Abstract

Background

Globally, palliative care services do not meet demand. The World Health Organisation reports that 14% of people who need palliative care currently receive it. Moreover, the increase in chronic disease prevalence will result in the need for services to continue to grow. In Ireland, to help manage this demand, it is recommended that all physiotherapists should be able to deliver basic palliative care to patients diagnosed with life-limiting illnesses.

Objective

To explore the competency and confidence levels of physiotherapists in the management of patients with life-limiting conditions.

Methods

An anonymous, cross-sectional online questionnaire was designed and administered to physiotherapists working across various settings in Ireland.

Results

There were 90 respondents (response rate = 4.2%). A significant majority (93%, n = 84) agreed that most patients with life-limiting conditions can participate in physiotherapy. Just over half (56%, n = 50) felt confident in their ability to prescribe exercise for this cohort. Less than one-third (29%, n = 26) felt that the role of physiotherapy in palliative care was understood by the multi-disciplinary team. The majority (76%, n = 68) did not agree that their undergraduate training prepared them for work in this area. The ability to access mentorship from specialist palliative care physiotherapists was deemed as a facilitator in providing patient care.

Conclusion

This study highlights the demand for greater palliative care education, the need for a better understanding among the wider multi-disciplinary team so that patients receive timely access to physiotherapy, and the importance of establishing strong links between specialist physiotherapists and their generalist counterparts.

1. Introduction

Palliative care (PC) aims to improve the quality of life (QOL) of patients and that of their families who are facing challenges associated with life-threatening illnessesCitation1. The provision of holistic care is a core ethos of PC with health care professionals (HCPs) aiming to support the physical, emotional, social, and spiritual needs of their patientsCitation2. It is recommended that a full multi-disciplinary team (MDT), including; medics, nursing, social work, speech and language therapy, physiotherapy (PT), occupational therapy, complementary therapy (e.g. massage, aromatherapy), chaplaincy, dietetics, and pharmacy provides PCCitation3,Citation4, as one discipline alone cannot provide an entirely holistic approach. Internationally, clinical programmes have been established to promote a whole healthcare system working approach for this patient populationCitation5,Citation6. In the United States, clinical practice guidelines for the provision of quality PC provide recommendations to all HCPs (including non-PC specialists) to improve access to PC for everyone regardless of setting, diagnosis, prognosis, or ageCitation6. The Irish National Clinical Programme for PC published a PC Competency Framework in 2014, recommending that all PTs, across every sector of the Irish healthcare system, should have the ability to deliver basic PC to patients diagnosed with life-limiting illnessesCitation7,Citation8.

Over the past two decades, there has been a large increase in research examining the role of PT in the management of patients with life-limiting illnesses. The results have been positive for many different symptoms including fatigueCitation9–12, functional declineCitation9,Citation10,Citation13,Citation14, dyspnoeaCitation15–18 and QOLCitation10,Citation13,Citation14,Citation19,Citation20. Despite the abundance of research, multiple studies have also found that PTs are often absent or underutilised in PC settingsCitation21,Citation22. Current research shows that there is a lack of understanding among both PTs and other HCPs on the benefits of PT for this patient groupCitation21. In the United Kingdom (UK), PTs report that their undergraduate training did not prepare them adequately for working with terminally ill patientsCitation23. Patients are often seen as ‘dying from’ rather than ‘living with’ a terminal diagnosisCitation24. The word ‘palliative’ can often be associated with ‘no expectation of improvement’ among PTs, which may subsequently influence how patients are prioritised on therapists’ caseloadsCitation24.

Globally, PC services do not meet population demandCitation25. The World Health Organisation reports that approximately 14% of people who need PC, currently receive itCitation25. Moreover, the rise in chronic disease prevalence will result in the need for PC services to continue to growCitation26. In Ireland, it is estimated that the demand for PC services will rise by up to 84% between 2016 and 2046Citation27. Workforce development partnered with an increase in service provision is needed to meet the anticipated rise in patients requiring PC over the next twenty yearsCitation27.

Currently, there has been no research exploring whether the PC Competency Frameworks’ recommendations are being implemented or if PTs feel confident and competent adopting a PC approach. This investigation would provide an insight into possible knowledge gaps that may direct further education and training for the profession.

The aim of this research is to better understand the beliefs and attitudes of PTs towards their role in the management of patients diagnosed with a life-limiting illness, in the Irish healthcare system. This study also sought to evaluate PTs’ confidence and self-perceived competency levels in treating this patient cohort.

