Abstract

Where agriculture relies heavily on physical labor, small-scale mechanization can reduce labor constraints and contribute to higher yields and food security. Then, how to explain weak demand articulation for and adoption of small-scale mechanization, despite high labor burden? This study examines how intra-household gender dynamics affect women’s articulation of demand for and adoption of laborsaving technologies in maize-based systems in Ethiopia and Kenya. Using gender as a relational concept, and differentiating between different types of households, the analysis pulls together key underlying dimensions that shape women’s demand-articulation for small-scale mechanization. First, women’s labor often go unrecognized, and women typically are expected to work hard and not voice their concerns. Second, women generally lack access to and control over a range of resources, including land, income, and extension services. Third, the gender division of labor exacerbates this as women’s time poverty negatively affects their access to resources and information. Finally, decisions are primarily seen as men's domain, and women are often excluded. Our study contributes to the literature by offering a conceptual approach and methodology for the analysis of gender dynamics in relation to demand articulation and adoption of laborsaving technologies.

Introduction

In large parts of the world, agriculture continues to rely heavily on the physical labor of men and women, and sometimes children. For many smallholders, affordable mechanization could greatly improve livelihoods by reducing labor constraints and contributing to higher yields, improved food security, and wellbeing (Sims & Kienzle, Citation2006). Adoption of agricultural technology is mediated by a complex interplay of technical, institutional, and socio-economic factors, of which gender is a key dimension (Ragasa, Citation2012). In this article, we focus on how gender norms and related intra-household dynamics shape women’s demand articulation for and adoption of laborsaving technologies in maize-based smallholder agriculture in Ethiopia and Kenya.

We draw on empirical data from diverse household categories in maize-based smallholder contexts in Ethiopia and Kenya, where both women and men play important roles in agriculture, and where women furthermore are responsible for reproductive work. Paradoxically, despite women’s high labor burden, there is low demand for and adoption of mechanization for tasks that affect women’s labor. How do we make sense of this? What factors influence women’s articulation of demand for and use of farm power mechanization? To answer this question, we examine the data from four analytical dimensions: a) gender division of labor; b) gender norms; c) gendered access to and control over resources, particularly land and income, and finally; d) intra-household decision-making. In the discussion, we show how the interactions between these four dimensions influence women’s demand for and use of mechanization.

The study was carried out in areas linked to the introduction of two-wheel tractors (2WTs) in Kenya and EthiopiaFootnote1, in order to strengthen the understanding of local gender dynamics in relation to the introduction of small-scale agricultural mechanization. While the focus of the research is on labor-saving mechanization in agriculture, a broader analysis of labor issues of productive as well as reproductive tasks is needed in order to establish their interconnectedness and how they affect what is happening in farming.

We open with a literature review on gender and laborsaving agricultural technology adoption in sub-Saharan Africa. After introducing the analytical framework guiding our study and presenting the study’s methods, we turn to the findings section. The discussion returns to the overall research question, reflects on the analytical framework, and considers implications for agricultural research and development.

Gender differences and adoption of laborsaving agricultural technologies

In many parts of the world, agriculture involves drudgery, much of which is experienced by women. New agricultural technology – including mechanized equipment – can be laborsaving. However, the relation between drudgery and demand for mechanization is not straightforward. Not only are there many barriers that affect actual adoption, but the technology itself can have both positive and negative impacts on (different) women and men in the same household (Doss, Citation2001; Meinzen-Dick et al., Citation2011; Orr et al., Citation2016; Singh et al., Citation2006; World Bank, Food and Agriculture Organization, International Fund for Agricultural Development, Citation2009).

Just as new technologies are likely to change labor allocation patterns in the household, the gender division of labor influences adoption and use of technology, especially mechanization (Doss, Citation2001; Ragasa, Citation2012; Theis et al., Citation2019). To understand what affects adoption of mechanized technologies, including whose labor might be saved; a key starting point is a gender analysis of who does what in farming, at different stages of the agricultural cycle, and in what capacity (owners, managers, decision-makers, etc.). Such analysis should also consider what labor is available to the household, and its individuals (Doss, Citation2001). Women’s access to labor, for instance, whether from within the household, from workgroups or from the market, is often curtailed by unequal gender relations.

The extensive body of knowledge devoted to the gendered technology adoption in agriculture does not cover all technologies equally. A review by Peterman et al. (Citation2014) concluded that very few empirically based household-level studies include mechanization and other farming equipment disaggregated by gender. While there is general agreement that the gender of the farmer affects the adoption of agricultural technologies, there is a lack of consensus on the extent and effects of gender differences in access to agricultural inputs (Peterman et al., Citation2014). This is explained by the lack of research systematically looking at whether women and men fundamentally differ in their adoption decisions (Ragasa, Citation2012). Doss (Citation2001) stresses the importance of understanding why women do not always adopt new technologies and suggest differentiating between non-adoption due to different preferences in relation to the specific technology, and adoption constraints faced by women and men differently.

Such constraints relate to access and control over resources. Reviewing empirical studies on gender and agricultural technology adoption, Ragasa (Citation2012) found that, compared to men, women have much slower observed rates of adoption of a wide range of technologies, mainly due to differentiated access to complementary inputs and services. Similarly, in data from 27 countries Croppenstedt et al. (Citation2013) observed significant gaps in male and female-headed households’ (FHH) use of mechanization, which were more severe for FHH lacking access to male labor. They found little evidence that these gaps are related to physical differences between women and men, to scale of land operations, or ‘thin markets’ (pp. 13–14), and conclude that the gaps ‘do not seem to systematically improve with economic growth, household wealth, or overall use of an input or resource in the country’ (p. 24). Indeed, access to education, information and agricultural extension, land, credit, and other resources are key for the use and adoption of new technologies and farming practices (Doss, Citation2001; Meinzen-Dick et al., Citation2014; Peterman et al., Citation2014).

The concern for access and control over resources also extends to outputs from agriculture and related benefits, for example as women farmers receive lower prices for produce than men, have limited access to markets, or lack control over the income from agricultural outputs (Meinzen-Dick et al., Citation2011; Njuki et al., Citation2014; Peterman et al., Citation2014). Who actually sells farming products, and what happens to the income generated in this way, are key questions. The risk of male capture of control over resources and benefits has been known to affect women’s adoption of agricultural technology negatively (Orr et al., Citation2016).

