Abstract

Finance plays an increasing role in the global governance of sustainability. To explain the rise of finance, scholarship is increasingly turning to the financial sector as a producer of policy-relevant knowledge. However, scholarship has paid little attention to how differences within the financial sector affect such knowledge production. This article differentiates two important ways how the financial sector addresses sustainability: investments following environmental, social and governance (ESG) standards, and impact investing. Whereas diversified ESG investing is centered around index and data providers, impact investors manage non-listed assets and develop idiosyncratic ‘impact’ approaches. I introduce the term ‘epistemic gerrymandering’ to describe how impact investors tailor ‘impact’ to their financial portfolios and to explain how the resulting heterogeneity and ambiguity is stabilized. Tracing the historical development of impact investing from three distinct strands into a transnational club, I argue that the club structure, together with impact investors’ proximity to private wealth management, explains the persistence of epistemic gerrymandering. As a knowledge regime, epistemic gerrymandering reinforces three dynamics of particular importance to political economists: the subjugation of sustainability to financial returns, the restriction of access to epistemic arenas to wealthy elites, and the rechanneling of charitable and public resources to de-risk private investments.

Introduction

Financialization has been a central theme in political economy scholarship over the past decades (Mader et al., Citation2020). Scholars have stressed the role of the state in enabling the rise of finance and have investigated the manifold transformations of states facing increasingly powerful and globalized financial markets (Krippner, Citation2011; Wang, Citation2020). In this context, many governments and international organizations have increasingly tried to achieve policy outcomes on issues as diverse as international development, social policy, and, in particular, ecological sustainability by governing through financial markets (Braun et al., Citation2018; Dowling & Harvie, Citation2014; Gabor, Citation2020). This paradigm shift has been accompanied by significant changes in the epistemic arenas surrounding the respective policy issues, which have seen a change in partaking actors and dominant ideas (Golka & van der Zwan, Citation2022; Seabrooke & Stenström, Citation2023). In many cases, these changes have led to an ‘intellectual capture’ by the financial sector that has rendered the turn to finance into a salient—and persistent—policy option (Berry et al., Citation2022; Oren & Blyth, Citation2019; Seabrooke & Tsingou, Citation2021).

With increasing financialization, differences within the financial sector gain structuring importance. Reassessing the classic distinction between bank-based and market-based financial systems (Hall & Soskice, Citation2001), research has documented the global rise of asset managers and has pointed to their significance in economic governance (Braun, Citation2022; Voss, Citation2024). As asset managers gain in centrality, differences in how they earn profits and allocate resources become increasingly important (Benquet & Bourgeron, Citation2022; Braun, Citation2022). However, little is known about whether and how this translates into wider epistemic differences. How do asset managers’ different financial practices inform how they see the world and what ideas they promote? And what political and economic consequences arise from such differences?

This article addresses these questions by examining differences in the financial governance of sustainability, understood as the practices through which financial actors organize and manage the pursuit of sustainability. These practices are structured around different financial instruments and relational arrangements with financial and nonfinancial actors, translating into distinct ideas of sustainability and modes of knowledge production. Understanding these differences is of particular importance in times when the mobilization of private finance is becoming a dominant policy approach to address sustainability issues in areas ranging from international development to economic policy (Gabor, Citation2020).

I contrast two key approaches to the financial governance of sustainability: investment according to environmental, social, and governance criteria (ESG), and impact investing. ESG investing is mostly performed by institutional investors and large asset managers, on markets for listed products, and with the help of index and ESG providers (Baines & Hager, Citation2022; Petry et al., Citation2021). Impact investing, by contrast, is a form of ‘alternative finance’ that operates mostly in non-listed, private markets and gives privileged access to the ultra-wealthy (Benquet & Bourgeron, Citation2022; Stolz & Lai, Citation2020). These differences have important repercussions for the production and use of sustainability knowledge. In ESG investing, intermediaries such as index providers act as standard-setting bodies, making ESG vulnerable to accusations of greenwashing when standards are violated or used strategically (Fichtner et al., Citation2023). In impact investing, understandings of sustainability—or ‘impact’—are highly idiosyncratic and often deployed equally strategically (Barman, Citation2020; Langley, Citation2020a). Paradoxically, however, this does not seem to negatively affect public support for impact investing, including from prime ministers, Hollywood actors, and Pope Francis (G8,8, Citation2014; Gabor, Citation2020).

What explains these differences regarding the creation, use and acceptance of sustainability ideas? I introduce the notion of epistemic gerrymandering to capture the epistemic strategies and ecology that underpin impact investing. Gerrymandering commonly refers to the strategic redrawing of boundaries of electoral districts for political gain, but it has also been used to describe other forms of strategic boundary construction, including in the production of social scientific knowledge (Woolgar & Pawluch, Citation1985). In this sense, financial actors engage in gerrymandering when they tailor ideas—what they refer to as green, sustainable, or impactful—to a given portfolio of financial investments, and/or when they change the meanings of these concepts as their portfolio changes. This observation alone is hardly new: Critical publics frequently accuse corporate and financial actors of greenwashing, and critical scholars of financialization have pointed to various ways in which finance ‘colonizes’ (Chiapello, Citation2015), ‘harnesses’ (Dowling & Harvie, Citation2014) or ‘folds’ (Langley, Citation2020b) policy issues such as social welfare into the pursuit of profit. Epistemic gerrymandering goes beyond exposing financial actors’ strategic use of ideas: it describes a knowledge regime in which gerrymandering is a largely accepted approach to knowledge creation. In such a knowledge regime, the potpourri of idiosyncratic meanings that result from actors’ gerrymandering is allowed to coexist, creating a seemingly paradoxical situation of stability in ambiguity.

As the case of impact investing shows, epistemic gerrymandering merges particular power positions and collective structures. In impact investing, epistemic gerrymandering emerges because private markets allow investors to gerrymander notions of impact to their investment portfolios, and because the collective structure of a transnational club incentivizes and sustains these idiosyncrasies. Transnational clubs are formed by elite actors, based on peer recognition, and build a coherent external front while allowing for significant internal heterogeneity (Tsingou, Citation2014, Citation2015). Impact investing emerged as a transnational club after elite actors in three previously different fields—domestic markets, international development, and social welfare—began to identify themselves under the ‘impact’ label. Due to this amalgamation, impact investing lacked (and still lacks to date) a substantive definition of ‘impact’ as well as credentializing institutions, making acceptance as an impact investor primarily a question of peer recognition. However, the need to gain peer recognition in the form of impact success stories creates incentives for gerrymandering, which are further strengthened by investors’ position on private markets with significant definitional authority but constrained ‘exit’ opportunities. Epistemic gerrymandering is also beneficial for the club overall as the plethora of impact reports and case studies produced by investors suggests an overwhelmingly supportive evidence base for impact investing that ideational entrepreneurs seeking to mobilize support—and subsidies—for impact investing can draw upon.

This article makes two main contributions. First, it adds to recent scholarship stressing the importance of asset managers by pointing to important differences between public and private financial markets (Benquet & Bourgeron, Citation2022; Braun, Citation2022). In markets for listed equities, asset managers’ portfolio diversification makes them dependent on index and ESG data providers that play an important role in governance and standardization (Braun, Citation2022; Fichtner et al., Citation2023). By contrast, definitional ambiguity prevails in markets for non-listed impact investments. Second, introducing the notion of epistemic gerrymandering, this article shifts the attention from what financial actors’ ideas are towards what they do. Whereas accusations such as greenwashing reflect the critical evaluation of a truth claim—whether or not investments are, in fact, green—epistemic gerrymandering liquefies the underlying evaluative basis. Under epistemic gerrymandering, it is difficult to judge whether or not an investment is, in fact, impactful because the accepted meanings of ‘impact’ are so heterogeneous: ‘impact’ means whatever impact investors do. What epistemic gerrymandering does is therefore to create a boundary between resource-rich insiders enabled to customize ‘impact’ to their investments, and outsiders deprived of definitional authority and evaluative capacity.

