ABSTRACT

In recent years, different patterns of piebald/skewbald coat colour have become popular in horses. The tobiano pattern may appear in one of three forms: minimal, classic or maximal. The minimal variant can occur only as white spots on legs (crypto-tobiano), which may result in misclassification of the horse as solid-coloured with white markings. In Hucul horses it is particularly important to accurately determine the real coat colour because the breed standard specifies that white markings disqualify the animal from breeding. In Hucul horses, the tobiano pattern often shows as crypto-tobiano and is wrongly classified as white markings in official documentation of horses. The most reliable way for correct classification of coat colour is to analyse DNA for the presence of inversion in chromosome 3 (ECA3), which conclusively confirms or rules out the presence of the tobiano gene in the problematic horses.

Introduction

Hucul horses were bred within the territory of Bukovina and the Eastern Carpathians, and the first written record of them from 1603 comes from Dorohostajski’s book ‘Hippica’. At that point, the author already described Huculs as excellent mountain horses which prove themselves in difficult conditions. This is still the case as Hucul horses, being a Polish native and primitive breed, are known for their endurance, longevity and courage. Hucul horses are one of the oldest primitive breeds obtained from crossing of horses of different breeds like Tarpans, Przewalski horses, but also Arab, Turkish, Tartar horses and horses with Noric blood (Hollander Citation1938; Hroboni Citation1968).

Huculs are an excellent example of material culture heritage, a natural and extant breeding relict. Currently in Poland, Hucul horses participate in the genetic resources conservation programme. The programme’s priority is to maintain genetic variability, which enables appropriate focus on breeding works and preservation of the protected population of Hucul horses as a genetic reserve. The first stud farm of Hucul horses was established in 1856 in Łuczyna in Poland. In 1994, the Hucul International Federation (HIF) including all members (countries) associated with breeding Huculs, was established in Gładyszów in Poland. Hucul horses are bred in many countries: Romania, Austria, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovakia, Ukraine as well as Germany and France. Amongst HIF members, Poland stands out as the country with the largest herd. In relation to this, in May 2003, during an official meeting of the organization, the Polish stud-book of the Hucul horses was adopted as the main stud-book of Origin of the Hucul Horses (Tomczyk-Wrona Citation2006b; IZ PIB Citation2010). Currently, there are about 1600 breeding mares in Poland compared to 432 in the Czech Republic, 273 in Hungary, 129 in Slovakia, and 90 in Austria (PZHK data Citation2018).

In 2000, the Polish Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development approved the implementation of a conservation programme for Hucul horses. The programme contains guidelines concerning the scope and breeding working methods as well as the tasks involving protection of in-situ and ex-situ. In 2002, the implementation of the programme was taken over by the National Research Institute of Animal Production. In Poland, breeders can be co-financed from the European Union budget and from national funds for raising Huculs as an endangered local breed. This kind of financial support is included in the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development – Rural Development Programme (Package 7 ‘Preservation of endangered animal genetic resources in agriculture’) (IZ PIB Citation2010; Martyniuk and Polak Citation2010).

The population growth of Hucul horses over the last few years has been the consequence of not only financial support, but primarily of the possibility for the breed’s comprehensive use. Huculs prove themselves in team disciplines, hippotherapy and recreation as well as agrotourism, a field which is developing more and more. For some time, they have also been used in trekking rides which are becoming popular. The rides take place in locations like the Bieszczady Mountains, where Hucul horses work excellently due to their strength and adaptation to mountain trekking as well as low excitability (Runge Citation1921; Brzeski et al. Citation1958; Kosiniak-Kamysz et al. Citation2000; Gancarz Citation2006).

Following Poland’s breeding losses during the Second World War (1939–1945), the rebuilding of the Hucul population commenced. As a result of many years of work, in 2002 the number of mares entered into the main stud-book was 515. In 2005, this number increased to 790, whilst 10 years later this number almost doubled and was 1561 in 2015. The share of Hucul mares in the conservation programme also increased significantly, from 64.1% in 2005 to 87.9% in 2017 () (Pasternak Citation2016; PZHK data Citation2018).