Gender norms, that is, the social rules that frame what is considered typical and appropriate for a woman and a man to be and do in their society, also shape gendered adoption and use of laborsaving agricultural technologies. In many regions, gender norms attach submissive and reproductive roles to women, and authority and productive roles to men. These normative frameworks profoundly shape how women and men perceive and act on opportunities in their lives, including their ability to take advantage of new agricultural livelihood opportunities (Badstue et al., Citation2017, Citation2018; Croppenstedt et al., Citation2013; Ragasa, Citation2012). In a study in Bangladesh, Theis et al. (Citation2019) show how women’s ability to engage with opportunities for mechanized rice and wheat reaper-harvesters, was limited by a normative taboo on women operating machines, by restrictive norms regarding women’s physical mobility and social interactions, and by normative expectations of women’s deference to male authority. In their study of agricultural mechanization and gendered labor dynamics in Northern Ghana, Kansanga et al. (Citation2019) explain how farmwomen’s honor and prestige are tied to normative expectations of hard work. From a study in East Africa, Njuki et al. (Citation2014) report that women’s use of treadle pumps was considered inappropriate, as it exposed the outline of operating women’s thighs (Quisumbing & Pandolfelli, Citation2010). Meanwhile, Pini (Citation2005) excellently analyses how stereotypes associated with femininity and masculinity influence how Australian farmwomen use, and talk about their use of, tractors.

Social norms also tend to become embedded in the ways institutions function at different levels. In their study from Northern Ghana, for instance, Kansanga et al. (Citation2019) conclude that smallholder mechanization interventions feed into an agricultural system entirely underpinned by longstanding unequal gendered power relations, where laborsaving mechanization is framed as a masculine domain with little opportunity for women to engage and benefit. To be sure, in agricultural research and development, the term ‘farmer’ is widely associated with men and this translates to extension systems systematically disadvantaging female farmers (Farnworth & Colverson, Citation2015). As Kingiri (Citation2010) argues in her review and discussion article, when unequal gender relations are taken for granted in farming systems research-and-development, interventions tend to benefit men more than women. In a study of agricultural extension workers in Pakistan, for instance, Lamontagne-Godwin et al. (Citation2019) show how male extension workers’ lack of awareness of gender-based realities of agricultural information access shaped the practice and modalities for extension provision in favor of men farmers. Petesch, Bullock et al. (Citation2018); Petesch, Feldman et al. (Citation2018) introduce the concept of local normative climate to analyze how gender norms shape women’s and men’s sense of agency and capacity to innovate. In another article, analyzing 79 community case studies across 19 countries, Petesch, Feldman et al. (Citation2018); Petesch, Bullock et al. (Citation2018) find that in communities featuring a more inclusive normative climate, women and men report higher levels of perceived agency and capacity to innovate, and higher levels of poverty reduction.

Research indicates that women’s interests and labor time are often valued less than men’s (Croppenstedt et al., Citation2013; Doss, Citation2001; Fischer et al., Citation2018; Kansanga et al., Citation2019). Similarly, Schwab and Hodjo (Citation2018) found that: ‘the higher the relative proportion of female labor used in a given activity, the lower the household willingness to pay for a hired service to replace the labor in that activity’ (p. 4). Technologies that reduce men’s labor time then can appear more profitable (Doss, Citation2001). A study of household decision-making related to mechanical rice transplanting (MRT) in India – a technology reducing labor in transplanting, primarily done by women – found that women value MRT more than men do (Gulati et al., Citation2019). However, overall household demand articulation exclusively reflects men's valuation of the technology, as women’s bargaining power is too limited to influence the adoption decision (Joshi et al., Citation2019).

People’s expectations of how a new technology will affect social relations, roles, and responsibilities also influence technology adoption (Doss, Citation2001; Peterman et al., Citation2014, Theis et al., Citation2019). Several authors emphasize that households do not act in a unitary manner when making decisions or allocating resources; and women and men within households do not always share preferences nor resources (Alderman et al., Citation1995; Doss Citation2014; Doss & Kieran, Citation2014; Joshi et al., Citation2019; Meinzen-Dick et al., Citation2011). Households have dimensions of both cooperation and conflict (Agarwal, Citation1997; Jackson, Citation2013; Sen, Citation1990), and intra-household decision-making is shaped by power relations and negotiation between household members. Yet, much research on adoption of agricultural and laborsaving technologies lacks analysis from a gender relations perspective (Doss, Citation2001; Ragasa, Citation2012).

Analytical framework

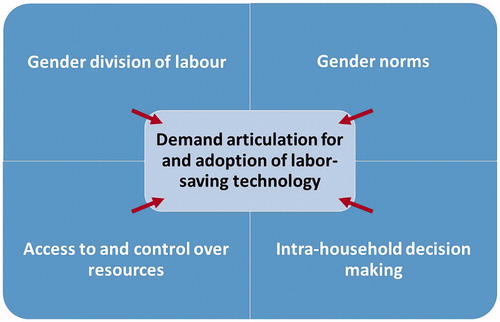

Our framework for analyzing women’s demand articulation and adoption of laborsaving technologies () brings together four important, interconnected dimensions of gender relations.

The first dimension, gender division of labor, calls for an analysis of productive and reproductive tasks, and community-related roles, by different male and female household members. It covers different stages of the farming cycle, from land preparation to post-harvesting.

The second dimension, gender norms, examines the recognition and value given to the labor of different household members. It also explores other social norms about women’s roles, constraints, and opportunities.

The third dimension focuses on access to and control over resources. The set of resources to be considered here is potentially broad, including ownership of and access to land, but also other productive resources like trees, plants, tools, and mechanized equipment or draft animals, as well as inputs such as seeds, fertilizers, water, fodder, credit, information, and extension. A key resource in terms of control is labor, both one’s own and the labor of others in or outside the household. Control over benefits and income is also important, as is access to groups and organizations.

The intra-household decision-making dimension is strongly related to control over resources and often concerns the latter. However, having or lacking control over resources, also directly influences a person’s decision-making and bargaining power. Thus, intra-household decision-making and control over resources merit separate consideration to illuminate how the latter affects actual decision-making processes and power relations. This study considers decision-making regarding acquisition or sale of assets, labor allocations, and income and benefits, related to and beyond agricultural production. The analysis considers who is involved in which decisions and how. The influence of dominant norms in decision-making, as well as how people seek to negotiate these are important aspects.

