Abstract

Faced with a more multipolar world, scholars of International Political Economy are sharpening their tools to make sense of the longue durée of post-colonial institutions, international financial subordination and the quest for self-determination. This article develops the notion of ‘earnest struggles’ in Senegal’s postcolonial history and shows that successive governments have indeed tried to move their country forward against the odds. The focus is on three struggles: First, the attempts at transforming the Senegalese economy away from colonial cash crops and the influence of the French from 1960 to 1980. Second, the struggle of grappling with Global South debt crisis and the devaluation of the Franc CFA by 50% between 1980 to 2004. Third, the struggle to expand the Senegalese economy with newfound fiscal space and novel forms of external debt since international debt relief in 2004 until today. Based on financial data and interviews in Dakar and Paris, I argue that these struggles have led to some structural transformation. However, the danger of debt crisis has not gone, and economic self-determination has remained precarious. Dependence on foreign finance has stayed and reached record levels in recent years. Relative delinking and the search for regional complementarities offers a more promising avenue to break out of the structural condition of international financial subordination.

Introduction

Most African governments are not in debt default today. But they remember the 1980s’ Global South debt crisis well. Refinancing challenges are increasing. Governments hope they have diversified their financial dependencies and achieved sufficient structural economic transformation to prevent the next round of government debt crisis. If it arrived, this debt crisis’s proximate origins would lie in the interplay between precarious government finances and the longstanding reliance on volatile raw commodity exports, a structure inherited from colonial rule.

Senegal is no exception to this. Its debt to gross domestic product (GDP) ratio has risen to historically high levels, and the country has been witnessing a contested election cycle. It ended in March 2024 with leftwing president Bassirou Diomaye Faye voted into office just one week after being released from arbitrary imprisonment by outgoing president Macky Sall. Until now, Senegal has been a loyal ally to France and the so-called West and boasts one of the strongest economies in West Africa. But contrary to most other African countries (Blas, Citation2023), Senegal is still able to buy new debt on global capital markets, on the regional bond market, and continues to receive credit and aid from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank and bilateral donors. Moreover, Qatar, Turkey, and China are investing in the country, and Germany and others have expressed an interest in its soon-to-be exploited gas offshore oil and gas fields.

After Covid-19, rising inflation worldwide and distinct commodity scarcities in the wake of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, academics have been joining activists to predict ‘Africa’s new debt crisis’ (Gort & Brooks, Citation2023). They have called for the ‘Global South’s Rescue Brigade’ (Songwe, Citation2023). On the other hand, pundits are cognizant that this new debt crisis would not be ‘a facsimile of the 1980s’ (Gort & Brooks, Citation2023, p. 2) because of the new role of Eurobonds as instruments of foreign-denominated debt as well as the changing geopolitical terrain with China as a major new creditor which can be used to deflect overt Western or IMF creditor pressure.

Against the backdrop of these alarming statements, the present article adopts a different perspective on the certainty of new debt crisis. It uses the eternal recurrence of capitalist debt crisis in many areas of the Global South to zero in on the ‘earnest struggles’ successive Senegalese governments have waged to become less exposed to this threat. Adopting a focus on government action and international financial subordination (Alami et al., Citation2023), this article takes a step back to cast the analytical gaze more widely and asks what successive post-independence governments have done to protect Senegal by diversifying sources of government finance and engaging in structural economic transformation. With a focus on ‘earnest struggles’, it seeks to complement the literature on international financial subordination so far dominated by heterodox (development) economics with a lens more attuned to the political projects and policies pursued.

With this perspective on struggle amid subordination, the article partakes in the wider debate on national liberation, ‘worldmaking’ and economic and popular self-determination (Ajl, Citation2023; Amin, Citation1972; Cabral, Citation1970; Gadha et al., Citation2022; Getachew, Citation2019; Salem, Citation2020; Sylla, Citation2022) but also the more IPE-specific call for a ‘different systemic account’ (Bhambra, Citation2021) and to re-center the African continent (Fikir, Citation2023). Its underlying interest is in unearthing the earnest and partly successful attempts by Southern governments in dealing with colonial domestic structures and the structural constraints of the capitalist world market.

The choice of Senegal is based on its important role next to the Ivory Coast and Cameroon as leading economies in formerly French colonized Africa. The region has received more attention than usual in the wake of the coups in Mali, Burkina Faso, Guinea and Niger between 2020 and 2023. These are countries pestered by ‘la Françafrique’, an institutional arrangement now in competition with Turkey, China, Russia and the US. Françafrique denotes the fact that the former colonial power France has continued to meddle actively to maintain some of its diplomatic grandeur and to support some of its core corporations making healthy profits on the African continent (Borrel et al., Citation2021; Harding, Citation2024; Pigeaud & Sylla, Citation2021, Citation2024).

Leaving aside some of the more blatant expressions of Françafrique such as the military bases, military interventions and the history of coups (Pigeaud & Sylla, Citation2024), this article focuses on what Senegalese governments have tried to accomplish in terms of structural transformation and in making government finance more sustainable. The article centers these ‘earnest struggles’ in Senegal, a postcolonial political economy rarely studied in IPE.Footnote1 Senegal may stand for the many mid-sized African political economies among the continent’s 54 to 56 African nation states and for all the member countries of the 14 country Franc CFA zones in Western and Central Africa.Footnote2

Three ‘earnest struggles’ to ‘overcome’, ‘to defend’ and ‘to expand’ will be in focus: First, the oscillating attempts led by Léopold Senghor’s post-independence government to overcome the dependence on colonial peanut exports as well as the dominance of French firms within the economy. The second struggle waged under the leadership of Abdou Diouf was an existential one to defend against and navigate IMF-imposed austerity since 1980 and the 50% devaluation of the Franc CFA currency in 1994. With massive debt relief and a now more diversified economic structure and slightly improved tax revenues, the third struggle led since 2004 by Abdoulaye Wade and later Macky Sall was one to consolidate and expand Senegal into a middle-income country.

I show that the earnest struggles waged by successive Senegalese governments have, on the one hand, succeeded to achieve some structural economic transformation as some export diversification has taken place. Moreover, there has been an increase in relative amounts of available government finance. On the other hand, despite a growth in tax revenues and the ability to run larger government budgets, the structural dangers and exposure to debt crisis have not been resolved. The structure of relying on foreign financing and being exposed to the global currency hierarchy has not been overcome. That this struggle has continued to be waged with the help of foreign debt and public private partnerships for infrastructure and mining investments (Dieng, Citation2019) is the core structural reason why the Senegalese government continues to be in danger of debt crisis, despite the progress made.

With the notion of ‘earnest struggles’, I seek to suggest a term that captures governments’ attempts at structural transformation in the face of capitalist world market dependencies and the structure of international financial subordination. I identify the earnestness of these struggles through a blend of expressed intent in policies and political-economic outcomes. We can see an earnest struggle when a government has expressed the aim to diversify and, subsequently, diversification occurs. Because of the structure of international financial subordination, the path in between is riddled by the need to deal with domestic and world market pressures and constraints in currency hierarchies, volatile inflows of foreign finance and conditionalities for IMF credit. Close reading of existing literature, time series data since 1960 and interviews with government officials, bankers and activists suggest that contrary to the often rather dismissive ‘big man’, neopatrimonialism and ‘politics of the belly’ (Bayart, Citation2009) literature dominant in European and US-American political economy, successive Senegalese governments, in concert with the people, in sum, did transform the Senegalese political economy.

Yet, the notion of ‘earnest struggles’ is not meant to deny that cronyism and corruption exist among the ruling classes, as the violence commandeered by former Senegalese president Macky Sall until early 2024 underlines (Bamba Diagne, Citation2017; Dièye, Citation2017). The notion suggests that this reality of corruption is only part of the postcolonial story and that by taking a longer term and a more political economy informed perspective, we can see that export structures and government finances have diversified to some degree. Earnest struggle is a concept of nuance in the debate on African government action.

Methodologically, the analysis of earnest struggles proceeds historically and with a view to the longue durée (Koddenbrock et al., Citation2022), uses elements from process tracing, and bears a family resemblance to what Phil McMichael (Citation1990) has called ‘incorporated comparison’ (see also Arrighi, Citation1994) because of the interdependence it focuses on between the domestic and the global. Crucially, however, there is no explicit comparison. For this to occur, the analysis needs to be extended to book length or additional articles, a process that this article is part of see Akolgo (Citation2023; Coburger, Citation2022).Footnote3 This is a qualitative study that is supplemented by an analysis of trends over time. ‘Earnest struggles’ become plausible and tangible with the help of in-depth interviews with people involved in these struggles. Listening to those who have tried to move their country forward under the hardest of domestic, global and climatic conditions makes it difficult to adopt the dismissive language prevalent in the analysis of much African political economy.