This article proceeds by contrasting ESG and impact investing as key approaches to the financial governance of sustainability, followed by a methods section. Section four describes how impact investing emerged as a transnational club and points to the link between the club structure and epistemic gerrymandering. Section five gives concrete examples of epistemic gerrymandering in impact investing and points to three important implications for political economy scholarship: the subjugation of sustainability knowledge to financial returns, the transformation of access to governance arenas, and the reconfiguration of developmental policies towards the creation of financial assets. The conclusion points to the wider societal importance of epistemic gerrymandering, discusses limitations, and proposes questions for future research.

The financial governance of sustainability

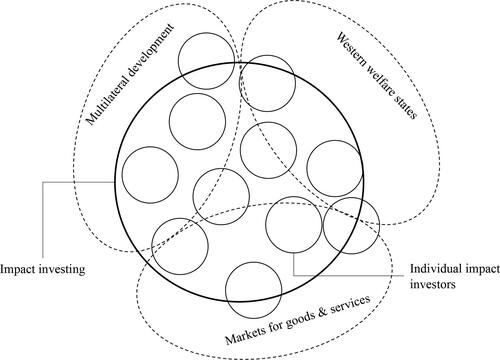

Authority in global governance has been understood as a competition between organizational networks over who controls issues (Henriksen & Seabrooke, Citation2016). The financial governance of sustainability shows that such competition also exists between groups within the financial sector. Despite some overlap, ESG and impact investors differ significantly regarding the partaking actors, their financial and epistemic practices, the suppliers and targets of their investment capital, as well as the role of nonfinancial actors in the governance process (see ).

Table 1. Ideal-typical distinction between ESG and impact investing.

Over the past years, ESG investing has become a focal point of political economy scholarship (Baines & Hager, Citation2022; Fichtner et al., Citation2023). Severe criticism aimed at the financial sector in the wake of the global financial crisis, increasing climate urgency, as well as a global ‘savings glut’ following post-crisis quantitative easing have led to a steep growth of ESG investments. According to Bloomberg (Citation2022), global ESG assets have reached $35 trillion in 2020, and financial actors owning or managing a total of $121 trillion have signed the United Nation’s Principles for Responsible Investing (UN PRI, Citation2022). Having to manage financial assets worth billions or trillions of dollars has put investors and asset managers under considerable pressure to reduce the implementation cost of ESG. As a result, index and data providers offering low-cost, standardized ESG products have become central governing actors in institutional ESG investing (Hiss, Citation2013; Maechler, Citation2022; Petry et al., Citation2021).

ESG investing consists of three main practices: screening, divestment, and engagement. Screening refers to asset allocation based on an assessment of potential investees’ ESG performance. ESG information is usually supplied by dedicated data providers and forms the basis for selection strategies such as ‘best in class’ (i.e., selecting investees with the highest ESG score in each industry). More frequently, however, investors are not developing ESG portfolios themselves but invest into products offered by asset managers and index providers (Petry et al., Citation2021). In addition to screening, some investors also divest from specific firms or industries (such as fossil fuel companies) due to ethical concerns or pressure from divestment campaigns (Baines & Hager, Citation2022). ESG investors may also engage directly with executives of investee firms (e.g., during bond issuance) and vote in shareholder meetings. For institutional investors, voting can easily amount to thousands of votes per year, which is why it is often outsourced to specialized providers or asset managers (Braun, Citation2022).

Institutional ESG investors have only little say over investees’ corporate governance as their stakes in individual companies are negligible. This means that large asset managers have considerable authority in sustainability governance as they bundle together financial flows from various institutional investors. However, asset managers have little incentive and few tools to pressure firms towards more sustainability as their remuneration is independent of performance and share prices play only a marginal role in corporate financing (Braun, Citation2022). Yet, facing significant competition for fund inflows, asset managers do have a strong incentive to cater for growing demand for ESG assets. Some asset managers have responded to this demand by repackaging existing products into ESG, prompting allegations of greenwashing. For example, a recent market report found that the vast majority of 114 analyzed ESG funds hardly differed from non-ESG ones, with one ESG fund investing exclusively into fossil fuel companies (Senn et al., Citation2022).

Impact investing differs from ESG investing in several ways. According to a market survey from the Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN, Citation2020a, pp. 25–36), impact funds are relatively small, featuring median assets under management of $37 million. Most impact funds (76%) invest directly into companies, rather than into asset management portfolios. By far the biggest number of impact investors operate on private equity (70%) and private debt (58%) markets, with only a minority holding listed equities (17%) or debt (15%). These figures have remained relatively stable since the first survey in 2012 (GIIN, Citation2013). Most impact investors invest into early stage (63% venture stage and 76% growth stage) rather than mature companies. Impact funds usually buy large minorities or controlling majorities of a small number of non-listed firms on which they exert significant and continuous influence, often through board seats and regular meetings (Himmer, Citation2023). Impact funds usually receive an annual management fee, but their main source of income is a share of profits received at the end of the fund’s lifespan (Bourgeron, Citation2020). As these profits are made from high multiples on exit, impact investing funds often follow the model of the venture capital industry of imposing hypergrowth on their portfolio companies (Cooiman, Citation2021; Golka, Citation2023).

Impact and ESG investing also differ in their upstream relations to funders. The main sources of ESG capital are institutional investors such as pension funds, which, in many countries, are subject to detailed regulations to ensure accountability and fiduciary duty (Ebbinghaus, Citation2011). By contrast, most impact investors are closely related to private wealth management, managing funds from ultra-wealthy clients, such as foundations (60%), high net-worth individuals (56%) and family offices (51%), which also show the highest growth rates (GIIN, Citation2019). Private wealth management is shrouded in secrecy and actively seeks to avoid public scrutiny, enabling wealthy elites to gain autonomy from national institutions such as taxation (Harrington, Citation2016, p. 52). As private wealth management requires the creation of complex legal arrangements within and across national jurisdictions (Pistor, Citation2019), wealth managers develop idiosyncratic solutions and are opposed to standardization and codification by third parties that could limit their authority (Harrington, Citation2016, p. 73; Seabrooke & Wigan, Citation2017, p. 11).

Private wealth managers may therefore see impact investing as a strategy to manage the reputation risk that emerges as offshore wealth management and its ‘tax-shy clients’ face critical media reporting such as the Panama Papers (Sharman, Citation2017, p. 36). One example is the Liechtenstein private bank LGT that, after being engulfed in numerous public scandals in the early 2000s, in 2007, set up a Venture Philanthropy division that quickly became one of Europe’s leading impact investors. Its investment into Indian off-grid electricity supplier Husk Power Systems has been featured in multiple case studies and media reports, thus creating positive media attention for LGT. Embracing impact investing also helps private wealth managers in the competitive struggle for funds. Often seen as ‘cost centers’ by the wealthy (Harrington, Citation2016, p. 72), claiming social and environmental impacts can—as indicated by a recent interview study with impact fund managers in Geneva (Kabouche, Citation2024)—help wealth managers to sustain networks with high net-worth individuals. This means that, ideal-typically, impact investing represents the wealth elite’s approach to the financial governance of sustainability, whereas ESG reflects institutional investors’ approach.

Data and research methods

To develop the arguments presented in this article, I followed the abductive analysis methodology (Tavory & Timmermans, Citation2014). Abductive analysis is increasingly used by political economists to develop explanations for novel or inadequately understood empirical phenomena (Ylönen et al., Citation2024). It is performed by systematically ‘casing’ an empirical research puzzle against various theoretical perspectives until one is found that, if true, would provide an appropriate explanation (Tavory & Timmermans, Citation2014). While this allows for the construction of empirically grounded theory, it requires to forego some internal heterogeneity for the sake of conceptual clarity. For this article, this means that, although epistemic gerrymandering can explain much of the meaning-making in impact investing, it does not imply that it is the only epistemic strategy used by all impact investors at all times. Exploring potential heterogeneity in epistemic approaches thus remains an open question for future research using different methodologies.

