been several reforms. Until the 1980s, the Livret A remained the only regulated savings product offered. Since then, more products have appeared, with the saving account for sustainable and solidarity development (Livret de Développement Durable et Solidaire (LDDSFootnote4)) and the people savings account (Livret d’épargne populaire (LEP) in 1982). Yet, the multiplication of regulated savings products didn’t aim to diversify the offer of products, but rather to increase the supply of regulated savings. All these products are indeed regulated similarly with respect to the interest rate of savers’ remuneration and with the allocation of credits based on those funds.

In the 2000s, several commissions were set up to propose reforms of the regulated savings.Footnote5 The main following reforms came from the ‘Law for the modernization of the Economy’ (Loi de modernisation de l’Économie) promoted by the then minister of finance Christine Lagarde (currently President of the European Central Bank) and implemented in 2009. The law introduced two main evolutions. First, the collection and distribution of savings products were changed. Until then, only one public bank (La Banque Postale) and two non-profit banks (Caisses d’Epargne and Crédit Mutuel) were allowed to distribute savings accounts. The law opened the distribution of regulated savings products to all banks, including commercial ones.Footnote6 The second most significant change introduced by the law concerned the management and the allocation of savings funds. Until then, 100% of the deposits were centralized by the Caisse des dépôts et consignations (CDC), a public financial institution created in 1816 which operates several missions of general interests on behalf of the state.Footnote7 The CDC then reinvested the totality of the savings funds in social housing. The law implemented a so-called decentralization of funds. Only 60% of the funds collected are now managed by the CDC. The so-called ‘non-centralized’ funds (roughly 40%) remained on banks’ balance sheets and are managed by them.

At the time, the reform provoked some critique mostly from left-wing observers. They feared that the reform would challenge the public missions that were traditionally attached to the use of savings funds. Some saw the reform as ‘a gift to the banks’.Footnote8

However, the reforms introduced by the 2009 law have not led to the marketization of regulated savings products. While the distribution of saving products was opened to commercial banks, this came with strict regulatory conditions for the collection, remuneration and uses of those funds—the same conditions applying across all banking networks and across all the territory. State’s regulatory intervention guarantees the safety, liquidity and remuneration of the savings. The funds are publicly guaranteed, and savers can use them at any time. Each citizen is allowed to own only one account of each kind, and there is a ceiling for funds placed in these products (22.950 euros per individual for a Livret A). The government fixes the remuneration of regulated savings twice a year (the Banque de France (BdF) may make a non-binding suggestion to change the rate of remuneration twice a year, too). Negative interest rates are not allowed. Finally, the interests earned on savings benefit from fiscal exoneration.

Although they have been decentralized, the allocation of these funds also remained very regulated, and completely escaped marketization logics. The so-called ‘centralized’ funds are required by law to be used by the CDC to finance social housing (80%) and urban policy (20%).Footnote9 The so-called ‘non-centralized’ funds (the roughly 40% left) are required by law to be used by banks to finance small and medium-sized enterprises at 80%, projects contributing to the energy transition and the reduction of the climate footprint at 10%, and the social and solidarity economy at 5%. The allocation of funds by banks totally escapes market mechanisms: The applicable rates of granted loans are required to be the same for all borrowers, regardless of their geographic situation or financial condition. summarizes the process of collection, management and allocative uses of regulated savings funds in France since 2009 as it was described in this section.

Hence, despite some evolutions, banking regulated savings has largely escaped the marketization logics that were extending to other areas of the French economy. Simultaneously, a completely different story was unfolding in the insurance sector.

The marketization of insurers’ regulated savings

Though rarely analyzed as such, there is in France a sizeable array of products mostly offered by insurance companies that share a number of similarities with those offered by banks. They mostly serve to finance government debt, provide extended social coverage to specific corners of the population, or direct private investments towards French companies. These insurance-based regulated savings essentially can be grouped into two sub-categories, namely pure life insurance schemes and private retirement accounts.

During much of the 19th and 20th centuries, life insurers (that developed after the end of the Napoleonic wars) have focused their activities ‘on life-cycle related products, for which they had a legal monopoly, rather than competing with other financial institutions on purely financial products’ (Hautcoeur, Citation2004). One crucial reason to this has been the persistence, until the end of the 1970s, of heavy state regulations of companies’ portfolios and state intervention on certain policy conditions, as well as on the rates of premium (Wrigley, Citation1975). Despite several waves of privatization that started during the second half the 1980s (and that have accompanied the significant internationalization of the sector), life insurance in France is still nowadays heavily dominated by euro funds that account for more than 80% of savings—a figure that is broadly similar across different categories of insurers, notably with respect to their size and degree of internationalization. Provided with a substantial amount of government bonds, the current situation of life insurance, though different in a number of respects with that of the end of the nineteenth century, thus also features a number of interesting similarities with a period where it de facto has grown as a funding vehicle of the French state.

Private retirement accounts constitute the second class of regulated savings that are mostly offered by insurance companies—and in this area, changes have been much more perceptible. As with other Western European countries, France has indeed witnessed during the recent decades a series of reforms that have reduced the share of pension spending covered through social insurance schemes (see Häusermann, Citation2010). In this context, a full range of products has been designed by successive French governments during much of the 1990s and 2000s to respond to the (perceived) demand for private retirement accounts, a segment once largely ‘crowded out’ by pay-as-you-go pension schemes (Naczyk & Palier, Citation2014). While mostly initiated by right-wing governments (to which employers that have historically backed these measures have been tied), the most recent (and decisive) developments in this area have benefited from the decisive inputs of left-wing and centrist-liberal governments—an apparent paradox that we explain in the next sections by the crucial investment of state actors in this domain.

While the possibility for firms to create occupational plans was already permitted by the General Tax Code (Code général des impôts, CGI), self-employed (1994) and farmers (1997) gradually gained access to voluntarily pension plans managed by private financial institutions (contrats Madelin). In 2003, François Fillon, the then right-wing Ministry of Social affairs, led an important reform of the French pension system that notably introduced three new devices—for individuals, private and public sector employees, respectively. Overall, the success of the above-mentioned products has however remained limited (Palier & Thelen, Citation2010), and it is only in the most recent years that the market really expanded as a result of explicit, ambitious policy decisions.