The analysis of the three earnest struggles below is based on 12 expert interviews conducted between 2018 and 2023 in Dakar and Paris which complement the data analysis and were chosen for reasons of centrality in reform and financing processes in recent decades. They were identified through recommendations and snowballing (a full list is at the end of the article). The interviews lasted between 30 min and three hours and cover institutions such as the state-owned peanut company SONACOS, the leading agricultural credit bank, a former Prime Minister, a minister at-large, think tank and ministry staff, as well as activists, academics, and central bankers both at the Banque Central de l’Afrique de l’Ouest (Central Bank of West African States) (BCEAO) and the Banque de France. I have anonymized those interviews where I did not get explicit consent for using their names. The quantitative data was retrieved from the Observatory of Economic Complexity, run by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Boston, US, and mostly based on UNCTAD data, the UN Wider tax revenue database as well as the International Debt Statistics by the World Bank and the Senegalese Statistical office.

The article is structured as follows: Section one discusses the existing literature on national liberation, international financial subordination and the developmental state in Africa. Section two provides a historical and macro-overview of Senegalese political economy since independence before zeroing in on the three earnest struggles Senegalese governments have engaged in since 1960. The final section concludes.

The literature

The study of national liberation and self-determination and a closer look at how transformative or socialist ideas were used in building postcolonial societies has moved to the center of post- and anticolonial analysis of political economy in recent years. Scholar-politicians like Kwame Nkrumah, Amilcar Cabral or Gamal Abdel Nasser have become more widely known (Ajl, Citation2023; Getachew, Citation2019; Salem, Citation2020; Sylla, Citation2023a). Adom Getachew (Citation2019) proposed that scholars, activists and politicians like Nnamdi Azikiwe, W.E.B. Du Bois, George Padmore, Kwame Nkrumah, Eric Williams, Michael Manley and Julius Nyerere not only sought national liberation and self-determination but an entirely different world order and way of ‘world-making’. This idea has been fruitful for discussions about a new ‘New International Economic Order’ and an expanded BRICS project. Sara Salem’s work (2020) on Nasser’s Egyptian state-building project has emphasized the early independence years in the 1950s, continuing to the 2011 revolution analytically. Max Ajl, in turn, has focused on the work of Tunisian progressive development planners to delve deeply in the technical specificities and optimism of the will of structural economic transformation in the 1960s and 1970s (Citation2019) as well as the cross-fertilization with Chinese planning debates and practice (2023). Ndongo Samba Sylla is thinking with Samir Amin’s ideas and core tenets of Modern Monetary Theory to get out of the apparent cul-de-sac of old and tried catch-up development (Sylla Citation2022, Citation2023a, Citation2024). Sylla and Tunisian economist Fadhel Kaboub complement this with a novel focus on domestic resource mobilization (Kaboub, Citation2023; see also Koddenbrock, Citation2023). This broader post- and anticolonial debate has prepared the analytical terrain in IPE to focus on the state and its finances.

The state as active and potentially constructive agent has been making a steady comeback in the resurgent debates on industrial policy and developmental states within broader structures of dependency and international financial subordination (Gabor & Sylla, Citation2023a; Haggard, Citation2018; Mkandawire, Citation2001; Oqubay, Citation2015). At the same time, the post-financial crisis focus on the power of finance and the financial constraints states are faced with (Dafe, Citation2019; Kvangraven, Citation2021; Naqvi, Citation2022), on international financial subordination (Alami et al., Citation2023; Kaltenbrunner & Painceira, Citation2018) and the de-risking state (Gabor, Citation2021) provides a financial angle to that state activity. Mostly, however, the relationship between structural transformation and the challenge of financing government action has remained implicit. The present article seeks to flesh out the links between structural transformation and government finances more explicitly.

Pushing further the debate on international financial subordination as ‘a relation of domination, inferiority and subjugation between different spaces across the world market, expressed in and through money and finance, which penalizes actors’ in the Global South ‘disproportionally’ (Alami et al., Citation2023, p. 1363), this article studies closely governments’ earnest struggles to structurally transform and put their own financing on more solid and sustainable ground. These struggles interact with the subjugations entailed by dependence on foreign finance, the exposure to IMF austerity and World Bank debt as well as the currency hierarchies of US Dollar dominance, complemented and radicalized in the Franc CFA arrangement which makes Senegal dependent on the Euro.

It is important, then, to capture government action as the result of shifting power relations in which public and private actors (such as the government, banks, corporations, or organized labor) vie for dominance. As expressed in our article on ‘international financial subordination’, rooted in Marxist state theory (Clarke, Citation1988; Hirsch, Citation1999), ‘the state [plays] a key role in processing global capitalist class relations, in politically containing social antagonisms, and in securing the general conditions for accumulation within national territories’ (Alami et al., Citation2023, p. 1375). The state is thus by no means an innocent institution. In it, actor coalitions and industrial and agrarian sectors vie for dominance, and the state itself extracts some of the surplus created through workers’ and peasants’ labor (Amin, Citation1972; Smith, Citation2016).

On the African continent, after the colonial interlude, state(-re-) building faced particularly stiff challenges (Boone, Citation1990; Ntalaja, Citation2002; Shivji et al., Citation2020). Staff and institutional routines for an effective tax bureaucracy and slick central banking were not in abundant supply. Finance was scarce, bureaucrats had to be found and formed and the legitimacy of the newly independent state had to be gained at first and then maintained. Across the board, the new leaders had to both build a capitalist class and a sizable group of state cadres. After twenty years of expanding both the postcolonial domestic economy and the state apparatus, this process culminated in the 1980s debt crisis, which spread from South and Central America to Africa. A confluence of factors led to crisis. The Volcker Shock, i.e. Federal reserve induced high US interest rates and a resulting strong US Dollar, the slowdown of the global economy as well as a high debt stock and the tight debt servicing calendar pushed African countries into the suffocating embrace of the IMF. The IMF found a new and expanded role as a national debt manager no longer content with global macroeconomic stability only (Roos, Citation2019).

In political economy terms, African postcolonial states could no longer square the circle between the urgent need for fiscal expansion to implement structural transformation with able state cadres amid dependency on foreign imports (both in currencies and in commodities) as well as dependency on export receipts. Yet, a simplistic narrative that postcolonial governments overextended themselves and relied too much on cronyism to build the state as well as a nascent capitalist class carried the day. This has disregarded both the structural and global reasons for the crisis (Arrighi, Citation2002) as well as the ‘earnest struggles’ many post-independence governments had fought.

The last generation of Africanist political scientists, coming of age in these decades of debt crisis and structural adjustment, focused on institutionalist and governance analysis (Chabal & Daloz, Citation1999) of neo-patrimonialism and paid most attention to the local and the ‘from below’ (Bayart, Citation2009). In the neopatrimonialism literature, the state is captured by a political-economic elite which doles out favors and engages in cronyism to preserve regime stability. The African state is always close to state failure in this perspective (Wai, Citation2012). Despite Mkandawire’s (Citation2015) damning critique of that literature, most analyses of the African state have relied in one way or the other on this way of conceptualizing it (for example, recently, Cheeseman & Fisher, Citation2019). This focus came with abandoning political economy in the analysis of African politics (Mkandawire, Citation2015). The study of structural transformation and state finances, however, requires it. By approaching the state through the study of the earnest struggles national governments have fought, this article hopes to contribute to a more analytical and less pathologizing approach to the political economy of state action on the African continent (see also Koddenbrock, Citation2014).

In this sense, the article is a response to Mkandawire’s claim that ‘neither Africa’s post-colonial history nor the actual practice engaged in by successful “developmental states” rule out the possibility of African “developmental states” capable of playing a more dynamic role than hitherto’ (Mkandawire, Citation2001, p. 289). As I will show, Senegalese governments have, despite many setbacks and authoritarian tendencies, indeed transformed the country and have, at the same time, solidified the state’s financing base. That the danger of debt crisis remains has depended on the continued reliance on foreign finance and the structure of international financial subordination that comes with our reality of capitalism and imperialism.

Earnest struggles - Structural transformation and government finances in Senegal from independence until today

Senegal is known for its comparative political stability with only five presidents at the helm of its successive governments since 1960 (Riedl & Sylla, Citation2019). But this stability is currently in question and has also been more of a narrative than a historical reality, most election cycles were violently contested (Smith, Citation2021, Citation2024; Sylla, Citation2023b). The West African region is already on fire as other former French colonies such as Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger have begun to expel the French military. France has now decided to close its embassy in Niger, an unprecedented step that shows that it is losing some of its grip on the region (Harding, Citation2024). Only Ivory Coast continues to be a staunch defender of close ties with France under long-time president Alassane Ouattara who has previously been the head of the region’s central bank, the BCEAO. The particularly strong and contested political relationship between the region and France stands in marked contrast to the other economic power houses of Ghana and Nigeria and their much weaker relationship with their former colonial power Britain.

