ABSTRACT

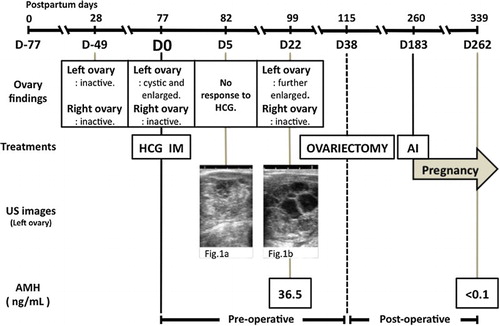

A 23-month-old Holstein cow had a multi-cystic and enlarged left ovary detected by rectal palpation and ultrasonography. The plasma anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) concentration was 36.5 ng/ml, which is higher than normal. From the clinical history and plasma AMH levels, a granulosa cell tumour (GCT) was diagnosed. Affected ovary was removed by ovariectomy, and GCT was confirmed with histopathological findings. The cow was artificially inseminated at 145 days after ovariectomy, and conceived. The plasma AMH concentration declined at 224 days after removal of affected ovary to less than 0.1 ng/ml, and recovery of fertility was achieved. In conclusion, measurement of plasma AMH levels combined with rectal palpation and ultrasonography examinations could be useful in clinical diagnosis of bovine GCT.

1. Introduction

Granulosa cell tumours (GCTs) are the most common ovarian tumours in cattle (Kumamoto et al. Citation1998; Perez-Martinez et al. Citation2004). Cows with GCTs may show nymphomania and abnormal udder development (Leder et al. Citation1988) or may not show any clinical signs (Zachary and Haliburton Citation1983; Inokuma et al. Citation2006; Haneishi et al. Citation2008). The GCTs are generally unilateral, and the contralateral ovary is frequently small and inactive due to the cessation of oestrus cycle activity (Kumamoto et al. Citation1998; Meganck et al. Citation2010; Kitahara et al. Citation2012). Proper diagnosis of GCTs might be difficult in the field-level examinations, such as rectal palpation and ultrasonography (Zulu et al. Citation2000; Masseau et al. Citation2004; Meganck et al. Citation2010; Kitahara et al. Citation2012). The disease has to be distinguished from ovarian cyst, oophoritis and ovarian abscesses (Zulu et al. Citation2000; Kitahara et al. Citation2012). Thus, upon tentative diagnosis, ovariectomy has been performed to definitive diagnosis based on histopathological examination of the ovarian tissues (Leder et al. Citation1988; Haneishi et al. Citation2008). The surgical extraction of the affected ovary also resulted in the remaining ovary to become functional and to recovery of fertility (Leder et al. Citation1988; Masseau et al. Citation2004; Haneishi et al. Citation2008).

The elevation of plasma inhibin (INH) concentration has been used an indicator for the diagnosis of GCTs (Inokuma et al. Citation2006). However, recently, in mares, it was found that the sensitivity of anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) for detection of GCTs was significantly higher than that of either inhibin or testosterone (Ball et al. Citation2013). Similarly, in cattle, the measurement of plasma AMH concentration was identified as a more reliable and sensitive method to diagnose GCTs than that of the measurement of INH or ovarian steroids (Kitahara et al. Citation2012). The cut-off diagnostic concentration of plasma AMH in GCTs-affected cattle is identified as >0.36 ng/ml (El-Sheikh Ali et al. Citation2013). This report provides the information on clinical diagnosis of GCTs based on measurement of plasma AMH concentrations before surgical extraction of affected ovary, and the artificial insemination (AI) afterwards resulted in the cow pregnancy.

2. Case description

The owner of a 23-month-old Holstein cow (parity: 1) in Fukuoka prefecture, Japan, complained that the cow is still in anoestrus at 77 days after parturition (Day0; D0). The per-rectal palpation revealed that the left ovary was cystic and enlarged, while the right ovary was small and inactive. The cow has been checked per-rectally at 28 days after parturition and found that both ovaries were small and inactive and had no abnormally enlarged uterus. There was no past medical history of puerperal diseases, such as dystocia, retained placenta or postpartum uterine infection. The presumptive diagnosis was made as ovarian cysts, and treated with intramuscular (IM) administrations of HCG (3000IU; GONATROPIN®3000, ASKA Animal Health Ltd, Tokyo, Japan). The cow did not show any response to the treatment when re-checked after 5 days (D5). Thus, a trans-rectal ultrasonography was performed, which revealed that the left ovary had a mass with a solid appearance, with the right ovary remained small ((a)). Re-observation of the cow at D22 showed that the left ovary was further enlarged and merged multicystic ((b)). A blood sample was collected, haematological and biochemical evaluations, such as complete blood count, differential leukocyte count, liver and kidney function tests, total cholesterol, total protein, albumin and glucose levels, were performed. The plasma AMH concentration also was measured according to a previous report (El-Sheikh Ali et al. Citation2013).

Figure 1. Ultrasonographic appearance of affected left ovary. On D5, the left ovary revealed mass with solid appearance (a). On D22, the left ovary become enlarged and merged multicystic appearance (b). Bar = 10 mm.

