ABSTRACT

Navicular syndrome causes chronic lameness and attenuates the exercise performance. Several shoeing methods have been implemented, but their success has been inconsistent. The objective of this study was to develop a diagnostic aid to select the appropriate shoeing method for the treatment of navicular syndrome. Five equestrian horses with chronic lameness were studied. The lameness examination, then unilateral anaesthetics and trotting after each point of administration were performed until no lameness sign. Radiographs were later taken of the affected hooves. The horses were diagnosed with navicular syndrome with unilateral palmar pain, z bar shoes were applied on the lame legs. Gait was analysed before shoeing and 5 min, 2, 4 and 8 weeks after shoeing except for horse no. 3, for which the evaluation at 8 weeks was omitted. Horses no. 2 and 3 showed a significant decrease in lameness score at 2 weeks and progressive decrease at 4 or 8 weeks. Horses no. 1, 4 and 5 demonstrated a significant reduction in lameness score at 4 weeks and substantial decreases at 8 weeks after shoeing. Although a limited number of animals, unilateral perineural anaesthesia on the lame leg facilitates the selection of z bar shoeing for navicular syndrome treatment.

Introduction

In horses, navicular syndrome is the most common cause of chronic forelimb lameness (Ackerman et al. Citation1977; Rose Citation1996), which may result from an increasing pressure in the deep digital flexor tendon against the navicular bone. Furthermore, navicular syndrome usually contributes to bilateral forelimb lameness (Stashak Citation1987; Rose Citation1996). The diagnostic techniques for navicular syndrome are based on clinical signs of chronic intermittent forelimb lameness, increasing lameness following flexion and extension of the digit, and positive response to palmar digital nerve block (Østblom et al. Citation1984; Rose Citation1996). A palmar digital nerve block is commonly employed for localization of pain in the palmar region of the hoof which contains the navicular bone and associated structure (Stashak Citation1987). Several predisposing factors are relevant to the development of navicular syndrome, such as abnormal hoof conformation, frequent exercise on a hard surface, and inappropriate hoof trimming and shoeing (Rooney Citation1969; Adams Citation1974; Dyson Citation2003). Accordingly, the principle managements for navicular syndrome include rest, controlled exercise, medical treatment (Soto and Barbará Citation2014; Whitfield et al. Citation2016), and corrective shoeing (Schoonover et al. Citation2005).

Corrective shoeing has been advocated to manage abnormalities of hoof conformation and to relieve foot pain. Moreover, previous studies demonstrated that an application of an egg bar to horses with navicular syndrome improved their performance (Østblom et al. Citation1984; Leach Citation1993). In addition, fitting with extensive shoes beyond the outer part of the hoof wall at the quarter region and caudal extent of the heel is thought to alleviate mechanical compression on the navicular apparatus and to support the palmar region (Turner Citation1989). Nevertheless, the potential benefit of these shoeing methods has yet to be consistent. Consequently, this study aimed to develop an additional diagnostic aid for the selection of shoeing method for the treatment of horses with navicular syndrome.

Materials and methods

Animals

Five equestrian horses consisting of four show jumping (horse no. 1, 2, 4 and 5) and one eventing horses (horse no.3) (4 gelding and 1 mare) ages ranged from 10–21 years (mean 14.6 ± 4.4 years), and weighing ranged from 420–540 kg (mean 457.6 ± 47.6 kg) with a history of chronic intermittent lameness were included in the study. All horses had participated in national and international equestrian events until the lameness was noticed. They were housed in 9 m2 standard stalls and fed with commercial pellet three to four times a day. In addition, hay and water were provided ad libitum. They were also routinely shod with custom metal shoes by a professional farrier at 4-week intervals.

Lameness examination

The horses were examined for lameness and scored from 0 to 5 according to the American Association of Equine Practitioners (AAEP) (Anon Citation1991): 0 meant no lameness, and 5 meant minimal weight bearing or unable to move. The lameness examination was performed as reported previously (Rose Citation1996). Briefly, the horses were trotted off to identify the lame legs. After that, a hoof tester was applied on the sole, quarter, and frog regions to detect negative or positive responses. Thereafter, an extension test was performed by placing a wooden block 2–3 cm high under the toe region of the lame leg, simultaneous with lifting the opposite foreleg to create hyperextended position of the lame leg for 2 min. Then the horses were trotted and evaluated for the degree of lameness afterwards. Later, the fetlock joint of the lame leg was actively flexed for 2 min, and the horse was immediately trotted off. A wedge test, an exertion of firm pressure by the hoof tester on the middle of the frog, was performed on the lame leg for 1 min, and the horse was trotted again. In addition, perineural anaesthesia using 2% lidocaine (L.B.S. Laboratory Ltd. Bangkok, Thailand) was applied unilaterally starting from palmar digital nerve block (medial to lateral aspect) and then abaxial nerve block (medial to lateral aspect) until no lameness was found to localize pain to the foot. The horses were trotted off after each point of local anaesthesia. Eventually, radiography was conducted to evaluate the degenerative change of the navicular bone of the lame legs.