Table 1. Number of Hucul mares entered into the main stud-book and their share in the genetic resources conservation programme in 2005–2017 (Pasternak Citation2016; PZHK data Citation2018).

In recent years, both internationally and domestically, the discussion concerning the Huculs’ coat colour has intensified. The problem was related to the distinguishing of white markings from the piebald (black and white patches) / skewbald (other colour – chestnut, bay, etc. and white patches) coat colour, which has become fashionable, valued and in demand. It should be emphasized that in his book Pruski (Citation1960) regarded piebald/skewbald as a typical characteristic of Hucul horses. However, it can be noticed that selection aimed at obtaining Hucul horses of these coat colour has recently been criticized and become controversial in the breeding community.

Genetic background of tobiano pattern in Hucul horses

The white spots which characterize piebald/skewbald Hucul horses correspond to the tobiano pattern (completely dominant To allele) (Stachurska and Jansen Citation2015; Pasternak et al. Citation2018). The authors of this study claim that phenotypic distinction of heterozygotes from homozygotes is not possible, as in both cases the coat pattern may be similar (Sponenberg and Bellone Citation2017). Horses with a classic tobiano pattern are characterized by white legs, vertically arranged white patches and facial markings which may occur on the usually solid-coloured head (). Mane and tail may be partially white, whilst the hooves may be both white and streaked. In the case of the minimal tobiano pattern (), the horse may have partially white limbs and a white streak on its mane or tail, or a small spot on its body. (Stachurska Citation2002; Sponenberg and Bellone Citation2017; APHA Citation2007). In the minimal pattern, facial markings are rather small or do not occur at all. The combination of large markings on legs and small head markings is typical for the tobiano pattern. In contrast, horses with big white markings on limbs, which are not produced by the tobiano, also have larger facial markings (Sponenberg and Bellone Citation2017). Sometimes tobiano horses are incorrectly classified as solid-coloured with white markings, which in the case of Hucul horses () may be of crucial breeding importance. Such a phenomenon, called crypto-tobiano, was mentioned by Stachurska and Jansen (Citation2015) describing the transfer to offspring of a diversified size pattern by Hucul horses with the minimally marked tobiano. It should be emphasized that inheritance of the same pattern size from father or mother is not a rule as the size of the white area is regulated by the effects of modifiers which have not been fully described yet (Rees Citation2003; Sponenberg and Bellone Citation2017; APHA Citation2007).

Figure 3. Tobiano pattern: crypto-tobiano (only encompassing white spots on legs, described in the passport as consistent with markings) (Photo: M. Pasternak).

In 2007, Brooks et al. identified the mutation causative for the development of the tobiano pattern. It was proven that on the long arm of chromosome 3, in all of the examined horses with the tobiano pattern, paracentric inversion was present. This did not occur in any of the horses without the tobiano pattern. The inversion’s distal (telomeric) breakpoint is located between the genes KDR and KIT and the proximal (centromeric) breakpoint between the genes ADH1C and UNC5C (Bailey and Brooks Citation2010). The KIT gene is also associated with the occurrence of other white patterns in horses, like roan and sabino-1 (Haase et al. Citation2009a; Hauswirth et al. Citation2013).

It was shown that the ECA3 inversion in tobiano horses covers a large region of about 43 Mbp which constitutes almost a third of the length of chromosome 3 and also makes it one of the largest inversions unlinked to any disease. It was identified in 13 different breeds of horse characterized by the tobiano pattern. In order to simplify the identification of the tobiano pattern, a PCR test was designed which enables fast and uncomplicated verification of the horse genotype (Brooks et al. Citation2007; Bailey and Brooks Citation2010).

Genetic background of white markings in Hucul horses

White markings, which can most frequently be found on the legs and head, are white areas under which the skin is not pigmented. Rieder et al. (Citation2008) proved that the markings’ general heritability is at the level of h2 > 0.5. According to Woolf (Citation1992, Citation1995), it was supposed that the heritability of facial markings is 0.69 and that of limbs is 0.68. It is supposed that 1/3 of the factors determining the presence of this trait are of a non-genetic nature. As opposed to smaller ones, larger markings are more frequently transferred to offspring (Woolf Citation1992, Citation1995).

