ABSTRACT

One-day old goat kids were separately allocated to three treatment groups; Baladi (n = 56), Shami (n = 47) and Hybrid (n = 25). The LBW and BWG (kg/kid) of the kids were recorded at weekly intervals, and the survivability was calculated at the end of the trial. The results indicated that mean weekly Live body weight (LBW) shows a significant increase (P < 0.05) for both males and females of the three goat breeds tested. The final LBW (12-week-age) of both sexes of Shami goats was significantly (P < 0.05) higher than Baladi and Hybrid. Male goats (15.45 ± 3.65, 17.71 ± 5.23 and 15.96 ± 4.99 kg/kid) had significantly (P < 0.05) higher LBW than their female counterparts (12.52 ± 3.41, 14.92 ± 5.10 and 11.01 ± 2.64 kg/kid) in Baladi, Shami and Hybrid, respectively. Total BWG of Shami goat males and females was higher than Baladi and Hybrid breeds. The total survivability was higher in Baladi (94.64%) than in Shami (91.49%) and Hybrid (80.00%). In conclusion, the present findings indicated that production performances of goats were considerably affecting by their breed and sex, and Shami breed had supported comparatively better growth responses. Therefore, Shami goat breed might be recommended for more economic and profitable for rearing under good farming management in Jordan.

1. Introduction

Goats are well adapted under different geographical and environmental conditions including harsh climate in Jordan (Al-Dawood Citation2015, Citation2017a, Citation2017b, Citation2017c), and perform better than other domesticated ruminants. Jordanian goats have recently received much attention by researchers who so far identified and characterized several native breeds (Zaitoun et al. Citation2005; Al-Atiyat et al. Citation2012; Al-Atiyat Citation2014, Citation2017; Al-Atiyat, Alobre et al. Citation2015; Al-Atiyat, Tamimi et al. Citation2015). The most common goat breeds in Jordan are Mountain Black (Baladi), Damascus (Shami) and their crossbred between Baladi and Shami, which is called ‘Hybrid’ (Zaitoun et al. Citation2005). These breeds vary in their morphological characteristics, predominant geographical areas and production systems (Al-Atiyat et al. Citation2010). The Baladi breed represents the main breed in Jordan with 95.7%, while Shami and Hybrid breeds represent only 1.63% and 2.64%, respectively (Jordan Statistical Yearbook Citation2016). Baladi goats have moderate prolificacy and milking ability, but they are highly adapted to the arid and harsh environmental conditions (Al-Tamimi Citation2007). In contrast, Shami goats have high productivity when compared to Baladi goats in terms of milk yield, meat production and multiple births (Karagiannidis et al. Citation2000; Guney et al. Citation2006), but have less tolerant to harsh climate (Al-Tamimi et al. Citation2012).

Adaptability traits such as reproductive performance and survivability are the most important traits for goat holders (Tabbaa and Al-Atiyat Citation2009). Live body weight (LBW) and body weight gain (BWG) are important selection traits for improving production performance by selective breeding, which is considered an important component of sustainable production (Rout et al. Citation2018). Genetic parameters on growth traits have been reported in different breeds and locations worldwide (Alade et al. Citation2010; Ekambaram et al. Citation2010; Roy et al. Citation2011). Goat LBW is associated with reproductive performance, ovulation rate, carcass production and attributes, body condition score, fibre attributes and skin quality. The LBW at weaning is regarded as a critical benchmark for animal welfare, production and profitability (McGregor Citation2012). In addition, the lack of growth and low survivability in recently weaned kids are related directly to LBW at weaning, and the risks increase rapidly as LBW declines (McGregor Citation2012). In fact, the first days of life have been recognized as the most vulnerable period in the animals’ life because of the high mortality (Piccione et al. Citation2010). Neonatal mortality is a relevant cause of economic losses in livestock production (Dwyer Citation2008). Thus, knowledge on the growth of LBW is critical for animal health interventions.