My empirical analysis proceeded in three steps. First, I gained an in-depth understanding of impact investing based on scholarly and professional experience. Professional experience included co-raising blended impact finance for an international development project, preparing an impact report and B Corporation (B Corp) certification for a retail company, as well as participation in various impact investing conferences, including the 2012 Social Capital Markets Conference in Malmö, Sweden. Empirical materials included 15 interviews with impact investors, impact consultants, donors and policymakers (see Appendix), an analysis of reports and websites (including historical changes via the Internet Archive) from impact investors and industry associations. To map the heterogeneity of impact investing, I conducted a qualitative content analysis of 31 impact reports selected for representativity from a self-developed database of over 300 reports. To reconstruct the historical development of the British strand of social impact investing, I furthermore analyzed over 100 policy documents. For the other two strands I relied on the grey literature mentioned above as well as scholarly sources. Finally, I studied all articles on impact investing in major academic journals (around 100 papers by spring 2021) to gain an overview of the processes of and the actors involved in—and excluded from—impact investors’ sustainability governance.

Second, as I began to study impact investing, I was puzzled by its ambiguity and internal heterogeneity. My first observation was that what investors understood as impact was closely related to their investment portfolio. As I found evidence where more rigid forms of impact measurement and evaluation had been abandoned due to financial concerns, I developed the notion of epistemic gerrymandering. Realizing that the ‘interpretive flexibility’ of the impact label (Barman, Citation2020) could explain epistemic gerrymandering at the level of individual investors, I began to understand that the emergence and perpetuation of such a flexible notion of impact on the collective level was linked to the gradual amalgamation of impact investing into a transnational club.

In a third step, I validated and refined the conceptual ideas. Checking whether the developed concepts were in line with my empirical material, I realized that the importance impact investors ascribe to a double bottom-line track record—and the inherent differences between financial and impact results—further supported my argument. To assess the reliability of my findings, I collected new impact statements from leading impact investors and assessed whether these, too, could be understood through epistemic gerrymandering.

Impact investing as a club

The emergence of a club

As if to epitomize the exclusive nature of a club, the impact investing label emerged in 2007 during an event at the Rockefeller Foundation’s pompous Bellagio Center at Lake Como in Italy. In the following years, a transnational club emerged out of the amalgamation of three previously distinct approaches of private market investing with sustainability intentions. The term ‘impact’ emerged as a relatively empty signifier allowing the three groups to cooperate while maintaining their idiosyncratic perspectives (Barman, Citation2015, Citation2020). The first approach was developed by a group of investors and entrepreneurs in the US around the so-called B Corporation movement to strengthen environmental, social and governance standards in the domestic economy (Collins & Kahn, Citation2016). Key to promoting B Corporations was the not-for-profit organization B Lab, which received considerable donations from philanthropic donors such as the Rockefeller and Skoll foundations. These efforts resulted in the creation of the B Impact Assessment for firms and the GIIRS rating system for investors, which were of particular importance as they allowed drawing a symbolic boundary between impact and ‘mainstream’ companies and investors (Barman, Citation2020; Chiapello & Godefroy, Citation2017).

The second group was comprised of philanthropists and investors advancing financialized approaches to international development (Jafri, Citation2019). This approach drew on the idea of microfinance, and gained significant momentum in the early 2000s as microfinance entrepreneur Muhammad Yunus won the 2006 Nobel Peace Prize (Mader, Citation2015). Around the same time, US tech billionaires became interested in entrepreneurial approaches to international development, setting up ‘philanthrocapitalist’ foundations such as the Gates Foundation (founded in 2000) or Omidyar Network (founded in 2004) to fund development entrepreneurship and building supportive organizational infrastructures such as the Aspen Network of Development Entrepreneurs (Kumar & Brooks, Citation2021; McGoey, Citation2021). The rise of development entrepreneurship in the US also created demand for US financial capital to be invested in the Global South, leading to the creation of funds such as Acumen Fund (founded in 2001) that are known today as leading impact investors. In parallel, ideas such as ‘blended value’ or ‘venture philanthropy’ emerged that abstracted from the case of development entrepreneurship to a more general idea of using for-profit investments, aided by derisking from public and charitable sources, to scale entrepreneurial ventures to address various societal challenges (Bishop & Green, Citation2008; Emerson, Citation2003; Freireich & Fulton, Citation2009). The main proponent of the blended value idea, Jed Emerson, later founded the annual Social Capital Markets (SOCAP) conference, a key global impact investing event.

The amalgamation of both groups was advocated by issue entrepreneurs such as Jed Emerson and Anthony Bugg-Levine, then managing director of the Rockefeller Foundation. Issue entrepreneurs are actors that develop ideas and mobilize support for them, and are therefore well-positioned to forge transnational clubs (Henriksen & Seabrooke, Citation2016; Tsingou, Citation2015). Following the Rockefeller Bellagio meeting, in 2009, the Rockefeller Foundation, USAID, and JP Morgan jointly gave $3.25 million to the newly founded Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN) and for the development of the impact investing industry (USAID, Citation2009). In 2010, an important report by JP Morgan labeled impact investing an ‘emerging asset class’ and projected a market size of $1 trillion within a decade. The report also differentiated impact investing from ESG by framing ESG as a way to ‘minimize negative impact rather than proactively create positive social or environmental benefit’, as ascribed to impact investing (JP Morgan, Citation2010, p. 5). In their landmark book Impact Investing, Emerson and Bugg-Levine (Citation2011, pp. 9-10) further strengthened the boundary to institutional ESG investing, noting that impact investors ‘focus on venture investing, private equity and direct lending because of the unmatched power of these investments to generate social impact’, and argued that charitable and public funds should be used to de-risk such investments.

The third strand, also called social investment, focused on the transformation of the welfare state and only became part of impact investing in the mid 2010s. In contrast to the US-led strands of impact investing, social investment emerged in the UK in the late 1990s and remained a largely domestic phenomenon until the early 2010s. Early social investors around former venture capitalist (and key political donor) Ronald Cohen saw the transformation of domestic welfare states under the auspices of New Public Management as an opportunity to create new financial assets (Dowling, Citation2017). Emergent financial intermediaries Bridges Ventures and Social Finance built on new trends in social welfare evaluation—distinguishing ‘impact’ and ‘outcomes’ of a social policy intervention from its ‘outputs’ and ‘inputs’—to launch so-called Social Impact Bonds (SIBs) that turned the delivery of social outcomes into investment opportunities for financial investors (Broom & Tchilingirian, Citation2022; Dowling & Harvie, Citation2014; Wiggan, Citation2018).

Social investment became part of impact investing as the latter became increasingly popular among global elite groups. The World Economic Forum (WEF) played an important role for the rise of impact investing. Its founders, Klaus and Hilde Schwab, who also founded the Schwab Foundation for Social Entrepreneurship in the late 1990s, saw impact investing as key to fostering social enterprise (Schwab Foundation, Citation2013). The WEF not only put impact investing on its agenda, but also worked towards popularizing it among high net-worth individuals and their family offices (WEF, Citation2014). Just as the WEF sought to push impact investing ‘from the margins to the mainstream’ (WEF, Citation2013), the then British Prime Minister David Cameron, for whom ‘boosting’ social investment was a political priority (Wiggan, Citation2018), made social and impact investing a focal point of the British G8 presidency in 2013. The work of the G8 on impact investing resulted in a landmark report that brought together all three strands of impact investing (G8,8, Citation2014), and forged a global network of impact investors that, as the Global Steering Group, continues to exist to date.Footnote1

How could a practice with such internal heterogeneity develop into a transnational club with a shared identity? Issue entrepreneurs such as Emerson, Bugg-Levine and Cohen were of particular importance in this process by mobilizing elite support and, especially, by propagating a notion of ‘impact’ that allowed each of the three main constituent groups to maintain their practices and interests. As Barman (Citation2020) argues, the term impact is a ‘boundary object’ and serves to place ESG outside of impact investing while remaining open to interpretive flexibility for insiders. This is witnessed in commonplace definitions of impact investing as a ‘spectrum’ of approaches, which date back to an influential report published in 2009 by the Monitor Institute (which received considerable funding from the Rockefeller and JP Morgan foundations). This report developed a widely cited distinction between ‘finance first’ and ‘impact first’ investors that give preference to either financial or ‘impact returns’ (Freireich & Fulton, Citation2009). But while the ambiguity surrounding the meaning of ‘impact’ facilitated the creation of a shared identity among a heterogeneous group of investors, it rendered impossible the creation of a shared, substantive definition of impact based on explicit and consistent criteria. As a result, continuous confusion and unsettled debates among practitioners and business scholars exist as to what ‘impact’ actually is (Barman, Citation2015; Chiapello & Godefroy, Citation2017; Schlütter et al., Citation2023). However, as argued throughout this article, the question of what impact is of much less importance than what it does with regards to sustainability knowledge.

