Abstract

This article charts the learning from an online, artmaking programme supporting individuals with a life-limiting illness. The programme sought to fill a gap caused by the temporary closure of face-to-face UK hospice-based day therapy programmes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Participants’ comments on this arts-based programme illustrated the sense of disrupted and diminished identity, linked to a deceased sense of agency, which terminal illness can bring. Responding to this need for increased agency led to the development of the PATCH (Palliative care patient-led change) programme. Individuals with a terminal illness will be invited to join an online collaborative group, to identify a specific issue they wish to address and to lead the change they wish to see. The PATCH group will be supported by a facilitator and a team of volunteers, whose roles will include supporting participants in planning and executing their change strategy. This article presents the conceptual underpinning for the PATCH programme, offering a tentative theory of the relationship between identity, moral purpose, agency, illness and the leadership of change for those living with a life-limiting illness. Challenging stereotypical views of palliative care patients, it explores a new community and asset-based approach to end-of-life care which supports individuals at the end of life in developing a positive self-view.

Introduction

The arrival of the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic magnified an accepted need to develop innovative ways of providing palliative care.Citation1 Frontline UK support for those living with a terminal illness was severely reduced, with the mass temporary closure of hospice-based, face-to-face well-being services. Patients found themselves lacking their usual interventions for the ‘total pain’, the physical, mental, social and spiritual suffering which many experience at the end of life.Citation2, p. 45 Facing this unexpected service gap, I developed Live well, die well, an arts-based, online support programme for individuals with a life-limiting illness which I offered until services resumed. Participant evaluation surfaced the sense of disrupted and diminished identity which terminal illness can bring,Citation3 apparently linked to a decreased sense of agency. Following Bandura,Citation4 I use agency to mean the ability to make a difference to one’s own life and that of others. Having experienced programmes where increased agency results from individuals leading change in an area they care about,Citation5 I wondered if I could develop a similar intervention programme for the terminally ill.

Exploring key concepts

An exploration of emerging key concepts helped to move my thinking forward.

Identity

I use identity to mean ‘the kind of person one is recognised as being, at a given time and place’.Citation6 Participants supported Erikson’sCitation7 view of identity as a process of development, of identification, rather than a fixed, life-long state. The self exists not in isolation but in the social world, where it is constantly re-formed by actions and interactions with others. This explains the social death some terminally-ill people experience,Citation8 with affinity patterns fractured by illness trajectories. Patients’ sense of harmony with their self-imageCitation9 can also be negatively impacted. The ability to lead normal and productive lives, that is, to maintain a sense of agency, appears vital in restoring a positive self-view. The term ‘agency’ is rare in palliative care literature, whilst ‘empowerment’, although conceptually distinct, dominates.

Empowerment and agency

Empowerment is defined by World Health Organsiation (WHO) as ‘a process through which people gain greater control over decisions and actions affecting their health’.Citation10 However, Wakefield et al.’s literature reviewCitation11 found little evidence of such empowering activity amongst those with life limiting illness. Moreover, empowerment can be negatively associated with power differentials when enacted by professionals, the ‘knowing subjects’, whilst patients remain the ‘objects’ of the medical ‘gaze’.Citation12, p. 137 An exploration of the concept of agency is potentially more fruitful.

Differently explained by social theorists, I use agency to mean human beings’ ability to act to change something.Citation13 For example, a patient may choose to develop a leaflet which suggests ways of talking with family about impending death, thus having a role in changing the dying discourse. However, individuals do not always have free rein to act as they wish. Instead, they are constrained by structures,Citation13 societal arrangements or dominant ways of thinking which arise from and influence individual action. A patient may be able to develop a leaflet but may not be able to persuade clinicians of its value or access information needed for distribution. They can give the leaflet to people they know but in reality their agency is compromised. Here, structure and agency are imagined as oppositional – structures prevent individuals from effecting desired change. However, we can also draw on structures to support our actions.Citation14 Archer’sCitation15 discussion of ‘the internal conversation’ – the self-talk which helps individuals establish a course of action – illustrates how the relationship between structure and agency can be managed to increase individuals’ control over their lives.

A critique of this perspective might focus on the responsibility placed on vulnerable individuals to chart their own course in a complex medical environment. A patient may not be to influence the nature of clinical consultations, for example, where timing, length of consultation and questions asked are pre-determined. However, in situations where patients can set the change agenda, much can be achieved. This feeling of playing an active part in shaping own’s own world and that of others is key to human flourishing.Citation16 MaslowCitation17, p. 382 conceptualizes this flourishing as self-actualization, the fulfilment of human potential, proclaiming, ‘What a man can be, he must be’. Saunders’Citation18 resolve that a man should be enabled to be himself at the end of life echoes this determination for human fulfilment. Self-actualization could be achieved through individuals with a terminal diagnosis influencing palliative care policy and practice. This is currently assumed to be achieved through patient and public involvement (PPI) in research.

