ABSTRACT

Relocating people in informal settlements and upgrading the lives of those people require consistent commitment, good strategies, and supporting systems. In South Africa, in order to allocate subsidized housing to beneficiaries of an informal settlement, beneficiary administration needs to determine the number of people who qualify for subsidized houses. Without geo-spatial data-based technical verification, conventional methods of occupancy audits are often cumbersome, are unreliable, and do not promote smart and evidence-based decision making. Accordingly, the aim of this study is to propose and develop an Oracle-based mobile GIS tool to conduct an occupancy audit for Ulana, an informal settlement in Ekurhuleni Municipality in South Africa. Android-based tablets were used to collect the geographic and socio-economic attributes of the informal dwelling units (DU). Spatial analysis (in ArcGIS software and geo-spatial modeling environment) and statistical analysis were conducted to produce the occupancy audit. The results indicated that the use of mobile GIS provides up-to-date, accurate, comprehensive, and real-time data so as to facilitate the development of smart and integrated human settlements. The results of this audit also indicated that only 57% of the households residing in Ulana could potentially benefit from receiving a subsidized house. Accordingly, the occupancy audit enables planners to plan appropriate upgrading and housing development strategies for informal settlement. This study demonstrates that successful planning of housing delivery for post independent integrated neighborhoods is not a mere political rhetoric but is viable when it is based on reasonable geo-spatial techniques and information. The use of mobile GIS therefore needs to be extended to other informal settlement upgrading projects in South Africa as well as other cities in the global south. However, proper professional training is required to ensure the successful usage of smart mobile GIS tools.

1. Introduction

Urbanization is an increasing phenomenon in recent decades in developing countries (Turok and Borel-Saladin Citation2014) and has brought numerous challenges in the management of cities such as urban sprawl, pollution, disaster management, poor sanitation, and the growth of informal settlements (Freire, Lall, and Leipziger Citation2015). Africa is urbanizing rapidly (Freire, Lall, and Leipziger Citation2015), and 60% of its people are expected to be living in cities by 2050 (UN-Habitat Citation2010). This will change the structure of cities and mandate policy toward sustainable and inclusive growth (UN-Habitat Citation2015). The New Urban Agenda (UN-Habitat Citation2016) has therefore called for policy makers to shift their mind-sets from not viewing urbanization as a problem but rather as a tool for development. The strategic and integrated approach taken in the new strategic plan for 2014−2019 recommends a more systemic way that goes beyond addressing the symptoms of urbanization to linking urbanization and human settlements to sustainable development by focusing on the prosperity, livelihoods, and employment of the greater population (UN-Habitat Citation2016). This will be done by paying attention to the basic needs of the millions of people living in poverty within towns and cities, as well as urban slums (UN-Habitat Citation2016). Likewise, an emerging trend in countering urban challenges, particularly in the developed world, is the promotion of smart cities that seek smart solutions through the use of geo-spatial information and communications technology.

In developed countries, urbanization patterns were normally led by industrialization and economic development defined by the increase of productivity (Freire, Lall, and Leipziger Citation2015). However, Africa’s urbanization patterns often point toward a migration pattern of low-income people running into cities to seek better economic opportunities (Freire, Lall, and Leipziger Citation2015). With very little investment on infrastructure, this poses a challenge for cities that are unable to accommodate large population influxes and ensure favorable living environments (Freire, Lall, and Leipziger Citation2015). South Africa has a particular history that informed its migration and urbanization patterns over the past few decades. The apartheid system historically endeavored to restrict and control the population movement as well as settlement patterns in the urban and rural areas (Turok and Borel-Saladin Citation2014). Thus, tyrannical laws were enforced on people, such as the well-documented population control, Group Areas Act of 1950 (Act No. 41), and law was passed that caused impermanence in the urbanization process (Turok and Borel-Saladin Citation2014; Harrison, Todes, and Watson Citation2008; Zuma Citation2013). These events resulted in inadequate urban planning in the urban areas, which lead urban settlements into sprawling peri-urban areas (Harrison, Todes, and Watson Citation2008). This also meant that people were forced to live in ethnically homogenous homelands with limited access to land. As a result, there was a transition from an agrarian to a cash-based rural economy in order to provide large numbers of labor migrants (Zuma Citation2013). This unique urbanization has affected the housing sector in post independent South Africa, which saw the influx of people coming into major cities, most of whom find themselves living in informal settlements (Huchzermeyer Citation2004; Zuma Citation2013).

