Abstract

The so-called Kulturkampf, the conflict between the German Reich and the Catholic Church in the 1870s and 1880s, is one of the most important ideological conflicts of the late nineteenth century and reveals a political theological dynamic characteristic of the modern (German) nation state. This paper analyzes the paradoxes of this conflict along the lines with Eric Santner’s analysis of political representations. During the Kulturkampf, Catholic citizens were publicly suspected of not being loyal Germans, and the Catholic Church is widely figured as an (inner) enemy in the liberal press and in modern caricatures. In these polemics, numerous political theological figures emerge: images of a gendered relation of domination of the (female) church by the (male) state, phantasies of the body politic and its precarious unity as well as of its purification respectively of the extermination of its others that continue to determine other ideological conflicts in the twentieth century.

1 introduction

carl Schmitt’s Roman Catholicism and Political Form opens with the famous declaration: “There is an anti-Roman affect” (3; altered trans.). Concise as it is, this phrase functions not only as an axiom which allows Schmitt to develop his notions of the complexion oppositorum and of substantial representation, and thus to put forward his own argument. The five-word clause is also the rhetorical hook with which he leads the reader through his argument, or, in other words, the initial turn by which he achieves the rhetorical dominance that allows him to denounce all criticism as being a mere expression of this very anti-Roman affect, as the clouds of resentment from which the glorious Roman political form emerges and shines all the brighter. Indeed, a rhetorical masterpiece.

For Schmitt’s initial readers, this sentence – the opening of an essay that was published in 1923 in the broader context of political Catholicism – was probably somewhat less striking. For them, speaking of an anti-Roman affect would be anything but a surprise. On the contrary, it would have rather sounded like a factual statement. They would most probably have had vivid memories of it from the so-called “Kulturkampf” in the 1870s and 1880s when polemics against the Catholic Church and its members dominated a large part of German public debate. Again and again, both Protestants and secular liberals would denounce the Catholic Church as an outdated institution and Catholics as not being proper Germans. If anything, it was obvious for Catholics in the interwar years that there had been and probably still was a widespread anti-Catholic affect, even if its former proponents seemed to be denying its very existence. Schmitt thus simply states the obvious.

In what follows, I will try to combine these two observations: on the one hand the rhetoric quality of political theology as well as its analytic potential to understand even modern societies, on the other hand the background of a certain historical constellation that might be central for modern political thought, namely the confessional conflict and more precisely the Kulturkampf which coincided with the emergence of the modern German nation state. What I will present, then, is a sort of case study on the paradoxes of modern political representation and of the construction of a modern political body with all its overdetermination that Eric Santner has taught us to analyze (see Santner). On the other hand, I will try to develop a genealogy of modern political theological thought that explores the affective bedrock on which it rests, namely the debates and conflicts, projections and imaginations that go along with the Kulturkampf, the most important and most forgotten political theological conflict of nineteenth-century Germany. Since we are mostly concerned with imaginations and affections, I will do this in three steps along three concepts: conflict, enmity, and reconciliation.