In 2019, the so-called Loi Pacte (the so-called ‘law for the growth and the transformation of enterprises’) was enacted under President’s Macron’s centrist-liberal government to unify (or simply to abolish) the myriad of existing products that were replaced by an integrated scheme, the Plan d’épargne retraite (‘retirement saving plan,’ PER). This flexible, unified device, can be used ‘both as an occupational and personal pension vehicle’ and can also be paid out ‘both in the form of an annuity and a lump sum.’ More fundamentally, ‘all assets accumulated in the plans are fully portable as they can be easily transferred from PER account to another one’—thus creating room for ‘greater competition’ between providers (Naczyk, Citation2021). While it was launched a few months before the Covid-19 pandemic, the product is already regarded in the sector as a ‘tremendous success’.Footnote10 For individual savings alone, the amount of deposits has grown by around 60% between 2019 and 2020—while it has remained stable before the five years preceding the reform.Footnote11 This trend was confirmed ever since with, according to the most recent available data, an increase of the amount of deposits by 125% between February 2020 and February 2021—and an increase by 51% of new PER underwritten. The rapid development of the PER is even perceptible at the aggregate level. In 2021, the share of deposits invested in stocks and bonds in life insurance has increased by €58.5 billion, an increase almost exclusively explained by PER deposits. Stock and bonds indeed represent between 75% and 80% of invested deposits within a PER.Footnote12 With 87% of PERs directly managed by insurance companies, the Loi Pacte has thus not only achieved the marketization of private retirement accounts that several governments have pursued for decades. It has also constituted an unprecedented success for the French insurance industry.

Accounting for the dualization of regulated savings

While it suggests contradictory developments, the growing segmentation of banks’ and insurers’ regulated savings in France is not necessarily discordant with some familiar interpretations of state-market relations in contemporary capitalism. The co-occurrence of deep or persisting forms of state intervention and marketization is indeed one of its well-established features (see van Apeldoorn et al., Citation2012). What is perhaps more puzzling in this case is that the pursuit of two seemingly contradictory agendas has happened within the same specific corner of the financial sector. There seems to be, however, more in this process than an additional illustration of the ‘directionless’ or incoherence of France’s political economy (Levy, Citation2013) or more broadly, of ambiguities inherent to state capitalism (Kurlantzick, Citation2016). Given that these policy choices resulted in the institutional decoupling between a protected (and still heavily regulated) tier and a more ‘marketized’ tier opened to greater liberalization and financialization, the trend described above is certainly more accurately described as a form of dualization (Palier & Thelen, Citation2010). While the term originates from the study of labor markets, industrial relations and social policy, the broad move that it captures has some resemblances with the trends observed in the French financial sector. Here also, the core characteristics of a coordinated or ‘state-led’ political economy (Schmidt, Citation2003) are maintained (and even reinforced) while marketization develops within the same area due to co-occurring policy decisions—or possibly, as a very consequence of such decisions.

Seen through this lens, the dualization process of regulated savings in France raises a series of important questions that point to different interpretations and explanations of this outcome. The divergence between banks’ and insurers’ regulated savings could be first a result of different degrees of mobilization of interest-groups, namely of the representatives of the banking and insurance industries. This would be the case if some divergent preferences between these two subsectors were initially observed, and if one would be successfully shaping some regulated savings for itself, thereby creating a rift with other regulated savings in terms of their broad features and orientation (see Naczyk & Seeleib-Kaiser, Citation2015). Secondly, dualization could involve a much broader coalitions of actors—in that case categories of savers, that could play a similar function as workers in the dualization literature. Given the quite distinct sociological profiles of the customers typically targeted by banks’ and insurers’ regulated savings (see below), dualization could thus be due to policymakers’ trying to advantage some of these groups at the expense of others, maybe as a consequence of some distinct (namely product-specific) feedback effects. Lastly, the same outcome could more simply reflect the pursuit by state actors of separate, seemingly contradictory but not necessarily antagonistic policy objectives. According to this view, different strategies would result in different developments of these products, thus revealing policymakers’ enduring capacities to treat regulated savings first and foremost as policy instruments in the service of some distinct public goals and ambitions.

These three competing interpretations, that are not necessarily mutually exclusive, are successively explored in the following pages. Methodologically and for that purpose, we implement a form of the Bayesian approach to process tracing. Bayesian process tracing evaluates the explanatory purchase of different causal mechanisms ‘through a combination of affirmative evidence […] and eliminative induction of other hypothesized explanations that fail to fit the evidence’ (Bennett, Citation2008, p. 708). This approach follows three generic steps. First, the researchers evaluate and disclose their initial priors (or degrees of beliefs) about the credibility of a range of hypotheses. Then, they collect and analyze pieces of evidence by estimating the likelihood that this specific piece of evidence would be found if a hypothesis (or an alternative) were true, through performing a series of process tracing tests. Finally, the initial priors are reevaluated in the light of evidence and the researchers’ posterior beliefs are estimated. On this basis, we evaluate in the next two sections the credibility of different causal propositions. The broader context in which these developments occurred (namely the low interest rates environment that significantly affected the financial industry and its strategies) is used as a test case for our inferences, most notably for the last proposition. For reasons of clarity, we discuss and describe each proposition in a narrative form in the following pages. The rationale behind choosing these hypotheses, as well as how we have implemented the different steps of Bayesian process tracing (including process tracing ‘tests’) is discussed in greater length in the Supplementary Material.

The alternative explanations: business actors’ preferences and the sociopolitical profile of savers

In this section, we test a series of familiar explanations to account for the dualization of regulated savings in France. We first describe the preferences of banks and insurers. Then, we map out the profile of savers that markedly differs from one class of products to the next. Both explanations provide, however, a quite limited account of the variation observed.

Banks, insurers and their preferences

The sectoral dimension of the (non) changes that have occurred in the area of regulated savings suggests that this outcome could be a result of banks’ and insurers’ preferences and their expression in the realm of policymaking. While seemingly consistent with the marketization of private retirement accounts, this interpretation is at first glance less evident with the status quo that prevailed for regulated savings offered by banks. We nonetheless know from a rich literature on business power that apparently surprising (non-)changes in capitalist political economies are due to the facts that businesses’ preferences (often conceived as homogeneous by the students of business power) actually vary. Consequently, reforms that could be at first sight interpreted as a defeat for powerful business actors are actually explained by the very preferences of these actors (Culpepper, Citation2011; Martin & Swank, Citation2012; Swenson, Citation2004). However, the polarization between bank and insurance regulated savings cannot be explained by differences in the preference of banking and insurance actors.