Shoeing design and protocol

Custom metal shoes (Mustadfors Bruks, Dal Langed, Sweden) were cut at approximately one-third or half of the quarter region on the side of palmar pain based on the lameness examination. The intact branch and cut branch of the metal shoe were engaged with another piece of metal to create a modified z bar shoe that eliminated the compression on the affected palmar region. The size and shape of the z bar shoes were modified to fit and avoid a concussion on the affected region of the hooves ((a)). The affected hooves were trimmed ((b)) and shod with z bar shoes ((c,d)), while the normal limbs were shod with custom shoes according to the fundamental shoeing protocol (Poynton Citation2005).

Figure 1. The creation of z bar shoe to fit the affected limbs of the horses. The z bar shoe is created by cutting unilateral branch of metal shoe and connecting the cut branch with the intact branch by another piece of metal to produce a non-weight-bearing area (a). The affected palmar region is rasped more than another part of foot to create the non-weight-bearing area and facilitate hoof wall growth (red arrow) (b). Non-weight-bearing positions on medial side of left and right forelimbs fitted with z bar shoes respectively (c and d).

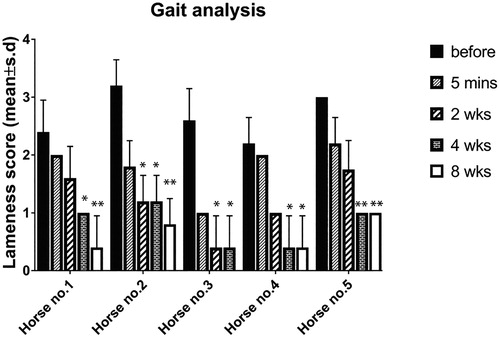

Gait analysis

Gait analysis was graded and scored from 0 to 5 according to the American Association of Equine Practitioners (AAEP) (Anon Citation1991). The horses were trotted off along an approximately 30-metre straight line before shoeing and 5 min, 2, 4 and 8 weeks after shoeing with the z bar shoe. With minor exceptions, the gait analysis at 8 weeks was omitted in horse no. 3 due to its competition programmes. The gait analyses were recorded by the digital camera (Samsung Electronics, Suwon, South Korea) and evaluated for lameness score by five equine veterinarians.

Data analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 7.04. The lameness scores from gait analyses of each horse were analysed using the Friedman test followed by Dunn's multiple comparisons test. All data were expressed as mean ± s.d. Statistical significance was considered at p < .05.

Results

Lameness examination

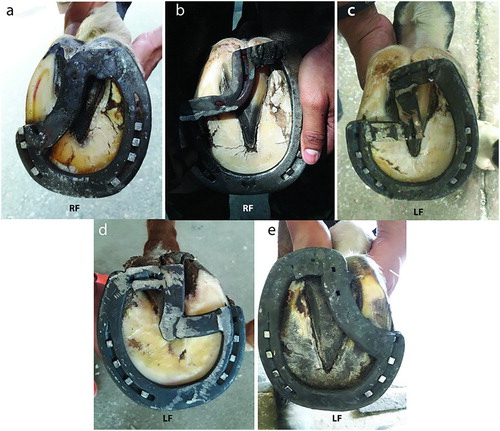

shows the results of the lameness examinations. According to the lameness examination, all horses were diagnosed as a navicular syndrome with unilateral palmar pain. Horses no. 1 and no. 3 showed medial palmar pain on the right forelimbs. Horse no. 2 showed lateral palmar pain, while horses no. 4 and 5 demonstrated medial palmar pain on the left forelimbs. The z bar shoes were selected to avoid a concussion of the affected palmar regions, and the horses were shod based on their individual lameness examinations ((a–e)).