2 conflict

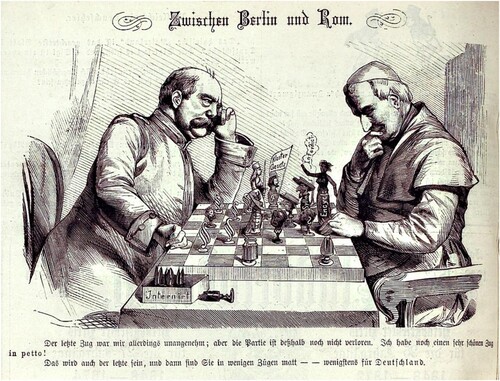

In every usual history textbook you can find a caricature from the Kladderadatsch of 1875 showing Bismarck and Pius IX playing chess (), the latter being already pretty much cornered by paragraphs and lawsuits. This image has long dominated the memory of the Kulturkampf that is depicted as Bismarck’s private project and as a regulated legal conflict that can be narrated as a series of laws, a political maneuver with little profound impact on German culture (Borutta 20–26; Gross 3–22; see also Anderson). The conflict itself was obviously part of a longer history that can be traced back to the biconfessional nature of the Holy German Empire and to the concurrence of that empire with confessional territorial states, among them Prussia, which emerged as the representative Protestant state in the eighteenth century (see Altgeld). When, after the Napoleonic wars, Prussia acquired large Catholic territories in West Germany and what is now Poland, a series of conflicts between the Prussian Protestant bureaucracy and the local inhabitants developed, such as on the status of mixed marriages or the authority of the bishops. These conflicts broke out in the so-called Moabiter Klostersturm, a looting of a newly found monastery in a Berlin working-class quarter in 1869 that caused a public uproar. With the unification of Germany and the founding of the second German Reich, the state tried to resolve those conflicts once and for all by introducing a series of laws intended to limit the power of the Catholic Church. Beginning in 1871, the so-called “Kanzelparagraph” (Pulpit Paragraph) prohibited clergy from speaking out about “matters of state” in a manner “endangering public peace,” a ruling that remained in effect until the 1950s and was among other things used by the National Socialists. In 1872, clerical school supervision was replaced by state supervision, and the Jesuit order was banned; subsequent laws concerned the training of clergy (1873), the introduction of civil marriage (1874–75), a general abolition of monasteries (1875), and state support for the clergy, the so-called “breadbasket laws” (1875) which forced the clergy to be financially dependent on the state (see Borutta; Blaschke).

The caricature presents these laws as chess pieces in a relatively peaceful situation, for agonistic as it might be, a chess game is still a game, played by rules. It is to some extent a Clausewitzian image that underpins the usual narrative of the Kulturkampf that would also argue that this conflict was finally settled by a compromise. Some of the laws mentioned would be revoked in the 1880s, others, such as the state support of schools and civil marriage, would remain in effect. In general, the tensions between church and state were finally settled in what is called the “limping” separation of church and state in Germany, which was first enacted in the Weimar Constitution and was later adopted in the Federal Republic. Limping, because it is far from being radical as is the case with French laicism or even the American wall of separation. To this day, the German state collects church taxes, major Christian churches have a specific legal status, and they are involved on many different levels in the political process. Due to this compromise, so the usual narrative goes, first the Protestants, and then, after the Second Vatican Council, also the Catholics gave up their distrust in parliamentary democracy and identified with the liberal democracy of the Federal Republic of Germany, as if there had never been the breath of a doubt that Christianity, democracy, and human rights belonged together. The narrative, presented this way, is the narrative of the Christian Democrats, and it even comes with its own political theology, that is, the so-called “Böckenförde thesis” developed in the early years of postwar Germany. According to it, though religion and civic society were separated historically, the latter still relies on normative resources produced in the religious realm (see Böckenförde). It is an image of limping secularization, if you will, an image that deeply influenced the specific German understanding of what is secular and what the meaning of secularization is (Borutta 268–88; see also Weidner, Rhetorik der Säkularisierung).

Yet, this narrative is misleading, and the caricature is a misrepresentation, as I will continue to argue. It is a rationalization, or what Freud called a “screen memory,” that hides the absence of a true memory of a phase of German history which was in fact traumatic for many Germans, namely the Catholics, and reveals the limitations of the liberal political order. It is still remarkable how little research exists on this period and how damaging this is in many ways. To mention just one aspect, ignorance of the Kulturkampf distorts our view on the global postcolonial and postsecular condition of the present. In fact, José Casanova noted already in 2009 that Western criticism of Islam bears an uncanny resemblance to the criticism directed towards Catholicism until the Second Vatican: the lack of a boundary between religion and politics, non-respect for human rights, archaic gender roles, or, more generally, backwardness. Furthermore, Casanova argued that Europeans like to point to religious conflicts elsewhere, but tend to forget the troublesome memories of their own past, which is indeed fraught with religious conflicts, among them the Kulturkampf.

