Abstract

Background

Informal carers of someone with a life-limiting or terminal illness often experience marked levels of depression, anxiety and stress. Carers have limited free time to devote to lengthy, well-being interventions. Carers also struggle to prioritize their self-care, a factor which may help buffer some of the negative impacts of being a carer. The aim of this study was to gain insight into carers’ views and perceptions of a brief, four session face to face self-compassion intervention for carers (iCare) which was created to improve well-being, increase self-compassion and develop self-care among carers. In so doing, this qualitative research addresses gaps in the literature relating to self-compassion interventions for carers and targeted self-care initiatives for carers.

Method

Semi-structured interviews with nine participants of iCare were conducted and data subjected to a reflexive thematic analysis within a critical realist framework.

Findings

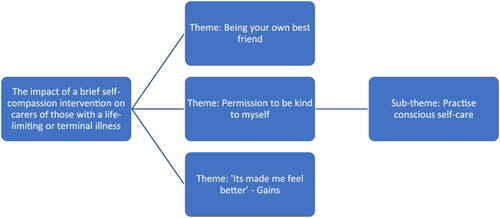

A number of themes and sub-themes were identified. Carers discovered a kinder, less judgemental way of seeing themselves allowing themselves to recognize that they had their own individual needs. In turn this led to an intentional practise of self-care activities. Benefits from conscious self-care and self-kindness included experiencing a greater sense of calm or relaxation and the development of a more positive outlook.

Conclusion

The findings highlight that a brief self-compassion intervention can have a positive impact on carers reported well-being through developing a kindlier internal orientation and locating a permission to allow themselves to practise an intentional self-care.

Introduction

Hospice UKCitation1 states that the UK hospice sector supports more than 200,000 people with life-limiting or terminal conditions each year. Each person is likely to be supported by a friend or family member acting as a carer providing physical, emotional and/or financial support, unpaid. For the purposes of this article such a carer is called a ‘Carer’ (capitalized ‘c’) to distinguish from unpaid carers of the frail elderly, those with a chronic illness or disability or professional caregiver.

Caring for someone with a life-limiting illness generally incurs various financial costs (e.g. higher heating costs, travel costs attending medical appointments) as well as other less quantifiable costs. These may include clinical levels of depression, anxiety and stress as well as experiencing reduced physical health compared with non-Carers.Citation2 Despite the growth in interventions to support Carers and the creation of tools to assess Carer needs in palliative care e.g.Citation3 the needs of family Carers are generally given insufficient attention and yet Carers appear to have a strikingly high number of unmet needs.Citation4 Limited research suggests that Carers show evidence of burnout and that increasing self-care practices may reduce Carer burden, lower stress, anxiety, depression and improve mental health.Citation5,Citation6 Self-care can be defined as a multifaceted engagement in activities or behaviours with the aim of enhancing functioning and wellbeing.Citation7 Within the palliative care field, the recent literature is more concerned with researching the self-care strategies, practices and training interventions for healthcare professionals e.g.Citation8–10 Carer self-care is under-researched which is disappointing given the potential improving self-care may have for buffering against some of the negative effects of caregiving. Over 10 years ago it was noted that there were few interventions that focused on Carers’ self-care and more research was called for.Citation11 This call for further research appears to have gone unheeded as in the specific domain of Carers, as defined in this article, there are, at the time of writing, no interventions specifically focused on developing Carer self-care.

Self-compassion entails becoming our ‘own best friend’, bringing kindness to ourselves when we are suffering. To date the research indicates that developing self-compassion as part of resource building has an inverse relationship to psychological distress,Citation12 is associated with lower levels of mental health symptoms such as depression and stressCitation13,Citation14 and is negatively related to caregiver burden.Citation15 Self-compassion may also predict levels of self-care.Citation16 Self-compassion may benefit Carers in term of improving their psychological functioning and overall well-being. There are a number of compassion building therapies and programmes; the most well-known is the Mindful Self-Compassion (MSC) programmeCitation17 based on Neff’s operationalization of self-compassion.Citation18 This is an eight-session weekly group programme (2.5 h per session), plus a half-day retreat. Participation in the MSC programme is too time-consuming for already time-pressed Carers who may struggle to leave their Caree (the person they care for) for substantial periods of time. Hence a brief four session face to face self-compassion intervention tailored to address Carers was developed (‘iCare’).

