Abstract

In the last thirty years, international commercial courts (ICCs) have emerged around the world. ICCs offer adjudication in international commercial disputes. They are not creatures of international law – as their name may suggest – but specialized domestic courts embedded in national legal orders. The rise of ICCs is remarkable in that scholars expected commercial arbitration to gradually displace litigation in the twenty first century. What drives the creation of ICCs? Legal research suggests that ICCs are a manifestation of a new era of assertive unilateralism in global governance. Scholars point to states’ geopolitical motives, backlashes against private authority in the form of arbitration, and economic statecraft. Drawing on the New Interdependence Approach, this study argues that most ICCs are the result of policy entrepreneurship of elite law firms in the pursuit of growing the global market for commercial litigation. Depending on the legal-political context, they forge coalitions with domestic judiciaries or political leaders to advance ICC projects. The study highlights deep-rooted changes in the global dispute resolution landscape, the important role of commercial law in International Political Economy (IPE), and points to the mostly overlooked significance of law firms and judiciaries as architects of global economic governance.

Introduction

In the last thirty years, international commercial courts (ICCs) have sprung up in many jurisdictions. These courts are not rooted in international law—as their name might suggest—but are domestic courts specialized in the resolution of international commercial disputes that arise between businesses in world markets. Whereas for most of the twentieth century, the London Commercial Court was de facto the only court of this kind, now ICCs can be found inter alia in New York, Dubai, and Singapore. The rise of ICCs is remarkable. At the turn of the millennium, scholars of International Political Economy (IPE) predicted commercial arbitration to gradually displace litigation and courts in the resolution of international commercial disputes (Mattli, Citation2001; Mattli & Dietz, Citation2014). State courts and litigation were seen as inefficient, slow, and lacking in commercial expertise in comparison to private commercial arbitration. Echoing the neoliberal paradigm of the 1990s, private ordering of markets through market participants was seen as superior to public ordering through states and courts. The rise of ICCs thus comes as a surprise and triggers several questions of interest to IPE scholarship. First, why have states suddenly started creating these new institutions? Second, who are the main drivers of this innovation in global economic dispute resolution? And third, what are the broader ramifications of these developments for our understanding of IPE?

IPE scholars have paid little attention to commercial law and ICCs (Crasnic et al., Citation2017; Cutler, Citation2023; Kahraman et al., Citation2020; Kalyanpur, Citation2023). Most research on ICCs is rooted in legal scholarship. It depicts ICCs as a manifestation of assertive unilateralism in global economic governance (Brekoulakis & Dimitropoulos, Citation2022; Dimitropoulos, Citation2021). States are seen to turn away from multilateral organizations and negotiated norms and instead to pursue their interests through unilateral actions and institutions including ICCs to achieve relative gains. Legal scholarship thus implicitly endorses neo-realist theories of international relations and points to three motivations behind the creation of ICCs. Some scholars see in ICCs state instruments to pursue geopolitical interests (Chaisse & Qian, Citation2021; Gu & Tam, Citation2022; Qian, Citation2020). Other scholars imply that ICCs may form part of state efforts to curtail private authority in global economic governance as manifested in arbitration and relevant transnational regimes (Höland & Meller-Hannich, Citation2016; Meller-Hannich et al., Citation2023; Wagner, Citation2017). Lastly, most scholars see in ICCs efforts to boost the competitiveness of national economies to attract businesses and capital (Alcolea, Citation2022; Brekoulakis & Dimitropoulos, Citation2022; Dimitropoulos, Citation2021; Willems, Citation2022; Yip & Rühl, Citation2024). While intuitive, these explanations suffer from empirical and theoretical weaknesses.

This study draws on the New Interdependence Approach (NIA) (Farrell & Newman, Citation2016) to develop a societal explanation for the rise of ICCs. The NIA posits that globalization and the growing interdependence of economies and societies does not result in an anarchic world economy devoid of rules but, to the contrary, in rule overlap and norm conflicts. Non-state actors—typically businesses—may recognize this rule overlap as an opportunity to advance legal, regulatory, and institutional reforms to their benefit and build domestic and transnational political coalitions. Yet, not all non-state actors are similarly placed to take advantage of such opportunities resulting in legal, regulatory, and institutional changes that may yield asymmetric power and wealth effects. The NIA is a valuable lens to understand the dynamics of international commercial transactions and ICC creations. International commercial contracts and disputes naturally touch upon multiple jurisdictions with overlapping and often conflicting legal and jurisdictional claims (Basedow, Citation2015). Most ordinary domestic courts are seen to lack the legal and commercial expertise to navigate such highly complex cases and render high quality decisions within the time frames that businesses seek. Hence, international businesses are thought to either avoid litigation or—if impracticable—to opt for expensive yet fast, discrete, and specialized arbitration services. This study argues that specialized law firms in their pursuit of growing the market for international commercial litigation services push for the creation of ICCs. ICCs promise high quality, specialized dispute resolution yet at lower costs than arbitrators and thereby arguably increase the propensity of businesses to launch dispute resolution proceedings. Depending on the legal-political context, specialized law firms should exploit their networks to forge domestic and transnational coalitions with notable judiciaries or political leaders to advance ICC projects in jurisdictions that play or strive to play a central role in international markets.

The study uses qualitative methods. The empirics largely confirm the theoretical expectations yet deviate in two regards. First, no evidence suggests that law firms played a meaningful role in the creation of the Chinese ICC. Second, in several jurisdictions, the judiciaries played a significantly more proactive role than theorized. These observations caution that our findings are preliminary, and more research is needed to further scrutinize the role of judges, court administrations and, indeed, other non-state actors including multinational corporations and in-house counsels.

What are the broader ramifications of the study and findings for IPE scholarship? First, the study draws attention to several blind spots in IPE scholarship. Commercial law, ongoing changes in the global economic dispute resolution landscape, international law firms and domestic judiciaries have received only scant attention despite their crucial role in the global political economy (see Crasnic et al., Citation2017; Cutler, Citation2003; Efrat, Citation2016; Kahraman et al., Citation2020). Second, the study argues that ICCs are manifestations of a neoliberalization of national judiciaries. Unlike ordinary domestic courts that function according to a public service logic, ICCs are meant to internationally compete for litigation. They emulate core features of arbitration and instill a market logic into litigation. As ICCs are often designed as institutional experiments to inform future national judicial reforms, their rise is likely to leave a bigger imprint on courts, states and societies than may at first meet the eye. The twenty first century thus may not bring the demise of commercial litigation and state courts, as IPE scholars like Mattli (Citation2001) speculated, but, to the contrary, transform commercial litigation and courts in line with corporate demands. This study ties in with a broader research agenda on the redistributive and power effects of law in the global political economy (Cutler, Citation2003; Cutler & Lark, Citation2022; Dietz & Cutler, Citation2017; Pistor, Citation2019). Rather than treating the law and ICCs as exogenous neutral social coordination devices, this study cautions that they are instruments and manifestations of power struggles and social agency in the world economy.

The article is structured as follows. The first section discusses ICCs in more detail and seeks to explain their relationship to better known international economic dispute settlement mechanisms. The second section reviews the relevant legal and IPE literature and develops a societal explanation for the rise of ICCs. It formulates hypotheses, expectations and counter-expectations to structure the empirical analysis. The following sections discuss the research design, present the empirical analysis, and conclude.

International commercial courts – function and history in context

In the last two decades, ICCs have become part of the global dispute resolution landscape and global governance. Yet, no universally accepted definition of ICCs exists (Brekoulakis & Dimitropoulos, Citation2022; Gu & Tam, Citation2022; Hwang, Citation2015). Most scholars agree that ICCs exhibit four commonalities: (1) ICCs deal with transnational disputes based on business contracts, private and commercial law; (2) ICCs are courts with a standing bench of judges, who get assigned to disputes according to the operational rulebook of the relevant ICC rather than by party appointment as done in arbitration and mediation; (3) ICCs allow to varying degrees for the resolution of disputes on the basis of foreign law—typically the Common Law of England or New York—and may partially or fully operate in English or other foreign languages and provide for procedural flexibility; and (4) ICCs are meant to deal with disputes of sizeable monetary value.

