?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Climate variability has had major health consequences for both humans and animals. A cross-sectional study was conducted in six administrative regions of The Gambia to respond to three questions: (i) what are the livestock farmers’ perceived occurrences and causes of climate variability? (ii) what are the perceived impacts of climate variability on livestock farming? (iii) what factors influence livestock farmers’ knowledge and perception of the causes and impact of climate variability? A total of 440 livestock farmers comprising 351 (80%) males and 89 (20%) females were interviewed and 6 Focus Group Discussions were held. The data were analysed using descriptive statistics, Pearson's chi-squares test and Binary logistic regression. Livestock farmers are aware of the causes and effects of climate variability on their productivity. Climate variability caused cattle farmers to have production issues, and as a result, this investigation also reveals the impact on their productivity. Finally, the result also shows that the explanatory variables (age and region of residence) were the main factors significantly influencing livestock farmers’ perception of climate variability. There is need for the government of The Gambia to address the challenges faced by livestock farmers due to climate variability.

1. Introduction

The notion of climate variability is perhaps the most discussed phenomenon of our time. There is consensus in the scientific world that land and sea temperatures are warming due to the rising effects of Greenhouse Gases and this warming is expected to continue for at least, the next two decades regardless of human interventions (Olaniyan and Orunmuyi Citation2017; Badjie et al. Citation2019). Global average temperature has increased by 0.78°C during the past century and is as well forecasted to rise by an additional 1.1–6.48°C during the twenty-first century Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) et al. Citation2018).

Countries in West Africa have seen prominent changes in temperature since the 1940s, and in the period 1970–2010, temperatures have increased drastically (World Bank Group Citation2021). Climate change and variability have had major health consequences for both humans and animals (Lacetera Citation2019; Leal Filho et al. Citation2022). These range from direct effects from temperature upsurge posed by global warming, heat waves and floods to indirect effects such as fluctuations in ecosystem services, food productivity and species distributions (Montag et al. Citation2017; Marselle et al. Citation2019; Kargbo and Kuye Citation2020; Mavhura et al. Citation2021).

West Africa’s heavy reliance on rainfed agriculture makes it to be one of the most vulnerable continents to climate variability (Bagagnan et al. Citation2019) and The Gambia is not an exception to this menace (Olaniyan Citation2017). However, there is a relationship between livestock production and variations in climatic elements (Challinor et al. Citation2014; Weindl et al. Citation2015; Olaniyan Citation2017). Depending on their degree, climate variability has negative effects on livestock species and farmers whose livelihoods are sensitive to them (Olaniyan and Orunmuyi Citation2017; Olaniyan Citation2017).

Furthermore, The Gambia’s agricultural sector’s performance with regard to livestock production has been fluctuating in relation to climate variability hazards, with effects such as seasonal feed shortage and high disease prevalence (Olaniyan Citation2017). Livestock farmers’ awareness of the causes of climate variability and its impact plays a key role in the adoption of innovative technology (Megersa et al. Citation2014; Meijer et al. Citation2015; Kimaro et al. Citation2018). Perceptions of the evolution of climate variables differ across different climatic zones in Africa (Ochieng et al. Citation2016). A study conducted in southwestern Burkina Faso showed that farmers’ awareness of the ongoing environment changes depends on their experiences of historical weather events (Sanogo et al. Citation2017). In Ethiopia, Tanzania and Senegal, for instance, most farmers perceived climate variations as the occurrence of drought events (Megersa et al. Citation2014; Kimaro et al. Citation2018; Bagagnan et al. Citation2019). In the savanna zone of Senegal, farmers associated the effects of climate variability with the manifestation of violent winds and sporadic storms (Eguavoen et al. Citation2015).

In The Gambia, there is very scanty information about livestock farmers’ perceived causes and impacts of climate variability in all regions of the country especially in rural communities. Most studies that have been conducted including Olaniyan (Citation2017) and Bagagnan et al. (Citation2019) did not look at livestock farmers’ perception of climate variability and its impact on livestock production in all the regions of the country. Moreover, all these studies focused only on one specific administrative region of The Gambia. Livestock farmers’ perception of climate variability (its existence, occurrence and impact) which is also a part of their indigenous knowledge, is crucial for making and implementing decisions and policies related to the mitigation of the threats, and management of livestock farming. Furthermore, livestock farmers’ perceptions represent the baseline information for motivating and directing research projects regarding this issue. The present study explicitly responds to the questions such as: (1) what are the livestock farmers’ perceived causes of climate variability? (2) what are the perceived impacts of climate variability on livestock farming? (3) what factors are influencing livestock farmers’ knowledge and perception of the causes and impact of climate variability. Therefore, this study seeks to investigate the existing knowledge gap on livestock farmers’ perceptions towards climate variability and how it affects livestock farming in all the administrative regions of The Gambia.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study location