White markings were classified as quantitative trait and the KIT gene was initially regarded as the main factor responsible for their expression (Rieder et al. Citation2008). In subsequent years, the research on this subject showed a high correlation between the MC1R gene and an increased range of the occurrence of white markings, especially in chestnut horses (Haase et al. Citation2009). Moreover, an additional QTL (quantitative trait locus) region was discovered conditioning the occurrence of white markings. It includes the MITF gene which is also related to the splashed white coat colour. The research findings proved that the MITF gene is associated with the occurrence of white markings in bay horses, whilst the KIT affects the size of markings in chestnut horses, in which they occur as a result of a functioning disorder of the MC1R gene (Rieder et al. Citation2008; Haase et al. Citation2009, Citation2013). The authors of the recent study (Haase et al. Citation2013) proved the relationship between the MITF and KIT genes and the occurrence of white markings in 26% of the examined horses. However, they also discovered new QTL regions associated with this trait. The MITF (chromosome 16), MCIR (chromosome 3) and KIT (chromosome 3) genes are highly correlated with white markings. New QTL regions were discovered within chromosomes 1, 3, 23 and 25. A relationship was proven between the locus in chromosome 25 and the occurrence of markings on forelegs in chestnut horses. On the other hand, loci in chromosomes 1 and 23 were associated with the occurrence of white markings on both forelegs and hind legs in bay horses. According to the authors, these loci explain 54% of genetic variability of this trait (Haase et al. Citation2013).

In 2017, the results of research conducted by Negro et al. were published, concerning the association of several variants of the KIT, MITF and PAX3 genes with the occurrence of white markings in Spanish horse breeds (PRE and PRMe). The authors took into consideration the size of markings as well as the basic coat colour (ASIP and MC1R genes). The research showed that the variant of the ASIP gene was negatively correlated with the size of markings on forelimbs, whilst the association analysis of MC1R variants and white markings proved no statistically significant relationship. However, a significant association between a mutation in the KIT gene and the size of facial markings and total white markings in PRMe horses was proved. Within individual populations, an association was proven between the variant in the MITF gene and facial markings in PRE horses and less white markings on forelimbs in PRMe horses. An individual analysis proved that in both breeds, horses with the KIT:p.Arg68His variant were characterized by the presence of big white markings (stars) on the forehead. It was also established that the KIT and MITF variants mentioned by the authors may together increase the range of the occurrence of white markings in both breeds. The authors suggest that the variants of KIT (KIT:p.Arg68His and g.77784972T > C) and MITF (g.20147039C > T) gene described by them may be used as selection markers for keeping or eliminating white markings (Negro et al. Citation2017). This information is important for the problem discussed in this paper (–).

Historical aspect of the Huculs’ coat colour

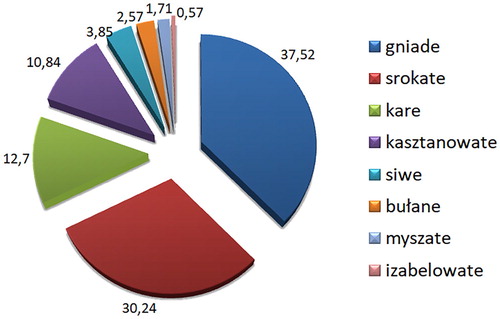

According to the current breed standard existing in Poland, Hucul horses may be bay, blue dun, tobiano, dun or black. Huculs are characterized by a black dorsal stripe. They may also have visible black striping on the shoulders and limbs. White markings, which usually occur on the limbs and head, are an undesirable trait which eliminates Hucul horses from breeding (IZ PIB Citation2010; PZHK Citation2014). Between 1925 and 1937, M. Hollander (Citation1938) carried out the classification of Hucul mares originating from the Hucul region, including coat colour ().

Figure 7. Percentage share of mares described according to their coat colour between 1925 and 1937 (Hollander Citation1938).