Since the socioeconomic role of goats, in communities living in the semiarid regions (i.e. Jordan), will be maintained over the forthcoming decades (Salem Citation2010), efforts should be intensified to improve productive and reproductive performances of goats. Reduction in growth rate in goats compromises animal welfare (Caulfield et al. Citation2014; Okoruwa Citation2014). Thus, investigating growth rate and survivability of goat kids are important in predicting the reproductive performance. Furthermore, the traditional way of goat management is challenged by low survivability of kids (Hagos et al. Citation2016). In view of the above considerations, the present study was designed for first estimating the pattern of growth and survivability in three goat breeds (Baladi, Shami and Hybrid) from Jordan. In details, the present study aimed at evaluating the effect of goat breed upon the growth traits and survivability of goat kids, emphasizing the necessity to objectively assess the welfare of Jordanian goats with the hope of providing baseline information for improving their growth traits, and assessing goat breed for better genetic selection in Jordan.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Location, animals, housing and feeding

The study was conducted during the period from November, 24th 2016 until February, 9th 2017, and it was set up for a period of twelve successive weeks. Geographically the study area is located in the Southern part of Jordan between Latitude of 31°27″ and Longitude of 35°74″ with an altitude of 960 m above sea level. Newly born goat kids, as a single birth type (Appendix; Table A1), representing three different breeds [Baladi (Black Bedouin), Shami (Damascus) and Hybrid (F1 of both Baladi and Shami)] were used in this study. The animals were reared under an intensive farming system in the Animal Farm of Agricultural Research Station at Mutah University in Karak city, Jordan. Their mothers (does) were born in the same year (Septemeber–November of the year 2014) and reared under similar conditions in the station (Appendix 1, Table A1). All procedures performed in the present trial involving animals were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Animal Care and Use Committee at Mutah University, Jordan (No. AGR-82006). The current study was set up using apparently healthy goat kids of the fore-mentioned goat breeds, and they were kept under close clinical observations throughout the trial period by veterinarians. Routine health care practices (i.e. vaccination/medication, ecto-parasite control and de-worming), and routine management (i.e. cleaning of the pen, washing the feeders and drinkers of the animals, and cleaning their hay racks and faeces) were regularly carried out. The goat kids were kept in a shaded housing facility, such that the animals were protected from direct solar radiation during the whole day. The facility had an adequate space per animal and a closed ceiling, two wall-sides fully closed, the backside wall had a window and the front side opened.

All animals had free access to drinking water ad libitum, and were fed a similar standard diet (15% CP; 2.4 Mcal/kg NE) ad libitum. Ingredients’ composition of the standard ration consisted of 45.3% barley grain, 15.7% soybean meal, 13.6% cracked corn, 13.6% wheat bran, 10.0% wheat straw, 0.9% salt, 0.5% limestone, 0.2% diacalcium phosphate, 0.2% mineral and vitamin premix.

2.2. Experimental design and measurements

One-day old kids were separately allocated to three treatment groups; Baladi (n = 56; 28 males and 28 females), Shami (n = 47; 27 males and 20 females), and Hybrid (n = 25; 12 males and 13 females) in a completely randomized design. All animals from the three breeds were ear-tagged at day one old.

The LBW (kg/kid) of the newborn kids in each treatment group was weighed following the complete drying of the body within the 6 h maximum after birth, and then at weekly intervals by using a digital balance for 12 consecutive weeks of the trial period. The mean BWG (kg/kid) was calculated at the end of each week. The BWG was expressed as BWG = (BWf – BWi), where BWf is the body weight at the end of the week, and BWi is the body weight at the beginning of the week. The survivability (%) was calculated at the end of the trial by dividing the number of live kids over the total number of kids at the beginning of the trial, and the product is multiplied by 100 to obtain the survivability percentage. Meteorological parameters including the ambient temperature (Ta) and relative humidity (RH) were daily taken three times using a digital thermo-hygrometer from Rabeh Metrological Station at the study site at 9.00 am (morning), 1.00 pm (afternoon) and 5.00 pm (evening) throughout the 12 consecutive weeks of the trial. The Ta and RH recorded during the study period at the trial site ranged between 7.3°C and 15.3°C (mean: 9.60°C) as well as 42.4% and 72.8% (mean: 59.0%), respectively.