Until recently in 2004, the policy had not been developed for the new post-apartheid government for informal settlement upgrading. The Breaking New Ground (BNG) policy seen as a comprehensive plan for the development of informal settlements was developed only in 2004, after the realization that the housing subsidy scheme alone was not sufficient to deal with the large inflow of people in informal settlements especially in urban areas (Huchzermeyer Citation2004). A major challenge with the BNG in addressing urbanization and the growth of informal settlements are lack of data and the often-cumbersome methods used in enumerating informal settlements. This therefore hampers proper planning for informal settlement upgrading exercises, relocation or allocation of subsidized houses, and ultimately leads to wasteful expenditure, poorly planned settlements, and maintenance of the status quo. Geo-spatial techniques (earth observation and GIS) have shown great potential in providing data on informal settlements. Likewise, mobile GIS and geo-location-based services (Tao Citation2013) can provide useful data on informal settlements upgrading, relocation, and/or allocating subsidized houses.

With 70% of the world’s population living in cities, cities are rapidly growing. Traditional and conventional methods of planning and managing challenges, such as informal settlements, in cities do not work anymore in this new environment. Consequently, new approaches are necessary (Gruen Citation2013). Tao (Citation2013) notes that there is a strong expression by academic researchers and urban planners for the smart management and intelligent planning of cities to address urbanization challenges. The manifestation of informal settlements in cities has become overwhelming for urban planners. The collection, analysis, and management of geo-spatial data provide supports to urban planners and the state, and so better service delivery and pathways to poverty alleviation is possible (Kohli et al. Citation2012; Pinfold Citation2015; Kakembo and van Niekerk Citation2014). Information on both the physical and socio-economic characteristics is necessary to guide and support appropriate informal settlement upgrading approaches (Baud et al. Citation2010; Karanja Citation2010; Kohli et al. Citation2012). Traditional enumeration techniques often are cumbersome to conduct and lack the requisite information to guide decision on informal settlement upgrading. With the rapid progress in geo-information science, there is a great potential in the collection of hitherto difficult data on informal settlements.

With the emergence of smart cities (Ching and Ferreira Citation2015), popularization of ubiquitous sensor networks (Li et al. Citation2013; Puccinelli and Haenggi Citation2005) and the rapid progress in geo-information science, innovative and holistic techniques for collecting data on the physical and socio-economic attributes of informal settlements have been developed (Dubovyk, Sliuzas, and Flacke Citation2011). To ensure that data is detailed and useful for decision making on informal settlements upgrading, these techniques go beyond using information communication technology (ICT) to collect information to ensure collaboration, participation, learning and re-learning, adapting and investing in the future (Ching and Ferreira Citation2015). Emerging trends include use of mobile GIS, geo-location-based services, volunteered geographic information from social media and earth observation (Boulos et al. Citation2011; Li et al. Citation2013; Miller Citation2012). These techniques enable planners to obtain up-to date, real-time, extensive, and rich data that can be used to guide decision making on informal settlement upgrading, relocation, and allocation of housing subsides. Consequently, geo-spatial information has transformed the extent in which information can be used for planning purposes across the world (Chitekwe-Biti, Mudimo, and Nyama Citation2012; McCall Citation2003). As a result, Pinfold (Citation2015) applied participatory mapping and surveys in enumerating informal settlements in Cape Town to facilitate the re-blocking of settlements. However, this study focused on the physical structure and layout with little socio-economic and demographic data collected. Similarly, Kakembo and van Niekerk (Citation2014) used remote sensing images and mobile GIS to show population and structural growth of informal settlements in Nelson Mandela bay South Africa. Other studies have focused on the use of remote sensing to determine the growth of slums and the physical structure of informal settlements (Baud et al. Citation2010; Jain, Knieling, and Taubenböck Citation2015; Kemper et al. Citation2011). These studies hardly focus on the socio-economic profiling of the residents in slums. Consequently, the aim of this study is to use smart mobile GIS, to enumerate and conduct an occupancy audit in an informal settlement in South Africa, and demonstrate that the gleaned information can be used to plan for sound as well as appropriate informal settlement upgrading and housing development strategies. The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: the first is the study area Ekurhuleni; followed by the methodology, which describes how the occupancy audit was conducted; lastly the results and discussion are presented.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study area: Ulana informal settlement, Ekurhuleni, South Africa