Four presidents before current President Faye, their numerous appointed governments and supporting coalitions have struggled to transform the Senegalese political economy and to secure government finance while consolidating their grip on power. Léopold Senghor was president from 1960 to 1980, Abdou Diouf (previously his prime minister) took over from 1981 to 1999, Abdoulaye Wade (previously state minister under Diouf) was in power from 2000 to 2012, and Macky Sall (previously prime minister under Wade) has sat at the helm of the government until early 2024.

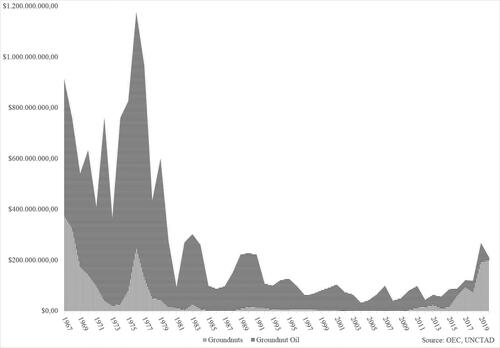

Senegal has historically hosted the ‘Four communes’ of French West Africa around the cities of St. Louis, Dakar, Rufisque and Gorée, whose inhabitants were considered French citizens since the nineteenth century (Tirera, Citation2006). Dakar was the bridgehead of French colonialism in West Africa. This configuration helped establish an urban-rural divide that has persisted to this day, as the rural areas did not enjoy the same rights. Today, the rural areas rely on agricultural production with peanuts still playing an important part (Bernards, Citation2021). As is visible in on the volatility and evolution of peanut export values below, climatic conditions—mostly dependent on the volatilities of rainfall—have been an important social factor in the Senegalese political economy. More recently, Senegal has witnessed the transformation of its second biggest city Touba into an important site of Muslim pilgrimage with the annual ‘Magal’ attracting millions of visitors from all over the world (Guèye, Citation2002). The religious leaders of the Mourides and the Tijâniyya Sufi brotherhoods play an important role in the political system next to the rural-urban divide in the Senegalese electorate.

In the monetary and financial realm, Senegal has been a user and institutional pillar of the oldest and most controversial common currency worldwide, the Franc CFA, founded in 1945 (Koddenbrock & Sylla, Citation2019; Pérez, Citation2022; Pigeaud & Sylla, Citation2021; Pouemi, Citation1980; Stasavage, Citation2003) and a member of the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU), founded in 1994. The CFA zones in West and Central Africa are known for their purposefully low inflation rates and the questionable institutional involvement of France in central banking and reserve management in its 14 member states despite the formal end of colonialism in 1960. Pegged to the French Franc first and then to the Euro, this has constituted a ‘double monetary union’ (Coburger, Citation2022), in which Euro de- and appreciations immediately reverberate across the region and impact debt service. With the West African Franc CFA zone also comes delegating monetary policy and credit support policy to the BCEAO, which, as I will discuss in the final section, has become increasingly rigid in its inflation targeting approach, has abolished monetary financing of the government and preferential access to credit for housing and agriculture.

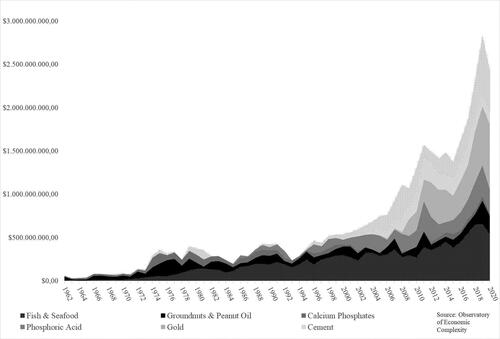

Sustaining one of the ‘cash crop economies’ (Amin, Citation1972; Mkandawire, Citation2010) during French colonialism since the mid-nineteenth century (Lewis, Citation2022), peanuts and peanut oil constituted 80% of Senegalese exports at independence in 1960 (Gellar, Citation2020). This menu of unprocessed and only slightly processed exports has over the last decades been broadened to canned fish, phosphate, phosphoric acid, cement, gold, as well as petroleum with crude oil and gas set to be sold from 2024 on (see below). Structural diversification has indeed taken place to some degree as the peanut has lost in relative export importance.

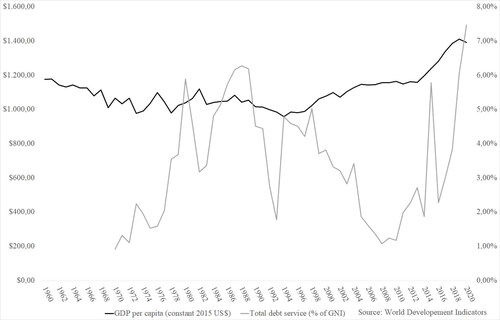

Growth per capita data (see above) suggests a modest economic success story at the aggregate national level only after long decades of decline and stagnation. Since the mid-1990s, GDP per capita has started growing and only since the mid-2010s has Senegal surpassed the levels of GDP per capita at independence. Considering the disparities between the urban and the rural areas, the situation looks less bright. The rural areas have seen a degradation in living standards since the 1994 Franc CFA devaluation (Diop et al., Citation2000, p. 162) and 90% of the rural population live under the World Bank’s poverty line (Faye et al., Citation2019, p. 45). That Senegalese economists like Ndongo Sylla explore the potential of a Modern Monetary Theory-inspired job guarantee for the rural population responds to this social challenge (Sylla, Citation2023a, Citation2024).

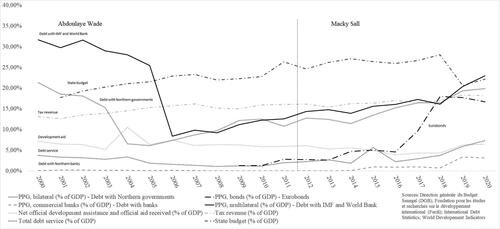

Debt service data, by contrast, indicates that a new government debt crisis may be imminent. Recent years’ steep rise in the government debt to GDP ratio (see above) is based on the continued reliance on foreign finance (multilateral, bilateral and commercial banks) including the novel billions of Eurobonds debt denominated in the Euro and US Dollar. The ‘budgetary time bombs’ planted in large infrastructure public private partnerships such as the toll road in Dakar and the new suburban train TER (Gabor & Sylla, Citation2023b) may, over time, prove to be another challenge and are not part of official debt statistics.

Senegal has historically had a large trade deficit worth up to 20% of GDP per year. Food, energy and machinery imports as well as urban luxury consumption have tended to surpass the value of the diversifying exports during the slow but steady process of structural transformation. Imports have consistently been between 7 and 20% larger than exports (World Bank, Citation2023). In that macroeconomic context, Senegalese governments have broadly relied on foreign forms of credit and aid to generate state finances and have thus had to submit themselves to the mechanisms of international financial subordination.

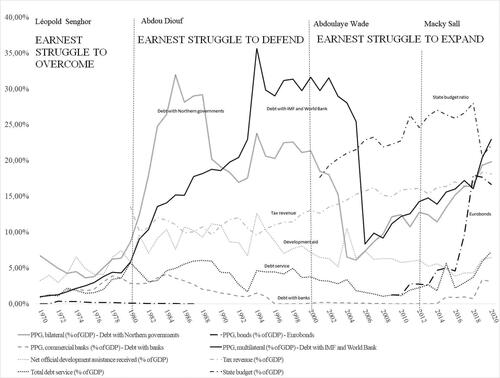

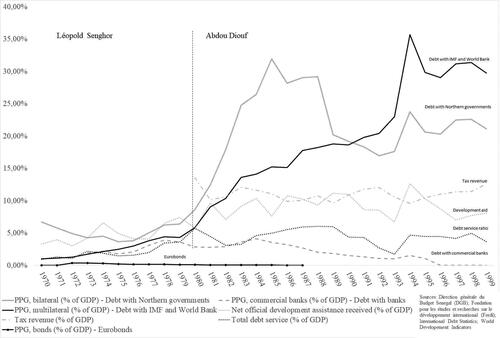

traces the most important financing relationships such as debt service ratio, kinds of debt, tax revenue and state budget from independence until today. There have been important fluctuations and a diversification of financing sources. These include rising tax revenues (from around 10% of GDP during structural adjustment to nearly 20% today) to a large increase in Eurobond issues to global capital markets. The constant rise in the relative size of the state budget since early 2000 (and a massive reduction in 2019) bears witness to this. Given that external sources of finance continue to play an important role, this diversification has not, however, removed the dependence and financial subordination to foreign currencies and financial institutions. This means the danger of recurrent debt crisis remains. The steep rise in debt service in recent years to levels beyond the past maximum in the mid-1980s underlines this looming danger for the sustainability of Senegalese government action.