It is true that the marketization of private retirement accounts is an outcome that the insurance industry in France has long sought to achieve. From the 1980s onwards, its representatives have repeatedly mobilized to promote the development of long-term savings in the country and to foster both their diffusion and their profitability. It is in this context that what was initially perceived by insurers as a financial matter was gradually linked to broader social policy objectives—thus extending the potential scope and ambitions that the development of private pension accounts could achieve (see further). The recent development of the PER could thus appear as a victory of the interests of the insurance industry. However, a more careful examination of the design of the PER reveals a number of characteristics that seemingly goes against the industry’s objective or perceived interests. In effect, the law that created the PER also demanded insurance companies to segregate individual pension assets to insulate these funds. This created, as discussed further in the next section, a range of additional regulatory and financial issues that eventually affected firms’ management of their solvency ratios and put their profitability at risk—two consequences largely anticipated by insurance companies, and against which they have explicitly mobilized. This alone does not indicate that insurers did not play any role in the making of the PER, but the device, as it appears eventually at odds with business actors’ preferences, can thus hardly be considered as a result of a successful mobilization of the industry. A more careful examination of insurers and their strategies further challenges the idea that the marketization of private retirement accounts has been a priority in the sector in the most recent period. Indeed, the limited success of the numerous private retirement accounts that have existed in the country since the 1990s was not only induced by the limited interest they have generated from savers—they are also a consequence of the reluctance of the majority of the industry, heavily focused on less risky euro funds, to fully integrate private retirement accounts to their business model. The success of the PER thus appears, from that vantage point, as paradoxical—suggesting that other factors than the preferences of business actors might have been at play.

Banks were not happier with regulated savings products than insurers. Actually, they’ve been vocally complaining about them for decades. Banks deplore that they have limited decisional power on the allocation of credit based on savings funds, which from the point of view of market efficiency, lead to inefficient allocation captured savings. More importantly, the management of savings bring them low or even negative profitability. This situation has gotten worse with the recent context of rising inflation. Finally, banks are complaining that they bear the transformation and liquidity risks (which consists in taking very secured deposits and investing them in riskier assets) in a context of regulation that penalize risk-taking such as Basel 3. Banks have had multiple demands with regard to reforming regulated savings to their advantage: They suggest lowering ceilings for accounts, reducing fiscal advantages and deregulating interest rates to remunerate savers.Footnote13 Banks are supported by the BdF’s officials as well as by experts from the public and private sectors that can be described economically as liberals.Footnote14 The so called ‘Commission Attali’ in 2020, chaired by Bernard Attali, honorary senior advisor at the Cour des Comptes, and led by Patrick Artus, economic advisor at Natixis, illustrates this support through their demands to marketize regulated savings. However, despite the pressures from banks, successive governments have kept banks’ regulated savings largely out of the reach of market mechanisms.

Savers and their (political) sociology

Another factor that may account for the dualization of regulated savings in France relates to the pre-existing sociological differences between savers, that are usually closely correlated with each specific class of products. In France, regulated savings offered by banks have indeed usually concerned low- and middle-class people, whereas life-insurance products have been mostly acquired by upper classes. One expectation in this regard could be that state actors may be willing to protect mass public from processes of marketization while allowing more well-off individuals to take greater risk through marketized products. Alternatively, the status quo in banking and the marketization of private retirement accounts could also be an explicit arbitration of policy-makers between specific social groups. In both instances, the above discussion at least suggests that any attempt at (non) intervening on the pricing, return, liquidity and fiscal regime of a given product could be shaped by ‘prior policy-generated conditions’ both at the elite and mass politics levels (Campbell, Citation2012).

The ‘popular’ dimension of the regulated savings products offered by banks is indeed striking. 81.5% of the French had a Livret A in 2020.Footnote15 However, on average, banking savings accounts are preferred products of the low and the middle classes. The amounts held in those accounts are low. The Groupe BPCE–Audirep savings barometer distinguishes five categories of Livret A users: Only 22% belong to category ‘fully used reserve accounts’ of otherwise well-off households. A study from the BdF (2020) shows that the national average held in Livret A is 5,500 euros.

So, is the status quo in banking regulated savings motivated by public concerns for the savings of low- and middle-class French citizens? The general policies of the French governments in charge during the last few decades seem to suggest otherwise. There has been no protection of the low and middle classes from the process of marketization in other areas. As typified by the case of private health insurance, marketization (often in combination with public subsidies) has even been the privileged way through which successive French governments have tried to integrate low- and middle-class households to entire segments of the political economy (Benoît & Coron, Citation2019). However, we shouldn’t assume perfect rationality of policy-makers. Moreover, and even assuming some rationality in policy-makers, a certain category of the population may be disadvantaged by some reforms and protected (as a form of compensation) by other reforms.

However, the policies implemented by a government establish priors regarding the expectations in terms of their political priorities. There has been repeated evidence that the social or financial protection of the low and middle classes rank quite low in the political priority of the last French governments—in particular since the election of Emmanuel Macron in 2018. The ongoing retirement reform, which penalizes comparatively lower and middle classes as well as women with families, can attest of this trend.Footnote16 It is still possible that regulated savings would be an exception. However, the assessment of the evidence in our qualitative analysis shows very little to support this hypothesis—on which priors are already low to start with. Alternatively, we find much evidence for the other hypothesis of the state using regulated savings products strategically to direct investment towards state-defined priorities. The recent call of president Macron to channel regulated savings into investment in nuclear energy—a flagship of the French industrial policy, gives further confidence in this prior.Footnote17 In short, although empirical evidence doesn’t allow us to exclude completely that the protection of working-class savers may have mattered, it allows us to say with a high degree of confidence that this principle has not primarily defined the trajectory of regulated savings products in France.