2. Methods

2.1 Study design

A cross-sectional online questionnaire design was employed.

2.2 Participants

The sample population was PTs registered with the Irish Society of Chartered Physiotherapists (ISCP); the national, professional body representing over 3,000 PTs in Ireland. PTs working in specialist PC (SPC) units were excluded (at the data analysis stage, n = 7), to make the results more generalisable to the whole profession.

2.3 Questionnaire development

A novel questionnaire was designed by one of the authors (DM.), informed by the PC Competency FrameworkCitation8 (see supplementary File 1). The questionnaire’s validity was established through review by co-author (EOS), and a pilot study with three HCPs with experience of research and the topic.

The questionnaire consisted of 27 questions, 24 closed- and three open-ended, divided into multiple sections; demographics (8 questions), attitudes and beliefs (7 questions), education (4 questions), competency levels based on the PC Competency Framework recommendations (5 questions), and open-ended questions (3 questions). Likert scales were used to assess the level of agreement regarding statements in the attitudes and beliefs (1 = ‘strongly disagree’, 5 = ‘strongly agree’), and perceived competency (1 = ‘very poor’, 5 = ‘very good’) sections. The questionnaire took approximately ten minutes to complete.

2.4 Procedure

The ISCP emailed a participant information leaflet and the questionnaire link to all their members who consented to receive research requests (N = 2154). All responses were anonymous (no IP addresses collected). Participants were only eligible to continue the questionnaire if they first clicked ‘yes’ to an obligatory consent question.

2.5 Data analysis

Participants’ quantitative data were aggregated and imported into the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS for Windows, v.28.0) and analysed using descriptive statistics. Data were presented as frequencies (i.e. proportions of respondents, %) or parameters relating to distributions (e.g., minimum/maximum, mean, standard deviation, median, and interquartile range). The Mann–Whitney U Test was used to compare differences between two independent groups due to the small sample size. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05, using two-tailed comparisons.

Qualitative data was analysed using an inductive thematic analysisCitation28. One author (DM) read all responses to identify themes. Line-by-line coding was used to apply codes to the data. Multiple exploratory ‘open’ codes were initially used, then collapsed into fewer more focused codes. This allowed the researchers to identify themes from the open-ended responses. The themes were then refined, defined, and named.

3. Results

3.1 Quantitative findings

The questionnaire link was emailed to 2154 ISCP members, achieving a response rate of 4.5% (N = 97). After removing those working in SPC, the final sample size was 90 (4.2%). Respondents’ characteristics are included in .

Table 1. Characteristics of respondents (N = 90).

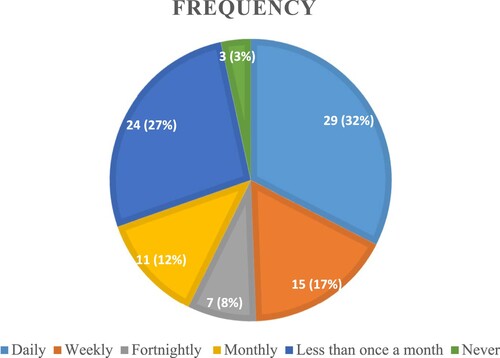

The majority (57%; n = 51) of respondents worked in an acute hospital setting. Almost half (49%; n = 44) indicated that they treat patients with life-limiting conditions, at least once per week (see ).

Figure 1. Frequency of interactions between respondents and patients with life-limiting illnesses (N = 89).

Respondents’ attitudes and beliefs towards their role in the management of this patient group are displayed in . A majority (93%; n = 84) of participants strongly agreed or agreed that most patients with non-curable conditions can participate in PT. However, respondents with more than ten years’ experience (62%; n = 56) were significantly less inclined to agree with this statement compared to participants with less experience (U = 727.50, P < 0.05). Less than one-third (29%; n = 26) strongly agreed or agreed that the role of PT in the management of this patient cohort is understood by members of the MDT.

Table 2. Attitudes and beliefs questions (N = 90).

Over half of respondents (56%; n = 50) felt confident in their ability to prescribe exercise to this cohort. Respondents who treated this cohort once a week or more felt more confident that patients can participate in PT compared to respondents who met this cohort less frequently (U = 1207.00, P < 0.05). These respondents also felt more comfortable discussing the psychological impact of loss of role and functional decline with patients (U = 1385.50, P < 0.001) and their carers (U = 193.00, P < 0.01).