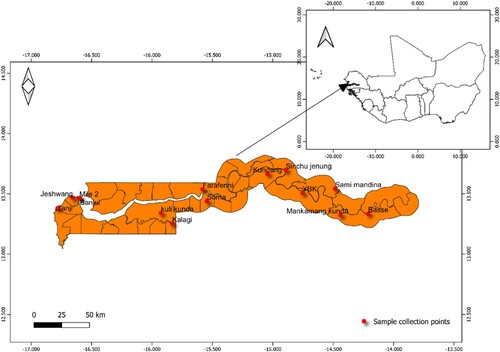

The Gambia is located in the tropical sub-humid ecoclimatic zone, with annual rainfall ranging from 800 to 1200 mm annually (Jaiteh and Sarr, Citation2011). There are two seasons in a year; that is a rainy season (June to October) and a dry season (November to May) which means 6–7 months without rain, during the dry season, the climate is dominated by dry, dusty winds that originated from the Sahara Desert (Jaiteh and Sarr Citation2011). A total of 12 districts were chosen at random by balloting all the districts found in each of the regions of The Gambia except Banjul City Council and Kanifing Municipal Council which were excluded from this study. This was as a result of the lack of livestock farmer or rearer in these urban areas in the data obtained from The Gambia Bureau of Statistics (GBOs) survey 2017. These districts were chosen randomly because this work intended to target livestock farmers in all the administrative regions of The Gambia. These districts included: Kombo South and Foni Bintang Karanai in West Coast Region (WCR), Kiang West and Jarra West located in Lower River Region (LRR), Lower Niumi and Upper Badibu located in North Bank Region (NBR), Sami and Niani located in Central River Region-North (CRR-N), Niamina East and Upper Fulladu located in Central River Region-South (CRR-S) and Fulladu East and Jimara located in Upper River Region (URR). shows the map of The Gambia indicating the various sampling sites.

2.2. Data collection

A cross-sectional study was conducted from October to December 2020. Respondents were randomly chosen from WCR, LRR, NBR, CRR-S, CRR-N and URR of The Gambia. The Gambia Bureau of Statistics survey (GBOS) (Citation2017) showed the total population of individuals with livestock in The Gambia as 724,952. Using Yamane Citation1967 formula, where x is the sample size, N is the population size and e is the level of precision (0.05).

A sample size of 400 was obtained and this was further multiplied by 10% for sampling error to obtain 440 respondents. The final sample size of 440 was then divided among the regions based on the ratio obtained from GBOS: West Coast Region 3.4/102.4(15), Lower River Region 17.5/102.4(75), North Bank Region 17.8/102.4(76), Central River Region-North 25.9/102.4(111), Central River Region-South 13/102.4(56) and Upper River Region 24.8/102.4(107). Two districts and one village per district were randomly selected for each region in The Gambia (). A list of all the livestock farmers was obtained from the veterinary officers serving in those districts. The names of the 440 livestock farmers (351 males and 89 females) evaluated were randomly selected from the lists provided by the livestock officer serving in each region. All inhabitants greater than 18 years, residing in the specified region for more than 36 months, and able to communicate were considered eligible for the study.

2.3. Respondents’ interviews

One-to-one interview was conducted in October 2020 for 440 livestock farmers’ using a structured pre-tested questionnaire residing in each of the 6 regions of The Gambia and this session lasted for about 25 minutes. These questionnaires were made up of both open- and closed-ended questions. The interview questions consisted of three sections namely: (1) demographic; (2) perception of knowledge of the occurrence and cause of changes variability (rainfall patterns and temperature fluctuations) and their impact on livestock production. Seven questions were in the demographic section while eight questions were in the perception section (Appendix 1). This was interpreted orally in the local language to the farmers by using indigenous languages (Mandinka, Fula and Wolof).

