Abstract

The concept of international regime complexity offers a useful lens for examining the increasing density of international institutions in global governance. A growing literature in International Political Economy (IPE) identifies clusters of overlapping institutions in many important policy areas, yet some scholars argue that complexity undermines governance effectiveness, while others perceive distinct advantages over unified institutions. To bring coherence to these findings, we present a general theoretical framework that characterizes regime complexes based on two structural features: Authority relations and institutional differentiation. These dimensions jointly determine the opportunities and constraints that states and other actors confront as they navigate institutional rules. As a result, they shape important outcomes, such as policy adjustment, regime shifting and competitive regime creation. The article proposes testable hypotheses regarding the effects of authority and differentiation, and we assess their correspondence with the eight regime complexes examined by the five companion articles in this special issue. We further identify a set of dynamic processes that shape the evolution of regime complexes over time. Our framework strengthens the foundation for comparative analysis of regime complexes and charts a new agenda for the research program.

Introduction

The landscape of global governance is increasingly crowded. In nearly every major policy domain, multilateral cooperation occurs within clusters of nested and overlapping international institutions. A growing body of research examines these ‘international regime complexes,’ establishing institutional density as a defining feature of contemporary global governance. Issue areas as diverse as trade, climate change, education and crisis finance have experienced a crowding of governance institutions over time. This increasing institutional density changes the strategic environment in which state, substate and nonstate actors interact, creating both challenges and opportunities for cooperation.

Scholars in this research program examine whether regime complexes improve or degrade substantive outcomes compared to a single multilateral institution. Some argue that the fragmentation of governance across multiple institutions threatens the effectiveness of international cooperation. These analysts fear that ambiguity over international standards, inconsistency of rules and obligations, and opportunities for forum shopping weaken the discipline of global governance on member states.Footnote1 Other scholars contend that regime complexes facilitate more effective cooperation: They increase flexibility, boost legitimacy, and engender greater expertise compared to unified regimes.Footnote2 Despite this rich variation in regime-complex performance, few studies have explicitly questioned why some regime complexes produce more favorable outcomes than others.Footnote3

The question of how overlapping institutions shape cooperation carries extremely high stakes. Regime complexes are both attempts to resolve shared problems and arenas for distributive conflict. They affect the configuration of international agreements, norms and rules; institutions’ ability to enforce compliance; the possibilities for effective dispute adjudication; and the legitimacy (or lack thereof) of global governance arrangements. They are an increasingly central battleground for political actors – including great powers, developing countries, civil society organizations and private corporations – who advance their goals by capturing or sponsoring international institutions. These dynamics are particularly important for research in International Political Economy (IPE), which seeks among other things to understand the consequences of institutional density in global economic governance. Institutional proliferation in core policy domains, such as trade, development aid and crisis finance, has transformed the architecture of governance, creating new and varied challenges for international cooperation.

This article proposes a general theoretical framework for explaining variation in outcomes across regime complexes. To do so, we focus on the patterns of interaction that emerge among constituent institutions. While all regime complexes feature institutions with mandates that overlap to some degree, they exhibit striking differences in the structure of inter-institutional relations. We highlight two features, relations of authority and institutional differentiation that vary considerably across regime complexes and shape patterns of cooperation within them. These two dimensions establish the set of opportunities and constraints for actors in the regime complex – determining, for example, whether states can exploit conflicting rules or opportunistically substitute one institutional forum for another.

Patterns of institutional authority and differentiation provide the basic ‘architecture’ of a regime complex. Our framework and the articles in this issue unpack the origins of this architecture, highlighting the role of state preferences, the structure of strategic interaction in an issue area, and competing attempts to frame governance of emerging issues. Crucially, we also specify testable hypotheses regarding the effect of authority relations and differentiation on substantive and institutional outcomes. We focus on two outcomes central to the literature on overlapping institutions: Behavioral adjustment on the part of states and other actors, and their strategic responses to sustained dissatisfaction with the regime. Finally, we identify a set of feedback processes that drive further evolution of the regime complex.

To test the framework, a team of scholars examines authority relations and differentiation in several empirical regime complexes. Contributors to this special issue investigate a wide range of policy domains – including education (Kijima & Lipscy, Citation2023), nuclear arms control (Eilstrup-Sangiovanni, Citation2023), cyberspace (Hofmann & Pawlak, Citation2023), crisis finance (Henning, Citation2023), election monitoring and environmental protection (Pratt, Citation2023). Some of these issue areas are common terrain for IPE scholarship; others investigate emerging issues or topics with important economic spillovers. The findings in these articles are largely consistent with our expectations, providing evidence of the generalizability of the framework. Each article also elaborates and extends the framework in productive ways, contributing new conceptual, theoretical and methodological tools for scholars of international cooperation.

Our goal in providing this framework is to better explain the rich diversity in regime complex performance and thereby improve our understanding of how regime complexes shape international politics and political economy. Previous studies have laid a foundation from which the research program on complexity may now proceed to specification and testing theoretical expectations. We believe that these goals are best served by integrating concepts in the extant literature to build well-specified, conditional theories of cooperation in dense institutional environments.

Our project advances debates in IPE in at least three ways. First, from its inception to the present, IPE has been closely entwined with the institutionalist research agenda in International Relations (IR). By improving our understanding of the role of institutions generally, the framework illuminates the origins of cooperation and its absence in global economic governance. Second, notwithstanding the substantial overlap in the institutionalist and IPE agendas, institutionalists have sometimes shied away from claims about economic and social outcomes that interest IPE scholars. This framework explicitly theorizes the effects of relations among institutions on policy adjustment and substantive outcomes, helping to bridge that difference. Third, this special issue contributes to further understanding of the evolution of governing arrangements that remain at the heart of IPE analysis – principally those for international trade, money, finance and developmentFootnote4 – as well as those on the frontier, such as decarbonization, flows of digital information, and global pandemic response.

The next section formally defines a ‘regime complex’ and situates our argument within existing scholarship in IPE and IR. Section 3 introduces the framework emphasizing the dimensions of authority relations and differentiation. Section 4 presents theoretical expectations and summarizes the findings of the other articles in this special issue. Section 5 describes the feedback mechanisms that drive evolution of regime complexes, while Section 6 concludes.

Regime complexity: concepts and approach

The study of international regime complexity has emerged as a discrete subfield within the International Organization and IPE research programs. While early scholarship on international regimes addressed the origins and development of international institutions, their relationship to states and other actors within the system, and their contribution to international cooperation, the subfield of regime complexity is distinctive in its focus on the proliferation and interaction of multiple institutions in the same issue area.Footnote5

We follow Henning (Citation2017) in defining a regime complex as a set of international institutions that operate in a common issue area and the (formal and informal) mechanisms that coordinate them. The institutions can be legally constituted organizations at the bilateral, plurilateral, regional, or global levels, as well as less formal arrangements. Mechanisms of coordination include both deliberate inter-institutional collaboration and recurring patterns of behavior that emerge from repeated interaction in a dense institutional environment.