The sociological differences are perceptible with life insurance, and even more so with private pension account earners. While representing 90% of the whole French population, what are defined by the industry as ‘standard households’ (i.e. households with a taxable income of 50,000 euros or lower) possessed only a 55% share of the total amount of life insurance savings. They are also overrepresented in euro-funds (as opposed to stock and bonds) investments. Crucially, this share has continuously declined over the recent years, and was only 48% in 2019. Between 2012 and 2019 (namely during the same period where a decline of the share of standard households in life insurance is observed), the share of both high and very high-net-worth individuals and their investments increased significantly.Footnote18

As already suggested in the previous section, this trend was substantially reinforced with the PER, a device that de facto targets the highest incomes. Interestingly, this is also reflected by (and thus, possibly a consequence of) the fiscal conditions that are offered by this specific product. Like other private retirement accounts of this kind, contributions to the PER are indeed subjected to tax deductions, thus counterbalancing the effect of the taxation of premiums. Such tax deductions are, however, less advantageous (if not virtually inexistent given their tax rates) for middle and low-income earners, meaning they will support a fiscal burden on premiums that will not be compensated. It is thus a specific profile of savers that has been advantaged (and possibly, targeted) by the marketization of the regulated savings offered by insurance companies.

There is, however, a lack of ‘smoking gun’ evidence to support the idea that favoring higher income earners at the expense of others was actually the intent of policymakers, insurers and their representatives. Making the PER more attractive for employees has recently topped the governmental agenda, and is still considered as an important issue to fix—as suggested by the recent debates held at the National Assembly and at the Senate in the context of the finance bill for 2022.Footnote19 Several labor unions also remained mobilized to obtain a ‘democratization’ of this device. Regarding the industry, it is true that recent years have seen a tendency from certain life insurance companies to try to more openly attract high and very high-net-worth individuals in the context of the declining performance of euro funds—thus individuals who are also more susceptible of investing a larger share of their portfolios in stocks and bonds. Some authors have even argued that this business strategy was increasingly reflected in insurers’ policy stances that would have gradually shifted from a demand to get access to the largest possible share of labor market insiders (Naczyk & Palier, Citation2014), to a more selective approach focused on co-designing products more appealing to executives and top managers (Palier, Citation2021). This strategy (both economically and politically) was, however, essentially pursued by some companies, while the majority of them (as well as the industry representatives) have tried to increase the number of savers without being particularly selective ex-ante with respect to their investment profile—and there is a wide consensus in the sector to consider that a mixture of both strategies is the most efficient option.Footnote20 In an overall context where lower-classes’ contribution to life insurance is anticipated to become more and more residual in the coming years, several sectoral actors have even warned about a situation that could be detrimental to the industry’s image and to its business model more broadly.Footnote21 In light of this evidence, it thus seems plausible to consider that if the PER is more appealing to higher income earners, it is more a way to maximize its impact on the short run than a clear and long-term arbitration in favor of this particular category of savers.

Agenda-setting and power relations in state-finance nexuses

So far, we have attributed a limited explanatory purchase to the two series of likely explanations for the dualization of regulated savings in France. We have seen that if the marketization of pension saving accounts was broadly consistent with insurers’ preferences, the typical profile of savers targeted by the reform cannot fully account for this outcome. This leaves us with the puzzling question of why insurers apparently succeeded. Our findings are ever more challenging for the case of the banking industry. Banks are vehemently denouncing the consequences regulated savings have on their activity, particularly in a context of low interest rates. And there seems to be no clear political agenda to protect regulated savings holders from a potential marketization of their savings. We are thus confronted here to the opposite question, namely why banks apparently lost.

A third series of explanations has, however, yet to be considered. Regulated savings are indeed hybrid products, that see private and public actors involved in a relationship to serve a delineated range of pre-determined objectives. In this broad context, such a configuration engenders a distinctive set of mutual dependencies between public and private actors. This is a well-known feature of what Busemeyer and Thelen (Citation2020) have called ‘institutional power,’ namely, a source of business power acquired by firms through the provision of public goods or services. In most instances, however, institutional power builds and develops on pre-existing relationships between public and private actors in a given area. In other words, institutional power is not exerted in the same way, nor have the same implications depending on which private actors are concerned, and how it traditionally coordinates with state actors.

In the next section, we build on this observation to analyze the situation of regulated savings in France—and find that both the policy patterns generated by public-private relations induced by regulated savings and the prior conditions on which they build account for a substantial share of their differentiated trajectories. Specifically, we show that the status quo for banks prevailed because of banks’ willingness to maintain their engagement in a relationship with state actors conceived as a mutually beneficial long-term exchange of favors. As such, that they continue to offer poorly lucrative public goods and services through regulated savings shall not be interpreted as a defeat vis-à-vis public actors, but as part of a larger gift economy with public actors that has to be sustained—and that crucially imposes relative costs to all participants in the relationship. Insurers effectively obtained, through the marketization of private retirement accounts, an outcome they have long sought to achieve. But this seeming victory has to be understood in a broader context where public actors are increasingly trying to ‘govern’ insurers’ own funds and to direct their investments to support the domestic economy. In this context, insurers are benefiting ex-post from policy decisions, rather instrumenting them ex-ante. As such, and instead of primarily participating in the provision of social coverage in an overall context of retrenchment, the main function of the marketization of pension savings accounts is part of a broader attempt of state actors to orientate private investment channels to achieve their own policy objectives. In both instances, state actors’ capacities to impose their objectives to private actors was key.

Banks, insurers, and the politics of institutional power

In this section, we discuss a third series of explanations informed by a more careful examination of state-bank and state-insurers’ relationships and their evolution—that eventually provides a better elucidation of the underlying causes behind our outcome of interest. The dualization of regulated savings in France, we here argue, are indeed best understood when they are jointly analyzed as serving some pre-determined policy agendas while simultaneously being embedded in broader (and institutionally differentiated) nexuses that are specific to each sector. After having established this proposition, we use some selected developments observed in the recent years as a test-case to further substantiate our arguments.

Regulated savings in the state-bank nexus: a gift economy

State-bank nexus in France is characterized by narrow intertwinement both from a structural and instrumental point of view. Structurally, state actors rely on banks. Indeed, banks still largely fund small and midsize enterprises (SMEs). However, recent scholarship has shown that the relationship didn’t limit itself to this traditional conception of structural power (Dafe et al., Citation2022). The relationship is not a one-way street. French banks also rely on state actors to defend their interests. Scholarship on banking regulation has shown that the French government has pursued an active agenda in support of its national banking champions, by opposing anti-’too-big-to-fail’ regulation and by promoting the universal model of the French banking groups both at the national and at the European levels (Gava et al., Citation2022; Massoc, Citation2020, Citation2022b; Macartney et al., Citation2020; Mitchell, Citation2022). Instrumentally, the connections between the Finance Treasury and bankers in France go beyond the revolving doors problem and have been depicted as forming one and the same community (Jabko & Massoc, Citation2012).