Since independence in 1960, Senegal has gone through three broad eras of structural economic transformation and ups and downs of government finance. These three eras map broadly onto the presidential eras, as periods of crisis have repeatedly ushered in the ouster of the longstanding head of state. The role of foreign finance, currency hierarchies and thus of international financial subordination for demarcating these eras has been key. The first era lasted until the onset of debt crisis (because of purposeful USD appreciation) in the late 1970s through early 1980s. The second era of defense against foreign imposed Franc CFA devaluation and IMF austerity ended with massive foreign debt relief in 2004. In what follows, the article will delve more deeply into these eras by approaching them as earnest struggles of different kinds, in which the government and the social coalitions they have based their reign on, have sought to transform the country while securing the government’s own financial survival. Across these three struggles, a former senior government official claimed that ‘at the end of each year, paying public salaries [has always been, KK] difficult’ (Interview notes, Loum). The struggle for government finance has been constant.

As visualized in , the first ‘earnest struggle to overcome’ from 1960 to roughly 1980 has been against the ‘tyranny of the peanut’ and the dominance of French corporations over the postcolonial economy. In terms of government finance, this early phase amounted to nearly twenty years of ‘spending’ (Interview notes, economist, Dakar), at first through steady revenues from the continuation of the colonial peanut economy at guaranteed French prices, then bolstered by high world market prices in phosphate and peanuts until structural adjustment began in 1979 (see and above). This was the phase ‘where we had money’ (Interview notes, Loum). The ‘earnest struggle to defend’ from 1980 to 2004 grappled with 15 years of debt crisis, structural adjustment, the devaluation of the Franc CFA in 1994 and a period of ‘financial consolidation’ (Interview notes, economist, Dakar) (and social and economic suffering) culminating in 2004 in sizable Heavily Indebted Poor Countries Initiative debt relief. Yet, life in the countryside, where half the Senegalese population lives, did not improve markedly. The ‘earnest struggle to expand’ from 2004 until today in 2024 is one of consolidation and expansion, a new round of government spending but with a return to previous and even a surpassing of these debt levels. With oil and gas extraction scheduled for 2024, a phase four, with Senegal facing the challenges of windfall revenues from oil and gas, usually connected to fears of a ‘resource curse’, is about to begin. In what follows, I trace in detail the three earnest struggles the consecutive governments have waged and the outcomes they have contributed to.

Earnest struggle to overcome: overcoming the ‘tyranny of the peanut’ and breaking French control of the economy, 1960–1980

At independence, the Senegalese economy and the government’s finances were dependent on the peanut and the French. The earnest struggle to overcome during the first 20 years amounted in large parts to changing this. plots the evolution of peanut (oil) exports from 1967 to 2019 at constant 2010 US Dollars. Liberating the country from the ‘tyranny of the peanut’ has thus been a core preoccupation from the start (Interview notes, Fall). The peanut, imported in the nineteenth century from Bolivia (Lewis, Citation2022), had been turned into the dominant monoculture over the decades and made the newly independent government highly dependent on it. First president Senghor and his more radical prime minister Mamadou Dia thus embarked on a program of re-orienting the Senegalese economy towards greater self-sufficiency (Delgado & Jammeh, Citation1991; Dia, Citation1957; Diouf, Citation2015). Dia expressed the dilemma enshrined therein clearly: ‘We had to rely on the peanut to liberate ourselves from the peanut’ (Interview notes, Diallo), as, at the time of independence, peanuts and peanut oil held a share of 80% of all Senegalese export revenues and thus constituted the bulk of the influx of foreign reserves as well as trade taxes.

Most of these exports went to France under a preferential pricing system (Péhaut, Citation1961). Profits from this trade were made mostly by the urban upper class, the French (post)colonial trading houses like CFAO and Société Commercial de l’Ouest Africain (SOCA) and the Marabout religious brotherhoods in the rural areas. The four oil mills in four of the biggest cities were all foreign owned (Mbodj, Citation1991, p. 120). ‘The industrial sector was left to French capital’ (Dumont, Citation1972, p. 191).

Prime minister Dia’s first priority was to reduce foreign ownership of the most profitable economic sectors in the country. ‘The state took complete control over the sector through marketing agents, credits and subsidies, top-down cooperative structures, and price controls to break the previous dominance of French trading firms’ (Andersson & Andersson, Citation2019, p. 219). In late 1962, Dia held a speech detailing the ‘revolutionary rejection of the old structures and a complete transformation which replaces colonial society and the “trading economy” (économie de traite, KK) into a free society and an economy of development’ (Bamba Diagne, Citation2017, p. 95, my translation from the French). When he tried to resist the ensuing vote of no confidence by preventing the parliament from voting on the motion, he was sent to prison by Senghor, anxious not to displease the French too much (Monjib, Citation2005). The struggle to weaken French control was not linear. Senghor would only come back to it in the 1970s.

The social foundations of Senghor’s rule lay in the delicate balance between a majority rural population working the peanut fields, Muslim leaders from the Mourides and Tijâniyya (Seesemann, Citation2011) controlling the intermediate production and trade posts (Babou, Citation2013) as well as French and immigrant Lebanese and Syrian trading houses at the end of the export chain (Cruise O’Brien, Citation1996). The political and economic system rested on keeping these groups aligned and engaged in mutually beneficial relations. The core of this institutional balance lay in the peanut economy, which has remained at the heart of the (rural) Senegalese economy until today, although its relative importance in the total export share has decreased substantially (see and above).

Although Senghor had at first decided to transform the economy slowly and to allow the French their privileged place, after a decade of independence, the continued dominance of French (middle) management and overall ownership of the formal economy became more contested. Senghor decided to nationalize a number of key industries, water and electricity the most prominent among them (Gellar, Citation2020; Pacquement, Citation2020). Senghor now expressed the necessity of ‘a second war for economic independence and for economic control by Senegalese themselves’ (cited in Diouf, Citation2015, p. 480). As a consequence, in 1974, the French began to be legally considered foreigners. How close the relationship to the French had continued to be is strikingly obvious in the fact that they weren’t considered foreigners until then.

Senghor had prevented Dia from transforming the Senegalese economy too quickly but came to realize that the peanut could indeed no longer be solely relied on (Diouf, Citation2015). Its receipts and prices were too volatile (see ). A devastating drought in 1972 nearly halved trade value, just to rise to record heights in 1976. Senghor began pushing for diversification. That meant exporting more fish, mostly canned tuna, and the government also began to raise revenue from tourism. However, the drive for diversification stalled, as the peanut kept on giving, in volatile ways. When the oil crisis in 1973 made imports more expensive, the peanut (in tandem with phosphate) was back to finance these imports as it went through another phase of high world market prices. These easy earnings and the easy money from Northern banks looking to sell their credit after the oil crisis in 1973 lulled the Senegalese government into lavish government spending and laid the domestic foundation for the 1980s debt crisis.

The policy of nationalization and the expansion of state staff numbers increased state expenditure considerably and played an important role in the consolidation of the Senegalese middle class. Between 1970 and 1975 ‘seventy new parastatal companies were created’ (Gellar, Citation2020, pp. 66–67). This expansion was not sustainable, however, as too much of its financing had to come from outside in the form of export revenues, aid or debt (see above). Yet, in terms of structural transformation, the earnest struggle waged by the Senghor government had paid off. In the first twenty years, successive Senghor governments managed to diversify the economy from ‘peanuts only’ towards peanuts, phosphate, fish and tourism, and it broke the control of the French of the economy (see on export diversification).

The price to be paid, however, for this massive push was much higher debt levels (see and ). Expensive oil imports, massive infrastructural investments and a growing body of civil servants had grown foreign debt from 103 million USD in 1970 to 2 billion in 1982. Debt service rose from 5% in 1975 to 20% of exports in 1980 (Gellar, Citation2020, p. 63; see debt service in percent of GNI in above). Dealing with the IMF-imposed need for austerity throughout the 1980s and the implications of the Franc CFA’s devaluation in 1994 was a more defensive struggle the new Senegalese government under Abdou Diouf had to engage in.

