?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This paper unpacks the complex relationship between migration of men and the decision making power of the women who “stay behind” in Bihar, Eastern India. We use mixed methods research design to assess whether women perceive a shift in decision making “authority” between different members in households where men migrate and examine the subjective meanings of these shifts. Using a retrospective survey, we map the extent to which women report shifts in decision making “authority” after the migration of male members. Decision making is examined for various activities classified into four domains: agricultural practices, labor allocation, machinery and purchase of productive assets, and household expenditure and activities. Overall, patterns indicate a nominal change in the proportional distribution of perceived household decision authority for all categories and shift toward joint decision making (by wife and husband) emerging as an important trajectory. Using multinomial regression and interpretative analysis of qualitative findings, the paper sheds light on the role of age, family type, household and migrant characteristics in shaping the direction of shifts, and limiting the transfer of meaningful bargaining power to women. The paper makes a case that the transformation of the patriarchal habitus requires a more substantial transformation of livelihood capitals.

Introduction

Women’s increased agency has often been considered a proxy for empowerment in development practice. Increased decision making authority of women over their lives and influence over household decisions is seen as a desirable goal given its relationship with other important reproductive, health, and nutrition outcomes (Acosta et al., Citation2019; Alkire et al., Citation2013). Decision making capacities are also indicative of their ability to innovate in agriculture and respond to social and economic changes (Locke et al., Citation2017).

In recent times, decision making in multi-local or migrant households has captured the interest of social scientists. Besides proactive development interventions, women’s influence and control over decision making is impacted by structural changes within the family itself (Rashid, Citation2013). These changes include those engendered within the family life cycle like the death of family members and marriage, but also livelihood pathways or trajectories like migration of members which restructure family living arrangements (Desai & Banerji, Citation2008).

Migration and multi-local livelihoods in particular change household structures in tangible and intangible ways, while on the other hand, household structures are themselves important factors that trigger migration. de Haan and Zoomers (Citation2005) point out that multi-local livelihoods diminish coherent decision making in households. Household structures are altered when migration of family members triggers reconfiguration of responsibilities for domestic labor, care and, agricultural and livelihood activities.

Male out-migration in particular is often posited as an opportunity for women to take on roles and responsibilities that were previously taken up by men (Paris et al., Citation2005). Some studies have indicated positive effects of the absence of male members on the “empowerment” of women. Predominantly quantitative studies demonstrate that women tend to often gain “authority” within the household in such a situation. Fakir and Abedin (Citation2021) ascertain that women “left behind” in Bangladesh have significantly greater financial autonomy in comparison to their counterparts in non-migrant households. The authors also show that women are more likely to own assets (jointly or fully) compared to the non-migrant controls. Hadi (Citation2001) and Gulati (Citation1993) make similar arguments on the possibility of improved decision making outcomes based on evidence in India. These early findings ushered an academic interest in impact of migration on decision making structures in the household. More recent studies in Mozambique (Yabiku et al., Citation2010) and Bangladesh (Luna & Rahman, Citation2019; Singh, Citation2019) point to similar effects of migration on the autonomy of left-behind wives. However, there is relatively more research pointing to mixed evidence on the impact on female autonomy. Evidence suggests that male migration draws upon traditional kinship structures and patriarchy to continue the status quo, pushing wives further back into the extended family (Sinha et al., Citation2012). Some others have also resounded this argument asserting that there is no necessary correlation between men migrating and improved decision making capacities of women (Pattnaik, Citation2017). There are other studies giving more complicated, contextual and less optimistic conclusions on the effects of male migration on the decision making status of women in households depending on the presence of other household members and the family arrangements (Desai & Banerji, Citation2008).

Using new conceptual framework to situate gendered decision making within migrant households

The impact of male migration particularly on decision making has been an important analytical theme in migration studies in South Asia. However, an underlying issue in these studies is the lack of a clear definition of “decision making” and its theoretical framing, often conflating decision making authority with influence, autonomy, and bargaining power and using these terms interchangeably without a nuanced explanation of what they constitute. Decision making has often been a significant component of research on “empowerment,” even conflated with the term in some studies (Debnath & Selim, Citation2009; Singh et al., Citation2011). The evidence on whether decision making roles, authority, influence, and powers shift with male migration is thus inconclusive at best, partly because of inadequate conceptualization and inconsistent use of indicators. Few other studies have deployed a more interpretative lens exploring the subjective meanings of shifting decision making actions in the household for different members (Acosta et al., Citation2019; Farnworth et al., Citation2021). These situated decisions in the context of agricultural livelihoods in vulnerable ecologies, helping interpret the apparent and hidden meanings of such decision making actions (or non-actions) and its implications for agricultural innovation.

We use an extended form of sustainable livelihoods approach with a critical addition of Pierre Bourdieu’s (Citation1977) concept of habitus to understand decision making shifts in households as male members migrate. Habitus shapes and is itself shaped by perceptions and worldviews that the person internalizes according to their position in an unequal, hierarchical social field. It is a relatively durable generative structure of norms consisting of ideas and worldviews, taken for granted or unquestioned truths of social life (“doxa”) internalized by individuals over time due to social conditioning. The framework situates decision making actions of different members as a key trajectory of the household’s social practice that emerges from the “habitus” of its members. The idea of habitus closely aligns with the thought that there are limits to one’s actions and thoughts often shaped by their position in a hierarchical social field (Bourdieu, Citation1977; Farnworth et al., Citation2021).

Using Bourdieu’s habitus to understand the extent to which women or even men are able and willing to change their decision making roles in the backdrop of migration is the core of the framework. The concept is useful in envisaging agricultural livelihoods as a multi-local social field where livelihood trajectories of individuals are played out. These trajectories are limited by one’s position in the class-power-status inequalities. As such class-power-status embody the individual’s accumulation of physical, natural, cultural, social, and economic capital. One’s habitus reproduces social norms and rules (be it caste, gender, and age) that perpetuate inequalities in class-power-status and thus the access and ownership to different forms of capital forming the objective limits within which one can change their own habitus.

However, some livelihood trajectories such as migration offer opportunities for both men and women to negotiate and improvise and act upon the habitus. While complete autonomy from one’s habitus is rarely possible (unless a radical uprooting of hierarchies), livelihood trajectories, including multi-local trajectories of male migration can offer an opportunity for men and women to renegotiate the limits of their decision making actions. Farnworth et al. (Citation2021) argue that “different forms of patriarchy, specific to time and place, present women with distinct ‘rules of the game’ and call for different strategies to maximize security and optimize life options with varying potential for active or passive resistance in the face of oppression” (Farnworth et al., Citation2021). The subtle mutations women and men make to their own habitus are potentially driven by the household’s aspirations to diversify livelihood options through migration and interlinked actions of other members of the household including shifts in decision making on labor and resource allocation. The key question however is to determine the extent to which out-migration of male members enables these shifts.

