Abstract

Background

Most people would prefer to die at home. Engaging citizens in end-of-life care may contribute to making home death possible for more people.

Aims

To test the feasibility and acceptability of Last Aid Courses in different countries and to explore the views and experiences of participants with the course.

Methods

International multi-centre study with a questionnaire based mixed methods design. 408 Last Aid Courses were held in three different countries. Of 6014 course participants, 5469 participated in the study accounting for a response rate of 91%.

Results

The median age of participants was 56 years. 88% were female. 76% of participants rated the course “very good”. 99% would recommend it to others. Findings from the qualitative data revealed that participants found the atmosphere comfortable; instructors competent; appreciated the course format, duration, topics and discussions about life and death.

Conclusions

Last Aid Courses are both feasible and accepted by citizens from different countries. They have a huge potential to inform citizens and to encourage them to engage in care at home. Future research should investigate the long-term effects of the course on the ability and willingness of participants to provide end-of-life care and the impact on the number of home-deaths.

Introduction

The need for palliative care is expected to increase due to the growing number of elderly people with multi-morbidity, dementia and frailty.Citation1–3 As most people would prefer to die at home, communities should prepare for an increasing number of people needing palliative care at home.Citation3,Citation4 To make home death possible for more people and to meet their needs, all health-care systems have to cooperate with communities including relatives, friends and neighbors. According to Kellehear “end-of-life care is everyone’s business” and compassionate communities include the public in end-of-life care.Citation5,Citation6 Thus, end-of-life care is a public health issue. The Public Knowledge Approach and the Last Aid Course are strategies for raising awareness and improving citizens’ public knowledge about death, dying and palliative care, and were first described by Bollig in 2008.Citation7–11 Many people have neither seen a dead person, nor do they have experience with end-of-life care. Presumably there are many barriers and fears to caring for dying relatives or friends at home. In other words, death literacy is needed. Various authors have stated a need for education of the public about palliative care.Citation5–8 However, public awareness of palliative care and broad implementation of options for support in end-of-life care are lacking.Citation12–15 Public palliative care education may contribute to enabling citizens to participate in end-of-life care. The main aims of the Last Aid Course project are to raise awareness, to empower citizens to recognize the need for palliative care and to participate in its provision. A German pilot study from 2015 has indicated the feasibility and acceptance of the Last Aid Course by citizensCitation9 and the Last Aid concept has become widely recognized.Citation16,Citation17

Aim: To test the feasibility and acceptability of Last Aid Courses in different countries and to explore the views and experiences of Last Aid Course participants with the course, including their opinion about course content and format.

Methods

Study design and analysis

An international multi-centre study with a mixed methods design was employed to provide a richer picture of the views and experiences of Last Aid Course participants. As an assessment tool, a pilot-tested questionnaireCitation9 including both quantitative and qualitative data was used (). It includes; ranking of the modules and the course as a whole, closed questions and open questions. Doubts about data coding were discussed between the authors. In cases where two people completed a questionnaire together, this was treated as two questionnaires. Questionnaires with missing data were included and missing data registered (see ).

Table 1 The Last Aid Course questionnaire

Descriptive statistics were used to describe participants’ characteristics. Continuous variables were reported as medians and interquartile ranges. Categorical variables were presented as percentages. To investigate differences in the rating of Modules 1–4 between gender, age groups, and professions, a dichotomous outcome variable was constructed from the answer categories: “very good” and “others” (composed of “good”; “satisfactory” and “inadequate”). A univariate logistic regression was used to derive odds ratios (OR) and confidence intervals (CI). Significance was set at 5%. All quantitative data analyses were performed using Stata software, version 16.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Qualitative data derive from the open questions of the questionnaire. Qualitative descriptionCitation18–20 was used for analysis of the qualitative data. Reporting of the findings is based on a reporting guideline for mixed-methodsCitation21 and COREQ guidelines for reporting qualitative researchCitation22 from the EQUATOR network.Citation23 Analysis of the themes found in the data material and the coded text was performed iteratively. As a measure to validate the findings, repeated reading of the informants’ written comments and repeated discussions between the authors were undertaken, in order to question the findings.Citation24

Setting, participants and sample selection

All courses complied with the international rules for Last Aid Courses. Course participants from Germany, Switzerland and Austria were asked to complete a questionnaire about participants’ views on the course and its contents directly after the end of module 4 in German. An English version is shown in .