3 imagination

The Kulturkampf was not only a political and legal conflict, but a symbolic one. It rattled the very foundations of society, upon which it left an indelible mark. This symbolic dimension can even be seen in the very introduction of the term “Kulturkampf,” its primal scene in the Freudian sense. “Kulturkampf” was coined during a debate in the Reichstag on 17 January 1873, concerning the planned ban of the Jesuits. In this debate, Rudolf Virchow, the famous physician and member of the liberal party, conceded that this legislation could infringe on individual rights – namely religious freedom and the freedom of association – that he as a Liberal would always respect and uphold. However, these same legal measures must be seen in a larger context that dates back to late antiquity, as Virchow makes clear:

I tell you this, because I am convinced that what we are debating is part of a large culture war […] For me, this is not a specific law but has to be conceived in the contest of the great development of centuries. (Preußen 631; my trans.)

The nervous reaction of the liberals had specific reasons. For it soon became apparent that the measures and arguments against the German Catholics did not have their intended effect. In the wake of the Moabiter Klostersturm, the Catholic Center Party was founded, which became increasingly successful in the Reichstag elections and effectively used parliamentary means of resistance to the great annoyance of Bismarck. Moreover, a rich body of associations and a prolific Catholic press developed. Persecuted priests were widely supported by the parishes, and new forms of public piety emerged (Borutta 290–96; see also Blackbourn). Supposedly backward Catholicism proved surprisingly resilient and was able to mobilize its supporters so well that the Kulturkampf ultimately contributed to the formation of a cohesive Catholic milieu that it had intended to prevent.

The nervous reactions of the liberals also reveal the essentially political theological implications of the conflict. In an important article from 1871, the Kreuzzeitung, the more or less official newspaper of Bismarck’s government, explicitly warns against forming a Catholic party in the new Reich:

It means nothing else than to start the unity with the deepest division, if in a political-parliamentary body, which is supposed to represent the German nation and its spirit, the political party formation is imagined and carried out on the basis of confession and the ecclesiastical principle. (Neue Preußische Zeitung 1; my trans.)

Moreover, in this conception, it is decisive how the “spirit” of the German nation is conceived. The answer is usually sought in the past, in the realm of history and “culture.” As in Virchow’s Kulturkampf speech, the article immediately turns to the past, to the history of the Reformation and of the confessional split that hindered Germany’s unity for such a long time, or even further to the interpretation of the first Reich that had just been reinaugurated, to the way in which in that Reich religion and politics were in a healthy relation or not.

In general, the founding of the New Reich allowed for political theological thought in the proper sense to flourish, when, for example, Heinrich von Sybel describes church and state as two different branches of the same tree, each developing “autonomously” in its own direction, yet still complementing each other – a kind of an organic emblem of the “Böckenförde thesis” or the separation of church and state (Borutta 269–82; Gross 246–58). Political theological figures also pop up time and again in public debates, often in the form of ironic invectives, as when the Austrian lawyer Friedrich Maaßen mockingly portrays future bishops swearing the following oath: “I believe in the almighty Prussian state, the laws of which I will follow faithfully even when they contradict the teachings of the Christian religion and the laws of the Catholic Church,” or in pithier form in an imagined confession: “The state is God and the minister of culture is its prophet” (Kissling 196).

Especially the lack of immediate success that the Protestant and liberal opponents of Catholicism had expected turned the symbolic conflicts all the more ferocious and transformed the Kulturkampf into a true culture war, a struggle for hegemony in the realm of culture being fought with all means of culture. If the Catholics still vote for a Catholic party, they probably lack the right German education – it is therefore no coincidence that education became a major focus of legal measures. This includes the education of priests, who were now required to undergo a so-called “Kulturexamen” in German history, philosophy, and literature. Culture itself is thus targeted in a political theological conflict. At the same time, this conflict was transferred into the cultural realm; it became a conflict driven by culture, both high and low. Countless pamphlets, stories, and poems were published that accused the respective other side of being backward or immoral (Borutta 157–217; Gross 128–86; Kissling 272–309, 167–87).