We define decision making actions as a composite of decision making authority and influence. We opt for a social relational approach where decision making is a multiphasic phenomenon with minute negotiations involving different household members, occurring at various levels of the process rather than a final decision by an authority. Improvements in the negotiating abilities of different family members can be reflected both through authority, a more objective and visible form, and influence, a more invisible form. Authority may largely reflect on the final decision making actions by answering the question of “who,” while influence may refer to the inner workings of the “how” decisions are made and the circumstances and meanings of the decisions. We use an interpretative approach that highlights circumstances in which family members, women and men, make farm and household decisions. Decision making actions are seen as forms of social practice and trajectories that are derived from the habitus. This is often shaped by social conditioning and reflecting embodied role expectations determined by social groups yet providing space for innovation and negotiations that can allow for a gradual change in cognitive structures and decision making perceptions over time.

In this paper, we examine whether male migration as a livelihood trajectory enables other decision making trajectories for household members including women. We determine if these trajectories open up opportunities for women to ever so slightly improvise and innovate within the habitus or even challenge it. We take these concepts to build a case for a more socially grounded understanding of decision making shifts, or the lack thereof, that occur on account of male out-migration in the context of Bihar in eastern India. Most decision making studies are restricted to a few decisions or decision making contexts. However, allocation of decision making “authority” varies for different decisions taken by the household. We add to the literature by examining a range of situations. Additionally, migration studies usually rely on cross-sectional data, but we use retrospective data to compare the perceptions of change in decision making authority before and after migration to mitigate the issue of confounding variables.

The following section describes the methodology. This is followed by a discussion of the results of the shifting gendered decision making dynamics, and an examination of the direction and extent of shifts for four different decision domains and a discussion of factors influencing intra-household shifts in decision making authority. The observations from the quantitative analysis are followed by a discussion of these patterns in the light of qualitative data. We map five key trajectories in the direction of shifts in decision making in migrant households. The paper concludes by drawing out the implications of these shifts for development practice and policy.

Methodology

This article is based on data that was collected between October 2019 and November 2019 in three districts, namely, (i) Gaya, (ii) Darbhanga, and (iii) Gopalganj in the Bihar State in eastern India. The sample selection consisted of the following steps: (1) sample districts were chosen to represent three different rice cultivating agro-ecologies experiencing floods and, floods and droughts and, geographical locations where migration rates are high; (2) 10 villages from the three districts were selected randomly; and (3) every fifth household from the village household list put together was randomly selected till the complete village was covered. Attempts were made to ensure that an equal number of migrant and non-migrant households were selected. A total of 528 households were thus selected from 3 districts and 10 villages for the quantitative survey. Within each sampled household, one woman respondent above 18 was identified (often spouses of heads). Of the 528 households, 235 (44.5%) were migrant households. Data from the sample households were collected using a structured questionnaire (Ram Mohan & Puskur, Citation2021).

Amongst the 235 migrant households, 210 households had women as the key respondent, in the other 25 households the visiting male migrant or other male household members were the key respondent. As this particular analysis focuses on the retrospective aspect of the survey, we included only the migrant households and data from the 210 households where women were key respondents (). While the overall sample for the quantitative survey is 528 households, this study synthesizes findings based on a sample of 210 participant households that were administered the retrospective module of the survey.

Table 1. Distribution of respondents included in the analysis.

The survey analysis examines women’s perspectives on shifts in decision making authority within migrant households and various household characteristics, respondent’s own attributes and migrant’s characteristics that influence them. These perspectives reflect women respondents’ attribution of bargaining power to self, and other male or women members of the family. The study uses a retrospective component in the survey questionnaire to pose questions on who in the household made decisions on specific aspects before and after migration.

Conceptually, the question probes on the perceived decision making authority of the household which captures only one dimension of the decision making, predominantly of authority but serves as a reasonable proxy for assessing the respondent’s perception of final decision making powers of different household members. Based on the observations, household decision making dynamics were classified into four categories: (a) husband dominated (clubbing observations where decision making authority is either the husband only or if husband dominated the final decision when there is a conflict when both husband and wife are involved in it), (b) joint decisions (respondent perceived that both contributed equally), (c) wife dominated (clubbing observations where decision making authority was either wife only or where wives dominated in case of conflict), or (d) other family members as decision making authorities (including other older, younger, men and women relatives in the household). Shift in decision refers to decision making shift from one person to another after migration. The change in decision making is categorized into five groups: (1) no shift in decision making, (2) shift to husband, (3) shift to joint, (4) shift to wife, and (5) shift to other household members. Shift from one category to another before and after migration was assessed and coded for each migrant household included in the analysis.

The survey captured observations for shifts for 21 decision making activities classified into four domains: (i) agricultural technology and practices, (ii) labor allocation decisions, (iii) machinery and purchase of productive assets, and (iv) household expenditure and activities (). The extent and nature of the involvement of members in household decision making processes and what each decision authority means in social practice is unpacked through qualitative data.

Table 2. Categorization of various decision domains.

Key informant interviews (KIIs) were conducted in all 10 sample villages with one key informant per village to understand the deeper socioeconomic structures and the vulnerability context within which migration is engendered and sustained. The key informant was the village head or a panchayat (local self-government) member. Out of the 10 key informants, 8 were men. KIIs were also used to document the shocks, agricultural transitions within the villages over the previous 10 years, the extent of reported migration in each context, the details of migration and other indicators like crops cultivated, type of land owned by different caste groups, irrigation, wages (men, women), and gender roles of men and women of different ages. Sources of vulnerability including extreme weather events like drought and flood, lack of resources to cope with those events, economic and political events and, epidemics were mapped at the community level.

Three focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted in three villages: Patori and Poaria in Darbangha and, Rani Chak in Gaya. Each FGD included eight women participants. Eighteen in depth interviews (IDIs) were conducted with seven women from Gaya, five from Darbhanga, and six from Gopalganj from migrant households and a mix of nuclear and joint families. IDI and FGD participants were chosen from the survey sample randomly.

An interactive visual group discussion tool to capture and identify changes in power relations typically in a household or community was tested. The tool gathers information about “typical” migration patterns in the village, characteristics of the migrant, common patterns of shifting gender dynamics in migrant households by enabling a discussion on changing roles, decision making influence of members, going beyond the decision making authority questions in the survey tool (Ram Mohan and Puskur, Citation2021). Interestingly, testing the tool highlighted that migrant experiences were diverse given the heterogeneity of age, economic, and migration context. Thus, the tool was also extended to individual IDIs for a more interactive discussion, while capturing specific situations of their households. The total sample size of the study including respondents for all quantitative and qualitative components of the study was 588.

