?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The willingness of consumers to buy animal welfare products is an important support for the transformation of animal husbandry to animal welfare. However, animal welfare farming often means a considerable capital investment, which often increases the likelihood of price increases for the products. The main purpose of this study is to assist in the marketing of animal welfare products through the research results and then promote the transformation of animal husbandry to animal welfare-friendly agriculture. The analysis results showed that consumers’ moral attitudes towards animal products significantly affect perceived higher prices and buying willingness, while perceived higher prices negatively affect buying willingness. Still, fortunately, the negative impact is not significant. Based on the findings, a discussion of academic and managerial implications is provided at the end of this article.

1. Introduction

Although studies have shown that consumers have positive attitudes toward ethical goods, a willingness to buy often does not necessarily follow (White et al. Citation2012). For example, Heng et al. (Citation2013) found that consumers are willing to pay higher prices for animal welfare (AW) products, but from market practice, relatively higher prices still have a significant negative impact on consumer purchases. For example, Bennett et al. (Citation2002) showed that only 34% of the respondents would transform positive attitudes into actual actions to ‘avoid’ buying livestock products produced under non-AW conditions.

In the past, veterinarians and farmers primarily considered AW in terms of animals’ physical health and breeding environment. However, more recently, researchers have suggested that AW should adequately include ‘psychological feelings’ and advocate the conservation of animals’ ‘natural needs’ (Appleby et al. Citation1993; Janczak and Riber Citation2015). In other words, on a humane basis, livestock farmers must meet the natural behavioural needs of animal life. Therefore, the generally accepted definition of AW is ‘the physical and mental state of an animal in relation to the conditions in which it lives and dies’ as defined by the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) (Citation2022).

Moral Foundation Theory (MFT) contends that human beings have five foundational moral attributes, including care/harm, fairness/cheating, loyalty/betrayal, authority/subversion, and sanctity/degradation (Haidt Citation2012). According to the MFT, the morals of individuals’ concern refer to caring, fairness, loyalty, authority, and sanctity, whereas caring and fairness refer to an individualized cluster (Graham et al. Citation2009). Fu and Yen (Citation2002) asserted that moral decision making is often based on an individual’s attitude regarding ‘goodness’, and the AW feeding methods include human care and fair treatment of animals; thus, AW can be considered from a moral perspective, and AW products can also be classified under the ethical goods category.

Consumers’ moral attitudes toward purchases are imbued with personal judgments and feelings about right and wrong (Brandt and Wetherell Citation2012) and purchasing decisions regarding ethical goods often depend on personal attitudes toward the results of right and wrong judgments. Teasley (Citation2016) defined moral decision making as an individual’s choice among options, which often presents a dilemma in which the wellbeing of oneself or others is threatened, and the decision to purchase ethical goods often falls into a dilemma of ‘doing the right thing’ and buying expensive products. Undoubtedly, moral attitudes do have an important influence on consumers’ purchasing decisions, particularly products that are associated with ethical issues. Although the individual effects of attitudes (Olsen et al. Citation2010; Leeuw et al. Citation2011; Jiang et al. Citation2018) and prices (Heng et al. Citation2013; Yang Citation2018) on purchase intention are more understandable, less is known regarding the combined effects of moral attitudes and perceived higher prices on consumers’ willingness to buy. Therefore, the primary research question of this study is ‘When consumers perceive ethical goods as more expensive, can their moral attitudes go beyond perceived higher prices to decisively influence their willingness to purchase?’

Consumers’ willingness to buy AW products is an important motivator for the transformation of livestock to AW. Liao (Citation2018) stated that animals’ welfare status can be used as an important indicator of the management status of livestock farms. However, AW farming often means a considerable capital investment, which often increases the likelihood of price increases for products. Therefore, the primary purpose of this study is to provide practical insights into effectively marketing AW products to encourage the transformation of animal husbandry to AW-friendly agriculture.

2. Literature review

2.1 Theories relevant to moral decision making

Rest (Citation1979) proposed a four-component model related to the development of moral behaviour, asserting that the formation of moral behaviour includes recognizing moral issues, making moral judgments, generating moral behavioural intention, and implementing moral behaviour in the moral decision making process. Rest’s model introduced the concept of moral cognition, contending that the basic premise of moral decision making is that individuals must first recognize the associated moral issues.

In addition, MFT proposes five moral foundations, which have generally been applied to political ideology (Haidt and Graham Citation2007; Haidt Citation2012), cross-cultural differences (Henrich et al. Citation2010), and gender differences (Atari et al. Citation2020). For marketing, LeMay et al. (Citation2012) argued that the ethical basis of MFT may have implications for marketing content. Chowdhury (Citation2019) contended that MFT can serve as a theoretical framework for explaining individuals’ beliefs about moral and immoral consumption, wherein caring and fairness are associated with positive beliefs about doing good, and moral attitudes that support ethical consumption are not necessarily the same as those that condemn immoral behaviour. Kohlberg (Citation1958) indicated that individuals must first internalize social rules and judge the morality of behaviour by comparing it with social perspectives and expectations. Although moral consciousness is present in consumers’ minds, most consumers focus on behaviour (buying) and direct consequences (it is expensive) to explain the concept of right and wrong in terms of AW products. Due to the lack of AW knowledge, ‘buying AW products’ and ‘buying ethical products’ are completely decoupled.