2.4. Focus group discussion

Six Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) with at least two livestock farmers from each village were held in each of the six regions. These participants were recruited from the one-to-one interview session. The age of the livestock farmers and the number of years they have been involved in livestock rearing were the main criteria used in recruiting them for the FGDs (Agwu et al. Citation2018). One FGD was held per region using semi-structured interview questions and each lasted for about 35–45 min. The interview questions used guide comprised four main questions and they were centred on (1) perception of changes in rainfall patterns in the last three decades; (2) impact of changes in rainfall on livestock production; (3) perception of changes in temperatures in the last three decades and (4) impact of changes in temperatures on livestock production (see Appendix 2).

2.5. Statistical analysis

Microsoft Excel Office version 2019 software was used to manage the raw data and STATA 11 statistical analysis tool was used to analyse and interpret the data. The data obtained was presented using descriptive statistics (frequencies and percentages). The relationships between respondents’ demographic variables (e.g. age, gender, educational status, occupation and region of residence) with knowledge were examined using Pearson's chi-square and Binary Logistic Regression. In the Binary Logistic Regression, we considered demographic variables (e.g. gender, age, education level, main occupation, region and number of animals owned) of respondents as the predictors or independent variables and perception variables (e.g. knowledge of change in rainfall pattern and temperature) as dependent variables. To describe Binomial logistic regression model, let x denote a set of conditioning variable, in this case, y represents the category chosen by the farmer. Therefore y represents a knowledge of temperature and rainfall. X is the vector of the predictor variable.

Y is considered as a dependent variable taking values ‘1’ and ‘0’ and X can be considered as a categorical predictor variable. The Binary logistic regression formula for categorical dependent variable is described as follows:

P: probability of Y occurring

e: natural logarithm base

bo: interception at y-axis

b1: line gradient

bn: regression coefficient of Xn

X1: predictor variable

P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Content analysis was used for the qualitative data.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-demographic characteristics of the livestock farmers

A total of 440 livestock farmers responded to this study. Among them, 351 (80%) were males, while 89 (20%) were females. About one-third of the livestock farmers 132 (30%) were between 40 and 49 years old. Regarding educational level, the highest number 146 (33.2%) were illiterate. More than half 222 (50.5%) were herdsmen. Regarding residential area, 111 (25.3%) of the livestock farmers live in CRR-N () and most of them 195 (44%) owned cattle.

Table 1. Demography of livestock farmers.

3.2. Perception of livestock farmers on observed and causes of climatic variability

The perception of livestock farmers towards observed changes in temperature shows that 418(95%) reported observing changes in rainfall while 378 (86%) reported that there has been an increase in temperature in their communities over the past 30 years (). In contrast, most of the livestock farmers 189(43%) and 106(24%) respectively reported that the change in rainfall and temperature is a result of natural causes while 185(42%) and 216(49%) respectively also reported that rainfall and temperature increase is caused by humans in .

Table 2. Livestock farmers’ perception of changes in climate variabilities.

Table 3. Livestock farmers’ perception of causes of the changes in climate variabilities.

3.3. Perceived impacts of climate variability on livestock farming in the study districts

Respondents in this survey were asked how well they understood the effects of temperature and rainfall on vegetation in The Gambia (). Changes in rainfall and temperature have had a negative impact on livestock herds. According to farmers in FGDs, the effects of lesser rainfall especially from 2016 to 2020 had a serious impact on their animals and this included; decreased fertility, less pasture and animals having to roam for long distance to have access to pasture and water among others (). Livestock farmers also reported in FGD that they were experiencing more cases of intrusion of salt water into the River Gambia and bushfires are becoming more common nowadays than they were previously.

Table 4. Perceived impacts of changes in climate variability on cattle rearing.

Table 5. Impact of climate related risks observed by livestock farmers during the FGD’s.

3.4. Factors associated with knowledge of the respondents towards climate variabilities and its impact on livestock production in The Gambia using Pearson Chi-square test

shows Pearson chi-square results for the perception of livestock farmers on the occurrence of climate change perceived variations in rainfall patterns and temperature fluctuation in The Gambia. Region, age, ethnic group, occupation and educational level all were significantly associated with livestock farmers’ perception of change in rainfall patterns, while region, age ethnic group, occupation and educational level were also highly significant with their perception of change in temperature. However, shows the Pearson chi-square results of livestock farmers’ perception of the causes and impact of climate change on cattle rearing in The Gambia. Age and region were both repeatedly seen to be significant in both variables.

Table 6. Pearson chi-square result for livestock farmers’ perception of the occurrence of changes in climate variabilities.