Patient and public involvement in research (PPI)

PPI initiatives sit on a continuum running from consultation, where patients are asked their views but given no role in decision-making, through collaboration, where patients work as active partners in a project team, to control, where patients design, undertake and disseminate the results of a project.Citation19 Patient involvement at the consultation end the continuum dominates, with many positioned as data-providers or partners, working to pre-set academic or industry agendas.Citation20 It is challenging to assert that this satisfies the principle that people who are affected by research have a right to have a say in what and how research is undertaken.Citation21

Collaborative approaches to PPI, at the centre of the continuum, challenge this restricted view, constructing patients as collaborative partners and reviewing traditional, qualification-based power relations.Citation22 Researchers move from being producers of findings and recommendations to facilitators of agential action with or by patients,Citation23 in project teams underpinned by principles of democracy and mutuality. The legitimacy which patients’ lived experience, occupational knowledge and skills can bring is valued and drawn upon.Citation24 Participatory action research, for example, offers patients the opportunity to work as co-producers, contributing to agenda setting, service improvement and social changeCitation25 whilst experience-based co-design prioritizes team members’ equal involvement in change activities.Citation26

At the far end of the continuum, user-led/controlled research offers patients the opportunity to improve their own lives and contribute to wider social and political change.Citation27 Here, research is actively controlled by service users, who may also decide to carry out the research themselves.Citation27 Whilst not all user-led research offers service-users wholescale control,Citation28 adhering to the principles of such research – inclusivity, power-sharing, valuing all, reciprosity and relationship building – ensures it fulfils its emancipatory aim.

Unfortunately, there is a reluctance to involve palliative care patients in such research, perhaps due to a lack of confidence about appropriate approaches for this group.Citation29 Given the challenges of a life-limiting illness, it may seem unnecessary and impractical to move beyond such initiatives as the palliative and end of life care priority setting partnership, which included patients in identifying and prioritizing gaps in current research evidence.Citation30 Indeed, palliative care patients are often seen as too sick and having too little energy to contribute meaningfully to more active research practices.Citation31 However, the marginalization and diminishing sense of agency which a terminal diagnosis can bring demands a more fundamental re-interpretation of appropriate research roles. A consideration of the nature of research is helpful here.

Research and development work

Research can be conceptualized both as the pursuit and production of pure knowledge and as learning with an applied purpose. Pure or basic research is exploratory in nature, motivated by interest, intuition and the desire to develop Mode 1 or scientific knowledge.Citation32 Applied research, alternatively, explores potential solutions to everyday practical problems. It may, for example, lead to a cure for an illness or the development of technologies and to Mode 2 knowledge, with its dialogic, social and application orientation.Citation32 The quest for findings, which someone else will then act on, dominates research. An alternative approach to knowledge development and practice change is development work, ‘strategic, focused and deliberate action, intended to bring about improvements in professional practice’,Citation33, p. 86 arising from an individual’s moral purpose.

Although there is a developing recognition in the health service of the need to empower all staff to lead improvement, this impetus does not seem to include patients.Citation34 The adoption of an asset-based approach may reverse this trend however. The term asset-based approach describes community building, focusing on the assets, skills and capacities of individuals, rather than needs and deficits.Citation35 Here, leadership is undertaken by the many, acting together for changeCitation36 and through such action, being empowered and empowering others.Citation35 Case study evidence of using this approach in palliative care development is encouraging.Citation37 The leadership of development work appears to align with this asset-based approach, offering greater possibilities for individual agency than involvement in research.

A conceptual framework

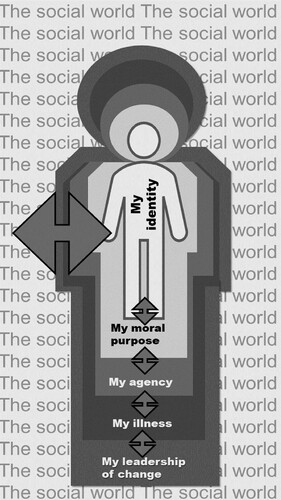

The exploration of concepts above led to the development of this conceptual framework which will be used underpin the development of the palliative care patient-led change (PATCH) programme ().

The framework reader should start from the individual at the centre and move outwards towards the social world in which they sit. Our identity, at the heart of each individual, is unique and shifts over time. Our moral purpose encases our identity, is shaped like it and holds it in place. Thus we do things which support our sense of self and do not do things which challenge it. The two-headed arrows in the framework indicate this mutual influence.