Beyond these commonalities, ICCs differ in important regards. To start, ICCs exhibit diverse institutional designs. Some ICCs are essentially domestic courts—or court chambers—that have come to deal with predominantly international business disputes. An example is the London Commercial Court that transformed from a court servicing domestic commercial disputes to a global dispute resolution hub. Other ICCs are designed as standalone institutions, often located in Special Economic Zones (SEZ), and operating under constitutional carve-outs. These ICCs—namely the Courts of the Dubai International Financial Centre (DIFC Courts), the Qatar International Financial Court and Dispute Resolution Centre (QIC), Astana International Financial Centre Court (AIFCC), and Abu Dhabi Global Market Court (ADGM)—preside over their own jurisdictions and are detached from the legal order and judicial systems of their states. They adjudicate on the basis of SEZ laws that are typically modelled on English Common Law, which is seen as a particularly business-friendly and historically dominant law for the drafting and interpretation of international commercial contracts (Pistor, Citation2019). As the Gulf countries and Kazakhstan are civil law jurisdictions, it means that these ICCs and SEZs are Common Law islands (Dimitropoulos, Citation2021). Some ICCs, moreover, are open to both domestic and international disputes. Others only have standing to hear international disputes. The meaning of international disputes, furthermore, varies across courts. ICCs may only hear cases that have a legal link to their jurisdiction (e.g. through the nationality of a disputing party or through the localization of business operations or assets) or may hear cases that have no link other than party consent to the ICC’s jurisdiction. Another important difference across ICCs is the role of foreign judges. Some ICCs—notably in Europe—only have nationals serving as judges. Yet, other ICCs have almost only retired judges from English or Australian high courts on their benches. Last, ICCs differ in terms of their breadth of offered dispute resolution services. Some ICCs only provide litigation whereas others are designed as one-stop dispute resolution hubs that provide litigation, arbitration, and mediation with the possibility to switch between these proceedings. Businesses indeed often use a combination of dispute settlement proceedings and fora to ensure the swift, cost-effective, and expertise-driven resolution of disputes. Disputing business parties may start out with mediation but then switch to arbitration (‘med-arb’) or litigation in case of persistent disagreements. Or they may initially pursue litigation or arbitration and switch to mediation when potential compromises emerge (‘arb-med’).

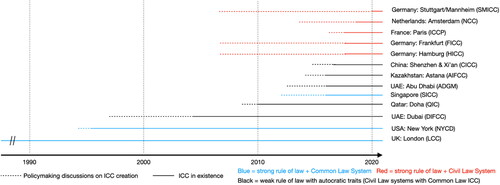

In line with the above, one can identify 13 ICCs in 11 jurisdictions in operation as of 2023 (Gu & Tam, Citation2022, p. 448) (). Apart from the ICC in London, all were founded in the last decades. The analytical focus of this study lies on these recent ICC foundations. It furthermore needs mentioning that the German ICCs in Hamburg, Frankfurt, Stuttgart/Mannheim do not constitute independent cases. These courts are organizationally independent yet are the outcome of the same initiative of the German Bar Association and legislative proposal of the Bundesrat (Wagner, Citation2017). For analytical purposes, it is appropriate to treat the German ICCs as the result of the same processes.

Table 1. Overview of operational ICCs.

What is the relationship between ICCs and other global economic dispute settlement mechanisms (DSMs)? Most IPE scholarship focuses on state-centric DSMs such as the Dispute Settlement Body (DSB) of the World Trade Organization (WTO) (Basedow, Citation2021), DSMs under Preferential Trade Agreements (PTAs) (Allee & Elsig, Citation2016), or investment arbitration (Bonnitcha et al., Citation2017). These DSMs have in common that they (1) adjudicate on the basis of international treaties between states, (2) resolve disputes on alleged breaches of intergovernmental commitments through state measures and public policies, and thus (3) involve states as disputing parties. In the case of the WTO DSB and PTA DSMs, states aggregate and represent the interests of domestic firms and workers both as claimants and as defendants. In investment arbitration, states merely act as defendants, and investors directly assume the role as claimants. The legal nature of investment disputes, however, is similar in that they revolve around the conformity of public policy and state measures with international legal commitments. From a neoliberal institutionalist perspective, these DSMs are credible commitment devices for states to address collective action problems in world politics.

ICCs, in contrast, deal with transnational disputes between businesses over breaches of commercial contracts on trade, financial, and investment transactions in world markets. Such disputes may relate, for instance, to the late delivery of goods, the delivery of faulty goods, late or non-payments, or the provision of inadequate services or liability. The triggers of commercial disputes in ICCs, in other words, are not public policy and state measures but the conduct of business partners. Hence, ICCs are credible commitment devices for businesses to address collective action problems in jurisdictionally fragmented world markets. In their function, ICCs complement the WTO DSB, DSMs under PTAs, and investment arbitration and resemble transnational commercial arbitration and litigation in ordinary domestic courts. Indeed, ICCs may be seen as novel hybrid institutions. Whereas courts typically charge lower fees and may coerce unwilling defendants and third parties to join a dispute, arbitration is faster, provides for discretion and procedural flexibility, allows for the appointment of arbitrators with sector-specific expertise, and promises easy international enforcement of awards under the New York Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards (1958). ICCs seek to combine the advantages of commercial arbitration and litigation. IPE scholars have paid remarkably little attention to this domain of global economic dispute resolution and governance even though commercial arbitration and litigation are considerably more frequent than WTO disputes or investment arbitration (Crasnic et al., Citation2017; Cutler, Citation2023, Citation2003; Hale, Citation2015; Kahraman et al., Citation2020; Mattli & Dietz, Citation2014). The globally leading commercial arbitration institution—the International Chamber of Commerce—for instance receives more arbitration requests in a single year than the WTO DSB has adjudicated in three decades.

Surveying legal scholarship on ICCs – strengths and weaknesses of existing accounts

Legal scholarship has afforded considerable attention to ICCs and points—often implicitly—to three potential explanations for the rise of ICCs. This section reviews these explanations and discusses their strengths and weaknesses. The first explanation for the rise of ICCs in the legal literature focuses on geopolitical considerations (Bookman, Citation2020; Erie, Citation2019; Gu & Tam, Citation2022; Qian, Citation2020; Yip & Rühl, Citation2024). These studies endorse neo-realist thinking in that they depict ICCs as institutions that help states to unilaterally increase their relative hard and soft power vis-à-vis peers in the global political economy. Studies that depict ICCs as tools for hard power projection mostly focus on the China International Commercial Court (CICC) (Bookman, Citation2020; Gu & Tam, Citation2022; Qian, Citation2020). They highlight that the CICC is meant to adjudicate commercial disputes tied to the Belt and Road Initiative, which aims at increasing China’s geopolitical influence, and is embedded in the highly politicized Supreme Court of China. As BRI partner countries may have to accept CICC jurisdiction and jurisprudence, the court may help China to consolidate its geopolitical power in the guise of judgements. As one lawyer commented, the CICC seems to amount to an effort to pull large geopolitically sensitive BRI disputes into politically controlled Chinese courtrooms (interview, 11 January 2023). Other studies portray ICCs as tools for soft power projection (Erie, Citation2019; Gu & Tam, Citation2022; Yip & Rühl, Citation2024). They suggest that ICCs may strengthen the role of jurisdictions as regional business hubs, export national legal and political thought, and build prestige among business and world leaders. Scholars suspect that these considerations played a role in the ICC creations in the Gulf, Kazakhstan, Singapore and indeed in post-Brexit Europe (Alcolea, Citation2022; Gu & Tam, Citation2022).