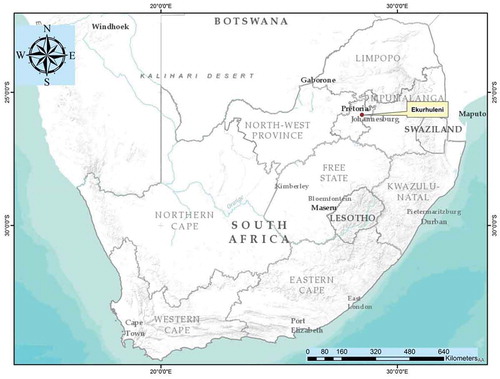

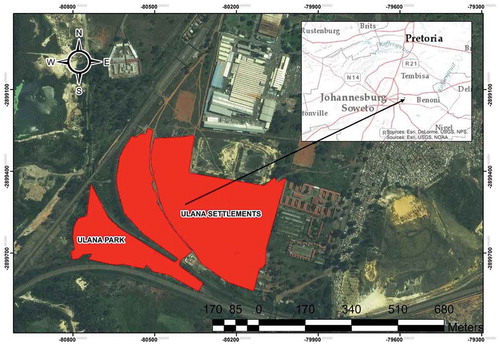

The Ekurhuleni region is a metropolitan area made up of an amalgamation of nine towns accompanied by its townships (townships in South Africa normally referring to the location where the black people reside in) (). The region was historically known as East Rand, with each town consisting of suburbs, industrial areas, and the black residential areas attached to them (Bonner and Nieftagodien Citation2012; City of Ekurhuleni Citation2005, Citation2013). It has a total surface area of 1,975 km2 with a population of 3,178,870 (City of Ekurhuleni Citation2013). It has a strong manufacturing sector and is regarded as the transportation hub of South Africa (having the busiest airport in Africa (City of Ekurhuleni Citation2013) and as such branding itself an “Aerotropolis” City (City of Ekurhuleni Citation2015)). It also has South Africa’s largest railway hub in Germiston, linking it to all major population centers and ports in the Southern Africa region. Ulana settlement is an informal settlement located in Boksburg, Ekurhuleni, and it is close to major highways as well manufacturing industries ().