The state-bank nexus described above reinforces and perpetuates the relationships based on mutually benefiting gift-counter-gift between French bankers and state actors, over the long term. This relationship goes well beyond the notion of sheer capture of state actors by bankers. Building on mutual trust among a small number of socially homogeneous groups used to cooperating closely with each other, state officials can convince bankers to play along on terms that are relatively unfavorable for banks, because their demand comes as part of a long-term exchange of favors, and bankers expect to gain from this relationship in the future. Recent contributions have shown that French banks—more than their European counterparts—accepted to endure immediate financial costs at the demand of the state that they fulfill public missions in times of crisis, showing that bankers accepted costs to maintain the relationship (Massoc, Citation2022a). To this date, the French state-bank nexus status quo largely holds, despite Europeanization and marketization. Even more, these phenomena may have reinforced the French state-bank nexus to position French banks as European champions (Massoc, Citation2022b).

Regulated savings are at the core of the state-bank nexus. In a context where they have no longer direct control of credit allocation (Monnet, Citation2018; Zysman, Citation1983), state actors mobilize regulated savings to fulfill core functions of the of political economy—a large part of which consists in funding SMEs which cannot access credit through marketized channels. Banks have accepted the status quo, even though managing these products are not profitable and they do not have much say on their allocation. They have done so because it is part of the state-bank nexus described above, which they don’t want to jeopardize.

Regulated savings in the state-insurance nexus: building a (private) investment state?

Though less studied than the state-bank nexus, several contributions have documented the existence, in the French case, of a state-insurance nexus with similar properties. Ciccotelli (Citation2014) has notably explored the socio-political structures that have ensured its reproduction over time, based on similar social trajectories and curricula between its members (insurers and their representatives, senior civil servants, specialized politicians, cabinet members) as well as their constant circulations between the three poles of this nexus—at the intersection of the bureaucratic (that notably includes the Treasury and the Insurance sub-directorate within the Ministry of the Economy and Finances); the political (and, notably, some specialized committees at the National Assembly as well as the Ministry of the Economy and Finances itself) and the economic (and more specifically large insurance companies like Axa) spheres.

Though based on mutual dependencies between public and private actors, the relationships within this nexus are not symmetrical. Public actors, in particular, have gained crucial steering capacities over the years in the context of discrete, yet crucial, administrative reorganizing. Until the second half of the 1980s, the insurance sector was indeed a relatively autonomous ‘principality’ (Bezes et al., Citation2019) within the Ministry of the Economy and Finances. A powerful insurance directorate was charged, through eight bureaus, of all dimensions of insurers’ activities—as diverse as prudential control, international affairs, contract law and regulation, or fiscal matters. In the early 1990s, however, most of these competencies were transferred to the Treasury, and two sub-directorates were placed under its control (respectively in charge of life and non-life insurance activities). This reform was partly driven by the simultaneous adoption of EU ‘third generation’ Insurance directives and by the development of the EU Single Market more broadly.Footnote22 In this context, the Treasury explicitly acquired an important strategic prerogative. In a context where French firms and notably the national ‘champions’ were in the process of growing at the European level, the Treasury was charged to increase the overall amount of savings and to direct them to finance French companies. It is in this context that it has actively encouraged the development of a market for private retirement accounts in France, seen as a vehicle to promote this agenda (Ciccotelli, Citation2014).

Our documents and interview data suggest that this background is crucial for understanding the gradual marketization of regulated savings offered by insurance companies. The pursuit of this growingly important agenda by the Treasury has been ever more pronounced in the recent years, during which the Insurance sub-directorate has adopted a dual approach. At the European level, it has mobilized to correct the ‘short-term bias induced by the introduction of fair-value accounting’ in the new European prudential framework, namely Solvency II (see further). Domestically, the goal has been to ‘reposition insurers’ liability to dynamize their asset allocation’ through intervening on the regulated products they were already offering, mostly through ‘developing pension savings,’ in an overall context where the traditional business model of French life insurers was presented as ‘unsustainable’.Footnote23

Part of this agenda was clearly consistent with the preferences (and the demands) emanating from the insurance industry and its representatives.Footnote24 A deeper analysis of the motivation behind the Treasury’s initiatives suggests, however, that insurers were more so followers, rather than the leading proponents, of these reforms. Our data confirm that part of the reasons for demanding insurers to segregate their pension assets (as explicitly required by the PER) was driven by the Insurance sub-directorate’s objective to force insurers to have a large pool of longer-term investments insulated from their short-term assets—a possibility that was already granted to insurers several years ago, but that they were reluctant to implement given their focus in euro funds. Crucially, the Treasury (and the Ministry of Economy and Finances through the Minister himself) have also taken stances against the interest of the insurance industry in the pursuit of their agenda.Footnote25 While the overwhelming vast majority of PER are currently offered by insurance companies or banks’ autonomous insurance branches, the Insurance sub-directorate and then the Minister have indeed continuously pushed for more competition between insurers and bankers. This first manifested in the design of a ‘custody-account’ (and thus, not insurance-based) PER. But this was reaffirmed ever since by advice from BdF’s Financial Sector Advisory Committee recommending more transparency and competition between these sectors.Footnote26 More recently, Bruno Le Maire, current Minister of the Economy, Finance and Recovery of France, himself has denounced the high administrative charges imposed by insurance companies (as opposed to those charged by the very few banks that offer custody-account PER).Footnote27

As for banks, what happened within the state-insurance nexus thus provides a crucial explanation of the transformation of regulated savings offered by insurance companies. The relationship within this nexus, however, features different characteristics. Here, powerful public actors pursue a stable and explicit agenda and assume a leading role, contrasting with the gift economy observed for the banking sector. These differences of course interact with broader structural conditions, including banks’ and insurers’ respective positions in the economy, and relatedly, the distinctive opportunities and costs that come with trying to direct or exploit these private actors’ own funds. But the case of the insurance sector also reveals that the transformation of regulated savings is also a matter of political agency that appears, through the lens of the active role played by the Treasury in their marketization, as part of the broader arsenal found by the French state to conduct economic policy and to support its national champions through other means (see Thatcher, Citation2014).