The International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) Research Ethics Committee reviewed and approved the research protocols with the approval bearing the Reference No. 2019-0016-A-2018-140. Informed consent was obtained from all study respondents including qualitative and quantitative methods and protocols.

Multinomial logit regression was used to estimate the factors influencing the shifts in primary decision on agriculture, labor, machinery, and investment and household activities. The multinomial logit (MNL) model is a popular choice model in multiple adoption studies because it allows for the examination of decisions across more than two categories (Wooldridge, Citation2002). Another advantage of utilizing an MNL model is its computational ease in determining decision probabilities that may be expressed analytically. In the context of this study, our experiences as exemplified in the qualitative component of this paper, explain in detail that decision making is embedded within everyday negotiations, is often nonlinear and as such cannot be taken away from the specific dynamics and structure of the household. We also show in our qualitative study that women often conflate decision making with “burdens,” which itself makes it challenging to order and assign hierarchies to the shifts in terms of assigning ascending levels of “empowerment” or “autonomy” from 0 (no shift) to shift to wife (3), so as to say that decision making shift to women is a higher form of empowerment or autonomy (or for that matter joint decisions are less empowering that wife only). As such responses from the field indicate that decision making is a different construct and cannot be confounded with empowerment. Thus, in order to keep our analysis closer to social realities, free of value judgments and inherent hierarchies we select a multinomial regression model where we consider that shifts are not necessarily ordered on impinge on each other.

The response (dependent) variable contains five main groups of change in decision making. As a result, we define an MNL model (discrete choice method) in the following manner:

(1)

(1)

where

is the dependent variable representing changes in household decision making and takes the values of 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 if no change in decision, decision shift to husband, decision shift to joint, decision shift to wife, and decision shift to other members, respectively. One amongst the five decision types is designated as the reference category

The probability of the other four decision types is compared to the probability of the reference category decision type no change in decision.

represents a vector of explanatory variables that include socioeconomic characteristics and migration related variables that affect decision making.

represents the coefficients to be estimated. The results of the MNL model are interpreted in terms of the odds ratios, that is, the ratios of the probability of choosing one outcome category over the reference category.

An ordinal regression model was also used to check if the results differ from the multinomial logit analysis. The dependent variable using the ordinal regression model is discrete, ordered and expressed in terms of shift in decision ordinal categories. In this case, four categories were considered: no change in decision ( a shift in decision to the husband and others (

a shift in joint decision (

and a shift in decision to the wife (

Following Liao (Citation1994), the ordinal regression model takes the following form:

where

is the number of ordered categories defined above,

n is the number of independent variables;

independent variables;

is response variable;

respresents regression coefficients;

is composite term of the unknown threshold parameters separating the adjustment categories and the intercept (

).

A critical limitation of this study is that it does not capture longitudinal data, which is critical for observing changes over time. While perspectives of reported shifts in authority were recorded, decisions are often discrete negotiations that need to be observed through more experimental and situational interactions. Moreover, self-reported shifts over time, particularly in a retrospective survey may still entail under-reporting or over-reporting of influence or authority and conclusions may be interpreted in the light of the same.

Results and discussion

presents the basic demographic features of the sample respondents included in the analysis.

Table 3. Demographic characteristics of sample respondents.

About 87% of the women respondents were below the age of 50, with roughly half of them under 30 years of age. While about 50% of the respondents were non-literate, 38% attended secondary school. A large majority (91%) were Hindu, with 46.2% of them belonging to Scheduled Caste (SC), followed by 41% other Backward Castes. Sixty-one percent of the households were below the poverty line and the average land holding size was 0.17 ha. The average household size was five and 52.4% of the women lived in joint families. While in the context of this study migration refers to any household member staying outside at least three months, the average duration of migration in the respondent households was about six months.

Vulnerability and inequity context in the study locations

KIIs were critical in uncovering local caste structures and gender roles. On an average, majority of the land and irrigation resources belonged to Upper castes (Bhumihars) who were a social minority (except in one village), while OBCs ranked second with limited land ownership and access to irrigation resources like tube wells and borewells. Scheduled caste groups held the least resources and assets, often forming the major chunk of the landless population. In most villages, almost 35% to 40% of SCs were reported to be migrants. Women’s migration was reported to be marginal and restricted to women accompanying male migrants and working as household help in urban households. General or upper caste households reported highly skill-based migration. KIIs highlighted various climate stressors encountered in the region. Seven out of 10 villages were affected by either flood, drought or lowering of water table, or drought-like situation in addition to flood. Some villages in Darbhanga reported severe flooding, and destruction of paddy crops annually.

Shifting gendered decision making dynamics

Does perceived household decision making authority shift toward wife dominated or joint decision models after migration occurs in the household?

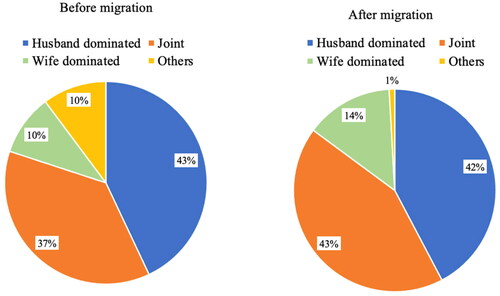

Results of the study answer this question in the affirmative, but indicate only marginal shifts. The overall trends indicated that there was nominal change in the proportional distribution of household decision authority for all categories in comparison to the pre-migration scenario. Firstly, we compare patterns of reported decision making authority before and after migration (). Almost 43% respondents reported husband dominated (or husband only) decisions for almost all activities before migration. While there was a substantial proportion of joint decisions (about 37.05%), there was very little decision making dominated by the wife or other family members. After migration, women respondents perceived that 38.48% of overall decisions were still husband dominated, 38.98% were perceived to be undertaken jointly and wife’s perceived authority was reported to be 12.74%. The perceived authority of other members decreased marginally to 9.80%. In terms of net change, while perceived authority of husband and other family members appeared to decrease, wife’s authority and joint authority over decision making appeared to increase.

Figure 1. Distribution of decision making authority before and after migration (percentage of total decisions).