Studies pointing to geopolitical considerations behind the creation of ICCs make valuable contributions. The CICC certainly has considerable geopolitical potential. It has, however, rendered few judgements and it remains to be seen to what extent CICC jurisprudence will serve China’s foreign policy agenda. Studies focusing on ICCs as soft power tools are less convincing. These accounts are often vague, theoretically underspecified, and empirically flawed. Many studies focusing on soft power indeed blur foreign policy and economic considerations. A case in point is the treatment of the ICCs in the Gulf and Kazakhstan. These ICCs are at times described as geopolitical tools and signalling devices precisely because they are designed as apolitical and allegedly independent courts in autocracies to promote trade and investment activity. Yet, labelling ICCs as geopolitical due to their arguable lack of politicization amounts to conceptual overstretching. Lastly, studies arguing that European ICCs are geopolitical responses to Brexit are flawed in that most projects were already underway before the Brexit referendum.

Secondly, ICCs might form part of state efforts to curtail private authority in global economic governance. The rise of arbitration since the 1990s is seen to have removed large domains of private and commercial law from judicial oversight and democratic state control (Höland & Meller-Hannich, Citation2016; interview, 7 December 2022; Meller-Hannich et al., Citation2023; Wagner, Citation2017). Law, however, is a public good, whose social governance function depends on its continuous public interpretation and application. Arbitration, in contrast, is by design private and secretive. As legally complex, international, and high-value disputes almost exclusively end up in arbitration nowadays, courts are effectively prevented from interpreting, applying, and developing the law in relevant domains. The surge in arbitration is therefore perceived to endanger the effectiveness of legal orders, to harm society and to weaken the state (Alcolea, Citation2022). In line with neo-realist thinking, it is thus conceivable that states create ICCs to limit demand for arbitration and pull commercial disputes back into courtrooms and the public sphere. The recent contestation of notably investment arbitration as illegitimate, non-accountable, and biased DSM and efforts of the European Union (EU) to replace investment arbitration tribunals through a multilateral investment court under the umbrella of the UN seem to support this reasoning (Basedow, Citation2021; Bell, Citation2018).

The explanation—while at first sight appealing—is empirically flawed. All states that recently created ICCs have maintained or strengthened their commercial arbitration institutions and laws. Many ICCs are, furthermore, designed as one-stop dispute resolution hubs that offer litigation, arbitration, and mediation under one roof (Bookman, Citation2020). This assessment even holds true for Germany, where academics and policymakers have been most concerned about a decline in commercial litigation. In 2020, the German ministry of justice commissioned an expert report to identify the causes behind a drastic decrease of 33%—or 600,000 proceedings annually—in civil litigation since the 1990s and to advise on mitigation steps (Meller-Hannich et al., Citation2023). The report does not recommend limiting access to arbitration but calls on policymakers to ensure that courts develop greater commercial expertise, language and technological skills to swiftly resolve commercial disputes (ibid., 2023, pp. 334–337). The federal and regional governments and bar association, furthermore, remain keen to strengthen the role of Germany as an arbitration and mediation hub (DAV, Citation2023; Wagner, Citation2017). Lastly, public contestation of investment arbitration in ICC jurisdictions was only pronounced in Germany, France and the Netherlands. In all other countries, the public afforded little attention to the risks of arbitration, which makes it an unlikely contributing factor to the creation of ICCs.

Thirdly, most legal scholars point to economic motives for the creation of ICCs. ICCs are seen as a manifestation of ‘economic statecraft’ aimed at (1) increasing FDI and capital inflows, (2) promoting the development of the legal, financial, and professional service sectors and national economies, and (3) enlarging and diversifying the national tax base (Alcolea, Citation2022; Brekoulakis & Dimitropoulos, Citation2022; Dimitropoulos, Citation2021; Gu & Tam, Citation2022; Huo & Yip, Citation2019; Rühl, Citation2018). The causal channel that is—often implicitly—assumed to link ICCs to economic outcomes is the positive effect of the stronger, faster, and more efficient protection of property rights on economic performance. In autocratic countries with a poor rule of law, ICCs are seen to increase trust in the protection of (foreign) property rights and to limit economic hold up problems in markets. In democratic countries with a strong rule of law, ICCs, in turn, are seen to accelerate and enhance the quality of commercial dispute resolution thereby reducing market inefficiencies. The reasoning reflects institutional economics and the so-called ‘legal origins’ school, which deem legal-judicial institutions to shape national economic performances (La Porta et al., Citation2008). It found its most prominent expression in the Washington Consensus, which aimed at strengthening markets and property rights notably through legal-judicial reforms.

While legal studies pointing to economic motives are convincing, they do not theorise the political economy dynamics leading to the creation of ICCs. ICCs have public good character in that their services are largely non-exclusive and non-rival. Collective action problems in the form of free riding should thus impede the creation of ICCs. It remains unclear from existing accounts which actors within society or the state push for ICCs, what their interests are, and thus how collective action problems are overcome. Further, legal scholarship does not offer thorough empirical analyses. From an IPE perspective, the creation of ICCs thus remains unexplained.

Theory – elite law firms as policy entrepreneurs in global economic dispute resolution

This study draws on the New Interdependence Approach (NIA) (Farrell & Newman, Citation2016) to elaborate on the ‘economic motives’ hypothesis and to advance an explanation for the rise of ICCs focused on law firms. The NIA models non-state actors—notably businesses—as transnational shapers of global economic governance. It stresses that states, societies, and economies have grown highly interdependent and have ceased to exist as fully discrete analytical units. It builds on three core assumptions to explain outcomes in international political economy (Farrell & Newman, Citation2016, pp. 721–726): First, the modern world economy does not exist in a state of anarchy devoid of rules but in a state of rule overlap. Internationalized non-state actors face manifold competing and conflicting norms in world markets, which may cause cost increases, challenge pre-existing domestic political settlements and drive lobbying efforts to adjust laws, regulations, and institutions to those of dominant economies or global approaches. Second, this rule overlap creates opportunities for non-state actors to build domestic and transnational coalitions to alter their institutional, legal, and regulatory context in line with their interests. Due to the high interdependence of economies and societies, non-state actors are likely to hold similar interests across countries facilitating and rewarding collaboration. Third, the combination of rule overlap and opportunity structures yields asymmetric effects on political power at the domestic and international level in that the frictions tied to rule overlap and related opportunities to build coalitions are not evenly distributed. If change actors are better placed to build coalitions, for instance, through better access to relevant domestic or international organizations, they are likely to forge new rules and institutions to their advantage. If status quo actors are better placed, in turn, they may impede reform agendas. The NIA, in sum, is a framework to explain domestic and transnational societal mobilization over legal, regulatory, and institutional change.

While the NIA has mostly been used to explain regulatory politics (Farrell & Newman, Citation2016), it helps theorizing institutional innovation in global commercial dispute resolution in the form of ICCs. Rule overlap is indeed at the heart of global commercial contracting and dispute resolution. Businesses involved in international trade, financial, or investment ventures are by definition based in different jurisdictions, which raises questions over the applicable law to interpret incomplete contracts and over the appropriate DSM. Contracts may be governed by the laws and DSMs of the home state of one of the parties, or by the laws and DSMs of a neutral third country—often England, New York, or Switzerland—to prevent that any one contracting party enjoys a legal-judicial home advantage (Cuniberti, Citation2014). To increase legal certainty in the face of this rule overlap, many international commercial contracts thus contain two types of provisions: (1) The actual commercial commitments such as the price, quantity, quality, financial, and delivery modalities; and (2) forum selection and choice of law provisions. The latter specify which law the parties chose to interpret their contract in case questions arise and which DSM they agree to use in case of a dispute (Cuniberti, Citation2014). These provisions are in essence an attempt at private ordering in world markets with the objective to increase legal certainty and enforceability of contracts in a world of rule overlap (Basedow, Citation2015). They cannot, however, fully do away with the challenges inherent to rule overlap in commercial law and world markets. For one, contracts may inadvertently contain obligations that are incompatible with the chosen national law. Or in case of a dispute, the jointly agreed DSM may question the choice of law or forum selection clauses. Lastly, the contracting parties themselves may renege on choice of law and forum selection clauses once a dispute arises to gain a legal-judicial advantage. In all three instances, the pandora’s box of rule overlap and legal uncertainty fully re-opens.