The historical developments described above have shaped a peculiar structure of impact investing as a transnational ecology that spans different institutional terrains while being only weakly institutionalized itself (see ). Impact investing bridges institutional boundaries as it links the three distinct strands described above. Its proponents are vocally critical of the ‘silos’ distinguishing markets, states, and not-for-profit organizations (Golka, Citation2019). It also allows investors to invest across institutional terrains depending on their thematic preferences. For example, Bridges, a leading British impact investor, invests, among other things, into renewable energy, real estate, and Social Impact Bonds (Bridges Fund Management, Citation2023). Mapping the international development subset of impact investing, Faul and Tchilingirian (Citation2021) have argued it is a ‘space between fields’ defined by dense network structures that privilege the voice of funders. For impact investing overall, my argument goes one step further. Due to the ambiguity surrounding impact, its anchoring in private markets and its link to the wealth elite, impact investing can be understood as a club void of centralized institutions such as third-party rating providers and granting virtually unconstrained authority to each investor. As explained by the CEO of an impact fund, impact is little more than a ‘theme’ that investors choose freely and that ‘may as well be (…) aerospace’ (Interview 2). However, featuring dense internal network structures akin to a ‘class reunion’ where ‘everyone knows everyone’ (Interview 1), the club structure of impact investing does affect individual investors: as described below, it incentivizes epistemic gerrymandering.

Impact and peer recognition

Transnational clubs are elite communities whose members are motivated by a common goal and peer recognition (Tsingou, Citation2015). Club membership is not determined by formal credentials or institutional positions but derives from peer recognition. One vital source of such recognition is, as Tsingou (Citation2015, p. 226) describes, the ‘ambition to provide global public goods in line with values [club] members consider honorable’. However, this does not entail that club membership results from shared ideological positions, as club members are ‘concerned with esteem and prestige among peers in the professional community rather than advocacy of certain positions’ (Seabrooke & Tsingou, Citation2014, p. 402). For example, private wealth management can be understood as a club not only because of its dense, transnational network structure, but particularly because wealth managers ‘see their work as governed by an ethic reminiscent of medieval knighthood: an aristocratic code based on service, loyalty, and honor, dedicated to the cause of defending large concentrations of wealth from attack by outsiders’ (Harrington, Citation2016, p. 47).

In this sense, impact investing is a transnational club. Whether or not self-labeled impact investors are accepted as such is less a matter of formal institutions, credentials or centralized governing bodies, but much more a question of peer recognition. Peer recognition can, for example, be observed at international conferences such as Social Capital Markets, where investors showcase their portfolio and its claimed impact. These impact presentations are often emotionally charged narrations that include graphic illustrations, quantitative impact metrics, and/or descriptions of the ‘theory of change’ investors ascribe to their investments. Such impact narrations can gain peer recognition, for example, by receiving praise in panel discussions, by being featured as ‘best practices’ in reports from industry organizations, think-tanks, transnational organizations such as the G7/8, or through various awards. The most important source of peer recognition, however, is what impact investors call a track record of double (or triple) bottom line delivery. An impact fund has such a track record when others acknowledge that its previous investments have produced financial returns as well as measurable social or environmental impacts. According to a market survey, delivering such a track record is of greatest importance for impact investors (GIIN, Citation2020a, pp. 22-23).

My argument is that the importance of such a track record for peer recognition, combined with the ambiguity surrounding—and investors’ near unconstrained authority over—notions of impact, creates strong incentives for epistemic gerrymandering. As described in section 2, impact investors operate mostly in private markets where they buy significant stakes in relatively early-stage companies. As these markets are much less liquid than those for listed equities, and because impact funds invest only into a small number of companies, each investment creates considerable sunk costs and cannot be exited easily when the assessed impact performance is insufficient. Although the notion of a ‘double’ bottom line assumes an equivalence between financial and impact results, both are highly different socio-material artefacts: a recognized flow of money versus a narrative description presented in impact funds’ own reports that, in the absence of third-party evaluators, can be adjusted or retrofitted rather easily. While investors can decide relatively freely over the rigor of their impact measurement and the consistency with which these measurements are applied to the investment process, they must showcase positive impact results to become accepted as impact investors. Impact investors thus face a moral hazard problem. One strategy that maximizes investors’ chances to show a double bottom line track record is thus to focus on the generation of financial returns and to tailor notions of impact around given financial commitments—in other words, to engage in epistemic gerrymandering.

Epistemic gerrymandering and the club structure of impact investing are inextricably linked. For individual investors, epistemic gerrymandering helps to gain peer recognition and to become an accepted member of the impact investing club as described above. On the collective level, the impact investing club also benefits from the gerrymandering done by its members. Compared to more rigid impact measurement approaches such as randomized control trials or external evaluations that could potentially expose negative impacts, gerrymandered impact narratives are risk-free and cheap to produce. The plethora of seemingly positive case examples resulting from investors’ gerrymandered impact descriptions serves as an important resource for ideational entrepreneurs to showcase the distinctiveness and effectiveness of impact investing vis-à-vis funders, policymakers and the general public. To the extent that this gerrymandered ‘evidence’ helps convince policymakers and charitable donors to support impact investing, impact investors’ position is reaffirmed, making future support more likely—a process known as ‘recursive recognition’ (Broome & Seabrooke, Citation2020).

Impact investing and the political economy of epistemic gerrymandering

This section describes practices of epistemic gerrymandering in impact investing in more detail and connects them to three important politico-economic consequences. The first one concerns the core of epistemic gerrymandering: as notions of impact are developed through the use of financial investments as epistemic devices, ideas surrounding impact are subjugated to the pursuit of financial returns. Second, the rise of impact investing may further restrict access to the creation of knowledge in various terrains of global governance to investors and the wealthy. Third, impact investing fuels the assetization of developmental policies as it advocates rechanneling public and charitable funds to derisking financial investments.

Subjugating sustainability to the pursuit of financial returns

There are at least five common practices of epistemic gerrymandering that allow impact investors to subjugate impact to the pursuit of financial returns: developing idiosyncratic notions of impact, the strategic use of external standards, commensuration and low ambition levels, linking impact to financial profit, and retrofitting notions of impact to match investment requirements. As Paul Langley (Citation2020a) argued, impact investors may pursue a ‘liberal ethics of financialization’ by which they may choose the social or environmental standards or metrics they do or do not seek to adhere to and adjust them over the lifecycle of their fund. A growing number of studies has found that impact investors’ understandings of impact are developed idiosyncratically (Bourgeron, Citation2020), or on the basis of ‘gut feeling’ (Hellman, Citation2020). This is reflected in a recent survey where 91% of respondents indicated selecting impact metrics themselves (GIIN, Citation2020b, p. 35). Although a small number of funds have impact management divisions, most impact funds (73%) spend less than 10% of their budget on impact management (GIIN, Citation2020b, p. 45). The quality of impact metrics thus remains low, with measuring outputs—i.e., the very approach impact investors vocally oppose—being by far the most popular approach (91%), and less than a third of respondents attempting to attribute investment effects through counterfactuals (GIIN, Citation2020b, p. 41). This corresponds to recent ethnographic work showing that funds apply ‘toothless’ impact metrics that are used neither to inform investment decisions nor to strengthen investees’ pursuit of impact (Himmer, Citation2023).