This definition is broader than some other formulations in the field. Notably, we do not exclude hierarchical regime complexes by definition.Footnote6 By accommodating both hierarchical and egalitarian authority relations among institutions, we can better compare complexes and their ability to generate substantive cooperation. We adopt a broad concept of what constitutes an international institution, including formal intergovernmental organizations, informal fora such as the Group of Twenty, transgovernmental regulatory networks and nongovernmental bodies. A regime complex can therefore be populated by a diverse set of institutions, as long as they perform a governance function in the issue area concerned.Footnote7 In addition to these institutions, our definition draws attention to the mechanisms that coordinate them. These include formal and informal agreements, club groups and regularized processes.Footnote8

Like others, we identify the boundaries of a regime complex by the scope of the issue area to which it is addressed. Issue areas reflect a distinct policy problem that states seek to address via institutionalized cooperation, such as nuclear arms control, carbon emissions or balance of payments crises. The boundaries are not always fixed, as issue areas may shift due to exogenous events or strategic reframing. In this conception, global governance is cleaved into a series of regime complexes focused on particular cooperation problems. This does not preclude spillovers between issue areas: The institutions of balance-of-payments finance and development finance inhabit different complexes, for example, notwithstanding the substantial spillovers between the work of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The theory that we present below is situated firmly within the institutionalist approach to IPE and IR generally. But, in contrast to regime theory of the 1980s and institutionalism of the 1990s and 2000s,Footnote9 regime-complexity theory takes the interaction among institutions more seriously. Institutionalist scholars of earlier decades understood that the number of institutions was growing in most issue areas. But the research program implicitly embraced the notion that institutions could be safely studied in isolation, and the findings of separate studies simply aggregated, to explain cooperation in areas governed by more than one institution – an approach that we call ‘singular institutionalism.’ Regime complexity research, by contrast, explicitly departed from that approach by positing that interactions among institutions are consequential.

Our approach therefore shares some core assumptions of institutionalist scholarship: Transnational, multi-stakeholder and non-state actors vie for influence, but states tend to be the most important actors; these actors are rational, but boundedly and increasingly so as the time horizon lengthens; and institutions can constrain the behavior of these actors in the short run, but can be reshaped by changes in relative power and preferences among them over the long run. Like other proponents of regime complexity, however, we argue the institutionalist approach is incomplete without consideration of relationships and interaction among institutions.

The relevance of inter-institutional relations has become clear as research on regime complexity has evolved. Early scholarship emphasized the lack of coherent order among institutions in a regime complex. In this view, institutions are linked due to overlap in their jurisdictions, but otherwise operate independently with few mechanisms for coordination. In their original elaboration of the concept of regime complexity, for example, Raustiala and Victor (Citation2004) stress both the disaggregated decision making of institutions and the lack of a formal hierarchy to resolve conflicts among them. Alter and Meunier (Citation2009) describe the ‘cross-institutional strategies,’ such as forum-shopping and strategic inconsistency, that states can exploit in an environment of independent institutions. The literature’s early emphasis on the lack of coordination in regime complexes helped theoretically distinguish them from singular institutions.

In subsequent work, scholars challenged the view that inter-institutional relations in regime complexes are most commonly characterized by disorder. Overlapping institutions have developed a wide range of ties to coordinate rules, from simple communication to joint decision-making.Footnote10 Studies of ‘inter-organizational networking,’ ‘institutional deference’ and ‘orchestration’ document these ties in several regime complexes.Footnote11 In addition to formal coordinating mechanisms, the mere presence of a prominent, central institution may allow rules to cohere in advantageous ways.Footnote12 In some cases, a sophisticated division of labor can emerge among governing bodies, reducing inconsistency and opportunities to forum shop.Footnote13 As in other complex adaptive systems, overlapping institutions may develop a degree of order without any centralized means of coordination.Footnote14

Our framework builds on these recent studies examining patterns of interaction among institutions in a regime complex. We argue that the initial characterization of fragmentated regime complexes, featuring decentralized decision making, lack of hierarchy and policy inconsistency, is only one of several ways in which a regime complex might be organized. We instead dissect the concept along two dimensions – relations of authority and institutional differentiation – along which sets of overlapping institutions vary. A fragmented regime complex is an ideal type that sits at one end of both dimensions, where institutions are non-hierarchically arranged and undifferentiated. An integrated complex sits at the other end of the spectrum, where governance processes are hierarchical and differentiated. Empirically, regime complexes will take intermediate values on one or both dimensions.

Treating authority relations and differentiation as dimensions that vary and do so continuously enables us to push beyond the first wave of regime complexity theory.Footnote15 The framework we describe in the next section has three primary goals. First, we provide a general classification scheme to describe the underlying architecture of different regime complexes. Second, we develop testable hypotheses about the consequences of this architecture, helping to explain outcomes of interest to IPE scholars. Third, the framework offers a useful tool for analyzing dynamic change in regime complexes. The variables we highlight provide a two-dimensional ‘map’ for understanding regime complex evolution.

Classifying regime complex architecture

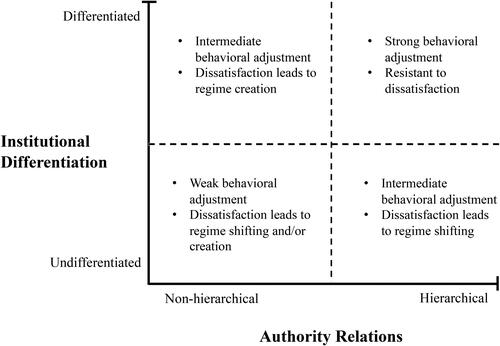

Our framework is centered on two architectural features of regime complexes: The extent to which institutions are arranged in hierarchical patterns of authority, and whether they are differentiated in scope or governance function.Footnote16 These two dimensions condition the effect of institutional density on substantive and institutional outcomes. In the short term, they serve as relatively fixed constraints on actors’ behavior. A government weighing a change in trade policy, for example, must maneuver within a trade regime that is hierarchically oriented around the World Trade Organization (WTO). In the long term, patterns of authority and differentiation are more malleable. They are shaped by the historical process of regime evolution and the strategic behavior of states, among other factors. summarizes these causal relationships.

The first arrow in describes the emergence of hierarchy and differentiation in regime complexes. We highlight two key processes that determine regime complex architecture. Since international institutions are created and controlled by principals – often national governments, though not exclusively – their preferences and capabilities fundamentally shape the degree of hierarchy and differentiation in a regime complex. States attempt to craft an architecture that serves their interests, though they are often constrained by other actors’ competing institution-building efforts and the inability to fully anticipate the effects of complex institutional clusters. Innate characteristics of the issue area, such as functional spillovers and barriers to entry, may also influence the regime complex architecture that emerges.

The second arrow in depicts the effects of the two dimensions. We propose a novel set of ‘stage-two’ hypotheses that link hierarchy and differentiation to two primary outcomes of interest: Behavioral adjustment on the part of states and other actors and their strategic responses to sustained dissatisfaction with the regime. In Section 4, we specify expected outcomes for each combination of the two dimensions. Policy adjustment tends to increase as regime complexes become more hierarchical and differentiated, while the strategies of dissatisfied actors vary in ways that affect the resilience of the complex.

Finally, these outcomes create feedback processes that drive further evolution of the regime complex. These are depicted by the dashed lines in . When dissatisfied actors engage in competitive regime creation, for example, patterns of authority become less hierarchical. Institutional rules and demands for policy adjustment can also shape the preferences of member states as they navigate and construct institutions. We elaborate on these dynamic processes in Section 5.

As the figure makes clear, regime complexes are embedded in a complicated set of causal relationships that require careful attention in empirical tests. However, our model posits that the effects of hierarchy and differentiation are not completely endogenous to state preferences.Footnote17 While strategic actors will try to anticipate ultimate outcomes as they construct and arrange institutions, the two stages can be separated by long periods of time, undermining principals’ ability to predict consequences in the face of changing circumstances. Even over relatively short periods, principals often confront countervailing coalitions with competing preferences over the architecture of the regime complex. Similarly, institutional secretariats can exercise a degree of agency, and agency slack can rise with the intensity and duration of interaction. When states can directly shape the regime complex architecture, they may choose arrangements that bind their future behavior, thus guarding against a change in domestic government and securing corresponding commitments from other states. For these reasons, the architecture at any point in time reflects an equilibrium of multiple pressures rather than simply mirroring the preferences of one or more principals.