Many firms involved in international trade, financial, and investment ventures do not have the legal expertise to navigate this commercial law maze of world markets. They turn to law firms specialized in international commercial law and litigation—often so-called ‘White Shoe’ or ‘Magic Circle’ global elite law firms—to advise them on how to manage rule overlap at the (1) contract drafting, (2) dispute resolution, and (3) contract enforcement stage. The business model of these law firms is to assist other firms in managing rule overlap. They are often highly internationalized with subsidiaries around the world and can leverage their network and local legal-political expertise and contacts to advise their clients and pursue their own interests. As international trade, capital, and investment volumes have surged since the 1990s, demand for legal expertise in international contracting and commercial dispute resolution has grown and gained salience among academics, business leaders, and policymakers (Basedow, Citation2015). In accordance with the NIA, this study theorizes that specialized law firms should perceive this growing salience of rule overlap in commercial law and dispute resolution as an opportunity to build a global legal-institutional environment that is conducive to growing their business operations. IPE research has shown how the arbitration community has worked towards the consolidation of the arbitration regime complex throughout the twentieth century (Bonnitcha et al., Citation2017; Hale, Citation2015; Mattli, Citation2001). This study stipulates that ICCs are the result of similar efforts predominantly driven by law firms specialized in commercial litigation. ICCs are often described as an institutional innovation to increase the competitiveness of national economies, to generate FDI and capital inflows and tax revenue (public good) yet from the perspective of specialized law firms they are also a means to grow the market for international commercial litigation services (private good). ICCs supposedly offer high quality, procedurally flexible, discrete, and multilingual dispute resolution services comparable to arbitration yet at lower costs for disputing parties (Bell, Citation2018; Brekoulakis & Dimitropoulos, Citation2022). They tend to charge a fraction of the fees of arbitrators. Hence, ICCs are expected to increase commercial litigation volumes as they reduce dispute aversion among businesses rooted in (1) concerns over the lacking commercial expertise of ordinary courts and (2) the considerable costs of commercial arbitration (Stipanowich, Citation2014, p. 302). The concentrated benefits that specialized law firms expect to reap from ICCs should thus address the latent collective action problems in ICC creations.

Depending on the national legal and political context, law firms should collaborate and forge domestic and transnational coalitions to advance ICC projects. In states with a highly developed rule of law, typically advanced democracies, law firms should predominantly partner with judges and court administrations. As judiciaries in these countries are highly independent and have considerable influence on the framework legislation governing national court systems, judges and judicial administrations are key partners for the advancement of ICC projects. Forging coalitions with national judiciaries should, furthermore, be easier in Common Law countries than in Civil Law countries as professional ties between law firms and the judiciary are stronger. In Common Law countries, judges must work for many years in private practice before becoming appointable to the bench. The most gifted lawyers in private practice—often working for elite law firms—then become senior judges on high courts involved in important commercial disputes and the management of court systems. Senior judges in Common Law countries are thus seen to be receptive to the needs and interests of their former colleagues in private practice. Many, furthermore, return to private practice after their retirement from the bench as senior counsels in elite law firms or arbitrators due to their long-standing personal ties to private practice. In Civil Law countries, in contrast, the career tracks of lawyers in private practice and judges are less intertwined. The judiciary typically recruits judges among recent law graduates or junior scholars with limited private practice experience. In consequence, judges in Civil Law countries are seen as less attuned to the interests and less likely to join private practice after retirement.

These differences in the political economy of the judiciaries in Common and Civil Law countries should have implications for (1) the sequencing and (2) motivation/narrative behind ICC projects. First, Common Law judges are likely to perceive ICC projects as a business opportunity to increase litigation volumes for law firms and—after retirement from the bench—for themselves as counsels or indeed ICC judges. They should thus welcome ICC projects, partner with law firms and jointly become first movers in the creation of ICCs. Second, Civil Law judges should be comparatively hesitant to partner with law firms on ICC projects. Rising competition with foreign ICCs and the potential outflow of litigation, however, may motivate judges and court administrations to support ICC projects to preserve court fees and judicial authority. Law firms may amplify these concerns among judges by pushing ICC projects onto the political agenda in competing jurisdictions. Civil Law systems, in other words, are likely to be second movers reacting to foreign competitive pressure. The reasoning, further, implies that ICC projects are most likely to occur in countries with high international economic exposure in that only these countries host a critical mass of specialized law firms and commercial expertise in the judiciary that is necessary for political coalitions in support of ICC projects to emerge. Lastly, it is important to identify potential opponents of ICC projects. The NIA stipulates that institutional, legal, and regulatory reforms have distributive effects and may give rise to transnational coalitions to preserve the status quo. The highly technocratic nature of ICCs is unlikely to make them subject of public debates. Yet, opposition to ICC projects may emerge from three sides. Globalization critical groups on the left may see ICC projects as catering to the interests of ‘big business’ and creating a neoliberal two-tier judicial system. Conservative groups on the right, in turn, may oppose ICCs as globalist institutions that challenge state identity, laws, and sovereignty. Last, arbitrators may see ICC projects as competitors. As coalitions of law firms and judges tend to be politically well connected and resourced, however, they are likely to outmanoeuvre opposition.

In countries with a weak rule of law, in turn, the political coalitions pushing for ICCs should differ in three regards. First, law firms should forge coalitions with the political leadership rather than national judiciaries to advance ICC projects. Judiciaries are weak in countries with a weak rule of law and lack the political clout to push typically autocratic governments into the creation of ICCs that supposedly benefit from higher levels of judicial independence than ordinary courts. In autocracies, ICCs—especially as part of the legal infrastructure of SEZs and subject to a constitutional carve-out—are indeed attempts at autocratic self-restraint. Second, the law firms driving ICC projects should be foreign rather than domestic due to the limited importance of the legal sector and judiciary in autocracies. Societies with a weak rule of law, to put it bluntly, rarely breed successful law firms. Third, foreign law firms and political leaders are likely to advance ICC projects as part of broader economic development and diversification agendas. Whereas ICC projects in developed democracies should be embedded in narratives about service sector promotion and judicial modernization, ICC projects in developing autocracies should form part of national economic reform programs emphasizing the importance of private property rights for growth. Lastly, opposition to ICC projects is unlikely to surface due to political repression.

In sum, this study advances the following hypothesis: Specialized law firms drive ICC projects to grow the market for global commercial litigation. This hypothesis—and the competing hypotheses identified in the literature survey—give rise to several testable expectations and counter-expectations.

Research design

As of 2023, states have created 13 ICCs. These ICCs constitute the universe of cases that this study seeks to analyze and explain. Due to the heterogeneity of relevant states, intermediate number of cases and nature of here-developed theory, quantitative methods are unlikely to yield robust and statistically significant results. Hence, this study draws on a combination of qualitative methods to test/refute the hypothesis and expectations (). The primary method that this study employs is analytical process tracing (Bennett, Citation2009). It assumes a middle ground between idiographic and nomothetic reasoning and aims to generate explanations of high internal and—to a lesser degree—external validity. This approach stipulates that theory-driven hypotheses should be broken down into testable expectations about policymaking actors and dynamics, and outcomes. To lower the risk of confirmation bias, studies drawing on analytical process tracing should furthermore test several explanations. These hypotheses do not have to be mutually exclusive yet should point to substantially different causalities. Overall, the approach endorses a Bayesian logic in that theory development and testing proceed in parallel, and the objective is to generate probabilistic findings on the basis of continuously evolving data.

Table 2. Overview of hypothesis, expectations and counter-expectations.

To test the hypotheses, expectations and counter-expectations, the study draws on different data sources. First, it uses primary sources relating to ICC design, operations, case load and CVs of key protagonists. All ICCs have websites that contain relevant data. Second, the study draws on 28 semi-structured expert interviews conducted between August 2022 and January 2024 with ICC judges, clerks, lawyers, arbitrators, national and international bureaucrats involved with ICC projects, and legal academics. To identify suitable interviewees, a snowballing approach was used with experts of one ICC suggesting experts for another ICC. The interviewing process provided for first-hand insights on all ICCs from different professional angles. Third, it builds on legal secondary literature. As discussed above, lawyers have produced a sizeable number of studies that are at times rich in empirical detail. Lastly, the study draws on media coverage of ICCs. The technical nature of commercial dispute resolution in general and ICCs in particular implies, however, that media reporting is limited.