2.3. Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was processed by the Proc General Linear Model (GLM) (SPSS 19.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) (SPSS Citation1997). Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was applied to evaluate the influence of the sex of kids among the three goat breeds on the studied traits. If ANOVA showed an acceptable level of significance (P < 0.05), Bonferroni’s test was applied for post hoc comparison (Zar Citation1999). Independent samples t-test was used to compare two means only; i.e. LBW and BWG of goat males and females. Data obtained were presented as means ± standard deviation (SD). Finally, sex and breed were fitted as fixed independent variables, while LBW, BWG, and Survivability% were fitted as dependent variables. The model to analyse the measurement variables was Yijk = μ + Bi + Sj + Eijk, where Yijk, the observed k measurement (LBW, BWG, Survivability %) in the ith breed, jth sex; μ, overall mean εijk, Bi is fixed effect of ith breed (i = 1, 2 and 3; Baladi, Shami and Hybrid); A j is the fixed effect of jth sex (j = 1 and 2; Male and female); Eijk, random residual error.

3. Results

3.1. Live body weight

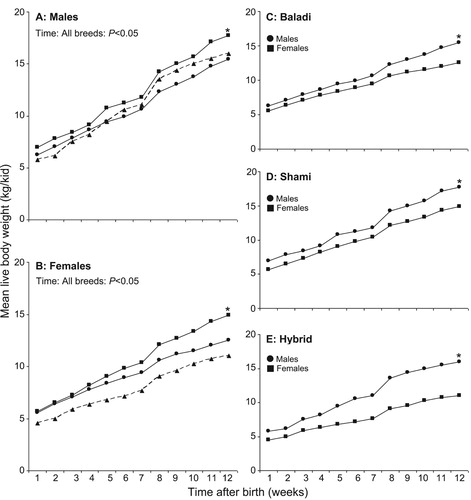

Time course changes in mean LBW of males and females of three goat breeds are shown in . The results indicated that mean weekly LBW show a significant (P < 0.05) increase for both males and females of the three goat breeds tested ((A,B)). The birth LBW was 6.26 ± 1.57, 6.96 ± 1.80 and 5.78 ± 1.23 kg/kid (males) as well as 5.54 ± 1.08, 5.69 ± 1.94 and 4.54 ± 0.73 kg/kid (females) in Baladi, Shami and Hybrid, respectively. The mean LBW of males and females’ kids raised from 1 to 12 weeks of age and reached a final LBW of 15.45 ± 3.65 and 12.52 ± 3.41 kg/kid (Baladi), 17.71 ± 5.23 and 14.92 ± 5.10 kg/kid (Shami), and 15.96 ± 4.99 and 11.01 ± 2.64 kg/kid (Hybrid), respectively.

Figure 1. Time course changes in mean live body weight (kg/kid) of males and females of three goat breeds. Baladi (n = 56; 28 males and 28 females, ●, solid line), Shami (n = 47; 27 males and 20 females, ▪, solid line), and Hybrid (n = 25; 12 males and 13 females, ▴, dashed line). *: Indicates significant differences among the three breeds at P < 0.05 (one-factor ANOVA) or significant differences between males and females within the same goat breed at P < 0.05 (t-test).

Goat breed had a significant effect on males and females’ LBW. The final LBW (12-week-age) of both sexes of Shami goats was significantly (P < 0.05) higher than Baladi and Hybrid breeds ((A,B)). In addition, mean final LBW of male kids was also significantly (P < 0.05) higher than their female counterparts in all goat breeds tested, where it was 15.45 ± 3.65 vs. 12.52 ± 3.41 kg/kid (Baladi), 17.71 ± 5.23 vs. 14.92 ± 5.10 kg/kid (Shami), and 15.96 ± 4.99 vs. 11.01 ± 2.64 kg/kid (Hybrid), respectively ((C–E)).

