ABSTRACT

Commercial awareness is a graduate employability skill that is highly valued by law firms, particularly the larger commercial law firms that dominate recruitment into the legal profession. However, it is a skill that students may struggle to understand and to demonstrate during the graduate recruitment process. This article examines the role of commercial awareness at a crucial point in the law student journey into the legal profession – the law firm graduate interview. This article presents data collected from an innovative two year mixed-methods research study involving law students at a post-92 university who were undergoing interviews with law firms. It provides insight into the “lived experience” of the law firm interview from a student perspective by considering how and when commercial awareness is assessed and the challenges and opportunities assessment presents. This study furthers our limited understanding of how law students define commercial awareness, comparing those definitions to those employed by the legal profession and considering the disconnect between students and law firms. This article argues that, in the context of commercial awareness, there is more that law firms and law schools can do to better support law students seeking employment in the legal profession.

Introduction

The increasing number of students graduating from law degrees and postgraduate law programmes provides law firms with significant choice when recruiting new entrants to the legal profession. In 2021 alone, 18,927 students graduated from a first degree in law, a rise of 18.7% since 2016 (The Law Society, Citation2022, p. 41). There were 5,495 available training contracts, a 2.3% decrease in number from the previous year (The Law Society, Citation2022, p. 44). Whilst not all law students seek to enter the legal profession,Footnote1 those that do aspire to become solicitors face a highly competitive recruitment environment where employers demand a range of skills and competencies. Commercial awareness, the ability to understand the business world and how it operates, has become more important to the legal profession as it becomes ever more commercialised (Hanlon, Citation1999; Strevens et al., Citation2011; Sommerlad, Citation2011). Many larger commercial law firms are explicit in requiring commercial awareness from prospective employees (Thomas, Citation2018;Footnote2 Websites, Citation2023). Such firms dominate recruitment to the legal profession. In 2021 over 50% of training contract positions in England and Wales were in law firms with 26 or more partners (The Law Society, Citation2022, p. 44), perhaps confirming their status as “the training ground for the profession” (Hanlon, Citation1997, p. 805). This article considers the perspectives of law students in a post-92Footnote3 university on the role of commercial awareness in obtaining graduate employment in the legal profession. This article explores how these law students defined commercial awareness, how important it was to them and how they experienced the assessment of commercial awareness during law firm graduate interviews.

The commercial awareness rhetoric adopted by many law firms poses challenges for students seeking to access graduate employment in the legal sector. Whilst employability skills like teamwork and communication are perhaps easy for students to conceptualise and demonstrate during the recruitment process, commercial awareness is more problematic. The first difficulty is that there is a lack of clarity over what commercial awareness means. Commercial awareness has been considered an “amorphous term” with employers and students defining it in various, sometimes contrasting, ways (Wilkinson & Aspinall, Citation2007, p.5). As the literature review section of this article will demonstrate, there is limited empirical research on how law students define commercial awareness and how their understandings compare with those of the legal profession. The second challenge for students is that evidence from across the broader graduate recruitment spectrum suggests that students lack commercial awareness and that they may struggle to demonstrate it at interview (Wilkinson & Aspinall, Citation2007; Institute of Student Employers (ISE), Citation2022, p. 25). Recruitment within the legal profession differs to most other graduate sectors because many of the largest employers of trainee solicitors recruit two years in advance. This means that during the graduate recruitment process, students who are fairly early on in their undergraduate lives (as second and sometimes first year students), are expected to understand and demonstrate commercial awareness – an ambiguous and complex skill. Finally, although studies by Sommerlad (Citation2011) and Etherington (Citation2016) found that commercial awareness was assessed by law firms during the graduate recruitment process, there is no data on either how law firms assess commercial awareness or how law students experience its assessment during law firm interviews. Overall, there are some significant gaps in our understanding of the role of commercial awareness at a critical stage in the law student journey into the legal profession.

This article presents the findings of a small-scale two year mixed-methods research study involving 31 law students in a post-92 university law school applying for a range of positions in a variety of law firms. Drawing on data from 31 completed questionnaires and 20 semi-structured interviews, this study sought to answer the following research questions:

how do law students define commercial awareness?

how important is commercial awareness to law students seeking to join the legal profession?

how do law students experience the assessment of commercial awareness in law firm interviews?

This research study is timely because its findings arrive at a point of some critical changes to the way students access employment in law firms. Firstly, the route to qualification as a solicitor is changing. The Legal Practice Course (LPC), the one year postgraduate qualification required to become a solicitor, is ending and being replaced by the Solicitors Qualifying Examinations (SQE), a set of centralised examinations graduates must pass to qualify as solicitors. Although the Legal Education and Training Review (LETR, Citation2013) recommended that commercial awareness should be an explicit aspect of the LPC, the SQE assessment specifications make no mention of it. Despite this, commercial awareness will still be critical to law students. Many larger commercial law firms recruit two years in advance, meaning that the firms most likely to demand commercial awareness will expect students to demonstrate it well before they complete either the SQE or the LPC.Footnote4 Such firms will undoubtedly continue to recruit future trainees two years in advance to secure the most desirable candidates from an ever increasing talent pool. However, commercial awareness is not solely the preserve of these early recruiters and may be required by firms recruiting later on. Further, many paralegals will seek to qualify as solicitors under the SQE regime, provided they have two years’ work experience and have passed the SQE. Although the training contract barrier to qualification will disappear, employers will require paralegals to be commercially aware. Secondly, the commitment of a growing number of law firms to social mobility and the Levelling Up agenda means that parts of the profession that have traditionally not targeted students from non-Russell Group law schools like the author’s (Ashley & Empson, Citation2013; Ashdown, Citation2015; The Law Society, Citation2020; The Bridge Group, Citation2017) are seeking to redress that imbalance in their recruitment practices.Footnote5 It is critical to understand how such students experience commercial awareness within the “arena” of the graduate recruitment process (Tomlinson, Citation2021, p. 140) so that both law firms and law schools gain some insight into the particular challenges these students face.

This article begins by examining the current literature on commercial awareness in the context of the research questions before outlining the research study method and data analysis. The findings show that the law students in this study defined commercial awareness in multiple ways. Students who were more familiar with the legal profession and the graduate recruitment process shared some of the profession’s main understandings of commercial awareness. However, there was a contrast between student and law firm definitions that suggested that the law students in this study were not fully cognisant of the more sophisticated meanings of commercial awareness adopted by law firms. The law students in this study perceived commercial awareness to be a very important skill that is required by a variety of firm types to access employment. Reflecting this viewpoint, most of the students expected commercial awareness would be assessed by law firms at interview. However, for these students, assessment was not guaranteed; there was a gap between student expectations and their graduate interview experience. This article helps in furthering our understanding of how commercial awareness is assessed by law firms and provides unique insight into the challenges and opportunities that assessment presents to law students. Although this study draws on the findings of a sample from a single institution, this study makes an original contribution to knowledge by finding that, even where commercial awareness was not assessed at interview, many students sought to demonstrate it anyway, in order to meet perceived law firm requirements. Overall, the findings suggest that the commercial awareness narrative pushed by leading law firms (and promoted by other stakeholders with an interest in supporting students into the legal profession) heavily influenced the law students in this study who were seeking work in law firms, irrespective of firm type and role applied for.