Analysis

The analysis section traces the rise of ICCs in the world economy over time. It then assesses the evidence supporting or invaliding the expectations and counter-expectations.

Chronology of ICC creations

The first ICC to emerge was the London Commercial Court (LCC) founded in 1895 (Gu & Tam, Citation2022). The LCC was created as a court for domestic commercial disputes though developed over time into a court specialised in international commercial disputes (Cranston, Citation2021). This transformation reflected, on the one hand, London’s role as the centre of the British empire and world economy and, on the other hand, long-lasting efforts of the LCC bench and barristers to strengthen the court’s expertise and reputation in commercial matters and its permissive stance on hearing foreign cases with minimal legal ties to England (ibid.). The LCC indeed started adjudicating international disputes—often without British party involvement—in the 1920s, and since the late twentieth century such disputes account for almost 80% of its case load (Judiciary, Citation2023). The LCC came to be seen as a key factor in the continued attractiveness of London as a global financial and commercial hub. To maintain the LCC’s global leadership, it continuously deliberates with law and financial firms and the British Department of Justice on reforms (interview, 29 August 2022). This symbiotic relationship between the LCC bench, law firms and other stakeholders has shaped and placed the LCC at the centre of the global commercial dispute resolution landscape. Most other countries look to the LCC, its setup and English law to gain inspiration for legal-judicial reforms in commercial affairs.

The first imitator of the LCC emerged in New York. In the 1980s, discussions started among leading New York law firms and the state’s judiciary about an outflow of financial and commercial litigation from New York to US federal courts, the LCC, and Delaware rooted in the slowness of New York courts (Miller & Eisenberg, Citation2009; NYCD, Citation2006). The New York bar association and judiciary created a task force of senior judges and leading law firms to identify reforms to re-establish the attractiveness of New York’s legal and judicial order, which led to the creation of the Commercial Division of the Supreme Court of New York in 1995. The NYCD only hears large financial and commercial—often international—disputes, works fast, holds considerable expertise, and helped to consolidate New York’s role as the preeminent global commercial dispute resolution hub next to London. In 2012, the Chief Judge of New York Jonathan Lippman established another task force to review the performance of the NYCD and stated ‘…the aim was and remains to ensure that New York’s system […] is efficient, sophisticated and sound, in keeping with New York’s role as not merely the national but the world capital of commerce, finance, media and other great businesses, enterprises and activities’ (New York Courts, Citation2012, p. 1). The composition of the task force illustrates the ties between elite law firms and the judiciary in Common Law systems. It was co-chaired by Judith Kaye, a retired Chief Judge of New York and then counsel of the global law firm Skadden Arps, and Martin Lipton, a founding partner of a leading law firm Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz specialized in financial markets law (ibid). The other members of the task force were drawn from international law firms, judges, major clients, and state technocrats. Chief Judge Jonathan Lippman, lastly, retired in 2015 and joined the white shoe law firm Latham & Watkins as counsel for commercial litigation. A quasi-symbiotic cooperation between law firms and the New York judiciary thus led to creation of the NYCD and has since been shaping this ICC.

Thinking on ICCs—as courts exclusively dedicated to international disputes—started in the late 1990s due to the success of the LCC and the NYCD as well as a broader legal-judicial reform movement. The economic paradigm of the time emphasized the importance of legal-judicial systems in protecting property rights, enabling markets, attracting capital and investment, and thus promoting economic growth and development (Faundez, Citation2010). The work of the World Bank illustrates this zeitgeist. In the 1990s, the Bank started designing legal-judicial reform programs for developing countries and—due to a lack of in-house expertise—hired leading law firms in London, New York, and Washington to help (Faundez, Citation2010, p. 184). In 2003, this work resulted in the publication of a World Bank monograph entitled ‘Legal and Judicial Reform—Strategic Directions’ and the Bank’s first edition of the Doing Business report, which benchmarked national judiciaries in view of their efficiency and effectiveness in resolving commercial disputes. While the World Bank has not formally advocated the creation of ICCs, it has developed policy recommendations on how to design commercial courts and DSMs in support of economic development.

It was against this background that the autocratic leadership of Dubai appointed in 1998 the London offices of the elite law firms Clifford Chance and Allen & Overy to advise on the regulatory, legal, and judicial infrastructure needed to modernize and diversify its economy and in particular to set up a SEZ for financial services (Krishnan, Citation2018, p. 10). While Dubai did not formally take part in World Bank programs, Clifford Chance and Allen & Overy were likely part of the group of law firms assisting the World Bank in its efforts to develop legal-judicial systems. This consulting work took place between 1998 and 2003 and was part of the government’s national development plan (Hvidt, Citation2009). In comparison to other Gulf countries, Dubai is resource-scarce, which has driven the Emir to pursue development through human capital and the service sector largely copying Singapore’s developmental strategy (ibid.). In 2004, the work of Clifford Chance and Allen & Overy culminated in a law creating the Dubai International Financial Centre (DIFC) with its own legal order based on English Common Law, tax regime, financial regulator, and commercial court (DIFCC). The DIFCC started operating in 2006 with the judicial appointments—likely again upon recommendation of Clifford Chance and Allen & Overy—of the senior British judge Anthony Evans and the British-trained Singaporean lawyer Michael Hwang (Krishnan, Citation2018). Evans’ appointment as DIFCC chief judge is particularly noteworthy. Before starting at the DIFCC, Evans had chaired the LCC in the 1990s and after his retirement returned to private practice as counsel and arbitrator. When Evans stepped down from the DIFCC after a long decade, he reportedly recommended his former LCC colleague Peter Gross to take over, highlighting the role of transnational judicial networks (interview, 14 November 2023). The DIFCC case underscores the importance of law firms in conceiving ICCs and the close professional relations and overlapping interests between judges and law firms.

The success of the DIFC and DIFCC spurred interest in international financial centres and ICCs in the wider region. In the following years, the autocratic governments of Qatar (2010), Abu Dhabi (2015), and Kazakhstan (2017) started working with law firms and legal advisors—and in the case of Kazakhstan also with the World Bank and Organization for Economic Development and Co-operation (OECD)—on similar economic reform programs and the creation of international financial centres with ICCs in pursuit of economic development, diversification, capital and FDI inflows (interviews, 20 January 2023, 19 September 2022, 5 September 2022; OECD, Citation2023; World Bank, Citation2023). The ICCs that consequently emerged resemble the DIFCC in most regards. They exist within SEZs with preferential tax regimes, benefit from constitutional carve-outs, adjudicate international commercial and financial disputes, operate based on their own laws modelled after English Common Law and often are institutionally linked to arbitration and mediation bodies. To signal judicial independence, all courts, furthermore, appointed mostly retired judges from Common Law jurisdictions—often British lawyers and former LCC members—to their bench and allow foreign lawyers to plead. The opaque political situation in most of these countries makes it difficult to discern whether law firms or autocrats initiated these ICC projects, yet the success of the DIFCC clearly inspired these efforts.