From the data, it emerges that 1/3 of the population assessed at that time was piebald/skewbald (). Holländer also described Huculs with white markings, claiming that in the 1920s and 30s, this trait was most common in grey (∼93%) and chestnut horses (∼73%), and least common in dun (∼33%) and black horses (∼26%). White markings also occurred in a large number of bay (∼42%) and blue dun horses (∼67%) (Hollander Citation1938). These percentages indicate the high frequency of the occurrence of these markings in Hucul horses at those times.

Table 2. Detailed structure of mare coat colour from different periods.

Brzeski et al. (Citation1958), when describing in his book the characteristics typical for Hucul horses, also listed piebald/skewbald coat colour as occurring in combination with many variants of basic coat colour. In the early 1950s, at the Tylicz stud farm, the rejection of a large number of piebald/skewbald foals began. Cywiński (Citation1958) claimed that as a consequence, many promising foals in good breed type were eliminated because of their coat colour (Cywiński Citation1958; Brzeski et al. Citation1958).

Tobiano Huculs were mainly bred in Poland where they constituted about 30% of the population in 1918–1939. Between 1962–2004, 1139 horses were entered into the Hucul stud-book, 223 of which were tobiano, which amounts to almost 20%. Many authors emphasize the fact that piebald/skewbald Huculs are in no way inferior to their solid-coloured brothers. They are equally strong, have a dorsal stripe and striping on the legs, features which indicate primitive origin. The difference is that they were not bred for military use, where solid-coloured horses proved to be most suitable (Hackl Citation1938).

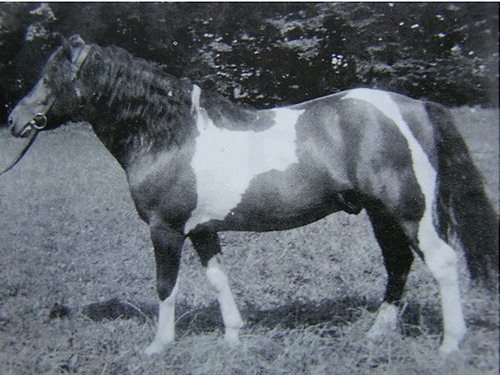

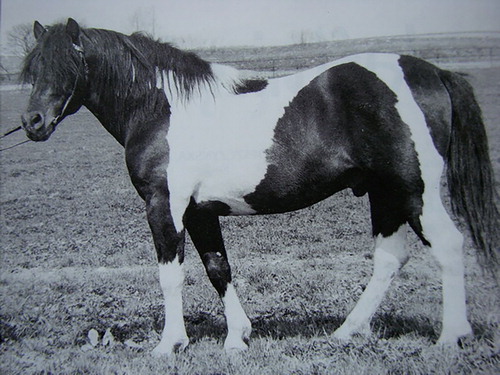

Hucul horses in Poland originate from 7 male lines and 14 female families. Amongst the founders of the female families, two mares were characterized by tobiano pattern and they were Agatka and Sroczka. Agatka gave birth to offspring, one of which was Pisanka – grandmother of Zefir (), which became famous in the later years. He sired 37 descendants, including 19 tobiano ones (Tomczyk-Wrona Citation2006a).

Figure 8. Zefir – tobiano Hucul stallion (Cukor Gurgul-5 from Larynka), Jaśmin’s sire (www.huculy.phorum.pl/viewtopic.php?t=73).

One of Zefir’s sons turned out to be an outstanding sire and 5 times golden medal winner of breeding exhibitions. This was Jaśmin, well known in the breeding community (), the leading stallion of the stud farm in Gładyszów, which had a great impact upon the popularization of breeding Hucul horses in the 80s and 90s. Over 23 years, Jaśmin sired 180 pure-breed descendants, including 81 tobiano ones (Deszczyńska et al. Citation2006; Tomczyk-Wrona Citation2006a, Citation2008; Jackowski Citation2012).

Figure 9. Jaśmin – tobiano Hucul stallion (Zefir from Dziewanna) (www.huculy.phorum.pl/viewtopic.php?t=73).

Stachurska et al. (Citation2012) calculated that 51% of the total population of Hucul horses entered into the stud-book comprised bay horses, 14.8% were blue dun and as many as 21.5% were tobiano, whilst the proportions varied dependent on the book’s section. Tobiano mares were mainly covered with bay stallions (48.7%), tobiano (32.9%) and blue dun (18.4%). For tobiano stallions, the percentage of covered mares with same coat colour was 16%.

