Abstract

The aim of this study was to evaluate the turkey spermatozoa motility in in vitro conditions and to prove the effect of different conditions of incubation – diluents, temperature and age of birds. Spermatozoa were obtained from adult turkey's line of Big 6, and spermatozoa motility parameters were evaluated using a computer-assisted semen analyzer (CASA) system. Significant decrease of spermatozoa motility at laboratory temperature (22°C) was detected from time 0 (94.15%) till 180 minutes of incubation (53.91%). At the cool media incubation (5°C), this difference was lower (95.41 and 78.86%, respectively), and the differences were significant from 30 minutes of incubation till 180 minutes. Progressive spermatozoa motility replicated the tendency of total spermatozoa motility. When the physiological solution to commercial diluent at 5°C was compared, the spermatozoa motility and progressive motility in both groups were very consistent for 90 minutes of incubation. Subsequently, significantly higher spermatozoa motility was detected at time periods 120, 150 and 180 minutes of incubation in commercial diluent. Motility was also higher in this group after 24 hours. Influence of age on spermatozoa motility parameters was analysed at 22°C at the time 0 and after 30 minutes of incubation. Analysis of spermatozoa motility as well as progressive spermatozoa motility proved higher values in Group A (aged 35–42 weeks) compared to Group B (aged 63–73 weeks). These results clearly suggest that low temperature and commercial diluents maintain motility parameters during longer time periods and the increasing age of birds has negative impact on motility parameters.

1. Introduction

Turkey spermatozoa storage is successfully utilized in commercial breeding operations, but the efficiency of such systems in maintaining spermatozoa fertilizing ability in vitro for 24 hours leads into insignificance in comparison to the oviductal storage system in vivo, which can maintain fertilizing ability for many weeks (Hocking Citation2009).

Most of semen diluents provide the energy for metabolism and buffering capacity (Tvrdá et al. Citation2013), prevent clumping by thinning out the concentration as well as increasing the metabolic activity of the spermatozoa and enhancing their motility. From a practical standpoint, this reduces the normal number of males required and the overall costs (Semen Quality Citation2007; Slanina et al. Citation2012).

In order to maintain the fertilization ability of stored spermatozoa in vitro, semen has to be stored at 2–8°C (Donoghue & Wishart Citation2000) and diluted in a suitable diluent (Akçay et al. Citation1997). The use of low temperatures in combination with a buffered saline medium containing glycolytic substrates and intermediates of the citric acid cycle is not sufficient to ensure prolonged in vitro survival of turkey spermatozoa (Douard et al. Citation2000; Slanina et al. Citation2013).

The majority of diluents used are salt solutions convenient for immediate survival of spermatozoa because they provide osmotic pressure (330–400 mOsm) and pH (7.0–7.4) identical with the seminal plasma (Thurston Citation1995; Miškeje et al. Citation2013). Diluents should also contain various energy substrates. Therefore, diluents used for poultry semen are enriched with carbohydrates (glucose or fructose) and other components probably to provide energy such as citrate, glutamate or acetate (Thurston Citation1995; Slanina et al. Citation2012).

Douard et al. (Citation2003) showed that age of turkey males affects the quality of fresh and also incubated spermatozoa. Ageing process was accompanied by a reduction of the number of spermatozoa and semen volume (Kotlowska et al. Citation2007), decreasing motility, viability and membrane integrity of spermatozoa (Rosato et al. Citation2006). Consequently, these changes lead to a progressive decrease in fertilizing ability of turkey semen (Bakst & Cecil Citation1992; Douard et al. Citation2003), and they can also influence the preservation during storage (Douard et al. Citation2003; Rosato et al. Citation2006).

Spermatozoa motility is a critical factor in the maintenance of fertility. In birds, the vaginal portion of the hen's oviduct regulates spermatozoa entry and only motile spermatozoa are able to traverse the vagina and enter into the hen's spermatozoa storage tubules (King et al. Citation2000). As described by Froman et al. (Citation1999), the spermatozoa motility is a primary determinant of fertility in the fowl. On the basis of results, a graded relationship was predicted between fertility and spermatozoa motility. When fertility was plotted as a function of spermatozoa motility, data points approximated a skewed logistic function. The hypothesis that vaginal immunoglobulins constitute an immunological barrier to spermatozoa transport was tested and rejected.