Our framework thus preserves ample space for regime complex architecture – that is, the authority relationships and differentiation among institutions – to independently affect substantive and institutional outcomes. The articles in this issue employ a range of empirical methods, from process tracing to leveraging exogenous shocks, to isolate these effects. We now discuss each of the architectural dimensions in greater detail before explaining their sources and effects.

Relations of authority

The authority dimension reflects the extent to which institutions implicitly or explicitly recognize the right of other institutions to craft definitive rules, organize common projects or otherwise set the terms of interinstitutional cooperation. Authority of one institution over others can take the form of formal hard law, informal soft law, norms, secretariat deference and third-party recognition.Footnote18 But in all aspects, as Lake (Citation2009) emphasizes, there should be evidence of the subordinate institutions’ acknowledgement of the ‘rightful rule’ of the more authoritative.Footnote19

Relations of authority range along a continuum from a complete lack of hierarchy, where each institution claims an equal right to rule-making, to a formal hierarchy where some institutions are bound by the superior authority of others. Between these poles lies a diverse set of arrangements in which institutions distribute authority by delegating, orchestrating and deferring to each other. Inter-institutional patterns of authority have important implications for the degree of rule conflict and opportunities for forum shopping in a regime complex (elaborated below).

Hierarchical authority relations may be embedded in institutions at their creation. More often, authority relations emerge dynamically in the absence of ex ante legal hierarchy as institutions interact on specific issues. Green (Citation2013) distinguishes between delegated and entrepreneurial authority, which arises when one actor creates rules and then persuades others to defer to them. Pratt (Citation2018) highlights several cases in which international institutions defer authority to each other, including the UN Security Council’s acceptance of counterterrorism rules set by the Financial Action Task Force. Through orchestration, institutions may also establish softer patterns of authority in a regime complex.Footnote20

Patterns of authority are important for resolving conflicts among institutions. Hierarchy establishes deference to the peak institution in decisions about which institution should prevail in such conflicts. Among non-hierarchical institutions, there is no presumption as to which would prevail. Ex ante conflict resolution is an essential feature of hierarchy; it establishes the pecking order in the presence of inter-institutional disputes.

Importantly, the degree of hierarchy in a regime complex reflects the relative authority among international institutions. The variable is conceptually distinct from the amount of authority delegated by member states to a specific international organization. It is also distinct from asymmetrical influence or power among member states. States’ power relations often shape the governance structure of individual institutions and the architecture of the complex as a whole. Thus, the power asymmetries that matter are captured in patterns of authority among the institutions.

Institutional differentiation

Differentiation describes the extent to which institutions in a regime complex vary in the functions they perform. Like relations of authority, differentiation can be placed on a continuum. Sets of identical institutions that operate as like units are positioned at one end; these homogeneous institutions perform the same functions and are viewed as substitutes by states. At the other end are sets of institutions that are fully differentiated in the tasks they perform and the rules they adopt.

Regime complexes can be differentiated functionally and geographically. A functional division of labor, characterized by separation in substantive mandates and activities, is common among institutions. Gehring and Faude (Citation2014), for example, identify a division of governance tasks among the WTO, Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) and World Health Organization (WHO) with respect to governing trade in agricultural genetically-modified organisms. Green and Auld (Citation2017) describe a division of labor among environmental institutions, with non-governmental institutions (NGOs) serving as ‘idea incubators’ for intergovernmental bodies.

Geographic differentiation of institutions can be established by membership, scope of activity or expertise. The development finance regime complex, for example, features an array of regional institutions that specialize geographically in the provision of loans and grants. Geographic differentiation may be distinct from membership patterns. The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) includes member states from Europe, Latin America and Africa, for example, and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) monitors elections in Africa. Differentiation must thus be mapped with some care, but nonetheless affects the strategic environment in which states and other actors select policy.

Among other things, differentiation determines the freedom of choice actors have as they navigate a regime complex.Footnote21 Scholarship that emphasizes forum shopping in regime complexes typically assumes low levels of institutional differentiation.Footnote22 When differentiation is low, states can opportunistically select among institutions that may have different standards but are substitutable on other dimensions. In contrast, states have less freedom to forum shop if institutions are highly differentiated.

Discussion

Assessing regime complexes along these lines provides a more nuanced picture of the strategic environment created by institutional overlap. Importantly, the values taken by regime complexes on the two dimensions do not move in lock step with one another. For example, the institutions of a complex can be non-hierarchical and differentiated. This would occur if institutions with similar levels of authority strategically adapt to find specific governance niches. Similarly, hierarchical complexes could contain undifferentiated institutions. This observation contravenes the concept of hierarchy among states advanced by Waltz (Citation1979), who argued that hierarchy is necessary for differentiation in security relations among states.Footnote23 But this logic does not apply with similar force to positive-sum relations in the economic and social sphere. We maintain that the two dimensions exhibit variegated scores because hierarchy and differentiation may arise from different sources, as discussed in the next section.

When applied at the level of the regime complex, these dimensions describe the terrain of global governance in the relevant issue area: Whether a collection of institutions, as a whole, possesses a high degree of differentiation or hierarchy. However, the framework can also be used to analyze variation in institutional relationships at other levels of analysis. For example, scholars often examine overlapping institutions within a particular geographic region.Footnote24 In these cases, regional measures of hierarchy and differentiation may bear more directly on outcomes than global ones. The framework may also reveal heterogeneity of architecture within regime complexes: A subset of institutions in a regime complex may feature hierarchical authority relations with each other, while authority is contested within another subset of institutions in the same issue area. We view the applicability across multiple levels of governance as a key strength of the theory.

We are not the first to disaggregate the concept of regime complexity and have benefitted from others’ work in doing so. But we believe that our particular breakdown has three distinct advantages. First, our framework is general; it applies to all clusters of institutions that qualify as complexes under our definition. Second, it is mutually exclusive; we have endeavored to specify the dimensions distinctly. Third, we harness our scheme to the task of identifying falsifiable expectations in advance – both with respect to institutional architecture and with respect to cooperation outcomes – and testing them in a positive framework.

Hierarchy, differentiation and cooperation in regime complexes

Our goal in identifying this set of salient dimensions is to highlight important variation across regime complexes and understand their effects on outcomes of interest. This approach allows us to build conditional theories of regime complexity. It assumes there is no simple linear relationship between the emergence of a regime complex and outcomes, such as compliance with international rules. Instead, we must identify the ways in which overlapping agreements and organizations are arrayed vis-à-vis each other to understand such effects.

Origins of architecture

The sources of hierarchy and differentiation in regime complexes are multiple. Existing work demonstrates that, while the architecture may partially arise from actors’ strategic design choices, it often reflects uncoordinated action, characteristics of the issue area or historical contingencies. We consider each in turn.

Functional arguments about regime complex architecture draw a link between patterns of institutional interaction and efficient governance of the issue area. In these accounts, states, institutional bureaucrats or other actors build links among institutions in order to improve performance and maximize joint gains. Johnson and Urpelainen (Citation2012), for example, argue that states choose to integrate regimes characterized by negative spillovers to prevent the degradation of cooperation. Gehring and Faude (Citation2014) argue that institutions and their members adapt the scope of institutional operation and authority in order to reduce turf wars and provide global public goods. Member states must be complicit in this emergent division of labor, and secretariats have substantial agency in modifying the institutional mission.