Although the sample size for this study was small (the issues surrounding this are explored further in the Method section), it is hoped that both law firms and law schools will benefit from the discussion within this article. Whilst this article focuses on commercial awareness as it relates to law students applying to law firms in England and Wales, it is anticipated that the findings will be of interest to an international audience because many law firms with bases in England and Wales operate in a multinational setting, recruiting students from around the world, seeking similar skills from prospective employees.Footnote6 From a legal education perspective, although this article does not seek to consider how law schools might support students in developing their commercial awareness,Footnote7 it should provide law schools with useful insight into student perceptions of when and how commercial awareness is assessed during the graduate interview. This may enable law schools to better support their students when preparing for interview. This is critical because interviews remain the most common method of selection by graduate employers (ISE, Citation2021, p. 49). More generally, the insight gained from this study may support the focus on the broader employability agenda that is now so important to law schools (Nicholson, Citation2021). The revised subject benchmark statement for law notes the need for law students to develop employability skills during their studies (QAA, Citation2023, p. 11). The focus on employability will no doubt increase given the growing emphasis on employment outcomes and their related impact on university league tables and the Teaching Excellence Framework (Citation2022).

Existing literature on definitions, importance and assessment

What does commercial awareness mean?

There is no agreed definition of commercial awareness and, as noted, it may have different meanings to different stakeholders. The definition of commercial awareness used by the LETR (Citation2013) was based on careers advisers’, rather than law firms’, views. This definition was extensive and included financial literacy, legal practice management and understanding that law firms are businesses. It also encompassed understanding clients’ businesses and sectors and commercial (rather than purely legal) objectives (LETR, paras. 2.75 and 7.2). The academic literature concerning the definition of commercial awareness is fairly limited and focuses on understanding that a law firm is a business (Huxley Binns, Citation2011; Strevens et al., Citation2011). In their study of law firms, Strevens et al (Citation2011) also suggested that, for lawyers, commercial awareness meant understanding the “wider picture than the black letter law applied to a given set of facts” (p. 341). Following a systematic literature review of commercial awareness in the context of law students seeking employment in the legal sector, the author (Citation2022(a)) suggested that, in a legal setting, commercial awareness has multiple components and includes understanding: (1) law firms, their clients and the sectors in which they operate; (2) how external influences (political, social, economic and technological) impact on law firms, clients and their respective sectors and the advice law firms provide; (3) that the legal rights and remedies of clients may not always best suit their objectives; and (4) that a law firm is a business – lawyers need to make money to stay in business.

There is limited empirical evidence of how law students define commercial awareness. Turner et al (Citation2018) noted the comment of one student who stated that commercial awareness encompassed understanding changing legal markets and areas of law. A study involving law students working in a university law clinic (McConnell, Citation2022(b)) found that participants lacked confidence in defining commercial awareness and definitions focused on current affairs and business knowledge. There was little discussion of the “law firm as a business” aspect of commercial awareness. Overall, there is little published data on how law students define commercial awareness despite, as will now be argued, its perceived importance to law firms and, by extension, law students seeking to join those firms.

How important is commercial awareness to law firms?

The LETR (Citation2013) acknowledged the importance of commercial awareness to the profession, finding 68.9% of respondent practitioners indicating that knowledge of the business context of law was important/very important to their work (para. 2.74)Footnote8 and concluding that there was a commercial awareness knowledge and skills gap within the profession (para. 2.173). Law firm websites suggest that having commercial awareness is important to firms in their marketing to clients.Footnote9 This is often part of a broader emphasis on a law firm’s commerciality and ability to work with clients as business, rather than purely legal, advisers.Footnote10 The concept of commercial awareness is also frequently referenced where law firms specify what they are looking for in recruits (Thomas, Citation2018; Websites, Citation2023). For example, Shoosmiths note it is “essential to your legal career”Footnote11 whilst for Norton Rose Fulbright it is “what we look for”.Footnote12 CMS emphasises that commercial awareness is required in order to advise clients effectively and to add value to the lawyer-client relationship. This all adds to the discourse of the drive within the profession for candidates with the “necessary skills … to be practice-ready profit-makers” (Nicolson, Citation2015, p. 53.) Such evidence leads naturally to a consideration of why commercial awareness is so important to law firms.

It is clear that commercial awareness has increased in importance to law firms over the last 40 years. Law is, in itself, “big business”. UK law firms are operating in a highly competitive and lucrative sector that in 2021 produced a revenue of around 32 billion pounds (Statista, Citation2023a). In 2021 the most successful five UK law firms alone had a revenue of over 9.3 billion pounds (Statista, Citation2023b). It is estimated that the legal sector employs the equivalent of 358,000 full time employees (KPMG, Citation2020, p. 7). Given the value of the legal sector and the numbers working within it, law firms have necessarily become more business-orientated and focused on “the practice of law as a business” (Moorhead & Hinchly, Citation2015, p. 388). Senior lawyers need to be cognisant of which areas of practice to focus on, legal recruitment, costing legal services and profitability (Bowley, Citation2020). Those entering practice benefit from being commercially aware.

There are other critical reasons for the emphasis on commercial awareness within the legal sector, for example, changes in regulation, marketing and competition. Perhaps the most significant change within the profession that has led to a concentrated focus on commercial awareness is the transformation in the lawyer-client relationship; clients, particularly those using large commercial law firms, have become more powerful. Clients expect lawyers to be business as well as legal advisers and law firms promote their legal services on that basis (Hanlon, Citation1997). Clients both demand and expect commercial awareness from their lawyers. The academic literature documents the rise in client power and the change in the lawyer-client relationship that began in larger commercial law firms. Client surveys from the 1980s (Brown & McGirk, Citation1982; Blackhurst & Stokes, Citation1985) noted how important it was for corporate clients that their City legal advisers provided commercially aware lawyers. Further insight comes from Stratton (Citation1992) who, in a survey of 100 clients, found that one of the key problems clients noted with their law firms was a lack of commercial awareness in their lawyers. Hanlon and Jackson (Citation1999) found that clients wanted commercially aware lawyers or they would use other firms. Clients, particularly commercial clients, began to expect more from their lawyers. Lawyers were working in a service industry that required knowledge not only of the law but of what clients think and do, prioritising commerciality and customer service (Sommerlad, Citation2011). More recently, Oakley and Vaughan observed the move of the corporate lawyer from “trusted advisor” to “hired hand” (Citation2019, p. 97) finding evidence of “patronage professionalism” where important clients controlled the lawyer-client relationship and how legal work was carried out.