The aim of this study was to analyse and compare the effect of different diluents used in practice, different temperatures (5°C and 22°C) and animal age on turkey spermatozoa motility in vitro using computer-assisted semen analyzer (CASA) system in various incubation time periods.

2. Material and methods

In this study, semen from turkeys (n = 30) line of Big 6 [British United Turkeys (BUT) Ltd., Chester, UK], aged between 35 and 73 weeks, was evaluated. Semen collection was realized by stimulating of the copulatory organ to protrude by massaging the abdomen and the back over the testes. Semen samples were collected with an aspirator and used a mixture of several groups of identical individual turkeys. The semen was diluted in a ratio of 1 part of semen and 2 parts of physiological saline (NaCl 0.9% w/v intravenous Infusion Bieffe, Bieffe Midetal S.p.A., Grosotto, Italy) as well as commercial diluent (Glutac–2, AMP–Lab GmbH, Mainz, Germany). After transfer to the laboratory, samples were repeatedly diluted before analysis in a ratio of 10 µl of diluted semen and 1000 µl of diluent, so the final dilution was 1:200. In each, experiment was realized in six replicates.

2.1. Analysis of different diluents

Two pooled samples (in six replicates) were prepared from each of diluted semen: sample PS – was diluted with physiological solution (PS) – and the sample CD – was diluted with the commercial diluent (CD). Both samples were stored in a refrigerator (at the temperature 5°C). The average pH of semen diluted in physiological solution was 7.33 and semen diluted in commercial semen was 7.06. Spermatozoa motility was evaluated and compared in cool media (5°C) in time periods 0, 30, 60, 90, 120, 150 and 180 minutes and 24 hours. Turkey spermatozoa motility was also analysed after 24 hours of incubation at 5°C in time periods 0, 10, 20 and 30 minutes at laboratory temperature (22°C).

2.2. Analysis of different temperatures

Two pooled samples (in six replicates) were prepared from collected semen diluted with physiological solution, and one sample was incubated at 22°C – sample T22 and the second sample was placed in the refrigerator and was incubated at 5°C – sample T5. The motility was evaluated and compared in the seventh time periods: 0, 30, 60, 90, 120, 150 and 180 minutes.

2.3. Age of turkey

Two pooled samples (in six replicates) were marked as A and B, depending on age – ‘young’ turkey, Group A (aged 35–42 weeks) and ‘old’ turkey, Group B (aged 63–73 weeks). Samples were incubated at the laboratory temperature (22°C). The average pH individual samples were 7.88 and 7.33. The impact of age on spermatozoa motility was observed in two time periods: 0 and 30 minutes.

2.4. Motility analysis

Each of the prepared samples were evaluated using a CASA system – Sperm Vision® program (Minitub, Tiefenbach, Germany) equipped with a microscope (Olympus BX 51, Japan) to assess the spermatozoa motility (Massányi et al. Citation2008; Kročková et al. Citation2012). Each sample was placed into Makler Counting Chamber® (depth 10 µm, Sefi–Medical Instruments, Germany).

Using the turkey-specific set-up, the total motile spermatozoa (MOT; %) and progressively motile spermatozoa (PRO) were evaluated. Within each of the measurement by the CASA system was evaluated motility parameters from minimum seven fields of Makler Counting Chamber (Błaszczyk et al. Citation2013).

2.5. Statistical analysis

Obtained data were statistically analysed using PC program Excel and a statistics package SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., USA) using Student's t-test and Scheffe's test. Statistical significance was indicated by p values of less than 0.05, 0.01 and 0.001.