The haematological and biochemical findings were all within the normal range. The plasma AMH concentration was 36.5 ng/ml, which is markedly higher than the reference diagnostic cut-off point for bovine GCT (El-Sheikh Ali et al. Citation2013). Based on the case history and clinical findings and high AMH concentration, the cow was re-diagnosed as having left ovary (unilateral) GCT.

A left ovariectomy was performed on D38. On the day of surgery, the cow had no feed in the morning, but water, to reduce ruminal contents. The cow was placed in stocks, and segmental dorso-lumbar epidural analgesia was performed using a mixed solution containing 0.3 ml 0.2% Xylazine (Sedeluck 2% Injection; Nippon Zenyaku Kogyo Co., Ltd; Fukushima, Japan), and 3.0 ml 2.0% lidocaine (Lidocaine injection 2%; Pfizer, Germany). Left ovary was exteriorized and extracted after left flank laparotomy on standing. The ovarian pedicle was ligated with overlapping transfixion. The dimension of the extracted ovary was 60 mm × 70 mm × 70 mm and 117 g in weight ((a)). The extracted ovary had no adhesion to intra-abdominal organs with smooth surface and no malignant appearance. Many various-sized cystic follicles filled with serous fluids and solid parts were observed at the cut surface ((b)).

Figure 2. Gross appearance of the extracted left ovary. The extracted left ovary (60 mm × 70 mm × 70 mm, 117 g in weight) was coated smooth surface (a). The cut surface revealed many various-sized cystic follicles filled with yellowish serous fluids and greyish-yellow solid parts (↑) (b).

The tissue samples from extracted ovary were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin wax, and sectioned at 5 μm. Sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin (HE). The mass was consisted of various-sized follicular structures contained eosinophilic fluid and haemorrhage-like Call-Exner body. The neoplastic cells formed structures were follicular, tubular, and solid. The neoplastic cells resemble granulosa cells, which were lined with multiple layers, and the cells had eosinophilic cytoplasm and moderately large nucleus containing coarse chromatin. The nuclear atypia and mitotic figure were slight, and malignant findings were not noted (). Accordingly, the tumour was diagnosed as a GCT.

Figure 3. Microscopic appearance of the section of the extracted left ovary. The tissues were observed as various-sized follicular structures contained eosinophilic-fluid-like Call-Exner body (a: ×100). The neoplastic cells in parts of the tumour were also formed with tubular and solid patterns (b: ×200).

Follow-up per-rectal palpation was carried out on D51 (13 days after ovariectomy), and remaining right ovary had a large cyst with approximately 30 mm of the diameter, but the cow was not treated. The cow showed oestrus spontaneously on D183, and was artificially inseminated. Confirmation of pregnancy was performed on D262 (224 days after ovariectomy). At that time the plasma AMH concentrations declined to less than 0.1 ng/ml. Clinical courses of this case, including ovary findings, treatment, ultrasound images and AMH levels, are summarized in .

3. Discussion

GCTs have been reported with various parities and reproductive statuses, with the variation in weights and sizes of the affected ovaries (Kikuchi et al. Citation1995; Meganck et al., Citation2010; Kitahara et al. Citation2012). Moreover, ultrasonography of GCTs also showed various appearances. Thus, the above-mentioned methods are not suitable for definitive diagnosis of GCTs. Nevertheless, it was believed that the definitive diagnosis of GCTs could only be made based on histopathological examination of extracted ovary (Haneishi et al. Citation2008; Meganck et al. Citation2010; Kitahara et al. Citation2012). In the present report, the cow had no history of puerperial disease or postpartum infection. Although abnormal uterus or ovaries were not observed during the routing per-rectal palpation at 28 days after parturition, the abnormally enlarged left ovary was observed by rectal palpation at 77 days after parturition (D0). And then, the left ovary was observed further enlarged and merged multicystic appearance regardless of treatment for ovarian cyst at 99 days after parturition (D22). Therefore, there is a possibility that the GCTs have been developed between 28 and 99 days after parturition.

The plasma AMH concentration was markedly higher in the present case, which indicates the presence of GCTs (El-Sheikh Ali et al. Citation2013), and declined after surgical removal of the affected ovary. Under field conditions, although the clinical cure of GCTs seems to be determined that the cow become pregnant in the previous report (Leder et al. Citation1988; Haneishi et al. Citation2008), we determined more certainly by confirming both pregnancy (recovery of fertility) and reduction in AMH concentration in this report. It was reported that the immunoreactive AMH expressed in the neoplastic granulosa cells with high blood AMH levels, and blood AMH levels had declined to normal concentrations within a week after surgical extraction of GCTs (Kitahara et al. Citation2012; El-Sheikh Ali et al. Citation2013). The finding of this report is comparable with the above studies that the elevated the plasma AMH concentration declines after surgical removal of the affected ovary.