Table 7. Pearson chi-square result for livestock farmers’ perception on the causes and impact of changes in climate variabilities on cattle rearing.

3.5. Binomial logistic regression result (general livestock farmers’ perception of climate change and variability)

: shows the binomial logistic result of how livestock farmers’ perceived variation in temperatures and rainfall patterns in The Gambia. This result also reveals that middle-aged farmers that is 40–49 years old had (CL 0.871–0.023 and p = 0.035), as did livestock farmers in the NBR (CL 76.69–2.05 and p = 0.006), CRR-S (CL 38.12–1.12 and p = 0.038) and CRR-N (63.53–363 and p = 0.001) were the main factors significantly influencing livestock farmers’ perception on rainfall. As for temperature, livestock owners residing in WCR (CL 46.57–5.52 and p < 0.001), NBR (CL 76.69–2.05 and p = 0.006), CRR S (CL 6.49–1.12 and p < 0.038), CRR-N (CL 63.53–3.63 and p < 0.001) and Herdsmen (CL 148.4–2.79 and p < 0.003) and Crop farmers (CL 237.2–2.79 and p < 0.004) were highly associated with knowledge on changes in temperatures.

Table 8. Binomial logistic result of how livestock farmers perceived variation in temperatures and rainfall patterns in The Gambia.

4. Discussion

This study sought to investigate the existing knowledge gap on livestock farmers’ perceptions towards climate variability and how it affects livestock farming in all the administrative regions of The Gambia. The findings of this study showed that changes in climatic variability have had a significant impact on livestock farming in The Gambia. According to metrological evidence from Cham et al. (Citation2018), precipitation has decreased, the duration of the rainy season has decreased, minimum temperatures have decreased, maximum temperatures have increased and the frequency of severe weather events such as drought and dust storms has increased in The Gambia over the past 60 years. This study shows that livestock farmers in The Gambia are well aware of changes in climate variability (). Farmers’ views of climate change and variability are consistent with weather data evidence and observations from other studies in Burkina (Sanfo et al. Citation2015; Sanou et al. Citation2018), Ghana (Fagariba et al. Citation2018; Dakurah Citation2020), Ethiopia (Getachew et al. Citation2014), Benin (Idrissou et al. Citation2020), Zimbabwe (Mavhura et al. Citation2021) and even in The Gambia by Bagagnan et al. (Citation2019) and Bah et al. (Citation2019) stated that farmers and fishermen in CRR of The Gambia observed a rise in the average annual temperature, severe weather events such as frequency in drought and flood and a decrease in the annual average precipitation. However, in this study, farmers’ perceptions of rainfall and temperature in The Gambia were questioned, and some linked them to God’s punishment due to human disobedience, as shown in . According to some livestock owners in one of the FGDs, ‘Allah (God) is angry because of our bad human deeds and actions that is why we are experiencing changes in climate’ and they went on to say that there are many atrocities going on nowadays in our society which are against the teachings of the holy scriptures. Ashraf et al. (Citation2014) and Iqbal et al. (Citation2018) found similar instances in which some of the responses were linked to religious beliefs in Pakistan and Afghanistan. Religious belief is considered an essential factor in recognizing and reacting to natural hazards in Afghanistan, according to Iqbal et al. (Citation2018). Others claim that natural disasters have historically been viewed as ‘acts of God’ or exoteric powers against which mankind had no protection, and that religion and culture can affect interpretations more than experience in purely religious cultures (Idrissou et al. Citation2020). This finding is similar to that of Lumborg et al. (Citation2021), who reported that farmers argue that shrinking and degradation of grazing lands, as expressed by communities and animal health workers, is a major concern for pastoralists in Ethiopia.