Inclusion criteria:

German speaking Last Aid Course participants

Exclusion criteria:

Incomplete participation in the Last Aid Course

All participants were informed that participation in this evaluation was voluntary and that they could choose not to complete the questionnaire if they did not want to. Data were collected from January 2015 to June 2018.

The Last Aid Course concept and instructor training

The Last Aid Course was created to inform the general public based on the presupposition that most people would prefer to attend only once with minimal time consumption.Citation7,Citation9 The idea of the Last Aid Course was first described in 2008Citation7 and uses a curriculum that has been designed by an international working group.Citation9,Citation11 The Last Aid Course consists of four modules (each of 45 min duration) taught during one day. The four modules are: 1. Dying as a normal part of life; 2. Planning ahead; 3. Relieving suffering; 4. Final goodbyes. Themes include end-of-life care, advance care planning and decision-making, symptom management, burial and cultural aspects of death and bereavement. Instructors have experience from the field of palliative care and include nurses, physicians, social workers, priests, hospice volunteers, etc. The Last Aid Course includes both education (e.g. measures to relieve pain, breathlessness, nausea and information about local available palliative care services and support) and reflection about death and dying in general. All instructors received one whole day of training. A trial lecture was used as an exam, as a prerequisite for certification as instructor. The Last Aid Course must be held by a team of two certified instructors, one of whom is either a nurse or a doctor working in palliative care. The contents of the Last Aid Course are shown in . The curriculum and slide presentation are based on a consensus by international experts from the International Last Aid working group with members from 16 European countries.Citation25

Table 2 The Last Aid Course contents

Results

Participant characteristics

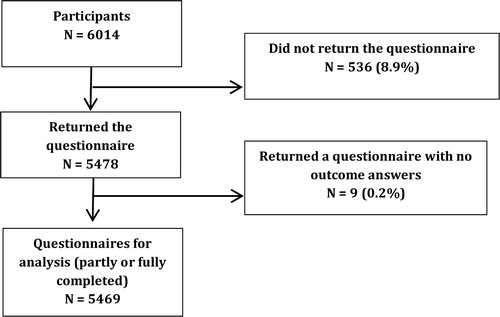

408 Last Aid Courses were held in three different countries (Germany 388, Switzerland 13, Austria 7). Of 6014 participants, 5478 returned the questionnaire and 5469 completed the questionnaire for analysis with a response rate of 91% ().

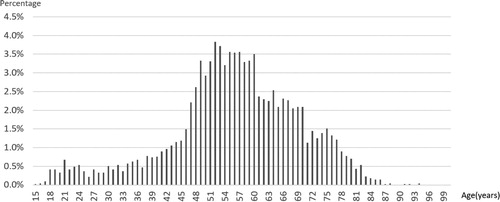

Basic data from the participants are shown in . The median age of participants was 56 years (interquartile range 49–65; ); 88% were female.

Figure 2 Age distribution of Last Aid Course participants. Note: Age range from minimum 15 to maximum 94