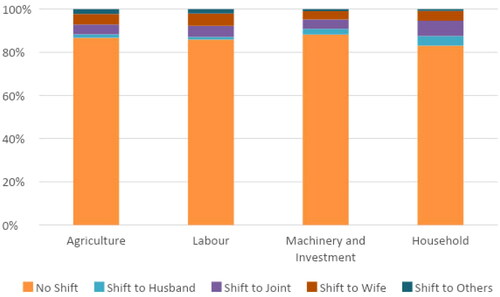

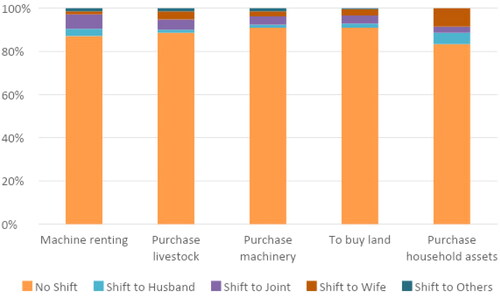

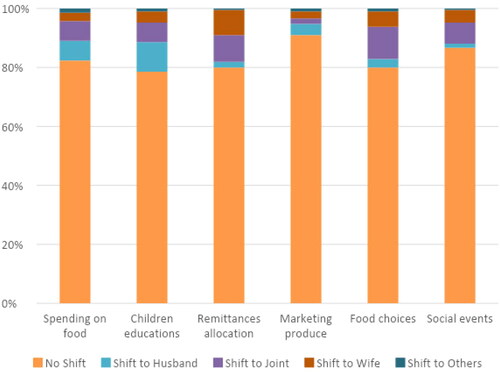

Disaggregating the overall shifts for the four major domains of decision making, the perceived shifts in the key decision maker in the household was seen to be least in the domains of machinery and productive resource allocation, which is a key economic and financial decision. Almost 88.19% of respondents indicated that decision making authority did not change after migration (). The maximum extent (16.90% of the respondents) of shifts are reported in case of recurring household expenditures. Shift to joint decision making was highest (7.06%) in this domain. Interestingly, shift to “wife as the dominant decision maker” was highest in case of labor allocation activities (4.83%). There were nominal shifts toward husband’s domination (in the household expenditures) as well as toward decision making authority of other family members in the domain of agriculture technologies and practices. Disaggregated results for each activity domain also reveal some interesting changes.

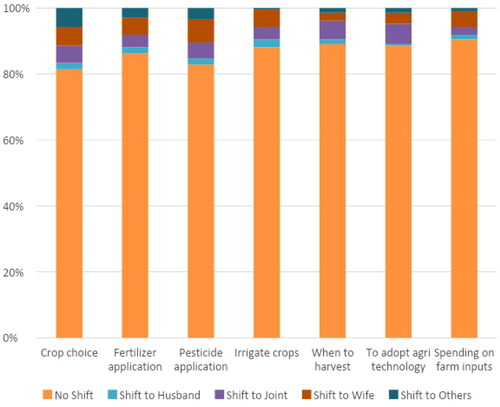

presents the perceived shifts in decision making authority regarding agricultural technology and practices. The most notable shift was in terms of crop choice with respondents attributing a shift in authority toward other family members and wife at 5.71% each. Pesticide application (7.14%) saw a greater shift toward wife’s authority, the on-farm operational decisions. In 88.57% of cases there were no perceived shifts in who decides on the adoption of agricultural technology (which was previously dominated by the husband). The smaller magnitude of changes in spending on farm inputs reiterated that control over expenditure on productive resources remained in the hands of the husband. The analysis showed two noteworthy patterns in decision making shifts with regard to machinery and investment in productive assets. The first, more notable shift of decision making authority toward wife, particularly on purchase of household assets and second, a marginal increase in joint decision making authority in machine renting decisions.Footnote1 The dominant pattern toward no shift in this domain, however, reinforces that gender norms continue to remain stringent on ownership and control over decisions on productive investments.

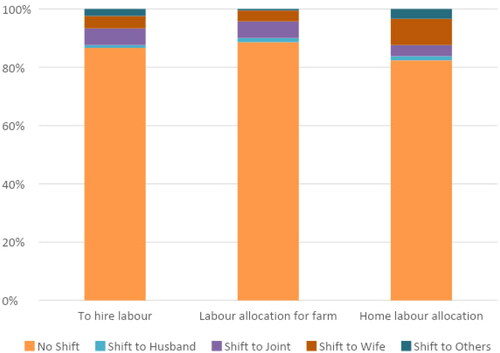

Women were seen to have greater say in allocating labor for tasks within the home (9.05%) and even in hiring farm labor after migration of male members (). The other notable shift was toward joint authority of the spouses over farm labor allocation. In household expenditure decisions, perceived shift toward wife’s authority was notable for remittance allocation (8.7%) and household food choices (5.24%).

The highest perceived shift in decision making with regard to investment activities happened in the purchase of household assets with the highest shift to wife followed, by the husband. The least shifts happened in purchase of machinery and land ().

The least shifts in decision making related to household activities happened in the areas of produce marketing and social events. The biggest shifts happened in decisions on children’s education, remittance allocation and food choices. The biggest shifts toward wife were in the domain of remittances allocation and household food choices ().

Factors influencing intra-household shifts in decision making authority

summarizes the key predictors of perceived decision making authority shifts for all decisions. Variables significantly and positively associated with the decision shift toward wife (as perceived by women respondents) from other members included number of months of annual migration by the male migrant member and whether the male head is a migrant or not. Households above poverty line had lower probability of shift toward wife’s decision making authority. Land size was also negatively and significantly associated with a shift toward wife dominated decision making. This is explained by evidence from KIIs that indicate that women from richer, land-owning, upper caste households were not involved in agriculture.

Table 4. Predictors of decision making shifts (All activities)*.

Interestingly, nuclear family and the age of respondent were significantly and negatively associated with a lower probability in shift toward wife’s domination in decision making. This is partially explained by the positive and significant association of shift toward higher joint authority with nuclear family and respondent’s age. Given the households’ exposure to vulnerabilities, it could reflect a conscious attempt on behalf of women respondents to take on lesser responsibilities or decision burdens on themselves alone. Simultaneously, as the women respondent’s age increases, the predicted probability of the husband’s domination as a decision making authority appears to lower, as does the authority of other household members. Together, this helps explain a preference toward joint decision making as an idealized model of decision making as the household cycle evolves into a nuclear family.

Respondent’s higher age, education status and literacy levels were negatively associated with a perceived shift toward husband domination in decision making authority (Scenario 2), indicating that increasing age and education of women respondents mattered in migrant household decisions.

Higher duration of migration annually by the household’s migrants was associated with an elevated probability of joint authority of husband and wife (Scenario 3) in decision making. Similarly, Hindu and BPL households were seen to be positively associated with a shift to joint authority.

Women respondent’s perception of decision making shifts toward other household members (Scenario 5) were influenced by family type (nuclear family was associated with shift toward others) and higher duration of migration annually was associated positively with the perceived shift toward other members. Interestingly, age of the respondent was associated positively and significantly with a shift toward authority of other family members.