Koklic (Citation2011) determined that the intensity of consumers’ moral cognition of goods will affect their moral attitudes toward goods, influencing purchase intentions. In addition, Qin and Brown (Citation2008) indicated that the essence of different attitudes toward genetically engineered (GE) food between men and women is that women are more concerned about the moral issues of GE food, and the differences in moral attitudes are the major reason for the differing purchase intentions. Chang and Chen (Citation2022) asserted that consumers’ attitudes based on internal moral emotions (moral attitudes) significantly affect the willingness to purchase products based on moral beliefs.

The basic premise of moral decision making is recognizing the moral issues of things (Rest Citation1979), while moral foundations, such as caring and fairness, are related to positive beliefs in doing good/right things (Haidt and Joseph Citation2004). Based on the research contributions regarding the correlation of moral attitudes with ethical product purchase intentions (Qin and Brown Citation2008; Koklic Citation2011; Chang and Chen Citation2022), this study argues that if consumers have knowledge about AW, they will internalize the goodness/rightness of AW and the willingness to buy AW products will increase accordingly. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

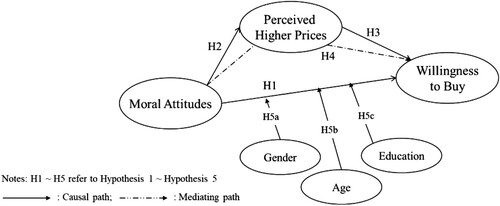

H1: Consumers’ moral attitude toward animal welfare products positively affects their willingness to buy products.

2.2 Moral attitudes, perceived higher prices, and willingness to buy

In this study, higher price refer to buyers having to pay a higher price for AW products than conventionally produced livestock products. In the AW systems, the production of AW products requires relatively large capital investment and management costs (Sumner et al. Citation2011). As transitioning from conventional livestock farming methods to AW-friendly feeding systems may lead to increased production costs, this may increase the likelihood of higher retail prices.

When marketing AW products, consumers will perceive that they are more expensive than conventional livestock products. The production of AW products is proven to be animal-friendly and humane, which greatly enhances the moral attitudes of consumers toward the products. As consumers gain knowledge regarding the differences between AW production systems and conventional livestock farming methods, they will recognize the morality of products (generating moral attitudes), and understand the high production costs of AW products. Therefore, this study argues that consumers’ moral attitudes toward AW lead them to perceive AW products as more expensive.

Elliott and Freeman (Citation2004) contended that consumers are increasingly concerned about the ethical connotation of products and are willing to pay more for ethical products. Sumner et al. (Citation2011) also indicated that more and more consumers are willing to pay a premium for humane and friendly feeding methods. Despite the evidence in this research, it still does not indicate that most consumers are willing to pay for high-priced ethical products (Bennett et al. Citation2002). This is because, in general, perceived higher prices will reduce consumers’ willingness to buy; therefore, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H2: Moral attitudes regarding animal welfare products positively affect consumers’ perceptions of high price for the products.

H3: Perceived higher prices negatively affect consumers’ purchase willingness.

2.3 Mediating role of perceived higher prices

This study endeavours to answer the question ‘If consumers perceive higher prices for ethical goods, do their moral attitudes go beyond perceived higher prices to decisively influence the willingness to buy ethical goods?’ Cheng et al. (Citation2006) found that price level has a significant impact on consumers’ purchase intention. This study explores consumers’ willingness to buy AW products from the perspective of moral attitudes, aiming to assist the livestock industry in planning marketing strategies for AW products. The relatively higher prices of AW products are a major concern. Marketers will welcome the knowledge that consumers’ ethical attitudes toward AW products can effectively stimulate the buying willingness, but are concerned regarding this stimulating effect being weakened by the mediating effect of perceived higher prices. Therefore, this study attempts to verify the mediating effect of perceived higher prices and provide suggestions for future marketing strategies. Accordingly, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H4: Perceived higher prices for AW products have a negative mediating effect on the relationship between moral attitudes and consumers’ willingness to buy the products.

2.4 Customer differences

Attracting, acquiring, and retaining customers is the most important purpose for enterprises to conduct targeted marketing activities, and customer segmentation can help marketers better target potential customers with strategic marketing activities. Demographic variables are the key to customer segmentation; thus, comparing differences among customers through demographic variables is of considerable value for the development of marketing strategies. Yang (Citation2018) confirmed that age, income, education, occupation, and religious beliefs affect consumers’ willingness to purchase AW eggs. Fumagalli et al. (Citation2010) found that the cognitive–affective processes involved in assessing an individual’s moral values differ by gender. Qin and Brown (Citation2008) confirmed that women prioritize moral issues more highly. To effectively assist marketers’ customer segmentation, in this study, demographic variables, such as gender, age, and education level, are used to determine consumer differences. In this regard, the hypotheses concerning the comparison of consumer differences are as follows:

H5a: There are significant differences between male and female consumers in terms of the influence of moral attitudes on willingness to purchase.