Earnest struggle to defend: handling debt crisis and Franc CFA devaluation, 1980–2004

The Diouf governments from 1981–2000 had to defend some of the gains in structural transformation amid a severe debt crisis, IMF-imposed austerity and structural adjustment and a devaluation by 50% of the Franc CFA currency. Diouf was a skilled technocrat who had begun in Senghor’s administration at the age of 26 in 1960 after being trained in St. Louis and Paris at the elite school for cadres in the colonial areas ENSOM (Tirera, Citation2006, p. 68). His earnest struggle had to deal with a lot more foreign intervention and pressure than Senghor. The latter had enjoyed the relative leeway of the first two post-independence decades complete with a developmentalist pro-state orientation.

The 1980s debt crisis and the decades that ensured severely restricted that freedom of action. In Senegal, the debt crisis was essentially a result of worsening global credit conditions and, in principle, based on the previous inability to entirely re-structure the post-colonial economy in just 20 years to become more self-sufficient. More fundamental structural transformation would have entailed a further decrease in dependence on exports for foreign exchange revenue and less dependence on foreign finance (for an overview of government finance in this era, see ). Institutionally, the domestic banking system, painstakingly built as an attempted alternative to the large French banks still operating in the country (Dieng, Citation1982; Diouf, Citation2015) was wiped out (Koddenbrock et al., Citation2022). What had been attempted in terms of greater financial self-sufficiency was lost. Building an industrial structure that is ‘dense and integrated, instead of the current structure which struggles to respond to the fluctuations of the international conjuncture’ (Kane, 1986, p. 23, translation by author, quoted in Fall Citation1997, p. 15) had repeatedly featured in public proclamations but seemed impossible to implement.

Figure 5. Senegalese government finance during the earnest struggles to overcome and to defend (1970–1999) in % of GDP.

The middle class built on an expanded public sector, and the creation of parastatals was one of the main targets of IMF supported structural adjustment (Baumann, Citation2016). The class compromise developed over two decades had to be torn down. Senghor’s successor Abdou Diouf took it on himself from 1981 to instead assure a steady and growing revenue stream from international donors and creditors to reduce debt and to cut down the public sector without creating too many disgruntled adversaries. On superficial reading, IMF-imposed austerity was successful with the inflation rate going down from 9 to 2.5% and the budget deficit from 8.8 to 2.5% (Gellar, Citation2020, p. 72). The economy, however, hardly grew. In 1993, it shrank by 2.1%, the year before the Franc CFA devaluation (ibid.; also see on GDP per capita).

The ‘New Agricultural Policy’ as well as the ‘New Industrial Policy’ designed by the Diouf government under the aegis of the IMF essentially meant reducing state involvement in the economy and cutting formal economic sector jobs. In an extensive interview after his departure from power, Abdou Diouf described in vivid language the strong-arming by the IMF at the time:

‘[t]he IMF and the World Bank told me that rice and sugar prices were too low, and that it was not right for me to subsidize these products. They asked me to proceed to the “truth of prices” (verité des prix, KK). I had to do it, otherwise I wouldn’t get the credit I needed to run the State and finance my projects’ (Tirera, Citation2006, p. 192, translation KK).

In addition to the structural adjustment programs which already hit the majority of the population through increased consumption prices and a massive loss in jobs, the devaluation of the Franc CFAs in 1994 by 50% came as a further shock. It confirmed that France and the IMF were calling the shots on monetary policy, not the West and Central African heads of state who had all opposed it (Pigeaud & Sylla, Citation2021). The devaluation policy assumed that a further loss in purchasing power among the broader population and more expensive imports would be offset by massive gains in export productivity. In the short-term, only tourism experienced a growth in demand because Senegal suddenly became more affordable. A potential mid-term effect, however, was the further gravitation towards more diverse exports. At the end of the 1990s the long-term diversification had continued; now groundnut, phosphates, fish and tourism accounted for 80% of all exports (Mbaye & Stephen, Citation2002, p. 223).

There are more positive readings of the devaluation. In terms of aggregate data, GDP per capita began to rise (see above). Azam has argued that the devaluation freed considerable government resources because of the real wage decrease it entailed for civil servants. That the story of a bloated public sector—a favorite among neoliberal politicians—isn’t the whole story, as evident from the asides in Azam’s analysis: ‘Unfortunately, while reforms were seriously starting in some of the countries of the [CFA, author] Zone, the terms of trade of the most important CFA economies deteriorated markedly, and so for several years, from 1987’ (Azam, Citation2007, p. 4). For the analysis of earnest struggles among international financial subordination, this link between the terms of trade and that the fiscal crisis of the Senegalese state at the time underlines that it is not just about public sector wages and staff numbers but also about world market volatilities entirely beyond the purview of the government.

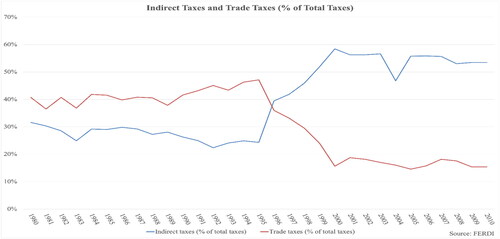

Until structural adjustment since the 1980s, customs income, and thus trade taxes, had been the main source of sovereign income in Senegal (Diouf, Citation2021, p. 76). Until 1977, conspicuously exempt were imports from the European Economic Community (the predecessor of the EU) (ibid, p. 80). Since the onset of structural adjustment, customs duties had been lowered across the board—facilitating import and export relationships—and required other taxes to pick up the bill. With accession to the World Trade Organization in 1995 and the founding of the West African Economic and Monetary Union modelled on the EU, Senegal had to abolish most of its import taxes and tariffs and thus begun to rely more heavily on value added tax (VAT) income to generate state finances. VAT is hitting the poor always relatively more than the rich (see above).

Figure 6. The shift from trade to indirect taxes (adapted from Diouf (Citation2021, p. 89)).

At the end of the earnest struggle to defend waged by the Diouf governments from 1981–2000, most of the building blocks of Senegal’s contemporary political economy were in place. Structural transformation away from the colonial economic structure has been achieved to some degree. Senegal now boasts an export-oriented economic structure relying on several minimally processed primary commodities, a government that continues to rely on aid and foreign finance and, increasingly, on VAT tax income. The third struggle I present here thus builds on a modestly structurally transformed political economy and, a moment of a relatively promising position of non-excessive debt service, debt stocks and more internationally competitive exports through a devalued currency.

Earnest struggle to consolidate and expand: capitalizing on debt relief and global capital markets 2004 until today

The third earnest struggle to consolidate and expand essentially continued on the path built by the Diouf governments including modest gains in diversification and continued reliance on foreign finance. The hard-won gains in diversification of exports and finances still came up against the structure of international financial subordination.

As visualized in above, the twenty years from 2000–2020 from Abdoulaye Wade to Macky Sall witnessed substantial debt relief in 2004 and opened opportunities for larger investments in infrastructure (Diop, Citation2013, p. 37). In the following years, both the Wade and the Sall governments tried to consolidate export diversification, but they also substantially expanded the government budget, tax revenues, and incurred new debt from multilateral and bilateral financial institutions, through bank loans and selling government bonds to arrive at the highest debt-to-GDP ratio in Senegalese history.

Figure 7. Senegalese government finance during the earnest struggle to expand 2000–2020 in % of GDP.

President Wade initiated an earnest attempt to consolidate and expand the Senegalese economy by, again, maintaining less of an emphasis on the peanut, which continued to employ large parts of the rural population, but whose export had stabilized at a low level (refer to above). Novel agricultural initiatives like the Plan ‘Retour Vers l’Agriculture’ (REVA, Return to Agriculture, KK) and ‘Grande Offensive Agricole pour la Nourriture et l’Abondance’ (GOANA, Big Agricultural Offensive for Food and Abundance, KK) (Guèye, Citation2008, p. 18) did not even mention the peanut. On paper, it looked as if the ‘tyranny’ was over. Although these ‘offensives and initiatives’ were severely underfunded (Guèye, Citation2008, pp. 20–21), a slow diversification within the agricultural sector itself indeed took place. Government policies yielded specific results. Beans, tomatoes, rice and other important food items increased their share, and Senegalese farming operatives could begin to argue that food self-sufficiency was now ‘a matter of political will’ (Jeune Afrique, Citation2015).