Although commercial awareness has been seen as an “inescapable shibboleth” for those seeking to practise corporate law (Dunne, Citation2021, p. 294), it would be simplistic to suggest that commercial awareness is needed only by those practising in commercial law firms. Given the definitions of commercial awareness discussed earlier, arguably all firms require commercially aware lawyers. In an early study of residential conveyancing firms, Paterson et al (Citation1988) argued that the commercial awareness of a firm was likely to influence its response to competition in the conveyancing market. “Strategists” – lawyers who perceived themselves to be running a business – were the most commercially aware, indicative, the authors argued, of how the profession was changing. In their study of nine varying types of law firm, Strevens et al (Citation2011) argued that commercial awareness was required across the legal sector. Similarly, studies by Williams et al (Citation2019) and Nicholson (Citation2022) have found commercial awareness important to a range of legal sector employers. Overall, it appears that many law firms demand commercial awareness from existing and future employees. As noted, the larger commercial firms recruit and train most of the lawyers in England and Wales. These firms are critical in setting professional expectations that other firms seek to emulate. The influence of these firms, directly through their business positioning as legal and business advisers, and indirectly, as their lawyers take their training and mantra to other firms, has arguably filtered across the profession. Their influence is further compounded by third party websites that support students into the profession, for example, Lawyer2B, LawCareers.Net and Aspiring Solicitors,Footnote13 that emphasise the importance of commercial awareness across the profession.

How and when is commercial awareness assessed by law firms?

Although studies have confirmed that commercial awareness is assessed during the graduate recruitment process (Sommerlad, Citation2011; Etherington, Citation2016; Mitchard, Citation2022), none provides explicit detail on how assessment takes place from either an employer or student perspective. Etherington’s study involved six differing types of law firm and 28 students, finding that all but one firm assessed commercial awareness with 89% of students stating it had been assessed. However, there was no detail provided by either group on how it was assessed. In Sommerlad’s study (Citation2011) of corporate law firms, participant employers stated that commercial awareness was assessed in interviews and assessment centres but again there was no detail on how assessment occurred. A recent study by Mitchard (Citation2022) asked legal employers in Hong Kong (including some Magic Circle firms) about the skills needed for practice and to perform well at interview. There was a clear demand for commerciality amongst participant employers; it was required for “good interview performance” (Citation2022, p. 12). Knowledge of how law firms operate as businesses was deemed beneficial by nearly all of the participants.

Law firm websites provide insight into whether commercial awareness is assessed during the graduate interview process. For example, Macfarlanes is explicit in stating that it is tested at interview whilst Gateley plc states that prospective trainees will hear the phrase “over and over during training contract applications and interviews”.Footnote14 CMS states commercial awareness is likely to be tested at interview, even providing a suggested question and answer guide and tips on how to develop commercial awareness.Footnote15 Linklaters advises students coming to interview to pick business or legal stories that interest them so that they can demonstrate their commercial awareness.Footnote16

The data analysis in this article seeks to provide further insight into how law students define commercial awareness, its importance to them and how it is assessed in a law firm graduate interview.

Method

This article considers data collected from a mixed-methods research study involving students undergoing law firm graduate interviews.Footnote17 Participants were drawn from students involved in a practice interview scheme organised by the author in the law school at Northumbria University, a post-92 university. The practice interview scheme offers students an opportunity to experience a simulated interview before a graduate interview. Ethics approval was obtained prior to the start of the data collection and all of the participants provided informed consent to their participation in the study.

Data was collected between February 2019 and July 2021. There were 31 participants (20 female, 11 male) aged between 20 and 33 years old. Participants were in the following years of study: Year 2 (two participants), Year 3 (three participants), Year 4 (19 participants) and LPC (seven participants). The roles applied for included vacation schemes (six participants); dual vacation scheme/training contract pathways (three participants), training contracts (11 participants) and paralegal roles (11 participants). Quantitative data was collected using a pre-practice interview questionnaire. All 31 participants completed this, providing details of their prospective legal employer, role and previous interview experience. Participants also selected the skills they hoped to demonstrate in the practice interview from a pre-selected list.Footnote18 After their graduate interview, participants were invited to attend a semi-structured interview with the author where they discussed their law firm interview experience and their views on commercial awareness. Twenty participants returned for a semi-structured interview. The interviews were audio-recorded and professionally transcribed. The interview transcripts were coded and thematically analysed (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006, Citation2021) using NVivo software. An inductive approach was taken to the thematic analysis where codes and themes were developed from the data in the transcripts (Braun & Clarke, Citation2021). The interviews produced a significant amount of qualitative data but this article focuses on the data relating to commercial awareness in the context of the research questions outlined earlier.

The sample – strengths and limitations

There are recognised limitations to this study. Firstly, for the purposes of the quantitative data, the sample size of 31 participants is small. For this reason the quantitative data is used to support and provide further insight into the key themes produced by the qualitative data, particularly around the perceived importance of commercial awareness to the legal profession and those seeking access to it. Secondly, most participants were undergraduates from one institution in north east EnglandFootnote19 and so their experiences may not be generalisable to all law students. Despite these limitations, it is arguable that other features of this study help to counter these drawbacks. Firstly, in relation to the qualitative data, the number of semi-structured interviews (20) was above the average required to see data saturation for one institution (Guest et al., Citation2006; Brett & Wheeler, Citation2022). Secondly, the author is not aware of any other law school that is running a practice interview scheme and collecting data on how law students experience law firm graduate interviews. As such, the qualitative data provides some unique insight into how students experience the assessment of commercial awareness during law firm interviews. Further, the findings from a sample drawn from a post-92 law school, with a high number of students from low socio-economic backgrounds, present valuable information for both law schools and law firms on the role commercial awareness plays at a key point of access to the profession. Although the author did not collect data relating to the social background of the participants, over 40% of undergraduates at Northumbria University are from widening participation backgrounds.Footnote20 In 2020/21, 93.7% of undergraduate students at Northumbria University were from state schools or colleges (above the UK average of 90.3%) with 18.4% from low participation neighbourhoods (above the UK average of 12.1%) (HESA, Citation2023). As parts of the profession seek to “Level Up” and recruit more students from institutions like the author’s, it is important to understand the experience of students from those institutions at this critical point in their journey into the legal profession. It would be desirable, however, to replicate the study with students from other institutions to gather more data across different regions to provide further insight into the issues this study explored.