3.2. Body weight gain

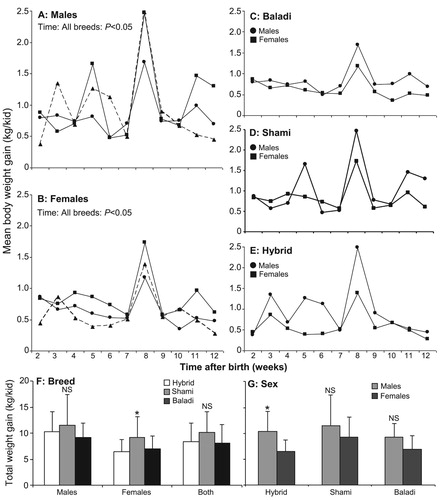

Time course changes in mean BWG (Appendix 1, Table A2) of males and females of the three goat breeds are presented in . The results indicated that mean weekly BWG of both males and females the three goat breeds fluctuated irregularly and significantly (P < 0.05) throughout the trial period ((A,B)). During the whole the trial duration, the highest weekly BWG was significantly recorded in the 8th week after kid birth for males and females with 1.685 ± 0.73 and 1.177 ± 0.68 for Baladi ((C)), 2.474 ± 1.23 and 1.734 ± 1.28 kg/kid for Shami ((D)), and 2.483 ± 1.25 and 1.392 ± 0.87 kg/kid for Hybrid ((E)), respectively. Furthermore, total BWG of Shami goats was slightly higher than Baladi and Hybrid breeds ((F)). In addition, male goats had slightly higher total BWG than their female counterparts in all breeds; Baladi (9.23 ± 2.72 vs. 6.98 ± 2.51 kg/kid), Shami (11.50 ± 5.95 vs. 9.24 ± 3.96 kg/kid) and Hybrid (10.30 ± 3.87 vs. 6.48 ± 2.29 kg/kid), respectively ((G)).

Figure 2. Time course changes in mean body weight gain (kg/kid) of three goat breeds. Baladi (n = 56; 28 males and 28 females, ●, solid line), Shami (n = 47; 27 males and 20 females, ▪, solid line), and Hybrid (n = 25; 12 males and 13 females, ▴, dashed line). *: Indicates significant differences among the three breeds at P < 0.05 (one-factor ANOVA) or significant differences between males and females within the same goat breed at P < 0.05 (t-test). NS: Not significant.

3.3. Survivability

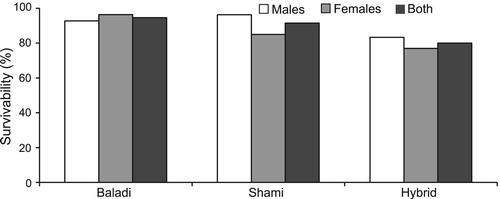

Survivability throughout the whole trial duration (12 weeks) of the three goat breeds are shown in . The total survivability (both sexes) was slightly higher in Baladi (94.64%) than in Shami (91.49%) and Hybrid (80.00%). The survivability of males and females’ kids was 92.80% and 96.40% (Baladi), 96.30% and 85.00% (Shami), and 83.30% and 76.90% (Hybrid), respectively.

4. Discussion

Adaptability traits, i.e. reproductive performances and survivability, are recognized as the most important traits for goat holders (Tabbaa and Al-Atiyat Citation2009). Goat LBW is regarded as a critical benchmark for animal welfare, production and profitability. However, the current results indicated that mean weekly LBW showed a significant increase in both sexes of the three goat breeds tested, which is in agreement with the findings of Zahraddeen et al. (Citation2008), who stated that LBW of goat kid showed a significant increase at various ages (birth, 30, 60, 90 and 120 days of life). The present results indicated differences in birth weight values among the three different breeds (Baladi, Shami and Hybrid). In this regard, it is to be mentioned that the birth weight of goat kids is influenced by breed, sex of kid, birth type, age of the dam, feeding conditions, season of birth, production system (Otuma and Osake Citation2008; Meenakshi et al. Citation2012; Rout et al. Citation2018), and genetic makeup – breed – and environmental reasons (Meza-Herrera et al. Citation2012).

The current results demonstrated that goat breed had a significant effect on LBW. The LBW (12-week-age) of both sexes of Shami goats was significantly higher than Baladi and Hybrid breeds. In this regard, many other studies on other goat breeds indicated differences in the LBW among different goat breeds, i.e. the LBW is superior in Red Sokoto over West African Dwarf breed kids (Zahraddeen et al. Citation2008), Saanen X Hair over Saanen breed kids (Akdag et al. Citation2011), and Begait over Abergelle breed kids (Hagos et al. Citation2016). However, higher values for birth weight and LBW (12-week-age) of both sexes of Shami goats throughout the trial period indicated a higher growth rate for Shami kids.