Table 3 Basic data from the participants

Participants’ views and ranking

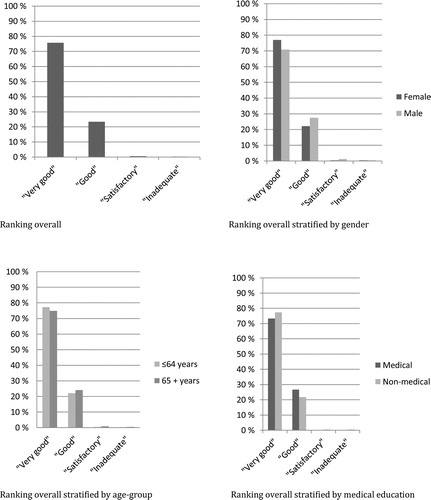

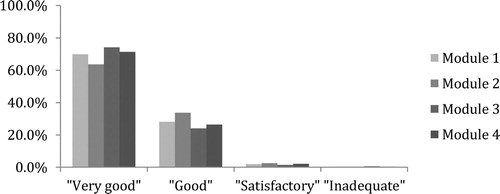

Overall, the course was feasible and well accepted by the participants. 99% found the contents of the course easy to understand (0.7% missing data), 84% stated that they had learned many new things (4.1% missing data), 98% found the Last Aid Course beneficial for everyone (1.7% missing data), and 99% would recommend it to others (1.7% missing data). The overall ranking of the course is shown in . 76% rated the course “very good” (15.4% missing data) and the same trend persisted after stratifying for gender, age and medical education. All modules were rated very high (). Module 3 was rated best with 74% “very good” (2.8% missing data). The lowest rating was given to module 2, which still was rated very good by 64% (3.7% missing data). When comparing the ratings of “very good” versus “other” of module 1–4, females rated “very good” more often in all modules (Module1: OR 1.4; CI 1.2–1.7; Module 2: OR 1.5; CI 1.2–1.8; Module 3: OR 1.4; CI 1.2–1.7; Module 4: OR 1.3; CI 1.1–1.6). The rating “very good” was equal between participants under 65 years of age compared to 65 years and older in module 2 and 4 (Module 2: OR 1.3; CI 1.0–1.3; Module 4: 1.1; CI 0.9–1.3), while participants under 65 years of age rated “very good” more often in module 1 and 3 (Module 1: OR 1.2; CI 1.1–1.4; Module 3: OR 1.4; CI 1.2–1.6). There was no significant difference in the rating of “very good” between participants with and without medical education (Module 1: OR 1.1; CI 0.9–1.3; Module 2: OR 0.9; CI 0.8.–1.2; Module 3: 1.0; CI 0.8–1.3; Module 4: 1.0; CI 0.8–1.3).

Results of the qualitative data

In the qualitative data from the open questions five major themes could be found and will be described below. The informant’s quotes include information on age, gender and profession.

Atmosphere and surroundings

Many participants describe the atmosphere as nice and comfortable. Many appreciate the open discussions of instructors’ and participants’ personal experiences. Others like the somehow relaxed approach to death and dying. Although most participants meet for the first time, most of them have no problem talking openly about death and dying in the group. Some describe a climate of trust and openness:

Today we were a big family. Female, 49, cleaning woman

(2) The instructors

The instructors are very often described as open and competent. The participants like their easy-to-understand explanations and their willingness to answer questions. Many informants appreciate the use of case stories from the instructors lived experience.

Everything was explained understandably, the case stories and the personal experiences of both instructors and participants. Female, 56, naturopath

(3) Course content

Most participants write that almost all of their questions about end-of-life care and death are answered. In general, participants appreciate the course format and duration. A few participants want an extended course with more teaching lessons.

Everything was interesting and important. Female, 34, nurse

All questions were answered. Male, 22, non-medical profession

(4) Effects of the course on the participants’ feelings or views

The participants’ feedback is very positive in general. Most participants appreciate both information about palliative care and the discussions about life and death.

I am now able to talk more relaxed about death and dying. Female, 46, nurse assistant

The course made me more self-assured. Female, 55, office worker

Participants are reassured that death belongs to life.

To acknowledge the normality of death – death is a normal part of life. Male, 65

(5) Suggestions for improvement.

Few participants share suggestions for improvement. These are about expanding some of the topics (for e.g. advance care planning), a handout to take home or the suggestion to teach Last Aid in schools. Some express the importance of time-keeping and providing opportunities for everybody to engage in the discussions.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first international multi-centre study using a standardized public palliative care education program for citizens in different countries in many training centers run by different organizations. The main findings are: The Last Aid Course is feasible on a large scale and very well accepted by the participants. The contents are perceived easy to understand. Almost all participants would recommend the course to others. Findings from the qualitative data revealed that participants find the atmosphere comfortable; instructors competent; appreciate the course format, duration, topics and discussions about life and death. The combined results from quantitative and qualitative data show that public palliative care education can be delivered using the Last Aid Course format in a very short time frame within four teaching hours on a single day.

