Abstract

Technological innovations in fisheries have generally been seen to exclude women, exacerbating both their economic marginalization and lack of political voice. Such a view however ignores the complexities underpinning the interface between technologies and social relationships, in particular, those of gender. In this article, we explore the impact of ring seine expansion in Cuddalore, a costal district of Tamil Nadu on the east coast of southern India, through the experiences of women fish auctioneers. We argue that women’s contributions to the fisheries sector as auctioneers serves to both sustain and finance the expansion of the ring seine technology and does not just play a supportive, buffering role for household survival. The profitability of auctioneer work has transformed these women into the primary household providers, responsible for securing the intergenerational wellbeing of their extended families. Yet, women are not a homogenous group, hence exploring why some women are able to access these opportunities successfully, negotiating both their entry into the market and financing of their roles, while others are excluded, illuminates how women navigate gendered constraints in relation to technological changes in the sector. We conclude by reflecting on the impact of the recent ring seine ban on the perceived wellbeing and growing indebtedness of these women.

Introduction

The impact of technological innovations in agriculture and food production is demonstrably uneven when it comes to gender. While proposed outcomes seek to increase production, productivity, and income, with the aim of alleviating poverty and reducing workloads (Rola‐Rubzen et al., Citation2020), the introduction of these new technologies can often reinforce gender inequalities, restrict access, and displace women as newly mechanized tasks become the domains of men (Fischer et al., Citation2018; Harriss-White, Citation2004; Mudege et al., Citation2017). The fisheries sector is no exception (Gopal et al., Citation2014), as seen in the introduction of “pen” or enclosure technologies in aquaculture systems in Odisha, India (Ray & Mukherjee, Citation2022), or the motorization and mechanization of fishing gear in Kerala, India (Aswathy & Kalpana, Citation2018; Gulati, Citation1984), both of which ended up exacerbating existing inequalities. While men in the fishing industry could potentially earn more than women with the new gear (Gopal et al., Citation2023), they were also away from their homes for longer periods of time and impacted more severely by climatic variability. Women from poorer fishing households, in particular, had to take on a range of poorly paid and strenuous work such as headloading fish, net-making, shell collection, coir rope making, amongst others, to sustain their households (Gulati, Citation1984). Yet, one also finds variations in women’s activities across time and space as a result of the interplay of technological and wider economic changes with gender relations. Rubinoff (Citation1999, p. 637) demonstrates that in the Indian state of Goa, while Hindu women fish vendors remained at the bottom of the hierarchy, Christian women fish traders were able to transform from being headloaders to “market entrepreneurs” working in small cooperative groups, following the introduction of mechanized trawlers.

Underlying gender inequalities, such as lack of access to and control over resources and assets, particularly financing capital and/or social networks needed to ensure product supply, exclusion from traditional resource governance and decision-making structures, as well as limited education, information and skills training, can prevent women from taking advantage of opportunities presented by technological change (Hapke, Citation2001; Rola‐Rubzen et al., Citation2020). Socio-cultural norms around appropriate gender behavior (that restrict mobility and labor choices) and gendered expectations (responsibilities for childrearing and domestic duties) can become further barriers to women’s access and adoption of technological innovations (Rubinoff, Citation1999; World Bank, FAO, and IFAD, Citation2009). In the case of Zanzibar, the introduction of tubular nets for women seaweed farmers was seen as a “disruptive innovation” with potential to change the status quo and was hence met with backlash by better established male seaweed farmers (Brugere et al., Citation2020). Consequently, Lawless et al.’s (Citation2019) proposal that a distinction should be made between the availability of livelihoods open to women (i.e., diversification) and the ability of women to actually exercise livelihood choice, is significant when considering the opportunities presented by innovations in capture technologies within fisheries.

Despite forty percent of fish workers, 45 million globally, being women (Evans, Citation2017; Swathi Lekshmi et al., Citation2022), women’s roles in pre- and post-harvest fisheries activities have remained largely invisible (Bennett, Citation2005), with research and policy investments focusing on improving fish capture technologies—the domain of men—that simultaneously mitigate climatic and biophysical hazards. Women’s work in the sector is often unpaid or low paid, unofficial, or fluctuating, resulting in its undervaluation both in economic terms and “because it is performed by women” (Pedroza-Gutiérrez & Hapke, Citation2022, p. 1734, italics in original), leading to limited industry recognition. Consequently, while women’s work might support, subsidize and/or sustain men’s fishing work, women are not involved or taken into account in fishery related decision-making at local or national levels (Rohe et al., Citation2018). Typically, fisher men are considered the primary income provider and women’s labor (for example in fish drying, smoking or vending), is perceived as a “buffer” to fill gaps in household finances (Gustavsson, Citation2020), or an extension of household reproductive labor that both subsidizes production and enables capital accumulation (Dunaway, Citation2013). Indeed, as Gustavsson describes, this conceptualization of women’s labor is so common that “governments have often relied on women’s resilience building – ‘buffering’– practices without recognising them as fisheries workers with the rights that this form of recognition would entail” (Citation2020, p. 40).

Yet, women are not always only supplementary earners. The widespread adoption of ring seine fishing in Cuddalore district of Tamil Nadu on the east coast of southern India, over the past two decades, especially following the tsunami of December 2004, that left a trail of death and destruction in the area, has transformed women’s lives across a number of domains, including household finances, and their access to pre and post capture fishery work. Although women are not homogenous and perform a diversity of tasks in the fisheries sector—from auctioning the catch to vending fish, from cutting and drying the fish to disposing of the waste, from selling ice, to tea and cooked food—and their experiences have been uneven, the perspectives of Cuddalore’s women fish auctioneers challenge many of the assumptions around women’s fisheries work, particularly the expectation that such work is primarily “supportive”. Far from being peripheral, women’s work as fish auctioneers actively sustains fisheries by financing ring seine vessels and becoming a nexus point for spreading ring-seine wealth through loans and investments within fishing communities. Further, the increased profitability of auctioning the catch of ring seine boats has meant that many women’s incomes have outstripped that of men, making them the primary providers in both male and female headed households. This has enabled women to sustain fishing households and secure the wellbeing aspirations of their families (Hapke, Citation2001; Rubinoff, Citation1999).