Test case for the state-bank and state-insurance nexuses: regulated savings in a context of low interest rate and rising inflation

Given their institutional features, both bank-based and insurance-based regulated savings have been strongly affected by the broader economic context in which bankers and insurers have operated during the time period considered—a period that has been notably characterized by the pursuit of a negative interest rate policy by the European Central Bank (ECB), which has resulted in a gradual reduction of its deposit facility rate. Crucially, we show that it is through the institutional conditions described above that this important challenge for regulated savings was dealt with in the two sectors—thus further establishing the importance of these nexuses to account for regulated savings’ (non) transformations. After having described the condition of banks, we next turn to an examination of what happened in the insurance sector.

Banks’ costs and complaints

Bankers have complained about their obligation to remunerate regulated savings accounts in a context of low interest rates for more than a decade now. The recent rise in inflation that started in 2021 worsened costs for banks. Bankers were particularly upset when the government decided in December to raise the remuneration of savings account holders. Experts predicted that once raised to 1%, the cost on the banking sector would be close to one billion euros (920 million). ‘In concrete terms, this represents between 0.3% and 0.6% of their net banking income,’ calculates Rafael Quina, analyst in charge of French banks at Fitch.Footnote28 Banks have become more vocal in their complaints. Of course, from a more general perspective, banks have benefited from the increase of interest rates and recorded record profits since then. That being said, the increase of remuneration of regulated savings products has really had direct impact on margins. In total, in 2022, the impact of a Livret A at 2% and a LEP around 4.5% could cost banks more than 3.6 billion euros, or around 6% of income of the sector’s retail banking.Footnote29 As a matter of fact, French banks did not record any ‘super-profits’ in the third quarter. Unlike other European banks, whose results have been boosted by the recovery in net interest margins, it took time for them to benefit from the effects of the rise in interest rates due to the increase in the cost of their resources, due to the revaluation of the rate paid on regulated savings accounts. Added to this is the very slow pace at which retail banks are passing on the rise in rates. This can only be done at the rate of renewal of the stock of loans, since the French market is 90% based on fixed-rate products.Footnote30 French banks are largely compensated for these costs elsewhere (it is not the sense of the argument developed here to say that French banks are penalized; on the contrary, French banks are largely compensated for their participation to achieving state-defined priorities in the context of the gift-counter-gift relationship with the state). However, for the point under study, it remains noteworthy that French banks accept to manage products although they are detrimental to profit maximization—by contrast to banks in other European political economies (Massoc, Citation2021, Citation2022a). From a strictly commercial point of view, it is noteworthy to ask why ‘it is up to the banks to pay to encourage regulated savings among the population?’Footnote31

State actors hold on bankers’ strategy of non-confrontation

Confronted with bankers’ complaints, state actors held still despite this tense situation and the protestation of the banks. Specialists of the French economy explained state actors’ position towards regulate savings by the idea that ‘the Livret A is a product too emblematic to dare touch’ (Cyril Blesson, macroeconomist at Pair ConseilFootnote32). State actors themselves are straightforward that ‘Savings funds are a common good.’Footnote33 More particularly, within a context of persistent economic difficulties, state actors are determined to keep a grasp on the regulated savings in order to keep the economy afloat. Revealingly, they explicitly compare regulated savings with ‘grand emprunt’ or large loan, a term to describe the large-scale borrowing of the state mostly used in times of warfare: ‘The regulated savings and the savings fund of the CDC are comparable to a large loan on a permanent basis!’ Footnote34 Although their discontent was explicit, French bankers did not adopt a confrontational strategy when the government decided to increase interest rates on savers’ remuneration. When questioned by the press, they refused to comment.Footnote35 One of them knowingly declared that ‘We don’t do what we want with regulated savings.’Footnote36

Exchange of favors: change in tax base for French banks’ contribution to the European resolution fund

French banks complained about regulated savings, but they did not adopt a confrontational strategy with state actors. However, this observation must be understood in the broader context of a long-term mutually beneficial relationship between the state and banks in France. Revealingly, very quickly after the increase in interest rate, the French banks obtained from the Treasury the authorization to deduct the deposits held in regulated savings accounts when calculating their contribution to the single resolution fund (SRF), a European entity created after the financial crisis to avoid mobilizing public money in the event of a banking institution’s failure, and managed by the Single Resolution Board. The calculation defining the amount of the annual contributions to the SRF are based in particular on the size of the deposits guaranteed by the banks—the larger the deposits, the larger the contribution. The money deposited in regulated savings accounts, such as the Livret A, used to be included. Banks obtained the right to remove the portion centralized at the Caisse des Dépôts from the calculation base, thus limiting the final bill. As justified by the Ministry itself, ‘these adjustments are fully compliant with the EU framework, and ensure a more accurate calculation of French contributions to the European resolution scheme, avoiding any ‘over-transposition’ that would further penalize the French sector without reason.’Footnote37 The ECB didn’t oppose the French front. Indeed, it was defeated earlier on a similar issue regarding regulated savings. In July 2018, the EU court had overturned the ECB’s decision to exclude regulated savings (or 245 billion euros) from French banks’ leverage ratio.Footnote38

Insurers’ costs and complaints

The low interest rate environment has been precociously identified by insurers as an important challenge for their industry, both in industrial and regulatory terms. Economically, lower interest rates mean decreasing performance and returns for euro funds to which life insurers are heavily dependent. This situation was further amplified during the Covid-19 pandemic, where central bankers have promptly adopted quantitative easing measures maintaining interest rates at very low levels and thus endangered insurers’ asset-liability management.Footnote39 This situation should have, in principle at least, incentivized insurers to diversify their strategies, and possibly to favor longer term, possibly riskier investments. Yet such strategy was precluded due to the (EU) regulatory framework in which insurers operate, the so-called ‘Solvency II’ directive. Inspired by the architecture of Basel agreements in the banking sector, the goal of this text was to set in place ‘a principle-based approach to the prudential regulation of insurance companies’ (Quaglia, Citation2014, p. 433). Under this approach, riskier strategies become way more demanding in terms of capitals, limiting insurers’ capacity to compensate the decreasing profitability induced by a low interest rates environment via other classical instruments at their discretion.