Predicted shifts in agricultural decisions

For decisions on agriculture technology and practices, including crop choice, fertilizer application, pesticide application, crop irrigation, harvesting time, agricultural technology adoption, and farm inputs spending, respondent’s own characteristics had some influence on the probability of decision shifts, but household characteristics appeared to be more significant (). The increase in age of the woman respondent significantly lowers the predicted probability of a shift toward the husband’s authority in this domain (Scenario 2) but is positively associated with increasing authority of other family members (Scenario 5). It is likely that as respondent’s age increases, so could her strategic dependence upon the agricultural knowledge or support of other younger members like sons and daughters. The longer the duration of migration by the male member, more significant and positive is the likelihood of a shift toward the wife’s decision making authority in matters relating to agricultural technology. With households moving toward a nuclear family, predicted probability of shift toward joint authority increases but so does, interestingly, the declining probability of shift from the wife’s sole decision making authority. Gender dynamics are much more complex, considering respondent’s characteristics and household characteristics together contribute to perceived shifts in the bargaining power of different individuals. It is however safe to infer that the household’s shift toward joint authority is more likely given the circumstances within which household decision shifts are likely to occur. Dependence on a unitary decision maker model with either the husband or the wife dominating or autonomously taking decisions appears to be lesser and lesser. These circumstances include the low remittances, changing life cycle of the household toward nuclear family and precarity of the household’s livelihood. Moreover, as we will observe in the later sections, this pattern aligns with the dominant narrative projected of cooperative decision making in the household by respondents. The perceived shift toward joint authority by women over sole authority is an interesting finding that merits more discussion as a household resilience strategy.

Table 5. Predictors of decision making shifts (agricultural activities)*.

Predicted shifts in household decisions

The influence of household, migrant or respondent characteristics was lower in shifting the authority of different household members in case of household decisions (). The duration of migration in a year is significantly and positively associated with predicted probability of shift toward autonomous authority of the wife and joint decision making. Migration of the male head also elevates the probability of shift toward wife’s autonomous authority in household expenditure which includes among others, almost up to 5.5%. Household variables primarily explained the “no shift” scenario and the shift to husband scenario.

Table 6. Predictors of decision making shifts (household activities).

The maintenance of status quo whereas the higher number of months migrated positively influenced the shift toward joint decision making. Other variables had no effect on the shifts in investment decisions. The observations in the labor domain were few and inadequate for a regression analysis.

Two significant aspects emerge from this analysis. Firstly, it becomes clear that male migration does not necessarily transform decision making patterns in households, particularly on aspects of productive investments and some key farm level decisions. Secondly, even when it does, the shift is likely to be hinged on household conditions and human resources. The analysis broadly reveals limited decision making authority for women in joint family settings and a joint decision making ethic in nuclear households. In the next section we uncover the social logic that explains these patterns.

Unpacking decision making trajectories in social practice

The quantitative findings align with the larger conceptualization of persisting social structures and the dominant prevalence of patriarchal habitus that limits the migration effects on decision making authority toward the wife, but makes room for some improvization toward joint decision making. In this section, we systematically categorize and unpack the improvizations and social logic of pursuing various decision making trajectories across household situations and family life cycles experienced as a response to male migration. We identify five major trajectories. Our observations echo the findings of Farnworth et al. (Citation2021) who use a similar Bourdieusian approach in understanding strategies vis-à-vis decision making actions, albeit with a few differences.

Trajectory 1: sticking to the gender script: decision making in joint family households

With short-term (as one respondent puts: “kaam ka goi guarantee nahi”—there is no certainty of getting work at the migration destination) migration, household assets generally remained unchanged. This provided limited scope for expanding decision making authority or even influence of young married women in joint households over resources. A common response during interviews was that younger women in a joint family were not even aware how much land their husband or husband’s family owned, let alone participating in agricultural decisions.

Common community ideology (almost explained as a “natural” or “given”) espoused that young married women should avoid working on farms. Farm work by women was considered the result of the inability of male household members to provide (“no matter how poor we are, we won’t sully our bodies with mud”). In fact, sending young married women to work outside was even seen as a sign of destitution and lack of other options even among scheduled caste households. This largely exemplifies the strong internalization of “doxic” or naturalized belief (though primarily an upper caste practice) that young women must not engage in agricultural work unless they have no option, which reinforces an asymmetric access to information and resources within the household.

Male household heads acquire a very strong role in migrant households where they live with younger women members, including daughters-in-law and daughters. Elderly male members cited their authority over decision making, strongly centering it around their accountability for other younger household members and managing difficult situations the household faces especially when their migrant son is away. In narratives specific to agricultural decisions, male household heads drew on prevalent tradition to explain why women were not necessarily consulted when discussing agriculture.

Look, this is tradition. My mother, grandmother, and now my wife have never gone to the farm, till this date. They don’t know where it is and how much land we have… Physically I can still manage the work… I return from work to eat so my wife doesn’t even need to bring my food to me in the farm. (middle-aged man, SC, Darbhanga)

A similar worldview is also internalized by younger newly married women in joint families who were not involved in any agricultural decisions. A respondent in her early 20s mentioned the local tradition:

In our villages, women don’t go outside…only those who have attained a certain age go. When they are in their husband’s house they don’t go, but when they go back to their maternal home, then they help out a little on the farm. (21-year-old woman, OBC, Gopalganj)

As an intended strategy, this norm had a particular significance. Married women during initial years shoulder greater household responsibility including child care, cooking, and taking care of other older members of the household. This strategy may be interlinked with the heightened role of other family members. The idea of a “gaarjan” often the eldest member of the household, was significant during the interviews. The “gaarjan” was more of a figure (or figures) morally responsible for the left-behind members. Within joint families it was seen that migrants sent money directly to the bank accounts of the older male member (“papa ke khate mein”—to the father-in-law’s account) and the gaarjan’s role represented a more moral perception of authority that also combined a sense of financial responsibility and accountability. A respondent explains:

Tension should always be on the gaarjan, he (migrant son) should always be free (of tension). We tell him “son you keep earning” we take the responsibility of running the household here. Now how do we tell him that we had to spend money when the child is sick… we don’t give all that tension to our son. (middle-aged man, SC, Darbhanga)

These experiences also allude to the tactical significance of guardianship in a precarious economic situation. The elder members are also seen as playing an important role by taking responsibility for all activities back home and enabling the migrant to continue their work outside to serve the household’s larger economic interests. The lack of shift in authority toward younger women members in the presence of male out-migration may not be a sign of resistance to equality, but the cost or burden of taking up more decision making responsibility in a joint family with unstable economic situation may also be counter-productive and may not even serve the interests of women living in these joint families who are already tackling child rearing and other household responsibilities in the absence of men. Silent acquiescence was a decision making trajectory that women pursued given their limited choices within the bounds of their habitus (Farnworth et al., Citation2021). This is not, however, to say that women were completely unaware of their situation and most likely conformed to the ideal norms among the few choices available.