H5b: There are significant differences between young and old consumers in terms of the influence of moral attitudes on purchase intentions.

H5c: There are significant differences between consumers with higher and lower levels of education in terms of the influence of moral attitudes on purchase intentions.

This study proposes a research model () illustrating the causal paths among moral attitudes, perceived higher prices, and willingness to buy AW products, as well as differences concerning gender, age, and education on the effects of moral attitudes on willingness to buy.

3. Methodology

3.1 Research object

Battery cage feeding is a common way of raising laying hens in Taiwan. Eggs produced in battery cages are cheaper due to relatively low capital investment and ease of management. However, two to three laying hens are raised in a small cage space of about 350–450 square centimetres, which is about the size of an A4 piece of paper. The hens in the battery cages have difficulty even turning around, and they are unable to engage in natural behaviours, such as running, jumping, spreading their wings, grooming, grinding their claws, perching, forging, and laying eggs in a nest. In such confined circumstances, hens often peck at each other or even trample one another to death. The harsh living environment places the hens in an unhealthy state, both physically and mentally. Currently, battery cage-rearing is considered unfriendly to laying hens and was banned in the European Union in 2012. According to Definition and Guidelines for Egg-Friendly Production System (Council of Agriculture Citation2015), AW eggs refer to eggs that are produced using the AW housing systems, including enriched cage, barn, and free-range housing systems.

Considering that the AW conditions of laying hens is currently one of the most important economic AW issues in Taiwan, this study uses the AW housing systems of laying hens as the research example and focuses on marketing AW eggs to explore consumers’ buying willingness, sampling households’ main decision makers of egg purchases.

3.2 Questionnaire development and sampling

Based on the literature, this study referenced the research scales of Singhapakdi et al. (Citation1996); Fu and Yen (Citation2002); Bansal et al. (Citation2005); Duffett (Citation2015); and Shaouf et al. (Citation2016). The scales were revised according to the characteristics of AW eggs, using eight questions to measure moral attitudes, four questions to measure perceived higher prices, and four questions to measure purchase intentions. A five-point Likert scale (from strongly disagree = 1 to strongly agree = 5) was adopted in the questionnaire design.

This study developed an online questionnaire using Google Forms to reach a wide range of consumers. In addition to the measurement items of each construct, the questionnaire also requested (anonymous) personal information from the respondents, including the demographic variables of gender, age, and education level. In addition, the questions ‘Are you a decision maker for household egg purchases?’ ‘Have you heard of animal welfare eggs?’ and ‘Have you ever bought animal welfare eggs?’ were asked to ensure the reach of research objects and to examine consumers’ general awareness of AW eggs.

Before answering the measurement items regarding the study’s constructs, respondents were first asked to indicate their knowledge of AW eggs with the question ‘How much do you know about animal welfare eggs so far?’ (five-point Likert scale). We then provided a brief description of AW housing systems and asked the same question again after the description was read.

A convenience sampling procedure was conducted via Line, Facebook, and email to invite participants to complete the questionnaire. A total of 247 samples were collected for the study over a limited period of two months. After excluding invalid samples (non-research objects), 230 valid samples remained with a valid response rate of 93.12%. In the sample collected, there were 120 (52.2%) female respondents and 110 (47.8%) male respondents. This result is consistent with the data from the National Development Council (Citation2018–Citation2021), showing that there are more women in Taiwan than men, indicating that the sample used in this study is representative. In addition, since the research object is the main decision maker for household egg purchases, it is reasonable that most of the respondents are in the 21–60 age group (93.4%). Finally, the proportion of highly educated (90.8%, including undergraduate and graduate students) in this study is also reasonable because Taiwan is a highly educated nation.

4. Analysis and results

Structural equation modelling (SEM), a statistical method that is commonly used to analyse causal patterns, can simultaneously address relationships between multiple variables, allowing researchers to reliably measure hypothesized relationships between theoretical structures (Deng et al. Citation2018). This study used IBM SPSS AMOS statistical software because it extends standard multivariate analysis methods, including regression, factor analysis, correlation, and analysis of variance, which reflect complex relationships more accurately than using standard multivariate statistical techniques.

4.1 Analysis of measurement model

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted in the measurement model analysis to verify the fit of our measurement model and the reliability and validity of each construct.

4.1.1 Model fit

In CFA, the factor loading of MA1 of the moral attitudes construct is lower than 0.50, while the modification indices of MA2, 4, 8 of moral attitudes, PHP1 of perceived higher prices, and BW1 of buying willingness were all higher than 3.84 threshold suggested by Jöreskog and Sörbom (Citation1993); therefore, these constructs were all removed at this stage.