2.2 Data description, collection, and preparation

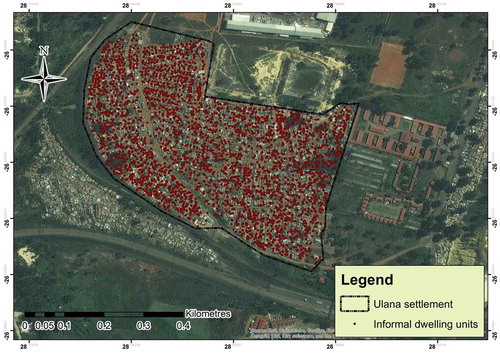

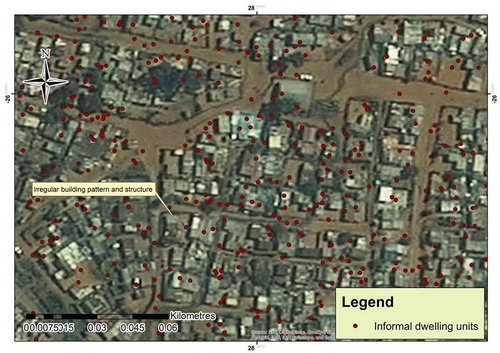

An Oracle and web-based mobile GIS tool was used to conduct the informal settlement occupancy audit in Ulana. Data collection was conducted from March 13 ~ 30 2015. A follow-up data collection session was completed during April 18−19 for occupants who were unavailable on March 2015. An android-based tablet with an offline Java application and GPS was used to collect points denoting the informal dwelling units () as well as the geographic coordinates (longitude and latitude), images of the informal DU, and the household attributes. The collected attributes included household income, whether someone had received a subsidized house, disability, and other information used for socio-economic information profiling. The occupancy audit attributes and sample dataset can be accessed in the works of Musakwa and Mokoena (Citation2017). This information was then transferred online using Wi-Fi and stored in a central server where gatekeepers (authorized officials and technocrats, such as managers and project leaders, within the Ekurhuleni Municipality and National Department of Human Settlements) could view it. The project managers would then check for inconsistencies and verify the accuracy of the data.

During the process of data collection, each household and DU was allocated a barcode to ensure that repetition and redundancy was eliminated. The identity number of the participants was used as a key identifier to avoid double capturing. Standard and validation rules were applied as the quality assurance. These validation rules included setting the locking mechanism where certain questions could not be responded to before prerequisite questions were answered. Lastly, to ensure data accuracy, the data collecting mobile application would only run in the precreated ring-fenced extent of Ulana settlement.

Minor challenges were experienced during data collection, such as documents of some members of the households without identification. In addition, it was difficult to obtain proof of income documents.

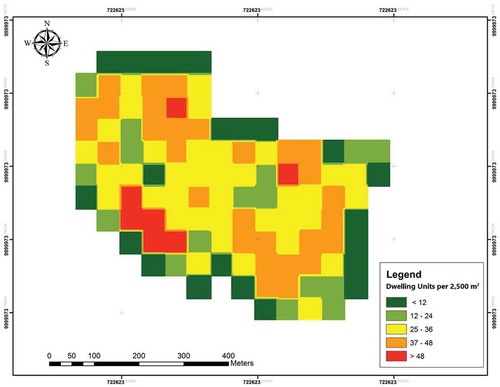

2.3. Data analysis

ArcGIS 10.3 was used to integrate the location and the attribution data for spatial analysis. Density analysis was performed by using the geo-spatial modeling environment (software) to determine the number of DU per 2,500 m2 (Beyer Citation2016). For the occupancy audit analysis, descriptive statistical analysis was carried out on demographic attributes, such as citizenship, gender, income, and dependants using Microsoft Excel 2013. Key statistics were income, employment status, household sizes, number of dependents, citizenships, and disability. These attributes are crucial because they determine whether one qualifies for a household subsidy or not. For example, non-citizens and those with a household income of more than 3,500 South African Rand (ZAR) per month would not qualify for a household subsidy.

To determine potential qualifiers for a housing subsidy, the identity document number of respondents was filtered and linked through the Housing Subsidy System (HSS), which is a database and information system that is linked to the National Housing Database. The HSS provides information to authorized persons on individual beneficiaries who have applied for housing. The National Department of Human Settlements is the overseer of the HSS, and the Provincial Department of Human Settlements is responsible for managing the database. Recently, some local municipalities were also given responsibilities for administrating and managing beneficiary applications. As a result, housing officials, researchers, and authorized users are able to log on to the system and check the names of applicants on the HSS database with those of the national database to see if applicants qualify for homes based on the qualification criteria of the housing programs (National Housing Code: Vol 3 Individual subsidies).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Settlement densities

shows the densities of built-up area in Ulana settlement, demonstrating the number of DU (shacks) per 2,500 m2. At least 70% of Ulana have high densities of above 25 DU per 2,500 m2. shows that some sections in Ulana have very high densities (>48 DU per 2500 m2). These densities are well above the permissible densities of 60 DU per hectare for single and semi-detached housing typologies (City of Ekurhuleni Citation2013; Citation2015). Therefore, it shows that households in Ulana are living under deplorable, squalid, and crowded conditions.