3. Results and discussion

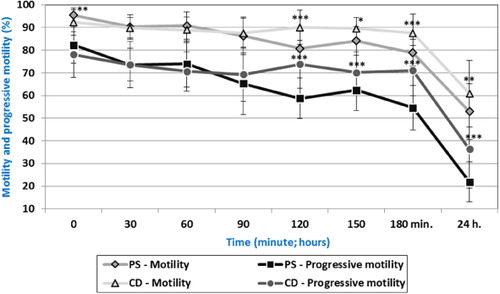

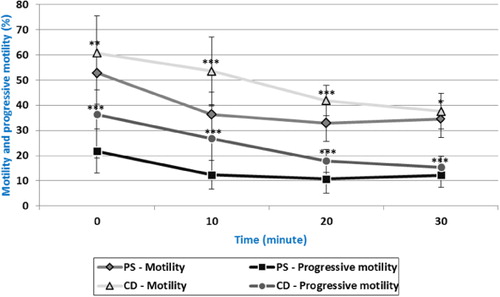

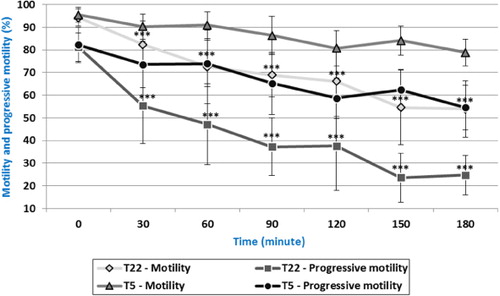

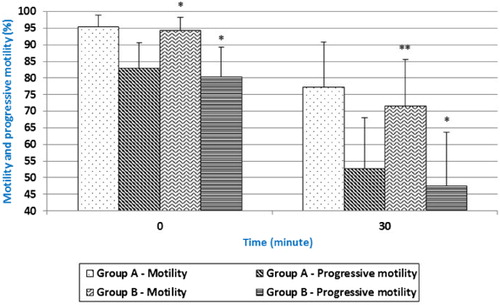

Complete results of the analyses of spermatozoa motility parameters are shown in –.

Significant differences *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

Significant differences *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

Significant differences *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

Significant differences *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

3.1. Effect of different diluents on spermatozoa motility

Significantly (p < 0.01) higher spermatozoa motility was detected in sample PS in comparison with sample CD at Time 0 (). At time intervals of 30–90 minutes of incubation, no significant differences were observed between diluents. The motility after 120 minutes and 24 hours was significantly (p < 0.05 – p < 0.001) decreased in sample PS.

Through a comparison of spermatozoa progressive motility, statistically significant differences were found between diluents after 120 minutes of incubation (), where significantly (p < 0.001) higher value was detected in the sample CD. This tendency was observed till the end of incubation. These data show that the commercial diluent maintained progressive motility of turkey spermatozoa for a longer time. Data also show that after 90 minutes of incubation equal results (p < 0.05) for both analysed diluents were found (MOT: PS vs. CD 86.33 and 87.44%; PRO: PS vs. 65.19 and 69.31%), and later commercial diluent showed better effects of conservation. After 24 hours of incubation, commercial diluent showed also better effects on spermatozoa motility compared to physiological solution.

Morrell et al. (Citation2005) reported that the motility of spermatozoa after storage for 2 hours in the new extender ‘Turkey semen extender’ was higher than in the commercially available extenders. The spermatozoa preparations were examined visually by light microscope using a heated stage (37°C). The proportion of motile spermatozoa in the preparation was estimated subjectively. However, after 3 hours storage at room temperature, the proportion of motile spermatozoa in Beltsville Poultry Semen Extender (BPSE) had decreased to <5% spermatozoa, whereas the proportion of motile spermatozoa in both Nidacon's turkey semen extender and in Ovodyl remained constant.

In our work, spermatozoa motility of 80.70% was detected in sample PS after 120 minutes of incubation. Higher motility (90.04%) was observed in sample CD after 120 minutes, what is almost about 10% more than in sample PS. In the study of Morrell et al. (Citation2005), the spermatozoa motility was significantly higher (P < 0.05) in the ‘Turkey Semen Extend’ (72.5%) after storage for 2 hours. The motility in the commercial diluents Ovodyl and BPSE was approximately 62.5%. Higher motility was reached in our study after 2 hours of in vitro incubation. This is related to semen storage (at the temperature of 5°C).