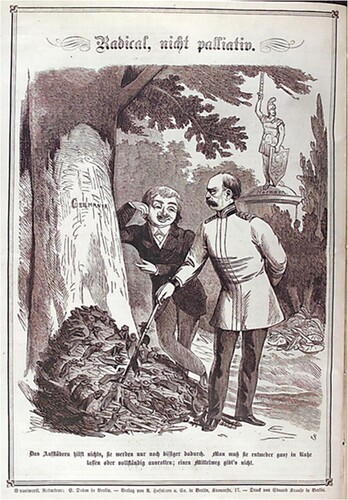

Particularly interesting in that context is one specific medium: the relatively new caricature that was widely disseminated by an emerging mass press. As you may know, caricature emerged in the nineteenth century precisely as a medium for portraying the disfigurement of the political body, as in the famous caricature of the French King Louis Philippe becoming a pear. The Kulturkampf press used these visual forms to depict all kinds of satirical scenes, following an already well-established tradition of anticlerical images. At least some of these scenes do concern the political body, and some may be read as a counter-memory that reveals the threat and the violence of the Kulturkampf. For example, the Kladderadatsch, the leading satirical journal of the time, presents the scene shown in under the heading “radical, not palliative.” Here, Bismarck stands in front of a German oak that has been infected by a nest of insect-like clerics; Kladderadatsch, the figure who personifies the journal, comments: “There is no use in rooting them up. It will only make them more aggressive. You have to either leave them in peace or completely exterminate them” (Borutta 211–13; my trans.).

This image no longer depicts an honorable confrontation, the game of kings, as in our “screen memory,” but a strange configuration of German nature, the oak, a stalwart, upright, unmoved Bismarck and a heap of something ugly, disgusting, abominable, a milling mass of anti-flesh, a tumor-like growth that threatens nature but could be held back by the iron chancellor. It is an emblem of the politics of enmity that drives the Kulturkampf in which German nationhood is constituted by othering. Obviously, the newly founded German Reich, being a latecomer on the scene among the European nations, was in particular need of legitimation, which is only made more explicit through its recourse to the Holy Roman Empire with its long-standing tradition of sacrality. It could be kept only under at least two conditions: first, that the German state remained in full command of the symbolic resources of that empire and under all circumstances avoids giving it away once more to Rome – this is the meaning of Bismarck’s famous “We won’t go to Canossa,” which became a stock phrase in the discussion. Second, the imperial claim rests on the assumption of an organic and healthy body politic and thus has to fend off any threats of infection or subversion so vigorously that it is constantly haunted by phantasies about the inner enemy, about Germans that are not real Germans, about a state within a state, etc. And of course, these suspicions did not go unanswered. Not only did the emerging Catholic press defend the piety and Germanness of Catholics, but it also tended to suggest that the Kulturkampf itself is a conspiracy, devised by freemasons, godless secularists, and Jews. Very soon, anti-Catholicism and anti-Semitism would uncannily imitate and reinforce each other (see Blaschke; Joskowicz). Indeed, the Kulturkampf prefigures other politics of enmity that immediately followed it and that would target both the socialists, against whom exclusionary laws were passed from 1878, and the Jews, against whom anti-Semitism culminated in the late 1870s.

Much more could be said about the political theological implications of nearly all cultural production during the last decades of the nineteenth century. Realist literature in Germany, the novels and stories of Gottfried Keller, Conrad Ferdinand Meyer, or Theodor Fontane, not only abounds with clerical figures but continuously discusses political theological issues even though German studies – historically developed against the background of liberal Protestantism – has tended to overlook this. Most notably the popular genre of the historical novel as well as popular forms of historiography such as Heinrich von Treitschke’s or Gustav Freytag’s “Pictures from the German Past” constantly deal with Protestants and Catholics, Germans and “Romans,” worldly solid protagonists and spiritually mad persecutors, etc. After Felix Dahn published his Kampf um Rom (Battle for Rome) in 1878, one of the most successful historical novels with obvious anticlerical undertones and even more obvious anti-Semitic ones, he received countless disappointed letters from disgruntled readers who mistakenly inferred from the title that the novel would deal with the present conflict and therefore expected more direct and destructive attacks on the papacy.