These very high densities in Ulana further negatively affect the quality of life as well quality of living place for its inhabitants. The living conditions of informal settlers are well described by Fanon (Citation1961) who wrote that “It is a world without spaciousness, men live there on top of each other, built one on top of the other……a hungry town, starved of bread, of meat, of shoes, of coal, of light……a crouching village, a town on its knees, a town wallowing in mire.” Similarly, the DUs in Ulana are built close to each other, and the poor building material significantly exposes them to fire hazards (). The community also has no access to electricity, and hence they use candles, paraffin, or gas in the crowded spaces. In case of a fire hazard, it certainly spreads quickly. Likewise, the health conditions continue to deteriorate in informal settlements due to the squalid and deplorable conditions. The lack of infrastructure services (drainage, sewerage, and tarred roads) makes it difficult for people to move around during rainy seasons and makes it a breeding ground for diseases. Dewan, Yamaguchi, and Ziaur Rahman (Citation2012) have noted that unplanned urban growth can lead to invasive disease infections, such as the dengue infection. Furthermore, there have reports on infectious diseases, such as typhoid fever in Gauteng, South Africa, owing to the sordid conditions. Diarrhea outbreaks have also been recorded over the past years in informal settlements (SA News Citation2016; Govender, Barnes, and Piper Citation2011). Relatedly, the high densities also pose a health risk, as they are a fertile breeding ground of pests, such as cockroaches and rats in South African cities (ENCA Citation2014). The Ekurhuleni Municipality acknowledges that it has a rat problem as a result of informal settlements, such as those in Ulana (ENCA Citation2013). Besides demonstrating the dense conditions in Ulana settlement, the household attributes are crucial derivatives that could not been obtained without use of smart mobile GIS.

3.2. Occupancy rate

The conducted audit revealed that Ulana settlement has 3,092 households with a total population of 7,031. The total population includes the head of household, spouses, and dependents. The crucial task for municipalities is determining how many people qualify for subsidized housing. illustrates that 1,758 households potentially qualify for subsidized housing, which means that about 57% would potentially be allocated houses. Furthermore, 13% of the households in Ulana qualify for partially subsidized and non-subsidized housing, and the rest 30% would qualify for rental market housing in the social housing program. With the use of mobile GIS for enumeration purposes, each DU can be assessed to determine who the occupants are and what their socio-economic status is. This geo-spatial information is vital for this study, because the municipality and decision makers can plan differently for their settlements, as different housing opportunities can be given according to their various housing needs.

Table 1. Occupancy audit in Ulana.

Similarly, verifying qualified beneficiaries with Housing Subsidy System and its National Housing Database enables the formulation of appropriate interventions. For example, without this system, taxpayers’ money would be lost in providing houses for people who do not qualify or worse (some households may receive multiple housing subsidies). Furthermore, this study demonstrates the utility of an innovative, smart approach in collecting robust and detailed data of informal settlements and in making evidence-based decision for prosperity promoting and sustainable development in the future.

3.3. Employment status and disability

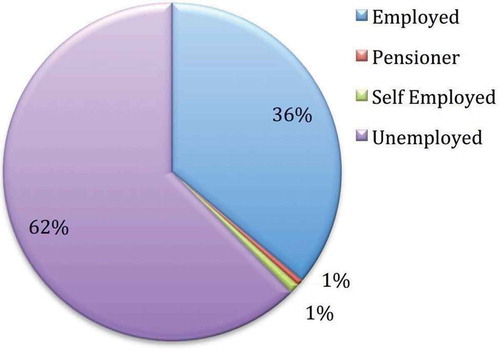

indicates that about 62% of the households in Ulana settlement are currently unemployed, about 36% are employed, whereas the self-employed and pensioners are 1% each. This demonstrates that unemployment is a key problem within the settlement and must be addressed by creating an enabling environment for economic opportunities. Similarly, the audit revealed that 702 of the employed households within the settlement earn with ZAR 2000−4999 per month, while 376 households earn between ZAR 5000 and 9999 and only 11 households earn above ZAR 10,000. This indicates that informal residents are mostly poor (less than ZAR 54,344 per year), which raises serious affordability issues in obtaining a house. Consequently, they are continuously trapped in a cycle of poverty and often feel excluded from the meaningfully economy participating. What is also evident is that different income groups are residing in the settlement, and therefore solutions in housing provision should cater for different housing typologies. Although poverty is a major reason of being unable to own a home, it is not only the cause in Ulana and South Africa in general. Ross (Citation2010) argues that the severe shortage of housing opportunities, which can be attributed to the legacy of apartheid planning, is a major reason. For example, Ulana settlement is very strategically located to major facilities, but there is a dearth of affordable housing for the poor. This points to a somewhat failed municipality and even state that cannot provide housing to the poor.