By exploring the gendered trajectories of fish auctioneers in this article, we explore how some women are able to navigate gendered inequalities and constraints to grasp opportunities emerging from technical changes in the fishing enterprise, while other women remain excluded. In doing so, we present new understandings of how the introduction of new fisheries technology can transform women’s roles, access to resources and familial wellbeing, but only under certain social and economic conditions.

We begin by contextualizing the rapid expansion of ring seines in Cuddalore district of Tamil Nadu, where our research is located, and the impact on women, before going on to present our methodology, and the findings from interviews with fish auctioneers collected through an extended period of fieldwork from 2016 to 2022. We present how women navigate constraints to become auctioneers, the role they play in financing ring seine expansion and the opportunities and risks brought about through rapid expansion, before considering the impact of the ring seine ban, that began to be implemented from 2019 and fully halted ring seine fishing in 2021, on wellbeing and growing indebtedness.

Context

The ring seine expansion across Tamil Nadu

Post tsunami saw the widespread adoption of ring seine fishing across Tamil Nadu, with Cuddalore district becoming a regional “hot spot” with 134 out of 219 vessels, or 61% of the state’s fleet (CMFRI-DoF, Citation2020, p. 28, table 12). While new to Tamil Nadu, ring seining or purse seining had developed alongside bottom trawling on the west coast of India through the Indo-Norwegian project for fisheries modernization (1953–1972). Trawlers addressed the growing export demand for shrimps in the late 1960s (Kurien, Citation1978), and purse seines focused on encircling shoaling schools of small pelagics (sardines, mackerels, anchovies) for domestic consumption (Pravin & Meenakumari, Citation2016). Both these technologies negatively affected the livelihoods of small-scale and artisanal fishers, and to overcome conflict, the state sought to regulate trawl and purse seine gear (including mesh size), while at the same time supporting the motorization of small crafts. This process of motorization enabled small-scale fishers along the Southwest Coast of India to adopt a down-sized version of the purse seine technology (Bavinck, Citation2020), what came to be known as ring seine, in the early 1980s (Edwin & Das, Citation2015), reaching the fishing port of Pazhayar, on the border of Cuddalore district, in the late 1990s. This coincided with the movement of oil sardines to the east coast of India, a result, amongst other factors, of rising sea surface temperatures in the southwestern coast (Vivekanandan et al., Citation2009).

The December 2004 tsunami was a turning point in the expansion of ring seine fisheries in Cuddalore district. Tsunami relief had transformed the small-scale artisanal fleet by providing fibre-reinforced plastic (FRP) boats with out-board motors to most fisher households. In fact, of a total of 4579 boats recorded in Cuddalore district in 2016, 2042 or 45% were motorized (the state average being 73%), 9% mechanized (purse seine and trawlers) and the rest artisanal craft (CMFRI-DoF, Citation2020). Groups of 3–5 motorized boats could use smaller seine nets (around 250–400 m) to encircle and catch larger quantities of fish, especially oil sardines and mackerel (Rao & Manimohan, Citation2020; Sivadas et al., Citation2019). The early success led to a rapid spread of the ring seine technology after 2009, with investments in steel boats, more than 25 m in length, with in-board engines of over 500 hp (Das & Edwin, Citation2018). The size of the net also increased to 1000 m. Local fishers developed collaborative mechanisms for sharing the cost of nets and vessels, with 20–30 fishers pooling both capital and labor, making ring seines both attainable and lucrative for many (Bavinck, Citation2020; Rao & Manimohan, Citation2020). FRP boats were used as carrier boats to transfer the catch from the ring-seiners to the harbor, thus sharing the benefits with a larger group of small-scale fishers. With growing profits from the substantial oil sardine landings, by 2017, several ring seiners initiated multiday fishing, far away from the territorial waters, for oceanic tuna. The craft remained unchanged, but a new gear with mesh size of 110 mm and a net size of 2000 to 2100 m was fabricated for this purpose, closer to a regular purse seine. During this phase, the number of shareholders per vessel declined as partners split to reinvest profits in their own vessels (Ibid.). The rapid expansion of ring seines within the local fishing community is captured well in the account of 39-year-old Raman:

Initially, sixteen families, all close relatives, came together to form a ring seine unit. Each family contributed Rs. 20,000Footnote1, so in total we got Rs. 3,20,000. We bought a boat with equipment and thirty members from our sixteen families came as crew for fishing. We shared the costs and the profits and everything went well for two years… but then everyone wanted their own unit. Now all the 16 members have started their own ring seine units with five or six shareholders, who are either very close relatives or friends. In my village, we have over 150 ring-seine units (Rao & Manimohan, Citation2020, p. 11).

Impact of ring-seine expansion on women

The expansion of the ring seine led to significant changes for women in both opportunity and access to post-harvest work (see Gopal et al., Citation2023 for Kerala). Earlier small-scale fishers landed their boats on the village beach, with women centrally involved with post-harvest activities such as sorting, auctioning, marketing and processing of the catch. However, with the shift to larger boats, subsequent move to the harbors, and growing competition from large traders and exporters, the numbers of women involved in fish marketing declined considerably (Gopal et al., Citation2014, p. 71). Women have found it difficult to travel the distance to continue post-harvest activities while also meeting their household responsibilities and have consequently lost out in terms of unloading, transportation and sale of catch (Das & Edwin, Citation2018). For those women who persist,

The drudgery of life has increased… as they have to travel longer distances to reach harbors, wait for the catch to be landed, jostle to get a share, and … spend longer hours than before in procuring and marketing the catch (Gopal et al., Citation2014, p. 76).