Method

The aim of this study was to gain insight into Carers’ views and perceptions of iCare which was created to improve well-being, increase self-compassion and develop self-care among Carers. In so doing, this qualitative research addresses gaps in the literature relating to self-compassion interventions for Carers and targeted self-care initiatives for Carers. The study was advertised in carer organizations, health charities and hospices in the North West of England and North Wales. It was further advertised using Twitter, LinkedIn and on the home page of the first author’s web site. Nine participants were recruited who met the research criteria of being aged 18 or over; caring for an adult with a life-limiting or terminal diagnosis; who were sufficiently fluent in English to understand the material being delivered; and who were able to participate in an interview. As this study, part of a larger study, was designed to provide a theoretical justification for a brief online self-compassion intervention, a pragmatic approach to recruitment and sample size was adopted.Citation19,Citation20 This enabled the delivery of the 36 h of iCare plus interviews with the participants to be accommodated within the overall project plan. It was considered that nine participants would provide sufficiently rich data.

Ethical approval to the study was granted by the Department of Social and Political Science Ethics Committee of the University of Chester.

Participants

Participants were nine white British females aged between 38 and 78 (M = 58) caring for Carees with a variety of illnesses including motor neurone disease, end stage cancer and dementia. The mean length of time the Caree had been diagnosed and thus the assumed period of caring was approximately five years and eight months.

Intervention

The iCare intervention comprised four one-hourly sessions delivered over four weeks, one to one to individual participants. The first author acted as facilitator, guiding practices and meditations together with offering brief theoretical explanations. iCare was influenced by the content of the MSC programmeCitation17 but adapted to meet the needs of Carers. details the content of the individual iCare sessions. Supporting material consisted of two CDs with recordings of meditations and practices and printed handouts summarizing key points.

Table 1 Content of iCare intervention.

Over the four sessions of iCare, participants were introduced to the ideas of mindful self-compassion through guided meditations and practices; written text and suggestions regarding behavioural changes that could be made in day-to-day life. This was all couched within a warm and supportive delivery. Participants were encouraged to listen to recordings between sessions.

Reflexivity

In keeping with the ethos of reflexive thematic analysis ‘TA’,Citation22 and the importance placed on transparency both of data analysis and analytic lens adopted within the researchCitation23 the following details are offered. The first author has been a Carer several times in her personal life and has extensive experience as a counsellor within the UK hospice movement working with patients, their family and friends and the bereaved. She is also a trained teacher of the MSC programme and has previously offered adapted versions of the MSC programme to hospice staff, patients and Carers. She is a white British heterosexual female. The second author is an experienced practitioner-researcher with many years’ experience of working in statutory mental health settings, including with Carers, and is a white British heterosexual male. He took the role of research supervisor for this study.

Data collection

Depending upon participants’ preferences, iCare was delivered within their homes, in a private room at a hospice, or in the first author’s office. Subsequently, semi-structured interviews were conducted by the first author in similar locations approximately two weeks after the final session of iCare. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. The interview data were analysed using reflexive TACitation22,Citation24 within a critical realist framework.Citation25–28 Critical realism combines ontological realism with epistemological constructivism and interpretivism assuming that while there may be an independent reality this can never be known definitively. The study identified patterns in the participants’ experiences of developing self-compassion and the ways in which this impacted their well-being. The TA was predominantly inductive, ‘staying close’ to participants’ experiences and not driven by any theory other than Neff’s model of self-compassion.Citation18

Findings

The aims of this study were to explore the experience of participants of a brief self-compassion-based self-care programme, iCare. Participants were given pseudonyms to protect their anonymity.

Three themes and one sub-theme were generated from the reflexive TA of the data as shown in .

Participants described how their self-compassion developed as they practised and implemented ideas and suggestions. Participants discovered a kinder, less judgemental way of seeing themselves. Within the data participants reported allowing themselves to recognize that they had their own individual needs (e.g. for rest, time away from caring, more social contact), in effect self-legitimizing their needs. They began to practise self-care in meeting some of these needs. This was done with intentionality and awareness, rather than with a sense of dutiful compliance with exhortations to practice self-care. iCare encourages an inward focus, encouraging participants to ask themselves ‘what do I need right in this moment?' This regular encouragement to turn inwards appears to have brought a greater awareness to the value of self-care. Benefits from the practise of conscious self-care included experiencing a greater sense of calm or relaxation and the development of a more positive outlook. A further exploration of these themes follows.