According to Idrissou et al. (Citation2020), environmental changes are influenced by factors such as human activities and climate change. Farming practices such as repeated bushfires, deforestation, slash and burn, overgrazing and the reduction of fallow periods result in the degradation of vegetation and soil, favouring the release of greenhouse gases, e.g. CO2 into the atmosphere (Idrissou et al. Citation2020). Moreover, the researchers in this study observed more human activities in the environment such as slash and burn, bushfires and deforestation which resulted in the formation of a large piece of bare land. Results obtained in FGDs of this study showed an agreement with the findings of Mavhura et al. (Citation2021), Lumborg et al. (Citation2021) and Sanou et al. (Citation2018). They also reported that farmers observed decreased fertility, milk production and meat as a result of Climate Change and variability in animals. Increased morbidity and mortality in livestock are also a result of a rise in certain vector-borne diseases (Sanfo et al. Citation2015; Idrissou et al. Citation2020). The FGD's findings () indicate that The Gambia's livestock productivity has been significantly impacted by climate variability. These results are also similar to the findings of other researchers in the sub-Saharan region (Olaniyan Citation2017; Ali et al. Citation2020), who also reported that climate variability has seriously affected livestock production in The Gambia. The respondents’ opinion about temperature and rainfall variability is that they enhanced stress, lessen pasture and water accessibility (Idrissou et al. Citation2020; Mavhura et al. Citation2021). Chi-square analysis test () shows that region of residence, age and occupation were the only demographic variables that showed a statistically significant association with all the questions asked on the impact of climate variability on animal husbandry. This suggests that livestock owners in The Gambia are well aware of the profound impact of climate variables on their livelihood. Additionally, chi-square analysis test () shows that region of residence, occupation and educational level were highly significant in determining livestock farmers’ perception of changes in rainfall in their communities. As for their perception of temperature changes, the region of residence of the livestock farmers age, occupation and educational level also showed statistical association with livestock farmers’ perception of temperature in their communities. The results of binomial logistic regression show that the age and residence of livestock farmers were the main factors influencing their perceptions of rainfall, while the region of residence and the main occupation of livestock farmers were the main factors influencing livestock farmers’ perceptions of temperature. Our result is consistent with previous findings that socio-demographic characteristics affect farmers’ perceptions of the causes and impact of climate variability (Sanogo et al. Citation2017; Mavhura et al. Citation2021). However, these results are in contrast with the studies of Odewumi et al. (Citation2013) and Sanogo et al. (Citation2017) who reported no effects of any demography variable on the perception of farmers towards Climate change and variability. The results of this present study further suggest that age is a strong indicator of farmers’ perceptions of changes in rainfall pattern and changes in temperature in The Gambia. Indeed, older farmers have been subjected to changes in climate variability more than younger farmers (Sanogo et al. Citation2017). Furthermore, the region of residence of farmers is also a good predictor associated with the farmers’ perception on the decrease of rain fall and temperature in The Gambia. Farmers living in NBR, LRR, CRR-N, CRR-S and URR of The Gambia better-perceived climate changes better because they are more prone to the adverse effects of climate change.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, this study has shown that based on their experiences and observations over the last three decades, livestock farmers in The Gambia have a good understanding of climate variability and also very conscious of climate change. This further goes on to show that climate variability is not a distant problem anymore as it is now perceived by most of the livestock farmers in The Gambia. Climate variabilities have been shown to have major economic consequences because they affect livestock farmers’ key economic activities in the country. Rainfall fluctuations and rising temperatures have been identified as major challenges to cattle production due to their impact on pasture and water supply, as well as disease threats. Cattle malnutrition and disease outbreaks, both of which result in cattle deaths, as well as a decline in milk production and market price, are serious consequences faced by livestock farmers in The Gambia.

The demographic variables of livestock farmers revealed a significant relationship with their responses to questions about the causes of climate variability and their impact on livestock. As a result, it is recommended that the government of The Gambia and other stakeholders should assist livestock farmers in dealing with the effects of climate variability and to also raise public awareness and activism about the causes of climate variability, its impacts and future adaptation and mitigation strategies. This can be achieved by institutionalizing an integrative approach involving the Meteorological Agency, climatologists, ecologists, epidemiologists and veterinarians.

Authors’ contributions

AK conceived the project idea. AK, HK and RK prepared the research instruments. AK, AB, EJ, AIA, KFJA, DZ and MN collected all the necessary data, analysed and drafted the manuscript. The study was guided and supervised by HK and RK. All co-authors reviewed and discussed the results, helped in the interpretation of the results, and contributed to the draft and final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This study is part of a Ph.D. degree for Alpha Kargbo at the Universite Felix Houphouet-Boigny. Alpha Kargbo was sponsored by a fellowship from the West African Climate Change and Adapted Land use program through the German Federal Ministry for Education and Research. The authors are thankful to the staff and management of WASCAL-Graduate Research Program in Climate Change and Biodiversity, Universite Felix Houphouet-Boigny and University of The Gambia, The Gambia for their moral support. We would also like to acknowledge the Department of Livestock Service, Ministry of Agriculture, The Gambia, for their cooperation during the study time. Finally, a special appreciation goes to Miss Aja Kargbo, Miss Amie Kargbo, Miss Kaddijatou Gissey and Mr Ansumana Jarjue for their invaluable support during the data collection of this work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agwu OP, Bakayoko A, Jimoh SO, Stefan P. 2018. Farmer’ perceptions on cultivation and the impacts of climate change on goods and services provided by Garcinia kola in Nigeria. Ecol Process. 7:36. doi:10.1186/s13717-018-0147-3.