The effect of gender on LBW in our study was significant. In particular, male kids of all goat breeds (Baladi, Shami and Hybrid) had consistent weight advantage over their female counterparts at various ages up to 12 weeks. The results were in consonance with the findings of many previous studies on other goat breeds indicating that male kids were superior to their female counterparts at all stages of growth (Faruque et al. Citation2016; Rout et al. Citation2018). It has been attributed that the growth superiority of male kids to higher weight (birth and at various ages up to 12 weeks) is the presence of androgens, which play a role in growth, and it may also be due to the fact that males are more active than females, and may consume more milk and feed (Nkungu et al. Citation1995). The difference between male and female kids may also be reflected in the attainment of puberty, since it has been observed that the onset of puberty is more closely related to LBW than age.

The present results indicated that mean weekly BWG of both males and females of the three goat breeds fluctuated irregularly and significantly throughout the trial period. Furthermore, total BWG of Shami goat was significantly higher than Baladi and Hybrid breeds. In this regard, Akdag et al. (Citation2011) reported that Saanen X Hair crossbred kids had achieved significantly higher BWG than Saanen kids. The current results indicated that there was consistently higher BWG advantage in males than females’ kids in all breeds tested. In accordance with our results, Zahraddeen et al. (Citation2008), Andries (Citation2013), and Faruque et al. (Citation2016) stated that male BWG was higher than female BWG, proving that there was influence of gender on BWG.

The total survivability, in the current study, was higher in Baladi (94.64%) than in Shami (91.49%) and Hybrid (80.00%). In agreement with our results, Al-Atiyat et al. (Citation2010) reported a survivability of 93% for Baladi goats. In this regard, many authors stated a closer survivability to the current study, i.e. 91.7% and 96.3% in Saanen and Saanen X Hair kids, respectively (Akdag et al. Citation2011), 83.3% and 91.9% in Begait and Abergelle kids, respectively (Hagos et al. Citation2016), 87.8% in Arsi Bali kids (Ketema Citation2007), and 93.86% in Solid Black kids (Choudhury et al. Citation2012). The reason for the low survivability in Hybrid goats comparing with Baladi and Shami might be due to the low heritability of kid survival as reported by Rout et al. (Citation2018) and similar estimates have been reported in lamb (Matika et al. Citation2003). Also, it is reported that kids survived best due to probably attributed to fewer incidences of pests and diseases in the dry than in wet season (Taiwo et al. Citation2005). The newborn becomes engaged in a series of profound metabolic and morphological changes that are known as the adaptive period (Piccione et al. Citation2007). In fact, the adaptive period is recognized as the most vulnerable period in the life of animals because of the high mortality, which is more relevant during the first days of life (Piccione et al. Citation2010). The major cause for neonatal death is the neonatal diarrhoea, which is a multifactorial diarrhoea affects neonates at an age of less than 2 months, in which bacteria, protozoa and viral agents are involved in diarrhoea.

5. Conclusions

The present findings indicated that LGW, BWG and survivability of goat kids were considerably affected by their breeds and gender. Shami breed proved higher growth performance compared to Baladi and Hybrid breeds. Farming management and production strategies should take into consideration both the findings of the current study, in which Shami breed has supported comparatively better growth responses from one side, and from the other side, Shami goats have less tolerant to harsh climate of Jordan. However, there is a need to carry out further investigations on Shami goats’ adaptability, behaviour and farm profitability which has implications for the economic viability of utilizing this breed under Jordan harsh climate. It is hoped that the current findings could be used in the breeding soundness assessment to select the correct goat breed and might be contributed to the ongoing efforts to improve goat production in Jordan.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Akdag F, Pir H, Teke B. 2011. Comparison of growth traits in Saanen and Saanen X Hair Crossbred (F1) kids. Hayvansal Üretim. 52:33–38.

- Al-Atiyat RM. 2014. Sustainable breeding program of Black Bedouin goat for conserving genetic diversity: Simulated scenarios for in Situ conservation. Jor J Agric Sci. 10:83–95.

- Al-Atiyat RM. 2017. Genetic diversity analyses of tropical goats from some countries of Middle East. Genet Mol Res. 16:gmr16039701. doi:10.4238/gmr 16039701 doi: 10.4238/gmr16039701

- Al-Atiyat RM, Alobre M, Aljumaah RS, Alshaikh MA. 2015. Microsatellite based genetic diversity and population structure of three Saudi goat breeds. Small Rumin Res. 130:90–94. doi: 10.1016/j.smallrumres.2015.07.027

- Al-Atiyat R, Rewe T, Herold P, Valle Zarate A. 2010. A simulation study to compare different breeding scenarios for Black Bedouin goat in Jordan. Egy J Sheep Goat Sci. 5:83–92.