In the early 2000s, discussions on ICCs also started in Germany, the Netherlands, and Singapore. They gained momentum around 2010 with Germany first to act. In 2005, several regional German courts launched pilot projects that allowed for hearings in English and had the objective to attract international litigation. These pilots reportedly reflected lobbying by regional bars as well as personal interests of court presidents (interview, 14 November 2023). While a first symbolic step, the pilots were of limited success (ibid.). Yet, in 2009, the national bar and notary associations rekindled discussions on ICCs and an internationalization of the German legal and court system with their marketing publication ‘Law Made in Germany’ (DAV, Citation2023). The report was a response to a publication of the English bar entitled ‘England and Wales: Jurisdiction of Choice’ that sought to attract notably European litigants to the LCC (Kötz, Citation2010). The German report highlighted the quality of German legal services as well as expertise, effectiveness, and efficiency of German courts. It was published in multiple languages and meant to attract foreign litigants and to get the attention of policymakers for legal-judicial reforms needed to boost Germany’s legal competitiveness. The initiative at first seemed effective. In 2010, the regional governments of North Rhine-Westphalia, Hamburg, and Hesse introduced—in close cooperation with their regional bars and judiciaries—a legislative proposal in the upper house of Germany’s parliament that was meant to reform Germany’s judicial constitution to allow for a full-blown ICC adjudicating in English (Wagner, Citation2017). The lower house, however, failed to vote on the proposal during the parliamentary term, which led to its discontinuation. The upper house re-introduced the proposal in the next two parliamentary terms yet with the same result. Interviewees suggested that the repeated failure of the proposal reflected scepticism and limited interest in the lower house and federal government (interview, 14 November 2023). While conservative parliamentarians and academics disliked the idea of German courts adjudicating in foreign languages, the federal government showed little interest due to the limited role of the federal state in Germany’s judiciary. In response to this stalemate, the regional bars, courts, and governments of Hamburg, Hesse and Baden-Württemberg pressed on and created—within their constitutional powers—ICCs in Frankfurt (2018), Hamburg (2018), and Stuttgart/Mannheim (2020). The failure to modernize Germany’s judicial constitution to empower courts to rule in English and the creation of multiple competing ICCs is seen as partly self-defeating (interview, 14 November 2023). Proponents, however, see these ICCs as first steps in broader reforms of the German legal-judicial landscape.

Similar dynamics played out in Singapore. The city-state seeks to establish itself as a global commercial, financial, and service hub. To that end, the government has been investing for decades in human capital, physical and institutional infrastructure needed to attract global financial and commercial activities. The legal sector and judiciary play a crucial role in these programs. In 2006, the president of the supreme court after informal discussions with the state bureaucracy and private sector convened a committee ‘to undertake a comprehensive review of the entire legal services sector, particularly in relation to exportable legal services, to ensure that Singapore remains at the cutting edge as an international provider of legal services both in the short-term as well as in the long-run’ (Ministry of Law, Citation2007, p. 1). Like in New York, the committee brought together representatives of major national and international law firms and businesses, senior judges, and arbitrators, as well as government technocrats. Notably, the committee encompassed partners of the elite law firms Clifford Chance and Allen & Overy, which already played a crucial role in the creation of the DIFCC in Dubai, and Michael Hwang, a leading Singaporean barrister, judge of the DIFCC, and confidant of Singapore’s long-term Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon. The committee reviewed Singapore’s legal education tax regime for legal professionals and law firms, professional accreditation, and market access requirements, and its arbitration and mediation laws and institutions in view of attracting legal talent and international commercial disputes. When the committee published its findings in 2007, it gave manifold recommendations on the internationalization of the Singaporean legal sector, court system, and strengthening of its arbitration and mediation institutions. Creating an ICC to complement the reform agenda, however, was first mentioned in a speech by Chief Justice Menon in 2013 (Yip, Citation2019). Menon suggested that a visit to the LCC had made him realize that commercial arbitration and ICCs were not competitors but mutually supportive services. Yet, Menon’s personal ties to DIFCC judge Hwang—who published a paper on the complementarity of arbitration and ICCs around the same time (Hwang, Citation2015)—are likely to have amplified this interest in ICCs. Menon created a follow-up committee to flesh out the idea of a Singaporean ICC (SICC) that brought together Singaporean judges, policymakers, and partners of leading local and international law firms. In January 2015, the SICC was finally created and within weeks Menon and Hwang met in Dubai to sign a memorandum of understanding on cooperation between the SICC and DIFCC (GAR News, Citation2015). Law firms were thus intimately involved in the Singaporean case, yet observations also point to a highly proactive role of the judiciary and transnational judicial networks in the creation of the SICC.

In the Netherlands, an academic advisory body of the government first floated the idea to create a Dutch ICC in 2003, yet without kindling much interest. Serious discussions started in 2014, when the president of the Dutch Council of the Judiciary proposed the creation of a Dutch ICC in a speech (Kramer & Antonopoulou, Citation2023). The Council of the Judiciary represents Dutch courts in the political realm. It is composed of two retired senior judges and two non-judge members often with a background in private practice, business, or government. It is mandated to review the performance and budget of the Dutch judiciary and to advise on reforms. To that end, it engages in continuous discussions and regularly surveys stakeholders such as law firms, courts, and businesses. It is therefore difficult to establish who inspired the president to propose a Dutch ICC. It seems most likely that the idea had simply become part of peer discussions in view of developments in other jurisdictions at that time. Following the president’s speech, the Council started preparing a cost-benefit assessment for an ICC. It widely consulted with law firms, courts, businesses, and trade unions and tasked the Boston Consulting Group to draft a background brief on ICCs. These consultations highlighted the societal demand to improve access to affordable, expert adjudication in English in that most Dutch businesses operate and contract in English, making court proceedings in Dutch costly. Courts and law firms, furthermore, reportedly welcomed the ICC proposal as an opportunity to trial new technologies, docket management systems and to strengthen the Netherland’s position as a legal service provider (interview, 17 October 2023). In 2015, the Council published its cost-benefit assessment in a report advising the government to prepare legislation for the creation of an ICC (Rechtspraak, Citation2015). The Dutch parliament adopted the law in 2018 without noteworthy opposition, and the Netherlands Commercial Court (NCC) started operating within weeks.

The creation of the Paris ICC, in turn, is unambiguously the result of lobbying by the Paris bar. In 2016, Parisian law firms—like their peers in financial services—started reflecting on the ramifications of Brexit for the Paris bar and approached the ministry of justice to start collaborating on strengthening Paris courts in view of attracting litigants from the LCC (interview, 31 October 2023). The ministry was sympathetic and tasked the Haute Comité Juridique pour la Place Financière de Paris (HCJP) to study the implications of Brexit (Biard, Citation2019). This committee—working under the auspices of the Banque de France and advising on legal-judicial reforms to strengthen Paris as a financial hub—brings together representatives of leading law firms including partners of Clifford Chance, Allen & Overy, Clearly Gottlieb, major financial firms, judges, academics, and technocrats. In January 2017, the committee published a first study on the legal-judicial consequences of Brexit. In May 2017, it released a follow-up policy paper with the recommendation to establish an ICC to capture market share from London in financial and legal services. It advised to emulate the workings of the LCC and discussed resource implications for the judiciary (Biard, Citation2019; interview, 31 October 2023). This policy paper led to the signing of a protocol between the Paris bar and Paris Court of Appeals, under the supervision of the ministry of justice, on the creation of the Paris ICC in February 2018. The Paris ICC, it is important to note, was not created from scratch. Specialized commercial courts have been part of the French judicial system since Napoleonic times. The protocol merely restructured relevant Parisian institutions in view of approximating them to Common Law courts and labelling them as ICCs to increase visibility (interview, 31 October 2023).

Lastly, the Chinese ICC (CICC) was created in 2018. The CICC constitutes an outlier in that law firms and bar associations reportedly played no role in its establishment (Huo & Yip, Citation2019; interviews, 19 September 2022, 5 September 2022, 1 December 2023; Liu, Citation2022; Qian, Citation2020). Sources instead suggest that China’s political leadership was the key driver behind the CICC. In 2013, President Xi Jinping formally launched the BRI, which is meant to increase China’s influence in international affairs through large-scale international infrastructure projects and financing schemes. According to the CICC (Liu, Citation2022), the BRI led to a multiplication of international commercial disputes between Chinese and foreign firms tried in Chinese courts. In January 2018, the Communist Party’s Central Leading Group on Overall Reform, chaired by President Xi Jinping, thus discussed the idea to create an ICC to complement the BRI and tasked China’s highest court—the Supreme People’s Court (SPC)—to develop and implement the project. The SPC’s adjudication committee consequently drew up plans to create the CICC as a specialized chamber of the SPC. The SPC leadership adopted these plans in June 2018 and the CICC was formally inaugurated in the following days. Since then, the SPC set up an International Commercial Expert Committee of foreign lawyers that is meant to advise CICC judges and to signal the CICC’s neutrality. It further institutionalized cooperation with Chinese mediation and arbitration institutions to provide for one-stop dispute resolution. While official sources depict the CICC as a functional response to the growing prevalence of international commercial disputes in Chinese courts, most observers see the CICC also as a geopolitical tool. The CICC and SPC are indeed politically controlled courts in that the Communist Party can formally direct them in their jurisprudence (Heilmann, Citation2016).