- Ali MZ, Carlile G, Giasuddin M. 2020. Impact of global climate change on livestock health: Bangladesh perspective. Open Vet J. 10(2):178–188. doi:10.4314/ovj.v10i2.7.

- Ashraf M, Routray JK, Saeed M. 2014. Determinants of farmers’ choice of coping and adaptation measures to the drought hazard in northwest Balochistan, Pakistan. Nat Hazards. 73:1451–1473. http://hdl.handle.net/10.1007s11069-014-1149-9.

- Badjie M, Yaffa S, Sawaneh M, Bah A. 2019. Effects of climate variability on household food availability among rural farmers in Central River Region-South of The Gambia. Clim Change. 5(17):1–9.

- Bagagnan AR, Fonta WM, Ouedraogo I. 2019. Perceived climate variability and farm level adaptation in the Central River Region of The Gambia. Atmosphere (Basel). 10(7):423. doi:10.3390/atmos10070423.

- Bah OA, Kone K, Yaffa S, Sawaneh M, Kone D. 2019. Fishers’ perceptions of climate change on freshwater fisheries and the role of these systems in their adaptation strategy in central river region of The Gambia. Int J Agric Environ Res. 4(2):507–522.

- Challinor AJ, Watson J, Lobell DB, Howden SM, Smith DR, Chhetri N. 2014. A meta-analysis of crop yield under climate change and adaptation. Nat Clim Change. 4(4):287–291. doi:10.1038/nclimate2153.

- Cham FO, IC A, Sawanneh M, Secka A, Yaffa S. 2018. Climate variability perception and adaptation: differences between male and female cattle owners. Int J Agric Environ Res. 4(1).

- Dakurah G. 2020. How do farmers’ perceptions of climate variability and change match or and mismatch climatic data? Evidence from north-west Ghana. GeoJournal. doi:10.1007/s10708-020-10194-4.

- Eguavoen I, Schulz K,De Wit S, Weisser F, Müller-Mahn D. 2015. Political dimensions of climate change adaptation: conceptual reflections and African examples. In: Handbook of climate change adaptation. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; p. 1183–1199.

- Fagariba C, Song S, Baoro S. 2018. Climate change adaptation strategies and constraints in northern Ghana: evidence of farmers in Sissala West district. Sustainability. 10:1484. doi:10.3390/su10051484.

- GBOS. 2017. Integrated household survey 2015/16, Volume II Socio-economic characteristics, Gambia Bureau of Statistics (GBOS), The Government of The Gambia, Banjul, The Gambia [accessed 2020 October 14]. https://www.gbosdata.org/downloads/gdp-2017-42.

- Getachew S, Teshager M, Tilahun T. 2014. Determinants of agro-pastoralist climate change adaptation strategies: case of Rayitu Woredas, Oromiya Region, Ethiopia. Res J Environ Sci. 8:300–317. doi:10.3923/rjes.2014.300.317.

- Idrissou Y, Assani AS, Baco MN, Traor IA, Yabi AJ. 2020. Adaptation strategies of cattle farmers in the dry and sub-humid tropical zones of Benin in the context of climate change. Heliyon. 6(2020):e04373 [accessed 2021 April 5]. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04373.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), et al. 2018. Summary for policymakers. In: Masson-Delmotte V, Zhai P, Pörtner H-O, Roberts D, Skea J, Shukla PR, Pirani A, Moufouma-Okia W, Péan C, Pidcock R, editor. Global warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC special report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty. Geneva, Switzerland: World Meteorological Organization; p. 32 [accessed 2021 May 1]. https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/chapter/spm/.

- Iqbal MW, Donjadee S, Kwanyuen B, et al. 2018. Farmers’ perceptions of and adaptations to drought in Herat Province, Afghanistan. J Mt Sci. 15:1741–1756. doi:10.1007/s11629-017-4750-z.