Materials and methods

Data collection

Qualitative field research took place in two sites in Ethiopia and two sites in Kenya, following a standardized data collection protocol with three methods: a) focus group discussions (FGDs) focusing on the household-level gender division of labor, b) semi-structured individual interviews (SSII) with questions pertaining to all four dimensions of the analytical framework, and c) key informant interviews (KIIs) on site-specific experiences with mechanization and existence of relevant organizations.

Gender dynamics manifest differently across household types (Doss & Kieran, Citation2014; Doss Citation2014). The study design therefore considered the most prevalent rural household types () in both countries: (1) male-headed households (MHHs); (2) FHH with access to male labor (FHHWAML); and (3) FHH without access to male labor (FHHWOML). To ensure adequate insight into intra-household relations, perspectives of diverse individuals within households were collected.

Table 1. Definitions of household types.

Study sites were purposively selected, focusing on communities i) where maize was commonly grown, ii) where all three types of households mentioned above could be found, and iii) where a certain level of women’s organization existed, e.g., through women’s groups, farmers’ organizations, or cooperatives. The latter was important in relation to access to new knowledge, technologies, resources, and markets.

In each location, one FGD was held with women representing the different household types, as well as different ages/life-cycle stages, and for polygamous households, different positions as wives. In Asella, four FGDs took place, as the two kebeles (wards) were too far apart to easily bring participants together in one location. Moreover, male relatives wanted to participate in the discussions.

The sampling for the SSIIs aimed for maximum variation across the three household types and included different individuals per household. In each community, members from four MHHs, two FHHWAML, and two FHHWOML were interviewed. Finally, to gain an overview of relevant entities, and of local experience with agricultural mechanization, three KIIs with government staff, extension officers, representatives of community-based organizations, NGOs or agricultural research institutes, and two KIIs with agricultural laborers, were conducted in each location. In total, 97 women and 54 men participated in the study. provides an overview of the total sample across the four sites.

Table 2. Overview of sample by instrument and study site.

Data analysis employed a grounded theory approach, building on the analytical framework as sensitizing concepts (Flick, Citation2009: 431, 100–101). Data were analyzed both by study site and across all four sites. Cross-case analysis was further enhanced by a participatory validation workshop with stakeholders in Addis Ababa.

The study sites

provides an overview of average household land size, the role of maize as food and cash crop, experience with 2- and 4-wheel tractors, and land ownership practices in the four study sites. Maize stover is widely used for fuel and fodder in all sites and draft animals, either owned or hired, are used in land preparation. In general, human muscle constitutes the most important source of power in all phases of the maize farming cycle, sometimes combined with animal traction. Four-wheel tractors (4WT) were not used in the Ethiopian sites and very few farmers had experience with 2WTs. In Bungoma, Kenya, some MHHs hire 4WTs, and in Laikipia, some farmers use 2WT or 4WT, primarily for land preparation, and sometimes for weeding. Across sites, women have less knowledge and experience with tractors than men. Land ownership practices vary considerably between sites and social norms greatly influence women’s control of and benefits from the land they farm.

Table 3. Summary of key site characteristics.

Results

Patterns of the gender division of labor in the study sites

Land preparation

Although women provide important contributions, land preparation is considered a man’s task in Ethiopia. In Asella, men plow with oxen, while women collect and dispose of rocks and other unwanted materials. In Hawassa, women from three MHHs and two FHH heads reported that they plowed the land themselves, because the men in their households were absent or had disengaged from agriculture. In the Kenyan sites, in HHs where men were present, land preparation was typically done by men, often with help from women, hired laborers, and/or animal or tractor power. Where men were absent, the women in the household did it. FHHWOML typically lacked resources to hire laborers or tractor service.

Planting, weeding, and harvesting

Across sites and household types, women provide major labor contributions during planting, weeding, and harvesting, often with support from other household members and, occasionally, hired laborers. In Hawassa, for example, study participants explained that some MHHs and FHHWAMLs hired agricultural laborers for harvesting, while FHHWOMLs did not and rather mobilized everybody in the HH, including children, for the harvest. In Asella, weeding and harvesting were sometimes done in labor groups (wonfel), in which case the women discharged the weeds from the field and transported the produce on their backs. If men participated in transport of produce, animal carts were often used.

Post-harvest processing and transport

Across sites and household types, women were responsible for shelling and grinding. Some MHHs in the Kenyan sites hired a mechanized grain sheller, or, if the wife of the male head was formally employed, laborers. In the Ethiopian sites, all household members were involved in threshing.

Selling

In Hawassa, the sale of maize in bulk was managed by men, and in FHHs, by the female head accompanied by a male relative. Wives in MHHs were also expected to generate income from smaller amounts of maize. In Asella, where maize was a minor crop, women could be in charge of its sale. In MHHs in Bungoma, Kenya, maize was sold by the wife of the household head, who then handed over the income received to her husband. In Laikipia, husband and wife may sell the produce jointly, or the male head alone would sell, while women in MHHs, who grew maize separately, marketed their own produce.

Reproductive work

In addition to their agricultural labor contributions, across sites and household types, respondents described women as responsible for all reproductive and household-related work, including child – and elder care, food preparation, washing, cleaning, and the collection of fuel, water, and fodder.

Women’s labor burden responses and effects

Overall, the farming activities that women considered as contributing most heavily to their labor burden included land preparation, weeding, harvesting and transport, and post-harvest processing. Daily reproductive activities were also considered highly labor intensive.

Across sites, the use of hired labor, animal draft power or, in the case of Kenya, tractor services, was much more common for MHHs than FHHs, and primarily for land preparation. Typically, women’s most burdensome tasks in the maize farming cycle were not addressed, nor were their reproductive responsibilities. FHHs had few options for reducing their labor burden due to limited financial resources. FHHWOML had the least options of all.

Across sites and household types, high labor intensity negatively affected women’s overall wellbeing and health in general, and their productivity and efficiency as maize farmers in particular. Reliance on the labor of household members seemed to affect women and girls disproportionally. Women in FHHWOML appeared to have the highest labor burden of all and therefore tended to be more affected.