Female respondents were significantly more comfortable providing education to patients (U = 746.50, P < 0.05), and rated themselves significantly more competent in relation to optimising comfort and QOL for patients (P < 0.05) compared to males.

Over three-quarters of participants (76%, n = 68) strongly disagreed or disagreed that their undergraduate training adequately prepared them to treat this cohort. However, participants with <3 years’ experience rated their PC education higher than respondents who had completed their training earlier (U = 604.00, P < 0.05). Most (63%, n = 57) of the respondents had completed postgraduate continuous professional development (CPD) in PC, predominantly via ‘study days’ (56%, n = 50). Fifteen per cent (n = 13) had a postgraduate certificate, diploma, or Master’s degree in the area.

Participants were asked to rate their own competency levels based on recommendations outlined in the PC Competency Framework. The majority (67%, n = 60) rated themselves ‘good’ or ‘very good’ when asked about their knowledge of professional and ethical practice for patients with life-limiting conditions (see ). Over half (56%, n = 50) rated themselves as ‘fair’, ‘poor’, or ‘very poor’ when asked how competent they felt discussing loss, grief, and bereavement with patients.

Table 3. Self-rated competency levels based on HSE’s Palliative Care Competency framework (N = 90).

Respondents who treated this patient group once a week or more, deemed themselves more competent in three domains; optimising comfort and QOL (U = 1187.00, P < 0.05); care planning and collaborative practice (U = 1287.00, P < 0.01); and communication with patients and their carers (U = 1294.50, P < 0.01), than participants who meet with patients less frequently.

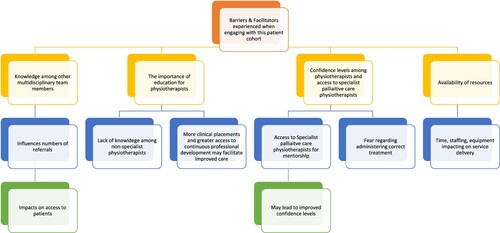

3.2 Qualitative findings

In two open-ended questions, participants were asked to explore the barriers and facilitators they experienced when engaging with this patient group. Four themes emerged from the thematic analysis of these questions (see for a thematic map).

Theme 1: knowledge among other MDT members of the role of PT

The most common factor cited by respondents was the perceived depth of knowledge among other MDT members towards the role of PT in this speciality. Some cited a lack of awareness as a barrier to accessing this patient cohort due to low referral rates.

‘Most people (staff / patients) perceive physio as a profession to help people get better, rather than preventing decline.’

‘Delayed referrals- waiting for patient to be more symptomatic’

Theme 2: the importance of education for PTs

Respondents cited a lack of knowledge among PTs as an obstacle to treating patients.

‘There is a tendency [amongst PTs] to step back from patients in hospitals under care of palliative teams’

‘Greater education on palliative care required at all levels … This would alleviate fear of working with patients with life limiting diseases’

Theme 3: confidence levels among PTs and access to SPC PTs

Many respondents expressed fear when managing this cohort. Respondents reported a lack of confidence regarding their competency to adequately assess patients’ abilities, or safety concerns, from a PC perspective, e.g., concerns regarding ‘Knowing how far it is safe to push the patient’.

Other respondents highlighted the potential additional emotional load that may accompany the management of patients nearing the end of their life.

‘The hesitance to engage with a cohort where the emotional load is perceived to be higher than more conventional PT areas.’

‘Good in-service training and links with specialist palliative care teams around the country’

Theme 4: availability of resources

Respondents highlighted the discrepancy between resources available in SPC settings compared to other healthcare settings, where resources specifically for PC are more limited.

‘Generally more time with patients than other staff members so you get to know them and their families well’

4. Discussion

4.1 Main findings

A significant majority (93%, n = 84) of respondents agreed that most patients with life-limiting conditions can participate in PT. These results reflect the study carried out by Sheil et al. (2016)Citation29 whereby 94% of participants agreed that being physically active is important for this cohort. In this study, all participants were PTs treating patients with an advanced cancer diagnosis within the Irish healthcare system. Their experience raises the likelihood that their knowledge would be greater on this topic than the general physiotherapist population in Ireland. Despite the respondents’ strong beliefs that patients could participate in PT, they expressed concerns on how this should be implemented. This is similar to Sheil et al. (2016)Citation29 whereby an overwhelming majority of PTs indicated a need for further guidance on exercise prescription for patients diagnosed with bone metastases.