This article now considers the quantitative data from the questionnaires and the rich qualitative data arising from the discussions with the 20 participants who returned after their graduate interview. It focuses on the key themes that were developed from the data that related to the research questions. These themes were:

the match and mis-match in understanding what commercial awareness means;

the pervasive influence of law firms regarding the importance of commercial awareness; and

the lived experience of the graduate interview.

Findings and discussion

Theme 1 – the match and mismatch in understanding what commercial awareness means

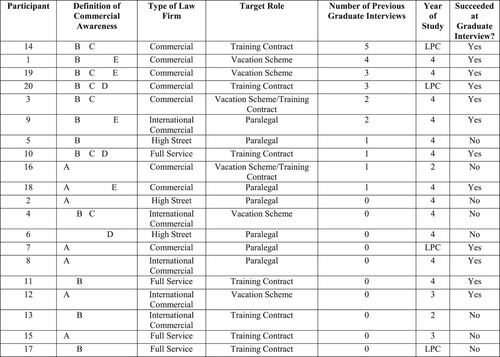

contains key data on the 20 participants (12 female, 8 male) who completed the questionnaire and attended a semi-structured interview. During the semi-structured interview, these participants were asked to provide a definition of commercial awareness. This study was exploratory in nature and did not seek to test whether the participant definitions mapped on to the author’s suggested definition of commercial awareness noted earlier. However, the findings do consider which aspects of the definition participants mentioned.

All of the participants could provide a definition of commercial awareness but definitions varied and some participants were more confident in defining commercial awareness than others. The data analysis allowed for the definitions to be categorised into five definition types (). These were:

Definition A – understanding current affairs/business issues

Definition B – understanding current affairs and impact on clients and/or law firms

Definition C – understanding current affairs/business issues and impact on advice to clients

Definition D – the legal solution isn’t always the right solution

Definition E – the law firm is a business.

As indicates, some participants adopted a single definition whilst others adopted a more multi-faceted approach. Those who adopted a more expansive, multi-layered definition had usually already experienced multiple graduate interviews with law firms. Most participants providing a single definition had no such previous experience.

Definition A (understanding current affairs/business issues) was the most simplistic definition adopted as a singular definition by six participants, five of whom had no prior graduate interview experience, one stating:

Just aware of, I guess, current business issues and things like that, … I think it’s just having the outside knowledge of not just “what’s in the book” I guess, having things that’s going on around the world I guess. That’s what I’d take from it. (Participant 7)

Nine participants provided a multi-faceted definition, eight of whom had previous law firm interview experience. That experience will have led to more engagement with the legal sector and its commercial awareness agenda, perhaps creating a deeper understanding. Participant 20, who had already experienced three law firm interviews, demonstrated a sophisticated understanding that incorporated Definition D (legal solution not always the right solution), a less commonly used participant definition recognised within the profession (Strevens et al., Citation2011; LETR, Citation2013; Mitchard, Citation2022) stating:

There’s two components … the first part of it is the kind of knowledge that you have of what’s happening in these commercial environments … it’ll be kind of government policy, so at the minute it’s a lot of the Covid measures, it might be stuff to do with the new budget, … it’s knowledge of what the client plans for their business, what their competitors are doing and what’s happening in those kind of sectors. The second part of it is then how you apply that knowledge to the circumstances that the client is in. So you might say to a client, “Look this is the kind of strict legal advice that I’ve got for you if you … but you know, given the kind of certain commercial factors, the advice might be it’s much better to settle this claim early and not bear the risk.” (Participant 20)Footnote21

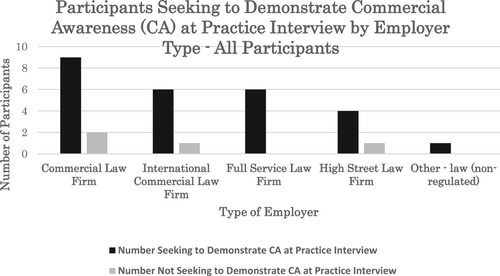

Graph 2. Participants seeking to demonstrate commercial awareness by employer type.Footnote22

Only four participants mentioned Definition E (law firm as a business) and always in combination with other definitions, one stating:

I think a lot of people think it’s like what’s going on in the headlines and stuff; it’s that and it’s the fact that a law firm is a business as well as a law firm. (Participant 19)

Although all of the participants provided a definition of commercial awareness, five stated that they lacked confidence in their ability to do so or required further guidance, for example:

I still don’t really understand it to be honest. I sort of get what it is sort of but I don’t feel 100% confident with it. (Participant 5)

Overall, the data suggests, perhaps unsurprisingly, that participants with more law firm interview experience had a more sophisticated understanding of commercial awareness and more confidence in articulating that. Their definitions aligned more clearly with those of the profession.

Theme 2 – the pervasive influence of law firms regarding the importance of commercial awareness

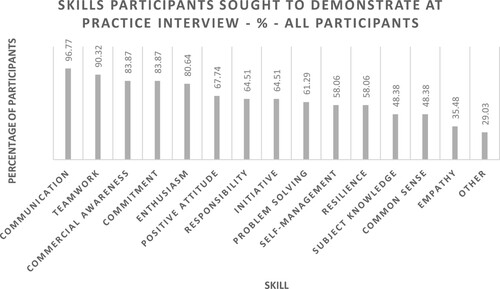

In the pre-practice interview questionnaires, participants selected skills they hoped to demonstrate in the practice interview. By seeking to demonstrate certain skills in the practice interview, participants were considering the skills they thought would be assessed by law firms at interview. Graph 1 demonstrates that commercial awareness was the joint third most selected skill with 83.87% of the total sample (31 participants) seeking to demonstrate it in the practice interview. Of the 20 participants attending the semi-structured interviews, 17 participants (85%) sought to demonstrate commercial awareness in the practice interview.

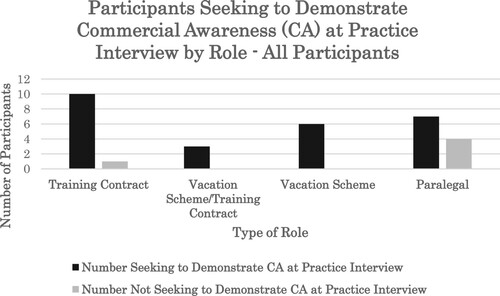

Participants applying to all types of law firm sought to demonstrate commercial awareness (Graph 2), indicating participants thought it would be required at interview across the law firm spectrum, not just by commercial law firms. This reflects views that it is a “universal employability trait” (Strevens et al., Citation2011, p. 341) required across the sector (Williams, Citation2019). Participant views clearly differed to those expressed in the LETR (Citation2013, para. 4.69) where commercial awareness was deemed relevant mainly to individuals seeking to practise commercial/corporate law.