- Al-Atiyat RM, Salameh NM, Tabbaa MJ. 2012. Phylogeny and evolutionary analysis of goat breeds in Jordan based on DNA sequencing. Pak J Biol Sci. 15:850–853. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2012.850.853

- Al-Atiyat RM, Tamimi H, Salameh N, Tabbaa MJ. 2015. Genetic diversity and differentiation of Jordan goat breeds using microsatellite markers. J Anim Plant Sci. 25:1532–1539.

- Al-Dawood A. 2015. Adoption of agricultural innovations: investigating current status and barriers to adoption of heat stress management in small ruminants in Jordan. Am-Eur J Agric Environ Sci. 15:388–398.

- Al-Dawood A. 2017a. Acute phase proteins as indicators of stress in Baladi goats from Jordan. Acta Agric Scand A Anim. 67:58–65.

- Al-Dawood A. 2017b. Effect of heat stress on adipokines and some blood metabolites in goats from Jordan. Anim Sci J. 88:356–363. doi: 10.1111/asj.12636

- Al-Dawood A. 2017c. Towards heat stress management in small ruminants: A review. Ann Anim Sci. 17:59–88. doi: 10.1515/aoas-2016-0068

- Al-Tamimi HJ. 2007. Thermoregulatory response of goat kids subjected to heat stress. Small Rumin Res. 71:280–285. doi: 10.1016/j.smallrumres.2006.04.013

- Al-Tamimi HJ, Al-Atiyat RM, Al-Majali AD. 2012. Differences in body core and shell temperature patterns between Black Bedouin, Damascus and Crossbred goat kids in late winter. Proceedings of the 11th International Conference of goats; Sep 23–27; Gran Canaria, Spain, p. 106.

- Alade NK, Dilala MA, Abdulyekeen AO. 2010. Phenotypic and genetic parameter estimates of litter size and body weights in goats. Inter J Sci Nat. 1:262–266.

- Andries KM. 2013. Growth and performance of meat goat kids from two seasons of birth in Kentucky. Sheep Goat Res J. 28:16–20.

- Caulfield MP, Cambridge H, Foster SF, McGreevy PD. 2014. Heat stress: a major contributor to poor animal welfare associated with long-haul live export voyages. Vet J. 199:223–228. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2013.09.018

- Choudhury MP, Sarker SC, Islam F, Ali A, Bhuiyan AKFH, Ibrahim MNM, Okeyo AM. 2012. Morphometry and performance of Black Bengal goats at the rural community level in Bangladesh. Bangl J Anim Sci. 41:83–89. doi: 10.3329/bjas.v41i2.14122

- Dwyer CM. 2008. The welfare of the neonatal lamb. Small Rumin Res. 76:31–41. doi: 10.1016/j.smallrumres.2007.12.011

- Ekambaram B, Gupta RB, Gnana PM, Sudhaker K, Reddy VR. 2010. A study on the performance of Mahabubnagar goats. Ind J Anim Res. 44:48–51.

- Faruque MO, Choudhury MP, Ritchil CH, Tabassum F, Hashem MA, Bhuiyan AKFH. 2016. Assessment or performance and livelihood generated through community based goat production in Bangladesh. SAARC J Agric. 14:12–19. doi: 10.3329/sja.v14i2.31241

- Guney O, Torun O, Ozuyanık O, Darcan N. 2006. Milk production, reproductive and growth performances of Shami goats under northern Cyprus conditions. Small Rumin Res. 65:176–179. doi: 10.1016/j.smallrumres.2005.07.026

- Hagos H, Brihene M, Zeneb M, Gebru G, Tekle D, Redae M, Brhane G. 2016. Comparative growth and production performance evaluation of indigenous Begait and Abergelle goat breed under farmer’s management practice in Tigray, northern Ethiopia. J Biol Agric Healthcare. 6:41–46.

- Jordan Statistical Yearbook. 2016. Department of Statistics, Amman Agricultural Surveys, Jordan, No. 67, p. 282.