Moral purpose is both nourished by and nourishes the individual’s sense of self. This moral purpose is also a catalyst for our agency – we see something we do not like and are compelled to act to change it. Our illness sits outside of these core features of what makes us the human being we recognize. Illness acts on agency, potentially reducing it, yet agency can also impact on illness, reducing its power to disrupt our identity. Our identity, moral purpose, agency, and health all impact on our ability to lead change. However, our leadership of change equally impacts on these human features, potentially shoring them up and giving us a renewed sense of positive self. We live in a social world in which structures either support or inhibit agential action, where the self is constantly reformed by interactions with others. We must act within this world, and thus change it, to fulfil our moral purpose and develop an identity we both recognize and embrace.

Conclusion

This proposed pattern of connections has been used to shape the general outline of the PATCH programme. Individuals with a life limiting illness will be invited to join a facilitated online group, to identify a specific issue they wish to address and to take action which leads to change. However, the centrality of the individual’s need for agency, and the honouring of their moral purpose, means the details of this model of patient-led change cannot be set in advance but will be developed collaboratively by a PATCH development team, comprising potential participants, clinicians, facilitators and academics.

It could be argued that individuals with a life-limiting illness have enough challenges without engaging in change leadership. However, the insight, wisdom and creativity which comes from patientsCitation38 is needed to enhance service-development. Wohleber et al.’sCitation31 systematic review underlines palliative care patients’ enthusiasm for involvement, with motivational factors including the opportunity to help others, improve their own well-being, and meet those in a similar situation. Adherence to the ‘Declaration of Helsinki’ set of ethical principles, adopted by the World Medical Association,Citation39 would ensure the prioritization of participant wellbeing.

The need to increase the reach of palliative care through a community-led approachCitation40 is long acknowledged. However, the imperative is now urgent, due to the acknowledged difficulties of sustaining a healthcare model focused on disease management. Instead, the NHS is urged to become part of a larger, ‘upstream-focused, health and resilience support system’.Citation41 Facilitating palliative care patients to be part of this solution challenges stereotypical views of the dying, enabling individuals to change things around them and, perhaps, themselves. This asset-based approach to individual and societal change underpins the PATCH programme and will continue to guide the development of its principles and practice.

Disclaimer statements

Contributors None.

Conflicts of interest None.

Ethics approval None.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Amanda Roberts

Following a career in secondary school education, Amanda Roberts has held a variety of roles at the University of Hertfordshire, developing her expertise in diverse areas such as quality assurance and curriculum design. A period of volunteering in a local hospice led to a new interest in palliative care. Her recent research explores how to support the development of agential leadership and positive self-image in those with a life-limiting illness.

References

- Byock I. Completing the continuum of cancer care: integrating life-prolongation and palliation. CA Cancer J Clin 2000;50(2):123–32.

- Saunders C, Baines M, Dunlop R. Living with dying. A guide to palliative care. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1995.

- Exley C, Letherby G. Managing a disrupted lifecourse: issues of identity and emotion work. Health 2001;5(1):112–132.

- Bandura A. Human agency in social cognitive theory. Am Psychol 1989;44(9):1175–1184.

- Frost D. Teacher-led development work: a methodology for building professional knowledge, HertsCam Occasional Papers, HertsCam Publications; 2013. Available from www.hertscam.org.uk.

- Gee J. Identity as an analytic lens for research in education. Rev Res Educ 2001;25:99–125.

- Erikson E. “Identity crisis” in perspective. In: E Erikson, (ed.) Life history and the historical moment. New York: Norton; 1975.

- Lawton J. The dying process. London: Routledge; 2000.

- Carlander I, Ternestedt M, Sahlberg-Blom E, Hellström I, Sandberg J. Four aspects of self-image close to death at home. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being 2011;6(2):5931. [cited 2021 May 5]. Available from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10. 3402/qhw.v6i2.5931.

- World Health Organisation (WHO). WHO guidelines on hand hygiene in health care: first global patient safety challenge. Clean care is safer care; 2009 [cited 2021 Feb 20]. Available from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK144022/.

- Wakefield D, Bayly J, Selman L, Firth A, Higginson I, Murtagh F. Patient empowerment, what does it mean for adults in the advanced stages of a life-limiting illness: A systematic review using critical interpretive synthesis. Palliat Med 2018;32(8):1288–1304.

- Foucault M. The birth of the clinic: an archeology of medical perception. New York: Random House; 1973.

- Giddens A. The constitution of society. Cambridge: Polity Press; 1984.

- Bourdieu P. The forms of capital. In: J Richardson (ed.) Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education. New York: Greenwood; 1986. p. 241–58.