Others argue that hierarchy and differentiation (or lack thereof) in a regime complex stem from the uncoordinated behavior of states as they jockey for advantage. Morse and Keohane (Citation2014) describe how state, nonstate and institutional actors use some multilateral institutions to challenge others, reducing both hierarchy and differentiation in the regime complex. Henning (Citation2017) examines regime complexity in the euro crisis, describing how states shaped interinstitutional relations among the ‘troika’ to maximize their control over institutions. Meanwhile, Pratt (Citation2021) argues that states proliferate overlapping institutions to strengthen their leverage over negotiations. These arguments predict that principals will sometimes trade off substantive efficiency in pursuit of greater influence over multilateral outcomes.

Additional work points to exogeneous constraints of the issue area as drivers of regime complex architecture. Lipscy (Citation2017) and Kijima and Lipscy (Citation2023) in this special issue argue that in issue areas characterized by strong network externalities, high barriers to entry and exclusivity, states will have fewer institutional options, competition among institutions will therefore be subdued, and institutions will be less responsive to changes in principals’ preferences and power. Abbott et al. (Citation2016) draw on organizational ecology to analyze patterns of growth and change in global governance institutions. Highlighting organizational density and resource availability, they argue, inter alia, that private transnational organizations are more likely to divide labor by seeking regulatory niches than intergovernmental organizations.Footnote25

Recent work applies insights from historical institutionalism to the sources of regime complex architecture (Fioretos, Citation2017). Focal institutions are often the original recipients of grants of authority, have inclusive membership, predate other institutions in the issue area and thus a likely source of path dependency.Footnote26 Regime complexes that emerge around these institutions – the World Bank for development finance and the IMF for crisis finance, for example – are likely to be more hierarchical as the incumbents defend their seniority relative to later entrants. Where a focal institution does not exist, as in the early climate change complex, authority relations may be less hierarchical.

Our framework and the contributions to this special issue build on these insights. We privilege two primary sources of regime complex architecture: Strategic attempts by principals to shape the architecture to their advantage and characteristics of the issue area. Our contributing articles highlight patterns of authority and differentiation that often emerge from contested political processes. As principals attempt to construct a regime complex that suits their interests, they must confront coalitions with different preferences and grapple with the underlying constraints of the policy domain (Eilstrup-Sangiovanni, Citation2023; Kijima & Lipscy, Citation2023). Powerful states have a heightened ability to shape institutional outcomes (Pratt, Citation2023), but weaker actors maintain the ability to create alternative institutions and construct regionally tailored authority relationships (Henning, Citation2019, Citation2023). Even the definition of ‘issue area’ is subject to political contestation, as states, firms, and other actors advance competing policy frames that encourage particular governance arrangements (Hofmann & Pawlak, Citation2023).

This conception of regime complex emergence suggests two important lessons for our theory with respect to the performance of regime complexes. First, to the extent that uncoordinated action, issue-area characteristics and historical contingency are determinants of hierarchy and differentiation, the potential for architecture to exert independent causal effects on state behavior is enhanced. Second, regime complex architecture is susceptible to long-term dynamic change. In addition to responding to shifts in state power, preferences or features of the exogenous environment, regime complexes can create endogenous feedback processes that drive further evolution. We return to this point in Section 5.

Consequences of architecture

We now turn to explaining the effects of hierarchy and differentiation. We focus on two categories of outcomes which impact the overall quality of international cooperation as reflected in, for example, environmental protection or economic development. These outcomes are shaped by the architectural features described above.

Behavioral Adjustment: Do states or other actors adjust their national policies or behavior to comply with institutional rules? Adjustment will coincide closely with the consistency of rules and standards of the institutions. Consistency supports adjustment by preventing forum shopping and reducing uncertainty over international obligations, while rule conflict tends to undermine it.

Regime Shifting and Creation: How do actors contest institutional outcomes with which they are dissatisfied? When disaffected from their regime complexes, actors can push to adopt one or both of two cross-institutional strategies. They can recruit other institutions to produce more favorable outcomes (regime shifting) or create new institutions to support such cooperation (competitive regime creation).Footnote27

We wish to emphasize the firm distinction between forum shopping and regime shifting,Footnote28 as the two concepts have sometimes been confused. Principals select among alternative venues within a fixed set of choices in the case of forum shopping, whereas regime shifting expands the set of institutional choices; shifting alters the scope for shopping. While forum shopping is operational and affects policy adjustment, regime shifting is a long-term institutional strategy.

Hierarchical authority relations and institutional differentiation shape these outcomes by constraining the ability of actors to maneuver around and within institutions in the regime complex. In this section, we first describe the independent effects of each dimension on policy adjustment and strategies of contestation. We then consider interactive effects, presenting the four ideal-type combinations of hierarchy and differentiation. While we advocate treating these dimensions as continuous rather than dichotomous, we illustrate with cases that are near the limits in order to clearly distinguish expected outcomes.

Independent effects

The principal effect of hierarchy is to discourage the adoption of conflicting rules and standards across the regime complex. As authority relations become more hierarchical, we expect the complex to produce less rule conflict and higher behavioral adjustment. Hierarchical patterns of authority encourage harmonization of rules, as peripheral institutions explicitly or implicitly recognize the authority of a more central governance body. More authoritative institutions have a greater ability to impose rule consistency on the regime complex, including via strategies of orchestration. The reduction in rule conflict should increase policy adjustment in two ways. First, it will constrain opportunistic forum shopping by actors seeking to escape compliance with intrusive rules. Second, it prevents competing rules from creating uncertainty over which obligations bind state behavior, thereby sustaining the reputational cost of rule violations.

While hierarchical regime complexes extract more behavioral adjustment from states, they may also be less adaptable than non-hierarchical architectures.Footnote29 If shifts in state power or preferences make bargaining intractable in a central institution, disputes will remain unresolved within the regime complex in the short run. The lack of rule conflict means that states that prefer alternative governance arrangements cannot simply shift venues to another institution. In the long run, the absence of institutional alternatives prompts principals who are dissatisfied to create new institutions that compete with existing ones, challenging the existing hierarchy.

Differentiation operates by reducing functional overlap and thereby limiting actors’ outside options for any given institution. When the institutions of the complex are undifferentiated, that is, functionally substitutable, we expect greater potential for rule conflict, more states engaging in forum shopping, and fewer actors adjusting their behavior to move into compliance. Institutions performing the same functions will be more likely to experience jurisdictional conflict, raising the likelihood that competing rules will emerge and persist. Strategic actors may exploit these differences via forum shopping.Footnote30 Since institutions are substitutable, states are free to engage in regulatory arbitrage, selecting into institutions with weaker compliance standards that demand less policy adjustment. The lack of differentiation encourages competition among institutions in the regime complex, potentially making them more responsive to changes in state interests and power.Footnote31 Dissatisfied coalitions can enact change with relative ease by simply shifting venues from one institution to another.

A high degree of functional differentiation reduces the potential for both rule conflict and forum shopping because separate institutions focus on distinct sub-issues. An emergent division of labor may capture efficiencies associated with comparative advantage, and differentiation reduces opportunities for regulatory arbitrage. The tradeoff, from the perspective of principals, is the potential for greater agency drift by institutional actors. Differentiation reduces the ‘policy area discipline’ (Lipscy, Citation2017) that is imposed on institutions by competition. As functionally differentiated institutions develop unique capacities, expertise, and legitimacy, they may become less responsive to their principals. In these regime complexes, dissatisfied actors are more likely to engage in competitive regime creation because the scarcity of institutions with overlapping mandates renders regime shifting less viable.