- Karagiannidis A, Varsakeli S, Karatzas G. 2000. Characteristics and seasonal variations in the semen of Alpine, Saanen and Damascus goat bucks born and raised in Greece. Theriogenol. 53:1285–1293. doi: 10.1016/S0093-691X(00)00272-7

- Ketema TK. 2007. Production and marketing of sheep and goats in Alaba. M.Sc. Thesis, Hawassa Univ., Hawassa, Ethiopia, p. 159.

- Matika O, van Wyka JB, Erasmusa GJ, Bakerb RL. 2003. Genetic parameter estimates in Sabi sheep. Livest Prod Sci. 79:17–28. doi: 10.1016/S0301-6226(02)00129-X

- McGregor BA. 2012. Importance of body weight in goat production, husbandry and welfare. Book of abstracts. Proc. 11th Inter. Conf. goats, Gran Canaria, Spain, 23-27 Sept., p 150.

- Meenakshi S, Muthuramalingam T, Rajkumar JSI, Nishanth B, Sivakumar T. 2012. Growth performance of Tellicherry goats in an organized farm. Inter J Dairy Sci Res. 1:9–11.

- Meza-Herrera CA, Calderón-Leyva G, Soto-Sanchez MJ, Abad-Zavaleta J, Serradilla JM, García-Martinez A, Rodriguez-Martinez R, Veliz FG, Macias-Cruz U, Salinas-Gonzalez H. 2012. The expression of birth weight is modulated by the breeding season in a goat model. Ann Anim Sci. 12:237–245. doi: 10.2478/v10220-012-0020-8

- Nkungu DR, Kifaro GC, Mtenga LA. 1995. Performance of dairy goats in Mgeta, Morogoro. Tanzania Srnet Newslett. 28:3–8.

- Okoruwa MI. 2014. Effect of heat stress on thermoregulatory, live body weight and physiological responses of dwarf goats in southern Nigeria. Europ. Sci J. 10:255–264.

- Otuma MO, Osake II. 2008. Estimation of genetic parameters of growth traits in Nigeris Sahelian goats. Res J Anim Sci. 2:83–86.

- Piccione G, Borruso M, Giannetto C, Morgante M, Giudice E. 2007. Assessment of oxidative stress in dry and lactating cows. Acta Agric Scand A Anim Sci. 57:101–104.

- Piccione G, Casella S, Pennisi P, Giannetto C, Costa A, Caola G. 2010. Monitoring of physiological and blood parameters during perinatal and neonatal period in calves. Arq Bras Med Vet Zootec. 62:1–12. doi: 10.1590/S0102-09352010000100001

- Rout PK, Matika O, Kaushik R, Dige MS, Dass G, Singh MK, Bhusan S. 2018. Genetic analysis of growth parameters and survival potential of Jamunapari goats in semiarid tropics. Small Rumin Res. 165:124–130. doi: 10.1016/j.smallrumres.2018.04.002

- Roy R, Dass GG, Tiwari HA. 2011. Improvement and sire evaluation of Jamunapari goats for milk production. Ann. Rep. (2010–2011) of Central Inst. Res. Goats, Makhdoom, Mathura, UP, India, p. 19–22.

- Salem HB. 2010. Nutritional management to improve sheep and goat performances in semiarid regions. R Bras Zootec. 39:337–347. doi: 10.1590/S1516-35982010001300037

- [SPSS] Statistical Product and Service Solutions INC. 1997. SIGMASTAT 2.03: SigmaStat Statistica Software User’s Manual, Chicago, United States.

- Tabbaa MJ, Al-Atiyat RM. 2009. Breeding objectives, selection criteria and factors influencing them for goat breeding in Jordan. Small Rumin Res. 84:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.smallrumres.2009.03.007

- Taiwo BBA, Buvanendran V, Adu IF. 2005. Effects of body condition on the reproductive performance of Red Sokoto goats. Nig J Anim Prod. 3:1–6.

- Zahraddeen D, Butswat ISR, Mbap ST. 2008. Evaluation of some factors influencing growth performance of local goats in Nigeria. Afr J Food Agric Nutr Dev. 8:464–479.

- Zaitoun IS, Tabbaa MJ, Bdour S. 2005. Differentiation of native goat breeds of Jordan on the basis of morphostructural characteristics. Small Rumin Res. 56:173–182. doi: 10.1016/j.smallrumres.2004.06.011

- Zar JH. 1999. Bio-statistical analysis. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. p. 663.