Apart from the spatial shift from the beach to the harbor, the increased quantity of the catch has also transformed the market. Ring seines catch small pelagic species, such as oil sardines, anchovies and mackerel, primarily driven by domestic demand in the neighboring state of Kerala and the rapidly growing fish meal industry in India. But, ring seines also produce larger catches which can lead to a decline in market price during peak ring seine seasons (Das & Edwin, Citation2018, p. 51). The need to secure the best price has opened up opportunities for women as auctioneers, using their voice and negotiating skills for this purpose. 90% of auctioneers have traditionally been women, and this role has persisted in the context of the ring seines, more so than for mechanized trawlers. This is perhaps related to the process by which the ring seine technology was introduced, with fishers themselves playing a prominent role, through the pooling of resources, in its development and expansion, in contrast to the growth of mechanized trawling in the 1970s, where “outside” capital was significant, hence the technology too was controlled by elites and non-fisher investors, not small-scale fishers.

While ring seines might have negatively impacted some small-scale fishers and fish stocks (as the same schools of fish are targeted), the low price and availability of fish has been beneficial for women able to access the market to purchase fish for vending and drying, including those from non-fishing castes. This is particularly the case for female headed households (widows, separated, or whose husbands were unable to work) who take up fish vending out of financial necessity, often because stigma prevents them accessing loans or finding other employment (Azmi et al., Citation2021; Hapke & Ayyankeril, Citation2018) and women from small scale non-mechanized fishing households who supplement their income through fish vending when prices are low. However, the availability of fish has also increased competition as more women take up vending. As a result, we found women trying to differentiate themselves by traveling further to sell their fish or spending more time cleaning and preparing fish to add value and increase the desirability of their fish.

The expansion of the ring seine has clearly had varying effects on women, restricting market access for those unable to visit the harbors and larger markets, while enhancing opportunities for those able to invest in auctioning, drying fish, or other subsidiary activities. Interestingly, while women do not typically have shares in ring-seine vessels or gear (Gopal et al., Citation2014), we found they were economically and socially invested in these vessels. Women played a significant role in raising capital for men’s ring seine investments, through pledging their gold jewelry, accessing family networks or private financiers for loans to finance rings seine shares (Rao & Manimohan, Citation2020). For example, Manjini, 45, has bought two shares in a boat, investing Rs. 800,000 borrowed from a private lender at a monthly interest of 3%. With the fishing ban he was unable to pay the interest and is in debt, so his wife vends in the market and controls the finances. He said:

The important decisions are taken by my wife. If I want money, that amount is mobilized by her. She borrows from the pawn brokers or money lenders (Author’s interview).

Methodology

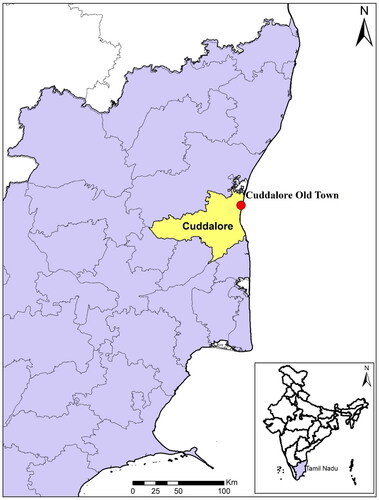

This paper draws on research conducted between 2016 and 2022 as part of two larger research projects, “Migration and Collectives/Networks as pathways out of poverty” (2016–2019) and “Coastal transformations and fisher wellbeing” (2019–2022). Ethical approval was secured from the University of East Anglia’s International Development Ethics Committee, and all procedures for informed consent and safety of participants followed. All names used in the paper are pseudonyms. The paper is based on a study of two villages close to the Old Town harbor in Cuddalore district of Tamil Nadu (see ).

We used an ethnographic approach and conducted semi structured interviews with 73 women involved across post-harvest work including auctioneers, vendors, fish cutters and those drying fish, as well as wives of fishermen. The interviews sought to understand their work-life trajectories, including marriage, male migration and intra-household relations, divisions of labor, control over resources and the management of money, perceptions of wellbeing and their future aspirations. Interviews were also conducted with their husbands (when available) on similar themes. Additionally, focus group discussions were conducted with ring seine share-holders, male migrants and youth, to understand their views on ring seines, processes of group formation, strategies for raising capital, the challenges they confronted and their perceptions of change. The interviews were conducted in Tamil by the first author, with support from a research associate. They were transcribed and translated into English and coded thematically using Nvivo software. Of the 73 women interviewed, seven were auctioneers, constituting about one-fourth of women auctioneers (approximately 30) operating in Cuddalore Old Town harbor. Our paper draws primarily from this group of interviews. Appendix Table A1 provides brief profiles of these women auctioneers.

The experiences of women fish auctioneers in Cuddalore

What is an auctioneer?

Women have traditionally been involved in the sale and marketing of fish, serving as vendors, and auctioneers, for their family boats landing on the local beaches. The shift to harbors and larger markets has generally favored large scale traders buying in bulk, predominantly men, and made these spaces more masculine (Hapke, Citation2001). However, with ring seines first operating from village beaches and small landing centers, and gradually growing in size and scale and shifting to harbors, women’s roles as auctioneers has also expanded into the harbors.

Once the harbor and market were the world of men. Now after the introduction of ring seine we women have gradually intruded into the harbor and cornered the market to a considerable extent (Rani, auctioneer, age 52).