Joint effects

Levels of hierarchy and differentiation vary independently, with important consequences for the performance of the regime. describes the joint effects of authority and differentiation. The horizontal axis depicts relations of authority, with low values representing non-hierarchical arrangements and higher values representing greater hierarchy among institutions. The vertical axis reflects differentiation, distinguishing between specialized and undifferentiated institutions. The corners of this two-dimensional space represent four distinct types of architecture.

Below, we theorize the expected outcomes for each corner and illustrate by applying to several issue areas. To measure hierarchical authority relations in a regime complex, we ask two questions: Does one (or more) institution have the implicit or explicit authority to direct other institutions in the complex? Do common principals favor one institution over others? This dimension thus has legal, institutional and third-party aspects, but in each case, there should be evidence of the subordinate institutions’ explicit or implicit acknowledgment of the rightful rule of the more authoritative.Footnote32 To identify the degree of differentiation among institutions, we look for functional and geographic specialization. Functionally differentiated institutions are specialized substantively or in the type of governance activity they provide.Footnote33 Geographically differentiated institutions have specialized expertise or jurisdiction that is spatially defined.

Hierarchical-differentiated

Regime complexes that are characterized by strong hierarchy among differentiated institutions (the Northeast corner) offer little room for forum shopping or otherwise playing institutions off against one another. Rules are likely to be clear and consistent, relative to contrasting architectures, and we expect policy compliance and adjustment to be comparatively strong. The peak institution will encourage harmony of purpose, while high levels of differentiation mean that programs and activities may be specialized rather than collaborative among institutions. Because institutional specialization makes it difficult for dissatisfied states to engage in regime shifting, while hierarchy creates obstacles to competitive regime creation, the bar for changing the architecture is high. Dissatisfaction tends to manifest as contests between status quo and disaffected coalitions within existing institutions rather than as changes to complex architecture. Changes to the architecture are possible, but dissatisfaction must be greater and more sustained than in other types of complexes to produce regime shifting or creation.

The regime for international financial regulation provides a useful illustration of a hierarchical-differentiated complex. Global governance takes place in a cluster of more than 20 standard-setting bodies (SSBs) such as the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, International Organization of Securities Commissions, and International Accounting Standards Board. These operate under the aegis of the Financial Stability Board, which Walter (Citation2019) describes as the ‘peak body.’ The SSBs exhibit significant functional differentiation, addressing securities regulation, accounting standards and assessment of banking risk, for example. Consistent with our expectations for complexes in this space, we observe a low degree of competition among SSBs in finance, relatively little forum shopping and pressure for compliance. Moreover, despite discontent with their influence in these bodies, emerging-market countries have not promoted alternative forums.Footnote34 Regime shifting and competitive regime creation are thus rare to nonexistent.

Hierarchical-undifferentiated

Where a regime complex is hierarchical but undifferentiated (Southeast corner), we expect more rule conflict (and associated forum shopping) than in the case of hierarchical-differentiated complexes, but we also expect the institution at the pinnacle of the hierarchy to constrain it. Compliance and behavioral adjustment on the part of principals are likely to be intermediate, greater than in the case of non-hierarchical-undifferentiated complexes but less than hierarchical-differentiated ones. Because institutions are more substitutable than in the differentiated cases, principals will be able to explore regime shifting, particularly as their preferences and relative influence evolve over time. We thus expect complexes with this architecture to exhibit regime shifting more frequently than competitive regime creation.

The regime complex for peacekeeping exemplifies the hierarchical-undifferentiated category. The United Nations (UN) sits atop a complex that includes thirteen regional organizations, plus a larger number of subregional organizations, that are involved in peacekeeping.Footnote35 Conflicts sometimes arise among the institutions, but disputes are restrained by regional organizations’ reliance on UN resources and a widely shared preference for operating under its legal umbrella.Footnote36 As a result, the presence of overlapping institutions tends to improve rather than degrade substantive outcomes. Missions are usually regarded as constructive by the parties, which is indicated by steady demand for interventions and a progressive broadening of their mandates.Footnote37

Nonhierarchical-differentiated

Where complexes are non-hierarchical and differentiated (Northwest corner), it is the absence of functionally similar alternative institutions that discourages forum shopping. Differentiation reduces rule conflict, though no peak institution is available to harmonize rules when conflicts do arise. We expect intermediate levels of compliance and policy adjustment on the part of principals. We also expect weaker discipline over institutions themselves and the greater agency drift that is associated with differentiation and thus expect to observe more competitive regime creation as principals’ preferences evolve over time, because differentiation places regime shifting out of reach.

The regime complex for climate change illustrates a nonhierarchical and differentiated architecture. Climate change governance began with the 1992 adoption of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and thereafter grew to encompass a sprawling nebula of 80 core institutions, 50 additional international organizations and hundreds of NGOs and private organizations.Footnote38 While some institutions, such as UNFCCC are broad, most of these initiatives are substantively narrow, making this regime complex highly differentiated. The main carbon-emitting countries have not sought to elevate the UNFCCC as an umbrella organization; nearly all of the analysts who examine the climate-change regime complex conclude that it lacks hierarchical authority relations.Footnote39 Reduction of carbon emissions is at best patchy, with success in some areas but a failure in many others, and falls short of what is needed to limit warming to two degrees Celsius. Overall, outcomes accord with our expectations for complexes in this corner of .

Nonhierarchical-undifferentiated

Where the regime complex is non-hierarchical and undifferentiated (Southwest corner), institutions have overlapping mandates and no authority hierarchy through which to resolve rule conflicts or limit institutional competition, which will be prevalent. States and other principles have multiple opportunities for arbitrage among institutional forums and rules – the specter that haunted early regime complexity researchers. As a consequence, we predict more forum shopping and lower policy adjustment relative to other architectures, and that these complexes can exhibit both regime shifting and creation over time.

The regime complex for biodiversity is an example of this institutional architecture. Raustiala and Victor (Citation2004) originally described the plant genetic resources (PGR) complex as composed of elemental regimes that were overlapping and non-hierarchical.Footnote40 PGR governance lies in turn within a broader set of institutions governing agriculture, trade, culture and development. The UN Convention on Biological Diversity lies at the center of this expansive complex but with little authority over other institutions.Footnote41 The various elements of the complex generate rules for protection, ownership and development of biological resources that have low coherence. The rapid loss of species globally indicates that the policy adjustment has been very weak, corresponding to our expectations.Footnote42

Comparative test of the framework

The articles in this special issue test these expectations in eight regime complexes. They represent issue areas that are largely new to the research program, providing an ideal test of the hypotheses described in . Some articles focus on single-issue areas, leveraging change over time to estimate the effect of evolving architectures. Others compare regime complexes in different issue areas or examine ‘subcomplexes’ within the same issue area. Each article adopts its own methodological strategy for identifying the causal effect of regime complex architecture, using exogenous shocks, historical analysis and/or matching techniques, for example. Collectively, the articles encompass a rich mix of empirical methods and provide important new insights into the operation and performance of regime complexes.

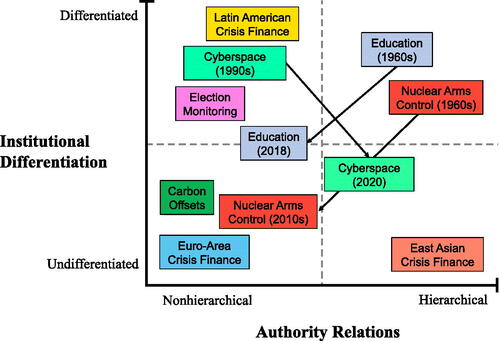

situates each regime complex examined in the companion articles within the two dimensions of architecture. For studies that trace evolution over time, we include both the initial architecture in the regime complex as well as its end point. As the figure demonstrates, the regime complexes span much of the two-dimensional space highlighted by our framework. Below, we group these complexes by their architecture and assess their correspondence with the expected outcomes.