Also, when mothers took over tasks from men, in particular land preparation, or became ill, girl children often had to take over the mothers’ work, especially the reproductive tasks. In the Ethiopian sites, interviewees mentioned that girl children had dropped out of school because of such responsibilities. In FHHs, high labor burdens also sometimes negatively affected the schooling of young men or boys.

Time poverty as a result of the gender division of labor

Across sites, women’s total work burden resulted in time poverty, which constrained their opportunities outside the house and farm, for example, for acquiring new knowledge or building up social capital. In all sites, fewer women than men had heard about or seen 2WTs. Focus group participants in Laikipia, for instance, referred to a ‘Farmer’s Field Day’ about mechanization, where out of 30 participants only one was a woman. Of the few women in the Ethiopian sites that did manage to participate in local group or cooperative meetings, no one recalled that (women’s) labor concerns were ever discussed.

Furthermore, study participants highlighted that time constraints limit opportunities to engage in other income-generating activities, which otherwise could give them access to resources to invest in reducing their agricultural labor burden. In Laikipia, for instance, young women described how their work burden prevented them from succeeding with small businesses. These combined effects further constrained women’s opportunities to voice their labor concerns and exacerbated the invisibility of their labor burden.

Gender norms

Women’s labor taken for granted

In all sites, women’s work often went unrecognized. When asked about needs for reducing the labor burden, interviewees commonly argued that women only play a supportive role in agriculture, while men do labor-intensive tasks and thus their labor burden needs reducing. In Hawassa, men and women alike considered women’s roles and responsibilities insignificant – even in the MHHs where women had taken over tillage and land preparation. The argument was that men still supervised the women, and this guidance was more important than the work itself. At the same time, women tended to belittle their own work, as this woman in a MHH said: ‘The work is too little, [women] are never busy - the work is too small to need labor reducing options’ (SSII).

The effects of this taken-for-grantedness varied for different women. In the Ethiopian sites, when extra labor was needed, girls were more likely to miss school than boys. In Hawassa, across all household types, study participants explained that low value was attached to investing in girls because they will marry and eventually serve another household. Meanwhile, daughters-in-law, especially in Bungoma, discussed being taken-for-granted and the many barriers stemming from their low status in the household.

Yet, participants in all sites recognized that households cannot function without women’s labor, as articulated by a member of the women’s FGD in Bungoma: ‘Women’s labor is very valuable…. without the presence of women households cannot function: there will be food insecurity and disorganization in the home; women take care of everyone in the household.’

Similarly, across household types in the Kenyan communities, different members, including men, agreed that women are indispensable, and expressed concerns about their high workload. The motives vary, however. Some male household heads said they feel neglected when their wives work long hours. Others worried about the effect of heavy work on their wives’ health, which might jeopardize their continued labor input into the farm and household. Women themselves wished for reduced labor burden so they could rest more, take better care of their household duties, attend meetings, and engage in other income-generating activities. In Asella, Ethiopia, both men and women acknowledged that women are overburdened, but, except for one woman from a MHH, nobody expressed any need to reduce women’s labor burden. In Asella, Bungoma, and Laikipia, both men and women recognized that demands on girls’ labor compromise their education.

Changing roles, changing norms?

Gender relations are not static. When men disengage from agriculture, women’s labor burden tend to increase. However, this does not immediately translate into women expressing interest in mechanization, due to social norms about good women being hard-working.

Nevertheless, when women take over what used to be men’s responsibilities, it challenges stereotypes about what women can or cannot do. In Ethiopia, study participants explained, women who plow were seen as dominant and wondila (manly). In Hawassa, women said now a girl’s ability to plow is an asset when she gets married. In Laikipia, Kenya, several women described taking part in plowing competitions with draft animals.

While women may take on tasks traditionally performed by men, men do not necessarily take on tasks traditionally performed by women. In Asella, women FGD participants reported that when asked to help with household tasks men often respond, ‘Do you think I am a woman?’ Critically, while men’s support can reduce women’s labor burden, it can also reduce women’s control of specific tasks in the farming cycle, which may act as a disincentive for women to adopt mechanized equipment.

Norms about voicing concerns and independence

Across sites there were strong norms about what is appropriate for women to do. In all sites, women interviewees and focus group participants talked about being expected to work hard and never sit idle. In Laikipia, for example, study participants explained how some women took on heavy labor burdens to live up to such norms, even when resources were available to invest in mechanized equipment. Likewise, in Bungoma, study participants described how a woman was considered a good wife if she did not employ other people to help her, because that would be a sign of laziness. Norms about women having to work hence undermined articulation of demand to reduce that labor burden.

Another norm limiting women’s space to articulate their demands was that women should not complain. In Ethiopian sites, women explained that society favors women who never whine or speak out loud. A woman interviewee from a MHH in Asella explained that if she were to use machines in her work, she would be labeled as a woman that ‘managed to have time to be idle.’ Similarly, other women in MHHs in Asella said laborsaving technologies could greatly help them, but were reluctant to raise this with their husbands, afraid to be considered lazy. This silencing of women’s realities reinforces the idea that women do not need laborsaving measures.

A less explicit, but influential norm supports the idea of women’s subordination to and dependency on men. Across sites, this manifested itself in negative attitudes toward women owning land, assets, and controlling money. A male household head in Asella argued, ‘However knowledgeable a woman may be, her idea will not be realized without the consent and action from the man’ (SSII). In all four sites, men and in-laws voiced resistance against women and daughters inheriting land. In Hawassa, widowed women faced pressure from in-laws to give up the land. In Bungoma, widows without sons directly inherited land, but in some cases, in-laws exerted pressure to make her give it up. Laikipia is the only site where, according to study participants, some families accepted daughters inheriting land from their fathers.

This dependence norm becomes most visible when it is challenged, for instance, when husbands oppose women accessing tractor power. In both Kenyan sites, male household heads prevented wives from hiring tractors with their own money. As a man in Bungoma explained: ‘How can a woman hire tractors? What does she want to show? I am the head of the household and no matter how much money she earns, it’s nothing and I cannot allow her to invest in big projects that will bring in more money to her pockets. I do not know what will happen, she might decide to abandon me and not to listen to me. A woman’s place is in the kitchen and in the home, even if she is working. No matter what it takes, women should always be reminded, so that they do not cross the line and try to do what men can do’ (male HH-head, SSII).