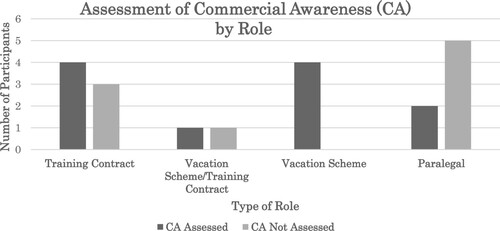

95% of participants applying for training contracts and/or vacation schemes – the latter acting as a gateway to a training contract (Francis & Sommerlad, Citation2009) – sought to demonstrate commercial awareness compared to 63.63% of paralegal applicants, suggesting students may deem it less relevant for paralegal roles (Graph 3). This finding supports the graduate interview data, explored later, that indicates there is less assessment of commercial awareness in paralegal interviews than in training contract/vacation scheme interviews.

It is critical to consider why students focus on commercial awareness. The qualitative data provides insight, with many participants noting its significance to law firms, for example:

I think for a law firm it would definitely be at the top … interviews and stuff like that and their applications, it’s always going to be needed. (Participant 17)

I would say it’s one of the most important things, especially, obviously, if you’re applying to a commercial firm because … it just shows … a lot of different skills and it shows that you’re proactive and you can actually make yourself stand out quite a lot by having good commercial awareness. (Participant 18)

Even if you don’t want to go into commercial law, I think all law firms expect you to have some kind of commercial awareness and … students don’t really appreciate that either. They think, “Oh, I want to go into property, I want to go into family – I don’t need to be commercially aware because I don’t want to go into a commercial firm.” And it’s like, “No, that’s not how it is!” (Participant 12)

I think the law firms are very explicit in saying that that’s what they’re looking for. (Participant 20)

The data analysis now goes on to explore whether the perceived importance of commercial awareness to law firms was reflected in reality in the graduate interview.

Theme 3 – the lived experience of the graduate interview

The accounts of the 20 participants who returned to discuss their graduate interviews provide some unique insight into the lived experience of a law firm graduate interview, in terms of student perceptions of how commercial awareness is assessed and how they experience that assessment. 11 participants (55%) stated commercial awareness had been assessed in their graduate interview and nine participants (45%) stated it had not. As noted, 85% of these participants sought to demonstrate commercial awareness in the practice interview indicating there was a gap between student expectations and the reality of the graduate interview in terms of assessment. This data also contrasts with Etherington’s findings (Citation2016) where 89% of students stated commercial awareness had been assessed at law firm interviews.Footnote25 Of course, students may not always recognise assessment – recognition may depend on what it means to each student and those with a more limited understanding may not always identify assessment. That said, participant discussions were detailed and participants took time to consider if assessment had occurred. It would be instructive to undertake a larger scale research study with law firms to understand how much they assess commercial awareness to provide a further and updated comparison with earlier studies (Etherington, Citation2016; Sommerlad, Citation2011).

Who is assessing and for what roles?

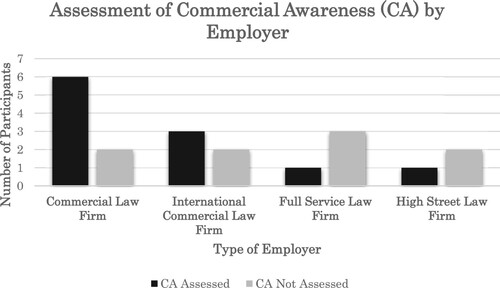

Graph 4 shows a range of employers assessed commercial awareness at interview. It was more commonly assessed by commercial/international commercial law firms (69%) than full service (25%) or high street firms (33%), reflecting the LETR viewpoint on its importance to commercial firms.

Graph 5 demonstrates that commercial awareness was assessed less frequently at paralegal interviews than in “higher stakes” (and perhaps more competitive) vacation scheme/training contract interviews, reflecting participant perceptions of its lower importance for paralegal roles noted earlier.

Of the five participants interviewed by international commercial law firms, three vacation scheme/training contract applicants were assessed for commercial awareness but two paralegal applicants were not. This suggests that when international commercial firms recruit for more lucrativeFootnote26 and competitive roles, commercial awareness is more likely to be assessed. It would be useful to undertake further research into paralegal recruitment at a later date, and on a larger scale, to ascertain what impact the SQE has on paralegal interviews given candidates may later qualify as solicitors within those firms.

What are law firms asking?

The qualitative data demonstrates commercial awareness was assessed using a range of questions ().

Table 1. Sample questions.

Several questions tested interviewee knowledge of the “law firm as a business” aspect of commercial awareness. As noted, only four participants identified this as an aspect of commercial awareness – if students do not appreciate this, they will struggle to answer such questions. This is evidenced by the following participant experience:

… and then they gave me a really weird question – because I was on about how much I enjoyed their voluntary work and they were like “Is it a business or a service?” and they were all really quiet and they were like “This is the question that will say everything” and I’m like “Right OK, stress, stress, stress.” (Participant 6)

Opportunities and challenges

Some participants used commercial awareness questions as an opportunity to demonstrate their sophisticated levels of commercial awareness and to gain an advantage over other candidates. Those with a multi-layered understanding of commercial awareness and with more experience of the graduate recruitment process provided sophisticated answers, such as:

I talked about client retention ‘cos I said that the commodification of legal services means that clients are getting smarter about their legal services and instead of going to one firm for all their needs if it’s cheaper to go to different firms they don’t have any loyalty to one firm. So if it’s cheaper for them to get corporate and then they’ll go to another firm for employment matters if it’s cheaper to do that. I said that the challenge is sort of cross-selling and getting clients to come to you for all the business needs rather than going elsewhere where it’s cheapest. (Participant 1)

I’ve noticed sometimes in interviews I just say something that I’ve read and I think “Oh I wasn’t even planning to say that I just remember that I read that!” (Participant 9)

Other participants described difficulties articulating their commercial awareness at interview, feeling “caught out” by questions. One expressed concerns for the future:

I think it’s how do you become commercially aware so then you can talk about that in an interview? Because I think we talk about it a lot but … I think if they pinpointed me on a question on it I would be a little bit “I don’t really know how to answer it.” (Participant 5)

One solution might be to harness the benefits of part-time work, experience that is an excellent way of developing and demonstrating commercial awareness because it enables students to show an understanding of how a business operates and their role within that business. This would be particularly helpful when asked questions such as “What does commercial awareness mean to you?” or “How can you demonstrate your commercial awareness?” Francis (Citation2015, p. 184) found law firms open to hearing the “story” of how part-time work might demonstrate a candidate’s commercial awareness. Indeed, some firm websites note how part-time work can be used to develop and demonstrate commercial awareness.Footnote27 In this study, only one (ultimately successful) participant mentioned part-time work when answering commercial awareness questions. She told her interviewers:

“That’s where I got all my commercial awareness … that’s really where it’s grown from, it’s kind of learnt, it is my second nature kind of thing.” (Participant 12)

Overall, it is suggested that there is more that law firms and law schools can do to work with students in providing additional support by demystifying commercial awareness and clarifying how their everyday experience can be used to provide compelling evidence of it during graduate interviews.