Hierarchical-differentiated cases are represented by the complexes for nuclear arms control and education. Eilstrup-Sangiovanni (Citation2023) argues that nuclear arms control was centered on the ‘core’ of the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT) before the 1970s but included a diverse set of functionally and geographically differentiated agreements related to nuclear weapons placement, testing, materials, and technology. Consistent with our expectations, she finds a high degree of rule consistency and behavioral adjustment during this period. Kijima and Lipscy (Citation2023) argue that the regime complex for education was dominated by UNESCO in the 1960s, but that it was subsequently augmented by additional institutions, which reduced differentiation and eroded hierarchy. Notably, they find that the regime complex produced intermediate levels of behavioral adjustment – lower than expected given the architecture in the 1960s, but consistent with the ‘equilibrium’ architecture that was realized in later years. Both cases demonstrate that the substantial barriers to change in hierarchical-differentiated complexes can be overcome by strong exogenous shocks.

East Asian finance provides an example of a hierarchical-undifferentiated complex. Henning (Citation2023) argues that East Asian creditor states designed regional bodies to overlap with IMF functions, but also ensured they deferred to IMF rules and authority. As a consequence, debtor countries within East Asia have uniformly eschewed borrowing, relied on their own resources (via reserve accumulation), and pressed for modest softening of the link to the Fund (regime shifting). These outcomes are consistent with theoretical expectations.

With respect to nonhierarchical-differentiated regime complexes, Pratt (Citation2023) argues that the regime complex for election monitoring lacks an authoritative ‘core’ institution and is differentiated by both regional focus and rigor. He finds that differentiation limits opportunistic forum shopping and strengthens behavioral adjustment in the regime complex. The crisis finance complex for Latin America is also located in this corner and exhibits intermediate policy adjustment and multiple attempts at regime creation, as predicted. Hofmann and Pawlak (Citation2023) locate an earlier incarnation of the regime complex for internet and internet-related technologies there, as well.

Finally, three articles examine nonhierarchical-undifferentiated complexes: Present-day nuclear arms control, carbon-offset certification and euro-area crisis finance. Behavioral adjustment is weak in contemporary nuclear arms control (Eilstrup-Sangiovanni, Citation2023) and offset certification (Pratt, Citation2023), as expected. By contrast, however, adjustment exceeds expectations in the case of the euro area, which Henning attributes to state-sponsored collaboration among institutions.

Overall, the correspondence between expected and observed outcomes is high. Each article goes beyond simple application of the theory, however, to elaborate and extend the framework in promising ways. Kijima and Lipscy find that state power conditions the motives for differentiation in competitive regime complexes – powerful states shift the status quo by introducing undifferentiated institutions, while weaker actors seek differentiated niches. Pratt explores a novel form of differentiation, demonstrating that value-differentiated institutions generate more behavioral adjustment. Eilstrup-Sangiovanni uncovers several endogenous dynamics that have undermined hierarchy and differentiation in the nuclear arms control regime complex. Henning shows that, as a deliberate strategy of institutional control, states sometimes promote overlap while eschewing hierarchy and then improvise new mechanisms of institutional collaboration to bolster policy adjustment. Finally, Hofmann and Pawlak find that contestation over policy outcomes extends to the very definition of the issue area. Each case enriches the framework with new theoretical insights.

The evolution of regime complexes

Up to this point, our explanation for the effects of architecture has been largely an exercise in comparative statics. But our classification scheme leads readily to the question of whether and how complexes move along the dimensions of hierarchy and differentiation over time. The framework enables us to make progress theorizing how complexes evolve under various conditions.

Drawing on theories of institutions, we employ the basic distinction between exogenous and endogenous change of regime complexes.Footnote43 By exogenous change, we refer to independent shifts in the original, underlying sources of regime complex architecture identified in . These variables – transformations in state preferences and power, for example – are commonly shaped by forces external to the operation of the regime complex. As they evolve, we expect corresponding changes in hierarchy and differentiation among institutions in the complex, albeit with possible lags or distortions. Exogenous forces can act on the architecture of regime complexes in any direction. We refer to change that originates from the operation of complexes over time, by contrast, as endogenous.Footnote44 In our framework, endogenous change emerges due to feedback loops between the substantive and institutional outcomes and regime complex architecture.Footnote45

Endogenous processes of change are graphically illustrated by the two dashed feedback arrows in . The shorter arrow, linking regime creation and shifting to regime complex architecture, is relatively straightforward. Depending on the existing degree of hierarchy and differentiation, dissatisfied states may be more likely to engage in regime shifting and/or competitive regime creation. These, in turn, have direct effects on the architecture. Competitive regime creation generates new institutions that overlap with existing ones, making complexes less differentiated. Regime shifting tends to erode the dominance of the peak institution, making the complex less hierarchical. If sustained over time, these processes can move the regime complex downward in both dimensions represented in and .

The longer feedback arrow, linking behavioral outcomes to the original sources of regime complex architecture, embraces a broader set of mechanisms. In many cases, outcomes feed back into the preferences of member states. Shifts in the division of labor or authority of institutions in the complex, for example, can alter the relative influence of government bureaucracies in domestic competition over national policy. Changes in the locus of regulation-making within the complex can produce corresponding changes in the pattern of interest group lobbying at the domestic level, as some legislative committees and bureaucracies become more relevant and others less so. Each of these processes shape governments’ preferences in international cooperation. In the long run, the distributive implications of policy adjustment exacted by complexes can reshape the relative capabilities of states, and thus sow the seeds of subsequent institutional reforms by which increasingly powerful actors consolidate their gains.

Endogenous change often depends on the manner in which institutions strategically respond to jurisdictional overlap. Contributors to this volume highlight competition and collaboration as key institutional responses. Eilstrup-Sangiovanni stresses competition, which depends in part on issue-area structure, while Henning emphasizes collaboration. Both strategies are responses to the potential for conflict to which overlap gives rise – although they can be promoted by principals directly as well – and have consequences for the subsequent evolution of the architecture. Competition may ultimately produce winners and losers, contributing to hierarchy; if institutions instead avoid competing by finding niches, they differentiate. By contrast, collaboration is likely to perpetuate overlaps and less hierarchical authority relations.

Several articles in this special issue identify exogenous and endogenous mechanisms of regime complexes evolution. Kijima and Lipscy theorize that issue area characteristics (an exogenous variable) shape the evolution of the education regime complex. Low barriers to entry and the absence of network effects in the policy domain facilitate the emergence of institutional competitors, reducing hierarchy. The complex features a mix of differentiated and undifferentiated institutions, promoted by weaker and stronger states respectively. The regime complex for education originated as hierarchical and differentiated, but became nonhierarchical and less differentiated as developed countries shifted resources to institutions that better reflected their preferences, such as the World Bank and OECD.

Eilstrup-Sangiovanni identifies both exogenous and endogenous sources of evolution of the nuclear arms control complex. Exogenous shocks, including technological change and the end of the Cold War, set into motion the erosion of hierarchy and differentiation in the regime complex. Regime creation and shifting by states created a negative feedback loop in which the attrition of hierarchy and differentiation became self-reinforcing. Her contribution thus highlights endogenous processes that can fragment regime complexes, rather than enhance hierarchy or differentiation. The inherent tension between nuclear and non-nuclear weapons states over disarmament and peaceful use was an important background condition that drove this evolution.

