“If you fail to plan, you are planning to fail”

It is often suggested that failure to plan is tantamount to a plan for failure. In our clinical experience, we have not come across a clinician who consciously sought out ‘failure’ in their care of others; yet, at the same time, in the context of self-care it is our observation that a lack of planning can certainly become a barrier to effective self-care practice. Here, we suggest that self-care planning supports clinical care, and further represents a form of ‘total care’ in which both patient (or client) and clinician needs are recognised and cared for in clinical practice. In doing so, we draw from Palliative Care Australia’s Self-Care Matters resource (https://palliativecare.org.au/resources/self-care-matters) and its self-care planning process.Citation1

Both common sense and our personal experience suggest that self-care is an important enabler to the care of others. In the same way that the human heart must first pump blood to itself, healthcare professionals must take care of their own health and wellbeing to sustain their capacity to care for the health and wellbeing of others.Citation2 But beyond mere logic, analogy or anecdote, there is research evidence to suggest a clear relationship between staff wellbeing and patient/clients’ experience of care.Citation3 The importance of self-care and self-compassion is made explicit in Watson’s Theory of Human CaringCitation4 and these feature increasingly within emerging healthcare research, including speciality practice areas such as palliative care.Citation5–8

In palliative care the concept of total care represents a continuum beginning with care and compassion for oneself, extending to care and compassion for others.Citation9 Given that self-care is highly relational to those around us, as well have the same potential for human suffering and vulnerability, this notion of total care can be further understood in the context of Dame Cicely Saunders’ pioneering work on the concept of ‘total pain’. Just as Saunders’ elucidation of total pain clarifies the need for total care; self-care, then, might best be understood as an important conduit to the promotion of holistic wellbeing and quality of life for everyone – clinicians, patients/clients, and their families. That is to say, quality of life is a shared concern, and care provider’s quality of life has both personal and professional impacts on their capacity to promote quality of life for patients and their families.

Prioritising self-care by developing a self-care plan is an effective strategy, but many have not developed a self-care plan and would benefit from support to guide them in doing so.Citation10 Although the idea of developing a self-care plan is not new, it remains foreign to most, and for others it may feel selfish or is otherwise not prioritised in practice. Additionally, up until recently there has been very little by way of comprehensive resources to guide individuals in the process of planning for self-care. That is until the Self-Care Matters resource was launched.

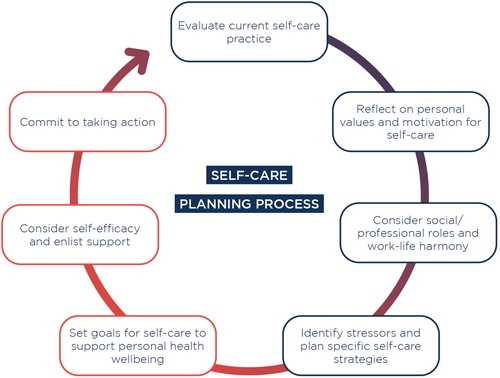

Self-Care Matters was developed to assist individual healthcare providers as well as teams and healthcare services with staff support in the context of promoting workforce wellbeing and resilience. As a free resource available online (https://palliativecare.org.au/resources/self-care-matters), it draws from contemporary research to shed light on understanding self-care, practising self-care, and planning for self-care, through the voice of experienced clinicians. Perhaps the most valuable aspect of the resource is its practical components including meditations on mindfulness and self-compassion, or its systematic planning tool that guides the user through the self-care planning process .Citation1

The self-care planning process comprises seven steps, beginning with a baseline evaluation of current self-care practice and concluding with a commitment to take action. There are both formative and summative aspects to the process, and there is flexibility in that one can choose whether to document an actual self-care plan, or simply reflect and engage with the planning process without documenting anything, if that is preferred. Following the seven steps of the self-care planning process is a systematic way of ensuring that self-care practice is comprehensive and personally tailored to individual needs. It is suggested this process should be revisited (and self-care plans revised) as needed at regular intervals or whenever there is a significant change in personal or professional circumstances.

The main benefits of self-care planning are twofold. First, planning for self-care encourages clinicians to be more proactive in fostering their own wellbeing and resilience. Second, the anticipation of personal and workplace stressors combined with the formulation of personalised strategies and goals for self-care provide a carefully considered guide that can be followed within rapidly changing clinical practice environments. In other words, a well-developed self-care plan affords clarity and structure, even amidst clinical settings that are at times chaotic. In these ways, self-care planning supports clinical care.

Care planning forms an important foundation for clinical practice. Clinical care is holistic and directly guided by prior planning to anticipate barriers and facilitate enablers towards achieving goals of care that promote health, wellbeing, and quality of life. In a similar way, our own planning – for self-care – supports that clinical care. Moreover, in palliative care settings, self-care planning helps to put the theory of total care into practice. The self-care planning process represents a useful framework to guide systematic planning for self-care practice that is tailored to individual contexts, both personal and professional. It is never too late to prioritise self-care and, in our opinion, learning through experience from a previous lack of planning in no way constitutes failure. We encourage all healthcare professionals of any specialty to reflect on their current self-care practice and consider developing a personalised self-care plan as a supportive guide for the future.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Palliative Care Australia. Self-care matters: a self-care planning tool. Canberra, Australian Capital Territory: PCA; 2020. Available from: https://palliativecare.org.au/download/15974/.

- Mills J, Wand T, Fraser JA. On self-compassion and self-care in nursing: selfish or essential for compassionate care? Int J Nurs Stud 2015;52(4):791–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.10.009

- Maben J, Adams M, Peccei R, Murrells T, Robert G. ‘Poppets and parcels’: the links between staff experience of work and acutely ill older peoples’ experience of hospital care. International Journal of Older People Nursing 2012;7(2):83–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-3743.2012.00326.x

- Sitzman K, Watson J. Caring science, mindful practice: implementing Watson's human caring theory. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2013.

- Mills J. Advancing research and evidence for compassion-based interventions: a matter of the head or heart? Palliat Med 2020;34(8):973–975. doi:10.1177/0269216320945970.

- Neff KD, Knox MC, Long P, Gregory K. Caring for others without losing yourself: an adaptation of the mindful self-compassion program for healthcare communities. J Clin Psychol. 2020. doi:10.1002/jclp.23007:1-20.

- Mills J, Wand T, Fraser JA. Palliative care professionals’ care and compassion for self and others: a narrative review. Int J Palliat Nurs 2017;23(5):219–29. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2017.23.5.219

- Mills J, Wand T, Fraser JA. Examining self-care, self-compassion, and compassion for others: a cross-sectional survey of palliative care nurses and doctors. International Journal of Palliative Nursing 2018;24(1):4–11. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2018.24.1.4

- Beng TS, Chin LE, Guan NC, Yee A, Wu C, Pathmawathi S, et al. The experiences of stress of palliative care providers in Malaysia: a thematic analysis. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 2015;32(1):15–28. doi: 10.1177/1049909113503395

- Mills J, Wand T, Fraser JA. Self-care in palliative care nursing and medical professionals: a cross-sectional survey. J Palliat Med 2017;20(6):625–30. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2016.0470