Despite its constitutive importance for impact investing, investors apply surprisingly heterogeneous understandings and lax measurements of ‘impact’. This can be seen, for example, in the most recent impact reports of some of the oldest and most well-known impact investors: Acumen in the US, Bridges in the UK, and BlueOrchard in continental Europe. Acumen seeks to ‘solve the toughest challenges of poverty’ by investing into businesses across a variety of sectors mainly in the Global South (Acumen, Citation2023, p. 1). Its 2022 impact report presents total numbers of invested dollars and investee companies, in addition to individual case descriptions. The three investment vehicles of Acumen’s investment subsidiary, Acumen Capital Partners, present individual impact reports with meanings of impact that are tailored to each fund’s respective investment focus.Footnote2 Bridges also uses different understandings of impact tailored to its respective investment vehicles, ranging from real estate to green industries and social outcomes (Bridges Fund Management, Citation2023, pp. 8-9). Its impact report also presents aggregated output figures and case examples but gives only few concrete details regarding its measurement methodology, lacking an exhaustive description of metrics, targets and relative changes. A similar pattern can be seen in BlueOrchard’s 2022 impact report, which mainly lists output figures such as ‘number of lives involved’ and notions of impact tailored to respective fund vehicles.Footnote3

In the absence of centralized governance institutions and with considerable authority to define impact themselves, impact investors turn to external standards to signal their credibility. In a market survey, investors indicate growing concerns about ‘impact washing’ that they seek to counteract through the use of standards such as the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs, 73% of respondents), IRIS metrics (46%), or B Corp certifications (18%) (GIIN, Citation2020a, p. 46). However, these standards do not constrain investor authority and only minimally increase accountability as the epistemic ecology surrounding impact investing allows for their strategic use. The most-widely used standard is the UN SDGs, where funds often retroactively identify those SDGs to which their investment vehicles are projected to contribute. A case in point here is the Builders Fund—named the ‘best of world’ impact fund by metrics provider B Labs—whose impact report describes how ‘alignment’ with 13 of the 17 SDGs was determined by examining its current investment portfolio (Builders Fund, Citation2020, p. 14). To qualify SDG alignment, the fund reports whether it is ‘avoiding harm’, ‘benefitting stakeholders’, or ‘contributing to solutions’ (p. 25). However, no reporting is provided with regards to the 169 targets and 231 indicators that are also part of the SDGs. Other award-winning impact investors such as BlueOrchard use similar strategies to claim SDG alignment without establishing consistency, transparency and accountability with regards to targets and indicators.

Another form of epistemic gerrymandering is the use of impact metrics that set purposefully low ambition levels or allow offsetting lower performance in one impact area with successes in another. A case in point here is the B Corp certification, which is based on the GIIRS. The B Corp certification builds on a comprehensive assessment of firms’ business model and processes in the areas of governance, workers, community, and environment. However, B Corp certifications can be obtained with only 80 out of 200 points.Footnote4 When I prepared a B Corp certification for a consumer goods company, merely following Western European laws and standards gave enough points to meet the certification threshold. Combining a low ambition level paired with commensuration, the B Corp certification gives ample opportunities to offset lower scores in one area with higher scores in another.

In other cases, the design of impact metrics is purposefully weak. For example, many impact investors use impact metrics that closely correlate to financial performance. Calculations of the ‘number of lives affected’—without further clarifying the quality of change or attributing it to the investment—are frequently used, as is equating the number of customers (e.g., of climate insurance products) with impact. Both of these figures are, for example, used in the BlueOrchard impact report mentioned above. Another example is the calculation of ‘avoided’ carbon emissions that is part of various impact reporting frameworks (such as IRIS) and used by leading impact investors such as Bridges (Bridges Fund Management, Citation2023, p. 20, 22) and the Acumen subsidiary, Kawisafi Ventures (Citation2023, p. 3), although this metric has been criticized as a means to legitimize carbon emissions and does not count towards more rigorous standards such as Science-based Targets.Footnote5

Impact investors may also develop impact metrics that legitimize or even entrench their financial return expectations. Social Impact Bonds (SIBs)—public service delivery contracts that tie financial returns to the delivery of measurable social outcomes—are a case in point here (Chiapello et al., Citation2020; Dowling, Citation2017; Fraser et al., Citation2018). The idea of SIBs is to fund innovative, preventative social services where financial returns are paid for delivered social outcomes (such as a measured reduction of prisoner recidivism) rather than outputs (such as a number of delivered trainings). However, as outcomes take time to materialize, outcome payments can only be made much later than output payments, effectively lowering the net-present value of SIB investments. This creates incentives for epistemic gerrymandering. For example, SIB developer Social Finance argues that the number of job placements is a meaningful outcome metric for SIBs in education. However, because the time lag between educational interventions and job placements would reduce investor returns, they argue that school grades should be used as immediate ‘surrogate outcomes’ to trigger investor payments (Social Finance, Citation2015). In another SIB, mere participation in psychotherapy interventions, rather than the resulting sociopsychological outcomes, has been used to ‘frontload’ payments to investors (Neyland, Citation2018). Investors and SIB developers may also apply strategies such as ‘creaming’ the easiest cases and ‘parking’ the most difficult ones in order to enhance outcome payments (Carter, Citation2021). Epistemic gerrymandering is not only used to increase investor returns but also to reduce risk: in SIBs as well as other impact projects, initial ideas of linking the measurement of outcomes to randomized control groups have been abandoned because such evaluations increase costs and uncertainty for financial investors (Al Dahdah, Citation2019; Williams, Citation2020).

Epistemic gerrymandering also occurs on the level of impact investing discourse. To enter arenas of global governance, impact investors problematize various social situations and theorize impact investments as a means to deliver efficient and scalable solutions that ‘produce only winners’ (Burnier et al., Citation2022). Impact investing discourse is gerrymandered around financial returns by legitimizing high financial returns as ‘market’ expectations while ignoring virtually all issues that threaten investor returns, such as taxation, wage and pension increases, or unionization (Golka, Citation2023). Indeed, redistribution from Labor to Capital is at the heart of many impact investing models. A particularly striking example is the case of award-winning for-profit firm K10 that creates a ‘pathway to employment’ in the construction industry while paying its apprentice workforce low stipends rather than full salaries. Placement into such apprenticeship programs has also been discussed as an outcome metric for SIBs (Golka, Citation2019, p. 98). Finally, ideas of co-operative legal forms, worker co-ownership or works councils that would threaten investor control have also been pushed to the margins of impact investing discourse (Beyster, Citation2017).

Epistemic closure

Impact investors’ authority over the definition and measurement of impact may fuel epistemic closure, whereby nonfinancial actors are pushed out of the epistemic arenas in which sustainability knowledge is created. One important aspect of this development is legal codification (Pistor, Citation2019), where proposed regulatory changes would enshrine investor authority into law. For example, the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation (IFC) argues that, to stimulate the growth of impact investing, ‘reforms should aim to allow asset owners to pursue additional goals beyond financial returns if they prefer to do so’ (IFC, Citation2019, p. xvi; emphasis added). While such demands entail a reform of fiduciary duty to allow the pursuit of aims other than profit maximization alone, they also strengthen investor authority over the definition of impact. In the rare cases of existing impact investing regulation, such as the European Social Entrepreneurship Funds (EuSEF) vehicle introduced by the European Union, this has indeed been the case. Although Article 3a (ii) of the EuSEF legislation makes investor pursuit of ‘measurable, positive social impacts’ mandatory, their definition remains subject to the respective fund’s articles of association, and thus impact investors’ discretion (European Union, Citation2013).