Hofmann and Pawlak examine an important source of endogenous evolution rooted in political contestation over issue frames. Actors with different preferences have promoted a variety of alternative frames to shape governance of cyberspace in an already densely institutionalized environment. Eventually, the competition consolidated around a small number of frames, hardening substantive policy differences and simultaneously conferring authority on the multilateral institutions over plurilateral and multi-stakeholder organizations. It also underscores the possibility that endogenous preference formation is likely to be especially strong in regime complexes for newly emergent issue areas. In such environments, domestic regulatory structures, stakeholder alliances and government preferences are not yet fully entrenched and may be more susceptible to influence from international institutions.

Developing mechanisms of endogenous feedback further, we observe that the architecture of a regime complex also reshapes the information landscape for states and other actors.Footnote46 The degree of hierarchy and differentiation in the regime complex affects the diversity and quality of information that institutions disseminate, from economic forecasts to signals about state compliance. The quality of information bears not only on actors’ ability to cooperate substantively, but also on the ability of principals to foresee the consequences of their choice of architecture.Footnote47 We conjecture that, with high-quality information, successive reforms of complexes will yield stable configurations, but that complexes that generate little new or poor information are more likely to cycle through reforms of the architecture without settling into stable equilibria. Information generation will bear, in other words, on whether endogenous change is adaptive or maladaptive.

Collectively, these articles highlight a shift over time in the initial architecture that characterizes new regime complexes. The quarter century after WWII witnessed the creation of several global multilateral institutions that became the focal institutions in their respective issue areas. As Kahler (Citation2020) observes, the dramatic increase in globalization, mobilization of domestic interest groups, decline in the cost of organization (Abbott & Faude, Citation2021), proliferation of civil society organizations, and emergence of new issues on the agenda rendered global governance much more complex after the end of the Cold War. Thus, whereas new regime complexes tended to emerge in the hierarchical-differentiated corner of during the early postwar decades, they instead tended to emerge in the less hierarchical and less differentiated spaces during the two decades of the twenty-first century.

We expect that future regime complexes for new issues will continue to emerge in the nonhierarchical-undifferentiated corner, given principals’ inability to anticipate emerging issues and their tendency to create new institutions without specifying their relationship with overlapping bodies. However, our framework suggests that nonhierarchical and undifferentiated institutions are inherently competitive. Secretariats, when operating autonomously, can differentiate their institutions along lines of comparative advantage, selecting niches that reduce institutional conflict. Over time, competition will tend to establish or reinforce hierarchy by creating winners, displacing institutions, or otherwise reallocating authority to soften competitive pressure. We thus conjecture that the regime complexes in the nonhierarchical-undifferentiated corner are dynamically unstable and will often – if left to their own devices and given sufficient time – migrate toward one of the other three corners. The cases of trade in GMO products and patenting of AIDS drugs are examples where intense rule conflict eventually yielded to a modus vivendi among the institutions.Footnote48 This general trajectory may be disrupted if principals actively manage interinstitutional disputes or block mutual accommodation. But absent such intervention, we expect regime complexes to migrate away from the nonhierarchical-undifferentiated corner over time.

Conclusion

Given the increasing institutional density of global governance, theories of cooperation that do not take account of the relationships and interactions among international institutions are seriously incomplete. Continued progress in the research program on international regime complexity requires pairing the concept with conditional theories that explain variation in how regime complexes shape international cooperation. In this article, we emphasize the different patterns of institutional interaction that can emerge among clusters of institutions. These patterns alter the strategic environment in which states and other actors interact, influencing a range of cooperative outcomes in IPE.

Beyond specifying the sources of regime complexity, the main contribution of the article is articulating the effects of different architectures on substantive and institutional outcomes. We develop testable expectations with respect to all four combinations of hierarchy and differentiation, and we find that outcomes across a range of regime complexes generally correspond to our expectations. Another important contribution is theorizing the evolution of regime complexes, identifying circumstances under which their architectures become more or less hierarchical, or differentiated, over time and sorting endogenous from exogenous processes of change.

Our intention is to offer a general theoretical framework that can serve as a platform for comparative research on regime complexes and improve cumulation across studies. To that end, this special issue tests the framework’s expectations across eight regime complexes examined in five articles. We find high correspondence between the expectations of the framework and the outcomes observed in the companion articles. These articles also highlight areas where the framework and the broader research program on regime complexity require elaboration – with respect to the importance of inter-institutional collaboration and the permeability and malleability of issue-area boundaries, for example.

Overall, these contributions demonstrate the promise of the theory as a general framework, underscoring the range of issue areas and time periods in which it can be employed, while drawing on a rich diversity of methodological approaches. The ultimate test of the value of our approach is whether it enables authors to better explain the outcomes of cooperation and conflict in dense institutional settings, facilitates discovery of new causal channels, and improves cumulation of research across studies.

Our special issue in RIPE also helps to pave the way for further progress specifically on several major themes of contemporary IPE scholarship. Using this framework, IPE scholars can extend comparisons of historical trajectories of complexes, as theories of regime-complex evolution remain under-explored terrain. We can analyze the effects of the dramatic increase in institutional density in the areas of trade, aid and finance on economic development and financial stability, for example, which remain vitally important questions, as does the effect of hierarchy and differentiation on institutions’ ability to take up the global commons agenda. Our project further speaks to the ability of emerging powers, such as China, India and Brazil to influence global economic governance and patterns of economic exchange. The framework suggests that the architecture of relevant regime complexes will shape the influence and strategic choices of challenger states in the global political economy.

Our special issue also suggests several further steps to continue advancing the regime-complexity research agenda. First, scholars should establish and refine metrics for authority relations and differentiation that can be deployed comparatively. Scholars have developed measures of hierarchy, and to a lesser extent differentiation, but would benefit from refashioning them for analysis of interinstitutional interaction as well as configuring them to be applicable across, not simply within, different regime complexes. Similarly, our touchstones for outcomes, behavioral adjustment and dissatisfied actors’ strategies, would benefit from more detailed specification in forms that facilitate cross-complex comparison. Quantitative measures of institutional competition and collaboration can reinforce the use of comparative case studies and process tracing to ensure findings are robust across different methods.

Finally, our field of scholarship would benefit from developing normative approaches to the design of complexes to enhance the substantive quality of governance, improve information, bolster the resilience of well-performing institutions and facilitate reform of under-performing complexes.

Acknowledgments

For valuable feedback on earlier drafts, the authors wish to acknowledge Kenneth Abbott, Karen Alter, James Boughton, Sarah Bush, Richard Clark, Jeffrey Colgan, Christina Davis, Frieder Dengler, Mette Eilstrup-Sangiovanni, Benjamin Faude, Orfeo Fioretos, Philipp Genschel, Stephanie Hofmann, Miles Kahler, Robert Keohane, Phillip Lipscy, Axel Marx, Jean-Frédéric Morin, Julia Morse, Abraham Newman, Ayse Kaya Orloff, Louis Pauly, Claire Peacock, Kal Raustiala, Bernhard Reinsberg, Duncan Snidal, Randall Stone, Andrew Walter, Hongying Wang, Oliver Westerwinter, Jacob Winter, Tina Zappile, the RIPE editorial team, and three anonymous reviewers and are especially grateful to those people who provided written comments. Sahil Mathur provided both excellent comments and research assistance. The article also benefits from presentations to the workshop on international complexity at the Schuman Center, European University Institute, Florence, May 28–29, 2019; APSA panel on ‘Emergent Order in International Regime Complexes,’ in Washington, DC, 31 August 2019; SIS PhD symposium at American University on 18 September 2019; conference on ‘Navigating Complexity: Understanding Interactions between International Institutions,’ organized by ESADE and IBEI, Barcelona, January 23–24, 2020; Political Economy of International Organization conference, Vancouver, British Columbia, February 20–23, 2020; and two workshops of the project on international regime complexity organized online through American University, July 16–17 and December 10–11, 2020, which received support from the Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI). We apologize in advance to anyone who we might have omitted inadvertently.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

C. Randall Henning

C. Randall Henning is Professor of International Economic Relations at the School of International Service at American University in Washington, DC.