Women who defy gender norms experience resistance, repercussions, and stigmatization within their households, families, and the community. A woman interviewee from a MHH in Asella, who takes decisions jointly with her husband, shared that other men considered her a bad influence and did not want their wives associating with her. In Hawassa, women FGD participants talked about wives facing divorce for complaining too much about their work.

The man as the farmer

In all sites, men were considered the main farmers by FGD and KII participants. Women in MHHs in Asella were perceived as having a supportive role irrespective of how much agricultural work they do. In Hawassa, women were assumed to lack the knowledge to make the right decisions in agriculture, and several male household heads stressed the need to supervise wives’ agricultural work. It appears that social recognition of labor roles had not kept pace with changes in the gender division of labor.

The assumption, that the farmer is a man, makes women’s farm work invisible and denies the link between productive and reproductive work. This, in turn, influences service delivery to farmers. Across sites and household types, men, irrespective of whether they worked as farmers, obtained more knowledge about mechanization, than women did. Women were rarely targeted for trainings, and meanwhile the provision of knowledge to men further supported the assumption that farmers are men, thus reproducing male privileged control over knowledge and resources.

Access to and control over resources

Men controlled most assets in the households where they were present. Women mostly controlled small amounts of money, and few owned land and other assets. Still, there were differences within sites, and within and between household types.

Tractors were only observed in the Kenyan sites, and in most cases were hired by MHHs, with money from the sale of assets or formal employment. There were a few examples of wives of MHHs hiring tractors for their own fields, but only when they independently controlled land or income, for instance through formal employment.

The arrangements through which women access and/or control resources vary, and the extent to which they can articulate demand for mechanization and adopt laborsaving options, therefore, also varies. In MHHs, women generally controlled few assets, and this limited their ability to articulate demand for mechanization or other ways to reduce labor intensity. The limited resources women controlled did not enable them to adopt relatively expensive options independently. This was underlined by two examples of wives in MHHs in Asella, who paid for domestic help with their own small incomes.

In some FHHs resources were controlled by sons, living in the household or remotely. In other FHHs, women controlled assets and income, but the amount of resources was very low, undermining their ability to opt for more costly options, such as tractors. The death of a husband seriously affects the resource base and income of households, when the assets are divided among the heirs. Widows often found themselves with fewer resources to reduce the labor burden.

Decision-making in male-headed households

In MHHs, men were generally the ultimate decision-makers: they decided on the allocation of labor and on which part of the harvest to be sold or saved for household consumption. In Ethiopia, study participants related men’s decision-making to the expectation that women depend on men. The two Ethiopian communities differed in the level to which women in MHHs were involved in decision-making. In Hawassa, none of the four women in MHHs interviewed were consulted on household expenses and decisions made by the male head. In Asella, however, all FGD participants and three of the four wives in MHHs (SSII) said that men involve them in decisions on expenditures, although this appeared, to some extent, to be a matter of being informed.

The patterns of decision-making in MHH were more varied in the Kenyan sites according to both FDG and SSII participants. Sometimes decision-making was done jointly by husband and wife, in other cases it remained the exclusive domain of the MHH-head.

Joint decision-making is not equivalent to equal voice in decisions. Across the four sites, in MHHs that reported joint decision-making, major decisions on resources were made by men. This was well illustrated by a MHH-head in Bungoma: ‘How can my wife operate bank accounts? I am the sole owner of all bank accounts. If she needs money for anything, she should ask, and it is I who determine whether it is a worthy need or not. It is my money, so I control it. If a woman has a bank account, she will be big headed’ (SSII).

Male-dominated decision-making does not by definition mean that women’s interests, and labor burden, are not recognized by their husbands. In Bungoma, the decisions of some MHH-heads addressed women’s need to reduce their labor burden; some women also discussed their needs with their husband and tried to negotiate a positive response. However, in general the FGDs, KIIs, and individual interviews in Bungoma indicated that in most MHHs, decisions were not taken in favor of reducing women’s labor burden. The picture was similar for the other sites, such as in Hawassa where women’s weak bargaining position, combined with norms against women that ‘complain,’ even prevented women in MHHs from bringing up concerns about their high labor burden.

Game-change occurred when women controlled resources of their own, e.g., income from independent economic activity or formal employment, or land ownership. As a wife of the head in a MHH in Laikipia explained: ‘I bought my own piece of land and I plant maize on my own land, though my husband and I also have joint plots under maize. I make my own decisions on whether to hire tractors or not. This season I sold some of my goats and one cow and had enough money for hiring a tractor and animal drafts to reduce my labor burden. This way I can concentrate on my dairy cattle because they give me a good income. My husband cannot question my decisions because he knows once I get the money after selling maize, I use some for household needs, buy more assets for myself, and also, I have a separate savings account. … I have two daughters and one son in very good colleges, and I am the one paying for their tuition from the sale of maize from my individually owned plots. I am investing in my daughters because I want them to be better off than me in their married life and be independent instead of relying on their husbands for everything, because that can be very frustrating’ (SSII).

In addition to ensuring direct control and decision-making over resources, women’s independent ownership of land or income increased their bargaining power in the household. Direct resource control was the only way, in all four sites and across all household types, through which women could independently make decisions, including about investing in laborsaving arrangements.

In some cases, women’s increased control over resources was accompanied by tension within the household. In both Laikipia and Bungoma, wives in MHHs reported husbands intimidating them, being hostile, or obstructing their efforts to hire tractors, in order to maintain control. As one woman, whose husband tried to stop her from using tractors on her own land, explained: ‘I inherited land from my parents before marriage and over time, I have been growing maize on my own here in addition to joint maize farming on the piece of land that my husband owns. I have my own bank account and some dairy cattle, goats, and sheep. Instead of my husband appreciating that I am helping with the family responsibilities, he sometimes treats me with hostility and physically abuses me. I have reported him to the local administration. I take courage because I have my own money and assets’ (SSII).

Decision-making dynamics in female-headed households

Decision-making dynamics in FHHs were not universal either, with the main variation relating to the authority of male relatives, especially sons. The phenomenon of sons who lived elsewhere being the main HH decision-maker was only observed in the Ethiopian sites. That he did not contribute labor to the farming process, did not disqualify him from exercising decision-making authority. Some of the Ethiopian women described cutting ties with their sons, after giving them their share of the land, in order to gain control over their households. These women had not only lost part of the household resources, but also the social capital of their son’s knowledge and resources.