Finally, analysis results, including 54.289, p = 0.008,

f = 1.697, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.055, the goodness of fit index (GFI) = 0.956, the adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI) = 0.924, the normed-fit index (NFI) = 0.974, the incremental fit index (IFI) = 0.989, the relative fit index (RFI) = 0.963, the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) = 0.984, and the comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.989, indicated a good fit of the proposed measurement model.

4.1.2 Reliability and validity

At this stage, the factor loads of each item were greater than 0.50 (0.817–0.946), the composite reliability (CR) of each construct was greater than 0.70 (0.908–0.948), and the average variance extracted (AVE) of each construct was greater than 0.50 (0.755–0.858), confirming the reliability and convergent validity of each construct. presents the detailed analysis results of reliability and convergent validity.

Table 1. Reliability and convergent validity analysis

For discriminant validity, this study applied the principles suggested by Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981). The analysis results in indicate that the square root of AVE for each construct on the diagonal of the table is greater than the Pearson’s correlation coefficient between the constructs; thus, the discriminative validity of each construct is confirmed in this study.

Table 2. Discriminant validity (Fornell–Larcker criterion).

4.2 Structural model analysis

Path analysis was next conducted to verify the structural model fit and test the study’s hypotheses.

4.2.1 Structural model fit

In this stage, analysis results included CMIN = 54.289, p = 0.008, CMIN/DF = 1.697, RMSEA = 0.055, GFI = 0.956, AGFI = 0.924, NFI = 0.974, IFI = 0.989, RFI = 0.963, TLI = 0.984 = 0.984, and CFI = 0.989, confirming the structural model’s fit.

4.2.2 Path analysis

For path analysis, hypotheses H1–H3 were next tested. The analysis showed that the proposed causal paths from moral attitudes to buying willingness (H1: β = 0.735, t = 10.901, p = 0.000) and from moral attitudes to perceived higher prices (H2: β = 0.305, t = 4.266, p = 0.000) are significant and positive, while the path from perceived higher prices to buying willingness was negative but not significant (H3: β = −0.095, t = −1.692, p = 0.091).

4.2.3 Mediating effect

This study also applied the bias-corrected (BC) percentile method of bootstrapping using AMOS software to measure the mediating effect of perceived higher price. The results in show that the indirect effect of moral attitudes → perceived higher prices → buying willingness is −0.029 (p = 0.051 > 0.05), while the confidence interval for the BC method includes 0 (−0.080–0.000); thus, the mediating effect of perceived higher prices was not statistically significant.

Table 3. Results of mediating effect test.

4.2.4 Comparison of customer difference

We grouped the sample for demographic variables prior to conducting the multigroup analysis, including gender (male = 110; female = 120), age (over 40 years old = 122; under 40 years old (inclusive) = 108), and education level (college level and above = 209; high school and below = 21). This study asserts that it is not appropriate to perform the multigroup analysis due to the unbalanced proportion of highly educated respondents (90.8%); therefore, the multigroup analysis of education level was cancelled.

Although the value of the model fit for each model was not as good as that of the overall structure model due to the reduction of the sample size, it was still considered to be within an acceptable range ().

Table 4. Results of model fit test for each group.

Finally, the results of multigroup analysis () showed that there was no significant difference in the influence of moral attitudes on purchase intentions based on gender and age through p-values (gender = 0.523; age = 0.052) (see ).

Table 5. Results of multigroup analysis (Moral attitudes → Buying willingness).

4.3 Additional analysis

The research findings revealed that most of our Taiwanese participants had limited knowledge about AW eggs; therefore, to ensure that the respondents could successfully answer the construct items, we provided a brief description of the AW housing systems for laying hens. Moreover, to understand whether the brief description improved respondents’ understanding of the systems, we asked respondents to record their conscious understanding of AW eggs before and after reading the description, using the responses to conduct a paired-sample t-test to investigate the difference between the two sets of data. The results revealed a significant difference between the two sets (), indicating that the overall respondents’ understanding of AW eggs after reading the description was significantly higher than before reading.

Table 6. Results of paired-sample t-test.

5 Discussion and conclusion

5.1 Discussion

Transformation of the livestock industry was included as one of the 169 subgoals in the 2015 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) announced by the United Nations. In response to this call for global transformation, WOAH listed AW issues among its priority strategies. This research supports the transformation of animal husbandry in the SDGs and AW farming advocated by the WOAH. The primary purpose of this study is to accelerate more livestock farmers’ willingness to engage in AW farming through advancing consumers’ understanding, demand, and purchase of AW products.

In the past, researchers have proposed that quality, food safety, and taste are the main factors affecting consumers’ intentions to purchase AW eggs (e.g. Yang Citation2018). However, although the production traceability of AW eggs has been practiced in Taiwan for many years, many more rigorous agricultural product certification marks have also been established in Taiwan for food quality and safety, such as Certified Agricultural Standards (CAS), Traceable Agriculture Product (TAP), Taiwan Good Agricultural Practice (TGAP), Taiwan Quality Food (TQF), and ISO 22000 designations are used to strictly control the quality and safety of agricultural products, and many battery cage eggs are capable of passing such certifications. As for any slight difference in taste (Yang Citation2018), are consumers really able to differentiate?