Theme: being your own best friend

Participants moved through iCare using the meditations and practices together with the didactic teaching and support offered by the first author, acting as facilitator. As they did this, they began to develop their self-compassion. Part of what self-compassionate people do can be described as becoming your own best friend. Offering yourself guidance, loving support and care, particularly during stressful and difficult times. Indeed, this is specifically referred to by Olivia who says ‘So the self-love, self-love and um, it’s all about like being your, being your best friend, isn’t it? That’s how it feels’. Being your own best friend involves turning towards yourself, trusting yourself and having an internal locus of evaluation, such as described by Tamsin ‘I was thinking in terms of for myself, ‘could I handle this situation on my own, am I happy to be here ‘ … ’, rather than deferring to an external third party for approval. In becoming your own best friend though there is also a wise voice, rather than a self-indulgent one – knowing when to exercise, when to eat more healthily and when it is important to prioritize your own needs (e.g. for sleep).

Your best friend is very unlikely to speak negatively and critically to you. Generally, they are supportive and caring and whilst they may offer challenges occasionally, this is done within a loving framework. In contrast, frequently people find that self-talk provides a running, generally negative and critical commentary on how they conduct themselves in day-to-day life. Following participation in iCare, participants noticed changes in their internal monologue or self-talk. Olivia was clear in identifying that she now talked to herself differently post-iCare, in that her self-talk was kinder and more supportive ‘Just to sort of say, you know, ‘don’t beat yourself up on, about this’ or you know, ‘it’ll pass’, that, you know, that sort of thing’. Linda describes how she used to speak critically to herself and whilst she may start to talk this way, she was now able to be more sympathetic and rational in her inner dialogue:

Yeah I think before if it was really getting me down I would say ‘oh you’ve been so stupid, you’ve been this, you’ve been that, you’ve been the other, and sometimes I’ll start with ‘oh what stupid things you did’, and then I’ll think ‘well if I hadn’t have done them I wouldn’t be here’, so it’s done. So, I think that comes a lot quicker and then I think just ‘it’s done, its fine’

I’ve been thinking about it and trying to make myself happy … I’ve said, ‘this is going to be better with [partner] with his stuff and I’m going to join the gym’ and trying to work things out that make me feel better, you know things like that

Theme: ‘Permission to be kind to myself’

Carers struggle to allow themselves time off from their caring responsibilities and do not easily practise self-kindness and self-care. This way of being can be contrasted with people who are more self-compassionate and who are able to give themselves permission to take care of themselves and, when appropriate, to prioritize their own needs. To practise some form of self-care, Carers often look outwardly to others to grant this permission. Such ‘others’ may be family members, friends or healthcare practitioners. Yet the literature points to an inherent struggle in Carers to practise self-care which may explain the levels of anxiety, stress and depression experienced by many Carers.Citation2,Citation4,Citation29

iCare addresses this struggle by explicitly encouraging self-care and self-kindness. Participants seemed initially unable or unwilling to identify that they too had their own needs which required attending to. This is most likely to reflect the wider societal assumption that Carers are unselfish, endlessly giving and fully self-sacrificing. Participation in iCare appears to have changed this. Given that society at large does not seem to encourage self-care and recognition of your own needs as a Carer, it seems to have been a revelation to participants that they themselves could take ownership of their own needs. As participants moved through the intervention, they developed a growing awareness of the acceptability of self-kindness and found an internal permission to be kinder to themselves, as explained by Olivia ‘I know it’s okay … the concept is to be compassionate towards yourself and to be kind towards yourself, erm I just didn’t think of it before, so its brought it into my awareness’. Emily echoed this sense of permission giving ‘it’s as if it’s given me permission to be kind to myself, which has not been something that’s ever really been explicit in there, in my head’. Tamsin highlights the movement from looking outwards for permission to developing an inner permission, as she considered she was ‘giving myself permission to do things’ without needing her wife’s permission ‘And I’ve got the permission … I don’t need [Wife’s] permission to do things’. Beth recognized that she was ‘thinking more, ‘look after yourself more’ you know’.