State actors in support of the industry…

In this context, insurers and their representatives have constantly pressured the Ministry of the Economy and Finance’s Treasury to defend their views in Brussels, and more specifically the lightering of solvency ratios for long-term stocks and some real assets like infrastructure investments. Their demands have been successful—and since 2017 (when Bruno Le Maire became Emmanuel Macron’s Minister of the Economy and Finance), both the Treasury and the Minister himself have conducted prolonged negotiations with the European Commission about Solvency II.Footnote40 Public actors largely embraced insurers’ diagnosis according to which the directive was a major obstacle for insurers’ long-term investment capacities in the economy.Footnote41 Interestingly, one can note that the so-called Loi Pacte enacted in this context not only created a more marketized product with advantageous fiscal conditions through the PER. It also demanded that individual pension assets be ring-faced—while giving insurers the possibility to use a specific vehicle, the Fonds de retraite professionnelle supplémentaire (FRPS, ‘Supplementary Pension Schemes’) to host segregated funds. Created in 2016, FRPSs were until then largely disregarded by insurers—but since 2019, the main insurance companies in France have created, or initiated the creation of their own, FRPSs. Crucially, FRPSs are subjected to a regulatory framework similar to Solvency I, in other terms, substantially less demanding in terms of capital requirements, allowing insurers to engage in long-term and riskier investments. Thus, the marketization of insurers’ regulated savings could in fact possibly be an exit option from Solvency II offered by policymakers, given regulatory constraints faced by French insurers and the low interest rates environment.

… in the service of their own policy objectives

A more careful examination of the implications of the segregation of pension assets on insurers’ daily operations, however, indicates that it cannot be considered as the result of policymakers’ attempts at preserving some lucrative assets from a stringent prudential framework. Initially presented as a way to protect pension account holders, the creation of a specific fund through an FRPS to host pension assets—which has to be formally approved by the regulator—in effect dramatically decreases capital requirements for these assets. But at the same time, having all pension assets in the same place increases capital requirements, as this prevents insurers from mutualizing these long-term assets with the short-term assets that they possess otherwise—a common strategy that insurers have traditionally pursued to cope with Solvency II. The shift from a regulatory standard (Solvency II) to another, less demanding one (Solvency I) thus compensates the mechanical increases in capital requirements that comes with the segregation of pension assets. Overall, recent modellings even suggest that rather than being strictly compensated, such a segregation could even be detrimental to a firm’s profitability.Footnote42 Far from being a concession to insurers, the segregation of pension assets should be viewed as being first—and foremost—a vehicle used by policymakers to direct their investments.

Conclusion

One of the most crucial endeavours in political economy today is to explain the apparent tension between the renewed active role of the state on one side and the continued processes of marketization and financialization on the other, as well as the diversity of state capitalism across political, ideological and geographical contexts. This paper has contributed to this ongoing discussion by analyzing the partial marketization of regulated savings in France—namely financial products at the core of the intersection between private finance and the public sphere, and where private actors are in a position to service some crucial public goods.

More traditional theories in comparative and international political economy have had trouble explaining differentiated processes of marketization within political economies. Regulated savings should have been wiped out by the marketization of the French economy. Or, they should have resisted the trend given the French tradition of state-led capitalism. But this paper has shown that the evolution of regulated savings has been one of increased internal hybridization. On one side, regulated savings offered by banks have remained non-marketized, while regulated savings offered by insurers have become increasingly marketized. Yet the causes of these evolutions are not to be found in factors affecting the whole French political economy indiscriminately. We have rather pointed to (differential and specific) institutional dependencies between the state and the banking and insurance sectors.

Building on a Bayesian process tracing approach informed by analysis of documents and interviews with policymakers and private actors, we have shown that the status quo in banking prevailed due to banks’ willingness to maintain their engagement in a relationship with state actors conceived as a mutually beneficial long-term exchange of favors. In the trade-off they faced between offering poorly lucrative products and taking the risk of endangering such relationship, banks opted for the former. By contrast, the paper has shown that the increased marketization of the regulated savings offered by the insurance sector should not be interpreted as a sheer retrenchment of the state’s involvement in the savings products offered by insurers. The state-insurance nexus being looser that the state-bank one, the processes that led to the evolutions of saving products’ operation has been more openly confrontational. However, processes of marketization in the insurance sector have largely followed the impulse of state actors themselves to promote targeted investments through the domestic private sector. The modalities of regulated savings’ marketization corresponding to the state’s priorities have been implemented, even in cases where insurers opposed them.

Overall, the situation of regulated savings in France doesn’t tell the story of the persistence of the powerful state, nor does it tell the story of the loss of such state power. Rather, this research contributes to the renewed question of the persistent, although multi-faceted and ambiguous role and involvement of the state in market economies. As such, its findings provide an additional illustration of the general hybrid trend characteristic of state capitalism beyond France. But at the same time, some of the lessons to draw from the case of regulated savings challenge some widely held views in the literature. First, we have shown that longstanding forms of state interventions are not necessarily relics from the past (Bruton et al., Citation2015, p. 93), but can serve dynamic and adaptive policy strategies. Second and more fundamentally, the active pursuit of such strategies is not necessarily at the service of private interests—even when such interests are both powerful, unified and well-organized. Rather, contemporary state capitalism is better characterized by state governing through private sectors with tools at their disposal. Crucially, the use of such tools as well as their effectiveness rest on institutional logics highly conserved in policy sectors where the state depends on private actors, without being necessarily subjected to them. As revealed by an enlarged corpus in IPE scholarship, states have been seeking to govern through markets more widely, in a context of rising geopolitical tensions and attempts to implement (green) industrial policies. A deeper—although polymeric—involvement of the state in the allocation of capital, has become a general characteristic of governance of the global economy. In that respect, we do not believe that the French case should be regarded as an outlier but rather as a case that can be increasingly considered as a typical case in the constellation of political economies undertaking some sort of state capitalism.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (346.4 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Elsa Clara Massoc

Elsa Clara Massoc is an assistant professor in International Political Economy at the School of Economics and Political Science of the University of St Gallen. Her research focuses on business-government relations, banking regulation, state-led credit allocation, the geo-economics of finance and (green) industrial policies.