From the audit, 27 households in the settlement have disabilities, with 13 individuals having sight disability, six having physical disabilities and three with multiple disabilities (). Disability in Africa and developing countries could possibly mean being unable to access services. Groce et al. (Citation2011) note that the lack of access to education, healthy food, medical facilities, clean water, and sanitation for the disabled hampers their ability to earn a living, therefore prioritizing people with disabilities in housing projects must continue. Data collection tools for census often miss the disabled. Therefore, smart mobile GIS is a step in the right direction in collection of comprehensive datasets that can be used to promote sustainable urban development.

Table 2. Disability in Ulana.

4. Conclusions

Current data of informal settlements of the Ekurhuleni Local Municipality as well as other cities is outdated and mostly contains the approximate numbers of households in each settlement without detailed socio-economic and demographic attributes. Accordingly, the aim of the study was to use smart mobile GIS, enumerate, and conduct an occupancy audit in Ulana informal settlement, Ekurhuleni, South Africa. The results indicate that the use of smart mobile GIS provides information not only on the structure and form of informal DUs but also the socio-economic as well as demographic profile of the residents. This therefore enables planners to develop appropriate and evidence-based informal settlement upgrading strategies and housing developments. With the geo-spatial information gleaned from the occupancy audit of informal settlement, the municipality is able to determine how many people qualify for full or partially subsidized housing, rental housing, serviced stands, and/or fully bonded housing opportunities. This ensures that access to suitable housing options is provided for suitable people in post-colonial South Africa, and it may ultimately create integrated neighborhoods, in line with policy. The successful use of smart geo-spatial technology also demonstrates that successful planning for housing delivery is not rhetoric but is based on sound geo-spatial information. Mobile GIS as a means of conducting occupancy audits, therefore, needs to be extended to other informal settlements to promote evidence-based informal settlement upgrading projects in South Africa as well as other cities in the global south. However, in many cities, professional training will be required to ensure the successful usage of smart mobile GIS tools.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Human Settlement Department, City of Ekurhuleni, for providing the information needed to conduct this research.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Baleseng Tlholohelo Mokoena

Baleseng Tlholohelo Mokoena is currently a Senior Town Planning Technician at the Ekurhuleni Metropolitan Municipality’s Department of Human Settlements, Strategy and Macro Planning Division, GIS section. Her main responsibilities are to identify well-located land for Human Settlement Development. She also assists in developing and maintaining of the project information database, developing maps for the department, and conducting housing policy research to ensure strategic alignment. She completed her BTech in Town and Regional Planning from the University of Johannesburg in 2014. She is currently receiving Master courses in Town and Regional Planning, University of Pretoria, as well as Master Courses in the Built Environment (Housing) through the certificated individual short courses program at the University of the Witwatersrand. Her research interests focus on the application of GIS in informal settlement upgrading in urban spaces, post 1994. She currently has a book chapter on developing a well-located land index to establish smart human settlement for Ekurhuleni.

Walter Musakwa

Walter Musakwa holds a PhD in Geography and Environmental Studies from Stellenbosch University, South Africa, a Master in Urban and Regional Planning from University of Kwa Zulu-Natal, South Africa, and a BSc honors in Rural and Urban Planning from the University of Zimbabwe. His main research interests and publications are on societal applications of geo-spatial information technologies in urban planning, agriculture, and rural areas. He is also interested in smart cities, geolocation-based services, volunteered geographic information and their applications in developing countries. Walter is currently Associate Professor in the Department of Town and Regional Planning, University of Johannesburg, South Africa.

References

- Baud, I., M. Kuffer, K. Pfeffer, R. Sliuzas, and S. Karuppannan. 2010. “Understanding Heterogeneity in Metropolitan India: The Added Value of Remote Sensing Data for Analyzing Sub-Standard Residential Areas.” International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 12 (5): 359–374. doi:10.1016/j.jag.2010.04.008.