Using AW egg as an example of AW products, we found that AW eggs and conventional battery cage eggs have obvious humane differences in laying hens’ housing systems. We were compelled to ask, when ‘humanitarian cognition’ (moral attitude toward AW eggs) interacts with ‘self-interested tendencies’ (seeking the lowest price), does consumers’ selection of eggs follow their ‘moral attitude’ (buying AW eggs) or will they select the lower priced battery cage eggs due to self-interested tendencies? The results of this study demonstrated that moral attitudes not only positively and significantly affect consumers’ willingness to buy AW eggs (t = 10.901***), but also significantly positively affect consumers’ perceptions of higher prices (t = 4.266***). The impact of perceived higher price on consumers’ willingness to purchase AW eggs is negative (t = −1.692), but this negative impact is fortunately not significant (p = 0.091 > 0.050).

5.1.1 Academic implications

The findings of Heng et al. (Citation2013) indicated that consumers are willing to pay higher prices for eggs produced by non-cage methods, and the results of this study can be used as empirical evidence for what the authors found to explain consumer behaviour. LeMay et al. (Citation2012) and Chowdhury (Citation2019) contended that MFT can be used as a theoretical framework to explain consumer behaviour. This study subsequently applied MFT as a theoretical background, determining that based on the life caring and fair treatment of animals (two moral foundations of MFT), consumers’ positive moral attitudes toward AW products can significantly increase the willingness to purchase.

Previous animal husbandry research related to AW has primarily focused on feeding methods, production management, facility innovation, capacity management, animal transportation, slaughter, the traceability of agricultural products, quality certification, food processing, food safety, and investigations regarding animal protection (e.g. Appleby and Hughes Citation1991; Appleby et al. Citation1993; Baxter Citation1994; Hewson Citation2003; Blokhuis et al. Citation2007; Rodenburg et al. Citation2008; Sumner et al. Citation2011; Janczak and Riber Citation2015; Bennett et al. Citation2016). In contrast to previous research, this study explores consumers’ buying decisions regarding AW products from the perspective of moral attitudes and perceived higher prices, using the theoretical background of MFT.

First, this study includes AW products in the category of ‘ethical products’ to examine the causal relationships among moral attitudes, perceived higher prices, and willingness to buy. Schwepker and Ingram (Citation1996) defined moral attitude as individuals’ judgment regarding whether something is moral. Martinez and Jaeger (Citation2016), Tan (Citation2002), and Gültekin (Citation2018) argued that attitudes toward morality reduce purchase intentions for unethical products (e.g. counterfeit or pirated goods). Consistent with these authors, the results of this study demonstrate that when the AW housing systems integrate the caring and fair treatment of animals, consumers will have a moral attitude toward AW products, which is the primary factor affecting consumers’ willingness to buy AW products. Gültekin (Citation2018) found that the higher price of certified (ethical) products raises consumers’ willingness to buy counterfeit (unethical) products, weakening the willingness to buy certified products. However, the results of this study indicated that when consumers judge AW products based on moral attitudes (caring and fairness), under the mediating influence of perceived higher prices and moral attitude, although perceived higher prices would negatively affect buying willingness (t = −1.692), it is not statistically significant (p = 0.091). Therefore, in answer to this study’s main research question, this study proposes that when the moral nature of products conflicts with individuals’ self-interested orientation, consumers’ moral attitude toward the product can supersede perceived higher prices as the main factor affecting the willingness to buy moral products. Since previous research has not provided similar results, this study requires follow-up academic investigation by future researchers.

Furthermore, in a literature review, Alonso et al. (Citation2020) determined that women and younger consumers were more likely to pay for welfare-friendly products, in contrast to the findings of this study that gender and age exhibited no significant differences. This aligns with the Chinese cultural concept of respecting life (Su and Martens Citation2017). This study proposes that individuals’ moral attitudes toward products will not change their willingness to buy ethical products due to differences in gender and age based on self-moral judgments regarding products, in alignment with the findings of Yang (Citation2018) and Heng et al. (Citation2013) indicating that consumers are willing to pay a premium to buy AW eggs.

This study contributes to academic literature in fields of ethical products, moral attitudes, animal welfare (AW), marketing, and consumer behaviour, also providing a novel research direction for scholars related to animal husbandry. Considering our research results, we expect that an increasing number of marketing researchers will be motivated to engage in the marketing and promotion of high-quality ethical agricultural products.