As auctioneers for larger, more profitable ring seine vessels, women function as both moneylender and merchant. They advance money to vessel owners for capital and operational expenses (such as repairs) which is then recouped through a percentage of the sales made at the fish auction (Das & Edwin, Citation2018). Given the large catch sizes and the tendency for prices to fall, the auctioneers play a critical function in negotiating the best price possible through their bargaining skills, including the ability to persist and convince. Apart from returns to boats, this has implications for their own earnings too. Women auctioneers also became intermediaries for big traders procuring for the wholesale and fish meal markets, though they were often unable to fix the price directly with the boat owners. As auctioneer Valli (age 58) described, the situation is unusual because unlike with the trawlers, traders have to go through women auctioneers to access ring seine boats. Another auctioneer made a similar point:

In Old Town Cuddalore, auctioneers are mostly women. Big merchants buy fish from us [auctioneers] and then sell them mostly outside the state. Big merchants give advance to trawlers [both in-board and steel boats]. But for Ring-seine we [local auctioneers] give advance and auction the fish (Neesha, auctioneer, 38).

If the advance for a boat is Rs. 500,000, at the end of the year the owners keep some of this, reducing the advance to Rs. 350,000. I then need to add Rs. 150,000 for the new year, usually made up from a combination of this year’s profits, minus prior debts, and new loans.

Entering the market and learning the trade

Most women become auctioneers having first learnt about the market as a fish vendor. There are important reasons for this. They must be able to leave the house to visit the markets, where they can learn about how trade is conducted and meet potential investors and traders. Neesha (38) is a transgender woman from the Pattinavar fishing community. Initially she began by drying and selling fish both for human consumption and as poultry feed before expanding into auction work. She said:

When I was seventeen years old, I started doing auctioning work and selling fish. My brother was doing fishing, but he did not take me along with him. A woman nearby used to talk to me often as I talk like a girl. She asked me, “why don’t you go selling fish, instead of simply roaming around.” She took me to sell fish in OT harbor. I was selling fish there for almost three months. Many started noticing me as I have a loud voice, so could get a crowd. Many wanted to buy fish from me and the fish I auctioned got a high price. They started looking at me as a lucky star (kairasi). So, many people who catch fish, they came to me and asked me to sell their fish for them.

…because of her contacts outside, she [Neesha] was able to invest in the business. But we don’t have that. We are at home only. When she was a boy, she used to go out and meet people. Since then, she was able to maintain a good relationship with many people.

Neesha’s experience is not dissimilar to other women auctioneers, though she is much younger. In most cases they began as small-scale fish vendors, traveling to markets to sell their fish. Veni (57 years) started as a fish vendor, having been introduced to the market by her mother who initially purchased fish for her to sell. She started auctioning in the late 1990s, and now is both a successful auctioneer and a large vendor.Footnote2 While lack of education can limit opportunities for employment, there are no such restrictions to vending and auctioning—it is more about voice strength, persistence, risk-taking, negotiation and persuasion. While one may assume that it is only wealthier women, those with easy access to capital, who can become auctioneers, interestingly, several of the women auctioneers we interviewed had unstable family situations, leaving them economically vulnerable and requiring additional income. Veni’s husband left her with 4 sons and a daughter. Following the death of one of her sons, she now supports his family (wife and child), as well as her younger unmarried sons, one of whom she employs on a daily wage to help her with the business. Recognizing the importance of accessing such work in her own life, Veni has since introduced other women in similar situations to vending, fish cutting, and preparing her fish for auction.

Women without jobs, women without their husband, women whose husband is a drunkard, they all ask me to help them with any job in order to earn money. I introduce them to this business. I have helped so many women like that. I also help them by giving money, rice, etc. From what I can remember, I have introduced this job to over 20 women and made their life better.

Understanding market relationships between traders, boat owners, and vendors, and learning the skills required for auctioning rely on a network of women, be it mothers or friends, to share this knowledge. In this respect, women’s access is uneven and relies on being able to access wider networks of women vendors and auctioneers.

Financing their roles

The significant initial capital investment required is perhaps the main constraint to becoming an auctioneer. A sizeable advance must be paid before the start of the season to secure the right to auction the year’s catch. Only when fish are sold does the auctioneer start to recoup their initial investment. The financing of auctioneer investment is consequently a complicated mix of juggling multiple loans and building capital. Auctioneers take five distinct, though interconnected routes to financing their work: (1) collective pooling of resources; (2) personal savings; (3) loans from private lenders; (4) loans from family and friends; and (5) savings in community chit funds.

Collective pooling of resources

Most of the auctioneers we interviewed had pooled resources with a few other women auctioneers, enabling them to make up for their limited means, enhance mutual support in terms of managing the auctioning work on a day-to-day basis and reduce individual risk. As Valli commented:

For ring-seine boats we have to give upto Rs.1.5 million as an advance amount to become an auctioneer. I have given advances to seven ring seine boats, along with my partners Mala and Hamsa. We are from the same village. If the boat’s share-holders demand an advance of Rs. 1 million, then the three of us divide this amongst ourselves. None of us is rich enough to afford the full advance, so we pledge our gold jewels and get the money we need. Sometimes we have to take loans from private financiers at high rates of interest (4-5 per cent per month). As an example, for a Rs. 1 million loan, we are now paying an interest of Rs. 40,000 each month.

Personal savings

The increased availability of fish during the ring seine season has increased opportunities to purchase cheap fish for drying and selling, enabling some savings. For successful vendors, this provides means for accruing enough capital to make the initial ring seine auctioneer investment. Neesha began with buying small amounts of fish to dry for poultry feed, before taking advantage of seasonal availability to expand into the drying of edible fish. Over time she built up her business and began to employ other women to help with drying.

Whatever I got as profit, I again invested it in the business. I did not share the profit with anyone. Again and again, I invested in the business. The business started growing. In the end, I got a lump sum amount which I advanced to a boat, and then started auctioning.

Frequently auctioneers act both as auctioneers and vendors to spread their risk and increase their earnings. Rani noted:

The fish vending women would buy fish from me for Rs. 300 or Rs. 400 per basket. If I want fish for vending, I can’t take it from the boat which I have given an advance to, but I buy fish from the smaller boats and sell them in the market. This helps me save some money.