Iaffaldano et al. (Citation2005) compared the effects of three different diluents: BPSE, Lake and IGGKPh in which turkey semen was stored at 5°C for 48 hours. Cold storage of turkey semen for 48 hours decreased (P < 0.01) the motility, viability and membrane integrity of the spermatozoa diluted with the different extenders. Their results indicated that the semen diluted with BPSE showed a higher motility during storage compared with by other diluents. After 3 hours of in vitro storage, all the parameters were better with BPSE compared to Lake and IGGKPh extender, respectively, but no significant differences were detected. Motility (P < 0.01), viability (P < 0.01) and membrane integrity (P < 0.05) were also significantly higher after 24 hours with BPSE compared to IGGKPh and Lake extenders.

3.2. Spermatozoa motility after 24 hours of in vitro incubation

Significantly (p < 0.01) higher spermatozoa motility was observed after 24 hours () in sample CD. Subsequently, significantly higher motility was detected at time periods 10 minutes, 20 minutes (p < 0.001) and 30 minutes (p < 0.05) of incubation in sample CD.

Measurement of progressive motility showed statistically significant difference (p < 0.001) at all time periods of in vitro incubation, and higher progressive motility was found in sample CD ().

3.3. Effect of different temperatures on spermatozoa motility

Data suggest that spermatozoa showed higher values after dilution with physiological solution and incubation at the cool media (at 5°C) compared to values of spermatozoa incubated at the laboratory temperature (22°C). Significant difference (p < 0.001) was found after 30 minutes of incubation. The spermatozoa motility of 94.15% was recorded in the sample T5 and 82.35% in the sample T22 ().

Giesen and Sexton (Citation1983) investigated the effect of storage temperature on turkey spermatozoa after 18 hours of incubation. Spermatozoa were stored at 5, 15, 25 and 35°C. Spermatozoa motility between unstored control and samples held at 5°C was not different (62% vs. 64%). Samples stored at 15°C and 25°C had motility from 40% to 8%, and those kept at 35°C for 18 hours were immotile. Kotłowska et al. (Citation2007) reported that the percentages of turkey spermatozoa motility during 150 minutes and 24 hours storage in the cold (4–7°C) were similar (about 70%). The significant decrease (P < 0.05) was detected after 48 hours of incubation. Storage time caused a steady decrease in spermatozoa motility characteristics related to both speed of movement (velocity curved line [VCL] and velocity average path [VAP]) and trajectory of movement (velocity straight line [VSL] and linearity [LIN]). No changes in beat cross frequency (BCF) and mean angular displacement (MAD) were found at the same time.

In our work, the spermatozoa motility was 54.61% in the sample T22 and 84.08% in the sample T5 after 150 minutes. The difference between our results and those of Kotłowska et al. (Citation2007) after 150 minutes of in vitro incubation could be caused by the diluent. They used commercial diluent Ovodyl (IMV, I'Aigle, France) compared to our dilution with physiological solution (NaCl 0.9% w/v Intravenous Infusion Bieffe, Grosotto, Italy).

Regarding progressive motility (), a significant decrease (p < 0.001) of the motility from the time 30 minutes to 180 minutes with a higher progressive motility in sample T5 was found. No significant difference (81.20–82.22%) was found at the time of 0 minutes.

3.4. Effect of age on turkey spermatozoa mobility parameters

The data in our study show that the age significantly influences spermatozoa motility parameters. Significant difference (p < 0.05) was detected for spermatozoa motility and progressive motility () with higher values in Group A (aged 35–42 weeks) compared to the Group B (aged 63–73 weeks).