It is known that an awareness of palliative care and knowledge about end-of-life care is lacking in the public,Citation8,Citation12–15 thus indicating a need for information about end-of-life care on the population level. Education to enhance knowledge and skills of family caregivers has been recommended as part of a public health strategy for palliative careCitation26 but international programs to achieve this have until now been absent. The World Health Organisation and the Vatican recommend public awareness campaigns and education to improve palliative care worldwide.Citation27,Citation28 The results presented above show that the Last Aid Course is a feasible and an acceptable option for raising awareness and teaching the public about palliative care. Furthermore, the data show that people appreciate talking about death and dying in an open atmosphere. The Last Aid Course informs the public within merely four teaching hours.Citation7,Citation9 According to Ferris et al., education should be as short as possible: “ … focus on what they need to know in the shortest time possible – ruthlessly exclude the extraneous.”Citation29 Most participants had no further questions after the course indicating that the content is suitable. So far, no other studies on public palliative care education have been performed, in such a large scale using multiple education centers in different countries before. In addition to transferring knowledge, the course provides a forum for reflection of participants’ attitudes and experiences with death and end-of-life care. The results from the pilot courses indicated participants’ preferences for module 3 with the main topic of relieving suffering and practical Last Aid measures.Citation9,Citation11 The current data show only a minimal higher preference for module 3 by the participants. Thus, the data indicate that most people appreciate the current modules as they are. A pilot study from a university hospital indicated that medical staff would like Last Aid Courses with an extended curriculum in order to meet their learning goals.Citation30 In the current data there is no difference between participants with and without medical education. It is interesting that participants’ often where women (88%) and the majority was middle-aged or elder. This may reflect the fact that the majority of spousal caregivers are women.Citation31 Probably more men should be encouraged to participate in Last Aid Courses. The results from the qualitative data show that most important areas are covered from the participants’ views. It is interesting that some participants described that they felt more self-assured and prepared to participate in end-of-life care after participation. This was also shown in a educational intervention on end-of-life care, which changed beliefs regarding end-of-life care at home.Citation32 Thus, education of the public may contribute to increasing awareness of palliative care and reducing existing misconceptions amongst the public.Citation13 Reflections on death and dying are encouraged during the Last Aid Course. The current study does not include information about racial or ethnic background of the participants. As cultural competence is important for health care providers and language barriers need to be addressed,Citation33,Citation34 future studies should thus include information about race and ethic background. Refugees palliative care needs should also be addressed.Citation35,Citation36 Last Aid Courses may contribute to create a more expansive and inclusive ‘compassionate communites’ by addressing their needs and cultural perspectives and to raise public awareness about the topic.

Implications for practice

The Last Aid Course has a huge potential to enhance public discussion about death and dying. One might assume that the course would help to empower people to engage in palliative care provision at home, and thus, increase the number of home deaths.

The implementation of Last Aid courses can increase the public knowledge about palliative care and may contribute to improved palliative care at home. Community participation is crucial and should be based on the recognition of palliative care as everbody’s business, respecting diversity and inclusion, motivating citizens plus participation of local groups and projects with non-hierarchical systems as a bottom-up approach of public palliative health care in the community.Citation5,Citation6,Citation37,Citation38 The Last Aid Course could help to prepare citizens to provide end-of-life care, and might, thus, help to empower them and reduce the strain experienced in caring. With limited resources and lack of trained professionals, this has a major impact on making end-of-life care provision possible at home in the future. As Last Aid Courses may contribute to the development of personal skills and strengthening community action an annual World Last Aid Day has been proposed.Citation39 Further studies are needed to address the long-term effects of the course on the ability and willingness of participants to provide palliative care and end-of-life care and the possible impact on the number of home-deaths. An international Last Aid Research Group Europe (LARGE) has been established in 2019. Research on Last Aid is ongoing in different countries.

Strengths and limitations

A major strength of the study is the high number of participants from a variety of regions, small towns and big cities in the three different countries, the high percentage of Last Aid Course participants (91%) who were willing to give their feedback and the sampling from many courses led by a large number of different instructors. A limitation could be selection bias since all informants chose to participate in a course on that topic. Also missing data (as shown in the results) could be a limitation. The fact that informants were asked about their opinion directly after the course limits recall bias, but does not provide information about the impact of the course on the provision of end-of-life care. Using a mixed-methods approach has lead to a richer picture of the participants’ experiences and can be seen as strength. Integrating both methods has provided a broader view of the participants’ opinions and leads to a deeper understanding of the topic.