Interestingly, respondents with over 10 years’ experience were less convinced that patients could participate in exercise, than earlier career PTs. This is similar to a study involving 234 PTs working in South Africa where attitudes to PC were negatively associated with years of experienceCitation30. This difference in opinion may be due to the cultural shift that has taken place over the last four decades. Healthcare systems internationally have moved away from a biomedical approach to a more biopsychosocial model of care, which commands clinicians to examine all aspects of a person’s lifeCitation31. Perhaps, more experienced PTs are still adopting more of a biomedical approach compared to their less experienced counterparts who have more recently completed their education more likely under a biopsychosocial ethos. This assumption appears to be supported by the respondents’ opinions on their undergraduate training and how it prepared them for working with this patient group. Participants with less than three years’ experience rated their PC education higher than respondents who had completed their training earlier. This may be due to improvements in the curriculum or potentially because of the ‘Dunning–Kruger effect’, a cognitive bias whereby people with less expertise in an area tend to overestimate their knowledgeCitation32. Speculatively, less experienced PTs may think their education is sufficient simply because they have not been exposed to more complex cases where gaps in their knowledge are highlighted. However, even if there have been some improvements in the curricula, over three-quarters of respondents disagreed that their undergraduate training was adequate in this area. This problem is not exclusive to Irish third level institutions, with similar findings in qualitative studies from the UK and Northern IrelandCitation33,Citation34.

Only 29% (n = 26) of respondents agreed that the role of PT in this specialty is understood by other members of the MDT. Many respondents cited a lack of understanding among their colleagues as a barrier to providing good quality care. In the UK, Nelson et al.,Citation35 investigated nurses’ reluctance to refer patients receiving PC to PT. A key belief held was that ‘PTs don’t have the necessary knowledge and skills required to provide good PC’.

Female respondents were significantly more comfortable providing education to patients than males. In addition, females rated themselves significantly more competent in optimising comfort and QOL for this patient cohort. A study by Roter et al.,Citation36 examined the differences between the two sexes with conjecture that female doctors are more patient-centred in their communication styles. However, the authors highlighted that in this meta-analysis, patient outcomes were not addressed, so no direct conclusion can be drawn as to the “correct” way to communicate with patients. Nevertheless, it seems plausible that the effects found are an indication of a more health-promoting, therapeutic environment created by female HCPs.

In the open-ended questions, several respondents cited concerns regarding the psychological impact of caring for patients approaching end-of-life. This is a common feeling experienced by HCPs. A study published by Grech et al. (Citation2018)Citation37 exploring the experiences of nurses caring for patients approaching the terminal phase of their illness, found that the participants struggled with emotions including feelings of helplessness, distress, and compassion fatigueCitation37. Studies have found that HCPs who meet the criteria for burnout make more medical errorsCitation38, display lower levels of empathyCitation39 and overall deliver poorer quality-of-careCitation40. Consequently, it is imperative that appropriate interventions are employed to optimally support HCPs working with this cohort, to bolster their capacity for self-care and prevent burnout.

4.2 Strengths and limitations

This study is informed by the PC Competency Framework which recommends competencies for all PTs working with patients diagnosed with life-limiting disease. It contains insights from PTs working in a wide range of settings.

However, several limitations must be acknowledged for future reference. The results are not generalisable to the wider PT population. The researchers attempted to mitigate this by excluding PTs who currently work in SPC units; however, almost half (49%, n = 44) of participants indicated that they treat patients with life-limiting conditions, once per week or more frequently and 63% (n = 57) of respondents completed post graduate CPD in PC. Both findings indicate a potential respondent bias. The low response rate of 4.2% is another limitation. Consideration of these factors needs to be given in the interpretations of the present findings.

4.3 Future research

Additional studies exploring the attitudes and beliefs of generalist PTs towards their role in the management of this patient group are recommended. Future researchers may consider altering recruitment methods to target PTs with less experience in the specialty of PC to increase generalizability of the results. Focussing on PTs working in primary care or private practise who have fewer educational resources available to them may lead to different results. Further studies to understand the mismatch in knowledge of wider members of the MDT towards the role of PT in this area would also be helpful.

Interestingly, several respondents cited concerns regarding the psychological impact of caring for patients approaching end-of-life. This was not prompted within the closed questions of the questionnaire and may be an interesting area for further research.