The study of Kotlowska et al. (Citation2007) showed that biochemical parameters of spermatozoa seemed to be more affected than quantitative parameters by age of the turkey males. Also volume, spermatozoa concentration and total number of spermatozoa were dependent on the strain of turkey. Douard et al. (Citation2003) reported a significant effect the age of the males had on spermatozoa viability and motility. This effect was visible at 47 weeks of age for viability (15% loss) but only at 52 weeks of age for motility (20% loss). In addition, in vitro storage altered the overall quality of spermatozoa (9–15% decrease in viability and 40–50% loss of motility throughout the reproductive period). Also fertility rates were affected by the age.

The purpose of Iaffaldano et al.'s (Citation2007) study was to evaluate the effect of productive period of two commercial turkey strains on semen quality changes during in vitro storage for up to 48 hours at 5°C. Two different periods were considered: first period from 32 to 40 weeks of age and the second one from 44 to 52 weeks. Turkey males from both BUT Big 6 line and Hybrid Large White line (Hybrid) were used. Semen pools of each tom strain were diluted with BPSE. The spermatozoa concentration was significantly affected by period (P < 0.01) and strain (P < 0.05), with best values in the first period and in the Hybrid semen. Besides the motility, viability and membrane integrity during 48 hours of storage were better (P < 0.05) in the first period compared to the second one for both strains, particularly in Hybrid semen.

Similar results of spermatozoa motility were also observed in our study, with better results shown in Group A incubated at laboratory temperature. Motility immediately after collection was 95.44% in Group A versus 94.24% of Group B with significantly difference p < 0.05. After 30 minutes of in vitro incubation, significant difference (p < 0.01) between Groups A and B was evident: 77.30% in Group A and 71.61% in Group B. Similar tendency was detected also for progressive motility.

4. Conclusion

Our results show that spermatozoa motility parameters of turkey semen diluted with physiological solution and commercial diluent were similar for 90 minutes of incubation. Nevertheless, at longer incubation, significantly higher values showed spermatozoa incubated in the commercial diluent. These data show that commercially available diluents are convenient for long-term storage of spermatozoa. However, for 90 minutes of storage, it is possible to use only physiological solution. Our results also show that for turkey spermatozoa storage, it is needed to keep spermatozoa at low temperatures (4–8°C). Evaluation of spermatozoa motility and progressive motility at two different age groups turkeys shows higher values immediately after collection and after 30 minutes in Group A (35–42 weeks). For this reason, it is convenient to use spermatozoa acquired from younger males for artificial insemination.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Akçay E, Varişli Ö, Bucak MN, Yavaş I, Tekın N. 1997. Hindi spermasının değişik sulandırıcılarda 4°C de saklanması [Preservation in various diluents of turkey semen at 4°C]. Ankara Üniversitesi Veteriner Fakültesi Dergisi. 44:137–149.

- Bakst MR, Cecil HC. 1992. Effect of bovine serum albumin on motility and fecundity of turkey spermatozoa before and after storage. J Reprod Fertil. 94:287–293. 10.1530/jrf.0.0940287

- Błaszczyk M, Slanina T, Massanyi P, Stawarz R. 2013. Semen quality assessment of New Zealand white rabbit bucks. J Microbiol Biotechnol Food Sci. 2:1365–1376.

- Donoghue AM, Wishart GJ. 2000. Storage of poultry semen. Animal Reprod Sci. 62:213–232. 10.1016/S0378-4320(00)00160-3

- Douard V, Hermier D, Blesbois E. 2000. Changes in turkey semen lipids during liquid in vitro storage. Biol Reprod. 63:1450–1456. 10.1095/biolreprod63.5.1450

- Douard V, Hermier D, Magistrini M, Blesbois E. 2003. Reproductive period affects lipid composition and quality of fresh and stored spermatozoa in Turkeys. Theriogenology. 59:753–764. 10.1016/S0093-691X(02)01086-5

- Froman DP, Feltmann AJ, Rhoads ML, Kirby JD. 1999. Sperm mobility: a primary determinant of fertility in the domestic fowl (Gallus domesticus). Biol Reprod. 61:400–405. 10.1095/biolreprod61.2.400

- Giesen AF, Sexton TJ. 1983. Beltsville poultry semen extender. 9. Effect of storage temperature on turkey semen held eighteen hours. Poultry Sci. 62:1305–1311. 10.3382/ps.0621305

- Hocking PM. 2009. Biology of breeding poultry. Abingdon: CABI.