Olivia powerfully sums up the essence of this theme when she says that iCare is about allowing herself ‘to turn the focus to me rather than the focus to [husband]; it’s all right to focus on me, you know, I have needs’. This is the essence of iCare: encouraging Carers to see that they matter too amid their caring responsibilities, rather than denying that they have needs and feelings. For other participants, a permission to recognize their needs and be kind to themselves appeared to be an internal permission, not explicitly expressed. Rather this inner permission could be inferred from participants’ actions in practising a more conscious, intentional self-care as highlighted in the sub-theme below.

Sub-theme: practise conscious self-care

As participants started to give themselves permission to be kinder to themselves, they began to hear their own needs. Once participants become aware of what they needed they began to allow themselves to meet those needs, as best they could, through acts of self-care. For Karen, her self-care involved ‘pottering in the garden’. Beth was taking three months out of work to think through her options and during this time planned to join a gym because she felt this would give her time out, something she felt she needed. In fact, time out could be as simple as just popping out to the shops, getting away, albeit briefly, from caring responsibilities. This was a need Linda echoed ‘sort of just taking that time out a bit for yourself’ or staying out longer and not feeling the pressure to rush back to be with the Caree.

Other types of self-care included inhaling aromatic plants or using aromatherapy oils to self-soothe:

when I do get fed-up and when I do get miserable I just think ‘oh it’s normal, just let it go, just breathe through it’ or I’ll do my rosemary and my lavender or if I am at home one of my oils and I just think ‘right that’s ok now’ (Linda)

Tamsin, having been encouraged to actively practise self-care through iCare, embraced the concept and had no hesitation in describing the various ways she was taking care of herself. Tamsin’s self-care activities included nurturing her body through healthy food or following a beauty regime, attending a local music concert on her own or just having a cup of tea and sitting and giving herself ‘me time’:

And there’s only so much cake you can have at one time, and now it’s like, when I’m stressed instead of reaching for a cake or a bar of chocolate I just think ‘what else can I do to make myself feel better?’, so I’ve bought myself flowers a few times, bought more olives

Theme: ‘Its made me feel better’ – gains

Within the data participants reflected on increased feelings of well-being such as Linda who describes how iCare had ‘made me feel better’. Participants named various changes they had noticed following completion of iCare. References to feeling calmer, often involving use of some of the taught practices, were frequent:

I think the practices erm. I think one of the key ones was obviously the guided meditation helped because that sort of gets you calm and time aside (Olivia)

I did that thing with the heart thing didn’t I, I’ve done that a few times, especially if my heart feels like it’s racing or something like that, and I try and calm down and breathe a bit more, you know, try and think of something nice (Beth)

when I go to bed sometimes if I can’t switch off, I get my iPad whizz it on and it just gives me that 10 minutes and then that sometimes just takes all the sting out of my brain and it’s fine (Linda)

generally, I feel a bit calmer than I have felt in the past (Emily)

I can’t say my feelings of wanting to strangle people have gone away altogether, [laughs] because then that just wouldn’t be me, [laughs] erm, should we say I feel less inclined to act upon them now than I usually do. [Laughs] (Dawn)

Others commented on the usefulness and value they got from it with tools and approaches to take forward into their future caring:

I’ve gained an awful lot from it and got some really good things for going forward (Olivia)

I’ve definitely noticed improvements. You know, I will, um, use these techniques to, um, you know, help myself all the time now (Sophie)

it gives tools and mechanisms to be able to think of yourself rather than just the person who’s, who’s the object of the caring, and it’s tools to learn to be kinder to yourself (Emily)

Discussion

This study investigated the experiences of Carers of a brief face to face self-compassion based self-care intervention. Qualitative data was collected using semi-structured interviews.

Previous studies suggest that prioritizing self-care needs is difficult for Carers despite the positive value self-care is seen to have in supporting Carers’ own functioning and well-being.Citation30,Citation31 Whilst self-care has been seen as playing a crucial part in maintaining Carers emotional and physical health,Citation31 to date there have been no self-compassion-based self-care interventions designed to support Carers.Citation32

Our findings suggest that a brief self-compassion-based intervention can help Carers develop a kindly and friendly attitude to themselves. This in turn supports Carers in recognizing and legitimizing their own needs leading to conscious practices of self-care. This new way of seeing and treating themselves lead to improvements in mood, as reported by participants.