Flipping the interview

Six of the nine participants who thought commercial awareness was not assessed stated that they sought to demonstrate it anyway by introducing it into the interview, further adding to the argument about the influence of the commercial awareness narrative on students. By “flipping” the interview, participants provided evidence of their commercial awareness, for example:

A lot of the answers I gave, I gave a commercial awareness response on. So one of the things they asked me was describe yourself in three words. So I said … I made up one long word that kind of knows random things about like politics and business. So I was kind of saying “I’m commercially aware” … but no, no, they didn’t really ask me anything directly commercially awareness related. (Participant 3)

… the question I asked, I feel it brought up a lot of commercial awareness issues, particularly where the firm’s going, what the future for the firm looks like, what challenges are coming up. (Participant 15)

I managed to get that in in previous questions anyway so in questions about the SLO,Footnote28 … it being more commercially aware and about not just understanding the theory behind whether someone’s got a legal position but also whether it’s worth pursuing it … So when it got to the commercial awareness part, they basically said “You’ve already done this but we’re still going to ask you the questions anyway.” (Participant 10)

Four participants who were assessed on commercial awareness took further opportunities to incorporate it into the interview. Overall, 10 participants “flipped” the interview. For some, the reasons for this strategy may be linked to prior law firm interview experience – perhaps it was a factor in previous interviews and so they tried to incorporate it into their latest interview. However, this line of argument does not explain why participants with no such experience also took this approach. One reason for this tactic may be linked back to participant perceptions of the importance of commercial awareness to law firms, influenced by the anticipatory socialisation effect of recruitment literature and other graduate communications – an approach considered in other disciplines (Handley, Citation2018; Gebreiter, Citation2020). These participants were, perhaps, attempting to highlight their commercial awareness to fit perceived employer requirements. Of course, the practice interview may have been influential in their decision to attempt to incorporate commercial awareness into their graduate interview; participants were asked questions that tested their commercial awareness and several stated they would improve their commercial awareness afterwards.

Participant success

Of the 20 participants who returned for a semi-structured interview, 12 succeeded at their graduate interviewFootnote29 with seven obtaining graduate employment with their target employer. Of the nine participants that displayed a multi-faceted understanding of commercial awareness, eight were successful at interview. All had previous graduate interview experience and were either assessed on commercial awareness or flipped the interview. The other four successful participants adopted a basic definition of commercial awareness and had no previous graduate interview experience. Three of these participants were not assessed on commercial awareness, obtaining paralegal roles. The remaining participant (Participant 12) sought to improve her commercial awareness after the practice interview and was assessed on it throughout the recruitment process before obtaining a training contract. Although there will be a range of factors involved in participant success, it is interesting to note the potential link between sophisticated understandings of commercial awareness, assessment at interview and selection. It would be instructive to examine this further, ideally in a larger scale study involving students from a number of institutions and a variety of law firms, to provide some further validity to this data.

Conclusions

The law students in this study defined commercial awareness in a range of ways. Some adopted a basic definition whilst others had a more sophisticated understanding that seemed linked to previous interview experience and engagement with law firm commercial awareness narratives via websites and student-employer interactions. These narratives were reiterated by organisations with an interest in supporting access to the profession. Few participants referenced the “law firm as a business” aspect of commercial awareness that is now so critical to the profession and that, as the results demonstrate, was assessed at interview. This study found that assessment of commercial awareness at interview was common but not guaranteed and could be firm and role dependent. Participants applying for higher-stakes training contracts or vacation schemes, particularly in commercial law firms, were more likely to be assessed on commercial awareness at interview than participants seeking paralegal roles. This supports the LETR assertion that commercial awareness is of more importance to those working in commercial law.

This study provides insight into how commercial awareness is assessed in law firm interviews. Questions focused on some, but not all, of the parameters of the author’s suggested definition of commercial awareness. Many questions focused on the “law as a business” aspect of the definition, perhaps providing further evidence of its importance to the profession and its ongoing transition to a much more commercialised setting. Some questions were predictive in nature and some required interviewees to comment on complex issues that perhaps would challenge lawyers with many years of professional experience. All of the questions required some level of prior preparation. There were undoubted challenges for some participants regarding the questions asked and the seemingly high expectations of some law firms. However, assessment presented opportunity for some participants because they were able to articulate a sophisticated understanding of commercial awareness, feeling they could set themselves apart from other candidates.

Through the preparatory lens of the practice interview, this study finds evidence of the perceived importance of commercial awareness to law students seeking employment in law firms. Most participants in this study were conscious of the need to prepare for and practise their commercial awareness skills in order to be ready for their interview, irrespective of the firm and the role applied for. However, some went further. Even if commercial awareness was not assessed at interview, many participants tried to cement their status as commercially aware candidates on the basis that that is what their target law firm was looking for, even if, in fact, it wasn’t. Whilst recognising that several other factors influenced interview outcomes, in particular participants’ prior interview experience, where commercial awareness was a factor at interview, those with confident and sophisticated levels of commercial awareness, tended to succeed.