- Beyer, H. L. 2016. “Introducing the Geo-Spatial Modelling Environment.” http://www.spatialecology.com/gme/index.htm.

- Bonner, P., and N. Nieftagodien. 2012. Ekurhuleni: The Making of an Urban Region. Johannesburg: Wits University Press.

- Boulos, M. N. K., B. Resch, D. N. Crowley, J. G. Breslin, G. Sohn, R. Burtner, W. A. Pike, E. Jezierski, and K.-Y. S. Chuang. 2011. “Crowdsourcing, Citizen Sensing and Sensor Web Technologies for Public and Environmental Health Surveillance and Crisis Management: Trends, OGC Standards and Application Examples.” International Journal of Health Geographics 10 (1): 67–95. doi:10.1186/1476-072X-10-67.

- Ching, T. Y., and J. Ferreira Jr. 2015. Planning Support Systems and Smart Cities: Smart Cities: Concepts, Perceptions and Lessons for Planners. Switzerland: Springer.

- Chitekwe-Biti, B., P. Mudimo, and G. M. Nyama. 2012. “Developing an Informal Settlement Upgrading Protocol in Zimbabwe - the Epworth Story.” Environment & Urbanisation 24 (1): 131–148. doi:10.1177/0956247812437138.

- City of Ekurhuleni. 2005. “Ekurhuleni Growth Development Strategy 2055.” http://www.ekurhuleni.gov.za/thecouncil/strategy/gds-2025.

- City of Ekurhuleni. 2013. “Ekurhuleni Metropolitan Municipality: IDP, Budget & SDBIP. 2013/14-2015/16.” http://www.ekurhuleni.gov.za/.

- City of Ekurhuleni. 2015. “Regional Spatial Development Framework.” http://www.ekurhuleni.gov.za/rsdf-1.

- Dewan, A. M., Y. Yamaguchi, and M. Ziaur Rahman. 2012. “Dynamics of Land Use/Cover Changes and the Analysis of Landscape Fragmentation in Dhaka Metropolitan.” GeoJournal 77 (3): 315–330. doi:10.1007/s10708-010-9399-x.

- Dubovyk, O., R. Sliuzas, and J. Flacke. 2011. “Spatio-Temporal Modelling of Informal Settlement Development in Sancaktepe District, Istanbul, Turkey.” ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 66 (2): 235–246. doi:10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2010.10.002.

- ENCA. 2014. “Joburg to Spend, Millions to Fight Rat Epidemic.” http://www.enca.com/joburg-spend-millions-fight-rat-epidemic.

- ENCA (E-news Channel Africa). 2013. “Ekurhuleni Fights Rat Problem.” https://www.enca.com/south-africa/ekurhuleni-fights-rat-problem.

- Fanon, F. 1961. The Wretched of the Earth. London: Penguin Group.

- Freire, M., S. Lall, and D. Leipziger. 2015. The Oxford Handbook of Africa and Economics: Africa’s Urbanization: Challenges and Opportunities. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Govender, T., J. M. Barnes, and C. H. Piper. 2011. “Contribution of Water Pollution from Inadequate Sanitation and Housing Quality to Diarrheal Disease in Low-Cost Housing Settlements of Cape Town, South Africa.” American Journal of Public Health 101 (7): e4–9. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2010.300107.

- Groce, N., M. Kelt, R. Lang, and J. F. Trani. 2011. “Disability and Poverty: The Need for a More Nuanced Understanding of Implications for Development Policy and Practice.” Third World Quarterly 32 (8): 1493–1513. doi:10.1080/01436597.2011.604520.

- Gruen, A. 2013. “Smart Cities: The Need for Spatial Intelligence.” Geo-Spatial Information Science 16 (1): 3–6. doi:10.1080/10095020.2013.772802.

- Harrison, P., A. Todes, and V. Watson. 2008. Planning and Transformation: Learning from the Post-Apartheid Experience. London and New York: Routledge.

- Huchzermeyer, M. 2004. Unlawful Occupation, Informal Settlements and Urban Policy in South Africa and Brazil. Trenton: Africa World Press.