4 marriage

The political body of the nation is not simple and singular, but divided. It consists of both public and private parts, the visible and the invisible, the different organs. Most of all, it is a gendered body. As Joan Scott has shown, secular liberalism developed alongside a strict separation between a male public sphere and a sphere of female privacy. And this separation has political theological implications as well, even though political theology, a mostly male affair, usually tends to ignore the very idea of gender. On the ground, in social reality, the privatization of religion in the nineteenth century was mostly conceived of as a feminization. It was, after all, male church attendance that steeply dropped at the beginning of the century, religious education became the duty of the mother. The affectization of religion and its focus on family life situated religion on the female side of the newly reconfigured gender divide – Friedrich Schleiermacher’s A Christmas Eve is the classical proof text here (see Weidner, “‘Expression to Our Christmas Feeling’”). In the realm of speculation, political theology became gendered itself. The Swiss legal theorist Johann Caspar Bluntschli, among others, argues that both church and state represent mankind, but in different ways, namely that the state represents the male and the church the female part, which is then also the reason why women, by their nature, should not engage in politics. Bluntschli concludes this speculation of gendered theology with an eschatological vision about future politics:

In our age the male state will come into full existence, recognizing itself and the church. Then the two great powers of humanity, the state and the church, will understand and love each other, and the sublime marriage of the two will be consummated. The unity of the human race will become evident in this united duality. Amen (85; my trans.; see also Borutta 278–83)

In the context of the Kulturkampf, a fierce debate on gender roles ensued as well (Gross 185–239). Especially celibacy had for a long time been a constant target of Protestant and liberal criticism as well as ridicule since it deviates from the “natural” order of the sexes. Moreover, liberals tended to polemicize against the public role that certain female orders play in their social work. No less important is the symbolic level, all the more so since the state, by introducing obligatory civil marriage, actively invests in the realm of private gender relations.

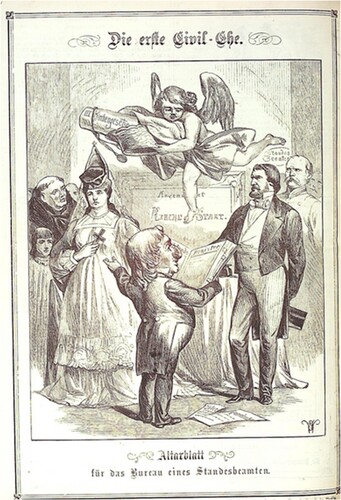

That this investment is not without ironies and paradoxes is expressed in another caricature published by the Kladderadatsch to mark the end of the Kulturkampf (). Entitled “The First Civil Marriage,” it is intended to be used as an “altarpiece” in the office of the marriage registrar and thus in itself represents the act of the state taking over ritual duties (Borutta 370–73). In a mise en abyme fashion the image then depicts what it does, only that the Kladderadatsch represents the registrar who weds the state, represented by Falk, the Minister of Culture, with Bismarck in the background, to the church, represented as a female surrounded by monks and clerics. Neither party looks particularly happy as an angel above, who represents church law, sanctions the union.

What then, do we see here? Is it the new order, is the church now once and for all incorporated into the state? Or does the state rely on the church to run the moral household? Will he require her for special needs and affective moments? To raise potential kids, to act as the affective glue that holds together the emerging national family? He, the state, will, surely, overtake her, the church’s material belongings, but she might still see him behind closed doors, might console him when he fails. And who, by the way, might the Kladderadatsch be, does he have the right mandate, or is he, God forbid, only playing the registrar so that this marriage is effectively not valid? And what if the marriage is dissolved? Who will inherit?