Loans from private lenders

As Valli recounted above, financing through private loans at high interest rates is common, particularly for short term loans to meet financial gaps, such as auctioneers covering the costs of vessel repairs, or financing family expenses, which they then repay completely from their auctioneer profits later in the season. Lakshmi (47) was originally a fish vendor but has been an auctioneer for 10 years for ring seine steel boats and FRP boats. From our fieldnotes:

Her husband goes fishing in ring seine boats and at other times stays home and drinks. She would earn at least Rs. 2000 auctioning ring seine catches, measuring and weighing the fish. She has borrowed three times, each time from different private companies. Lakshmi used the money as an advance to different boats to get the rights to auction their fish. She has also taken a loan for her children’s education and family functions. The cheapest was the Suryoday company, she said, which charged 25 per cent interest. She had also pawned her thali (gold necklace) to pay money into a women’s group loan.

Loans from family and friends

For Veni, the initial investment of Rs. 5000 came from a family member who asked her if she would like to invest in auctioning; for Neesha, it was friends:

I have given Rs. 3-400,000 as an advance for each boat for which I do the auctioning work. Now I have been auctioning for four boats including one steel boat. All are ring seine fishing boats…If I don’t have money, I borrow it from my friends and then from whatever profit I make from auctioning and my dry fish business, I pay back the loan. I am able to do these businesses only with the loans I get from people whom I know.

Savings in community chit funds

Chit funds are a popular way of raising finances among women. Auctioneers typically use cheettu (community chit fund) to balance their funds, sometimes in combination with other raised capital to pay the initial vessel advance, or more commonly, to cover additional vessel expenses, or family needs.

I have been selling fish since the age of 15. I started thinking to become an auctioneer and spoke to my friend who was also a fish vendor. We have known each other for a long time and had been pooling our money together with other vendors to buy fish in the Old Town market. We started working as auctioneers in 2008. I invested my savings in this business. I had also been saving in a cheettu worth Rs. 300,000. Initially, I used this to purchase a share in a ring seine boat, entitling me to auctioning rights. Then I and my partner decided to give advance for two more boats, Rs. 1.5 million for one and Rs. 1 million for another. For this, I borrowed Rs. 1 million for interest from private lenders (Rani, 52).

However, for Neesha, her transgender identity has prevented her from accessing such community funds. She has not been able to secure bank loans or been accepted as a member of any of the 20 local women’s Self-Help Groups that pool and loan money. As a result, her family and friends have been her major support, and fish vending and auctioning has been an important source of financial security. She said:

The boat owners did not reject me. They don’t care who I am. They just wanted me to sell their fish. I can get them a higher price, as I can auction loudly. If they had started avoiding me, I could not have succeeded in my business. With their support, I was able to have my reassignment operation. They look at me as an auctioneer, nothing else.

Meeting the demands of ring seine expansion

Although the expansion of ring seines across the state opened up opportunities for women to expand into more profitable roles as auctioneers, the scale of investments and accompanying expenses have increased rapidly with the growing size of vessels. The success of a ring seine vessel is seen as mutually beneficial for boat owners and auctioneers alike. Auctioneers are consequently expected to make advances for repairs and lost nets. Neesha noted:

Suddenly if they lost the net in the sea, they will ask us to give Rs. 1-200,000 even if we have already paid them an advance. We have to give, because otherwise, without a net, they can’t go fishing and we’ve lost our business too. Both of us will face problems, so if any damage happens to boat or net, both auctioneer and boat owners have to bear the expenses. We have to fix the problem and go fishing…. Today, I did not go for auction. My boat went for fishing twenty days ago, and they lost the net worth Rs. 1.8 million. Only the empty boat came back. The net vanished in the sea.

This is a very risky job. We have to face both successes and failures. Self-confidence is the real investment in this job. For the past two years the yield is not that good. We conduct auction as well as go to market to sell fish. Over the period the loan has accumulated. Now we have to settle a loan amount of almost Rs. 2 million to moneylenders. We don’t give up in this work. We have confidence that we will settle the loans as soon as possible.

If we get Rs. 150,000 in the first season, we will give this money to people from whom we got a loan. Some consider it as interest and some good people take it as capital repayment. If we repay the money before the end of the year, the interest will reduce. I get loans at 2 percent interest rate; the yearly interest payment is Rs. 120,000. If we do only one [season] we cannot repay the loan. I therefore also maintain cows for milk, as well as some goats and poultry (Auctioneer Neesha).

However, as fishermen too have reinvested their profits, vessel and gear size have increased. As a result, auctioneers are expected to contribute much larger advances and pay for increasingly more expensive repairs and crew gifts. What began with Rs. 100,000 investment per boat can now be 5 to 10 times more and grow into vast sums if auctioneers manage multiple vessels. This inevitably drives women to take much larger loans. As auctioneer Veni explains,

People from here buy ring seines for Rs. 3, 4 or 5 million, asking us for Rs. 1-2 million. Fifteen years ago, we gave them half a million rupees and they gave us 5 per cent of what they earn as commission. After 2 years, they [boat owners] bought a bigger ring seine, they asked me for another Rs. 1 million. I didn’t have that much money, so I borrowed from others for the purpose. The deal now is whatever they earn they have to give me 10 per cent out of it.

Despite the burden of interest, the benefit of this increased investment is a larger share in the profits, allowing women to invest in family futures beyond just sustaining daily expenses. Veni continued:

Through this, I started earning better. Our lifestyle became better. I educated my children in good English medium schools and did everything I could. Before that I couldn’t afford all those things by doing small scale fishing business…[As ring seine auctioneer] I could even earn Rs. 100,000 in a day, if the catch was good. Because of this [earning more money] my status also grew in society. I am independent. I can do/buy whatever I want.

Impact of the ring seine ban

Quality of life and perceptions of wellbeing

The significant rise in income among ring seine auctioneers allowed many women to make long term investments in education and housing, thereby improving the prospects of their dependents and overall quality of life. As Veni’s story clearly demonstrates, the introduction of the ring seine has had a dramatic impact on both material and subjective wellbeing.