- Jaiteh MS, Sarr B. 2011. Climate change and development in the gambia: challenges to ecosystem goods and services. A Technical Report. 57. http://www.columbia.edu/~msj42/pdfs/ClimateChangeDevelopmentGambia_small.pdf. 20 August 2021.

- Kargbo A, Kuye RA. 2020. Epidemiology of tsetse flies in the transmission of trypanosomiasis: technical review of The Gambia experience. Int J Biol Chem Sci. 14(3):1093–1102. doi:10.4314/ijbcs.v14i3.35.

- Kimaro EG, Mor SM, Toribio JLML. 2018. Climate change perception and impacts on cattle production in pastoral communities of northern Tanzania. Pastoralism. 8(19). doi:10.1186/s13570-018-0125-5.

- Lacetera N. 2019. Impact of climate change on animal health and welfare. Anim Front. 9(1):26–31. doi:10.1093/af/vfy030.

- Leal Filho W, Ternova L, Parasnis SA, Kovaleva M, Nagy GJ. 2022. Climate change and zoonoses: A review of concepts, definitions, and bibliometrics. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 19(893). doi:10.3390/ijerph19020893.

- Lumborg S, Tefera S, Munslow B, Mor SM. 2021. Examining local perspectives on the influence of climate change on the health of Hamer pastoralists and their livestock in Ethiopia. Pastoralism. 11:10. doi:10.1186/s13570-021-00191-8.

- Marselle MR, Dallimer M, Irvine KM, Martens D. 2019. Review of the mental health and well-being benefits of biodiversity. In: M. R. Marselle, J. Stadler, H. Korn, K. Irvine, A. Bonn, editor. Biodiversity and health in the face of climate change. Cham: Springer International Publishing; p. 175–211. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-02318-8_9.

- Mavhura E, Manyangadze T, Aryal KR. 2021. Perceived impacts of climate variability and change: an exploration of farmers’ adaptation strategies in Zimbabwe’s intensive farming region. GeoJournal. doi:10.1007/s10708-021-10451-0.

- Megersa B, Markemann A, Angassa A, Ogutu JO, Piepho HP, Zaráte AV. 2014. Impacts of climate change and variability on cattle production in southern Ethiopia: perceptions and empirical evidence. Agric Sys. 130:23–34. doi:10.1016/j.agsy.2014.06.002.

- Meijer SS, Catacutan D, Ajayi OC, Sileshi GW, Nieuwenhuis M. 2015. The role of knowledge, attitudes and perceptions in the uptake of agricultural and agroforestry innovations among smallholder farmers in sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Agric Sustain. 13:40–54.

- Montag D, Kuch U, Rodriguez L, Müller R. 2017. Overview of the panel on biodiversity and health under climate change. In: Rodríguez L, Anderson I, editor. Secretariat of the convention on biological diversity. The Lima declaration on biodiversity and climate change: contributions from science to policy for sustainable development, technical series no.89. Montreal: Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity; p. 91–108, 156 [accessed 2021 March 7]. https://www.cbd.int/doc/publications/cbd-ts-89-en.pdf.

- Ochieng J, Kirimi L, Makau J. 2016. Adapting to climate variability and change in rural Kenya: farmer perceptions, strategies and climate trends. Nat Resour Forum. 41:195–208.

- Odewumi SG, Awoyemi OK, Iwara AI, Ogundele FO. 2013. Farmer’s perception on the effect of climate change and variation on urban agriculture in Ibadan Metropolis, South-western Nigeria. J Geogr Reg Plan. 6:209–217. doi:10.5897/JGRP2013.0370.

- Olaniyan OF. 2017. Adapting Gambian women livestock farmers’ roles in food production to climate change. Future of food. J Food Agric Soc. 5(2):56–66.

- Olaniyan OF, Orunmuyi M. 2017. Promoting farmers’ resilience to climate change: an option of the N’Dama cattle in West Africa. climate change adaptation in Africa. Springer; p. 345–356. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-49520-0_21.

- Sanfo A, Sawadogo I, Kulo EA, Zampaligre N. 2015. Perceptions and adaptation measures of crop farmers and agropastoral in the eastern and plateau central regions of Burkina Faso, West Africa. FIRE J Sci Technol. 3:286–298.

- Sanou CL, Tsado DN, Kiema A, Eichie JO, Okhimamhe AA. 2018. Climate variability adaptation strategies: challenges to livestock mobility in south-eastern Burkina Faso. Open Access Library J. 5:1–17. doi:10.4236/oalib.1104372.