In 2012, Macky Sall beat Abdoulaye Wade in contested elections because the outgoing president had attempted to install his son Karim Wade as his successor. Sall inherited the best economic constellation since independence. The overall debt-to-GDP ratio was still relatively low after the 2004 debt relief (see above), and Senegal’s exports had just entered a commodity price boom—phosphate, cement and gold generated much higher returns than in the early 2000s. Macky Sall, like other presidents before him, had previously been prime minister under the acting president. Sall seized the day and embarked on an ambitious but export-oriented ‘Plan Sénégal Émergent’ aiming to turn Senegal into a middle-income country by 2035. Yet, the struggle for consolidation and expansion has been a precarious one, mainly because of the continued reliance on foreign financing (see ), the prime reason why debt crisis today is a possibility—but not a certainty.

There is, however, a more domestic and regional side to the Wade and Sall governments’ attempts to generate financing for their policies. Faced with the ‘dilemmas of externally financing domestic expenditures’ (Fischer, Citation2017), both have struggled, and managed to some degree, to increase domestic financing sources via taxation. The tax revenue composition and the heavy reliance on VAT by nearly 60% of tax returns since accession to the WTO and WAEMU ( above) highlight the challenges to Senegalese government financing from taxation.

As a matter of contextualization, the VAT share of total tax revenue has also been rising in OECD countries, but from a much lower level of 12% in the mid-1960s to 21% in 2020 (OECD, Citation2023). Africa has the lowest tax revenue to GDP ratio in the Global South, estimated at 17.2% in contrast to 22.8% in Latin America and the Caribbean and 34.2% among the OECD member states (OECD, Citation2021). The surface reasons for that predicament are well-known: A large, so-called informal sector which is hard to tax and is often purposefully not taxed because incomes are low. The VAT share of nearly 60% in Senegal indicates the inability or reluctance of successive Senegalese governments to tax the wealthy or the corporations in the country. Since VAT income is a direct function of economic performance and growth each year, here, as in the diversification of exports, reliance on one principal source increases volatility of government revenues.

In terms of government finance, recent Senegalese governments have been less successful in relying on the regional central bank whose direct support to the WAEMU governments has dried up because the ideology of ‘independent’ central banking took hold of the BCEAO. Importantly, Senegal has not had a national central bank since independence. Instead, it has been serviced by the BCEAO. Since moving to Dakar from Paris in 1967, the BCEAO has pursued a rigid monetary policy, targeting inflation at around 2%, with a 20% reserves-to-credit-creation ratio (Koddenbrock & Sylla, Citation2019; Pigeaud & Sylla, Citation2021). With the last reform of its statutes in the year 2000, the sole aim of price stability was reconfirmed (Lampe, Citation2022).

The BCEAO, in contrast to most central banks worldwide, has not departed much from its conventional and non-expansionary approach throughout the last decades despite easing credit rules and slightly lowering the key interest rate to 2% during the Covid-19 crisis (Interview notes, BCEAO). Its balance sheet growth has been modest. That means for the Senegalese government that it essentially has had to dispense with the central bank as an ally in securing fiscal space when needed. This systematically increases the danger to fall back on foreign finance. Influential French economist and coveted Franc CFA supporter Guillaumont-JeanneneyFootnote4 described BCEAO monetary policy since nationalization in the late 1960s as ‘more expansionist and interventionist […] with the intention of favoring the economic development of the States of the Union, then, from 1989, […] more respectful of market mechanisms and the goal of correcting external imbalances’ (2006, p. 46). Central bank independence and ‘respectfulness’ of the market meant less fiscal space in times of need for the Senegalese governments and, necessarily, a systematic reliance on foreign finance.

Yet, as Ferguson et al. (Citation2023) have shown, central bank ‘independence’ and restraint in monetary financing has by no means historically been the norm. Europe and the US have in recent decades cultivated a belief in the independence of central banks, which has contributed to more wealth inequality. African governments have not bought into that class ‘compromise’ consistently and have tended to make use of ‘their’ central banks when needed. As recently surveyed by the IMF (2021), most African countries, including very prominently Nigeria before the recent election (Adeoye, Citation2023), use central banks for monetary financing. The BCEAO refrains from doing so while it had had initially financed up to 20% of the previous year’s government revenue directly as monetary financing. This practice was abolished in the early 2000s (Interview notes, Loum). In the past, the BCEAO even provided credit at low interest rates to agriculture and for housing (Interview notes, Loum), a practice extremely helpful for the lower and middle classes both in the cities and the urban areas.

Regional, i.e. North and West African commercial banks, in turn, also play a role in holding Senegalese government debt (BCEAO, Citation2022). For example, these commercial banks partake in the auctions of the newly created UMOA-Titres agency and hold government bonds because of their relatively secure remuneration. Government bonds the Senegalese government has issued in the regional Franc CFA currency have thus ended up in this slowly expanding commercial banking ecosystem (BCEAO, Citation2022) after it had been severely curtailed during the structural adjustment phase (Koddenbrock et al., Citation2022). Unfortunately, the BCEAO does not publish data on the relative amount of domestically and foreign-held government debt in Senegal, thus we don’t know whether this amounts to foreign or domestic debt.

Confronted with modest but rising tax revenues, a restrictive central bank, and a domestic and regional banking sector whose liquidity remains unreliable because interest rate and exchange rate movements reverberate quickly (BCEAO, Citation2022; Coulibaly, Citation2023), foreign finance has been the default solution in the contemporary struggle waged by presidents Wade and Sall. That the financial crisis of 2007–08 turned African government bonds into an attractive asset class, has come as a pleasant new resource for the Wade and Sall governments. As illustrated in , the period from 2004 until today has witnessed an increase in available government finance through Eurobonds. Senegalese Eurobonds debt in Euro and USD is currently worth 3.8 billion Euro, as well as 3.2 billion Euro worth of government bonds are denominated in Franc CFA (Data retrieved from Refinitiv, 5 April 2023). Who holds these bonds is not systematically tracked by the banking commission in the BCEAO (Citation2022).

But the interest rate rises decreed by both the ECB and the US Fed have already begun to reverberate throughout the region. Ivory Coast and Senegal have recently postponed regional bond issuance through UMOA-Titres because interest rates have no longer been attractive enough. A new IMF program negotiation has been announced (Coulibaly, Citation2023). IMF funds would come in addition to the 300 million disbursed by the organization during the Covid-19 crisis. A new debt crisis might indeed be on the horizon, as large public private partnerships engaged in under Sall’s reign have further increased the insecurities about fiscal risks and recurrence of debt. Even the IMF opines that the opacity of these contracts might pose a danger (Gabor & Sylla, Citation2023a).

However, the debt crisis is not there yet. The consecutive earnest struggles of Senegalese governments have paid off to some degree. The Senegalese economy has been transformed and funding sources diversified. Yet gains in economic self-determination take extremely long to take root amid the global structures of international financial subordination with its currency hierarchies, flows of foreign finance and its coercive international financial institutions. The most important challenge, however, is to transform the country in a way that profits the majority of the people, a path not chosen in either of the three periods of earnest struggle.

Conclusion

After 60 years of independence, Senegal is a different country. Its economic structure has been altered, and the government has developed new forms of financing its work domestically and internationally. Senegalese governments have partly succeeded to structurally transform the economy through the diversification of export commodities. Only the peanut has remained central, an important source of revenue and food for the people in the country’s rural areas. However, most of the export commodities are hardly transformed, so the narrative of transformation needs to be adopted cautiously. There have been important changes in government financing and some of the earnest struggles of consecutive Senegalese governments have paid off. However, the relative absence of central bank support, the disproportionate reliance on VAT and the fluctuating but dependent foreign finance relations indicate that, substantially and structurally, the recurrence of debt crisis will remain on the horizon for the foreseeable future.

The strong reliance on foreign finance has been a long-standing and structural problem, which is the core struggle Senegalese governments have been unable to tackle head on so far. In a capitalist and imperialist global system imposing the structure of international financial subordination on everyone, organizing an economic kick-off and catch-up process by exporting and importing necessarily comes with this problem. The IPE debate on the development state and industrial policy needs to bear this in mind (Akyüz, Citation2017). It might be time to ask serious questions about relative delinking, domestic resource mobilization (Sylla, Citation2022, Citation2023a) and strategic attempts at building regional complementarities (Koddenbrock, Citation2023; Sokona et al., Citation2023).

The need to balance the volatilities of foreign and domestic finance and a trade and climate-dependent economy with its proclivity to economic crisis has been a historical constant since independence in Senegal and many other African countries. As long as Senegal remains dependent on foreign trade and finance, fiscal and debt crisis will recur. The data and analysis in this article show, however, that debt crisis in the near future is far from certain. The sources of finance have diversified, and world market price exposure has been spread out. To reduce the threat of debt crisis further, less reliance on foreign finance is key. But this would only be possible with progressive attempts at relative delinking and a greater reliance on domestic resources. To what extent the Senegalese people are willing to pursue this path will depend on the next struggles the people and their representatives will fight in the years to come. The party programme by newly elect President Bassirou Diomaye Faye had pointed in that direction but his government’s first steps have been extremely cautious.