Conclusions

The results from the current study show that Last Aid Courses are both feasible and accepted by citizens. They have a huge potential to inform citizens about palliative care and to encourage them to engage in end-of-life care at home. More research on the effects of Last Aid Courses is needed. Future research should aim to investigate the long-term effects of the course on the ability and willingness of participants to provide end-of-life care, a possible impact on the levels of community participation, the number of home-deaths and the cultural and socio-economic aspects of end-of-life care in different communities.

Disclaimer statements

Contributors The original study conception was by GB. GB was responsible for data acquisition. All authors participated in the analysis of the quantitative and qualitative data. All authors critically revised the manuscript and approved the submitted manuscript.

Funding The present research has been performed without external funding.

Conflict of interest GB might have potential conflicts of interest. GB receives financial compensation for giving Last Aid instructor courses. GB holds a trademark Last Aid. FB and DLW have no competing interests.

Ethical considerations and ethics approval The presented study follows the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. As participation in the study merely required filling in a questionnaire after participation in a Last Aid Course, no formal approval by an ethics committee was required. The study was reported to the regional ethics committee of Southern Denmark, which concluded that no formal application was required (The Regional Committees on Health Research Ethics for Southern Denmark; Nr. 20182000-33). All participants gave their informed consent to participate. No personal data other than gender, age and profession were collected.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for all help and support by all Last Aid Course instructors who conducted the courses and who asked the course participants to complete a questionnaire about the course. Many thanks to all Last Aid Course participants who volunteered to participate in the study.

References

- Ferri CP, Prince M, Brayne C, Brodaty H, Fratiglioni L, Ganguli M, Hall K, Hasegawa K, Hendrie H, Huang Y, Jorm A, Mathers C, Menezes PR, Rimmer E, Scazufca M. Alzheimer’s disease international. Global prevalence of dementia: a Delphi consensus study. Lancet 2005;366:2112–7.

- Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet 2013;381:752–62.

- Ewing G, Austin L, Jones D, Grande G. Who cares for the carers at hospital discharge at the end of life? A qualitative study of current practice in discharge planning and the potential value of using the carer support needs assessment tool (CSNAT) approach. Palliat Med 2018;32(5):939–49.

- Etkind N, Bone AE, Gomes B, Lovell N, Evans CJ, Higginson IJ, Murtagh FEM. How many people will need palliative care in 2040? Past trends, future projections and implications for services. BMC Med 2017;15:102.

- Kellehear A. Compassionate communities: end-of-life care as everyone’s responsibility. QJ Med 2013;106:1071–5.

- Kellehear A. Compassionate cities. Public health and end-of-life care. Oxfordshire: Routledge; 2005.

- Bollig G. Palliative care für alte und demente Menschen lernen und lehren. Berlin: LIT-Verlag; 2010.

- Singer PA, Wolfson M. The best places to die. BMJ 2003;327:173–4.

- Bollig G, Kuklau N. Der Letzte Hilfe Kurs – ein Angebot zur Verbesserung der allgemeinen ambulanten Palliativversorgung durch Information und Befähigung von Bürgerinnen und Bürgern. Z Palliativmed 2015;16:210–6.

- Bollig G, Heller A, Völkel M. Letzte Hilfe – Umsorgen von schwer erkrankten und sterbenden Menschen am Lebensende. Esslingen: der hospiz verlag; 2016.

- Bollig G, Heller A. The last aid course – a simple and effective concept to teach the public about palliative care and to enhance the public discussion about death and dying. Austin Palliat Care 2016;1(2):1010.

- McIlfatrick S, Hasson F, McLaughlin D, Johnston G, Roulston A, Rutherford L, Noble H, Kelly S, Craig A, Kernohan WG. Public awareness and attitudes toward palliative care in Northern Ireland. BMC Palliat Care 2013;12:34.

- Shalev A, Phongtankuel V, Kozlov E, Johnson Shen M, Adelman RD, Reid MC MD. Awareness and misperceptions of hospice and palliative care: a population-based survey study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2018;35(3):431–9.

- Westerlund C, Tishelman C, Benkel I, Fürst CJ, Molander U, Rasmussen BH, Sauter S, Lindqvist O. Public awareness of palliative care in Sweden. Scandinavian J Pub Health 2018;46:478–87.

- Patel P, Lyons L. Examining the knowledge, awareness, and perceptions of palliative care in the general public over time: a scpoing literature review. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2019;Nov 5:1049909119885899, doi:10.1177/1049909119885899.