Evaluating the empirical validity of expectations and counter-expectations

Initiation

Having discussed the chronology, the analysis turns to evaluating the validity of the expectations and counter-expectations. To recall, E1 states that law firms—rather than governments—are the architects of ICCs. Except for the CICC, law firms indeed played a central role in all ICC creations. Evidence regarding the initiation of ICC projects by law firms is particularly clear in the cases of New York, Dubai, Germany, and France. In other cases, such as the Netherlands or Singapore, law firms were central actors in the policymaking leading to ICC creations, yet it is less clear whether they were the initiators. Ultimately, though, this study shows that in most countries, courts and bars maintain close relations and engage in continuous discussions blurring the difference between bench and bar as discrete political agents. A remarkable finding against this background is indeed the proactivity of judiciaries and individual judges in several cases. Judges and courts played a more active role in advancing ICC projects—both in Common and Civil Law countries—than theorized.

Coalition building

Expectation 2 states that law firms should form coalitions with judiciaries in countries with a strong rule of law and with political leaders in the autocratic countries with a weak rule of law. Again, except for the CICC, evidence supports the expectation. In countries with a strong rule of law, ICCs emerged when law firms and judiciaries jointly supported such projects. Governments, in turn, were mostly reactive in their support. In autocratic countries with a weak rule of law, global law firms collaborated with leaders and pushed ICCs onto broader development agendas. National judiciaries did not play a central role. While difficult to substantiate, it seems likely that the development policy prescriptions of the World Bank and OECD of the 1990s and 2000s—focused on legal-judicial reforms to strengthen markets—paved the way for law firms in these countries. In terms of coalition building, it is further remarkable how judges seem to have engaged in transnational inter-judicial coalition-building. The analysis highlighted how personal ties between the LCC, DIFCC, and SICC shape these institutions and appointments, emphasizing the overlooked political agency of judges in global economic governance.

Sequencing

Expectation 3, lastly, stipulates that countries with Common Law systems should develop ICCs earlier than countries with Civil Law systems due to the political economy of the legal sector and material interest of judges. The analysis () supports this expectation in that the LCC and NYCD led the way with countries with Civil Law systems reacting to competitive pressures. Overall, the findings thus largely confirm the main hypothesis.

Conclusion and outlook

In the last decades, ICCs started emerging around the world. What forces fuel the rise of ICCs? In line with the NIA (Farrell & Newman, Citation2016), this article argues that rule overlap is at the very heart of trade and investment transactions in world markets. Specialized law firms identified this rule overlap as an opportunity to reshape the global institutional context and regime for commercial dispute resolution through the creation of the ICCs in view of growing the market for their commercial litigation services. As these law firms tend to be highly internationalized and politically well-connected to senior judges, technocrats, and politicians, they were well-positioned to build the political momentum necessary to set up ICCs and outmanoeuvre critical voices. Going forward, further research is needed to shed additional light on the role of other non-state actors such as multinational corporations and their in-house counsels in shaping the global regime complex for commercial dispute resolution and ICCs.

Furthermore, two observations deviate from our expectations and need discussion. First, the creation of the CICC occurred without noteworthy involvement of law firms. Instead, the Chinese leadership drove the creation of the CICC as part of its BRI. Unlike most other ICCs, the CICC indeed seems to have a geopolitical dimension. Second, in several cases, the judiciary played a more proactive role in ICC creations than theorized. In the Netherlands and Singapore, the impetus for ICC creations came from the judiciary. It remains unclear though whether prior informal lobbying from law firms may have occurred and driven these initiatives. The tightly-knit relations between bench and bar in many jurisdictions indeed make it difficult to distinguish between these two actor categories. What is more, the study found several instances of transnational judicial collaborations. For one, the LCC and DIFCC seem to be linked through strong personal ties of judges. The same applies to the DIFCC and the SICC. In 2017, the LCC, moreover, initiated the creation of the Standing International Forum of Commercial Courts (SIFoCC) in London, which brings together ICCs and jurisdictions considering the creation of such courts to promote peer discussions. Taking into consideration that many ICCs hire retired LCC judges, SIFoCC may also be seen as a promotional tool to increase demand for LCC judges and boost its centrality in global judicial networks. Judiciaries and law firms have so far received little attention in IPE scholarship (Kahraman et al., Citation2020; Kalyanpur, Citation2023). The findings of this study, however, caution that these actors deserve greater consideration.

What are the broader theoretical implications of this study? To start, the study underpins the core claims of the NIA about the dynamics shaping modern international political economy (Farrell & Newman, Citation2016). Rule overlap and opportunity structures indeed feature prominently in the rise of ICCs. These observations suggest that state-centric theories of international relations—notably neo-realism and neo-liberalism—may be ill-equipped to fully capture policymaking and institutional change in a globalized world economy. In the domain under scrutiny here, societal agents and lobbying efforts often transcended national borders and took advantage of their global interconnectedness.

What is more, in the early 2000s, experts expected private transnational economic governance and dispute resolution—in the form of arbitration—to gradually displace public governance and litigation in courts (Cutler, Citation2003; Mattli, Citation2001). Private ordering of markets was seen as more efficient and effective and set to crowd out public ordering and courts. Arbitration and mediation have indeed been prospering over the last decades, yet its effect might not be a crowding out and replacement of public governance but transformation of judiciaries. Courts, in the form of ICCs, have started copying features of arbitration and mediation and operate according to a market logic. They seek to compete and co-opt private fora through the offering of one-stop dispute resolution hubs combining litigation, arbitration, and mediation under one roof. Globalization and neoliberalism appear not to replace state institutions but rather to alter their functional logic from one of public service to service providers. ICCs may thus be seen as manifestations of a neoliberalization of judiciaries and thus—in line with the NIA—as a subtle asymmetric power shift from state to private sector interests. The study thereby adds to the literature highlighting the redistributive and power effects of law in the global political economy (Cutler & Lark, Citation2022; Dietz & Cutler, Citation2017; Pistor, Citation2019). The limited case load of ICCs may at first sight suggest that this neoliberalization of judiciaries is a marginal phenomenon. Yet, as several ICC judges and clerks noted (interviews, 10 October 2022, 17 October 2023), ICCs constitute experiments, which are meant to inform upcoming reforms of the broader judiciary in various countries (Yip & Rühl, Citation2024). ICCs may only be the tip of the iceberg.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank three anonymous reviewers, the editors, Moritz Schmoll and Jürgen Basedow for their helpful comments and suggestions to improve the manuscript. I would like to further thank Sophie Meunier and the Liechtenstein Institute on Self-Determination for hosting me during my sabbatical.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Robert Basedow

Robert Basedow is an Associate professor for International Political Economy at the London School of Economics and Political Science.

References

- Alcolea, L. C. (2022). The rise of the international commercial court: A threat to the rule of law? Journal of International Dispute Settlement, 13(3), 413–442. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnlids/idac022

- Allee, T., & Elsig, M. (2016). Why do some international institutions contain strong dispute settlement provisions? New evidence from preferential trade agreements. The Review of International Organizations, 11(1), 89–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-015-9223-y

- Basedow, J. (2015). The law of open societies: Private ordering and public regulation in the conflict of laws. In J. Basedow (Ed.), The law of open societies: Private ordering and public regulation in the conflict of laws. Brill Nijhoff.