Where elderly male members were absent, a similar performance of age-based gender roles appeared to be enacted among older women heads in the household. Elderly women members are also prominent “guardians” (either alone or jointly with the husband) especially at the point in the family life cycle when they have new daughters-in-law, who are left by migrant members under their care. A discussion on why women did not migrate to cities with their husbands led to a respondent justifying why household heads assumed the responsibility of their daughters-in-law.

We are poor in terms of wealth not in terms of respect… the daughter’s dignity and respect is a household’s prerogative…That is why the household head is responsible for the daughter-in-law (when her husband is away), to keep tabs on her well-being and see to it she is taken care of, if she is sick, having a headache or pregnant… the complete responsibility is that of the household head. (middle-aged woman FGD participant, OBC, Gaya)

To some extent, when contrasted with experiences of respondents in nuclear families, the advantage of relinquishing authority to older family members comes into play, supporting an argument that silent acquiescence was more of a strategy in self-interest for women in joint migrant households. For instance, in this case where a respondent from a nuclear household was asked about changes in their roles and responsibilities:

Respondent: When we were a joint family… my in-laws took the decisions…

Interviewer: Who manages them now?

Respondent: Now, it is my “tension,” to this and that work.

(middle-aged woman, SC, Darbhanga)

Prioritizing livelihood security by optimizing decision making roles of different members, drawing from and reiterating social norms, tropes of masculinity of a paternalistic guardian figure show the strong limits posed by patriarchal-caste and age habitus, but also indicate how these trajectories represent a tactical response in light of the few options available to family members.

Trajectory 2: liminal gains in the margins of the habitus

Household expenditure decisions were the domain of action where women ever so slightly mutated their habitus. With respect to household expenditure decisions, even in joint families, there was some involvement of women in communicating their needs and being able to influence decisions. Explaining how household decisions are made an FGD participant elaborates:

Respondent: Whoever (in the family) goes to work outside, they earn money, send and say do this or invest it—whether it is for agriculture, wedding expenses, or the house.

Interviewer: Who does your husband send money to?

Respondent: To my father-in-law, all the men in the household (migrants) send money to my father-in-law.

Interviewer: What if you want something? Do you ask then?

Respondent: My father-in-law gives us whatever (money) he wishes to give. Like if my clothes are torn or if we want something, we ask our father-in-law, please buy it for us, then he buys it for us…

Interviewer: You and other women in the house don’t handle any money at all?

Respondent: If we need anything, we prepare a list and our father-in-law takes the list with him to the market. Sometimes he says, oh my god, such a huge bill (laughs).

(21-year-old woman, OBC, Gopalganj).

Agency of young wives of migrants in a joint family may exist in forms that are subtler, such as in being able to write out lists, raise requests and voice minor complaints with the final decision making authority particularly over household expenditures which are more within their domain. Women often saw their role as “ghar jodna” (keeping the house together) and did actively engage in household consumption decisions even when they were not the final decision makers. Drawing upon these normative roles but finding small avenues for maneuver, helps them influence decision making within the limits of their patriarchal habitus.

Trajectory 3: projecting the ethic of joint decisions: patriarchal bargains within the limits of the habitus

In the absence of older members in the household the shift in gender roles is not as straightforward. Women rarely responded that they autonomously took decisions. Instead, the most common narrative was of a cooperative joint household decision (often saying “milke lete hai”- we do it together), particularly among middle-aged women from nuclear households with relatively older children. The extent of “jointness” of the process, however, was defined in various ways. Most of the respondents mentioned that they often discussed household decisions, particularly those relating to expenditure on household goods, but they would not do anything their husband does not approve of. For example, in an interview with a respondent in Darbhanga, joint decision with discussion between spouses was emphasized. When probed about conflicting ideas on what to do on certain issues, the response yielded an interesting point of discussion.

Respondent: We decide together based on consulting each other. We don’t argue about it. We are only two people, what argument will we have?

Interviewer: But imagine, your thoughts don’t match with your husband’s on a certain issue, whose opinion prevails then?

Respondent: If he (my husband says), we shouldn’t do something, then we won’t do that.

(middle-aged woman, SC, Gopalganj)

In a similar vein, some respondents in the first instance articulated that most decisions were taken jointly by consulting each other. However, there were some caveats to their consensus building modality of decision making which were revealed only when further probed. The extent of “jointness” was limited to decisions on smaller assets. In most cases, it was understood that bigger decisions regarding the purchase of assets were often taken when men came home (short-term migrants). A few others emphasized that they would ask for permission, before they make smaller purchases but for bigger assets they would wait for their husband’s to return: “If there is any big decision, such as buying livestock, that we do only when our husband is here.”

Some others rationalized why men should be the final authority—“If he is the one providing us the money then we have to ask him before we spend”. While joint decisions most certainly incorporated discussions, “jointness” was contextual and did often favor the husband’s say in the final action. In another group discussion at Gaya, it was evident that women had to account for each expenditure or household items they purchased. Given that migrant remittances were irregular (once in two or three months) and nominal, household budgeting was seen as a stressful exercise.

Women were a part of joint decision making processes but largely in terms of influencing decisions, not necessarily as final authorities. This reinforces findings from other studies which have highlighted their role as influencers without challenging the authority of their husband or other male members. Farnworth et al. (Citation2021) argue that public rejection of their full autonomy in decision making and emphasizing joint authority is likely to be a hidden trajectory to bargained autonomy. This was observed for migrant husbands where they were the primary source of income, reiterating it as a form of survival trajectory.

On the other hand, it may also be an important characteristic of women’s relationship with farm work and their patriarchal habitus evolving as the family life cycle progresses. As women age, decision making authority in the household moves more toward a joint one in a migrant household or otherwise. This is more so as the bounds of patriarchal habitus get relaxed to some extent as age progresses. This could be well into 10 to 15 years (one respondent even mentioned 20) after marriage or even 5 to 6 years depending on household circumstances. In one of the interviews a respondent in her late 30s, explained that her mother-in-law often used to work with her father-in-law side by side on the field and both shared decision making authority equally. One of the older couples interviewed in Gopalganj, similarly even claimed that the male head contributed to household work including making meals. The doxic beliefs around farm work limit young married women from participating in farm work, however are renegotiated more toward a joint authority as the household moves into nuclear family models, and as the wife ages in all households, allowing for minor change in the habitus for covertly strategic purposes. While this was observed in both migrant and non-migrant households, it appeared to be more pronounced in the absence of a male member. The ability to discuss, advice, and even exhibit self-reported confidence in participating in decision making, partly by their own progression in the household, can be seen to offer security to men to pursue multi-local livelihoods while remaining within lines of their expected behavior.