Tyler Pratt

Tyler Pratt is Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Notes

1 See, among others, Aggarwal (Citation1998), Alter and Meunier (Citation2009), Biermann et al. (Citation2009), Davis (Citation2009) and Raustiala and Victor (Citation2004).

2 See Keohane and Victor (Citation2011), Kelley (Citation2009) and Lesage and Van de Graaf (Citation2013).

3 For exceptions, see Johnson and Urpelainen (Citation2012) and Orsini et al. (Citation2013).

4 Building upon, for example, the project edited by Fioretos and Heldt (Citation2019), Heldt and Schmidtke (Citation2019) and Fioretos (Citation2019) therein, Weaver and Moschella (Citation2017) and Faude (Citation2020).

5 For a recent review, see Alter and Raustiala (Citation2018).

6 Raustiala and Victor (Citation2004); compare also to Keohane and Victor (Citation2011) and Nye (Citation2014). For discussion, see Ruggie (Citation2014) and Van de Graaf and de Ville (Citation2013). While Alter and Raustiala (Citation2018) argued that authority claims are inherently contestable in the international environment, we interpret contestability as one of several factors bearing on the degree of hierarchy in a regime complex. It does not require that relations of authority between institutions are completely flat or equal (Green, Citation2022), and Alter (Citation2022) accepts that there can be analytical benefits in treating hierarchy as a variable. Scholars who want to study non-hierarchical complexes can easily do so within our comparative framework.

7 We distinguish between international institutions and their stakeholders such as member states, their ministries, and private firms. Scholars using complex systems theory sometimes define a complex as comprehending governing institutions as well as their stakeholders. See, for example, Orsini et al. (Citation2020) and Morin et al. (Citation2016). Farrell and Newman’s (Citation2016) New Interdependence Approach overlaps with that paradigm. Although we do not employ complex systems theory, we nonetheless use some concepts of self-organization, emergence and adaptation that are central to it.

8 Informal mechanisms can be critical to sustaining coherence of regime complexes. Informal rules and processes are emphasized by Stone (Citation2011), Kleine (Citation2013), Christiansen and Neuhold (Citation2012) and Westerwinter et al. (Citation2021).

9 Krasner (Citation1983), Keohane (Citation1984), Kratochwil and Ruggie (Citation1986), Martin and Simmons (Citation1998) and Cohen (Citation2008), among others.

10 For example, Henning (Citation2017) describes joint decision-making procedures between the IMF and regional financial arrangements.

11 See Biermann et al. (Citation2009) on inter-organizational networking, Pratt (Citation2018) on institutional deference, and Abbott et al. (Citation2015) on orchestration. See also Johnson (Citation2014).

12 Orsini et al. (Citation2013).

13 Gehring and Faude (Citation2014).

14 Morin et al. (Citation2017). Eilstrup-Sangiovanni and Westerwinter (Citation2022) provide a useful scheme for classifying different concepts of complexity.

15 Similarly, Martin (Citation2021) advocates prioritizing continuous variables over ideal types in analysis of informal governance.

16 Our classification overlaps with but differs substantially from that of Zürn and Faude (Citation2013, p. 122).

17 Concern about endogeneity mirrors the longstanding debate about the epiphenomenality of single institutions. See, Mearsheimer (Citation1994), Keohane and Martin (Citation2003), Cohen (Citation2008) and, more recently with respect to complexes, Drezner (Citation2013). We suggest that separating feedback effects conceptually into these two types, each represented by a different dashed arrow in , can give IPE studies greater leverage over this analytical problem.

18 van Asselt (Citation2014).

19 Mattern and Zarakol (Citation2016) review alternative conceptualizations of hierarchy in international politics.

20 Abbott et al. (Citation2015).

21 In the framework provided by Jupille et al. (Citation2013), differentiation shapes the environment in which states select among institutional options.

22 Busch (Citation2007), Alter and Meunier (Citation2009), Hafner-Burton (Citation2009), Abbott (Citation2012) and Hofmann (Citation2019).

23 Waltz (Citation1979, pp. 81, 114–116, 196).

24 Henning (Citation2023) in this special issue, Haftel and Lenz (Citation2020), Haftel and Hofmann (Citation2019) and Hofmann (Citation2011).

25 See also Morin (Citation2020) and Lake (Citation2021).

26 See also Hanreider and Zürn (Citation2017); Rixen et al. (Citation2016) and Eilstrup-Sangiovanni (Citation2020).

27 Helfer (Citation2009); Morse and Keohane (Citation2014).

28 Following Helfer (Citation2009, p. 39).

29 Kahler (Citation2016, Citation2018) expects complex governance, characterized by transnational networks, private regulatory organizations and informal rule making, to be more resilient than complexes composed of only intergovernmental organizations.

30 See, for example, Hofmann (Citation2019).

31 Lipscy (Citation2015) and Hofmann, (Citation2019).

32 See, for example, van Asselt (Citation2017) and Lake (Citation2009).

33 Abbott (Citation2012) identifies four governance institutions: Rule-making, monitoring, compliance and information gathering/processing. See also Pattberg et al. (Citation2017).

34 Walter (Citation2019).

35 Brosig (Citation2015), Koops et al. (Citation2014) and Williams (Citation2016).

36 Williams and Boutellis (Citation2014) and Williams (Citation2016). Article 52 of the UN Charter encourages regional arrangements to undertake peaceful resolution of local disputes, including peacekeeping missions, but Article 53 precludes the use of force without Security Council authorization.

37 See, also, Fortna (Citation2008), Howard (Citation2019) and Carnegie and Mikulaschek (Citation2020).

38 van Asselt (Citation2014, Citation2017). See, also, Pattberg et al. (Citation2017) and Hadden (Citation2015).

39 Keohane and Victor (Citation2011); Abbott (Citation2012); Bulkeley et al. (Citation2014); Hale (Citation2017); and Zelli (Citation2011). Pattberg et al. (Citation2017) argue that fragmentation is alleviated by network connections and shared discourse, aspects of collaboration as developed in Henning (Citation2023).

40 Also see Aubry (Citation2019).

41 Morin et al. (Citation2016, p. 7); Alter and Raustiala (Citation2018, p. 7).

42 Although we tend to see normative value in effective rules, policy adjustment and cooperation per se, those judgments lie beyond the scope of this framework.

43 Greif and Laitin (Citation2004), Pierson (Citation2004), Mahoney and Thelen (Citation2010, pp. 1–37), Keohane (Citation2017) and Fioretos (Citation2017).

44 Compare to Eilstrup-Sangiovanni’s (Citation2022) distinction between ‘top-down’ and ‘bottom-up’ adaptation. Farrell and Newman’s (Citation2016) special issue offers intriguing examples of endogenous change in global politics. See, relatedly, Colgan et al. (Citation2012).