In other FFHWOMLs the female heads took decisions on their own, often because the resources in question were so small. One of them asked a man from the community to accompany her to the market to sell the little surplus she had.

In the Kenyan sites, the female head was the main decision maker, in both FHHWAML and FFHWOML. Sons in cities were able to provide their mothers advice or financial support but did not constrain women’s decision-making power as in the Ethiopian communities.

Discussion

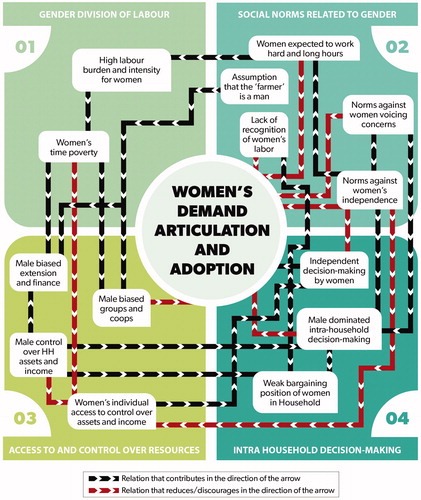

Overall, a combination of forces seems to work against women’s demand articulation and adoption of laborsaving technologies. As represented in below, this includes: a) Norms about good women working hard and long hours, combined with low recognition of women’s labor (quadrant 2); b) Norms against women voicing concerns about their individual wellbeing; and norms against women’s independence, including their owning and controlling resources (quadrant 2 affecting quadrants 3 and 4); c) A strong norm assuming farmers are men, which limits women’s access to extension, information, knowledge, and services (quadrant 2 affecting quadrant 3); d) Women’s time poverty constraining women’s possibilities to access services, information, and knowledge – as well as to generate income, or organize (quadrant 1 affecting quadrant 3); e) Women’s limited access to and control over resources, including: extension and information, land, income from farming, and social capital (quadrant 3); f) The fact that bargaining power of women and decision-making authority in households are not based on labor contributions (quadrant 1 interacting with quadrant 4), but rather on resource ownership and dominant gender norms reinforced by the low recognition of women’s labor and negative norms against their independence (quadrants 3 and 2 affecting quadrant 4).

illustrates how several of these elements interact across the four dimensions in our analytical framework to shape women’s demand for and adoption of laborsaving technologies. The diagram represents the complex background against which women and men seek to negotiate the complex interplay of labor, gender norms, access to and control over resources, and intra-household decision-making.

Where men disengage from agriculture, and norms about what is considered acceptable for women are changing, women’s labor burden often increases (quadrant 2 affecting quadrant 1). Yet, high labor burden of women does not automatically translate into demand articulation and adoption of mechanization (quadrant 1).

Women’s independent control over resources is a game changer. Adoption of mechanized farm power is practically only observed when women have direct and sole control over land and on- or off-farm income (quadrant 3 affecting quadrant 4). Women rarely articulate demand or adopt mechanization through joint decision-making with male relatives (quadrant 4). As findings indicate, independent decision-making by women on labor reduction and adoption of mechanization is often confronted with social disapproval and can come at the cost of losing social capital, both within the household and in the community (quadrant 4 interacting with quadrants 2 and 3).

To be sure, these dynamics play out differently across household types. Women in MHHs in the study communities generally have access to resources such as land and income through their husbands, but they typically have little control over these resources, which in turn undermines their ability to articulate demand and adopt labor-reducing options. In contrast, women in FHHs generally have higher levels of control over household resources, but their resources typically tend to be fewer and smaller compared to MHHs (quadrant 3).

The analytical model and findings explain why the labor burden does not automatically translate into the articulation of demand for and the adoption of options to reduce labor intensity. This is related to an underlying, complex interplay of assumptions, and social norms related to gender, access to and control over resources, and intra-household decision making. Factors in each of these dimensions negatively affect women’s ability to articulate demand for small-scale mechanization, as visualized in . Importantly, it is not only the influence of each of these separate dimensions and factors, but especially the way in which they interlock and reinforce each other, which undermine women’s opportunities to articulate demand and adopt mechanization technology or other options to reduce their labor burden. Insight into what is happening across these dimensions, for women and men in different types of households, is necessary to fully understand women’s weak demand articulation and adoption of small-scale mechanization, despite their high labor burden.

The findings, that women’s demand articulation and adoption of laborsaving technologies in the study sites are stimulated when women have control over resources and/or where more permissive or inclusive gender norms influence gender relations, resonate with existing literature on gender and agricultural technology adoption (Badstue et al., Citation2018; Croppenstedt et al., Citation2013; Doss, Citation2001; Meinzen-Dick et al., Citation2014; Petesch Feldman et al., Citation2018; Petesch, Bullock et al., Citation2018; Peterman et al., Citation2014; Ragasa, Citation2012). Moreover, our study contributes to this literature by offering a conceptual approach and methodology for the analysis of gender dynamics in relation to demand articulation and adoption of laborsaving technologies.

The findings furthermore demonstrate how gender dynamics are constantly negotiated (Farnworth et al., Citation2018; Locke et al., Citation2017), for example, when wives try to convince their husband to rent tractor services or a shelling machine; or when selling her surplus maize, a female household head asks a male neighbor to accompany her to the market. Whether supportive or antagonistic, men’s actions also contribute to this negotiation – often, but not always, in the form of asserting male authority, and in the worst case, by resorting to violence. Other times challenging local norms can mean losing social capital in the community or letting go of ties to adult sons. Though it concerned only a few women in the study, having direct control over resources drastically changes women’s power in decisions regarding use of laborsaving options. The observed changes in the gender division of labor, in gender norms, in access to and control over resources, and in decision-making, affirm that, even though gender relations are hegemonic, they are also unstable and dynamic (Petesch & Badstue, Citation2020; Budgeon, Citation2014).

This study was based on a qualitative research methodology that focused on illuminating the ways people process experience and manage or respond to their day-to-day situations (Miles et al., Citation2014). At the same time, however, the qualitative methodology and purposive sampling present limitations in the ability to generalize or extrapolate based on the results. Nevertheless, this study offers a series of findings, which, in a subsequent quantitative study, could be assessed in terms of validity for a larger population.