Figure 2. The application of z bar shoes on the affected limbs of the horses. The horse no. 1 (a) and no. 3 (b) are shod with medial palmar non-weight bearing z bar shoe on the right forelimb. The horse no. 2 (c) are shod on the left forelimb with lateral palmar non-weight bearing Z bar shoe, while the horse no. 4 (d) and no. 5 (e) are shod on the left forelimb with medial palmar non-weight-bearing z bar shoes. LF; left forelimb, RF; right forelimb.

Table 1. Clinical examination of horses with chronic foot pain performed by the application of hoof tester, extension test, flexion test, wedge test, and regional anaesthesia.

Gait analysis

Prior to being fitted with the z bar shoes, an average lameness score of all horses was 2.6 ± 0.5. Horses no. 2 and 3 showed a significant decrease in lameness score at 2 weeks after shoeing (p < .05 for both) and maintained that decrease at 4 (p < .05 for both) or 8 weeks (p < .01; horse no. 2) after shoeing. The onset of significant decrease in lameness score of horses no. 1, 4 and 5 was found at 4 weeks after shoeing (p < .05; horses no. 1 and 4, p < .01; horse no. 5). The lameness score in horse no. 1 further decreased at 8 weeks (p < .01), while the score in horses no. 4 and 5 maintained that decrease at 8 weeks (p < .05; horse no. 4, p < .01; horse no. 5) after shoeing ().

Discussion

Although this study has included a limited number of animals, it would demonstrated an apparent improvement of lameness score in the horses with navicular syndrome after using z bar shoeing technique. As expected, the horses showed a trend to decrease in lameness sign 5 min after shoeing and progressive improvement at 2–8 weeks after shoeing. Our findings indicate that unilateral perineural anaesthesia aids the selection of z bar shoeing technique to resolve the chronic foot pain caused by navicular syndrome.

The diagnostic criteria to indicate navicular syndrome consist of chronic progressive forelimb lameness, pain in the palmar region of the hooves, and no other obvious causes of pain in the palmar heel region. Moreover, the lameness signs were considerably improved after palmar digital nerve block (Rose Citation1996). According to the lameness examination, we found that the horses in our study showed unilateral forelimb lameness rather than bilateral forelimb lameness as reported elsewhere (McGuigan and Wilson Citation2001). Interestingly, after each local anaesthetic injection and trotting off were performed, the horses showed unilateral palmar pain of the lame legs. Radiography was used to confirm the changes of navicular bone (Douglas and Williamson Citation1970; Rose Citation1996), visualizing the radiographic abnormalities of the navicular bone as reported previously (Dyson Citation2003) (supplement file; Fig S1). The horses are, therefore, diagnosed with navicular syndrome. This result led to select the z bar shoe technique for the treatment of horses in our study. It is implied that unilateral pain localization on the lame leg was a decisive step for the selection of corrective shoeing technique in horses with navicular syndrome.

The treatments for the disease were administered according to the protocol reported previously (Leach Citation1993; Schoonover et al. Citation2005). The former study illustrates that the egg bar shoe could be applied as an additional tool to relieve the signs of navicular syndrome (Østblom et al. Citation1984). Three out of five horses (no. 1, 2 and 5) that had suffered from chronic foot pain (for 12 and 24 months) were shod with egg bar shoes for 4 consecutive shoeing programmes. Nevertheless, this shoeing technique contributed to only temporary relief of lameness signs; the recurrence of lameness was later observed. Recurrent lameness might result from the repeated concussion at the affected region by the bar shoe. Of note, the lameness scores of all horses in our study tended to decrease immediately after fitting with the z bar shoe, and the horses continuously showed marked improvement of lameness score without medical treatments during the study period. More importantly, the horses have been further followed up for lameness scoring for 32–40 weeks after shoeing. Intriguingly, horses no. 1 and 2 still demonstrate no lameness, and horses no.3, 4 and 5 show almost no lameness after fitting with the z bar shoe (supplementary video clips). It is plausible that the repeated concussion on the affected portion could be abolished by fitting with the z bar shoe. Then foot pain was alleviated, and in turn, the exercise performance of the horse was restored.

Because navicular syndrome causes the contraction of the heel-bulb area and the collapse of the heel forward to toe region (Leach Citation1993), the affected quarter areas of the limbs in all horses have been rasped as much as possible not only to reduce the compression on the affected region, but also to eliminate collapse and promote the growth of the hoof wall at the affected palmar region. The limitation of this study is the small sample size. Further study with a larger sample is required to validate the effectiveness of this shoeing process for navicular syndrome.