- Archer M. Structure, agency and the internal conversation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2003.

- McArthur J. Reconsidering the social and economic purposes of higher education. High Educ Res Dev 2011;30(6):737–749.

- Maslow A. A theory of human motivation. Psychol Rev 1943;50:370–396.

- Saunders C. Watch with me. Inspiration for a life in hospice care. Lancaster: Observatory Publications; 2005.

- Merrow E, Cotterell P, Robert G, Grocott P, Ross F. Mechanisms can help to use patients’ experiences of chronic disease in research and practice: an interpretive synthesis. J Clin Epidemiol 2013;66:856–864.

- Mader LB, Harris T, Kläger S, Wilkinson IB, Hiemstral TF. Inverting the patient involvement paradigm: defining patient led research. Res Involv Engagem 2018;4:21–28.

- National Institute for Health Care Excellence (NICE). Patient and public involvement policy; 2013 [cited 2021 Feb 25]. Patient and public involvement policy | Public Involvement Programme | Public involvement | NICE and the public | NICE Communities | About | NICE.

- Beresford P. From ‘other’ to involved: user involvement in research: an emerging paradigm. Nordic Soc Work Res 2013;3(2):139–148.

- Willis P, Almack K, Hafford-Letchfield T, Simpson P, Billings B, Mall N. Turning the co-production corner: methodological reflections from an action research project to promote LGBT inclusion in care homes for older people. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15(4):695.

- Barker J, Moule P, Evans D, Phillips W, Leggett N. Developing a typology of the roles public contributors undertake to establish legitimacy: a longitudinal spaces study of patient and public involvement in a health network. BMJ Open 2020 [cited 2021 Feb 24]. Available from https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/10/5e033370.

- Etgar M. A descriptive model of the consumer co-production process. J Acad Mark Sci 2008;36:97–108.

- Blackwell R, Lowton K, Robert G, Grudzen C, Grocott P. Using experience-based codesign with older patients, their families and staff to improve palliative care experiences in the emergency department: A reflective critique on the process and outcomes. Int J Nurs Stud 2017;68:83–94.

- Turner M, Beresford P. User controlled research: its meanings and potential; 2005 [cited 2021 Feb 25]. Available from https://www.invo.org.uk/posttypepublication/user-controlled-research-its-meanings-and-potential/

- Faulkner A. Changing our worlds: examples of user-controlled research in action; 2010 [cited 2021 Jan 20]. Available from www.invo.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/involvechangingourworlds2010pdf

- Johnson H, Ogden M, Brighton LJ, Etkind SN, Oluyase AO, Chukwusa E, Yu P, de Wolf-Linder S, Smith P, Baliey S, Koffman J, Evans CJ. Patient and public involvement in palliative care research: what works, and why? A qualitative evaluation. Palliat Med 2021;35(1):151–160.

- Higginson I. Research challenges in palliative and end of life care. BMJ 2016 [cited 2021 Jan 20]. Available from https://spcare.bmj.com/content/bmjspcare/6/1/2.full.pdf.

- Wohleber AM, McKitrick DS, David SE. Designing research with hospice and palliative care populations. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 2012;29(5):335–345.

- Nowotny H, Scott P, Gibbons M. ‘Mode 2’ revisited: the new production of knowledge. Minerva 2003;41:179–194.

- Frost D, Ball S, Hill V, Lightfoot S. Teachers as agents of change: a masters programme taught by teachers. Letchworth: HertsCam Publications; 2018.

- Quality Care Commission. Driving improvement. Case studies from eight NHS trusts. Newcastle Upon Tyne: Quality Care Commission; 2017.

- Mathie A. From clients to citizens: asset-based community development as a strategy for community-driven development. Coady International Institute, Occasional Paper Series, No. 4; 2002.

- Rippon S, Hopkins T. Head, hands and heart: asset-based approaches in health care. London: The Health Foundation; 2015.

- Freeman G. Developing an asset based approach within a learning community – using end of life care as an example; 2017 [cited 2021 May 11]. Available from http://endoflifecareambitions.or.uk.

- Robert G, Cornwall J, Locock L, Purushotham A. Patients and staff as codesigners of healthcare services. BMJ 2015 [cited 2021 Feb 25]. Available from https://www.bmj.com/content/350/bmj.g.7714.

- World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects; 2013 [cited 2021 Mar 2]. Available from https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/.

- Kellehear A. Compassionate communities: end-of-life care as everyone’s responsibility. QJM 2013;106:1071–1075.

- Verkerk R. A blueprint for health system sustainability in the UK. Dorking: Alliance for Natural Health International; 2018.