Carers are generally seen by society as unselfishly putting their Carees first, in some respects mirroring how nurses’ relationships with their patients are seen. Recent researchCitation33 suggests that nurses need permission in order to practise self-compassion and self-care, with this permission needing to come from others or society at large, a position replicated in the wider public.Citation34 If both the public and nursing professionals are unable to locate an internal self-permission and need an external ‘permission’ before becoming more self-compassionate, then it is likely that Carers require this too. Yet, the findings indicate that participants gained an inner permission and commitment to hear their own needs and then meet some of those needs through developing a kinder, more self-compassionate way of relating to themselves. This is in contrast to other researchCitation5 which suggests that Carers are reluctant to engage in self-care practices.

Calls have been made for the needs of Carers to be legitimized and validated by both health-care professionals and Carers themselves.Citation35 The extent of unmet Carer needs identified in the literatureCitation4 suggests that Carers are poor in legitimizing their own needs. Thus, the identification by participants of their own permission to be kind to themselves and meet some of their needs through a conscious approach to self-care is encouraging. iCare is the first targeted self-compassion intervention for CarersCitation32 and this study is the first to report Carers developing a permission to practise self-care through participation in a self-compassion intervention.

The findings from this study suggest that self-care as developed by Carers through becoming more self-compassionate is more closely aligned with the definition proffered by Lee and MillerCitation36 who posit that ‘personal self-care is defined as a process of purposeful engagement in practices that promote holistic health and well-being of the self’ (p. 98). This is consistent with the findings of a ‘conscious self-care’ practised by participants and which reflects the findings of: Godfrey et al.Citation37 of self-care involving activities practised deliberately; of Mills et al.Citation9 that self-care is seen as ‘a conscious and deliberate practice’ (p. 4); and of Dorociak et al.Citation7 who suggest that ‘self-care is purposeful in that it contains an intentionality component, a planful decision to engage in specific activities or behaviors’ (p. 326). Whilst all these studies were directed at patients or professional caregivers their views of self-care seem reasonably apt for Carers.

In the present study participants ultimately practise a conscious, intentional approach to self-care. The deliberately purposeful approach to self-care has been found in other studies regarding patients or professional caregivers.Citation7,Citation9,Citation36,Citation37 Where there may be divergence though is a focus on behaviours and practices of self-care. The findings suggest that Carer self-care, developed through enhancing self-compassion, may also be an internal process not visibly witnessed. Self-care can be manifested through reduced self-judgement and self-criticism and a greater acceptance of the fallibility of being human, not just through specific self-caring activities. It is proposed that this internal process involves a psychological ‘turning inwards’ and recognizing that, as one of the participants, Olivia, says, ‘I have needs’.

Self-compassion literature as it relates to Carers is scarce and research into MSC for Carers (the foundation of the iCare intervention) is absent. This qualitative study adds not only to the limited knowledge about participant experience of MSC as conceived by Neff and Germer, it additionally makes a novel contribution by offering insight into how a brief self-compassion intervention is experienced by Carers. The findings present a discerning, nuanced understanding of the operation of self-compassion as it relates to Carers.

Researchers call for interventions to be developed to help Carers with self-care e.g.Citation5,Citation30,Citation38 but none propose how these may be constituted. iCare is one such intervention that could address that gap. Mills et al.Citation9 point to the connection between self-compassion and self-care when they suggest that through self-compassion, becoming vulnerable and recognizing common humanity, self-compassion facilitates self-care (p. 9). This is further supported by their correlational studyCitation39 which pointed to a significant association between self-compassion and self-care ability. However, both studies concern palliative healthcare professionals and not Carers and do not examine methods of increasing self-compassion. The findings from the present study contribute knowledge by pointing to a connection between developing self-compassion and conscious self-care in Carers and offer support for the acceptability and feasibility for a brief self-compassion intervention for Carers.

This study offers a new conceptualization of Carer self-care, linking developing Carer self-compassion with a conscious self-care, recognizing the key aspect of inner permission to practise self-care and an attitudinal element of self-kindness. This conceptualization may be useful to those working with Carers in addressing their well-being as it may help to frame supportive questions around self-care as it pertains to Carers. This involves moving away from a self-care activity-based focus to exploring ways of developing kindlier self-talk and ultimately encouraging the self-permission aspect of Carer self-care.

Limitations and future directions

Like much of the carer researchCitation40 this study was not longitudinal. The long-term impact of iCare could not be assessed. Despite the challenges involved researching Carers of those with an uncertain and deteriorating prognosis potentially facing imminent death, future research could focus on the longitudinal impact of iCare.