- Iaffaldano G, Rosato MP, Manchisi A, Centoducati G, Meluzzi A. 2005. Comparison of different extenders on the quality characteristics of turkey semen during storage. Italian J Anim Sci. 4:513–515.

- Iaffaldano N, Manchisi N, Rosato MP. 2007. The preserve ability of turkey semen quality during liquid storage in relation to strain and age of males. Anim. Reprod Sci. 109:266–273. 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2007.11.024

- King LM, Holsberger DR, Donoghue AM. 2000. Correlation of CASA velocity and linearity parameters with sperm mobility phenotype in turkeys. J Androl. 21:65–71.

- Kotłowska M, Dietrich G, Wojtczak M, Karol H, Ciereszko A. 2007. Effect of liquid storage on amidase activity, DNA fragmentation and motility of turkey spermatozoa. Theriogenology 67:276–286. 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2006.07.013

- Kročková J, Massányi P, Toman R, Danko J, Roychoudhury S. 2012. In vivo and in vitro effect of bendiocarb on rabbit testicular structure and spermatozoa motility. J Environ Sci Health A. 47:1301–1311. 10.1080/10934529.2012.672136

- Massányi P, Chrenek P, Lukáč N, Makarevich AV, Ostró A, Živčák J, Bulla J. 2008. Comparison of different evaluation chambers for analysis of rabbit spermatozoa motility parameters using CASA system. Slovak J Anim Sci. 41:60–66.

- Miškeje M, Slanina T, Petrovičová I, Massányi P. 2013. The effect of different concentration of fallopian tubes (oviducts) secretion extract on turkey spermatozoa motility in vitro. J Microbiol Biotechnol Food Sci. 2:13.

- Morrell JM, Persson B, Tjellstrőm H, Laessker A, Nilsson H, Danilova M, Holmes PV. 2005. Effect of semen extender and density gradient centrifugation on the motility and fertility of turkey spermatozoa. Reprod Dom Anim. 40:522–525. 10.1111/j.1439-0531.2005.00620.x

- Rosato MP, Cinone M, Manchisi A, Meluzzi A, Iaffaldano N. 2006. Changes on the quality characteristics of stored semen during reproductive period of Hybrid toms. XII European Poultry Conference; 2006 Sep 10–14; Verona (Italy): World's Poultry Science Association (WPSA).

- Semen Quality. Hybrid turkeys [Internet]. 2007. Ontario: hybrid a hendrix genetics company. [cited 2013 Jul 22]. Available from: http://www.hybridturkeys.com/hybrid-resources/infosheets/

- Slanina T, Miškeje M, Knížat L, Mirda J, Massányi P. 2012. The effect of different concentration of trehalose on turkey spermatozoa motility in vitro. J Microbiol Biotechnol Food Sci. 1:573–582.

- Slanina T, Slyšková L, Kraska K, Massányi P. 2013. Effect of different concentration of caffeine on turkey spermatozoa motility in in vitro conditions at 41°C. J Microbiol Biotechnol Food Sci. 2:9.

- Thurston R. 1995. Storage of poultry semen above freezing for twenty-four to forty-eight hours. Proceeding of the First International Symposium on Artificial Insemination of Poultry; 1994 June 17–19; Savoy (IL): Bakst and Wishart; p. 107–122.

- Tvrdá E, Kňažická Z, Lukáčová J, Schneidgenová M, Goc Z, Gren A, Szabo C, Massányi P, Lukáč N. 2013. The impact of lead and cadmium on selected motility, prooxidant and antioxidant parameters of bovine seminal plasma and spermatozoa. J Environ Sci Health A. 48:1292–1300. 10.1080/10934529.2013.777243