This report provides evidences for possible clinical diagnosis of GCTs using the measurement the plasma AMH concentrations combined with routing diagnostic tools, such as rectal palpation and ultrasonography examinations. On the other hand, a recent report (El-Sheikh Ali et al. Citation2015) shows the possibility of spontaneous recovery of bovine GCT in Japanese Black heifer. In their report, the heifer had a plasma AMH concentration of 4.42 ng/ml on D0 (Day0), and then plasma AMH concentration declined to 0.2 ng/ml prior to ovariectomy on D85 (Day85). The plasma AMH concentration of this report was markedly higher than that of above report. Indeed, in previous reports, the plasma AMH concentrations in cows with GCTs have shown a wider range (0.36–481.07 ng/ml) (Kitahara et al. Citation2012; El-Sheikh Ali et al. Citation2013; El-Sheikh Ali et al. Citation2015). Thus, it seems to be controversial about the diagnostic levels of AMH concentrations for bovine GCTs. Accordingly, further studies might be required to establish diagnostic reference range of AMH levels for determination of ovariectomy with GCTs. Thus, careful clinical examinations and monitor plasma AMH concentration prior ovariectomy might be useful to avoid invasive surgery and to improve accuracy of diagnosis.

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, the results of the present study indicate that the measurement of plasma AMH levels combined with rectal palpation and ultrasonography examinations is extremely important as a non-invasive simple method to make a definitive and early diagnosis of GCTs and to restore the fertility.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Ball BA, Almeida J, Conley AJ. 2013. Determination of serum anti-Müllerian hormone concentrations for the diagnosis of granulosa-cell tumors in mares. Equine Vet J. 45:199–203. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.2012.00594.x

- El-Sheikh Ali H, Kitahara G, Nibe K, Yamaguchi R, Horii Y, Zaabel S, Osawa T. 2013. Plasma anti-Müllerian hormone as a biomarker for bovine granulosa-theca cell tumors: comparison with immnoreactive inhibin and ovarian steroid concentrations. Theriogenology 80:940–949. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2013.07.022

- El-Sheikh Ali H, Kitahara G, Torisu S, Nibe K, Kaneko Y, Hidaka Y, Osawa T. 2015. Evidence of spontaneous recovery of granulosa-theca cell tumour in a heifer: a retrospective report. Reprod Domest Anim. 50:696–703. doi: 10.1111/rda.12555

- Haneishi T, Okita K, Uchida K, Sumiyoshi S, Tani M, Kamimura S. 2008. Two cases of pregnant Holsteins after removal of ovarian granulosa cell tumors. J Jap Vet Med Assoc. 61:372–375. doi: 10.12935/jvma1951.61.372

- Inokuma M, Osawa T, Hara S, Kaketa K, Atsumi T, Watanabe G, Taya K, Miyake Y. 2006. Endocrinological characteristics in two Japanese black cows with granulosa cell tumor. J Jap Vet Med Assoc. 59:746–749. doi: 10.12935/jvma1951.59.746

- Kikuchi K, Okada K, Suzuki T, Ohba H, Kaneda Y. 1995. A case of ovarian granulosa cell tumor in a peripartus cow. J Jap Vet Med Assoc. 48:541–543. doi: 10.12935/jvma1951.48.541

- Kitahara G, Nambo Y, El-Sheikh Ali H, Kajisa M, Tani M, Nibe K, Kamimura S. 2012. Anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) profiles as a novel biomarker to diagnose granulosa-theca cell tumors in cattle. J Reprod Dev. 58:98–104.

- Kumamoto K, Tenjinki T, Sekiguchi H, Uchida K, Yamaguchi R, Tateyama S. 1998. Bovine tumors detected at Miyakonojo meat inspection office of Miyazaki prefecture during 1974–1996. J Jap Vet Med Assoc. 51:449–452. doi: 10.12935/jvma1951.51.449

- Leder RR, Lane VM, Barrett DP. 1988. Ovariectomy as treatment for granulose cell tumor in a heifer. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 192:1299–1300.

- Masseau I, Fecteau G, Desrochers A, Francoz D, Lanthier I, Vaillancourt D. 2004. Hemoperitoneum caused by the rupture of a granulose cell tumor in a Holstein heifer. Can Vet J. 45:504–506.

- Meganck V, Govaere J, Vanholder T, Vercauteren G, Chiers K, des Kruif A, Opsomer G. 2010. Two atypical cases of granulosa cell tumours in Belgian blue heifers. Reprod Domest Anim. 46:746–749. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0531.2010.01717.x

- Perez-Martinez C, Duran-Navarrete AJ, Garcia-Fernandez RA, Espinosa-Alvarez J, Escudero Diez A, Garcia-Iglesias MJ. 2004. Biological characterization of ovarian granulosa cell tumours of slaughtered cattle: assessment of cell proliferation and oestrogen receptors. J Compat Pathol. 130:117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpa.2003.09.007

- Zachary JF, Haliburton JC. 1983. Malignant granulosa cell tumor in an Angus cow. Vet Pathol. 20:506–509. doi: 10.1177/030098588302000417

- Zulu VC, Mwanza A, Patel OV, Makondo KJ, Bhaiyat MI. 2000. Ultrasonographic findings of an ovarian abscess in a cow. J Vet Med Sci. 62:757–758. doi: 10.1292/jvms.62.757