- Sanogo K, Binam J, Bayala J, Villamor GB, Kalinganire A, Dodiomon S. 2017. Farmers' perceptions of climate change impacts on ecosystem services delivery of Parklands in Southern Mali. Agroforest Syst. 91:345–361.

- Weindl I, Lotze-Campen H, Popp A, Mueller C, Havlik P, Herrero M, Schmitz C, Rolinski S. 2015. Livestock in a changing climate: production system transitions as an adaptation strategy for agriculture. Environ Res Lett. 10(2015):094021. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/10/9/094021.

- World Bank Group. 2021. World Bank Climate Knowledge Portal, The Gambia Climate data historic [accessed 2021 March 11]. https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/country/gambia/climate-data-historical.

- Yamane T. 1967. Statistics, an introductory analysis, 2nd Ed. New York: Harper and Row.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Survey questionnaire on ‘Livestock owner’s perceptions towards the causes and impact of climate variability in The Gambia’

Demographic information

Gender 1 = Male [ ], 2 = Female [ ]

How old are you? (in years)

What is your ethnic group? 1 = Mandinka [ ]; 2 = Fula [ ]; 3 = Jola [ ]; 4 = Wolof [ ]; 5 =others [ ]

What is your main economic activity? 1 = Herdsmen [ ]; 2 = Crop farming [ ]; 3 = Livestock farming [ ]; 4 = Crop and livestock farming [ ]; 5 = Petty trading [ ]; 6 = Others specify-

What is your highest level of education? 1 = Primary [ ]; 2 = Secondary [ ]; 3 = Tertiary/University []; 4 = Informal/Madarasa [ ]; 5 = None [ ]

What type of livestock animal do you rear? (multiple answer if possible) 1 = Cattle [ ]; 2 = Donkey [ ]; 3 = Horse [ ]; 4 = Pig [ ]; 5 = Camel [ ]

How many animals do you have as answered in 6 [ ]

Livestock dealers, livestock owners and herdsmen knowledge and perception on climate variability and its impact on cattle production

Have you observed any changes in temperatures in the last 10 years? 1 = Yes [ ]; 2 = No [ ]

If yes, what had caused changes in temperature? 1 = Not sure [ ]; 2 = Natural cause [ ]; 3 = Humans [ ]; 4 = Natural and humans causes [ ]; 5 = Other (specify) … … … … … … … … … … … … … .

If temperature pattern has changed, how has these changes affected your cattle rearing?

1 = Less availability of pasture [ ]; 2 = High availability of pasture [ ]; 3= No changes [ ]; 4= I don’t know [ ]; 5 = Others (specify)

Have you observed any changes in rainfall in the last 10 years? 1 = Yes [ ]; 2 = No [ ]

If yes, what had caused changes in rainfall? 1 = Not sure [ ]; 2 = Natural cause [ ]; 3 = Humans [ ]; 4 = Natural and humans causes [ ]; 5 = Other (specify) … … … … ..

If Rainfall pattern has changed, how has these changes affected your cattle rearing? 1 = Less availability of pasture [ ]; 2 = High availability of pasture [ ]; 3 = No changes [ ]; 4 = I don’t know [ ]

How often do you talk about these changes with other herdsmen, family and/or extension workers? 1 = Never [ ]; 2 = Rarely (once a month) [ ]; 3 = Sometimes (once a week) [ ]; 4 = Often (more than once a week) [ ]; 5 = Seasonally [ ]

What changes have you observed in the vegetation in the past 10 years? 1 = Decreased [ ]; 2 = Increased [ ]; 3= No changes [ ]; 4= Do not know [ ]; 5= Other (specify) … … … … .

How did you perceive changes in rain fall patterns on the vegetation on the grazing area? 1 = Severely affect [ ]; 2 = Moderately affect [ ]; 3 = Fairly affect [ ]; 4 = No effect [ ]; 5 = I don’t know [ ]

What are the order impact do you think changes of rainfall patterns and temperature fluctuation has on livestock production

Appendix 2

Questionnaires for focal group discussion

Have you observed changes in rainfall pattern for the last 10 years?

If yes, what do you think is the impact of the increase and decrease of rainfall on livestock production?

Have you observed changes in temperatures for the last 10 years?

If yes, what do you think is the impact of the increase and decrease of temperature on livestock production?

Any other comment