For the debate on economic self-determination and the state in Africa in IPE, the present analysis illustrates the use of a long-term perspective on that struggle’s economic and financial basis that goes beyond the pathologizing thrust of neo-patrimonial analysis. Transformations become more visible in the longer frame. While direct attribution to specific actors and constellations of forces requires a shorter timeframe and more detailed process tracing, the value in the longer frame lies in its illustration of change that can hardly be denied. The data and interviews provided in this article make it very clear that the Senegalese political economy has evolved. These changes force us to look harder for how they may have come about. Once forced to look more closely, imagining a constructive role for African governments’ earnest struggles becomes both an analytical and political possibility again. Seeing and harnessing this possibility is an analytical and political must in times of increasing multipolarity and a resurgent Global South.

For the study and practice of structural transformation amid international financial subordination, this case study of Senegal’s earnest struggles highlights the need to reflect very seriously on the amount of world market integration, foreign currency and debt usage in countries with a medium-sized population, with a mostly agrarian political economy, which is also heavily exposed to worsening climatic conditions. While Samir Amin has stressed that de-linking will always and everywhere be relative delinking in key areas, the quest for regionally complementary economic structures and regional industrial policy will be key. Breaking out of colonial and imperial trade structures by reorienting trade and investment towards regional integration and cooperation will be essential. This will be no small feat amid capitalist competition and ruling classes not always intent on working with their neighbors and to the benefit of the people. Yet the modest, but real gains Senegal has made in 63 years are not sufficient to justify repeating the old liberal recipes. The rise of the Global South and more structural transformation will happen by building strong regional and continental interlinkages as de-linked from the former colonizers and the Global North as necessary. The North cannot be trusted to support the rise of the South. History and the present moment with its obvious attempts at a new scramble for Africa and its resources have proven that once and, probably, for all.

List of interviews

Interview at Banque de France, 6 December (2022).

Interview former prime minister, Dakar, 28 December (2022).

Interview with former special minister of the Wade government, Dakar, 22 December (2022).

Interview with economist, Dakar, 27 December (2022).

Interview with economist, UCAD, Dakar, 29 December (2022).

Interview with activist, Dakar, 17 November (2018).

Interview with academic, by phone, 8 August (2019).

Interview with bank director, Dakar, 6 December (2021).

Interview with historian, Dakar, 9 December (2021).

Interview with director of the board, state-owned company, Dakar, 12 December (2021).

Interview with head of aid agency, by zoom, 1 February (2023).

Interview with BCEAO economist, by phone, Dakar, 27 December (2022).

Archive visited:

Banque de France Archive, Paris.

Acknowledgements

I have accumulated many debts over the years of research for this article. I thank Bassirou Sarr who has been generous with his time and contacts but also Adama Sow and Rüdiger Seesemann. I am grateful to Ndongo Sylla and Etienne Smith for support at various stages as well as the critical readers of parts of the manuscript: Nick Bernards, Carla Coburger, Andrew Fisher, Joel Glasman, Sophia Hoffmann, Ingrid Kvangraven, Daniel Mertens, Steffen Murau, Andreas Nölke, Stefan Ouma, Yannick Perticone, Boris Samuel, Servaas Storm, and Angela Wigger. I also thank Felix Birkner for his incisive comments and help with data analysis and visualization. Thanks to Eve Chiapello for hosting me at the EHESS, Paris, to Les Afriques dans le Monde at Sciences Po, Bordeaux as well as the Institut d’Études Avancées, Paris. This article is next to a fellowship by the Alexander von Humboldt-Foundation the outcome of research conducted within the Africa Multiple Cluster of Excellence at the University of Bayreuth, funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany’s Excellence Strategy – EXC 2052/1 – 3913894.

Disclosure statement

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Kai Koddenbrock

Kai Koddenbrock is Professor of Political Economy at Bard College Berlin. He is working on economic sovereignty and self-determination in the Global South and particularly on the role of the international monetary system and global and domestic financial markets in helping and constraining this quest. He also works on geopolitics and geoeconomics and the new scramble for rare earths.

Notes

1 Notable and highly recommended exceptions have been, recently, Bernards (Citation2021), Alami and Guermond (Citation2022) and Haag (Citation2023).

2 The countries still using the initially French-imposed Franc CFA in West Africa are: Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Niger, Senegal and Togo. In Central Africa: Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea and Gabon.

3 This paper emerges from a comparative research project on Senegal, Ivory Coast, Guinea, Ghana and Nigeria which I have led since 2021. More details at politicsofmoney.org.

4 The Centre d’Études et de Recherches sur le Développement Internationale at the University of Clermont-Ferrand has been influential for French development economics on Africa and French analysis of the Franc CFA. Its founders and directors Sylviane Guillaumont-Jeanneney and Patrick Guillaumont have trained hundreds of ‘development professionals’ and continue to advise the Banque de France (Interview notes, Banque de France) and French ministries.

References

- Adeoye, A. (2023). Nigeria’s $53bn wayward means. Retrieved January 21, 2023, from https://www.ft.com/content/39a7f29c-3c5b-449d-8eb7-b26cf842748d

- Ajl, M. (2019). Auto-centered development and indigenous technics: Slaheddine el-Amami and Tunisian delinking. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 46(6), 1240–1263. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2018.1468320

- Ajl, M. (2023). Planning in the shadow of China: Tunisia in the age of developmentalism. Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, 43(3), 456–470. https://doi.org/10.1215/1089201X-10892781

- Akolgo, I. (2023). Ghana’s debt crisis and the political economy of financial dependence in Africa: History repeating itself? Development and Change, 54(5), 1264–1295.

- Akyüz, Y. (2017). Playing with Fire: Deepened financial integration and changing vulnerabilities of the Global South. Oxford University Press.

- Alami, I., Alves, C., Bonizzi, B., Kaltenbrunner, A., Koddenbrock, K., Kvangraven, I., & Powell, J. (2023). International financial subordination: A critical research agenda. Review of International Political Economy, 30(4), 1360–1386. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2022.2098359

- Alami, I., & Guermond, V. (2022). The color of money at the financial frontier. Review of International Political Economy, 30(3), 1073–1097. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2022.2078857

- Amin, S. (1972). Underdevelopment and dependence in Black Africa - Origins and contemporary forms. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 10(4), 503–524. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X00022801

- Andersson, J., & Andersson, M. (2019). Beyond miracle and malaise. Social capability in Côte d’Ivoire and Senegal during the Development Era 1930–1980. Studies in Comparative International Development, 54(2), 210–232. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-019-09283-4

- Arrighi, G. (1994). The long twentieth century: Money, power, and the origins of our times. Verso.

- Arrighi, G. (2002). The African crisis: World systemic and regional aspects. New Left Review, 15, 5ff.

- Azam, J. P. (2007). Turning devaluation into pro-poor growth: Senegal 1994-2002. Determinants of pro-poor growth: Analytical issues and findings from country cases. The International Food Policy Research Institute.

- Babou, C. A. (2013). The Senegalese ‘social contract’ revisited: The Muridiyya Muslim order and state politics. In M. Diouf (Ed.), Tolerance, democracy, and sufis in Senegal. Columbia University Press.

- Bamba Diagne, C. A. (2017). Comment votent les Sénégalais analyse du comportement de l’électeur de 1960 au 20 mars 2016., L’Harmattan Sénégal.

- Baumann, E. (2016). Sénégal, le travail dans tous ses états. Presses universitaires de Rennes/IRD Éditions.

- Bayart, J. F. (2009). The State in Africa: The Politics of the Belly. Polity.

- BCEAO. (2022). Rapport Annuel de la Commission Bancaire.

- Bernards, N. (2021). ‘Latent’ surplus populations and colonial histories of drought, groundnuts, and finance in Senegal. Geoforum, 126, 441–450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.10.007

- Bhambra, G. (2021). Colonial global economy: Towards a theoretical reorientation of political economy. Review of International Political Economy, 28(2), 307–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2020.1830831

- Blas, J. (2023). What happened to Africa rising? It’s been another lost decade. https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/features/2023-09-12/africa-s-lost-decade-economic-pain-underlies-sub-saharan-coups

- Boone, C. (1990). State power and economic crisis in Senegal. Comparative Politics, 22(3), 341–357. https://doi.org/10.2307/421965

- Borrel, T., Boukari Yabara, A., Collombat, B., & Deltombe, T. (2021). L’empire qui ne veut pas mourir: Une histoire de la Françafrique (The empire that does not want to die: A history of Françafrique collective]. Seuil.