Trajectory 4: using social capital for everyday farm decisions

A discussion on decision making is incomplete without referring to the involvement of others including neighbors. During the interviews, respondents were typically asked what agricultural activities they did in the field. The ensuing discussion helped to understand how women (middle-aged and older) made decisions on agriculture. The following short excerpt of the interaction gives a sense of how they adopt new technology and make decisions on seed use.

Interviewer: Where do you buy seeds?

Respondent: Nowadays seeds are available in the block office…

Interviewer: Who goes from the household to buy seeds from the block?

Respondent: My father-in-law used to go before, then my husband started going, now we go…

Interviewer: What about the information on how to use/how much/when to use (seed), who asks that?

Respondent: I ask…

Interviewer: Who do you ask?

Respondent: We ask our neighbors… those around us.

Another respondent pitches in: Not only ask! We get them to put (seeds) too …

(women FGD participants, Gaya)

In the absence of training, information and knowledge, and other male family members there is often a dependence on other persons in the village, to guide women on farm management. It was common practice to use social capital and rely on neighbors and others to fill in for lost male labor. Their decision making trajectory is evident in how they utilize their limited social capital and their ability to find the people to do the work at low costs. In another interesting interaction, a respondent was asked if they were aware of how much fertilizer to apply, what seed to use and the response was:

Respondent: No, I don’t know all that, I ask others, how much to put, how to put…

Interviewer: Who do you usually ask?

Respondent: We ask anyone, like see. I saw you, I would ask you to help me, if I see someone else, I will ask them for help.

Interviewer: Do you give some payment?

Respondent: We give some money, say about 10–15 rupees.

Most respondents highlighted that remittances rarely covered their household or agricultural expenses. With a minimal transformation in their human or economic capital, women articulated decision making trajectories, wielding their limited social connections, thereby making incremental changes in their habitus. But as such, their engagement with innovation or new agricultural practices remained weak at best. In fact, dependence for inputs on farm management and decisions reproduced the existing limits of their human, economic, and even physical capital. The lack of engagement and opportunity to consolidate these capitals, with support from local government agencies or agricultural research institutions confined the scope of bargains within their habitus. Male migration appears to trigger new dependencies reproducing hierarchies rather than change the contours of the habitus or the prevailing gender script.

Trajectory 5: assuming full control of household decisions

That male migration is but one influencing factor in the reshaping of habitus along with other factors, is reasonably clear. There are however, one or two limited narratives that support the complete transformation of autonomy and reshaping of the patriarchal habitus through migration. A 37-year-old respondent (woman, SC) in Mainidih village in Gopalganj presents an interesting case:

Interviewer: Who makes decision on how much to spend and how to spend?

Respondent: I manage all the expenditure.

Interviewer: Do you ask, or seek help from your husband in doing so?

Respondent: Yes, (definitive tone), I ask.

Interviewer: Suppose you receive Rs.5000 rupees from your husband, how do you spend it?

Respondent: On agriculture and household expenses, to cultivate rice, wheat …

Interviewer: Do you ask or consult or inform?

Respondent: We inform… he (husband) says, whatever you think is right, put your money in that.

Interviewer: Does he ask for a detailed account of your spending?

Respondent: No.

This account was further validated in an interview with her husband, a migrant working in Bengaluru, who mentioned that his job was to only send money while his wife managed the rest. When asked why he does not ask her how much she spent and such, he states that “she only informs.”

While this trajectory was rarely observed, it exemplifies the possibility of migration, along with other household factors enabling transformation of the habitus to a substantive degree. These examples indicate that male migrants entrust and appear to demonstrate confidence in women’s decision making actions, in bargain for greater security that women would be able to manage homes in the long intervals. In this particular example, the male migrant was away at least 6 to 7 months annually coming home only twice a year with a more regular job as an ironsmith. These circumstances enabled both spouses to renegotiate the boundaries, one gaining from the other’s role change. These observations reiterate the quantitative findings which show that higher migration duration often contributed to higher tendency toward joint and wife-only decision making. Albeit rare, this trajectory defines the possibility of a reshaping of habitus for both men and women through migration but under particular circumstances.

Conclusion

Our findings contradict some of the perceptions that left-behind wives gain more authority over various decisions (Desai & Banerji, Citation2008; Fakir & Abedin, Citation2021; Paris et al., Citation2005). We argue instead that in most cases decision making shifts in authority are nominal and are shaped by various factors including family arrangements and age. There is a greater preference for joint authority among women in nuclear households which is grounded in social practice and their self-interest to some extent given the context of precarious livelihoods, instead of transitioning into a fully autonomous decision making role.

The five trajectories discussed in the previous section and quantitative results highlight two important questions and some likely answers

I. Why does change toward women centered decision trajectories appear to be limited despite the migration of husbands? How does habitus persist?

One reason for this is that men and women are locked in strong boundaries of the habitus, as the other elements that shape their habitus remain largely the same. Marginal migration, precarious livelihoods and growing household expenditure entail poor increments in the household’s resources, capital, assets, including human capital in the form of knowledge of new agricultural technologies and practices. Male migration appears to not have a significant impact on the consolidation of livelihood capital. It is evident from trajectory 4 that knowledge of new varieties or pest management techniques are barely sufficient to shift agricultural decision making substantively despite male migration creating opportunities for women. Decision making “authority” in that case is more about deciding who to ask or approach, which may or may not be strategic and in some cases add to their dependence on others. Minor increments in the capacity of women, the household assets and capital at their disposal despite migration and the overall persistent conditions of inequalities in terms of class, caste and age, inherently reproduce habitus, restricting meaningful shifts in authority to women. As social positions remain intact entailing the limited scope of negotiations within the enduring habitus, allowing for more intangible hidden forms of bargains in the form of acquiescence, projecting a joint front, or depending on a wider social network appear to be preferred strategies. Staying within the limits of the habitus also restricts aspirations.

II. Is higher decision making authority an ideal to achieve? What implications does it have on development interventions in those contexts?

Related to the lack of meaningful authority, is the question of whether decision making authority in itself is an indicator of empowerment or an ideal sought after by women of different age groups. As is evident in three trajectories, decision making authority comes across as a burden, particularly for middle-aged women in nuclear households. Without duly recognizing the subjective experiences of the responsibility and work entailed in migration dominant regions, promoting actions through various projects and programs targeting increased decision making may be harmful unless there is an understanding and concerted action on their constraints in terms of control of economic and human capital assets and resources. Visible transformation of the habitus requires a more meaningful transformation of livelihood capitals. A more feasible option to achieve this would be to equip women with knowledge and support, build collective assets and address credit needs for both productive and consumption needs. Moreover, hierarchical inequalities of caste remain largely unchanged and influence the allocation of land, titles, credit and roles in the village. Meaningful break from the older bounds of the habitus requires shifts in the hierarchies that perpetuate social norms and ideologies. This would mean engaging with communities in lower hierarchies, the land poor castes, in building greater resilience to household shocks and reducing the incidence of maladaptive migration. Strategies focused on expanding opportunities within villages (some women also expressed interest in doing additional remunerative work in the confines of their households) can help diversify livelihoods and enable tangible transformation of the habitus, over time.