As political theological thought is concerned, we might assume that the notion of an almighty state is a male phantasy, a phantasy that might always be haunted by female desire that the state claims to control. Or, less metaphorically, that political theology is not simply an ontology of the political but continues to be energized by affective energies and cultural differences of which the gender difference is surely a very effective one. Finally, this image shows what the Kulturkampf reveals as well: that the church–state dualism is not easy to dissolve, at least not until death do us part. As for Carl Schmitt, he seems to have understood the attraction of this construction, for in Roman Catholicism and Political Form, which repeatedly stresses the meaning of mythic images, whose effects are much deeper than economic facts or even concepts, Schmitt adopts the image of marriage as an instance of complexion oppositorum:

The union of antitheses extends to the ultimate social-psychological roots of human motives and perceptions. The pope is called the Father, the Church is the Mother of Believers, and the Bride of Christ. This is a marvelous union of the patriarchal with the matriarchal, able to direct both streams of the most elemental complexes and instincts – respect for the father and the love for the mother – towards Rome. Has there ever been a revolt against the mother? (8)

disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

bibliography

- Altgeld, Wolfgang. Katholizismus, Protestantismus, Judentum: Über religiös begründete Gegensätze und nationalreligiöse Ideen in der Geschichte des deutschen Nationalismus. Brill, 1992.

- Anderson, Margaret Lavinia. “The Kulturkampf and the Course of German History.” Central European History, vol. 19, no. 1, 1986, pp. 82–115.

- Blackbourn, David. Marpingen: Apparitions of the Virgin Mary in Bismarckian Germany. Oxford UP, 1993.

- Blaschke, Olaf. Katholizismus und Antisemitismus im Deutschen Kaiserreich. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1997.

- Bluntschli, Johann Caspar. Psychologische Studien über Staat und Kirche. Beyel, 1844.

- Böckenförde, Ernst-Wolfgang. Religion, Law, and Democracy: Selected Writings. Edited by Mirjam Künkler and Tine Stein. Oxford UP, 2021.

- Borutta, Manuel. Altkatholizismus: Deutschland und Italien im Zeitalter der europäischen Kulturkämpfe. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2011.

- Casanova, José. Europas Angst vor der Religion. Berlin UP, 2009.

- “Die erste Zivil-Ehe.” Kladderadatsch, nos. 47–48, 11 Oct. 1874, p. 34.

- Gross, Michael. The War against Catholicism: Liberalism and the Anti-Catholic Imagination in Nineteenth-Century Germany. U of Michigan P, 2004.

- Joskowicz, Ari. The Modernity of Others: Jewish Anti-Catholicism in Germany and France. Stanford UP, 2014.

- Kissling, Johannes Baptiste. Geschichte des Kulturkampfes im deutschen Reiche. 3 vols. Herder, 1911–16.

- Neue Preußische Zeitung, no. 142, 22 June 1871, p. 1.

- Preußen, Haus der Abgeordneten. Stenographische Berichte über die Verhandlungen des Preußischen Hauses der Abgeordneten der durch die Allerhöchste Verordnung vom 1. Nov. 1872 einberufenen beiden Häuser des Landtages, 12 Nov. 1872–21 Jan. 1873. Vol. 1, 1873. 28th session.

- “Radical, nicht palliativ.” Kladderadatsch, nos. 29–30, 30 June 1872, p. 26.

- Santner, Eric. The Royal Remains: The People’s Two Bodies and the Endgames of Sovereignty. U of Chicago P, 2011.

- Schleiermacher, Friedrich. Die Weihnachtsfeier. De Gruyter, 1826.

- Schmitt, Carl. Roman Catholicism and Political Form. Translated by G.L. Ulmen. Greenwood Press, 1996.

- Scholz, Wilhelm. “Zwischen Berlin und Rom.” Kladderadatsch, nos. 22–23, 16 May 1875, p. 91.

- Scott, Joan Wallach. Sex and Secularism. Princeton UP, 2018.

- Weidner, Daniel. “‘Expression to Our Christmas Feeling’: Schleiermacher’s Translation of Religion into the Bourgeois Family.” Beyond Babel: Religion and Linguistic Pluralism, edited by Andrea Vestrucci, Springer, 2023.

- Weidner, Daniel. Rhetorik der Säkularisierung: Über eine Denkfigur der Moderne. Campus, 2024.