- Basedow, J. R. (2021). Why de-judicialize? Explaining state preferences on judicialization in World Trade Organization dispute settlement body and investor-to-state dispute settlement reforms. Regulation & Governance, 16(4), 1362–1381. https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12431

- Bell, G. F. (2018). The new International Commercial Courts—competing with arbitration? The example of the Singapore International Commercial Court. Contemporary Asia Arbitration Journal, 11(2), 193–216.

- Bennett, A. (2009). Process tracing: A Bayesian perspective. In J. Box-Steffensmeier, H. Brady, & D. Collier (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of political methodology (pp. 702–721). Oxford University Press.

- Biard, A. (2019). International Commercial Courts in France: Innovation without revolution? Erasmus Law Review, 12(1), 24–32. https://doi.org/10.5553/ELR.000111

- Bonnitcha, J., Poulsen, L., & Waibel, M. (2017). The political economy of the investment treaty regime. Oxford University Press.

- Bookman, P. (2020). The adjudication business. Yale Journal of International Law, 45, 227.

- Brekoulakis, S., & Dimitropoulos, G. (Eds.) (2022). International Commercial Courts: The future of transnational adjudication, studies on international courts and tribunals. Cambridge University Press.

- Chaisse, J., & Qian, X. (2021). Conservative innovation: The ambiguities of the China International Commercial Court. American Journal of International Law, 115, 17–21. https://doi.org/10.1017/aju.2020.81

- Cranston, R. (2021). Making commercial law through practice 1830–1970. Cambridge University Press.

- Crasnic, L., Kalyanpur, N., & Newman, A. (2017). Networked liabilities: Transnational authority in a world of transnational business. European Journal of International Relations, 23(4), 906–929. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066116679245]

- Cuniberti, G. (2014). The international market for contracts – the most attractive contract laws. Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business, 34, 455–517.

- Cutler, A. C. (2023). Blind spots in IPE: Contract law and the structural embedding of transnational capitalism. Review of International Political Economy, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2023.2250349

- Cutler, A. C. (2003). Private power and global authority: Transnational merchant law in the global political economy. Cambridge University Press.

- Cutler, A. C., & Lark, D. (2022). The hidden costs of law in the governance of global supply chains: The turn to arbitration. Review of International Political Economy, 29(3), 719–748. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2020.1821748

- DAV. (2023). Law made in Germany. https://lawmadeingermany.de/ (accessed December 6, 2023).

- Dietz, T., & Cutler, C. (Eds.) (2017). The politics of private transnational governance by contract. Routledge.

- Dimitropoulos, G. (2021). International commercial courts in the ‘modern law of nature’: Adjudicatory unilateralism in special economic zones. Journal of International Economic Law, 24(2), 361–379. https://doi.org/10.1093/jiel/jgab017

- Efrat, A. (2016). Promoting trade through private law: Explaining international legal harmonization. Review of International Organizations, 11, 311–336.

- Erie, M. S. (2019). The new legal hubs: The emergent landscape of international commercial dispute resolution. Virginia Journal of International Law, 60, 225–298.

- Farrell, H., & Newman, A. (2016). The new interdependence approach: Theoretical development and empirical demonstration. Review of International Political Economy, 23(5), 713–736. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2016.1247009

- Faundez, J. (2010). Rule of law or Washington consensus: The evolution of the World Bank’s approach to legal and judicial reform. In A. Perry-Kesaris (Ed.), Law in pursuit of development: Principles into practice? Routledge.

- GAR News. (2015). Why international courts may be the way forward? https://www.clydeco.com/clyde/media/fileslibrary/16-2-15__Why_international_courts_may_be_the_way_forward.pdf.

- Gu, W., & Tam, J. (2022). The global rise of international commercial courts: Typology and power dynamics. Chicago Journal of International Law, 22(2), 443–492.

- Hale, T. (2015). Between interests and law: The politics of transnational commercial disputes. Cambridge University Press.

- Heilmann, S. (Ed.). (2016). China’s political system. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Höland, A., & Meller-Hannich, C. (2016). Nichts zu klagen? Der Rückgang der Klageeingang Zahlen in der Justiz: Mögliche Ursachen und Folgen, 1st edition [Nothing to complain about? The decline in the number of lawsuits received in the judiciary: Possible causes and consequences]. Nomos, Baden-Baden.

- Huo, Z., & Yip, M. (2019). Comparing the International Commercial Courts of China with the Singapore International Commercial Court. International and Comparative Law Quarterly, 68(04), 903–942. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020589319000319

- Hvidt, M. (2009). The Dubai model: An outline of key development-process elements in Dubai. International Journal of Middle East Studies, 41(3), 397–418. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020743809091120

- Hwang, M. (2015). Commercial courts and international arbitration—Competitors or partners? Arbitration International, 31(2), 193–212. https://doi.org/10.1093/arbint/aiv038

- Judiciary. (2023). Commercial court report 2022–23. https://www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/14.448_JO_Commercial_Court_Report_2223_WEB.pdf (accessed 22.5.2024).

- Kahraman, F., Kalyanpur, N., & Newman, A. L. (2020). Domestic courts, transnational law, and international order. European Journal of International Relations, 26(1_suppl), 184–208. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066120938843

- Kalyanpur, N. (2023). An illiberal economic order: Commitment mechanisms become tools of authoritarian coercion. Review of International Political Economy, 30(4), 1238–1254. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2023.2211280

- Kötz, H. (2010). The jurisdiction of choice: England and Wales or Germany? European Review of Private Law, 18(Issue 6), 1243–1257. https://doi.org/10.54648/ERPL2010085

- Kramer, X., & Antonopoulou, G. (202s3). Commercialising litigation: The case of the Netherlands Commercial Court. Oxford Law Blogs [WWW Document]. International Commercial Courts: A paradigm for the future of adjudication? https://blogs.law.ox.ac.uk/oblb/blog-post/2023/05/commercialising-litigation-case-netherlands-commercial-court (accessed January 22, 2024).

- Krishnan, J. (2018). The story of the Dubai international financial centre courts: A retrospective. Books & Book Chapters by Maurer Faculty. 199. https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1199&context=facbooks#:∼:text=The%20book%20explores%20the%20evolution,enforced%20on%20a%20global%20scale (accessed 22.5.2024).

- La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. (2008). The economic consequences of legal origins. Journal of Economic Literature, 46(2), 285–332. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.46.2.285

- Liu, T. (2022). 国际商事法庭 | CICC – The China International Commercial Court (CICC) in 2018 [WWW Document]. CICC. https://cicc.court.gov.cn/html/1/219/208/209/1316.html (accessed December 18, 2023).

- Mattli, W. (2001). Private justice in a global economy: From litigation to arbitration. International Organization, 55(4), 919–947. https://doi.org/10.1162/002081801317193646

- Mattli, W., & Dietz, T. (2014). (Eds.) International arbitration and global governance: contending theories and evidence. Oxford University Press.

- Meller-Hannich, C., Höland, A., & Nöhre, M. (2023). Abschlussbericht zum Forschungsvorhaben, Erforschung der Ursachen des Rückgangs der Eingangszahlen bei den Zivilgerichten [Final report on the research project ‘Investigating the causes of the decline in the number of applications to the civil courts’]. Federal Ministry of Justice of Germany.

- Miller, G., & Eisenberg, T. (2009). The market for contracts. Cornell Law Faculty Publications. Paper 418. http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/facpub/418.

- Ministry of Law. (2007). Report of the committee to develop the Singapore legal sector. https://www.mlaw.gov.sg/files/news/press-releases/2007/12/linkclicke1d7.pdf (accessed 22.05.2024).

- New York Courts. (2012). The Chief Judge’s task force on commercial litigation in the 21st century – report and recommendations to the Chief Judge of the State of New York. New York Courts, New York.

- NYCD. (2006). Celebrating a twenty-first century forum for the resolution of business disputes. NY Supreme Court.

- OECD. (2023). Country webiste - Kazakhastan [WWW Document]. https://www.oecd.org/countries/kazakhstan/.

- Pistor, K. (2019). The code of capital: How the law creates wealth and inequality. Princeton University Press.