5. Conclusion

This study aimed to explore the competency and confidence levels of PTs in the management of patients diagnosed with life-limiting illnesses, in the Irish healthcare system.

Many PTs do not feel confident or competent in this area. Furthermore, many feel that other members of the MDT do not recognise the role PTs can have in the management of this cohort. Improved education at undergraduate level partnered with the provision of mentorship and support from SPC PTs for generalist PTs may help to progress the profession further in this area.

Ethical approval

Full ethical approval was obtained from the Social Research Ethics Committee in University College Cork to conduct this study (Reference No = SOM/SREC/2022/2610/2). This study adheres to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki 2013.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Sepúlveda C, Marlin A, Yoshida T, Ullrich A. Palliative care. J Pain Symp Manage 2002;24(2):91–6.

- Wesley L, Ikbal M, Wu J, Wahab M, Yeam C. Towards a practice guided evidence based theory of mentoring in palliative care. J Palliat Care Med 2017;7(1):296.

- Jünger S, Pestinger M, Elsner F, Krumm N, Radbruch L. Criteria for successful multiprofessional cooperation in palliative care teams. Pallia Med 2007;21(4):347–54.

- Van der Steen JT, Radbruch L, Hertogh CM, de Boer ME, Hughes JC, Larkin P, et al. White paper defining optimal palliative care in older people with dementia: a Delphi study and recommendations from the European Association for Palliative Care. Pallia Med 2014;28(3):197–209.

- NHS, England. Palliative and end of life care strategic clinical network – NHS. [Internet] Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/east-of-england/clinical-networks/our-networks/palliative-and-end-of-life-care-strategic-clinical-network/.

- Ferrell B, Twaddle ML, Melnick A, Meier DE. National consensus project clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care guidelines, 4th Edition. J Pallia Med 2018;21(12):1684–1689.

- HSE. About the Palliative Care Programme – HSE.ie. [Internet]. HSE.ie. 2010. Available from: https://www.hse.ie/eng/about/who/cspd/ncps/palliative-care.

- Ryan K, Connolly M, Charnley K, Ainscough A, Crinion J, Hayden C, Keegan O, Larkin P, Lynch M, McEvoy D, McQuillan R, O’Donoghue L, O’Hanlon M, Reaper-Reynolds S, Regan J, Rowe D, Wynne M. Palliative care competence framework. Dublin: Health Service Executive; 2014.

- Litterini AJ, Fieler VK, Cavanaugh JT, Lee JQ. Differential effects of cardiovascular and resistance exercise on functional mobility in individuals with advanced cancer: a randomized trial. Arch Phys Med Rehab 2013;94(12):2329–35.

- Oldervoll LM, Loge JH, Paltiel H, Asp MB, Vidvei U, Wiken AN, et al. The effect of a physical exercise program in palliative care: a phase II study. J Pain Symp Manag 2006;31(5):421–30.

- Pyszora A, Budzyński J, Wójcik A, Prokop A, Krajnik M. Physiotherapy programme reduces fatigue in patients with advanced cancer receiving palliative care: randomized controlled trial. Supp Care Cancer 2017;25(9):2899–908.

- Meneses-Echavez JF, Gonzalez-Jimenez E, Ramirez-Velez R. Supervised exercise reduces cancer-related fatigue: a systematic review. J Physiot 2015;61(1):3–9.

- Langer D, Hendriks E, Burtin C, Probst V, Van der Schans C, Paterson W, et al. A clinical practice guideline for physiotherapists treating patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease based on a systematic review of available evidence. Clin Rehab 2009;23(5):445–62.

- Grądalski T. Limb edema in patients with advanced disease – a pilot study of compression therapy combined with diuretics. Pallia Med Pract 2019;13(2):51–6.

- Hately J, Laurence V, Scott A, Baker R, Thomas P. Breathlessness clinics within specialist palliative care settings can improve the quality of life and functional capacity of patients with lung cancer. Pallia Med 2003;17(5):410–7.

- Osterling K, MacFadyen K, Gilbert R, Dechman G. The effects of high intensity exercise during pulmonary rehabilitation on ventilatory parameters in people with moderate to severe stable COPD: a systematic review. Int J Chr Obst Pulm Dis 2014;9:1069–1079.