- Bollig G. The Last Aid course – teaching the public about palliative care. lecture 21st international congress on palliative care Montréal, Canada Oct. 2016. JPSM 2016;52(6):e35, doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.10.100.

- Bollig G. The ‘Last Aid’ course – an approach to promoting public discussion, awareness and education. SPPC annual conference 2017: making the best of hard times; Sep 2017; Edinburgh. [cited 2020 Mar 4]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0mAAIXH2xPY.

- Neergaard MA, Olesen F, Andersen RS, Sondergaard J. Qualitative description – the poor cousin of health research? BMC Med Res Methodol 2009;9:52.

- Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health 2000;23:334–40.

- Sandelowski M. What’s in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Res Nurs Health 2010;33:77–84.

- O’Cathain A, Murphy E, Nicholl J. The quality of mixed methods studies in health services research. J Health Serv Res Policy 2008;13(2):92–8.

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health 2007;19(6):349–57.

- EQUATOR network. [cited 2020 Mar 4]. Available from: https://www.equator-network.org/?post_type=eq_guidelines&eq_guidelines_study_design=mixed-methods-studies&eq_guidelines_clinical_specialty=public-health-5&eq_guidelines_report_section=0&s=+&btn_submit=Search+Reporting+Guidelines.

- Malterud K. Kvalitative metoder I medisinsk forskning. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget; 2003.

- Last Aid International. [cited 2020 Mar 4]. Available from: www.lastaid.info.

- Stjernswärd J, Foley KM, Ferris FD. The public health strategy for palliative care. JPSM 2007;33:486–93.

- Centeno C, Sitte T, De Lima L, Alsirafy S, Bruera E, Callaway M, Foley K, Luyirika E, Mosoiu D, Pettus K, Puchalsky C, Rajogapal MR, Yong JS, Garralda E, Rhee JY, Comoretto N. White paper for global palliative care advocacy: recommendations from the PAL-LIFE expert advisory group of the pontifical. Vatican City: Academy for Life; 2018.

- World Health Organization. Planning and implementing palliative care services: a guide for program managers; 2016. [cited 2020 Mar 4]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications-detail/planning-and-implementing-palliative-care-services-a-guide-for-programme-managers.

- Ferris FD, von Gunten CF, Emanuel L. Knowledge: insufficient for change. J Palliat Med 2001;4:145–7.

- Mueller E, Bollig G, Boehlke C. Lessons learned from introducing ‘Last-Aid’ courses at a university hospital in Germany. Posterpresentation 16th EAPC World Congress Berlin, Germany; 2019 May 23–25.

- Ornstein KA, Wolff JL, Bollens-Lund E, Rahman OK, Kelley AS. Spousal caregivers are caregiving alone in the last years of life. Health Aff 2019;38(6):964–72.

- Miyashita M, Sato K, Morita T, Suzuki M. Effect of a population-based educational intervention focusing on end-of-life home care, life-prolonging treatment and knowledge about palliative care. Palliat Med 2008;22(4):376–82.

- Nielsen LS, Angus JE, Howell D, Husain A, Gastaldo D. Patient-centered care or cultural competence: negotiating palliative care at home for chinese canadian immigrants. Am J Hos Palliat Med 2015;32(4):372–9.

- Gunaratnam YY. Death and the migrant: bodies, borders, care. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013.

- Marston J, De Lima L, Powell RA. Palliative care in complex humanitarian crisis responses. The Lancet 2015;386(14):1940.

- Madi F, Ismail H, Fouad FM, Kerbage H, Zaman S, Jayawickrama J, Sibai AM. Death, dying, and end-of-life experiences among refugees: a scoping review. J Palliat Care 2019;34(2):139–44.

- Rosenberg JP, Horsfall D, Sallnow L, Gott M. Power, privilege and provocation: public health palliative care today. Prog Palliat Care 2020;28(2):75–7.

- Kumar S. Community participation in palliative care: reflections from the ground. Prog Palliat Care 2020;28(2):83–8.

- Mills J, Rosenberg JP, Bollig G, Haberecht J. Last Aid and public health palliative care: towards the development of personal skills and strengthened community action. Prog Palliat Care 2020;28(6):343–5.