All participants were white and female. Male Carers and ‘hidden Carers’, such as those from black and minority ethnic groups who do not have connections with palliative care services were hard to recruit and were thus sadly not represented in this study. Specialist cultural and media advice could help in constructing recruitment material best suited to reach these populations. It could be that Carers may respond differently to a self-compassion intervention depending upon either the length of time spent caring or the demands of caring for someone with a specific illness with its individual characteristics. Hence future research could target specific categories of Carer.

The first author facilitated iCare and conducted the participant interviews, which helped in building trust, connection and understanding with participants. The ethical considerations of such a dual role were affirmed throughout the researchCitation41 including adopting a position of critical reflexivity.

Whilst iCare was designed for time-pressed Carers it could have applicability to other groups of carers such as those caring for others with chronic illness, frailty or learning disabilities or to professional caregivers such as nurses.

Conclusions

This study sought to explore the experience of unpaid carers of those with a life-limiting or terminal diagnosis of a brief face to face self-compassion intervention. Emphasis in this intervention was placed on encouraging self-care, something which is recognized as supportive to such carers, but which has not previously been targeted through building self-compassion. Our findings highlight that through developing a kindlier internal orientation and locating a permission to allow themselves to practise an intentional self-care, participants reported perceived gains in wellbeing and benefitted from the acquisition of strategies to support themselves in their caring role. Additionally, this paper captures the often unheard voice of the Carer and, in doing so, provides an important insight into their experience of caring for others, and their struggle to offer the same care for themselves.

Disclaimer statements

Contributors: KD & AR: study design, manuscript review and editing; KD: iCare intervention design and delivery, data collection, data analysis, manuscript writing and submission to journal; AR: overall study supervision, manuscript editing.

Funding: No external funding.

Conflict of interest The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval None.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Hospice UK. Facts and Figures 2020. [cited 2020 Jan 12]. Available from: https://www.hospiceuk.org/about-hospice-care/media-centre/facts-and-figures

- Pottie CG, Burch KA, Montross Thomas LP, Irwin SA. Informal caregiving of hospice patients. J Palliat Med 2014;17(7):845–56.

- CSNAT. Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool: University of Cambridge & University of Manchester. [Cited 2019 Aug 17]. Available from: http://csnat.org/

- Oechsle K. Current advances in palliative & hospice care: problems and needs of relatives and family caregivers during palliative and hospice care-An overview of current literature. Med Sci (Basel, Switzerland) 2019;7(3):43.

- Dionne-Odom JN, Demark-Wahnefried W, Taylor RA, Rocque GB, Azuero A, Acemgil A, Martin MY, Astin M, Ejem D, Kvale E, Heaton K. The self-care practices of family caregivers of persons with poor prognosis cancer: differences by varying levels of caregiver well-being and preparedness. Support Care Cancer 2017;25(8):2437–44.

- Hampton MM, Newcomb P. Self-efficacy and stress among informal caregivers of individuals at end of life. J Hospice Palliat Nurs 2018;20(5):471–7.

- Dorociak KE, Rupert PA, Bryant FB, Zahniser E. Development of a self-care assessment for psychologists. J Counsel Psychol 2017;64(3):325–34.

- Adams M, Chase J, Doyle C, Mills J. Self-care planning supports clinical care: putting total care into practice. Progr Palliat Care 2020;28(5):305–7.

- Mills J, Wand T, Fraser JA. Exploring the meaning and practice of self-care among palliative care nurses and doctors: a qualitative study. BMC Palliat Care 2018;17(1):63–3.

- Mills J. Theoretical foundations for self-care practice. Progr Palliat Care 2021;29(4):183–5.

- Northouse LL, Katapodi MC, Song L, Zhang L, Mood DW. Interventions with family caregivers of cancer patients: meta-analysis of randomized trials. CA: Cancer J Clin 2010;60(5):317–39.

- Finlay-Jones A, Kane R, Rees C. Self-Compassion online: A pilot study of an internet-based self-compassion cultivation program for Psychology trainees. J Clin Psychol 2017;73(7):797–816.

- MacBeth A, Gumley A. Exploring compassion: a meta-analysis of the association between self-compassion and psychopathology. Clin Psychol Rev 2012;32(6):545–52.