Veni built her own house from her ring seine earnings over the course of four years. Her daughter and granddaughter live with her, and she also pays for the education of all her other grandchildren. One of her sons works for her, and she pays him a wage of Rs. 500 a day, another (Rambo) was attending college and she hoped would join the civil services. She said:

I’m running my family with my earnings…Whatever they need for education, I help them. I give them money to buy slippers, for a haircut, clothes, earrings and whatever they ask for. So, I’m taking care of everything happening in this big family. None of my children earn money. When ring seine was there, some of my problems disappeared. Though I borrowed money to invest in ring seine, I made a profit out of it. I used to do a lot.

I thought if I educate Rambo to be a Collector (civil servant), he could help me take care of this big family. He studied for 2 years [in Delhi] and he wrote the exam (for the civil services), but he couldn’t clear it in his first attempt. Then they banned ring seine so I couldn’t afford his education anymore. It was a big loss for me. I borrowed money for ring seine. The ones who gave me money, started asking for their money back. So, I couldn’t afford his education…

I don’t know what to do now. I’m a woman and I’m also getting old, but I’m still working as usual and earning money to run this family. With the ring seine I got more profits. With the way I do business right now, I earn Rs. 800, 1000 or 1200 maximum per day. With that money I can only manage the everyday expenses of our three families and pay my debt. I really can’t help him to study further.

Everyone would earn a lot of money [when] they went fishing on the ring seine boat. They put their children in good schools. They built a big house. They started living comfortably. The situation is very difficult for the fishermen now, after the ring seine was banned. Fish vendors, auctioneers and auto drivers are all affected, not only the fishermen. Other castes supporting the ring seine boat were also earning well and their families were progressing. Now they too are suffering without work. Those who are partners in the ring seine boat have a lot of debt. Some people commit suicide unable to endure the burden of debt. I now buy the fish that comes into the harbor, but there is no profit in it. It is only enough for daily consumption. If ring seine boats go fishing, everyone will be better off.

Women have a lot of work to do when it comes to fish in ring seine boats. Women load the fish. Women put ice on the fish. Women measure the fish. Now all families are in a difficult situation, the family of a fisherman fishing in a ring seine boat is now in a very poor condition. They are now suffering without food. Even the dogs in the harbor now have no fish available.

I want to educate my children well…My children should not go for fishing work because in fishing there is no stable income. They should study well so they can get any other good job (Vinitha, 25, fisher wife).

My children should do jobs other than fishing, because I do not want to see them suffering (Dina, 38, fish vendor).

I want good health for my children and grandchildren. I want to save the property for my future generation so they should not starve. My father-in-law did not save any property for us, so I won’t do the same for my children and grandchildren.

Growing indebtedness

The gradual increase in the amounts asked for vessel advances has left auctioneers particularly vulnerable to the impact of the ring seine ban. This is because the amounts loaned can be beyond recouping from other available means, such as fish vending. Before the complete ban came into force in February 2021, Neesha had invested Rs. 2 million as advances for four ring seine boats.

Now they ask Rs. 1-2 million for ring seine boats as an advance for auctioning work. When I started auctioning, I did not pay this much money, perhaps a quarter of this amount. We earned it in a good season. With that money we purchased our food, clothes, built houses. I earned my investment. But in recent times we are facing problems, especially in the last three to five years. And the government is trying to ban the ring seine boats. But we have invested a lot of money. Many people have given us loans to invest in the ring seine boats. The boats are there. If someone purchases the boats, the owners can return our money. If the ban is implemented, no one will purchase the boats. So, how can we repay the money?

Like many others, Veni’s vessel advances had also dramatically increased.

My investment in boats has been rising. Starting from Rs. 800,000, the most recent investment was the highest, about Rs. 2.5 million. They use that money to setup the boat and catch fish. This boat that I have invested in didn’t start catching as the ban was enforced, and this is the sole reason behind my current loss.

Previously, auctioneers would manage large private loans by paying back significant amounts quickly to stop interest escalating. Friends or family who had given smaller loans would also be content making a profit from receiving yearly interest and treating the loan as an investment. As the future of ring seines have become uncertain and no income is currently being generated, lenders have started to recall the full sums loaned. This recall of debts has led women to cut expenses such as education, pledge or sell other assets, and attempt to take out more loans to payback those with higher interests. Veni, usually energetic, appeared despondent:

Because of ring seine, so many people have a car, bike, their own houses. I have built my own house. Our children are studying in English matriculation schools…. Boat owners, people who get a percentage from the sale of fish, people who go in the boat to catch fish, company owners who have 10-20 boats, daily wage employees, all are suffering. To catch fish in ring seine, you need 40 people not just one or two. So, we all benefited from using ring seine. More than 100,000 people are affected by the ring seine ban. After the ban it’s tough for people to pay school fees. People are selling their jewellery and mangalsutra (gold chain presented by the groom to the bride at the time of marriage). People are suffering a lot. If you ask me, if they lift the ban on ring seine, all our lives will become better.

For the past two months we had not got any fish from the ring-seine boats. They are unable to operate. So now we depend on the fibre boats and are back to auctioning this catch. We earlier did this for our own men.

Without the ring seine, we find it hard to live. If just normal fishing in kattamarams or fibre boats, only fishermen can get their livelihood. If its ring seine fishing, the entire community can get their livelihood; many people can find work.

Conclusion

The introduction and rapid spread of the ring seine technology across Tamil Nādu post-2004 has had some unintended consequences for women. While the shift to larger boats and harbor landings left some women without access or opportunity to continue post-harvest work, others have been able to capitalize on the plentiful cheap fish for vending and drying and invest in becoming auctioneers for rings seine vessels. As the catches from ring seines increased, the earnings of women auctioneers increased in ways that dramatically improved their quality of life and investments in education and assets to secure their children’s future wellbeing.