The implications of our findings call for the recognition of technological change as shaped by the complex interplay of gender norms, gendered access to and control over resources, and decision-making. Moreover, technological interventions also influence gender relations and dynamics. Our findings stress the importance of interventions engaging with access to and control over resources, and social norms related to gender, lest they are unlikely to have a structural impact on gender relations and women’s position. Furthermore, with the interlocking of the various dimensions in mind, our findings suggest that change in unequal gender relations require integrated approaches, acknowledging the interplay between factors, and dimensions. These acknowledgements challenge some of the assumptions of traditional technology-oriented interventions.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the women and men farmers who participated in this research and generously shared their time and experiences with us. The authors thank CIMMYT colleagues and research partners in Ethiopia and Kenya for useful interaction and support during research design and implementation. In addition, great thank you goes to Lara Roeven, Nancy Valtierra, George Williams, and Anya Umantseva for excellent support with literature reviews, graphics design, and editing.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no relevant or material financial interests that relate to the research described in this article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Lone Badstue

Lone Badstue (PhD) is the Research Theme Leader for Gender & Social Inclusion of the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT). She has 20+ years’ experience in pro-poor and gender sensitive development and research, especially in relation to agriculture and natural resources management in various countries in Latin America, Africa and South-Asia.

Anouka van Eerdewijk

Anouka van Eerdewijk (PhD) is senior advisor on gender equality and social justice at the Royal Tropical Institute (KIT, Netherlands). She has over 22 years of academic and professional experience in gender equality and women’s rights in international development, in a variety of sectors, including agriculture and natural resource management, mostly in sub-Sahara Africa.

Katrine Danielsen

Katrine Danielsen is a Senior Gender Advisor at KIT. Katrine has worked for 20+ years on gender equality, rights-based and transformative approaches in agriculture, natural resources management and responsible business conduct. She has extensive experience in Nepal, India, and Niger from previous positions with DANIDA, CARE Denmark and ILO.

Mahlet Hailemariam

Mahlet Hailemariam is a Gender & Development professional with broad experience in participatory methods in field research and applied development, including as a facilitator of Gender Action Learning and Community Conversation methodologies. Mahlet has vast experience from across Ethiopia, as well as other countries in East Africa working with a range of local and international organizations including the World Food Program, Gender at Work, KIT, as well as CIMMYT and other CGIAR centres.

Elizabeth Mukewa

Elizabeth Mukewa is a consultant and technical expert with over 12 years of experience in gender and social inclusion in relation to biodiversity conservation, agriculture, health and community development using multidisciplinary approaches to socioeconomic change. She has worked in several countries in sub-Saharan Africa and in the USA with different international development organizations, including GIZ, KfW, ILRI, Royal Tropical Institute, CIP, Partners for Women's Equality and Land O' lakes International Development Inc, and several regional and local partners.

Notes

1 The Farm Power and Conservation Agriculture for Sustainable Intensification project (FACASI) introduced two-wheel tractors (2WTs) in Kenya and Ethiopia. 2WTs can be used for tilling and related tasks and can also run milling and transportation equipment, etc., thus reducing labor peaks and drudgery in the post-harvest stage (Baudron et al., Citation2015).

References

- Agarwal, B. (1997). Bargaining and gender relations: Within and beyond the household. Feminist Economics, 3(1), 1–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/135457097338799

- Alderman, H., Chiappori, P. A., Haddad, L., Hoddinott, J., & Kanbur, R. (1995). Unitary versus collective models of the household: Is it time to shift the burden of proof? The World Bank Research Observer, 10(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/10.1.1

- Badstue, L. B., Lopez, D. E., Umantseva, A., Williams, G., Elias, M., Farnworth, C. R., Rietveld, A., Njuguna-Mungai, E., Luis, J., Najjar, D., & Kandiwa, V. (2018). What drives capacity to innovate? Insights from women and men small-scale farmers in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Journal of Gender, Agriculture and Food Security, 3(1), 54–81. https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.293588

- Badstue, L., Petesch, P., Williams, G., Umantseva, A., & Moctezuma, D. (2017). Gender and innovation processes in wheat-based systems. GENNOVATE Report to the CGIAR research program on wheat. International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center, CIMMYT.

- Baudron, F., Sims, B., Justice, S., Kahan, D. G., Rose, R., Mkomwa, S., Kaumbutho, P., Sariah, J., Nazare, R., Moges, G., & Gérard, B. (2015). Re-examining appropriate mechanization in Eastern and Southern Africa: Two-wheel tractors, conservation agriculture, and private sector involvement. Food Security, 7(4), 889–904. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-015-0476-3

- Budgeon, S. (2014). The dynamics of gender hegemony: Femininities, masculinities and social change. Sociology, 48(2), 317–334. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038513490358

- Croppenstedt, A., Goldstein, M., & Rosas, N. (2013). Gender and agriculture: Inefficiencies, segregation, and low productivity traps (pp. 1–31). The World Bank Research Observer.

- Doss, C., & Kieran, C. (2014). Standards for collecting sex-disaggregated data for gender analysis: A guide for CGIAR researchers. CGIAR Research Program on Policies, Institutions and Markets. https://hdl.handle.net/10947/3072

- Doss, C. (2014). Data needs for gender analysis in agriculture. In: A. R. Quisumbing, R. Meinzen-Dick, T. L. Raney, A. Croppenstedt, J. A. Behrman, & A. Peterman, (Eds.), Gender in agriculture (pp. 55–68). Dordrecht: Springer.

- Doss, C. R. (2001). Designing agricultural technology for African women farmers: Lessons from 25 years of experience. World Development, 29(12), 2075–2092. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(01)00088-2

- Farnworth, C. R., & Colverson, K. E. (2015). Building a gender-transformative extension and advisory facilitation system in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Gender, Agriculture and Food Security, 1, 20–39. https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.246040

- Farnworth, C. R., López, D. E., Badstue, L., Hailemariam, M., & Abeyo, B. G. (2018). Gender and agricultural innovation in Oromia region, Ethiopia: From innovator to tempered radical. Gender, Technology and Development, 22(3), 222–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/09718524.2018.1557315

- Fischer, G., Wittich, S., Malima, G., Sikumba, G., Lukuyu, B., Ngunga, D., & Rugalabam, J. (2018). Gender and mechanization: Exploring the sustainability of mechanized forage chopping in Tanzania. Journal of Rural Studies, 64, 112–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2018.09.012

- Flick, U. (2009). An introduction to qualitative research. SAGE.