- Cabral, A. (1970). National libération and culture. In Occasional paper. Program of Eastern African studies, Maxwell Graduate School of Citizenship and Public Affairs. Syracuse University.

- Chabal, P., & Daloz, J. P. (1999). Africa works: Disorder as political instrument. James Currey.

- Cheeseman, N., & Fisher, J. (2019). Authoritarian Africa: Repression, resistance, and the power of ideas. Oxford University Press.

- Clarke, S. (1988). Keynesianism, monetarism, and the crisis of the state. Gower Publishing Company.

- Coburger, C. (2022). Double monetary union. In M. Gadha, F. Kaboub, K. Koddenbrock, I. Mahmoud, & N. Sylla (Eds.), Economic and monetary sovereignty in 21st century Africa. Pluto Press.

- Coulibaly, L. (2023). West African countries struggle to raise funds from regional debt market. https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/west-african-countries-struggle-raise-funds-regional-debt-market-2023-04-05/

- Cruise O’Brien, B. (1996). The Senegalese exception. Africa, 66(3), 458–464.

- Dafe, F. (2019). Fuelled power: Oil, financiers and central bank policy in Nigeria. New Political Economy, 24(5), 641–658. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2018.1501353

- Delgado, C. L., & Jammeh, S. (1991). The political economy of Senegal under structural adjustment. Praeger.

- Dia, M. (1957). L’Économie Africaine. Presse Universitaire.

- Dieng, A. A. (1982). Le Rôle du système bancaire dans la mise en valeur de l’Afrique de l’Ouest., Les Nouvelles Éditions Africaines.

- Dieng, M. (2019). L’endettement du Sénégal sous Macky Sall. https://www.seneplus.com/opinions/lendettement-du-senegal-sous-macky-sall

- Dieng, R. S. (2023). From Yewwu Yewwi to #FreeSenegal: Class, gender and generational dynamics of radical feminist activism in Senegal. Politics & Gender, 1–7.

- Dièye, C. B. (2017). Thérapie pour un pays blessé., Harmattan.

- Diop, M. (Ed.) (2013). Sénégal (2000-2012): Les institutions et politiques publiques à l’épreuve d’une gouvernance libérale. Karthala.

- Diop, M., Diouf, M., & Diaw, A. (2000). Le baobab a été déraciné. L’alternance au Sénégal. Politique africaine, N° 78(2), 157–179. https://doi.org/10.3917/polaf.078.0157

- Diouf, A. (2021). Fiscalité Du Secteur Primaire Dans Les Pays En Développement Cas De L’agriculture Et Du Secteur Pétrolier Au Sénégal [PhD Defense]. CERDI.

- Diouf, M. (1992). La crise de l’ajustement. Politique Africaine, 45(1), 62–85. https://doi.org/10.3406/polaf.1992.5544

- Diouf, J. (2015). Les relations economiques et financières entre la France et le Sénégal ente 1960 et 1974 [Thèse de doctorat]. Université de Sorbonne.

- Dumont, R. (1972). Paysanneries aux abois, Ceylan-Tunisie-Sénégal. Le Seuil.

- Fall, B. (1997). Ajustement Structurel et employ au Senegal. CODESRIA.

- Faye, M., Sall, Affholder, F., & Gérard, F. (2019). Inégalités de revenu en milieu rural dans le bassin arachidier du Sénégal. Research Papers, CAIRN.

- Ferguson, N., Kornejew, M., Schmelzing, P., & Schularick, M. (2023). The safety net: Central Bank balance sheets and financial crises, 1587-2020. Economics Working Papers.

- Fikir, H. (2023). Africa in IPE theorization: Exclusion, oversight, and Eurocentrism in the field’s past and future. Review of International Political Economy, 30(5), 1660–1675.

- Fischer, A. (2017). Debt and development in historical perspective: The external constraints of late industrialisation revisited through South Korea and Brazil. The World Economy, 41(12), 3359–3378. https://doi.org/10.1111/twec.12625

- Gabor, D. (2021). The wall street consensus. Development and Change, 52(3), 429–459. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12645

- Gabor, D., & Sylla, N. S. (2023a). Dreams of green hydrogen. Boston Review. https://www.bostonreview.net/articles/dreams-of-green-hydrogen/

- Gabor, D., & Sylla, N. S. (2023b). Derisking developmentalism: A tale of green hydrogen. Development and Change, 54(5), 1169–1196. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12779

- Gadha, M., Kaboub, F., Koddenbrock, K., Mahmoud, I., & Sylla, N. (Eds.) (2022). Economic and monetary sovereignty in 21st century Africa. Pluto Press.

- Gellar, S. (2020). Senegal - An African nation between Islam and The West. Routledge.

- Getachew, A. (2019). Worldmaking after empire: The rise and fall of self-determination. Princeton University Press.

- Gort, J., & Brooks, A. (2023). Africa’s next debt crisis: A relational comparison of Chinese and western lending to Zambia. Antipode, 55(3), 830–852. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12921

- Guèye, C. (2002). Touba: La Capitale Des Mourides. Karthala Editions.

- Guèye, M. (2008). Dossier Politiques agricoles: Affaires publiques ou privees? Défis Sud, 85, 19–22.

- Haag, S. (2023). Old colonial power in new green financing instruments. Approaching financial subordination from the perspective of racial capitalism in renewable energy finance in Senegal. Geoforum, 145, 103641. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2022.09.018

- Haggard, S. (2018). Developmental states. Cambridge University Press.

- Harding, J. (2024). Zombie vs. Zombie. https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v46/n01/jeremy-harding/zombie-v.-zombie

- Hirsch, J. (1999). Globalisation, class and the question of democracy. Socialist Register, 35, 278–293.

- Jeanneney, G. S. (2006). Independence of the Central Bank of West African States: An expected Reform? Revue D’Economie Du Developpment, 14, 43–73.

- Jeune Afrique. (2015). Agro-industrie: qui va reprendre le sénégalais Suneor. https://www.jeuneafrique.com/mag/275936/economie/agro-industrie-qui-va-reprendre-le-senegalais-suneor/

- Kaboub, F. (2023). Financing sustainable economic transformation, talk held at G24 Meeting, Abidjan, July 17. https://www.g24.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Fadhel-Kaboub-%E2%80%93-Financing-Sustainable-Economic-Transformation-Domestic-Resource-Mobilization.pdf

- Kaltenbrunner, A., & Painceira, J. P. (2018). Subordinated financial integration and financialisation in emerging capitalist economies: The Brazilian experience. New Political Economy, 23(3), 290–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2017.1349089

- Koddenbrock, K. (2014). Malevolent politics: ICG reporting on government action and the dilemmas of rule in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Third World Quarterly, 35(4), 669–685. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2014.924067

- Koddenbrock, K. (2023). https://afripoli.org/german-trade-and-investment-in-africa-geoeconomics-regional-complementarities-and-domestic-resource-mobilisation

- Koddenbrock, K., Kvangraven, I. H., & Sylla, N. S. (2022). Beyond financialisation: The longue durée of finance and production in the Global South. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 46(4), 703–733. https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/beac029

- Koddenbrock, K., & Sylla, N. S. (2019). Towards a political economy of monetary dependency: The case of the CFA Franc in West Africa. MaxPo Discussion Paper 19/2.

- Kvangraven, I. H. (2021). Beyond the stereotype: Restating the relevance of the dependency research programme. Development and Change, 52(1), 76–112. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12593

- Lampe, F. (2022). Interest Rate Policy of the Banque Centrale des Etats de l’Afrique de l’Ouest: International Currency Hierarchy, Monetary Base Coverage, and Bank Lending in the WAEMU. (No. 76). ZÖSS-Discussion Paper.

- Lewis, J. (2022). Slaves for peanuts: A story of conquest, liberation, and a crop that changed history. The New Press.

- Mbaye, A. A., & Stephen, G. (2002). Unit labour costs, international competitiveness, and exports: The case of Senegal. Journal of African Economics, 11(2), 219–248. https://doi.org/10.1093/jae/11.2.219

- Mbodj, M. (1991). The politics of independence. In C. Delgado & S. Jammeh (Eds.), The political economy of senegal under structural adjustment (pp. 119–126). Praeger.

- McMichael, P. (1990). Incorporating comparison within a world-historical perspective: An alternative comparative method. American Sociological Review, 55(3), 385–397. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095763

- Mkandawire, T. (2001). Thinking about developmental states in Africa. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 25(3), 289–314. https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/25.3.289

- Mkandawire, T. (2010). On tax efforts and colonial heritage in Africa. Journal of Development Studies, 46(10), 1647–1669. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2010.500660