Taking advantage of technological change presented by the ring seine to become an auctioneer relies on access to harbors and markets, the ability to build finances (often through social networks or access to loans) and develop industry knowledge, options open only to some women. Through auctioneer stories we however see the importance of women who serve as gateways for other women, introducing them to markets and the business of vending, often consciously helping women who, like themselves, are the primary household providers. Counterintuitively, these women do not necessarily belong to wealthy households, instead many are the sole providers, willing to take huge risks to secure the future wellbeing of themselves and their children.

Importantly, how women auctioneers finance their investments reveals the active role women play as a nexus for facilitating the expansion of ring seine technology and sustaining existing vessels. They serve not only as flexible funders for vessel repairs and lost nets, but also through their own private borrowing, redistribute the profits from ring seine expansion among a broader community of small-scale investors, mainly women, as financial transactions in fishing communities in south India have historically been the domain of women (Ram, Citation1991). Understanding this hidden role can draw awareness to the wider rippling effects of technology/policy change, such as the sudden ring seine ban, across the wider community.

These narratives, explaining how female auctioneers were able to capitalize on ring seine technology and the subsequent impact of the ban, have significant implications for understanding the constraints that determine women’s ability to access the opportunities created through new fish capture technologies. In the literature on fishing communities, women are often seen as secondary providers, supplementing men’s incomes or creating “buffers” for fluctuating incomes (Gustavsson, Citation2020). But auctioneer stories reveal how women in fisheries can become the primary household provider, even supporting multiple generations. There is a need for increased recognition of how differing gender constraints and contexts can make the impact of policy decisions uneven. In this case, the ring seine ban has had a particularly devastating impact on women auctioneers who have invested large sums of money, yet are invisible when it comes to accessing compensation or industry funding intended for men involved in the catching sector. In this case, men too have not been compensated, yet are able to return to small-scale fishing or then migrate for work, options not available to women.

Despite growing attention to the importance of women’s post-harvest work, it nevertheless continues to be devalued as secondary and less important, perhaps because it is performed by women (Pedroza-Gutiérrez & Hapke, Citation2022). There is hence little focus on supporting women to develop and expand their businesses in the context of technological changes that seek to both modernize fisheries and enhance growth. Auctioneer stories reveal that entry into the market is consequently uneven, often dependent on personal networks, one’s status, and access to other women willing to teach the trade. As such, not everyone is able to take advantage of the benefits offered.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. R. Manimohan and Ms. Kohila Shenbagam for support with data collection and transcription. We are also grateful to The Norwegian Research Council and the Economic and Social Research Council, UK, for funding the research on which this paper is based. Finally, our sincere thanks are due to the women who shared their stories with us.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Rs. 1 = 0.012 USD; or Rs. 82.60 = 1 USD.

2 Veni’s story: becoming a bold lady’ (https://ruralindiaonline.org/en/articles/venis-story-becoming-a-bold-lady/)

References

- Aswathy, P., & Kalpana, K. (2018). Women’s work, survival strategies and capitalist modernization in South Indian small-scale fisheries: the case of Kerala. Gender, Technology and Development, 22(3), 205–221. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10<?sch-permit JATS-0034-007?>.1080/09718524.2019.1576096 https://doi.org/10.1080/09718524.2019.1576096

- Azmi, F., Lund, R., Rao, N., & Manimohan, R. (2021). Well-being and mobility of female-heads of households in a fishing village in South India. Gender, Place & Culture, 28(5), 627–648. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2020.1739003

- Bavinck, M. (2018). Enhancing the Wellbeing of Tamil Fishing Communities (and Government Bureaucrats too): The role of ur panchayats along the Coromandel Coast, India. In Johnson, D., Acott, T., Stacey, N., & Urquhart, J. (Eds) Social wellbeing and the values of small-scale fisheries. MARE Publication Series (vol 17). Springer.

- Bavinck, M. (2020). The troubled ascent of a Marine Ring Seine Fishery in Tamil Nadu. Economic and Political Weekly, 55(14), 36–43. https://www.epw.in/journal/2020/14/ special-articles/troubled-ascent-marine-ring-seine-fishery-tamil.html

- Bennett, E. (2005). Gender, fisheries and development. Marine Policy, 29(5), 451–459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2004.07.003

- Brugere, C., Msuya, F. E., Jiddawi, N., Nyonje, B., & Maly, R. (2020). Can innovation empower? Reflections on introducing tubular nets to women seaweed farmers in Zanzibar. Gender, Technology and Development, 24(1), 89–109. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10<?sch-permit JATS-0034-007?>.1080/09718524.2019.1695307 https://doi.org/10.1080/09718524.2019.1695307

- CMFRI-DoF. (2020). Marine Fisheries Census 2016 - Tamil Nadu Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute, Indian Council of Agricultural Research, Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare; Department of Fisheries, Ministry of Fisheries, Animal Husbandry and Dairying, Government of India. 308p

- Das, P. H. D., & Edwin, L. (2018). Temporal changes in the ring seine fishery of Kerala, India. Indian Journal of Fisheries, 65(1), 47–54. https://doi.org/10.21077/ijf.2018.65.1.69105-08

- Dunaway, W. A. (2013). Gendered commodity chains: Seeing women’s work and households in global production. Stanford University Press.

- Edwin, L., & Das, P. H. D. (2015). Technological changes in ring seine fisheries of Kerala, and management implications. ICAR-Central Institute of Fisheries Technology.