Epistemic closure may also reach into the realm of policy, where impact investing magnifies the voice of the ultra-wealthy. The literature on professional dynamics has shown that financialization is often accompanied by a change in professional networks whereby access to ideational fora is increasingly limited to particular biographies, status positions, or professions (Ban et al., Citation2016; Boussard, Citation2018; Golka & van der Zwan, Citation2022). Impact investing adds private wealth as another selection mechanism for two reasons. First, most impact investing funds are—unlike many ESG funds—not open to the public and raise money from only a small number of investors, many of which are high net-worth individuals or family offices. A case in point here is the ‘Impact Investing for the Next Generation’ program of the World Economic Forum, which is restricted to young members of high net-worth families and has already brought together and trained more than 100 participants with regards to impact investing (World Economic Forum, Citation2014). Second, philanthropic foundations play a crucial role as capital providers, de-riskers, issue entrepreneurs and infrastructure providers for impact investing (Kumar & Brooks, Citation2021; McGoey, Citation2012). Key examples are the Sorenson Impact Center funded by American billionaire James Lee Sorenson, which runs the annual Social Capital Markets conference, and the philanthropic foundations of Bill and Melinda Gates, Hilde and Klaus Schwab, and eBay co-founder Pierre Omidyar, which are involved in virtually all aspects of maintaining and popularizing impact investing. This gives billionaires, especially from the US tech sector, ample voice in impact investing and can explain the popularity of ‘philanthrocapitalist’ discourse and venture-capital models in impact investing (McGoey, Citation2021).

By contrast, recipients of impact capital are usually excluded from the governance of impact investing and the design of impact metrics (Himmer, Citation2023; Neyland, Citation2018). This is particularly the case for investees in the Global South, whose voices are often crowded out or weakened compared to capital providers in the Global North (Ehrenstein & Neyland, Citation2018; Gabor & Brooks, Citation2017; Mader, Citation2015). Rather than empowering actors in the Global South, impact investing has been found to build on and reproduce colonial network structures (Bernards, Citation2021; Ducastel & Anseeuw, Citation2020). Ever since the SDGs defined private capital mobilization as a key goal for international development, impact investors have also strengthened their access to and network connections with national and multilateral development finance institutions (DFIs) (Kabouche, Citation2024). As the IFC describes, DFI representatives are now ‘rubbing shoulders’ with impact investors at conferences of the Global Impact Investing Network (IFC, Citation2019, p. 73). Rather than strengthening the voice of the Global South in international development, impact investing further strengthens the epistemic position of investors and wealthy individuals.

A similar pattern can be observed in Social Impact Bonds, where impact investors take the lead in the construction of metrics that trigger the payment of public funds earmarked for welfare spending. Here, impact investors gain access to arenas of social policymaking, often at the expense of other actors such as social and not-for-profit organizations (Joy & Shields, Citation2018; Neyland, Citation2018; Tse & Warner, Citation2020). Due to their vested interests, impact investors propose metrics that in some cases undermine the stated social policy objectives (Cooper et al., Citation2016; Neyland, Citation2018; Sinclair et al., Citation2021). In contrast to impact investors’ gerrymandered depiction of SIBs as success stories, SIBs have been found to negatively affect the quality of government interventions (Berndt & Wirth, Citation2018; Huckfield, Citation2020; Wirth, Citation2020).

Assetization of public policy

The epistemic ecology surrounding impact investing contributes to the assetization of green, social and developmental policies. This development builds on earlier phases of financialization in which policymakers began to see financial market growth ‘as an end on its own, underpinned by an understanding of the financial sector as an important driver for growth and development’ (Rethel, Citation2020, pp. 356-357). Assetization takes this one step further as it makes the production of profitable financial assets a primary policy goal. Derisking, understood as the use of direct and indirect subsidies to alter the risk-return profile of financial investments, is the key policy instrument to drive assetization (Gabor, Citation2023). This poses the important question of why policymakers who need to win electoral majorities use public funds to serve the interests of a small group of capital owners. Although answers to this question vary across countries and are well beyond the scope of this article, it is no coincidence that momentum for impact investing and derisking policies rose simultaneously following the global financial crisis.

There are two important ways in which impact investing contributes to the rise of derisking and assetization. First, the epistemic ecology surrounding impact investing creates a win-win discourse on assetization with considerable cohesiveness and clear policy orientation (Burnier et al., Citation2022; Wiggan, Citation2018). Impact investors claim that their investments are key to rapidly scaling impactful businesses and interventions and thus the achievement of desired public outcomes, creating the impression of derisking as a prudent and effective policy instrument (Golka, Citation2023). Epistemic gerrymandering helps to increase the credibility and salience of impact investing discourse. The ambiguity surrounding impact helps to increase the salience of impact investing as a policy solution as it allows impact investors to address various policy issues, ranging from climate to social and development policy, and sources of derisking, such as subsidies, tax credits, risk guarantees or public co-investments. For example, the G7 Impact Task Force (Citation2021, p. 6, 21) explicitly calls for governments to ‘break down silos’ between various policy arenas and to spend more money on derisking, where ‘at least as much recognition’ should be given for mobilized impact investments as for ‘every dollar’ invested from public institutions.

More broadly, impact investing supporters attempt to dissolve the boundary between private and public investments by claiming, like the US Impact Investing Alliance (Citation2020), that private investment can create ‘public good’. While claiming public benefits is a common strategy for mobilizing government support, impact investing stands out as it can leverage a whole epistemic ecology to lend credibility to such claims. As notions of impact are—through epistemic gerrymandering—tailored to investment portfolios, every single impact investment can serve as supportive evidence for that claim. Through epistemic gerrymandering, investors can support their claims through various data points and seemingly objective methodologies, such as impact metrics, external standards and certifications, or case studies. This is further aided by recursive recognition from a broad support coalition that includes think-tanks, charitable foundations, the World Economic Forum, as well as public organizations such as development banks (Broome & Seabrooke, Citation2020). Together, this deep epistemic ecology adds considerable credibility to the claim that derisking impact capital can serve as an efficient policy lever. As expressed by the G7 task force: ‘The potential of [derisking] instruments is evidenced by real examples that demonstrate how capital can be mobilised at scale through their application’ (Impact Task Force, Citation2021, p. 20).

Second, the relational structure of impact investing funds is geared, much more than that of ESG funds, towards assetization. As economic sociologists have argued, assetization rests on a disembedding of objects such as agricultural land from their initial claimants (such as smallholder farmers) and a reconfiguration according to capital owners’ interests of return extraction (Birch & Muniesa, Citation2020; Tellmann, Citation2022). Impact investing funds have both the interest in and the means to drive such assetization processes. As described in section 2, impact investing funds create direct control relations with a small number of investees, raise capital from only a few capital owners, and use organizational templates and fee structures borrowed from the private equity industry that create strong material incentives to achieve high returns on equity. This means that impact investing funds extend the material interests of asset owners into frontier markets, particularly in the Global South. By contrast, this is much less the case for ESG funds of large, diversified asset managers, which have a much more complex relational structure and use fee models that make them more concerned with sustaining asset values than with returns on equity (Braun, Citation2022).

Although the rise of impact investing is certainly not the only reason for the recent turn to derisking (Gabor, Citation2023), and despite a growing anti-ESG backlash in the US, policymakers across the globe have embraced derisking impact investing. In the US, the White House stressed the need to ‘mobilize private finance’ as President Biden met with leading impact investors.Footnote6 Impact investors also ‘applauded’ the creation of a $20 billion grant scheme explicitly aimed at mobilizing private finance as part of Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act (Impact Investor, Citation2022). This complements various existing derisking policies such as state-level tax benefits for investments in community development financial institutions (CDFIs), or for investments under the Opportunity Zones scheme (including investments into golf courses) devised by the Trump administration. Although these schemes are not limited to impact investors, they are nevertheless seen as derisking opportunities by impact investors.Footnote7 In the UK, derisking policies for impact investing include two programs of tax relief, direct subsidies, co-investments, and legislation that total over £1 billion (Golka, Citation2019). In Europe, various off-balance sheet fiscal agencies are using derisking strategies to mobilize private finance for the green transition (Guter-Sandu et al., Citation2023). Finally, derisking strategies have also been common in international development, where DFIs, multilateral development banks, as well as national and transnational development institutions are increasingly using public or concessional funds to de-risk impact investments, including microfinance (Gabor, Citation2020; Mader, Citation2015; Mawdsley, Citation2018).