Acknowledgments

We thank the team at Dev Insights for the data collection. We extend our gratitude to the participants of the study for their invaluable insights and time. We thank Dr Mou Rani Sarker for her assistance in refining quantitative analysis methodology, editing, proofreading, and formatting the document.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Rohini Ram Mohan

Rohini Ram Mohan is currently an MPA Development Practice candidate at School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University. She was previously a Senior Specialist, Gender (Research) with the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI). Rohini’s engagement in Agricultural R4D projects focused on gender dynamics in seed systems and rice breeding and she has contributed to research focused on women’s economic empowerment through entrepreneurship and on gendered impacts of migration in South Asia. Rohini has an MPhil in Sociology from Delhi University.

Ranjitha Puskur

Ranjitha Puskur leads the Research Program on Gender and Livelihoods at the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI). She also leads the Evidence Module of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) Gender Platform. She has a PhD in agricultural economics. She has been with CGIAR since 2002, leading research on gender and innovation systems in water, livestock, fish, and rice. Her research focuses on mobilizing science and knowledge for innovation to achieve pro-women and pro-poor development outcomes in Africa, South and Southeast Asia, and the Pacific.

D. Chandrasekar

Chandrasekar D is a doctoral student at Madras Institute of Development Studies, Chennai, India. His PhD thesis focuses on “Socio-Economic Development of Dalits and Social Capital.” He completed his MSc in Economics from Madras School of Economics, Chennai, India. He is interested in Development Economics, Social Capital, and Econometrics.

Harold Glenn A. Valera

Harold Glenn A. Valera is an economic modeler in the Impact Evaluation, Policy and Foresight Cluster at the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI). He was a Postdoctoral Fellow at IRRI and an Assistant Professor of economics at the University of the Philippines Los Baños. He has a PhD in Economics from the University of Waikato and an MSc in Agricultural Economics from Purdue University.

Notes

1 This can be related to anecdotal information emerging in the interviews about labour shortages and the increased use of machine renting as an alternative for some households.

References

- Acosta, M., van Bommel, S., van Wessel, M., Ampaire, E. L., Jassogne, L., & Feindt, P. H. (2019). Discursive translations of gender mainstreaming norms: The case of agricultural and climate change policies in Uganda. Women’s Studies International Forum, 74, 9–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2019.02.010

- Alkire, S., Meinzen-Dick, R., Peterman, A., Quisumbing, A., Seymour, G., & Vaz, A. (2013). The women’s empowerment in agriculture index. World Development, 52, 71–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.06.007

- Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a theory of practice (Vol. 16). Cambridge University Press.

- Debnath, P., & Selim, N. (2009). Impact of short-term male migration on their wives left behind: A case study of Bangladesh. In International Organization for Migration (Ed.), Gender and labor migration in Asia (pp. 121–151). IOM.

- de Haan, L., & Zoomers, A. (2005). Exploring the frontier of livelihoods research. Development and Change, 36(1), 27–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0012-155X.2005.00401.x

- Desai, S., & Banerji, M. (2008). Negotiated identities: Male migration and left-behind wives in India. Journal of Population Research, 25(3), 337–355.

- Fakir, A., & Abedin, N. (2021). Empowered by absence: Does male out-migration empower female household heads left behind. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 22(2), 503–527. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-019-00754-0

- Farnworth, C. R., Jafry, T., Bharati, P., Badstue, L., & Yadav, A. (2021). From working in the fields to taking control. Towards a typology of women’s decision-making in wheat in India. The European Journal of Development Research, 33(3), 526–552. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-020-00281-0

- Gulati, L. (1993). In the absence of their men: The impact of male migration on women. Sage Publications.

- Hadi, A. (2001). International migration and the change of women’s position among the left-behind in rural Bangladesh. International Journal of Population Geography, 7(1), 53–61. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijpg.211

- Liao, T. F. (1994). Interpreting probability models logit, probit, and other generalised linear models. Sage.

- Locke, C., Muljono, P., McDougall, C., & Morgan, M. (2017). Innovation and gendered negotiations: Insights from six small scale fishing communities. Fish and Fisheries, 18(5), 943–957. https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12216

- Luna, S. S., & Rahman, M. M. (2019). Migrant wives: Dynamics of the empowerment process. Migration and Development. Migration and Development, 8(3), 320–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/21632324.2018.1520446

- Paris, T., Singh, A., Luis, J., & Hossain, M. (2005). Labour outmigration, livelihood of rice farming households and women left behind: A case study in Eastern Uttar Pradesh. Economic and Political Weekly, 40(25), 2522–2529. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4416781

- Pattnaik, I., Lahiri-Dutt, K., Lockie, S., & Pritchard, B. (2017). The feminization of agriculture or the feminization of agrarian distress? Tracking the trajectory of women in agriculture in India. Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, 23(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13547860.2017.1394569

- Ram Mohan, R., & Puskur, R. (2021). A toolkit for unpacking gender dynamics of migration in rice-based agricultural systems in South Asia. https://zenodo.org/record/5567879#.Ycaq331BxQI

- Rashid, S. R. (2013). Bangladeshi women’s experiences of their men’s migration: Rethinking power, agency, and subordination. Asian Survey, 53(5), 883–908. https://doi.org/10.1525/as.2013.53.5.883

- Singh, C. (2019). Migration as a driver of changing household structures: Implications for local livelihoods and adaptation. Migration and Development, 8(3), 301–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/21632324.2019.1589073

- Singh, N. P., Singh, R. P., Kumar, R., Padaria, R. N., Singh, A., & Varghese, N. (2011). Labor migration in Indo-Gangetic plains: Determinants and impacts on socio-economic welfare. Agricultural Economics Research Review, 24, 449–458.

- Sinha, B., Jha, S., & Negi, N. S. (2012). Migration and empowerment: The experience of women in households in India where migration of a husband has occurred. Journal of Gender Studies, 21(1), 61–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2012.639551

- Wooldridge, J. M. (2002). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. MIT Press.

- Yabiku, S. T., Agadjanian, V., & Sevoyan, A. (2010). Husbands’ labor migration and wives’ autonomy Mozambique 2000-2006. Population Studies, 64(3), 293–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/00324728.2010.510200