5.1.2 Management implications

The results of this study demonstrated that only 28.8% of the respondents had previously purchased AW eggs, which reflects the current circumstances regarding the Taiwan AW product market, which face two major marketing challenges. First, compared with conventional livestock products, due to higher production cost, the market price of AW products is often doubled, resulting in lower consumer acceptance. Second, compared with traditional livestock products, AW products have no distinctive features that can be used as marketing features. For example, many non-AW livestock products have been certified by government regulations, such as CAS, TAP, TGAP, TQF, and ISO 22000; thus, their performance in terms of food quality and safety cannot be questioned. In addition, although researchers have indicated that a lack of focus on AW may lead to poorer taste (Yang Citation2018), no research evidence has been produced, making this argument weak. Furthermore, any slight taste differences are assumed to be difficult for people to distinguish. Although the issue of AW has received extensive attention from governments and animal protection organizations in various countries, there is no clear AW marketing structure, other than the clear ban on battery cage farming in the EU for AW eggs.

The results of this study suggest a viable marketing structure for AW products, revealing that the ‘care and fairness’ inherent in the production process of AW products is the most significant marketing difference from conventional livestock products. Consumers’ moral attitude toward AW products can enhance their willingness to buy, and increasing consumers’ AW knowledge to improve their moral attitude toward AW products can solve the second marketing challenge above indicating that there is no obvious marketing highlight for AW products. Regarding the first marketing challenge of perceived higher prices, if marketing challenge two is solved, consumers’ moral attitudes can weaken the negative impact of perceived higher prices on willingness to buy. As for increasing consumer awareness of AW products, our additional analysis demonstrated that providing respondents with a brief description of the AW laying house system significantly increased their knowledge of AW eggs (mean increased from 2.4–4.1, p = 0.000). Therefore, it is recommended that livestock farmers, marketers, and the government systematically introduce the AW system to the public, publicizing that AW product purchases improve the lives of economic animals and can be considered a good deed that aligns with common social morality. This approach will advance strategic AW product marketing and facilitate livestock farmers’ transition toward AW-friendly methods to achieve the SDGs of animal husbandry.

Finally, our comparison of consumer differences revealed that the impact of moral attitudes on willingness to buy does not exhibit significant differences based on gender and age. According to the research results, this study recommends that AW product marketers focus on introducing the specific ethical elements of AW systems to all consumers, as opposed to emphasizing age and gender segmentation.

6 Conclusion

The willingness of consumers to buy AW products is an important motivator for the transition of animal husbandry to AW; however, AW farming often requires considerable capital investment, which often increases the likelihood of price increases for the product. In this study, taking AW eggs as an example AW product, we determined that there are obvious humane differences in the laying hen breeding system between AW eggs and conventional battery cage eggs. The analytical results of this study indicate that moral attitudes have a significant direct impact on willingness to buy and enhance consumers’ perception of higher prices, demonstrating that although perceived higher prices have a negative effect on the willingness to buy AW products, the effect is not significant. In addition, the perceived higher price does not mediate the relationship between moral attitudes and willingness to buy; therefore, marketers should not focus on the negative factor of the high price of AW products and should employ more active marketing initiatives to educate consumers regarding the manner in which AW animal husbandry cares for animals. We also found that differences in gender and age have an insignificant impact on the relationship between moral attitudes and willingness to buy AW products, suggesting that gender and age have no effect on consumers’ willingness to buy ethical products.

As the research background of this study, Taiwan has a limited land area and high population density; therefore, considerations of AW are bound to differ from countries with large land areas such as the EU. Furthermore, consumers’ moral attitudes toward AW products may vary across cultures. Therefore, future cross-national research on cultural differences between moral attitudes and willingness to buy is essential.

Based on the current market conditions of AW products in Taiwan, this study only used moral attitudes and perceived higher prices as predictors to explore consumers’ willingness to buy AW products. We argue that consumer knowledge and familiarity with AW-friendly production systems will certainly increase over time, at which time, factors, such as perceived value and consumer preferences, may be available for future research. Therefore, concerning the second research limitation regarding less predictors, future researchers should pay attention to market changes and conduct further in-depth research.

In addition, this study used AW eggs as the research example; however, there are many types of AW products, such as dairy and meat products. Since different AW products have different demands on AW in the production process, consumers may have different moral attitudes toward them. Subsequently, it is strongly recommended that future research examine different AW product categories individually or comparatively to expand the research considerations.

Finally, the study’s sampling process revealed that current Taiwanese respondents generally did not have AW knowledge and could not complete the questionnaire without an educational AW description. Therefore, we provided a brief description of AW before respondents’ answer. In the process of data analysis, we determined that it is essential to understand whether consumers’ awareness of AW can moderate the influence of moral factors on willingness to buy AW products to understand the importance of AW knowledge on AW product marketing more clearly. Therefore, we anticipate further research on this consideration in the future.

Acknowledgements

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created.

References

- Alonso ME, González-Montaña JR, Lomillos JM. 2020. Consumers’ concerns and perceptions of farm animal welfare. Animals (Basel). 10(3):385. doi:10.3390/ani10030385.

- Appleby MC, Hughes BO. 1991. Welfare of laying hens in cages and alternative systems: environmental, physical and behavioural aspects. Worlds Poult Sci J. 47(2):109–128. doi:10.1079/WPS19910013.