Conclusion

The ascendancy of finance in global governance comes with important transformations in the realm of ideas. The transformation of policymakers’ perceptions of financial markets from financiers to motors of economic growth has been particularly consequential (Rethel, Citation2020). Political economists are beginning to trace these ideational transformations to changes in knowledge production, focusing on the epistemic and positional strategies of financial actors (Golka & van der Zwan, Citation2022; Seabrooke, Citation2014; Seabrooke & Stenström, Citation2023). Financial actors’ increased knowledge production on issues such as sustainability has corresponded to a rise in private authority as standards and rules affecting the financial sector are increasingly produced by the financial sector itself (Petry et al., Citation2021). It has also had an effect on the knowledge available to policymakers as epistemic communities centered around scientific and policy experts (Haas, Citation1992) have seen some hybridization through the participation of financial actors and professionals with financial sector backgrounds (Broome & Seabrooke, Citation2020; Seabrooke & Tsingou, Citation2021).

Despite their importance, these findings neglect important differences within the financial sector. The issue of sustainability is a case in point, reflecting key differences between large (‘mainstream’) ESG investors and private (‘alternative’) impact investors. Whereas ESG investors hold minority shares in many listed enterprises, influence corporations mainly through voting, and play only a subordinate role in company financing (Braun, Citation2022), impact investors are often majority owners of only a few early-stage companies, assume board seats and provide significant corporate financing. In ESG investing, metrics and numbers are mainly produced for consumption within the financial sector. This ‘governance through ESG’ gives index providers considerable authority and significantly affects capital allocation (Fichtner et al., Citation2023). In impact investing, metrics and numbers play a strikingly different role. As impact metrics are often gerrymandered around impact funds’ financial portfolios, their role in capital allocation is—as evidenced by ethnographic studies (Bourgeron, Citation2020; Hellman, Citation2020; Himmer, Citation2023)—often negligible.

What, then, are impact numbers good for? As argued throughout this article, they help investors affirm their position as impact investors vis-à-vis peers and capital providers. But they also help create a knowledge regime affecting public and policymakers’ perceptions. At the heart of impact investing is an attempt to dissolve institutional boundaries, notably between the private and the public sphere (Dowling & Harvie, Citation2014; McGoey, Citation2021). Notions of impact and their quantified expressions primarily serve as evidence for impact investors’ claim that, across policy issues, private finance can create ‘public good’ (US Impact Investing Alliance, Citation2020). Recursive recognition among a broad coalition of impact investing supporters increases the credibility of these claims, aiding their acceptance among policymakers.

As the notion of epistemic gerrymandering entails, however, investors’ depictions of impact are not neutral. At its core, impact is a tool to invisibilize ‘uncomfortable knowledge’ (Rayner, Citation2012), that is, notions of societal impact that are at odds with asset owners’ wealth and impact investors’ high return expectations, such as wages and progressive taxation (Golka, Citation2023). While invisibility has long been key to safeguarding the durability of private fortunes (Beckert, Citation2022; Harrington, Citation2021), impact investing represents an important strategy shift. Rather than hiding capitalist wealth reproduction and putting philanthropic activities into public display, impact investing creates strategic visibility to the perpetuation of private wealth through for-profit financial investments. But as this article has shown, the pursuit of impact should not be conflated with increased accountability. Impact is a device of ‘strategic ignorance’: a regime of knowledge production that allows the wealthy to ‘conceal information while appearing transparent’ (McGoey, Citation2012, p. 4). My argument is that transnational clubs of ‘alternative’ investors allow such a knowledge regime to emerge and expand.

This article opens up various questions for future research. Most importantly, future research should address the key limitation of my theory-building research design and investigate whether and under what conditions impact investors resort to forms of knowledge production other than epistemic gerrymandering. Another important question is how recent dynamics within finance affect epistemic gerrymandering. As epitomized by BlackRock’s recent acquisition of Global Infrastructure Partners, large asset managers and institutional investors are increasingly moving into alternative, non-listed assets (Financial Times, Citation2024). Future research could thus investigate how this amalgamation between ‘mainstream’ and ‘alternative’ finance affects knowledge regimes in the financial governance of sustainability.

Finally, more research is needed regarding the reach of epistemic gerrymandering. This not only includes assessing whether epistemic gerrymandering can also be observed beyond ‘alternative’ finance. Future research should also investigate the conditions under which financial actors do and do not succeed with their ideational work. Although policymakers across the globe praise private finance as a solution to the climate crisis, the introduction of impact investing into social welfare has remained far below expectations even in highly financialized countries such as the UK (Maron & Williams, Citation2023). As financialization entrenches economic and participatory inequalities, failed financial projects carry emancipatory potential. The question is whether these financial failures are politicized before they are gerrymandered out of existence.

Acknowledgments

For very helpful comments on various versions of this manuscript, I would like to thank Sharon Adams, Théo Bourgeron, Benjamin Braun, Julian Jürgenmeyer, Natascha van der Zwan, as well as members of the political economy group at Leiden University, members of the economic sociology group at the Max Planck Institute, Cologne, and participants of the 2022 Finance and Society Conference in London. I would also like to acknowledge very insightful and constructive feedback from the editors of RIPE and three anonymous reviewers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Philipp Golka

Philipp Golka is a Senior Researcher at the Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies, Cologne. His research is located at the intersection of economic sociology and political economy scholarship and focuses on financial markets, private wealth, and climate.

Notes

1 See https://gsgii.org, accessed March 2024.

2 See https://acumencapitalpartners.com/#funds, accessed February 2024.

3 See https://blueorchard.com/impactreport/, accessed February 2024.

4 See https://bcorporation.net/certification for details, accessed 16 May 2021.

5 See for example Financial Times, 9 April 2021, https://www.ft.com/content/2d96502f-c34d-4150-aa36-9dc16ffdcad2.

6 White House Press Release, 10 July 2023, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/07/10/joint-fact-sheet-president-biden-and-his-majesty-king-charles-iii-meet-with-leading-philanthropists-and-financiers-to-catalyze-climate-finance/.

7 On Opportunity Zones, see Mission Investors Exchange: https://missioninvestors.org/resources/opportunity-zones-fundamentals, on CDFIs, see Forbes: https://www.forbes.com/sites/brianthompson1/2021/01/31/impact-investing-through-community-development-financial-institutions-cdfis/?sh=20fc6a9a7b75.

References

- Acumen. (2023). Annual report. https://acumen.org/2022-annual-report/

- Al Dahdah, M. (2019). From evidence-based to market-based mHealth: Itinerary of a mobile (for) development project. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 44(6), 1048–1067. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243918824657

- Baines, J., & Hager, S. B. (2022). From passive owners to planet savers? Asset managers, carbon majors and the limits of sustainable finance. Competition & Change, 27(3-4), 449–471. https://doi.org/10.1177/10245294221130432

- Ban, C., Seabrooke, L., & Freitas, S. (2016). Grey matter in shadow banking: International organizations and expert strategies in global financial governance. Review of International Political Economy, 23(6), 1001–1033. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2016.1235599

- Barman, E. (2015). Of principle and principal: Value plurality in the market of impact investing. Valuation Studies, 3(1), 9–44. https://doi.org/10.3384/VS.2001-5592.15319

- Barman, E. (2020). Many a slip: The challenge of impact as a boundary object in social finance. Historical Social Research/Historische Sozialforschung, 45(3), 31–52.