The findings of this study may have implications for law schools tasked with helping students to access the legal profession and for law firms that seek to recruit them. This study perhaps enhances the understanding of both stakeholders on the impact that the commercial awareness mandate exhibited by key players in the legal profession has had and is having on its future workforce. This study tentatively suggests that the focus on commercial awareness that started in the larger commercial law firms that dominate recruitment to the profession has worked in terms of influencing future entrants to the profession. The findings here indicate that the law students in this study believed that commercial awareness is required at the start of their legal careers, irrespective of firm and role, and not at some point in the future. The findings may also indicate that the commercial awareness rhetoric employed by law firms through their recruitment policies is helping to create the next generation of commercially aware lawyers who may take that remit to whichever firm or profession they later enter – graduates who perhaps will never work in the firms that push the commercial awareness mandate the most. The commercial awareness messaging is working but the findings here suggest that it needs refinement. Some of the participants in this study struggled at interview because they lacked confidence in their commercial awareness, often because their understandings of what commercial awareness meant did not align with those of the profession. Both law schools and law firms need to appreciate the challenges that the assessment of commercial awareness presents to students. The findings suggest that law schools need to do more to enable students to understand what commercial awareness means and how to prepare for and articulate it during graduate interviews. This is also important because commercial awareness is required across the graduate recruitment spectrum (ISE, Citation2020, p. 17) and many law students find careers outside law. In a law firm context it is hoped that this study, with its focus on law students in a post-92 university, will be of benefit to all law firms but particularly those that have a strategic and commendable commitment to social mobility and the Levelling Up agenda.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank all of the students at Northumbria University (past and present) who participated in this research study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Exact numbers are not available but Williams et al (Citation2019) estimated that around 39% of law graduates entered the legal profession in 2016.

2 Reviewing the graduate recruitment webpages of the top 50 UK law firms, finding 30 firms mentioned commercial awareness in their recruitment literature.

3 “Post-92” means a UK university that was formerly a polytechnic.

4 For a further discussion of the timing issues concerning the teaching of commercial awareness on the LPC and law firm recruitment see McConnell, Citation2022(a).

5 The Purpose Coalition (Citation2021). See also Rare Recruitment https://contextualrecruitment.co.uk/ for law firms using contextualised recruitment practices.

6 For example, Clifford Chance and Norton Rose Fulbright.

7 For a discussion of the role of the law school in developing commercial awareness see McConnell, Citation2023.

8 In fact ranking commercial awareness ahead of other core legal knowledge areas.

9 See for example Slaughter and May’s website that headlines their “quality of service, commercial awareness and commitment to clients.” https://www.slaughterandmay.com/global-working/ Accessed May2023.

10 See for example https://www.simmons-simmons.com. Accessed May 2023.

11 https://www.shoosmiths.co.uk/careers/careers-early/early-careers-blog/blog/commercial-awareness-tailoring-it-to-your-firm-of-choice. Accessed May 2023.

12 https://www.nortonrosefulbright.com/en-au/graduates/what-we-look-for. Accessed May 2023.

13 See for example the commercial awareness hub at https://www.lawcareers.net/commercial-awareness and https://www.thelawyer.com/commercial-awareness. Accessed May 2023.

14 https://www.macfarlanes.com/join-us/early-legal-careers/faqs/; https://gateleyplc.com/insight/careers/an-introduction-into-developing-commercial-awareness/ Accessed May 2023.

15 https://cms.law/en/media/local/cms-cmno/files/publications/other/cr-bbf-resources-commercial-awareness. Accessed May 2023.

16 https://careers.linklaters.com/en/early-careers/commercial-awareness Accessed May 2023.

17 “Graduate interview” denotes interviews for graduate roles including vacation schemes (used by many law firms as part of the recruitment process).

18 See Graph 1 for skills.

19 Three postgraduate participants had attended Russell Group universities prior to joining Northumbria University.

20 https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/awards-2022-winners-announced. Accessed May 2023.

21 This participant used this when asked at interview “What does commercial awareness mean to you?” He was told in the interview that this was an “excellent answer.”

22 Graph 2 shows the results for 30 of the 31 participants. 1 participant did not stipulate the type of firm applied to as they had not decided and wanted a practice interview for a training contract. This participant wanted to be assessed on commercial awareness and is now working in a high street law firm.

23 Websites (Citation2023).

24 https://www.aspiringsolicitors.co.uk/. Accessed May 2023.

25 Most students assessed by large/medium commercial firms; “wider experience” mentioned but it is unclear what firm types this included.

26 The starting trainee salary at Clifford Chance, the second biggest UK law firm is £50,000, rising to £125,000 on qualification. The firm pays also SQE fees and maintenance. See https://careers.cliffordchance.com/london/what-we-offer/training-contract.html. Accessed May 2023.

27 https://gateleyplc.com/insight/careers/an-introduction-into-developing-commercial-awareness/; https://cms.law/en/media/local/cms-cmno/files/publications/other/cr-bbf-resources-commercial-awareness

28 SLO (Student Law Office) denotes the clinical legal education facility at Northumbria University.

29 Moving to the next stage of the recruitment process or offered graduate roles immediately.

References

- Ashdown, J. (2015) Shaping diversity and inclusion policy with research, Fordham Law Review, 83(5), pp. 2249–2275.

- Ashley, L. & Empson, L. (2013) Differentiation and discrimination: understanding social class and social exclusion in leading law firms, Human Relations, 66(2), pp. 219–244.

- Blackhurst, C. & Stoakes, C. (1985) Clients rank London’s law firms, International Financial Law Review, 4, pp. 15–23.

- Bleasdale, L. & Francis, A. (2020) Great expectations: millennial lawyers and the structures of contemporary legal practice, Legal Studies, 40(3), pp. 276–396.

- Bowley, R. (2020) Enabling law students to understand business concepts: reflections on developing a business case study for corporate law, The Law Teacher, 54(2), pp. 169–193.

- Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology, Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, pp. 77–101.

- Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2021) One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis, Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), pp. 328–352.

- Brett, B. & Wheeler, K. (2022) How to do Qualitative Interviewing (Los Angeles: Sage Publications Ltd).

- The Bridge Group. (2017) Introduction of the solicitors qualifying examination: monitoring and maximising diversity.

- Brown, C. & McGirk, T. (1982) The leading Euromarket law firm, International Financial Law Review, 1(6), pp. 4–9.

- Collier, R. (2005) Be smart, be successful, be yourself … ’? representations of the training contract and trainee solicitor in advertising by large law firms, International Journal of the Legal Profession, 12(1), pp. 51–92.

- Dunne, N. (2021) Liberalisation and the legal profession in England and Wales, Cambridge Law Journal, 80(2), pp. 274–307.

- Etherington, L. (2016) Public professions and private practices: access to the solicitors’ profession in the twenty-first century, Legal Ethics, 19(1), pp. 5–29.

- Evans, C. & Richardson, M. (2017) Enhancing graduate prospects by recording and reflecting on part-time work: A challenge to students and universities, Industry and Higher Education, 31(5), pp. 283–288.

- Francis, A. (2015) Legal education, social mobility, and employability: possible selves, curriculum intervention, and the role of legal work experience, Journal of Law and Society, 42(2), pp. 173–201.

- Francis, A. & Sommerlad, H. (2009) Access to legal work experience and its role in the (re)production of legal professional identity, International Journal of the Legal Profession, 16(1), pp. 63–86.