Tobiano Huculs are also popular outside of Poland. They can be found in Czech, Austrian, German, Slovakian, and even French stud farms (Gibała Citation2012).

Breeding aspect of the Huculs’ coat colour

The problem of the tobiano pattern and white markings was discussed at the meeting of the Breeding Commission and the Board of Management of HIF in Topoľčianky in 2011. The main subject of the discussion was the concerns which arose as a consequence of a larger population of foals with white markings. The transfer of markings to offspring was attributed to tobiano parents. In the Hucul breed standard, there is an important statement from the breeding point of view according to which ‘White markings in mares are undesirable and unacceptable in stallions except for greyness. Stallions with white markings shall not be entered into the Hucul stud-book’. This clearly indicates that occurrence of white markings is a disqualifying trait in the Hucul breed (IZ PIB Citation2010; PZHK Citation2014). In the end, during the meeting, it was suggested that member countries should advise breeders to mate tobiano horses with each other, aiming at a reduction of solid-coloured foals with white markings (Gibała Citation2012). In reply to the proposal for establishing a separate studbook for tobiano Huculs and a ban on mating solid-coloured mares with tobiano stallions and ones with tobiano ancestors, it was emphasized that in 2011, out of 179 Polish breeding stallions, 57 (32%) were characterized by the tobiano coat colour. At the same time, 111 (62%) of the solid-coloured horses had tobiano ancestors and in 82 solid-coloured stallions, the share of genes originating from tobiano ancestors was as high as in horses which were phenotypically piebald/skewbald. Only 11 stallions did not have tobiano ancestors. Therefore, introducing a ban on mating solid-coloured mares with tobiano stallions or establishing separate books for tobiano Huculs would be a highly detrimental move for Poland. This would have a significant impact upon the level of in-breeding and would have a negative impact on the population of Polish Huculs (Jansen and Jansen Citation2012; Tomczyk-Wrona Citation2004).

In 2009–2011 the percentage of solid-coloured Huculs with white markings resulting from mating tobiano horses was about 6.3%. However, there is no evidence for their genotype because they were not examined for ECA3 inversion. Therefore, it is possible that some of them were of piebald/skewbald coat colour which was expressed in the form of the crypto-tobiano pattern (Gibała Citation2012). Stachurska and Jansen (Citation2015) presented examples of misclassified Huculs with the crypto-tobiano pattern in their paper.

Research has shown other cases of incorrect classification of coat colour in Hucul horses. This research demonstrated the presence of inversion in 10 out of 55 examined horses which were described in their passport as solid-coloured with white markings, meaning that the coat colour of 18% of individuals had been incorrectly classified. In reality, the horses had the crypto-tobiano pattern, the expression of which is visible mainly in the form of white spots on the legs (–) (Pasternak et al. Citation2018).

From the historical point of view, it should be emphasized that the molecular research carried out in recent years has proved that the tobiano pattern occurred in European horses as early as 1500 B.C. (Ludwig et al. Citation2009). Therefore, considering it a trait which requires separate treatment, especially in primitive horses such as Huculs, is not justified (Ludwig et al. Citation2009; Jackowski Citation2012). Jackowski (Citation2005) claims that at the beginning of the twentieth century, many Huculs had white markings at the stud farm in Łuczyna. This might indicate that in previous years, not much attention was paid to this characteristic and that it was not regarded as a disqualifying one. This agrees with Hollander’s (Citation1938) results mentioned above. Currently, however, it is erroneously believed that white markings were not typical in the primitive, pure-breed Huculs and that they occurred as a result of mixing the Polish representatives of the breed with individuals coming from abroad. This seems to be the main reason for attempts at eliminating this trait from the horses qualified for breeding.