- Jain, M., J. Knieling, and H. Taubenböck. 2015. “Urban Transformation in the National Capital Territory of Delhi, India: The Emergence and Growth of Slums?” Habitat International 48: 87–96. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2015.03.020.

- Kakembo, V., and S. van Niekerk. 2014. “The Integration of GIS into Demographic Surveying of Informal Settlements: The Case of Nelson Mandela Bay Municipality, South Africa.” Habitat International 44: 451–460. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2014.09.004.

- Karanja, I. 2010. “An Enumeration and Mapping of Informal Settlements in Kisumu, Kenya, Implemented by Their Inhabitants.” Environment & Urbanisation 22 (1): 217–239. doi:10.1177/0956247809362642.

- Kemper, T., M. Jenerowicz, M. Pesaresi, and P. Soille. 2011. “Enumeration of Dwellings in Darfur Camps from GeoEye-1 Satellite Images Using Mathematical Morphology.” IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 4 (1): 8–15. doi:10.1109/JSTARS.2010.2053700.

- Kohli, D., R. Sliuzas, N. Kerle, and A. Stein. 2012. “An Ontology of Slums for Image Based Classification.” Computers, Environment and Urban Systems 36 (2): 154–163. doi:10.1016/j.compenvurbsys.2011.11.001.

- Li, D., J. Shan, Z. Shao, X. Zhou, and Y. Yao. 2013. “Geomatics for Smart Cities-Concept, Key Techniques, and Applications.” Geo-Spatial Information Science 16 (1): 13–24. doi:10.1080/10095020.2013.772803.

- McCall, M. K. 2003. “Seeking Good Governance in Participatory-GIS: A Review of Processes and Governance Dimensions in Applying GIS to Participatory Spatial Planning.” Habitat International 27: 549–573. doi:10.1016/S0197-3975(03)00005-5.

- Miller, G. 2012. “The Smartphone Psychology Manifesto.” Perspectives on Psychological Science 7 (3): 221–237. doi:10.1177/1745691612441215.

- Musakwa, W., and B. T. Mokoena. 2017. “Occupancy Audit of Ulana Informal Settlement in Ekurhuleni Municipality, South Africa.” https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/n9rmn93f5r/2.

- Pinfold, N. May 25–292015. Community Mapping in Informal Settlements for Better Housing and Service Delivery, Cape Town, South Africa. Lisbon, Portugal: INSPIRE Geo-spatial World Forum.

- Puccinelli, D., and M. Haenggi. 2005. “Wireless Sensor Networks: Applications and Challenges of Ubiquitous Sensing.” IEEE Circuits and Systems Magazine 5 (3): 19–31. doi:10.1109/MCAS.2005.1507522.

- Ross, F. C. 2010. Raw Life, New Hope: Decency, Housing and Everyday Life in a Post-Apartheid Community. Claremont: UCT Press.

- SA News. 2016. “Gauteng on Alert after Four Cases of Typhoid Fever.” http://www.sanews.gov.za/south-africa/gauteng-alert-after-four-cases-typhoid-fever.

- Tao, W. 2013. “Interdisciplinary Urban GIS for Smart Cities: Advancements and Opportunities.” Geo-Spatial Information Science 16 (1): 25–34. doi:10.1080/10095020.2013.774108.

- Turok, I., and J. Borel-Saladin. 2014. “Is Urbanisation in South Africa on a Sustainable Trajectory?” Development Southern Africa 31 (5): 675–691. doi:10.1080/0376835X.2014.937524.

- UN-Habitat. 2010. “State of the World’s Cities 2010/2011 - Cities for All: Bridging the Urban Divide.” http://mirror.unhabitat.org/pmss/getPage.asp?page=bookView&book=2917.

- UN-Habitat. 2015. “Urban Solutions. United Nations Human Settlements Programme, Nairobi 2015.” https://unhabitat.org/books/urban-solutions-united-nations-human-settlements-programme-nairobi-2015/.

- UN-Habitat. 2016. “Habitat III: New Urban Agenda.” https://unhabitat.org/draft-new-urban-agenda-approved/.

- Zuma, N. November 1−2 2013. Rural-Urban Migration in South Africa. Haikou, China: Economic Policy Forum.