- Rudaz M, Twohig MP, Ong CW, Levin ME. Mindfulness and acceptance-based trainings for fostering self-care and reducing stress in mental health professionals: a systematic review. J Context Behav Sci 2017;6(4):380–90.

- Lloyd J, Muers J, Patterson TG, Marczak M. Self-compassion, coping strategies, and caregiver burden in caregivers of people with dementia. Clinical Gerontol 2019;42(1):47–59.

- Miller JJ, Lee J, Niu C, Grise-Owens E, Bode M. Self-compassion as a predictor of self-care: a study of Social work clinicians. Clin Social Work J 2019;47(4):321–331.

- Neff KD, Germer CK. A pilot study and randomized controlled trial of the mindful self-compassion program. J Clin Psychol 2013 Jan;69(1):28–44.

- Neff KD. Self-Compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self Identity 2003;2(2):85–101.

- Braun V, Clarke V. (Mis)conceptualising themes, thematic analysis, and other problems with fugard and potts’ (2015) sample-size tool for thematic analysis. Int J Social Res Method 2016;19(6):739–43.

- Braun V, Clarke V. To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 2021: 13 (2) 210–216.

- Gilbert P. The Compassionate mind London Constable & Robinson; 2010.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 2019 11 (4): 589–597.

- Braun V, Clarke V. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitat Res Psychol 2021 (18) (3): 328–352.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualit Res Psychol 2006;3(2):77–101.

- Fletcher AJ. Applying critical realism in qualitative research: methodology meets method. Int J Social Res Method 2017;20(2):181–94.

- Danermark B, Ekström M, Karlsson JC. Explaining society: an introduction to critical realism in the social sciences. London: Routledge; 2002.

- Maxwell JA. A realist approach to qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2012.

- Bhaskar R. A realist theory of science. 2nd ed. London: Verso; 1997.

- Götze H, Brähler E, Gansera L, Schnabel A, Gottschalk-Fleischer A, Köhler N. Anxiety, depression and quality of life in family caregivers of palliative cancer patients during home care and after the patient's death. Eur J Cancer Care 2018;27(2):e12606.

- Applebaum AJ, Farran CJ, Marziliano AM, Pasternak AR, Breitbart W. Preliminary study of themes of meaning and psychosocial service use among informal cancer caregivers. Palliat Support Care 2014 Apr;12(2):139–48.

- Broady TR. Carers’ experiences of end-of-life care: a scoping review and application of personal construct psychology. Aust Psychol 2017;52(5):372–80.

- Garcia ACM, Silva BD, Oliveira da Silva LC, et al. Self-compassion in hospice and palliative care. A systematic integrative review. J Hospice Palliat Nurs 2021;23(2):145–54. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/NJH.0000000000000727.

- Andrews H, Tierney S, Seers K. Needing permission: the experience of self-care and self-compassion in nursing: a constructivist grounded theory study. Int J Nursing Stud 2020;101:103436.

- Campion M, Glover L. A qualitative exploration of responses to self-compassion in a non-clinical sample. Health Social Care Commun 2017;25(3):1100–8.

- Carduff E, Finucane A, Kendall M, Jarvis A, Harrison N, Greenacre J, Murray SA. Understanding the barriers to identifying carers of people with advanced illness in primary care: triangulating three data sources. BMC Family Practice 2014;15:48–8.

- Lee JJ, Miller SE. A self-care framework for Social workers: building a strong foundation for practice. Families Soc 2013;94(2):96–103.

- Godfrey CM, Harrison MB, Lysaght R, Lamb M, Graham ID, Oakley P. Care of self – care by other – care of other: the meaning of self-care from research, practice, policy and industry perspectives. Int J Evidence-Based Healthcare 2011;9(1):3–24.

- Pope N, Giger J, Lee J, et al. Predicting personal self-care in informal caregivers. Social Work Health Care 2017;56(9):822–39.

- Mills J, Wand T, Fraser JA. Examining self-care, self-compassion and compassion for others: a cross-sectional survey of palliative care nurses and doctors. Int J Palliat Nurs 2018;24(1):4–11.

- Henwood M, Larkin M, Milne A. Seeing the wood for the trees. Carer related research and knowledge: A scoping review. Melanie Henwood Associates. N/a 2017.

- Fleet D, Burton A, Reeves A, DasGupta MP. A case for taking the dual role of counsellor-researcher in qualitative research. Qualit Res Psychol 2016;13(4):328–46.