Conclusions

On the basis of the collected information it can be stated that the correct classification of coat colour is a particularly important aspect for Hucul breeders. Mistakes made during coat colour qualification are common. In Poland, Huculs characterized by white markings are excluded from breeding even when they have the correct conformation and other traits typical for the breed standard. This indicates a crucial need for carrying out DNA testing in terms of verification of coat colour in doubtful cases. PCR tests are relatively cheap and easily accessible. In the Polish population, it is very important to prevent incorrect elimination from breeding because Huculs are valuable horses which should be strongly protected as a native breed. For this reason, it is essential to pay particular attention to preserving endangered male lines and female families, of which every single horse is precious for the breeding condition future Polish Huculs.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Marta Pasternak http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6956-6358

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Paint Horse Association (APHA). 2007. Guide to coat color genetics. 1.

- Bailey E, Brooks SA. 2010. Method for screening for a tobiano coat color genotype. Veterinary Science Faculty Patents. 1:1–30.

- Brooks SA, Lear T, Adelson D, Bailey E. 2007. A chromosome inversion near the KIT gene and the tobiano spotting pattern in horses. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 119:225–230. doi: 10.1159/000112065

- Brzeski E, Górska K, Rudowski M. 1958. Konie huculskie. PWN Warszawa. p. 5–77.

- Cywiński L. 1958. Hodowla konia huculskiego. Przegląd Hodowlany. 1:23–26.

- Deszczyńska A, Jackowski M, Kario W. 2006. Jaśminowa Legenda. Koń Polski. 12:19–24.

- Gancarz J. 2006. Wskaźniki pobudliwości nerwowej koni huculskich utrzymywanych systemem tabunowym. Annales Universitatis Mariae Curie-Skłodowska. Sectio EE Zootechnica. 24:249–255.

- Gibała M. 2012. Dokąd galopuje koń huculski … hodowca i jeździec. Rok X nr. 2(33):34–37.

- Haase B, Brooks SA, Tozaki T, Burger D, Poncet PA, Rieder S, Hasegawa T, Penedo C, Leeb T. 2009a. Seven novel KIT mutations in horses with white coat colour phenotypes. Anim. Genet. 40:623–629. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.2009.01893.x

- Haase B, Rieder S, Obexer-Ruff G, Burger D, Poncet PA, Wade C, Leeb T. 2009. White markings in the Franches-Montagnes horse population: positional cloning using genomic wide SNP association mapping. Plant & Animal Genomes XVII conference, San Diego, CA, USA: W150.

- Haase B, Signer-Hasler H, Binns MM, Obexer-Ruff G, Hauswirth R, Bellone R, Burger D, Rieder S, Wade CM, Leeb T. 2013. Accumulating Mutations in Series of Haplotypes at the KIT and MITF loci Are Major Determinants of white markings in Franches-Montagnes horses. PLOS ONE. 8(9):e75071. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075071

- Hackl E. 1938. Der Berg - Tarpan der Waldkarpaten gennant Huzul. Vien-Lipsk. p. 5–76, 262–334.

- Hauswirth R, Jude R, Haase B, Bellone RR, Archer S, Holl H, Brooks SA, Tozaki T, Penedo MC, Rieder S, Leeb T. 2013. Novel variants in the KIT and PAX3 genes in horses with white-spotted coat colour phenotypes. Anim. Genet. 44:763–765. doi: 10.1111/age.12057

- Hollander M. 1938. Koń huculski. Nakład ZHKH, Warszawa. p. 3–24.

- Hroboni Z. 1968. Konie huculskie w Polsce. Ko Pol. 2:2–6.

- IZ PIB. 2010. Program ochrony zasobów genetycznych koni rasy huculskiej. Zarządzenie Nr 19/10 z dn. 16.04.2010 r., zał. nr 1.

- Jackowski M. 2005. Polska hodowla koni huculskich. Hodowca i Jeździec. 2:21–25.

- Jackowski M. 2012. Co ze srokatymi hucułami? Koń Polski. p. 14–22.

- Jansen Ch, Jansen P-J. 2012. Czy srokate można jeszcze uratować!? http://www.club-hucul.at/Arge/kultur-tradition/7_piebalds.pdf. p. 1-21.

- Kosiniak-Kamysz K, Jackowski M, Gedl-Pieprzyca J. 2000. Przydatność koni huculskich do różnych form hipoterapii. Zeszyty Naukowe. Przegląd Hodowlany. 50:129–138.