- Appleby MC, Smith SF, Hughes BO. 1993. Nesting, dust bathing and perching by laying hens in cages: effects of design on behaviour and welfare. Br Poult Sci. 34(5):835–847. doi:10.1080/00071669308417644.

- Atari M, Lai MH, Dehghani M. 2020. Sex differences in moral judgements across 67 countries. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 287(1937). doi:10.1098/rspb.2020.1201.

- Bansal HS, Taylor SF, James YS. 2005. "Migrating" to New service providers: toward a unifying framework of consumers' switching behaviors. J Acad Market Sci. 33(1):96–115. doi:10.1177/0092070304267928.

- Baxter MR. 1994. The welfare problems of laying hens in battery cages. Veter Rec. 134(24):614–619. doi:10.1136/vr.134.24.614.

- Bennett RM, Anderson J, Blaney RJ. 2002. Moral intensity and willingness to pay concerning farm animal welfare issues and the implications for agricultural policy. J Agric Environ Ethics. 15:187–202. doi:10.1023/A:1015036617385.

- Bennett RM, Jones PJ, Nicol CJ, Tranter RB, Weeks CA. 2016. Consumer attitudes to injurious pecking in free range egg production. Anim Welf. 25(1):91–100.

- Blokhuis HJ, Van Fiks Niekerk T, Bessei W, Elson A, Guémené D, Kjaer JB, Levrino M, Nicol GA, Tauson CJ, Weeks R, A C, et al. 2007. The LayWel project: welfare implications of changes in production systems for laying hens. Worlds Poult Sci J. 63(1):101–114. doi:10.1017/S0043933907001328.

- Brandt MJ, Wetherell GA. 2012. What attitudes are moral attitudes? The case of attitude heritability. Soc Psychol Personal Sci. 3(2):172–179. doi:10.1177/1948550611412793.

- Chang MY, Chen HS. 2022. Consumer attitudes and purchase intentions in relation to animal welfare-friendly products: evidence from Taiwan. Nutrients. 14(21):4571. doi:10.3390/nu14214571.

- Cheng SC, Chen CT, Huang JC. 2006. The influence of service guarantee, price information and corporate credibility on purchase intention. Tour Manag Res. 6(1):83–100.

- Chowdhury RM. 2019. The moral foundations of consumer ethics. J Bus Ethics. 158(3):585–601. doi:10.1007/s10551-017-3676-2.

- Council of Agriculture. 2015. Definition and guidelines of egg-friendly production system. [accessed 2021 August 11]. https://law.coa.gov.tw/glrsnewsout/LawContent.aspx?id = GL000691.

- Deng L, Yang M, Marcoulides KM. 2018. Structural equation modeling with many variables: a systematic review of issues and developments. Front Psychol. 9:580. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00580.

- Duffett RG. 2015. Facebook advertising’s influence on intention-to-purchase and purchase amongst millennials. Internet Res. 25(4):498–526. doi:10.1108/IntR-01-2014-0020.

- Elliott KA, Freeman RB. 2004. White hats or Don Quixotes? Human rights vigilantes in the global economy. In: Freeman RB, Hersch J, Mishel L, editors. Emerging labor market institutions for the twenty-first century; 2000, August 4-5. University of Chicago Press; p. 47–98. ISBN: 0-226-26157-3.

- Fornell C, Larcker DF. 1981. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research. 18(1):39–50. doi:10.1177/002224378101800104.

- Fu FL, Yen HC. 2002. Marketing ethical decision making by information service enterprises. MIS Rev. 12:31–56.

- Fumagalli M, Ferrucci R, Mameli F, Marceglia S, Mrakic-Sposta S, Zago S, Lucchiari C, Consonni D, Nordio F, Pravettoni G, et al. 2010. Gender-related differences in moral judgments. Cogn Psychol. 11:219–226.

- Graham J, Haidt J, Nosek BA. 2009. Liberals and conservatives rely on different sets of moral foundations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 96(5):1029. doi:10.1037/a0015141.

- Gültekin B. 2018. Influence of the love of money and morality on intention to purchase counterfeit apparel. Soc Behav Person: Inter J. 46(9):1421–1436. doi:10.2224/sbp.7368.

- Haidt J. 2012. The righteous mind: why good people are divided by politics and religion. New York (NY): Vintage.

- Haidt J, Graham J. 2007. When morality opposes justice: conservatives have moral intuitions that liberals may not recognize. Soc Justice Res. 20(1):98–116. doi:10.1007/s11211-007-0034-z.

- Haidt J, Joseph C. 2004. Intuitive ethics: how innately prepared intuitions generate culturally variable virtues. Daedalus. 133(4):55–66. doi:10.1162/0011526042365555.

- Heng Y, Peterson HH, Li X. 2013. Consumer attitudes toward farm-animal welfare: the case of laying hens. J Agric Resour Econ. 38(3):418–434.

- Henrich J, Heine SJ, Norenzayan A. 2010. The weirdest people in the world? Behav Brain Sci. 33(2-3):61–83. doi:10.1017/S0140525X0999152X.