- Beckert, J. (2022). Durable wealth: Institutions, mechanisms, and practices of wealth perpetuation. Annual Reviews of Sociology, 48(6), 1–23.

- Benquet, M., & Bourgeron, T. (2022). Alt-finance: How the city of London bought democracy. Pluto Press.

- Bernards, N. (2021). Poverty finance and the durable contradictions of colonial capitalism: Placing ‘financial inclusion’ in the long run in Ghana. Geoforum, 123, 89–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.04.029

- Berndt, C., & Wirth, M. (2018). Market, metrics, morals: The Social Impact Bond as an emerging social policy instrument. Geoforum, 90, 27–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.01.019

- Berry, C., Rademacher, I., & Watson, M. (2022). Introduction to the special section on Financialization, state action and the contested policy practices of neoliberalization. Competition & Change, 26(2), 215–219. https://doi.org/10.1177/10245294221086864

- Beyster, M. A. (2017). Impact investing and employee ownership. Democracy Collaborative.

- Birch, K., & Muniesa, F. (Eds.) (2020). Assetization: Turning Things into Assets in Technoscientific Capitalism. Cambridge, MA & London MIT Press.

- Bishop, M., & Green, M. (2008). Philanthrocapitalism: How the Rich Can Save the World. Bloomsbury Press.

- Bloomberg. (2022). ESG may surpass $41 Trillion Assets in 2022. Press announcement. Available at: https://www.bloomberg.com/company/press/esg-may-surpass-41-trillion-assets-in-2022-but-not-without-challenges-finds-bloomberg-intelligence/

- Bourgeron, T. (2020). Constructing the double circulation of capital and ‘social impact.’ An ethnographic study of a French impact investment fund. Historical Social Research/Historische Sozialforschung, 45(3), 117–139.

- Boussard, V. (2018). Professional closure regimes in the global age: The boundary work of professional services specializing in mergers and acquisitions. Journal of Professions and Organization, 5(3), 279–296. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpo/joy013

- Braun, B. (2022). Exit, control, and politics: Structural power and corporate governance under asset manager capitalism. Politics & Society, 50(4), 630–654. https://doi.org/10.1177/00323292221126262

- Braun, B., Gabor, D., & Hübner, M. (2018). Governing through financial markets: Towards a critical political economy of Capital Markets Union. Competition & Change, 22(2), 101–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/1024529418759476

- Bridges Fund Management . (2023). Annual report 2022-2023. https://www.bridgesfundmanagement.com/publications/bridges-annual-report-2022-23/

- Broom, J., & Tchilingirian, J. (2022). Networks of knowledge production and mobility in the world of social impact bonds. New Political Economy, 27(6), 1031–1045. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2022.2054965

- Broome, A., & Seabrooke, L. (2020). Recursive recognition in the international political economy. Review of International Political Economy, 28(2), 369–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2020.1830827

- Builders Fund. (2020). 2020 impact report. https://www.thebuildersfund.com/buildersfund-impactreport-2020-F-DIGITAL.pdf

- Burnier, D., Balsiger, P., & Kabouche, N. (2022). Portraying finance as a ‘force for good’: A discourse analysis of the Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN). Natures Sciences Sociétés, 30(3-4), 226–237. https://doi.org/10.1051/nss/2023004

- Carter, E. (2021). More than marketised? Exploring the governance and accountability mechanisms at play in Social Impact Bonds. Journal of Economic Policy Reform, 24(1), 78–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/17487870.2019.1575736

- Chiapello, E. (2015). Financialisation of valuation. Human Studies, 38(1), 13–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10746-014-9337-x

- Chiapello, E., & Godefroy, G. (2017). The dual function of judgment devices. Why does the plurality of market classifications matter? Historical Social Research, 42(1), 152–188.

- Chiapello, E., Knoll, L., & Warner, E. (2020). Special issue: Social Impact Bonds and the urban transformation. Journal of Urban Affairs, 42(6), 815–815. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2020.1805240

- Collins, J. L., & Kahn, W. N. (2016). The hijacking of a new corporate form? Benefit corporations and corporate personhood. Economy and Society, 45(3-4), 325–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147.2016.1239342

- Cooiman, F. (2021). Veni vidi VC–The backend of the digital economy and its political making. Review of International Political Economy, 30(1), 229–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2021.1972433

- Cooper, C., Graham, C., & Himick, D. (2016). Social impact bonds: The securitization of the homeless. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 55, 63–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2016.10.003

- Dowling, E. (2017). In the wake of austerity: Social impact bonds and the financialisation of the welfare state in Britain. New Political Economy, 22(3), 294–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2017.1232709

- Dowling, E., & Harvie, D. (2014). Harnessing the social: State, crisis and (big) society. Sociology, 48(5), 869–886. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038514539060

- Ducastel, A., & Anseeuw, W. (2020). Impact investing in South Africa. Historical Social Research/Historische Sozialforschung, 45(3), 53–73.

- Ebbinghaus, B. (2011). The varieties of pension governance: Pension privatization in Europe. Oxford University Press.

- Ehrenstein, V., & Neyland, D. (2018). On scale work: Evidential practices and global health interventions. Economy and Society, 47(1), 59–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147.2018.1432154

- Emerson, J. (2003). The blended value proposition: Integrating social and financial returns. California Management Review, 45(4), 35–51. https://doi.org/10.2307/41166187

- Emerson, J., & Bugg-Levine, A. (2011). Impact investing: Transforming how we make money while making a difference. Jossey-Bass

- European Union. (2013). Regulation (Eu) No 346/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 April 2013 on European social entrepreneurship funds. Official Journal of the European Union, L115, 18–38.

- Faul, M. V., & Tchilingirian, J. S. (2021). Structuring the interstitial space of global financing partnerships for sustainable development: A network analysis. New Political Economy, 26(5), 765–782. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2020.1849082

- Fichtner, J., Jaspert, R., & Petry, J. (2023). Mind the ESG gaps: Transmission mechanisms and the governance of and by sustainable finance. DIIS Working Paper, 2023, 04.

- Financial Times. (2024). BlackRock to buy global infrastructure partners for $12.5 bn. https://www.ft.com/content/a0901489-6caa-42b8-ac55-1a09e64ef927

- Fraser, A., Tan, S., Lagarde, M., & Mays, N. (2018). Narratives of promise, narratives of caution: A review of the literature on Social Impact Bonds. Social Policy & Administration, 52(1), 4–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12260

- Freireich, J., & Fulton, K. (2009). Investing for social and environmental impact: A design for catalyzing an emerging industry. Monitor Institute, 1–86.

- Gabor, D. (2020). The Wall Street consensus. Development and Change, 52(3), 429–459. dech.12645. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12645

- Gabor, D. (2023). The (European) derisking state. SocArXiv Papers. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/hpbj2

- Gabor, D., & Brooks, S. (2017). The digital revolution in financial inclusion: International development in the fintech era. New Political Economy, 22(4), 423–436. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2017.1259298

- G8. (2014). Impact investing: The invisible heart of markets. https://gsgii.org/reports/impact-investment-the-invisible-heart-of-markets/

- GIIN. (2013). Perspectives on progress. http://www.thegiin.org/cgi-bin/iowa/resources/research/489.html

- GIIN. (2019). Sizing the impact investing market. https://thegiin.org/research/publication/impinv-market-size

- GIIN. (2020a). 2020 annual impact investor survey. https://thegiin.org/research/publication/impinv-survey-2020

- GIIN. (2020b). The state of impact measurement and management practice, Second Edition. https://thegiin.org/research/publication/imm-survey-second-edition

- Golka, P. (2019). Financialization as Welfare: Social impact investing and British Social Policy, 1997–2016. Springer.

- Golka, P. (2023). The allure of finance: Social impact investing and the challenges of assetization in financialized capitalism. Economy and Society, 52(1), 62–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147.2023.2151221

- Golka, P., & van der Zwan, N. (2022). Experts versus representatives? Financialised valuation and institutional change in financial governance. New Political Economy, 27(6), 1017–1030. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2022.2045927