- Ludwig A, Pruvost M, Reissmann M, Benecke N, Brockmann GA, Castaños P, Cieslak M, Lippold S, Llorente L, Malaspinas AS, et al. 2009. Coat color variation at the beginning of horse domestication. Science. 324:485. doi:10.1126/science.1172750.

- Martyniuk E, Polak G. 2010. Różnorodność biologiczna w rolnictwie. Jak promować i popularyzować rasy rodzime? Materiały Ogólnopolskiej Konferencji: Mówić o różnorodności biologicznej nie tylko w roku 2010. Uniwersytet Warszawski, 17.05.2010. p. 219–232.

- Negro S, Imsland F, Valera M, Molina A, Solé M, Andersson L. 2017. Association analysis of KIT, MITF, and PAX3 variants with white markings in Spanish horses. Anim Genet 48:349–352. doi: 10.1111/age.12528

- Pasternak M. 2016. Liczebność pogłowia klaczy wybranych rodzimych ras koni objętych programem ochrony zasobów genetycznych w latach 2005–2015. Wiadomości Zootechniczne. 3:58–71.

- Pasternak M, Gurgul A, Krupiński J. 2018. Crypto-tobiano horses as a breeding problem in the Hucul population in Poland. 69th Annual Meeting of the European Federation of Animal Science, Book of abstracts No. 24 (2018); Aug 27–31; Dubrovnik, Croatia. p. 669.

- Polski Związek Hodowców Koni (PZHK). 2014. Program hodowli koni rasy huculskiej. Warszawa. p. 3–18.

- Pruski W. 1960. Hodowla koni. Tom I. Państwowe Wydawnictwo Rolnicze I Leśne, Warszawa. p. 200, 776–788.

- PZHK data. 2018. www.pzhk.pl/hodowla/statystyka-hodowlana/.

- Rees JL. 2003. Genetics of hair and skin color. Annu. Rev. Genet. 37:67–90. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.37.110801.143233

- Rieder S, Hagger C, Obexer-Ruff G, Leeb T, Poncet P-E. 2008. Genetic analysis of white facial and leg markings in the Swiss Franches-Montagnes horse breed. J. Hered. 99(2):130–136. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esm115

- Runge S. 1921. Nauka o koniu (Hippologia). Lwów-Poznań. p. 54.

- Sponenberg DP, Bellone RR. 2017. Equine color genetics. 4th ed. Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119130628.

- Stachurska A. 2002. Identyfikacja koni. Wyd. Akademii Rolniczej w Lublinie. p. 26–33, 35–39, 59–71.

- Stachurska A, Brodacki A, Grabowska J. 2012. Allele frequency in loci which control coat colours in Hucul horse population. Czech J. Anim. Sci. 57(4):178–186. doi: 10.17221/5893-CJAS

- Stachurska A, Jansen P. 2015. Crypto-tobiano horses in Hucul breed. Czech J. Anim. Sci. 60(1):1–9. doi: 10.17221/7905-CJAS

- Tomczyk-Wrona I. 2004. Linie genealogiczne polskich koni huculskich. Wydawnictwo Cztery Litery. p. 350.

- Tomczyk-Wrona I. 2006a. Historia powstawania linii genealogicznych w hodowli koni huculskich. Wiadomości Zootechniczne. XLIV(2):76–80.

- Tomczyk-Wrona I. 2006b. Ochrona zasobów genetycznych zwierząt gospodarskich. Wiadomości Zootechniczne. XLIV(3):68–71.

- Tomczyk-Wrona I. 2008. Zasoby Genetyczne i genealogia w polskiej hodowli koni huculskich. Wydawnictwo Cztery litery. p. 15–33.

- Woolf CM. 1992. Common white facial markings in Arabian horses that are homozygous and heterozygous for alleles at the A and E loci. J. Hered. 83:73–77. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a111163

- Woolf CM. 1995. . Influence of stochastic events on the phenotypic variation of common white leg markings in the Arabian horse: implications for various genetic disorders in humans. J. Hered. 86:129–135. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a111542