- Hewson CJ. 2003. What is animal welfare? Common definitions and their practical consequences. Can Vet J. 44(6):496.

- Janczak AM, Riber AB. 2015. Review of rearing-related factors affecting the welfare of laying hens. Poult Sci. 94(7):1454–1469. doi:10.3382/ps/pev123.

- Jiang Y, Xiao L, Jalees T, Naqvi MH, Zaman SI. 2018. Moral and ethical antecedents of attitude toward counterfeit luxury products: evidence from Pakistan. Emer Mark Fin Trade. 54(15):3519–3538. doi:10.1080/1540496X.2018.1480365.

- Jöreskog KG, Sörbom D. 1993. LISREL 8: structural equation modeling with the SIMPLIS command language. Chicago (IL): Scient Soft Int.

- Kohlberg L. 1958. The development of modes of thinking and choices in years 10 to 16. Ph. D. dissertation. University of Chicago.

- Koklic MK. 2011. Non-deceptive counterfeiting purchase behavior: antecedents of attitudes and purchase intentions. J Appl Bus Res (JABR). 27(2):127–138. doi:10.19030/jabr.v27i2.4145.

- Leeuw AD, Valois P, Houssemand C. 2011. Predicting the intentions to buy fair-trade products: the role of attitude, social norm, perceived behavioral control, and moral norm. OIDA Int J Sustain Dev. 2(10):77–84.

- LeMay S, Coleman J, McMahon D. 2012. Moral foundation theory and marketing. J Appl Mark Theory. 3(2):3.

- Liao CY. 2018. The world’s trend of farm animal welfare and Taiwan’s current situation. [accessed 2022 July 15]. https://animal.coa.gov.tw/download/economic/economical_02.pdf.

- Martinez LF, Jaeger DS. 2016. Ethical decision making in counterfeit purchase situations: the influence of moral awareness and moral emotions on moral judgment and purchase intentions. J Consum Market. 33(3):213–223. doi:10.1108/JCM-04-2015-1394.

- National Development Council. 2018-2021. Important population indicators. [accessed 2021 October 22]. https://pop-proj.ndc.gov.tw/dataSearch.aspx?uid = 3109&pid = 59.

- Olsen NV, Sijtsema SJ, Hall G. 2010. Predicting consumers’ intention to consume ready-to-eat meals. The role of moral attitude. Appetite. 55(3):534–539. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2010.08.016.

- Qin W, Brown JL. 2008. Factors explaining male/female differences in attitudes and purchase intention toward genetically engineered salmon. J Consum Behav Int Res Rev. 7(2):127–145.

- Rest JR. 1979. Development in judging moral issues. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Rodenburg TB, Tuyttens FAM, de Reu K, Herman L, Zoons J, Sonck B. 2008. Welfare assessment of laying hens in furnished cages and non-cage systems: an on-farm comparison. Anim Welfare. 17(4):363–373. doi:10.1017/S096272860002786X.

- Schwepker CH, Ingram TN. 1996. Improving sales performance through ethics: the relationship between salesperson moral judgment and job performance. J Bus Ethics. 15:1151–1160. doi:10.1007/BF00412814.

- Shaouf A, Lü K, Li X. 2016. The effect of web advertising visual design on online purchase intention: an examination across gender. Comput Human Behav. 60:622–634. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2016.02.090.

- Singhapakdi A, Vitell SJ, Kraft KL. 1996. Moral intensity and ethical decision-making of marketing professionals. J Bus Res. 36(3):245–255. doi:10.1016/0148-2963(95)00155-7.

- Su B, Martens P. 2017. Public attitudes toward animals and the influential factors in contemporary China. Anim Welfare. 26(2):239–247. doi:10.7120/09627286.26.2.239.

- Sumner DA, Gow H, Hayes D, Matthews W, Norwood B, Rosen-Molina JT, Thurman W. 2011. Economic and market issues on the sustainability of egg production in the United States: analysis of alternative production systems. Poult Sci. 90(1):241–250. doi:10.3382/ps.2010-00822.

- Tan B. 2002. Understanding consumer ethical decision making with respect to purchase of pirated software. Journal of Consumer Marketing. 19(2):96–111. doi:10.1108/07363760210420531.

- Teasley D. 2016. What is a moral decision? - Definition & examples. [accessed 2021 August 11]. https://study.com/academy/lesson/what-is-a-moral-decision-definition-examples-quiz.html.

- White K, MacDonnell R, Ellard JH. 2012. Belief in a just world: consumer intentions and behaviors toward ethical products. J Mark. 76(1):103–118. doi:10.1509/jm.09.0581.

- WOAH. 2022. Introduction to the recommendations for animal welfare. [accessed 2023 April 26]. https://www.woah.org/fileadmin/Home/eng/Health_standards/tahc/current/chapitre_aw_iintroductio.pdf.

- Yang YC. 2018. Factors affecting consumers’ willingness to pay for animal welfare eggs in Taiwan. Int Food Agribusiness Manag Rev. 21(6):741–754.