Conclusion

Unilateral perineural anaesthesia on the lame leg facilitates the selection of the z bar shoeing technique that has a potential to resolve chronic lameness caused by navicular syndrome. Therefore, shoeing in horses with navicular syndrome should be carried out in close liaison with an equine practitioner to localize the foot pain prior to selecting the shoeing procedure.

TAAR_1588736_Supplementary_Fig_S1

Download MS Word (731 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank MG. Kittipan Chupiputt, Chief of Veterinary Service, Royal Thai Army, COL. Chaiya Klinpayom, a director of army animal hospital, COL. Vithai Laithomya, a commander of Royal Stable Unit, Mr. Nagorn Kamolsiri, Miss Sailub Lertratanachai, and Miss Siengsaw Lertratanachai for allocation of their horses in this study. The authors would like to thank SubLt. Phattaraphong Suan-aoy for practical assistance in animal restraint and clinical examination. The great farrier work done by SM1 Somsak Tibbunrueang, SM1 Somchai Thanoorat, SM1 Thongchai Potipan, Sgt. Chetrat Treesoon, and Cpl. Thongpet Wandee, is also appreciated. Assistant Professor Atthaporn Roongsitthichai was thanked for language revision. M. C. was responsible for study design, clinical diagnosis, modify the z bar shoe, data collection and interpretation, manuscript preparation and revision. W. S., E.T., K. K. and C. P. contributed to data collection and interpretation. All authors approved the final manuscript for publication.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Metha Chanda http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8436-7330

References

- Ackerman N , Johnson J , Dorn C. 1977. Navicular disease in the horse: risk factors, radiographic changes, and response to therapy. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 170:183–187.

- Adams OR. 1974. Lameness in horses. Philadelphia (PA ): Lea&Febiger ; p. 250.

- Anon . 1991. Guide for veterinary service and judging of equestrian events. Lexington (KY ): American Association of Equine Practitioners.

- Douglas SW , Williamson HD. 1970. Veterinary radiological interpretation. Philadelphia (PA ): Lea & Febiger.

- Dyson SJ. 2003. Navicular disease and other soft tissue causes of palmar foot pain. In: Diagnosis and management of lameness in the horse. Elsevier; p. 286–299. doi:10.1016/B978-0-7216-8342-3.50037-1.

- Leach D. 1993. Treatment and pathogenesis of navicular disease (‘syndrome’) in horses. Equine Vet J. 25:477–481. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.1993.tb02997.x

- McGuigan M , Wilson A. 2001. The effect of bilateral palmar digital nerve analgesia on the compressive force experienced by the navicular bone in horses with navicular disease. Equine Vet J. 33:166–171. doi: 10.2746/042516401778643363

- Østblom L , Lund C , Melsen F. 1984. Navicular bone disease: results of treatment using egg-bar shoeing technique. Equine Vet J. 16:203–206. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.1984.tb01905.x

- Poynton AP. 2005. Shoe and shoeing method. Google Patents.

- Rooney JR. 1969. Biomechanics of lameness in horses. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins Co. London: Bailliere, Tindall and Cassell; p. xiv+259.

- Rose R. 1996. Navicular disease in the horse. J Equine Vet Sci. 16:18–24. doi: 10.1016/S0737-0806(96)80061-X

- Schoonover MJ , Jann HW , Blaik MA. 2005. Quantitative comparison of three commonly used treatments for navicular syndrome in horses. Am J Vet Res. 66:1247–1251. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.2005.66.1247

- Soto SA , Barbará AC. 2014. Bisphosphonates: pharmacology and clinical approach to their use in equine osteoarticular diseases. J Equine Vet Sci. 34:727–737. doi: 10.1016/j.jevs.2014.01.009

- Stashak TS. 1987. Adams’ lameness in horses. Philadelphia (PA ): Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Turner TA. 1989. Diagnosis and treatment of the navicular syndrome in horses. Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract. 5:131–144. doi: 10.1016/S0749-0739(17)30607-7

- Whitfield CT , Schoonover MJ , Holbrook TC , Payton ME , Sippel KM. 2016. Quantitative assessment of two methods of tiludronate administration for the treatment of lameness caused by navicular syndrome in horses. Am J Vet Res. 77:167–173. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.77.2.167