- Dowman LM, McDonald CF, Hill CJ, Lee AL, Barker K, Boote C, et al. The evidence of benefits of exercise training in interstitial lung disease: a randomised controlled trial. Thorax 2017;72(7):610–9.

- McMurray JJ, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, Auricchio A, Böhm M, et al. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012 of the European society of cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 2012;33(14):1787–847.

- Radder DL, Lígia Silva de Lima A, Domingos J, Keus SH, van Nimwegen M, Bloem BR, et al. Physiotherapy in Parkinson’s disease: a meta-analysis of present treatment modalities. Neurorehab Neural Rep 2020;34(10):871–80.

- Albrecht TA, Taylor AG. Physical activity in patients with advanced-stage cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2012;16(3):293–300.

- Høgdal N, Eidemak I, Sjøgren P, Larsen H, Sørensen J, Christensen J. Occupational therapy and physiotherapy interventions in palliative care: a cross-sectional study of patient reported needs. BMJ Supp Pallia Care 2020.

- Woitha K, Schneider N, Wünsch A, Wiese B, Fimm S, Müller-Mundt G. Die Einbindung und Anwendung der Physiotherapie in der Hospiz- und Palliativversorgung. Der Schmerz 2017;31(1):62–8.

- Waldron M, Kernohan WG, Hasson F, Foster S, Cochrane B, Payne C. Allied health professional's views on palliative care for people with advanced Parkinson's disease. Int J Ther Rehab 2011;18(1):48–57.

- Taylor HN, Bryan K. Palliative cancer patients in the acute hospital setting – physiotherapists attitudes and beliefs towards this patient group. Prog Pallia Care 2014;22(6):334–41.

- World Health Organization. Palliative care. World Health Organization [Internet] 2020, Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care.

- Burch JB, Augustine AD, Frieden LA, Hadley E, Howcroft TK, Johnson R, et al. Advances in geroscience: impact on healthspan and chronic disease. J Geront Series A 2014;69(Suppl_1):S1–S3.

- May P, Johnston BM, Normand C, Higginson IJ, Kenny RA, Ryan K. Population-based palliative care planning in Ireland: how many people will live and die with serious illness to 2046? HRB Open Res 2019: 2–35.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualita Res Psychol 2006;3(2):77–101.

- Sheill G, Guinan E, Hevey D, Neill L, Hussey J. Physical activity and metastatic disease: the views of physiotherapists in Ireland. Physiot 2016;102:e134.

- Morrow BM, Barnard C, Luhlaza Z, Naidoo K, Pitt S. Knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and experience of palliative care amongst South African physiotherapists. South African J Physiot 2017;73(1).

- Farre A, Rapley T. The new old (and old new) medical model: four decades navigating the biomedical and psychosocial understandings of health and illness. Healthcare 2017;5(4):88.

- Kruger J, Dunning D. Unskilled and unaware of it: how difficulties in recognizing one's own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. J Person Social Psychol 1999;77(6):1121–1134.

- Taylor HN, Bryan K. Palliative cancer patients in the acute hospital setting – physiotherapists attitudes and beliefs towards this patient group. Prog Pallia Care 2014;22(6):334–341.

- Waldron M, Kernohan WG, Hasson F, Foster S, Cochrane B, Payne C. Allied health professional's views on palliative care for people with advanced Parkinson's disease. Int J Ther Rehab 2011;18(1):48–57.

- Nelson LA, Hasson F, Kernohan WG. Exploring district nurses’ reluctance to refer palliative care patients for physiotherapy. Int J Pallia Nurs 2012;18(4):163–70.

- Roter DL, Hall JA. Physician gender and patient-centered communication: a critical review of empirical research. Annual Rev Pub Heal 2004;25:497–519.

- Grech A, Depares J, Scerri J. Being on the frontline. J Hosp Pallia Nurs 2018;20(3):237–44.

- Williams ES, Manwell LB, Konrad TR, Linzer M. The relationship of organizational culture, stress, satisfaction, and burnout with physician-reported error and suboptimal patient care. Heal Care Manag Rev 2007;32(3):203–12.

- Tei S, Becker C, Kawada R, Fujino J, Jankowski KF, Sugihara G, et al. Can we predict burnout severity from empathy-related brain activity? Transl Psych 2014;4(6):e393–3.

- Poghosyan L, Clarke SP, Finlayson M, Aiken LH. Nurse burnout and quality of care: cross-national investigation in six countries. Res Nurs Heal 2010;33(4):288–98.