- Gebreiter, F. (2020) Making up ideal recruits graduate recruitment, professional socialization and subjectivity at big four accountancy firms, Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 33(1), pp. 233–255.

- Guest, G., Bunce, A. & Johnson, L. (2006) How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability, Field Methods, 18(1), pp. 59–82.

- Handley, K. (2018) Anticipatory socialization and the construction of the employable graduate: a critical analysis of employers’ graduate careers websites, Work, Employment and Society, 32(2), pp. 239–256.

- Hanlon, G. (1997) A profession in transition? Lawyers, the market and significant others, Modern Law Review, 60(6), pp. 798–822.

- Hanlon, G. (1999) Lawyers, the State and the Market: Professionalism Revisited (Basingstoke: Macmillan).

- Hanlon, G. & Jackson, J. (1999) Last orders at the Bar? Competition, choice and justice for all – the impact of solicitor-advocacy, Oxford Journal of Legal Studies, 19, pp. 555–582.

- Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA). https://www.hesa.ac.uk/data-and-analysis/performance-indicators/widening-participation. Accessed May 2023.

- Huxley-Binns, R. (2011) What is the Q for?, The Law Teacher, 45(3), pp. 294–309.

- Institute of Student Employers. (2020) Student development survey 2020, supporting the learning and development of entry level hires.

- Institute of Student Employers (2021) Student recruitment survey 2021. The market bounces back!

- Institute of Student Employers. (2022) Student development survey 2022, supporting learning and development for entry level hires.

- KPMG. (2020) Contribution of the UK legal services sector to the UK economy. A report for the Law Society.

- The Law Society. (2020) Diversity profile of the solicitors’ profession 2019. https://www.lawsociety.org.uk/topics/research/diversity-profile-of-the-solicitors-profession-2019. Accessed May2023.

- The Law Society. (2022) Trends in the solicitors’ profession, annual statistics report 2021, September 2022. https://www.lawsociety.org.uk/topics/research/annual-statistics-report-2021. Accessed May2023.

- Legal Education and Training Review. (2013) Setting standards – the future of legal services education and training regulation in England and Wales. https://letr.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/LETR-Report.pdf. Accessed May 2023.

- McConnell, S. (2022a) A systematic review of commercial awareness in the context of the employability of law students in England and Wales, European Journal of Legal Education, 3, pp. 127–175.

- McConnell, S. (2022b) A study of supervisor and student views on the role of clinical legal education in developing commercial awareness, International Journal of Clinical Legal Education, 29, pp. 4–67.

- McConnell, S. (2023) How do law students develop commercial awareness? Listening to the student voice on the roles of the law school and the law student in developing commercial awareness, Liverpool Law Review, 44, pp. 107–136.

- Mitchard, P. (2022) Professional training in legal education: the case of Hong Kong, The Law Teacher, 56, pp. 1–14.

- Moorhead, R. & Hinchly, V. (2015) Professional minimalism? The ethical consciousness of commercial lawyers, Journal of Law and Society, 42(3), pp. 387–412.

- Nicholson, A. (2021) The value of a law degree – part 2: a perspective from UK providers, The Law Teacher, 55(2), pp. 241–257.

- Nicholson, A. (2022) The value of a law degree – part 4: a perspective from employers, The Law Teacher, 56(2), pp. 171–185.

- Nicolson, D. (2015) Legal education, ethics and access to justice: forging warriors for justice in a neo-liberal world, International Journal of the Legal Profession, 22(1), pp. 51–69.

- Oakley, E. & Vaughan, S. (2019) In dependence: the paradox of professional independence and taking seriously the vulnerabilities of lawyers in large corporate law firms, Journal of Law and Society, 46(1), pp. 83–111.

- Paterson, A., Farmer, L., Stephen, F. & Love, J. (1988) Competition and the market for legal services, Journal of Law and Society, 15, pp. 361–373.

- The Purpose Coalition. (2021) Levelling up law opportunity action plan. https://www.fit-for-purpose.org/engage/levelling-up-law-opportunity-action-plan-virtual-launch. Accessed May2023.

- QAA. (2023) Subject Benchmark Statement for Law. The Quality Assurance Agency. https://www.qaa.ac.uk/the-quality-code/subject-benchmark-statements/subject-benchmark-statement-law# Accessed May 2023.

- Sommerlad, H. (2011) The commercialisation of law and the enterprising legal practitioner: continuity and change, International Journal of the Legal Profession, 18(1), pp. 73–108.

- Statista a. (2023) https://www.statista.com/topics/8517/legal-services-industry-in-the-uk/#topic. Accessed May 2023.

- Statista b. (2023) https://www.statista.com/statistics/611391/largest-law-firms-by-turnover-united-kingdom-uk/. Accessed May 2023.

- Stratton, J. (1992) Quality street, New Law Journal, 142, pp. 1444.

- Strevens, C., Welch, C. & Welch, R. (2011) On-line legal services and the changing legal market: preparing law undergraduates for the future, The Law Teacher, 45(3), pp. 328–347.

- The Teaching Excellence Framework. (2022) https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/teaching/about-the-tef/. Accessed May2023.

- Thomas, L. (2018) It puts the law they’ve learnt in theory into practice: exploring employer understandings of clinical legal education, in: L. Thomas, S. Vaughan, B. Maklani & T. Lynch (Eds) Reimagining Clinical Legal Education (Oxford: Bloomsbury Publishing), pp. 139–154.

- Tomlinson, M. (2017) Forms of graduate capital and their relationship to graduate employability, Education + Training, 59(4), pp. 338–352.

- Tomlinson, M. (2021) Employers and universities: conceptual dimensions, research evidence and implications, Higher Education Policy, 34, pp. 132–154.

- Turner, J., Bone, A. & Ashton, J. (2018) Reasons why law students should have access to learning law through a skills-based approach, The Law Teacher, 52(1), pp. 1–16.

- Websites. https://careers.linklaters.com/en/early-careers/commercial-awareness; https://careerinsights.slaughterandmay.com/post/102ga2o/practical-ways-to-develop-commercial-awareness and www.eversheds-sutherland.com/global/en/where/europe/uk/overview/careers/graduates/what-we-look-for.page?. Accessed May 2023.

- Wilkinson, D. & Aspinall, S. (2007) An Exploration of the Term ‘Commercial Awareness’: What it Means to Employers and Students (Coventry: National Council for Graduate Entrepreneurship).

- Williams, M., Buzzeo, J., Cockett, J., Capuano, S. & Takala, H. (2019) Research to inform workforce planning and career development in legal services, Employment trends, workforce projections and solicitor firm perspectives final report. https://www.employment-studies.co.uk/system/files/resources/files/537.pdf. Accessed May 2023.