- Evans, O. L. (2017). Fisherwomen – the uncounted dimension in fisheries management: Shedding light on the invisible gender. BioScience, 67(2), biw165. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biw165

- Fischer, G., Wittich, S., Malima, G., Sikumba, G., Lukuyu, B., Ngunga, D., & Rugalabam, J. (2018). Gender and mechanization: Exploring the sustainability of mechanized forage chopping in Tanzania. Journal of Rural Studies, 64, 112–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2018.09.012

- Ganguly, S. (2022). ‘Not like me’: educational aspirations and mothering in an urban poor neighbourhood in India. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 43(5), 770–785. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2022.2060185

- Gopal, N., Edwin, L., & Meenakumari, B. (2014). Transformation in gender roles with changes in traditional fisheries in Kerala, India. Asian Fisheries Science Special Issue, 27S, 67–78.

- Gopal, N., Hapke, H. M., & Edwin, L. (2023). Technological transformation and changing social relations in the ring seine fishery of Kerala, India. Maritime Studies, 22(26). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40152-023-00313-5

- Gulati, L. (1984). Technological change and women’s work participation and demographic behaviour: A case study of three fishing villages. Economic and Political Weekly, 19(49), 2089–2094. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4373851

- Gustavsson, M. (2020). Women’s changing productive practices, gender relations and identities in fishing through a critical feminisation perspective. Journal of Rural Studies, 78, 36–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.06.006

- Hapke, H. M. (2001). Petty traders, gender, and economic transformation in an Indian fishery. Economic Geography, 77(3), 225–249. https://doi.org/10.2307/3594073

- Hapke, H. M., & Ayyankeril, D. (2018). Gendered livelihoods in the global fish-food economy: A comparative study of three fisherfolk communities in Kerala, India. Maritime Studies, 17(2), 133–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40152-018-0105-9

- Harriss-White, B. (2004). Labour, gender relations and the rural economy. In Harriss-White B., & S. Janakarajan (eds.) Rural India facing the 21st century (pp.159–174). London: Anthem Press.

- Kurien, J. (1978). Entry of big business into fishing, its impact on fish economy. Economic & Political Weekly, 13(36), 1557–1565.

- Lawless, S., Cohen, P., McDougall, C., Orirana, G., Siota, F., & Doyle, K. (2019). Gender norms and relations: implications for agency in coastal livelihoods. Maritime Studies, 18(3), 347–358. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40152-019-00147-0

- Lawrence, T., Bhagath Singh, A., Bavinck, M., et al. (2022). The afflictions of marine fishing in Cuddalore district. In: Menon, A. (Ed.), Coastal transformation and fisher wellbeing: Perspectives from Cuddalore District, Tamil Nadu, India. Madras Institute of Development Studies. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7503034

- Mudege, N. N., Mdege, N., Abidin, P. E., & Bhatasara, S. (2017). The role of gender norms in access to agricultural training in Chikwawa and Phalombe, Malawi. Gender, Place & Culture, 24(12), 1689–1710. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2017.1383363

- Pedroza-Gutiérrez, C., & Hapke, H. M. (2022). Women’s work in small-scale fisheries: A framework for accounting its value. Gender, Place and Culture, 29(12), 1733–1750. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2021.1997936

- Pravin, P., & Meenakumari, B. (2016). Purse seining in India: A review. Indian Journal of Fisheries, 63(3), 162–174. https://doi.org/10.21077/ijf.2016.63.3.50404-18

- Ram, K. (1991). Mukkuvar women: Gender, hegemony & capitalist transformation in a South Indian fishing community. Zed Press.

- Rao, N., & Manimohan, R. (2020). (Re-)Negotiating gender and class new forms of cooperation among small-scale fishers in Tamil Nadu. UNRISD Occasional Paper 11. Overcoming Inequalities in a Fractured World: Between Elite Power and Social Mobilization. UNRISD.

- Rao, N., Singh, C., Solomon, D., Camfield, L., Sidiki, R., Angula, M., Poonacha, P., Sidibé, A., & Lawson, E. T. (2020). Managing risk, changing aspirations and household dynamics: Implications for wellbeing and adaptation in semi-arid Africa and India. World Development, 125, 104667. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104667

- Ray, S., & Mukherjee, S. (2022). Technology, gender and fishing in an Odisha Village. Indian Journal of Gender Studies, 29(2), 248–257. https://doi.org/10.1177/09715215221082177

- Rohe, J., Schlüter, A., & Ferse, S. C. (2018). A gender lens on women’s harvesting activities and interactions with local marine governance in a South Pacific fishing community. Maritime Studies, 17(2), 155–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40152-018-0106-8

- Rola‐Rubzen, M. F., Paris, T., Hawkins, J., & Sapkota, B. (2020). Improving gender participation in agricultural technology adoption in Asia: From rhetoric to practical action. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, 42(1), 113–125. https://doi.org/10.1002/aepp.13011

- Rubinoff, J. (1999). Fishing for status: Impact of development. On Goa’s Fisherwomen. Women’s Studies International, 22(6), 631–644. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-5395(99)00073-4

- Sivadas, M., Zacharia, P. U., Sarada, P. T., et al. (2019). Management Plans for the Marine Fisheries of Tamil Nadu. ICAR-CMFRI Mar. Fish. Policy Series No. 11. ICAR-Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute Kochi, Kerala, India.

- Swathi Lekshmi, P. S., Radhakrishnan, K., Narayanakumar, R., Vipinkumar, V. P., Parappurathu, S., Salim, S. S., Johnson, B., & Pattnaik, P. (2022). Gender and small-scale fisheries: Contribution to livelihood and local economies. Marine Policy, 136, 104913. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2021

- Tamil Nadu Marine Fishing Regulation Rules. (1983). (Updated 2020). http://www.stationeryprinting.tn.gov.in/extraordinary/2020/65_Ex_III_1a.pdf

- Vivekanandan, E., Rajagopalan, M., & Pillai, N. G. K. (2009). Recent trends in sea surface temperature and its impact on oil sardine. In Global Climate Change and Indian Agriculture (pp. 89–92). Indian Council of Agricultural Research

- World Bank, FAO, and IFAD. (2009). Gender in agriculture sourcebook. The World Bank, Food and Agriculture Organization, and International Fund for Agricultural Development.