- Gulati, K., Ward, P. S., Lybbert, T. J., & Spielman, D. J. (2019). Intrahousehold valuation, preference heterogeneity, and demand for an agricultural technology in India. Presented at the Future of Work in Agriculture Conference, World Bank.

- Jackson, C. (2013). Cooperative conflicts and gender relations: Experiential evidence from Southeast Uganda. Feminist Economics, 19(4), 25–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2013.827797

- Joshi, P. K., Khan, M. T., & Kishore, A. (2019). Heterogeneity in male and female farmers’ preference for a profit‐enhancing and labor‐saving technology: The case of Direct‐Seeded Rice (DSR) in India. Canadian Journal of Agricultural Economics/Revue Canadienne D'agroeconomie, 67(3), 303–320. https://doi.org/10.1111/cjag.12205

- Kansanga, M. M., Antabe, R., Sano, Y., Mason-Renton, S., & Luginaah, I. (2019). A feminist political ecology of agricultural mechanization and evolving gendered on-farm labor dynamics in northern Ghana. Gender, Technology and Development, 23(3), 207–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/09718524.2019.1687799

- Kingiri, A. (2010). Gender and agricultural innovation – revisiting the debate through an innovations systems perspective. Discussion Paper 06, Research Into Use Programme, RIU.

- Lamontagne-Godwin, J., Cardey, S., Williams, F. E., Dorward, P. T., Aslam, N., & Almas, M. (2019). Identifying gender-responsive approaches in rural advisory services that contribute to the institutionalisation of gender in Pakistan. The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension, 25(3), 267–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2019.1604392

- Locke, C., Muljono, P., McDougall, C., & Morgan, M. (2017). Innovation and gendered negotiations: Insights from six small‐scale fishing communities. Fish and Fisheries, 18(5), 943–957. https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12216

- Meinzen-Dick, R., Johnson, N., Quisumbing, A. R., Njuki, J., Behrman, J. A., Rubin, D., Peterman, A., & Waithanji, E. (2014). The gender asset gap and its implications for agricultural and rural development. In: A. R. Quisumbing, R. Meinzen-Dick, T. L. Raney, A. Croppenstedt, J. A. Behrman & A. Peterman (Eds.), Gender in agriculture: Closing the knowledge gap (pp. 91–115). Springer.

- Meinzen-Dick, R., Quisumbing, A., Behrman, J., Biermayr-Jenzano, P., Wilde, V., Noordeloos, M., Ragasa, C., & Beintema, N. (2011). Engendering agricultural research, development, and extension. International Food Policy Research Institute, IFPRI.

- Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña, J.(2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications.

- Njuki, J., Waithanji, E., Sakwa, B., Kariuki, J., Mukewa, E., & Ngige, J. (2014). A qualitative assessment of gender and irrigation technology in Kenya and Tanzania. Gender, Technology and Development, 18(3), 303–340.https://doi.org/10.1177/0971852414544010

- Orr, A., Tsusaka, T., Homann Kee ‐Tui, S., & Msere, H. (2016). What do we mean by ‘women's crops'? Commercialisation, gender and the power to name. Journal of International Development, 28(6), 919–937. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.3224

- Peterman, A., Behrman, J. A., & Quisumbing, A. R. (2014). A review of empirical evidence on gender differences in nonland agricultural inputs, technology, and services in developing countries. In A. R. Quisumbing, R. Meinzen-Dick, T. L. Raney, A. Croppenstedt, J. A. Behrman & A. Peterman (Eds.), Gender in agriculture: Closing the knowledge gap (pp. 145–186). Springer.

- Petesch, P., & Badstue, L. (2020). Gender norms and poverty dynamics in 32 villages of South Asia. International Journal of Community Well-Being, 3(3), 289–310. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42413-019-00047-5

- Petesch, P., Bullock, R., Feldman, S., Badstue, L., Rietveld, A., Bauchspies, W., Kamanzi, A., Tegbaru, A., & Yila, J. (2018). Local normative climate shaping agency and agricultural livelihoods in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Gender, Agriculture and Food Security, 3(1), 108–130.https://doi.org/10.19268/JGAFS.312018.5

- Petesch, P., Feldman, S., Elias, M., Badstue, L., Najjar, D., Rietveld, A., Bullock, R., Kawarazuka, N., & Luis, J. (2018). Community tipping points: The more equitable normative climate enabling rapid and inclusive agricultural development. Journal of Gender, Agriculture and Food Security, 3(1), 131–157.

- Pini, B. (2005). Farm women: Driving tractors and negotiating gender. International Journal of Sociology of Agriculture and Food, 13(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/0971852414544010

- Quisumbing, A., & Pandolfelli, L. (2010). Promising approaches to address the needs of poor female farmers: Resources, constraints, and interventions. World Development, 38(4), 581–592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2009.10.006

- Ragasa, C. (2012). Gender and institutional dimensions of agricultural technology adoption: A review of literature and synthesis of 35 case studies. Selected poster prepared for presentation at the International Association of Agricultural Economists (IAAE) Triennial Conference, Faz do Iguaçu, Brazil.

- Schwab, B., & Hodjo, M. (2018). Who has the time? Gender, labor and willingness to pay for mechanized technology in Bangladesh and Ethiopia. Presented at 2018 Agricultural and Applied Economics Association Annual Meeting.

- Sen, A. (1990). Gender and cooperative conflicts. In: I. Tinker (Ed.), Persistent inequalities: Women and world development (pp. 123–149). Oxford University Press.

- Sims, B., & Kienzle, J. (2006). Farm power and mechanization for small farms in sub-Saharan Africa (Technical report). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, FAO.

- Singh, S. P., Gite, L. P. J., & Agarwal, N. (2006). Improved farm tools and equipment for women workers for increased productivity and reduced drudgery. Gender, Technology and Development, 10(2), 229–244. https://doi.org/10.1177/097185240601000204

- Theis, S., Krupnik, T. J., Sultana, N., Rahman, S. U., Seymour, G., & Abedin, N. (2019). Gender and agricultural mechanization: A mixed-methods exploration of the impacts of multi-crop reaper-harvester service provision in Bangladesh. IFPRI Discussion Paper 01837. International Food Policy Research Institute, IFPRI.

- World Bank, Food and Agriculture Organization, International Fund for Agricultural Development. (2009). Gender in agriculture sourcebook. World Bank.