Cyril Benoit

Cyril Benoît is a CNRS researcher at the Centre for European Studies and Comparative Politics, Sciences Po. His current research projects deal with the welfare-finance nexus in Continental European Welfare state, the political control of regulatory agencies and the political economy of legislative favoritism.

Notes

1 As this suggests, our classification of what constitutes regulated savings is more extensive than the traditional understanding of the term. Public and private actors alike usually define them as savings accounts that benefit from tax exemptions, guaranteed by the state and remunerated at a rate set by a pre-established formula. To qualify as a regulated saving, however, we consider as more heuristic to include the full range of products with a relatively substantial share of their functions and properties serving by design explicit policy purposes, and on which the state maintains lengthy regulations and oversight activities to guarantee that these objectives are actually pursued. Such a broader conception thus encompasses all types of regulated savings according to the traditional definition, but also and crucially, life insurance-like schemes when they touch upon social policy matters.

2 Interview with official at the Caisse des Dépôts et de Consignation, Author, 2022.

3 Observatoire de l’épargne réglementée de la Banque de France 2022.

4 Formerly known as Compte pour le développement industriel created in 1983, renamed LDDS in 2016.

5 Among others the report Noyer and Nasse (Citation2003), Camdessus (Citation2007).

6 Banque Postale continues to play a special role in terms of banking accessibility: The mission entrusted to it requires it to open a Livret A account for any person who requests it, starting with an initial deposit of 1.50 euros. Banks receive regulated remuneration in return for centralizing part of the deposits collected in the savings fund. Since 2016, the remuneration of the Livret A and LDDS collection networks has been 0.3% of the centralized deposits 2 and 0.4% for the LEP.

7 The CDC’s public missions are multiple and are described in the Code monétaire et financier (https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/codes/id/LEGISCTA000006170635/). They include, among others, the management of regulated savings, management of pension funds, management of public mandates (such as European funds). It is one of the main long-term institutional investors in France, with a mission that it accomplishes in partnership with Bpifrance (the French public bank) and the Banque Postale. It is accountable to the Parliament, although it is known to have more direct and narrow interactions with the Ministry of Finance (REF).

8 Laurent Mauduit and Martine Orange, “des réformes passent en douce á l’Assemblée,’ Médiapart, 12 June 2008 ; Martine Orange, ‘Le gouvernement lorgne sur le livret A,’ Médiapart, 1 October 2008; Laurent Mauduit, ‘Livret A: le décret scélérat de Christine Lagarde,’ Médiapart, 5 December 2010.

9 Banks are required to centralize approximately 60% of the Livret A and LDD, and 50% of LEP deposits with CDC. However, this rate is subject to a legislative floor, which stipulates that the centralization of funds must be at least equal to 1.25 times the amount of loans granted by CDC for social housing and urban policy.

10 Gatignol, J. (2021). Le PER s’affirme, L’Agefi Actifs, April-May, 20-25.

11 DREES. (2022). Les retraités et les retraites, édition 2022. Ministère des Solidarités et de la Santé.

12 France assureurs, une année record pour l’assurance vie. Available at: https://www.franceassureurs.fr/espace-presse/communiques-de-presse/2021-annee-record-assurance-vie/. Accessed June 24, 2022.

13 See, for example, articles by Jonathan Blondelet, Des pistes pour l’utilisation de la surépargne, Les Echos, 11 June 2021; Patrick Artus, ‘Cette epargne qui ne rend pas service à l’économie,’ 21 August 2021, Les Echos.

14 For example, a BdF official anonymously deplores that ‘This burden [regulated savings products], for the banks, comes to burden the possibility of financing the French economy,’ quoted in Emmanuelle Réju , Les anciens PEL dans le viseur de la Banque de France, 8 September 2021, La Croix.

15 Observatoire de l’épargne réglementée de la Banque de France 2022.

16 See for example, Observatoires des Inégalités, ‘Retraites: Le projet de réforme est-il injuste,’ 26 January 2023. Available at: https://www.inegalites.fr/Retraites-le-projet-de-reforme-est-il-injuste

17 See for example, Les Echos, ‘Le Livret A en lice pour financer les nouveaux réacteurs nucléaires en France,’ 9 February 2023.

18 See Facts & Figures in Baromètre 2021 de l’Epargne Vie, 12th edition. Available at: http://www.factsfigures.eu/categories.php?categorie=41&fichier=f1507&an=2021&an=2018&an=2012&an=2021&an=2012. Accessed June 24, 2022.

19 The full transcript of these debates is available at Legifrance. LOI n° 2021-1900 du 30 décembre 2021 de finances pour 2022. Available at: https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/dossierlegislatif/JORFDOLE000044087520/. Accessed June 24, 2022.

20 Interview, Head of Pension and Technical Products, Insurance company, June 2022.

21 Torres, E., & Ben Gharbia, N. (2020). Virage serré pour l’assurance vie. La Tribune de l’Assurance, n°260, 12-13. See also Rojas, D. (2019). L’assurance vie se concentre sur la clientele privée et patrimoniale, L’AGEFI Quotidien. Available at: https://www.agefi.fr/banque-assurance/actualites/quotidien/20190722/l-assurance-vie-se-concentre-clientele-privee-279690. Accessed June 24, 2022.

22 Interview, Former Head of Unit (Chef de Bureau), Treasury, March 2018.

23 Interview, Lionel Corre, Former Head of the Insurance Sub-directorate (Sous-directeur) at the Treasury (2018-2022), quoted in Schaffroth, E. (2020) Diversifier la poche obligataire en dehors de la zone euro: Une nécessité pour les assureurs, La Tribune de l’Assurance, n°253, 46-49.

24 France Assureurs, Révision de Solvabilité II 2021: Pour une économie européenne durable et compétitive. Available at: https://www.franceassureurs.fr/wp-content/uploads/VF_Revision-Solvabilite-II.pdf, Accessed June 24, 2022. See also Commission des finances, de l’économie générale et du contrôle budgétaire Compte-rendu 2021 de l’audition Mme Florence Lustman, présidente de la FFA. Available at: https://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/dyn/15/comptes-rendus/cion_fin/l15cion_fin2021033_compte-rendu. Accessed June 24, 2022.